INTRODUCTION

Out-of-network spending by patients and payers has gained increasing policy attention, including two recent US Senate proposals to protect patients from high out-of-network costs.1, 2 Out-of-network care is particularly common in behavioral health, as mental health providers are less likely to participate in insurer networks.3 The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act likely increased access to out-of-network behavioral health,4 while the opioid epidemic has increased demand for substance use disorder treatment. Despite this, little is known about out-of-network spending for behavioral health over the last decade,5 especially whether out-of-network substance use disorder spending has deviated from that of other behavioral health services.

METHODS

We analyzed out-of-network spending in behavioral health for 14–17 million enrollees in 2008–2016 using the Truven Commercial Claims and Encounters Database, a national population with employer-sponsored insurance. We included employers who contributed claims throughout the study period; all enrollees in our sample were enrolled for at least 1 year. Spending was the paid amount on each claim, reflecting negotiated prices and patient cost-sharing, but any balance billing was not observable. We assessed changes in the share of spending out-of-network using a person-level linear model adjusted for age, sex, health risk, insurance plan, and region.

We defined behavioral health in three ways. First, we examined all mental and behavioral health services based on Current Procedural Terminology codes. Next, because psychiatrists often opt out of insurance networks, we analyzed all services billed by psychiatrists, defined with the specialty code of the servicing provider. Finally, focusing on the most vulnerable patients, we examined specialized behavioral health facilities, defined using the behavioral health place of service codes. Patients served by these facilities often have little choice among providers and high-cost behavioral health needs.

RESULTS

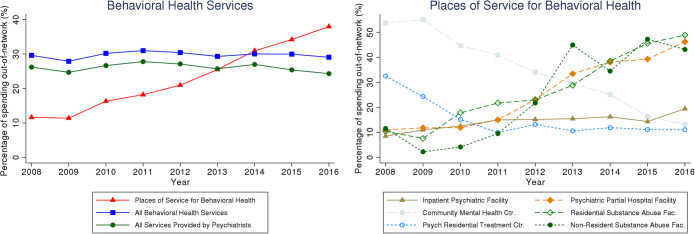

The share of spending out-of-network for all behavioral health services and all services provided by psychiatrists remained stable at 26–30% over the study period. However, the share of spending out-of-network for behavioral health places of service increased sharply from 12.6% in 2008–2010 to 34.4% in 2014–2016 (Fig. 1, left), an average annual increase of 2.1 percentage points (p < 0.001) (Table 1).]-->

Figure 1.

Share of spending on behavioral health out-of-network. The percentage of spending out-of-network was calculated by dividing out-of-network spending by the sum of out-of-network and in-network spending. “Places of service for behavioral health” are decomposed in the right-sided graph. We defined the place of service using the provider place of service designations at the claim level for both professional and facility fees in the inpatient and outpatient settings. “All behavioral health services” included outpatient professional and facility psychiatric services. “All services provided by psychiatrists” included all professional claims for inpatient and outpatient care billed by psychiatrists. We identified physician specialties using the primary specialty code listed for the servicing provider at the claim level.

Table 1.

Levels of Spending and Percent of Spending Out-of-Network

| 2008–2010 (N = 14,489,925) | 2011–2013 (N = 15,672,236) | 2014–2016 (N = 16,951,922) | Average annual change in percent out-of-network (95% CI)‡ | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average annual spending ($)* | Percent out-of-network (%)† | Average annual spending ($)* | Percent out-of-network (%)† | Average annual spending ($)* | Percent out-of-network (%)† | |||

| All mental and behavioral health services | 40,162 | 29.2 | 53,683 | 30.2 | 68,606 | 29.7 | − 0.18 (− 0.67, 0.32) | 0.49 |

| All services provided by psychiatrists | 12,416 | 25.8 | 16,084 | 26.8 | 18,959 | 25.5 | − 0.17 (− 0.55, 0.22) | 0.39 |

| Places of service for mental and behavioral health§ | 2801 | 12.6 | 3973 | 21.6 | 4850 | 34.4 | 2.07 (1.05, 3.08) | < 0.001 |

| Place of service | ||||||||

| Community mental health center | 271 | 51.5 | 314 | 34.3 | 387 | 17.9 | 0.58 (− 0.65, 1.81) | 0.36 |

