Abstract

Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 2 repairs irreversible topoisomerase II-mediated cleavage complexes generated by anticancer topoisomerase-targeted drugs and processes replication intermediates for picornaviruses (VPg unlinkase) and hepatitis B virus. There is currently no TDP2 inhibitor in clinical development. Here, we report a series of deazaflavin derivatives that selectively inhibit the human TDP2 enzyme in a competitive manner both with recombinant and native TDP2. We show that mouse, fish, and C. elegans TDP2 enzymes are highly resistant to the drugs and that key protein residues are responsible for drug resistance. Among them, human residues L313 and T296 confer high resistance when mutated to their mouse counterparts. Moreover, deazaflavin derivatives show potent synergy in combination with the topoisomerase II inhibitor etoposide in human prostate cancer DU145 cells and TDP2-dependent synergy in TK6 human lymphoblast and avian DT40 cells. Deazaflavin derivatives represent the first suitable platform for the development of potent and selective TDP2 inhibitors.

Graphical Abstract

Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 2 (TDP2) is among the most recently identified DNA repair enzymes.1,2 It excises topoisomerase II (Top2α and/or β) from the 5′-end of Top2-induced DNA breaks, which are trapped and generate the cytotoxic lesions of anticancer Top2 inhibitors. Persistent Top2 cleavage complexes are also produced by endogenous DNA alterations (for a review, see ref 1) and have recently been described at the promoters of early response genes in conjunction with TDP2 recruitment.3 Although TDP2 has been named based on its activity to excise Top2 by cleaving between the DNA phosphate group and the covalently linked Top2 catalytic tyrosine residue, TDP2 has also been identified as the picornavirus VPg-unlinkase, which frees the 5′-viral RNA end from the covalently bound tyrosine of the VPg viral proteins during the replicative cycle of picornaviruses (polio-viruses, coxackieviruses, rhinoviruses, and the foot-and-mouth disease virus4). More recently, TDP2 has been linked with hepatitis B virus replication during the formation of covalently closed circular viral DNA, which acts as a viral persistence reservoir.5

Prior to the discovery of its DNA repair functions, TDP2 was known as TTRAP (TRAF and TNF receptor-associated protein) for its interaction with TNF receptor-associated factors including TRAF 2, 3, 5, and 66 and as EAPII (ETS1-associated protein 2) for its role as a negative transcription regulator of ETS1 and AP1.7 Recently, TDP2/TTRAP/EAPII protein levels have been reported to be elevated in lung cancer tissues where the oncogenic role of TDP2 was linked to upregulation of BRAF, MYC, and cyclin D1 leading to accelerated G1/S cell cycle transition.8,9 Whether these transcription functions of TDP2 are related to its role for the excision of irreversible Top2 cleavage complexes at promoters3 remains to be further investigated but is plausible based on the importance of TDP2 for transcription regulation.3,10–15

TDP2 is an attractive pharmacological target because it drives resistance to Top2 inhibitors, which are widely used as anticancer agents, and because of its implication in viral replication. TDP2 knockout cells are highly sensitive to anticancer Top2 poisons.2,16 Moreover, TDP2 serves as a backup repair pathway for anticancer Top1 inhibitors (camptothecin, irinotecan, and topotecan) in cells deficient for TDP1,17 which is the case for a subset of lung cancers.18,19 Under the synthetic lethality paradigm, combination therapies with Top2 and TDP2 inhibitors should increase the selective targeting of tumor cells bearing ATM mutations or homologous recombination (HR) deficiencies because such cancer cells are hypersensitive to Top2 inhibitors.14,20 Because ATM mutations and HR deficiencies occur frequently in cancers, the combined use of TDP2 and Top2 inhibitors could be applicable to a significant population of cancer patients. Off-target effects and potential toxicities should not be an issue because TDP2 knockout cells are viable with a normal doubling time while maintaining a selective sensitivity to Top2 inhibitors but not to a broad range of DNA damaging agents.14 TDP2 knockout mice are also viable without obvious phenotype unless they are treated with Top2 inhibitors14 or one looks microscopically at their brains at maturity.15 TDP2 inhibitors may also be valuable probes to further study the role of TDP2 in viral replication and potentially generate novel antiviral agents.

Deazaflavins were recently identified by biochemical screening for TDP2 inhibitors.21 However, detailed understanding of their mechanism of action and potential cellular inhibition of TDP2 had not been reported. In this study, we demonstrate the potential value of these inhibitors based on their potency at nanomolar concentration, their exquisite selectivity for human TDP2, and their interactions with specific TDP2 amino acid residues and provide evidence for selective targeting of cellular TDP2. Therefore, deazaflavins set the stage for the development of TDP2 inhibitors.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Compound 1 Is a Nanomolar Inhibitor of Human TDP2.

