Abstract

First introduced in 1971, the Fontan procedure is the final common destination for all patients with a functional single ventricle. The procedure itself has evolved tremendously over the last five decades. This review traces this journey and presents the importance, outcomes and future outlook of the procedure in the current era.

Keywords: Fontan, Single ventricle, Univentricular heart

Concept

The Fontan circulation is the common destination pathway for all patients with a functional single ventricle. Presence of only one effective pumping chamber necessitates that this chamber is used for the systemic circulation. Consequently, the pulmonary circulation is left without a pumping chamber. Thus, lack of a subpulmonary ventricle is the essence of the Fontan circulation. In this review, we discuss the evolution of this circulation, selection criteria, pathophysiology and long-term fate of this unphysiological circuit.

Origin and evolution

The Fontan operation was introduced into the clinical arena in 1971 when Francis Fontan and Eugene Baudet published a landmark article titled ‘surgical repair of tricuspid atresia’ [1]. However, this achievement was preceded by the work of several others who laid the foundation of the Fontan operation [2, 3] (Fig. 1). In 1943, Starr et al. demonstrated that destruction of the right ventricular wall with diathermy did not result in significant venous hypertension in dogs [4]. Rodbard and Wagner in 1949 showed that the right ventricle (RV) can be bypassed in humans [5]. They did this by anastomosing the right atrial appendage (RAA) to the main pulmonary artery and showed that once the right atrium (RA) is sufficiently pressurised, there is antegrade flow into the main pulmonary artery (MPA) [3]. Similarly, Warden et al. in 1954 [6] performed staged operations. They first created tricuspid stenosis to produce right atrial enlargement and hypertrophy and then anastomosed the RAA to the pulmonary artery [6]. They rightly predicted that this could be the potential treatment for tricuspid atresia. Also, an essential component of the Fontan procedure was the classic Glenn procedure introduced in 1958 by Glenn [7]. The paper includes a very elaborate description of an off-bypass end-to-side anastomosis between the right pulmonary artery (RPA) with the superior vena cava (SVC) through a right thoracotomy in a 7-year-old boy with single ventricle physiology, transposition of the great arteries and pulmonary stenosis. The SVC-RA junction was only ligated. The paper led to important insights into the potential indications and sequalae of the operation.

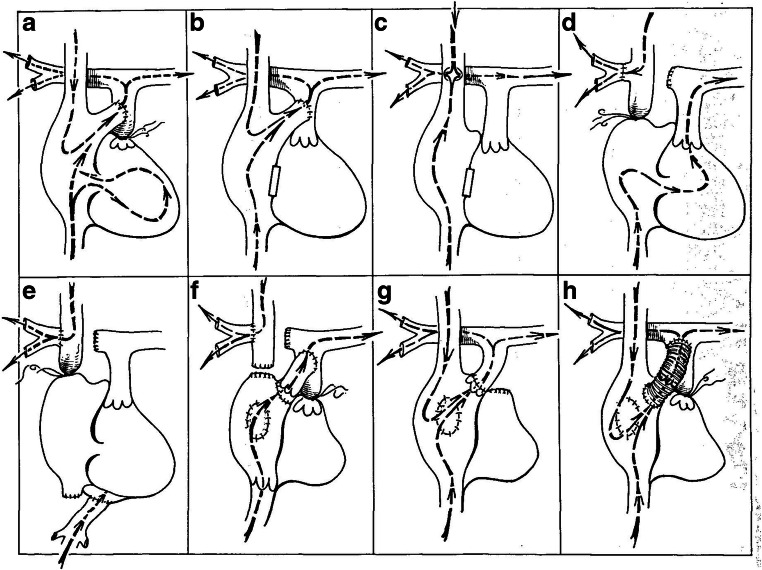

Fig. 1.

Early attempts at Fontan: a Rodbard and Wagener ligated the main pulmonary artery and anastomosed the right atrial appendage to the distal pulmonary artery. b Warden, DeWall and Varco did the same procedure but ligated the tricuspid instead of the pulmonary valve. c Haller and co-workers ligated the tricuspid valve and anastomosed the superior vena cava to the right pulmonary artery, side to side. d Carlon, Mondini and De Marchi ligated the cavoatrial junction and sutured the cut distal end of the right pulmonary artery to the caval origin of the azygous vein. This was essentially the same operation but introduced clinically by Glenn. e Robiscek and associates bypassed the entire right heart by doing a cavopulmonary shunt and connecting the inferior vena cava to the left atrium. f Fontan and co-workers corrected tricuspid atresia by constructing a cavopulmonary shunt, inserting an allograft valve in the inferior vena cava, interposing an allograft valve between the right atrial appendage and the pulmonary artery, closing the atrial septal defect and ligating the proximal main pulmonary artery. g Kreutzer and co-workers disinserted the intact pulmonary annulus and valve from the right ventricle, reinserted it into the right atrial appendage and closed the atrial septal defect. h In one of our patients, a Dacron tube containing a porcine aortic valve xenograft was interposed between the right atrium and the main pulmonary artery, the pulmonary artery was ligated and the atrial septal defect was closed. This patient did extremely well, is acyanotic and has normal exercise tolerance (reproduced with permission from Sade and Castaneda [2])

It was only after a decade that the Fontan operation was brought into reality. The paper by Fontan and Baudet described the surgical treatment of three patients of tricuspid atresia [1]. As mentioned in the paper ‘A new surgical procedure has been used which transmits the whole vena caval blood to the lungs, while only oxygenated blood returns to the left heart. The right atrium is, in this way, 'ventriclized', to direct the inferior vena caval blood to the left lung, the right pulmonary artery receiving the superior vena caval blood through a cava-pulmonary anastomosis’ [1]. The operation consisted of a classic Glenn where the SVC was anastomosed to the divided distal RPA and the RA was anastomosed to the left pulmonary artery (LPA) with an interposed valved homograft. In addition, another valved homograft was inserted at the inferior vena cava (IVC)-RA junction (to prevent backflow of blood) and the MPA was ligated (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the atrial septal defect was closed (which was thought to be appropriate as the left ventricle was systemic). Two of the three patients survived, and one patient expired in the immediate post-operative period. At autopsy, this patient had vegetations and perforation on the mitral valve, which was believed to be the cause of death.

Fig. 2.

Original Fontan operation: the superior vena cava is anastomosed to the divided distal right pulmonary artery (classic Glenn); the right atrium is anastomosed to the left pulmonary artery with an interposed valved homograft. In addition, another valved homograft is inserted at the inferior vena cava—right atrial junction (to prevent backflow of blood) and the main pulmonary artery is ligated (reproduced with permission from Fontan and Baudet [1])

Around the same time (1973), Kreutzer et al. independently (and oblivious to Fontan and Baudet’s work) reported their own surgical treatment for tricuspid atresia (Fig. 3) [8]. A homograft was placed between the RA and the MPA. Unlike Fontan and Baudet’s description, a Glenn connection was not created and a valve was not placed in the IVC. They also left an opening in the atrial septum.

Fig. 3.