| Inpatient psychiatric facility | 375 | 10.2 | 147 | 15.2 | 130 | 16.8 | 1.23 (0.63, 1.83) | < 0.001 |

| Non-residential substance abuse facility | 50 | 5.3 | 97 | 28.6 | 173 | 42.8 | 2.23 (− 0.03, 4.49) | 0.05 |

| Partial hospital psychiatric facility | 1056 | 11.5 | 1555 | 24.2 | 2258 | 41.5 | 5.41 (3.66, 7.15) | < 0.001 |

| Residential substance abuse facility | 841 | 11.6 | 1560 | 24.4 | 1708 | 44.3 | 2.75 (1.41, 4.10) | < 0.001 |

| Psychiatric residential treatment center | 208 | 25.0 | 299 | 11.2 | 196 | 11.5 | − 3.21 (− 8.09, 1.68) | 0.20 |

*Average annual spending is expressed as dollars per 1000 individuals, inflation-adjusted to 2016 US dollars

†Percent of spending out-of-network was calculated by dividing out-of-network spending by the sum of out-of-network and in-network spending

‡Average annual changes in the share of spending out-of-network were estimated using an enrollee-level ordinary least squares model adjusted for age, sex, health risk, insurance plan, and region

§Places of service for mental and behavioral health were separately analyzed

This growth was driven by three types of facilities (Fig. 1, right). Residential substance abuse facilities saw out-of-network spending rise from 11.6% in 2008–2010 to 44.3% in 2014–2016, a 2.8 percentage-point annual increase (p < 0.001); non-residential substance abuse facilities from 5.3 to 42.8%, a 2.2 percentage-point annual increase (p = 0.05); and psychiatric partial hospital facilities from 11.5 to 41.5%, a 5.4 percentage-point annual increase (p < 0.001) (Table 1). These three types of facilities comprised about 80% of spending at behavioral health facilities.

DISCUSSION

The rapid increase in out-of-network spending on behavioral health facilities could have multiple explanations. These facilities may be moving out-of-network to achieve higher prices than negotiated in-network prices (a price explanation).6 Amidst increased demand for substance use disorder treatment, capacity constraints at in-network facilities may be driving patients to out-of-network facilities (a volume explanation). Additionally, patient preferences and provider referral patterns may play a role in the increased use of out-of-network facilities.

For patients, out-of-network care is associated with greater out-of-pocket costs. Thus, increased spending on out-of-network behavioral health facilities likely reflects greater financial burden for patients who need such treatment. This may cause some patients to forgo treatment or use fewer services for an already undertreated disorder. For US employers, who sponsor health insurance coverage for about half of the nation’s population, the higher prices of out-of-network services likely generate additional pressure to cut costs (such as through narrowing the scope of coverage, raising deductibles or cost-sharing, or through wages or other means). Future research should consider whether patients have adequate access to in-network behavioral health facilities.

Funding Information

This work was financially supported by a grant from the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (NIH Director’s Early Independence Award, 1DP5OD024564, to Dr. Song), National Institutes of Health (5R21MH109783, to Dr. Busch), National Library of Medicine (T15 LM007092, to Dr. Benson).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Zirui Song reports grants from National Institutes of Health, Office of the Director, during the conduct of the study and personal fees from International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans, outside the submitted work. Timothy Lillehaugen has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Susan Busch reports grants from the National Institutes of Health. Nicole Benson reports grants from the National Library of Medicine, during the conduct of the study. Jacob Wallace has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hall MA, Adler L, Ginsburg PB, Trish E. Reducing Unfair Out-of-Network Billing - Integrated Approaches to Protecting Patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(7):610–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1815031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun EC, Mello MM, Moshfegh J. Baker LC. JAMA Intern Med: Assessment of Out-of-Network Billing for Privately Insured Patients Receiving Care in In-Network Hospitals; 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176–81. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGinty EE, Busch SH, Stuart EA, Huskamp HA, Gibson TB, Goldman HH, Barry CL. Federal parity law associated with increased probability of using out-of-network substance use disorder treatment services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(8):1331–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu WY, Song C, Li Y, Retchin SM. Cost-Sharing Disparities for Out-of-Network Care for Adults With Behavioral Health Conditions. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1914554. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pelech D, Hayford T. Medicare Advantage And Commercial Prices For Mental Health Services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(2):262–267. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]