Abstract

In this paper, we examine how the 2008–2009 drought in northern Tanzania contributed to and catalyzed the transformation of governance concerning the management of natural resources from traditional informal institutions among the Maasai to formal village-based institutions. Our central argument is that village governance in northern Tanzania represents a new, formal institution that is supplementing and in some important ways obviating traditional, informal institutions. Further, this replacement is central to what appears to be a transformation of the social-ecological system embracing the rangelands and pastoral/agropastoral people in northern Tanzania. In this paper, we document the basis for our claims concerning the institutional shift and discuss its implications for livelihoods and social relationships.

Keywords: institutions, Maasai, governance, transformation, drought

Introduction and Background

During 2008/2009 the rangelands of northern Tanzania and southern Kenya experienced a severe drought in which both the long and short rains failed. There was large-scale migration of people and cattle from the Tanzania/Kenya border southward in search of pasture and water, but despite this migration, border communities lost significant numbers of livestock. Meanwhile, in the Simanjiro plains in northern Tanzania, the drought was less severe and there was enough grass and water for livestock in communities east of Tarangire National Park. Tens of thousands of cattle were herded from the north toward and into Simanjiro villages. The influx of livestock overwhelmed the capacity of the natural resource base to support both the newcomers and residents. After the drought, a local leader in Simanjiro said: “What could we do – we could not refuse them, they were all Maasai, and when the grass was gone we had to migrate all together to where we could find pasture and water.” That comment reflected longstanding attitudes and practices. However, following the return of the migrants north to their home areas, many of the Simanjiro communities changed the rules governing access to local resources. For the first time, there was a shift away from traditional institutions that allowed Maasai outsiders access to resources, to village-based rules that restricted access based on land-use plans and village by-laws.

Drought is a common occurrence in the semi-arid rangelands of Africa and this drought, while severe, was not of historic dimensions in terms of lack of precipitation. Why, then, was this particular drought so transformative? Our research indicates that the answer entails the shift from informal ethnically-based traditional institutions that managed resource use to formalized village-based institutions, a process that began in 1967 and that continues to evolve. Understanding this process of institutional transformation is the subject of this paper.

Our central argument is that village governance in northern Tanzania represents a new, formal institution that is supplementing and in some important ways obviating traditional, informal institutions. Further, this replacement is central to what appears to be a transformation of the social-ecological system (SES) embracing the rangelands and pastoral/agro-pastoral people in northern Tanzania. In this paper, we document the basis for our claims concerning the institutional shift and discuss its implications for livelihoods and social relationships.

Our argument revolves around three intersecting realms of inquiry that are prominent in the literature on African rangelands: pastoralism and livelihood diversification; drought and resilience; and common property and institutional change. We begin with a brief review of recent understanding of these topics as they bear on the problem at hand.

Pastoralism and livelihood diversification

Rangelands cover more of the earth’s land surface than any other type of land (Reid et al. 2014). In Africa, rangelands cover about 40% of the land mass (Mwangi and Ostrom, 2009), and are home to approximately 30 million people who practice pastoralism or agro-pastoralism as their primary livelihood (Homewood (2008). Although East African pastoralists are often associated with what is referred to as “pure” pastoralism (an economy based exclusively on raising livestock), most pastoral peoples now have diversified economies. The most salient forms of diversification in recent decades have been the adoption of agriculture (O’Malley 2000, Homewood 2008, McCabe, Leslie and DeLuca 2010) and temporary labor migration out of the pastoral sector (May and McCabe 2004, Lesorogol 2008, McCabe et al. 2014, Smith 2012). Alienation of rangelands due to parks and protected areas has helped drive the need for pastoralists to diversify (Homewood and Brockington 1999, McCabe 2003, Igoe 2003, Goldman 2013). Also important is gradual impoverishment due to an increasing human population and fluctuating or declining livestock populations, along with the desire to be “modern” (McCabe, Leslie and DeLuca 2014). The consequences of livelihood diversification have included better nutrition for pastoral families (McCabe 2003, McCabe, Leslie and DeLuca 2010), but also land fragmentation and a decline in ecosystem services (Burnsilver et.al. 2008, Galvin 2009).

