Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB), which is a frequent and important infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, has resulted in an extremely high burden of morbidity and mortality. The importance of intestinal dysbacteriosis in regulating host immunity has been implicated in TB, and accumulating evidence suggests that microRNAs (miRNAs) might act as a key mediator in maintaining intestinal homeostasis through signaling networks. However, the involvement of miRNA in gut microbiota, TB and the host immune system remains unknown. Here we showed that intestinal dysbacteriosis increases the susceptibility to TB and remotely increased the expression of miR-21 in lung. Systemic antagonism of miR-21 enhanced IFN-γ production and further conferred immune protection against TB. Molecular experiments further indicated that miR-21a-3p could specifically target IFN-γ mRNA. These findings revealed regulatory pathways implicating intestinal dysbacteriosis induced-susceptibility to TB: intestinal dysbiosis→lung miRNA→targeting IFN-γ→impaired anti-TB immunity. This study also suggested that deregulated miRNAs by commensal bacteria could become promising targets as TB therapeutics.

Keywords: commensal bacteria, miRNA, tuberculosis, IFN-γ, Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis), the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB), infects one-third of the world population and leads to high morbidity and mortality (Dickson et al., 2016). Clinical options available to combat TB include chemotherapeutic agents and the preventative vaccine Mycobacterium Bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) which has been undermined due to the broad emergence of drug-resistant strains of M. tuberculosis (Dheda et al., 2014), insufficient protection of BCG efficacy against pulmonary TB in adolescents and adults (Colditz et al., 1994) as well as HIV-1 co-infection. Developing new strategies against tuberculosis such as a better vaccine or a host-directed therapy can be aided by the increasing understanding of the immune responses against M. tuberculosis infection (Kaufmann, 2006; Bhatt and Salgame, 2007; Kaufmann et al., 2010).

Microbial community inhabits the skin, the oral, pulmonary, urogenital and gastrointestinal (GI) tract, with the GI tract having the highest density of microorganisms. The gut microbiota plays a vital role in shaping and modulating systemic immune response (Kosiewicz et al., 2011; Schirmer et al., 2016). Given the diverse functional repertoire of the gut microbiota, it is not surprising that several human disorders were reported to be associated with dysbiosis of the resident microbiota (Iida et al., 2013; Tang et al., 2013, 2017; Vetizou et al., 2015; Paun et al., 2016; Sampson et al., 2016). Moreover, accumulating evidence indicates that gut microbiota dysbiosis also provokes susceptibility to infectious diseases. It advocates the importance of commensal bacteria to host health as commensal microbes can calibrate innate and adaptive immune responses and impact the activation threshold for pathogenic stimulations (Ivanov and Honda, 2012). For example, treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics decreased TNF-α and IFN-γ production by CD8 + T cells and therefore compromised anti-viral immunity during influenza infection (Abt et al., 2012).

Recently, accumulating studies started to address the relationship between gut microbiota and lung disorders, which referred as the “gut-lung axis” (Marsland et al., 2015). It has been suggested that surviving bacteria, metabolites produced by gut bacteria or other factors may travel along the mesenteric lymphatic system to the circulatory system and subsequently enter pulmonary circulation, which may lead to the local activation of immune responses (Bradley et al., 2017). Numbers of examples reported alternations in the composition of the human microbiome during M. tuberculosis infection both in patients and in animal models (Winglee et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2019), and interaction between commensal microbiota and the host immune system to the pathogens. IFN-γ producing CD4 + T cells provide the major effector response to TB and IFN-γ is required for protection against disease progression in TB (Flynn et al., 1993). Based on the gut-lung axis theory, it is not surprising that there may be some stimuli that can originate in the gut, explaining the underlying mechanisms of resident microbiota regulating IFN-γ expression during TB infection.

MiRNAs are small non-coding RNAs that act as post-transcriptional regulators of mRNA by targeting specific RNAs for destruction or by repressing their translation (Kim et al., 2017). Recent researches had reported the regulation of cytokine production and function by miRNA (Ma et al., 2011). MicroRNA-21 (miR-21) has been identified as one of the most highly expressed miRNAs in various tumors (Pan et al., 2010) and has several reported functions that may impact the disease, including roles in both innate and adaptive immunity. In particular, miR-21 has been shown to modulate the responses of macrophages to bacterially derived Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists including LPS. MiR-21 was also shown to be involved in inflammatory responses and regulate the immune responses by targeting programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4) (Frankel et al., 2008). Furthermore, Lu et al. (2011) also revealed that miR-21 can be induced in the lung of multiple asthma models and regulates lung eosinophilia, theTh1/Th2 balance and the prognosis for asthma. While the impact of bacterial pathogens in miRNA expression profile has been subjected to intensive investigation, our knowledge about the function of miRNAs in the GI tract is still very limited, especially about the mechanism by which and how miRNAs regulate gene expressions of inflammatory signaling such as IFN-γ.

An increasing number of studies indicate that miRNAs showed different expression patterns when the gut microbiota was altered and that differentiated miRNAs might contribute to shaping the interaction between the host and gut microbiota (Dalmasso et al., 2011a; Liu et al., 2016). In addition, germ-free (GF) and antibiotic-treated mice had significantly more fecal miRNA compared to controls associated with specific pathogen-free (SPF) microbiota, suggesting that gut microbes contribute to a specific miRNA signature. For example, Singh et al. (2012) identified 16 miRNAs that were differentially expressed in the cecum of GF and SPF mice. Their results further demonstrated that the targets of these miRNAs were genes that maintain the intestinal barrier. Another example is miR-107, previously reported to promote metastasis in colorectal cancer was differentially expressed in the cecum of GF mice compared to SPF mice (Xue et al., 2014). Therefore, these studies provide clues that the microbiota regulates host gene expression through modulation of the host miRNA signature.

More importantly, although altered miRNA expression profiles have been identified in serum and tissue from TB patients (Huang et al., 2015), the mechanistic basis underlying the development of TB by commensal bacteria through miRNAs has not been fully elucidated. Identifying the miRNAs regulated by gut microbiota of the production and function of IFN-γ will contribute to a better understanding of how to protect the host during M. tuberculosis infection while limiting the tissue damage caused by unrestrained inflammatory responses.

In the present study, we employed the “loss-of-function” model via the destruction/aberration of gut microbiota by antibiotic feedings and observed a similar broad-spectrum antibiotic regimen significantly decreases the gut microbiota and compromises immunity to pulmonary M. tuberculosis infection. Moreover, miR-21 was differentially expressed in the cecum and lung tissues while suppressing gut microbiome with broad-spectrum antibiotics during M. tuberculosis infection. Systemic antagonism of miR-21 provides effective protection against M. tuberculosis infection. On the basis of the observations noted above and the predication of IFN-γ as a potential target of miR-21, we demonstrated that miR-21 whose expression is remotely controlled by the microbiome directly targets IFN-γ and might in turn inhibit IFN-γ production leading to impaired anti-TB immunity. Thus, this work identifies a novel role for miR-21 in shaping the gut microbiota and the subsequent development of TB and may provide miR-21 as a novel target for the prevention and treatment of TB.

Materials and Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

| Anti-Mouse CD3 APC-Cy7 | Biolegend | Cat# 10033 |

| Anti-Mouse CD4 FITC | Biolegend | Cat# 100406 |

| Anti-Mouse CD8 Brilliant Violet 421 | Biolegend | Cat# 100738 |

| Anti-Mouse IFNγ PE | Biolegend | Cat# 505808 |

| Fixation/Permeabilization Solution | BD Biosciences | Cat# 51-2090KZ |

| BD Perm/Wash Buffer | BD Biosciences | Cat# 51-2091KZ |

| Mouse Th1/Th2/Th17 Cytokine Kit | BD Biosciences | Cat# 560485 |

| Lipofectamine 3000 | Invitrogen | Cat# L3000008 |

| Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System | Promega | Cat# E1910 |

| Quick-Amp Labeling Kit | Agilent | Cat# 5190-0447 |

| Gene Expression Hybridization Kit | Agilent | Cat# 5188-5242 |

| Trizol | Invitrogen | Cat# 15596026 |

| Middlebrook 7H11 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 283810 |

| Middlebrook OADC | BD Biosciences | Cat# 212240 |

| EZNA Tissue DNA Kit | Omega Bio-Tek | Cat# D3396 |

Study Subjects

Samples of active pulmonary TB patients (N = 31) before anti-TB treatment were recruited by the Guangdong Provincial Center for TB Control. The healthy controls (HCs) (N = 21) were collected by the same hospital clinics with annual routine health examination final reports indicating healthy statuses. Patient information is summarized in Table 1. Informed consent from all patients included in the study was obtained according to protocols approved by the Internal Review and the Ethics Boards of Zhongshan School of Medicine of Sun Yat-sen University (SYSU).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of active TB patients (TB) and healthy controls (HC).

| Healthy controls (HC) | TB patients (TB) | |

| Sample size | 21 | 31 |

| Female | 9 (42.9%) | 12 (38.7%) |

| Male | 12 (57.1%) | 19 (61.3%) |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 26.83 ± 9.8 | 27.47 ± 12.5 |

| Smear grade | ||

| None | 21 | 11 (35.5%) |

| 1+ | N/A | 9 (29.0%) |

| 2+ | N/A | 5 (16.1%) |

| 3+ | N/A | 6 (19.4%) |

| Chest X-ray | ||

| Nodules and fibrotic scars | N/A | 30 (96.8%) |

| Infiltrates or consolidations | N/A | 30 (96.8%) |

| Cavity | N/A | 9 (29.0%) |

| Atelectasis | N/A | 7 (22.6%) |

| Pleural effusion | N/A | 2 (6.5%) |

| Bronchiectasis | N/A | 7 (22.6%) |

Recruitment site: Guangdong Center for Tuberculosis Control.