Kreutzer’s modification of Fontan: schematic representation of atriopulmonary Fontan performed by Kreutzer (reproduced with permission from Kreutzer et al. [8])

The originally described Fontan procedure underwent several initial refinements and modifications [3]. The initial procedures focused on surgical treatment of tricuspid atresia. Bowman et al. used valved conduits to establish continuity between the RA to RV [3]. To circumvent the problem of non-growing conduits, Bjork et al. described anastomosis of the RAA with the RV augmented with a pericardial patch [3].

Another modification was ‘neo-septation’ of the atrium using a right atrial flap [9]. This technique was proposed to be useful then for hearts with a dominant left and diminutive right ventricle associated with either a common atrioventricular valve or left atrioventricular valve atresia [9]. In this technique, the RA was opened with a longitudinal incision, the atrial septum was resected, and the coronary sinus was cut back. The upper wall of the right atrial incision was sutured in such a way that the pulmonary venous atrium drains into the dominant ventricle via the right-sided or common atrioventricular valve. This was followed by reconstructing the atrium and an atriopulmonary connection.

Modifications

Since its inception, the original Fontan operation has undergone many modifications to achieve haemodynamics, optimise the energy losses and reduce potential complications (Table 1). The first significant modification of the Fontan operation was introduction of the lateral tunnel (LT) technique. This technique was introduced in the same year (1988) by De Leval et al. from England and Jonas and Castaneda from Boston Children’s Hospital (Fig. 4) [11, 12]. It essentially consists of an intra-atrial baffle to direct IVC blood to the anastomosis of the RA and RPA. De Leval’s work was based on hydrodynamic studies and the tunnel was created to streamline the systemic venous flow into the pulmonary arteries using an intra-atrial baffle [11]. Jonas and Castaneda’s work was based on an attempt to use the Fontan operation for lesions other than tricuspid atresia [12]. We have previously described a technique of creation of LT Fontan using autologous tissue (Fig. 5) [17]. The interatrial septum was used to create the inner half of the atrial tunnel while the outer half was formed by the RA free wall. This technique was utilised in 17 patients with one early and one late death. All surviving patients had sinus rhythm.

Table 1.

Evolution and modifications of the Fontan operation

| Author | Year | Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Starr et al. [4] | 1943 | Showed that destruction of right ventricle in dogs did not result in venous hypertension |

| Rodbard and Wagner [5] | 1949 | Showed that right ventricle can be bypassed in humans |

| Warden et al. [6] | 1954 | Staged procedure-created tricuspid stenosis followed by atriopulmonary anastomosis |

| Glenn [7] | 1958 | Described classic the Glenn operation |

| Fontan and Baudet [1] | 1971 | Described the first Fontan operation |

| Kreutzer et al. [8] | 1973 | Independently described the Fontan operation in Argentina |

| Bowman et al. [3] | 1978 | Valved conduit between RA and RV |

| Bjork et al. [3] | 1979 | Anastomosis of RAA with RV with pericardial augmentation |

| Vargas et al. [10] | 1987 | Intra-extra-cardiac conduit Fontan |

|

De Leval et al. [11] Jonas and Castaneda [12] |

1988 | Lateral tunnel Fontan |

| Marcelletti et al. [13] | 1990 | Extra-cardiac conduit Fontan |

| Bridges et al. [14] | 1990 | Introduced Fontan fenestration |

| Hvass et al. [15] | 1992 | Autologous pericardial tube for extra-cardiac conduit |

| Sarioglu et al. [9] | 1994 | Neo-septation of the atrium using right atrial flap |

| Hausdorf et al. [16] | 1996 | Trans-catheter completion of Fontan |

| Airan et al. [17] | 2000 | Lateral tunnel Fontan using autologous tissue |

| Soerensen et al. [18] | 2007 | Bifurcated Y-graft |

Abbreviations: RA, right atrium; RAA, right atrial appendage; RV, right ventricle

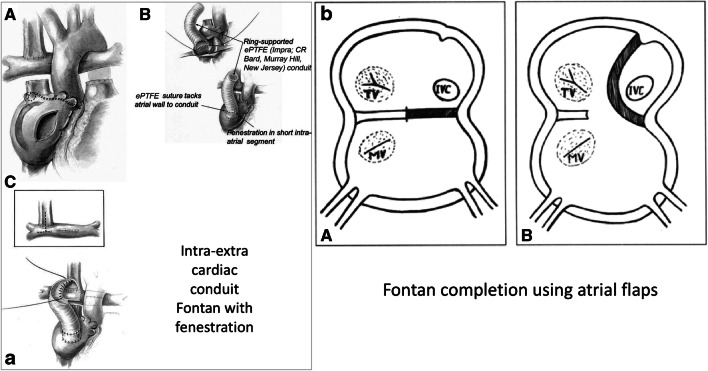

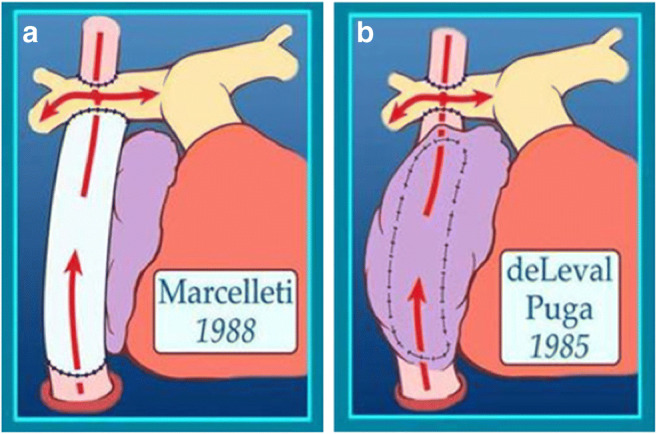

Fig. 4.

Modifications of Fontan: a lateral tunnel Fontan and b extra-cardiac conduit Fontan (reproduced with permission from Backer et al. [19])

Fig. 5a.

A Modifications of Fontan—left, intra/extracardiac conduit incorporates an atrial incision that avoids injury to the sinus node, the sinus node artery and the crista terminalis. B A ring-supported expanded polytertrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) conduit is sutured to the internal orifice of the inferior vena cava. The short intra-atrial segment is fenestrated. A ePTFE suture tacks the atrial wall to the external surface of the conduit. C The bevelled distal anastomosis of the intra/extracardiac conduit is usually fashioned to an inverted T incision that crosses the bidirectional Glenn anastomosis with extensions into the proximal and distal right pulmonary artery (reproduced with permission from Jonas [10]). b Fontan using atrial flaps: diagrammatic representation of the procedure showing the extent of the septal flap A and the completed procedure with flap sutured in front of sulcus terminalis B. (MV, mitral valve; IVC, inferior vena cava; TV, tricuspid valve) (reproduced with permission from Airan et al. [17])

The extra-cardiac conduit (ECC) Fontan was introduced by Marcelletti et al. in 1990 (Fig. 4) [13]. This technique uses an artificial conduit which connects the divided IVC and underside of the Glenn anastomosis. Though the ECC is the most popular Fontan technique at present, many institutes around the world still prefer the LT Fontan. The intra-extra-cardiac (IE) modification is another option for Fontan completion (Fig. 5). Few centres practise this as the preferred Fontan technique [10]. This technique involves suturing of a ringed conduit through an atrial incision to the IVC orifice and remaining part of the conduit emerges from the RA and is anastomosed to the underside of the Glenn. In 2013, Sinha et al. showed that this modification can have significantly lower rate of arrhythmias in the short and intermediate term as compared with the LT Fontan [20]. Besides, this modification has been proposed to combine the advantages of the LT (ease of takedown and fenestration) and hemodynamic superiority of the ECC.

