Abstract

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) has spread to more than 200 countries worldwide, leading to more than 36 million confirmed cases as of October 10, 2020. As such, several machine learning models that can forecast the outbreak globally have been released. This work presents a review and brief analysis of the most important machine learning forecasting models against COVID-19. The work presented in this study possesses two parts. In the first section, a detailed scientometric analysis presents an influential tool for bibliometric analyses, which were performed on COVID-19 data from the Scopus and Web of Science databases. For the above-mentioned analysis, keywords and subject areas are addressed, while the classification of machine learning forecasting models, criteria evaluation, and comparison of solution approaches are discussed in the second section of the work. The conclusion and discussion are provided as the final sections of this study.

Keywords: Forecasting, Analysis, COVID-19, SIR, SEIR, Time series

Introduction

In December 2019, the Chinese government informed the rest of the world that a novel coronavirus, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Related Coronavirus 2 (COVID-19), was rapidly spreading throughout China, which quickly infiltrated many other countries. The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recognized a seafood market in Wuhan as the center of the outbreak. On January 13, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported a case in Thailand, the first case to be identified outside China. On January 16, Japan confirmed its first case, and on January 20, South Korea reported its first confirmed case. Nowadays, most countries in the world have been affected by this virus.

Putra and Khozin Mu’tamar [1] used the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm to estimate parameters in the Susceptible, Infected, Recovered (SIR) model. The results indicate that the suggested method is precise and has low enough error compared to other analytical methods. Mbuvha and Marwala [2] calibrated the SIR model to South Africa’s reported cases after considering different scenarios of the reproduction number (R0) for reporting infections and healthcare resource estimations. Qi and Xiao [3] proposed that both daily temperature and relative humidity can influence the occurrence of COVID-19 in Hubei and other provinces.

Salgotra and Gandomi [4] developed two COVID-19 prediction models based on genetic programming and applied these models in India. Findings from a study by [4] show that genetic evolutionary programming models have proven to be highly reliable for COVID-19 cases in India.

The rest of paper is organized into the following sections. Sections 2 and 3 present the search method procedure and other reviews, respectively. Section 4 shows the main research fields. Generic illustrations are provided in Sect. 5. Mathematical modeling and criteria evaluation are presented in Sects. 6 and 7. Solution approaches, including autoregressive model, exponential models, deep learning, regression methods, etc., are described in Sect. 8. Section 9 depicts the strengths and weaknesses of the various forecasting models. Finally, the conclusion, discussion of results, and future directions are presented in Sect. 10.

Search method procedure

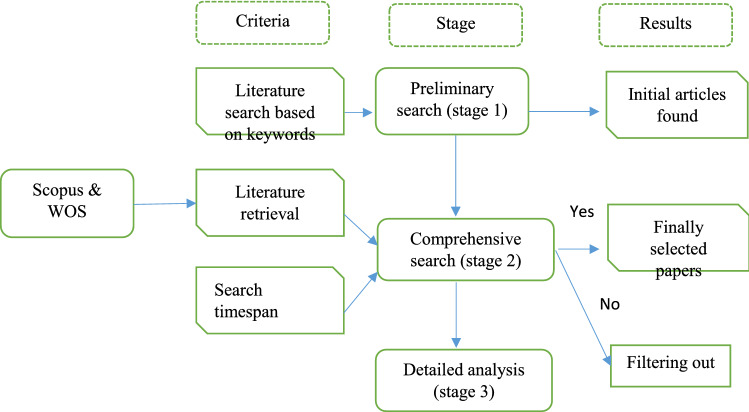

The process used to identify the articles for this study’s review is presented in this section.

