Abstract

Hydrated lime is widely used as a mineral filler to improve several properties of bituminous materials such as reducing the susceptibility of the composite to moisture-induced damage. Although experimental evidence supports the efficacy of using hydrated lime as a mineral filler, the molecular scale mechanism of reactivity of hydrated lime within the bitumen to reduce moisture damage is not understood. This is important when considering the durability of structural applications of bituminous materials such as asphalt concrete pavements subjected to both environmental and loading extremes. In this study, the interaction between hydrated lime and the key molecular building blocks of bitumen is modeled using density functional theory and compared against analogues of other common fillers such as calcite and quartz. Free energies of dissociation (ΔGdissoc) are calculated, and the nature of the bonds is characterized with contour maps of the Laplacian of the electron density. Hydrated lime is capable of reacting with specific functional groups in bitumen moieties and developing strong, water-resistant complexes. Among the functional groups investigated, carboxylic acids are the preferential reaction sites between hydrated lime and the bitumen moieties. Values as high as ΔGdissoc = +49.42 kcal/mol are reported for hydrated lime with water as the surrounding solvent. In contrast, analogues of calcite (ΔGdissoc = +15.84 kcal/mol) and quartz (ΔGdissoc = +4.76 kcal/mol) are unable to chemically react as strongly as hydrated lime in the presence of water. Contour maps of the Laplacian of the electron density indicate that the bonds between hydrated lime and model asphalt moieties are of an ionic nature. The atomistic modeling results correlate with thermodynamic calculations derived from experimental constants and are consistent with infrared spectrometric data.

Introduction

Mineral fillers are the principal constituents of the mastic phase in asphalt mixtures. The mastic phase controls the bitumen-aggregate performance by providing increased adhesion and traction against slippage of one aggregate against the other and should be resistant to the formation and propagation of microcracks leading to fatigue of the entire asphalt concrete pavement layer. The mastic phase is the fine organo-mineral interstitial matrix that acts as a barrier against water intrusion through the large aggregate skeleton of the asphalt mixture. For this reason, a strong physical and chemical interaction between the bitumen and the mineral filler is desired to minimize moisture damage. Mineral fillers are designated as either inert (nonreactive) or active (reactive). Hydrated lime has been shown experimentally to be an active mineral filler.1−3 Evidence suggests that hydrated lime reacts with bitumen molecular constituents, but the reaction mechanism is unclear. Consequently, this research addresses the following core objectives:

Develop an atomistic modeling methodology capable of distinguishing between chemical (reactive) interactions and physical (nonreactive) interactions.

Provide mechanistic evidence of the reactivity of hydrated lime as a filler in asphalts and quantitatively compare the strength of the interaction of hydrated lime against other potentially active fillers (e.g., calcite) or likely inert fillers (e.g., quartz).

Compare computational results with experimental data supporting the efficacy of lime used as a mineral filler in bituminous mixtures.

Precedents on the Effects of Hydrated Lime in Bituminous Materials

The study of the effects of hydrated lime in asphalt mixtures remains an active subject of scientific research.4−9 Experimental investigations have been conducted since years as early as 1987,3 and some modeling studies have been reported more recently.4,8,10 Studies ranging from durability aspects (e.g., moisture damage and4,10−13 aging3,7) to performance aspects (e.g., permanent deformation,2 fracture, and fatigue6−9) have demonstrated that hydrated lime is a beneficial mineral filler in asphalt mixtures. However, the chemical reactivity of the interaction between hydrated lime and bitumen has not been fully verified or quantified mechanistically with computational chemistry calculations at the atomistic scale.

Detrimental Role of Carboxylic Acids in Bitumen

Carboxylic acids occur naturally in bitumen, and their presence is problematic to the long-term durability of the asphalt mixture material used in pavement structures. Water is capable of disrupting the interaction between the carboxylic group in bitumen moieties and several types of mineral aggregate surfaces.14 A typical example is the interaction between Si–OH groups in siliceous aggregates and a carboxylic acid moiety in bitumen, where the hydrogen bond can be broken easily by water. Experimental evidence leads to the inference that when hydrated lime is added to bitumen, it is able to react selectively with the carboxylic acids forming complexes defined by the formula Ca–(RCOO)2 that have been deemed as insoluble organic salts.3 Once the majority of the carboxylic acids have been complexed by the calcium ions from the hydrated lime, stronger and more durable bonds can be achieved between the aggregate surface with these salts and other asphalt moieties. The following sections focus on an atomistic modeling assessment of the interactions between the key bitumen model moieties (carboxylic acids and heterocycles) with three different mineral fillers (hydrated lime, calcite, and quartz). A thorough description of the rationale for the proposed models of the species in this study can be found at the end under “Material Models and Their Constituents”.

