Abstract

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is a common medical condition worldwide. It is an inflammation in the nasal mucosa due to allergen exposure throughout the year. Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is another medical condition that can overlap with AR. LPR can be considered an extra oesophageal manifestation of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) or a different entity. Its diagnosis imposes a real challenge as it has a wide range of unspecific symptoms. Although AR and LPR are not life-threatening, they can severely affect the quality of life for years and cause substantial distress. Moreover, having AR is associated with having asthma which is also in turn associated with GORD. This is a cross-sectional study which used surveys distributed online on Social Media and targeted people across Syria. All participants who responded to the key questions were included. Reflux symptom index (RSI) was used for LPR, and score for allergic rhinitis (SFAR) was used for AR. Demographic questions and whether the participant had asthma were also included in the survey. We found that there was an association between the symptoms of LPR and AR p < 0.0001 (OR, 2.592; 95% CI 1.846–3.639), and their scores were significantly correlated (r = 0.334). Having asthma was associated with LPR symptoms p = 0.0002 (OR 3.096; 95% CI 1.665–5.759) and AR p < 0.0001 (OR 6.772; 95% CI 2.823–16.248). We concluded that there was a significant association between having LPR, AR, and asthma. We need more studies to distinguish between their common symptoms and aetiologies.

Subject terms: Environmental sciences, Medical research, Risk factors, Signs and symptoms

Introduction

Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) occurs when the reflux of gastric contents reaches the upper aerodigestive tract without having heartburn or regurgitation1. LPR can be considered an atypical presentation of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) or a different entity2,3. In Syria, 31.9% suffered of LPR symptoms4. Asthma association with GORD can be explained by the coughing and increased intra-abdominal pressure in asthma which may induce GORD symptoms. On the other hand, gastric reflux can directly damage pulmonary tree, causing bronchoconstriction5–9.

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is one of the most common diseases worldwide; it is an inflammatory medical condition that occurs in the nasal mucosa due to allergens exposure10. AR prevalence ranges from 5 to 22% worldwide11. Moreover, a survey in the Middle East found that 10% of responders had AR12. However, AR symptoms were found in around half of the population in one study in Syria13. Although AR is not life-threatening, it affects the quality of life and predisposes to multiple airway conditions14–17. AR and asthma can be viewed as two corresponding airway diseases as they have common characteristics18. AR has a wide variety of symptoms including sneezing, nasal itching, rhinorrhoea, and nasal congestion/obstruction19,20. A causal link between GORD and AR was not established, and only a few studies indicated an association21. However, as AR and LPR have many symptoms in common from the irritation of the aerodigestive tract, they may be associated with one another which was suggested by many studies regardless of having asthma22,23.

In this study, we used reflux symptom index (RSI)24–28 to assess LPR symptoms, and score for allergic rhinitis (SFAR)29,30 to assess AR symptoms. We aim to determine the association between LPR, AR, and asthma.

Methods and materials

This is a cross-sectional study that was conducted in Syria. Online surveys were used to cover the largest population possible. Surveys were distributed to different Social Media groups that covered different topics. Demographic questions were asked such as gender, and age. People from across all Syria could participate. We included any person who accepted to participate, lived Syria, and answered key questions. The surveys were posted multiple times during the day in March in 2019. No medical diagnosis or follow-ups were conducted.

Ethical approval and consent of participants

This study protocol was approved by faculty of medicine Damascus University deanship ethical committee. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulation and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. STROBE guidelines were used in this study.

Informed consent was taken for participating in the research, and for using and publishing of the data.

Measurements

We used a form of RSI which was validated in Arabic28. RSI is a self-administered questionnaire which relies on a scoring system for symptoms that evaluates the possibility of LPR24,25. RSI is a nine-item scale questionnaire about symptoms suggestive of LPR as shown in the tables. The scale ranges from 0 when answering “no problem” to 5 when answering “severe problem” to each item. The total score ranges from 0 to 45 and the cut-off point was set to 13 or more to suggest the possibility of having LPR-suggestive symptoms.