Search method

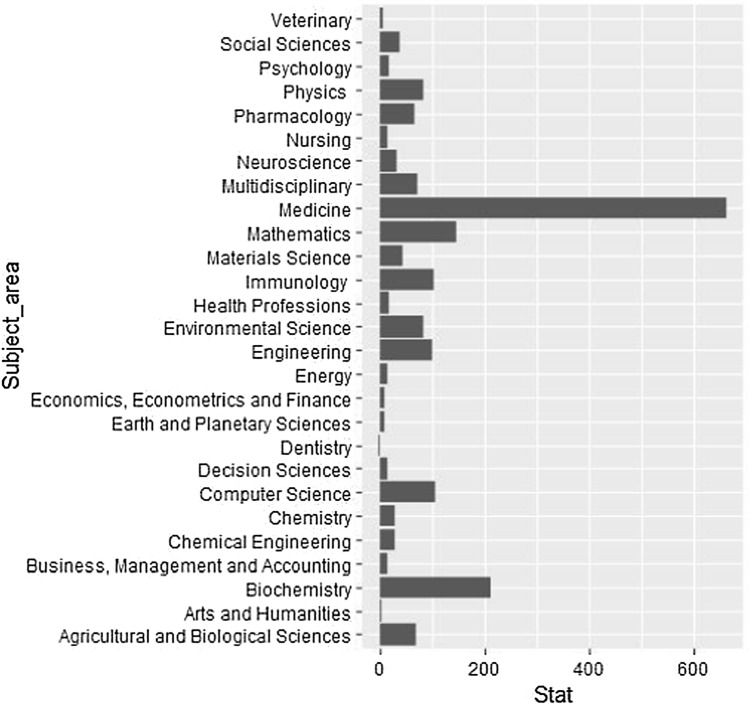

Web of Science (WOS) and Scopus were used to find related publications based on the following keywords: forecasting, prediction, COVID-19, and coronavirus. The classification of the chosen published works based on the subject area is displayed in Fig. 1. Updated articles from the beginning of 2020 to now were filtered from Scopus using the Boolean operator OR, for both topics and titles. We selected 920 technical research articles that contain only algorithmic descriptions, review articles, conference papers, case studies, and provide managerial insights, which were published as of October 10, 2020 (Fig. 2). In addition, this study focuses more on those papers that were indexed by the Web of Science.

Fig. 1.

Classification of scientific papers based on subject area

Fig. 2.

Research methodology used in this paper

Other reviews

Mahalle and Kalamkar [5] categorized forecasting models as mathematical models and machine learning techniques, using WHO and social media communications as datasets. Significant parameters including death count, metrological parameters, quarantine period, medical resources, and mobility were also studied [5].

Naudé [6] provided a review of the contribution of artificial intelligence (AI) against COVID-19. Some fields of AI that have contribution against COVID-19 have been identified as early warnings and alerts, tracking and prediction, data dashboards, diagnosis and prognosis, treatments and cures, and social control [6].

Main research fields

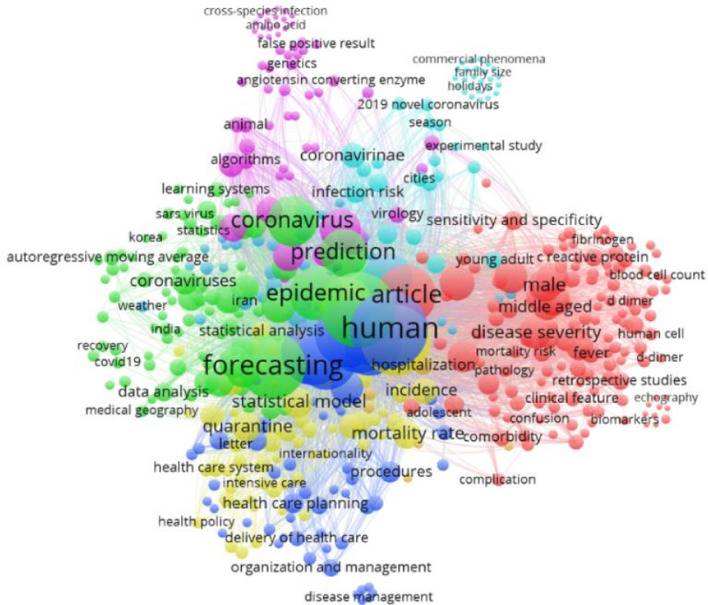

Keywords are critical in identifying the appropriate literature in a research field [7]. As specified by [8]: “keywords represent the core research of a paper.” A keywords network offers a copy of an information area that provides insight into the available subjects and how these topics are related and sorted [9]. Therefore, the VOSviewer 1.6.11 software was applied to provide a keyword co-occurrence network, and bibliographic data were derived from Scopus. Author keywords were used to generate a network of keywords. A sum of 1931 keywords were obtained from the dataset, regarding the full counting. Table 1 presents the parameter settings for keyword visualization.

Table 1.

Parameter settings

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Minimum number of occurrences | 1 |

| Criterion met | 1931 keywords |

The resulting network contains 500 nodes and 4000 links, as shown in Fig. 3, which also presents the main fields for forecasting coronavirus. Stronger links in the network visualization are indicated by thicker lines [10]. It can be seen in Fig. 3 that Coronavirus, prediction, epidemic, human, and forecasting have connection links. Moreover, Fig. 3 presents a network visualization based on keywords, where Coronavirus, prediction, epidemic, human, statistical analysis, quarantine, hospitalization, mortality, and weather are among the top keywords on which researchers focused. In Fig. 3, the cluster is indicated by color, and the bigger circle represents the keyword that is used most.

