Abstract

Sorafenib is one of the most effective target therapeutic agents for patients with late-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. To seek possible alternative adjuvant agents to enhance the efficacy and improve the side effect of sorafenib, Hedyotis diffusa, one of the most prescribed phytomedicines for treating liver cancer patients in Taiwan, was evaluated in this work. We hypothesized that H. diffusa extract is a safety herb combination on the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of sorafenib. We designed treatments of sorafenib in combination with or without H. diffusa extract to examine its pharmacokinetic properties and effects on liver inflammation. The HPLC–photodiode-array method was designed for monitoring the plasma level and pharmacokinetic parameter of sorafenib in rat plasma. The pharmacokinetic results demonstrated that the area under the curve of sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.) in combination with various doses of H. diffusa formulation (1, 3, and 10 g/kg, p.o.) for 5 consecutive days were 5560 ± 1392, 7965 ± 2055, 7271 ± 1371, and 8821 ± 1705 min μg/mL, respectively, no significant difference when compared with sorafenib treatment alone. Furthermore, the hepatic activity in rats administered with sorafenib with/without H. diffusa extract was quantitatively scored by modified hepatic activity index grading. H. diffusa extract in the range of 1 to 10 g/kg per day did not elicit significant herb-induced hepatotoxicity in rats, based on the histopathological study. Consequently, our findings provided positive safety outcomes for the administration of sorafenib in combination with the phytomedicine H. diffusa.

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a common primary malignant liver tumor, and the number of cancer-related deaths and the cancer-related mortality rate continue to increase annually, especially in countries in Asia and Africa.1 The prognosis and outcomes after HCC treatment are generally based on the liver cancer staging system and Child–Pugh liver function classification at the time of the initial diagnosis. To date, surgical resection and liver transplantation are the best curative therapies for primary liver cancer.2−4 Other therapeutic options, such as percutaneous ablation, provide a high chance of cure in patients with early- and intermediate-stage HCC.5 Thus, HCC remains a difficult-to-treat cancer.6,7 Only rarely can HCC patients be treated with curative therapy due to their poor liver function reserve and high recurrence rate in the remnant liver. For patients with late-stage HCC, sorafenib has been used as a standard target agent for suppressing the tumor growth with a mechanism to block the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor as well as platelet-derived growth factor receptor signaling pathways. Additionally, sorafenib exhibits anti-proliferative effects on HCC cells by restraining the tyrosine kinase KIT receptor along with serine/threonine kinases in the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway.

To improve treatment effects, the administration of combination therapies that include synergistic agents such as novel systemic molecular-targeted drugs or traditional herbal medicines has become a new therapeutic approach. The search continues for appropriate drugs that work synergistically with sorafenib to improve its efficacy as well as increase patient survival.8−10 Meanwhile, many cancer patients seek out complementary and alternative medicines as an alternative therapy, possibly due to the cultural difference and the unsatisfactory outcome and severe side effects associated with a traditional chemotherapeutic agent.11−13 An Italian multicenter survey in 2017 published by Berretta et al. concluded that nearly 48.9% of cancer patients ever accepted complementary and alternative medicine.12,14 Kristoffersen et al. reported that approximately 33.4% of the surveyed Norwegian cancer patients once accepted traditional and complementary medicine, 13.6% had consulted with their health care provider, 17.9% had ever used alternative medicine or natural remedies, and 6.4% had practiced related techniques themselves.15

In 2017, a large-scale pharmacoepidemiological study acquired from the National Health Insurance database in Taiwan reported that Hedyotis diffusa (Oldenlandia diffusa), Rhizoma Rhei, and the herbal formulation of Xiao Chai Hu Tang and Gan Lu Yin were considered the most important herbal prescriptions for liver cancer patients.16H. diffusa is a famous medicinal plant and Chinese prescription in China. It is used to treat hepatitis, tonsillitis, urinary tract infection, and malignant tumors of the liver, stomach, and lung.17 In vitro studies have shown that H. diffusa extract exhibited promising antiproliferative activities against several cancer cell lines and induced a significant increase in apoptosis.18−25 Experiments of chemical-induced HCC with a liver cirrhosis model in rats showed that the extract of H. diffusa has anti-proliferative activity and inhibits metastasis and apoptosis.17 Several in vivo experiments clarified that H. diffusa can inhibit the growth of cancer cells such as breast cancer,19,20 colorectal cancer,21,22 lung cancer,23,24 and bladder cancer.25 As mentioned above, cancer patients have been treated with the concurrent use of clinical medicines and H. diffusa to reduce their symptoms. However, the therapeutic efficacy and pharmacological mechanism of H. diffusa are still unclear.

