Abstract

The purpose of this study was to establish a high-performing radiomics strategy with machine learning from conventional and diffusion MRI to differentiate recurrent glioblastoma (GBM) from radiation necrosis (RN) after concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) or radiotherapy. Eighty-six patients with GBM were enrolled in the training set after they underwent CCRT or radiotherapy and presented with new or enlarging contrast enhancement within the radiation field on follow-up MRI. A diagnosis was established either pathologically or clinicoradiologically (63 recurrent GBM and 23 RN). Another 41 patients (23 recurrent GBM and 18 RN) from a different institution were enrolled in the test set. Conventional MRI sequences (T2-weighted and postcontrast T1-weighted images) and ADC were analyzed to extract 263 radiomic features. After feature selection, various machine learning models with oversampling methods were trained with combinations of MRI sequences and subsequently validated in the test set. In the independent test set, the model using ADC sequence showed the best diagnostic performance, with an AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, specificity of 0.80, 78%, 66.7%, and 87%, respectively. In conclusion, the radiomics models models using other MRI sequences showed AUCs ranging from 0.65 to 0.66 in the test set. The diffusion radiomics may be helpful in differentiating recurrent GBM from RN.

.

Subject terms: Cancer, Machine learning, Diagnostic markers

Introduction

The current gold standard treatment for glioblastoma (GBM, World Health Organization [WHO] grade IV) is maximum safe tumor resection, followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) with temozolomide1,2. In cases of elderly patients with unmethylated 6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter status or patients with Karnofsky performance status (KPS) index lower than 70, radiotherapy (RT) alone is the standard treatment2,3. Radiation necrosis (RN) usually occurs within 3 years after radiation therapy and is often indistinguishable from recurrent tumor because it manifests as an enhancing mass lesion with varying degrees of surrounding edema and progressive enhancement on serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)4,5. Thus, distinguishing between recurrent GBM and RN has clinical importance in deciding the subsequent management; recurrence indicates treatment failure and requires the use of additional anticancer therapies, whereas RN is treated conservatively.

Multiple studies have made efforts to distinguish GBM recurrence from RN using various imaging methods, including conventional imaging, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), diffusion tensor imaging, dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC) imaging, MR spectroscopy, amide proton transfer imaging, and positron emission tomography4–13. However, there is no gold standard imaging method for the differentiation between recurrence and RN, due to high degree of overlapping findings. Currently, the definitive diagnosis is based on histopathology which is both invasive and difficult. In addition, the pathology results may be variable depending on the surgical sampling sites due to the coexistence and admixture of recurrence and RN14.

Radiomics involves the identification of ample quantitative features within images and the subsequent data mining for information extraction and application15. Recent studies have shown promising results in predicting the molecular status, grade, and prognosis of gliomas16–20. Because radiomics models use high-throughput features, there are prone to discover invisible information which are inaccessible with single-parameter analysis.

The aim of this study was to develop and validate a high-performing radiomic strategy using machine learning classifiers from conventional imaging and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) to differentiate recurrent GBM from RN after concurrent CCRT or radiotherapy.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the patients

The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Of the 86 patients in the training set, 63 (73.3%) were classified as recurrent GBM and 23 (26.7%) as RN cases. The 41 patients in the test set consisted of 23 (56.1%) recurrent GBM and 18 (43.9%) RN cases. There were no significant differences in age, sex, extent of resection, first line treatment (either CCRT or RT alone/RT plus temozolomide), total radiation dose, isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) mutation status, and MGMT methylation status between patients with recurrent GBM and those with RN within both training and test sets.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic data and clinical characteristics of patients.

| Variables | Training set (n = 86) | Test set (n = 41) | P-valueb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrent GBM | RN | P-valuea | Recurrent GBM | RN | P-valuea | ||

| Patient no | 63 | 23 | – | 23 | 18 | – | |

| Age (years) | 54.4 ± 13.0 | 57.9 ± 10.6 | 0.255 | 60.7 ± 11.8 | 57.0 ± 13.7 | 0.358 | 0.571 |

| Female sex | 20 (31.7) | 7 (30.4) | 0.908 | 10 (43.5) | 8 (44.4) | 0.951 | 0.851 |

| KPS | 73.8 ± 17.0 | 73.9 ± 19.2 | 0.974 | 60.7 ± 11.8 | 57.0 ± 13.7 | 0.394 | 0.961 |

| Extent of resection | 0.644 | 0.556 | 0.757 | ||||

| Biopsy | 7 (11.1) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (5.6) | |||

| Partial | 11 (17.5) | 5 (21.7) | 7 (30.4) | 3 (16.7) | |||

| Subtotal | 24 (38.1) | 11 (47.8) | 13 (56.5) | 10 (55.6) | |||

| Total | 21 (33.3) | 6 (26.1) | 2 (8.7) | 4 (22.2) | |||

| First-line treatment | 0.3115 | 0.370 | 0.418 | ||||

| CCRT | 60 (93.7) | 20 (87.0) | 22 (95.7) | 17 (94.4) | |||

| RT alone or RT plus temozolomide | 4 (6.3) | 3 (13.0) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (5.6) | 0.859 | ||

