Abstract

Venous thromboembolism is prevalent in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Through systematic review and meta-analysis, we have investigated the differences in clinical characteristics and outcome of hospitalized COVID-19 patients with (+) and without (−) venous thromboembolism (VTE). 45 studies with a total of 8859 patients were included in the qualitative synthesis. Subsequently, 38 studies with a total of 7847 patients, were quantitatively analyzed. There was no mortality difference between the VTE (−) and VTE (+) hospitalized COVID-19 patients (RR1.32 (0.97, 1.79); 0.07; I2 64%, p < 0.001). Patients with VTE (+) were more likely to get admitted to the intensive care unit (RR1.77 (1.26, 2.50); p < 0.001; I2 63%, p = 0.03) and mechanically ventilated (RR 2.35 (1.22, 4.53); p = 0.01; I2 88%, p < 0.001). Moreover, male gender (RR 1.19 (1.14,1.24), p < 0.001; I2 0%, p = 0.68), increased the risk of VTE. Regarding patients lab values’, VTE (+) was significantly associated with higher white blood cell, neutrophil count, D-Dimer, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and C-reactive protein (CRP), along with prolonged prothrombin time. On the contrary, VTE (+) was associated with lower albumin and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR). This findings provide the initial framework for risk stratification of hospitalized COVID-19 patients with VTE.

Keywords: Venous thromboembolism, COVID-19, Clinical characteristics, Lab values, Mortality

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) is a highly contagious respiratory disease caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) resulting in a global pandemic status. At the time of this writing, it has already claimed more than 1.6 million lives and infected approximately 70 million people throughout the world [1]. Although many aspects of this multifaceted disease have been unraveled, much more are being explored. Notably, the coagulopathy associated with COVID-19, in which evidence is still emerging, has raised concerns as one of the most serious events during hospitalization with this disease [[2], [3], [4], [5]].

A previous study has shown that D-dimer, a primary marker of coagulopathy, was associated with higher mortality [5]. Furthermore, lung dissection and autopsy from COVID-19 decedents showed pulmonary microthrombi formation [6]. Therefore, several authors argued that Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), which is the most common complication of COVID-19, is caused by pulmonary endothelial dysfunction identified as pulmonary intravascular coagulopathy (PIC) or pulmonary thrombosis [7,8]. This argument is substantiated by several findings that the incidence of pulmonary embolism (PE) is more frequent than deep vein thrombosis (DVT) [9].

Data from previous reports have shown a higher incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 compared to with other diseases (10), despite prophylaxis anticoagulation had been applied [10,11]. This acute vascular complication might potentially impact morbidity and mortality of patients with COVID-19 during their hospitalization. Rapid growth of published work on this subject allows for a comprehensive analysis to reach a conclusion on this important issue.

This study aimed to systematically evaluate the impact of VTE on mortality in patients with COVID-19. Authors also scrutinized any clinical characteristics which potentially lead to developing VTE in this population during hospitalization. Thus, more attention can be given to these patients to reduce morbidity and mortality during hospitalization. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis that compare hospitalized COVID-19 patients with and without VTE.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

The predefined protocol was used for this review and in line with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA). We systematically searched and identified studies published between January 1, 2020 and November 23, 2020, through electronic searches using PubMed, Europe PMC, Proquest, Embase, and WHO Database. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free words were used to construct the search terms related to VTE (venous thromboembolism OR deep vein thrombosis OR pulmonary embolism), coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR 2019-nCoV). Eligible articles for further review were identified by screening of titles and abstracts, followed by a full-text review. In the case of multiple publications, the most recent and complete reports were included. Authors finalized the systematic literature review search on November 23, 2020. This study adhered to the PRISMA guideline.

2.2. Selection criteria

Articles eligibility was assessed by two independent investigators (JH and ICSP). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus with a third investigator (AC). The inclusion criteria of the article in this study included all research studies involving hospitalized patients with COVID-19 suffering VTE (DVT group and PE group only, non-specified VTE group, and specified VTE group), which dichotomized them into two groups, ie, COVID-19 patients with and without VTE. We excluded commentaries, non-research letter, reviews, and case reports/case series.

2.3. Data extraction

A standardized form was used to collect the information that consists of qualitative aspects of identified studies (the first author and publication year, geographic locations, and study design), basic profiles of the patients, VTE phenotypes, and any related comorbidities. Two authors performed data extraction independently (JH and ICSP). The primary outcome was all-cause mortality. The secondary outcome was intensive care unit (ICU) admission and mechanical ventilation support. In addition, we also extracted data regarding clinical characteristics (patient characteristics, comorbidities, prophylactic anticoagulation status (received/not), and laboratory findings). Data that was reported other than mean ± SD was transformed accordingly using a calculator (http://www.math.hkbu.edu.hk/∼tongt/papers/median2mean.html), derived from Wan et al. and Luo et al. studies [12,13]. The risk of bias of the included studies was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) clinical appraisal tool for prevalence studies by two independent authors and discrepancies were resolved via discussion [14].

2.4. Statistical analysis

Review Manager 5.4 (https://training.cochrane.org/online-learning/core-software-cochrane-reviews/revman) was used for the meta-analysis. To characterise the association between VTE and dichotomous variables, we calculated the pooled estimates and its 95% confidence interval in the form of risk ratios (RRs) using the Mantel-Haenzel formula. Whereas, to characterise the association between VTE and continuous variables, we calculated the pooled estimates in the form of a mean difference (MD) and its standard deviation. To account for interstudy variability regardless of the heterogeneity, a random-effects model was assigned. We used two-tailed p values with a significance set at ⩽ 0.05. To assess heterogeneity across studies, we used the inconsistency index (I2) with a value above 50% or p < 0.05 indicates significant heterogeneity, whereas I 2 <25% is considered low heterogeneity. A sensitivity analysis using the leave-one-out method was set to achieve statistical robustness and detect the source of heterogeneity. Finally, an inverted funnel-plot analysis was used to qualitatively detect any publication bias.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection and characteristics

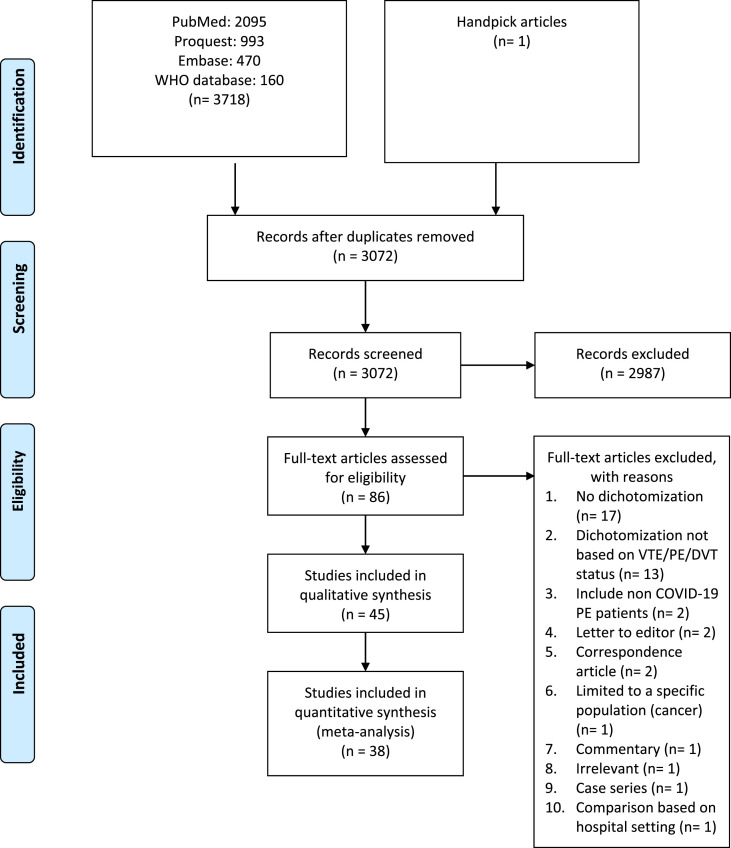

Figure one shows the study profile. Forty-five studies with a total of 8859 patients (3,10,16–58) were included in the qualitative synthesis. (supplementary file) Subsequently, based on a risk of bias analysis, eight studies were excluded (26, 28, 32,40, 42, 43,47,49) and only 38 studies (N = 7847 patients) were included in the quantitative synthesis. (Fig. 1 , Table 1 ). Seven studies were excluded in the quantitative synthesis, correspond to the result of the risk of bias analysis. All of the extracted variables and risk of bias analysis are in the supplementary file (Table S1 – 3).

Fig. 1.

Study profile [15].

