Abstract

Fibrinogen-related lectins are carbohydrate-binding proteins of the innate immune system that recognize glycan structures on microbial surfaces. These innate immune lectins are crucial for invertebrates as they do not rely on adaptive immunity for pathogen clearance. Here, we characterize a recombinant fibrinogen-related lectin PmFREP from the black tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon expressed in the Trichoplusia ni insect cell. Electron microscopy and cross-linking experiments revealed that PmFREP is a disulfide-linked dimer of pentamers distinct from other fibrinogen-related lectins. The full-length protein binds N-acetyl sugars in a Ca2+ ion-independent manner. PmFREP recognized and agglutinated Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Weak binding was detected with other bacteria, including Vibrio parahaemolyticus, but no agglutination activity was observed. The biologically active PmFREP will not only be a crucial tool to elucidate the innate immune signaling in P. monodon and other economically important species, but will also aid in detection and prevention of shrimp bacterial infectious diseases.

Subject terms: Innate immunity, Glycobiology, Proteins, Structural biology

Introduction

The black tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon is an important economic animal of many countries, including Thailand1. However, there are many infectious diseases devastating shrimp farming. Viral pathogen such as white spot syndrome virus2, yellow head virus3, or shrimp baculovirus4 have costed severe economic loss and their molecular properties have been extensively investigated. There are various test kits available and factors in controlling infections are known5. Recently, bacterial pathogen such as Vibrio parahaemolyticus, causing the acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND), has emerged as a major disruption in the shrimp farming industry6. Very little is known about the interplay of the shrimp innate immune system and pathogenic bacteria. One key player is likely the lectins of the innate immune system7,8.

Lectins, or carbohydrate binding proteins, play important roles in pathogen recognition, especially in invertebrates where adaptive immunity is not as developed compared to vertebrates9. Lectins of the innate immune system generally can distinguish self from non-self by recognition of carbohydrate residues or specific glycan structure not present on the host cells. There are several families of animal lectins that are involved in the innate immunity, such as C-type lectins10, ficolins11, and intelectins12,13 (X-type lectin). Ficolins and intelectins are classified as fibrinogen-like lectins based on structural homology. In mammalian systems, ficolins are known to activate the lectin complement system for pathogen clearance7. Ficolins may act as an opsonin for phagocytosis as well14,15. However, the sequence of signaling events after bacteria recognition by lectins in invertebrate is largely unknown. Thus, we are interested in investigating the structure and function of fibrinogen-related lectin in shrimp, as it may have applications in bacterial disease prevention and treatment.

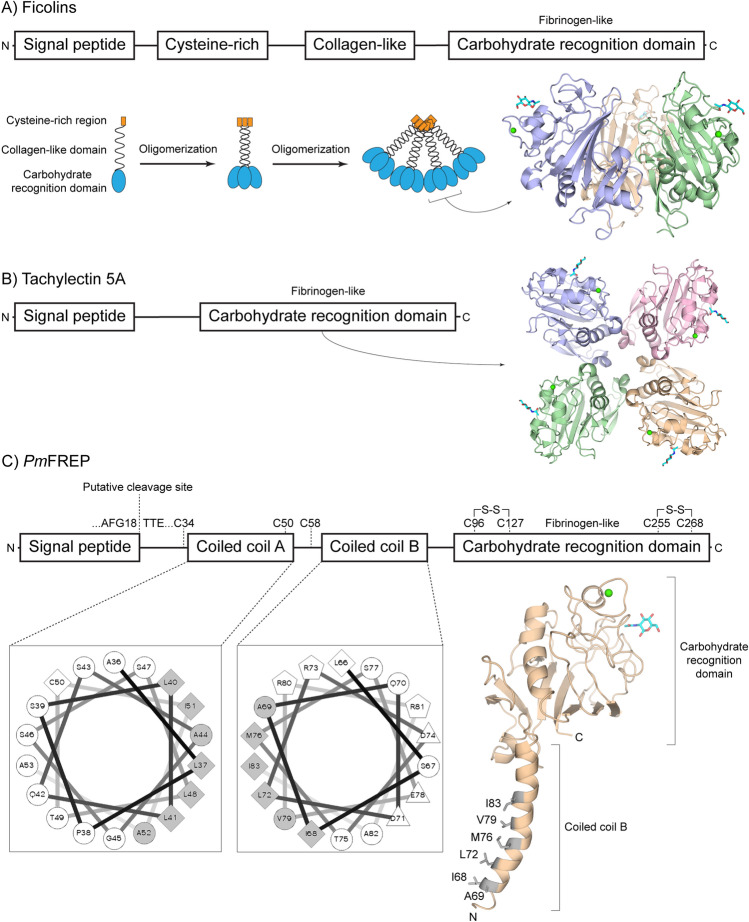

Fibrinogen-related lectins are widely distributed in the animal kingdom and they have diverse molecular structure (Fig. 1). Ficolins, found in both vertebrates and invertebrates, contain a cysteine-rich N-terminal region, a collagen-like region, and the carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) at the C terminus (Fig. 1A). Because of the collagen-like region that is capable of forming a triple helix, ficolins can trimerize. The cysteine-rich region then mediates disulfide-linked oligomerization of the trimer into higher order oligomers, resulting in a fan- or flower bouquet-shaped molecular complex16,17. Ficolins binds N-acetyl glucosamine (GlcNAc)-containing glycan and subsequent activate the innate immune system, such as the lectin complement pathway in mammals18,19. However, the signaling event in invertebrate is not well-studied. Another group of invertebrate fibrinogen-like lectin is tachylectin 5A (Fig. 1B). The protein has a simple primary structure of only the CRD. The protein is tetrameric and binds GlcNAc20,21. The protein is proposed to be involved in bacteria sensing and hemolymph clotting to seal the bacteria-exposed wound, but the molecular mechanism following ligand recognition remains unknown22. Recently, a unique fibrinogen-like lectin from P. monodon was described. The protein has been cloned by various investigators, and named PmFREP23 or PL5-124. PmFREP binds bacterial peptidoglycan23, thus likely to bind GlcNAc as observed with ficolins and tachylectin 5A. PmFREP contains three cysteines outside of the CRD (Fig. 1C). Because of the odd number of cysteines, they are likely to participate in intermolecular disulfide bond formation. In contrast to ficolins, PmFREP does not contain the collagen-like sequence, but contains two coiled coil regions that likely for amphipathic helices and mediate higher order oligomerization. Thus, we predict that PmFREP has a novel molecular assembly unique among fibrinogen-like lectins.

