Abstract

Purpose

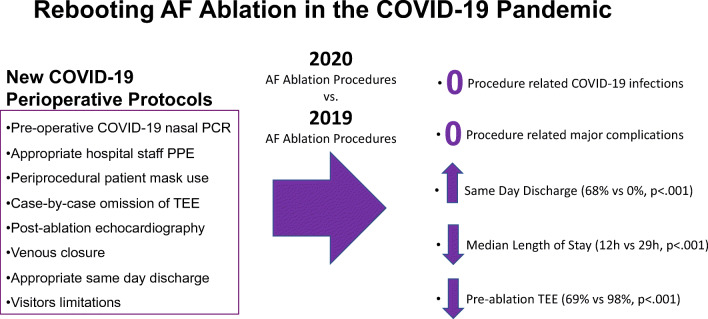

Catheter ablation procedures for atrial fibrillation (AF) were significantly curtailed during the peak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic to conserve healthcare resources and limit exposure. There is little data regarding peri-procedural outcomes of medical procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic. We enacted protocols to safely reboot AF ablation while limiting healthcare resource utilization. We aimed to evaluate acute and subacute outcomes of protocols instituted for reboot of AF ablation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Perioperative healthcare utilization and acute procedural outcomes were analyzed for consecutive patients undergoing AF ablation under COVID-19 protocols (2020 cohort; n=111) and compared to those of patients who underwent AF ablation during the same time period in 2019 (2019 cohort; n=200). Newly implemented practices included preoperative COVID-19 testing, selective transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), utilization of venous closure, and same-day discharge when clinically appropriate.

Results

Pre-ablation COVID-19 testing was positive in 1 of 111 patients. There were 0 cases ablation-related COVID-19 transmission and 0 major complications in either cohort. Pre-procedure TEE was performed in significantly fewer 2020 cohort patients compared to the 2019 cohort patients (68.4% vs. 97.5%, p <0.001, respectively) despite greater prevalence of persistent arrhythmia in the 2020 cohort. Same-day discharge was achieved in 68% of patients in the 2020 cohort, compared to 0% of patients in the 2019 cohort.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate the feasibility of safe resumption of complex electrophysiology procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic, reducing healthcare utilization and maintaining quality of care. Protocols instituted may be generalizable to other types of procedures and settings.

Graphical abstract

Keywords: COVID, Atrial fibrillation, Catheter ablation, Radiofrequency ablation, Procedural outcomes

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) resulted in curtailment of non-emergent medical care in order to limit exposure to patients and healthcare workers and preserve limited personal protective equipment (PPE) [1]. Meeting the challenges of peak COVID-19 infection resulted in reassignment of hospital beds and repurposing of personnel throughout the USA. Electrophysiology programs like ours, in accordance with recommendations collectively provided by professional societies[1, 2] and local regulations, prioritized urgent electrophysiological procedures during periods of high healthcare utilization related to COVID-19 [3]. These efforts have helped to minimize patient and healthcare professional exposure by postponement of elective cases and careful management of urgent or otherwise time-sensitive conditions.

As local COVID-19 cases ebb and healthcare resource availability are less constrained, uncertainty remains regarding best practices for re-initiating less urgent procedures. In addition, there has been increasing recognition of morbidity and mortality associated with delays in cardiac care, including arrhythmia procedures such as ablation for those with severe symptoms from atrial fibrillation (AF) or atrial flutter [4].

Catheter ablation of AF is most frequently performed with overnight post-procedure monitoring. Rhythm control via cardioversion or catheter ablation is an important means of reducing AF-related hospitalization [5]. The limited prior literature regarding the safety of same-day discharge following AF ablation has included procedures performed under conscious sedation [6], using cryoballoon technology, and/or with 4-h post-procedure bed rest [6]. A minority of patients were discharged on the day of catheter ablation in a recent study reporting outcomes of same-day discharge following radiofrequency ablation of AF under general anesthesia [7]. We sought to implement policies and procedures to ensure safety of patients and healthcare workers, while reducing utilization of healthcare resources and maintaining quality of care for AF ablation performed under general anesthesia with high-frequency jet ventilation. We systematically evaluated acute and subacute outcomes of these interventions as a quality initiative.