Fig. 3.

Networks across the links (keywords analysis)

Figure 4 presents the detailed analysis of the sum of works cited and the number of records versus affiliations. The filtered numbers of records and works cited include a minimum of 1 and 18, respectively.

Fig. 4.

A detailed analysis (sum of works cited and number of records vs. Affiliations)

Generic illustrations

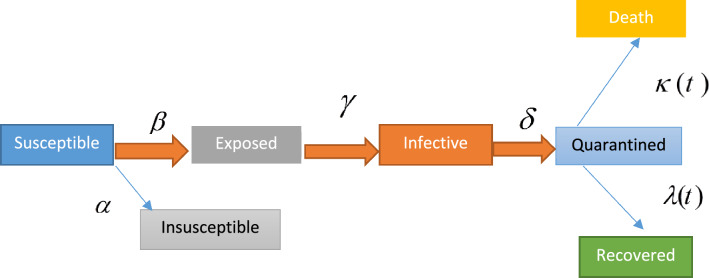

Several epidemic models have been used by researchers to estimate the outbreak in the short and long term [11–14]. The most applied epidemic models are the susceptible, infected, and recovered (SIR) model and susceptible, exposed, infected, and recovered (SEIR). The SIR model [15, 16] is described as shown in Fig. 5:

Fig. 5.

Susceptible, infected, and recovered (SIR) model

In terms of mathematical modeling, the SIR model is shown below [17]:

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

where S is the number of individuals susceptible at time t; I is the number of infected individuals at time t; R is the number of recovered individuals at time t; and and are the transmission rate and rate of recovery (removal), respectively. The SEIR model [18] is similar to the SIR model except that variable E is added for the fraction of individuals that have been infected but are asymptomatic. The SEIR model and the related equations are presented in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

The susceptible, exposed, infected, and recovered (SEIR) diagram [18]

The equations of the SEIR model are defined below:

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

where depicts the protection rate; is the infection rate; is the inverse of the average latent time; represents the inverse of the average quarantine time; are coefficients used in the time-dependent cure rate; and and are coefficients used in the time-dependent mortality rate [18].

Mathematical modeling

Ahmar and del Val [19] used the SutteARIMA method to forecast short-term confirmed cases of COVID-19 and Spain Market Index (IBEX 35). Comparatively, the SutteARIMA method was found to be more suitable for forecasting daily confirmed cases in Spain than the AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) based on the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) values. Al-qaness [20] suggested an improved version of the Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) based on the Flower Pollination Algorithm (FPA) by using the Salp Swarm Algorithm to forecast the number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 in China. The idea is to determine the parameters of the Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System using the hybrid of the Flower Pollination and Salp Swarm Algorithms. The performance of FPA was validated by comparing it with the existing modified ANFIS models, such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), genetic algorithm (GA), approximate Bayesian computation (ABC), and FPA. Anastassopoulou and Russo [21] proposed a method for predicting the reproduction number (R0) from the susceptible, infected, recovered, and deceased (SIRD) model and other key parameters in forecasting the spread of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Chakraborty and Ghosh [22] presented a real-time forecast of confirmed COVID-19 cases for multiple countries as well as a risk assessment of the novel COVID-19 for some profoundly affected countries using the regression tree algorithm. A simple moving average approach was used by [23] to predict COVID-19 confirmed cases in Pakistan. [24] used a five-parameter logistic growth model to reconstruct and forecast the COVID-19 epidemic in the USA; however, the authors claimed the accuracy of their model depends on federal- and state-level policy decisions. Cheng and Burcu [12] introduced a platform, icumonitoring.ch, to provide hospital-level projections for intensive care unit (ICU) occupancy based on SEIR models. The proposed platform could help ICU managers to estimate the need for additional resources and is updated every 3–4 days. Chimmula and Zhang [25] applied long short-term memory (LSTM) networks as a deep learning technique for predicting COVID-19 outbreaks in Canada. Their approach identified the key features for estimating the trends of the pandemic in Canada. A simple ARIMA model was proposed by [26] to estimate registered and recovered cases after a lockdown in Italy.