Figure 1.

Comparison of fibrinogen-like lectin structures. (A) Ficolins. Each polypeptide chain can trimerize and oligomerize into a flower bouquet-like structure. The structure represents a trimeric CRD. (B) Tachylectin 5A. The structure represents the tetrameric CRD. and (C) PmFREP. The coiled coil regions are also represented with helical wheel diagrams showing the predicted amphipathic helices. The structure shown is a homology model of the CRD and coiled coil B built with human fibrinogen (PDB ID 2HPC) as the template.

PmFREP and related proteins have been purified from P. monodon hemolymph23,24. Because of the potential contamination of other GlcNAc-binding fibrinogen-related lectins, it is difficult to study the structure and function of PmFREP using the protein purified from the hemolymph. In addition, the complex architecture of PmFREP may cause difficulties in recombinant protein expression. To date investigators that have cloned and studied PmFREP have reported recombinant expression of PmFREP-related proteins, such as PL5-2, in Escherichia coli, but not PmFREP (PL5-1) itself24. Given the potential intermolecular disulfide bonds and higher-order oligomerization, it is unlikely that E. coli and in vitro refolding of inclusion bodies can produce functional PmFREP, or any PmFREP-related proteins. The problem of protein quality is a bottleneck in investigating lectin structure, function, and signaling in P. monodon. Therefore, we aim to produce functional recombinant PmFREP to investigate its structure and function.

In this study, we produced recombinant PmFREP for biochemical and structural characterization. Due to the complex architectures of fibrinogen-related lectins, high level of protein expression was successful in insect cells. The dimer of pentamer structure of PmFREP was revealed by both biochemical methods and electron microscopy. Binding to N-acetyl sugars and bacteria agglutination were also demonstrated. These results will not only be crucial for further investigation of immune signaling in shrimp, but will also help in combating bacterial infectious diseases in shrimp.

Results

PmFREP was cloned into various expression vectors for expression in bacteria (Escherichia coli), mammalian cells (HEK293T), and insect cells (Trichoplusia ni). In the E. coli system, no signal peptide was included in the coding sequences and both the N- and C-terminal hexahistidine (His6) tag was explored. Despite exploration of host strains and IPTG concentrations, no protein expression was detected both by SDS-PAGE and western blot against the His6 tag (data not shown). Thus, protein expression and secretion were further explored in mammalian and insect cells (Figure S1). Protein expression was barely observable for PmFREP with its native signal peptide and a C-terminal His6 tag (Native SP PmFREP His6) when expressed and secreted from insect cells. Another expression construct examined is PmFREP with the Xenopus laevis embryonic epidermal lectin signal peptide and an N-terminal His6 tag (XEEL SP His6 PmFREP, Figure S2A). This expression construct yielded higher amount of protein in the insect system compared to the mammalian system. Truncation of PmFREP to only the CRD with the XEEL signal peptide and a N-terminal His6 tag (XEEL SP His6 PmFREP, Figure S2B) when expressed in insect cells yielded high amount of protein in insect culture media, visible in SDS-PAGE with Coomassie Blue stain. Therefore, the insect expression system was used to express the constructs XEEL SP His6 PmFREP and XEEL SP His6 PmFREP CRD, yielding His6 PmFREP and His6 PmFREP CRD respectively. The protein was purified by Ni–NTA affinity chromatography for subsequent experiments (Figure S3). Correct cleavage of the signal peptide for both His6 PmFREP and His6 PmFREP CRD was verified with N-terminal protein sequencing (Figure S4).

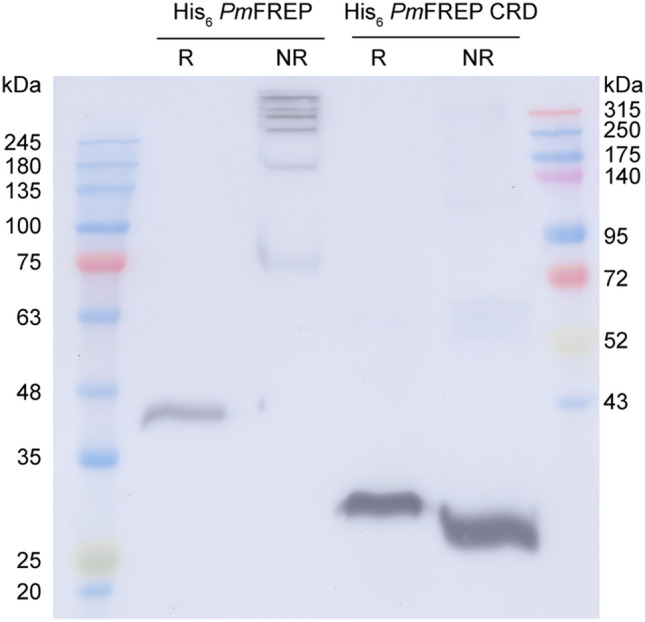

With the ability to produce recombinant PmFREP, we next explored the disulfide linked oligomeric states of PmFREP by examining the apparent molecular weight under reducing (with DTT in sample buffer) and non-reducing conditions (no DTT in sample buffer) (Fig. 2). His6 PmFREP ran as a single species under reducing conditions, but appear to assemble into large disulfide-linked oligomers of more than 315 kDa. On the other hand, His6 PmFREP CRD appeared monomeric both in reducing and non-reducing conditions, indicating that there are no intermolecular disulfide bonds in the CRD.

Figure 2.

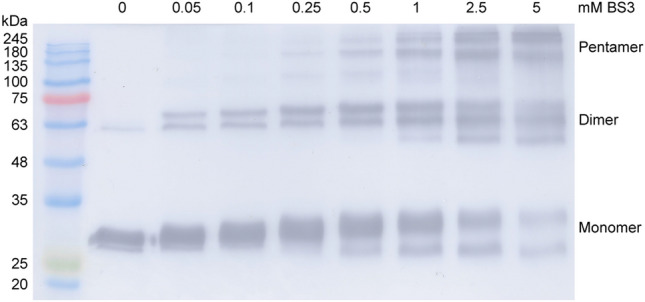

Western blot of His6 PmFREP and His6 PmFREP CRD under reducing (R) and non-reducing (NR) conditions. Anti-His6 antibody was used as the primary antibody.