A variety of conduit materials have been used for the extra-cardiac conduit Fontan. Use of an autologous pericardial tube for an ECC Fontan was introduced by Hvass et al. in 1992 and reintroduced by Gundry et al. in 1997 [15, 21]. Gundry et al. used in situ pedicled pericardium to create a ‘growing’ Fontan [21]. Similarly, in 1998, Okabe et al. described use of an autologous pedicled pericardial roll for the creation of an extra-cardiac conduit [22]. The retention of the pedicle retains the blood supply and therefore is believed to retain the growth potential of the conduit. An evaluation of outcomes of this technique by Hasaniya et al. in 2010 suggests that this technique is safe and durable [23]. This technique was found to be comparable with the synthetic/allograft ECC Fontan in a report by Woods et al. in 2003 [24]. The Fontan procedure has also been performed without the use of cardiopulmonary bypass [25–27]. Shikata et al. have demonstrated that such an approach reduces the duration of post-Fontan pleural and pericardial effusions [25]. Mainwaring et al. have published a series of 52 patients where all three stages of single ventricle palliation have been performed without using cardiopulmonary bypass [27]. This approach allowed them to avoid blood transfusion in 80% of the patients. We have previously described a completely autologous Fontan by mobilising and anastomosing the IVC directly to the MPA without using cardiopulmonary bypass in a patient with suitable anatomy [28].

The concept of Fontan fenestration was introduced by Bridges et al. from Boston to ameliorate the short-term deleterious effects of Fontan physiology to some extent [14]. The fenestration was initially introduced as a ‘pop-off’ valve in high-risk patients [14]. They identified the following risk factors: mean pulmonary artery pressure of 18 mmHg or more, ventricular end-diastolic pressure of 12 mmHg or more, atrioventricular valvar regurgitation, pulmonary artery distortion, pulmonary vascular resistance of 2 Woods’ units or more, systemic ventricular outflow obstruction and complex anatomy and recommended performing fenestration in such patients. They also described feasibility of fenestration closure after trans-catheter test occlusion. A small amount of right-to-left shunting through the fenestration allowed decrease in systemic venous pressure and at the same time improved cardiac output by providing ventricular preload. However, this came at the cost of systemic desaturation as the blood flowing through the fenestration does not pass through the lungs. Creating a fenestration also helped decrease the duration of pleural drainage and length of hospital stay [29]. However, there is data in the literature which shows that fenestration might be of limited benefit [30, 31]. In 1999, Thompson et al. from Stanford reported that routine Fontan fenestration is not essential and recommended it for Fontan pressures ≥ 18 mmHg and trans-pulmonary gradient of ≥ 10 [32]. On the other hand, we reported our experience with Fontan fenestrations in 2000 [33]. We found that absence of Fontan fenestration was the only and strongest predictor of Fontan failure in 348 patients undergoing the Fontan operation. In our institute, our policy is to fenestrate all LT and IE Fontans. For ECC Fontan we tend to be more selective. In the current era, Fontan fenestration is routinely performed for high-risk patients with unfavourable hemodynamics but remains a subjective choice for low-risk Fontans. However, there has been a growing realisation that arrhythmias that develop with increasing follow-up in these patients may need electrophysiologic mapping and intervention. Presence of a fenestration is useful in these patients to get access to the common venous atrium that receives all pulmonary venous return.

In 1996, Hausdorf et al. described trans-catheter completion of Fontan after preparation at the time of Hemi-Fontan in order to combine the advantages of baffle fenestration and of a staged univentricular repair, but eliminating need of an additional surgery [16]. The procedure consists of insertion of a subtotal polypropylene band around the cavoatrial junction and insertion of a multi-perforated polytetrafluoroethylene patch baffle laterally in the atrium at the time of hemi-Fontan. This was followed by insertion of a trans-catheter stent to complete the Fontan. In 2004, Galantowicz and Cheatham described their initial experience with trans-catheter Fontan completion in five patients after a previous hemi-Fontan operation [34]. Konstantinov et al. in 2004 and Metton et al. in 2011 described animal models of trans-catheter Fontan completion [35, 36]. Despite these strategies, trans-catheter Fontan completion is not currently considered the standard of care in patients destined to have the final Fontan palliation.

There is growing realisation that optimisation of flow within the Fontan circuit will improve hemodynamics and potentially translate into better long-term outcomes [37]. The team from Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and Georgia Institute of Technology have patented the development of bifurcated Y-graft for Fontan completion based on computational fluid dynamic studies [37].

Fontan physiology and the Fontan paradox

The Fontan circulation is inherently non-physiological. The fact that such a circulation has not existed in the animal kingdom through millions of years of evolution is testimony to the non-physiological nature of the circuit. The lack of a subpulmonary ventricle leads to the creation of a neo-portal system [38]. Therefore the lungs add significant resistance to the circuit leading to upstream systemic venous congestion and downstream low output [38].

The concept of ‘Fontan paradox’ is vital to the understanding of the Fontan circulation. The Fontan paradox has been eloquently described by Rychik in 2016 [39]. Normal central venous pressure is 2 to 6 mmHg. This is because the subpulmonary ventricle is actively pumping blood forward and preventing stasis of systemic venous blood. Negative intrathoracic pressure helps in augmenting venous return and peripheral muscle contraction has a negligible impact. However, in a Fontan circulation, there is no subpulmonary ventricle to augment forward flow. Consequently, there is relative stasis of systemic venous blood. The magnitude of venous congestion is almost up to three times the normal. Factors like negative intrathoracic pressure and peripheral muscle contraction become exceedingly important in augmenting the passive venous inflow. Though physiologically abnormal, this state of systemic venous hypertension is the only pressure head to drive the Fontan circuit and therefore the cardiac output. Herein lies the Fontan paradox—good systemic cardiac output can be achieved only at the cost of higher Fontan pressures and systemic venous congestion and the ideal Fontan is actually the ‘failing Fontan’ [40]. Hence, even in a ‘normal’ Fontan this altered physiology takes its toll and several organ systems in the body bear the brunt. Also, there is a limit to augment cardiac output as venous return is passive and hence exercise capacity is limited.

Patient selection

All patients with a single functional ventricle are candidates for a Fontan circulation. This can include patients where there is only one ventricle and the other is diminutive. Or it can include patients with two adequate sized ventricles but where biventricular septation is not possible for morphological or technical reasons [41]. The latter is a relative indication, and the current knowledge of the long-term morbidity that entails committing a patient to the univentricular pathway often justifies extensive efforts to achieve a biventricular circulation even at the cost of complex reconstructions and multiple reoperations.

