Abstract

Crystallization of concomitant polymorphs is a very intriguing process that is difficult to be studied experimentally. A comprehensive study of two polymorphic modifications of acetyl 2-(N-(2-fluorophenyl)imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide using quantum chemical methods has revealed molecular and crystal structure dependence on crystallization conditions. Fast crystallization associated with a kinetically controlled process results in the formation of a columnar structure with a nonequilibrium molecular conformation and more isotropic topology of interaction energies between molecules. Slow crystallization may be considered as a thermodynamically controlled process and leads to the formation of a layered crystal structure with the conformation of the molecule corresponding to local minima and anisotropic topology of interaction energies. Fast crystallization results in the formation of a lot of weak intermolecular interactions, while slow crystallization leads to the formation of small amounts of stronger interactions.

Introduction

2-Iminocoumarines are known to be a very important class of organic compounds due to their properties. Similar to the well-studied coumarines, which have been found in various species of plants,1−3 2-iminocoumarine derivatives are used as dyes4,5 and fluorescent sensors for detection of metal ions in a very low concentration.6−8 Furthermore, these fluorophores have low cytotoxicity and can selectively stain organelles in living cells.4 A lot of 2-iminocoumarines possess high antibacterial,9 antifungal,10 anti-HIV,11 antimicrobial,12,13 anti-Alzheimer14,15 activity. Recently, it has been found that arylsubsituted iminocoumarines have revealed high antitumor and anticancer activity.16−18

A comprehensive study of biologically active compounds in crystal phases is needed regarding their prospective application in medicine. The reasons for such a study are (a) the necessity of patent protection; (b) the search for the most effective polymorphic form. The coumarine polymorphism has been thoroughly studied and five crystal forms have been found.19 In contrast to coumarine, the 2-iminocoumarine crystal structure has not been determined and only three pairs of polymorphic modifications has been found among its derivatives.20,21 The two polymorphs of acetyl 2-(N-(2-fluorophenyl)imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide are of special interest for studying due to the fact that different forms were crystallized from the same solution.20 The comparison of structures formed under different conditions gives the opportunity to discuss the principles of crystal formation and forces influencing it.

Crystal structure formation from molecules is one of the most intriguing processes. It may be visualized as a supramolecular reaction where the system of intermolecular interactions is generated under defined conditions (solution concentration, temperature, crystallization speed, etc.) similarly to a new molecule being generated as a result of a chemical reaction.22 Similar to a usual reaction, the crystallization process can occur under kinetic or thermodynamic control. A very fast crystallization from a supersaturated solution, rapid cooling, or rapid evaporation may be considered as kinetically controlled processes. Thermodynamical control is associated with slow evaporation, slow crystallization from the melt, or slow sublimation. Our recent study has shown that crystallization processes of different types may result in different arrangements of the molecules within the crystal phase.23

Molecular crystal formation principles have been studied for a long time. The first approach has been suggested by Kitaigorodsky who concluded that organic molecules crystallize according to close packing principle: “... the mutual arrangement of the molecules in a crystal is always such that the “projections” of one molecule fit into the “hollows” of adjacent molecules”.24 It is rather a physical model that considers a molecule as a whole particle and does not take into account its molecular structure. Etter presumed that the mutual positions of molecules in the crystal are caused not only by their forms but also the intermolecular interactions between them.25,26 Such interactions are apparently strong hydrogen bonds formed between defined functional groups. According to Etter’s rules, all possible hydrogen bonds between strong donors and proton acceptors must be formed during the crystallization process. This approach proved to be more chemical than Kitaigorodsky’s principles and allowed to explain different sets of intermolecular interaction formation. However, it is useless in case of the absence of strong hydrogen bonds. Desiraju’s supramolecular synthon concept is the most modern approach to understanding of crystal formation.27−29 This conception is based on the frequency of formation of defined strongly bound structural motifs in a lot of crystals and can be used for crystal engineering or crystal structure prediction.

Variety and development of quantum chemical methods result in new approaches to the crystal structure analysis.30−32 One of such approaches was proposed recently.33−35 It takes into account the basic molecule interactions with all molecules belonging to its first coordination sphere. All calculated interaction energies are normalized in relation to the strongest one. It results in comparison of relative energy values, not absolute ones. Such an approach proves to be independent of the calculation method36 and allows to study the role of different types of intermolecular interactions in crystal structure formation.

In the present study, we analyze two polymorphic modifications which were crystallized due to different speeds of the crystallization process. We investigated what types of intermolecular interactions are formed under kinetic or thermodynamic control of the supramolecular reaction and how the formed crystal structures differ.

Results and Discussion

Molecular and crystal structures of two acetyl 2-(N-(2-fluorophenyl)imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide (Scheme 1) polymorphic forms have been published earlier.20 It was found that the thin plate-like needles (I) were crystallized due to fast cooling of the boiling propanol solution to room temperature. The prismatic crystals (II) were formed as a result of slow evaporation. These crystallization processes may be considered as the supramolecular reactions which are controlled by physicochemical laws similar to traditional chemical reactions. Crystals I may be considered the product of the kinetically controlled supramolecular reaction while crystals II are the product of the thermodynamically controlled reaction.

Scheme 1. Acetyl 2-(N-(2-Fluorophenyl)imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide.

The situation in which two polymorphs are crystallized in the same solution simultaneously or in overlapping stages was named concomitant polymorphism and was thoroughly studied.37,38 The phenomenon of concomitant polymorphism is not very rare and give us an opportunity to answer some important questions

-

1.

How does conformation of the molecule in the crystals formed differ due to fast cooling or slow evaporation?

-

2.

Which types of intermolecular interactions can be formed in the first place under different conditions?