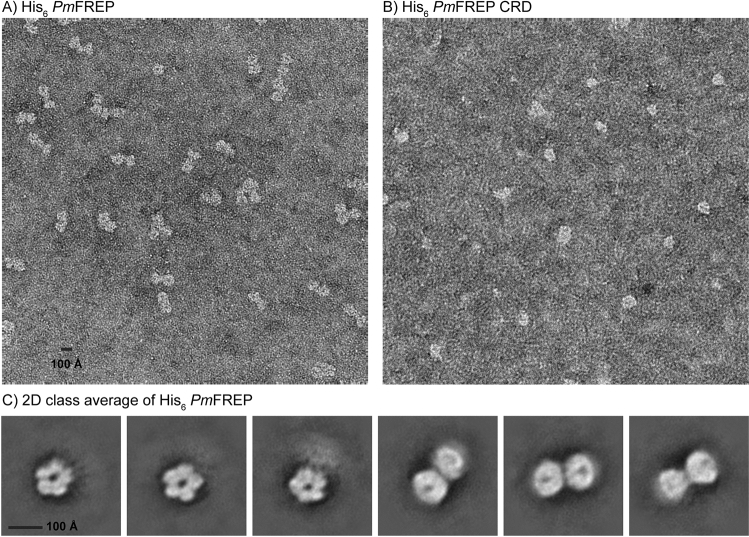

To further examine the quaternary structure of PmFREP, both His6 PmFREP and His6 PmFREP CRD were examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with negative staining (Fig. 3). His6 PmFREP appeared as dumbbell-shaped molecules with the dimension of roughly 100 × 200 Å. Two-dimensional class averaging suggested that the molecule is a dimer of pentamer with a flexible linker in between. This oligomeric structure is distinct from other fibrinogen-related lectins, such as mammalian ficolins, which are flower bouquet-shaped consisting of oligomers of trimers, or intelectins which are also trimer or oligomer of trimers. His6 PmFREP CRD appeared as 100 Å particles, but we were not able to obtain consistent 2D class average. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) experiments also confirmed the sizes of His6 PmFREP (215 ± 36 Å) and His6 PmFREP CRD (97 ± 30 Å) (Figure S5). These results suggested that His6 PmFREP CRD might still be able to oligomerize in solution, but the oligomeric conformation may not be as stable as the full length His6 PmFREP protein. To examine whether His6 PmFREP CRD can oligomerize in solution, chemical cross-linking was performed (Fig. 4). As the concentration of the cross-linker was increased, species with the molecular weight consistent with dimers and pentamers were observed. These results suggested that His6 PmFREP CRD can self-associate in solution and were consistent with the TEM and DLS results.

Figure 3.

TEM micrograph of (A) His6 PmFREP, (B) His6 PmFREP CRD, and (C) 2D class averages of His6 PmFREP.

Figure 4.

Crosslinking of PmFREP CRD with bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate (BS3) at various concentrations. PmFREP was detected by western blot probed with an anti-His6 antibody.

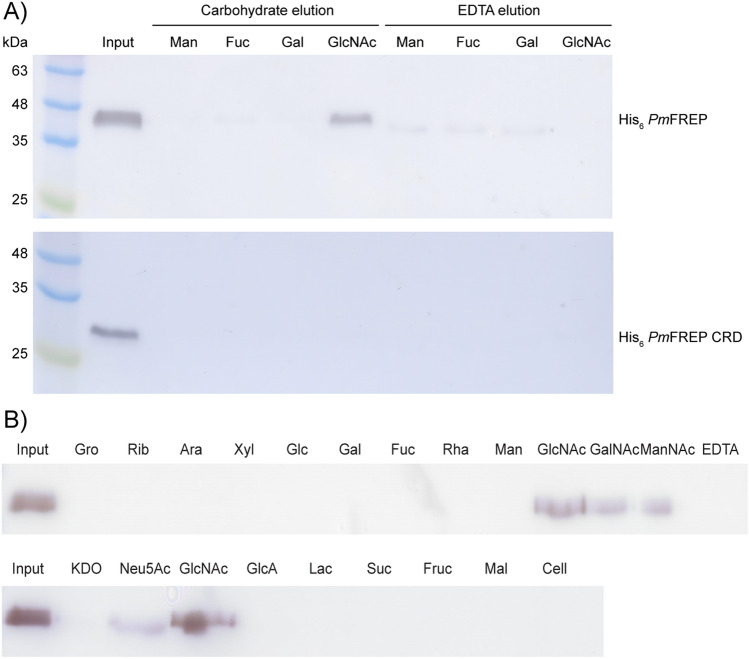

To explore the ligand binding properties of PmFREP, we performed competitive elution assays (Fig. 5A). The proteins were bound to carbohydrate affinity resins and eluted with the corresponding monosaccharide or EDTA. His6 PmFREP can bind GlcNAc as expected for fibrinogen-like lectin. However, EDTA was not able to eluted His6 PmFREP from the GlcNAc resin. In contrast to the full length His6 PmFREP, His6 PmFREP CRD failed to bind any carbohydrate affinity resin. To further explore carbohydrate specificity of His6 PmFREP, His6 PmFREP was bound to the GlcNAc resin and eluted with various carbohydrates (Fig. 5B). GlcNAc, N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc), N-acetylmannosamine (ManNAc), and N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) were able to elute His6 PmFREP from the GlcNAc resin. However, competitive elution was not observed with glycerol (Gro), ribose (Rib), arabinose (Ara), xylose (Xyl), glucose (Glc), galactose (Gal), fucose (Fuc), rhamnose (Rha), mannose (Man), 3-deoxy-D-manno-2-octulosonic acid (KDO), glucoronic acid (GlcA), lactose (Lac), sucrose (Suc), fructose (Fruc), maltose (Mal), and cellobiose (Cell). These results suggested that His6 PmFREP was specific for acetyl group-containing carbohydrates, and while the ligand binding site and the calcium ion-binding residues were conserved (Fig. 6), the calcium ion is not required for ligand binding.

Figure 5.

(A) Western blot analysis of His6 PmFREP (top panel) and His6 PmFREP CRD (bottom panel) bound to different carbohydrate resin and eluted with either the respective monosaccharide or EDTA. (B) Competitive elution of His6 PmFREP bound to GlcNAc resin by different soluble carbohydrates. Anti-His6 antibody was used as the primary antibody.