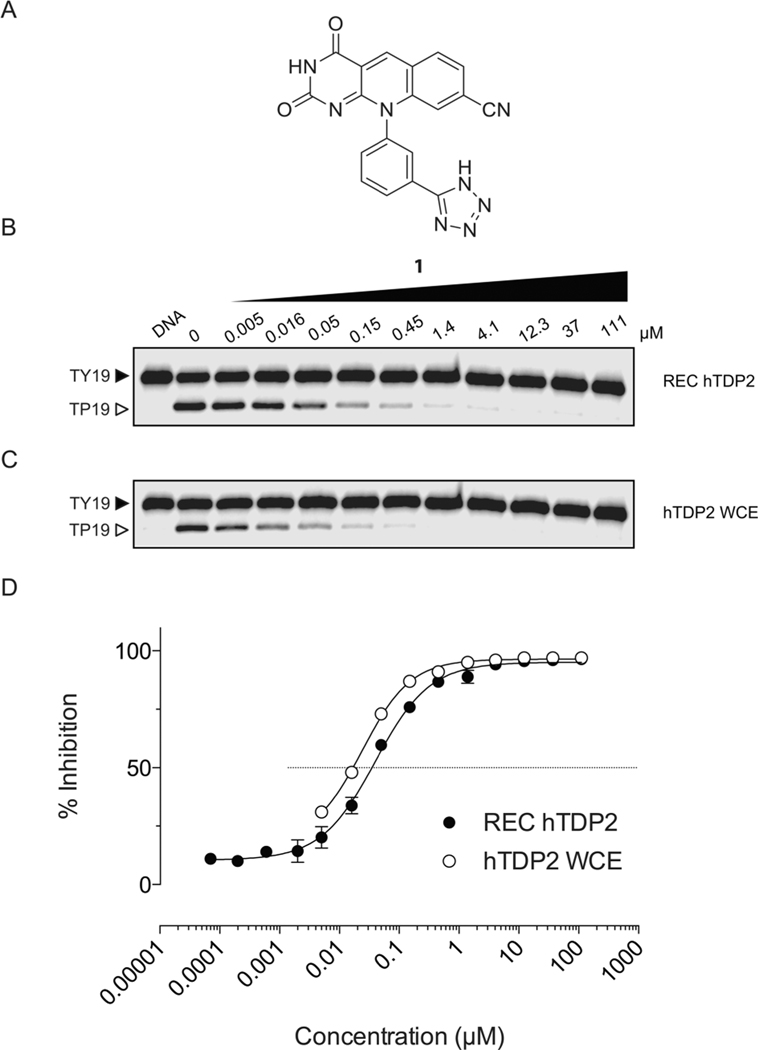

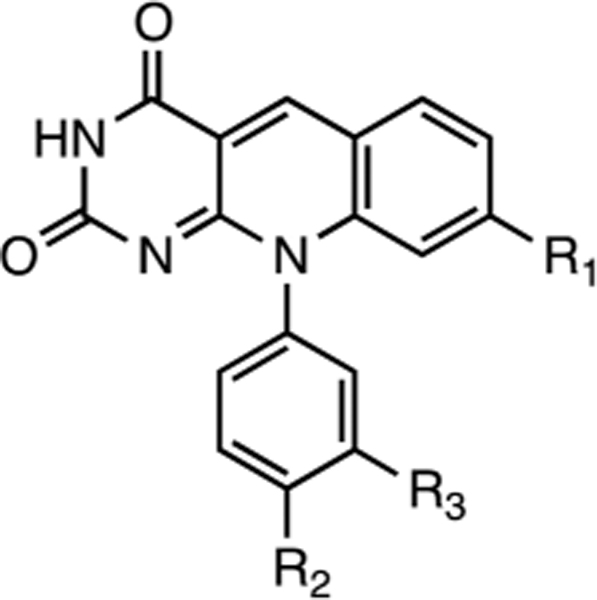

A series of deazaflavin derivatives (ref 21, Tables 1 and 3) was tested against TDP2 in biochemical assays by detecting the removal a 5′-tyrosyl residue at the end of a single-stranded oligonucleotide mimicking an aborted Top2 cleavage complex.23,24,26 Figure 1 shows representative results for one of the most potent derivatives (compound 1), which inhibits recombinant human TDP2 (REC hTDP2) with an IC50 of 40 ± 3 nM (Figure 1B,D; Table 1). This nanomolar potency was maintained when REC hTDP2 was replaced by whole cell extracts of TDP2 knockout DT40 cells complemented with hTDP2 ref 17, WCE TDP2 Figure 1C, Table 1). These results indicate that 1 effectively inhibits human TDP2, both as a recombinant enzyme and as an endogenous protein in whole cell extracts without being affected by other proteins present in the whole cell extract mixture. The activity of compound 1 against human cellular TDP2 was confirmed in whole cell extracts from human colon carcinoma HT29 cells (Supporting Information Figure 1). Compound 1 was also active against native endogenous avian TDP2 in DT40 whole cell extracts (Supporting Information Figure 1).

Table 1.

IC50 Values for the Inhibition of TDP2 Proteins by 1 and Derivativesa

|

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| R1=CN | =CN | =CN | =CI | =H | ||

| R2=H | =OH | =H | =OH | =H | ||

| R3=Tet | =H | =H | =H | =H | ||

| hTDP2 | REC | 0.040 ± 0.003 | 0.14 ±0.03 | 0.30 ± 0.06 | 3.9 ±0.7 | 71 ±6 |

| WCE | 0.033, 0.025 (n=2) | 0.062 (n=1) | 0.180 (n=1) | 2.3 (n=1) | 20 (n=1) | |

| mTDP2 | WT | >111 | >111 | >111 | >111 | >111 |

| 5M | 1.2 ±0.1 | - | - | - | - | |

| 8M | 0.71,0.58 (n=2) | 1.1 (n=1) | 3.7 (n=1) | 35 (n=1) | >111 | |

| 9M | 0.029 ±0.010 | 0.170 (n=1) | 0.260 (n=1) | 4 (n=1) | 71 (n=1) | |

IC50 values expressed as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments unless otherwise indicated. Tet = tetrazole group. (−) not determined.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of human TDP2 by 1. (A) Structure of compound 1. (B) Representative gel showing concentration-dependent inhibition of recombinant human TDP2 (REC hTDP2) by 1. (C) Representative gel showing concentration-dependent inhibition of endogenous human TDP2 activity in whole cell extracts (hTDP2 WCE) by 1. Concentrations of REC hTDP2 and hTDP2 WCE are 100 pM and 20 μg/mL, respectively. (D) Compiled concentration response inhibitory curves obtained for 1 against recombinant human TDP2 and whole cell extracts. For the REC hTDP2, error bars correspond to standard deviations (SD) from at least three independent experiments. For hTDP2 WCE, the inhibition curve is derived from the representative gel presented in panel C.

Compound 1 Is a Competitive Inhibitor of Human TDP2.

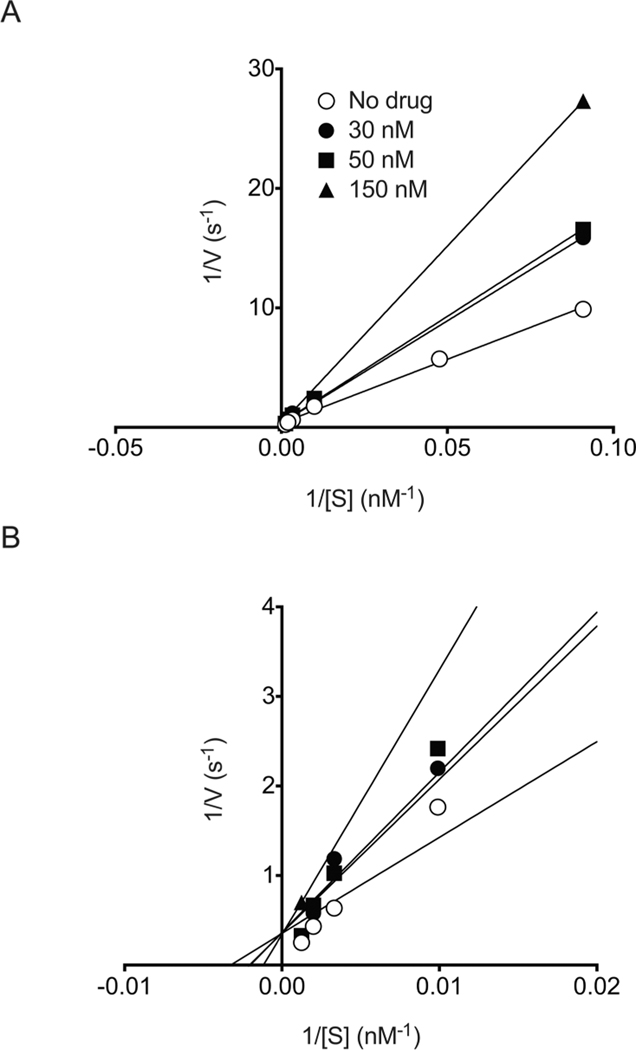

Kinetics experiments were performed with 1 at different concentrations of DNA substrate and various drug concentrations around the IC50. A Lineweaver double-reciprocal plot was derived from these experiments and is presented in Figure 2A. The curves all intersect at the y axis (Figure 2B) and are associated with an increase in KM when the drug concentration is increased (Table 2). These results demonstrate that 1 is a competitive inhibitor of hTDP2.