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

|

Author |

Country | Study Design | Sample Size (Total = 12,132) |

VTE/PE/DVT (%) Total = 2029 |

Age (mean ± SD) years | Male (%) | BMI (mean ± SD) kg/m2 | HTN (%) | DM (%) | Obesity (%) | CVD (%) | Smokers (%) | Mortality (%) | LoS (mean ± SD) days | ICU admission | Mechanical Ventilation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torres A [17] | Mexico | cohort | 30 | DVT; 9 (30) | 60.3 ± 35 vs 55.6 ± 32.6 |

8 (89) vs 15 (71) |

32.4 ± 17 vs 29.4 ± 15.7 |

5 (56) vs 6 (29) |

2 (22) vs 11 (52) |

6 (66) vs 6 (29) |

1 (11) vs 4 (20) |

NA | 3 (33) vs 3 (14) |

7.5 ± 14 vs 12.3 ± 20.7 |

NA | NA |

| Santoliquido A [18] | Italy | cohort study | 84 | DVT; 10 (12) | 72.0 ± 11.3 vs 67.0 ± 13.8 |

7 (70) vs 54 (73) |

NA | 6 (60)vs 39 (52.7) |

1 (10) vs 17 (22.9) |

2 (20.0) vs 13 (17.5) |

0 (0.0) vs 11 (14.8) |

NA | NA | 6.2 ± 2.3 vs 5.7 ± 2.2 |

NA | NA |

| Ierardi A M [19] | Italy | prospective cohort |

234 | DVT; 25 (11) | 65 ± 10.28 vs 61.22 ± 14.57 |

NA | 27.23 ± 5.24 vs 29.59 ± 5.05 |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Mouhat B [20] | French | retrospective cohort |

162 | PE; 44 (27) | 66.52 ± 11.41 vs 65.22 ± 13.58 |

36 (81.6) vs 73 (61.9) |

NA | 21 (47.7) vs 59 (50) |

8 (18.2) vs 25 (21.2) |

14 (31.8) vs 28 (23.7) |

8 (18.2) vs 26 (22.) |

3 (6.8) vs 9 (7.6) |

NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pellens B [21] | Belgium | cross-sectional | 12 | DVT; 8 (67) | 62.4 ± 5.6 vs 65.5 ± 14.7 |

7 (87.5) vs 2 (50.0) |

NA | 3 (37.5) vs 2 (50) |

NA | 3 (37.5) vs 1 (25) |

0 (0) vs 2 (50) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ren B [22] | China | cross sectional | 48 | DVT; 36 (75) | 71.3 ± 13.13 vs 67 ± 12.6 |

21 (58.3) vs 2 (28.6) |

NA | 13 (36.1) vs 3 (42.9) |

10 (27.8) vs 2 (28.6) |

8 (22.2) vs 1 (14.3) |

NA | 10 (27.8) vs 2 (28.6) |

NA | NA | 22 (61.1) vs 4 (57.1) |

|

| Fang C [23] | London | retrospective cohort |

93 | PE; 41 (44) | 62.35 ± 10 vs 58.8 ± 13.7 |

28 (68) vs 32 (5,61) |

NA | 20 (49) vs 24 (46) |

14 (34) vs 24 (46) |

13 (32) vs 18 (35) |

2 (5) vs 7 (13) |

5 (12) vs 8 (15) |

6 (14.6) vs 5 (9.6) |

NA | 13 (31.7) vs 7 (13.5) |

NA |

| Fauvel C [24] | France | retrospective cohort |

1240 | PE; 103 (8) | 63 ± 16 vs 64 ± 17 |

73 (70.9) vs 648 (57.0) |

27.3 ± 5.6 vs 28.2 ± 6.3 |

44 (42.7) vs 515 (45.7) |

19 (18.4) vs 249 (22.0) |

9 (8.7) vs 124 (10.9) |

9 (8.9) vs 172 (15.4) |

9 (8.7) vs 1 142 (12.5) |

NA | 32 (31.1)c vs. 153 (13.5) |

25 (24.3)d vs. 83 (7.3) |

|

| Contou D [25] | France | retrospective cohort |

26 | PE; 16 (62) | 62.28 ± 24.4 vs 60.4 ± 23.2 |

14 (89) vs 8 (80) |

30.4 ± 19.5 vs 32.4 ± 15.5 |

9/16 (56) vs 6/10 (60) |

6 (38) vs 4 (40) |

7 (44) vs 3 (30) |

1 (6) vs 1 (10) |

NA | 11 (69) vs 2 (20) |

NA | NA | NA |

| Kampouri E [26] | Swiss | retrospective cohort |

429 | VTE; 27 (6) | 62.9 ± 8.2 vs 68.6 ± 19.3 |

22 (81.5) vs 224 (55.7) |

NA | NA | 6 (22.2) vs 99 (24.6) |

8 (29.6) vs 96 (23.9) |

2 (7.4) vs 36 (9.0) |

NA | 2 (7.4) vs 57 (14.2) |

22.5 ± 9.3 vs 8.6 ± 6 |

18 (66.7) vs 76 (18.9) |

18 (66.7) vs 55 (13.7) |

| Bompard F [27] | France | retrospective cohort |

135 | PE; 32 (24) | 68.6 ± 14 vs 63.35 ± 17.3 |

26 (81) va 68 (66) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4 (13) vs 12 (12) |

7 ± 6.2 vs 5.7 ± 3 |

12 (38) vs 12 (12) |

10 (31) vs 8 (8) |

| Avruscio G [28] | Italy | observational cohort |

85 | VTE; 43 (51) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 8 (19)vs 0 (0) |

NA | NA | NA |

| Gibson C J [29] | USA | prospective cohort |

72 | DVT; 12 (17) | NA | 9 (75) vs 40 (80) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 (8) vs 14 (27) |

NA | NA | NA |

| Koleilat I [30] | USA | retrospective case control |

135 | DVT; 18 (13) | 57.2 ± 12 vs 63.3 ± 15 |

11 (61.1) vs 61 (52.1) |

32 ± 6.9 vs 28.7 ± 6 |

13 (72.2) vs 81 (69.2) |

6 (33.3) vs 45 (38.5) |

NA | 1 (5.6) vs 15 (12.8) |

1 (5.6) vs 19 (16.4) |

2 (11.1) vs 18 (16.4) |

7.6 ± 5.2 vs 8.6 ± 5.9 |

NA | 10 (55.6) vs 41 (35.0) |

| Chang H [31] | USA | retrospective cohort |

188 | DVT; 58 (31) | 62 ± 16 vs 65 ± 14 |

44 (76) vs 78 (60) |

30.± 6.9 vs 30.1 ± 7.5 |

33 (57) vs 80 (62) |

16 (29) vs 50 (38) |

NA | 5 (9) vs 20 (15) |

13 (22) vs 28 (22) |

11 (19) vs 31 (23.8) |

22 ± 14 vs 21 ± 15 |

35 (61) c vs 63 (49) |

28 (48) d vs 57 (44) |

| Grillet F [32] | France | retrospective cohort |

100 | PE; 23 (23) | 67 ± 11 vs 66 6 ± 13 |

21 (91) vs 49 (64) |

NA | NA | 2 6 (26) vs 14 (18) |

NA | 10 (43) vs 29 (38) |

NA | NA | 17 (74) vs 22 (29) |

15 (65) vs 19 (25) |

|

| Chen J [33] | China | Retrospective study | 35 | PE; 10 (29) | 64.84 ± 12.47 vs 62.85 ± 12.58 |

6 (60) vs 9 (60) |

NA | 6 (60) vs 4 (27) |

3 (30) vs 2 (13) |

NA | 2 (20) vs 2 (13) |

2 (20) vs 4 (27) |

2/10 (20) vs 4/15 (27) |

NA | NA | NA |

| Hippensteel J A [34] | USA | Retrospective cohort | 91 | VTE; 24 (26.3) | 55 ± 13 vs 57 ± 17 |

14 (58) vs 39 (58) |

32.1 ± 8.5 vs 32.5 ± 10.4 |

NA | 7 (34) vs 21 (33) |

NA | 3 (14) vs 17 (27) |

4 (20) vs 12 (22) |

2/24 (9) vs 20/67 (30) |

26 ± 7 vs 16 ± 10 |

NA | 92 (22) vs 82 (55) |

| Choi J J [35] | USA | Retrospective cohort | 1739 | VTE; 123 (0.7) | 68.05 ± 12.9 vs 65.66 ± 17.88 |

85 (69.1) vs 948 (58.7) |

NA | 73 (59.3) vs 905 (56) |

45 (36.6) vs 490 (30.3) |

43 (35) vs 482 (29.8) |

14 (11.4) vs 269 (16.6) |

NA | 23 (18.7) vs 303 (18.8) |

20.72 ± 20.25 vs 7.75 ± 8.16 |

NA | 18 (15) d vs. 65 (4) |

| Capaccione K M [36] | USA | Cross sectional | 126 | PE; 24 (19) | NA | 9/24 (38) vs 44/102 (43) |

NA | 7 (29) vs 38 (37) |

6 (25) vs 13 (13) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Larsen K [37] | French | Observational | 35 | VTE; 7 (20) | 58.27 ± 16.53 vs 69.36 ± 16.40 |

7 (100) vs 20/(71.4) |

NA | 3 (42.9) vs 12 (42.9) |

1 (14.3) vs 5 (17.9) |

1 (14.3) vs 4 (14.3) |

1 (14.3) vs 8 (28.6) |

0 (0) vs 2 (7.1) |

NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Desborough MJR [38] | UK | Retrospective study | 66 | VTE; 10 (15.2) | 54.1 ± 5.48 vs 59.35 ± 11.41 |

8/(80) vs 40 (71) |

29.89 ± 6.02 vs 28.06 ± 8.37 |

5 (50) vs 25 (45) |

2 (20) vs 25 (45) |

NA | 1 (10)vs 6 (11) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | 9 (90) vs 43 (77) |

| Ooi M.W.X [39]. | UK | Retrospective study | 84 | PE; 32 (38.1) | 60.97 ± 11.64 vs 59.00 ± 19.07 |

17 (53) vs 25 (48) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Maatman T K [40] | US | Observational | 109 | VTE; 31 (28.4) | 60 ± 17 vs 62 ± 15 |