The main difference between polymorphs I and II is the conformation of acetyl 2-(N-(2-fluorophenyl)imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide as well as mutual positions of the molecules in the crystals. It remains unclear which conformation is more stable and how the crystal structures may be interpreted. A more detailed study of the acetyl 2-(N-(2-fluorophenyl)imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide molecular structure and crystal packing for two polymorphs seems to be very useful for a deeper understanding of the crystal structure formation process.

Molecular Structure Analysis

The molecular structure analysis of acetyl 2-(N-(2-fluorophenyl)imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide (Scheme 1) allows to presume high conformational rigidity. The extended π-system of the bi-cycle and substituents is expected to be planar due to maximal conjugation and the N–H···N intramolecular hydrogen bond formation. The most conjugative system is usually more energetically favorable. The C–H···O hydrogen bond between the fluorophenyl substituent and the cyclic oxygen atom may also be found in a planar conformation but this interaction is much weaker as compared to the N–H···N hydrogen bond and its role in the conformation stabilization is unclear.

As it was mentioned above, the 2-(N-(2-fluorophenyl)imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide molecular structures are different in two polymorphic forms. It is planar in crystal I and nonplanar in crystal II (Figure 1). The rotation around the N1–C10 bond can result in changing of conjugation extent between the exocyclic double bond and π-system of the fluorophenyl substituent and the C–H···O intramolecular hydrogen bond formation in the planar conformer. The N1–C10 and C1–O bond lengths are expected to be more influenced by such effects. However, comparison of the bond lengths has shown a very negligible difference (Table 1).

Figure 1.

2-(N-(2-Fluorophenyl)imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide molecular structures in polymorphic modifications I (on the left) and II (on the right) according to the X-ray diffraction data.

Table 1. Selected Geometrical Parameters for 2-(N-(2-Fluorophenyl)imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide in Polymorphic Forms I and II.

| parameter | polymorph I | polymorph II |

|---|---|---|

| Bond Lengths, Å | ||

| C1=N1 | 1.268(5) | 1.281(2) |

| N1–C10 | 1.402(5) | 1.407(3) |

| C1–O1 | 1.381(4) | 1.366(2) |

| C9–O1 | 1.376(4) | 1.382(2) |

| Bond Angles, deg | ||

| O1–C1=N1 | 120.7(3) | 119.6(2) |

| C1=N1–C10 | 126.3(3) | 124.2(2) |

| N1–C10–C15 | 129.7(4) | 126.2(2) |

| Torsion Angles, deg | ||

| C1=N1–C10–C15 | –9.4(7) | –51.8(3) |

| C3–C2–C16–N2 | 179.9(3) | 175.1(2) |

| C2–C16–N2–C17 | –175.6(4) | –172.6(2) |

| C16–N2–C17–O3 | –175.2(4) | 177.9(2) |

| Intramolecular hydrogen bonds | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H···A, Å | D–H···A, deg | H···A, Å | D–H···A, deg | |

| N–H···N | 1.97 | 142 | 1.95 | 144 |

| C–H···O | 2.21 | 120 | ||

To estimate the conjugation extent and the rotational barrier, both conformations found in the crystal phase were optimized using the m06-2x/cc-pVTZ method. Surprisingly, the nonplanar conformation appeared to be equilibrium while the planar conformation corresponded to the transition state between two equilibrium geometries (Figure 2). However, the difference in energy between transition and equilibrium geometries is very small and amounts to only 0.5 kcal/mol despite the C1=N1–C10–C10 torsion angle changing by almost ±50°.

Figure 2.

Molecular structure of two equilibrium states (along the edges) and transition state (in the middle) according to the quantum chemical calculations.

Conjugation degree between the exocyclic double bond and aromatic substituent for equilibrium and transition geometries may be compared using the characteristics of the (3,–1) critical bond point (BCP) within Bader’s atoms in molecules (AIM) theory39 or orbital interactions within the natural bond orbital (NBO) method.40 The results of the AIM analysis have shown a very small difference in the electron density and Laplacian of electron density for the (3,–1) BCP of the N1–C10 bond (Table 2). However, the ellipticity value indicates clearly a stronger conjugation in the planar geometry. The C1=N1 and N1–C10 bond orders also correspond to a stronger conjugation in the planar conformation (Table 3). Conjugation energy [E(2), kcal/mol] may be estimated as the intramolecular orbital interaction within the NBO theory. The energy of the π–π interactions between the exocyclic double bond and the aryl substituent is −38.2 kcal/mol for the planar conformation and −19.4 kcal/mol for the nonplanar equilibrium geometry.

Table 2. Characteristics of the (3,–1) BCP for the N1–C10 Bond within the AIM Theory (ρ—Value of Electron Density, ∇ρ—Laplacian of Electron Density, ε—Ellipticity) and Some Bond Orders within the NBO Method Calculated by m06-2x/cc-pVTZ Method.

| parameter | equilibrium geometry | transition state |

|---|---|---|

| (3,–1) BCP for the N1–C10 Bond | ||

| ρ, e/au3 | 0.293 | 0.295 |

| –∇ρ, e/au5 | –0.823 | –0.810 |

| ellipticity, ε | 0.034 | 0.046 |

| Bond Orders | ||

| C1=N1 | 1.689 | 1.665 |

| N1–C10 | 1.058 | 1.090 |

Table 3. Intermolecular Interactions and Their Geometric Characteristics in Polymorphic Crystals of I and II.

| geometrical

characteristics |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| interaction | symmetry operation | H···A, Å | D–H···A, deg |

| Crystal Structure I | |||

| C18–H···C4′ | –x, −y, 1 – z | 2.86 | 158 |

| C5–H···O2′ | –1 – x, −y, 1 – z | 2.46 | 159 |

| π···π′ | –1 + x, y, z | 3.29 | |

| Crystal Structure II | |||

| π···π′ | 1 – x, −y, −z | 3.37 | |

The energy of intramolecular hydrogen bonds may be estimated in accordance with Espinosa’s formula41 using the characteristics of the (3,–1) critical point for the corresponding nonbonded interactions. As was calculated, the energy of the C–H···O hydrogen bond is −3.7 kcal/mol, which is much smaller than the energy of the N–H···N intramolecular hydrogen bonds (−9.3 kcal/mol in a planar conformer and −9.2 kcal/mol in a nonplanar conformer).