Research Methodology

The methodology we implemented is based upon density functional theory (DFT), providing qualitative and quantitative inferences of the chemical reaction mechanisms between the proposed molecular models of bitumen and mineral systems. The occurrence of complexation and strength of the bonds formed when mineral filler complexes with organic moieties is evaluated based upon the free energy of dissociation (ΔGdissoc). Two surrounding solvent conditions are evaluated: water to represent severe moisture intrusion and n-dodecane to represent bitumen in a pure nonaqueous state. The proposed mechanisms are tested by correlating the atomistic simulation results with thermodynamic calculations based on published experimentally determined constants. Additionally, infrared spectrometric data support the occurrence of complexation between hydrated lime and carboxylic acids present in bitumen. Finally, we investigate the character of the bonds (ionic or covalent) using DFT calculations of the Laplacian of the electron density. The research program algorithm is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram illustrating the research program algorithm.

Theoretical Foundations

DFT is a quantum mechanical technique formulated to calculate the atomic properties and molecular reactions based upon the definition of the electron density function ρ(r).15 The electron density function ρ(r) is defined as the probability that an electron in an individual wave function ψi(r) is located at the position vector r with spatial coordinates x, y, and z. The previous statement is the single most important simplification of DFT as a quantum mechanical technique, specifically that ρ(r) is a function of only three spatial coordinates as opposed to the full wave function solution of Schrödinger’s equation. Mathematically, ρ(r) is formulated as in eq 1

| 1 |

Having defined and formulated the electron density function as the prime theoretical foundation, according to DFT, the energy of a given system is formulated as a function of the electron density function. Hence, the name “DFT”, where a functional is defined as a function whose argument is another function. The ground state energy of a system is formulated as in eq 2

| 2 |

The energy functional expression is divided into noninteracting electron terms and interacting electron correction terms.16 These are formulated as shown in eq 3

| 3 |

where,

Tni[ρ(r)] = noninteracting electron kinetic energy

Vne[ρ(r)] = nuclear–electron interaction potential

Vee[ρ(r)] = classical electron–electron repulsion potential

ΔT[ρ(r)] = kinetic correction term for interactive nature of electrons

ΔVee[ρ(r)] = potential correction term for nonclassical electron interactions

The first three terms formulated in eq 3 are “known” and can be solved analytically. However, the last two terms pose a challenge as they are “unknown” and can only be approximated. So much more complex is their determination that their sum was attributed a special denomination: the exchange correlation functional EXC, formulated as EXC = ΔT[ρ(r)]+ΔVee[ρ(r)]. Many approximation functionals have been developed, however, as it is not the goal of this work to address the theoretical framework of DFT in its entirety, further details can be found elsewhere.15−17

Computational Overview

The PBE (Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof) functional was used in this study.18,19 Because the chemical surrogates devised for this investigation were simplified to be discrete molecular systems instead of periodic systems, the use of plane waves (spatially extended functions) to define the basis functions was not necessary. Instead, Gaussian functions (spatially localized functions) define the basis functions used in the basis set expression. Following this criterion, the 6-311++G(3d,3p) triple-ζ Pople20 basis set with polarization and diffuse functions was chosen.

Another condition of the discrete molecular system implemented is the use of an implicit solvation model. Discrete molecular structures are surrounded by or isolated in an infinite continuum representing the selected solvent. We used the SMD21 solvation model to define a solvation cavity for the species that were defined explicitly, which incorporates the solvation energy component into the calculation of the total energy of the system. In all cases, we simulated two solvents. Water was an obvious choice to represent the behavior of the species or complexes surrounded by a water continuum as would occur during a severe moisture intrusion; and, because the pure medium in which these complexes form is bitumen, we chose n-dodecane as an aliphatic nonpolar matrix representative of the paraffinic dispersant solvent-like phase (oils) of a bituminous mixture.

Determination of the Bonding Strength

A vast array of experimental methods exists to determine the strength of materials at the macroscale, microscale, and even at the nanoscale. The most common (and usually feasible) modeling approach is through the usage of continuum models. However, when dealing with chemical phenomena, all these methods tend to fall short in providing direct causative explanation of the strength gain mechanism. Through the application of DFT using the Gaussian 16 modeling suite,22,23 we established a prediction methodology to energetically examine the stability and strength of a given molecular complexation system; in this case, the central system of interest is the complexation between the hydrated lime and bitumen moieties.