Based on the survey above, both sorafenib and H. diffusa extract possess efficacy against HCC. However, to date, no studies in the literature have reported herb–drug interactions for sorafenib and H. diffusa. Therefore, our hypothesis is that H. diffusa extract is a safety herb combination on the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of sorafenib. To investigate their pharmacokinetic interaction, experimental rats were divided into three groups: first group: sorafenib only at different doses (10, 20, and 40 mg/kg, p.o.), second group: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.) pretreatment with different doses of H. diffusa extract (1, 3, and 10 g/kg/day, p.o., for 5 consecutive days) and third group: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.) pretreatment with different doses of H. diffusa extract (1, 3, and 10 g/kg/day, p.o.) for 5 consecutive days and 2 weeks to investigate the herb/drug-induced hepatotoxic effects.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chromatographic Analysis

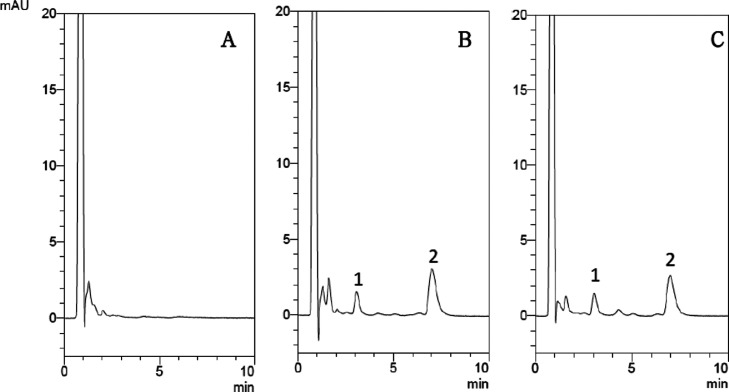

The level of sorafenib in rat plasma was determined by using the isocratic HPLC method. To make the separation and symmetry of the analyte peaks as good as possible, an organic solvent and a buffer solution were used. The optimal condition of the mobile phase for isocratic separation of sorafenib was acetonitrile: 10 mM KH2PO4 (45:55, v/v, pH 3.0). The analyte was fully separated and shows the highest symmetrical peak pattern. The retention times of sorafenib and the internal standard on the chromatogram were 7.1 and 3.1 min, respectively. The HPLC chromatograms in Figure 1 including blank plasma, sorafenib standard solution (5 μg/mL) spiked into blank plasma, and a real sample that was collected 2 h after sorafenib administration(10 mg/kg, p.o.) show sharp waveform features without significant overlap with interfering signals. Method validation showed that the analytical method of this experiment had satisfactory precision and accuracy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

UHPLC chromatograms of (A) blank plasma, (B) blank plasma spiked with sorafenib (5 μg/mL), and (C) the plasma sample (sorafenib; 10 μg/mL) at 2 h after sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.) administration; 1: retention time of the internal standard (diethylstilbestrol; 10 μg/mL): 3.1 min, 2: retention time of sorafenib: 7.1 min.

