Abstract

An ultraflexible and stretchable field-effect transistor nanosensor is presented that uses aptamer-functionalized monolayer graphene as the conducting channel. Specific binding of the aptamer with the target biomarker induces a change in the carrier concentration of the graphene, which is measured to determine the biomarker concentration. Based on a Mylar substrate that is only 2.5-μm thick, the nanosensor is capable of conforming to underlying surfaces (e.g., those of human tissue or skin) that undergo large bending, twisting, and stretching deformations. In experimental testing, the device is rolled on cylindrical surfaces with radii down to 40 μm, twisted by angles ranging from −180° to 180°, or stretched by extensions up to 125%. With these large deformations applied either cyclically or non-recurrently, the device is shown to incur no visible mechanical damage, maintain consistent electrical properties, and allow detection of TNF-α, an inflammatory cytokine biomarker, with consistently high selectivity and low limit of detection (down to 5 × 10−12M). The nanosensor can thus potentially enable consistent and reliable detection of liquid-borne biomarkers on human skin or tissue surfaces that undergo large mechanical deformations.

Keywords: aptamer, implantable sensor, flexible graphene nanosensor, TNF-α, wearable sensor

1. Introduction

Sensors that measure physiological and biochemical parameters are of great importance in human health monitoring and clinical diagnostics.[1,2] In particular, sensors deployed on the human skin or implanted in the human body have the potential to provide clinical-quality data informing the patient’s condition, such as body temperature, blood pressure, and disease biomarker concentrations, in a normal-life setting and beyond the confines of medical facilities. To enable such applications, it is crucially important for the sensors to be mechanically flexible so that they can conform to the underlying human skin or tissue surface.[3,4] As such, the sensors will be capable of consistently and reliably measuring changes of physiological parameters and biomarker concentrations throughout the movement and deformation of the human skin or tissue surface.

Traditionally, physiological and biochemical sensors are based on rigid substrates that do not conform to underlying surfaces.[5,6] Recently, intensive research efforts have been devoted to biosensors that are mechanically flexible for wearable applications.[7,8] Such sensors are fabricated on sheets of polymers, such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS),[9] polyester (PET),[10] and polyethylene naphtha-late (PEN).[11] These polymer sheets are 100 μm or more in thickness, and serve as supporting sensor substrates. As such, the sensors can mechanically conform to surfaces of modest curvature (with radii ranging from 4 to 40 mm),[12–14] but would fail when subjected to larger deformations. These limitations can be overcome by sensors that are fabricated on considerably thinner substrates (with thicknesses well below 100 μm) that, when combined with equally flexible functional components, can sustain large deformations involved in physiological and biochemical measurements on human skin or tissue surfaces.[15,16] Such thin substrates have been used in organic field-effect tran-sistors,[17,18] which unfortunately have limited sensitivity and practical utility because of organic conducting materials' generally low carrier mobility (≈1–40 cm2 V−1 s−1)[19,20] and poor stability in liquid media.[21]

This paper presents an ultraflexible and stretchable affinity nanosensor that aims to enable the consistent and reliable detection of biomarkers in liquid media on human skin or tissue surfaces that undergo large mechanical deformations. The nanosensor is a graphene-based field-effect transistor (GFET) that uses monolayer graphene as the conducting channel and is functionalized with aptamer molecules specific to the biomarker to be measured. Binding of the aptamer with the biomarker induces a change in the carrier concentration of graphene, which is measured via the current of the FET to determine the biomarker concentration. Based on a micrometer-thin film of the biocompatible polymer Mylar as the supporting substrate,[22] the nanosensor is mechanically ultraflexible and stretchable, being capable of conforming to underlying surfaces (e.g., those of human tissue or skin) that undergo large bending, torsional, and tensile deformations. This is demonstrated by the device’s capability to be rolled on cylindrical surfaces with radii down to 40 μm, twisted by angles ranging from −180° to 180°, or stretched by up to 125%. In the face of these mechanical deformations that are tens of times larger than those reported for existing flexible devices,[23–25] the sensor is also highly durable by withstanding cyclic rolling, twisting, or stretching deformations of the underlying surface (up to 500 cycles) without mechanical failure, maintaining consistent electrical properties with a carrier mobility of up to 3544 ± 231 cm2 V-1 s−1, and performing detection of biomarkers (e.g., TNF-α, an inflammatory cytokine) with consistently high selectivity and low limit of detection (LOD) (down to 5 × 10–12 M TNF-α) for With these capabilities, the nanosensor can be potentially used in wearable or implantable systems for human health monitoring and clinical diagnostics.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Device Design and Fabrication

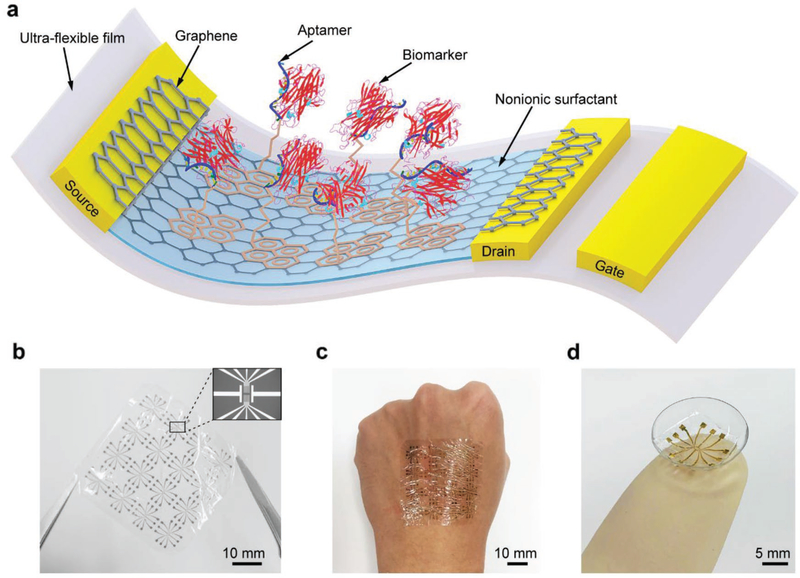

The GFET nanosensor consists of a graphene conducting channel on a thin Mylar film (2.5 μm), which can conform to the underlying surface undergoing large deformations (Figure 1a). The graphene is modified with aptamer molecules that can specifically recognize and bind to a given biomarker. During operation, the electrical double layer at the interface of the graphene and electrolytes serves as the gate dielectric. A drain–source bias voltage generates a current through the graphene channel. A change in this drain–source current results from the aptamer-biomarker binding and is measured to determine the biomarker concentration. The nanosensor was observed to be highly flexible and conformable either in free-standing form (Figure 1b), or when mounted on a practically relevant solid support, such as a human hand (Figure 1c) or contact lens (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

The ultraflexible GFET nanosensor device. a) Schematic of the ultraflexible aptameric GFET nanosensor. b) Photograph of the free-standing nanosensor. Inset is an image of the source, drain, and gate electrodes. c,d) Photographs of the ultra-flexible sensor conformably mounted on the c) human hand and d) contact lens.

