Abstract

Objectives

While receptive art engagement is known to promote health and wellbeing, active art engagement has not been fully explored in health and nursing care. This review is to describe the existing knowledge on art making and expressive art therapy in adult health and nursing care between 2010 and 2020.

Methods

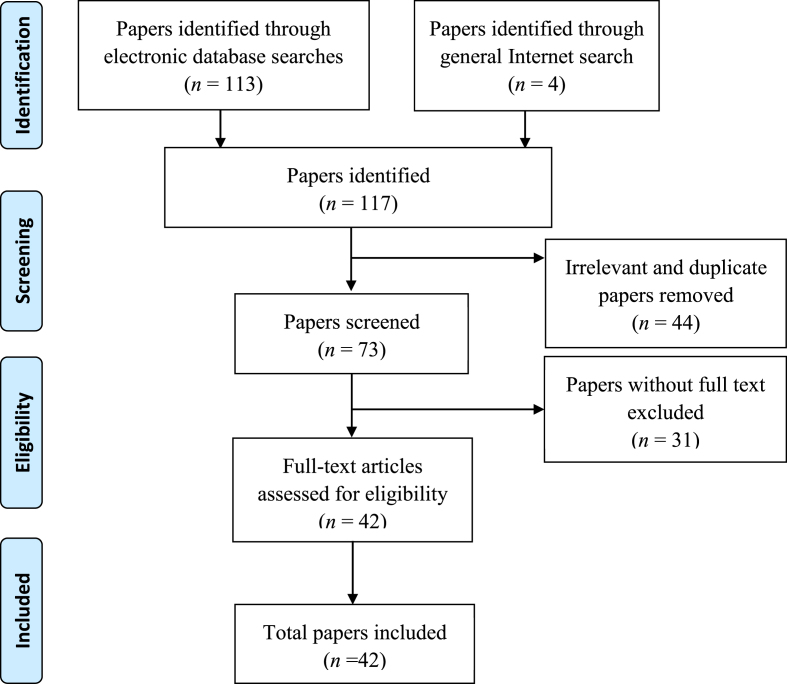

Relevant studies and grey literature were searched and identified between March 17 and April 10, 2020 from EBSCO, CINAHL, Medline and ERIC databases and a general Internet search. Following data charting and extraction, the data (n = 42 papers) were summarized and reported in accordance with PRISMA-ScR guidelines.

Results

In the included papers, both art making and expressive art therapy were seen in different health care and nursing contexts: yet not the home care context. The emphasis of art activities were group activities for chronically or terminally ill residents, adults aged 65 years or older. A focus on personal narrative was often seen, which may explain why art activities appear to be linked to acknowledging and building new strengths and skills, making meaning of experiences, personal growth, symptom alleviation, and communication; all used to foster collaboration between patients, patients’ near-ones and health care professionals.

Conclusions

Art activities appear to be suitable for every context and can promote personcenteredness and the measurement of nursing outcomes, and they should be considered an essential part of health and nursing care, nursing education and care for health care personnel.

Keywords: Adult, Aged, Art making, Art therapy, Health care, Nursing care, Person-centered care

What is known?

-

•

Receptive art engagement is known to promote health, self-worth, accomplishment and patients’, patients’ near-ones’ and health care professionals’ social engagement.

-

•

Nursing is often described as an art, and health care professionals and patients engaging in art and/or craft making together as fellow human beings has been shown to have a positive effect for both parties and can help diminish power hierarchies.

-

•

Humanistic expressive art therapy is characterized by the work process itself, exposure to a wide range of materials, and the employment of a variety of techniques in therapeutic intervention, used to help individuals explore their hidden feelings in a supportive setting.

What is new?

-

•

Art activities appear to be mainly organized as part of research or general projects, not as systematic health or nursing care interventions, even though most art activity types can be undertaken alone without any special skills and/or significant material investments.

-

•

Health care professionals should be encouraged to use art activities intentionally, to get to know each persons’ narratives, because the meaning of the person’s experiences is a vital part of evidence-based nursing art and person-centered care.

-

•

Whether art activities should be overseen by a nurse or a professional art therapist can be argued: art activity outcomes can be related to nursing goals and nursing outcomes, which could be measured through observations of patients’ art activities and narratives linked to such activities.

1. Introduction

The arts play a significant role in modern health sciences, and they can be used to skillfully interpret emotions, helping one better understand oneself and others [1]. In health and nursing care, in addition to a focus on the signs and symptoms of a health problem or an illness, there should be a focus on potential (skills or strengths) and satisfaction (areas, actions and activities that bring a satisfying feeling). Seen more broadly, this should include person-centered health and nursing care interventions [2] and nonpharmacological interventions using art [3]. The arts and creative expression have been shown to promote health, self-worth, accomplishment, and social engagement [3]: for patients, patients’ near-ones and health care professionals [4].

The arts can be defined as music, performance arts (theatre, dance), the visual arts, the literary arts (novel-writing, poetry, other forms of text) and the huge range of applied arts [5]. The arts can play an integrative role in facilitating lifelong learning, seen as discovering and building new skills and making meaning of experience, because through art one’s past and present thoughts can be combined. Arts engagement can be either receptive (attending concerts, theatre, reading) or active (art making) [6]. One does not need to be an artist or have any special skills to express oneself through art making; the most important thing is an open attitude to creativity in everyday life. This allows one to give oneself and others a chance to interact with and be touched by art and to vary the pattern of everyday life.

Creative expression is characterized by active participation in the process of bringing something new into existence: the production or performance of art or the creation of an original idea, perspective or process [7]. Creative activities facilitate self-expression, social interaction, communication, sensory stimulation and emotional relief, in a failure-free environment [8]. Art therapy can also serve as a link through which individuals can explore past and present experiences, review one’s life, cope with, adjust to, and adapt to age-related changes, be supported during an emotional crisis, or be given care related to physical loss (for example, loss of an organ, memory or mobility) [9]. Art therapy has especially been applied in oncologic, dementia and mental care. Art therapy must be overseen by an art therapist, and time must be given to verbally processing the feelings arising from the art experience. Conversely, art making need not be overseen by an art therapist. Consequently, it is a practical alternative to art therapy and can still serve as a basis for a person-centered approach to health and nursing care.

2. Background

2.1. The arts and art making in health and nursing care

In a Health Evidence Network synthesis report from the World Health Organization [2], researchers found evidence that the arts play a major role in the promotion of good health, the prevention of a range of mental and physical health conditions, and the treatment or management of conditions arising across the life-course. For people with acute conditions, access to the arts in the hospital and/or in the community can help improve experience and outcomes in emergency care and rehabilitation. For people with chronic conditions, access to the arts can support mental health, physical functioning and social and emotional well-being. The arts can even be used to address complex challenges for which there are no current health care solutions. For both those living at home or in an institution, the arts can enrich one’s life. Enjoying the arts by, for example, visiting an art gallery, is not likely to produce lasting effects. However, even for those with severe dementia, enjoyment can be derived from the arts [10]. Valuable social and emotional support in palliative care and bereavement can also be provided through the arts [2]. Furthermore, the arts have even been used to investigate brain alterations in artists arising from frontotemporal dementia [11] and dementia-related delirium and confabulation [12].

Engagement in creative expression can also lead to improved outcomes for patients [3,4,8]. While art making can be perceived as too demanding, art crafting (craft making) can be more easily accepted. Craft making is defined as a form of production that requires some skill, personal insight and practice and encompasses any of the manual arts: for example, weaving, knitting, felting, quilting, embroidery, needlework, basket-weaving, leatherwork, woodwork, copper-tooling or metalcraft. Craft making as purposeful activity has for decades traditionally been used in occupational therapy and/or rehabilitation [13]. Art and/or craft making have been shown to alleviate symptoms of, for example, depression and fatigue during chemotherapy [14], stress and anxiety [15] and can help repair or maintain function in diverse parts of the body or be used to motivate patients to regain function so that they can participate in society again. Health care professionals and patients engaging in art and/or craft making together as fellow human beings has also been shown to have a positive effect for both parties and can help diminish power hierarchies [13]. Furthermore, the implementation of arts programs in medical education or health care organizations has been found to improve students’ and personnel’s mental health and well-being and reduce stress and burnout [4].