Figure 2.

Competitive inhibition of human TDP2 by 1. (A) Lineweaver–Burk double reciprocal plot obtained for recombinant human TDP2 in the presence of the indicated concentrations of 1. (B) Expanded view of the intersecting curves in the origin area of the Lineweaver–Burk double-reciprocal plot presented in A.

Table 2.

Kinetics Parameters for the Inhibition of Human TDP2 by 1

| concentration (nM) | kcat (s−1) | Km (nM) | kcat/KM (M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2.79 | 302 | 9.2 × 106 |

| 30 | 2.75 | 471 | 5.8 × 106 |

| 50 | 2.71 | 485 | 5.6 × 106 |

| 150 | 3.03 | 900 | 3.4 × 106 |

Zebrafish and C. elegans TDP2 Are Resistant to Deazaflavin Derivatives.

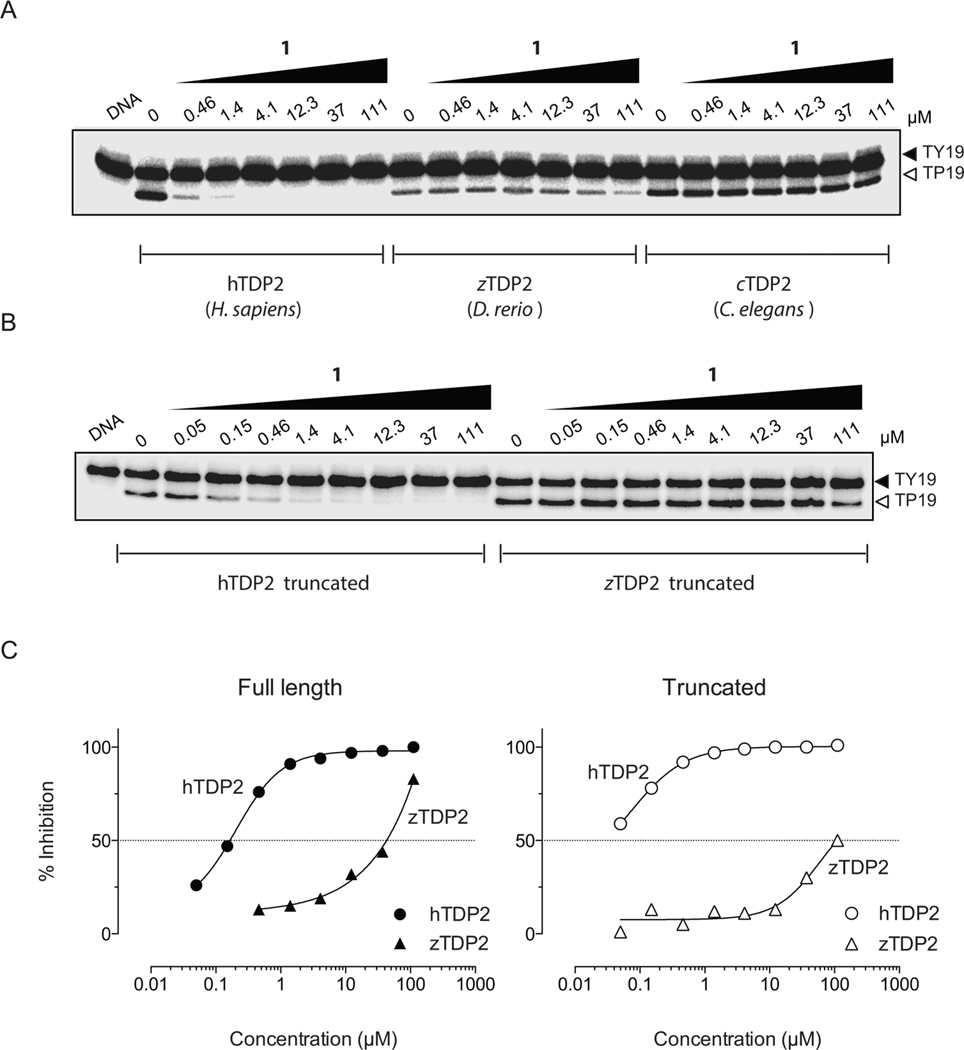

Compound 1 was evaluated for its ability to inhibit zebrafish TDP2 (zTDP2) and C. elegans TDP2 (cTDP2), which exhibit substantial sequence differences between each other and compared to human and chicken TDP2.22 Most interestingly and in contrast to the chicken TDP2 enzyme (Supporting Information Figure 1), both proteins were resistant to 1 (Figure 3 and Table 1) and other deazaflavin derivatives by at least 3 orders of magnitude (Table 1). Because TDP2 proteins differ the most in sequence from hTDP2 in their N-terminal domain, we tested the influence of their N-terminal domain on their resistance to 1. Because zTDP2 is closer to hTDP2 in phylogeny, we tested truncated hTDP2 (110–362, hTDP2 truncated) and zTDP2 (120–369, zTDP2 truncated). The truncated zTDP2 protein remained resistant by at least 3 orders of magnitude to 1 while hTDP2 truncated remained as sensitive as the full-length protein (Figure 3B,C), indicating that the N-terminal domain of zTDP2 does not determine its resistance to 1. These results demonstrate that differences in the catalytic core domain of the different TDP2 proteins must be responsible for the observed differential sensitivity to deazaflavin derivatives.

Figure 3.

Specificity of 1 for human TDP2 and resistance of zebrafish and C. elegans TDP2 to 1. (A) Representative gel showing concentration-dependent inhibition of recombinant H. sapiens TDP2 (human, hTDP2) by 1 and resistance of both D. rerio TDP2 (zebrafish, zTDP2) and C. elegans TDP2 (cTDP2) enzymes to the drug. (B) Representative gel showing concentration-dependent inhibition of both N-truncated human (110–362, hTDP2 truncated) and zebrafish (120–369, zTDP2 truncated) TDP2 proteins. (C) Concentration response inhibitory curves obtained for 1 against both full-length and truncated TDP2 proteins and derived from the representative gels presented in panels A and B.

Mouse TDP2 Is Resistant to Compound 1 unless Mutated at Specific Residues Corresponding to hTDP2.