Mice

All procedures were carried out under approval by the SYSU Institutional Animal care and Use Committee. SPF wild type of C57BL/6 (3-4 week) were obtained from the SYSU animal center and kept in SPF conditions at the Biosafety Level-3 laboratory of Sun Yat-sen University.

Antibiotics Treatment

A mix of ampicillin (1 mg/ml), neomycin (1 mg/ml), metronidazole (1mg/ml) and vancomycin (0.5mg/ml) were added in sterile drinking water of mice. Solutions and bottles were changed 2-3 times a week. Antibiotics activity was confirmed by cultivating the fecal pellets resuspended in BHI + 15% glycerol at 0.1g/ml on blood agar plates for 48 h at 37°C with in aerobic or anaerobic conditions. Mice were fed daily with broad-spectrum antibiotics during M. tuberculosis infection.

Tissue Pre-treatment for Bacteria Quantification

Lung and cecum tissues derived from mice of different groups were freshly isolated and broken into smaller pieces with a mortar and pestle, and homogenized in PBS buffer. The homogenate was treated with collagenase D (Sigma-Aldrich) (2 mg/mL final concentration) at 37°C for 15 min, followed by 10 min at 2000 × g at room temperature (RT). The pellet was washed with PBS (Sigma) (2000 × g for 10 min) and was further used for genomic DNA extraction.

DNA Extraction

Genomic DNA was isolated from tissue samples using the EZNA Tissue DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity, concentration of DNA was detected by using the NanoPhotometer spectrophotometer and Qubit2.0 Fluorometer.

16S rDNA Gene Amplification and Target Bacteria Analysis Using Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Targeted qPCR systems were applied using Sybr Green for the total bacteria and the bacteria of interest in tissue samples with primers amplifying the genes encoding 16S rRNA or specific bacterial groups. qPCR of major representative genera of gut and lung microbiota as described previously was performed to ensure broad bacterial coverage (Bassis et al., 2015). Primers for target bacteria were chosen from previously published literature (Table 2). The abundance of genus in both groups in this study was calculated as the quantitative abundance of bacterial ΔCT values and was normalized to 16S rRNA expression, the internal reference using threshold cycle (CT) method (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008).

TABLE 2.

The current list of qPCR primer couples.

| Target group | Primer sequence (5′–3′) | Ref. | |

| Total bacteria | F | CGGTGAATACGTTCCCGG | (Furet et al., 2009) |

| R | TACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT | ||

| Actinobacteria | F | TACGGCCGCAAGGCTA | (Trompette et al., 2014) |

| R | TCRTCCCCACCTTCCTCCG | ||

| Bacteroidetes | F | AACGCTAGCTACAGGCTTAACA | (Dick and Field, 2004) |

| R | ACGCTACTTGGCTGGTTCA | ||

| Gammaproteobacteria | F | CMATGCCGCGTGTGTGAA | (Mühling et al., 2008) |

| R | ACTCCCCAGGCGGTCDACTTA | ||

| Prevotella | F | CCTWCGATGGATAGGGGTT | (Layton et al., 2006) |

| R | CACGCTACTTGGCTGGTTCAG | ||

| Veillonella | F | GRAGAGCGATGGAAGCTT | (Tana et al., 2010) |

| R | CCGTGGCTTTCTATTCC | ||

| Streptococcus pneumonia | F | ACGCAATCTAGCAGATGAAGCA | (Chien et al., 2013) |

| R | TCGTGCGTTTTAATTCCAGCT | ||

| Haemophilus | F | AGCGGCTTGTAGTTCCTCTAACA | (Fukumoto et al., 2015) |

| R | CAACAGAGTATCCGCCAAAAGTT | ||

| Blautia | F | GTGAAGGAAGAAGTATCTCGG | (Kurakawa et al., 2015) |

| R | TTGGTAAGGTTCTTCGCGTT | ||

| Neisseria | F | CTGTTGGGCARCWTGAYTGC | (Yan et al., 2015) |

| R | GATCGGTTTTRTGAGATTGG | ||

| Fusobacterium | F | AAGCGCGTCTAGGTGGTTATGT | (Dalwai et al., 2007) |

| R | TGTAGTTCCGCTTACCTCTCCA | ||

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | F | GACCGCATGGTCTTGTTATT | (Haugland et al., 2010) |

| R | CGTAGGAGTTTGGACCGTGT | ||

| Escherichia coli | F | CATGCCGCGTGTATGAAGAA | (Huijsdens et al., 2002; Ramirez-Farias et al., 2009) |

| R | CGGGTAACGTCAATGAGCAAA | ||

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | F | GGAGGAAGAAGGTCTTCGG | (Ramirez-Farias et al., 2009) |

| R | AATTCCGCCTACCTCTGCACT |

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

Fecal samples (200–300 mg) from 10 healthy individuals were collected separately, homogenized and resuspended with 15% glycerol/PBS followed by centrifuge s at 2000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant slurry was pooled together and was aliquoted and stored at -80°C for future use. SPF mice were firstly treated with antibiotics for 1 week and colonized with fecal microbiota 2 days later. the fecal materials were thrawed in PBS, and 0.2 ml of the suspension containing a fecal microbiota obtained from healthy individuals, was transferred by oral gavage with a gap of 3 days interval into each mouse to reconstitute the gut composition.

M. tuberculosis Infection and Bacterial Count

Six to eight-week-old C57BL/6 mice were challenged intraperitoneally (i.p) with frozen stocks of wild type M. tuberculosis (H37Rv) strains, using an infection dose of 2.5 × 105 CFUs per mouse in 0.2 ml of suspension as described in our previous study (Wang et al., 2015). Lungs were carefully homogenized and the numbers of viable bacteria in the lungs were monitored by plating 10-fold serial dilution of lung homogenates from individual mice on to Middlebrook 7H11 (BD Biosciences) agar plate. The CFUs were counted after 21 days incubation at 37°C.

Histopathological Analyses of M. tuberculosis-Infected Mice

At the end of the M. tuberculosis infection period, animals were sacrificed. Lung tissues of mice were fixed in 10% formalin and processed for paraffin embedding. Paraffin Sections of 5 μm were counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Images were obtained using a microscope (BX51WI, Olympus) and a digital camera (DP30BW, Olympus). All sections were interpreted by the same person and scored semiquantitatively, blinded to the variables of the experiment. The histopathological parameters inflammatory lesions and granuloma formation were scored as absent (0-2), minimal (2-4), slight (4-6), moderate (6-8), marked, or strong (8-10) respectively. In this score, the frequency, as well as the severity of the lesions, were incorporated. Granuloma formation was scored by estimating the occupied area of the lung section. The lungs of three animals were examined and the mean score of each of the four histological parameters was calculated.

MicroRNA Sequencing, Data Analysis and Statistics

Total RNA of lung and cecum in M. tuberculosis-infected mice with or without the treatment of antibiotics were isolated with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and used for further miRNA microarray analysis. Briefly, we first labeled the RNAs with fluorescent probes by the Quick Amp Labeling Kit (Agilent), evaluated the purity and quality of the labeled RNA, and further hybridized using the Agilent Gene Expression Hybridization Kit (Agilent). The miRNA chips were washed with Gene Expression Wash Buffer (Agilent) and were then scanned with an Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner to determine expression profiles of miRNA in the lungs and cecum from treated or untreated mice. Those miRNAs with the differential fold changes of expression are larger as 2 as (or smaller than 0.5) and P < 0.05 using an independent t-test by R statistical software between the two groups were considered as significant and chosen for further bioinformatics analysis.

Design and Administration of miR21-Antagomir, Antagomir Control in Mice

miR21-agomir, antagomir and their control were designed by Ribobio corporation and purchased commercially. Before infection with M. tuberculosis (H37Rv), each mouse received i.p. injection of 15nmol of miRNA-21 agomir, antagomir and control for a total of four dosages with an interval of 3 days between two dosages.

Flu a Infection for miR-21 Quantification

Five to seven-week-old mice were anesthetized by intramuscular injection of 1.25 mg of ketamine plus 0.25 mg of xylazine in 100 μl of phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and then intranasally (i.n.) infected with 50 μl of PBS containing (or not, in a mock sample) 200 p.f.u. of the H1N1 IAV strain A/WSN/1933. Mice were fed daily with broad-spectrum antibiotics during influenza A infection. Animals that had lost >20% of their original body weight were euthanized. Total RNA was extracted from lungs of influenza A-infected or mock-infected mice and processed for qPCR quantification of miR-21.

Quantitation of miR-21 Expression

Total RNA was prepared from tissues or PBMCs using Trizol reagent. The concentration of total RNA was determined by a Nanodrop spectrometer. The cDNA was prepared by reverse transcription using a miR-21 specific primer or a U6 control primer, and real-time qPCR was performed as previously described (Wang et al., 2015). For SYBR-Green amplification, a melting step was added. Quantitative-PCR data were normalized to the expression levels of U6.

Luciferase Reporter Assay

The targets of miR-21-3p were identified by bioinformatic software Targetscan online. For dual-luciferase reporter assay, the IFN-G 3′ UTR segments, containing the binding elements of miR-21-3p or its mutant versions were synthesized commercially. Plasmid DNA with desired firefly luciferase reporter and pRL-TK renilla plasmids along with miRNA mimic or inhibitor were cotransfected into HEK293T cells using lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States). Relative activity of firefly luciferase unit (RLU) at 48 h post-transfection using a dual-luciferase reporter assay kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Promega, Madison, WI, United States) as instructions. A Renilla luciferase-expressing plasmid pRL-TK (Promega, Madison, WI, United States) was included in the transfection to normalize the efficiency of each transfection.