Storytelling or individual narratives can be considered creative expressions [16]. Stories illuminate the person, allowing a glimpse of him/herself in decades past. Through stories one not only gains information about the person being cared for but can also facilitate the retrieval of experiences, resources, values and wishes. Reminiscing about one’s own history or home is essential to a person-centered approach, not only in elderly care [17] but also in situations that presuppose a need for identity reconfiguration and restored self-esteem, such as disruption, divorce or chronic illness. By asking a person to, “Tell me a story about…”, one can uncover information critical to the planning of effective care consistent with the person’s desires and goals [18]. Used as an alternative to interpreting how a person perceives his/her body image during a health problem or illness, individual narrative in the form of asking a person to draw or tell a story can also be used to help improve self-worth [19]. Individual narratives in patient education can also take the form of illustrated stories, comic strips [12] or social theatre [20].

Creative expression not only enhances a person’s health and well-being, it also enriches communities. The arts and culture have played a crucial role in building cities and towns, fostering unique neighborhoods, and binding communities together [4]. The arts are also linked to positive effects in building intergenerational bonds [21]. Engagement with the arts can help address social determinants of health, for example through the development of social cohesion, reduction of loneliness and social isolation and building of individual and group identity. The arts are also effective in reaching people who are either less likely to seek health care or who experience more barriers when seeking it and therefore may have a higher risk of adverse health outcomes [4].

2.2. Expressive art therapy in health and nursing care

Humanistic expressive art therapy is unlike the analytic or medical model of art therapy, where art is used to diagnose, analyze and “treat” people [22]. It is characterized by the work process itself, exposure to a wide range of materials, and the employment of a variety of techniques in therapeutic intervention [9]. Expressive art therapy can help individuals explore their hidden feelings in a supportive setting [17]. Used to facilitate growth and healing and expressed through various art forms (movement, drawing, painting, sculpting, music, writing, sound, and improvisation) [22], expressive art therapy can be considered a process of discovering oneself through any art form that emerges from an emotional depth. The creative connection can be considered a spiral of activities, through which layers of inhibition are removed. Through a person-centered approach in expressive art therapy, the therapist’s role – being empathic, open, honest, congruent, and caring – can be emphasized. Expressive art therapy is not used to analyze or solve a problem, nor is it about (striving for) perfection; it is a path to self-expression and a way to release one’s feelings.

Art therapists are qualified health professionals who have undertaken postgraduate studies in art therapy [22]. They must also register with and be authorized by national supervisory boards, for example, with the National Supervisory Authority for Welfare and Health in Finland (https://www.valvira.fi/web/en/healthcare/professional_practice_rights). Without full qualifications and registration, a person cannot act as an art therapist nor practice art therapy; “art therapist” is a protected title [22]. This is important, because it allows one to discern between a professional art therapist and a “non-professional” who is merely facilitating art making.

In one review [23], art therapy was found to be effective but not typically more effective than standard therapy. The researchers in that review failed to define the type of art therapy explored or in what/which context(s), but did note that expressive art therapy was excluded. In another review in which the researchers limited inclusion to papers in which art therapy was noted as the specific intervention [24], researchers found that art therapy can lead to positive treatment outcomes for the populations (all ages) and settings (schools, outpatient clinics, day treatment centers and treatment centers, hospitals and nonclinical settings) included in that review.

2.3. Nursing art and person-centered care

Certain nursing theorists have explored the artistic aspects of nursing. In accordance with Jean Watson, the union between the nurse and the person (individual or community level) is an artistic act and an expression of caregiving, which is unique and personal [25]. Also other nursing theorists such as Martha Rogers, Faye Glen Abdellah, Ernestine Wiedenbach and Rosemarie Rizzo Parse define nursing as an art [26]. As a concept, the art of nursing can be defined as, “the intentional creative use of oneself, based upon skill and expertise, to transmit emotion and meaning to another. It is a process that is subjective and requires interpretation, sensitivity, imagination, and active participation” [27]. Nursing is an aesthetic knowledge (art), where the nurse must make use of his/her internal creative resources to transform others’ experiences. The action, behaviors, attitudes and interactions occurring in a given narrative reveal the transformation, performance and creativity inherent to the narrative [28]. Aesthetic knowing, seen as the nurse’s perception of the person and the person’s needs, is related to the nurse’s “artful” performance of manual and technical skills. The nurse’s perception of what is significant in the person’s behavior is revealed through the pattern underlying the nurse’s aesthetic knowing. Accordingly, one can maintain that the pattern of aesthetic knowing is focused on particulars rather than universals [29].

Virginia Henderson argued that, “the nurse’s goal is to assist the patient to become complete, whole, or independent” [30]. While nurses follow a physician’s therapeutic plan, individualized care is seen and realized through the nurse’s creativity in planning for care. In good, person-centered care, nurses actively seek and foster patient narratives or other creative patient expressions to gain mutual understanding of not only symptoms and problems but also strengths and areas of satisfaction. In person-centered care, the “whole patient”, seen as a psychosocial and existential person, is taken into consideration in health and nursing care. This is shown as respect for the personal narratives that reflect a person’s sense of self, lived experiences and relationships and the recognition of this respect through the safeguarding of a partnership in shared decision-making and in meaningful activities in a personalized environment [[31], [32], [33]]. In person-centered care, storytelling or narratives (for example, expressed through art making, crafting or art therapy activities) and the art of nursing are interwoven. To foster such care, nurses need not be art therapists and patients need not be artists. However, the nurses should know how art making and expressive art therapy can be used (contexts, types, to whom, by whom, eventual challenges) and what are the outcomes that could be expected.

3. Aim

The aim of this scoping review was to describe the existing knowledge on art making and expressive art therapy in adult health and nursing care. The research questions were:

-

-

How is art making used in adult health and nursing care?

-

-

How is expressive art therapy used in adult health and nursing care?

-

-

What are the outcomes of the different art making and/or expressive art therapy activities in adult health and nursing care?

4. Methods

To describe the existing knowledge [34] on art and art therapy in adult health and nursing care, a scoping review method was chosen. Scoping reviews constitute a relevant method used to map evidence in complex research areas. Arksey and O’Malley found that while systematic reviews tend to include a focus on a well-defined research question and design, scoping reviews are used to explore a broader research question and include studies that reflect a greater variety of designs. The steps in a scoping review include the identification of research question(s), identification of relevant studies, selection of studies, charting of data, and summarization and reporting of results [35]. The PRISMA-ScR checklist was used to guide the reporting in this review [34].

4.1. Search strategy and information sources

As a first step, the identification of research questions occurred. This was followed by the identification of relevant studies and grey literature, which included theoretical papers, statement papers and practice-oriented development reports. Between March 17 and April 10, 2020, searches of the EBSCO, CINAHL, Medline and ERIC databases were conducted. A general Internet search (Google and Google Scholar) was also undertaken to identify grey literature. The MeSH search terms included “art” AND “nursing” as subject terms. As the main topic of interest, the search term (major heading) “art” was set to include: art as art making, expressive art therapy, paintings, creativeness, creativity, nursing as art, museums, photography, music therapy, drawings, and literature. The search term (major heading) “nursing” was set to include all aspects of professional nursing and health care provided by the search engine (f.eg. nursing as art, nursing education, nursing care, nursing practice, caring, nursing as profession, nursing science; psychiatric nursing, oncology nursing, occupational health care, public health care and so on).