To fabricate the nanosensor, the Mylar film was first bonded onto a glass slide (as a handling substrate) using polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) as an adhesive layer (Figure 2a). PVP is a water-soluble polymer, whose dissolution in water allows the sensor to be easily and completely peeled off the glass slide. Subsequently, 50 nm of Cr/Au electrodes were patterned onto the substrate using a fabrication process involving photolithography, e-beam evaporation, and lift-off. A monolayer graphene sheet grown by chemical vapor deposition was then transferred onto the electrodes as the conducting channel. Finally, the nanosensor was released from the glass slide in water. More details of the fabrication process are described in the Supporting Information. An image of the fabricated nanosensor with integrated electrodes is shown in Figure 2b, with a scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the graphene conducting channel shown in the inset. The total thickness and area density of the nanosensor were ≈2.5 μm and 12.5 gm−2, respectively (Figure S1, Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

Biochemical functionalization of the GFET nanosensor. a) Illustration of the fabrication and functionalization process of the nanosensor. b) Image of the nanosensor with source, drain, and on-chip gate electrodes. Inset is the SEM image of the graphene conducting channel on electrodes. c) Raman spectra of the graphene before and after PASE treatment. d) Transfer characteristic curves of the graphene before and after PASE, aptamer, and Tween 20 modification.

The detection of the biomarker is achieved by the aptamer, a synthetic single-stranded DNA VR11,[26] when interacting with the target biomarker.1-Pyrenebutanoic acid succinimidyl ester (PASE) was immobilized on the graphene surface through π–π stacking, which was used as a linker to anchor the aptamer. Ethanolamine and Tween 20 were then used to modify the graphene to quench the unreacted PASE and passivate the uncoated graphene area (see Figure S2 in the Supporting Information for the detailed graphene functionalization process).

The modification of graphene with PASE was verified using Raman spectra (Figure 2c). The split of G-band was observed after modification, which confirmed the coupling of graphene and the pyrene groups on PASE. The successful functionalization of the nanosensor was verified by analyzing the measured transfer characteristic curves, i.e., plots of the drain-source current (Ids) versus the gate voltage (Vg) (Figure 2d). The Dirac point (VDirac), the value of Vg at which Ids reaches its minimum, was observed to increase from 61 to 130 mV after PASE immobilization, indicating PASE-induced p-type doping in the graphene. Upon attachment of the aptamer, which induced n-type doping in the graphene, VDirac then decreased to 110 mV. Tween 20, a chemically stable and nontoxic polymer, was used to block the portion of the graphene surface that had not been modified with aptamer molecules to reduce nonspecific binding.[27] After modification of the graphene by Tween 20, VDirac shifted Dirac from 110 to ≈58 mV due to the induced n-type doping. The effectiveness of Tween 20 for blocking nonspecific binding was verified by drastically reducing the change of VDirac from 20 mV (when there was no Tween 20 coating) to only 4 mV (Figure S3, Supporting Information). Thus, Tween 20 could effectively passivate the uncoated area of the graphene and significantly suppress nonspecific binding.

2.2. Device Testing under Deformations

The electrical properties and biomarker responses of the GFET nanosensor in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature were investigated. All testing was repeated on five devices of identical design, from which the means and standard errors (as error bars in figures) were obtained and reported. To characterize the nanosensor’s electrical properties, transfer characteristic curves (i.e., the drain–source current Ids as a function of the gate voltage Vg) were measured, and used to determine the carrier mobility and transconductance of the graphene as follows.

The transfer characteristic curve is theoretically represented by[28]

| (1) |

where μ is the carrier mobility, Vds the drain–source bias voltage and Vth the threshold voltage (i.e., the minimum gate voltage to create a conducting path between the source and drain electrodes), with W and L the width and length of the graphene conducting channel. In addition, the total gate capacitance per unit graphene channel area (Ctot) consists of the effective capacitance arising from the electrical double layer at the liquid–graphene interface (CEDL)[29] and the quantum capacitance of graphene (CQ)[30] (see Supporting Information for details).

The transconductance, denoted gm, is the slope of the transfer characteristic curve

| (2) |

This parameter can be used to evaluate the overall sensitivity of the GFET nanosensor: a larger value of gm means that the GFET exhibits a larger conductance change in response to a unit charge excitation. There are two maximum transconductance values located on the left side (hole branch, denoted ) and right side (electron branch, denoted ) of the transfer characteristic curve, respectively, which are attributed to the ambipolar transport property of the graphene.

From a measured transfer characteristic curve, evaluation of its slope allows the determination of the transconductance. Then, the carrier mobility μ can be calculated from the average of the maximum hole- and electron-branch transconductance values using Equation (2).