20 (65) vs 42 (54) |

34.7 ± 12.7 vs 34.8 ± 11.5 |

17 (55) vs 57 (73) |

10 (32) vs 33 (42) |

NA | 3 (10) vs 14 (18) |

5 (16) vs 28 (36) |

8 (25.8) vs 19 (24.4) |

NA | NA | NA |

| Artifoni M [41] | France | Retrospective cohort | 71 | VTE; 16 (22.5) | 60.2 ± 31.05 vs 62.06 ± 20.94 |

11 (68.7) vs 32 (58.2) |

27.22 ± 2.93 vs 28 ± 6.17 |

3 (19) vs 26 (47) |

0 (0) vs 14 (25) |

NA | NA | 0 (0) vs 6 (12) |

NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Benito N [42] | Spain | Retrospective cohort | 76 | PE; 32 (42.1) | NA | 20 (62.5) vs 31 (70.5) |

NA | 15 (46.9) vs 19 (43.2) |

6 (18c8) vs <!d-Soft-enter replaced as Paramark--> 6 (13.6) |

8 (27.6) vs 13 (32.5) |

NA | NA | 3 (9.4) vs 5 (11.4) |

NA | 15 (46.9)c vs 10 (22.7) |

14 (43.8)d vs 8 (18.2) |

| Poyiadji N [43] | Detroit, USA | Retrospective cohort | 328 | PE; 72 (28.1) | 59 ± 15 vs 62 ± 16 |

49 (68.1) vs 45 (17.6) |

NA | 57 (79.2) vs 61 (23.8) |

40 (55.6) vs 38 (14.8) |

58 (80.6) vs 44 (17.1) |

4 (5.6) vs 9 (3.5) |

28 (38.9) vs 40 (15.6) |

6 (8.3) vs 10 (3.9) |

9.4 ± 7.5 vs 9.0 ± 8.0 |

NA | NA |

| Rodriguez P D [44] | Madrid, Spain |

Prospective cohort | 156 | DVT; 23 (14.7) | 66.7 ± 15.2 vs 68.4 ± 14.4 |

14 (60.9) vs 88 (66.2) |

27.7 ± 5.5 vs 26.8 ± 3.9 |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 12 ± 11.06 vs 9.7 ± 8.24 |

NA | NA |

| Rali P [45] | US | Retrospective study | 147 | VTE; 25 (17) | NA | 15 (60) vs 57 (46) |

NA | NA | 7 (28) vs 51 (41) |

NA | 5 (20) vs 18 (14) |

NA | 12 (48) vs 27 (22) |

NA | NA | NA |

| Ameri P [46] | Italy | Retrospective observational | 689 | PE; 52 (7.5) | 63.8 ± 10.6 vs 67.6 ± 13.4 |

41 (78.8) vs 437 (68.6) |

29.6 ± 6.3 vs 27 ± 5.2 |

25 (48.1) vs 364 (57.6) |

13 (25.0) vs 144 (22.8) |

NA | 6 (11.5) vs 137 (21.7) |

NA | 18 (34.6) vs 147 (23) |

NA | NA | NA |

| Pizzolo [16] | Italy | Cross sectional | 43 | DVT; 12 (28) | 75.7 ± 31 vs 60.5 ± 49 |

8 (67) vs 21 (68) |

NA | 7 (58.3) vs 16 (51.6) |

4 (33.3) vs 2 (6.5) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Dujardin RWG [47] | Netherlands | Retrospective study | 127 | VTE; 53 (41.7) | 62.7 ± 12.2) vs 62.3 ± 11.3) |

40 (75.5) vs 58 (78.1) |

27.2 (4.8) vs 27.1 (3.8) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Middeldorp S [48] | Netherland | Retrospective study | 198 | VTE; 39 (19.7) | 62 ± 10 vs 60 ± 15 |

27 (69) vs 103 (65) |

82 (74,93) vs 84 (75, 95) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Chen S [49] | China | Retrospective study | 88 | DVT; 40 (45) | 63 ± 10.7 vs 64 ± 13 |

25 (63) vs 29 (60) |

NA | 12 (30) vs 19 (40) |

6 (15) vs 3 (6) |

NA | 2 (5) vs 0 (0) |

NA | 12 (30) vs 8 (17) |

25.9 ± 9.99 vs 22.7 ± 8.4 |

NA | NA |

| Cui S [50] | China | Observational study | 81 | VTE; 20 (25) | 68.4 ± 9.1 vs 57.1 ± 14.3 |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Soumagne T [51] | France & Belgium | Observational study | 375 | PE; 55 (15) | 61.1 ± 9.1 vs 63.9 ± 10.3 |

46 (84) vs 242 (76) |

29.6 ± 4.7 vs 29.8 ± 5.6 |

26 (53) vs 190 (59) |

12 (22) vs 87 (27) |

NA | 8 (15) vs 28 (9) |

NA | 16 (29) vs 118 (37) |

NA | NA | NA |

| Meiler S [52] | Canada | Retrospective study | 50 | VTE; 14 (28) | 60.5 (9.7) VS 76.1 (94.5) | 10 (30) vs 23 (70) |

NA | 5 (25) vs 15 (75) |

4 (40) vs 6 (60) |

NA | 0 (0) vs 4 (11) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Le Jeune S [53] | France | Retrospective study | 42 | DVT; 8 (19) | 77.7 ± 15.2 vs 61.5 ± 19.0 |

4 (50) vs 19 (55.9) |

NA | 6 (75) vs 14 (41.2) |

3 (37.5) vs 10 (29.4) |

NA | 2 (25) vs 5 (14.7) |

1 (12.5) vs 4 (11.8) |

2 (25) vs 0 (0) |

NA | 0 (0)c vs 3 (8.8) |

NA |

| Taccone F.S. [54] | Belgium | Retrospective study | 40 | PE; 13 (32) | 57 ± 6 vs 63 ± 7.9 |

11 (85) vs 17 (63) |

NA | 10 (77) vs 18 (67) |

1 (8) vs 4 (15) |

6 (46) vs 10 (37) |

NA | 2 (15) vs 4 (15) |

6 (46) vs 14 (52) |

NA | NA | NA |

| Trimaille A [55] | France | Retrospective study | 289 | VTE; 49 (17) | 61.4 ± 15.0 vs 62.4 ± 17.4 |

33 (67.3) vs 138 (57.5) |

NA | 25 (51.0) vs 107 (44.6) |

11 (22.4) vs 48 (20.0) |

21 (45.7) vs 80 (37.2) |

NA | 3 (6.1) vs 8 (3.3) |

23 (47.9) vs 67 (27.9) |

16.5 ± 8.7 vs 11.4 ± 7.1 |

21 (43.8)c vs 51 (21.3) |

NA |

| Diaz V [56] | Spain | Retrospective study | 242 | PE; 73 (30) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Longhitano Y [57] | Italy | Observational study | 74 | VTE; 21 (28) | 66.7 ± 16.78 vs 69.40 ± 14.54 |

15 (71.4) vs 29 (54.7) |

NA | NA | 5 (23.8) vs 11 (20.7) |

1 (4.8) vs 6 (11.3) |

8 (38.1) vs 24 (45.3) |

NA | 3 (14.3) vs 9 (16.9) |

45.7 ± 15.3 vs 29 ± 19.5 |

NA | NA |

| Yu Y [58] | China | Retrospective study | 142 | DVT: 50(35) | NA | NA | 23.8 ± 2.4 vs 23.8 ± 2.7 | 24 (48) vs 37 (40.2) |

7 (14.0) vs 12 (13.0) |

NA | 6 (12.0) vs 10 (10.9) |

3 (6.0) vs 6 (6.5) |

27 (54.0) vs 6 (6.5) |

NA | NA | NA |

| Zermatten [59] | Switzerland | retrospective study | 100 | VTE; 22 (22) | NA | NA | NA | 9 (40.9) vs 41 (56.9) |

5 (22.7) vs 20 (27.8) |

5 (22.7) vs 20 (27.8) |

0 (0.0) vs 9 (12.5) |

NA | 6 (26.1) vs 9 (20.0) |

16.1 ± 18.2 vs 18.4 ± 18.1 |

19 (86.4) VS 47 (65.3) |

NA |

| Zhang L [3] | China | Cross secctional |

143 | DVT; 66 (46) | 67 ± 12 vs 59 ± 16 |

36 (54.5) vs 38 (49.4) |

23.6 ± 2.9 vs 23.6 ± 3.1 |

28 (42.4) vs 28 (36.4) |

13 (19.7) vs 13 (16.9) |

NA | 9 (13.6) vs 8 (10.4) |

NA | 23 (34.8) vs 9 (c1.7) |

NA | 12 (18.2) vs 3 (3.9) |

NA |

a. All vs data represent VTE (+) vs VTE (−). Regarding studies from the same country, all of them were conducted in different hospitals.

b. VTE: Venous thromboembolism, PE: Pulmonary embolism, DVT: Deep vein thrombosis, SD: Standar deviation, BMI: Body mass index, HTN: Hypertension, DM: Diabetes mellitus, CVD: Cardiovascular disease, LoS: length of stay, ICU: Intensive care unit.

Indicates outcome for ICU admission. Otherwise, proportion of patients with and without VTE whom admitted to the ICU.

Indicates outcome for mechanical ventilation. Otherwise, proportion of patients with and without VTE whom mechanically ventilated.