| Total radiation dose (Gy) | 60.2 ± 11.6 | 61.9 ± 16.1 | 0.591 | 56.3 ± 11.4 | 60.7 ± 8.1 | 0.251 | 0.476 |

| IDH1 mutant | 2 (3.2) | 2 (8.7) | 0.282 | 1 (4.3) | 1 (5.6) | 0.859 | 0.342 |

| MGMT promoter methylation | 13 (20.6) | 9 (39.1) | 0.082 | 8 (34.8) | 7 (38.9) | 0.786 | 0.090 |

GBM glioblastoma, RN radiation necrosis, KPS Karnosfky performance status, MGMT oxygen 6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase.

Data are presented as either mean ± standard deviation or numbers of patients (%).

aCalculated from Student t test for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables for comparison of recurrent GBM and RN in training and test sets.

bCalculated from Student t test for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables for comparison of training and test sets.

Qualitative imaging analysis

The radiologists’ assessment of conventional imaging features showed no significant difference between recurrent GBM and RN in maximum lesion diameter, involvement of corpus callosum, and “Swiss cheese” or “spreading wavefront” enhancement pattern in both the training set and test sets (all p-values > 0.05), respectively.

Best performing machine learning models from radiomics features for differentiating recurrent GBM from RN in the training set

Using radiomic features, in each combination of the selected MRI sequence, the 3 feature selection, 3 classification methods, and 2 oversampling methods were trained.

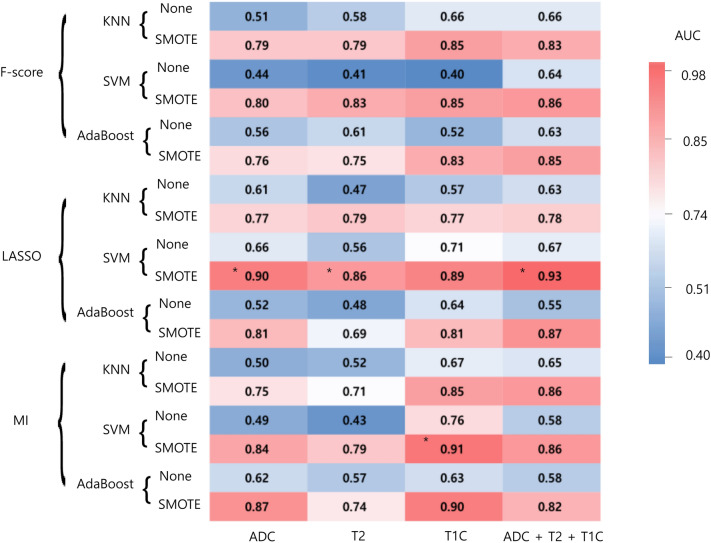

The performance of each combination of the models is shown in Fig. 1. In the training set, the area under the curve (AUCs) of the models showing the best diagnostic performance ranged from 0.86 to 0.93 in each combination. AUCs with oversampling were higher than those without oversampling in all combinations. In the ADC sequence, the combination of least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) feature selection, and support vector machine (SVM) showed the best diagnostic performance in the training set. The selected 18 features consisted of 3 first-order features, 10 s-order features, and 5 shape features (Detailed information at Supplementary Table 3). This model demonstrated an area under the curve (AUC), accuracy, sensitivity, specificity of 0.90 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.84–0.95), 80.5%, 78.3%, and 82.9%, respectively. In the T2WI (T2) sequence, the combination of LASSO feature selection and SVM showed the best diagnostic performance in the training set with an AUC of 0.86 (95% CI 0.80–0.91). In the postcontrast T1WI (T1C) sequence, the combination of mutual information (MI) feature selection and SVM showed the best diagnostic performance in the training set with an AUC of 0.91 (95% CI 0.86–0.95). In the combined sequence (ADC + T2 + T1C), the combination of LASSO feature selection, and SVM showed the best diagnostic performance in the training set with an AUC of 0.93 (95% CI 0.89–0.97). (Hyperparameters for each model are summarized at Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 1.

Heatmap depicting the diagnostic performance (AUCs) of combinations of feature selection methods, classifiers, and combination of sequences in the training set. AUC area under the curve, KNN k-nearest neighbors, MI mutual information, LASSO least absolute shrinkage and selection operator, SMOTE synthetic minority over-sampling technique, SVM support vector machine, T1C postcontrast T1WI, T2 T2WI. The best performing model in each combination of MRI sequence and mask are marked in asterisks (*).

Robustness of radiomics models in the test set

In the independent test set, the model using ADC sequence with the combination of LASSO feature selection and SVM showed the best diagnostic performance. This model demonstrated an AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, specificity of 0.80 (95% CI 0.65–0.95), 78%, 66.7%, and 87%, respectively.

