Abstract

In the present report, we have described the abrupt pivot of Vascular Quality Initiative physician members away from standard clinical practice to a restrictive phase of emergent and urgent vascular procedures in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The Society for Vascular Surgery Patient Safety Organization queried both data managers and physicians in May 2020 to discern the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Approximately three fourths of physicians (74%) had adopted a restrictive operating policy for urgent and emergent cases only. However, one half had considered “time sensitive” elective cases as urgent. Data manager case entry was affected by both low case volumes and low staffing resulting from reassignment or furlough. A sevenfold reduction in arterial Vascular Quality Initiative case volume entry was noted in the first quarter of 2020 compared with the same period in 2019. The downstream consequences of delaying vascular procedures for carotid artery stenosis, aortic aneurysm repair, vascular access, and chronic limb ischemia remain undetermined. Further ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown will likely be amplified if resumption of elective vascular care is delayed beyond a short window of time.

Keywords: Clinical practice shift, COVID-19, Physician survey, VQI arterial registry

Article Highlights.

-

•

Type of Research: A Society for Vascular Surgery Patient Safety Organization survey of clinical practice effects resulting from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic with a retrospective review of the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) arterial registry volume in the first quarter of 2019 and 2020

-

•

Key Findings: Of the respondents, 74% had restricted their operating policy to urgent and emergent procedures because of the COVID-19 pandemic. One half of the surgeons reported performing “time sensitive” elective procedures despite the policy shift, including large abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. A sevenfold reduction in the VQI arterial registry procedure volume was noted in the first quarter of 2020 compared with the same period in 2019, with data manager reassignment and/or furlough and case volume decline contributing to the reduction.

-

•

Take Home Message: The VQI arterial case volume activity and registry data entry were sharply reduced during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic because many vascular surgeons had adopted a restrictive policy for elective vascular procedures.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has altered our personal and professional lives in ways that were inconceivable only months ago. As COVID-19 infections caused by the SARS-CoV2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) virus spread across the United States, health care workers found themselves on the front lines of the battle for their patients and, in all too many cases, their personal well-being and survival.1

On March 13, 2020, the American College of Surgeons issued a recommendation to “review all scheduled elective procedures with a plan to minimize, postpone, or cancel electively scheduled operations.”2 On March 14, 2020, Dr Jerome Brown, the Surgeon General of the United States, reiterated this plea with a tweet “Hospital & healthcare systems, PLEASE CONSIDER STOPPING ELECTIVE PROCEDURES until we can #FlattenTheCurve!”3

The vascular surgery community was quick to respond to these dramatic events. As a result, the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) Patient Safety Organization (PSO) Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) noted a precipitous decline in registry volumes. The SVS PSO conducted two surveys early in the COVID-19 pandemic to assess changes in practice. First, we surveyed VQI data managers to discern the effect of the pandemic on their workflow and queried the historical volume of the M2S registry. Second, we surveyed VQI physicians about their practice changes in response to the pandemic. In the present practice management study, we report the findings and discuss the implications.

Status quo disrupted

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, vascular surgeons regularly performed arterial procedures comprising elective, urgent, and emergent indications for aortic aneurysm repair, lower extremity interventions, vascular access, trauma, and carotid artery stenosis. Urgent and emergent cases will typically comprise ∼30% to 50% of an active vascular surgery case mix.4

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted this status quo, threatening the timeliness and efficiency of care. Physicians were confronted with the dilemma of potentially exposing patients to COVID-19 by bringing them into a hospital or office setting. This influenced physicians to rethink potential exposure and the usage of hospital resources that could possibly be needed for COVID-19–related admissions.5 Outpatient vascular services and office-based laboratories providing diagnostic and therapeutic services were also dramatically affected. In a global survey by Ng et al,6 86.9% of vascular surgeons stated that their outpatient services had been either suspended or downscaled in response to the pandemic. With little to no preparation, the clinical practice for vascular surgeons had to shift from preferred face-to-face interactions and adopt an “only if your life (or limb) depends on it” policy for direct patient contact. Postoperative follow-up care and chronic disease management evolved rapidly through “remote” medicine. Examples of these include telemedicine through telephone calls, video chats, and interactions via electronic medical record systems. This rapid pivot in vascular practice management was only possible because of the advances in technology and internet access.