3.2. Venous thromboembolism and mortality

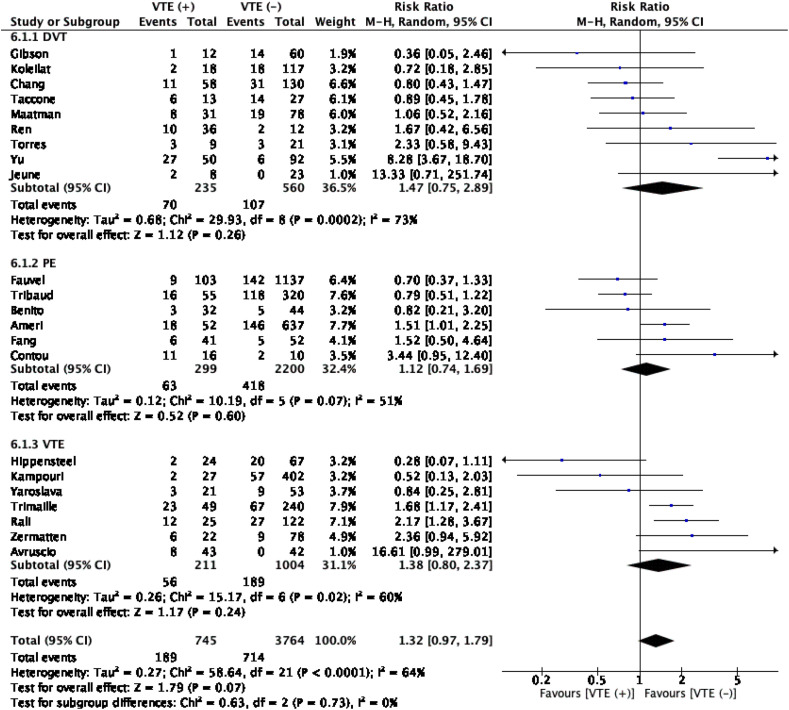

The meta-analysis with a pooled subject of 4509 patients showed that complication of VTE in patients with COVID-19 was not associated with an increased in-hospital mortality (RR1.32 (0.97, 1.79); 0.07; I 2 64%, p < 0.001). Moreover, introducing subgroups consist of DVT, PE, and VTE into the analysis did not alter the significance (Table 2 , Fig. 2 ).

Table 2.

Meta-analysis of the mortality in patients with VTE.

| Variable | Risk Ratio (95%CI); p-value | Heterogeneity (I2; p-value) | Number of Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | 1.32 (0.97, 1.79); 0.07 | 64%; <0.001 | 22 |

a. CI; confidence interval, SA; sensitivity analysis by leave-one-out method.

Fig. 2.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) and mortality. The meta-anaylsis did not show significant association between VTE and mortality. Further subgroup analysis was performed and did not yield any significant association in these subgroups. DVT: deep vein thrombosis, PE: pulmonary embolism, VTE; venous thromboembolism.

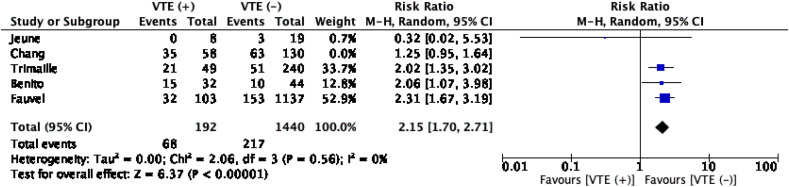

3.3. Venous thromboembolism and ICU admission

The meta-analysis with a pooled subjects of 1820 patients showed that VTE increased the risk of ICU admission significantly. (RR1.77 (1.26, 2.50); p < 0.001; I 2 63%, p = 0.03). Nonetheless, the heterogenity was considerably high. Upon a sensitivity analysis by excluding the Chang et al. study, heterogeneity was reduced to zero without altering the significance (RR 2.15 (1.70, 2.71); p < 0.001; I 2 0%, p = 0.56) (Table 3 , Fig. 3 ). This heterogeneity can be explained that, except for the Jeune et al. study, other studies were involving PE (Benito and Fauvel et al.) and VTE patients. Upon further inspection, the majority of VTE events in the Trimaille et al. study consist of PE patients. Therefore, it is unsurprising because patients with pulmonary embolism, undoubtedly mandate more intensive monitoring and a higher level of care. Furthermore, due to limited number of studies included, we did not perform a subgroup analysis for this association.

Table 3.

Meta-analysis of the secondary outcomes in patients with VTE.

| Variable | Risk Ratio (95%CI); p-value | Heterogeneity (I2; p-value) | Number of Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICU Admission | 1.77 (1.26, 2.50); <0.001 | 63%; 0.03 | 5 |

| ICU Admission SA | 2.15 (1.70, 2.71); <0.001 | 0%; 0.56 | 4 |

| Mechanical Ventilation | 2.35 (1.22, 4.53); 0.01 | 88%; <0.001 | 4 |

| Mechanical Ventilation SA | 3.27 (2.46, 4.35); <0.001 | 0%; 0.65 | 3 |

Fig. 3.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) and ICU admission. The meta-analysis showed that VTE incidence was significantly associated with admission to the ICU.

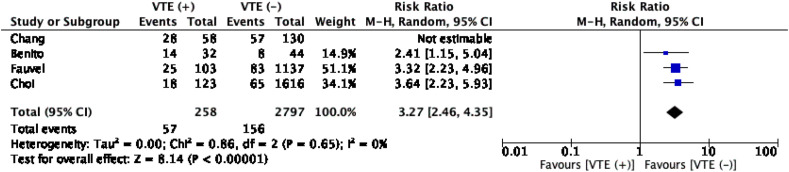

3.4. Venous thromboembolsim and mechanical ventilation

The meta-analysis with pooled subjects of 3055 patients showed that patients with VTE were more likely to get mechanically ventilated. (RR 2.35 (1.22, 4.53); p = 0.01; I 2 88%, p < 0.001). Nonetheless, high heterogeneity was noted, and upon a sensitivity analysis by excluding the Chang et al. study, heterogeneity was reduced to zero without altering the significance (RR 3.27 (2.46, 4.35); p < 0.001; I 2 0%, p = 0.65) (Table 3, Fig. 4 ). This heterogeneity can be largely explained that other studies included were PE patients, which in part, might reflect a more severe COVID-19 disease. Moreover, due to limited number of studies included, we did not perform a subgroup analysis for this association.

Fig. 4.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) and mechanical ventilation.

3.5. Clinical characteristics associated with VTE

There were 51 variables that provided information on patient characteristics, pre-existing comorbidities, other risk factors of VTE, and laboratory findings have been analyzed (Table 3, Table 4 ). There were only thirteen variables associated with VTE, of which eight of them included less than ten studies (see Table 5 ).

Table 4.

Summary of meta-analyses of demographic profiles, comorbidities, and clinical manifestations associated with incidence of VTE.

| Variable | Risk Ratio (95%CI)/Mean Difference (SD)a; p-value | Heterogeneity (I2; p-value) | Number of Studies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | ||||

| Gender, male | 1.19 (1.14, 1.24); <0.001 | 0%; 0.68 | 34 | |

| Age (years) | 0.02 (−1.57, 1.61); 0.98 | 64%; <0.001 | 33 | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| DM | 0.91 (0.77, 1.07); 0.24 | 28%; 0.08 | 29 | |

| Arterial hypertension | 0.99 (0.92, 1.07); 0.85 | 0%; 0.87 | 24 | |

| Obesity | 1.10 (0.93, 1.29); 0.26 | 0%; 0.98 | 12 | |

| Smoking | 0.89 (0.60, 1.31); 0.55 | 0%; 0.66 | 7 | |

| COPD | 0.85 (0.58, 1.25); 0.41 | 0%; 0.60 | 12 | |

| CVD | 0.73 (0.49, 1.08); 0.12 | 0%; 0.77 | 10 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.83 (0.65, 1.06); 0.14 | 0%; 0.50 | 5 | |

| CKD | 0.78 (0.46, 1.33); 0.37 | 31%; 0.20 | 6 | |

| Risk factos of VTE | ||||

| Prior Surgery | 0.72 (0.35, 1.46); 0.36 | 0%; 0.91 | 3 | |

| Active Cancer | 1.09 (0.80, 1.49); 0.60 | 27%; 0.13 | 20 | |

| History of VTE | 1.02 (0.51, 2.04); 0.96 | 0%; 0.47 | 6 | |

a. Mean differences of COVID19 VTE (+) – COVID19 VTE (−); positive values refer to increase, and negative values refer to decrease.

b. CI; confidence interval, SD; standard deviation, DM; diabetes mellitus, COPD; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CVD; cardiovascular disease, CKD; chronic kidney disease, VTE; venous thromboembolism.

Table 5.