Thus, we can conclude that the planar conformation of the studied molecule is less energetically stable despite stronger conjugation between an exocyclic double bond and the aromatic substituent and the presence of a weak C–H···O hydrogen bond. However, a very small rotation barrier allows to presume its existence in solution as well as two equilibrium nonplanar conformations.

To study the conformational transitions of the studied molecule and influence of the fluoro substituent and polarizing environment on the rotation around the N1–C10 bond, we have performed relaxed scanning of the C1=N1–C10–C15 torsion angle in the range ±170° with the step of 10° for unsubstituted and ortho-fluorosubstituted 2-(N-imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide. Full energy profiles for such a scanning calculated in vacuum and using the polarizable continuum model (PCM)42 with the dielectric constant of isopropanol have shown the very small rotation barrier around the N1–C10 bond in unsubstituted 2-(N-imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide (blue line) (0.6 kcal/mol). The presence of a fluoro substituent in the ortho-position results in a significant increase of the rotation barrier and appearance of two minima and two maxima on the energy profile (Figure 3, on the left). The most energetically favorable 2-(N-(2-fluorophenyl)imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide conformation corresponds to the geometry with the C1=N1–C10–C15 torsion angle of about ±130°. Two local minima correspond to the geometry with the torsion angle of about 40 and −40° and the energy of 1.9 kcal/mol relative to the global minimum. The planar conformation of the 2-(N-(2-fluorophenyl)imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide molecule is the least energetically favorable and its relative energy is 2.2 kcal/mol as compared to the global minimum and 0.6 kcal/mol as compared to the local minimum. Analyzing the experimental geometries and abovementioned calculations, we may conclude that we have obtained the conformation of the transition state in crystal I and two conformations corresponding to local minima in crystal II.

Figure 3.

Energy profile of the rotation around the N1–C10 bond in unsubstituted and ortho-fluorosubstituted molecules in vacuum (on the left) and taking into account the polarizing environment within the PCM model (solvent = isopropanol) according to the quantum chemical calculations by the m06-2x/cc-pVTZ method.

The modeling of a polarizing environment influence on the rotation process within the PCM model has shown some decreasing of the energy in total (Figure 3, on the right). However, the difference in energy between planar geometry and geometries corresponding to local minima is slightly higher as compared to vacuum (0.7 kcal/mol). We may presume that the polarizing environment promotes increasing of conjugation between the exocyclic double bond and the aromatic cycle.

Crystal Structure Analysis of Polymorphs I and II Using the Study of Geometrical Characteristics of Intermolecular Interactions

An acetyl 2-(N-(2-fluorophenyl)imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide molecule contains only one strong proton donor involved in the intramolecular hydrogen bond. Hence, only stacking interactions and weak intermolecular interactions like C–H···O or C–H···π hydrogen bonds may be formed.

Indeed, the analysis of short intermolecular contacts has revealed the C–H···O and C–H···π hydrogen bonds in structure I (Figure 4). The geometrical characteristics (Table 3) indicate that these hydrogen bonds are very weak. The C–H···O hydrogen bonds form the centrosymmetric dimer in which the studied molecules lie within a plane. The C–H···π hydrogen bonds form the nonplanar dimer in which the stacking interaction existence is ruled out due to the absence of overlapping between π-systems of the adjacent molecules (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Intermolecular hydrogen bonds in polymorphic structure I.

The extended π-system creates a precondition for the stacking interaction formation. The interactions of such a type have been found in both polymorphic modifications. However, the adjacent molecules are oriented in the “head-to-head” way and shifted relatively to each other in structure I (Figure 5). As a result, the overlapping degree is small enough and the stacking is provided by interaction between the pyrane and fluorophenyl cycles. In contrast to structure I, the stacked molecules are oriented in the “head-to-tail” way and their overlapping degree is much higher in structure II (Figure 5). It can be expected that such an interaction should be stronger but the distance between interacting π-systems is longer in structure II (Table 3) which weakens the interaction.

Figure 5.

Stacking interactions in crystals I (on the left) and II (on the right).

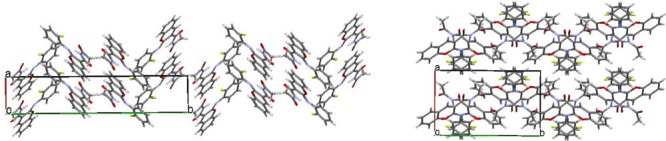

A detailed analysis of the crystal structures has shown that columns may be recognized in crystal structure I while no structural motif can be separated out in structure II (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Crystal structures of polymorphic modification I (on the left) and II (on the right).

A very useful method to compare polymorphic modifications is the analysis of their Hirshfeld surfaces and 2D fingerprint plots43,44 using the CrystalExplorer program.45 Hirshfeld surfaces show clearly the localization of short contacts areas (Figure 7) (marked red), which are slightly different in structures I and II. The short contacts areas were found at both carbonyl oxygens in two structures, indicating H···O/O···H interactions. Structure I differs from structure II by the presence of a short contact area at the aryl substituent that indicated interaction between the pyrane and fluorophenyl cycles.

Figure 7.

Hirshfeld surfaces with the mapped dnorm property for molecules in structures I (on the left) and II (on the right) projected and transparent to show the conformation of the molecules.