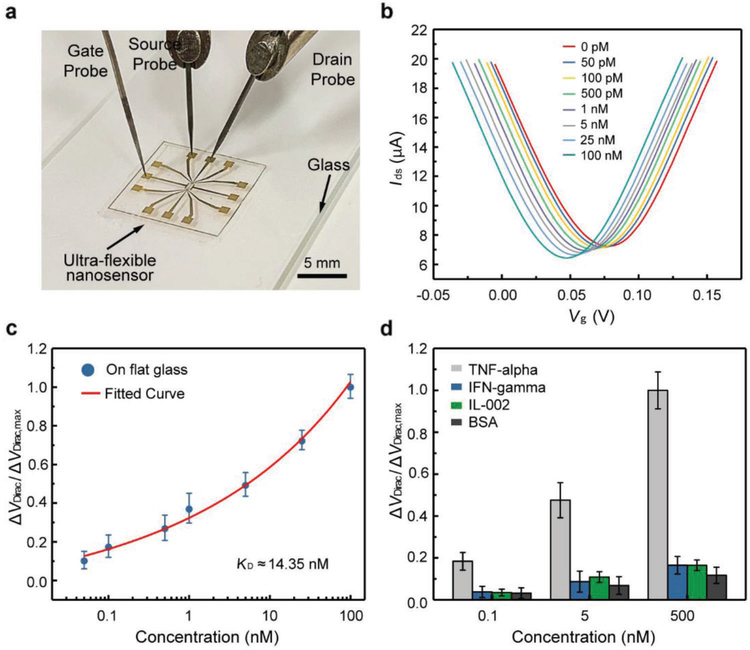

The nanosensor was first tested on a flat surface (Figure 3a), the results from which were used as a basis of comparison for assessing the device’s characteristics under large deformations. In the tests, the gate voltage Vg was varied from −0.1 to 0.2 V while the drain–source voltage Vds was fixed at 0.04 V. The transfer characteristic curves were measured (shown in the Supporting Information), from which the maximum transconductance was calculated to be μS on the hole branch and μS on the electron branch. From these transconductance values,the carrier mobility of the nanosensor was calculated to be 3380 ± 198 cm2 V−1 s−1.

Figure 3.

Biomarker detection using the GFET nanosensor. a) Photograph of the nanosensor placed on a glass slide for biomarker detection. b) Transfer characteristic curves measured when the nanosensor was exposed to TNF-α solution with different concentrations. c) Voltage shift as a function of the TNF-α concentration. The fitted curve is a least-squares fit to the Hill-Langmuir binding model. d) The normalized Dirac point shift showing the response of then a nosensor to different concentrations(0.1,5, and 500×10−9M) of TNF-α and the control proteins (IFN-γ, IL-002, and BSA).

The carrier mobility and transconductance obtained above were significantly higher compared with those fabricated on SiO2.[31,32] Graphene sensors fabricated on SiO2 are suscep-tible to strong charge carrier scattering due to low-energy surface phonons, and also the massive trap density in SiO2 causes the poor mobility.[33] In contrast, by use of Mylar film as the nanosensor substrate, the graphene effectively suspended between roughness spot over the Mylar surface, thereby mitigating the trapped charge scattering.[34] This enhanced the carrier mobility, and thus increased the sensitivity of the nanosensor.

The nanosensor’s capability for biomarker detection was tested using TNF-α, an inflammatory cytokine closely related to fever, inflammation and inhibition of tumorigenesis. TNF-α solution was filled in a PDMS well mounted on the device for liquid handling. As the TNF-α concentration increased from 50 × 10−12 M to 100 × 10−9 M, the Dirac point VDirac decreased by 31 mV from 79 to 48 mV (Figure 3b), indicating that the binding between the aptamer and TNF-α induced n-type doping to the graphene. This was expected from the nanosensor’s transduction mechanism: the guanine-rich aptamer VR11 on the graphene bound with the biomarker (i.e.,TNF-α), and switched to a stable and compact G-quadruplex conforma-tion.[35] As such, the electron-rich aptamer together with the negatively charged TNF-α was brought closer to the graphene surface, which enabled electrons from electron-rich aptamer and TNF-α to transfer to the graphene.[36,37] This resulted in a change of the carrier concentration in the graphene, which was manifested as a change in the measured drain-source corrent.

To investigate the binding affinity between VR11 and TNF-α protein, the equilibrium dissociation constant, denoted KD, was investigated. The shift of Dirac point VDirac' denoted ΔVDirac = VDirac − VDirac,0 (VDirac,0 is the Dirac point corresponding to the PBS), was plotted as a function of TNF-α concentrations (Figure 3c). The effect of device-to-device variations on the sensing signals was addressed by using the normalized Dirac point shift defined by , where ΔVDirac,max = VDirac,max − VDirac,0 with VDirac,max the Dirac point corresponding to the maximum TNF-α concentration tested. The normalized data were fitted to the Hill–Langmuir binary binding model to determine the affinity between the aptamer and TNF-α (see Supporting Information for details).[5] Based on the fitted curve, KD was calculated to be 14.35 × 10−9 M, which is consistent with values reported in the literature (ranging from 7 to 30 × 10−9 M).[14,26] Based on the one sigma rule, the LOD was estimated to be 5 × 10−12 M. This compared favorably with the existing methods of TNF-α detection.[38,39]

To study the specificity of the nanosensor, IFN-γ and IL-002, two other inflammatory cytokines, as well as bovine serum albumin (BSA), were used as control proteins. The nanosensor was exposed to these control proteins at different concentrations under the same measurement condition with TNF-α. The normalized Dirac point shift for TNF-α was about five times larger than those for the control proteins at the same concentration (Figure 3d), indicating that the GFET nanosensor was specific to the target biomarker.

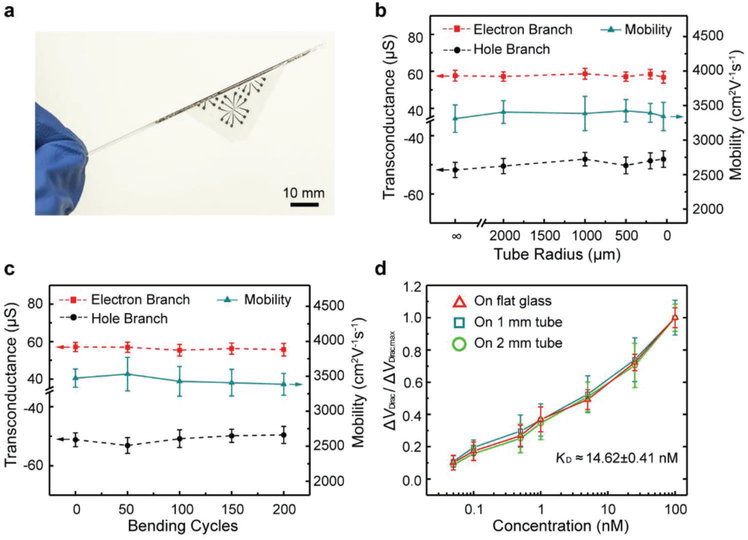

The nanosensor was tested when subjected to large-magnitude bending deformations (Figure 4a). In mechanical integrity testing, the device was rolled onto tubes of radius ranging from 2000 to 40 μm. In addition, to evaluate the device’s durability, such testing was repeated through 200 cycles on a tube of radius 500 μm. No visible mechanical damage was observed. This was due to the small strain in the nanosensor despite large deformations of the underlying surface. That is, when the thickness of the nanosensor (h) was much smaller than the radius of curvature of bending (r), the maximum strain in the sensor, given by ε = h/2r, was small. For example, ε ≈ 5 × 10−4 when r = 2 mm, which, more than 100 times smaller than that found in existing flexible sensors,[23,24] was negligibly small compared to the failure strain of graphene (12%) and gold electrodes (≈22%).[40,41] Thus, the nanosensor was capable of sustaining large-magnitude bending deformations without mechanical damage or failure.