The radiomics models using other combination of MRI sequence showed poor performance (AUCs ranging from 0.65 to 0.66) in the test set, although it did not reach significant difference from the ADC radiomics model (p-values of > 0.05). Table 2 summarizes the results of best performing models in training and test sets.

Table 2.

Diagnostic performance of the best performing machine learning model in the training set and the test set.

| Sequence | Feature selection | No. of selected features | Classification | Training set | Test set | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (95% CI) | Accuracy (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | P-value* | AUC (95% CI) | Accuracy (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | P-value* | ||||

| ADC | LASSO | 18 | SVM | 0.90 (0.84–0.95) | 80.5 (77.4–83.6) | 78.3 (64.2–92.4) | 82.9 (74.7–91.1) | Reference | 0.80 (0.65–0.95) | 78.0 (62.4–89.4) | 66.7 (41.0–86.7) | 87.0 (66.5–97.2) | Reference |

| T2 | LASSO | 21 | SVM | 0.86 (0.80- 0.91) | 77.1 (74.1–80.1) | 80.7 (70.8–90.6) | 73.1 (66.0–80.2) | 0.346 | 0.65 (0.48–0.82) | 61.0 (44.5–75.8) | 44.4 (21.5–69.2) | 73.9 (51.6–89.9) | 0.186 |

| T1C | MI | 30 | SVM | 0.91 (0.86–0.95) | 87.4 (84.5–90.3) | 90.7 (83.0–98.4) | 84.3 (78.2–90.4) | 0.798 | 0.66 (0.49–0.83) | 53.7 (37.4–69.3) | 11.1 (1.4–34.7) | 87.0 (66.4–97.2) | 0.217 |

| ADC + T2 + T1C | LASSO | 35 | SVM | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) | 85.2 (82.0–88.4) | 79.8 (71.2–88.4) | 90.5 (83.0–98.0) | 0.405 | 0.66 (0.49–0.84) | 63.4 (46.9–77.9) | 38.9 (17.3–64.3) | 82.6 (61.2–95.0) | 0.217 |

All training set performance was calculated on SMOTE generated datasets.

CI confidence interval, LASSO least absolute shrinkage and selection operator, MI mutual information, SMOTE synthetic minority over-sampling technique, SVM support vector machine, T1C postcontrast T1WI, T2 T2WI.

*P-value refers to the significance among the differences of the AUCs between the ADC radiomics model and the other models.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the ability of conventional and diffusion radiomics to differentiate recurrent GBM from RN. Several MR sequences and their combination were investigated and validated externally, and among these models the diffusion radiomics model showed robustness with AUC of 0.80. RN has been reported to occur in approximately 9.8–44.4% of treated gliomas, which shows low incidence than recurrent GBM6,9,21. In our study, the data imbalance was mitigated by using a systematic algorithm, which generates synthetic samples in the minority class22. The performance was increased when synthetic minority over-sampling technique (SMOTE) was applied in our dataset (Fig. 1), showing its efficacy. Although recurrent GBM and RN have similar radiologic appearances, they harbor distinct radiomic information that can be extracted and used to build a clinically relevant predictive model that discriminates recurrent GBM from RN. Our model may aid in deciding the subsequent management of these patients.

Although conventional findings such as “Swiss cheese” or “spreading wavefront” enhancement pattern have been reported to show differences between recurrent high-grade glioma and RN in earlier studies5,6, these findings have subsequently been reported that they cannot be reliably used alone in differentiating between the two conditions4,23. Moreover, these conventional imaging patterns are highly subjective. Various studies implementing advanced imaging parameters such as diffusion MRI, DSC MRI, proton MR spectroscopy (MRS), amide proton transfer (APT) imaging, and positron emission tomography (PET) have shown promising results in differentiating recurrent GBM from RN9,11,12,24–26. Although APT imaging has shown higher diagnostic performance than MRS27 or 11C-MET PET28 in differentiating recurrent GBM from RN, APT imaging is challenging due to long scan times and limited coverage with high radiofrequency power. On the other hand, the accuracy of MRS and PET in differentiating recurrent GBM from RN has been questioned; a meta-analysis has shown moderate sensitivity and specificity for MRS, 18F-FDG, and 11C-MET PET in distinguishing between recurrent GBM from RN29, whereas another study found no difference between recurrence and necrosis groups using 18F-FDG and 11C-MET PET12. MRS and PET also have limited value in practical clinical settings due to their limited availability and low cost-effectiveness. DSC MRI can readily distinguish between recurrent GBM and RN, as a biomarker of angiogenesis, with higher availability9,30. However, the relative cerebral blood volume from DSC MRI can produce false positive or false negative results due to volume averaging, susceptibility artifacts, and overlapping portions in RN and recurrent GBM4,31. Also, the optimal thresholds are different depending on the specific protocol9,32, and values derived from DSC imaging are relative values compared to absolute values from ADC maps. Moreover, the previous studies using advanced imaging focused on single parameters such as mean values.