Calculation of Dissociation Energies

Geometry optimization and frequency calculations were conducted, and the final result is a set of thermochemical parameters under a section denominated “Thermochemistry” provided by the accompanying graphical interface software GaussView 6. Within those, the parameter of interest is the total energy of the system, “Sum of electronic and thermal free energies”. With this value, whether or not the dissociation is favored can be determined based on the sign of ΔG and the strength is given by the numeric value of ΔG. We modeled complex dissociation. Therefore, a positive value of ΔG means that the complex is stable, and a negative value of ΔG indicates that dissociation is favored under the environmental conditions of a chosen solvent. The dissociation energy is calculated then according to eq 4, as the difference between the free energies of the complex (AB) and that of the dissociated components A and B in a defined solvent

| 4 |

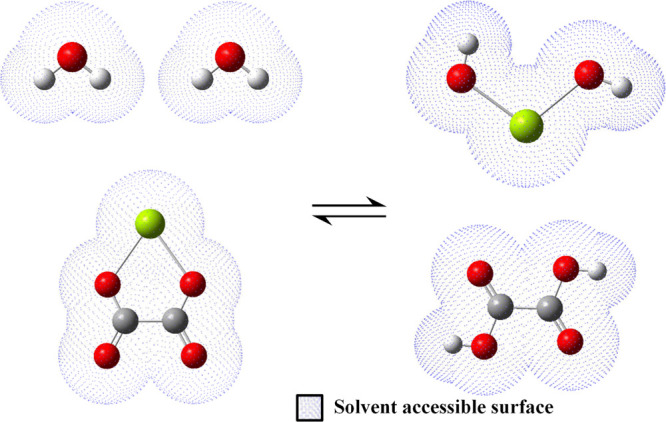

The graphical example of this reaction scenario is shown in Figure 2, where a calcium oxalate complex dissociates into oxalic acid and hydrated lime. On the left side of the scheme, the energetics of the complex and two water molecules are calculated, whereas on the right side, the energies of the dissociated species are obtained.

Figure 2.

Graphical reaction scheme of the calcium oxalate complex dissociation. Atom colors are green (Ca), red (O), gray (C), and white (H).

Analogous to the dissociation scheme presented for hydrated lime and oxalic acid, a dissociation scheme is presented for the reaction between calcium carbonate and oxalic acid in Figure 3. In this case, the balance of energy evaluated is the following: the energetics of the calcium oxalate complex and a carbonic acid molecule on the left side is obtained and compared against the energetics of the dissociated species calcium carbonate and oxalic acid shown on the right side.

Figure 3.

Graphical reaction scheme for the calcium carbonate system. Atom colors are green (Ca), red (O), gray (C), and white (H).

Following this conceptual approach, the energies of dissociation of all the models specified previously were determined in both water and n-dodecane. In addition, the energy of dissociation of the organic moieties representative of bitumen was determined for the case of an isolated calcium ion Ca2+, mimicking the case in which hydrated lime is able to release free calcium ions into each of the two solvents specified above. A testing matrix was constructed which allows the observation of tendencies.

Visualization of Bonding Character

We used the Laplacian of the electron density to assess the ionic or covalent character of the complexes included in this study.24 With the aid of the software GaussView 6, it is possible to generate cross sections along the bonds between atoms containing contour plots of isolines of the Laplacian of the electron density, which indicate the regions in which the change in the gradient of the electron density rises or where it diminishes.

Results and Discussion

Bonding Strength—Dissociation Energies

Table 1 shows the matrix of cases that we simulated, where the resulting value of dissociation energy is indicated for each case. Dissociation energies nearly always had a positive sign for carboxylic acid moieties, meaning that these complexes are stable in both solvents simulated. The lone exception was CaCO3 in water, for which acetate, hexanoate, and dodecanoate were negative. For heterocyclic moieties, the dissociation energies were all negative in aqueous media, meaning that these complexes are not stable and dissociation is favored. A second major trend noticeable from Table 1 is that of the difference in the outcomes for the dissociation energy when comparing water versus n-dodecane. Dissociation energies tend to be higher for all the minerals and Ca2+ when n-dodecane is the solvent. A visual comparison of these trends is shown in Figure 4 (a through d).

Table 1. Matrix with Dissociation Energy Values for the Systems in Studya.