Figure 4.

Bending tests of the GFET nanosensor. a) The nanosensor is wrapped around a glass tube with a radius of 0.4 mm. b) Transconductance and carrier mobility of the sensor on tubes with different radii. c) Transconductance and carrier mobility of the nanosensor bent with a radius of ≈500 μm after 0 to 200 bending cycles. d) Detection of TNF-α at a concentration ranging from 0.05 to 100 × 10−9 M on tubes with different radii.

We first measured the device’s electrical properties under large bending deformations (Figure 4b). As the tube radius varied from 2 mm to 40 μm, the change in the device’s transconductance was very small. The hole branch transconductance, varying between −50.5 and −47.0 μS, was within 7% of −50.4 μS (flat surface). The electron branch transconductance, determined to be between 56.2 and 58.5 μS, was within 2% of 57.3 μS (flat surface). From the transconductance, the device’s carrier mobility was determined to be within 2% of the value obtained on a flat surface (3380 cm2 V−1 s−1), changing only from 3342 to 3425 cm2 V−1 s−1 (See Figure S4 in the Supporting Information for transfer characteristic curves and transconductance profiles). The highly consistency in electrical properties during the large bending deformations was attributable to the small strains in the nanosensor.

In the durability tests, the electrical properties were also no appreciable change observed from cyclic bending tests (Figure 4c). For example, the device was bent with a radius of 500 μm through 200 cycles. The transconductance on the hole branch, lying in a narrow range between −53.1 and −49.3 μS, was within 5% of −50.4 μS (flat surface), while on the electron branch, it varied between 55.4 and 59.6 μS, within 4% of 57.3 μS (flat surface). The device’s carrier mobility was within 5% of the value obtained on a flat surface (3380 cm2 V−1 s−1), changing only from 3355 to 3531 cm2 V−1 s−1. The electrical properties of the nanosensor remained consistent during the cyclic large magnitude bending deformations.

The nanosensor, rolled on tubes of radii 1 and 2 mm, respectively, was tested on the detection of TNF-α (Figure 4d). The sensor response was highly consistent with that tested on flat surfaces (above), with deviations less than 5% at any given TNF-α concentration. As the TNF-α concentration increased from 50 × 10−12 M to 100 × 10−9 M, the Dirac point VDirac' similar to the case of the device on a flat surface, shifted consistently from the value measured for pure buffer. The maximum VDirac shift measured (occuring at 100 × 10−9 M TNF-α concentration) was respectively 28.6 (on 1 mm tube) and 30.8 mV (on 2 mm tube), whose deviations from the maximum VDirac shift on a flat surface (31 mV) were less than 8%. The equilibrium dissociation constant KD was estimated to be 15.01 × 10−9 M at 1-mm tube radius and 14.23 × 10−9 M at 2-mm tube radius, differing from the KD value on a flat surface (14.35 × 10−9 M) Only by 4% or less. Thus, the response of the nanosensor in biomaker detection remained highly consistent throughout the bending tests.

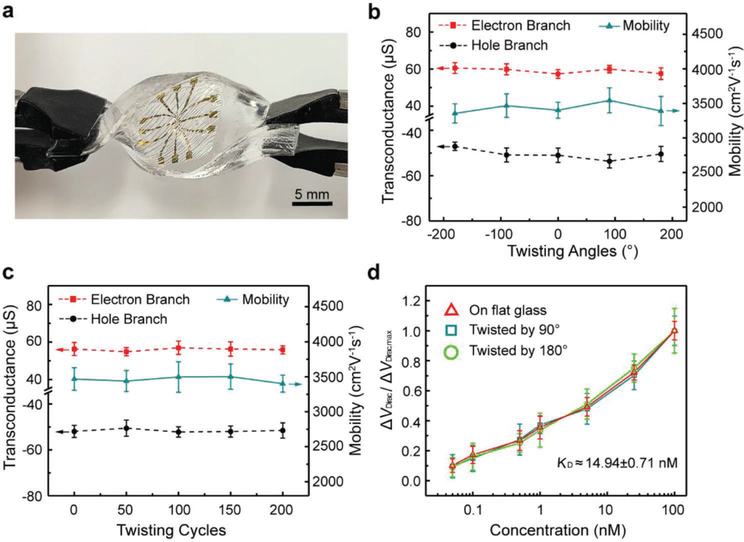

The nanosensor was next tested when subjected to large-magnitude twisting deformations (Figure 5a). The device was mounted on a rectangular block-shaped PDMS support, the elastic modulus of which is comparable with the human tissue, between 0.42 and 0.85 MPa in the torsion tests.[42,43] As the support was twisted at an angle ranging from −180° to +180°, and specially twisted from 0 to +180° through 200 cycles, the device conformed to the PDMS surface without any visible mechanical damage. This was because the area of the nanosensor occupied only an insignificantly small area of the underling surface (e.g., PDMS or skin), and therefore experienced a negligible amount of strain despite the large twisting deformations.

Figure 5.

Twisting tests of the GFET nanosensor. a) The nanosensor mounted on a PDMS substrate for twisting tests. b) Transconductance and carrier mobility of the nanosensor at different twisting angles. c) Transconductance and carrier mobility of the nanosensor after 0 to 200 cycles at a twisting angle of 180°. d) Detection of TNF-α at concentrations ranging from 0.05 to 100 × 10−9 M at different twisting angles.