The fingerprint plots are constructed as the combination of the short de (external distance, vertical axes) and di (internal distance, horizontal axes) and allow to estimate the percentage contribution of each type of contacts to the total Hirshfeld surface area. The sharper spikes on the fingerprint plot correspond to stronger interactions in polymorph II as compared to structure I. It can be noted that the relationship between different types of interactions differs in structures I and II (Figure 8). We can see much stronger H···O/O···H and C···C stacking interactions in structure II. Structure I is characterized by stronger H···C/C···H interactions.

Figure 8.

2D Hirshfeld fingerprint plots for structures I (on the left) and II (in the middle). Relative contribution of different types of intermolecular interactions to the total Hirshfeld surface area (in %) is shown as the histogram (on the right).

Crystal Structure Analysis of Polymorphs I and II Based on the Study of Intermolecular Interaction Energies

The analysis of intermolecular interactions and their geometrical characteristics indicates clearly the difference between two 2-(N-(2-fluorophenyl)imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide polymorphic modifications. However, such an analysis is rather qualitative than quantitative due to the fact that the interactions of different types are very complicated to be compared. Moreover, such an analysis does not take into account nonspecific interactions like those of general dispersion or electrostatic ones which can also influence mutual positions of the molecules in the crystal phase.

Difference between polymorphic structures can be discussed using comparison of their calculated lattice energies. Such calculations have been performed using the PBE functional with D3 empirical dispersion corrections implemented in the Quantum ESPRESSO program.46 According to the obtained data, polymorph II has a lower lattice energy compared to polymorph I and the difference amounts to 0.86 kcal/mol. Earlier, it has been revealed that the difference in lattice energies between five coumarin polymorphs does not exceed 0.5 kcal/mol.19

The recently suggested approach to the crystal structure analysis based on the study of pairwise interaction energies between molecules using quantum chemical calculations proved to be more thorough.33−36 Application of this approach results in a quantitative analysis of interaction energies topology in the crystal structures instead of a qualitative description of geometric characteristics or estimation of total lattice energy.

To compare I and II structures formed due to the kinetically or thermodynamically controlled crystallization process, we performed the above-mentioned crystal structure analysis. The first coordination sphere of the basic molecule contains 15 adjacent molecules in both polymorphic modifications. However, the interaction energy of the basic molecule with all molecules belonging to the first coordination sphere is different and amounts to −84.0 kcal/mol in structure I and to −86.1 kcal/mol in structure II.

The basic molecule interacts strongly with two neighboring molecules (dimers dI_1 and dI_2, Table 4), which results in the formation of a column as the primary basic structural motif (BSM) (Figure 9) in crystal I. The molecules within the column are bound by the stacking interactions with a “head-to-head” orientation of the interacting ones. Such a type of stacking interaction is less effective compared to a “head-to-tail” stacking due to the essential shift of the molecules relatively to each other. The interaction energy of the basic molecule with two neighboring molecules within the column is −31.5 kcal/mol (or 37.6% of the total interaction energy with all molecules of the first coordination sphere).

Table 4. Symmetry Codes, Bonding Type, Interaction Energy of the Basic Molecule with Neighboring Ones (Eint, kcal/mol) with the Highest Values (More Than 5% of the Total Interaction Energy) and the Contribution of This Energy to the Total Interaction Energy (%) in Crystals I and II.

| dimer | symmetry operation | Eint, kcal/mol | contribution to the total interaction energy, % | interaction type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorph I | ||||

| dI_1 | 1 + x, y, z | –15.8 | 18.8 | stacking |

| dI_2 | –1 + x, y, z | –15.8 | 18.8 | stacking |

| dI_3 | –x, −y, 1 – z | –10.9 | 13.0 | nonspecific |

| dI_4 | –1 – x, −y, 1 – z | –8.9 | 10.6 | C–H···O |

| dI_5 | 0.5 + x, 0.5 – y, –0.5 + z | –4.7 | 5.5 | C–H···π |

| dI_6 | –0.5 + x, 0.5 – y, 0.5 + z | –4.7 | 5.5 | C–H···π |

| dI_7 | 0.5 + x, 0.5 – y, 0.5 + z | –4.2 | 5.0 | nonspecific |

| dI_8 | –0.5 + x, 0.5 – y, –0.5 + z | –4.2 | 5.0 | nonspecific |

| Polymorph II | ||||

| dII_1 | 1 – x, −y, −z | –16.0 | 18.6 | stacking |

| dII_2 | x, 0.5 – y, 0.5 + z | –15.2 | 17.6 | stacking |

| dII_3 | x, 0.5 – y, –0.5 + z | –15.2 | 17.6 | stacking |

| dII_4 | –x, −y, −z | –9.4 | 10.9 | nonspecific |

Figure 9.

Column along the a crystallographic direction as the primary BSM shown as packing of molecules (a) and energy-vector diagrams (b) (projection along the b crystallographic direction) and packing of the columns, in terms of energy-vector diagrams (c) (projection along the a crystallographic direction) in structure I. The double column is highlighted blue.

The interaction energies between the neighboring columns are not equal. The basic molecule interaction with one of the adjacent columns is much stronger and amounts to −19.9 kcal/mol (or 23.6% of the total interaction energy of the basic molecule). This interaction is provided by the C–H···O hydrogen bond and nonspecific interactions. The interaction energy of the basic molecule with molecules belonging to the other neighboring column is more isotropic and varies in the range of −6.0/–8.8 kcal/mol. Thus, we can separate out the double columns as the secondary BSM (Figure 9).