4.2. Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria included full-text published or to-be-published, peer-reviewed studies, theoretical papers and grey literature with a focus on art making or expressive art therapy with adults (>18 years) in the context of health and nursing care between January 2010 and December 2020. Studies and papers were to be written in English or Finnish, and grey literature had to be either a statement paper or a practice-oriented development report. The time period for this study was chosen to complement already-existing reviews on art therapy: prior to 1999 [18], 1999–2007 [24] and a 2008–2013 review of the efficacy of art therapy [36]. During the search, no other reviews of art making or expressive art therapy in health and nursing care were found.

4.3. Charting and analysis of data

During the screening of potentially relevant papers for inclusion, 117 references were identified through the electronic database searches and general Internet search (Fig. 1). Level one testing included title and abstract screening, during which conference papers without actual research or project results, commercial websites marketing art therapy, papers with a focus on neurological processing during art or art therapy experiences (considered irrelevant, n = 11) and duplicates (n = 33) were excluded. Relevant papers were then retained for full-text review in level two testing and reviewed by the first author (HVR). In this phase, papers without a free full-text version (n = 31) were excluded due to economic reasons.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of paper selection process.

The data extracted from each paper (n = 42) included: type of art making or expressive art therapy activity, context, research details (sample size and characteristics, intervention, method(s) of data collection) and outcomes and/or conclusions (theoretical papers). Following data charting and extraction, the data were summarized to answer the research questions [35,37].

5. Results

5.1. Art making in health and nursing care

Art making was described in 27 papers (Table 1), in contexts ranging from primary health care for community members [[38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45]] to a penal institution [46]. The professional responsible for the art making was not always explicitly described, nor the involvement/role of researcher(s). Most participants were over 65 years of age. In seven papers, the art making activity was conducted in a group. In some papers, the persons involved in the art making could not speak [47,48]. In one paper, patients’ near-ones were involved in art making [49] and in another paper, a member of the professional team made the art, emanating from the patient’s narrative [50]. There were no papers in which health care or nursing professionals were solely engaged in art making.

Table 1.

Type of art making, context, research details and outcomes/conclusions, in health and nursing care between 2010 and 2020 (in alphabetic order, by author name; n = 27 papers).

| Authors | Type of art making | Context | Research design | Sample | Intervention | Method(s) of data collection | Outcomes/conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camic, Tischler & Pearman 2014 [49] | Sketchbooks for drawing, a water-based paints, pastels, colored pencils, collage material, glue, quick-drying modelling clay and printmaking, writing. | Dementia care at home | A mixed-methods pre-post design | N = 24. Twelve persons (58–94 years) with mild or moderate dementia and 12 of their near-ones. | Eight 2-h sessions over an eight-week period at both sites (a traditional and a contemporary art gallery). The sessions were divided into two parts: 1 h of art viewing and discussion followed by 1 h of art making. | The Dementia Quality of Life (DEMQOL-4), the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI), the Bristol Activities of Daily Living scale (BADLS), and interviews, both prior to and 2–3 weeks after the intervention. | A non-significant trend toward a reduction in carer burden over the course of the intervention. Well-being benefits included positive social impact resulting from feeling more socially included, self-reports of enhanced cognitive capacities for people with dementia, and an improved quality of life. |

| Canning & Phinney 2015 [47] | An intergenerational dance (ballet) program (in group). | A long-term care home | A cross-sectional study | N = 15 older adults with a wide range of chronic health conditions and physiological impairments; the majority had moderate to advanced dementia and some were unable to speak. School children (N = 7). | Weekly ballet classes over a six-month period. | Video recordings, interviews. | Recordings of classes gave the individuals with dementia participating in weekly ballet classes in the care home a “visual voice”; the children were interviewed. The “They Aren’t Scary” documentary film was produced from the video footage. Video served as an excellent method to document the social interactions between the children and the older adults. |

| Crone et al., 2018 [40] | Poetry, ceramics, drawing, mosaic and painting (in group). | Arts-on-referral: primary care and mental care | A prospective longitudinal follow-up (observational) design study over a 7-year period (2009–2016) | N = 1297 adults (mean age 51.9 years); healthy community members. | An 8-week or 10-week intervention. | Demographic data, the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) pre-intervention (week 1) and post-intervention. | A significant increase in mental well-being was observed from pre- to postintervention (P < 0.001, two-tailed) for those that completed and/or engaged. |

| Davies, Knuiman & Rosenberg 2016 [42] | Active engagement in the recreational arts. | Community members | A cross-sectional study | N = 702 adults (18–>60 years). | Not specified. | A telephone survey, Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS). | Respondents with high levels of arts engagement had significantly better mental well-being than those with none, low and medium levels of engagement (P = 0.003). |

| de Guzman 2010 [46] | Drawing an image of oneself. | A penal institution | A phenomenological descriptive study | N = 6 male inmates (>55 years). | Two-week intervention: drawing an image of oneself before and after incarceration. | Individual in-depth interviews before and after the intervention. | Intervention proved to be a powerful stimulator whereby the subjects’ self-esteem was heightened. |

| de Guzman et al., 2011 [62] | Traditional Filipino arts. | An institutionalized group care setting | A phenomenological descriptive study | N = 3 women (61–86 years). | – | Individual semi-structured interviews, field notes. | A triad of factors contribute to depression and decline in self-esteem among respondents, labeled as Wearing Out, Walking Away, and Wanting More. Three aspects of self-esteem were identified: Making it Through, Making it Happen, Making a Difference. |

| Egloff et al., 2012 [57] | Marking one’s pain on a pre-printed body diagram. | A tertiary university hospital | A single comparison | Two groups of adult (>20 years) inpatients with chronic pain; N = 62 with somatoform-functional pain; N = 49 with somatic-nociceptive pain. | – | Quantitative methods of picture analysis: the form and the orientation of lines in drawings of the body scheme. | Identification of 13 drawing criteria, pointing with significance to a somatoform-functional pain disorder (all P-values ≤0.001). |

| Esker & Ashton 2013 [55] | Watercolor painting. | A Special Care Unit of one long-term care center | A single subject withdrawal experiment | N = 3 elderly (mean age 88 years) female inpatients with dementia. | Two weeks of 30 min daily individualized painting sessions. | Observations targeted toward measuring participant observable alertness on scale 0–4. | All three participants displayed an overall pattern of a lower coded behavior score during baseline, signifying passivity, and a score closer to 3 during the intervention phases, signifying involvement in an activity. |

| Hardcastle, McNamara & Tritton 2015 [53] | Auto-photography and drawings | Cardiac rehabilitation program | Cross-sectional study | N = 23 adults (59–87 years); cardiac rehabilitation patients >2 years after cardiac rehabilitation period. | – | Semi-structured interviews. | Motivation to physical activity arose from fear of death and ill-health avoidance, critical incidents, overcoming aging, social influences, being able to enjoy life, provision of routine and structure, enjoyment and psychological well-being. |

| Ho et al., 2010 [60] | Drawings on the theme of “my cancer”. | Three major hospitals | Participants in this study were drawn from a large intervention study, which aimed to understand the effectiveness of the locally developed indigenous Eastern-based body–mind–sprit psychosocial intervention | N = 67 breast cancer patients (37–69 years). | A weekly 3-h intervention for five consecutive weeks. Content was based on a holistic approach, in which Eastern healing philosophy with Western cognitive reframing techniques within a group therapy format were emphasized. Prior to and after the intervention participants were asked to create a drawing of “my cancer”. | The images were rated along three dimensions: body, mind, and spirit. | The portrayal of negative emotions was greatly reduced from 52% to 3%, while positive emotions increased from 28% to 93% in post-drawings. |

| Houpt et al. 2016 [51] | Zine-making. | Nursing homes | A project description | – | – | Dialogues between attendees and presenters. | The presentations showcase the participants’ strengths, despite the need to account for differences in speech, vision challenges, and other limitations. |

| Kelemen, Surman & Dikomitis 2018 [41] | Cultural animation full-day workshops (in group). | Community patient and public engagement project | A cross-sectional study | N = 25 adults (25–75 years). | – | Photographs, field notes, interviews. | The workshops increased human connectivity, led to rethinking of and co- creating new health indicators and enabled participants to think of community health in a positive way and to consider what can be developed. |