In contrast to extraction of single parameters, radiomics extracts high-throughput quantitative features within the regions of interest and has been reported to be a potentially useful approach for estimating the molecular status, grade, and prognosis of brain tumors16,17,19,20,33,34. Previous studies have showed promising results in identifying recurrent brain tumor from RN using radiomics35–37. However, these studies were focused on recurrent brain metastases rather than recurrent GBM, analyzing only conventional MRI sequences, and most datasets were small without external validation. Recent studies implemented radiomics model in differentiating recurrent glioma from RN38,39; however the studies was either performed in a smaller dataset without external validation using only conventional MRI38, or performed radiomics analysis using 18F-FDG and 11C-MET PET39, which are not routinely acquired imaging modalities. Our radiomics model implemented not only conventional MRI but also ADC map, which are recommended sequences in the glioma protocol40,41, and showed that diffusion radiomics model could robustly differentiate recurrent GBM from RN better than any other radiomics model. However, models using conventional MRI sequences (such as T2 or T1C) showed AUCs ranging from 0.650 to 0.662 in the test set. Moreover, multiparametric radiomics model did not show increased performance than the diffusion radiomics model in the external validation. The signal intensities in conventional images may differ in different MRI protocol settings, leading to poor performance in an external validation even after signal intensity normalization. On the other hand, ADC maps extract absolute values creating reliable feature extraction, which may be less affected by heterogeneous protocol settings and consequently demonstrated high diagnostic performance in the external validation. In addition, our results may emphasize the importance of domain-specific knowledge in the relatively small data settings of radiomics study42. Previous studies have shown that the ADC characteristics are more important than conventional characteristics in differentiating RN from GBM4,7. The diffusion radiomics model is promising for reflecting the tumor microenvironment, since these values can contain biological information43,44. Although ADC value can be affected by various factors, ADC in tumor is generally considered to be an index of tumor cellularity that reflects tumor burden45,46. On histopathological examination, recurrent GBM is characterized by dense glioma cells, which limit water diffusion7. In contrast, RN is characterized by extensive fibrinoid necrosis, vascular dilatation, and gliosis47. The different histopathology and spatial complexity may be reflected in diffusion radiomics, allowing the differentiation of the two entities31.

In our study, the majority of significant radiomics features from the diffusion radiomics model were various second-order features, suggesting that high‐throughput characteristics can provide more accurate assessment. The hypothesis for this observation is that second-order features capture the spatial variation in signal intensity, which tend to extract information that may be incomprehensible and invisible to the naked eye. Recent studies have demonstrated that second-order features also reflect the underlying histology48,49. However, a future study with histopathologic correlation is mandatory to prove our hypothesis of the direct relationship between radiomic features in recurrent GBM and RN. Various features such as flatness, sphericity, mesh volume, and major axis length were included, suggesting that the quantitative shape features may aid in differentiating in recurrent GBM from RN. Because there was no previous study that has quantified various shape features from the whole 3D lesion, further studies are indicated to validate our results.

Our study has several limitations. First, our study was retrospective with a small data size. Due to the relatively small size of the test set, the 95% CIs of the AUCs in the test set tended to have a large range and some 95% CIs of the radiomics models cross 0.5. Future studies should be performed with a larger dataset. Second, DSC imaging was not included due to lack of data in a portion of patients. Because DSC data is important in distinguishing recurrent GBM from RN50, further radiomics studies implementing DSC data are warranted to evaluate the efficacy. Third, fluid-attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence was not utilized in this study due to mixture of both precontrast and postcontrast FLAIR sequences in the training set. Further studies are warranted to include the FLAIR sequence in radiomics analysis. Fourth, clinical factors were not integrated into the radiomics model due to statistical insignificance in our dataset. However, as previous studies have stated the relationship between radiation doses or fractionation schemes with RN51,52, future radiomics studies with larger datasets should perform multivariable analysis with clinically relevant features to differentiate recurrent GBM from RN. Fifth, cross-validation was performed separately in the feature selection stage and the machine learning classification stage, which may have led to overfitted results.

In conclusion, the diffusion radiomics model may be helpful in differentiating recurrent GBM from RN.