Salgotra and Gandomi [4] established two COVID-19 prediction models based on genetic programming in India. Their results indicate that genetic evolutionary programming models are highly reliable for COVID-19 cases in India. Dil and Dil [11] used the SIR model to forecast confirmed COVID-19 cases in the Eastern Mediterranean region, namely Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Lebanon, Egypt, and Pakistan, with a special focus on Pakistan. A simple SIRD model was proposed by [14] to predict COVID-19 outbreaks in China, Italy, and France and estimate healthcare facility necessities, such as ventilation units.

Criteria evaluation

Forecasting confirmed cases, risk assessment, stock market, ICU beds, registered and recovered cases are top criteria in which scholars show heightened interest.

Solution approaches

Several approaches have been addressed by researchers to predict the COVID-19 outbreak [27, 28]. Table 2 presents the solution approaches proposed by researchers for forecasting COVID-19, among which SIR, SEIR, SIRD, and Moving Average are the most popular approaches. Also, some researchers [29, 30] preferred to use hybrid algorithms to enhance the power of forecasting algorithms.

Table 2.

Proposed solution approaches for forecasting coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19)

| Algorithm | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemic models | Time-series models | Nature-inspired algorithms | ||||||

| SIR | [11] | Autoregressive model | Moving average | Autoregressive integrated moving average [19, 22, 26, 30, 31] | Genetic programming [30–34] | |||

| Simple moving average [23] | ||||||||

| Other models | [35] | |||||||

| SEIR | [12, 36] | Exponential models | Logistic growth model [24, 37, 38] | Flower pollination algorithm [29] | ||||

| SIRD | [13, 14] | Deep learning | Long short-term memory (LSTM) networks [25] | Polynomial Neural Network [39] | ||||

| Neural network [31, 40] | Ecological Niche models [41] | |||||||

| Regression methods | [42–44] | |||||||

| Prophet algorithm | [45] | |||||||

| Phenomenological model | [46] | Other models | Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system [29] | Regression tree algorithm [22] | Support vector machine [39, 47] | Iteration method [48] | Support vector Kuhn-tucker [47] | |

Autoregressive model

The autoregressive time-series model is known as a useful tool to model dependent data and has been applied to various real-world problems [49–53].

Moving average

In statistics and economics, a moving average is a way to calculate and analyze data by providing a series of averages of various subsets of the dataset [54].

Simple moving average

A simple moving average (SMA) is defined as the unweighted mean of the previous data (in finance) or an equal number of data on either side of a central value (in science or engineering) [54]. An example of an application of a simple moving average in COVID-19 could be found in [23].

Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA)

An autoregressive integrated moving average model is a generalized form of the autoregressive moving average model. As it is well known for forecasting, some researchers have used ARIMA to predict the spread of the new pandemic [31, 55–58].

Two-piece distributions based on the scale

Maleki M et al. [35] proposed an autoregressive time-series model based on two-piece scale mixture normal distribution to predict confirmed and recovered COVID-19 cases. Compared with the standard autoregressive time-series model, the proposed algorithm outperforms others in the forecasting the confirmed and recovered COVID-19 cases around the world.

Exponential models

Exponential models are suitable in the modeling of several phenomena, such as populations, interest rates, and infectious diseases [59].

Logistic functions

One of the famous S-shaped curves is logistic a function with application in biology, chemistry, linguistics, political science, and statistics. [24, 37, 38] provide examples of applications of logistic functions in COVID-19.

Deep learning

Deep learning is a famous branch of machine learning in which the learning process can be supervised, semi-supervised, unsupervised [60–62]. Application of different forms of deep learning in forecasting COVID-19 cases could be found in long short-term memory (LSTM) networks [25, 63], polynomial neural network [39], and neural network [31, 40].

Regression methods

In statistics, regression methods are a set of statistical modeling to estimate the relationship between a dependent variable and independent variable(s) [64, 65]. As a powerful tool to forecast the pandemic, various regression methods have been addressed by researchers against COVID-19 [42–44, 66, 67].

Prophet algorithm

The Prophet algorithm is an open-source tool that works well with time-series data that have seasonal effects. The main goal of the algorithm, developed by Facebook’s Data Science team, is business forecasting [68, 69]. The Prophet algorithm has proven to be robust in dealing with missing data [70].

Genetic programming

Genetic programming (GP) is a nature-inspired algorithm, where the keys include program representation (tree structure), selection, crossover, and mutation [71]. Some examples of GP in COVID-19 are available in [32–34].