A change in practice

During the SVS webinar conducted on March 27, 2020, Dr Benjamin Starnes clearly and passionately stated “the ultimate role of the surgeon in a pandemic is to help grow hospital capacity by not operating... to preserve space, staff and stuff [personal protective equipment].”7 Vascular surgeons across the United States responded to this “call to inaction” by developing triage plans for elective, urgent, and emergency procedures.8 , 9 In addition, surgeons and trainees were called on to serve in a variety of new roles to help combat the pandemic. The abrupt shutdown of elective surgery in all forms allowed hospitals and health care systems to increase capacity and formulate surge plans in anticipation of an influx of patients with COVID-19.10

REAL-TIME data of survey of data managers

To determine the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on VQI workflow, we conducted a survey of VQI center data managers. The survey was sent on May 8, 2020 and closed on June 15, 2020. We received 225 responses from 1282 surveys sent (17.5%). The results have been detailed in Appendix A (online only) and summarized as follows:

-

•

Most respondents reported that hospital staff, and not contracted vendors, were responsible for data collection, with 70% having only one data abstractor per center.

-

•

At the time of the survey in early May, <10% of centers had restricted procedures to emergencies, and >90% of centers were performing urgent and emergent operations. In addition, 40% of the centers had continued to perform elective procedures, with minimal volume reduction. Elective case resumption was scheduled for May 11 to 24, 2020 by 53% and May 25 to June 7, 2020 by 13% of the remaining centers; 26% of the centers were unable to provide a definitive time for restarting elective procedures.

-

•

Most (75%) of the abstractors had not been furloughed or reassigned, and 30% of the respondents reported having lower case volumes at the time of the survey.

-

•

Variation in the methods for long-term follow-up was noted. One third of the centers had been continuing face-to-face follow-up, with the remainder using telephone interviews, telephone and/or video calls, or electronic medical record review. Finally, 12% of the respondents stated that follow-up was currently not possible.

Survey of VQI member physicians

To assess the COVID-19 effects on practice, we conducted a seven-question survey of VQI physicians. The survey was sent on June 2, 2020 and closed on July 20, 2020 (Appendix B, online only). We received 105 responses from the 4631 surveys sent (2.2%). The results have been summarized as follows:

-

•

A variety of nonmutually exclusive sources were used to guide changes in operating policy, including intuition (61%), societal guidelines (51%) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services guidelines (30%).

-

•Most (74%) VQI physicians reported an operating policy shift to urgent and emergent cases only, with 14% restricting their practice to emergency procedures only. However, one half of the respondents performed “elective” procedures, although restrictive policies had been enacted, because of perceived need. Both symptomatic urgent and “time sensitive” elective cases were interpreted by respondents in their comments:

- Elective procedures listed as time sensitive primarily encompassed dialysis access (de novo; 48%), dysfunctional access (72%), asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair (41%), and peripheral vascular interventions for threatened grafts (61%).

-

•

Only 3% of respondents cited performing procedures for claudication.

-

•

Most centers conducted mandatory COVID-19 testing before surgery (79%), although 11% had reserved testing for symptomatic patients.

-

•

The 5.5-cm size threshold for AAA repair in men remained unchanged for 52% of the respondents. Physicians who had altered their size thresholds for elective AAA repair cited a diameter of >6 cm (26%) and >7 cm (21%) for men and >5.5 cm (26%) and >6.5 cm (21%) for women.