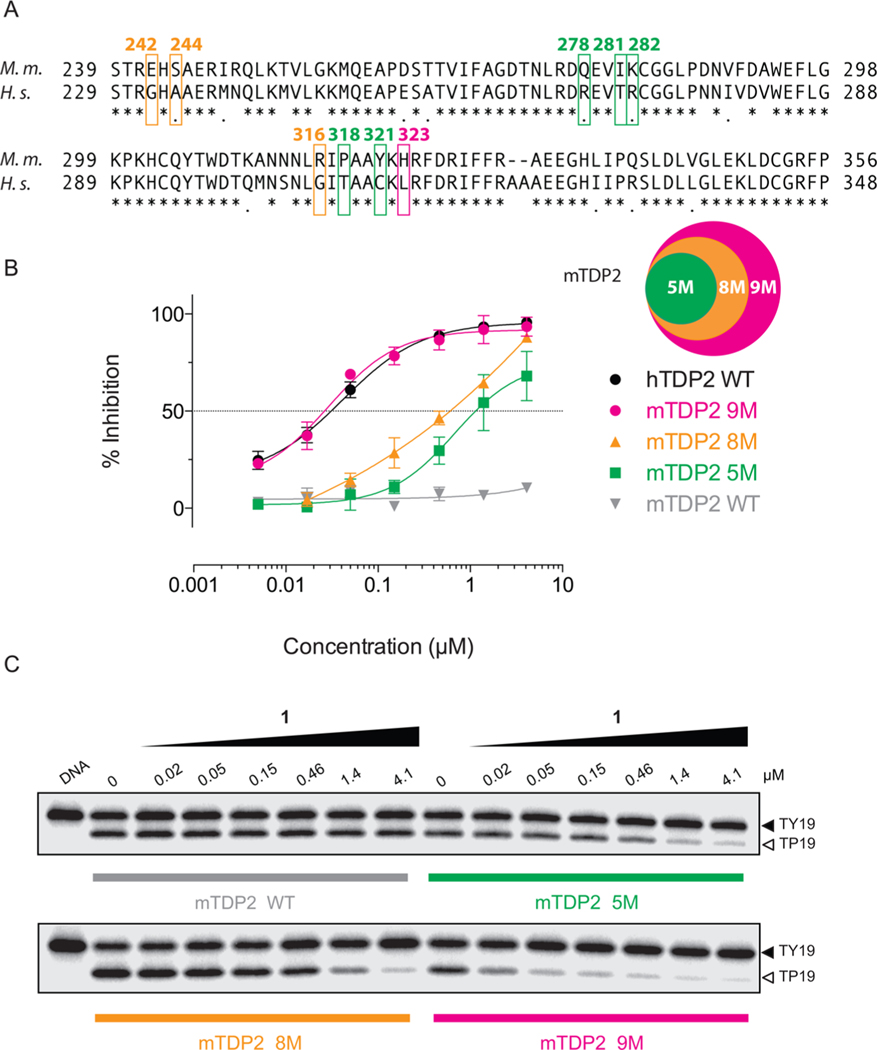

Because of the sequence similarity between mouse TDP2 (mTDP2) and the human hTDP2 (Figure 4A), we tested 1 against mTDP2. Surprisingly, the mTDP2 protein was highly resistant to 1 with an IC50 value of >111 μM (Figure 4B,C, Table 1). Next, we generated a series of mTDP2 proteins in which surface residues were mutated to their human corresponding counterparts (Figure 4A and Supporting Information Figure 2). The mTDP2 5M protein bears the five human mutations Q278R, I281T, K282R, P318T, and Y321C (Figure 4A). It remained resistant to 1 (Figure 4B,C) with an IC50 of 1.2 ± 0.1 μM (Table 1). The mTDP2 8M protein adds to 5M three additional mutations at residues E242G, S244A, and R316G. It was only marginally more sensitive than 5M (Figure 4B,C) with an IC50 of 0.6 μM (Figure 4C; Table 1). Most interestingly, the addition of a single additional mutation H323L to the 8M protein, which generates the mTDP2 protein 9M, fully sensitized the mouse TDP2 to 1 similarly to hTDP2 levels (Figure 4B,C) with an IC50 of 29 ± 1 nM (Figure 4B,C; Table 1). These results highlight the importance of the single H323 amino acid residue as a critical determinant of response to 1.

Figure 4.

Resistance of mouse TDP2 to 1 and determination of critical residue for 1 activity. (A) Amino acid sequence alignment between mouse (Mus muscullus) and human (Homo sapiens) TDP2 proteins. Residues mutated in mTDP2 5M (green), mTDP2 8M (orange + green), and mTDP2 9M (magenta + orange + green) are highlighted directly on the sequence and numbered according to the mouse sequence. The mTDP2 9M protein includes the eight mutations comprised in mTDP2 8M, which itself includes the five mutations found in mTDP2 5M. (B) Concentration response inhibitory curves obtained for 1 against recombinant mouse TDP2 wild type (WT), 5M, 8M, and 9M in comparison to hTDP2 WT. Error bars correspond to SD from at least three independent experiments. (C) Representative gels showing the resistance of recombinant mouse TDP2 to 1 and the progressive rescue of drug sensitivity by mutating amino acid residues to their human counterpart, which yielded the 5M, 8M, and 9M TDP2 proteins.

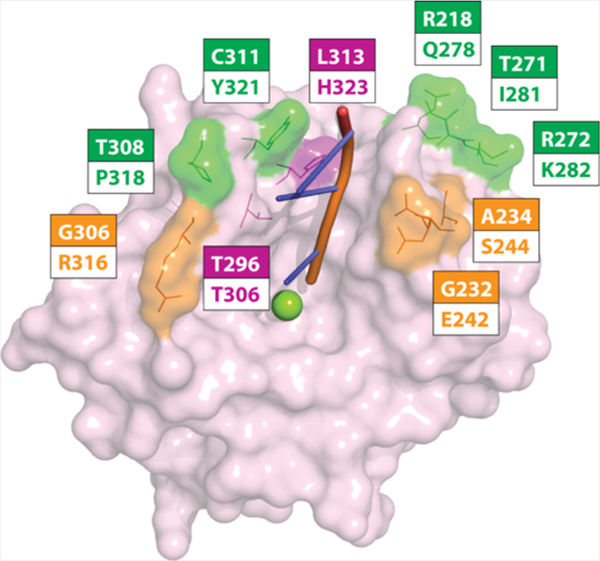

Single Point Mutations at the Human 313 and 296 Positions Are Sufficient to Induce Resistance against Compound 1.