Traditionally, patient selection was guided by the ‘ten commandments’ described by Choussat et al. in 1978 (Table 2) [42]. In the current era, patients going down the single ventricle (Fontan) pathway are optimised for a future Fontan operation right from birth. This includes optimisation of pulmonary blood flow, early repair of atrioventricular valves and preservation of ventricular function. This pre-Fontan optimisation, accumulating surgical experience and refinement of surgical techniques has allowed modification of the ten commandments [31]. This has also allowed utilisation of the Fontan pathway for a larger patient population. In the current era, however, two pre-Fontan criteria still remain important—pulmonary artery pressures and systemic ventricular function [31]. With regards to the timing of the Fontan operation, there are two schools of thought. One view is that the Fontan operation should be completed as soon as possible to prevent deleterious effects of long-standing cyanosis on the body. The other school of thought suggests that Fontan completion should be delayed as far as possible as we ‘turn on’ the ‘Fontan clock’; subjecting the body to chronic systemic venous hypertension.

Table 2.

Original ten commandments for the Fontan operation described by Choussat et al. [42]

| Original ‘10 commandments for the Fontan operation’ | |

|---|---|

| Age < 4 years | |

| Normal sinus rhythm | |

| Normal systemic venous drainage | |

| Normal right atrial volume | |

| Mean PAP ≤ 15 mmHg | |

| PVR ≤ 4 units/m2 | |

| Ratio of PA diameter to aortic diameter ≥ 0.75 | |

| Normal ventricular function (ejection fraction > 0.6) | |

| No mitral insufficiency | |

| No impairing effect of previous shunt |

Abbreviations: PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance

In 1985, Hopkins et al. described the utility of staging the Fontan procedure and showed the utility of bidirectional cavopulmonary shunt (Glenn) prior to the Fontan [43]. Also, in 1992, Norwood and Jacobs reported data to suggest that performing a single-stage Fontan results in sudden change in the hemodynamics and adversely alters the ventricular diastolic function [44]. They showed that staging the Fontan improved outcomes. Jacobs and Norwood further presented a series of 100 consecutive staged Fontan’s without any deaths [45]. In their patients, staging was an intermediate Hemi-Fontan operation. In the current era, staged single ventricle (Fontan) palliation is the standard of care.

Stage 1 procedures are usually performed in the neonatal age group. These include optimisation of pulmonary blood flow—either by restricting it (pulmonary artery band) or augmenting it (systemic to pulmonary artery shunt). If there is systemic ventricular outflow tract obstruction, as in the hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) subgroup, aorto-pulmonary amalgamation (Damus-Kaye-Stansel anastomosis) along with arch augmentation or the typical Norwood operation is performed. In the heterotaxy subgroup, obstructed anomalous pulmonary venous return is also addressed. Though repair of regurgitant atrioventricular valves is not performed at this stage, it may be undertaken if it is significant enough to preclude future single ventricle palliation [46]. Stage II single ventricle palliation, usually performed between 3 to 6 months of age includes redirection of SVC blood directly to the pulmonary arteries. This can be achieved either by a bidirectional superior cavopulmonary anastomosis (bidirectional Glenn (BDG)) or the Hemi-Fontan operation. The Stage II operation is an excellent opportunity to optimise the future Fontan pathway [47, 48]. This includes, repair of atrioventricular valves, augmentation of pulmonary arteries and ensuring adequate mixing by an atrial septectomy. Casella et al. from Boston have described the concept of ‘super Glenn’ where there is targeted augmentation of pulmonary blood flow to unilateral hypoplastic pulmonary arteries by addition of a small shunt on that side and restricting the connection to the pulmonary artery supplied by the SVC [49].

Stage III is the actual Fontan operation which can be performed using any of the techniques described above. Though the optimum age of the Fontan is believed to be 3 to 5 years, many institutes around the world perform these operations at an earlier age as a routine [50].

Though staging of the Fontan pathway is popular, there is data in the literature to suggest that in low-risk patients with favourable hemodynamics, single-stage Fontan can be performed with acceptable outcomes [51]. However, many studies have documented increased morbidity with a primary Fontan because the sudden redirection of blood to the pulmonary circulation translates into prolonged pleural effusions. In addition, sudden reduction of preload to a single ventricle may precipitate severe ventricular dysfunction. Notwithstanding these, in a few naturally selected patients, who survive into adulthood, we have shown that a primary Fontan can be offered to carefully selected patients beyond the first decade of life with acceptable outcomes [52]. This strategy is particularly useful in developing countries where costs of multiple operations are prohibitive, and many patients are unlikely return for a Fontan completion after a previous Glenn [40].

Outcomes of the Fontan operation

In the current era, with careful patient selection and pre-Fontan optimisation, outcomes of the Fontan procedure are excellent. In 2017, Malec et al. reported no mortality in 248 consecutive Fontan operations [53]. d’Udekem et al. summarised their experience with 1089 Fontan operations in 2014 [54]. Survival after the Fontan operation was 90% at 20 years after the LT Fontan and 97% at 13 years after ECC (Fig. 6). They found that an atriopulmonary Fontan was a predictor of poor survival and HLHS was a predictor of Fontan failure. Pundi et al. reported their experience with 1052 Fontan operations in 2015 [55]. After 2001, the 10-year survival after Fontan was 95% (Fig. 6). They found that predictors of poor surgical outcomes were pre-operative diuretic use, longer cardiopulmonary bypass time, operation prior to 1991, atrioventricular valve (AVV) replacement at the time of Fontan operation, elevated post-bypass Fontan (> 20 mmHg) or left atrial (> 13 mmHg) pressures, prolonged chest tube drainage (> 21 days), post-operative ventricular arrhythmias, renal insufficiency and development of protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) [55]. Downing et al. from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia reported their experience with 773 Fontan operations in 2017 [56]. Freedom from a composite end point of Fontan takedown, transplant and death at 15 years was 85%. However, all these papers also reveal that there is a predictable long-term attrition post-Fontan. In 2018, Schwartz et al. reported the results of a meta-analysis where they evaluated 5859 Fontan operations from 19 papers [57]. They found that era of surgery, proportion of atriopulmonary connections and older age at Fontan were associated with higher rates of death, but ventricular morphology was not. In the comparison between LT and ECC Fontan (Table 3), there is conflicting evidence in the literature as to which Fontan technique is better [19, 58–60]. In 2019, Sinha et al. reported a comparison of 43 IE Fontan operations with 38 ECC Fontan operations and found that an IE Fontan was associated with shorter duration of pleural effusions and hospital stay [61].

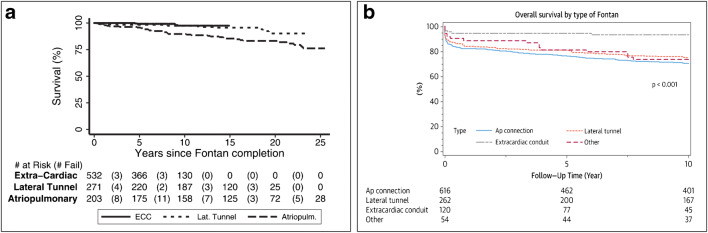

Fig. 6.