2.2. Dose-Dependent Pharmacokinetic Properties of Sorafenib in Rats

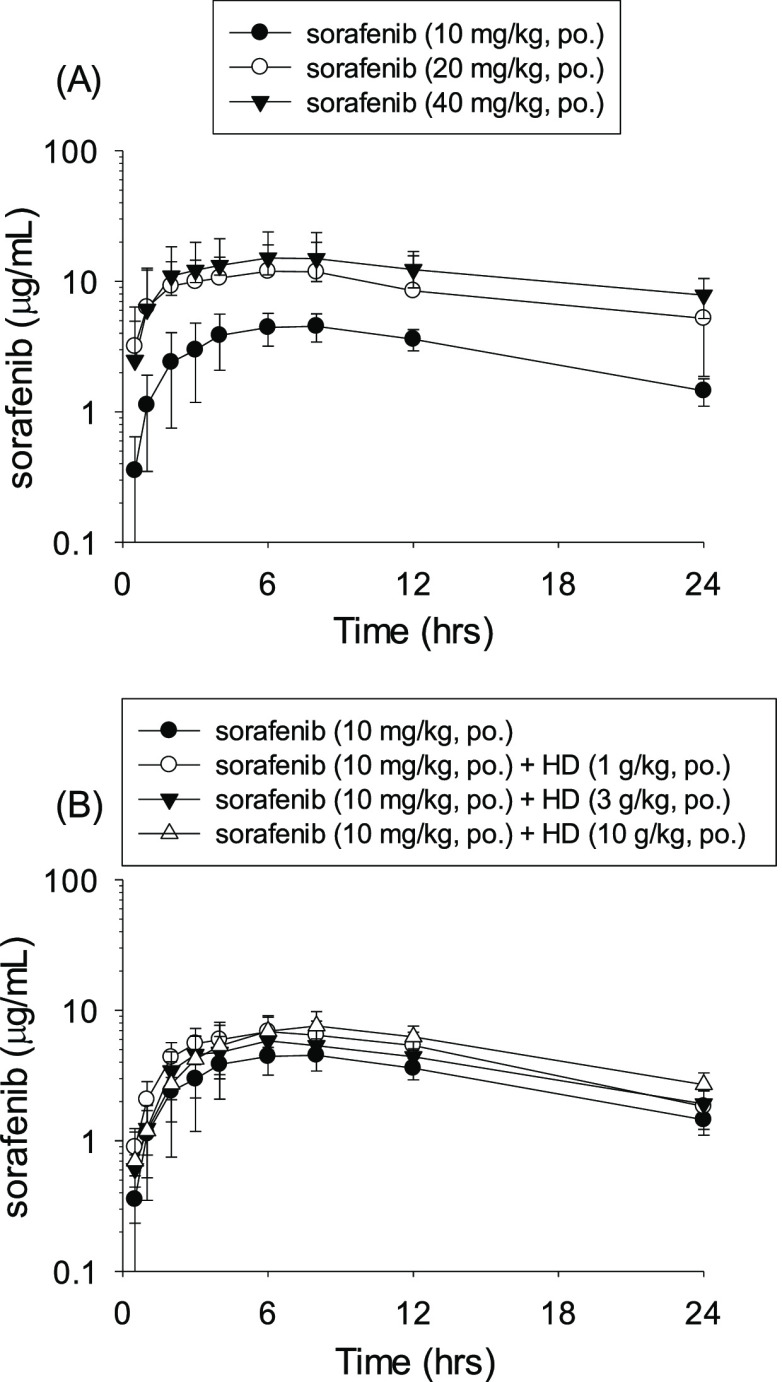

The freely moving experimental rat model used in this study was based on the studies of Thrivikraman et al. and Park et al.26,27 Initially, a preliminary pharmacokinetic study was conducted by evaluating the concentration versus time curves after a single oral dose of sorafenib (10, 20, and 40 mg/kg, p.o.). The pharmacokinetic experimental results showed that the time to drug concentration curve had a dose-dependent property of 10–40 mg/kg in rat plasma (Figure 2A). The pharmacokinetic data in rat plasma after oral administration of different doses of sorafenib are shown in Table 1. The areas under the curve (AUCs) for groups A1, A2, and A3 were 5560 ± 1392, 16,356 ± 7260, and 29,154 ± 10,620 min μg/mL, respectively. The maximal plasma concentration levels (Cmax) values of groups A1, A2, and A3 were 4.73 ± 1.23, 13.79 ± 2.06, and 16.09 ± 3.91 μg/mL, respectively. The t1/2 for groups A1, A2, and A3 were 585 ± 82, 710 ± 137, and 1091 ± 227 min, respectively. The pharmacokinetic curves demonstrated that sorafenib showed dose-dependent pharmacokinetic properties (Figure 2A). The daily dose of sorafenib used clinically for patients with liver cancer is 400–800 mg/day. In this study, the dose translation from human to animal studies was calculated based on body surface area (BSA).28 Our findings implied that when the doses of sorafenib (10, 20, and 40 mg/kg/day) were administered, the pharmacological properties and time to concentration profiles showed dose dependency within the range of drug administration. This experimental model also confirms that the concentrations of different doses of sorafenib show a stable linear relationship in vivo.

Figure 2.

(A) Time–concentration curve of sorafenib in rat plasma after oral administration at a dose of group A1 (10 mg/kg, p.o., ●), group A2 (20 mg/kg, p.o., ○), and group A3 (40 mg/kg, p.o., ▼). Data expressed as mean ± S.D.; (B) Time–concentration profile of sorafenib in rat plasma after single-dose oral administration (group A1, 10 mg/kg, p.o., ●); pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (1 g/kg, p.o.) for 5 consecutive days, followed by a single dose of sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.) at day 5 (group A4, ○; n = 6); pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (3 g/kg, p.o.) for 5 consecutive days followed by a single dose of sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.) at day 5 (group A5, ▼; n = 6); and pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (10 g/kg, p.o.) for 5 consecutive days followed by a single dose of sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.) at day 5 (group A6, Δ; n = 6). Data are expressed as mean ± S.D.; n = 6. HD: H. diffusa extract.

Table 1. Sorafenib Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Rat Plasma Treated with Different Doses of Sorafenib Alone and Concomitant Treatment with H. diffusa Extract and Sorafeniba.

| group A1 | group A2 | group A3 | group A4 | group A5 | group A6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (min μg/mL) | 5560 ± 1392 | 16,360 ± 7260 | 29,150 ± 10,620 | 7965 ± 2055 | 7271 ± 1371 | 8821 ± 1705 |

| Tmax (min) | 380 ± 90 | 350 ± 144 | 330 ± 151 | 380 ± 90 | 380 ± 49 | 420 ± 66 |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 4.73 ± 1.23 | 13.79 ± 2.06 | 16.09 ± 3.91 | 7.06 ± 2.34 | 5.88 ± 0.61 | 8.54 ± 1.53 |

| t1/2 (min) | 585 ± 82 | 710 ± 137 | 1091 ± 227 | 548 ± 132 | 636 ± 86 | 543 ± 87 |

| CL (mL/min/kg) | 1.92 ± 0.59 | 1.38 ± 0.48 | 1.52 ± 0.54 | 1.32 ± 0.33 | 1.41 ± 0.24 | 1.17 ± 0.21 |

| Vss (mL/kg) | 1602 ± 453 | 1340 ± 315 | 2294 ± 548 | 1052 ± 426 | 1272 ± 77 | 910 ± 208 |

| MRT (min) | 1008 ± 132 | 1114 ± 234 | 1678 ± 371 | 922 ± 166 | 1051 ± 136 | 990 ± 158 |

AUC: area under the time to concentration curve; Tmax: time of maximum concentration; Cmax: maximum concentration; t1/2: half-life; CL: clearance; Vss: apparent volume of distribution at steady state; data are expressed as mean ± S.D. (n = 6). Group A1: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.). Group A2: sorafenib (20 mg/kg, p.o.), Group A3: sorafenib (40 mg/kg, p.o.), Group A4: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.), following pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (1 g/kg, p.o.; for 5 consecutive days). Group A5: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.), following pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (3 g/kg, p.o.; for 5 consecutive days). Group A6: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.), following pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (10 g/kg, p.o.; for 5 consecutive days).