| Koo, Chen & Yeh 2020 [38] | Mandala coloring and free form drawing (in group). | 18 community-based learning centers | A randomized controlled study | N = 120 older adults (55–75 years). | 20-min intervention: either a) Mandala coloring group, b) plaid pattern coloring group, c) free-form drawing group, or d) reading group (control). | Sociodemographic, lifestyle, and perceived health status was collected at the baseline. In addition, anxiety levels, measured using the 20-item State-Trait Anxiety Inventory–State Anxiety Scale (STAI-S), were ascertained at the baseline (T1), after a brief anxiety induction (T2), and at the end of the assigned activity (T3). | A significantly lower (P = 0.004) anxiety level was observed only in the mandala coloring group compared with the control group. |

| Lancioni et al. 2011 [48] | Coloring activity versus music listening. | A day center for persons with dementia | A case illustration | N = 1 man (85 years) with severe Alzheimer’s disease, could not speak. | Three daily 10-min sessions: listening to participant’s presumably preferred music or coloring pictures with crayons. | Observations every 10th second, two observers. | Wandering was fairly constant during the baseline condition, but dropped during the coloring and music conditions. |

| Lapum et al., 2012 [52] | Narratives in form of stories and photographic images. | Open heart surgery rehabilitation at preoperative clinic in a regional hospital | A cross-sectional study | N = 16 adult patients (59–85 years). | – | Two interviews and an analytic dissemination method of stories and photos. | Patients’ unique and deeply personal pre-, intra- and postoperative experiences were illuminated, reframing professionals’ conduct |

| Lawson et al. 2012 [54] | Painting tiles (in group). | Cancer center blood marrow transplantation outpatient unit | A crossover design: the same participants complete pre- and post-testing for the control condition and the intervention condition | N = 20 adult (20–68 years) patients in process of blood marrow transplantation. | Participants were provided with a ceramic tile, brushes, and paint to create a tile. Participants were not given instructions about what to paint. | Demographic data form; Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Index, Therapy-Related Symptom Checklist. Salivary cortisol levels both before and 1 h after art making. |

After intervention, participants reported a significant decrease from pre- to post-test in mean scores of therapy-related symptoms but not in anxiety. However, their salivary cortisol levels significantly decreased from pre- to post-test for the intervention and control conditions, which may indicate a decrease in physiologic stress. |

| Lawson et al., 2016 [58] | Painting tiles (in group) or listening to music. | Outpatient Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinic at Cancer Center | A randomized, three-group, pre-/post-pilot design | N = 39 adults (22–74 years) receiving blood and marrow transplantations. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups: a) art making, b) diversional music (comparison), or c) control (usual treatment). | Participants were: a) provided with a ceramic tile, brushes, and paint to create a tile; or b) given a sterilized Apple iPad mini including the Spotify® music mobile application. | The Therapy-Related Symptoms Checklist, the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Index and vital signs, all pre- and postintervention | No statistical differences were found between groups on all measures following the intervention. |

| Leuty et al., 2013 [63] | The Engaging Platform for Art Development computer-based device, consisting of a multi-touch display (screen) mounted on an adjustable wooden easel. Software included a “Therapist Interface” (which an art therapist uses to customize the system for their client) and a “Client Interface” (which an older adult client uses to create his/her artwork). | A health sciences center | A mixed-methods study | N = 6 older adults (mean age 89.2) with dementia and 6 art therapists | Five 1-h trials were held with each therapist and adult, to develop and test the Engaging Platform for Art Development computer-based device. | A pilot test: a questionnaire which measured the Engaging Platform for Art Development device’s usability from the perspectives of therapists and adults. | All participants found the device engaging but did not find the prompts to be effective. |

| Liddle, Parkinson & Sibbritt 2011 [45] | Painting pictures or playing a musical instrument. | Community | A longitudinal cohort study, surveys 2005 and 2008 | N = 5058 women enrolled in the 1921–1926 birth cohort (mean age 84 years). | – | Instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) Memory Complaint Questionnaire (MAC-Q) and Short Form 36 (SF-36) quality of life questionnaire. | Those who stopped painting pictures or playing a musical instrument experienced significant decline in mental health related quality of life while those who started these activities experienced significant improvement in emotional wellbeing. |

| Liddle, Parkinson & Sibbritt 2013 [44] | Painting, drawing, printing, design, sculpture, pottery, ceramics, craft, handicraft, glass work, beading, jewelry, furniture making, woodwork, textiles, sewing, knitting, needlework, quilting, embroidery, patchwork, crochet, photography, video, film. | Community | A longitudinal cohort study | N = 114 elderly women (80–88 years). | – | Postal surveys, in-depth telephone interviews. | The participants found purpose in their lives, contributing to their subjective well-being whilst helping and being appreciated by others. They develop a self-view as enabled, and as such take on new art and craft challenges and continue to learn and develop. |

| Pipe et al., 2010 [50] | A Tree of Life poster. | A general medical ward at a university hospital | A pilot study | N = 15 patients (mean age 73.8 years) with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, stroke, brain injury, spinal stenosis with neurological deficits, hip and knee replacements with comorbidities, amputations, or hip fractures. | A volunteer trainee interviewed participants and made a Tree of Life poster for each participant during the interviews. The volunteer followed patients’ instructions about what information was included and where it went on the poster. | Pre- and postintervention measures: Linear Analogue Self-Assessment (LASA) Instrument, Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support Survey, Herth Hope Index (HHI), Expanded Version of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp-Ex). | Ten (67%) patients reported the intervention positively affected their quality of life. Improvements were noted in overall quality of life (P = 0.05), as well as emotional (P = 0.005), physical (P = 0.02) and spiritual well-being. The Tree of Life poster provided an adjunct to the typical hospital room scenario whereby patients could communicate the meaningful aspects they wanted to share with staff. It also made it possible to relay these details only once, rather than repeating the same story with multiple staff members. |

| Poulos et al., 2019 [39] | Visual arts, photography, dance and movement, drama, singing, music (in group). | Community: arts on prescription | A program evaluation | N = 127 adults (>65 years) with diverse health and wellness needs. | Weekly workshops for 8–10 weeks. | Pre- and postprogram questionnaires, the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS), and focus groups and individual interviews. | There was a statistically significant increase in WEMWBS scores between baseline and postprogram. The mean increase was 6.86 (95% CI: 5.33–8.38) points on a paired samples t-test (t = 8.91, df = 104, P < 0.001). Qualitative findings indicated that the program provided challenging artistic activities that created a sense of purpose and direction, enabled personal growth and achievement, and empowered participants, in a setting which fostered the development of meaningful relationships with others. |

| Scott et al., 2015 [59] | Drawing one’s melanoma prior to health care. | Skin clinics at two regional hospitals | Part of a semi-structured, face-to-face in-depth interview study, with details described elsewhere | N = 63 adults (29–93 years); patients with melanoma. | – | In-depth interviews within 10 weeks of diagnosis. Participants were asked to draw a picture of what they remembered their melanoma to look like when they first noticed it and as it developed, up until the time of diagnosis. | Asking patients to make drawings of their melanoma appears to be an acceptable, inclusive, feasible and insightful methodological tool. |

| Shimura et al., 2012 [64] | Paintings. | – | A case study | N = 1 (68 years). | – | Observations of a semiprofessional painter with Parkinson’s Disease. | The participant’s style changed dramatically, from abstract to realism, about a year before the appearance of classic Parkinsonian symptoms. |

| Schindler et al. 2017 [61] | Experimented with different materials, colors, and techniques. | Department of Neurology, University Hospital and a community | A randomized intervention study with a pre-post follow-up design | N = 113 adults (mean age 52): subgroups were visual art production or cognitive art evaluation, where the participants. either produced or evaluated art | 10 weeks, one session weekly. | The Symbol-Digit Test and the Stick Test. | Mental stimulation by participation in art classes leads to an improvement in processing speed and visuo-spatial cognition. |

