We read with great interest some articles recently published in Joint Bone Spine [1], [2], [3]. Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is estimated to be older adults’ most common inflammatory rheumatic disease [4], [5]. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is the main cytokine involved and characteristically increases during PMR relapses [6]. On the other hand, among the different pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-6 is the most frequently reported one to be increased during the so-called “cytokine storm” induced by severe acute respiratory syndrome due to coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [7]. We like to share this recent clinical observation.

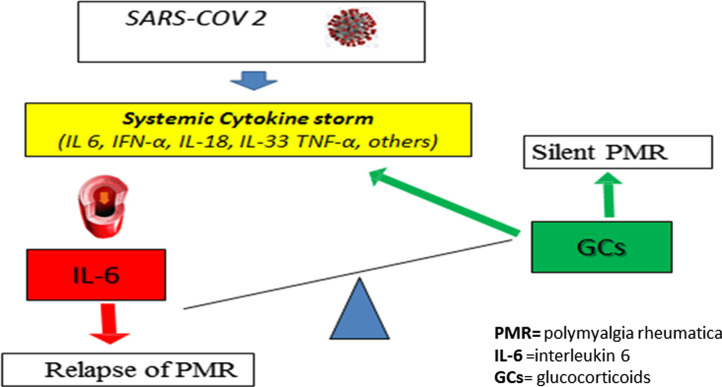

An 83 y.o. Caucasian male patient affected with PMR in remission with prednisone 12.5 mg/day, had a relapse of disease two days before SARS-CoV-2. Diagnosis of relapse was made according to PMR activity score (PMR-AS) proposed by Leeb and Bird [8]. At that time, a laboratory control revealed IL-6 concentrations = 800 pg/ml (v.n. < 50). IL-6 concentrations was 200 pg/ml at the time of first diagnosis of PMR. During hospitalization, intra-venous tocilizumab, twice within 12 h at 8 mg/kg body-weight, was administrated. Both acute respiratory distress and PMR relapse resolved, and IL-6 concentrations normalized. We cannot exclude that relapse of PMR and SARS-CoV-2 was a coincidence. However, it is worth highlighting that after discharging, patient is still taking prednisone for PMR in line with the dosage reduction schedule proposed in 2015 by a EULAR/ACR collaborative initiative [9]. To date, he takes prednisone 7.5 mg/day. He has had no other relapse of PMR. We hypothesized that the sharp increase of IL-6 serum concentrations induced by SARS-CoV-2 shifted the balance favored by prednisone (as depicted in Fig. 1 ), so as to lead a relapse of PMR. This would indirectly be confirmed by the need to continue prednisone after patient's discharge.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the underbalance following the overproduction of interleukin-6 induced by SARS-CoV-2 in patient with polymyalgia rheumatica in remission after glucocorticoid therapy.

To the best of our knowledge, data on the risk of rheumatic relapses in patients with overlapping SARS-CoV-2 are still scarce in published literature, probably because the rheumatologic symptoms are hidden by other manifestations of the infection, and these patients are usually managed by non rheumatologists. In their editorial, Wendling et al. [2] highlighted the role of interleukin 17 as possible link between SARS-Cov-2 and reactive arthritis. On the other hand, as our case report suggests, in other rheumatic diseases (such as PMR) in which IL-6 plays a more prominent role, the altered regulation of innate immunity induced by SARS-CoV-2 might represent a specific, ad hoc trigger.

We acknowledge that cytokines are only a side of the complex interactions underlying the virus interaction with human immune system, interactions that also involve adaptive immunity [10]. We hope that a better knowledge of these interactions will give us the keys to solve these emerging physio-pathological issues.

Informed consent

Written informed consent for publication of clinical details was obtained from the patient.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- 1.Salvatierra J., Martínez-Peñalver D., Salvatierra-Velasco L. CoVid-19 related dactyitis. Joint Bone Spine. 2020;87:660. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wendling D., Verhoeven F., Chouk M., Prati C. Can SARS-CoV-2 trigger reactive arthritis? Joint Bone Spine. 2020;88:105086. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2020.105086. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quartuccio L., Semerano L., Benucci M., Boissier M.C., De Vita S. Urgent avenues in the treatment of COVID-19: Targeting downstream inflammation to prevent catastrophic syndrome. Joint Bone Spine. 2020;87:191–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manzo C. Incidence and prevalence of Polymyalgia Rheumatica (PMR): the importance of the epidemiological context. The Italian case. Med sci (Basel) 2019;7:92. doi: 10.3390/medsci7090092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manzo C., Camellino D. Polymyalgia rheumatica: diagnostic and therapeutic issues of an apparently straightforward disease. Recenti Prog Med. 2017;108:221–231. doi: 10.1701/2695.27559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pulsatelli L., Boiardi L., Pignotti E., et al. Serum interleukin-6 receptor in polymyalgia rheumatica: a potential marker of relapse/recurrence risk. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1147–1154. doi: 10.1002/art.23924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ragab D., Salah Eldin H.S., Taeimah M., et al. The COVID-19 Cytokine Storm; What We Know So Far. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1446. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leeb B.F., Bird H.A. A disease activity score for polymyalgia rheumatica. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1279–1283. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.011379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dejaco C., Singh Y.P., Perel P., et al. 2015 Recommendations for the management of polymyalgia rheumatica: a European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1799–1807. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azkur A.K., Akdis M., Azkur D., et al. Immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and mechanisms of immunopathological changes in COVID-19. Allergy. 2020;75:1564–2158. doi: 10.1111/all.14364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]