We also used the Arabic version of SFAR, a simple self-reported tool29,30. SFAR is a structured scoring system that has eight questions about symptoms of AR, the personal and familial history of allergy, and allergy tests. These questions are shown in the tables. SFAR score ranges from 0 to 16 and positive answers earn points which can be added, and the cut-off point was set to 7.

We directly asked about having asthma as we could not perform medical diagnose to the participants. The survey included basic demographics, a question whether or not the participant had asthma, and RSI and SFAR questions. We could not follow-up with medical examination or investigation. We could not determine when the symptoms overlap, and therefore bias could not be reduced.

Data analysis

Data were processed using IBM SPSS software version 26 for Windows (SPSS Inc, IL, USA). Chi-square, independent t-test, and odds ratios (ORs) were used for categorical variables while Pearson correlation coefficient was used for continuous numeral variables. Values of less than 0.05 for the two-tailed p values were considered statistically significant. Any participant with missing data in key questions was eliminated.

Preprint

A previous version of this manuscript was published as a preprint31.

Results

This study included 673 subjects, of which 170 were males and 503 were females with a mean age of 23.9 ± 6.6 years. It was found that 341 (50.7%) had AR, 212 (31.5%) had LPR symptoms, and 44 (6.5%) had asthma. In subjects with AR, 38 out of 341 (11.1%) had asthma. In subjects with LPR symptoms, 25 out of 212 (11.8%) had asthma. This was demonstrated in (Table 1) along with characteristics of subjects, their demographic data, and RSI and SFAR results and scores. We used chi-square and odds-ratio to compare subjects with negative and positive final results (Table 2) and found that having symptoms suggestive of LPR was associated with having AR p < 0.0001 (OR, 2.592; 95% CI 1.846–3.639).

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects, their demographic data, and RSI and SFAR results and scores.

| Characteristic | Frequency (n = 673) | Percentage% |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 170 | 25.3 |

| Female | 503 | 74.7 |

| RSI results | ||

| Positive AR | 341 | 50.7 |

| Negative AR | 332 | 49.3 |

| SFAR results | ||

| Positive LPR symptoms | 212 | 31.5 |

| Negative LPR symptoms | 461 | 68.5 |

| Having asthma | ||

| Across all the sample | 44 | 6.5 |

| Only across subjects with AR | 38 | 11.1 |

| Only across subjects with LPR | 25 | 11.8 |

| Variable | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 23.92 | 6.620 |

| RSI score | 10.50 | 9.085 |

| SFAR score | 6.72 | 3.560 |

| SFAR score in subjects with AR | 8.08 | 3.290 |

| RSI score in subjects with LPR | 13.00 | 9.705 |

| SFAR score in asthmatic subjects | 10.50 | 2.841 |

| SFAR score in non-asthmatic subjects | 6.45 | 3.455 |

| RSI score in asthmatic subjects | 16.14 | 11.645 |

| RSI score in non-asthmatic subjects | 10.11 | 8.756 |

SFAR: score for allergic rhinitis; RSI: reflux symptom index; LPR: laryngopharyngeal reflux; AR: allergic rhinitis; SD: standard deviation.

Table 2.

Comparing positive SFAR score with positive RSI score.

| Characteristic | Positive LPR symptoms | Percentage (CI 95%) | Negative LPR symptoms | Percentage (CI 95%) | P value | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFAR score | ||||||

| Positive allergic rhinitis | 141 | 66.5 | 200 | 43.4 | < 0.000001 | 2.592 (1.846–3.639) |

| Negative allergic rhinitis | 71 | 33.5 | 261 | 56.6 | ||

| SFAR score in subjects with asthma | ||||||

| Positive allergic rhinitis | 22 | 88.0 | 16 | 84.2 | NS | 1.375 (0.245–7.717) |

| Negative allergic rhinitis | 3 | 12.0 | 3 | 15.8 | ||

| SFAR score in subjects without asthma | ||||||

| Positive allergic rhinitis | 119 | 63.6 | 184 | 41.6 | < 0.000001 | 2.454 (1.724–3.492) |

| Negative allergic rhinitis | 68 | 36.4 | 258 | 58.4 | ||

CI: Confidence interval; SFAR: Score for allergic rhinitis; RSI: Reflux symptom index; OR: Odds ratio; NS: Not significant.