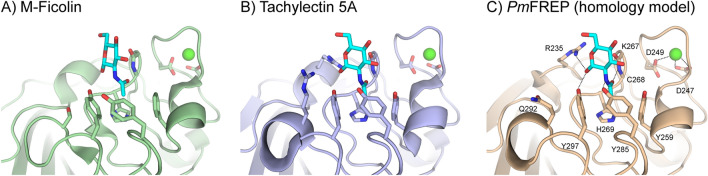

Figure 6.

Comparison of the ligand binding site of (A) M-ficolin (crystal structure, PDB ID 2JHK), (B) Tachylectin 5A (crystal structure, PDB ID 1JC9), and (C) PmFREP (homology model using SWISS-MODEL44, PDB ID 1JC9 as the template). The GlcNAc ligand is shown in cyan and the structural calcium ion is shown in green.

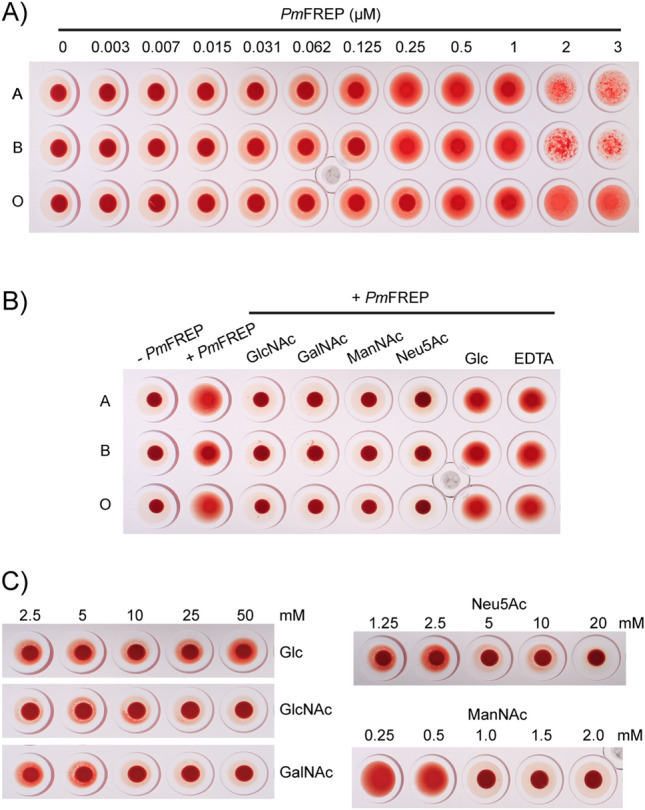

To investigate recognition of carbohydrates in cellular context, we examined agglutination of red blood cells by His6 PmFREP. Because of the dimer of pentamer arrangement, His6 PmFREP is expected to agglutinate cells displaying its ligand. His6 PmFREP agglutinates red blood cells of A-, B- and O-type starting at concentration around 0.031 µM (Fig. 7A). Agglutination was inhibited by GlcNAc, GalNAc, ManNAc, and Neu5Ac (Fig. 7B). However, glucose and EDTA could not inhibit agglutination. GlcNAc and GalNAc could inhibit agglutination at around 10 mM (Fig. 7C). Inhibition of agglutination was observed at 5 and 1 mM for Neu5Ac and ManNAc, respectively.

Figure 7.

Agglutination of human red blood cells with His6 PmFREP. (A) Agglutination of different ABO blood type by His6 PmFREP at various concentrations. (B) Inhibition of ABO blood type agglutination by different carbohydrates (20 mM for Neu5Ac and 50 mM for other carbohydrates) and EDTA. (C) Inhibition of A blood type agglutination by different carbohydrates at various concentrations.

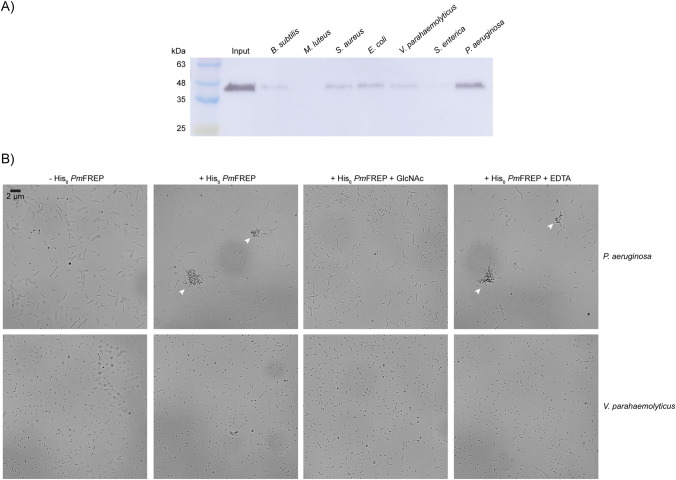

Because of its proposed role in P. monodon innate immune system, we next examined the ability of His6 PmFREP to recognize bacteria (Fig. 8A). His6 PmFREP was bound to bacteria pellet and eluted with GlcNAc. The eluted protein solutions were then examined by western blot. His6 PmFREP strongly recognized Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Noticeable binding was also observed with Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Very little to no binding was observed toward Micrococcus luteus and Salmonella enterica. Because the dimer of pentamer molecular architecture of PmFREP suggests that the protein can engage two bacteria simultaneously and cause agglutination, bacteria agglutination activity of PmFREP was explored (Fig. 8B). P. aeruginosa and V. parahaemolyticus were used in the agglutination because of the strong signal in the bacteria binding assay and the importance as a shrimp pathogen respectively. At the highest concentration of His6 PmFREP shown to agglutinate red blood cells (3 µM), His6 PmFREP agglutinated S. aureus and this activity is inhibited by addition of GlcNAc. However, sequestration of Ca2+ ion by addition of EDTA did not inhibit agglutination. In contrast, V. parahaemolyticus was not agglutinated by His6 PmFREP.

Figure 8.

(A) Western blot of His6 PmFREP eluted from bacteria pellet with 100 mM GlcNAc. Anti-His6 antibody was used as the primary antibody. (B) Agglutination of bacteria with His6 PmFREP (3 µM). Clumps of bacteria are indicated with arrows.