The role of institutional changes in driving livelihood diversification among pastoralists has not received much attention; neither has how diversification has contributed to institutional change. Exceptions to this include the work of Mwangi (2005) about the formation and dissolution of group ranches among Maasai in southern Kenya; of Ensminger (1996) on the shift from subsistence herding to commercial livestock keeping among Orma in eastern Kenya (1992), and of Lesorogol (2008) on the shift of property rights from common grazing to individual holdings among Samburu in central Kenya.

Common property and institutional change

There are a number of ways that institutions are conceptualized, but Yami et al. (2009:154) note that most definitions entail “structures, mechanisms and processes as well as rules and norms that govern human behavior.” They go on to define informal institutions as “systems of rules and decision-making procedures which have evolved from endogenous sociocultural codes and give rise to social practices, assign roles to participants and guide interactions among common pool resources users”; and formal institutions as “the rules that guide access, control and management of common pool resources, and which are backed up and enforced by the state” (Yami et.al 2009: 154). In this case we refer to the change from ethnic based norms to village-based policies, with the enforcement the responsibility of the village government. Both formal and informal institutions play important roles in common property regimes.

Although institutional change in East African pastoral societies has been under-studied, there is a large literature on common property regimes, and animal husbandry figures prominently in this literature. The most influential work relating to how successful common property resources are managed, and why they fail, stems from Elinor Ostrom (1990, 2003, 2009). Of particular importance to the case study presented here is the centrality of trust and reciprocity to successful management of a commons (Ostrom 1990, 2003).

One of the major arguments in the property rights literature is that privatization increases efficiency. Mwangi (2005) points out that the efficiency argument is based on the notion that private property encourages production by individuals and a more efficient use of resources, and that institutions will always evolve towards greater efficiency. She also points out that this argument is incomplete -- a fuller understanding of property rights must include politics, State interventions, and the distributional consequences of private property. Further, changes in property rights can be triggered by economic transitions, the relative scarcity of resources and new markets. For a more detailed discussion of this issue see Bromley (1989). For the case being discussed here it could be argued that providing a guaranteed access to grazing within village boundaries is the efficient management strategy, but Reid et al (2014) argue that restricted movement actually lowers livestock productivity, and the ability to access distant resources during times of stress is considered critical to the sustainability of many pastoral production systems and societies (McCabe 2004). For changes in property rights among Maasai women see Goldman et. al. 2016.

Recently, Bollig and Lesorogol (2016) edited an exploration of the idea of a “new commons.” They point out that the new commons are based on the view that natural resources should be commodified to the benefit of rural resource users and that they require a negotiation between the older forms of commons management and new forms. This is similar to the notion of a hybrid form of governance and Cleaver’s use of “institutional bricolage” in which new institutions are based on adapting and incorporating existing institutions (Cleaver et al 2013).

Drought and resilience

Wilhite (2000) argues that drought is the most complex but least understood of all natural hazards. Drought is often defined as a significant decrease in precipitation, but there is not universal agreement on a definition or on how to measure drought severity. Droughts differ fundamentally from many other disasters in that droughts develop slowly and it is often hard to determine exactly when they begin and end. The effects may last for years after the drought is over. Further, drought’s effects may be spread over a wide geographical area, some of which may not have been directly impacted by the drought itself.

The diverse and pervasive effects of drought lead directly to its central role in understanding the dynamics of social-ecological systems in arid and semi-arid regions, and consequently in understanding the adaptive capacity or resilience of communities in those regions. Resilience can be defined as “the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and still retain its basic structure and function” (Walker and Salt 2006), but in the context of social-ecological systems resilience means more than simply the persistence of ecological relationships or of social structure; it includes how aspects of social and political systems respond and adapt to shocks, and also reflects the adaptive capacity to respond to the opportunities and constraints that are created or enhanced by perturbations such as drought (Leslie and McCabe 2013:115, see also Folke 2006). Social-ecological systems are complex adaptive systems. As such, they often do not change in linear or predictable ways and fundamental relationships among the elements and processes that are central to the system can shift rapidly.