SIR

One of the most applied epidemic models is the susceptible, infected, and recovered (SIR) model [15, 16]. Variables S, I, and R are defined in Eqs. 1–3.

SEIR

The SEIR model [18] is an extended version of the SIR model, which considers an additional parameter, E, representing the fraction of individuals that have been infected but are asymptomatic.

SIRD

The SIRD model differentiates between recovered individuals (those who have survived the disease and are now immune) and deceased individuals [13, 14].

Strengths and weaknesses of forecasting models

As discussed earlier, many machine learning algorithms have been used to forecast the new pandemic in different places of the world. Figure 7 presents the percentage of contribution of different solution approaches applied in forecasting COVID-19 confirmed cases (there are 925 indexed articles in Scopus as of October 10, 2020). As it is clear from Fig. 7, deep learning, compartmental models, and other methods have the most contributions, while the Prophet algorithm, as a new branch of machine learning, has the least contribution.

Fig. 7.

% of contribution of different solution approaches applied in the forecasting of COVID-19 confirmed cases

Machine learning algorithms exhibit many pros and cons, which are described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Strengths and weaknesses of proposed machine learning algorithms

| Algorithm | Strength | Weakness |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial neural network | Could access several training algorithms [72] | The nature of being a black box [72], overtraining [73] |

| Support vector machine | Can avoid overfitting and defining a convex optimization problem [72] | Choice of the kernel as well as speed and size of training and testing sets [72] |

| Compartmental models (SIR, SEIR, SIRD, etc.) |

Predict how the disease spreads Present the effects of public health interventions on the outcome of the pandemic [74–78] |

The proposed models are mostly deterministic and work with large populations [79] |

| Nature-inspired algorithms (genetic programming) |

Intelligent search [80] Can integrate with certain decomposition algorithms [81] |

Several parameters should be set by the decision-makers The algorithms are approximate and usually nondeterministic [82] |

| Prophet algorithm | Are robust in dealing with missing data [70] |

It is hard to use the algorithm for Multiplicative models Predefined format is needed for data before using the algorithm |

| ARIMA |

Works for seasonal and nonseasonal models Outliers can be handled well |

Changes in observations and changes in model specification make the model unstable [83] |

| Deep learning | Results comparable to human expert performance [84, 85] |

Requires large amounts of data The training process is expensive |

Conclusion and discussion

At the time of writing, COVID-19 had spread to more than 200 countries worldwide with more than 36 million confirmed cases. Several works have been released in the field for predicting global outbreaks. This study aimed to review the most important forecasting models for COVID-19 and provides a short analysis of published literature. This paper highlighted the most important subject areas by keywords analysis. Moreover, several criteria were identified that could help researchers for future works. Also, this paper recognized the most useful models that researchers have applied for predicting this pandemic. Furthermore, this paper may help researchers to identify important gaps in the research area and, subsequently, develop new machine learning models for forecasting the COVID-19 cases. A detailed scientometric analysis was performed as an influential tool for use in bibliometric analyses and reviews. For this aim, keywords and subject areas are discussed, while the classification of forecasting models, criteria evaluation, and comparison of solution methods are provided in the second section of the work.

This study describes some key arguments that are worthy of further discussion:

In terms of the subject area, medicine, biochemistry, and mathematics are most discussed areas addressed by scholars.

In terms of keywords analysis, trends present that studies on COVID-19 will increase in the next few months. Moreover, Coronavirus, prediction, epidemic, human, statistical analysis, quarantine, hospitalization, mortality, and weather instances are the most interesting keywords for scholars.

- Several other criteria have been used by researchers in forecasting, including:

- Confirmed cases, risk assessment, stock market, ventilation units, ICU beds, estimated registered and recovered cases.

Several countries, including China, Pakistan, France, Italy, USA, UK, Brazil, Nigeria, Iran, Germany, and India, were addressed as case studies.

Among the epidemic models, deep learning, SIR, and SEIR are the top models that were used by researchers.

Hybrid algorithms are used to enhance the power of forecasting approaches.

The majority of studies are deterministic approaches, while there is an urgent need to provide robust approaches for tackling uncertain situations.

For future research directions, a comprehensive review in other fields, such as artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning, is encouraged. Moreover, more studies addressing the development of novel and hybrid approaches to forecast the pandemic should be investigated. Furthermore, at the time of writing this paper, we had access to only a limited number of published articles by Scopus and WOS. However, the most important parts of this paper are the keywords and scientometric analysis that consider the whole database, from which we chose some examples of published articles for review. Therefore, a more comprehensive review in the research area is suggested.