Methods

Patient population

The Yonsei University Institutional Review Board waived the need for obtaining informed patient consent for this retrospective study. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulation. For research limited to patients' medical records, access was cleared by the Yonsei University Institutional Review Board and was supervised by a person (S-K.L.) who was fully aware of the confidentiality requirements. All of the study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board (Severance Hospital, Yonsei University Health System Institutional Review Board, 2018-1472-002). Between February 2016 and February 2019, 90 patients with pathologically diagnosed GBM (WHO grade IV) from our institution were reviewed in this study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) GBM confirmed by histopathology; (2) postoperative CCRT or RT, with a radiation dose ranging from 45 to 70 Gy; (3) subsequent development of a new or enlarging region of contrast enhancement within the radiation field 12 weeks after CCRT or RT; and (4) surgical resection of the enhancing lesion or adequate clinicoradiological follow-up, which enabled us to diagnose recurrent GBM or RN. For clinicoradiological diagnosis, a final diagnosis of recurrent GBM was made if the contrast-enhancing lesions gradually enlarged on more than two subsequent follow-up MRI studies performed at 2–3 month intervals (with a size criterion of an increase of > 25% of the size of a measurable [> 1 cm] enhancing lesion according to the sum of the products of perpendicular dimensions) and the clinical symptoms of patients showed gradual deterioration during follow-up28. Alternatively, a final diagnosis of RN was made if enhancing lesions gradually decreased on more than two subsequent follow-up MRI studies performed at 2–3 month intervals and clinical symptoms improved during the follow-up period. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) processing error (n = 3), (2) absence of MRI sequences (n = 1). Thus, a total of 86 patients were enrolled.

Identical inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied and 41 patients from another institutional hospital (Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea) were enrolled in the test set. The clinical characteristics of the patients included age, sex, KPS, IDH mutational status, MGMT promoter methylation status, and the extent of resection of the tumor (gross total resection, subtotal resection, partial resection, or biopsy).

Pathological diagnosis

All patients underwent initial surgery, and histologic confirmation was obtained according to the 2016 WHO classification46. Peptide nucleic acid-mediated clamping polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemical analysis were performed to detect the R132H mutation status in IDH153. MGMT promoter methylation status was diagnosed on the basis of methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction54.

Twenty-two and 14 patients underwent second-look operations in the training set and test set, respectively. In second-look operations, the pathological diagnoses included 17 recurrent GBM and 5 RN cases in the training set, and 8 recurrent GBM and 6 RN cases in the test set, respectively. The diagnosis was made on the basis of histological findings in contrast-enhancing tissue obtained with surgical tumor resection or image-guided. More than 5% viable tumor diagnosed during the histological examination by neuropathologists, were classified as a recurrent GBM9.

MRI protocol

In the training set, all patients underwent MRI on a 3.0-T MRI scanner (Achieva or Ingenia, Philips Medical Systems) with an 8-channel head coil. The preoperative MRI sequences included T1WI, T2, T1C, as well as ADC scans. After 5–6 min of administration of 0.1 mL/kg of gadolinium-based contrast material (Gadovist; Bayer), T1C were acquired.

In the external validation set, MRI exams were performed using a 3.0-T MRI scanner (Achieva, Philips Medical Systems) with an 8-channel head coil. Scaling and un-normalization of ADC pixel values generated at the scanner was performed as previously described55. Constant level appearance (CLEAR) processing, a technique to achieve homogeneity correction by using coil sensitivity maps acquired in the reference scan, was performed55. The acquisition protocols are described in further details in the Supplementary Table 1.

Qualitative image analysis

Conventional images were analyzed by two neuroradiologists (with 14 years and 7 years of experience) for maximum lesion diameter, involvement of corpus callosum, and “Swiss cheese” or “spreading wavefront” (ill-defined margins of the enhancement) enhancement pattern, according to previous literature5,6. Discrepancies were settled by consensus.

Image preprocessing and radiomics feature extraction

Preprocessing of T2, T1C images, and ADC map was performed to standardize the data analysis among patients. Low-frequency intensity nonuniformity was corrected by applying the N4 bias correction algorithm as implemented in the Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTs)56. Signal intensity normalization was used to reduce variance in the T2 and T1C images, by applying the WhiteStripe method from R package57. T2, T1C, and ADC images were resampled to a uniform voxel size of 1 × 1 × 1 mm. T2 and ADC images were registered to the T1C image using affine transformation with normalized mutual information as a cost function. Tumor segmentation was performed through a consensus discussion of two neuroradiologists (with 14 years and 7 years of experience), in order to select the contrast-enhancing solid portion of the tumor on T1C images. Segmentation was performed semiautomatically with an interactive level-set region of interest, using edge-based and threshold-based algorithms using 3D Slicer (version 4.11.0). There was no distortion in the ADC images that affected the segmented masks. Radiomic features were extracted from the segmented mask, with a bin size of 32, with an open-source python-based module (PyRadiomics, version 2.0)58, which was adherent to the Image Biomarker Standardization Initiative (IBSI) guideline59. A total of 93 radiomic features, including shape, first order features, and second-order features (Supplementary Table 2), were extracted from the mask. In addition, edge contrast calculation was performed, that characterizes the tumor border, as previously described (Supplementary Information S1)60. The final set consisted of 263 radiomic features (14 shape features + 83 first-order and second-order 14 features × 3 sequences) for each patient. The data were processed using a multi-platform, open-source software package (3D slicer, version 4.6.2-1; http://slicer.org).