Defining the components of the social-ecological system of which our study communities are a part, and evaluating its resilience, is beyond the scope of this paper, However, we feel that the institutional changes that we discuss have profound implications for the future resilience of East African pastoral systems and communities. Similar to the argument for increased efficiency, it could be argued that by securing local grazing for local communities could enhance resilience, but most researchers of pastoral peoples feel that in arid and semi-arid areas where rainfall is temporally and spatially variable, mobility is one of the key elements in resilience, and that fragmentation of the rangeland reduces the overall resilience of the social-ecological system (Galvin 2009, Robinson and Berkes 2010, Leslie and McCabe 2013, and Quandt 2018).

Setting and People

The setting

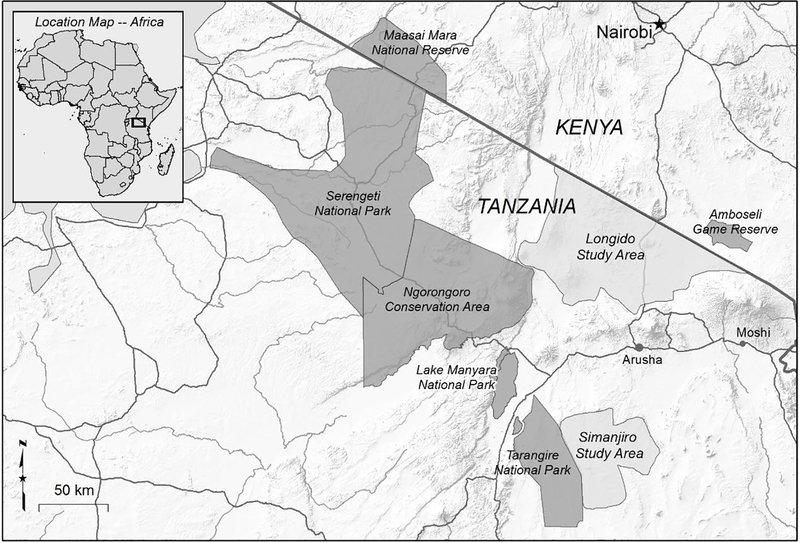

The study reported here is grounded in two areas in the rangelands of northern Tanzania - – Longido and Simanjiro -- located to the west of Mount Kilimanjaro and east of Lake Natron (see Figure 1). This landscape is famous for its network of parks and protected areas and the large populations of charismatic wildlife. The establishment of multiple parks -- Tarangire, Manyara, Serengeti, Kilimanjaro, and the Ngorongoro Conservation Area -- alienated important resources from the Maasai people, and restricted movements into what they traditionally considered drought reserves.

Figure 1:

Map of Northern Tanzania

The Simanjiro plains are part of the Maasai Steppe or the Tarangire-Manyara ecosystem. Vegetation consists of mixed woodlands and extensive grasslands. Rainfall averages between 575 to 650 mm per year but is unpredictable both spatially and temporally. The rangelands along the Kenya/Tanzania border area are drier than in Simanjiro, with rainfall averaging between 300 and 600 mm per year and the higher elevations receiving significantly more precipitation than the lowlands (Trench et al.2009). Due to the lack of rainfall, cultivation is less viable in Longido than in Simanjiro and people are even more dependent on livestock as their principle livelihood strategy. In both areas, drought is frequent and at times severe.

The people

Traditional Maasai culture, social organization, and livelihoods have been well described (e.g., Homewood and Rodgers 1991, O’Malley 2000, Hodgson, 2011, Mwangi 2005,). Here, we present a brief overview of those aspects of social organization that are especially relevant to the problem at hand. Maasai social organization is based on three interlinked institutions: territorial sections, age sets/grades, and marriage and family.

The largest territorial unit is the section or olosho in Maa. The communities in this study were all members of the Kisongo section of the Maasai. Within this territory grazing resources are available to all members of the section, but specific areas were set aside for dry season grazing while others were designated for wet season use. Particular areas or “localities” (inkutot) are managed by a group of elder men who decide on where livestock should be grazed and where cultivation will be allowed.

All Maasai men are members of a clan (olgilata), with the larger clans sub-divided into a number of smaller sub-clans. Each clan has a clan leader but most function on more circumscribed territorial areas, with local clan leaders. Important for the resilience of households, each clan functions as a mutual aid group. Livestock are redistributed to impoverished clan members following a crisis and clan members may collect funds to help other clan members facing particular challenges, such as hospital or school fees. In addition to acting as mutual aid groups, clans also manage many water rights. Small streams, springs, and occasionally dams may be “owned” by clans and the rights concerning who could use them were the responsibility of the clan.