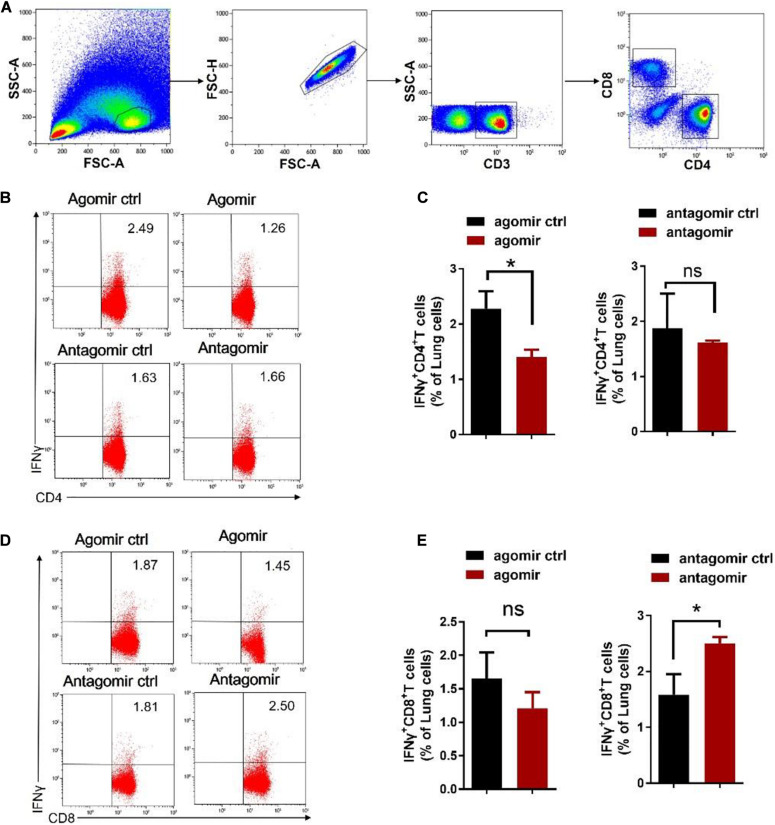

Intracellular Flow Cytometric Detection of IFN-γ Production in CD4+ and CD8 + T lymphocytes in Lungs

Experiments were conducted as described in our previous publication (Wang et al., 2015). Briefly, lungs were isolated and cut into small pieces and digested with collagenase D at the time of killing (Sigma). Then lung tissues were washed with PBS, carefully homogenized and filtered over a 70-μm filter to obtain single-cell suspensions. Lung lymphocytes were resuspended in RPMI 1640-based media containing 10% fetal calf serum and seeded (106cells per ml) into 24-well plates (Costar). Cells were firstly incubated in the presence of Mtb antigens (rESAT-6) for 16 h followed by another 6 h 3 μg/ml anti-CD28 MAb stimulation (Chackerian et al., 2001; Cardoso et al., 2002). After the incubation period, the cells were harvested, resuspended in PBS-fluorescence-activated cell-sorting (FACS) buffer and cell suspension was transferred into polystyrene round bottom tubes (BD) for surface staining. After staining for cell-surface markers for 20 min, cells were then permeabilized for 30 min (Cytofix/Cytoperm; BD) and stained 45 min for intracellular molecules such as IFN-γ before fixation with 2% formalin/PBS for 24 h. Cells were then analyzed using polychromatic flow cytometry. To ensure the specific immune staining of ICS, isotype IgG served as negative controls for staining surface markers or intracellular cytokines. Data were obtained from Beckman CytoFLEX S and analyzed by Kaluza 1.3 software. The gating strategy was as followed: the debris was first excluded by a morphology gate based on FSC-A and SSC-A. Then, non-singlets were eliminated from the analysis by a single cell gate based on FSC-H and FSC-A. Positive cells were gated with CD3 antigen and further divided based on their expression of CD4 and CD8 antigens.

Cytometric Bead Array (CBA)

Previously described procedures were employed (Wang et al., 2015). Cells derived from mice with indicated treatments were seeded at a density of 1 × 106 cells per well and stimulated with Mtb antigens (rESAT-6) at 37°C. Culture supernatants of cells were analyzed for the production of following cytokines: IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-17A, and IL-10 using the cytometric bead assay (CBA) mouse Th1/Th2/Th1 cytokine kit (BD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were acquired on the Beckman Coulter Gallios (Beckman). The concentrations of IFN-γ production were revealed by the fluorescence intensity and were calculated relative to the standard dilution curve.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical tests were performed using Prism software. Unless otherwise indicated, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test was often used for two groups comparisons to avoid the assumption of a normal distribution. For samples more than 20, statistical analyses were performed with the unpaired two-tailed Student t-test as indicated in the figures. The P values of significant differences are reported. Plotted data represent means ± SD unless otherwise stated. All experiments were replicated in the laboratory at least two times. In figure legend, N represents the number of samples. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001. NS, no statistical significance.

Results

Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota Provoked Susceptibility to TB Infection

Recently, human microbiota habitat in the body such as gut and respiratory tract, have been characterized by high-throughput sequencing technologies. Recent studies demonstrate that the lung is not sterile contrary to previous belief (Mathieu et al., 2018). Moreover, accumulating studies show that disturbance in gut microbiota is associated with the onset and progression of many diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmunity, obesity and cancer (Sanapareddy et al., 2012; Vetizou et al., 2015; Gray et al., 2017) by calibrating the host immunity (Schirmer et al., 2016; Thiemann et al., 2017). Besides, in addition to its local effects, gut microbiota modulates host immune response at extra-intestinal sites such as the brain, bone marrow and lung (Round and Mazmanian, 2009; Abt et al., 2012; Hooper et al., 2012; Arpaia et al., 2013; Atarashi et al., 2013; Honda and Littman, 2016; Schirmer et al., 2016). A key parameter controlling susceptibility to TB is the balance between the virulence of the M. tuberculosis strain and the immune status of the infected host. We therefore hypothesized that microbiome dysbiosis would have a profound impact on the microbiota that alters the nutritional landscape of the gut or the lung and increase the host susceptibility to TB due to aberrant immune response (Modi et al., 2014; Zanvit et al., 2015).

Antimicrobials remain the major and most potent factor causing dysbiosis (Moos et al., 2016), which refers to the microbial imbalance or maladaptation. As an initial step to investigate the role of microbiota dysbiosis in TB infection, we initially employed the “the-loss-of-function” model by antibiotics feedings consisting in the administration of a cocktail of broad-spectrum antibiotics composed of ampicillin, neomycin sulfate, metronidazole, and vancomycin for a week and determined the abundance and compositions of the microbiota. These antibiotics exhibited no impact on M.tuerbculsosis growth in a Middlebrook 7H11 agar formulation (Chang et al., 2002). Surprisingly, the significant loss of abundance of microbiota was only observed in the gut but not in the lung of the antibiotics-fed mice when compared with that of water-fed mice (Supplementary Figure 1). Numerous studies have agreed that gut and lung microbiota were dominated by Firmicutes, Bacteriodetes, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria phyla. Moreover, it was reported that genus Streptococcus, Haemophilus, Veilonella, and Prevotella (Clemente et al., 2012; Lozupone et al., 2012; Mathieu et al., 2018) were the dominated genera in the lung while genus Neisseria, Fusobacterium, Escherichia and Bacteroides accounted for 50–100% of the gut microbiota (Maslowski and MacKay, 2011). Thus, to further assess the effect of antibiotics on gut and lung microbiota communities, we characterized the levels of the representative phyla and genera dominated in gut and lung bacterial communities by qPCR between the antibiotics-treated and untreated group to ensure coverage of bacteria composition. The levels of lung microbiota communities have been slightly altered while gut microbiota demonstrated a marked decrease in the majority of the bacteria at both phyla and genus levels (Supplementary Figure 2). There were no significant differences in the composition of lung microbiota with or without antibiotics treatment (Supplementary Figure 2A), which was consistent with one study reporting that the effect on the lung microbiome is relatively minor, insignificant, and temporary in response to M. tuberculosis infection (Namasivayam et al., 2017). Moreover, the relative abundance of the most abundant phyla Bacteriodetes, which accounts for over 40% of the total gut microbiota, was significantly decreased in antibiotics-fed mice. Likewise, a similar trend was observed for the other phyla or genus. Whereas Actinobacteria is the only phyla, with no significant alternations of proportions by qPCR in the overall population of gut microbiota (Supplementary Figure 2B). Thus, our qPCR analysis of microbiota communities in gut and lung confirmed that antibiotics treatment only altered gut microbiota but had little effect on lung microbiome. Hence, to study anti-TB response to microbiota dysbiosis, we would focus on the commensal bacterial in the gut instead of the lung microbiome.

