INTRODUCTION

Individuals who attend electronic dance music (EDM) parties report high levels of synthetic drug use compared with the general population, and are at a high risk for experiencing adverse effects.1, 2 Unknown exposure to various drugs which appear as adulterants in drugs such as ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, MDMA) is common;3, 4 however, unknown exposure to ketamine—a controlled dissociative anesthetic—is understudied. Ketamine was approved for medical use to treat depression by the Food and Drug Administration in 2019, and benefits of medical use have been covered extensively by the media. Given increasing public discourse about ketamine, both known exposure (through recreational use) and unknown exposure (through use of adulterated drugs) may increase.

METHODS

EDM parties in New York City were randomly selected each week from January through August 2019 using time-space sampling methods.5 Most selected parties were held at nightclubs, but we also surveyed outside of a large EDM dance festival. After providing informed consent, adult attendees entering parties completed a survey regarding past-year drug use (N = 794 with a survey response rate of 64%). A total of 216 (27.2%) provided a hair sample and 65.3% (n = 141) of samples were large enough to be analyzed (≥ 20 mg). Hair analyses were conducted using ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Hair test results for the 75 unanalyzable samples were imputed using chained equations and combined using Rubin’s rules. We calculated sample weights based on survey response rates and self-reported frequency of party attendance to make results generalizable to this population.2 We compared self-reported ketamine use to (1) detection of any level of ketamine and (2) above-threshold ketamine levels detected (≥ 0.5 ng/mg).6 We then adjusted estimated prevalence defining ketamine exposure as reporting use or testing positive for use and examined correlates of testing positive for any ketamine exposure after not reporting use using generalized linear model with Poisson and log link. All methods were approved by the New York University Langone Medical Center’s institutional review board.

RESULTS

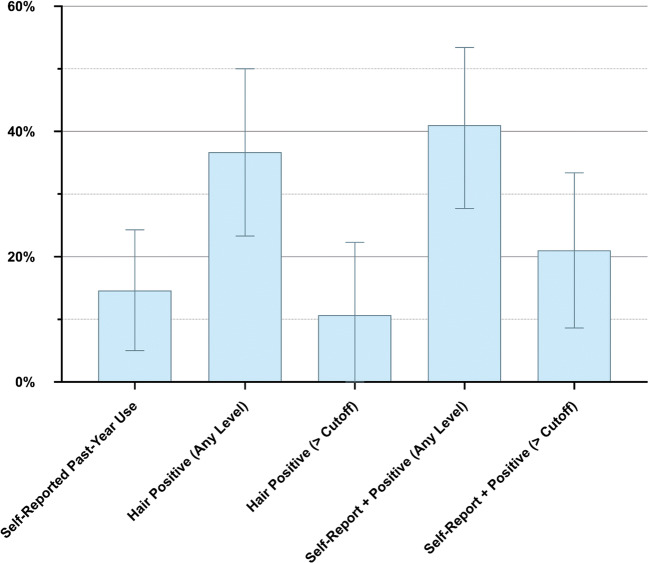

In total, 14.6% of EDM party attendees reported using ketamine in the past year (Fig. 1). When considering hair analysis, 36.7% were positive for any level of ketamine and 10.7% were positive considering the cutoff level of ≥ 0.5 ng/mg. Estimating the prevalence of use based on self-reported use or hair positivity, the prevalence of ketamine use is 40.6% when considering any hair positivity (2.8 times higher than self-reported use), and the prevalence is 21% when considering positivity above the cutoff level.

Figure 1.

Estimated prevalence of ketamine exposure according to self-report and to hair test results.

While 73.3% of those reporting past-year ketamine use tested positive for exposure, 30.4% of those not reporting ketamine use also tested positive for at least some ketamine exposure. In the multivariable model (Table 1), testing positive for MDMA was associated with increased risk of testing positive for ketamine after not reporting use (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR] = 3.67, 95% CI 1.44–9.38), with 65.0% of those testing positive for MDMA testing positive for ketamine exposure after not reporting use. In addition, those identifying as other/mixed race (aPR = 3.74, 95% CI 1.04–13.48) were at increased risk for testing positive for ketamine exposure after not reporting use.

Table 1.