In contrast to structure I, the basic molecule forms three strongest interactions in structure II (dimers dII_1, dII_2, and dII_3, Table 4). As a result, the honeycomb-like layer may be recognized as the primary BSM in structure II (Figure 10). The molecules within the layer are bound by the stacking interactions of two types (Figure 11): (a) the “head-to-tail” stacking between two bi-cyclic fragments (dimer dII_1); (b) the stacking between the pyrane and fluorophenyl cycles (dimer dII_2). The interaction energy of the basic molecule within the layer is −46.5 kcal/mol (or 53.8% of the total interaction energy of the basic molecule with all molecules belonging to its first coordination sphere). The interaction between neighboring layers is much weaker and is provided by nonspecific interactions.

Figure 10.

Layer parallel to the bc crystallographic plane, projection along the a crystallographic direction (on the left) and packing of the layer, projection along the c crystallographic direction (on the right) in structure II. The layer is highlighted in red.

Figure 11.

Stacked dimers with the strongest interaction energy in structure II.

We compared the results of the crystal structure complex analysis (Table 5) and came to the conclusion that different conditions of the crystallization process result in the formation of two types of crystal structures. The structure with the higher crystal density is formed due to a fast crystallization process but the molecule has nonequilibrium conformation in this crystal and forms several interactions of different types. The analysis of pairwise interaction energies has revealed the columnar type of this crystal structure and more isotropic distribution of the interaction energies between molecules within the crystal. A slow crystallization process results in the formation of a less-dense crystal structure. However, the molecule adopts the equilibrium conformation within this crystal and forms only two types of strong stacking interactions. It leads to a layered crystal structure formation with an anisotropic enough distribution of the interaction energies between molecules within the crystal.

Table 5. Comparison of the Polymorphic Modifications I and II.

| parameter | polymorph I | polymorph II |

|---|---|---|

| crystallization process | fast | slow |

| crystal density, g/cm3 | 1.441 | 1.415 |

| molecular conformation | transition state | local minima |

| packing type | columnar | layered |

| intermolecular interactions | several weak enough interactions of different types | two types of the strong stacking interactions |

| total interaction energy of the basic molecule, kcal/mol | –84.0 | –86.1 |

| relative lattice energy, kcal/mol | 0.86 | 0 |

| energetic structure | more isotropic | less isotropic |

Conclusions

The application of modern quantum chemical methods for the molecular and crystal structure analysis of two polymorphic modifications formed from the same solution allows to obtain much more information compared to the usual X-ray study. Despite the conjugation between the exocyclic C1=N1 double bond and aromatic fluorophenyl substituent, the rotation around the N1–C10 bond at almost ±50° results in a very small change in energy. The roles of a fluoro substituent and a solvent polarizing influence on conformational equilibrium have been studied using scanning of the C1=N1–C10–C15 torsion angle from −170° up to +170°. It has been shown that conformation corresponded to the transition state, which has been revealed in the crystal formed due to the fast crystallization process. Two symmetrical conformers corresponding to the local minima have been found in the crystal obtained as a result of slow evaporation. The difference in energy between these conformations is very small and amounts to 0.5 kcal/mol.

The study of pairwise interaction energies in two polymorphic modifications aims to understand some regularities of the crystal formation process. Being a supramolecular reaction, the crystallization process is ruled by general physicochemical laws just as a usual chemical reaction. Rapid cooling of the supersaturated isopropanol solution may be considered as a kinetically controlled process of crystal formation. It results in the formation of a denser crystal with conformation of the studied molecule corresponding to the transition state, smaller total interaction energy of the basic molecule with all molecules belonging to its first coordination sphere, and more isotropic columnar structure. At that, several types of weak enough intermolecular interactions are formed. Slow evaporation of the same solution can be associated with a thermodynamically controlled process of crystal formation. It leads to the formation of a crystal structure with a lower density but the molecule adopts the conformations corresponding to local minima on the potential energy surface and interacts strongly with several of the neighboring molecules. The formed crystal may be recognized as layered according to the crystal structure analysis based on the comparison of pairwise interaction energies between molecules. Such a type of crystal structure is caused by the formation of two types of strong enough stacking interactions.

Experimental Section

Crystallization

The crystallization of acetyl 2-(N-(2-fluorophenyl)imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide was restudied using different solvents and process conditions. The crystallization from the methanol, ethanol, acetonitrile results in polymorph I. Polymorph II has been obtained due to crystallization from less volatile solvents such as toluene, DMF. To exclude the influence of specific interactions with solvent molecules, we have studied two crystal structures obtained from the same solution of isopropanol under carefully matched conditions. Polymorph I was crystallized due to fast cooling of the saturated solution while polymorph II was obtained as a result of slow evaporation of the same unsaturated solution (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Needle-like crystals of polymorph I (on the left) and prismatic crystals of polymorph II (on the right).

Crystal data and reflections were measured on the “Xcalibur-3” diffractometer at the room temperature (graphite monochromated Mo Kα radiation, CCD detector, ω-scanning). The structures were solved by a direct method using the SHELXTL package.47 Positions of the hydrogen atoms were located from electron density difference maps and refined using the “riding” model with Uiso = nUeq of the carrier atom where n = 1.5 for the methyl group and 1.2 otherwise. All experimental data and structure refinement details are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6. Crystal Data and Selected Refinement Parameters for Structures I and II.

| parameter | polymorph I | polymorph II |

|---|---|---|

| crystal system | monoclinic | |

| space group | P21/n | P21/c |

| a, Å | 5.1549(11) | 8.9431(6) |

| b, Å | 25.530(5) | 14.3633(9) |

| c, Å | 11.335(2) | 12.0397(7) |

| β, deg | 94.90(1) | 100.085(6) |

| unit cell volume, Å3 | 1486.3(5) | 1522.6(2) |

| T, K | 293 | 293 |

| Z, Z′ | 4, 1 | 4, 1 |

| calculated density, mg m–3 | 1.449 | 1.415 |

| μ (mm–1) | 0.109 | 0.106 |

| reflections measured | 9567 | 11032 |

| reflections independent | 2610 | 2685 |

| Rint | 0.112 | 0.054 |

| final R1 values (I > 2σ(I)) | 0.062 | 0.052 |

| final wR(F2) values (I > 2σ(I)) | 0.116 | 0.139 |

| goodness-of-fit on F2 | 0.880 | 1.055 |

| CCDC | 2043571 | 2043572 |

The final atomic coordinates and crystallographic data for the studied molecule have been deposited to The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, CB2 1EZ, UK (fax: +44-1223-336033; e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk). The deposition numbers are given in Table 1.