| Stevenson & Orr 2013 [56] | Pencils, crayons, pastels and charcoal can be used for individuals who prefer to use more controlled materials, whereas modified paintbrushes, paper for collages and clay can be introduced for people with limited dexterity. Furthermore, for a resident whose sight is limited, textured paint and fabrics can be explored. | A residential care home | A theoretical paper | Older adults (The sample size is not specified). | – | – | Art making for older adults in a care home can be used for a variety of reasons: Exploring creativity, Providing an alternative way of communicating, Communicating issues that may be difficult or confusing, Expressing feelings of anxiety or depression, Exploring grief or loss, Recalling important life events and memories, Considering changes in personal circumstances, Aiding relaxation, Reducing isolation, and Socializing. |

| Van de Venter & Buller 2014 [43] | Painting, textiles, music, photography and film (in group). | Arts-on-referral: Inner-city GP practices and community centers | A pre-and-post intervention mixed-methods study | N = 44 adults with mild-to-moderate mental health problems. | A 20-week intervention with an artist-facilitation. | Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) pre- and post-intervention, individual semi-structured interviews. | Mean well-being scores improved by 8.0 (P = 0.0001). Participants from Black and Minority Ethnic groups and females appeared to show greater improvement in well-being scores than White British or male participants. Sharing experiences reduced social isolation and external stressors. |

The type of art making varied: drawing, painting, coloring, mosaic, sculpture, ballet, drama or furniture making (Table 1). In some papers, art making was considered a narrative (for example, [47,[50], [51], [52], [53]]), while in other papers (for example, [39,46,49]) a narrative was produced as a complement to art making. In most papers, participants themselves chose the type of art making, but in some papers a pre-delineated art making scheme was seen. In some papers, the art making context and type of health problem were seen to influence the choice of art making materials [48,[54], [55], [56]].

Art making was described either as part of preventive health care on the individual level (for example, [42]) or group level (for example, 38); or as a means for therapeutic nursing care. Art making was linked to the co-creation of new health indicators and community health [41], alleviating anxiety [38], and the improvement of emotional well-being [44,45], mental health [39,40,42] and personal growth [39,44].

In most papers, art making was described as a means for therapeutic nursing care, seen in various contexts and settings: specialized hospital mental care [43], pain care [57], oncologic care [[58], [59], [60]], neurologic care [61] rehabilitation [50,52,53], long-term elderly care (for example, [47,51,55,56,62]) and dementia care (for example, [48,49,63]). Art making was used as an assistive means in diagnosing Parkinson’s disease retroactively [64], a somatoform-functional pain disorder [57] and melanoma [59]. Within nursing care, art making activities were linked to outcomes (Table 2) such as acknowledgement of own unique experiences [52,56] or strengths [51], better communication of own experiences and strengths with professionals [50], heightened self-esteem [46,62], involvement in activity [53,55], less wandering for a person with dementia [48], and improvements in human connectivity [39] and social inclusion [49,56]. Also, enhancement of own cognitive capacities [49,61], perceived lower anxiety [38], less physiologic stress [58], more positive emotions [60], improved mental well-being [43] and overall quality of life [49,50] were seen.

Table 2.

Outcomes of art making activities.

| Art making activities | Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Listening to music | Less wandering for a person with dementia [48] In group: Mental well-being [43] |

| Coloring | Less wandering in dementia [48] In group: Lower anxiety [38] |

| Modelling clay | Enhancement of own cognitive capacities [61] Together with a near-one: Enhancement of own cognitive capacities [49] Social inclusion [56] Together with a near-one: Social inclusion [49) Together with a near-one: Quality of life [49] |

| Singing | In group: Mental health [39] In group: Personal growth [39] In group: Human connectivity [39] |

| Dancing, moving | Mental health [40], In group [39]: In group: Personal growth [39] In group: Social inclusion [39] In group: Social interaction [47] |

| Taking photography | Emotional well-being [44] Acknowledgement of own unique experiences [52] Personal growth [44] In group: Personal growth [39] Social inclusion [56] In group: Mental well-being [43] In group: Mental health [39] |

| Playing an instrument, making music | Emotional well-being [45] In group: Mental health [39] In group: Personal growth [39] In group: Social inclusion [39] |

| Drawing | Together with a near-one: Enhancement of own cognitive capacities [49] In group: Lower anxiety [38] Emotional well-being [44] In group: Mental health [40] Personal growth [44] Acknowledgement of own unique experiences [56] Together with a near-one: Social inclusion [49,56] Together with a near-one: Quality of life [49] |

| Painting | Enhancement of own cognitive capacities [61] Together with a near-one: Enhancement of own cognitive capacities 49] Acknowledgement of one’s unique experiences [56] Involvement in activity [53, 55 In group: Less physiologic stress [54] Emotional well-being [44] In group: Mental well-being [43] Mental health [42] In group: Mental health [39,40] In group: Personal growth [40] Social inclusion [56] Together with a near-one: Social inclusion [49] Together with a near-one: Quality of life [49] An assistive means in diagnosing [64] |

| Making a collage | Together with a near-one: Enhancement of own cognitive capacities [49] Together with a near-one: Social inclusion [49] Together with a near-one: Quality of life [49] |

| Writing, poetry | Mental health [42] In group: Mental health [40] Together with a near-one: Social inclusion [49] |

| Making a video or film | In group: Mental well-being [43] Personal growth [44] Together with a near-one: Quality of life [49] |

| Crafting∗ | In group: Mental health [40] Personal growth [44] |

| Cultural animation | In group: Co-creating new health indicators and community health [41] |

| Zine making | Acknowledgement of own strengths [51] |

| Narrative∗∗ | Acknowledgement of one’s unique experiences [52,56] Involvement in activity [53,55] Positive emotions [60] Heightened self-esteem [46,62] Quality of life [50] Together with a near-one: Quality of life [49] Better communication of own experiences and strengths with professionals [50] An assistive means in diagnosing [57,59] |

| Drama | In group: Personal growth [40] In group: Social inclusion [40] |

Sculpture, pottery, ceramics, glass work, beading, jewelry, furniture making, woodwork, textiles, sewing, knitting, needlework, quilting, embroidery, patchwork, crochet.

Drawing an image of oneself, auto-photography and drawings, drawings on the theme of “my cancer”, a tree of life poster, marking one’s pain on a pre-printed body diagram, drawing one’s melanoma prior to health care.

Information on art making activities in relation to preferred outcomes in the papers was dependent on research design and methodological rigor. Most papers were cross-sectional, did not include a control group, and had rather small sample sizes. The interventions, if described, were seen to vary in length from 20 min to 20 weeks and were not always fully described. Nevertheless, there were three randomized controlled studies and three longitudinal studies, and in most studies validated instruments were used during data collection, with or without qualitative methods.

5.2. Expressive art therapy in health and nursing care

Expressive art therapy was described in 15 papers (Table 3), in contexts ranging from community centers [[65], [66], [67], [68]], projects for the homeless [69] and immigrants [68] to more clinical contexts: cancer care [70,71], dementia care [72,73], psychiatric care [74,75] and hospice care [76,77]. Professional art therapists were responsible for the art therapy sessions, and researchers were seen to be involved data collectors. Most participants were elderly, usually over 70 years. In 11 papers, the expressive art therapy activities were organized in groups, despite the possible vulnerability of participants in certain contexts due to illness. In one paper, the person involved could not speak [72]. There were no papers in which the patients’ near-ones or health and nursing care professionals were involved in expressive art therapy.

Table 3.