Discussion

Various investigators have purified PmFREP and its homologs from P. monodon hemolymph23–25. However, the degree of contamination by other homologs is unknown, which complicates further analysis of PmFREP structure and function. Moreover, in contrast to other PmFREP homologs in shrimp, there is no report of expression or characterization of functional recombinant PmFREP23–25. We speculate that other investigators have encounter issues with bacterial production of PmFREP. In our hands, we did not observe protein expression in E. coli whether the His6 tag was placed at the N- or C-terminus. Thus, we conclude that bacterial expression system might not be suitable for PmFREP. Some protein expression is detected in mammalian cells, but scaling up protein production would be cost prohibitive, especially with transient transfection. Appreciable yield was observed when PmFREP was expressed in insect cells for both His6 PmFREP and His6 PmFREP CRD. Therefore, the insect cell expression is the system of choice for PmFREP. XEEL signal peptide was used because of the observation that XEEL, a fibrinogen-related lectin of the intelectin family, is highly expressed in insect cells12. Cleavage of the signal peptide occurred at the expected site as confirmed by N-terminal protein sequencing. We reasoned that the placement of the His6 tag at the N-terminus is more suitable because the C-terminal carboxyl group of other fibrinogen-related lectins, such as H-ficolin26 or intelectins12,13, form a salt bridge with another amino acid residue. Placement of a C-terminal tag may disrupt this interaction and destabilize PmFREP. In this case of human intelectin and XEEL, placement of the C-terminal tag drastically reduced the protein expression yield12,13. Utilization of the His6 tag is ubiquitous in biochemistry. The tag is placed at a protein terminus, which is not likely involved in interaction interfaces or any functional site27. Another advantage of the His6 tag is its function as an epitope tag. Thus, raising a specific antibody to PmFREP is not required. Moreover, having a tag separated from the protein sequence allow better control over future immunoprecipitation experiments because antibody binding to the tag will be less likely to interfere with interaction of PmFREP and other binding partners.

Because most lectins are oligomeric and the N-terminus of PmFREP contains an odd number of 3 cysteines (C34, C50, and C58), we reason that PmFREP might be able to form intermolecular disulfide bonds. SDS-PAGE analysis of His6 PmFREP and His6 PmFREP CRD under reducing and non-reducing conditions revealed that His6 PmFREP is a disulfide-linked oligomer. The cysteines in the CRD are conserved among other fibrinogen-related lectins and are only involved in intramolecular disulfide bond formation21,26. This is consistent with the results that His6 PmFREP CRD is monomeric both in reducing and non-reducing conditions. Because of this intermolecular disulfide bonds, it is unlikely that recombinant PmFREP produced in E. coli, even if expressed, will be fully functional. Further examination of His6 PmFREP quaternary structure by TEM revealed dumbbell-shaped molecules. Two-dimensional class averaging suggested that His6 PmFREP is a dimer of pentamer with a flexible linker. The molecular weight of the dimer of pentamer, or decamer, would be around 345 kDa, which is consistent with the observation that His6 PmFREP ran at more than 315 kDa in SDS-PAGE under non-reducing conditions. DLS also confirmed the particle size observed in TEM. Examination of His6 PmFREP CRD by TEM revealed protein molecules about the size of the pentamer in the full length His6 PmFREP. However, 2D class averaging did not yield sensible solutions, suggesting that His6 PmFREP CRD might be able to oligomerize in solution, but the structure is rather inhomogeneous. Chemical cross-linking of His6 PmFREP CRD in solution and DLS also indicate that the pentameric assembly of His6 PmFREP CRD likely exists in solution. A similar molecular property is observed in XEEL, a fibrinogen-related lectin of the intelectin family12. XEEL is a dimer of trimer, and the CRD is capable of trimerization in solution even in the absence of the intermolecular disulfide bonds.

His6 PmFREP recognized GlcNAc, as expected from structural homology to other fibrinogen-related lectins (Fig. 5). Most residues in the binding sites that interact directly with GlcNAc (R235, NH of C268, H269, Y285, and Y297) are conserved between PmFREP and tachylectin 5A21. The residues recognizing the N-acetyl group (NH of C268, H269, Y285, and Y297) are conserved in human M-ficolin as well28. PmFREP could also bind GalNAc, ManNAc, and Neu5Ac. The red blood cell agglutination experiments suggested that PmFREP have the highest affinity towards ManNAc. However, the lack of experimental structural data, which we will continue to investigate, do not currently allow us to comments on specific interactions. It is also not clear whether ManNAc is a biologically relevant epitope since there is limited information on glycobiology of shrimp diseases. However, because PmFREP was first identified as a peptidoglycan-binding lectin23, the GlcNAc-binding activity might still be biologically relevant.

The calcium ion binding residues (D247 and D249) are conserved between PmFREP, tachylectin 5A, and M-ficolin, suggesting that PmFREP possesses Ca2+ ion binding activity. However, our results showed that Ca2+ ion was not required for GlcNAc binding. Because the Ca2+ ion is not directly participating in ligand binding, it is possible that the Ca2+ ion may only have structural and stability role for PmFREP. There are reports that other shrimp fibrinogen-related lectins require Ca2+ ion for ligand binding29–33. However, several ficolins are also capable of Ca2+-independent ligand binding19,34–36. The role of Ca2+ ion in PmFREP ligand binding modulated by protein stability need to be further investigated. In contrast to the full length His6 PmFREP, His6 PmFREP CRD did not bind the GlcNAc affinity resin. The reduction in ligand binding affinity could be due to the lack of intermolecular disulfide bonds that may stabilize the structure. This observation is consistent with the TEM results which indicates that His6 PmFREP CRD has relatively low structural homogeneity and may not be stable enough to bind GlcNAc with high affinity. In addition to potential reduction in structural stability, truncation of the full length protein to merely the CRD certainly reduced the multivalent binding capability of His6 PmFREP. Multivalent binding event is well documented and is utilized ubiquitously in nature to increase apparent binding affinity, or avidity, especially in immune proteins and signaling events37–39. Therefore, reduction in binding avidity is expected for any lectin when the oligomeric state is reduced.

His6 PmFREP clearly recognized P. aeruginosa. Binding is less strong towards B. subtilis, S. aureus, E. coli, and V. parahaemolyticus. Because His6 PmFREP is a dimer of pentamer, the molecule should be able to engage two bacteria simultaneously and cause agglutination. Indeed, His6 PmFREP agglutinated P. aeruginosa and this activity is inhibited by the presence of GlcNAc. Addition of EDTA to sequester Ca2+ ion did not inhibit agglutination. These results are consistent with the ligand binding and red blood cell agglutination experiments which suggested that Ca2+ is not required for ligand binding. In contrast to P. aeruginosa, His6 PmFREP did not agglutinate V. parahaemolyticus, which is consistent with the weaker binding affinity of His6 PmFREP towards V. parahaemolyticus in the ligand binding assay.