Survey analysis

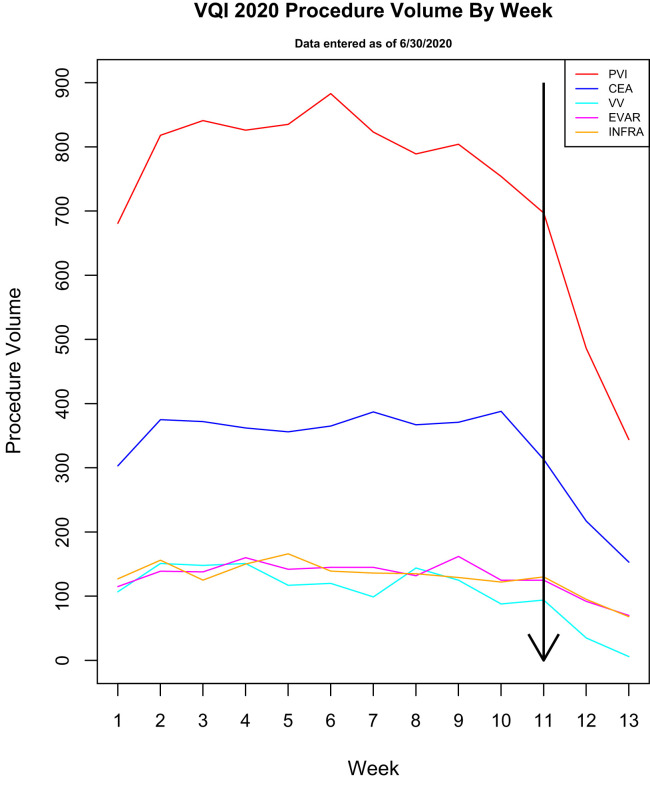

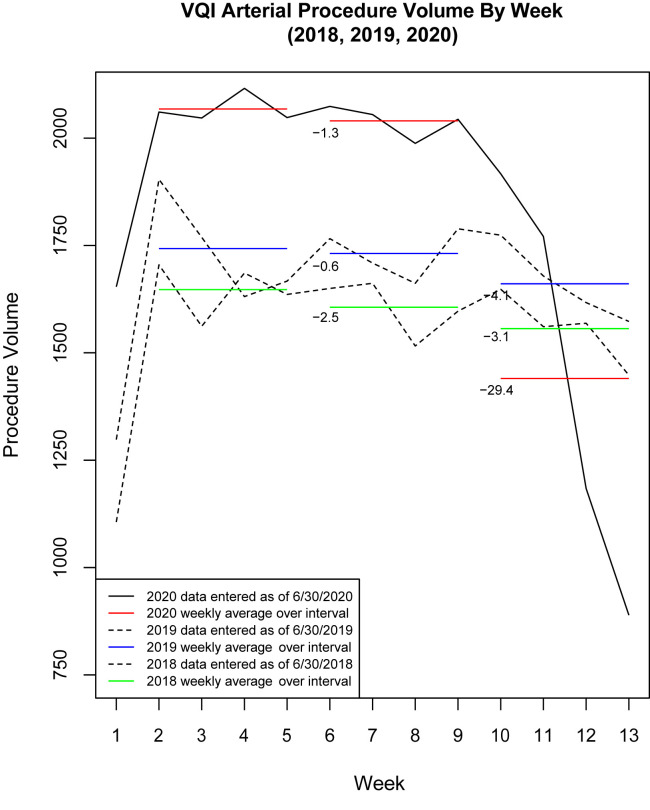

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the SVS VQI noted a precipitous decline in operations entered in the arterial registries on a week by week basis compared with similar periods in 2018 and 2019 (Figs 1 and 2 ). The reduction in registry volumes for peripheral vascular interventions, carotid endarterectomy, and endovascular AAA repair demonstrated the most significant decline compared with other procedures. Although delays in data entry could explain a part of this decline, such delays could not account for the nearly sevenfold decrease in the average weekly procedure volume from weeks 6 to 9 to weeks 10 to 13 in 2020 (from 2040.25 to 1440.25; a 29.4% decrease) compared with the same periods in 2019 (from 1731.5 to 1660.75; a 4.1% decrease; Fig 2). Given the similarity in the data from 2018 and 2019, we attributed a significant part of the decline to the procedural shutdown across all registries for this period. The finding that the decline resulted from the shutdown and not a delay in data entry is supported by the report from >75% of data managers that they had not been reassigned or furloughed. Thus, given the reduced case volumes, they likely had sufficient time for case entry. The SVS VQI was quick to respond to this change by inserting COVID-19 variables into all procedural registries and long-term follow-up forms completed September 2020 to capture the effects of COVID-19 on outcomes. The SVS VQI has also partnered with the Vascular Surgery COVID-19 Collaborative to learn more about the effects of COVID-19 and the practice changes on vascular patients.11

Fig 1.