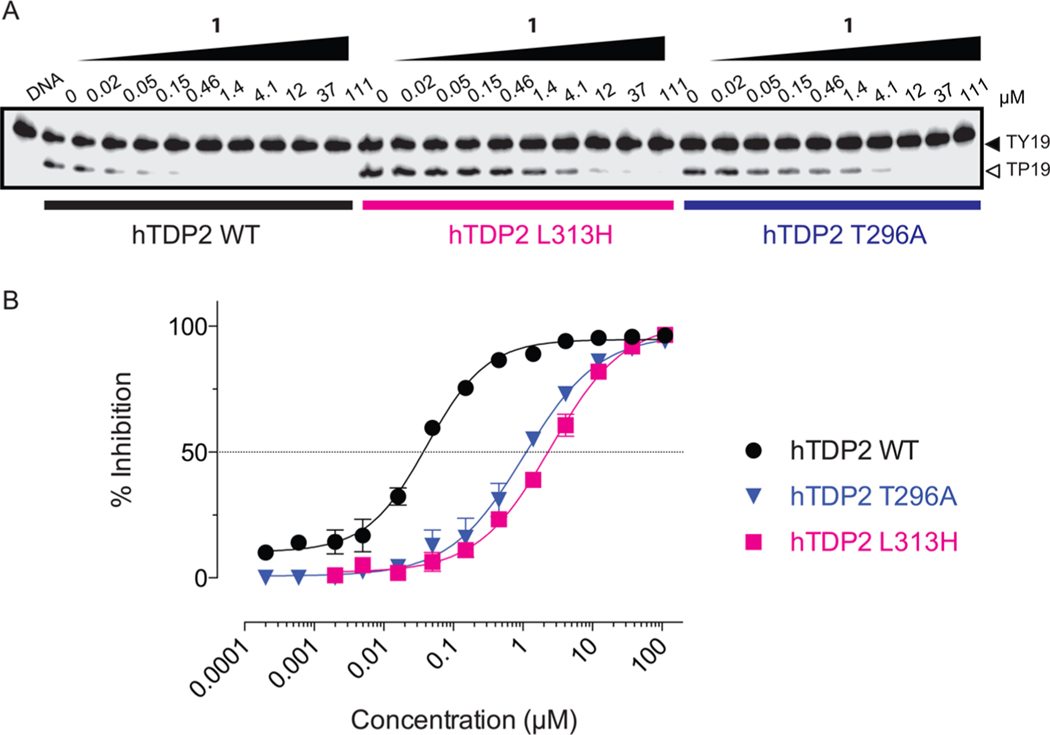

Due to the importance of the H323L mutation in mTDP2 (mouse-to-human residue, Figure 4A) in the context of other human mutations, we tested the impact of the corresponding L313H mutation (human-to-mouse residue, Figure 4A) in hTDP2 on the resistance to 1. The single mutant L313H hTDP2 was over 50-fold resistant to 1 when compared to hTDP2 wild type (hTDP2 WT, Figure 5A) with an IC50 of 2.5 ± 0.2 μM. We also tested the impact of mutations at other positions within 6 Å of the catalytic metal reported in the different crystal structures of TDP2.22,27 Among these, mutation of residue T296 (T306 in mouse, Supporting Information Figure 2) to alanine was found to confer resistance against 1 up to 25-fold with an IC50 value of 1.0 ± 0.1 μM. These results show that human TDP2 amino acid residues L313 and T296 are critical for the activity of compound 1.

Figure 5.

Resistance of the single point mutant L313H human TDP2 to 1. (A) Representative gel showing concentration-dependent inhibition of recombinant human TDP2 (hTDP2 WT) by 1 and differential responses of the point mutants L313H and T296A human TDP2 proteins to the drug. (B) Concentration response inhibitory curves obtained for 1 against recombinant human TDP2 wild type (hTDP2 WT) and single point mutants L313H and T296A human TDP2 proteins. Error bars correspond to SD from at least three independent experiments.

Analogs of Compound 1 Show the Importance of the Cyano Group for TDP2 Inhibition.

Examination of four analogs of 1 showed that two of them, 2 and 3, inhibited hTDP2 with IC50 values of 0.14 ± 0.03 and 0.30 ± 0.06 μM, respectively (Table 1). These results suggest that the tetrazole group present at the R3 position on 1 may be favorable but is not absolutely required for TDP2 inhibition (Table 1). When the cyano group of 2 is replaced by a chloro group in 4, potency against hTDP2 decreases by 27-fold (Table 1) and when this chloro group is removed in 5, the compound loses an additional 18-fold of potency (Table 2). These results highlight the importance of the cyano group of 1 at this particular position for hTDP2 inhibition. All analogs were inactive against mTDP2, but sensitivity to the drugs was recovered with mTDP2 9M, similarly to the results observed with compound 1 (Table 1).

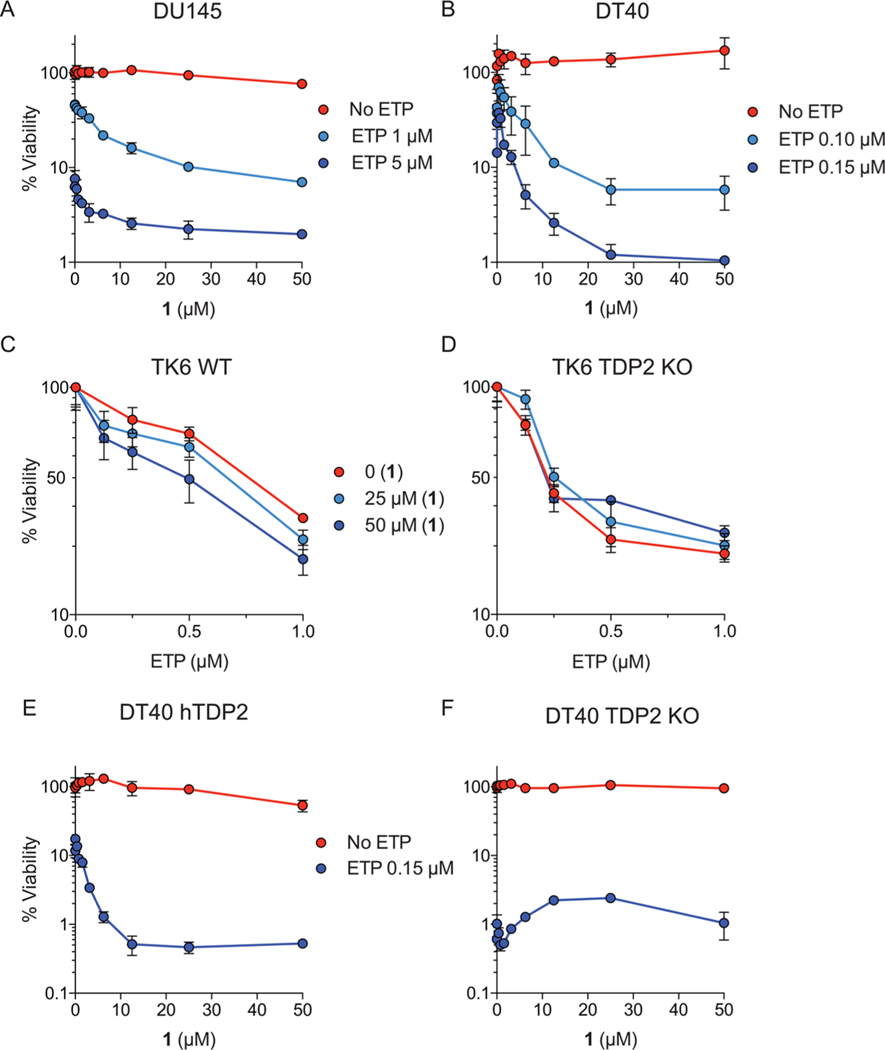

Compound 1 Is Synergistic with Etoposide in Cells.