| dissociation energies, kcal/mol | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| potentially reactive systems |

potentially inert systems |

|||||||

| Ca(OH)2 | CaCO3 | Ca2+ | Si2O7H6 | |||||

| aq | naq | aq | naq | aq | naq | aq | naq | |

| ox | 49.42 | 18.30 | 15.84 | 16.14 | 12.93 | 247.87 | 4.76 | 38.81 |

| ac | 31.48 | 38.39 | –2.09 | 36.23 | 5.95 | 237.39 | 2.54 | 21.48 |

| bz | 34.94 | 40.70 | 1.36 | 38.54 | 4.48 | 229.86 | 2.40 | 20.78 |

| hex | 30.74 | 36.98 | –2.84 | 34.82 | 5.19 | 238.62 | 2.39 | 19.34 |

| doc | 28.81 | 34.33 | –4.76 | 32.17 | 3.63 | 240.11 | 1.08 | 21.32 |

| pydn | –9.80 | 4.15 | –11.58 | 6.19 | –6.62 | 11.30 | –5.00 | –0.59 |

| thio | –9.51 | –4.82 | –11.32 | –2.17 | –6.19 | 19.56 | –8.43 | –4.88 |

| pyol | –9.75 | 0.71 | –9.37 | 1.99 | –5.78 | 29.19 | –4.74 | –5.23 |

ox = oxalate, ac = acetate, bz = benzoate, hex = hexanoate, doc = dodecanoate, pydn = pyridine, thio = thiophene, pyol = pyrrole. Solvents: aq = water, naq = n-dodecane.

Figure 4.

Dissociation energy bar graphs for (a) calcium hydroxide, (b) calcium carbonate, (c) Ca2+ ions, and (d) pyrosilicic acid.

The last two important trends are presented in Figure 5. Heterocyclic moieties have strongly positive energies of dissociation for Ca2+ ions with n-dodecane as the solvent, Figure 5a. Thus, when calcium ions are released in bitumen, they will interact strongly with heterocycles, but with the introduction of water, these complexes will become unstable.

Figure 5.

Dissociation energy bar graphs for (a) heterocycles in n-dodecane and (b) carboxylic acids and three minerals in water.

The dissociation energies of carboxylic acid complexes with hydrated lime are much higher than those for calcite and quartz in water as the solvent, Figure 5b.

Bonding Character

The bonding character (ionic vs covalent) was assessed as indicated in the methodology section with cross sections along the bonds between the atoms containing contour isolines of the Laplacian of the electron density.

Figure 6 shows such a contour map for the calcium oxalate complex. The isolines with negative values for the Laplacian (purple) are continuous along the covalent bonds such as that between carbon and oxygen (C–O) and carbon–carbon (C–C). In contrast, the bonds between calcium and oxygen (Ca–O) show a discontinuity with depletion of the gradient of the electron density along the bond (brown isolines), meaning that the bonds are of an ionic character, where the electrons are not being shared across the two atoms. As a comparison, the bonds between sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl) are shown in Figure 7, which is a typical example of an ionic bond.

Figure 6.

Contour map of the Laplacian of the electron density for the calcium oxalate complex.

Figure 7.

Contour map of the Laplacian of the electron density for the sodium chloride ionic bond.

Numerical Assessment Using Thermodynamic Calculations

Free energies calculated from thermodynamic data could be used as a benchmark for free energies determined by the DFT model. For reactions in aqueous media analyzed by DFT, equilibrium constants were either obtained directly from geochemical databases or calculated from thermodynamic compilations. Thermodynamic data were available only for reactions of lime and calcite with acetic acid, oxalic acid, and benzoic acid. The relevant reactions and the source of the data are given in Table 2.

Table 2. Reactions, log K° Values, and Sources of the Thermodynamic Data Used in This Studyb.

| reaction # | reaction | log K° | source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ca2++2H2O⇌Ca(OH)20+2H+ | –27.99 | Lindsay (1979)25 |

| 2 | Ca2++H2CO30⇌CaCO30+2H+ | –13.55 | Lindsay (1979)25 |

| 3 | OAc–+H+⇌HOAc | 4.76 | MINTEQa26 |

| 4 | Ca(OAc)20⇌Ca2++2OAc– | –0.037 | Parker et al. (1971)27 |

| 5 | Oxal2–+2H+⇌H2(Oxal)0 | 5.52 | MINTEQa26 |

| 6 | Ca(Oxal)0⇌Ca2++Oxal2– | –3.19 | MINTEQa26 |

| 7 | Benz–+2H+⇌H(Benz) | 4.20 | MINTEQa26 |

| 8 | Ca(Benz)20⇌Ca2++2(Benz−) | 0.17 | Parker et al. (1971)27 |

Visual MINTEQ, 2020.

OAc = acetate, Oxal = oxalate, Benz = benzoate.