2.3. Pharmacokinetic Interactions of H. diffusa and Sorafenib in Rats

The concentration versus time plot of sorafenib in rats for Part A (groups A1, A4, A5, and A6) is shown in Figure 2B. In group A1, the rats were treated with sorafenib alone (Group A1; sorafenib 10 mg/kg, p.o.). The subsequent pharmacokinetic study revealed that the detectable plasma concentration of sorafenib gradually increased after oral administration, reached Cmax about 3 to 8 h after drug administration and then showed a slowly decreasing trend. The sorafenib concentration of plasma remained at a comparatively high level 24 h after oral administration. For groups A4, A5, and A6, the experimental animals were pretreated with different doses of H. diffusa extract (1, 3, and 10 g/kg/day, p.o., respectively) for 5 consecutive days before a single dose administration of sorafenib orally (10 mg/kg, p.o.). The time to concentration curves showed that pretreatment with various doses of H. diffusa extract did not alter the pharmacokinetic curve of sorafenib in rats (Figure 2B). Further pharmacokinetic studies were performed to evaluate the combined use of different doses of H. diffusa and sorafenib alone (10 mg/kg, p.o.). The AUCs of sorafenib in A1, A4, A5, and A6 groups were 5560 ± 1392, 7965 ± 2055, 7271 ± 1371, and 8821 ± 1705 min μg/mL, respectively. The maximum drug concentration (Cmax) of sorafenib in A1, A4, A5, and A6 groups were 4.72 ± 1.23, 7.06 ± 2.34, 5.88 ± 0.61, and 8.54 ± 1.53 μg/mL, respectively. The hale-lives (t1/2) of sorafenib in A1, A4, A5, and A6 groups were 585 ± 82, 548 ± 132, 636 ± 86, and 543 ± 87 min, respectively. The mean residence times (MRTs) of sorafenib in A1, A4, A5, and A6 groups were 1008 ± 132, 922 ± 166, 1051 ± 136, and 990 ± 158 min, respectively. Comparison of the pharmacokinetic parameters, including AUCs, Cmax, t1/2, MRTs, Tmax, CL, and Vss, showed no significant differences among groups A1, A4, A5, and A6 (Table 1).

Sorafenib is one of the most commonly used target therapeutic agents for advanced liver cancer.28 However, the intolerable side effects and unsatisfactory efficacy of sorafenib has led to the demand for alternative therapeutic options. To improve the therapeutic effect of sorafenib, physicians have tried to combine other treatment modalities or agents with sorafenib to reduce the side effects or enhance its clinical effect.8,9,29−31 Our previous study reported that H. diffusa is frequently used as a traditional herbal medicine by liver cancer patients in Taiwan.32 In this study, we found that the combined use of sorafenib and different doses of H. diffusa extract did not have a significant pharmacokinetic effect. Additionally, the combined use of sorafenib and different doses of H. diffusa extract did not lead to synergistic effects.

2.4. Histopathological Analyses of Sorafenib and H. diffusa Extract

To investigate the hepatic histopathological toxicity of sorafenib and H. diffusa extract, the degree of liver inflammation and morphometry of liver slices were examined. The histopathological result of the control group showed a normal parenchymal architecture, including the central vein hepatic cords system (Figure 3A). However, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining slices of groups B1, B2, B3, and B4 showed the presence of focal and periportal inflammation, congestion of liver tissue, focal hemorrhage, and focal lytic necrosis of hepatocytes after pretreatment with H. diffusa for 5 days before a single dose of sorafenib was orally administered (10 mg/kg, p.o.) (Figure 3B–E). Similarly, this phenomenon was observed in the 2 week pretreatment groups, and the H&E stained slices in these groups were similar to those in the single dose sorafenib administration group (10 mg/kg, p.o.) (Figure 3F–I). Furthermore, the quantitative hepatic activity of sorafenib treated with/without H. diffusa extract was scored by the modified hepatic activity index grading and necroinflammatory score.33 To understand possible herb/drug-induced hepatotoxic effects, histopathological analysis of treatment, including short term groups: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.) pretreated with different doses of H. diffusa extract (1, 3, and 10 g/kg/day) for 5 consecutive days and long term groups: combined use for 2 weeks, was examined. Compared with that of the normal liver tissue, the experimental data demonstrated both short-term and long-term use of sorafenib resulted in higher necroinflammatory scores (mean = 1 vs 3.67 and 3.5). Both short-term and long-term premedication with different doses of H. diffusa before sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.) administered orally resulted in a higher mean necroinflammatory score (mean = 2.83–4.33) than that of the control group (mean = 1). However, the necroinflammatory score measures showed no significant difference between the H. diffusa treatment group and untreated groups, which suggests that a regimen of H. diffusa in a dose range of 1-10 g/kg per day is safe in rats (Table 2). Finally, for long-term treatment concerns, the rat plasma aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT) levels were studied. The rat plasma AST and ALT levels implied that there was no difference statistically between the single or combination-treated groups for 2 weeks (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Histopathological analyses of the rat liver tissue following administration of sorafenib alone or in combination with H. diffusa extract. (A) Group N, Control group; normal rat liver; (B) Group B1, sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.); (C) Group B2, sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.), following pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (1 g/kg/day, p.o., for 5 consecutive days); (D) Group B3, sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.), following pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (3 g/kg/day, p.o., for 5 consecutive days); (E) Group B4, sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.), following pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (10 g/kg/day, p.o., for 5 consecutive days); (F) Group B5, sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.; consecutive 2 weeks); (G) Group B6, sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.; consecutive 2 weeks), following pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (1 g/kg/day, p.o., for consecutive 2 weeks); (H) Group B7, sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.; consecutive 2 weeks), following pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (3 g/kg/day, p.o., for consecutive 2 weeks); and (I) Group B8, sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.; consecutive 2 weeks), following pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (10 g/kg/day, p.o., for consecutive 2 weeks). 1: focal and periportal inflammation; 2: portal inflammation; 3: focal hemorrhage, congestion, and necrosis; 4: focal lytic necrosis of hepatocytes.