Compound 1 was evaluated for its cytotoxicity in DU145 prostate cancer cells in the presence of pharmacologically relevant concentrations of etoposide (ETP, Figure 6A). Viability curves show that 1, which was not cytotoxic by itself up to 50 μM, killed over 90% of the cells when used in combination with 1 μM of ETP. This concentration of ETP by itself only killed around 50% of the cells (Figure 6A). A supra-additive effect was also observed at 5 μM ETP (Figure 6A). This result demonstrates a synergistic effect of 1 in the presence of ETP in human cells. The analog 3 (equivalent to 1 without the tetrazole group, Table 1) also showed a synergistic effect with ETP in DU145 cells (Supporting Information Figure 3). Compound 1 was also evaluated in DT40 avian lymphoblastoid cells and also showed synergy with ETP (Figure 6B), which is consistent with our finding that 1 inhibits both human and chicken TDP2 in biochemical assays (see above). When tested in TK6 human lymphoblastoid cells, a supra-additive effect was also observed for 1 with increasing concentrations of ETP (Figure 6C). This effect was TDP2-dependent, as synergy was not observed in TK6 TDP2 KO cells (Figure 6D). Compound 1 was also evaluated in TDP2 knockout DT40 cells with or without complementation for human TDP2 (DT40 hTDP2 and DT40 TDP2 KO, respectively). Compound 1 exhibited a synergistic effect in DT40 hTDP2 cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of ETP (Figure 6E), but synergy was greatly reduced in DT40 TDP2 KO cells (Figure 6F). Furthermore, the synergy observed in DT40 hTDP2 cells in the presence of ETP was not observed when ETP was replaced by the topoisomerase I poison camptothecin, indicating the selectivity of 1 for the repair of Top2 cleavage complexes (Supporting Information Figure 4). These results show the absence of cytotoxicity and the penetration of the deazaflavin derivatives in eukaryotic cells. Altogether, these results are consistent with inhibition of TDP2 by deazaflavin derivatives in cells.

Figure 6.

Cellular activity of 1 as measured by their synergistic effect with etoposide (ETP). (A,B) Cellular viability curves of DU145 human prostate cancer cells and DT40 chicken lymphoma cells obtained in the presence of indicated concentrations of 1 and ETP. (C) Cellular viability curves of TK6 human lymphoblastoid cancer cells (TK6 WT) obtained in the presence of indicated concentrations of 1 and ETP. (D) Cellular viability curves of TK6 TDP2 knockout cells (TK6 TDP2 KO) obtained in the presence of indicated concentrations of 1 and ETP. (E,F) Cellular viability curves of TDP2 knockout DT40 cells with or without complementation with human TDP2 (DT40 hTDP2 and DT40 TDP2 KO, respectively) in the presence of indicated concentrations of 1 and ETP. Error bars correspond to SD from triplicate experiments.

Conclusions.

TDP2 is a newcomer in DNA repair, viral replication, and potentially oncogenesis.1,8 TDP2 excises the irreversible Top2 cleavage complexes that are produced by topoisomerase poison-based anti-cancer treatments.2 Therefore, TDP2 inhibitors, when administered in combination with Top2 inhibitors, should boost treatment efficacy, which is shown in the present study. In addition, because TDP2 has been implicated in transcription regulation in conjunction with Top2β,3 TDP2 inhibitors, such as the deazaflavin derivatives reported here and in a previous study,21 could serve as chemical probes to further elucidate the role of irreversible Top2 cleavage complexes for transcriptional regulation in neuronal development.3,15 The potential antiviral activity of the deazaflavin derivatives was not tested here, and further studies are warranted to test this possibility.

In the present study, we show that the deazaflavin derivatives selectively inhibit the human TDP2 enzyme in a competitive manner, suggesting their binding to the single-stranded DNA substrate groove,22,27 which also contain the two residues L313 and T296 critical for sensitivity to deazaflavins (Supporting Information Figure 2). The identification of these residues should be instrumental in cocrystal analyses and molecular docking studies, which will contribute to further optimizing this series of inhibitors.

Deazaflavin derivatives, which are not cytotoxic by themselves exhibit a synergistic effect when used in combination with ETP in the three cellular systems examined (human lymphoblastoid, human prostate, and avian lymphoblastoid cancer cells). They are the first TDP2 inhibitors to exhibit such cellular characteristics and represent a suitable platform to further advance the development of this new class of pharmaceutical agents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

All deazaflavin analogs (1–5) studied herein were synthesized according to reported method.21 All commercial chemicals were used as supplied unless otherwise indicated. Flash chromatography was performed on a Teledyne Combiflash RF-200 with RediSep columns (silica) and indicated mobile phase. All moisture sensitive reactions were performed under an inert atmosphere of ultrapure argon with oven-dried glassware. 1H NMR was recorded on a Varian 600 MHz spectrometer. Mass data were acquired on an Agilent TOF II TOS/MS spectrometer capable of ESI and APCI ion sources. All tested compounds have a purity ≥95%.

2,4-Dioxo-10-[3-(1H-tetrazol-5-yl)phenyl]pyrimido[4,5-b]-quinoline-8-carbonitrile (1).

1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.28 (s, 1H), 9.18 (s, 1H), 8.43 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.30 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 8.14 (s, 1H), 7.95 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (s, 1H). HRMS-ESI (+) m/z calculated for C19H11N8O2: 383.0999 [M + H]. Found: 383.0991.

10-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-2,4-dioxo-pyrimido[4,5-b]quinoline-8-carbonitrile (2).

1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.21 (s, 1H), 10.03 (s, 1H), 9.13 (s, 1H), 8.39 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.87 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.12 (s, 1H), 7.03 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H). HRMS-ESI (+) m/z calculated for C18H11N4O3: 331.0826 [M + H]. Found: 331.0821.

2,4-Dioxo-10-phenyl-pyrimido[4,5-b]quinoline-8-carbonitrile (3).

1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.25 (s, 1H), 9.17 (s, 1H), 8.42 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.67 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.00 (s, 1H). HRMS-ESI (+) m/z calculated for C18H11N4O2: 315.0877 [M + H]. Found: 315.0876.

8-Chloro-10-(4-hydroxyphenyl)pyrimido[4,5-b]quinoline-2,4-dione (4).

1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.11 (s, 1H), 10.03 (s, 1H), 9.10 (s, 1H), 8.25 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.02 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.70 (s, 1H). HRMS-ESI (+) m/z calculated for C17H11ClN3O3: 340.0483 [M + H]. Found: 340.0479.

10-Phenylpyrimido[4,5-b]quinoline-2,4(3H,10H)-dione (5).

1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.07 (s, 1H), 9.13 (s, 1H), 8.23 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.75–7.68 (m, 3H), 7.64 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 6.71 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H). HRMS-ESI (+) m/z calculated for C17H12N3O2: 290.0924 [M + H]. Found: 290.0929.