For a given reaction, log K° can be readily converted to the Gibbs free energy as in eq 5

| 5 |

Several reactions needed to be combined to determine the desired free energies using Ca(OAc)2(aq) as an example illustrated in Table 3. The log K° for this reaction is then converted to ΔG° by substituting in eq 5

| 6 |

Table 3. Example Derivation of Relevant Equilibrium Reactions and Constants.

| reaction # | reaction | log K° |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ca2++2H2O⇌Ca(OH)20+2H+ | –27.99 |

| 3 | OAc–+H+⇌HOAc | 4.76 |

| 4 | Ca(OAc)20⇌Ca2++2OAc– | –0.037 |

| Net | Ca(OAc)20+2H2O⇌2HOAc + Ca(OH)20 | –18.51 |

This approach was taken for the six reactions shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Gibbs Free Energies of Reaction as Determined by the DFT Model and Thermodynamic Calculations.

| ΔG° (DFT) | ΔG° (thermo) | |

|---|---|---|

| reaction | kcal/mol | |

| Ca(OAc)20+2H2O⇌Ca(OH)20+2HOAc | 31.48 | 25.25 |

| Ca(Oxal)0+2H2O⇌Ca(OH)20 + H2Oxal | 49.42 | 35.01 |

| Ca(Benz)20+2H2O⇌Ca(OH)20+2H(Benz) | 34.94 | 26.48 |

| Ca(OAc)20+2H2CO30⇌CaCO30+2HOAc | –2.09 | 5.56 |

| Ca(Oxal)0+2H2CO30⇌CaCO30 + H2Oxal | 15.84 | 15.31 |

| Ca(Benz)20+2H2CO30⇌CaCO30+2H(Benz) | 1.36 | 7.01 |

As illustrated in Figure 8, the relationship between the Gibbs free energies computed by the two methods is statistically significant (R2 = 0.999, P< 0.05), but the y-intercept of the model is not zero and the slope is not 1. Many reasons for this are possible including, for example, ideal conditions assumed in the thermodynamic calculations but uncertain in the DFT model. However, the strength of the correlation indicates that the two approaches are in agreement.

Figure 8.

Correlation between DFT results for ΔG and thermodynamic data calculations.

Consistency with Experimental Adsorption Data

One of the principal goals of this modeling study was to compare experimental data to DFT projections concerning the reactive nature of hydrated lime when used as a mineral filler in asphalt mixtures. To accomplish this, we used data by Petersen3 that demonstrated the selectivity of hydrated lime for the reaction with carboxylic acids present in bitumen. The results presented in the quantum modeling and thermodynamic calculation sections show consistency with such experimental data, in which concentration values were obtained using a quantitative differential infrared spectrometric technique developed by Petersen.28,29 The adsorption data shown in Table 5 reports the concentrations in mol/L of strongly adsorbed functional groups for both high calcium lime (typically 72–74% CaO) and dolomitic lime (typically 46–48% CaO and 33–34% MgO). The major trend is evident, favoring the adsorption of almost only carboxylic acid groups present in the asphalt mixtures investigated.

Table 5. Analytical Adsorption Data for Hydrated Lime and Bitumen Functional Groups by Petersen3a.

| high calcium

lime |

dolomitic lime |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| strongly adsorbed | not adsorbed | strongly adsorbed | not adsorbed | |

| percent of total asphalt (%) | 5.64 | 94.36 | 4.73 | 95.27 |

| functional groups, mol/L | ||||

| ketones | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 |

| anhydrides | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| carboxylic acids | 0.83 | 0.003 | 0.80 | 0.005 |

| 2-quinolone | 0.15 | 0.014 | 0.23 | 0.013 |

| sulfoxides | 0 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.03 |

Reprinted with permission from Petersen, J. C.; Plancher, H.; Harnsberger, P. M. Lime Treatment of Asphalt: Final Report. Lime Treatment of Asphalt to Reduce Age Hardening and Improve Flow Properties. Lime Treatment of Asphalt-aggregate Mixtures to Reduce Moisture Damage; Western Research Institute, Laramie, Wyoming, 1987. Copyright 1987. Western Research Institute.

Conclusions

Quantum mechanics modeling is a powerful tool for the evaluation of reactive and nonreactive mineral fillers in bitumen. An advantage of the quantum modeling approach is the ability to surround the model molecular units with solvent continuums of different composition (“implicit solvation”). Two solvents were investigated in this study: water and n-dodecane. Water was used to represent the condition in which water substantially infiltrated the bituminous matrix. The case of n-dodecane represents the pure conditions in which bitumen exists as a dispersion of larger macromolecules in a matrix of paraffinic molecules.

In the case of the bitumen and hydrated lime system investigated, the overall thermodynamics shows calcium complexes preferentially with carboxylic acids, which is consistent with the experimental data obtained by Petersen.3 Calcite was predicted to be unable to react with the majority of the organic molecules of bitumen investigated. When comparing the dissociation energies of the three minerals, substantially greater values of dissociation energy were found for hydrated lime than quartz and calcite.