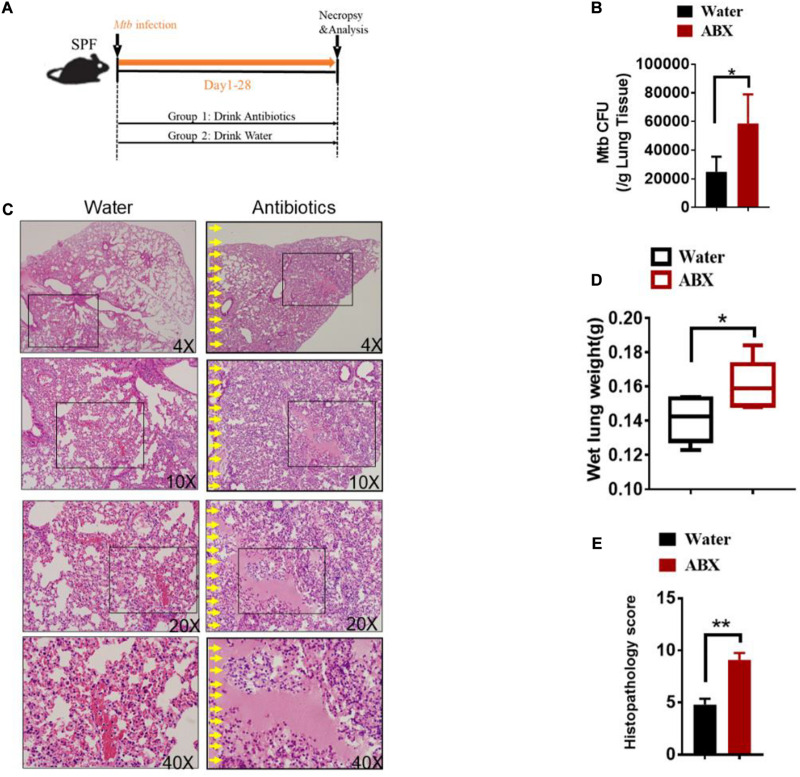

To evaluate the role of antibiotics on the development of TB infection, we further investigated whether antibiotics would directly affect lung pathology by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of lung sections without M.tuberculosis infection. Indeed, no obvious differences were observed in the lungs derived from antibiotics-treated and untreated mice (Supplementary Figure 3). We then determined whether gut microbial dysbiosis by daily broad-spectrum antibiotics feedings would compromise the ability of gut microbiota to support or sustain immune response or immunity against M. tuberculosis infection (Figure 1A). When compared with water controls, antibiotics feedings increased M. tuberculosis burdens in the lungs (Figure 1B), which was further corroborated with the histopathological analysis of the lungs (Supplementary Figure 4). More importantly, antibiotics treatment led to more severe lung pathology characterized by more cystic changes, hemorrhage, necrosis observed in the lungs (Figures 1C–E).

FIGURE 1.

Alteration in the gut microbiota provokes susceptibility to Tuberculosis. (A) Experimental design to test the importance of gut microbiota in control of M. tuberculosis infection and TB pathology. M. tuberculosis-infected mice were treated with sterilized water only (N = 6) or with broad-spectrum antibiotics (N = 6) [ampicillin (1 mg/ml), neomycin (1 mg/ml), metronidazole (1 mg/ml) and vancomycin (0.5 mg/ml)] in their drinking water for 4 weeks until mice were sacrificed for immunological, pathological, and bacillus burden analyses. (B) M. tuberculosis CFU quantitative analyses in the lungs (per gram) and cecum (per gram) in M. tuberculosis-infected mice with or without drinking antibiotics. (C) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of representative lungs of M. tuberculosis-infected mice with or without drinking broad-spectrum antibiotics. Yellow arrows mark extensive damages of pulmonary structures and unresolved hemorrhage, and extensive infiltration of inflammatory cells in the pulmonary compartments observed in the lung sections derived from M. tuberculosis-infected mice with drinking antibiotics. (D) The values of wet lung weight (g) for six representative lungs derived from M. tuberculosis-challenged mice with drinking antibiotics or water. (E) Quantitative representation of the lung histopathology in mice with antibiotics treatment or water treatment after infection with M. tuberculosis analyzed after hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining using histopathology score scale shown in Supplementary Figure 4. The histopathology score was averaged for six mice per each experimental group per time point. Data shown as mean ± SEM are representative of two independent experiments (N = 6 animals/group), *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test.

Thus, these data collectively suggested that the host gut microbiota but not lung microbiota contributes to resistance to TB and is critical in controlling M. tuberculosis infection and pathology.

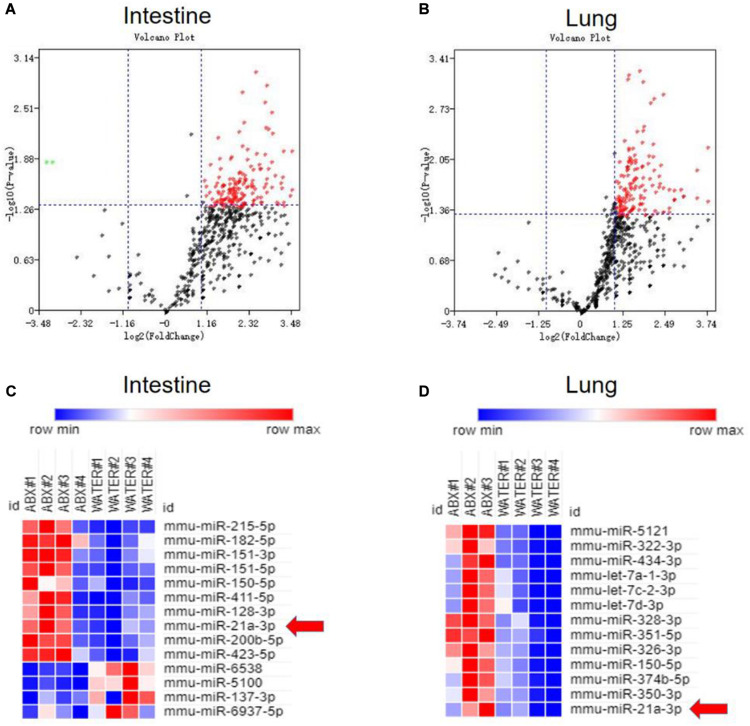

Gut Dysbiosis Significantly Up-Regulated the Expression of miR-21

Our and others’ previous studies on lncRNA (Wang et al., 2015) and miRNA (Ma et al., 2011) suggested that non-coding RNAs can modulate both innate and adaptive immunity in response to M. tuberculosis infection. Moreover, an increasing number of pieces of evidence indicated that miRNAs showed different expression patterns when the gut microbiota was altered and that differentiated miRNAs might contribute to shaping the interaction between the host and gut microbiota. Therefore, we would ask whether gut bacteria were associated with active TB infection by mediating the expression of some miRNAs. To clarify the postulation, we analyzed the miRNA expression profile in lungs and cecum of antibiotics treated and untreated mice in response to M. tuberculosis infection. We found differentially expressed miRNAs both in the lungs and cecum in the intestinal dysbiosis group. Of the 1767 miRNAs assayed, 150 were found to be significantly up-regulated, in the lungs of antibiotics-treated mice compared with control mice. Moreover, 190 out of 1019 miRNAs were found to be significantly up-regulated while 2 were down-regulated in the cecum of antibiotics-treated mice. Volcano plot analysis showed that miRNA differentially expressed in the lungs and cecum between microbiota dysbiosis mice and healthy mice with the p-values < 0.05 and fold of change >2 (Figures 2A,B). Notably, miR-21-3p was identified as one of the most significantly differently expressed miRNAs in both lungs and cecum in the microbiota dysbiosis mice (Figures 2C,D).

FIGURE 2.

Commensal bacteria regulate miRNA expression in cecum and lungs. Total RNA, including low molecular weight RNA, was prepared from the cecum and lungs derived from mice with or without antibiotics treatment. The expression of miRNA was analyzed by t-test. Volcano Plots compare the expression of miRNAs between cecum in mice with or without antibiotics treatment (A) or between lungs in mice with or without antibiotics treatment (B). The most significantly differentially expressed miRNAs with a greater than 2-fold difference in expression in cecum and lungs are shown in panels (C,D).

The remarkable up-regulation of the miR-21-3p observed in the lung and the cecum during TB infection/disease raises a possibility to examine whether this induction is somehow linked to alternations of gut microbiota by antibiotics feeding or due to antibiotics themselves. To address this question, we then assessed miR-21-3p expression by qPCR using an in vitro HEK-293T cell system. Not surprisingly, no significant difference was observed in miR-21-3p expression in HEK 293T cells with or without antibiotics treatment (Supplementary Figure 5). Thus, antibiotics themselves would not influence the expression pattern of miR-21-3p.

Our results collectively suggested that gut microbiota indeed acted as a regulator of miR-21-5p and up-regulated miR-21-3p in lungs and cecum is one of the key immunological markers in TB infection/disease associated with gut dysbiosis, and such up-regulation of miR-21-3p might indeed somehow be involved in regulating TB pathogenesis.

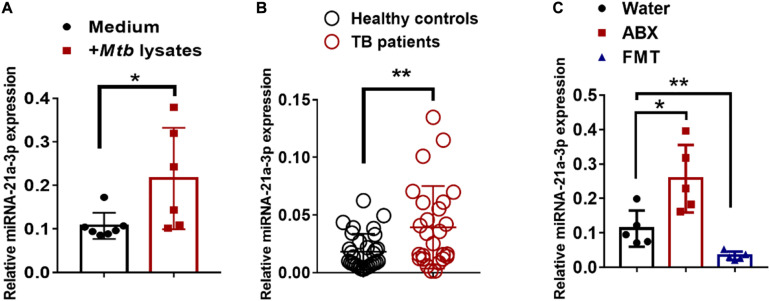

MiR-21-3p Expression Was Induced During Active TB Infection and Dictated by Commensal Bacteria

We then questioned whether gut dysbiosis-induced miR-21-3p was also associated with TB infection/disease in humans, we first investigated the expression of miR-21-3p in the context of M. tuberculosis infection in humans by qPCR. Indeed, high consistency of qPCR validation of miR-21-3p in cohorts of TB patients and healthy controls further supported that up-regulation of miR-21-3p might somehow be linked to active TB disease (Figure 3A). Such induction of miR-21-3p expression was at least partially specific for M. tuberculosis (Figure 3B) as no difference of miR-21-3p expression was observed in response to flu A infection (Supplementary Figure 6).

FIGURE 3.