Molecular Structure Study

The quantum chemical calculations were performed using density functional theory with the m06-2x functional48 and standard cc-pVTZ basis set49 (m06-2x/cc-pVTZ). The character of the stationary points on the potential energy surface was verified by calculations of vibrational frequencies within the harmonic approximation using analytical second derivatives at the same level of theory. All stationary points possess zero (minima) or one (saddle point) imaginary frequencies. The saddle point for the rotation around the N–Car bond was located using the standard optimization technique.50,51 The rotation barrier was calculated as the difference between the energies of the true minima and saddle point geometrical structures. All calculations were performed using the Gaussian09 program.52

The electron density distribution analysis was carried out within Bader’s AIM approach39 using the m06-2x/cc-pVTZ wave function. AIM analysis has been performed using the AIM2000 program53 with all default options. The intramolecular interactions were investigated on the basis of the natural bonding orbitals theory40 with the NBO 5.0 program.54 The calculations were performed using the m06-2x/cc-pVTZ wave function. The conjugative interactions are referred to as “delocalization” corrections to the zeroth-order natural Lewis structure. For each donor NBO (i) and acceptor NBO (j), the stabilization energy E(2)associated with delocalization (“2e-stabilization”) i → j is estimated as

where qi is the donor orbital occupancy, εj and εi are the diagonal elements (orbital energies), and F(i,j) is the off-diagonal NBO Fock matrix element.

Crystal Structure Analysis

The analysis of the supramolecular architecture of the crystals was performed using the pairwise energetic approach that was suggested earlier.34−36 The first coordination sphere of the basic molecule (BM) was determined using the “molecular shell calculation” option in the Mercury program (version 3.1).55 This option allows to find all molecules for which the distance between atoms of the basic molecule and its symmetric equivalent is shorter than van der Waals radii sum plus 1 Å at least for one pair of atoms. The Ei energy of the intermolecular interaction of a BM with one of its nearest neighbors was calculated using the B97-D3/def2-TZVP density functional method56−58 and corrected for basis set superposition errors using the counterpoise procedure.59 All the calculations were performed using the ORCA program.60

Each molecule in the crystal may be represented by its geometric center. Given a BM of geometric center C0, each energy vector Li of pairwise attractive interaction is originated from C0, directed toward the neighbor geometric center Ci, and assigned with the algebraic length Li = RiEi/(2E1), where Ri is a distance between geometric centers of interacting molecules, Ei is the interaction energy, and E1 = Estr is the energy of the strongest interaction.33 The E1-normalization gives L1 = R1/2 for the most strongly interacting neighbor 1, and Li ≤ Ri/2 for i ≥ 2. The Li’s values of a molecule in the asymmetric unit must be multiplied by all the symmetry operations of the crystal, until each of the N neighboring molecules is connected to C0 by a vector. The local energy-vector diagram (EVD) reflects the local spatial distribution of intermolecular interactions energies. The set of all the EVDs in the crystal lattice gives a global topography of intermolecular interactions energies. Each molecule is characterized by the total interaction energy Etot, obtained by summing up the Ei values over 1 ≤ i ≤ N. Values of E1 for the strongest interactions between molecules are listed in Table 4. A complete list of interactions energies is included in the Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c05516.

Full tables of pairwise interaction energies between molecules and the figures of crystal packing along different crystallographic directions in terms of molecules and EVDs (PDF)

Author Contributions

S.V.S. performed the quantum chemical calculations, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript; V.N.B. crystallized the crystals; S.M.K. contributed to the crystal structure analysis; P.V.T. made Hirshfeld surfaces and 2D fingerprint plots analysis; and N.D.B. made the periodic calculations.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Coumarins: Biology, Applications, and Mode of Action; O’Kennedy R.; Thomas R. D., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, U.K., 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Estévez-Braun A.; González A. G. Coumarins. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1997, 14, 465–475. 10.1039/np9971400465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray R. D. H. Coumarins. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1995, 12, 477–505. 10.1039/np9951200477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D.; Chen T.; Ye D.; Xu J.; Jiang H.; Chen K.; Wang H.; Liu H. Cell-permeable iminocoumarine-based fluorescent dyes for mitochondria. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 2884–2887. 10.1021/ol200908r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekar N. Coumarin dyes in laser technology. Colourage 2003, 50, 55–56. [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu K.; Urano Y.; Kojima H.; Nagano T. Development of an iminocoumarin-based Zinc sensor suitable for ratiometric fluorescence imaging of neuronal Zinc. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 13447–13454. 10.1021/ja072432g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abid-Jarraya N.; Turki-Guermazi H.; Khemakhem K.; Abid S.; Saffon N.; Fery-Forgues S. Investigations in the methoxy-iminocoumarin series: Highly efficient photoluminescent dyes and easy preparation of green-emitting crystalline microfibers. Dyes Pigm. 2014, 101, 164–171. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2013.09.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abid-Jarraya N.; Khemakhem K.; Turki-Guermazi H.; Abid S.; Saffon N.; Fery-Forgues S. Solid-state fluorescence properties of small iminocoumarin derivatives and their analogues in the coumarin series. Dyes Pigm. 2016, 132, 177–184. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2016.04.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh I.; Kaur H.; Kumar S.; Kumar A.; Lata S.; Kumar A. Synthesis of new coumarin derivatives as antibacterial agents. Int. J. ChemTech Res. 2010, 2, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar]