Chi-square was used to determine the significance of the comparisons in this table.

Comparing each SFAR item with having LPR using chi-square and odds-ratio is demonstrated in (Table 3). Having symptoms suggestive of LPR was significantly associated with AR symptoms of sneezing, runny nose, blocked nose, nasal symptoms with itchy eyes, time of occurrence, triggers, perceived allergic status, previous medical diagnosis, familial history of allergy and father history of allergy p < 0.05. When excluding subjects with asthma, LPR was still significantly associated with AR p < 0.0001 (OR, 2.454; 95% CI 1.724–3.492). However, if we only included subjects with asthma, no significant association was found p > 0.05 (Table 2). Having asthma was associated with LPR symptoms p = 0.0002 (OR 3.096; 95% CI 1.665–5.759) and AR p < 0.0001 (OR 6.772; 95% CI 2.823–16.248).

Table 3.

Comparing each SFAR item with having positive or negative LPR according to RSI.

| SFAR items | Positive RSI | Percentage | Negative RSI | Percentage | P value | OR (CI = 95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sneezing | ||||||

| Negative | 91 | 42.9 | 267 | 57.9 | 0.0003 | 1.830 (1.317–2.543) |

| Positive | 121 | 57.1 | 194 | 42.1 | ||

| Runny nose | ||||||

| Negative | 88 | 41.6 | 234 | 50.8 | 0.026 | 1.453 (1.046–2.018) |

| Positive | 124 | 58.4 | 227 | 49.2 | ||

| Blocked nose | ||||||

| Negative | 63 | 29.7 | 240 | 52.1 | < 0.0001 | 2.568 (1.816–3.632) |

| Positive | 149 | 70.3 | 221 | 47.9 | ||

| If yes for any of the previous, has this problem been accompanied with itchy eyes | ||||||

| Negative | 87 | 41.0 | 278 | 60.3 | < 0.0001 | 2.183 (1.567–3.040) |

| Positive | 125 | 59.0 | 183 | 39.7 | ||

| In which of the past 12 months (or in which season) did this nose problem occur | ||||||

| Unspecified | 100 | 47.2 | 265 | 57.5 | 0.004a | 1.514 (1.092–2.100)a |

| Pollen season | 30 | 14.2 | 76 | 16.5 | ||

| Perennial | 82 | 38.7 | 120 | 26.0 | ||

| What trigger factors provoke or increase your nose problem? | ||||||

| None | 57 | 26.9 | 189 | 41.0 | 0.002b | 1.890 (1.324–2.697) |

| Animals | 2 | 0.9 | 4 | 0.9 | ||

| Pollens, house dust (mites), dust | 130 | 61.3 | 241 | 52.3 | ||

| All of the above | 23 | 10.8 | 27 | 5.9 | ||

| Do you think to be allergic? | ||||||

| Negative | 81 | 38.2 | 242 | 52.5 | < 0.001 | 1.787 (1.282–2.491) |

| Positive | 131 | 61.8 | 219 | 47.5 | ||

| Have you been tested for allergy (SPT, IgE)? | ||||||

| Negative | 190 | 89.6 | 425 | 92.2 | NS | 1.367 (0.783–2.387) |

| Positive | 22 | 10.4 | 36 | 7.8 | ||

| If yes what was the result | ||||||

| Negative | 9 | 45.0 | 16 | 47.1 | NS | 1.086 (0.358–3.293) |

| Positive | 11 | 55.0 | 18 | 52.9 | ||

| Has a doctor already diagnosed that you suffer/suffered from asthma, eczema, or allergic rhinitis? | ||||||

| Negative | 96 | 45.3 | 309 | 67.0 | < 0.0001 | 2.456 (1.761–3.427) |

| Positive | 116 | 54.7 | 152 | 33.0 | ||

| Is any member of your family suffering from asthma, eczema, or allergic rhinitis? | ||||||

| Negative | 74 | 34.9 | 207 | 44.9 | 0.015 | 1.520 (1.085–2.128) |

| Positive | 138 | 65.1 | 254 | 55.1 | ||

Chi-square was used to determine the significance of the comparisons in this table.