In conclusion, we have characterized the recombinant fibrinogen-like lectin PmFREP from P. monodon expressed in insect cells. The protein is a dimer of pentamer with intermolecular disulfide bonds at the N-terminus. This dimer of pentamer molecular architecture is novel among fibrinogen-related lectins. PmFREP binds GlcNAc like other fibrinogen-related lectins, such as tachylectin 5A and ficolins. In addition, binding to GalNAc, ManNAc, and Neu5Ac was observed. Ca2+ is not required for ligand binding, but may have structural roles as the calcium binding residues are conserved. The CRD itself is capable of oligomerization in solution, but cannot bind the GlcNAc ligand. PmFREP recognizes and agglutinates P. aeruginosa in a Ca2+-independent manner, but cannot agglutinate the shrimp pathogen V. parahaemolyticus although weak binding is observed in the bacteria binding assay. The information obtained and His6 PmFREP produced in the study will be useful for further biochemical investigation and the signaling pathway of innate immune lectins in shrimp that may help prevent and treat bacterial infectious disease in shrimp in the future.

Methods

Expression plasmids and protein expression

For expression in insect cells, the open reading frame for PmFREP (GenBank accession number AIE45535) was amplified from P. monodon hemocyte cDNA by the primers 5′-GCGCGGATCCATGGCGCTCTTGCACAAGTTCATG-3′ and 5′-ATGCGGTACCTCATTAGAATGCCGGCCTTATCATCATTGTTG-3′, and cloned into the BamHI and KpnI sites of pFastBac1 (pFastBac1 PmFREP). After sequencing, G184D substitution was noted in all the 3 clones sequenced and was thus assumed to be a natural variation. The plasmid for expression of PmFREP His6 was made similarly, but with 5′-ATGCGGTACCTCATTAATGGTGATGGTGGTGATGGAATGCCGGCCTTATCATCATTGTTG-3′ as the reverse primer (pFastBac1 PmFREP His6). To create the expression construct for His6 PmFREP with Xenopus laevis embryonic epidermal lectin signal peptide (XEEL SP), pFastBac1 PmFREP was used as a template to amplify with the primer 5′-CCAGCAGGGCACGCTGGTTCACATCACCACCATCACCACAGCGGTACAACAGAACGAACAGATACCGCGG-3′ and the same reverse primer used to make pFastBac1 PmFREP. The PCR product was amplified again with the primers 5′-ATGCGGTACCATGTTGTCATATAGCCTGTTGCTTTTTGCACTTGCATTTCCAGCAGGGCACGCTGGTTCA-3′ and the same reverse primer. The PCR product was then cloned into the BamHI and KpnI sites of pFastBac1 (pFastBac1 XEEL SP His6 PmFREP). To create the expression construct for the carbohydrate recognition domain of PmFREP with the XEEL signal peptide (XEEL SP His6 PmFREP CRD), pFastBac1 PmFREP was used as a template to amplify with the primer 5′- CCAGCAGGGCACGCTGGTTCACATCACCACCATCACCACGGTTCACGGCCGAGGCACTGCCGCGACCTGC-3′ and the same reverse primer used to make pFastBac1 PmFREP. The PCR product was re-amplified and cloned into pFastBac1 in the same manner as pFastBac1 XEEL SP His6 PmFREP (pFastBac1 XEEL SP His6 PmFREP CRD). Insect cell transfection, baculovirus production in Sf21, and protein production in Trichoplusia ni were carried out as described previously12.

The bacterial expression vectors were constructed using pFastBac1 PmFREP His6 as a template for PCR. For the expression plasmid of PmFREP His6, the open reading frame was amplified using the primers 5′-TGGCCATGGGGACAACAGAACGAACAGATACC-3′ and 5′-TATACTCGAGGAATGCCGGCCTTATCATCATTG-3′, and then cloned into the NcoI and XhoI sites of pET28a (pET28a PmFREP His6). For the expression plasmid of His6 PmFREP, the open reading frame was amplified using the primers 5′-ATACCATGGGCCATCATCATCATCATCACGGGACAACAGAACGAACAGATACCG-3′ and 5′- CTCGGATCCTCATTAGAATGCCGGCCTTATCATC -3′, and then cloned into the NcoI and BamHI sites of pET28a (pET28a His6 PmFREP). For protein expression in Escherichia coli, the plasmids were each transformed into Tuner(DE3) and Rosetta(DE3). After growing at 37 °C until OD600 reached 0.6, protein expression was induced by 0, 0.5, and 1 mM IPTG for 6 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation and lysed by sonication. The soluble and insoluble fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blot.

The mammalian expression plasmid for His6 PmFREP with the XEEL signal peptide was constructed by PCR amplification of the XEEL SP His6 PmFREP open reading frame from pFastBac1 XEEL SP His6 PmFREP using the primers 5′-ATGCGGTACCATGTTGTCATATAGCCTGTTGCTTTTTGCACTTGCATTTCCAGCAGGGCACGCTGGTTCA-3′ and 5′-CTCGGATCCTCATTAATGGTGATGGTGGTGATGG-3′, and then cloned into the KpnI and BamHI sites of pcDNA4 myc His A (pcDNA4 myc His A XEEL SP His6 PmFREP). For protein expression in mammalian cells, HEK293T was cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/mL of penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco). Prior to transfection, cells were plated at 106 cells/well in a 6-well plate and incubated overnight. The transfection mixture contains 2 μg plasmid and 6 μg PEI (linear MW 25,000, Polysciences) in 200 μL of Opti-MEM (Gibco). After 30 min incubation, Opti-MEM was added to the total volume of 1 mL. The culture media was aspirated from the adherent cells and replaced with the transfection mixture. After 4 h, SFM4HKE293 (1.5 mL, HyClone) was added. Protein secretion was allowed to proceed for 48 h before the culture media was collected for analysis by western blot.