Methods

All elective procedures in New York City were canceled following an executive order on March 16, 2020, and on June 8, 2020, all New York City Hospitals were authorized to resume elective procedures. In the period between March 16, 2020, and June 8, 2020, as safety protocols were enacted and healthcare resources became more available, medically necessary, non-emergent procedures were performed after detailed discussion of risks and benefits with patients. Patients were prioritized based on severity of AF-related symptoms, cardiomyopathy risk, and frequency of AF-related healthcare utilization.

Baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes were evaluated in two cohorts of consecutive patients undergoing catheter ablation of AF or prior AF-ablation-related atrial arrhythmia at New York University (NYU) Langone Health. The 2020 cohort included 111 patients that underwent catheter ablation between April 15, 2020, and June 15, 2020, with COVID-19-related policies and procedures in-effect, for whom data was collected prospectively. The 2019 cohort included 200 consecutive patients that underwent catheter ablation between April 15, 2019, and June 15, 2019, for whom data was collected retrospectively. All electrophysiology lab staff underwent COVID-19 initial nasal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, were monitored for new COVID-19 infection symptoms throughout the study period, and underwent repeat testing based on symptoms and high-risk exposures. In-hospital time was defined as time from presentation to the electrophysiology lab preoperative area to the time of discharge from the hospital.

COVID-19-related interventions

Interventions to ensure the safety of patients and healthcare workers while reducing utilization of healthcare resources in 2020 cohort included the following:

Preoperative COVID-19 nasal PCR

Appropriate personal protective equipment use by all hospital staff including N95 masks and face shields for all patient care activities

Peri-procedural mask use by all patients

Case-by-case assessment for omission of pre-ablation transesophageal echocardiography (TEE)

Post-ablation echocardiographic pericardial evaluation to rule out pericardial effusion

Venous closure of two, unilateral venous access sites to allow ambulation 2 h after sheath removal [8]

Same-day discharge when clinically appropriate

Staged re-introduction of limited visitors with monitoring for appropriate PPE

In order to preserve PPE, N95 masks and face shields were reused until they were felt to be no longer effective. Necessity of preoperative TEE was determined by the attending cardiac electrophysiologist based on factors including presenting rhythm, preoperative adherence to anticoagulation, CHA2DS2-VASc score, and prior echocardiographic findings.

Criteria utilized to evaluate appropriateness of same-day discharge included the following:

Absence of pericardial effusion on point-of-care post-procedure transthoracic echocardiogram

Absence of hematoma, bleeding, or discharge 4 h after sheath removal and achievement of hemostasis

Stable vital signs during the 4-h period of observation

Return to baseline ambulatory status

Spontaneous urinary voiding

Return to baseline mental status

Patients who experienced minor bleeding related to femoral access during the observation period were observed for at least 4 h after hemostasis was re-established.

Electrophysiology study and ablation

Data collection and analysis were performed according to protocols approved by the NYU Langone Health Institutional Review Board. Surface and intracardiac electrograms were digitally recorded and stored (EP Workmate, Abbott Medical, Inc.). Non-fluoroscopic 3-dimensional mapping was performed using the Carto 3 (Biosense Webster, Inc.) mapping system.

All procedures were performed under general anesthesia with high-frequency jet ventilation. A 7-French 20-pole catheter (Daig DuoDeca 2-10-2, Abbott Medical, Inc.) was used with the distal poles placed within the coronary sinus and the proximal electrodes located along the tricuspid annulus in the lateral and inferior right atrium. For left atrial mapping and recording, a 10- or 20-pole circumferential PV mapping catheter (Lasso, Biosense-Webster, Inc.) or a five-spline mapping catheter (PentaRay Nav, Biosense-Webster, Inc.) was utilized. Left atrial three-dimensional anatomy and voltage mapping were created with manipulation of the multi-electrode mapping catheter. Ablation was performed in each group with an open-irrigated, 3.5-mm RFA catheter (Thermocool SMARTTOUCH SF, Biosense Webster Inc.). Ablation lesions were generated in a power-controlled mode applying 35 to 50 W for 6 to 30 s per lesion during irrigation at a rate of 8 to 15-mL/min while maintaining a goal ACT of > 350 s. A waiting period of 30 min, followed by administration of adenosine, was utilized to confirm pulmonary venous entrance and exit block. A major complication is a complication that results in permanent injury or death, requires intervention for treatment, or prolongs or requires hospitalization for more than 48 h [9]. All patients received in-person or telehealth post-procedure follow-up 10 to 20 days after discharge, and all patient charts were reviewed 30 days after discharge.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 14.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic characteristics. Continuous variables were assessed for normality with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. All normally distributed data were analyzed using an unpaired Student t test. A 2-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data found to be non-normally distributed were analyzed using Mann–Whitney U test. Comparisons of proportions between different groups of patients were carried out using a Chi square and Fisher’s exact test.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the 2020 cohort and the 2019 cohort are displayed in Table 1. Patients in the 2020 cohort were more likely to have prior history of stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA) in comparison to the 2019 cohort (14% and 6%, p=0.03) and more often presented with persistent atrial arrhythmia (50% and 32%, respectively, p<0.01). On the first day of the study period (April 15, 2020), there were 9282 COVID-19 tests performed in New York City, of which 4368 (38%) were positive tests [10]. On the last day of the study period (June 15, 2020), there were 25,754 COVID-19 tests performed in New York City, of which 639 (1.7%) were positive tests [10].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| All patients (n = 311) |