In the systems in which free Ca2+ ions (i.e., not associated) were evaluated, the dissociation energies for carboxylic acids were lower when water was the solvent than when n-dodecane was the solvent. This shows that the solvation of Ca2+ ions in water is greater than the complexation energy for most of the ligands tested. With the nonpolar medium, n-dodecane, the Ca2+ ions are minimally solvated, allowing a much stronger interaction with the polar carboxylic acids. The same trend was found in the case of heterocycles (pyridine, pyrrole, and thiophene) for which complexation was favored substantially in the case of n-dodecane acting as the solvent.

A qualitative assessment of the nature of the bonds using the Laplacian of the electron density illustrated that the complexation between calcium and oxalate is ionic in nature. This is important for future analyses because a distinction may be drawn between the ionic complexes and the covalent complexes with a correlation to their respective strengths.

A major obstacle in quantum mechanics modeling is the complexity of the approach to evaluate periodic systems. Simplified nonperiodic molecular systems were formulated as surrogates of the more complex minerals. Although this simplification deviates from natural crystalline and amorphous solid surfaces, the bonding environments were adequately mimicked providing quantitative comparisons of the reactive behavior of hydrated lime, calcite, quartz, and free Ca2+ ions.

The results obtained from the quantum modeling methodology proved to be consistent with the experimental data from infrared spectrometry. In addition, statistical significance was found in correlating DFT results with thermodynamic calculations based on experimental constants. Thus, atomistic modeling may be used to evaluate the efficacy of lime as an active filler in bituminous materials as opposed to other rather predominantly inert fillers investigated, with the added ability to extend the analysis for a set of organic species representative of the basic building blocks of asphalt.

Material Models and Their Constituents

“Molecular Building Blocks” of Bitumen

Accurately representing the molecular structure of bitumen is challenging because of the macromolecular nature and diversity of its chemical species.30,31 Key building blocks of bitumen were the interacting components in this study as defined by Robertson.32 These are specific types of molecules (e.g., linear, aliphatic, or aromatic) that comprise bitumen. They possess the specific reaction sites in bitumen moieties based upon the functional groups present in these moieties (e.g., carboxylic acids). The advantage of this approach is the ability to evaluate specific reactions with surrogate molecular systems, which only use the atoms relevant to the definition of the chemical properties of bitumen rather than its physical properties as a whole. Molecular models of the building blocks chosen for this study are shown in Table 6. Although oxalic and acetic acids are not likely to be present in significant quantities in bitumen, they were included because (a) they are composed of a few atoms; and (b) the reactivity of these acids is well known. In particular, oxalic acid is highly reactive with Ca2+ species and can be used as a standard of comparison for the degree of reactivity of other carboxylic acid groups that are associated with larger hydrocarbon moieties.

Table 6. Molecular Species Surrogates of Bitumen Macromolecular Moietiesa.

Atom colors are gray (C), red (O), white (H), blue (N), and yellow (S).

Molecular Representation of Mineral Fillers

Minerals pose a complex system to model at the atomistic scale because of their crystalline nature. The repeated three-dimensional array of atoms in crystals, denominated lattice structure,33 forms “periodic systems” that impose the consideration of periodic boundary conditions in an atomistic model.15 Ultimately, this translates into more complex algorithms, greater computing resources, and longer and costlier computing times. To circumvent these challenging conditions, minerals can be simplified and represented as discrete molecular systems. Examples would include representing hydrated lime as a calcium hydroxide Ca(OH)2 molecule, using pyrosilicic acid Si2O7H6 (the dimer of orthosilicic acid) as a surrogate for the typical quartz bonding environment, and representing calcite as a calcium carbonate bidentate complex CaCO3.

Hydrated Lime as Calcium Hydroxide

The unit cell of hydrated lime shown in Figure 9a was obtained from the American Mineralogist Crystal Structure Database (AMCSD).34 The unit cell can be simplified, as shown in Figure 9b, where all the mirroring boundary atoms are removed showing only the atoms corresponding to the chemical formula Ca(OH)2, resulting in the discrete molecular unit of hydrated lime, as shown in Figure 9c.

Figure 9.

(a) Hydrated lime unit cell, (b) Reduced unit cell, and (c) Hydrated lime discrete molecular unit. Atom colors are green (Ca), red (O), and white (H).

Quartz as Pyrosilicic Acid

Quartz is a tectosilicate, structured as a three-dimensional framework of silicon tetrahedra linked by oxygen atoms (SiO4) that is often reduced to the chemical formula (SiO2). Quartz is a stable mineral phase,35 but the repeating tetrahedra that compose the three-dimensional framework can guide the selection of a discrete molecular structure for atomistic modeling. Orthosilicic acid (H4SiO4) is the primary form of Si in solution, but it polymerizes readily to form larger structures and eventually form the solid phase.36 Therefore, the surrogate chosen for quartz is pyrosilicic acid,37 the dimer of orthosilicic acid, the first step in polymerization to form quartz, and the smallest subunit including a shared oxygen between two silica tetrahedra. Figure 10a illustrates the unit cell of a typical quartz crystal,34 and Figure 10b shows the molecular structure of pyrosilicic acid (Si2O7H6) modeled in this study.