Purification of His6PmFREP and His6PmFREP CRD

Insect culture media containing secreted protein were dialyzed against 20 mM Bis–Tris pH 6.5 and 150 mM NaCl to reduce media component precipitation and subsequently dialyzed against 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 25 mM imidazole (loading buffer). The dialyzed insect culture media was then applied a Ni–NTA column equilibrated with the loading buffer. The column was washed with the loading buffer and the protein eluted with 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 250 mM imidazole. Buffer was exchanged to 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 10 mM CaCl2 by dialysis. The purity of the protein was examined by SDS-PAGE and the presence of the His6 tag verified by western blot. Protein concentrations were determined using spectrophotometry at 280 nm. For His6 PmFREP (34.5 kDa) the extinction coefficient is 63,745 M−1 cm−1 or 1 absorbance unit = 1.849 mg/mL. For His6 PmFREP CRD (26.6 kDa) the extinction coefficient is 63,620 M−1 cm−1 or 1 absorbance unit = 2.396 mg/mL. N-terminal sequencing of the purified proteins was performed with ABI 494 Protein Sequencer (Tufts University Core Facility, Tufts Medical School). Dynamic light scattering data were collected on Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS using microcuvettes (40 µL).

Negative stain and transmission electron microscopy

Samples were diluted in 5 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 1 mM CaCl2 to concentration of 5 µg/mL. Negative stain was carried out as previously described40. TEM data acquisition was performed on FEI Tecnai T12 electron microscope operating at 120 kV equipped with 4 k x 4 k CCD camera (Gatan Ultrascan). Images were taken at magnifications of 110,000 (0.7 Å/pixel, defocus − 0.5 μm). Images format conversion was performed with EMAN241. Image processing and 2D class averaging were performed with cisTEM42.

His6PmFREP CRD crosslinking

Bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate (BS3, Pierce) was dissolved in water and added to 90 µL solutions of His6 PmFREP CRD (80 µg/mL in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 10 mM CaCl2) to achieve the final concentrations of 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2.5, and 5 mM with the total volume of 100 µL. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min and the quenched by addition of 1 M Tris pH 7.5 to the final concentration of 20 mM. The product was then analyzed by western blot.

Carbohydrate binding assay

Affinity resins containing different carbohydrate ligands were prepared as previously described43. Purified His6 PmFREP or His6 PmFREP CRD in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 10 mM CaCl2 (binding buffer). The protein solution (20 µg/mL, 100 µL) was then applied to 100 µL of affinity resin in Bio-Rad Micro Bio-Spin column that had previously been washed with water and pre-equilibrated with the binding buffer. After centrifugation, the resin was washed with 3 × 250 µL of the binding buffer. The bound protein was then eluted with 2 × 100 µL of the elution buffer and analyzed by western blot with anti-His6 antibody as the primary antibody. For competitive elution with monosaccharide, the elution buffer is 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, and 100 mM monosaccharide. For EDTA elution, the elution buffer is 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 10 mM EDTA. The eluted samples were precipitated in cold acetone (4 volume) at − 20 °C for 2 h. The solution was centrifuged at 14,000×g at 4 °C for 30 min. The supernatant was removed and the pellet dried at room temperature. The precipitate was dissolves in SDS-PAGE sample buffer and subjected to Western blot using anti-His6 antibody.

Red blood cell agglutination assay

Human red blood cells were purchased from Thai Red Cross and washed with the binding buffer before use. His6 PmFREP was incubated with a suspension of 3% (v/v) human red blood cells (A, B, and O) in 72-well Terasaki plates. In the inhibition experiments, various sugars were incubated with 0.5 μM His6 PmFREP and 3% (v/v) human red blood cells was then added, agglutination activity was observed as diffused cells that do not settle to the bottom of the well compared to untreated cells.

Bacteria binding and agglutination assay

All bacteria were cultured in nutrient broth, except V. parahaemolyticus that was cultured in nutrient broth with 3% NaCl. Bacteria (50 mg) were pelleted and washed with 250 µL of the binding buffer. The pellets were then suspended in His6 PmFREP (20 µg/mL, 250 µL) then incubated on ice for 10 min. The pellets were washed with 3 × 250 µL of the binding buffer. The protein was then eluted from each pellet by 100 µL of 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, and 100 mM monosaccharide. The eluted protein was analyzed by western blot with anti-His6 antibody as the primary antibody.

For the agglutination assay, the bacteria were grown, washed, and resuspended in the binding buffer as mentioned above. The bacteria solution (50 µL) was mixed with His6 PmFREP (100 µg/mL or 3 µM, 10 µL). The total volume was then adjusted to 70 µL with the binding buffer with or without the addition of GlcNAc or EDTA to the final concentration of 10 or 25 mM, respectively. A 20 µL sample of each mixture was then photographed under an Olympus CX31 light microscope equipped with a Canon EOS 650D digital camera.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Thailand Research Fund and Office of the Higher Education Commission, Ministry of Education Research Grant for New Scholar number MRG6180012 (KW). This work is also partially supported by the Chulalongkorn University grant to the Center of Excellence for Molecular Biology and Genomics of Shrimp (KW and AT) and Molecular Crop Research Unit (KW). NS and KW is supported by the Second Century Fund (C2F), Chulalongkorn University. We would like to thank Prof. Alisa Vangnai for the use of microscope and camera, and DKSH (Thailand) Limited for access to a dynamic light scattering equipment.

Author contributions

K.W. and A.T. designed the study and analyzed the results. K.W. and S.L. performed protein expression. K.W. and N.S. purified the protein, examined the biochemical properties, performed ligand binding, bacteria binding, and agglutination assays. K.W. acquired light scattering data. B.N.T., K.W. and P.T.M. acquired the electron microscopy data. K.W. wrote the manuscript with input from other authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-82301-5.