MiR-21-3p expression deregulated by bacterial components is induced by M. tuberculosis infection in humans and mice. (A) MiR-21-3p expression in PBMCs from healthy controls (N = 21) and active TB patients (N = 31) was analyzed by qPCR. (B) Splenocytes from mice were stimulated with Medium (N = 7) or M. tuberculosis antigen (N = 6) for 72 h. MiR-21-3p expression was analyzed by qPCR. Normalized values of miR-21-3p with or without stimulation are shown as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (C) MiR-21-3p expression of representative lungs derived from the M. tuberculosis-infected mice with treatment of water (N = 5), antibiotics (N = 5) or FMTs of gut microbiota from healthy individuals (N = 5), respectively. Data shown as mean ± SEM are representative of two independent experiments. For human study, N > 20/per group, **p < 0.01, Student t-test. For animal experiments, N = 5-7 mice/per group *p < 0.05, non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test.

Recent evidence has reported changes in the gut microbial composition on M. tuberculosis exposure (Hu et al., 2019). Since it had been suggested that gnotobiotic mice might have specific expression patterns of miRNA profile, it was likely that miR-21-3p expression might constitute a signature that reflects the statuses in the gut bacteria ecosystem. We postulated that the “the-gain-of-function” model via oral transfer in mice would help to define the associations between gut dysbiosis and extra-intestinal miR-21-3p expression. We reconstituted the gut communities by oral gavage of human microbiota to mice. Interestingly, we observed a significant decline in the number of gut microbes in antibiotics-treated mice whereas the abundance of gut microbes was restored about 80% when compared with that of normal mice after fecal transplantation (Supplementary Figure 2B). It suggested that lowering microbial diversity by antibiotics treatment could not be fully restored to its original frequency by fecal transplantation for a short time. We also observed a significant increase in the number of Bacteroidetes and Veillonella phyla, but a slight decline in the level of Actinobacteria phyla (Supplementary Figure 2B). These results further support the partial reconstitution of gut microbial composition through fecal materials transfer. More importantly, alternations of the proportions of gut communities were seen, indicating the different diversity of gut microbes between humans and mice.

We further examined whether the reconstitution of gut microbiota from healthy individuals to mice would result in changes in miR-21-3p expression. Groups of mice were fed three times via oral gavage with water or fecal materials from healthy controls, the expression of miR-21-3p in the lungs was evaluated for changes by qPCR. Indeed, FMT was correlated with a decrease in the expression of miR-21-3p, which can be interpreted as the effect of gut microbiota on remotely regulating miR expression profiles (Figure 3C). Thus, our result further suggested that the gut microbiota plays a crucial role in regulating the expression of miR-21-3p in the lungs.

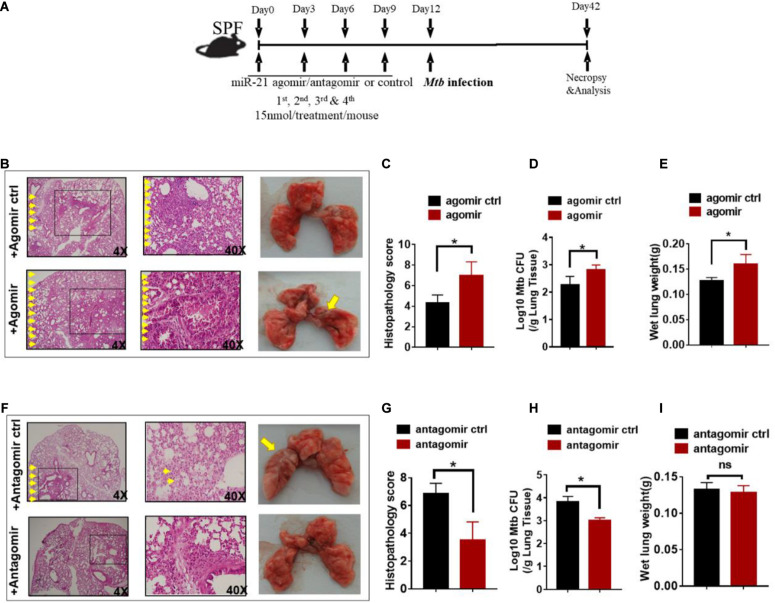

MiR-21 Played Critical Roles During M. tuberculosis Infection

Since gut microbiota was critical for developing resistance to TB and increased miR-21-3p expression patterns correlated with active TB infection in humans, we hypothesized that miR-21-3p, regulated by commensal gut bacteria might promote or depress the ability of gut microbiota to regulate pulmonary response and immunity during M. tuberculosis infection. We then investigated whether in vivo intervention of miR-21-3p expression has an impact on M. tuberculosis infection in mice. Before infection with M. tuberculosis, mice were firstly treated with either miR-21-3p agomir, antagomir or their controls by i.p. injection, then followed by a total of three dosages with an interval of 3 days between two dosages (Figure 4A). Exogenous expression of miR-21-3p by inoculating miR-21-3p agomir results in increased M. tuberculosis burdens in lungs and induced more severe TB pathology (Figures 4B–E). Meanwhile, we assessed whether miR-21-3p is required for restricting M. tuberculosis replication inhibition. Remarkably, mice that received miR-21-3p antagomir displayed significantly attenuated tissue pathology and significantly decreased M. tuberculosis burdens, while control-treated mice showed more severe lung pathology characterized by large-scale damage of lung structure (Figures 4F–I). Thus, these results illustrated that miR-21-3p plays a critical role in M. tuberculosis infection and TB pathology, and gut bacteria may mediate host resistance against TB through inhibition of miR-21-3p expression in lungs.

FIGURE 4.

Exogenous miR-21-3p contributes to more apparent M. tuberculosis infection while antagonism of miR-21-3p enhances immune protection against M. tuberculosis infection. (A) Experimental diagram showed that M. tuberculosis-infected mice were treated with agomir, antagomir or their controls in the presence of antibiotics and sacrificed at the indicated time point. Mice were i.p.- injected 4 doses of miRNA-21 agomir or agomir control with an interval of 3 days followed by M.tuberculosis infection. (B–E) Determination of the effect of exogenous miRNA-21 on M. tuberculosis infection. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and gross pathology of representative lungs of M. tuberculosis-infected miRNA-21 agomir treated (N = 3) or agomir control-treated (N = 3) mice; (C) Quantitative representation of the lung histopathology in mice with exogenous agomir or control treatment with M. tuberculosis infection analyzed after hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining using histopathology score scale is shown. (D) CFU of M. tuberculosis was analyzed in the lungs (per gram) treated with miRNA-21 agomir or miRNA-21 agomir control in infected mice. (E) The values of wet lung weight (g) for representative lungs derived from M. tuberculosis-challenged mice with agomir or agomir control. (F–I) Determination of the effect of antagonism of miRNA-21 on M. tuberculosis infection. Mice were treated in the same way as antagomir or antagomir control before M.tuberculosis infection. (F) H&E staining and gross pathology; (G) Lung pathology score; (H) CFU analysis; (I) wet lung weight (g) in representative lungs derived from mice with antagomir or antagomir control treatment. Data shown as mean ± SEM are representative of two independent experiments (N = 3 animals/group), *p < 0.05, ns: no statistical significance, non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test.

MiR-21 Impaired Protective Immunity by Affecting IFN-γ Production During M. tuberculosis Infection

We then examined how commensal bacteria-regulated miR-21 was involved in mediating protective immunity against M. tuberculosis infection. It is noteworthy that IFN-γ is required for immune resistance to TB (Flynn et al., 1993), and gut microbiota is important for the production of IFN-γ (Schirmer et al., 2016). We therefore postulated that IFN-γ might be a key mediator linking gut microbiota/miR-21 and pulmonary immune response against TB. On day 42 after infection with M. tuberculosis, intracellular cytokine staining of lungs derived from mice received exogenous miR-21 or antagonist of miR-21 were performed to investigate the physiological importance of miR-21 in the regulation of IFN-γ-production. In order to enhance the sensitivity of cytokine detection, cells were stimulated in vitro with the mycobacterial antigens and anti-CD28 MAb to increase cytokine production by T cells, and the cells were processed for flow cytometry as described in Materials and Methods. CD3 + CD4 + cells and CD3 + CD8 + cells were first gated (Figure 5A), and the results indicated that a significant decrease in the number of IFN-γ-producing CD4 + cells occurred in mice treated with exogenous miR-21 upon stimulation (Figures 5B,C), in contrast, more IFN-γ-producing CD8 + cells were observed in mice inoculating with miR-21 antagomir than did those from the control mice (Figures 5D–E). We further confirmed the presence of intracellular cytokine IFN-γ using a cytometric bead array (CBA). Cells derived from mice with agomir or antagomir and their respective controls were stimulated with Mtb antigen ESAT-6 and incubated for 72 h. The levels of the cytokines IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-4 and IL-17A were analyzed in the cell culture supernatants by CBA. The results indicated that the level of IFN-γ was significantly reduced in the mice received miR-21-3p agomir when compared to the control (835.56 ± 53.52 vs. 23.14 ± 61.3, pg/ml, P < 0.05) (Supplementary Figure 8A), while more IFN-γ production was observed in mice inoculating with miR-21 antagomir than did those from the control mice (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Figure 8B). Therefore, these data suggest that miR-21 negatively regulates anti-mycobacterial immune responses.

FIGURE 5.

Exogenous miR-21-3p inhibits CD4 + IFN-γ + subsets while antagonism of miR-21-3p eliciting CD8 + IFN-γ + in the lungs of M. tuberculosis-infected mice. (A) Gating strategy used for the analysis of IFN-γ expression on CD4 + and CD8 + T cells. Dot-plots show lung lymphocytes gating on the forward (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) detectors. Live CD3 + T-cells were gated from lymphocytes after single cells gating, followed by identification of CD4 + and CD8 + T-cells sub-populations. Arrows show the sequence of the gating used, starting from the lymphocytes gate. (B–E) Representative flow cytometric dot plots and pooled bar graphic data show the expression of IFN-γ of panels (B–C) CD4 + and (D–E) CD8 + in lung derived from M. tuberculosis-infected mice with agomir, antagomir and their corresponding controls. Lung lymphocytes were stimulated in vitro with Mtb antigen ESAT-6 (5 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 antibody. After the incubation period, cells were harvested and evaluated by flow cytometry. Cells were acquired in the gated lymphocyte population, and the quadrants were set up with an isotype-matched control. The numbers in the upper right quadrant of each dot plot are the percentages of CD4+ or CD8 + T cells produced IFN-γ. Data shown as mean ± SEM are representative of two independent experiments (N = 3 animals/group), *p < 0.05, ns, no statistical significance, non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test.