Type of expressive art therapy activity, research details and outcomes/conclusions, in health and nursing care between 2010 and 2020 (in alphabetic order, by author name; n = 15 papers).

| Authors | Type of expressive art therapy activity | Context | Research design | Sample | Intervention | Method(s) of data collection | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alders & Levine-Madori 2010 [68] | Group therapy: music, guided imagery, painting, movement, poetry, sculpture, photography, themed discussion. | A community center for immigrants | A pilot experiment | N = 24 adult immigrants (mean age 75 years) | 10-week intervention. Participants had the choice of attending a 2-h weekly art therapy session or one of five other activities. | Demographic data, pre- and posttest with the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire and the Clock Drawing Test. | Participants who attended the art therapy sessions outperformed those who did not on both cognitive evaluation tests. |

| Blomdahl et al., 2018 [74] | Group therapy: narratives, exploration of art media, drawings, colorings, relaxation exercises. | Two clinics from general care and two clinics from specialist psychiatric outpatient care | Randomized controlled trial according to the CONSORT recommendations for nonpharmacological treatment |

N = 79 adults (18–65 years). 43 Individuals with moderate to severe depression (usual treatment and art therapy). 36 in control group, treatment as usual. |

10-week intervention. 1-hour weekly sessions. The art-making was based on the participants’ own preferences. | Sociodemographic data, Montgomery-Åsberg depression rating scale (MADRS-S). | The intervention group showed a significant decrease of depression levels and returned to work to a higher degree than the control. Self-esteem significantly improved in both groups. Suicide ideation was unaffected. |

| Buday 2013 [76] | Drawings and paintings. | Hospice | A case illustration | N = 1 female (78 years) | 10-month intervention. 34 sessions with an art therapist. | Noty specified | Gaining self-empowerment through the engagement of making art and reflecting on the resulting product; and offering a non-threatening means to explore thoughts and feelings. |

| Ciasca et al., 2018 [75] | Group therapy: guided imagery, painting, drawing, clay modeling, weaving, and collage. | A psychiatric institute in a university hospital | Randomized controlled trial |

N = 56 outpatients with depression, (70 years). 25 in intervention group, 31 in control group |

20-week intervention. 90-minute weekly workshops. | Sociodemographic questionnaire and pre- and posttests with the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and cognitive measures (Mini Mental State Examination). | The art therapy intervention for elderly women with stable, pharmacologically treated depression led to improvement in depression (P = 0.007) and anxiety symptoms (P = 0.032). |

| Guay 2018 [78] | Group therapy: drawing, painting, modeling, sculpturing. | A communication program for brain injury survivors | A pre-experimental comparison group study |

N = 19 adult (29–93 years) individuals with brain injury. 11 in art therapy group, 8 in communication skills group |

10-week program, based on the participants’ own interests. 90-minute sessions compensatory communication strategies (15 min), engagement in art making (45–60 min), and group sharing about the meaning of the artwork using compensatory strategies for communication (15–30 min). | Pre- and postmeasures with a partial Assessment for Living with Aphasia and Art Therapy Perception (ATP) questionnaire. | Results from pre- and postmeasures did not show statistically significant between-group differences. However, the participants found art therapy to be a new way to express their thoughts and feelings, and appeared to reduce their levels of stress and anxiety. The group art therapy sessions created a new venue for socializing and establishing deeper, more meaningful friendships. Group art therapy seemed to build up the participants’ self-confidence. |

| Ilali et al., 2019 [79] | Group therapy: drawings as narratives. | A day center for elderly adults | A randomized controlled study | N = 54 older adults (age > 60). 27 in interventions group, 27 in control group | 6-week intervention. 60-minute weekly group sessions. | Pre- and posttests with the Abbreviated Mental Test and the Short Geriatric Depression Scale. | Symptoms of depression appear to have decreased in the experimental group following the 6-week course of drawing based on life review. For the control group, a rising trend in depression scores was found. |

| Lee et al., 2017 [70] | Group therapy: famous painting appreciation, delivered in odd numbered sessions (i.e., sessions 1, 3, 5, and 7), and creative artwork generation, delivered in even numbered sessions (i.e., session 2, 4, 6, and 8). | An outpatient clinic at the Department of Radiation Oncology | A prospective, single-arm trial | N = 20 adult (32–79 years) cancer patients receiving radiotherapy | 4-week intervention. Participants underwent eight 30-min art therapy sessions during radiotherapy, i.e., 2 sessions per week. | One-on-one interviews between trained therapists and patients, individual questionnaires before, during, and after radiotherapy: the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS, The Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS.) | This form of art therapy led to improvement or maintenance of cancer-related distress compared to baseline among patients throughout their treatment and significant reductions in the prevalence of severe depression and anxiety. The ESAS scores showed no improvement. |

| Mahendran et al., 2018 [65] | Group therapy: Guided viewing and cognitive evaluation of art works at the respective sites was conducted as a group activity by trained staff and involved narration of thoughts and inner experiences. A second component involved visual art production. | Community | A randomized controlled trial | N = 46 (mean age 71). 22 in intervention group, 24 in control group | 9-month intervention. Weekly art therapy or music listening. | The Rey auditory verbal learning test (RAVLT; memory test including list learning, delayed recall and recognition), Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-3rd edition (WAIS-III), Block design (visuospatial abilities), Digit Span Forward (attention and working memory), and Color Trails Test 2 (Executive function), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Geriatric Anxiety Inventory (GAI), and a 100-point Visual Analog Scale (VAS; sleep quality). | Art therapy had more significant effects than music with improvements in memory, attention, visuo-spatial abilities and executive function at 3 months and which was sustained in the memory domain at 9 months. |

| Monti et al., 2013 [71] | Expressive art tasks (drawing a picture of their self, awareness of sensory stimuli, imaging self-care, art production to foster mindfulness, creating stressful and pleasant event pictures, and free expression) with mindfulness exercises. | One university’s cancer center | A randomized two-group controlled intervention study | N = 191 patients with breast cancer (mean age 56,9). 98 in intervention group, 93 in control group | 8-week intervention. Either mindfulness-based art therapy (MBAT) intervention or a breast cancer educational support program. | The Symptoms Checklist-90-Revised, the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey at baseline; immediately post-intervention and at 6 months. | Results showed overall significant improvements in psychosocial stress and quality of life in both the MBAT and educational support groups immediately post-intervention; however, participants with high stress levels at baseline had significantly improved overall outcomes only in the MBAT group, both immediately post-intervention and at 6 months. |

| Moxley et al., 2011 [69] | Group therapy: quilting one’s story with a precut cotton square and an assortment of materials (e.g., pieces of colored fabric, felt, markers, beads, fringe, ribbon, etc.), then presenting it. | Leaving Homelessness Intervention Research Project | A cross-sectional study | N = 20 older African American homeless women | Two workshops | Two investigators’ observations and notes, a focus group interview. | Creating the quilt, e.g., pushing and pulling a needle through fabric, making decisions about design, ripping apart and starting over. Transforming a destructive experience into something constructive seemed to be a metaphor for the women’s progress in finding and maintaining housing and in their growing self-efficacy. |

| Pike 2013 [66] | Group therapy: collage, autobiographical timeline, coloring mandalas, installations. | A community center, a retirement center, an adult daycare, an assisted living facility, and a skilled nursing facility | A controlled intervention study with matching groups | N = 91 older adults. 54 (mean age 78 years) in intervention group, 37 (mean age 76 years) in control group | 10-week intervention. Weekly group sessions. | Pre- and posttest with the Clock Drawing Test, the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ). | A t-test and univariate linear regression, with a medium effect size (d = .064), indicated that the art therapy treatment was associated with significantly improved cognitive performance. Other findings suggest that session duration and art therapy approach significantly correlated with improved cognitive performance. |

| Safrai 2013 [77] | Painting and collage sessions. | Hospice care | A case illustration | N = 1 male, 71 years of age | 2-month intervention. Twenty-two semiweekly sessions with an art therapist. | Discussion. | Painting with an art therapist allowed the patient to shift from a state of anxiety and existential dread to a more accepting, fluid awareness of the dying process. Additional benefits to the patient included improved quality of life, self-expression, and meaning making, as well as an increased ability to relate to the art therapist and to connect with family members and staff. |