SFAR: Score for allergic rhinitis; RSI: Reflux symptom index; OR: Odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; SPT: skin prick testing; IgE: immunoglobulin E.

aOR was calculated between unspecific and specific with P = 0.013.

bOR was calculated between none and other variables with P < 0.001.

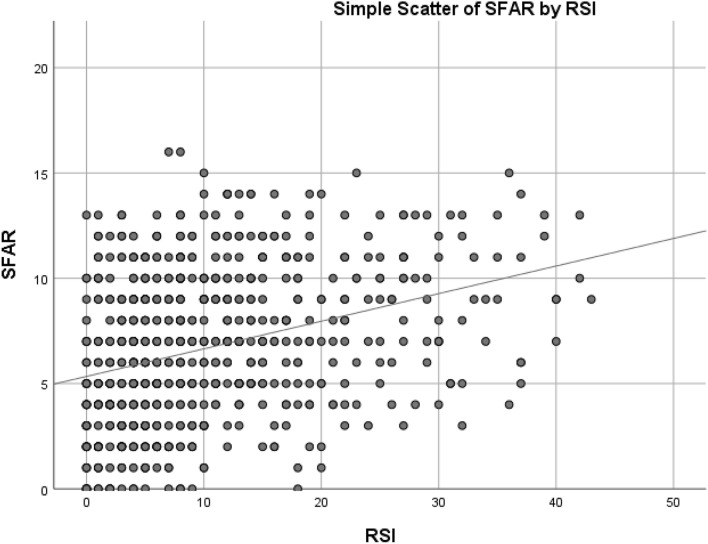

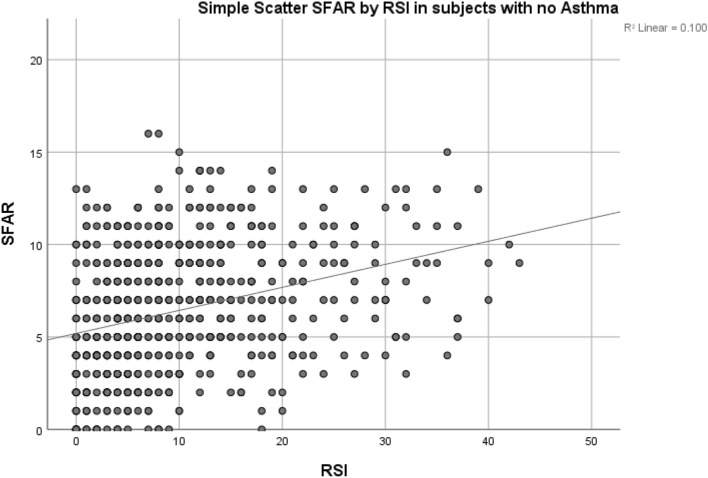

When bivariate Pearson correlation was used to compare the scores of SFAR and RSI, a significant moderate correlation was found r = 0.334 (Fig. 1) with p < 1 × 10–19. Another significant moderate correlation was found r = 0.316 when excluding asthma p < 1 × 10–19 (Fig. 2). However, in subjects who have asthma, no significant correlation was found when comparing scores p > 0.05. Comparing between each RSI item and having AR or not using independent t-test is demonstrated in Table 4. AR symptoms is associated with each LPR symptom as demonstrated in (Table 4) (p < 0.001). Having asthma was associated with higher RSI and SFAR scores (p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Showing the scatter of RSI and SFAR score values in all participants with r = 0.334 at p < 1 × 10–19.

Figure 2.

Showing the scatter of RSI and SFAR score values in subjects when excluding asthma with r = 0.316 at p < 1 × 10–19.

Table 4.