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared between recurrent GBM and RN patients using chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, independent t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables, and Mann–Whitney U-tests for continuous variables without normal distribution. DeLong’s method was used to compare the AUCs among the ADC radiomics model and other radiomics models in the training and test sets61. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

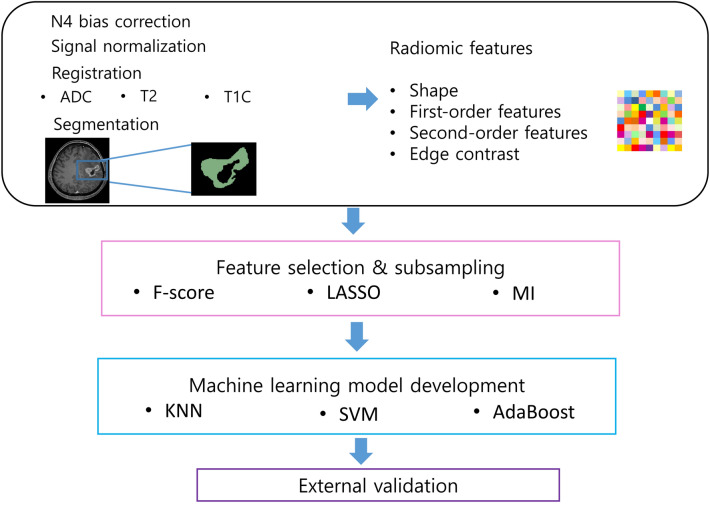

Radiomic feature selection and machine learning

The schematic of the radiomics pipeline is shown in Fig. 2. All radiomic features were normalized using z-score normalization. For feature selection, the F-score, LASSO, or MI with stratified ten-fold cross-validation were applied62. After feature selection, the machine learning classifiers were constructed separately using k-nearest neighbors (KNN), SVM, or AdaBoost, with stratified ten-fold cross-validation. The optimal hyperparameters producing the highest AUC were selected by random search during cross-validation and subsequently used to get the final model. In addition, to overcome data imbalance, each machine learning model was trained either without oversampling or with SMOTE (with a 1:1 ratio)22. Because we wanted to determine which combination of MRI sequence shows the highest performance, the identical process was performed in each sequence (ADC, T2, T1C, and combined ADC, T2, and T1C model). Thus, various combinations of classification models were trained to differentiate recurrent GBM from RN in the training set. AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity were obtained in the SMOTE generated dataset in the training set, with a cutoff value according to Youden’s index. The different feature selection, classification methods, and oversampling were computed using MatlabR2014b (Mathworks). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Figure 2.

The radiomics pipeline of our study. KNN k-nearest neighbors, MI mutual information, LASSO least absolute shrinkage and selection operator, SVM support vector machine, T1C postcontrast T1WI, T2 T2WI.

Diagnostic performance in the test set

Based on the radiomics classification model in the training set, the best combination of feature selection, classification methods, and oversampling in each sequence was used in the test set. The AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity were obtained with the same cutoff from the training set.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This research received funding from the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, Information and Communication Technologies & Future Planning (2017R1D1A1B03030440 and 2020R1A2C1003886). This research was also supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2020R1I1A1A01071648). This research was also supported financially by the fund of Korean Society for Neuro Oncology.

Abbreviations

- ADC

Apparent diffusion coefficient

- APT

Amide proton transfer

- CI

Confidence interval

- DWI

Diffusion-weighted imaging

- DSC

Dynamic susceptibility contrast

- IDH1

Isocitrate dehydrogenase1

- KNN

K-nearest neighbors

- KPS

Karnofsky performance status

- LASSO

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- MGMT

Oxygen 6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase

- MI

Mutual information

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MRS

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- SMOTE

Synthetic minority over-sampling technique

- SVM

Support vector machine

- T1C

Postcontrast T1WI

- T2

T2WI

- GBM

Glioblastoma

- RN

Radiation necrosis

- RT

Radiation therapy

Author contributions

S.S.A. designed the study. J.H.C. and S.H.K. compiled the institutional database. J.E.P. and H.S.K. provided external validation dataset. D.C, H.K., and S.-K.L designed the radiomics pipeline and D.C. performed the radiomics analyses. Y.W.P. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and S.S.A. provided the critical revision of the manuscript. S.-K.L. supervised the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-82467-y.