Fontan survival in the current era: a Kaplan–Meier survival by Fontan type. Survival was 76% (95% confidence interval (CI), 67–83%) at 25 years for atriopulmonary Fontan, 90% (95% CI, 81–95%) at 20 years for LT and 97% (95% CI, 94–99%) at 13 years for ECC (reproduced with permission from d’Udekem et al. [54]) and b ten-year survial was 70% for atriopulmonary Fontans, 75% for LT and 94% for ECC (reproduced wuith permission from Pundi et al. [55])

Table 3.

Comparison of lateral tunnel and extra-cardiac conduit Fontan

| Lateral tunnel Fontan | Extra-cardiac conduit Fontan | |

|---|---|---|

| Construct | Intra-atrial baffle | Conduit outside atrium |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass | Cardiopulmonary bypass essential | Cardiopulmonary bypass not essential |

| Aortic cross clamp | Aortic cross clamp essential | Aortic cross clamp not essential |

| Arrhythmias | More arrhythmogenic due to right atrial suture lines | Less arrhythmogenic |

| Thrombogenicity | Risk of atrial thrombus | Risk of graft thrombus |

| Growth potential | Growth potential + | No growth potential |

| Hemodynamics | More favourable hemodynamics? | Less favourable hemodynamics |

| Anatomical limitations | Less limited by abnormal anatomy | Limited by abnormal anatomy |

It is traditionally believed that patients with two good-sized ventricles who have a Fontan have better outcomes compared with patients undergoing Fontan for the classical ‘single ventricle’. However, a recent report from Australia-New Zealand shows that there is no difference in outcomes between the two groups [62].

Early Fontan failure

Fontan failure can manifest early or late. Early failure presents immediately or early after the Fontan. Early Fontan failure is described as the post-operative state of low systemic perfusion, high Fontan pressures and large volume requirements, which is unresponsive to inotropes and has high mortality [63]. The causes of early Fontan failure can be unfavourable Fontan hemodynamics like high pulmonary artery pressures, atrioventricular valve regurgitation or ventricular dysfunction. It can also be caused by technical issues with the Fontan circuit like distortion/compression of the conduit or pulmonary arteries.

Early Fontan failure can be managed by taking down the Fontan circulation to an intermediate circulation (Glenn/shunt physiology) [64, 65]. Almond et al. from Boston have reported the largest Fontan takedown series till date [64]. They reported 53 Fontan takedowns over 27 years. Mortality after takedown was 45%. Nineteen of the fifty-three patients had a successful re-Fontan. In patients who are poor Fontan completion candidates and have a functioning Glenn shunt, creation of an arterio-venous fistula may be the only option. This has been described as anastomosis of the common carotid artery to the internal jugular vein or axillary artery and vein [66, 67]. The sole purpose of this approach is to increase systemic saturation and buy time. This can be used as a bridge to decision or bridge to transplant. These patients still can be reconsidered for a re-Fontan [64].

Late Fontan failure

As survival for the Fontan operation improves, a large population is now moving into adulthood with a Fontan circulation [68]. Projections from the Australia-New Zealand Fontan Registry predict that this population will double in the next 20 years [69]. Long-term Fontan failure manifests in a variety of ways like arrhythmias, prolonged pleural effusions, plastic bronchitis, protein-losing enteropathy amongst others (Fig. 7) [39, 71]. The long-term impact of chronic venous hypertension on other body systems is becoming apparent. Being upstream from the site of venous congestion, the abdominal organs are affected the most. All patients undergoing the Fontan operation have Fontan-associated liver disease (FALD) ranging from fibrosis to cirrhosis while fibrosis is a universal feature [39]. Hepatic venous congestion is believed to induce fibroblastic transformation resulting in progressive hepatic fibrosis with additive risk of ischemia. Neoplastic transformation has also been reported [39]. The synthetic function of the liver might be lost late in the process of cirrhotic transformation. Ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging based elastography is a useful technique to serially evaluate hepatic fibrosis [39].

Fig. 7.

Multiorgan dysfunction later after Fontan operation (reproduced with permission from Book et al. [70])

PLE which is loss of proteins into the gut lumina can occur at any time after the Fontan [39]. There is often no correlation with hemodynamic data and patients with a seemingly well-functioning Fontan circuit also develop PLE. Proteinaceous material is exuded into the airways and leads to cast formation in the form of plastic bronchitis (PB). As the protein transit through the gut lumen is high, the magnitude of loss of proteins in PLE is high with disastrous consequences [39]. PLE and PB together is called ‘endoluminal protein loss syndromes’ with complex etiopathogenesis involving venous and consequently lymphatic hypertension along with impaired tissue perfusion and inflammation [39].

Patients undergoing the Fontan operation also develop arrhythmias in the long term, Carins et al. reported that after 20 years post-Fontan, freedom from arrhythmias is only 60% [72]. Also, development of any arrhythmia (tachy/brady arrhythmia) is a predictor of Fontan failure.

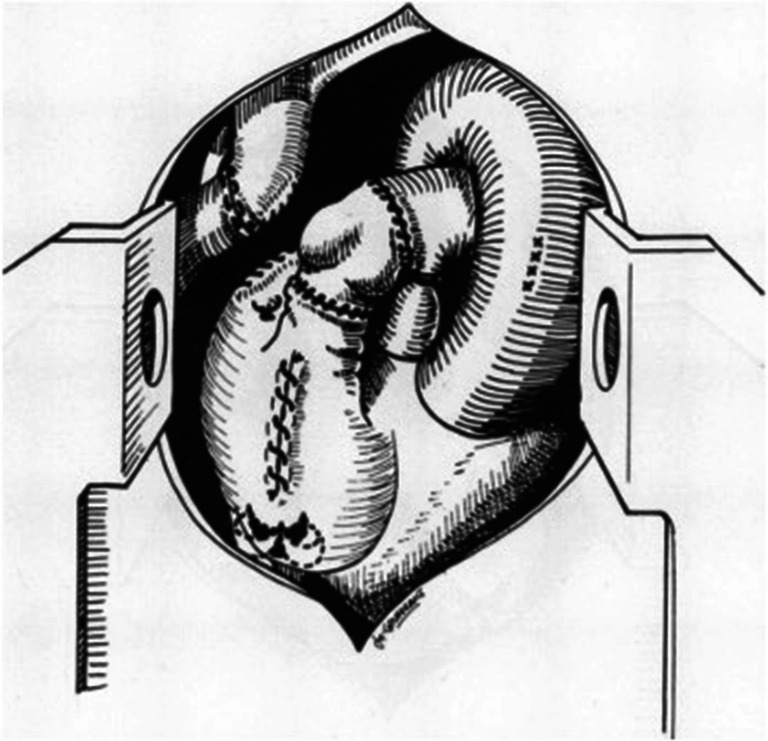

Management of chronic Fontan failure needs a multi-pronged approach. A limited patient population who had undergone the atriopulmonary Fontan and presents with intractable arrhythmias can be managed with Fontan conversion [73]. Mavroudis et al. from Chicago have been the pioneers of this technique [73]. The procedure consists of conversion of atriopulmonary Fontan to ECC Fontan, arrhythmia surgery and implantation of permanent pacemaker (Fig. 8). They also published the largest experience till date of 111 Fontan conversions in 2011 and found the technique to be safe and efficacious [73].