Table 2. Quantitative Measurement with Necroinflammatory Scores of Rat Livers Following Administration of Sorafenib Alone and in Combination with H. Diffusa Extracta.

| group

(n = 6 in each group) |

necroinflammatory

score (mean) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| control | N | 1 | 1 |

| short-term group | B1 | 3.67 | 3.83 |

| B2 | 3.8 | ||

| B3 | 4.33 | ||

| B4 | 3.5 | ||

| long-term group | B5 | 3.5 | 3.08 |

| B6 | 3 | ||

| B7 | 3 | ||

| B8 | 2.83 | ||

Group N: Control group; no sorafenib, group B1: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.), Group B2: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.), following pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (1 g/kg/day, p.o.; for 5 consecutive days), group B3: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.), following pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (3 g/kg/day, p.o.; for 5 consecutive days), group B4: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.), following pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (10 g/kg/day, p.o.; for 5 consecutive days), group B5: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.; consecutive 2 weeks), group B6: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.; consecutive 2 weeks), following pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (1 g/kg/day, p.o.; for consecutive 2 weeks). Group B7: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.; consecutive 2 weeks), following pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (3 g/kg/day, p.o.; for consecutive 2 weeks). Group B8: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.; consecutive 2 weeks), following pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (10 g/kg/day, p.o.; for consecutive 2 weeks).

Figure 4.

Rat plasma AST and ALT levels after a single dose of sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.) and pretreatment with H. diffusa formulation (group B2, 1 g/kg, p.o., n = 6; group B3, 3 g/kg, p.o., n = 6; and group B4, 10 g/kg, p.o., n = 6) for 2 weeks, followed by a single dose of sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.). Blood samples were taken at 0, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h after the oral administration of the single sorafenib dose or after 2 weeks of pretreatment regimen of co-administration of sorafenib and H. diffusa formulation.

Regarding the hepatotoxicity of sorafenib, common adverse events occurred in 21.8–34% of sorafenib-treated patients, resulting in an abnormal elevation of AST and ALT and leading to medication withdrawal and treatment failure.34 Complementary and alternative medicine provides available options to decrease the adverse effects of sorafenib. In addition, both in vivo and meta-analysis studies have reported that H. diffusa can inhibit many malignant tumor cells, including liver cancers.18−25 Literature review found that traditional herbal preparations, such as Scutellaria baicalensis, berberine, and H. diffusa, may enhance the efficacy of sorafenib or reduce the adverse drug reactions of cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.32,34−36 The results of our histopathological studies demonstrated that the simultaneous administration of sorafenib and H. diffusa extract has no significant hepatotoxicity according to the modified hepatic activity index grading and necroinflammatory score and hepatic histopathological observations.

3. Conclusions

The concurrent use of sorafenib and H. diffusa has a high possibility of being prescribed for liver cancer patients in Taiwan. The major concern regarding combining herbs with sorafenib is the narrow therapeutic range of sorafenib. However, few investigations have addressed this issue in-depth. Here, we investigated this issue from a pharmacokinetic perspective and evaluated the hepatotoxic potential of this treatment combination. Our results confirmed that the combination of different doses of H. diffusa neither interferes with the efficacy of sorafenib nor exacerbates the sorafenib-induced liver toxicity and histopathological damage. Therefore, the combined use of H. diffusa extracts and sorafenib appears to be safe and does not aggravate sorafenib-induced hepatotoxicity or tissue damage at the tested doses; however, this combination strategy did not enhance the efficacy of sorafenib.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Sorafenib (BAY 43-9006) of over 99% purity level was obtained by Bayer Pharmaceutical. (Kaiser-Wilhelm-Allee, Leverkusen, Germany). H. diffusa (production batch number, BP6005270) was purchased from Sheng-Chang Pharmaceutical. (Taoyuan, Taiwan). The internal standard (diethylstilbestrol) with a purity higher than 99% was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA). Other liquid chromatography grade reagents, including methanol, acetonitrile, and potassium dihydrogen phosphate monohydrate, were all obtained from E. Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). All reagents used in the HPLC experiment were prepared with triply deionized water (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA).

Sorafenib and diethylstilbestrol were dissolved in methanol and diluted with 50% methanol to the specified concentrations as stock solutions. The calibration and internal standard solution were stored at −20 °C for subsequently analysis. Before drug administration for the animal experiment, the H. diffusa extract was prepared with triply deionized water.