There were no significant changes in the electrical properties of the device as the twisting angle ranged from −180° to +180° (Figure 5b). The hole branch transconductance, varying between −53.6 and −47.3 μS, was within 7% of −50.4 μS (flat surface). The electron branch transconductance was determined to be within 3% of the value obtained on a flat surface (57.3 μS), changing only from 57.2 to 60.6 μS. The carrier mobility, changing between 3354 to 3544 cm2 V−1 s−1, was within 5% of 3380 cm2 V−1 s−1 (flat surface) (see Figure S5 in the Supporting Information for transfer characteristic curves and transconductance profiles). The device was also tested under large numbers of twisting cycles to assess their durability (Figure 5c). As the device was twisted from 0 to +180° through 200 cycles, the hole branch transconductance, varying in the range of −50.6 to −52.2 μS, was within 4% of −50.4 μS (flat surface). The electron branch transconductance, between 54.8 and 57.6 μS, was within 4% of 57.3 μS (flat surface). The device’s carrier mobility was within 4% of the value obtained on a flat surface (3380 cm2 V−1 s−1), changing only from 3332 to 3501 cm2 V−1 s−1. The electrical properties of the nanosensor remained consistent under the large twisting deformations.

The device, twisted by 90° and 180°, respectively, was then tested for capability of TNF-α detection (Figure 5d). We observed that the sensor response was consistent with the response tested on flat surface. As the TNF-α concentration increased from 50 × 10−12 M to 100 × 10−9 M, the maximum Dirac point shift was respectively 29.9 (twisted by 90°) and 28.8 mV (twisted by 180°), and the deviations from the value on flat surface(31 mV was less than 7%. The equilibrium dissocia- tion constant KD was estimated to be 14.25 and 15.64 × 10−9 M at 90° and 180° twisting angle, respectively, differing from the KD value on flat surface (14.35 × 10−9 M) by 8% or less. Again, the response of the device to TNF-α was highly consistent and reliable throughout the twisting tests due to the small strains in the nanosensor.

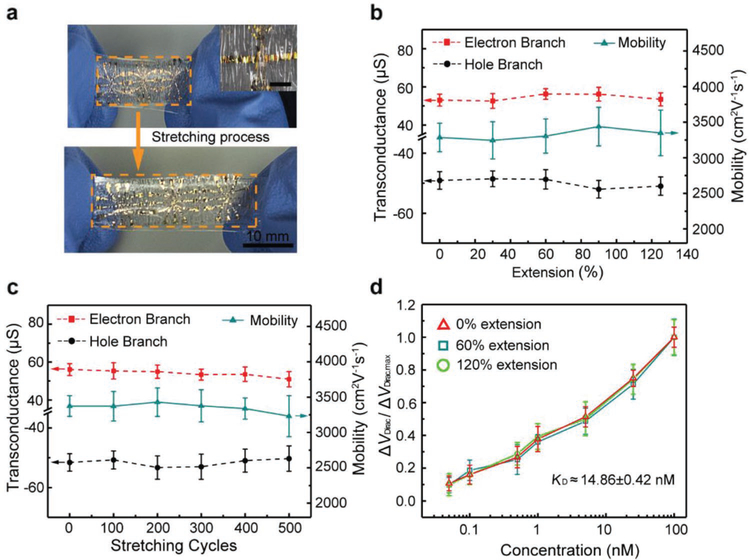

The nanosensor was also tested under large-magnitude stretching deformations. In general, the stretchability of a device is limited by the failure strain of its material layers (e.g., 12% for graphene). To overcome this limitation, the nanosensor was mounted on a pre-stretched sheet of the styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) elastomer, using stretchable double-sided adhesive tape (See Figure S6 for details in the Supporting Information). When the SEBS sheet was allowed to relax, corrugations formed in the Mylar film. This allowed the nanosensor-SEBS assembly to be stretchable in the direction of the initial undeformed plane of the SEBS sheet.[44] No mechanical damage was observed at the corrugations. The minimum radius of curvature of the corrugations were estimated, using a previous reported method,[45] to be approximately tens of micrometers, corresponding to a maximum strain of 4% in the nanosensor. This small strain was again responsible for the device’s ability to sustain the formation of corrugations with no mechanical damage. The nanosensor-SEBS assembly was then stretched by extensions of up to 125% and was observed to maintain its mechanical integrity (Figure 6a and the associated inset). The assembly was also shown to be durable and sustained no visible mechanical damage through 500 cycles of cyclic extension at 60%. This high level of stretchability was enabled by the existence of corrugations; the stretching of the SEBS resulted in the flattening of the corrugations with, in fact, a decrease in the magnitude of strain in the nanosensor, including the graphene, the chromium/gold electrodes and the Mylar substrate.

Figure 6.

Stretching tests of the GFET nanosensor. a) Photograph of the stretchable nanosensor extended from 0% (top) to 125% (bottom). Inset is the image of the corrugated structure of the sensor at 0% extension. Scale bar is 100 μm b) Transconductance and carrier mobility of device at the extension ranging from 0 to 125%. c) Transconductance and carrier mobility of the sensor after 0 to 500 tensile cycles at 60% extension. d) Detection of TNF-α protein at different extensions.

The device was tested under different stretching deformations to evaluate its electrical properties (Figure 6b). As the extension of the device varied from 0% to 125%, the transconductance was changed by less than 8% of the values on flat surface, from −48.5 to −51.9 μS on the hole branch, and 52.6 to 57.3 μS on the electron branch, respectively. The carrier mobility, changing from 3243 to 3491 cm2 V−1 s−1, was within 4% of 3380 cm2 V−1 s−1 (flat surface) (see Figure S7 in the Supporting Information for transfer characteristic curves and transconductance profiles). The devices were also tested under large numbers of stretching cycles (Figure 6c). The devices were stretching at 60% during 500 stretching cycles with no significant electrical properties change. The hole branch transconductance, varying between −53.3 and −50.2 μS, was within 6% of −50.4 μS (flat surface). The electron branch transconductance, between 53.3 and 57.3 μS, was within 7% of 57.3 μS (flat surface). The carrier mobility was within 5% of 3380 cm2 V−1 s−1 (flat surface), changing only from 3230 to 3429 cm2 V−1 s−1. The high consistency of the device could be explained by the small strain during the large-magnitude stretching deformations

Moreover, the devices, extended to 60% and 120%, were tested on the detection of TNF-α at concentrations from 50 χ 10−12 M to 100 × 10−9 M (Figure 6d). The sensing response holds a high level of consistency, with deviations less than 3% at any given TNF-α concentration. The maximum Dirac point shift was 28.4 (60% extension) and 30.3 mV (120% extension), whose variation from the maximum shift on a flat surface (31 mV) was less than 8%. The dissociation constant KD was calculated to be 15.08 × 10−9 M at 60% extension and 14.65 × 10−9 M at 120% extension, differing from the value on flat surface (14.35 × 10−9 M) by only 5% or less. It was concluded that the response of the nanosensor afforded a high level of consistency in biomarker measurements during the stretching tests.