- Sardari S.; Mori Y.; Horita K.; Micetich R. G.; Nishibe S.; Daneshtalab M. Synthesis and antifungal activity of coumarins and angular furanocoumarins. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999, 7, 1933–1940. 10.1016/s0968-0896(99)00138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkiacharian S.; Thuy D. T.; Sicsic S.; Bakhchinian R.; Kurkjian R.; Tonnaire T. Structure-activity relationships of some 3-substituted-4-hydroxycoumarins as HIV-1 protease inhibitors. Farmaco 2002, 57, 703–708. 10.1016/s0014-827x(02)01264-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuravel’ I. O.; Kovalenko S. M.; Ivachtchenko A. V.; Balakin K. V.; Kazmirchuk V. V. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of 5-hydroxymethyl-8-methyl-2-(N-arylimino)-pyrano[2,3-c]pyridine-3-(N-aryl)-carboxamides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 5483–5487. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.08.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwish E.; Fattah A.; Attaby F.; Al-Shayea O. Synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation of some novel thiazole, pyridine, pyrazole, chromene, hydrazone derivatives bearing a biologically active sulfonamide moiety. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 1237–1254. 10.3390/ijms15011237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edraki N.; Firuzi O.; Foroumadi A.; Miri R.; Madadkar-Sobhani A.; Khoshneviszadeh M.; Shafiee A. Phenylimino-2H-chromen-3-carboxamide derivatives as novel small molecule inhibitors of β-secretase (BACE1). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 2396–2412. 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edraki N.; Firuzi O.; Fatahi Y.; Mahdavi M.; Asadi M.; Emami S.; Divsalar K.; Miri R.; Iraji A.; Khoshneviszadeh M.; Firoozpour L.; Shafiee A.; Foroumadi A. N-(2-(Piperazin-1-yl)phenyl)arylamide derivatives as β-secretase (BACE1) inhibitors: simple synthesis by Ugi four-component reaction and biological evaluation. Arch. Pharm. 2015, 348, 330–337. 10.1002/ardp.201400322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo S.; Matsunaga T.; Kuwata K.; Zhao H.-T.; El-Kabbani O.; Kitade Y.; Hara A. Chromene-3-carboxamide derivatives discovered from virtual screening as potent inhibitors of the tumour maker, AKR1B10. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 2485–2490. 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo S.; Hu D.; Suyama M.; Matsunaga T.; Sugimoto K.; Matsuya Y.; El-Kabbani O.; Kuwata K.; Hara A.; Kitade Y.; Toyooka N. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship of 2-phenyliminochromene derivatives as inhibitors for aldo-keto reductase (AKR) 1B10. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 6378. 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edraki N.; Iraji A.; Firuzi O.; Fattahi Y.; Mahdavi M.; Foroumadi A.; Khoshneviszadeh M.; Shafiee A.; Miri R. 2-Imino 2H-chromene and 2-(phenylimino) 2H-chromene 3-aryl carboxamide derivatives as novel cytotoxic agents: synthesis, biological assay, and molecular docking study. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2016, 13, 2163–2171. 10.1007/s13738-016-0934-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shtukenberg A. G.; Zhu Q.; Carter D. J.; Vogt L.; Hoja J.; Schneider E.; Song H.; Pokroy B.; Polishchuk I.; Tkatchenko A.; Oganov A. R.; Rohl A. L.; Tuckerman M. E.; Kahr B. Powder diffraction and crystal structure prediction identify four new coumarin polymorphs. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 4926–4940. 10.1039/c7sc00168a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko S. N.; Baumer V. N.; Rusanova S. V.; Chernykh V. P. Two crystal modifications for the product of the acetylation of 2-N-(2-fluorophenyl)iminocoumarin-3-carboxamide. Z. Kristallogr. 1999, 214, 580–583. 10.1524/zkri.1999.214.9.580. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shishkina S. V.; Konovalova I. S.; Kovalenko S. M.; Trostianko P. V.; Geleverya A. O.; Nikolayeva L. L.; Bunyatyan N. D. Influence of ortho-substituent on the molecular and crystal structures of 2-(N-aryl-imino)coumarin-3-carboxamide: isotypic and polymorphic astructures. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci., Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2019, 75, 887–902. 10.1107/s2052520619010485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aakerüy C. B.; Beatty A. M.; Helfrich B. A. “Total synthesis” supramolecular style: design and hydrogen-bond-directed assembly of ternary supermolecules. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 3240–3242. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shishkina S. V.; Baumer V. N.; Khromileva O. V.; Kucherenko L. I.; Mazur I. A. The formation of two thiotriazoline polymorphs: study from the energetic viewpoint. CrystEngComm 2017, 19, 2394–2401. 10.1039/c7ce00117g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaigorodsky A. I.Molecular Crystals and Molecules; Academic Press: New York and London, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Etter M. C. Encoding and decoding hydrogen-bond patterns of organic compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 1990, 23, 120–126. 10.1021/ar00172a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Etter M. C. Hydrogen bonds as design elements in organic chemistry. J. Phys. Chem. 1991, 95, 4601–4610. 10.1021/j100165a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Desiraju G. R. Supramolecular synthons in crystal engineering – a new organic synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 2311–2327. 10.1002/anie.199523111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Desiraju G. R. Chemistry beyond the molecule. Nature 2001, 412, 397–400. 10.1038/35086640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desiraju G. R. Hydrogen bridges in crystal engineering: interactions without borders. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 565–573. 10.1021/ar010054t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunitz J. D.; Gavezzotti A. Toward a quantitative description of crystal packing in terms of molecular pairs: application to the hexamorphic crystal system, 5-methyl-2-[(2-nitrophenyl)amino]-3-thiophenecarbonitrile. Cryst. Growth Des. 2005, 5, 2180–2189. 10.1021/cg050098z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunitz J. D.; Gavezzotti A. How molecules stick together in organic crystals: weak intermolecular interactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 2662. 10.1039/b822963p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavezzotti A. The lines-of-force landscape of interactions between molecules in crystals; cohesive versus tolerant and “collateral damage” contact. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci. 2010, 66, 396–406. 10.1107/s0108768110008074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shishkin O. V.; Dyakonenko V. V.; Maleev A. V.; Schollmeyer D.; Vysotsky M. O. Columnar supramolecular architecture of crystals of 2-(4-iodophenyl)-1,1—phenantroline derived from values of intermolecular interaction energy. CrystEngComm 2011, 13, 800–805. 10.1039/c0ce00246a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shishkin O. V.; Dyakonenko V. V.; Maleev A. V. Supramolecular architecture of crystals of fused hydrocarbons based on topology of intermolecular interactions. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 1795–1804. 10.1039/c2ce06336k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shishkin O. V.; Zubatyuk R. I.; Shishkina S. V.; Dyakonenko V. V.; Medviediev V. V. Role of supramolecular synthons in the formation of the supramolecular architecture of molecular crystals revisited from an energetic viewpoint. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 6773–6786. 10.1039/c3cp55390f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shishkin O. V.; Zubatyuk R. I.; Maleev A. V.; Boese R. Investigation of topology of intermolecular interactions in the benzene-acetylene co-crystal by different theoretical methods. Struct. Chem. 2014, 25, 1547–1552. 10.1007/s11224-014-0413-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein J.; Davey R. J.; Henck J.-O. Concomitant polymorphs. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 3440–3461. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein J.Polymorphism in Molecular Crystals; Claredon Press: Oxford, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bader R. F. W.Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory; Claredon Press: Oxford, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Weinhold F.Natural bond orbital methods. Encyclopedia of Computational Chemistry; Schleyer P. v. R., Allinger N. L., Clark T., Gasteiger J., Kollman P. A., Schaefer H. F. III, Schreiner P. R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, U.K., 1998; Vol. 3, pp 1792–1811. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa E.; Molins E.; Lecomte C. Hydrogen bond strengths revealed by topological analyses of experimentally observed electron densities. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1998, 285, 170–173. 10.1016/s0009-2614(98)00036-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi J.; Mennucci B.; Cammi R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2999–3094. 10.1021/cr9904009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spackman M. A.; Jayatilaka D. Hirshfeld surface analysis. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 19–32. 10.1039/b818330a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spackman M. A.; McKinnon J. J. Fingerprinting intermolecular interactions in molecular crystals. CrystEngComm 2002, 4, 378–392. 10.1039/b203191b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner M. J.; McKinnon J. J.; Wolff S. K.; Grimwood D. J.; Spackman P. R.; Jayatilaka D.; Spackman M. A.. CrystalExplorer17; University of Western Australia, 2017, http://hirshfeldsurface.net.