Summary of meta-analyses of laboratory findings associated with incidence of VTE.

| Variable | Mean difference (SD)a [VTE (+) – VTE (−)]; p-value |

Heterogeneity (I2, p-value) | Number of Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Findings | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | −0.10 (−0.32, 0.13); 0.87 | 33%; 0.08 | 20 |

| Hematocrit (%) | −1.00 (−2.29, 0.29); 0.13 | 0%; 0.88 | 3 |

| White blood cells (109/L) | 1.60 (1.02, 2.18); <0.001 | 57%; <0.001 | 23 |

| Platelet count (109/L) | 5.94 (−8.58, 20.47); 0.42 | 64%, <0.001 | 23 |

| Monocyte count | 0.07 (−0.25, 0.39); 0.67 | 9%; 0.001 | 2 |

| Neutrophil count | 1.89 (0.98, 2.81); <0.001 | 59%; 0.01 | 9 |

| Lymphocyte count | −0.12 (−0.24, 0.01); 0.07 | 85%; <0.001 | 17 |

| NLR | 3.54 (1.54, 5.54); <0.001 | 56%; 0.08 | 4 |

| Coagulation profile | |||

| D-Dimer (ug/mL) | 3.85 (2.62, 5.08); <0.001 | 95%; <0.001 | 26 |

| PT (second) | 0.67 (0.20, 1.14); 0.005 | 74%; <0.001 | 8 |

| PT% (%) | −1.79 (−4.26, 0.67); 0.15 | 0%; 0.71 | 5 |

| APTT (second) | 1.01 (−0.43, 2.44); 0.17 | 57%; 0.01 | 10 |

| APTT Ratio | −0.04 (−0.11, 0.03); 0.28 | 49%; 0.10 | 5 |

| INR | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.02); 0.51 | 6%; 0.37 | 5 |

| Liver enzyme, function, and acute phase reactants | |||

| ALT (U/L) | 7.68 (4.42, 10.93); <0.001 | 0%; 0.51 | 9 |

| AST (U/L) | 4.99 (−0.21, 10.19); 0.06 | 59%, 0.006 | 11 |

| LDH (U/L) | 53.07 (4.64, 101.5); 0.03 | 81%; <0.001 | 10 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | −0.04 (−0.12, 0.05); 0.39 | 48%; 0.08 | 6 |

| Albumin (g/L) | −2.82 (−4.82, −0.81); 0.006 | 73%; 0.002 | 6 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.14 (−0.11, 0.39); 0.27 | 63%; 0.07 | 4 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | −9.51 (−47.15, 28.14); 0.62 | 23%; 0.26 | 16 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 7.02 (0.10, 13.94); 0.05 | 99%; <0.001 | 13 |

| Ferritin (ug/L) | 282.06 (−19.48, 583.61); 0.07 | 80%; <0.001 | 9 |

| Blood gas | |||

| pH | 0.00 (−0.02, 0.01); 0.85 | 0%; 0.71 | 3 |

| PaO2 | −0.78 (-6.45, 4.90); 0.79 | 33%; 0.19 | 6 |

| PaCO2 | 6.50 (1.55, 11.46); 0.01 | 18%; 0.27 | 2 |

| PaO2/FiO2 | −25.08 (−49.53, −0.62); 0.04 | 0%; 0.91 | 3 |

| SpO2 | −4.23 (−9.08, 0.62); 0.09 | 0%; 0.76 | 2 |

| Renal function and electrolytes | |||

| SCr | 0.01 (−0.08, 0.09); 0.83 | 56%; 0.005 | 14 |

| eGFR | 0.73 (−3.62, 5.08); 0.74 | 0%; 0.74 | 5 |

| Urea | 3.30 (2.18, 4.42); <0.001 | 0%; 0.95 | 4 |

| Sodium | 0.42 (−0.94, 1.78); 0.54 | 0%; 0.70 | 2 |

| Potassium | 0.06 (−0.11, 0.24); 0.47 | 0%; 0.58 | 2 |

| Bicarbonate | 2.29 (−1.27; 5.86); 0.21 | 75%; 0.05 | 2 |

| Inflammatory markers | |||

| Procalcitonin | 0.12 (−0.05, 0.30); 0.17 | 89%; <0.001 | 4 |

| IL-6 | 36.51 (−55.07; 128.09); 0.43 | 98%; <0.001 | 5 |

| Cardiac markers | |||

| BNP | 19.42 (−55.23, 94.07); 0.61 | 41%; 0.18 | 3 |

| NTproBNP | 1271.97 (−534, 3077.94); 0.17 | 86%; 0.001 | 3 |

b. SD; standard deviation NLR; neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, PT; prothrombin time, APTT; activated partial thromboplastin time, INR; international normalized ratio, ALT; alanine aminotransferase, AST; aspartate aminotransferase, LDH; lactate dehydrogenase, CRP; C Reactive Protein, PaO2; arterial oxygen partial pressure, PaCO2; arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure, FiO2; fraction of inspired oxygen, SpO2; oxygen saturation, SCr; Serum Creatinine, eGFR; estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate, IL-6; interleukin – 6, BNP; brain natriuretic peptide, NTproBNP; N terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide.

Mean differences of COVID19 VTE (+) – COVID19 VTE (−); positive values refer to increase, and negative values refer to decrease.

The meta-analysis showed that the incidence of VTE in COVID-19 patients was more common in men (RR 1.19 (1.14, 1.24), p < 0.001; I2 0%, p = 0.68). Moreover, the incidence of VTE was not associated with an older age. Nevertheless, the heterogeneity was considerably high (MD 0.02 (−1.57, 1.61), p = 0.98; I2 64%, p < 0.001). A further inspection of this variable by introducing subgroups showed that older age was not associated with either DVT, PE, or VTE.

Regarding hematology profiles, higher white blood cell (WBC) was associated with VTE (MD 1.60 (1.02, 2.18); p < 0.001; I2 57%, p < 0.001). This association was still significant, even after introducing subgroups consist of DVT, PE, and VTE. Likewise, higher D-Dimer levels also showed a significant association with VTE (MD 3.85 (2.62, 5.08); p < 0.001; I2 95%, p < 0.001), which persisted at a subgroup level. Interestingly, a prolonged prothrombin time, a marker of the extrinsic pathway of a coagulation system, was also associated with VTE in general (MD 0.67 (0.20, 1.14); p = 0.005; I2 74%, p < 0.001). Nonetheless, upon further analysis by introducing a subgroup, the significance was maintained only for DVT, but not VTE.

Regarding liver enzyme, the meta-analysis revealed a significant association between a higher alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level and VTE (MD 7.68 (4.42,10.93); p < 0.001; I2 0%, p = 0.51). Moreover, a poor liver function, reflected by a lower albumin level was also associated with VTE (MD -2.82 (−4.82, −0.81); p = 0.006; I2 73%, p = 0.002). A higher level of C-reactive protein (CRP), an acute-phase reactant produced by the liver and a marker of inflammation was associated with VTE (MD 7.02 (0.10, 13.94); p = 0.05; I2 99%, p < 0.001). Upon subgroup analysis, the significance only persisted for the PE subgroup. Additionally, higher lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was also associated with VTE (MD 53.07 (4.64, 101.50); p = 0.05; I2 81%, p < 0.001). Subsequent subgroup analysis revealed that the significance was only for the VTE group and not DVT nor PE.

Other parameters, including arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure (PaCO2), the ratio between arterial oxygen partial pressure and fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2), and urea (Table 4). Nonetheless, these variables included a limited number of studies, which preclude them for subgroup analysis. Of interest, comorbidities and risk factors of VTE did not associate with COVID-19 patients that suffered VTE (Table 3). Further details of the analyses are available in supplementary file (Table S4 – 6).

3.6. Publication bias

An inverted funnel plot was utilized to assess the publication biases of variables with 10 or more studies. All variables, except gender, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cardiovascular disease (CVD), hypertension, and obesity showed an asymmetrical shape, which indicated publication biases (supplementary figure S1 – 19).

4. Discussions

Coagulopathy and VTE in COVID-19 are an emerging phenomenon with devastating consequences and are associated with poor prognosis in COVID-19 [60,61]. Thus, the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) has published interim guidelines for managing COVID-19’s coagulopathy [62]. They recommend that all hospitalized COVID-19 patients should be prophylactically anticoagulated.

The contributing factors for developing VTE according to Virchow’s triad consist of venous stasis, activation of coagulation, and vascular dysfunction/injury [63]. Venous stasis is commonly encountered in immobilized patients during hospitalization, particularly in the majority patients at ICU. Nonetheless, the incidence of VTE in ICU-admitted COVID-19 patients was higher compared to those with other diseases [[50], [10], [51]]. The other two factors are culmination of COVID-19 infection. SARS-CoV-2 can infect different organs through angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2), a glycoprotein metalloprotease that are ubiquitously found in human organs, particularly the endothelial cells, which traversed multiple organs and the pneumocytes [64,65]. The ensuing hypoxia caused by lung injury and ARDS in COVID-19 is a key factor of vascular fibrin deposition due to the increased early growth response-1 (Egr-1), which triggered tissue factor transcription/translation by mononuclear phagocytes and smooth muscle cells [66]. Furthermore, there is a role of bidirectional immunothrombosis, which is heightened inflammation will shift the balance to the procoagulant state by downregulating necessary anticoagulant pathways, while upregulating tissue factor expression necessary for thrombin generation [67].

In addition, SARS-CoV-2 downregulates ACE-2 after successfully infected cells, which is a counterregulatory enzyme of Angiotensin II (AngII) that maintains the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) balance in check [68]. This condition leads to a prothrombotic milieu. Interaction of AngII with angiotensin II type 1 receptor (ATR-1) will activate transcription factors, which increased adhesion and accumulation of neutrophils and macrophages to endothelial cells, and ultimately these cells will release proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines [69,70]. All of these will preserve the vicious cycle of inflammation and coagulopathy.

SARS-CoV-2 is also known to cause direct vascular injury via ACE-2 receptors. Case series of post mortem analysis of decedents due to COVID-19 confirmed diffuse endothelial inflammation, termed endothelitis, viral elements within endothelial cells, and inflammatory cell death [71]. Furthermore, morphologic and molecular changes from autopsied decedents due to COVID-19 ARDS showed severe endothelial injury with viruses present intracellularly and disrupted cell membranes [71]. Other hallmark features were thrombosis and microangiopathy, as well as intussusceptive angiogenesis, which were 9 times and 2.7 times, respectively, more common compared to patients with influenza [72].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis that assess the differences in clinical characteristics and outcome of hospitalized COVID-19 patients with and without VTE. The meta-analysis has shown that VTE was not associated with an increased mortality compared to the non-VTE group. As this study analyzed the pooling mortality risk ratio across all VTE phenomena, bias results were probably exist indicating a potential disparity of mortality rate between PE only group and DVT only group. Even the varied prognosis might be found among subtypes of PE including segmental, lobar, and central PEs [73]. However, an included study by Zhang et al. showed that COVID-19 patients with DVT had significant risks of developing adverse outcomes during their hospitalization, including increased proportion of deaths (23 [34.8%] vs 9 [11.7%], P = 0.001) [31]. Thus, it is reasonably justified to include DVT under the same umbrella term of VTE with PE in regard to the major risks.