2020 (n = 111) |

2019 (n = 200) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 66 + 11 | 67 + 10 | 66 + 12 | 0.4 |

| Male (%) | 205 (66) | 77 (69) | 128 (64) | 0.6 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29 + 6 | 29 + 6 | 29 + 6 | 1 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0 + 0.3 | 1.0 + 0.3 | 1.0 + 0.3 | 0.2 |

| LA diameter (cm) | 4.3 + 0.7 | 4.0 + 0.7 | 4.3 + 0.7 | 0.3 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 58 (10) | 58 (12) | 58 (9) | 0.7 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 2.4 + 1.7 | 2.0 + 1.6 | 2.4 + 1.7 | 0.8 |

| Hypertension (%) | 188 (61) | 71 (64) | 117 (59) | 0.5 |

| Diabetes (%) | 45 (15) | 12 (11) | 33 (16) | 0.2 |

| Coronary disease (%) | 57 (18) | 20 (18) | 37 (18) | 0.9 |

| Stroke or TIA (%) | 27 (9) | 15 (14) | 12 (6) | 0.03 |

| Heart failure (%) | 48 (15) | 16 (14) | 32 (16) | 0.7 |

| Persistent AF (%) | 121 (39) | 56 (50) | 65 (32) | <0.01 |

Procedural outcomes

All 111 patients in the 2020 cohort underwent preoperative COVID-19 nasal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, of whom 1 (0.9%) asymptomatic patient tested positive. Following detailed discussion of risks and benefits with patient and healthcare staff, the procedure was completed in this patient without acute complication. COVID-19 nasal PCR testing was performed on the day of the procedure in 29 of 111 patients (26%) and 1–3 days prior to the procedure in 82 of 111 patients (74%). At 30-day follow-up, 0 of 110 (0%) patients of 2020 cohort were diagnosed with new COVID-19 infection. Fewer patients underwent preoperative TEE in 2020 compared to 2019 (76 of 111 patients (68.4%) vs. 195 of 200 patients (97.5%), respectively, p<.001).

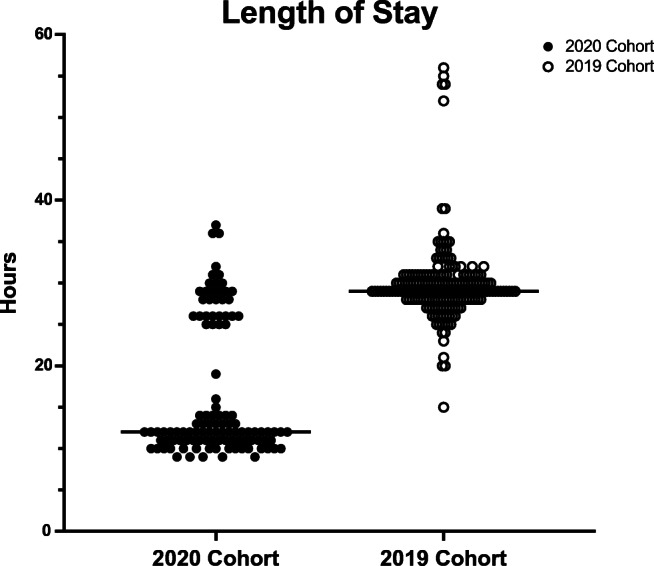

Same-day discharge was achieved in 76 of 111 patients (68.4%) in the 2020 cohort compared to 0 of 200 patients (0%) in the 2019 cohort. Vascular closure was unsuccessful in 3 of 111 patients (2.7%), 1 of whom was discharged the same day after an extended period of observation. Overnight observation was required in 35 of 111 patients (31.6%). The most common reason for overnight observation was late procedure end time (n = 13, Table 2). Median 2020 cohort in-hospital length of stay, defined as the duration of time in hours between patient check-in to patient discharge, was significantly shorter than that of the 2019 cohort (12h [IQR 11–26h] vs. 29h [IQR 28–31h], p < 0.001, Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Procedure-related complications