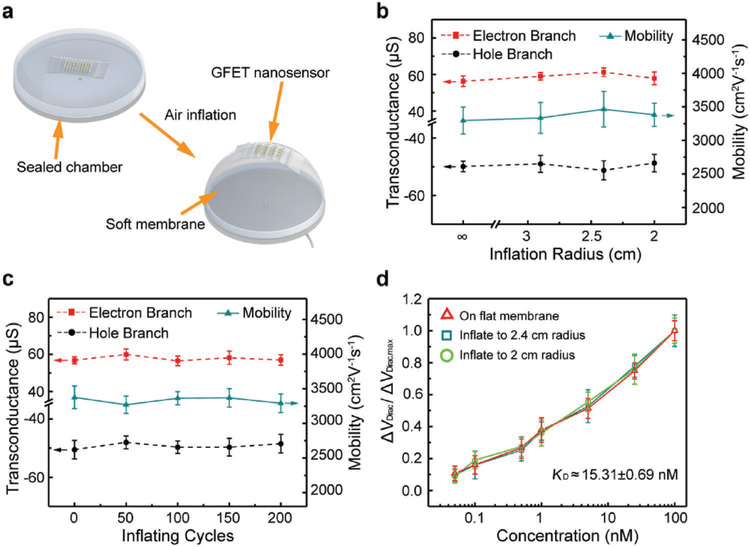

Finally, the nanosensor was tested on a soft, spherically deformable membrane. The soft and stretchable membrane could be inflated by compressed air to the shape of approximately a spherical cap of a certain radius (called the inflation radius) in a controlled manner. The membrane deflection induced a combination of large-magnitude stretching and biaxial bending of the nanosensor, serving as an example mimicking large, combined-mode deformations of wearable electronics on human body or tissues (Figure 7a). The device was tested on a membrane that was deflected up to a maximum inflation radius of 2.9, 2.4, and 2 cm, respectively; additionally, the device was also tested on a cyclically deflected membrane at a maximum deflection radius of 2.4 cm through 200 cycles. In all of these tests, the device incurred no visible mechanical damage, and was hence shown to possess a high level of mechanical integrity and durability.

Figure 7.

Characterization of the GFET nanosensor on a soft membrane. a) Schematic of the inflation process of the membrane with the nanosensor placed on it. b) Transconductance and carrier mobility of the GFET nanosensor at different inflation radii. c) Transconductance and carrier mobility of the sensor after 0 to 200 inflating cycles at a inflation radious of 2.4 cm. d) measurements pf TNF-α protein with concentration ranging from 0.05 to 100 × 10−9 M at different inflation radii.

The device was mounted on the membrane with different inflation radii to evaluate their electrical properties (Figure 7b). As the inflation radius varied from 2.9 to 2 cm, the hole branch transconductance, varying between −51.2 and −48.7 μS, was within 4% of −50.4 μS (flat surface). The electron branch transconductance, determined to be between 56.3 and 61.2 μS, was within 7% of 57.3 μS (flat surface). The carrier mobility was determined to be within 3% of the value obtained on a flat surface (3380 cm2 V−1 s−1), changing from 3295 to 3464 cm2 V−1 s−1. The devices were also tested under large num bers of inflating cycles to investigate their durability (Figure 7c). Each device was mounted on a membrane of ≈2.4 cm inflation radius through 200 cycles of inflation. The hole branch transconductance, lying in a narrow range between −50.4 and −48.1 μS, was within 5% of −50.4 μS (flat surface). The electron branch transconductance, between 56.8 and 60.0 μS, was within 5% of 57.3 μS (flat surface). The device’s carrier mobility was within 3% of the value obtained on a flat surface (3380 cm2 V−1 s−1), changing only from 3269 to 3391 cm2 V−1 s−1. Thus, the device’s electrical properties were highly consistent, due to the small strain, in the presence of combined large deformations.

The device was tested for the detection of TNF-α at a concentration from 50 × 10−12 M to 100 × 10−9 M at 2.4 and 2 mm inflation radii, respectively (Figure 7d). The sensor response was consistent with that tested on flat surface, with variation less than 2% at the same concentration. The maximum Dirac point shift was respectively 29.2 (2.4 cm inflation radius) and 28.8 mV (2 cm inflation radius), and the variation was less than 7% from the shift on flat surface (31 mV). The dissociation constant KD was estimated to be 15.51 × 10−9 M at 2.4 cm inflation radius and 15.13 × 10−9 M at 2 cm inflation radius, which were deviated by less than 8% from KD (14.35 × 10−9 M) on flat surface. This showed that the response of the nanosensor in biomarker detection was highly consistent, which was again attributed to the small strain in the nanosensor throughout the large deformations.

The results above showed that the electrical properties and sensing characteristics of the nanosensor remained to be highly consistent and reliable throughout large-magnitude deformations. Compared to existing flexible devices, the nanosensor also possessed higher mechanical flexibility, carrier mobility and transconductance (Table 1). This highly desirable behavior of the nanosensor could be explained by two attributes of the device. The first attribute was the ductility of the materials of which the nanosensor was fabricated. For example, monolayer graphene has a high failure strain (≈12%)[46,47] due to the arrangement and bond formation of carbon atoms, in contrast to the more commonly used materials such as indium tin oxide (failure strain <1%).[48] The second attribute was the small strain in the nanosensor. The thin functional (monolayer graphene at ≈0.34 nm and chromium/gold at 3/47 nm thicknesses) and substrate (Mylar at 2.5 μm thickness) materials allowed the nanosensor to experience strains that were small in magnitude (4% or considerably less, well below the failure strain levels of the materials) under large deformations. In comparison, existing flexible nanosensors are fabricated on thicker substrates (100 μm or more)[11,14] would incur much larger strain at radii of curvature that are considerable larger than those our device was capable of withstanding (e.g., ≈10% at 500 μm radius). As a result of these attributes, the nanosensor offers a high degree of mechanical flexibility and stretchability, and can hence be potentially deployed on human skin or tissue surfaces for consistent monitoring of health conditions.

Table 1.