Comparing each RSI item with subjects with positive and negative SFAR.

| RSI items | Mean scores in subjects with positive SFAR ± SD | Mean score (CI 95%) | Mean scores in subjects with negative SFAR ± SD | Mean score (CI 95%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sore throat | 1.04 ± 1.302 | 0.90–1.18 | 0.66 ± 1.056 | 0.55–0.78 | < 0.001 |

| Sputum production | 1.62 ± 1.544 | 1.47–1.79 | 0.98 ± 1.200 | 0.86–1.11 | < 0.001 |

| Excessive secretions | 1.67 ± 1.586 | 1.49–1.84 | 0.84 ± 1.226 | 0.71–0.97 | < 0.001 |

| Dysphagia | 1.10 ± 1.416 | 0.96–1.26 | 0.57 ± 1.090 | 0.46–0.70 | < 0.001 |

| Coughing after eating, sleeping, or lying down | 1.41 ± 1.587 | 1.25–1.57 | 0.98 ± 1.409 | 0.84–1.14 | < 0.001 |

| Breathing difficulties | 1.38 ± 1.529 | 1.22–1.54 | 0.71 ± 1.189 | 0.59–0.84 | < 0.001 |

| Extreme coughing episodes | 1.37 ± 1.594 | 1.20–1.56 | 0.94 ± 1.464 | 0.79–1.11 | < 0.001 |

| A sense of foreign body in throat | 1.46 ± 1.552 | 1.30–1.62 | 0.84 ± 1.248 | 0.70–0.98 | < 0.001 |

| Epigastric burning sense, chest pain, indigestion, and GORD | 1.96 ± 1.732 | 1.78–2.14 | 1.41 ± 1.467 | 1.25–1.56 | < 0.001 |

| Total score | 13.00 ± 9.705 | 11.93–14.04 | 7.93 ± 7.599 | 7.19–8.76 | < 0.001 |

Independent t-test was used to determine the significance of the comparisons in this table.

CI: confidence interval; SFAR: score for allergic rhinitis; RSI: reflux symptom index; SD: standard deviation; GORD: gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

RSI mean score was 10.50 ± 9.085 (CI 95%: 9.83–11.25) and SFAR mean score was 6.72 ± 3.560 (95% CI 6.45, 7.00). SFAR, and RSI scores according to one another and to asthma are demonstrated in (Table 1).

Discussion

AR and LPR association

RSI score in our study was significantly correlated with SFAR score. This was also evident when comparing the results of these two scales as having LPR symptoms was associated with AR symptoms. This was also found when comparing each symptom of LPR with having AR and vice versa. Having either LPR or AR was associated with a 2.6-fold increase in the in risk of having the other. The strength of the correlation between RSI and SFAR scores was moderate in strength (r = 0.334) and demonstrated in (Fig. 1).

This association between LPR and AR in our study is similar to other studies22,23. AR and allergic laryngitis (AL) can have similar manifestations32. Epigastric burning sensation, chest pain, and indigestion were the most common symptoms of LPR in Syria while having a sore throat was the least common4. AR symptoms can include sneezing, nasal itching, rhinorrhoea, and congestion19,20. As AR/AL and LPR can have overlapping symptoms, distinguishing them was proven difficult in one small study19. However, AR and LPR symptoms can overlap and the most common symptoms would be repeated throat cleaning, and a globus sensation22.

The frequent swallowing with AR is due to the itching sensation and post-nasal drip. This frequent swallowing would also increase due to the reflux. Furthermore, nasal mucosa will be affected by AR which leads to LPR as AR causes the mucosa to be congested, oedematous, and increases mucous secretions23. This common effect on the mucosa could explain the association between LPR and AR.

This association could also be explained similarly to the explanation of GORD and AR as they are among the main causes of chronic cough; moreover, increased reoccurrence of the cough with reflux symptom has been reported in patients with GORD and in those without symptoms of GORD who have rhinitis, indicating that other factors contribute to the development of chronic cough. In addition, the coexistence of GORD and chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) were reported by multiple studies21–23,33–35. One theory explaining this phenomena was that Helicobacter pylori, which is usually found in the gastric mucosa and promotes heartburning, could exist in the sinonasal cavity36. Another theory associated GORD with bronchial spasm34,37. However, one study suggested that GORD would only worsen nasal symptom scores but did not cause chronic rhinosinusitis34.