All adult Maasai men are also members of a particular age set which forms part of the age grade system. Together as members of an age set, men pass through a series of age grades from boys (although “boys” is not generally considered to be one of the age grades), to warriors, junior elders, senior elders and retired elders. During the time that young men are in the warrior (Ilmurran) age grade they are circumcised and a leader is chosen by members of the elder age grade (often referred to as firestick elders). However, as Goldman points out in her forthcoming book there is a new category of traditional leaders that are affiliated with clans on a local level (Goldman forthcoming). This Ilaiguenani will serve as the age set leader throughout his life. Progression to the next age grade is triggered by the advancement of the warrior age grade to junior elder status, roughly every 10 to 14 years. Traditionally, age set leaders advised people on day to day affairs and looked out for their economic and social welfare. Especially important here is the influence of age set leaders in defining wet and dry season grazing areas and when these would be opened and closed. Further, members of an age set have rights and obligations to each other throughout the course of their lives.

These three institutions -- the age grade/age set system, the relationships among family and clan members, and the territorial organization -- are pillars of traditional Maasai social organization, all with roles in defining rights and obligations and in managing access to resources. As we will see, this traditional organization still functions but its importance has been eclipsed by formal village based institutions, at least with respect to land use and management.

The above description of Maasai social organization is in no way meant to suggest that Maasai society is locked into a historical past. Maasai society is changing rapidly, as is clear from our discussions below of the adoption of cultivation, out-migration to urban areas and engagement with the tanzanite gem business, which we present in the case study. For a more detailed discussion of what Maasai men and women view as important to their well-being today see Woodhouse and McCabe 2018).

Village governance

Village government consists of a village assembly that includes all individuals over the age of 18. Members of the village assembly elect a chairperson (mwenyekiti), secretary (kitibu), and treasurer while the village executive officer (mtendaji) is appointed by the District. Each village is divided into sub-villages (kitongoji, pl. vitongoji), each of which also has a chairperson, and secretary. The village council is the governing body of the village and consists of the chairperson, all sub-village chairpersons, and elected members that must include women. Within the village council a series of smaller committees are formed to deal with such legislative matters as finance, social services, security, forest protection, water management and development, etc. In many villages where the principal livelihood activity is raising livestock, a livestock committee is responsible for defining areas of wet and dry season grazing and sometimes for determining when dry season grazing areas are opened to village members. Following the 2008/2009 drought we witnessed some livestock committees, or newly formed committees, assigned the responsibility of evaluating the capacity of village resources to accommodate people and livestock that migrate onto village lands, and to suggest changes in village by-laws and land use plans based on the availability of pasture and water. It should be noted that in many cases pastoral oriented NGOs helped with the land use plans adopted by the villages.

The evolution of the village

It might be expected that once villages were formed they would rapidly take over the role formerly played by traditional institutions, but that was not the case. For decades after the formation of the villages, the government’s intended purposes of the village – as well as the village boundaries -- were largely ignored.

In 1967, Julius Nyerere delivered the now famous Arusha Declaration, in which he laid out his vision of a socialist agenda based on a system of rural villages with a central settlement area surrounded by farms and pastures. In these “Ujamaa” villages (Swahili word for family ties, which has come to mean socialist) (O’Malley 2000), there was little consideration of the existing land tenure systems, or of community rights based on custom or tradition (Shivji 1998). Nevertheless, this policy was implemented across more than 8,000 villages throughout Tanzania, a process often referred to as “villagization.” This process took place gradually across Tanzania between 1970 and 1974. According to Hyden (1980:104) “The number of ujamma villages rose from 1956 to 4484 between 1970 and 1971. The following year the figure exceeded 5500.” For a more detailed discussion of the villagization process in Tanzania see Hyden, 1980 and Schneider 2014)

It was not until 1974 that the ujamaa villages began to be established among Maasai communities in northern Tanzania. In Maasailand, this policy became known as “Operation Imparnati” based on the Maasai word for settlement or permanent dwelling (Ndagala, 1982). The reason for the delay in implementing the villagization process, according to Ndagala (1982) was that “The Maasai,..like other pastoralists were considered to be a problem by policy makers. Efforts were thus put on groups believed to be easier to deal with, the cultivators” (Ndagala, 1982:28).