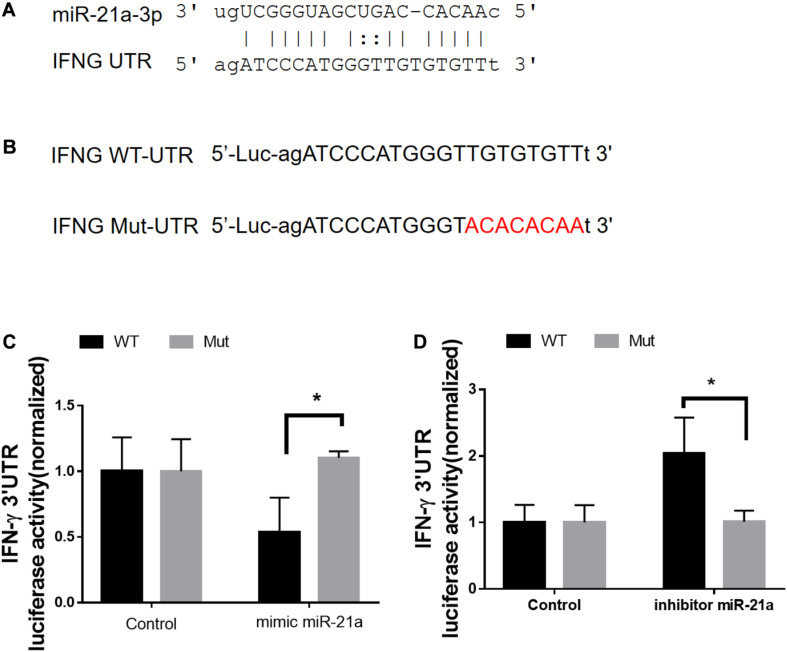

Direct Targeting of the 3′-UTR of IFN-γ mRNA by miR-21

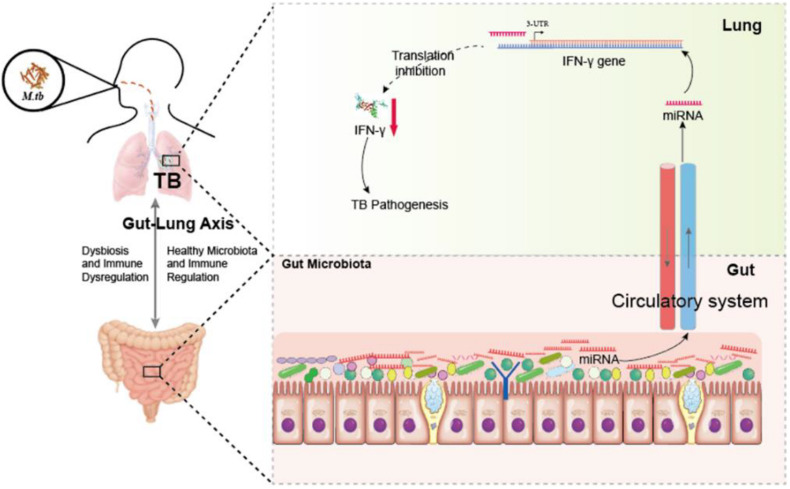

We next sought to investigate the molecular mechanisms by which antibiotics destruction of microbiota increased miR-21 expression and depressed IFN-γ responses leading to a loss of immune resistance to M. tuberculosis infection. Our above data suggested the potential inhibitory effect of miR-21-3p on IFN-γ production. We then hypothesized that miR-21 might directly target IFNG. We predicted the binding motif of miR-21a-3p on 3′UTR of IFNG by Targetscan database and revealed that 3′UTR of IFNG bears the miR-21 binding sites (Figure 6A). We then performed the luciferase reporter assay to verify the database predictions using plasmids containing a wild type as well as the mutated 3′UTR of IFNG-binding motif fused luciferase reporter (Figure 6B) and miR-21 mimic and inhibitor. Our results indicated that the luciferase activity of the IFN-γ 3′ UTR wild type reporter but not IFN-γ 3′ UTR reporter with mutated miR-21-binding sites was significantly inhibited when transfected the “mimics”of miR-21 (Figure 6C). In contrast, the endogenous miR-21 inhibitor significantly enhanced the luciferase activity of the IFN-γ 3′ UTR reporter, while no differences were found between cells transfected with the IFN-γ 3′ UTR reporter with mutated miR-21-binding sites with or without miR-21 inhibitor (Figure 6D). Thus, our data clearly illustrates that IFN-γ mRNA was targeted by miR-21a-3p, which is likely involved in the molecular mechanism underlying commensal bacteria-regulated miR-21 impaired anti-TB immunity (Figure 7).

FIGURE 6.

MiR-21a-3p directly targets IFN-γ mRNA 3′-UTR to inhibit its expression. (A) Predicted miR-21a-3p targeting sequence on the 3′-UTR of IFN-γ mRNA. (B) Wild type (IFN-γ-UTR) targeting sequence of miR-21a-3p on 3′-UTR of IFN-γ mRNA, and the mutated version (IFN-γ-mut), were cloned at the downstream of the luciferase open reading frame (Luc). (C) Luciferase activities of IFN-γ-UTR or IFN-γ-mut-UTR constructs were examined after the co-transfection of miR-NC or mimic miR-21a-3p, respectively. (D) Luciferase activities of IFN-γ-UTR or IFN-γ-mut-UTR constructs were examined after co-transfection of miR-NC or miR-21a-3p inhibitor, respectively. Data shown as mean ± SEM are representative of two independent experiments, *p < 0.05, non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test.

FIGURE 7.

Hypothetic working model of regulating anti-TB protective immune paradigm via manipulating commensal bacteria-governed miRNA expression. Aberration of gut microbiota provokes susceptibility to TB and increases miR-21-3p expression not only in the cecum but also in the lungs during M. tuberculosis infection, in turn targeting IFN-γ. Exogenous miR-21-3p directly targets IFN- mRNA, in turn contributes to TB pathogenesis.

Discussion

Tuberculosis is the leading cause of death worldwide, killing nearly 2 million people each year (Maartens and Wilkinson, 2007). Discoveries of new paradigms for anti-TB immunity can certainly help develop new therapeutics and vaccines for global TB control (Zumla et al., 2013; Nunes-Alves, 2014; Rubin, 2014). Aerosol absorption of M.tuberculsosis is the natural route of TB infection by lung tissues. However, several studies affirmed that i.p. infection also results in chronic TB infection in mouse lungs similar to that observed during low dose aerosol infection with several advantages. The i.p. infection model establishes a steady-state level of CFUs in organs that do not change significantly over time (Orme and Collins, 1994; Phyu et al., 1998; Dahl et al., 2003). Given that clinical latency in humans is characterized by low bacillary loads, the i.p. route of infection may in fact model TB latency. Moreover, i.p. infections are low-level cross contamination between animals and the high-dose challenge with Mycobacteria is known to push the systemic immune responses. Therefore, the high-dose i.p. infection TB model may more appropriate for studying the gut microbiota shaped systemic immunity.

The microbiota plays an important role in the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis and a complex, reciprocal relationship with the host immune system (Lee et al., 2014) and so far, accumulating evidence had been highlighted the role of the microbial dysbiosis in contributing to the development and progress of various diseases and focused on identifying the underlying factors and mechanisms (Marchesi et al., 2016; Schirmer et al., 2016). Antibiotics are often used in clinics to treat bacterial infections, but they are also a major factor in disturbing the gut microbial composition and provoke host susceptibility to enteric infection (Modi et al., 2014). In the current study, we chose antibiotics, which are effective against both Gram-positive and -negative bacteria but not M.tuberculosis viability, to significantly induce dysbiosis in the gut (Chang et al., 2002). Interestingly, disruption of gut microbiota with antibiotics revealed a significant reduction of abundance and diversity of gut microbiota but not lung microbiota, indicating that antibiotics only influence the colonized bacteria at local organs. Moreover, key findings that emerged from the current study also revealed the role of gut microbiota in controlling the pathogenesis of TB as higher M.tuberculosis burden in the lungs and more severe pathology were observed with the treatment of antibiotics during TB. All histopathological parameters increased in severity in the course of TB infection. Thus, the severity of TB disease was evaluated by histopathological score. The histopathological scores were generally positively correlated with CFU counts and TB severity. Large differences in the antibiotics-induced lung pathology and more severe TB were observed, demonstrating further that intestinal dysbiosis might be a necessary factor contributing to the development and progress of active TB infection. This hypothesis gains support from our study and other reports wherein broad-spectrum antibiotics-driven microbial dysbiosis provokes susceptibility to TB in the mouse model (Khan et al., 2016).

Our results suggest a link between miRNA expression and gut microbes as we presented that intestinal dysbiosis by broad-spectrum antibiotics would significantly modulate the expression of miR-21-3p in lung and cecum derived from M. tuberculosis-infected mice. Previous investigations have also suggested the miRNA expression and gut microbes as the colonized gut microbiota in ileum and colon in SPF mice and Germ-free mice were different and such miRNAs would contribute to the development of diseases associated with dysbiosis of intestinal microbiota (Dalmasso et al., 2011b). More importantly, Mycobacterium leprae upregulates miR-21 expression to escape the vitamin D-dependent induction of antimicrobial peptides (Sheedy et al., 2010). Therefore, it is likely that altered miR-21-3p expression may partially result from host-microbe interactions and therefore involved in immune resistance against M. tuberculosis infection.