Funding

The authors confirm that there is no source of funding for this study.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Putra S, Khozin Mutamar Z. Estimation of parameters in the SIR epidemic model using particle swarm optimization. Am J Math Comput Model. 2019;4(4):83–93. doi: 10.11648/j.ajmcm.20190404.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mbuvha RR, Marwala T (2020) On data-driven management of the COVID-19 outbreak in South Africa. medRxiv

- 3.Qi H et al (2020) COVID-19 transmission in Mainland China is associated with temperature and humidity: a time-series analysis, p 138778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Salgotra R, Gandomi M, Gandomi AH. Time series analysis and forecast of the COVID-19 pandemic in india using genetic programming. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;138:109945. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahalle P et al (2020) Forecasting models for coronavirus (covid-19): a survey of the state-of-the-art. TechRxiv. 10.36227/techrxiv.12101547.v1(Preprint) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Naudé W (2020) Artificial intelligence against COVID-19: an early review. IZA Discussion Paper No. 13110. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3568314

- 7.Shrivastava R, Mahajan PJS, Libraries T. Artificial intelligence research in India: a scientometric analysis. Sci Technol Libr. 2016;35(2):136–151. doi: 10.1080/0194262X.2016.1181023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su H-N, Lee P-CJS. Mapping knowledge structure by keyword co-occurrence: a first look at journal papers in technology foresight. Scientometrics. 2010;85(1):65–79. doi: 10.1007/s11192-010-0259-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Eck NJ, Waltman L. Visualizing bibliometric networks. In: Ding Y, Rousseau R, Wolfram D, editors. Measuring scholarly impact. Berlin: Springer; 2014. pp. 285–320. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Eck NJ, Waltman L. VOSviewer manual, Leiden: Univeristeit Leiden; 2013. pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dil S, Dil N, Maken ZH. COVID-19 trends and forecast in the eastern mediterranean region with a particular focus on Pakistan. Cureus. 2020;12(6):8. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng Z, et al. icumonitoring.ch: a platform for short-term forecasting of intensive care unit occupancy during the COVID-19 epidemic in Switzerland. Swiss Med Weekly. 2020;150:10. doi: 10.4414/smw.2020.20277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anastassopoulou C, et al. Data-based analysis, modelling and forecasting of the COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(3):21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fanelli D, Piazza F. Analysis and forecast of COVID-19 spreading in China, Italy and France. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;134:5. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kermack WO, McKendrick AG. Contributions to the mathematical theory of epidemics. II: the problem of endemicity. Proc R Soc Lond Ser A. 1932;138(834):55–83. doi: 10.1098/rspa.1932.0171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capasso V, Serio G. A generalization of the Kermack–McKendrick deterministic epidemic model. Math Biosci. 1978;42(1–2):43–61. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(78)90006-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss HH. The SIR model and the foundations of public health. Mater Mat. 2013;2013(3):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng L et al (2020) Epidemic analysis of COVID-19 in China by dynamical modeling. arXiv:2002.06563

- 19.Ahmar AS, del Val EB. SutteARIMA: short-term forecasting method, a case—Covid-19 and stock market in Spain. Sci Total Environ. 2020;729:138883. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-qaness MAA, et al. Optimization method for forecasting confirmed cases of COVID-19 in China. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3):674. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anastassopoulou C, et al. Data-based analysis, modelling and forecasting of the COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(3):e0230405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chakraborty T, Ghosh I. Real-time forecasts and risk assessment of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) cases: a data-driven analysis. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;135:10. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaudhry RM, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): forecast of an emerging urgency in Pakistan. Cureus. 2020;12(5):15. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen DG, Chen XG, Chen JK. Reconstructing and forecasting the COVID-19 epidemic in the United States using a 5-parameter logistic growth model. Glob Health Res Policy. 2020;5(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s41256-020-00137-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chimmula VKR, Zhang L. Time series forecasting of COVID-19 transmission in Canada using LSTM networks. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;135:6. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chintalapudi N, Battineni G, Amenta F. COVID-19 virus outbreak forecasting of registered and recovered cases after sixty day lockdown in Italy: a data driven model approach. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53(3):396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kavadi DP, Patan R, Ramachandran M, Gandomi AH. Partial derivative nonlinear global pandemic machine learning prediction of COVID-19. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mousavi M, Salgotra R, Holloway D, Gandomi AH COVID-19 time series forecast using transmission rate and meteorological parameters as features. IEEE Comput Intell Mag (in press). 10.1109/mci.2020.3019895