Proteins.

Human TDP2 recombinant proteins, wild type and mutants, were expressed and purified in bacterial systems (Bioinnovatise, Rockville, MD). Murine, fish, and worm TDP2 proteins were expressed in bacteria and purified essentially as previously described.22

Cells.

DT40 wild type cells were a generous gift from Dr. Takeda (Kyoto University). DU145 cells were obtained from the Developmental Therapeutics Program (NCI). TK6 TDP2 KO cells were generated using a guide RNA, 5′-CCAAGAAGGTCCAAACTTCG-3′, targeting the TDP2 catalytic site. The left and right arms were amplified using F1/R1 (F1:5′- GCGAATTGGGTACCGGGCCAATGGTGAATTGGTGTTTAATGGGTAC-3′ and R1:5′-CTGGGCTCGAGGGGGGGCCCCTCTTCT GCTGCTGCTCTGAAAAATA-3′) and F2/R2 (F2:5′-TGGGAAGCTTGTCGACTTAACTGTGCAACTTAGATATAATATTGTAA-3′ and R2:5′-CACTAGTAGGCGCGCCTTAATGGAGTGAGAAGCAAATGGAAATCT-3′) primers, respectively. Resulting fragments were assembled with either DT-ApA/NEOR or DT-ApA/PUROR having been digested ApaI and AflII, using a GeneArt Seamless cloning kit (Invitrogen). Gene target events were confirmed by genomic PCR using two sets of primers: F3/R3 for NEOR (F3:5′-AACCTGCGTGCAATCCATCTTGTTCAATGG-3′ and R3:5′-CCACAGAAATGTACTATTGTATTACCTCTA-3′) and F4/R3 for PUROR (F4:5′-GTGAGGAAGAGTTCTTGCAGCTCGGTGA-3′).

Recombinant TDP2 Assay.

TDP2 reactions were carried out as described previously23 with the following modifications. A 18-mer single-stranded oligonucleotide DNA substrate (α32P-cordycepin-3′-labeled)23 containing a 5′-phosphotyrosine (TY19) was incubated at 1 nM with 25 pM recombinant human TDP2 (REC hTDP2) to obtain 30–40% cleavage in the absence or presence of an inhibitor for 15 min at RT in the reaction buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 80 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 40 μg/mL BSA, and 0.01% Tween 20. Reactions were terminated by the addition of 1 volume of gel loading buffer [99.5% (v/v) formamide, 5 mM EDTA, 0.01% (w/v) xylene cyanol, and 0.01% (w/v) bromophenol blue]. Samples were subjected to a 16% denaturing PAGE with multiple loadings at 12 min intervals. Gels were dried and exposed to a PhosphorImager screen (GE Healthcare). Gel images were scanned using a Typhoon 8600 (GE Healthcare), and densitometry analyses were performed using the ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare).

TDP2 Assays with Whole Cell Extracts.

Ten-million cells (1 × 107), either human, chicken DT40 wild type, or knockout for TDP2 and complemented with human TDP2, were collected, washed, and centrifuged. Cell pellets were then resuspended in 100 μL of CelLytic M cell lysis reagent (SIGMA-Aldrich C2978). After 15 min on ice, lysates were centrifuged at 12 000g for 10 min, and supernatants were transferred to a new tube. Protein concentrations were determined using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Invitrogen), and whole cell extracts were stored at −80 °C. The TY19 single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide containing a 5′-phosphotyrosine (see above) was incubated at 1 nM with 10–20 μg/mL of whole cell extract to obtain 30–40% cleavage in the absence or presence of inhibitor for 15 min at RT in the reaction buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 80 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 40 μg/mL BSA, and 0.01% Tween 20. Reactions were terminated and samples analyzed similarly to the recombinant TDP2 assay (see above).

Kinetics Experiments.

To determine the kinetic parameters for the inhibition of TDP2 by 1, 10 pM of TDP2 was incubated at RT with of 5, 10, 20, and 800 nM of cold TY19 substrate in the absence or presence of 30, 50, and 150 nM of 1 in the reaction buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 80 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 40 μg/mL BSA, and 0.01% Tween 20. All reactions were spiked with 1 nM of 32P-labeled TY19. The extent of reaction progression was followed in a time-dependent manner and terminated at different times by adding 1 volume of gel loading buffer. Samples were analyzed with 16% denaturing PAGE, and the initial portions of the reaction curves were fitted to a linear equation to approximate the pre-steady-state reaction velocities using the Prism software (Graph-pad). A Lineweaver–Burk plot was then generated with the pre-steady-state reaction velocities and the corresponding substrate concentrations.

Drug Combination Experiments.