Comparison of the nanosensor with existing mechanically flexible devices.

| Active layer | Substrate [thickness] | Deformations | Mobility [cm2 V−1 s−1] | Measurand [LOD] | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In2O3 nanoribbon | PET (5 μm) | Bending (3 mm radius) | 22 | Glucose (10 × 10−9 m) | [49] |

| Carbon nanotube, graphene oxide | PMMA (200 μm) | Bending (2 mm radius) | – | CA 125 (5 × 10−10 U mL−1) | [50] |

| Graphene oxide | PES | Bending (0.35% strain) | <0.13 | Strain (0.02%) | [51] |

| Graphene | PET | Bending (6.6 cm radius) | 400 (hole) 180 (electron) |

Glucose (3.3 × 10−3 m) | [52] |

| Graphene | PEN (150 μm) | Bending (2 mm radius) | – | Hg2+ (10 × 10−12 m) | [53] |

| Graphene | PET | Bending (8 mm radius) | 300 (hole) 230 (electron) |

– | [34] |

| Graphene | PEN (125 μm) | Bending (8.1 mm radius) | – | TNF-α (26 × 10−12 m) | [14] |

| Graphene | Mylar (2.5 μm) | Bending (40 μm radius) Twisting (±180°) Stretching (125%) |

3544 | TNF-α (5 × 10−12 m) | This work |

3. Conclusion

We developed an ultra-flexible and stretchable graphene field-effect transistor nanosensor that was functionalized with an aptamer. The aptamer bound specifically with the biomarker and induced a sensitive change in the carrier concentration of the graphene, which was measured to determine the biomarker concentration. The device was fabricated from ductile materials and was based on a thin Mylar substrate, which, with a thickness of only 2.5 μm, limits the strain in the device to a very low level under large deformations of the underlying surface. The device thus possesses a high level of mechanical flexibility and durability, as well as highly consistent electrical properties and biomarker responses. In experiments, the device was rolled on cylindrical surfaces with radii from 2 mm down to 40 μm, twisted by angles in a range of −180°–180°, and stretched by up to 125%. No visible mechanical damage was observed. The durability of the nanosensor was tested by cyclic rolling, twisting, and stretching deformations of the underlying surface (up to 500 cycles) that resulted in no visible mechanical damage. The electrical properties of the nanosensor were also highly consistent through the large deformations. The hole branch transconductance remained between −53.6 and −47.0 μS (within 7% of 50.4 μS, the value when the device was tested on a flat surface), and the electron branch transconductance remained between 52.6 and 61.2 μS (within 8% of 57.3 μS, the value with the device on a flat surface). The carrier mobility stayed between 3243 and 3544 cm2 V-1 s-1 (within 5% of 3380 cm2 V-1 s-1, the value from flat surface-based testing). Moreover, the nanosensor was capable of consistent and reliable detection of the TNF-α protein, with a LOD of 5 × 10−12 M throughout the large deformations of the underlying surface. These results demonstrate that the nanosensor is ultraflexible and stretchable, and can potentially be useful in wearable and implantable applications.

4. Experimental Section

Materials

Single-layer chemical vapor deposition (CVD) graphene was ordered from Graphenea Incorporation (Massachusetts, USA). Commercially available Mylar films (2.5 μm thickness of polyethylene terephthalate membranes) were purchased from Chemplex Industries (Florida, USA). PDMS (SYLGARD-184) was ordered from Dow Corning (Midland, MI). SEBS H1062 was supplied by Asahi Kasei elastomers. PASE, ethanolamine, Tween 20, PVP, BSA, and human Interleukin-002 (IL-002) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Phosphate buffered saline (1 × PBS, pH = 7.4) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Massachusetts, USA). TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma proteins were ordered from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). VR11 single-stranded DNA aptamer (5'-NH2- TGG TGG ATG GCG CAG TCG GCG ACA A −3') was synthesized and purified by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA).

Fabrication of Devices

The Mylar film was first placed on a glass slide, which has been pre-coated with two different concentration of PVP solutions. The release layer was spin-coated (500 rpm) using 0.1 g mL−1 PVP solution (average molecular weight 40 000), then the adhesive layer was spin-coated on the top at 1500 rpm using 0.05 g mL−1 PVP (average molecular weight 360 000). After the Mylar film was flatly and tightly bonded on the glass, the photoresist AZ1512 was spin-coated (4000 rpm) on the film using spinner (Spin coater WS-650–23B, Laurell). The stander process of exposure (SÜSS MA6 mask aligner, SÜSS Microtech) and developing (AZ 300 MIF Developer) was then applied to the photoresist. The source, drain and on-chip gate electrodes (3 nm Cr/47 nm Au) were deposited using Electron-beam evaporator (Orion-8E, AJA International). Finally, the photoresist could be released by rinsing in acetone for 4 h at room temperature, and the monolayer graphene was transferred to the source and drain electrodes. To release the nanosensor from the glass, the fabricated device was immersed in water, the release layer hence was rapidly dissolved and the ultra-flexible nanosensor was automatically released less than 30 min.

Biochemical Functionalization

As the schematic of the functionalization process shown in Figure S2 (Supporting Information), the nanosensor was first incubated for 5 h in 10 × 10−3 M PASE solution at room temperature and sequentially rinsed with dimethylformamide, ethanol and DI water to remove excess PASE. Then the nanosensor was immersed in PBS with 500 × 10−9 M aptamer overnight at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the device was incubated for 1 h in 100 × 10−3 M ethanolamine to block the excess carboxyl group on the graphene. Finally, the device was incubated in 0.01% Tween 20 solution for 2 h to block the uncoated area of the graphene.

Characterization

Images were obtained using Nikon Cclipse Inspection Microscope, and the SEM images were taken with FEI Nova NanoSEM 450. The Raman spectra were measured using Renishaw inVia micro-Raman, excitation laser wavelength 532 nm. The GFET nanosensor electrical properties and transfer curves were characterized by two Keiteley 2400 digital sourcemeters under control of LabVIEW programs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. 1DP3DK101085-01 and 1R33CA196470-01A1) and the National Science Foundation (Grant No. ECCS-1509760). Z.W. gratefully acknowledges a National Scholarship (award number 201706120141) from the China Scholarship Council.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

The ORCID identification number(s) for the author(s) of this article can be found under https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201905202.

Contributor Information

Ziran Wang, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027, USA; Department of Mechanical Engineering, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin 150001, China.