References

- 1.Stupp R, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weller M, et al. European Association for Neuro-Oncology (EANO) guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of adult astrocytic and oligodendroglial gliomas. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e315–e329. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee J, Ahn SS, Chang JH, Suh C-O. Hypofractionated re-irradiation after maximal surgical resection for recurrent glioblastoma: Therapeutic adequacy and its prognosticators of survival. Yonsei Med. J. 2018;59:194–201. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2018.59.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah R, et al. Radiation necrosis in the brain: Imaging features and differentiation from tumor recurrence. Radiographics. 2012;32:1343–1359. doi: 10.1148/rg.325125002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar AJ, et al. Malignant gliomas: MR imaging spectrum of radiation therapy-and chemotherapy-induced necrosis of the brain after treatment. Radiology. 2000;217:377–384. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.2.r00nv36377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullins ME, et al. Radiation necrosis versus glioma recurrence: Conventional MR imaging clues to diagnosis. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1967–1972. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hein PA, Eskey CJ, Dunn JF, Hug EB. Diffusion-weighted imaging in the follow-up of treated high-grade gliomas: Tumor recurrence versus radiation injury. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2004;25:201–209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu J-L, et al. Distinction between postoperative recurrent glioma and radiation injury using MR diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroradiology. 2010;52:1193–1199. doi: 10.1007/s00234-010-0731-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barajas RF, Jr, et al. Differentiation of recurrent glioblastoma multiforme from radiation necrosis after external beam radiation therapy with dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging. Radiology. 2009;253:486–496. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2532090007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabinov JD, et al. In vivo 3-T MR spectroscopy in the distinction of recurrent glioma versus radiation effects: Initial experience. Radiology. 2002;225:871–879. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2253010997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou J, et al. Differentiation between glioma and radiation necrosis using molecular magnetic resonance imaging of endogenous proteins and peptides. Nat. Med. 2011;17:130. doi: 10.1038/nm.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim YH, et al. Differentiating radiation necrosis from tumor recurrence in high-grade gliomas: Assessing the efficacy of 18F-FDG PET, 11C-methionine PET and perfusion MRI. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2010;112:758–765. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park, Y. W. et al. Differentiation of recurrent diffuse glioma from treatment-induced change using amide proton transfer imaging: incremental value to diffusion and perfusion parameters. Neuroradiology10.1007/s00234-020-02542-5 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Burger PC, Mahaley MS, Jr, Dudka L, Vogel FS. The morphologic effects of radiation administered therapeutically for intracranial gliomas. A postmortem study of 25 cases. Cancer. 1979;44:1256–1272. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197910)44:4<1256::AID-CNCR2820440415>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE, Hricak H. Radiomics: Images are more than pictures, they are data. Radiology. 2015;278:563–577. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park YW, et al. Whole-tumor histogram and texture analyses of DTI for evaluation of IDH1-mutation and 1p/19q-codeletion status in world health organization grade II gliomas. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2018;39:693–698. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bae S, et al. Radiomic MRI phenotyping of glioblastoma: Improving survival prediction. Radiology. 2018;289:797–806. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tian Q, et al. Radiomics strategy for glioma grading using texture features from multiparametric MRI. J. Magn. Resonan. Imaging. 2018;48:1518–1528. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park, C. J. et al. Diffusion tensor imaging radiomics in lower-grade glioma: Improving subtyping of isocitrate dehydrogenase mutation status. Neuroradiology, 62(3), 319–326 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Park YW, et al. Radiomics MRI phenotyping with machine learning to predict the grade of lower-grade gliomas: A study focused on nonenhancing tumors. Korean J. Radiol. 2019;20:1381–1389. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2018.0814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyashita M, et al. Evaluation of fluoride-labeled boronophenylalanine-PET imaging for the study of radiation effects in patients with glioblastomas. J. Neurooncol. 2008;89:239. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9621-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chawla NV, Bowyer KW, Hall LO, Kegelmeyer WP. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002;16:321–357. doi: 10.1613/jair.953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dequesada IM, Quisling RG, Yachnis A, Friedman WA. Can standard magnetic resonance imaging reliably distinguish recurrent tumor from radiation necrosis after radiosurgery for brain metastases? A radiographic-pathological study. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:898–904. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000333263.31870.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang H, Ma L, Shu C, Wang Y-B, Dong L-Q. Diagnostic accuracy of diffusion MRI with quantitative ADC measurements in differentiating glioma recurrence from radiation necrosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2015;351:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlemmer H-P, et al. Differentiation of radiation necrosis from tumor progression using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neuroradiology. 2002;44:216–222. doi: 10.1007/s002340100703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehrabian H, Desmond KL, Soliman H, Sahgal A, Stanisz GJ. Differentiation between radiation necrosis and tumor progression using chemical exchange saturation transfer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;23:3667–3675. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-16-2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park JE, et al. Pre- and posttreatment glioma: Comparison of amide proton transfer imaging with MR spectroscopy for biomarkers of tumor proliferation. Radiology. 2016;278:514–523. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015142979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park JE, et al. Amide proton transfer imaging seems to provide higher diagnostic performance in post-treatment high-grade gliomas than methionine positron emission tomography. Eur. Radiol. 2018;28:3285–3295. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, et al. Role of magnetic resonance spectroscopy for the differentiation of recurrent glioma from radiation necrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83:2181–2189. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu LS, et al. Relative cerebral blood volume values to differentiate high-grade glioma recurrence from posttreatment radiation effect: Direct correlation between image-guided tissue histopathology and localized dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging measurements. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2009;30:552–558. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cha J, et al. Analysis of the layering pattern of the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) for differentiation of radiation necrosis from tumour progression. Eur. Radiol. 2013;23:879–886. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2638-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu LS, et al. Reevaluating the imaging definition of tumor progression: Perfusion MRI quantifies recurrent glioblastoma tumor fraction, pseudoprogression, and radiation necrosis to predict survival. Neuro-oncology. 2012;14:919–930. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park YW, et al. Radiomics and machine learning may accurately predict the grade and histological subtype in meningiomas using conventional and diffusion tensor imaging. Eur. Radiol. 2019;29:4068–4076. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5830-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park, Y. W. et al. Radiomics model predicts granulation pattern in growth hormone-secreting pituitary adenomas. Pituitary23(6), 691–700 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Peng L, et al. Distinguishing true progression from radionecrosis after stereotactic radiation therapy for brain metastases with machine learning and radiomics. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2018;102:1236–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Z, et al. A predictive model for distinguishing radiation necrosis from tumour progression after gamma knife radiosurgery based on radiomic features from MR images. Eur. Radiol. 2018;28:2255–2263. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5154-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tiwari P, et al. Computer-extracted texture features to distinguish cerebral radionecrosis from recurrent brain tumors on multiparametric MRI: A feasibility study. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2016;37:2231–2236. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Q, et al. Differentiation of recurrence from radiation necrosis in gliomas based on the radiomics of combinational features and multimodality MRI images. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2019;2019:2893043. doi: 10.1155/2019/2893043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang K, et al. Individualized discrimination of tumor recurrence from radiation necrosis in glioma patients using an integrated radiomics-based model. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2020;47:1400–1411. doi: 10.1007/s00259-019-04604-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ellingson BM, et al. Consensus recommendations for a standardized Brain Tumor Imaging Protocol in clinical trials. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17:1188–1198. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaufmann TJ, et al. Consensus recommendations for a standardized brain tumor imaging protocol for clinical trials in brain metastases. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22:757–772. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noaa030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Punyakanok V, Roth D, Yih W-T, Zimak D. Learning and inference over constrained output. IJCAI. 2005;5:1124–1129. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sinha S, Bastin ME, Whittle IR, Wardlaw JM. Diffusion tensor MR imaging of high-grade cerebral gliomas. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2002;23:520–527. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park, Y. W. et al. Diffusion tensor and postcontrast T1-weighted imaging radiomics to differentiate the epidermal growth factor receptor mutation status of brain metastases from non-small cell lung cancer. Neuroradiology 10.1007/s00234-020-02529-2 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Omuro A, DeAngelis LM. Glioblastoma and other malignant gliomas: A clinical review. JAMA. 2013;310:1842–1850. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Louis DN, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–820. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hopewell, J. et al. In Acute and Long-Term Side-Effects of Radiotherapy 1–16 (Springer, New York, 1993).