| Stephenson 2013 [67] | Group therapy: drawing, painting, work in clay, printmaking, Chinese brush painting, collage. | A community art therapy program | A project description | N = 70 residents of a large cooperative housing complex (58–99 years) | Two weekly sessions. | Observations of diverse participant interactions in the nondirective therapy studio over the course of 6 years. | A community art therapy program can a) foster artistic identity, b) activate a sense of purpose and motivation through creative work, c) use art as a bridge to connect with others, and d) support movement toward the attainment of gerotranscendence. |

| Tucknott-Cohen & Ehresman 2016 [72] | Thick artist paper, outlined mandalas, pens, pencil crayons, and bingo magic markers. | Alzheimer care in a long-term care home | A case illustration | N = 1 female (>80 years) with advanced dementia, vocalizing with noises instead of words | 17-week intervention. Individual 45-min therapy weekly. | After each session, the art therapist photographed the art and wrote summaries and annotations. | The treatment concerns that arose, altered view of reality, agitation, and retrogenesis provide insight on the use of art in dementia care for increasing the individual’s overall quality of life. |

| Woolhiser Stallings 2010 [73] | Collage and writing. | A care center for persons with dementia | A qualitative study | N = 3 females with dementia (70–80 years) | Two individual art therapy sessions per person. | A modified Magazine Photo Collage assessment. | A collage allows older adults with dementia an opportunity to convey information that they might not be fully capable of verbalizing. |

The type of expressive art therapy activity varied greatly: among others, music, guided imagery, coloring, sculpture, famous painting appreciation, quilting (Table 3). In all papers, the various activities were combined in accordance with how expressive art therapy was defined. For example, in some papers, narratives were considered an implicit part of the expressive art therapy process [65,68,69,73,74] while in other papers a narrative was produced as a complement to art making. In some papers, participants could choose between art therapy activities according to own preferences (for example, 74) but in others a pre-delineated therapy program (for example, 78) or art making scheme was seen.

Expressive art therapy activities were linked to outcomes (Table 4) such as improved cognitive skills [65,66,68], self-esteem [74,78], connection with others such as family members and staff [67,77,78], self-expression [73,77,78], self-empowerment [76], quality of life [71,72,77], and self-efficacy [69], and decrease in depression [70,74,75,79], anxiety [70,75,78] and psychosocial stress [71].

Table 4.

Outcomes of expressive art therapy activities.

| Expressive art therapy activities | Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Listening to music | Improved cognitive skills [68] |

| Guided imagery | Improved cognitive skills [68] Decrease in depression [75] Decrease in anxiety [ [75] |

| Guided viewing of artworks | Improved cognitive skills [65] Decrease of depression level [70] Decrease of anxiety [70] |

| Coloring | Improved cognitive skills [66] Improved self-esteem [74] Decrease of depression level [74] |

| Clay modeling | Improved self-expression [78] Improved self-esteem [78] Decrease in depression [75] Decrease in anxiety [78] Improved connection with others such as family members and staff [67,78] |

| Drawing | Improved self-expression [78] Individual therapy: improved self-expression [73,77] Improved cognitive skills [65] improved self-esteem [78] Self-empowerment [76] Decrease in depression [74,75] Decrease in anxiety [70,74,75] Decreased in psychosocial stress [71] Connection with others such as family members and staff [67,78] Individual therapy: Connection with others such as family members and staff [77,78] Individual therapy: Quality of life [72] |

| Painting | Improved self-expression [78] Improved cognitive skills [65] Improved self-esteem [78] Self-empowerment [76] Decrease in anxiety [70,75,78] Connection with others such as family members and staff [67,78] Individual therapy: Connection with others such as family members and staff [77] Individual therapy [77]: |

| Photography | Improved cognitive skills [68] |

| Collage | Individual therapy: Improved self-expression [73,77] Improved cognitive skills [66] Decrease in depression [75] Decrease in anxiety [75] Connection with others such as family members and staff [67] Individual therapy: Connection with others such as family members and staff [77] Individual therapy: Quality of life [77] |

| Movement | Improved cognitive skills [68] |

| Sculpturing | Improved self-expression [78] Improved cognitive skills [68] Improved self-esteem [78] Decrease in anxiety [78] Connection with others such as family members and staff [78] |

| Weaving | Decrease in depression [75] Decrease in anxiety [75] |

| Writing, poetry | Improved cognitive skills [68] |

| Narrative∗ | Improved cognitive skills [66] Improved self-esteem [74] Improved self-efficacy [69] Decrease in depression [70,74] Individual therapy: Decreased psychosocial stress [71] Individual therapy: Quality of life [71] |

Note: ∗Drawing an autobiographical timeline, quilting one’s story, drawing a picture of oneself.

Information on expressive art therapy activities in relation to preferred outcomes in the papers was dependent on research design and methodological rigor. There were five randomized controlled studies and one controlled intervention study, but also three case illustrations and some project descriptions. The interventions were seen to vary in length from one session to 20 weeks, and the sample sizes were small. In about half of the papers, validated instruments were used during data collection. However, there were also several papers in which observations or field notes were used as the main data collection method, and these did not include systematic explanations of how the data were analyzed.

5.3. Outcomes of art making or expressive art therapy activities in health and nursing care

While the outcomes linked to art making and expressive art therapy activities in adult health and nursing care are briefly described in sections 5.1 and 5.2 above, a synthesis of the stated relationships between the different types of activities and outcomes also occurred. The activities are listed in order from passive to more active engagement (Table 2, Table 4).

Little difference was seen between the activities included in art making and expressive art therapy activities. With few exceptions, such as singing, crafting, making videos and drama (art making) and guided imagery and viewing of artworks (expressive art therapy), all other activities were the same.

The outcomes of art making activities (Table 2) for individuals were linked to, for example, acknowledgement of own unique experiences and own strengths, personal growth, emotional well-being, heightened self-esteem and better communication of own experiences and strengths with professionals. The outcomes of art making activities in group were linked to the development of cognitive capacities (possibly), mental well-being, social inclusion and quality of life.

As seen in 11 out of 15 papers, expressive art therapy activities primarily took place in groups. The outcomes of expressive art therapy activities in group (Table 4) were linked to a decrease in certain symptoms such as psychosocial stress, anxiety or depression; or improved self-esteem, self-expression, self-empowerment and connection with others.

Outcomes linked to art making appear to encompass prevention, while outcomes linked to expressive art therapy appear to encompass the care and cure of already existing signs of health problems. Nonetheless, very similar goals, methods and outcomes for both methods were seen. Therefore, it is not relevant to state any relationships between certain health problems and the specific outcomes of art activities.

6. Discussion and conclusions

The aim of this scoping review was to describe the existing knowledge on art making and expressive art therapy in adult health and nursing care. From the 42 studies and other papers included here, published between 2010 and 2020, one sees that both art making and expressive art therapy are used on the community level in preventive health care and rehabilitation, as well as in hospitals and other care institutions in specialized nursing care and cure. In other words, the art activities were offered for both healthy individuals as part of community projects and for chronically or terminally ill residents, with activities for such participants occurring outside of the home setting (see Ref. [10]) and no acute patients being seen (see Ref. [2]). While this is understandable, because of the perceived challenges associated with organizing art activities in a home setting and the nature of acute health problems, art activities can nonetheless easily be organized in such a setting. Individuals can involve themselves in crafting or other art making activities in the home using independent virtual or digital devices. Researchers have shown that acute patients benefit from receptive art engagement in the form of paintings or music (see Ref. [4]), even if they are not willing or actively able to make art during an acute health problem. The art activities seen here were mainly organized as part of research or general projects, not as systematic health or nursing care interventions, even though most art activity types can be undertaken alone without any special skills and/or significant material investments. However, the context of art making and type of health problem influence the choice of art making type and materials [48,[54], [55], [56]]. For example, patients with tendency to eat whatever they get into their hands (certain psychiatric conditions, deep dementia) or with risk to other kind of self-harm or aggression such as wounding cannot work with scissors or participate into crafting activities such as quilting, embroidery, needlework, leatherwork, woodwork, copper-tooling or metalcraft – at least not in group and without supervision.