The Maasai did not put up much resistance, as needed health dispensaries and primary schools were established. Also, according to O’Malley (2000), people were convinced that the basic idea of permanent settlement was incompatible with a pastoral livelihood and that after a while people would return to their former ways of managing resources and seasonal migrations. Although there were new “villages” with permanent buildings and the provision of some basic services, most Maasai did return to their traditional livelihoods. As late as 1991 Homewood and Rodgers, writing about Maasai living in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, stated:

“Overall these villages have had little lasting impact on patterns of settlement and seasonal movement, nor do they correspond with traditional economic or leadership structures. Individual families still live in widely dispersed bomas. Seasonal movements crosscut village boundaries and different families using the same village in the dry season may move to different wet season pastures, each associated with quite different alternative villages. Alongside the imposed village structure, the traditional systems of section, clan, age-set and boma still govern NCA Maasai access to resources and form the basis of their risk avoidance strategies and of their efficient livestock management in an unpredictable environment.” (Homewood and Rodgers, 1991:56).

Although people were moving with their livestock, and land and resources were being managed according to traditional institutions, important changes were occurring at both the household and village levels. We describe some of these changes below. The most critical changes include: adoption of cultivation, allocation of land to individuals, out migration of young men to find work as laborers or tanzanite gem traders, development of community managed resources, human population increase, and changes in government policies. These all interacted with one another and were the underlying conditions which precipitated the transformation of village governance following the 2008/09 drought.

The Case Study – The Village and Drought Response in Northern Tanzania

The land-use and livelihoods study

We have been conducting research on land use and livelihoods in Simanjiro District since 2004 and in Longido District since 2015, and have published on livelihood diversification – both the adoption of cultivation (McCabe et al. 2010) and temporary out-migration (McCabe et al. 2014) -- the impact of conservation (Baird et al. 2009, Davis 2011), and how people perceive human well-being (Woodhouse and McCabe 2018), among other topics. The information presented below concerning attitudes and actions on the part of village leadership and herd owners during and following the 2008–09 drought are based on 85 group interviews conducted in 2016: 59 among men (256 individuals); and 26 among women (129 individuals). These group interviews focused specifically on the responses to and consequences of the 2008/09 and 2016/17 droughts. Although both men and women were interviewed many of the women referred us to their husbands concerning issues related to livestock which migrated. How women specifically coped during the droughts will be the subject of subsequent publications. These interviews were supplemented by related information from an ongoing longitudinal livelihood survey we have been conducting in Simanjiro for nearly 15 years. The longitudinal research that we have been conducting concerned livelihood diversification, included cultivation and out-migration, and challenges of being located close to a national park. The topic of drought often came up during this research.

Cultivation

Cultivation among the Maasai in most parts of northern Tanzania began in the early 1980s, but there was significant variation across villages. For the most part, cultivation began with small gardens (less than one acre) and later expanded into farms (more than one acre). The preferred crops were maize and beans, although some people experimented with crops such as sunflowers or sesame. Most of the early adopters of cultivation learned by observing non-Maasai (WaArusha, WaMeru and Tanzanians of East Indian descent). Unlike some other pastoral groups (e.g., Turkana) Maasai had traditionally incorporated grain into their diet, obtaining it through trade with local cultivators or by purchase following sale of livestock. Maasai were well known for their historical aversion to engaging in agriculture themselves.

The motivations for cultivating have changed over time. Our research showed that by the first decade of the 21st century most Maasai families in Tanzania were cultivating. Poor people did so out of need for food, while wealthier people were cultivating so that they did not have to sell livestock to obtain cash for grain or other purposes (McCabe et al. 2010). Cultivation in Simanjiro has been qualitatively different from other areas, with increasing numbers of large farms being plowed by tractors or ox plows. Yields are highly variable, but now cultivation is considered part of being a modern Tanzanian, and despite the concerns of conservationists1 is unlikely to decrease, except in those areas where yields are consistently poor.