Correlates of Testing Positive for Ketamine Exposure Among Those Not Reporting Use

| Ketamine positive among those not reporting use (%) (SE) | aPR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–25 | 19.6 (10.9) | 1.00 |

| ≥ 25 | 36.8 (9.8) | 1.70 (0.52–5.59) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 37.0 (10.2) | 1.00 |

| Female | 17.9 (9.1) | 0.75 (0.25–2.29) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 20.0 (10.5) | 1.00 |

| Black | 3.8 (4.9) | 0.20 (0.00–17.41) |

| Hispanic | 37.6 (15.9) | 1.49 (0.49–4.47) |

| Other/mixed | 58.2 (17.9) | 3.74 (1.04–13.48) |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 46.7 (20.9) | 1.00 |

| Some college | 28.9 (14.0) | 0.48 (0.08–2.83) |

| College degree or higher | 23.6 (8.4) | 0.44 (0.17–1.19) |

| Sexual identity | ||

| Heterosexual | 27.8 (8.5) | 1.00 |

| Gay/lesbian | 57.3 (31.8) | 2.17 (0.40–11.84) |

| Bisexual or other | 16.9 (20.2) | 0.70 (0.09–5.69) |

| Other drugs used in the past year | ||

| 0 drugs | 34.4 (13.0) | 1.00 |

| 1 drug | 35.3 (16.2) | 1.15 (0.29–4.52) |

| 2–3 drugs | 15.5 (7.8) | 0.97 (0.24–3.84) |

| 4–5 drugs | 27.8 (16.4) | 1.41 (0.21–9.42) |

| Hair positive for MDMA | ||

| No | 18.4 (6.8) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 65.0 (16.6) | 3.67 (1.44–9.38) |

The “other drugs” variable is defined as the total number of the following drugs reportedly used in the past year: cocaine, ecstasy/3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), amphetamine (nonmedical use, defined for participants as use without a prescription or in a manner in which it was not prescribed; for example, to get high), 3,4-methylenedioxy-amphetamine (MDA), methamphetamine, and 4-bromo-2,5-dimethoxyphenethylamine (2C-B). SE standard error, aPR adjusted prevalence ratio, CI confidence interval

DISCUSSION

We detected extensive underreporting of ketamine use in this population with prevalence of use nearly tripling when considering both self-report and detection in hair samples. Intentional underreporting of drug use is common, but underreporting in this population is higher than expected considering self-reported use of synthetic drugs was common. Since it is unlikely that a participant would report use of drugs such as ecstasy and intentionally underreport ketamine use, we believe many cases of positive detection may be due to unknown exposure through use of adulterated drugs. Ecstasy/MDMA adulteration in particular is common,3, 4 and we determined that testing positive for MDMA was a risk factor for testing positive for ketamine after not reporting use. Racial/ethnic minorities were also more likely to provide a discordant report. More research is needed to determine whether these individuals are intentionally underreporting use or whether they are at a higher risk for unknown exposure to ketamine.

This study is limited as we could not determine whether ketamine use was intentionally denied and results may not generalizable beyond at-risk populations. In conclusion, as media coverage about medical benefits of ketamine continues, it is important to continue to examine current trends in both known and unknown use of this drug.

Funding Information

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01DA044207 (PI: Palamar) and K01DA038800 (PI: Palamar).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All methods were approved by the New York University Langone Medical Center’s institutional review board.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Palamar JJ, Griffin-Tomas M, Ompad DC. Illicit Drug Use Among Rave Attendees in a Nationally Representative Sample of US High School Seniors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;152:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palamar JJ, Acosta P, Le A, Cleland CM, Nelson LS. Adverse Drug-Related Effects among Electronic Dance Music Party Attendees. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;73:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krotulski AJ, Mohr ALA, Fogarty MF, Logan BK. The Detection of Novel Stimulants in Oral Fluid from Users Reporting Ecstasy, Molly and MDMA Ingestion. J Anal Toxicol. 2018;42:544–553. doi: 10.1093/jat/bky051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliver CF, Palamar J, Salomone A, et al. Synthetic Cathinone Adulteration of Illegal Drugs. Psychopharmacology. 2018;236:869–879. doi: 10.1007/s00213-018-5066-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacKellar DA, Gallagher KM, Finlayson T, Sanchez T, Lansky A, Sullivan PS. Surveillance of HIV Risk and Prevention Behaviors of Men who Have Sex with Men--A National Application of Venue-Based, Time-Space Sampling. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 1):39–47. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salomone A, Gerace E, Diana P, et al. Cut-off proposal for the detection of ketamine in hair. Forensic Sci Int. 2015;248:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]