Furthermore, this study reported that patients with VTE had significant adverse risks for clinical deterioration indicating to ICU admission and mechanical ventilator support. Interestingly, a study by Wang et al. showed that hospitalized patients with COVID-19 who fulfilled Padua Prediction Score of 4 or more, namely as high risk of developing VTE during hospitalization, also had increased risks of ICU admission and mechanical ventilation [74]. In addition, Rodriguez et al. reported that asymptomatic DVT was diagnosed by ultrasound in 23 out of 156 (14.7%) hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in non-ICU wards [75]. Therefore, special attention is needed to screen and risk stratify for VTE in every hospitalized patients with COVID-19 [60].

It is generally known that worse clinical outcomes of COVID-19 disproportionately affect the older population and male gender. However, the pathomechanisms remain elusive. In our meta-analysis, the male gender was associated with increased risk for developing VTE. This result might explain, in part, the rationale of worse prognosis in hospitalized males having this infection. Moreover, males also have a higher risk of first and recurrent VTE compared to woman counterparts, and it is hypothesized due to X or Y link mutation or mutation on a gene with a sex-specific effect [76].

On the contrary, our meta-analysis did not show an association between older age and VTE. This finding can be explained in part that patients of older age were at higher risk of achieving other competitive outcomes, such as in-hospital mortality, and therefore underplayed DVT and PE’s true incidence in this older population [[78], [79], [80]]. However, it is important to keep in mind that analysis from a population-based study of 25 years involving 2218 patients indicated that with an increasing age, there was a marked increase in VTE incidences in both sexes [80].

A previous meta-analysis by Tian et al. found that higher levels of D-Dimer, CRP, LDH, and ALT were associated with mortality in COVID-19 [81]. The same study also noted that a lower albumin level and higher WBC counts might predict mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. These biomarkers serve as an indicator of heightened inflammation and organ damages. Thus, in the setting of marked inflammation, the bidirectional role of immunothrombosis plays a crucial part in VTE’s pathomechanism. In our meta-analysis, higher D-Dimer, LDH, and CRP levels, along with lower albumin levels were associated with incidence of VTE during hospitalization with COVID-19. Interestingly, the relationship between hypoalbuminemia and coagulopathy has been raised by Violi et al. and further emphasized by Eloisio et al. Nonetheless, the cause-effect relationship between hypoalbuminemia and coagulopathy is currently unknown, and should be further explored with newer studies [82,83]. The association between prolonged prothrombin time (PT) and VTE incidence may be associated with extrahepatic vitamin K depletion induced by pneumonia, which is important in preventing thrombosis [84].

Our findings also showed that higher neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and neutrophil count was associated with VTE incidence in COVID-19 patients. Higher NLR was associated with disease severity and mortality in COVID-19. Both findings were implicated with an increased neutrophil extracellular traps (NET) level or NETosis [85]. This molecular substance played an integral part in inflammation propagation and microvascular thrombosis [86,87].

Surprisingly, this study did not yield any association between incidence of VTE and other comorbidities including diabetes, COPD, previous cardiovascular disease, history of VTE, smoking, and active cancer as well. Therefore, other explanations are needed to be explored regarding higher complications and poorer prognosis of COVID-19 in patients with these comorbidities [68,88]. Furthermore, we did not find any association between platelet counts and VTE, supporting findings that coagulopathy in COVID-19 is possibly a distinct entity compared to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), which is generally related to lower platelet counts [89]. Several reports noted that the thrombosis phenomena in COVID-19 occurred on an earlier phase, thus they do not reflect the state of consumptive coagulopathy [7,8,90,91]. Others proposed a staging for this abnormality identified as COVID-19-associated hemostatic abnormalities (CAHA) [92].

Finally, our qualitative synthesis showed that the types and dosages of anticoagulation for COVID-19 patients were heterogeneous. Previously, heparin administration for COVID-19 patients with sepsis-induced coagulopathy of ≥4 decreased the mortality rate [4]. Nonetheless, inappropriate dosing can lead to a higher rate of bleeding [93]. Thus, definite answers for these types of questions will have to wait for the ongoing clinical trials [94].

4.1. Limitations

This systematic review and meta-analysis have several limitations. First, not all of the studies reported the outcomes of interest, including mortality, ICU admission, and mechanical ventilation. Thus, authors can only perform a subgroup analysis only for mortality. Second, high heterogeneity for the majority of laboratory markers analyzed in this meta-analysis. Several factors, including temporal difference regarding when the lab is taken, inter-assay variability, inherent population differences, and disease severity, largely contributed to this marked heterogeneity. Third, due to many missing data from included studies, more studies are needed to confirm meta-analysis findings that consisted of fewer studies. Thus, authors cannot fully elucidate the representative clinical characteristics associated with VTE in COVID-19 patients. Fourth, authors could not rule out publication bias for significant variables with less than ten studies, per the Cochrane handbook [95]. Also, most of the included studies came from western countries and mainland China, which preclude generalization for other populations. Moreover, we did not preprint databases in our search strategy, which potentially excluded important studies. Nonetheless, it is a measure we undertook to prevent the inclusion of fraudulent studies.[96] Finally, the studies included in the analysis were predominantly retrospective in design.

5. Conclusions

Venous thromboembolism is a common complication encountered in patients with COVID-19 during hospitalization. The incidence of VTE was associated with ICU admission and mechanical ventilation. Additionally, male gender, higher levels of WBC, neutrophil count, NLR, D-Dimer, LDH, and CRP, prolonged PT, and lower albumin levels were associated with increased risks for developing VTE in this population. Further researches are needed to investigate the association between in-hospital or longer-term mortality and each subtype of PE (segmental/lobal/central) in patients with COVID-19.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Authors contribution

JH took full responsibility for the project, including creating the concept, designing the study, data accuracy, as well as writing the whole manuscript. JH and ICSP acquired the data. JH, ICSP, IC, SL, HFHD, performed extensive research on the topic. All authors contributed to manuscript writing. AC, LPS reviewed and revised the manuscript. HFHD and IC completed data conversion. JH performed the statistical analysis. JF reviewed the statistical reports and manuscript. All authors approve this manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to send our gratitude to Quinta Febryani Handoyono, MD for her assistance in figure preparation.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tru.2021.100037.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Weekly epidemiological update - 15 December 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update---15-december-2020