Figure 10.

(a) Unit cell of a quartz crystal and (b) molecular structure of pyrosilicic acid. Atom colors are yellow (Si), red (O), and white (H).

Calcite as Calcium Carbonate

The crystalline structure of calcite is more complex than that of hydrated lime or quartz. Several cleavage plains can be identified between the calcium atoms and the carbonate anions in the lattice structure of the calcite unit cell,33,34 as shown in Figure 11a. For this reason, we propose a simple model of calcite consisting of a calcium atom interacting with a carbonate anion in a bidentate complexation mode, as shown in Figure 11b.

Figure 11.

(a) Calcite unit cell and (b) calcium carbonate complex. Atom colors are green (Ca), red (O), and gray (C).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the provision of supercomputing facilities by the High-Performance Research Computing (HPRC) and the software resources made available by the Laboratory of Molecular Simulation (LMS) of the Chemistry Department of Texas A&M University.

The authors would like to acknowledge the Zachry Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering for the continuous financial support toward the development of the research presented in this publication.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Little D. N.; Petersen J. C. Unique effects of hydrated lime filler on the performance-related properties of asphalt cements: physical and chemical interactions revisited. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2005, 17, 207–218. 10.1061/(asce)0899-1561(2005)17:2(207). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lesueur D.; Petit J.; Ritter H.-J. The mechanisms of hydrated lime modification of asphalt mixtures: a state-of-the-art review. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2013, 14, 1–16. 10.1080/14680629.2012.743669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen J. C.; Plancher H.; Harnsberger P. M.. Lime Treatment of Asphalt: Final Report. Lime Treatment of Asphalt to Reduce Age Hardening and Improve Flow Properties. Lime Treatment of Asphalt-Aggregate Mixtures to Reduce Moisture Damage; Western Research Institute: Laramie, Wyoming, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Behbahani H.; Hamedi G. H.; Gilani V. N. M. Predictive model of modified asphalt mixtures with nano hydrated lime to increase resistance to moisture and fatigue damages by the use of deicing agents. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 265, 120353. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Xu S.; Tebaldi G.; Romeo E. Role of mineral filler in asphalt mixture. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2020, 1–40. 10.1080/14680629.2020.1826351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das A. K.; Singh D. Evaluation of fatigue performance of asphalt mastics composed of nano hydrated lime filler. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 269, 121322. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamedi G. H.; Ghahremani H.; Saedi D. Investigation the effect of short term aging on thermodynamic parameters and thermal cracking of asphalt mixtures modified with nanomaterials. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2020, 1–28. 10.1080/14680629.2020.1808520. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iwański M. M. Effect of Hydrated Lime on Indirect Tensile Stiffness Modulus of Asphalt Concrete Produced in Half-Warm Mix Technology. Materials 2020, 13, 4731. 10.3390/ma13214731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preti F.; Accardo C.; Gouveia B. C. S.; Romeo E.; Tebaldi G. Influence of high-surface-area hydrated lime on cracking performance of open-graded asphalt mixtures. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2020, 1–27. 10.1080/14680629.2020.1808522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H.; Dai Q.; You Z. Chemo-physical analysis and molecular dynamics (MD) simulation of moisture susceptibility of nano hydrated lime modified asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 101, 536–547. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.10.087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S.-C.; Robertson R. E.; Branthaver J. F.; Claine Petersen J. Impact of Lime Modification of Asphalt and Freeze-Thaw Cycling on the Asphalt-Aggregate Interaction and Moisture Resistance to Moisture Damage. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2005, 17, 711–718. 10.1061/(asce)0899-1561(2005)17:6(711). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.-R.; Lutif J. S.; Bhasin A.; Little D. N. Evaluation of moisture damage mechanisms and effects of hydrated lime in asphalt mixtures through measurements of mixture component properties and performance testing. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2008, 20, 659–667. 10.1061/(asce)0899-1561(2008)20:10(659). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diab A.; You Z.; Hossain Z.; Zaman M. Moisture Susceptibility Evaluation of Nanosize Hydrated Lime-Modified Asphalt-Aggregate Systems Based on Surface Free Energy Concept. Transp. Res. Rec. 2014, 2446, 52–59. 10.3141/2446-06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little D. N.; Allen D. H.; Bhasin A.. Modeling and Design of Flexible Pavements and Materials, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing: Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sholl D.; Steckel J. A.. Density Functional Theory. A Practical Introduction;John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New Jersey, United States, 2009; pp7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer C. J.Essentials of Computational Chemistry: Theories and Models, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd: West Sussex, England, 2004; pp255–256. [Google Scholar]