Fig. 8.

Fontan conversion (reproduced with permission from Backer et al. [74])

Pharmacological manipulation of pulmonary vascular resistance using Sildenafil has been shown to improve exercise capacity in patients undergoing the Fontan operations and may be used in the failing Fontan population [75]. In addition, endothelin receptor antagonists like Bosentan and prostaglandins like ilioprost are also known to increase exercise capacity in patients following the Fontan operation [75]. Fontan takedown remains an option for late Fontan failure as well. In this precarious patient population, trans-catheter Fontan takedown is also feasible [76].

Transplant remains an option for patients with an intractable failing Fontan circulation [77]. These patients who undergo transplants present unique challenges like aberrant and complex anatomy, redo procedures increasing cardiopulmonary bypass time and existing post-Fontan end-organ damage. In addition, they have elevated panel reactive antibody, hepatic dysfunction, coagulopathy, PLE and poor nutrition [78]. In 2013, Backer et al. from Chicago reported their experience with post-Fontan transplants [78]. They found that mortality was high (23%) consistent with other series. They also found that infection was the main cause of early deaths and transplant helped in resolution of PLE and PB. Shi et al. from Australia-New Zealand reported their experience with 34 post-Fontan transplants [77]. They found that post heart transplant survival for Fontan patients was 71% at 10 years [77].

Fontan complications in a normally functioning Fontan

Even in seemingly normally functioning Fontans, long term sequalae are inevitable. Long-term sequalae seen in long-term Fontan survivors include exercise intolerance, thromboembolism, delayed somatic growth and development, delayed pubertal development, renal dysfunction, venous insufficiency, varicose veins and neurocognitive deficits [79].

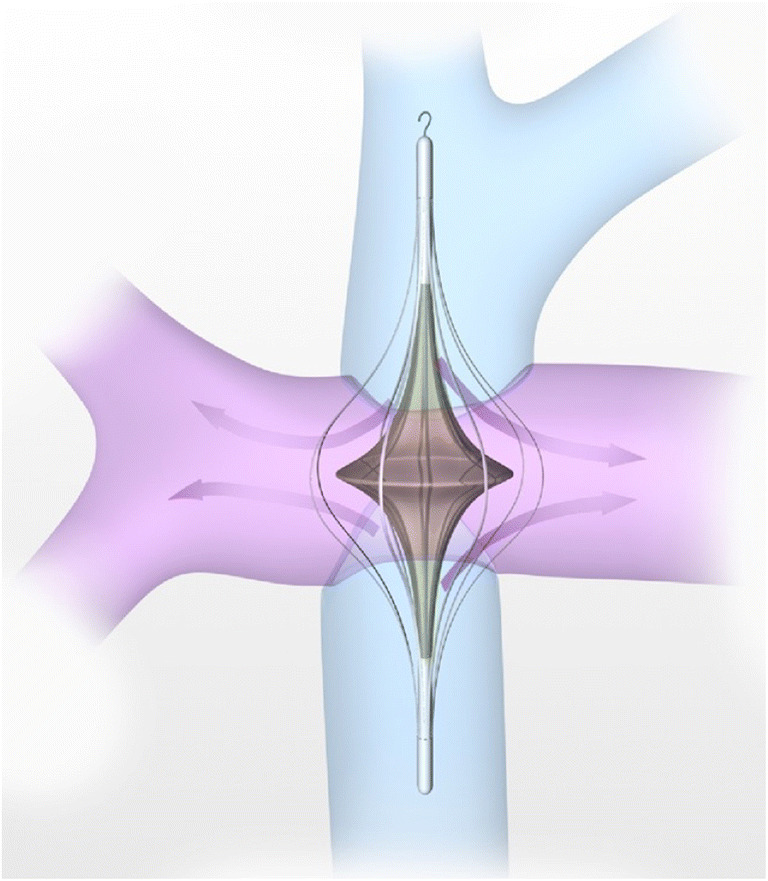

Assist devices

A variety of creative solutions have been attempted over the years to create a sub pulmonary power source to augment the Fontan circulation [80]. Significant work by Rodefeld et al. shows that a boost of only 2–6 mmHg in the Fontan circulation is enough to restore a biventricular circulation and possibly ameliorate the harmful Fontan effects. The same group also developed an animal model of a percutaneous ‘cavopulmonary assist device’ to augment the Fontan circulation which is based in the von Karman viscous pump principle (Fig. 9) [82]. As described by Rodefeld et al., ‘a relatively simple, single, bi-conical impeller with surface vanes positioned in the midst of the total cavopulmonary connection (TCPC) junction will draw venous inflow from two opposing directions, and propel outflow radially in the diametrically opposed pulmonary arteries, simultaneously augmenting flow in all four axes of the TCPC’ [81]. It is believed that the impeller converts the colliding Fontan flows to a simpler flow pattern. The device is also not obstructive. It simulates right ventricular hemodynamics by providing low-pressure, high-volume flows.

Fig. 9.

Cavopulmonary assist device (reproduced with permission from Rodefeld et al. [81])

Several groups have attempted to use ventricular assist devices to augment the Fontan circulation [80]. Derk et al. from University of California, Los Angles have reported use of the Jarvik 2000 ventricular assist device (VAD) to power the Fontan circuit in an animal model [83]. They found that use of the device restored normal hemodynamics and cardiac output. They think that VADs can be used to rescue a failing Fontan as a bridge to transplant or recovery [83]. Lin et al. from Toronto have reported a computational fluid dynamic simulation model of a multi-lumen cannula powered by an external pump to assist the Fontan circuit and found the concept promising [84]. However, as of now, a practical mechanical device to assist the Fontan circulation is not commercially available. Tissue engineering and stem cell technology might be a practical solution in the future to assist the Fontan circulation [80]. Biermann et al. developed an animal model of a tissue engineered contractile Fontan conduit [85]. Engineered, contractile heart tissue constructs were implanted around the right superior vena cava in rats. After killing the animals, it was shown that these constructs remained viable and contractile for extended periods of time after implantation.

Conclusion

Though far from perfect, the Fontan circulation is the only surgical solution for patients with a functional single ventricle. As this patient population grows and long-term consequences become evident, we will have more insights into Fontan physiology. Early optimisation of patients undergoing the Fontan operation in future patients might prolong survival and postpone complications. Mechanical devices and tissue engineering may hold a promising future in these challenging groups of patients.