Land allocation

Village land began to be allocated to individual household heads in the study areas as early as 1977 but especially in the 1980s and into the 1990s. Unlike privatization in Kenya, when a parcel of land is allocated in Tanzania the central government retains rights to the land. Individuals are technically not allowed to sell land but have use rights for various periods of time.

Following village formation in the late 1970s a few individuals, including influential Maasai, some non-Maasai Tanzanians, and a few expatriates, were given very large tracts of land (e.g., the Stein Lease encompassed 381,000 acres). During the 1980s more non-Maasai were attempting to obtain large allocations and this worried village leaders. According to recent interviews, the initial push to allocate land to households was not driven by household heads advocating for such allocation, but from village leaders who felt that if land was not allocated to residents then it would be lost to outsiders.

As population increased, the desire for household allocations grew. Throughout our 14 years of research in Simanjiro, population growth has frequently been mentioned as a principle driver of the need for household land allocation, especially as interest in cultivation increased2. An individual allocation of land has come to be seen as necessary for a family’s economic well-being (Woodhouse and McCabe 2018).

Insecurity of land tenure remains an important concern. Villages that border Tarangire National Park feel their land is at risk due to potential park expansion (Baird, Leslie and McCabe, 2009, Davis 2010, 2011). The splitting of Arusha Region into Arusha and Manyara Regions in 2002 also contributed to the sense of insecurity of land tenure. Simanjiro was part of Arusha Region until 2002 and included many pastoral communities. Manyara Region, on the other hand, is composed primarily of agricultural communities, many of which have limited land for cultivation. As a result, some sub-villages in Simanjiro have allocated all their land to demonstrate that there is no “open” land.

Out migration

Young men began leaving their homes to seek work in urban areas in the early to mid-1990’s (McCabe et al. 2014). The principal form of employment was as guards at private homes and businesses. Maasai were able to benefit from their reputation as warriors but the work was dangerous and paid poorly. The temporary migrants were hoping to earn enough money to start a herd of their own but few were able to accumulate enough money to purchase anything more than a few goats and an occasional cow. However, some of these young men were successful enough to encourage other young men to seek work as guards. Over time the migration of young men away from Maasailand became an accepted norm, with many leaving home shortly after their circumcision and becoming warriors.

This pattern of labor migration spread all over Maasailand, but in the mid-1980s young men from Simanjiro began going to the tanzanite mines in the town of Merirani, just south of Kilimanjaro airport, but still within Simanjiro District. What made this migration so unusual was that they were not going there to work in the mines but rather to act as middlemen in the gem trade. The process of migration was also very different from that described above. Migration to the tanzanite mines was usually a family decision with the father providing enough money for one or more sons to go and learn the gem business. Unlike working as guards, some of these migrants made quite of bit of money -- in some cases, enough to buy new 4-wheel drive vehicles and tractors, and to build a modern house. In addition, many of these men were able to secure very large land allocations. For more on Maasai engaged in the gem trade see Smith 2012.

In addition to gaining material benefits, migrants experienced life outside of Maasailand and a livelihood not based on raising livestock. This experience, along with mixing with many non-Maasai, propelled many of these men to important positions in village leadership once they returned. As village leaders they were able to influence decisions relating to land use, emphasizing land allocations and large scale cultivation. In many ways this is similar to the events described by Lesorogol (2008) among the Samburu. There, young men with experience outside of their Samburu villages were able to overturn the emphasis on age as being critical to political leadership, which resulted in policies favoring the privatization of commonly managed grazing lands.

The acceptance of village governance and community managed resources

Following the establishment of each village, the official Tanzanian governance structure was put in place, with a chairperson and Village Council elected from the village assembly, as described above. However, very little changed as almost all the new chairpersons were the traditional leaders of the senior age sets, the olaigwanani. Wet and dry season pastures were regulated as before, with enforcement supported by the threat of a curse by village elders. According to one olaigwanani of the Makaa age set (1973– 1985) and a sub-village chair,

“Traditional leaders were adored until the late 1980s. They defined dry season grazing zones plus restricted where people could settle. A spell was cast by the traditional leaders to anyone who violated these rules. Once cast, the spell would result in the death of livestock by being eaten by wildlife or by being bitten by a snake; or the house of the violator would burn down. Once the violation was known all this would happen before sunset of the same day” (interview conducted in October, 2017).