References

- 1.Sampantamit T, et al. Aquaculture production and its environmental sustainability in Thailand: Challenges and potential solutions. Sustainability. 2020;12:2010. doi: 10.3390/su12052010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanchez-Paz A. White spot syndrome virus: An overview on an emergent concern. Vet. Res. 2010;41:43. doi: 10.1051/vetres/2010015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munro J, Owens L. Yellow head-like viruses affecting the penaeid aquaculture industry: A review. Aquac. Res. 2007;38:893–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2007.01735.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajendran KV, Makesh M, Karunasagar I. Monodon baculovirus of shrimp. Indian J. Virol. 2012;23:149–160. doi: 10.1007/s13337-012-0086-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaivisuthangkura P, Longyant S, Sithigorngul P. Immunological-based assays for specific detection of shrimp viruses. World J. Virol. 2014;3:1–10. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v3.i1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang KFJ, Bondad-Reantaso MG. Impacts of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease on commercial shrimp aquaculture. Revue scientifique et technique (International Office of Epizootics) 2019;38:477–490. doi: 10.20506/rst.38.2.2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujita T, Matsushita M, Endo Y. The lectin-complement pathway—its role in innate immunity and evolution. Immunol. Rev. 2004;198:185–202. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suresh R, Mosser DM. Pattern recognition receptors in innate immunity, host defense, and immunopathology. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2013;37:284–291. doi: 10.1152/advan.00058.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loker ES, Adema CM, Zhang SM, Kepler TB. Invertebrate immune systems—not homogeneous, not simple, not well understood. Immunol. Rev. 2004;198:10–24. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown GD, Willment JA, Whitehead L. C-type lectins in immunity and homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018;18:374–389. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Endo Y, Matsushita M, Fujita T. The role of ficolins in the lectin pathway of innate immunity. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2011;43:705–712. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wangkanont K, Wesener DA, Vidani JA, Kiessling LL, Forest KT. Structures of xenopus embryonic epidermal lectin reveal a conserved mechanism of microbial glycan recognition. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:5596–5610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.709212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wesener DA, et al. Recognition of microbial glycans by human intelectin-1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015;22:603–610. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bidula S, Sexton DW, Schelenz S. Serum opsonin ficolin-A enhances host-fungal interactions and modulates cytokine expression from human monocyte-derived macrophages and neutrophils following Aspergillus fumigatus challenge. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2016;205:133–142. doi: 10.1007/s00430-015-0435-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Endo Y, Matsushita M, Fujita T. New insights into the role of ficolins in the lectin pathway of innate immunity. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2015;316:49–110. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohashi T, Erickson HP. The disulfide bonding pattern in ficolin multimers. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:6534–6539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310555200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lacroix M, et al. Residue Lys57 in the collagen-like region of human L-ficolin and its counterpart Lys47 in H-ficolin play a key role in the interaction with the mannan-binding lectin-associated serine proteases and the collectin receptor calreticulin. J. Immunol. 2009;182:456–465. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsushita M, et al. A novel human serum lectin with collagen- and fibrinogen-like domains that functions as an opsonin. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:2448–2454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohashi T, Erickson HP. Two oligomeric forms of plasma ficolin have differential lectin activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:14220–14226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gokudan S, et al. Horseshoe crab acetyl group-recognizing lectins involved in innate immunity are structurally related to fibrinogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:10086–10091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kairies N, et al. The 2.0-A crystal structure of tachylectin 5A provides evidence for the common origin of the innate immunity and the blood coagulation systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:13519–13524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201523798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawabata S, Tsuda R. Molecular basis of non-self recognition by the horseshoe crab tachylectins. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1572:414–421. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Udompetcharaporn A, et al. Identification and characterization of a QM protein as a possible peptidoglycan recognition protein (PGRP) from the giant tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2014;46:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angthong P, Roytrakul S, Jarayabhand P, Jiravanichpaisal P. Characterization and function of a tachylectin 5-like immune molecule in Penaeus monodon. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2017;76:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2017.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angthong P, Roytrakul S, Jarayabhand P, Jiravanichpaisal P. Involvement of a tachylectin-like gene and its protein in pathogenesis of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) in the shrimp, Penaeus monodon. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2017;76:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garlatti V, et al. Structural insights into the innate immune recognition specificities of L- and H-ficolins. EMBO J. 2007;26:623–633. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carson M, Johnson DH, McDonald H, Brouillette C, Delucas LJ. His-tag impact on structure. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2007;63:295–301. doi: 10.1107/s0907444906052024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garlatti V, et al. Structural basis for innate immune sensing by M-ficolin and its control by a pH-dependent conformational switch. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:35814–35820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705741200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Senghoi W, Thongsoi R, Yu XQ, Runsaeng P, Utarabhand P. A unique lectin composing of fibrinogen-like domain from Fenneropenaeus merguiensis contributed in shrimp immune defense and firstly found to mediate encapsulation. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019;92:276–287. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang XW, et al. Cloning and characterization of two different ficolins from the giant freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2014;44:359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chai YM, Zhu Q, Yu SS, Zhao XF, Wang JX. A novel protein with a fibrinogen-like domain involved in the innate immune response of Marsupenaeus japonicus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2012;32:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun JJ, et al. A fibrinogen-related protein (FREP) is involved in the antibacterial immunity of Marsupenaeus japonicus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014;39:296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han K, et al. Novel fibrinogen-related protein with single FReD contributes to the innate immunity of Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018;82:350–360. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sugimoto R, et al. Cloning and characterization of the Hakata antigen, a member of the ficolin/opsonin p35 lectin family. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:20721–20727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.20721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Y, Tan SM, Lee SH, Kon OL, Lu J. Purification and binding properties of a human ficolin-like protein. J. Immunol. Methods. 1997;204:43–49. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adler Sorensen C, Rosbjerg A, Hebbelstrup Jensen B, Krogfelt KA, Garred P. The lectin complement pathway is involved in protection against enteroaggregative Escherichia coli infection. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:1153. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee RT, Lee YC. Affinity enhancement by multivalent lectin-carbohydrate interaction. Glycoconj. J. 2000;17:543–551. doi: 10.1023/a:1011070425430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sacchettini JC, Baum LG, Brewer CF. Multivalent protein–carbohydrate interactions. A new paradigm for supermolecular assembly and signal transduction. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3009–3015. doi: 10.1021/bi002544j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kiessling LL, Young T, Gruber TD, Mortell KH. In: Glycoscience: Chemistry and Chemical Biology. Fraser-Reid BO, Tatsuta K, Thiem J, editors. Berlin: Springer; 2008. pp. 2483–2523. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tran BN, et al. Higher order structures of Adalimumab, Infliximab and their complexes with TNFalpha revealed by electron microscopy. Protein Sci. 2017;26:2392–2398. doi: 10.1002/pro.3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang G, et al. EMAN2: An extensible image processing suite for electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 2007;157:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grant T, Rohou A, Grigorieff N. cisTEM, user-friendly software for single-particle image processing. eLife. 2018 doi: 10.7554/eLife.35383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fornstedt N, Porath J. Characterization studies on a new lectin found in seeds of Vicia ervilia. FEBS Lett. 1975;57:187–191. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80713-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waterhouse A, et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W296–w303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.