- Lewars E.Computational Chemistry, Introduction to the Theory and Applications of Molecular and Quantum Mechanics, 2 ed.; Springer Netherlands: Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P.; Burke K.; Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. 10.1103/physrevlett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P.; Burke K.; Ernzerhof M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple [Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996)]. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 1396. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditchfield R.; Hehre W. J.; Pople J. A. Self-Consistent Molecular-Orbital Methods. IX. An Extended Gaussian-Type Basis for Molecular-Orbital Studies of Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1971, 54, 724–728. 10.1063/1.1674902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marenich A. V.; Cramer C. J.; Truhlar D. G. Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foresman J. B.; Frisch A.. Exploring Chemistry with Electronic Structure Methods, 3 ed.; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, United States, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.; Li X.; Caricato M.; Marenich A. V.; Bloino J.; Janesko B. G.; Gomperts R.; Mennucci B.; Hratchian H. P.; Ortiz J. V.; Izmaylov A. F.; Sonnenberg J. L.; Williams; Ding F.; Lipparini F.; Egidi F.; Goings J.; Peng B.; Petrone A.; Henderson T.; Ranasinghe D.; Zakrzewski V. G.; Gao J.; Rega N.; Zheng G.; Liang W.; Hada M.; Ehara M.; Toyota K.; Fukuda R.; Hasegawa J.; Ishida M.; Nakajima T.; Honda Y.; Kitao O.; Nakai H.; Vreven T.; Throssell K.; Montgomery J. A. Jr.; Peralta J. E.; Ogliaro F.; Bearpark M. J.; Heyd J. J.; Brothers E. N.; Kudin K. N.; Staroverov V. N.; Keith T. A.; Kobayashi R.; Normand J.; Raghavachari K.; Rendell A. P.; Burant J. C.; Iyengar S. S.; Tomasi J.; Cossi M.; Millam J. M.; Klene M.; Adamo C.; Cammi R.; Ochterski J. W.; Martin R. L.; Morokuma K.; Farkas O.; Foresman J. B.; Fox D. J.. Gaussian 16, Rev. C.01.; Gaussian, Inc.:Wallingford, CT, 2016.

- Bader R. F. W.Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory; Oxford University Press: New York, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay W. L.Chemical Equilibria in Soils; Wiley-Interscience: New York, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Visual MINTEQ. 2020, https://vminteq.lwr.kth.se/visual-minteq-ver-3-1(last accessed Sept 3, 2020).

- Parker V.; Wagman D.; Evans W.. Selected Values of Chemical Thermodynamic Properties, Natl. Bur. Stand.(US) Tech; Note 270-6, 1971.

- Petersen J. C. Quantitative functional group analysis of asphalts using differential infrared spectrometry and selective chemical reactions--theory and application. Transp. Res. Rec. 1986, 1096. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen J. C.; Plancher H. Quantitative determination of carboxylic acids and their salts and anhydrides in asphalts by selective chemical reactions and differential infrared spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 1981, 53, 786–789. 10.1021/ac00229a010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li D. D.; Greenfield M. L. Chemical compositions of improved model asphalt systems for molecular simulations. Fuel 2014, 115, 347–356. 10.1016/j.fuel.2013.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Greenfield M. L. Analyzing properties of model asphalts using molecular simulation. Energy Fuels 2007, 21, 1712–1716. 10.1021/ef060658j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson R. E.; Branthaver J.; Plancher H.; Duvall J.; Ensley E.; Harnsberger P.; Petersen J.. Chemical properties of asphalts and their relationship to pavement performance.SHRP-A/UWP-91-510; Strategic Highway Research Program;National Research Council: Washington, DC, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nesse W. D.Introduction to Mineralogy, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press, Inc.: New York, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Downs R. T.; Hall-Wallace M. The American Mineralogist crystal structure database. Am. Mineral. 2003, 88, 247–250. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon J. B.; Schulze D. G.. Soil Mineralogy with Environmental Applications; Soil Science Society of America: Wisconsin, United States, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh A. III; Klein G.; Vermeulen T.. Polymerization Kinetics and Equilibria of Silicic Acid in Aqueous Systems; University of California., Deptartment of Engineering: Davis (USA), 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi M.; Matsumoto T.; Yagihashi F.; Yamashita H.; Ohhara T.; Hanashima T.; Nakao A.; Moyoshi T.; Sato K.; Shimada S. Non-aqueous selective synthesis of orthosilicic acid and its oligomers. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–8. 10.1038/s41467-017-00168-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]