An important official change was the appointment of a village executive officer (VEO) by the District government. For most of the Simanjiro and Longido villages this occurred in the 1980s and 1990s. Although the VEO works closely with the Village Council, he or she is the representative of the District government in the village and is often not of the same ethnic group as the village members. The appointment of VEOs marked a transition from local traditional leadership to more closely working within the larger governmental system. The significance of traditional leaders in governance is not restricted to the Maasai or to Tanzania.. Carolyn Logan (2011) used Afrobarometer data for 19 African counties to examine the role of traditional leaders in a continent-wide context.

Other factors as well were influential in formalizing the village as the principal governing body in Maasailand. Gardner (2016) argues that one significant factor was the desire of tour companies to secure rights among local communities to set up camps and to bring tourists into areas that were close to but not inside the national parks. Gardner provides the example of Dorobo Safaris in making arrangements with Maasai communities in the early 1990s, in which the company paid for exclusive right of access to village lands, and links this directly to the growing authority of the village as a key institution: “This new spatiality of conservation in Loliondo rests on the articulation of the village as a rights bearing entity grounded in historical, culturally based traditional rights. Through this new understanding, the village has become a meaningful social and spatial unit of rights and belonging” (Gardner 2016: 131).

Other aspects of village development were the construction of dams, clinics, schools and boreholes. Some of these were funded by religious organizations, NGOs and government agencies, but the management was under the control of village government.

The village land acts

In 1999 the Tanzanian government passed two acts that have been referred to as “the most important measures relating to land tenure in present Tanzania” (Roughton, 2007:552). The purpose of the acts (and the 2004 amendment to the Land Act), was to clarify the existing land laws, to develop land markets, to facilitate the equitable distribution of lands, and to allow women to own land (Mwangi 2009, Roughton 2007). The acts divide land into three categories: reserve land, which is set aside for purposes such as national parks and forest reserves; village land, which is land within the boundaries of a village; and general land which is all land not in the previous two categories but also includes unused village land. The Village Land Act devolves the authority to manage land within village boundaries to the Village Council, which may also appoint a land committee to facilitate decisions relating to land management. The Village Land Act has particular importance for women as it protects their rights to own3 land. It also allows the Village Council to write and enact by-laws which are legally binding. This last provision is especially important in our case study.

Although the Village Land Act stipulates that the Village Council is to act as the trustee for village lands, the land is still under the jurisdiction of the President of Tanzania. The Act also requires that the government issue a “certificate of village land” that recognizes the boundaries of each village (Roughton 2007). Village land is classified as communal village land, land used by an individual or group, and land that the Village Council can allocate. Following implementation of the Village Land Act, the Village Councils, along with land committees and often with the assistance of a NGO, designed land use plans that would be submitted and approved by the District government. Although these land use plans were based on the traditionally defined wet and dry season grazing areas, their management was now under the control of the village government. Sub-village boundaries were also established and included in the land use plans.

In some villages the wet and dry season grazing areas were marked by cement beacons, but what is crucial here is that land designations were now enforced by the village government through imposition of fines rather than by traditional leaders cursing any violators, a past norm. When asked about this transition we were repeatedly told that the power of traditional leaders to curse had significantly diminished. The reasons given for the erosion of powers of traditional leaders were the influence of the church, education, and “becoming modern”.

Drought

Droughts have been the principal environmental challenge facing the Maasai, and most climate change models predict that the severity and frequency of drought will increase in eastern Africa. The study area has seen three significant droughts in the last decade: 2008/09, 2011, and 2017. According to Msoffe et al. (2011) extreme droughts occurred in the Tarangire/Simanjiro ecosystem in 1961, 1965, 1974, 1976 and 1991, and severe droughts in 1967, 1975, 1982, 1992, 1993, 1997 and 2003 (their study period ended before the 2008/2009 drought).