Somehow surprisingly, we found the gut microbiota can also impact host miRNA expression in the lungs well beyond the gut. The impact of antibiotics driven changes in gut microbiota and altered miR-21-3p expression was further supported by FMT reconstitution. Interestingly, fecal materials transplantation of antibiotics-treated mice restores the gut microbiota and increase miR-21-3p expression in their lungs. Consistently, two recent studies have also identified differential miRNA expression in the aorta and hippocampus of germ-free versus conventional mice. Results from us and others indicated that the commensal gut bacteria-related miRNA is linked to the regulation of the gut-lung axis for immunity and opened a novel and interesting avenue for future research.

It is noteworthy that miRNAs act as key regulators of innate and adaptive immunity as well as in disease development. More importantly, miRNAs recently reported to be governed by commensal bacteria, affected NF-kB-pathway activity via targeting the IL-23p19 gene (Xue et al., 2014). Notably, IFN-γ is required for immune resistance to TB (Flynn et al., 1993) and our results revealed regulation events from modulation of miR-21 in considerable IFN-γ responses that broadly involve CD4+ T and CD8+ T effector subpopulation. Thus, it is not surprising to see changes in IFN-γ- production and miR-21 mediated anti-TB immunity in our functional models. At the molecular level, the elevated IFN-γ production correlates with the upregulated expression of miR-21-3p. This negative correlation between miR-21-3p and IFN-γ is subsequently found to be a consequence of their directly targeting, where miR-21a-3p directly targets IFN-γ 3′-UTR to inhibit its expression.

In summary, our studies show an association between gut microbiota and M. tuberculosis infection and demonstrate a significant role for inhibition of miR-21-3p on controlling M. tuberculosis infection via modulating the immune protection via increasing production of IFN-γ. The current study defines regulatory pathways implicating intestinal dysbacteriosis induced-susceptibility to TB: intestinal dysbiosis→lung miRNA→targeting IFN-γ→impaired anti-TB immunity. Our work also presents a novel way toward new therapeutic intervention on controlling M. tuberculosis infection.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the GSE125870.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the SYSU Institutional Animal care and Use committee.

Author Contributions

FY and GZe led the project, conceived, and planned the experiments. YY and YC carried out the experiments. GL, GZh, LC, ZZ, QM, and GZe contributed to interpretation of the results. FY took the lead in writing the manuscript. All authors contributed to drafting the work and gave final approval for the version to be published, agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved and provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation 2017M612811 (To FY), National Science and Technology Major Project 2018ZX10715004-002-012 (To FY), Guangdong Science and Technology Project Grant 2018A05056032 (To GZe), and NSFC grant 82072250 (To GZe).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.512581/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abt M. C., Osborne L. C., Monticelli L. A., Doering T. A., Alenghat T., Sonnenberg G. F., et al. (2012). Commensal bacteria calibrate the activation threshold of innate antiviral immunity. Immunity 37 158–170. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpaia N., Campbell C., Fan X., Dikiy S., Van Der Veeken J., Deroos P., et al. (2013). Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature 504 451–455. 10.1038/nature12726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atarashi K., Tanoue T., Oshima K., Suda W., Nagano Y., Nishikawa H., et al. (2013). Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of Clostridia strains from the human microbiota. Nature 500 232–236. 10.1038/nature12331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassis C. M., Erb-Downward J. R., Dickson R. P., Freeman C. M., Schmidt T. M., Young V. B., et al. (2015). Analysis of the upper respiratory tract microbiotas as the source of the lung and gastric microbiotas in healthy individuals. mBio 6, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt K., Salgame P. (2007). Host innate immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Immunol. 27 347–362. 10.1007/s10875-007-9084-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley C. P., Teng F., Felix K. M., Sano T., Naskar D., Block K. E., et al. (2017). Segmented filamentous bacteria provoke lung autoimmunity by Inducing Gut-Lung Axis Th17 Cells Expressing Dual TCRs. Cell Host Microbe 22 697.e–704.e. 10.1016/j.chom.2017.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso F. L., Antas P. R., Milagres A. S., Geluk A., Franken K. L., Oliveira E. B., et al. (2002). T-cell responses to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific antigen ESAT-6 in Brazilian tuberculosis patients. Infect. Immun. 70 6707–6714. 10.1128/iai.70.12.6707-6714.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chackerian A. A., Perera T. V., Behar S. M. (2001). Gamma interferon-producing CD4+ T lymphocytes in the lung correlate with resistance to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 69 2666–2674. 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2666-2674.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. L., Park T. S., Oh S. H., Kim H. H., Lee E. Y., Son H. C., et al. (2002). Reduction of contamination of mycobacterial growth indicator tubes with a modified antimicrobial combination. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40 3845–3847. 10.1128/JCM.40.10.3845-3847.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien Y. W., Vidal J. E., Grijalva C. G., Bozio C., Edwards K. M., Williams J. V., et al. (2013). Density interactions among streptococcus pneumoniae, haemophilus influenzae and staphylococcus aureus in the nasopharynx of young Peruvian children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 32 72–77. 10.1097/INF.0b013e318270d850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente J. C., Ursell L. K., Parfrey L. W., Knight R. (2012). The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell 148 1258–1270. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colditz G. A., Brewer T. F., Berkey C. S., Wilson M. E., Burdick E., Fineberg H. V., et al. (1994). Efficacy of BCG vaccine in the prevention of tuberculosis. Meta-analysis of the published literature. JAMA 271 698–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl J. L., Kraus C. N., Boshoff H. I. M., Doan B., Foley K., Avarbock D., et al. (2003). The role of RelMtb-mediated adaptation to stationary phase in long-term persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 10026–10031. 10.1073/pnas.1631248100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmasso G., Nguyen H. T. T., Yan Y., Laroui H., Charania M. A., Ayyadurai S. (2011a). Microbiota modulates host gene expression via MicroRNAs. Gastroenterology 140, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmasso G., Nguyen H. T. T., Yan Y., Laroui H., Charania M. A., Ayyadurai S., et al. (2011b). Microbiota modulate host gene expression via micrornas. PLoS ONE 6:e0019293. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalwai F., Spratt D. A., Pratten J. (2007). Use of quantitative PCR and culture methods to characterize ecological flux in bacterial biofilms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45 3072–3076. 10.1128/JCM.01131-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dheda K., Gumbo T., Gandhi N. R., Murray M., Theron G., Udwadia Z., et al. (2014). Global control of tuberculosis: from extensively drug-resistant to untreatable tuberculosis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2 321–338. 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70031-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick L. K., Field K. G. (2004). Rapid estimation of numbers of fecal Bacteroidetes by use of a quantitative PCR assay for 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70 5695–5697. 10.1128/AEM.70.9.5695-5697.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson R. P., Erb-Downward J. R., Martinez F. J., Huffnagle G. B. (2016). The microbiome and the respiratory tract. Annu. Rev Physiol. 78 481–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn J. L., Chan J., Triebold K. J., Dalton D. K., Stewart T. A., Bloom B. R. (1993). An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 178 2249–2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel L. B., Christoffersen N. R., Jacobsen A., Lindow M., Krogh A., Lund A. H. (2008). Programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4) is an important functional target of the microRNA miR-21 in breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 283 1026–1033. 10.1074/jbc.M707224200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto H., Sato Y., Hasegawa H., Saeki H., Katano H. (2015). Development of a new real-time PCR system for simultaneous detection of bacteria and fungi in pathological samples. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 8 15479–15488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furet J. P., Firmesse O., Gourmelon M., Bridonneau C., Tap J., Mondot S., et al. (2009). Comparative assessment of human and farm animal faecal microbiota using real-time quantitative PCR. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 68 351–362. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00671.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J., Oehrle K., Worthen G., Alenghat T., Whitsett J., Deshmukh H. (2017). Intestinal commensal bacteria mediate lung mucosal immunity and promote resistance of newborn mice to infection. Sci. Transl. Med. 9:eaaf9412. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf9412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugland R. A., Varma M., Sivaganesan M., Kelty C., Peed L., Shanks O. C. (2010). Evaluation of genetic markers from the 16S rRNA gene V2 region for use in quantitative detection of selected Bacteroidales species and human fecal waste by qPCR. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 33 348–357. 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda K., Littman D. R. (2016). The microbiota in adaptive immune homeostasis and disease. Nature 535 75–84. 10.1038/nature18848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper L. V., Littman D. R., Macpherson A. J. (2012). Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science 336 1268–1273. 10.1126/science.1223490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Feng Y., Wu J., Liu F., Zhang Z., Hao Y., et al. (2019). The Gut Microbiome Signatures Discriminate Healthy From Pulmonary Tuberculosis Patients. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 9:90. 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Jiao J., Xu W., Zhao H., Zhang C., Shi Y., et al. (2015). MiR-155 is upregulated in patients with active tuberculosis and inhibits apoptosis of monocytes by targeting FOXO3. Mol. Med. Rep. 12 7102–7108. 10.3892/mmr.2015.4250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huijsdens X. W., Linskens R. K., Mak M., Meuwissen S. G. M., Vandenbroucke-Grauls C. M. J. E., Savelkoul P. H. M. (2002). Quantification of bacteria adherent to gastrointestinal mucosa by real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40 4423–4427. 10.1128/JCM.40.12.4423-4427.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida N., Dzutsev A., Stewart C. A., Smith L., Bouladoux N., Weingarten R. A., et al. (2013). Commensal bacteria control cancer response to therapy by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Science 342 967–970. 10.1126/science.1240527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov I. I., Honda K. (2012). Intestinal commensal microbes as immune modulators. Cell Host Microbe 12 496–508. 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann S. H. (2006). Envisioning future strategies for vaccination against tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6 699–704. 10.1038/nri1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann S. H., Hussey G., Lambert P. H. (2010). New vaccines for tuberculosis. Lancet 375 2110–2119. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60393-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan N., Vidyarthi A., Nadeem S., Negi S., Nair G., Agrewala J. N. (2016). Alteration in the gut microbiota provokes susceptibility to tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 7:529. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. K., Kim T. S., Basu J., Jo E. K. (2017). MicroRNA in innate immunity and autophagy during mycobacterial infection. Cell Microbiol. 19 10.1111/cmi.12687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosiewicz M. M., Zirnheld A. L., Alard P. (2011). Gut microbiota, immunity, and disease: a complex relationship. Front. Microbiol. 2:180. 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurakawa T., Ogata K., Matsuda K., Tsuji H., Kubota H., Takada T., et al. (2015). Diversity of intestinal Clostridium coccoides group in the Japanese population, as demonstrated by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. PLoS One 10:e0126226. 10.1371/journal.pone.0126226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layton A., McKay L., Williams D., Garrett V., Gentry R., Sayler G. (2006). Development of Bacteroides 16S rRNA gene taqman-based real-time PCR assays for estimation of total, human, and bovine fecal pollution in water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 4214–4224. 10.1128/AEM.01036-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. N., Ye C., Villani A. C., Raj T., Li W., Eisenhaure T. M., et al. (2014). Common genetic variants modulate pathogen-sensing responses in human dendritic cells. Science 343:1246980. 10.1126/science.1246980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Da Cunha A. P., Rezende R. M., Cialic R., Wei Z., Bry L., et al. (2016). The host shapes the gut microbiota via fecal MicroRNA. Cell Host Microbe 19 32–43. 10.1016/j.chom.2015.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozupone C. A., Stombaugh J. I., Gordon J. I., Jansson J. K., Knight R. (2012). Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 489 220–230. 10.1038/nature11550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T. X., Hartner J., Lim E. J., Fabry V., Mingler M. K., Cole E. T., et al. (2011). MicroRNA-21 limits in vivo immune response-mediated activation of the IL-12/IFN-γ pathway, Th1 polarization, and the severity of delayed-type hypersensitivity. J. Immunol. 187 3362–3373. 10.4049/jimmunol.1101235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma F., Xu S., Liu X., Zhang Q., Xu X., Liu M., et al. (2011). The microRNA miR-29 controls innate and adaptive immune responses to intracellular bacterial infection by targeting interferon-gamma. Nat. Immunol. 12 861–869. 10.1038/ni.2073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maartens G., Wilkinson R. J. (2007). Tuberculosis. Lancet 370 2030–2043. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61262-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchesi J. R., Adams D. H., Fava F., Hermes G. D. A., Hirschfield G. M., Hold G., et al. (2016). The gut microbiota and host health: a new clinical frontier. Gut 65 330–339. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsland B. J., Trompette A., Gollwitzer E. S. (2015). The gut-lung axis in respiratory disease. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 12 S150–S156. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201503-133AW [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowski K. M., MacKay C. R. (2011). Diet, gut microbiota and immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 12 5–9. 10.1038/ni0111-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu E., Escribano-Vazquez U., Descamps D., Cherbuy C., Langella P., Riffault S., et al. (2018). Paradigms of lung microbiota functions in health and disease, particularly, in Asthma. Front. Physiol. 9:1168. 10.3389/fphys.2018.01168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi S. R., Collins J. J., Relman D. A. (2014). Antibiotics and the gut microbiota. J. Clin. Invest. 124 4212–4218. 10.1172/JCI72333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos W. H., Faller D. V., Harpp D. N., Kanara I., Pernokas J., Powers W. R., et al. (2016). Microbiota and neurological disorders: a gut feeling. Biores Open Access 5 137–145. 10.1089/biores.2016.0010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mühling M., Woolven-Allen J., Murrell J. C., Joint I. (2008). Improved group-specific PCR primers for denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of the genetic diversity of complex microbial communities. ISME J. 2 379–392. 10.1038/ismej.2007.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namasivayam S., Maiga M., Yuan W., Thovarai V., Costa D. L., Mittereder L. R., et al. (2017). Longitudinal profiling reveals a persistent intestinal dysbiosis triggered by conventional anti-tuberculosis therapy. Microbiome 5:71. 10.1186/s40168-017-0286-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes-Alves C. (2014). Antimicrobials: the benefits of cycling. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 724–725. 10.1038/nrmicro3370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orme I. M., Collins F. M. (1994). Mouse model of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 113–134.8126987 [Google Scholar]