However, although study data showed that placebo can be as effective as PPI therapy, empirical treatment with PPI is still recommended38. Nevertheless, in another study, an association between pH Ryan score and total SFAR score was found, which could be related to LPR22.

LPR diagnosis can be much more complicated with many methods from interviews to challenging treatment methods as LPR has many vague and unspecific symptoms such as throat clearing, globus pharyngeus, and hoarseness25,39,40. Many of the diagnostic methods cannot be used in Syria due to the limited resources as over 80% of the population is under poverty line and most research does not have a proper funding41,42. Non-instrumental methods can also be used such as RSI and the reflux finding score (RFS)24,25, but they cannot be used as the gold standard to diagnose LPR as they are based on symptoms.

The diagnosis of AR is based on a detailed clinical history and skin prick test. Serum specific IgE to the whole allergen extracts or components could be used as second- and third-line tests, respectively. The association between the clinical evaluation and the results of the mentioned tests is crucial for a correct diagnosis43. This can justify using questionnaire-based tools as their accuracy is acceptable and much cheaper than diagnostic tests, especially in developing countries.

Asthma

We found that having AR and LPR symptoms were significantly associated with having asthma. The association between AR and LPR persisted when including subjects with no asthma. However, there was no association between AR and LPR when only including subjects with asthma, but our study only had 44 subjects with asthma which might not have detected the association. Our study found that having either asthma or AR was associated with a 6.8-fold increase in the incidence of the other. We also found that having either asthma or LPR was associated with a 3.1-fold increase in the incidence of the other. A study in Syria found that asthma, allergies, and respiratory conditions were associated with having LPR symptoms13.

As the larynx exists in a critical location that connects upper and lower airways which have a similar microscopic structure, it is suggested that having a disease in one portion of this system would affect the entire respiratory system44. One study found that about 25% of patients who had AR also had asthma. Having asthma was also associated with having a much higher incidence of AR45. Several previous studies found that having AR or asthma was associated with a threefold increase of having the other and that AR diagnosis was mostly made before asthma presentation46,47.

Socioeconomic status was not studied as it is hard to accurately determine the financial situations in Syria due to rapid changing, different living expenses, and asking directly for month salary being inappropriate41,48.

Limitation

We do acknowledge that our study has many limitations that need to be addressed. The small sample size, for asthma in particular, could be limiting. No clinical diagnosis was made, and only self-reported methods were used which may overestimate the symptoms and render the answers to be subjective. Subjects who do not have online access could not participate. We could not target the population at risk. This study included more females than males and included relatively young participants which may affect the generalizability of the results. The cross-sectional method is also limiting as causality cannot be determined.

The common symptoms of the aerodigestive tract can be misleading and misdiagnosed as either AR or LPR. Moreover, smoking, asthma, mental distress, and allergies may cause the same symptoms by various ways. In Syria, LPR had a prevalence of 31.9% and AR had a prevalence of 47.9%. They were both associated with asthma, allergies, distress from war, and smoking4,13. Moreover, 61.2% of Syrians had moderate to severe mental distress, and 60.8% had symptoms of post-traumatic distress disorder (PTSD)41. School students were also affected as 53% had PTSD symptoms and 62.2% had problematic anger48. All the previous factors can contribute to the high prevalence of symptoms of LPR and AR. We need more studies to accurately determine these associations as LPR and AR have many common factors that can be confounding when detecting their association. Finally, there is a lack of studies about many medical conditions and risk factors in Syria. Furthermore, war and the unique environment of Syria impose different risk factors to many medical conditions which can also be the case for LPR and AR42,49.