4.2. Animal Experiment and Sample Preparation

Male Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from the National Yang-Ming University Animal Center (Taipei, Taiwan). The rats were housed on a 12-h light/dark light cycle and given ad libitum access to water. The animal experimental project was approved by the Institutional Animal Experimentation Committee of the National Yang-Ming University (IACUC 1060408), Taipei, Taiwan. During the experiment, the anesthesia of the adult rat (6–8 weeks old) was performed with a certain dose of urethane (1 g/kg, i.p.), and anesthesia was maintained throughout the experimental period. After anesthesia, the body temperature of rats was maintained with a heating pad. A longitudinal skin incision along the right neck was made, which exposed the right external jugular vein and major pectoralis muscle. A central vein catheter with a silicon stopper was inserted into the right internal jugular vein and advanced into the sinus vein. The free end of the catheter was transfixed by sutures to the postauricular skin of the neck. A heparin lock was inserted into the free tip of the catheter. After that, the catheter was filled with 200 units/mL heparinized normal saline solution.26,27 After adding a 50 μL aliquot of the plasma sample to 150 μL of the internal standard solution, protein precipitation was performed by vortexing and mixing with sonication for 10 s. All samples were centrifuged at 13,000g and 37 °C for 10 min. The sample supernatant was put into the HPLC systems for analysis.

4.3. Measuring the Sorafenib Levels with HPLC Analysis in Rat Plasma

The rat plasma was analyzed with a Shimadzu HPLC system (Model SIL-20AC), which was a combination of a liquid chromatographic pump (Model LC-20AT), a chromatographic autosampler (Model SIL-20AC), and a photo diode array detector (Model SPD-M20A, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The rat plasma analytes were separated by a C18 column (50 mm × 2.1 mm i.d.; particle size 1.7 μm, Waters Acquity, Dublin, Ireland) and a guard column. To ensure accurate chromatographic analysis of sorafenib and the internal standard, the configured sorafenib stoke solution was diluted to different concentrations of the working solution for the experiment. The mobile phase was composed of 10 mM KH2PO4 (pH 3.0 adjusted by phosphoric acid) and acetonitrile (55:45, v/v). The total running time was 10 min, and the flow rate was 0.2 mL/min. The pump pressure was controlled under 8535 psi. The temperature of the autosampler and column oven were maintained at 10 and 25 °C, respectively. The sample injection volume was set at 5 μL, and the peak integration of the UV wavelength was set at 265 nm.

4.4. Study Design

The whole experiment was divided into two parts: (A) pharmacokinetic interaction between H. diffusa extract and sorafenib and (B) pharmacodynamic assessment of the hepatotoxicity and histopathological interaction after combination treatment of H. diffusa extract and sorafenib.

4.4.1. Part A: Pharmacokinetic Interaction between H. diffusa Extract and Sorafenib

Rats undergoing jugular vein catheterization surgery were randomly divided into the following experimental groups. Blood samples (0.15 mL) were taken from the jugular vein catheter at a time interval of 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h after the following dosage regimens:

Group A1: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.).

Group A2: sorafenib (20 mg/kg, p.o.).

Group A3: sorafenib (40 mg/kg, p.o.).

Group A4: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.) and pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (1 g/kg/day, p.o., for 5 consecutive days).

Group A5: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.) and pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (3 g/kg/day, p.o., for 5 consecutive days).

Group A6: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.) and pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (10 g/kg/day, p.o., for 5 consecutive days).

4.4.2. Part B: Hepatotoxicity and Histopathological Interaction of H. diffusa Extract and Sorafenib

Freely moving rats were randomly divided into Groups N and B1–B8 for histopathological studies, with six animals in each group. For the study with groups B1–B4, a single dose of sorafenib (10 mg/kg) was administered orally or after pretreatment with H. diffusa extract for 5 consecutive days at doses of 1, 3, and 10 g/kg. For the study with the experimental groups B5–B8, a single dose of sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.) was administered for 2 consecutive weeks or after long-term pretreatment with H. diffusa extract at doses of 1, 3, and 10 g/kg for 2 consecutive weeks.

Group N, normal rats, no medication given.

Short-term study:

Group B1: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.).

Group B2: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.) and pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (1 g/kg/day, p.o., for 5 consecutive days).

Group B3: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.) and pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (3 g/kg/day, p.o., for 5 consecutive days).

Group B4: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.) and pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (10 g/kg/day, p.o., for 5 consecutive days).

Long-Term Study:

Group B5: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.; consecutive 2 weeks).

Group B6: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.; consecutive 2 weeks) and pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (1 g/kg/day, p.o., for consecutive 2 weeks).

Group B7: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.; consecutive 2 weeks) and pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (3 g/kg/day, p.o., for consecutive 2 weeks).

Group B8: sorafenib (10 mg/kg, p.o.; consecutive 2 weeks) and pretreatment with H. diffusa extract (10 g/kg/day, p.o., for consecutive 2 weeks).

The middle part of the rat liver tissues was obtained and subsequently embedded in paraffin by washing, fixing, dehydration, removal, and infiltration. Before histopathological analysis, each group of embedded liver tissue sections was prepared by H&E staining. Rat liver tissue slices that were treated with single and consecutive doses of sorafenib following different doses of H. diffusa extract were used to verify histopathological alterations. The histopathological observation was managed by pathologists of the Department of Pathology of Taipei City Hospital, Ren-Ai branch (Taipei, Taiwan).