| 2019 n=200 (%) |

2020 n=111 (%) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major complications | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| CHF exacerbation | 3 (1.5) | 2 (1.8) | 0.8 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0.9 |

| Access site hematoma | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.9) | 0.7 |

| Pericarditis | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.9) | 0.7 |

| Anesthesia related | 3 (1.5) | 2 (1.8) | 0.8 |

| All complications | 9 (4.50) | 6 (5.4) | 0.7 |

Data presented as number of patients (%). CHF congestive heart failure

Fig. 1.

Scatter plot displaying length of stay in hours for the 2020 cohort of atrial fibrillation ablation patients under COVID-19 protocols and the 2019 cohort of atrial fibrillation ablation patients under usual care

There were no major complications in either cohort, and there was no significant difference in overall procedure-related complications at 30 days between the 2020 cohort and the 2019 cohort (5.4% and 4.5%, respectively, p=0.71, Table 3). Two patients (2%) developed heart failure exacerbation requiring hospitalization or emergency room visit in the 2020 cohort compared to 3 patients (1.5%) in the 2019 cohort (p=0.83). Among 76 patients who were discharged on the day of their procedure, one patient (1.3%) re-presented within 48 h. This patient presented to the emergency room for evaluation of chest pain, was diagnosed with pericarditis without significant pericardial effusion, and was discharged after initiating medical therapy.

Table 3.

Reasons for overnight observation in 2020

| Reason for overnight observation | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Late procedure end time | 13 |

| Patient preference | 4 |

| Groin access site bleeding | 3 |

| Discharge planning | 2 |

| Anesthesia complications | 3 |

| Escort unavailable | 2 |

| Vasovagal episode | 2 |

| Post-operative bradycardia | 2 |

| Urinary retention | 2 |

| Pulmonary edema | 1 |

| Post-operative hypotension | 1 |

Discussion

The COVID-19 global pandemic continues regional resurgence despite containment efforts. Following the initial peak of local infection in New York City, as healthcare resource availability allowed resumption of non-emergent procedures, we instituted measures to ensure patient and hospital staff safety while reducing healthcare resource utilization. Our key COVID-19 pandemic-related interventions included (1) COVID-19 nasal PCR testing for all electrophysiology lab staff and for all patients within 72 h prior to a scheduled ablation procedure, (2) reducing pre-procedure TEE utilization, (3) utilization of a venous closure device to facilitate early ambulation and same-day discharge, and (4) staged re-introduction of limited visitors with monitoring for appropriate PPE.

The main findings of our reboot of AF ablation in the setting of significant local COVID-19 prevalence are as follows: (1) zero new COVID-19 infections in patients 30 days post-ablation; (2) zero cases of new COVID-19 infections among electrophysiology lab staff; (3) same-day discharge achieved in 68% of patients in the 2020 cohort, compared to 0% of patients in the 2019 cohort; (4) significantly reduced median duration of hospitalization in the 2020 cohort compared to the 2019 cohort (12h vs. 29h, p<0.001, respectively): and (5) significantly reduced utilization of pre-procedure TEE in the 2020 cohort compared to the 2019 cohort (68.4% vs. 97.5%, p <0.001, respectively) despite greater prevalence of persistent arrhythmia in the 2020 cohort. Although performance of nasal PCR COVID-19 testing in all lab staff at the start of the study period yielded no positive results, value of this testing likely includes increased confidence in the safety of the electrophysiology lab environment for patients and staff.

In contrast to prior reports of same-day discharge after AF ablation, all patients in our 2020 cohort underwent radiofrequency ablation under general anesthesia with high-frequency jet ventilation. Additionally, 2020 cohort patients had a higher prevalence of comorbidities including stroke/TIA and persistent atrial arrhythmias when compared to patients in the 2019 cohort. Despite these patient characteristics and accelerated post-ablation discharge, there was no significant difference in the procedure-related complications between cohorts. The advantage of same-day discharge was twofold. First, this reduced the probability of patients’ COVID-19 exposure, and second, it reduced the need for overnight observation beds which could be potentially utilized for patients with acute illnesses during the pandemic.