Activation appeared to be one objective underlying the implementation of art activities. Usually organized in a group, art activities were seen to improve acknowledgement of own experiences, strengths and self-esteem; lead to better communication of own experiences and strengths with professionals; and improve perception of well-being or health on the psychological, physiological and social levels and quality of life. Another underlying objective appeared to the facilitation of the coping with and adapting to age-related transitions such as retirement, decrease of mobility, cognitive decline or move from own home to a nursing home. This was seen as support during an emotional crisis such as immigration, incarceration, homelessness or hospice care; facilitating coping with psychological and physical symptoms; or support during or after a health crisis such as depression, brain injury, cancer, chronic pain, open heart or hip replacement surgery. These results are in accordance with earlier research results (see Ref. [3,4,8,18]) and the definition of expressive art therapy (see Ref. [9]). Nursing goals and outcomes can be related to art activity outcomes, measured through observations of patients’ art activities and narratives linked to such activities.

Art activities were linked not only to acknowledging and building new strengths and skills, making meaning of experiences, and personal growth but also the establishment of clinical diagnosis, symptom alleviation, and communication, whereby collaboration with near ones and health care professionals was fostered. Art activities should become an essential part of health and nursing care, because they were seen to be beneficial in nearly every context: prevention, rehabilitation, care, cure and palliation. They were furthermore seen to promote person-centeredness, whether organized for individuals or in group.

Health care professionals should be encouraged to use art activities intentionally to get to know each person and his/her experiences, because the meaning of the person’s experiences is a vital part of evidence-based nursing art and person-centered care (see 26, 27, 28, 30). To achieve mutual understanding of both perceived symptoms, problems, needs, strengths and areas of satisfaction, nurses should encourage patients’ narratives and/or other creative expressions (see 3). Art making and/or expressive art therapy can also be used to address complex challenges (see 2), such as pandemics. For example, what are individuals, groups, nurses, patients, and near-ones experiencing during this most recent COVID19 pandemic? How could nursing education, health care organization and management be further developed, emanating from these experiences? In the data seen here, most participants were adults, aged 65 years or older. In most papers, even if the type of health problem has an impact on choice of safe art making materials, the participants themselves chose the preferred art activity, which is a motivating and truly person-centered act [2,15,22,[31], [32], [33]]. Still, patients’ near-ones were involved in art making in only one paper [49], and a member of the professional team made art emanating from the patient’s narrative in only one paper [50]. No papers describing collaborative patient-professional art making or health care professional art making were seen (see 4, 13). Also, the professional responsible for the art making was not always explicitly described, nor the involvement/role of researcher/s.

These results are partly contrary to recommendations on the use of art in health care. Engagement in art activities is linked to the engagement of patients’ near-ones in person-centered care and the idea of sustainable methods whereby to promote the well-being of healthcare professionals; among other things, art activities have been shown to improve the mental health and well-being of personnel and reduce stress and burnout [4]. There may be a lack of information about the importance of and possibility to include patients’ near-ones and health care professionals in art activities. Through more knowledge and understanding of the types and outcomes of art activities, health care personnel can inform patients, patients’ near-ones and members of interprofessional teams about the importance of active art making and make what is seemingly currently “extraordinary” a more ordinary, implicit part of care. How health care personnel can facilitate art making should be included in health care professional curricula or offered as further education. In this data there was no evidence of such; neither in health care personnel education - nor patient education (see 12, 20).

If health care personnel do not have time for art activities as part of their professional interventions, professional art therapists could be employed. However, if there is no need for professional therapy, the use of professional therapists can be considered an unnecessary barrier between the nurse and patient. Giving nurses the opportunity to incorporate art activities into their evidence-based, professional nursing interventions would promote an active nursing role and a creative, person-centered way of working. Moreover, a variety of artists, writing coaches or actors could be included not only in interprofessional health care and nursing teams but also in care for health care personnel, which could help facilitate sustainable creativity.

Further randomized controlled trials in which the use of art making or expressive art therapy are investigated in relation to their effects on the nurse-patient relationship, the patient-near-one relationship, person-centeredness, clinical and other outcomes are needed. This can help ensure that art activities and narratives emerging from such activities become an effective means for the realization of person-centered preventive health care, nursing care and cure, nursing education and sustainable care for health care personnel. Also, health care professionals’ knowledge of, skills and attitudes toward art activities should be investigated, alongside measurement of art activity outcomes over a longer period of time and broader samples, in which participant life situation, education, cognitive and motoric capacities are explored. Lastly, more male participants and participants from different ethnic backgrounds are needed.

This review has some limitations. The data search was conducted by one author, and there is no registered review protocol, only manual documentation of the search process. The search yielded in 117 papers of which 31 were not available in full- text without economic investment. However, all the abstracts were read through properly by all authors and we are convinced that if we would have purchased those papers the main results of this scoping review would not have altered. The data charting and extraction were conducted by the entire research group. Some data in the papers reviewed were not always explicitly reported: the art making or expressive art therapy intervention, health care professionals’ and/or researchers’ role, the data analysis process. Also, sample sizes were smallish and the availability of follow-up data on the long-term effects of art activities was limited.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Heli Vaartio-Rajalin: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Visualization, Formal Analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Supervision. Regina Santamäki-Fischer: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Validation, Writing - Review & Editing. Pamela Jokisalo: Data Curation, Validation, Writing - Review & Editing. Lisbeth Fagerström: Validation, Writing - Review & Editing.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Nursing Association.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.09.011.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Blomqvist L., Pitkälä K., Routasalo P. Images of loneliness: using art as an educational method in professional training. J Cont Educ Nurs. 2007;38(2):89–93. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20070301-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO regional office for Europe Fact sheet - what is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being in the WHO European Region? 2019. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/412535/WHO_2pp_Arts_Factsheet_v6a.pdf?ua=1 [PubMed]

- 3.Cohen G.D. Age Arts; 2006. Research on creativity and aging: the positive impact of the arts on health and illness; pp. 7–14. Spring. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Regional Office for Europe Intersectional action: art, health and well-being. 2019. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/413016/Intersectoral-action-between-the-arts-and-health-v2.pdf?ua=1 2019b.

- 5.McManus I.C., Furnham A. Aesthetic activities and aesthetic attitudes: influences of education, background and personality on interest and involvement in the arts. Br J Psychol. 2006;97:555–587. doi: 10.1348/000712606X101088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noice T., Noice H., Kramer A.F. Participatory arts for older adults: a review of benefits and challenges. Gerontol. 2014;54(5):741–753. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephenson R.C. Promoting self-expression through art therapy. Gener. 2006:24–26. Spring. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips L.J., Conn V.S. The relevance of creative expression interventions to person-centered care. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2009;2(3):151–152. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20090527-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knill P.K., Levine S.K., Levine E.G. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; London: 2014. Principles and practice of expressive arts therapy: toward a therapeutic aesthetics. [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacPherson S., Bird M., Andersson K., Davis T., Blair A. An art gallery access programme for people with dementia: ‘you do it for the moment’. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(5):744–752. doi: 10.1080/13607860902918207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendez M.F., Perryman K.M. Disrupted facial empathy in drawings from artists with frontotemporal dementia. Neurocase. 2003;9(1):44–50. doi: 10.1076/neur.9.1.44.14375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kagan S.H. Using story and art to improve education for older patients and their caregivers. Geriatr Nurs. 2017;39:119–121. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horhagen S., Josephsson S., Alsaker S. The use of craft activities as an occupational therapy treatment modality in Norway during 1952–1960. Occup Ther Int. 2007;14(1):42–56. doi: 10.1002/oti.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]