In conclusion, many studies had contradicting data about LPR and AR as their definition and methods of diagnosis may differ and overlap. LPR, AR, and asthma are significantly associated with one another which may be attributed to common symptoms and aetiologies. Our study found that having symptoms suggestive of LPR was associated with having AR (OR = 2.6), and a significant positive correlation was found when comparing their scores (r = 0.334). Having asthma was associated with LPR symptoms (OR = 3.1) and AR (OR = 6.8). We need more detailed methods for diagnosis of AR and LPR which both have high prevalence, and better management of these conditions may improve the quality of life for a very large population for years.

Author contributions

All authors reviewed the text. A.K. is the first and senior author. He drafted the text, tables, figures, methods, data input, analysis and organisation. Text finalisation. A.K. and M.A. finalized the text. A.A. and A.K. were responsible for data analysis and organisation. A.A., A.K. and M.A. were responsible for tables organisation and revision. A.G. reviewed the sources, the coherence of text, data collecting organizer and references check and numbers check in tables.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Koufman JA, et al. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: Position statement of the committee on speech, voice, and swallowing disorders of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016;127(1):32–35. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2002.125760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koufman JA, Amin MR, Panetti M. Prevalence of reflux in 113 consecutive patients with laryngeal and voice disorders. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016;123(4):385–388. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.109935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Havemann BD, Henderson CA, El-Serag HB. The association between gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and asthma: A systematic review. Gut. 2007;56(12):1654–1664. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.122465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kakaje A, et al. Laryngopharyngeal reflux in war-torn Syria and its association with smoking and other risks: An online cross-sectional population study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e041183. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castell DO, Schnatz PF. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and asthma. Chest. 1995;108(5):1186–1187. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.5.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Field SK. Asthma and gastroesophageal reflux. Chest. 2002;121(4):1024–1027. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.4.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choy D, Leung R. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and asthma. Respirology. 1997;2(3):163–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.1997.tb00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zerbib F, et al. Effects of bronchial obstruction on lower esophageal sphincter motility and gastroesophageal reflux in patients with asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002;166(9):1206–1211. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200110-033OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ates F, Vaezi MF. Insight into the relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and asthma. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014;10(11):729–736. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dykewicz MS, Fineman S. Executive summary of joint task force practice parameters on diagnosis and management of rhinitis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998;81(5):463–468. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein JA. Allergic and mixed rhinitis: Epidemiology and natural history. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31(5):365–369. doi: 10.2500/aap.2010.31.3380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdulrahman H, et al. Nasal allergies in the middle eastern population: Results from the “Allergies in Middle East Survey”. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy. 2012;26(6_suppl):S3–S23. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kakaje A, et al. Allergic rhinitis and its epidemiological distribution in Syria: A high prevalence and additional risks in war time. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020;2020:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2020/7212037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nathan RA. The burden of allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2007;28(1):3–9. doi: 10.2500/aap.2007.28.2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woolcock AJ, et al. The burden of asthma in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2001;175(3):141–145. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beasley R, The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. Lancet. 1998;351(9111):1225–1232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trikojat K, et al. Memory and multitasking performance during acute allergic inflammation in seasonal allergic rhinitis. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2017;47(4):479–487. doi: 10.1111/cea.12893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan DA. Allergic rhinitis and asthma: Epidemiology and common pathophysiology. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014;35(5):357–361. doi: 10.2500/aap.2014.35.3794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Randhawa P, Mansuri S, Rubin J. Is dysphonia due to allergic laryngitis being misdiagnosed as laryngopharyngeal reflux? Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocol. 2009;35:1–5. doi: 10.1080/14015430903002262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turley R, et al. Role of rhinitis in laryngitis: Another dimension of the unified airway. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2011;120(8):505–510. doi: 10.1177/000348941112000803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katle E-J, Hatlebakk JG, Steinsvåg S. Gastroesophageal reflux and rhinosinusitis. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013;13(2):218–223. doi: 10.1007/s11882-013-0340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alharethy S, et al. Correlation between allergic rhinitis and laryngopharyngeal reflux. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018;2018:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2018/2951928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kung Y-M, et al. Allergic rhinitis is a risk factor of gastro-esophageal reflux disease regardless of the presence of asthma. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37186-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. The validity and reliability of the reflux finding score (RFS) Laryngoscope. 2001;111(8):1313–1317. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom index (RSI) J. Voice. 2002;16(2):274–277. doi: 10.1016/S0892-1997(02)00097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wise SK, Wise JC, DelGaudio JM. Gastroesophageal reflux and laryngopharyngeal reflux in patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016;135(2):253–257. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelchner LN, et al. Reliability of speech-language pathologist and otolaryngologist ratings of laryngeal signs of reflux in an asymptomatic population using the reflux finding score. J. Voice. 2007;21(1):92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farahat M, Malki KH, Mesallam TA. Development of the Arabic version of reflux symptom index. J. Voice. 2012;26(6):814.e15–814.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Annesi-Maesano I, et al. The score for allergic rhinitis (SFAR): A simple and valid assessment method in population studies. Allergy. 2002;57(2):107–114. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.1o3170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alharethy S, et al. Validation of the Arabic version of the score for allergic rhinitis tool. Ann. Saudi Med. 2017;37(5):357–361. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2017.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kakaje, A., Alhalabi, M. M., Alyousbashi, A., Ghareeb, A. Allergic rhinitis, asthma and gastro-esophageal reflux disease: a cross-sectional study on their reciprocal relations. Preprint at 10.21203/rs.3.rs-29393/v1 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Krouse JH, Altman KW. Rhinogenic laryngitis, cough, and the unified airway. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2010;43(1):111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.García-Compeán D, et al. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with extraesophageal symptoms referred from otolaryngology, allergy, and cardiology practices: A prospective study. Dig. Dis. 2000;18(3):178–182. doi: 10.1159/000051392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanna BC, Wormald PJ. Gastroesophageal reflux and chronic rhinosinusitis. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2012;20(1):15–18. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e32834e8f11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loehrl TA, Smith TL. Chronic sinusitis and gastroesophageal reflux: Are they related? Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2004;12(1):18–20. doi: 10.1097/00020840-200402000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zdek A, et al. A possible role of helicobacter pylori in chronic rhinosinusitis: A preliminary report. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(4):679–682. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200304000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong IWY, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and chronic sinusitis: In search of an esophageal–nasal reflex. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy. 2010;24(4):255–259. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2010.24.3490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bytzer P. Management of laryngopharyngeal reflux with proton pump inhibitors. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2008;4:225–233. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S6862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pribuisiene R, Uloza V, Jonaitis L. Typical and atypical symptoms of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. Medicina. 2002;38(7):699–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oelschlager BK, et al. Typical GERD symptoms and esophageal ph monitoring are not enough to diagnose pharyngeal reflux. J. Surg. Res. 2005;128(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kakaje, A. et al.Mental disorder and PTSD in Syria during wartime: a nationwide crisis (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Kakaje A, et al. Rates and trends of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: An epidemiology study. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):1–2. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63528-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ansotegui IJ, et al. IgE allergy diagnostics and other relevant tests in allergy, a World Allergy Organization position paper. World Allergy Organ. J. 2020;13(2):100080. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2019.100080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krouse JH. The unified airway—Conceptual framework. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2008;41(2):257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Compalati E, et al. The link between allergic rhinitis and asthma: The united airways disease. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2014;6(3):413–423. doi: 10.1586/eci.10.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huovinen E, et al. Incidence and prevalence of asthma among adult Finnish men and women of the Finnish twin cohort from 1975 to 1990, and their relation to hay fever and chronic bronchitis. Chest. 1999;115(4):928–936. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.4.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Settipane RJ, Hagy GW, Settipane GA. Long-term risk factors for developing asthma and allergic rhinitis: A 23-year follow-up study of college students. Allergy Asthma Proc. 1994;15(1):21–25. doi: 10.2500/108854194778816634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kakaje A, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anger and mental health of school students in Syria after nine years of conflict: A large-scale school-based study. Pyschol. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1017/S0033291720003761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al Habbal, A. et al. Risk factors associated with epilepsy in children and adolescents: A case-control study from Syria. Epilepsy Behav. (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]