4.5. Statistics

The pharmacokinetic parameters were measured by using the WinNonlin system (Version 1.0 program, Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA). Significant differences were calculated by using Student’s t-test. Significant differences were calculated by using Student’s t-test. Experimental data and pharmacokinetic parameters are expressed as means ± standard deviation. The experimental data were used to plot the pharmacokinetic and time to concentration curves.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the research funding support from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (MOST 109-2113-M-010-007) and the Taipei City Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan (TCH 10701-62-044).

Author Contributions

C.-T.T and Y.-Y.C. conducted the experiments, performed the data analysis, and prepared the manuscript. The experimental design, paper editing, and funding security were carried out by T.-H.T.

This research was partly supported by research grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (MOST 109-2113-M-010-007) and the Taipei City Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan (TCH 10701-62-044).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Rawla P.; Sunkara T.; Muralidharan P.; Raj J. P. Update in global trends and aetiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Contemp. Oncol. 2018, 22, 141–150. 10.5114/wo.2018.78941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitisin K.; Packiam V.; Steel J.; Humar A.; Gamblin T. C.; Geller D. A.; Marsh J. W.; Tsung A. Presentation and outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma patients at a western centre. HPB 2011, 13, 712–722. 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crissien A. M.; Frenette C. Current management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 10, 153–161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza A.; Sood G. K. Hepatocellular carcinoma review: current treatment, and evidence-based medicine. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 4115–4412. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i15.4115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang T. W.; Lim H. K.; Cha D. I. Percutaneous ablation for perivascular hepatocellular carcinoma: Refining the current status based on emerging evidence and future perspectives. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 5331–5337. 10.3748/wjg.v24.i47.5331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda T.; Ogasawara S.; Chiba T.; Haga Y.; Omata M.; Yokosuka O. Current management of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Hepatol. 2015, 7, 1913–1920. 10.4254/wjh.v7.i15.1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L.; Cao Y.; Chen C.; Zhang X.; McNabola A.; Wilkie D.; Wilhelm S.; Lynch M.; Carter C. Sorafenib blocks the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, inhibits tumor angiogenesis, and induces tumor cell apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma model PLC/PRF/5. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 11851–11858. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-06-1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C.; Xu R.; Li X.-X.; Zhou Y.-F.; Xu X.-Y.; Yang Y.; Wang H.-Y.; Zheng X. F. S. Sorafenib and Carfilzomib Synergistically Inhibit the Proliferation, Survival, and Metastasis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 2610–2621. 10.1158/1535-7163.mct-17-0541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.; Wu M.; Yang T. The synergistic effect of sorafenib and TNF-α inhibitor on hepatocellular carcinoma. EBioMedicine 2019, 40, 11–12. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Liu Y.; Meng L.; Ji B.; Yang D. Synergistic Antitumor Effect of Sorafenib in Combination with ATM Inhibitor in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 14, 523–529. 10.7150/ijms.19033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessel K. A.; Lettner S.; Kessel C.; Bier H.; Biedermann T.; Friess H.; Herrschbach P.; Gschwend J. E.; Meyer B.; Peschel C.; Schmid R.; et al. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) as Part of the Oncological Treatment: Survey about Patients’ Attitude towards CAM in a University-Based Oncology Center in Germany. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0165801 10.1371/journal.pone.0165801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berretta M.; Pepa C. D.; Tralongo P.; Fulvi A.; Martellotta F.; Lleshi A.; Nasti G.; Fisichella R.; Romano C.; De Divitiis C.; et al. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) in cancer patients: An Italian multicenter survey. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 24401–24414. 10.18632/oncotarget.14224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.-t.; Meng Y.-b.; Zhai X.-f.; Cheng B.-b.; Yu S.-s.; Yao M.; Yin H.-x.; Wan X.-y.; Yang Y.-k.; Liu H.; et al. Comparable effects of Jiedu Granule, a compound Chinese herbal medicine, and sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective multicenter cohort study. J. Integr. Med. 2020, 18, 319–325. 10.1016/j.joim.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T. G.; Xiong S. Q.; Yan Y.; Zhu H.; Yi C. Use of chinese herb medicine in cancer patients: a survey in southwestern china. Evidence-Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 769042. 10.1155/2012/769042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristoffersen A. E.; Stub T.; Broderstad A. R.; Hansen A. H. Use of traditional and complementary medicine among Norwegian cancer patients in the seventh survey of the Tromso study. BMC Complementary Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 341. 10.1186/s12906-019-2762-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting C. T.; Kuo C. J.; Hu H. Y.; Lee Y. L.; Tsai T. H. Prescription frequency and patterns of Chinese herbal medicine for liver cancer patients in Taiwan: a cross-sectional analysis of the National Health Insurance Research Database. BMC Complementary Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 118. 