- Giannozzi P.; Baroni S.; Bonini N.; Calandra M.; Car R.; Cavazzoni C.; Ceresoli D.; Chiarotti G. L.; Cococcioni M.; Dabo I.; Dal Corso A.; de Gironcoli S.; Fabris S.; Fratesi G.; Gebauer R.; Gerstmann U.; Gougoussis C.; Kokalj A.; Lazzeri M.; Martin-Samos L.; Marzari N.; Mauri F.; Mazzarello R.; Paolini S.; Pasquarello A.; Paulatto L.; Sbraccia C.; Scandolo S.; Sclauzero G.; Seitsonen A. P.; Smogunov A.; Umari P.; Wentzcovitch R. M. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software protect for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2009, 21, 395502. 10.1088/0953-8984/21/39/395502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 2008, 64, 112–122. 10.1107/s0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Truhlar D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2007, 120, 215–241. 10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall R. A.; Dunning T. H. Jr.; Harrison R. J. Electron affinities of the first-row atoms revisited. Systematic basis sets and wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 96, 6796–6806. 10.1063/1.462569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helgaker T. Transition-state optimizations by trust-region image minimization. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1991, 182, 503–510. 10.1016/0009-2614(91)90115-p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Culot P.; Dive G.; Nguyen V. H.; Ghuysen J. M. A quasi-Newton algorithm for first-order saddle-point location. Theor. Chim. Acta 1992, 82, 189–205. 10.1007/bf01113251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision B.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford CT, 2010.

- Biegler-Konig F.; Schonbohm J.; Bayles D. AIM2000-A program to analyze and visualize atoms in molecules. J. Comput. Chem. 2001, 22, 545–559. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glendening E. D.; Badenhoop J. K.; Reed A. E.; Carpenter J. E.; Bohmann J. A.; Morales C. M.; Weinhold F.. NBO 5.0 Theoretical Chemistry Institute, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, 2001.

- Macrae C. F.; Bruno I. J.; Chisholm J. A.; Edgington P. R.; McCabe P.; Pidcock E.; Rodriguez-Monge L.; Taylor R.; van de Streek J.; Wood P. A. Mercury CSD 2.0 – new features for the visualization and investigation of crystal structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 466–470. 10.1107/s0021889807067908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2006, 27, 1787–1799. 10.1002/jcc.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Ehrlich S.; Goerigk L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. 10.1002/jcc.21759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Antony J.; Ehrlich S.; Krieg H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) fort he 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boys S. F.; Bernardi F. The calculation of small molecular interactions by the differences of separate total energies. Some procedures with reduced errors. Mol. Phys. 1970, 19, 553–566. 10.1080/00268977000101561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neese F.ORCA 2.8.0; Universitaet Bonn: Germany, 2010.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.