- 29.Al-qaness MAA, et al. Optimization method for forecasting confirmed cases of COVID-19 in China. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3):15. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh S, et al. Development of new hybrid model of discrete wavelet decomposition and autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models in application to one month forecast the casualties cases of COVID-19. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;135:8. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moftakhar L, Seif M, Safe MS. Exponentially increasing trend of infected patients with COVID-19 in Iran: a comparison of neural network and ARIMA forecasting models. Iran J Public Health. 2020;49:92–100. doi: 10.18502/ijph.v49iS1.3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salgotra R, et al. Time series analysis and forecast of the COVID-19 pandemic in India using genetic programming. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;138:109945. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salgotra R, Gandomi M, Gandomi AH. Evolutionary modelling of the COVID-19 pandemic in fifteen most affected countries. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salgotra R, Gandomi AH (in press) Time series analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia using genetic programming. In: Kose U et al (eds) Data science for COVID 19. Elsevier

- 35.Maleki M, et al. Time series modelling to forecast the confirmed and recovered cases of COVID-19. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;37:101742. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reno C, et al. Forecasting COVID-19-associated hospitalizations under different levels of social distancing in Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna, Northern Italy: results from an extended SEIR compartmental model. J Clin Med. 2020;9(5):11. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Q, Feng W, Quan YH. Trend and forecasting of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. J Infect. 2020;80(4):472–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qeadan F, et al. Naive forecast for COVID-19 in Utah based on the South Korea and Italy models-the fluctuation between two extremes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fong SJ, et al. Finding an accurate early forecasting model from small dataset: a case of 2019-nCoV novel coronavirus outbreak. Int J Interact Multimed Artif Intell. 2020;6(1):132–140. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tamang SK, Singh PD, Datta B. Forecasting of Covid-19 cases based on prediction using artificial neural network curve fitting technique. Glob J Environ Sci Manag. 2020;6:53–64. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ren HY, et al. Early forecasting of the potential risk zones of COVID-19 in China’s megacities. Sci Total Environ. 2020;729:8. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ji D, et al. Prediction for progression risk in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: the CALL Score. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(6):1393–1399. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ribeiro MHDM, et al. Short-term forecasting COVID-19 cumulative confirmed cases: perspectives for Brazil. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;135:109853. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sujath R, et al. A machine learning forecasting model for COVID-19 pandemic in India. Stochast Environ Res Risk Assess. 2020;34:959–972. doi: 10.1007/s00477-020-01827-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abdulmajeed K, Adeleke M, Popoola LJD. Online forecasting of Covid-19 cases in Nigeria using limited data. Data Brief. 2020;30:105683. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.105683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roosa K, et al. Real-time forecasts of the COVID-19 epidemic in China from February 5th to February 24th, 2020. Infect Dis Model. 2020;5:256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parbat, D.J.C., Solitons and Fractals, A Python based Support Vector Regression Model for prediction of Covid19 cases in India. 2020: p. 109942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Perc M, et al. Forecasting Covid-19. Front Phys. 2020;8:127. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2020.00127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maleki M, Arellano-Valle RB. Maximum a posteriori estimation of autoregressive processes based on finite mixtures of scale-mixtures of skew-normal distributions. J Stat Comput Simul. 2017;87(6):1061–1083. doi: 10.1080/00949655.2016.1245305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maleki M, Nematollahi AJ, Technology TAS. Autoregressive models with mixture of scale mixtures of Gaussian innovations. Iran J Sci Technol Trans A Sci. 2017;41(4):1099–1107. doi: 10.1007/s40995-017-0237-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zarrin P, et al. Time series models based on the unrestricted skew-normal process. J Stat Comput Simul. 2019;89(1):38–51. doi: 10.1080/00949655.2018.1533962. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maleki M, et al. A Bayesian approach to robust skewed autoregressive processes. Calcutta Stat Assoc Bull. 2017;69(2):165–182. doi: 10.1177/0008068317732196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hajrajabi A, Maleki MJ. Nonlinear semiparametric autoregressive model with finite mixtures of scale mixtures of skew normal innovations. J Appl Stat. 2019;46(11):2010–2029. doi: 10.1080/02664763.2019.1575953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sprinthall RC, Fisk ST. Basic statistical analysis. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roy S, Bhunia GS, Shit PK. Spatial prediction of COVID-19 epidemic using ARIMA techniques in India. Model Earth Syst Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40808-020-00890-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alzahrani SI, et al. Forecasting the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia using ARIMA prediction model under current public health interventions. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13:914–919. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kufel TJ. ARIMA-based forecasting of the dynamics of confirmed Covid-19 cases for selected European countries. Equilib Q J Econ Econ Policy. 2020;15(2):181–204. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singh S, et al. Development of new hybrid model of discrete wavelet decomposition and autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models in application to one month forecast the casualties cases of COVID-19. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;135:109866. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith BAJIDM. A novel IDEA: the impact of serial interval on a modified-incidence decay and exponential adjustment (m-IDEA) model for projections of daily COVID-19 cases. Infect Dis Model. 2020;5:346–356. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bengio Y, et al. Representation learning: a review and new perspectives. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2013;35(8):1798–1828. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2013.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmidhuber JJ. Deep learning in neural networks: an overview. Neural Netw. 2015;61:85–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton GJ. Deep learning. Nature. 2015;521(7553):436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature14539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ayyoubzadeh SM, et al. Predicting COVID-19 incidence through analysis of Google trends data in Iran: data mining and deep learning pilot study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e18828. doi: 10.2196/18828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Freedman DA. Statistical models: theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cook RD, Weisberg SJ. Criticism and influence analysis in regression. Sociol Methodol. 1982;13:313–361. doi: 10.2307/270724. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Velásquez RMA, Lara JVMJC. Forecast and evaluation of COVID-19 spreading in USA with reduced-space Gaussian process regression. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;136:109924. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Almeshal AM, et al. Forecasting the spread of COVID-19 in Kuwait using compartmental and logistic regression models. Appl Sci. 2020;10(10):3402. doi: 10.3390/app10103402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taylor SJ, Letham B. Forecasting at scale. Am Stat. 2018;72(1):37–45. doi: 10.1080/00031305.2017.1380080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Taylor S, Letham B (2017) Prophet: automatic forecasting procedure. R package version 0.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=prophet