Funding information

The study did not receive any funding.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of human rights/ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this study, formal ethics committee clearance was not required.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fontan F, Baudet E. Surgical repair of tricuspid atresia. Thorax. 1971;26:240–248. doi: 10.1136/thx.26.3.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sade RM, Castaneda AR. The dispensable right ventricle. Surgery. 1975;77:624–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowgill LD. The Fontan procedure: a historical review. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;51:1026–1030. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(91)91044-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Starr I, Jeffers WA, Meade RH. The absence of conspicuous increments of venous pressure after severe damage to the right ventricle of the dog, with a discussion of the relation between clinical congestive failure and heart disease. Am Heart J. 1943;26:291–301. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodbard S, Wagner D. By-passing the right ventricle. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1949;71:69. doi: 10.3181/00379727-71-17082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warden HE, De Wall RA, Varco RL. Use of the right auricle as a pump for the pulmonary circuit. Surg Forum. 1954;5:16–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glenn WW. Circulatory bypass of the right side of the heart. IV.shunt between superior vena cava and distal right pulmonary artery; report of clinical application. N Engl J Med. 1958;259:117–120. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195807172590304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreutzer G, Galíndez E, Bono H, De Palma C, Laura JP. An operation for the correction of tricuspid atresia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1973;66:613–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarioglu T, Paker T, Türkoglu H, et al. The modified Fontan operation in hearts associated with atrioventricular valvar atresia or common atrioventricular valve—neoseptation of the atriums using a right atrial flap. Cardiol Young. 1994;4:353–357. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonas RA. The intra/extracardiac conduit fenestrated Fontan. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2011;14:11–18. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Leval MR, Kilner P, Gewillig M, Bull C. Total cavopulmonary connection: a logical alternative to atriopulmonary connection for complex Fontan operations. Experimental studies and early clinical experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1988;96:682–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jonas RA, Castaneda AR. Modified Fontan procedure: atrial baffle and systemic venous to pulmonary artery anastomotic techniques. J Card Surg. 1988;3:91–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.1988.tb00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcelletti C, Corno A, Giannico S, Marino B. Inferior vena cava-pulmonary artery extracardiac conduit. A new form of right heart bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1990;100:228–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bridges ND, Lock JE, Castañeda AR. Baffle fenestration with subsequent transcatheter closure. Modification of the Fontan operation for patients at increased risk. Circulation. 1990;82:1681–1689. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.5.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hvass U, Pansard Y, Böhm G, Depoix JP, Enguerrand D, Worms AM. Bicaval pulmonary connection in tricuspid atresia using an extracardiac tube of autologous pediculated pericardium to bridge inferior vena cava. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1992;6:49–51. doi: 10.1016/1010-7940(92)90099-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hausdorf G, Schneider M, Konertz W. Surgical preconditioning and completion of total cavopulmonary connection by interventional cardiac catheterisation: a new concept. Heart. 1996;75:403–409. doi: 10.1136/hrt.75.4.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Airan B, Choudhary SK, Ready CSK, et al. Total cavopulmonary anastomosis using atrial septal flap: technique and early results. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;16:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soerensen DD, Pekkan K, de Zélicourt D, et al. Introduction of a new optimized total cavopulmonary connection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:2182–2190. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.12.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Backer CL, Deal BJ, Kaushal S, Russell HM, Tsao S, Mavroudis C. Extracardiac versus intra-atrial lateral tunnel Fontan: extracardiac is better. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2011;14:4–10. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinha P, Zurakowski D, He D, et al. Intra/extracardiac fenestrated modification leads to lower incidence of arrhythmias after the Fontan operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:678–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gundry SR, Razzouk AJ, del Rio MJ, Shirali G, Bailey LL. The optimal fontan connection: a growing extracardiac lateral tunnel with pedicled pericardium. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;114:552–559. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okabe H, Nagata N, Kaneko Y, Kobayashi J, Kanemoto S, Takaoka T. Extracardiac cavopulmonary connection of fontan procedure with autologous pedicled pericardium without cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;116:1073–1075. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasaniya NW, Razzouk AJ, Mulla NF, Larsen RL, Bailey LL. In situ pericardial extracardiac lateral tunnel Fontan operation: fifteen-year experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:1076–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.07.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woods RK, Dyamenahalli U, Duncan BW, Rosenthal GL, Lupinetti FM. Comparison of extracardiac Fontan techniques: pedicled pericardial tunnel versus conduit reconstruction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125:465–471. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shikata F, Yagihara T, Kagisaki K, et al. Does the off-pump Fontan procedure ameliorate the volume and duration of pleural and peritoneal effusions? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34:570–575. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Talwar S, Muthukkumaran S, Choudhary SK, et al. A complete extracorporeal circulation-free approach to patients with functionally univentricular hearts provides superior early outcomes. World J Pediatr Congenit Hear Surg. 2014;5:54–59. doi: 10.1177/2150135113507091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mainwaring RD, Reddy VM, Hanley FL. Completion of the three-stage Fontan pathway without cardiopulmonary bypass. World J Pediatr Congenit Hear Surg. 2014;5:427–433. doi: 10.1177/2150135114536908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Talwar S, Mathew AB, Bhoje A, Makhija N, Choudhary SK, Airan B. Extracardiac Fontan with direct inferior vena cava to main pulmonary artery connection without cardiopulmonary bypass. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2018. 10.1177/2150135118765870. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Lemler MS, Scott WA, Leonard SR, Stromberg D, Ramaciotti C. Fenestration improves clinical outcome of the Fontan procedure: a prospective randomized study. Circulation. 2002;105:207–212. doi: 10.1161/hc0202.102237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiore AC, Tan C, Armbrecht E, et al. Comparison of fenestrated and nonfenestrated patients undergoing extracardiac fontan. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:924–931. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hosein RB, Clarke AJ, McGuirk SP, et al. Factors influencing early and late outcome following the Fontan procedure in the current era. The ‘Two Commandments’? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:344–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson LD, Petrossian E, McElhinney DB, et al. Is it necessary to routinely fenestrate an extracardiac Fontan? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:539–544. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Airan B, Sharma R, Choudhary SK, et al. Univentricular repair: Is routine fenestration justified? Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:1900–1906. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01247-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galantowicz ME, Cheatham JP. Fontan completion without surgery. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2004;7:48–55. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Konstantinov IE, Benson LN, Caldarone CA, et al. A simple surgical technique for interventional transcatheter completion of the total cavopulmonary connection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:210–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Metton O, Calvaruso D, Stos B, Ben Ali W, Boudjemline Y. A new surgical technique for transcatheter Fontan completion. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;39:81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanter KR, Haggerty CM, Restrepo M, et al. Preliminary clinical experience with a bifurcated Y-graft Fontan procedure – a feasibility study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gewillig M, Brown SC. The Fontan circulation after 45 years: update in physiology. Heart. 2016;102:1081–1086. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rychik J. The relentless effects of the Fontan paradox. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2016;19:37–43. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Talwar S, Ahmed T, Choudhary S, Chauhan S, Airan B. Understanding the physiology and modelling of the Fontan pathway. Int J Emerg Multidiscip Fluid Sci. 2011;3:1–20.