Zhuang Hao, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin 150001, China.

Shifeng Yu, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027, USA.

Carlos Gustavo De Moraes, Department of Ophthalmology, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032, USA.

Leejee H. Suh, Department of Ophthalmology, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032, USA

Xuezeng Zhao, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin 150001, China.

Qiao Lin, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027, USA.

References

- [1].Kim J, Campbell AS, de Ávila BE-F, Wang J, Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hao Z, Pan Y, Shao W, Lin Q, Zhao X, Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 134, 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cao X, Cao Y, Zhou C, ACS Nano 2016, 10, 199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wang S, Xu J, Wang W, Wang G-JN, Rastak R, Molina-Lopez F, Chung JW, Niu S, Feig VR, Lopez J, Nature 2018, 555, 83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ohno Y, Maehashi K, Matsumoto K, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 18012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Huang H, Zhu J-J, Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 25, 927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Choi BG, Park H, Park TJ, Yang MH, Kim JS, Jang S-Y, Heo NS, Lee SY, Kong J, Hong WH, ACS Nano 2010, 4, 2910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Xiao F, Li Y, Zan X, Liao K, Xu R, Duan H, Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 2487. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gong S, Schwalb W, Wang Y, Chen Y, Tang Y, Si J, Shirinzadeh B, Cheng W, Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pradhan D, Niroui F, Leung K, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2010, 2, 2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pavinatto FJ, Paschoal CW, Arias AC, Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 67, 553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yan X, Chen X, Tay B, Khor KA, Electrochem. Commun. 2007, 9, 1269. [Google Scholar]

- [13].He Q, Zeng Z, Yin Z, Li H, Wu S, Huang X, Zhang H, Small 2012, 8, 2994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hao Z, Wang Z, Li Y, Zhu Y, Wang X, De Moraes CG, Pan Y, Zhao X, Lin Q, Nanoscale 2018, 10, 21681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhang C, Fan Y, Li H, Li Y, Zhang L, Cao S, Kuang S, Zhao Y, Chen A, Zhu G, ACS Nano 2018, 12, 4803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Park S, Heo SW, Lee W, Inoue D, Jiang Z, Yu K, Jinno H, Hashizume D, Sekino M, Yokota T, Nature 2018, 561, 516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sirringhaus H, Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lee W, Kim D, Rivnay J, Matsuhisa N, Lonjaret T, Yokota T, Yawo H, Sekino M, Malliaras GG, Someya T, Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 9869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ren H, Cui N, Tang Q, Tong Y, Zhao X, Liu Y, Small 2018, 14, 1801020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kaltenbrunner M, Sekitani T, Reeder J, Yokota T, Kuribara K, Tokuhara T, Drack M, Schwödiauer R, Graz I, Bauer-Gogonea S, Nature 2013, 499, 458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Shao M, He Y, Hong K, Rouleau CM, Geohegan DB, Xiao K, Polym. Chem. 2013, 4, 5270. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Grayson AC, Voskerician G, Lynn A, Anderson JM, Cima MJ, Langer R, J. Biomater. Sci., Polym. Ed. 2004, 15, 1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Choi H, Choi JS, Kim JS, Choe JH, Chung KH, Shin JW, Kim JT, Youn DH, Kim KC, Lee JI, Small 2014, 10, 3685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kwon OS, Park SJ, Hong J-Y, Han A-R, Lee JS, Lee JS, Oh JH, Jang J, ACS Nano 2012, 6, 1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Liao C, Mak C, Zhang M, Chan HL, Yan F, Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Orava EW, Jarvik N, Shek YL, Sidhu SS, Gariépy J, ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chang H-K, Ishikawa FN, Zhang R, Datar R, Cote RJ, Thompson ME, Zhou C, ACS Nano 2011, 5, 9883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kim BJ, Jang H, Lee S-K, Hong BH, Ahn J-H, Cho JH, Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 3464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ohno Y, Maehashi K, Yamashiro Y, Matsumoto K, Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Xia J, Chen F, Li J, Tao N, Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wang S, Ang PK, Wang Z, Tang ALL, Thong JT, Loh KP, Nano Lett. 2009, 10, 92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sharma BK, Ahn J-H, Solid-State Electron. 2013, 89, 177. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Chen F, Xia J, Tao N, Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lu C-C, Lin Y-C, Yeh C-H, Huang J-C, Chiu P-W, ACS Nano 2012, 6, 4469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Williamson JR, Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1994, 23, 703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Dong X, Shi Y, Huang W, Chen P, Li LJ, Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Dong X, Fu D, Xu Y, Wei J, Shi Y, Chen P, Li L-J, J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 9891. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Say R, Diltemiz SE, Çelik S, Ersöz A, Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 275, 233. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Bahk YK, Kim HH, Park D-S, Chang S-C, Go JS, Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2011, 32, 4215. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lee C, Wei X, Kysar JW, Hone J, Science 2008, 321, 385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lacour SP, Wagner S, Huang Z, Suo Z, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 82, 2404. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Armani D, Liu C, Aluru N, in 12th IEEE Int. Conf. Micro. Electro Mech. Syst, Orlando, FL, USA, January 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Agache PG, Monneur C, Leveque JL, De Rigal J, Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1980, 269, 221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Khang D-Y, Jiang H, Huang Y, Rogers JA, Science 2006, 311, 208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Melzer M, Kaltenbrunner M, Makarov D, Karnaushenko D, Karnaushenko D, Sekitani T, Someya T, Schmidt OG, Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Choi D, Choi MY, Choi WM, Shin HJ, Park HK, Seo JS, Park J, Yoon SM, Chae SJ, Lee YH, Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Liu F, Ming P, Li J, Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 064120. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Cairns DR, Paine DC, Crawford GP, MRS Proc. 2001, 666, F3.24. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Liu Q, Liu Y, Wu F, Cao X, Li Z, Alharbi M, Abbas AN, Amer MR, Zhou C, ACS Nano 2018, 12, 1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Majd SM, Salimi A, Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1000, 273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Trung TQ, Tien NT, Kim D, Jang M, Yoon OJ, Lee NE, Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 117. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kwak YH, Choi DS, Kim YN, Kim H, Yoon DH, Ahn S-S, Yang J-W, Yang WS, Seo S, Biosens. Bioelectron. 2012, 37, 82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].An JH, Park SJ, Kwon OS, Bae J, Jang J, ACS Nano 2013, 7, 10563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.