- 70.Ndiaye BM, Tendeng L, Seck D (2020) Analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic by SIR model and machine learning technics for forecasting. arXiv:2004.01574

- 71.Banzhaf W, et al. Genetic programming. Berlin: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jalalkamali A, et al. Application of several artificial intelligence models and ARIMAX model for forecasting drought using the Standardized Precipitation Index. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2015;12(4):1201–1210. doi: 10.1007/s13762-014-0717-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wilamowski BMJIIEM. Neural network architectures and learning algorithms. IEEE Ind Electron Mag. 2009;3(4):56–63. doi: 10.1109/MIE.2009.934790. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hethcote HW. Three basic epidemiological models. In: Levin SA, Hallam TG, Gross LJ, editors. Applied mathematical ecology. Berlin: Springer; 1989. pp. 119–144. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brauer F, Castillo-Chavez C. Mathematical models in population biology and epidemiology. Berlin: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nunn C, Altizer S, Altizer SM. Infectious diseases in primates: behavior, ecology and evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gao S, et al. Analysis of an SIR epidemic model with pulse vaccination and distributed time delay. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2007;2007:64870. doi: 10.1155/2007/64870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rahimi I, Gandomi AH, Chen F et al (2020) Analysis and prediction of COVID-19 using SIR, SEIR, and machine learning models: Australia, Italy, and UK Cases, 13 October 2020, PREPRINT (version 1) available at Research Square. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-85513/v1

- 79.Bartlett MS. Measles periodicity and community size. J R Stat Soc Ser A. 1957;120(1):48–70. doi: 10.2307/2342553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Glover F, Laguna M. Handbook of combinatorial optimization. Boston, MA: Springer; 1998. Tabu search; pp. 2093–2229. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Poojari CA, Beasley JE. Improving benders decomposition using a genetic algorithm. Eur J Oper Res. 2009;199(1):89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2008.10.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Blum C, Roli AJ. Metaheuristics in combinatorial optimization: overview and conceptual comparison. ACM Comput Surv. 2003;35(3):268–308. doi: 10.1145/937503.937505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Makridakis S, Hibon MJ. ARMA models and the Box-Jenkins methodology. J Forecast. 1997;16(3):147–163. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-131X(199705)16:3<147::AID-FOR652>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ciregan D, Meier U, Schmidhuber J (2012) Multi-column deep neural networks for image classification. In: 2012 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. IEEE

- 85.Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun ACM. 2017;60(6):84–90. doi: 10.1145/3065386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]