Graph showing Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) data of weekly vascular surgical procedure volumes during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Week 1, January 4; and week 5, February 1. Line at week 11 indicates steep decrease in case volume after March 15, 2020. CEA, Carotid endarterectomy; EVAR, endovascular aneurysm repair; INFRA, infrainguinal bypass; PVI, peripheral vascular intervention; VV, varicose vein.

Fig 2.

Graph comparing 4-week average procedural volume in 2018 and 2019 for arterial registries to Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) data during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in 2020. Numbers on red and blue lines represent percentage of change in 4-week volume for during weeks 6 to 9 and weeks 10 to 13. Week 1, January 4; week 5, February 1; and week 11, March 15, when national shutdown occurred.

COVID-19 and peripheral arterial complications

Recent research has demonstrated the ability of COVID-19 to produce thrombotic complications, which result from the cytokine storm triggered by a systemic immune response.12 Thus, patients have a greater risk of developing a hypercoagulable state, precipitating arterial and venous thrombosis. Excessive inflammation, platelet activation, endothelial dysfunction, and stasis have been postulated as mechanisms.13 Although venous thromboembolic events have seemed to be more common and have received the most attention, no vascular bed seems to be spared, with numerous case reports documenting acute arterial ischemia, including aortic, femoral–popliteal, tibial, radial–ulnar, and mesenteric arterial thrombosis.14, 15, 16, 17 Case studies have shown that although the elective procedure volume was negatively affected, presentations of arterial and venous thromboses as complications of COVID-19 infection will continue to present challenges for vascular surgeons.

One of the projected changes in vascular surgery because of the COVID-19 pandemic is the continued shift to endovascular aneurysm repair instead of open repair for patients with ruptured AAAs. Adoption of percutaneous entry and the decreased operative time, reduction in perioperative mortality, and shorter length of stay are all rational arguments that became magnified during the COVID-19 pandemic to minimize the strain on hospital resource usage.18 , 19 Monitoring the method of repair for ruptured AAAs over time will be needed to determine whether this trend persists.

Of concern has been the number of patients delaying treatment of health issues from fear of contracting COVID-19 by seeking medical attention. Emergency department visits for acute cardiac events have experienced a notable decline during the COVID-19 pandemic, and a reciprocal increase in deaths has been reported.20 Investigations of the health care effects resulting from COVID-19 should also consider the indirect collateral morbidity and mortality rates resulting from patient reluctance or refusal to seek timely medical attention.21 , 22

Discussion

The downstream secondary effects of the suspension of operations are unknown. If temporary, the ability to recover a backlog of elective services should be able to be compensated for over time through enhanced practice hours and/or weekend activity. As public health measures work to flatten the first phase of the epidemic, vascular surgeons, like all citizens, look forward to resuming their normal practice. In addition, health care systems are looking ahead to a return to the business of medicine and are developing guidelines for a return to operating.10 Although we understand that drastic measures were required in the early phase of the pandemic, we also acknowledge that the derivative effects on vascular health care are, at present, unknown and could be significant. If the reduction in elective surgery continues, patients will inevitably be susceptible to the natural history of untreated disease. Delays in vascular treatment could potentially contribute to increases in limb loss from peripheral arterial disease, stroke from cerebrovascular disease, aneurysm rupture from untreated aneurysm expansion, and vascular access morbidity and mortality from access thrombosis or prolonged catheter use, to name just a portion of the possible adverse outcomes. Continued interruptions of routine vascular care could jeopardize the long-term health of vascular patients.