- 48.Panth KM, et al. Is there a causal relationship between genetic changes and radiomics-based image features? An in vivo preclinical experiment with doxycycline inducible GADD34 tumor cells. Radiother. Oncol. 2015;116:462–466. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zinn PO, et al. A coclinical radiogenomic validation study: Conserved magnetic resonance radiomic appearance of periostin-expressing glioblastoma in patients and xenograft models. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;24:6288–6299. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-17-3420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nael K, et al. Multiparametric MRI for differentiation of radiation necrosis from recurrent tumor in patients with treated glioblastoma. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2018;210:18–23. doi: 10.2214/ajr.17.18003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blonigen BJ, et al. Irradiated volume as a predictor of brain radionecrosis after linear accelerator stereotactic radiosurgery. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010;77:996–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ruben JD, et al. Cerebral radiation necrosis: Incidence, outcomes, and risk factors with emphasis on radiation parameters and chemotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2006;65:499–508. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takano S, et al. Detection of IDH1 mutation in human gliomas: Comparison of immunohistochemistry and sequencing. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2011;28:115–123. doi: 10.1007/s10014-011-0023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brandes AA, et al. MGMT promoter methylation status can predict the incidence and outcome of pseudoprogression after concomitant radiochemotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:2192–2197. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chenevert TL, et al. Errors in quantitative image analysis due to platform-dependent image scaling. Transl. Oncol. 2014;7:65–71. doi: 10.1593/tlo.13811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Avants BB, Tustison N, Song G. Advanced normalization tools (ANTS) Insight J. 2009;2:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shinohara RT, et al. Statistical normalization techniques for magnetic resonance imaging. NeuroImage Clin. 2014;6:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Griethuysen JJM, et al. Computational radiomics system to decode the radiographic phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e104–e107. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-17-0339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zwanenburg, A., Leger, S., Vallières, M. & Löck, S. Image biomarker standardisation initiative. arXiv preprint arXiiv:1612.07003 (2016).

- 60.Bahrami N, et al. Edge contrast of the FLAIR hyperintense region predicts survival in patients with high-grade gliomas following treatment with bevacizumab. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2018;39:1017–1024. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. doi: 10.2307/2531595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J. R. Stat. Soci. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1996;58:267–288. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.