- Pan X., Wang Z. X., Wang R. (2010). MicroRNA-21: a novel therapeutic target in human cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 10 1224–1232. 10.4161/cbt.10.12.14252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paun A., Yau C., Danska J. S. (2016). Immune recognition and response to the intestinal microbiome in type 1 diabetes. J. Autoimmun. 71 10–18. 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phyu S., Mustafa T., Hofstad T., Nilsen R., Fosse R., Bjune G. (1998). A mouse model for latent tuberculosis. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 30 59–68. 10.1080/003655498750002321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Farias C., Slezak K., Fuller Z., Duncan A., Holtrop G., Louis P. (2009). Effect of inulin on the human gut microbiota: Stimulation of Bifidobacterium adolescentis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. Br. J. Nutr. 101 541–550. 10.1017/S0007114508019880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Round J. L., Mazmanian S. K. (2009). The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9 313–323. 10.1038/nri2515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin E. J. (2014). Troubles with tuberculosis prevention. N Engl. J. Med. 370, 375–376. 10.1056/NEJMe1312301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson T. R., Debelius J. W., Thron T., Janssen S., Shastri G. G., Ilhan Z. E., et al. (2016). Gut microbiota regulate motor deficits and neuroinflammation in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Cell 167, 1469.e12-1480.e12. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanapareddy N., Legge R. M., Jovov B., McCoy A., Burcal L., Araujo-Perez F., et al. (2012). Increased rectal microbial richness is associated with the presence of colorectal adenomas in humans. ISME J. 6 1858–1868. 10.1038/ismej.2012.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirmer M., Smeekens S. P., Vlamakis H., Jaeger M., Oosting M., Franzosa E. A., et al. (2016). Cell 167 1125.e8–1136.e8. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen T. D., Livak K. J. (2008). Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 3 1101–1108. 10.1038/nprot.2008.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheedy F. J., Palsson-Mcdermott E., Hennessy E. J., Martin C., O’Leary J. J., Ruan Q., et al. (2010). Negative regulation of TLR4 via targeting of the proinflammatory tumor suppressor PDCD4 by the microRNA miR-21. Nat. Immunol. 11 141–147. 10.1038/ni.1828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N., Shirdel E. A., Waldron L., Zhang R. H., Jurisica I., Comelli E. M. (2012). The murine caecal microRNA signature depends on the presence of the endogenous microbiota. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 8 171–186. 10.7150/ijbs.8.171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tana C., Umesaki Y., Imaoka A., Handa T., Kanazawa M., Fukudo S. (2010). Altered profiles of intestinal microbiota and organic acids may be the origin of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 22 512–519. 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01427.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W. H., Kitai T., Hazen S. L. (2017). Gut microbiota in cardiovascular health and disease. Circ. Res. 120 1183–1196. 10.1161/circresaha.117.309715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W. H. W., Wang Z., Levison B. S., Koeth R. A., Britt E. B., Fu X., et al. (2013). Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. New Engl. J. Med. 368 1575–1584. 10.1056/NEJMoa1109400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiemann S., Smit N., Roy U., Lesker T. R., Galvez E. J. C., Helmecke J., et al. (2017). Enhancement of IFNgamma Production by Distinct Commensals Ameliorates Salmonella-Induced Disease. Cell Host Microbe 21, 682.e5-694.e5. 10.1016/j.chom.2017.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trompette A., Gollwitzer E. S., Yadava K., Sichelstiel A. K., Sprenger N., Ngom-Bru C., et al. (2014). Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat. Med. 20 159–166. 10.1038/nm.3444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetizou M., Pitt J. M., Daillere R., Lepage P., Waldschmitt N., Flament C., et al. (2015). Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science 350 1079–1084. 10.1126/science.aad1329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Zhong H., Xie X., Chen C. Y., Huang D., Shen L., et al. (2015). Long noncoding RNA derived from CD244 signaling epigenetically controls CD8+ T-cell immune responses in tuberculosis infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 E3883–E3892. 10.1073/pnas.1501662112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winglee K., Eloe-Fadrosh E., Gupta S., Guo H., Fraser C., Bishai W. (2014). Aerosol Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection causes rapid loss of diversity in gut microbiota. PLoS One 9:e97048. 10.1371/journal.pone.0097048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue X., Cao A. T., Cao X., Yao S., Carlsen E. D., Soong L., et al. (2014). Downregulation of microRNA-107 in intestinal CD11c(+) myeloid cells in response to microbiota and proinflammatory cytokines increases IL-23p19 expression. Eur. J. Immunol. 44 673–682. 10.1002/eji.201343717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X., Yang M., Liu J., Gao R., Hu J., Li J., et al. (2015). Discovery and validation of potential bacterial biomarkers for lung cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 5 3111–3122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanvit P., Konkel J. E., Jiao X., Kasagi S., Zhang D., Wu R., et al. (2015). Antibiotics in neonatal life increase murine susceptibility to experimental psoriasis. Nat. Commun. 6:8424. 10.1038/ncomms9424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumla A., Raviglione M., Hafner R., von Reyn C.F. (2013). Tuberculosis. N Engl. J. Med. 368, 745–755. 10.1056/NEJMra1200894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the GSE125870.