Drug cellular sensitivity was measured as previously described.16 Briefly, cells were continuously exposed to various drug concentrations for 72 h in triplicate. Two hundred DT40 cells/well or 10,000 TK6 cells/well were seeded into a 384-well white plate (PerkinElmer) in 40 μL of medium. Cell viability was determined at 72 h by adding 20 μL of ATPlite solution (ATPlite 1-step kit, PerkinElmer). After 5 min incubation, luminescence was measured on an EnVision Plate Reader (PerkinElmer). The ATP level in untreated cells was defined as 100%, and viability of treated cells was defined as ATP level of treated cell/ATP level of untreated cells × 100.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was partially supported by the Faculty Research Development Grant (to H.A. and Z.W.) of the Academic Health Center, University of Minnesota, by JSPS Core-to-Core Program, A. Advanced Research Networks and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute (Z01 BC 006161-17LMP).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acschembio.5b01047.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Pommier Y, Huang SY, Gao R, Das BB, Murai J, and Marchand C. (2014) Tyrosyl-DNA-phosphodiesterases (TDP1 and TDP2). DNA Repair 19, 114–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Cortes Ledesma F, El Khamisy SF, Zuma MC, Osborn K, and Caldecott KW (2009) A human 5′-tyrosyl DNA phosphodiesterase that repairs topoisomerase-mediated DNA damage. Nature 461, 674–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Madabhushi R, Gao F, Pfenning AR, Pan L, Yamakawa S, Seo J, Rueda R, Phan TX, Yamakawa H, Pao PC, Stott RT, Gjoneska E, Nott A, Cho S, Kellis M, and Tsai LH (2015) Activity-Induced DNA Breaks Govern the Expression of Neuronal Early-Response Genes. Cell 161, 1592–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Virgen-Slane R, Rozovics JM, Fitzgerald KD, Ngo T, Chou W, van der Heden van Noort GJ, Filippov DV, Gershon PD, and Semler BL (2012) An RNA virus hijacks an incognito function of a DNA repair enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, 14634–14639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Koniger C, Wingert I, Marsmann M, Rosler C, Beck J, and Nassal M. (2014) Involvement of the host DNA-repair enzyme TDP2 in formation of the covalently closed circular DNA persistence reservoir of hepatitis B viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, E4244–4253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Pype S, Declercq W, Ibrahimi A, Michiels C, Van Rietschoten JG, Dewulf N, de Boer M, Vandenabeele P, Huylebroeck D, and Remacle JE (2000) TTRAP, a novel protein that associates with CD40, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-75 and TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAFs), and that inhibits nuclear factor-kappa B activation. J. Biol. Chem 275, 18586–18593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Pei H, Yordy JS, Leng Q, Zhao Q, Watson DK, and Li R. (2003) EAPII interacts with ETS1 and modulates its transcriptional function. Oncogene 22, 2699–2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Li C, Fan S, Owonikoko TK, Khuri FR, Sun SY, and Li R. (2011) Oncogenic role of EAPII in lung cancer development and its activation of the MAPK-ERK pathway. Oncogene 30, 3802–3812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Do PM, Varanasi L, Fan S, Li C, Kubacka I, Newman V, Chauhan K, Daniels SR, Boccetta M, Garrett MR, Li R, and Martinez LA (2012) Mutant p53 cooperates with ETS2 to promote etoposide resistance. Genes Dev. 26, 830–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Cope N, Harold D, Hill G, Moskvina V, Stevenson J, Holmans P, Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC, and Williams J. (2005) Strong evidence that KIAA0319 on chromosome 6p is a susceptibility gene for developmental dyslexia. Am. J. Hum. Genet 76, 581–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Francks C, Paracchini S, Smith SD, Richardson AJ, Scerri TS, Cardon LR, Marlow AJ, MacPhie IL, Walter J, Pennington BF, Fisher SE, Olson RK, DeFries JC, Stein JF, and Monaco AP (2004) A 77-kilobase region of chromosome 6p22.2 is associated with dyslexia in families from the United Kingdom and from the United States. Am. J. Hum. Genet 75, 1046–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Luciano M, Lind PA, Duffy DL, Castles A, Wright MJ, Montgomery GW, Martin NG, and Bates TC (2007) A haplotype spanning KIAA0319 and TTRAP is associated with normal variation in reading and spelling ability. Biol. Psychiatry 62, 811–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Paracchini S, Thomas A, Castro S, Lai C, Paramasivam M, Wang Y, Keating BJ, Taylor JM, Hacking DF, Scerri T, Francks C, Richardson AJ, Wade-Martins R, Stein JF, Knight JC, Copp AJ, Loturco J, and Monaco AP (2006) The chromosome 6p22 haplotype associated with dyslexia reduces the expression of KIAA0319, a novel gene involved in neuronal migration. Hum. Mol. Genet 15, 1659–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Gomez-Herreros F, Romero-Granados R, Zeng Z, Alvarez-Quilon A, Quintero C, Ju L, Umans L, Vermeire L, Huylebroeck D, Caldecott KW, and Cortes-Ledesma F. (2013) TDP2-dependent non-homologous end-joining protects against topoisomerase II-induced DNA breaks and genome instability in cells and in vivo. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Gomez-Herreros F, Schuurs-Hoeijmakers JH, McCormack M, Greally MT, Rulten S, Romero-Granados R, Counihan TJ, Chaila E, Conroy J, Ennis S, Delanty N, Cortes-Ledesma F, de Brouwer AP, Cavalleri GL, El-Khamisy SF, de Vries BB, and Caldecott KW (2014) TDP2 protects transcription from abortive topoisomerase activity and is required for normal neural function. Nat. Genet 46, 516–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Maede Y, Shimizu H, Fukushima T, Kogame T, Nakamura T, Miki T, Takeda S, Pommier Y, and Murai J. (2014) Differential and Common DNA Repair Pathways for Topoisomerase I- and II-Targeted Drugs in a Genetic DT40 Repair Cell Screen Panel. Mol. Cancer Ther 13, 214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Zeng Z, Sharma A, Ju L, Murai J, Umans L, Vermeire L, Pommier Y, Takeda S, Huylebroeck D, Caldecott KW, and El-Khamisy SF (2012) TDP2 promotes repair of topoisomerase I-mediated DNA damage in the absence of TDP1. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 8371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Gao R, Das BB, Chatterjee R, Abaan OD, Agama K, Matuo R, Vinson C, Meltzer PS, and Pommier Y. (2014) Epigenetic and genetic inactivation of tyrosyl-DNA-phosphodiesterase 1 (TDP1) in human lung cancer cells from the NCI-60 panel. DNA Repair 13, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Sousa FG, Matuo R, Tang SW, Rajapakse VN, Luna A, Sander C, Varma S, Simon PH, Doroshow JH, Reinhold WC, and Pommier Y. (2015) Alterations of DNA repair genes in the NCI-60 cell lines and their predictive value for anticancer drug activity. DNA Repair 28, 107–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Alvarez-Quilon A, Serrano-Benitez A, Lieberman JA, Quintero C, Sanchez-Gutierrez D, Escudero LM, and Cortes-Ledesma F. (2014) ATM specifically mediates repair of double-strand breaks with blocked DNA ends. Nat. Commun 5, 3347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Raoof A, Depledge P, Hamilton NM, Hamilton NS, Hitchin JR, Hopkins GV, Jordan AM, Maguire LA, McGonagle AE, Mould DP, Rushbrooke M, Small HF, Smith KM, Thomson GJ, Turlais F, Waddell ID, Waszkowycz B, Watson AJ, and Ogilvie DJ (2013) Toxoflavins and deazaflavins as the first reported selective small molecule inhibitors of tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase II. J. Med. Chem 56, 6352–6370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Shi K, Kurahashi K, Gao R, Tsutakawa SE, Tainer JA, Pommier Y, and Aihara H. (2012) Structural basis for recognition of 5′-phosphotyrosine adducts by Tdp2. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 19, 1372–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Gao R, Huang SY, Marchand C, and Pommier Y. (2012) Biochemical Characterization of Human Tyrosyl-DNA Phosphodiesterase 2 (TDP2/TTRAP): a Mg2+/Mn2+-dependent phosphodiesterase specific for the repair of topoisomerase cleavage complexes. J. Biol. Chem 287, 30842–30852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Prichard MN, Prichard LE, and Shipman C Jr. (1993) Strategic design and three-dimensional analysis of antiviral drug combinations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 37, 540–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Prichard MN, and Shipman C Jr. (1990) A three-dimensional model to analyze drug-drug interactions. Antiviral Res. 14, 181–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Gao R, Schellenberg MJ, Huang SY, Abdelmalak M, Marchand C, Nitiss KC, Nitiss JL, Williams RS, and Pommier Y. (2014) Proteolytic Degradation of Topoisomerase II (Top2) Enables the Processing of Top2-DNA and -RNA Covalent Complexes by Tyrosyl-DNA-phosphodiesterase 2 (TDP2). J. Biol. Chem 289, 17960–17969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Schellenberg MJ, Appel CD, Adhikari S, Robertson PD, Ramsden DA, and Williams RS (2012) Mechanism of repair of 5′-topoisomerase II-DNA adducts by mammalian tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 2. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 19, 1363–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.