The present analysis was limited by the subjective nature of an elective survey and our attempt to correlate these results with the actual workload volumes in the VQI procedure-driven registry. Although the data manager survey response rate was favorable (17.5%), the VQI physician response rate was low (2.2%). Therefore, the responses might not reflect a large swath of practice patterns in the VQI. The survey mailings lacked the center identification in the responses. Thus, associating the data manager replies to center work volumes was not possible. We also could not determine the changes in center work volumes for those who did not respond to the survey. Attributing a nearly sevenfold difference in case volume reductions to the lack of data entry alone should be viewed with caution because the events surrounding the responses to the COVID-19 crisis is clearly multifactorial, considering that 40% of the centers had continued elective work and one of four data managers were reassigned or furloughed during the study period. Data manager designation by center can be as physician office staff/hospital employee or third party contractor entering registry data at the point of care, at patient discharge, or retrospectively. Although the VQI does not have a data manager certification program, we have a thorough onboarding process with data abstraction training, integrated help texts, and readily available resources for consultation and guidance. The VQI performs regular audits against the claims data and source data and interrater reliability exercises to ensure the highest level of data integrity.23

The changes in data manager workflow and long- term follow-up will require consideration for future quality reporting and VQI clinical research studies. The results from the VQI physician survey illustrated a clear shift to urgent and emergent procedures and a thoughtful reconsideration of priorities. Although we were unable to analyze any geographic or regional distribution to the survey responses, VQI centers are in all 50 states. A more detailed reporting of regional differences in practice variation during the pandemic restrictions will require further trend analysis near the end of 2020, not available at the time of our writing.

Conclusions

The vascular surgery community response to the global COVID-19 pandemic during the national shutdown resulted in a dramatic reduction in elective case volumes, with most practitioners performing emergency and select urgent procedures only. This resulted in a sevenfold reduction in registry case volume compared with the similar periods in 2018 and 2019. The potential effects of delaying treatment on vascular disease remain unknown and require further analysis. The VQI is moving forward with regional virtual meetings that will provide a forum for study, reflection, communication, and discussion.

Given the uncertain future during the next 1 to 2 years, the U.S. health care system will face ongoing challenges that likely will be unevenly distributed over place and time owing to the variations in state and local guidelines for practice restrictions. Localized outbreaks with clusters of infection or a resurgence of COVID-19 cases could necessitate regional responses, including a reduction in elective surgery. Research into the ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic on all facets of vascular care will help us provide the best care to our patients. Vascular surgeons should form partnerships with public health experts and epidemiologists to study the COVID-19 pandemic's ongoing effects and our response to the public health care crisis. Most importantly, we must look for new and innovative methods to practice in what will likely be a “new abnormal.” Continued collaboration and ingenuity will be required to navigate this uncharted territory.

Author contributions

Conception and design: JN, AM, DB, JE, GL

Analysis and interpretation: JN, AM, DB, KH, JE, GL

Data collection: KH

Writing the article: JN, AM, DB, KH, JE, GL

Critical revision of the article: DB, KH, JE, GL

Final approval of the article: JN, AM, DB, KH, JE, GL

Statistical analysis: KH

Obtained funding: Not applicable

Overall responsibility: GL

JN and AM contributed equally to this article and share co-first authorship.

JE and GL contributed equally to this article and share co-senior authorship.

Footnotes

Author conflict of interest: none.

Additional material for this article may be found online at www.jvascsurg.org.

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the JVS policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

Additional material for this article may be found online at www.jvascsurg.org.

Appendix (online only).

References

- 1.National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases Cases in the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html Available at:

- 2.American College of Surgeons COVID-19: Recommendations for Management of Elective Surgical Procedures. ACS: COVID-19 and Surgery. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-surgery Available at:

- 3.Office of the U.S. Surgeon General. Brown J (@Surgeon_General). Tweet. Hospital & healthcare systems, PLEASE CONSIDER STOPPING ELECTIVE PROCEDURES until we can #FlattenTheCurve! March 14, 2020, 8:14 am. https://twitter.com/surgeon_general/status/1238798972501852160?lang=en Available at:

- 4.American College of Surgeons COVID-19 Guidelines for Triage of Vascular Surgery Patients. ACS: COVID-19 and Surgery. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-case/vascular-surgery Available at:

- 5.Al-Jabir A., Kerwan A., Nicola M., Zaid A., Mehdi K., Sohrabi C., et al. Impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on surgical practice—part 2 (surgical prioritisation) Int J Surg. 2020;79:233–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng J.J., Ho P., Dharmaraj R.B., Wong J.C.L., Choong A.M.T.L. The global impact of COVID-19 on vascular surgical services. J Vasc Surg. 2020;71:2182–2183.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lumsden A., Hodgson K., Irshad A., Forbes T.L., Starnes B.W., McDevitt D., et al. Early vascular surgeon experiences with COVID-19 (Kim Hodgson, MD & Alan Lumsden, MD) March 27, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6R33Rv8s9w4&ab_channel=HoustonMethodistDeBakeyCVEducation Available at:

- 8.Society for Vascular Surgery COVID-19 resources for members. https://vascular.org/news-advocacy/covid-19-resources Available at:

- 9.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Press release: CMS Releases Recommendations on Adult Elective Surgeries, Non-Essential Medical, Surgical, and Dental Procedures During COVID-19 Response. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-releases-recommendations-adult-elective-surgeries-non-essential-medical-surgical-and-dental Available at:

- 10.American College of Surgeons Joint Statement: Roadmap for Resuming Elective Surgery after COVID-19 Pandemic. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/roadmap-elective-surgery Available at:

- 11.Department of Surgery, School of Medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus Vascular Surgery COVID-19 Collaborative (VASCC) https://medschool.cuanschutz.edu/surgery/specialties/vascular/research/vascular-surgery-covid-19-collaborative/vascc) Available at:

- 12.Gralinski L.E., Baric R.S. Molecular pathology of emerging coronavirus infections. J Pathol. 2015;235:185–195. doi: 10.1002/path.4454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bikdeli B., Madhavan M.V., Jimenez D., Chuich T., Dreyfus I., Driggin E., et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2950–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kashi M., Jacquin A., Dakhil B., Zaimi R., Mahe E., Tella E., et al. Severe arterial thrombosis associated with COVID-19 infection. Thromb Res. 2020;192:75–77. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mestres G., Puigmacià R., Blanco C., Yugueros X., Esturrica M., Riambau V. Risk of peripheral arterial thrombosis in COVID-19. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72:756–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.04.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomez-Arbelaez D., Ibarra-Sanchez G., Garcia-Gutierrez A., Comanges-Yeboles A., Ansuategui-Vicente M., Gonzalez-Fajardo J.A. COVID-19-related aortic thrombosis: a report of four cases [e-pub ahead of print] Ann Vasc Surg. 2020;67:10–13. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2020.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lodigiani C., Iapichino G., Carenzo L., Cecconi M., Ferrazzi P., Sebastion T., et al. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res. 2020;191:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faizer R., Weinhandl E., El Hag S., Rosenberg M., Reed A., Fanola C. Decreased mortality with local versus general anesthesia in endovascular aneurysm repair for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm in the Vascular Quality Initiative database. J Vasc Surg. 2019;70:92–101.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2018.10.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verikokos C., Lazaris A.M., Geroulakos G. Doing the right thing for the right reason when treating ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms in the COVID-19 era. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72:373–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marijon E., Karam N., Jost D., Perrot D., Frattini B., Derkenne C., et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during the COVID-19 pandemic in Paris, France: a population-based, observational study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e437–e443. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30117-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhatt A.S., Moscone A., McElrath E.E., Varshney A., Claggett B., Bhatt D., et al. Declines in hospitalizations for acute cardiovascular conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multicenter tertiary care experience [e-pub ahead of print] J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teo K.C., Leung W.C.Y., Wong Y.K., Liu R., Chan A., Choi O., et al. Delays in stroke onset to hospital arrival time during COVID-19. Stroke. 2020;51:2228–2231. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eldrup-Jorgensen J., Wadzinski J. Data validity in the Society for Vascular Surgery Vascular Quality Initiative Registry. SOJ Surgery. 2019;6:1–5. www.symbiosisonline.org Available at: [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.