- 41.Freedom RM, Van Arsdell GS. Biventricular hearts not amenable to biventricular repair. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:641–643. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00620-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choussat A, Fontan F, Besse P, et al. Selection criteria for Fontan’s procedure. In: Anderson RH, Shinebourne EA, et al., editors. Pediatric cardiology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1978. pp. 559–566. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hopkins RA, Armstrong BE, Serwer GA, Peterson RJ, Oldham HN. Physiological rationale for a bidirectional cavopulmonary shunt. A versatile complement to the Fontan principle. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1985;90:391–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Norwood WI, Jacobs ML. Fontan’s procedure in two stages. Am J Surg. 1993;166:548–551. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)81151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jacobs ML, Pelletier GJ, Pourmoghadam KK, et al. Protocols associated with no mortality in 100 consecutive Fontan procedures. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:626–632. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohye RG, Gomez CA, Goldberg CS, Graves HL, Devaney EJ, Bove EL. Tricuspid valve repair in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsang VT, Raja SG. Tricuspid valve repair in single ventricle: timing and techniques. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2012;15:61–68. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shearer L, Justo RN, Marathe SP, et al. Augmentation of the pulmonary arteries at or prior to the Fontan procedure is not associated with worse long-term outcomes: a propensity-matched analysis from the Australia-New Zealand Fontan Registry. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;55:829–836. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezy376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Casella SL, Kaza A, Del Nido P, Lock JE, Marshall AC. Targeted increase in pulmonary blood flow in a bidirectional glenn circulation. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018 ;30:182-188. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Chowdhury UK, Airan B, Sharma R, et al. Univentricular repair in children under 2 years of age: early and midterm results. Hear Lung Circ. 2001;10:3–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Hsu DT, Quaegebeur JM, Ing FF, Selber EJ, Lamour JM, Gersony WM. Outcome after the single-stage, nonfenestrated Fontan procedure. Circulation. 1997;96:II-335–40. [PubMed]

- 52.Talwar S, Singh S, Sreenivas V, et al. Outcomes of patients undergoing primary Fontan operation beyond first decade of life. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2017;8:487–94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Malec E, Schmidt C, Lehner A, Januszewska K. Results of the Fontan operation with no early mortality in 248 consecutive patients. Kardiol Pol. 2017;75:255–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.d’Udekem Y, Iyengar AJ, Galati JC, et al. Redefining expectations of long-term survival after the Fontan procedure: twentyfive years of follow-up from the entire population of Australia and New Zealand. Circulation. 2014;130:S32–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Pundi KN, Johnson JN, Dearani JA, et al. 40-year follow-up after the Fontan operation: long-term outcomes of 1,052 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1700–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Downing TE, Allen KY, Glatz AC, et al. Long-term survival after the Fontan operation: twenty years of experience at a single center. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:243–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Schwartz I, McCracken CE, Petit CJ, Sachdeva R. Late outcomes after the Fontan procedure in patients with single ventricle: a meta-analysis. Heart. 2018;104:1508–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Kumar SP, Rubinstein CS, Simsic JM, Taylor AB, Saul JP, Bradley SM. Lateral tunnel versus extracardiac conduit Fontan procedure: a concurrent comparison. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:1389–96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Lee JR, Kwak J, Kim KC, et al. Comparison of lateral tunnel and extracardiac conduit Fontan procedure. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007;6:328–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Khairy P, Poirier N. Is the extracardiac conduit the preferred fontan approach for patients with univentricular hearts?: the extracardiac conduit is not the preferred fontan approach for patients with univentricular hearts. Circulation. 2012;126:2516–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Sinha L, Ozturk M, Zurakowski D, et al. Intra-extracardiac versus extracardiac Fontan modifications: comparison of early outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107:560–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Marathe SP, Zannino D, Shi WY, et al. Two ventricles are not better than one in the Fontan circulation: equivalent late outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107:852–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Murphy MO, Glatz AC, Goldberg DJ, et al. Management of early Fontan failure: A single-institution experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;46:458–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Almond CS, Mayer JE, Thiagarajan RR, Blume ED, del Nido PJ, McElhinney DB. Outcome after Fontan failure and takedown to an intermediate palliative circulation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:880–887. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.02.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Iyengar AJ, Brizard CP, Konstantinov IE, d’Udekem Y. The option of taking down the Fontan circulation: the Melbourne experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:1346–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hickey EJ, Alghamdi AA, Elmi M, et al. Systemic arteriovenous fistulae for end-stage cyanosis after cavopulmonary connection: a useful bridge to transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Garg P, Talwar S, Rajashekar P, Kothari SS, Gulati GS, Airan B. Common carotid artery to internal jugular vein shunt for managing hypoxemia after a cavopulmonary shunt. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:998–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.De Rita F, Crossland D, Griselli M, Hasan A. Management of the failing Fontan. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2015;18:2–6. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schilling C, Dalziel K, Nunn R, et al. The Fontan epidemic: population projections from the Australia and New Zealand Fontan Registry. Int J Cardiol. 2016;219:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Book WM, Gerardin J, Saraf A, Marie Valente A, Rodriguez F., 3rd Clinical phenotypes of Fontan failure: implications for management. Congenit Heart Dis. 2016;11(4):296–308. doi: 10.1111/chd.12368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Deal BJ, Jacobs ML. Management of the failing Fontan circulation. Heart. 2012;98:1098–1104. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carins TA, Shi WY, Iyengar AJ, et al. Long-term outcomes after first-onset arrhythmia in Fontan physiology. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152:1355–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.07.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mavroudis C, Deal BJ, Backer CL, et al. 111 Fontan conversions with arrhythmia surgery: surgical lessons and outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1457–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Backer CL, Deal BJ, Mavroudis C, Franklin WH, Stewart RD. Conversion of the failed Fontan circulation. Cardiol Young. 2006;16:85–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Oldenburger NJ, Mank A, Etnel J, Takkenberg JJ, Helbing WA. Drug therapy in the prevention of failure of the Fontan circulation: a systematic review. Cardiol Young. 2016;26:842–850. doi: 10.1017/S1047951115002747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Anderson BW, Barron DJ, Jones TJ, Edwards L, Brawn W, Stumper O. Catheter takedown in the management of the acutely failing Fontan circulation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:346–348. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shi WY, Yong MS, McGiffin DC, Jain P, Ruygrok PN, Marasco SF, et al. Heart transplantation in Fontan patients across Australia and New Zealand. Heart. 2016;102:1120–1126. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Backer CL, Russell HM, Pahl E, et al. Heart transplantation for the failing Fontan. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:1413–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rychik J, Goldberg DJ. Late consequences of the fontan operation. Circulation. 2014;130:1525–1528. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.005341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Broda CR, Taylor DA, Adachi I. Progress in experimental and clinical subpulmonary assistance for Fontan circulation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;156:1949–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.04.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rodefeld MD, Frankel SH, Giridharan GA. Cavopulmonary Assist: (em) powering the univentricular Fontan circulation. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2011;14:45–54. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rodefeld MD, Boyd JH, Myers CD, et al. Cavopulmonary assist: circulatory support for the univentricular Fontan circulation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:1911–1916. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)01014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Derk G, Laks H, Biniwale R, et al. Novel techniques of mechanical circulatory support for the right heart and Fontan circulation. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176:828–832. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lin WCP, Doyle MG, Roche SL, Honjo O, Forbes TL, Amon CH. Computational fluid dynamic simulations of a cavopulmonary assist device for failing Fontan circulation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;158:1424–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Biermann D, Eder A, Arndt F, et al. Towards a tissue-engineered contractile fontan-conduit: the fate of cardiac myocytes in the subpulmonary circulation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0166963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]