- 2.The Lancet Haematology COVID-19 coagulopathy: an evolving story. Lancet Haematol. 2020 Jun;7(6):e425. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30151-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y., Xiao M., Zhang S., Xia P., Cao W., Jiang W., et al. Coagulopathy and Antiphospholipid Antibodies in patients with covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 Apr 23;382(17):e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang N., Bai H., Chen X., Gong J., Li D., Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost JTH. 2020 May;18(5):1094–1099. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang N., Li D., Wang X., Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost JTH. 2020 Apr;18(4):844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox S.E., Akmatbekov A., Harbert J.L., Li G., Quincy Brown J., Vander Heide R.S. Pulmonary and cardiac pathology in African American patients with COVID-19: an autopsy series from New Orleans. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 Jul;8(7):681–686. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30243-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGonagle D., O’Donnell J.S., Sharif K., Emery P., Bridgewood C. Immune mechanisms of pulmonary intravascular coagulopathy in COVID-19 pneumonia. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020 Jul;2(7):e437–e445. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30121-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leisman D.E., Deutschman C.S., Legrand M. Facing COVID-19 in the ICU: vascular dysfunction, thrombosis, and dysregulated inflammation. Intensive Care Med. 2020 Jun;46(6):1105–1108. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06059-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cattaneo M., Bertinato E.M., Birocchi S., Brizio C., Malavolta D., Manzoni M., et al. Pulmonary embolism or pulmonary thrombosis in COVID-19? Is the recommendation to use high-dose heparin for thromboprophylaxis justified? Thromb. Haemostasis. 2020 Aug;120(8):1230–1232. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1712097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J.H.A., van der Meer N.J.M., Arbous M.S., Gommers D.A.M.P.J., Kant K.M., et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb. Res. 2020 Jul;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J.H.A., Meer NJM van der, Arbous M.S., Gommers D., Kant K.M., et al. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19: an updated analysis. Thromb. Res. 2020 Jul;191:148. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wan X., Wang W., Liu J., Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014 Dec 19;14(1):135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo D., Wan X., Liu J., Tong T. Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2018 Jun 1;27(6):1785–1805. doi: 10.1177/0962280216669183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin J. vol. 7. 2017. (© Joanna Briggs Institute 2017 Critical Appraisal Checklist for Prevalence Studies). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pizzolo F., Rigoni A.M., De Marchi S., Friso S., Tinazzi E., Sartori G., et al. Deep vein thrombosis in SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia-affected patients within standard care units: Exploring a submerged portion of the iceberg. Thromb. Res. 2020 Oct;194:216–219. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torres-Machorro A., Anguiano-Álvarez V.M., Grimaldo-Gómez F.A., Rodríguez-Zanella H., Cortina de la Rosa E., Mora-Canela S., et al. Asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis in critically ill COVID-19 patients despite therapeutic levels of anti-Xa activity. Thromb. Res. 2020 Dec;196:268–271. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santoliquido A., Porfidia A., Nesci A., De Matteis G., Marrone G., Porceddu E., et al. Incidence of deep vein thrombosis among non-ICU patients hospitalized for COVID-19 despite pharmacological thromboprophylaxis. J Thromb Haemost JTH. 2020 Sep;18(9):2358–2363. doi: 10.1111/jth.14992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ierardi A.M., Coppola A., Fusco S., Stellato E., Aliberti S., Andrisani M.C., et al. Early detection of deep vein thrombosis in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: who to screen and who not to with Doppler ultrasound? J Ultrasound. 2020 Aug 18:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s40477-020-00515-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mouhat B., Besutti M., Bouiller K., Grillet F., Monnin C., Ecarnot F., et al. Elevated D-dimers and lack of anticoagulation predict PE in severe COVID-19 patients. Eur. Respir. J. 2020 Oct;56(4) doi: 10.1183/13993003.01811-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pellens B., Romont M., Tornout M.V., Mey N.D., Dubois J., Pauw I.D., et al. Prevalence of deep venous thrombosis in ventilated COVID-19 patients: a mono-center cross-sectional study. J Emerg Crit Care Med. 2020 Oct 30;4:31. doi: 10.21037/jeccm-20-62. http://jeccm.amegroups.com/article/view/6122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ren Bin, Yan Feifei, Deng Zhouming, Zhang Sheng, Xiao Lingfei, Wu Meng, et al. Extremely high incidence of lower extremity deep venous thrombosis in 48 patients with severe COVID-19 in wuhan. Circulation. 2020 Jul 14;142(2):181–183. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fang C., Garzillo G., Batohi B., Teo J.T.H., Berovic M., Sidhu P.S., et al. Extent of pulmonary thromboembolic disease in patients with COVID-19 on CT: relationship with pulmonary parenchymal disease. Clin. Radiol. 2020 Oct;75(10):780–788. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fauvel C., Weizman O., Trimaille A., Mika D., Pommier T., Pace N., et al. Pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients: a French multicentre cohort study. Eur. Heart J. 2020 Jul 1;41(32):3058–3068. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Contou D., Pajot O., Cally R., Logre E., Fraissé M., Mentec H., et al. 2020 Aug 27. Pulmonary Embolism or Thrombosis in ARDS COVID-19 Patients: A French Monocenter Retrospective Study.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7451560/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kampouri E., Filippidis P., Viala B., Méan M., Pantet O., Desgranges F., et al. Predicting venous thromboembolic events in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 requiring hospitalization: an observational retrospective study by the COVIDIC initiative in a Swiss university hospital. BioMed Research International. Hindawi. 2020;2020:11. doi: 10.1155/2020/9126148. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2020/9126148/ Article ID 9126148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bompard F., Monnier H., Saab I., Tordjman M., Abdoul H., Fournier L., et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with Covid-19 pneumonia. Eur. Respir. J. 2020 Jan 1;56(1):2001365. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01365-2020. https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/early/2020/05/07/13993003.01365-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avruscio G., Camporese G., Campello E., Bernardi E., Persona P., Passarella C., et al. COVID-19 and venous thromboembolism in intensive care or medical ward. Clin Transl Sci. 2020 Oct 23;13:1108–1114. doi: 10.1111/cts.12907. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7567296/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibson C.J., Alqunaibit D., Smith K.E., Bronstein M., Eachempati S.R., Kelly A.G., et al. Probative value of the d-dimer assay for diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis in the coronavirus disease 2019 Syndrome. Crit. Care Med. 2020 Dec;48(12):e1322. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koleilat I., Galen B., Choinski K., Hatch A.N., Jones D.B., Billett H., et al. Clinical characteristics of acute lower extremity deep venous thrombosis diagnosed by duplex in patients hospitalized for coronavirus disease 2019. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021 Jan;9(1):36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2020.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang H., Rockman C.B., Jacobowitz G.R., Speranza G., Johnson W.S., Horowitz J.M., et al. Deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020 Oct 8;S2213-333X(20):30543–30546. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2020.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grillet F., Behr J., Calame P., Aubry S., Delabrousse E. Acute pulmonary embolism associated with COVID-19 pneumonia detected with pulmonary CT angiography. Radiology. 2020 Sep;296(3):E186–E188. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen J., Wang X., Zhang S., Lin B., Wu X., Wang Y., et al. Characteristics of acute pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19 associated pneumonia from the city of wuhan. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2020 Jul 29;26:1–8. doi: 10.1177/1076029620936772. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7391435/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hippensteel J.A., Burnham E.L., Jolley S.E. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Br. J. Haematol. 2020;190(3):e134–e137. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi J.J., Wehmeyer G.T., Li H.A., Alshak M.N., Nahid M., Rajan M., et al. D-dimer cut-off points and risk of venous thromboembolism in adult hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Thromb. Res. 2020 Dec;196:318–321. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Capaccione K.M., Li G., Salvatore M.M. Pulmonary embolism rate in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Blood Res. 2020 Nov 3;55(4) doi: 10.5045/br.2020.2020168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larsen K., Coolen-Allou N., Masse L., Angelino A., Allyn J., Bruneau L., et al. Detection of pulmonary embolism in returning Travelers with hypoxemic pneumonia due to COVID-19 in reunion island. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020 Aug;103(2):844–846. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Desborough M.J.R., Doyle A.J., Griffiths A., Retter A., Breen K.A., Hunt B.J. Image-proven thromboembolism in patients with severe COVID-19 in a tertiary critical care unit in the United Kingdom. Thromb. Res. 2020 Sep;193:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ooi M.W.X., Rajai A., Patel R., Gerova N., Godhamgaonkar V., Liong S.Y. Pulmonary thromboembolic disease in COVID-19 patients on CT pulmonary angiography - prevalence, pattern of disease and relationship to D-dimer. Eur. J. Radiol. 2020 Nov;132 doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.109336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maatman T.K., Jalali F., Feizpour C., Douglas A., McGuire S.P., Kinnaman G., et al. Routine venous thromboembolism prophylaxis may Be inadequate in the hypercoagulable state of severe coronavirus disease 2019. Crit. Care Med. 2020;48(9):p e783–e790. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004466. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7302085/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Artifoni M., Danic G., Gautier G., Gicquel P., Boutoille D., Raffi F., et al. Systematic assessment of venous thromboembolism in COVID-19 patients receiving thromboprophylaxis: incidence and role of D-dimer as predictive factors. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 2020 Jul;50(1):211–216. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02146-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benito N., Filella D., Mateo J., Fortuna A.M., Gutierrez-Alliende J.E., Hernandez N., et al. Pulmonary thrombosis or embolism in a large cohort of hospitalized patients with covid-19. Front. Med. 2020;7:557. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00557. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2020.00557/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poyiadji N., Cormier P., Patel P.Y., Hadied M.O., Bhargava P., Khanna K., et al. Acute pulmonary embolism and COVID-19. Radiology. 2020 May 14;297(3):E335–E338. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodriguez-Morales A.J., Cardona-Ospina J.A., Gutiérrez-Ocampo E., Villamizar-Peña R., Holguin-Rivera Y., Escalera-Antezana J.P., et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trav. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020 Mar 1;34 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rali P, O’Corragain O, Oresanya L, Yu D, Sheriff O, Weiss R, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in coronavirus disease 2019: an experience from a single large academic center. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord [Internet]. 2020 Oct 5 , S2213-333X (20). 30524-2 [cited 2020 Dec 19]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7535542/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Ameri P., Inciardi R.M., Di Pasquale M., Agostoni P., Bellasi A., Camporotondo R., et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19: characteristics and outcomes in the Cardio-COVID Italy multicenter study. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2020 Nov 3;3:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00392-020-01766-y. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00392-020-01766-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dujardin R.W.G., Hilderink B.N., Haksteen W.E., Middeldorp S., Vlaar A.P.J., Thachil J., et al. Biomarkers for the prediction of venous thromboembolism in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Thromb. Res. 2020 Dec;196:308–312. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Middeldorp S., Coppens M., Haaps T.F., Foppen M., Vlaar A.P., Müller M.C.A., et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J. Thromb. Haemostasis. 2020 Aug;18(8):1995–2002. doi: 10.1111/jth.14888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen S., Zhang D., Zheng T., Yu Y., Jiang J. DVT incidence and risk factors in critically ill patients with COVID-19. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 2020 Jun 30;51(1):33–39. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02181-w. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11239-020-02181-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cui S., Chen S., Li X., Liu S., Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost JTH. 2020 Jun;18(6):1421–1424. doi: 10.1111/jth.14830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soumagne T., Lascarrou J.-B., Hraiech S., Horlait G., Higny J., d’Hondt A., et al. Factors associated with pulmonary embolism among coronavirus disease 2019 acute respiratory distress Syndrome: a multicenter study among 375 patients. Crit Care Explor. 2020 Jul;2(7) doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meiler S., Hamer O.W., Schaible J., Zeman F., Zorger N., Kleine H., et al. Computed tomography characterization and outcome evaluation of COVID-19 pneumonia complicated by venous thromboembolism. Veldhuizen RAW. PloS One. 2020 Nov 19;15(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Le Jeune S., Suhl J., Benainous R., Minvielle F., Purser C., Foudi F., et al. High prevalence of early asymptomatic venous thromboembolism in anticoagulated COVID-19 patients hospitalized in general wards. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 2020 Aug 18:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02246-w. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11239-020-02246-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taccone F.S., Gevenois P.A., Peluso L., Pletchette Z., Lheureux O., Brasseur A., et al. Higher intensity thromboprophylaxis Regimens and pulmonary embolism in critically ill coronavirus disease 2019 patients. Crit. Care Med. 2020 Nov;48(11):e1087–e1090. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trimaille A., Curtiaud A., Marchandot B., Matsushita K., Sato C., Leonard-Lorant I., et al. Venous thromboembolism in non-critically ill patients with COVID-19 infection. Thromb. Res. 2020 Sep;193:166–169. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ventura-Díaz S., Quintana-Pérez J.V., Gil-Boronat A., Herrero-Huertas M., Gorospe-Sarasúa L., Montilla J., et al. A higher D-dimer threshold for predicting pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19: a retrospective study. Emerg. Radiol. 2020 Dec;27(6):679–689. doi: 10.1007/s10140-020-01859-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Longhitano Y., Racca F., Zanza C., Muncinelli M., Guagliano A., Peretti E., et al. Venous thrombo-embolism in hospitalized SARS-CoV-2 patients treated with three different anticoagulation protocols: prospective observational study. Biology. 2020 Sep 24;9(10) doi: 10.3390/biology9100310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu Y., Tu J., Lei B., Shu H., Zou X., Li R., et al. Incidence and risk factors of deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2020 Aug 28;26 doi: 10.1177/1076029620953217. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7457409/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zermatten M.G., Pantet O., Gomez F., Schneider A., Méan M., Mazzolai L., et al. Utility of D-dimers and intermediate-dose prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Thromb. Res. 2020 Dec;196:222–226. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Terpos E., Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I., Elalamy I., Kastritis E., Sergentanis T.N., Politou M., et al. Hematological findings and complications of COVID-19. Am. J. Hematol. 2020 Jul;95(7):834–847. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grimes Z., Bryce C., Sordillo E.M., Gordon R.E., Reidy J., Paniz Mondolfi A.E., et al. Fatal pulmonary thromboembolism in SARS-CoV-2-infection. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2020;48 doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2020.107227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thachil J., Tang N., Gando S., Falanga A., Cattaneo M., Levi M., et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost JTH. 2020 May;18(5):1023–1026. doi: 10.1111/jth.14810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Esmon C.T. Basic mechanisms and pathogenesis of venous thrombosis. Blood Rev. 2009 Sep;23(5):225–229. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020 Apr 16;181(2):271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Astuti I., Ysrafil Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): an overview of viral structure and host response. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(4):407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shi-Fang Yan, Nigel Mackman, Walter Kisiel, Stern David M., Pinsky David J. Hypoxia/hypoxemia-induced activation of the procoagulant pathways and the pathogenesis of ischemia-associated thrombosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1999 Sep 1;19(9):2029–2035. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.9.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Levi M., van der Poll T. Inflammation and coagulation. Crit. Care Med. 2010 Feb;38(2):S26–S34. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c98d21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pal R., Bhansali A. COVID-19, diabetes mellitus and ACE2: the conundrum. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020 Apr;162 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rizzo P, Vieceli Dalla Sega F, Fortini F, Marracino L, Rapezzi C, Ferrari R. COVID-19 in the heart and the lungs: could we “Notch” the inflammatory storm? Basic Res. Cardiol. 115(3): 31 [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Dec 19]; . Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7144545/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Wang X., Khaidakov M., Ding Z., Mitra S., Lu J., Liu S., et al. Cross-talk between inflammation and angiotensin II: studies based on direct transfection of cardiomyocytes with AT1R and AT2R cDNA. Exp Biol Med Maywood NJ. 2012 Dec;237(12):1394–1401. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2012.012212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Varga Z., Flammer A.J., Steiger P., Haberecker M., Andermatt R., Zinkernagel A.S., et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet Lond Engl. 2020 May 2;395(10234):1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ackermann M., Verleden S.E., Kuehnel M., Haverich A., Welte T., Laenger F., et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 Jul 9;383(2):120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Konstantinides S.V., Torbicki A., Agnelli G., Danchin N., Fitzmaurice D., Galiè N., et al. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the task force for the Diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European society of cardiology (ESC)endorsed by the European respiratory society (ERS) Eur. Heart J. 2014 Nov 14;35(43):3033–3080. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang T., Chen R., Liu C., Liang W., Guan W., Tang R., et al. Attention should be paid to venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the management of COVID-19. Lancet Haematol. 2020 May;7(5):e362–e363. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30109-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Demelo-Rodríguez P., Cervilla-Muñoz E., Ordieres-Ortega L., Parra-Virto A., Toledano-Macías M., Toledo-Samaniego N., et al. Incidence of asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and elevated D-dimer levels. Thromb. Res. 2020 Aug;192:23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Roach R.E.J., Cannegieter S.C., Lijfering W.M. Differential risks in men and women for first and recurrent venous thrombosis: the role of genes and environment. J Thromb Haemost JTH. 2014 Oct;12(10):1593–1600. doi: 10.1111/jth.12678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020 Mar 28;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ho F.K., Petermann-Rocha F., Gray S.R., Jani B.D., Katikireddi S.V., Niedzwiedz C.L., et al. Is older age associated with COVID-19 mortality in the absence of other risk factors? General population cohort study of 470,034 participants. PloS One. 2020 Nov 5;15(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zheng Z., Peng F., Xu B., Zhao J., Liu H., Peng J., et al. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2020 Aug 1;81(2):e16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Silverstein M.D., Heit J.A., Mohr D.N., Petterson T.M., O’Fallon W.M., Melton L.J. Trends in the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a 25-year population-based study. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998 Mar 23;158(6):585–593. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tian W., Jiang W., Yao J., Nicholson C.J., Li R.H., Sigurslid H.H., et al. Predictors of mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(10):1875–1883. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Francesco Violi, Giancarlo Ceccarelli, Roberto Cangemi, Francesco Alessandri, Gabriella D’Ettorre, Oliva Alessandra, et al. Hypoalbuminemia, coagulopathy, and vascular disease in COVID-19. Circ. Res. 2020 Jul 17;127(3):400–401. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Aloisio E., Serafini L., Chibireva M., Dolci A., Panteghini M. Hypoalbuminemia and elevated D-dimer in COVID-19 patients: a call for result harmonization. Clin Chem Lab Med CCLM. 2020 Oct 25;58(11):e255–e256. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dofferhoff A.S.M., Piscaer I., Schurgers L.J., Visser M.P.J., van den Ouweland J.M.W., de Jong P.A., et al. Reduced vitamin K status as a potentially modifiable risk factor of severe coronavirus disease 2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 Aug 27:ciaa1258. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zuo Y., Yalavarthi S., Shi H., Gockman K., Zuo M., Madison J.A., et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID-19. JCI Insight. 2020 Jun 4;5(11) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.138999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Skendros P., Mitsios A., Chrysanthopoulou A., Mastellos D.C., Metallidis S., Rafailidis P., et al. Complement and tissue factor–enriched neutrophil extracellular traps are key drivers in COVID-19 immunothrombosis. J. Clin. Invest. 2020 Nov 2;130(11):6151–6157. doi: 10.1172/JCI141374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McFadyen James D., Stevens Hannah, Peter Karlheinz. The emerging threat of (Micro)Thrombosis in COVID-19 and its therapeutic implications. Circ. Res. 2020 Jul 31;127(4):571–587. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.AlGhatrif M., Cingolani O., Lakatta E.G. The dilemma of coronavirus disease 2019, aging, and cardiovascular disease: insights from cardiovascular aging science. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Jul 1;5(7):747. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Panigada M., Bottino N., Tagliabue P., Grasselli G., Novembrino C., Chantarangkul V., et al. Hypercoagulability of COVID-19 patients in intensive care unit: a report of thromboelastography findings and other parameters of hemostasis. J Thromb Haemost JTH. 2020 Jul;18(7):1738–1742. doi: 10.1111/jth.14850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Buja L.M., Wolf D.A., Zhao B., Akkanti B., McDonald M., Lelenwa L., et al. The emerging spectrum of cardiopulmonary pathology of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): report of 3 autopsies from Houston, Texas, and review of autopsy findings from other United States cities. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2020;48 doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2020.107233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Belen-Apak F.B., Sarıalioğlu F. Pulmonary intravascular coagulation in COVID-19: possible pathogenesis and recommendations on anticoagulant/thrombolytic therapy. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 2020 May 5:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02129-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Thachil J., Cushman M., Srivastava A. A proposal for staging COVID-19 coagulopathy. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4(5):731–736. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pesavento R., Ceccato D., Pasquetto G., Monticelli J., Leone L., Frigo A., et al. The hazard of (sub)therapeutic doses of anticoagulants in non-critically ill patients with Covid-19: the Padua province experience. J. Thromb. Haemostasis. 2020;18(10):2629–2635. doi: 10.1111/jth.15022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Piazza G., Morrow D.A. Diagnosis, management, and pathophysiology of arterial and venous thrombosis in COVID-19. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020 Nov 23;324(24):2548–2549. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.23422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.10.4.3.1 Recommendations on testing for funnel plot asymmetry. https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/chapter_10/10_4_3_1_recommendations_on_testing_for_funnel_plot_asymmetry.htm

- 96.Henrina J., Lim M.A., Pranata R. COVID-19 and misinformation: how an infodemic fuelled the prominence of vitamin D. Br. J. Nutr. 2021;125:359–360. doi: 10.1017/S0007114520002950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.