Limitations

This is a single-center, non-randomized, observational study; thus, the generalizability of these findings remains unclear. While outcomes are reported for a single procedure type, radiofrequency ablation of atrial fibrillation under general anesthesia is a complex procedure performed in patients with substantial comorbidities. Our pilot data requires multi-center validation.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate the feasibility of safe resumption of complex electrophysiology procedures, reducing healthcare utilization and maintaining quality of care. COVID-19 pandemic-related interventions that we undertook to “reboot” AF ablation in the electrophysiology lab provide pilot data that may be generalizable to other types of procedures and settings.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- PPE

Personal protective equipment

- AF

Atrial fibrillation

- NYU

New York University

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

Author contribution

All authors contributed substantively to the study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript drafting, and/or manuscript revision.

Availability of data and material

Available upon request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Protocol approved by the NYU School of Medicine IRB.

Consent to participate

Consent obtained.

Consent for publication

Consent obtained.

Conflict of interest

Relationships to industry are all modest (< $10,000). Dr. Barbhaiya has received consulting fees/honoraria from Abbott, Inc., Biosense Webster, Inc., and Zoll, Inc. Dr. Holmes has research support from Abbott. Dr. Aizer has served as a consultant for Biosense Webster, Inc., received research support from Abbott Inc. and Sentreheart, Inc., and received fellowship support from Abbott, Inc., Biotronik, Inc., Boston Scientific, Inc., and Medtronic, Inc. Dr. Chinitz has received speaking fees/honoraria from Abbott, Medtronic, Biotronik, and Biosense and fellowship/research support from Medtronic, Biotronik, and Biosense.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lakkireddy DR, Chung MK, Deering TF, Gopinathannair R, Albert CM, Epstein LM, et al. Guidance for rebooting electrophysiology through the COVID-19 pandemic from the Heart Rhythm Society and the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology: endorsed by the American College of Cardiology. Heart Rhythm. 2020. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Diaz A, Sarac BA, Schoenbrunner AR, Janis JE, Pawlik TM. Elective surgery in the time of COVID-19. Am J Surg. 2020;219(6):900–902. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubin GA, Wan EY, Saluja D, Thomas G, Slotwiner DJ, Goldbarg S, Chaudhary S, Turitto G, Dizon J, Yarmohammadi H, Ehlert F, Rubin DA, Morrow JP, Waase M, Berman J, Kushnir A, Abrams MP, Halik C, Kumaraiah D, Schwartz A, Kirtane A, Kodali S, Goldenthal I, Garan H, Biviano A. Restructuring electrophysiology during the COVID-19 pandemic: a practical guide from a New York City Hospital Network. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2020;19(3):105–111. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0000000000000225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, Sala Z, Shakya I, Thierry JM, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19–related concerns — United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1250–1257. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4externalicon. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tripathi B, Atti V, Kumar V, Naraparaju V, Sharma P, Arora S, Wojtaszek E, Gopalan R, Siontis KC, Gersh BJ, Deshmukh A. Outcomes and resource utilization associated with readmissions after atrial fibrillation hospitalizations. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(19):e013026. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haegeli LM, Duru F, Lockwood EE, Luscher TF, Sterns LD, Novak PG, Leather RA. Feasibility and safety of outpatient radiofrequency catheter ablation procedures for atrial fibrillation. Postgrad Med J. 2010;86(1017):395–398. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2009.092510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ignacio M, Jarma JJ, Nicolas V, Gustavo D, Leandro T, Milagros C, et al. Current safety of pulmonary vein isolation in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: first experience of same day discharge. J Atr Fibrillation. 2019;11(4). 10.4022/jafib.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Natale A, Mohanty S, Liu PY, Mittal S, Al-Ahmad A, De Lurgio DB, et al. Venous vascular closure system versus manual compression following multiple access electrophysiology procedures: the AMBULATE Trial. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2020;6(1):111–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2019.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calkins H, Kuck KH, Cappato R, Brugada J, Camm AJ, Chen SA, et al. 2012 HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: recommendations for patient selection, procedural techniques, patient management and follow-up, definitions, endpoints, and research trial design. Europace. 2012;14(4):528–606. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.COVID-19: Data. NYC Health. 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Available upon request.

Not applicable.