10.1186/s12906-017-1628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunwoo Y.-Y.; Lee J.-H.; Jung H. Y.; Jung Y. J.; Park M. S.; Chung Y. A.; Maeng L. S.; Han Y. M.; Shin H. S.; Lee J.; et al. Oldenlandia diffusa Promotes Antiproliferative and Apoptotic Effects in a Rat Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Liver Cirrhosis. Evidence-Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 501508. 10.1155/2015/501508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R.; He J.; Tong X.; Tang L.; Liu M. The Hedyotis diffusa Willd. (Rubiaceae): A Review on Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, Quality Control and Pharmacokinetics. Molecules 2016, 21, 710. 10.3390/molecules21060710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T.-W.; Choi H.; Lee J.-M.; Ha S.-H.; Kwak C.-H.; Abekura F.; Park J.-Y.; Chang Y.-C.; Ha K.-T.; Cho S.-H.; et al. Oldenlandia diffusa suppresses metastatic potential through inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase-9 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression via p38 and ERK1/2 MAPK pathways and induces apoptosis in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 195, 309–317. 10.1016/j.jep.2016.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Liu M.; Liu M.; Li J. Methylanthraquinone from Hedyotis diffusa WILLD induces Ca2+-mediated apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Toxicol. Vitro 2010, 24, 142–147. 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G.; Wei L.; Feng J.; Lin J.; Peng J. Inhibitory effects of Hedyotis diffusa Willd. on colorectal cancer stem cells. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 11, 3875–3881. 10.3892/ol.2016.4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Q.; Lin J.; Wei L.; Zhang L.; Wang L.; Zhan Y.; Zeng J.; Xu W.; Shen A.; Hong Z.; Peng J. Hedyotis diffusa Willd inhibits colorectal cancer growth in vivo via inhibition of STAT3 signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 6117–6128. 10.3390/ijms13056117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L.; Cheng K.; Xie Z.; Chen C.; Chen L.; Huang Y.; Liang Z. Purification and characterization a polysaccharide from Hedyotis diffusa and its apoptosis inducing activity toward human lung cancer cell line A549. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 122, 64–71. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.10.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X.; Li Y.; Jiang M.; Zhu J.; Zheng C.; Chen X.; Zhou J.; Li Y.; Xiao W.; Wang Y. Systems pharmacology uncover the mechanism of anti-non-small cell lung cancer for Hedyotis diffusa Willd. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 969–984. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L. T.; Sheung Y.; Guo W. P.; Rong Z. B.; Cai Z. M. Hedyotis diffusa plus Scutellaria barbata Induce Bladder Cancer Cell Apoptosis by Inhibiting Akt Signaling Pathway through Downregulating miR-155 Expression. Evidence-Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 9174903. 10.1155/2016/9174903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrivikraman K. V.; Huot R. L.; Plotsky P. M. Jugular vein catheterization for repeated blood sampling in the unrestrained conscious rat. Brain Res. Protoc. 2002, 10, 84–94. 10.1016/s1385-299x(02)00185-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park A. Y.; Plotsky P. M.; Pham T. D.; Pacak K.; Wynne B. M.; Wall S. M.; Lazo-Fernandez Y. Blood collection in unstressed, conscious, and freely moving mice through implantation of catheters in the jugular vein: a new simplified protocol. Physiol. Rep. 2018, 6, e13904 10.14814/phy2.13904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng A.-L.; Kang Y.-K.; Chen Z.; Tsao C.-J.; Qin S.; Kim J. S.; Luo R.; Feng J.; Ye S.; Yang T.-S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 25–34. 10.1016/s1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn W.; Paik Y.-H.; Cho J.-Y.; Lim H. Y.; Ahn J. M.; Sinn D. H.; Gwak G.-Y.; Choi M. S.; Lee J. H.; Koh K. C.; et al. Sorafenib therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma with extrahepatic spread: treatment outcome and prognostic factors. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 1112–1121. 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lencioni R.; Llovet J. M.; Han G.; Tak W. Y.; Yang J.; Guglielmi A.; Paik S. W.; Reig M.; Kim D. Y.; Chau G.-Y.; et al. Sorafenib or placebo plus TACE with doxorubicin-eluting beads for intermediate stage HCC: The SPACE trial. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 1090–1098. 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medavaram S.; Zhang Y. Emerging therapies in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 7, 17. 10.1186/s40164-018-0109-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.-Y.; Hsieh C.-H.; Tsai T.-H. Concurrent administration of anticancer chemotherapy drug and herbal medicine on the perspective of pharmacokinetics. J. Food Drug Anal. 2018, 26, S88–S95. 10.1016/j.jfda.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishak K.; Baptista A.; Bianchi L.; Callea F.; De Groote J.; Gudat F.; Denk H.; Desmet V.; Korb G.; MacSween R. N. M.; et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 1995, 22, 696–699. 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimassa L.; Pressiani T.; Merle P. Systemic Treatment Options in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Cancer 2019, 8, 427–446. 10.1159/000499765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsaied O. A.; Sangwan V.; Banerjee S.; Krosch T. C.; Chugh R.; Saluja A.; Vickers S. M.; Jensen E. H. Sorafenib and triptolide as combination therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery 2014, 156, 270–279. 10.1016/j.surg.2014.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H.; Wang Y.; He X.; Zhang Z.; Yin Q.; Chen Y.; Yu H.; Huang Y.; Chen L.; Xu M.; et al. Codelivery of sorafenib and curcumin by directed self-assembled nanoparticles enhances therapeutic effect on hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Pharm. 2015, 12, 922–931. 10.1021/mp500755j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]