For most pastoral people, the primary means of coping with drought is through mobility, and for the Maasai this has meant migrating within and outside of national and sectional boundaries. Access to resources was negotiated based on traditional institutions, which often involved clan affiliation, or just the accepted norm that all Maasai should help each other in times of stress. It is also understood that what happens in one area today could happen to another area tomorrow. Despite differences, and at times hostility, among sections of the Maasai, there was always a sense of trust that livestock would be able to cross spatial boundaries and that refusal to accommodate migrating livestock and their herders was unacceptable. This sense of trust among Maasai did not change as the villages designed and implemented their own land use plans, although the potential for change was recognized by some. As Mwangi stated in 2005: “Reduced mobility will likely magnify vulnerability to drought and may jeopardize the ability of the livestock enterprise upon which pastoral livelihoods are dependent. In the longer run, it may also undermine the reproduction of the pastoral culture. No doubt the Maasai are aware of this” (Mwangi 2005: 2).

Many areas that were former drought reserves have now been alienated from the Maasai by the boundaries of national parks and protected areas, and in places by the presence of large commercial farms. Sometimes herders will drive livestock across national park boundaries at night, or attempt to bribe rangers, but the risks can be substantial. This makes the ability to cross national, sectional and village boundaries all the more important.

This brings us back to the 2008/09 drought. As described in the opening vignette of this paper, many thousands (perhaps hundreds of thousands) of cattle, along with their herders, left the pastoral communities in southern Kenya and along the Kenya/Tanzania border area in a southward migration seeking better pasture and water. In all but one area these migrants were accommodated, if not outwardly welcomed. However, along the eastern escarpment of the Rift Valley, east of the Ngorongoro highlands in an area referred to as “Manyara” we were told in the group interviews that some local residents not only refused access to grazing for the migrating livestock, but berated the herders and in some cases attacked people at night. Some were beaten so badly that they had to be transported to hospitals in Arusha, many hours away by vehicle4. Discussions about this with Maasai who took part in that migration indicated that such violence and lack of accommodation had never happened before, and that in the event that the people from “Manyara” experienced similar drought conditions and needed to migrate north, they would be refused. This incident was deemed so important that this drought is referred to as the “Manyara drought” even though it was spatially much more extensive. It represents a significant break in the management of the social-ecological system of the northern Tanzanian rangelands. For the first time traditional institutions did not facilitate access to resources, and village boundaries were defended.

In Simanjiro, migrants were welcomed, and although the migrants suffered significant livestock loss, they felt that the trust that unites all Maasai in times of stress was maintained. However, many people in the Simanjiro communities that received the migrants felt that times had changed. Village based resources were overwhelmed and local resources depleted. Some maintain that even today, nearly a decade later, grazing resources have not recovered from the intensive use they experienced during this drought. After the migrants had returned north, land committees in three of the four Simanjiro villages in our study were charged with coming up with solutions to these problems in case of future droughts. The solutions were not uniform; they varied from defining a specific area for migrants to temporarily live and graze livestock, to setting limitations on the numbers of herds or livestock that could come in; to setting fees for grazing and water for each head of livestock; to specifying dates when parts of the village grazing zones could be opened to migrants and when they had to leave.

Such proposed measures were considered by the village councils and voted on by the village assemblies. They were then formalized and written into to the village by-laws. The formal codification by incorporation into the by-laws was most commonly explained by statements such as “We had to do it that way – otherwise it would be impossible to refuse friends or relatives but we know we have to protect our village resources.” We heard this repeatedly, which strongly suggests that under current conditions informal institutions that allowed access to resources by outsiders were, at least in Simanjiro, coming to be seen as unable to cope with the influx of outsiders. In discussing these changes with people in Longido (where the Tanzanian migrants came from) they said – “No that is impossible – when the next drought comes we will go back – they [the people in Simanjiro] cannot refuse us – we are all Maasai.” This is indicative of the evolving institutional dynamics among the Maasai in northern Tanzania. If people in Simanjiro refuse access to in-migrants, then we would expect that people in Longido would reciprocate in the same was as they say they will with people from Manyara.

Recent events- another drought, another test

In December 2017, due to yet another drought, herders from Kenya again began to move their cattle into the northern Tanzania rangelands. In the past, the Tanzanian government had occasionally intercepted such livestock and sent them back to Kenya. However, this time the cattle were confiscated and sold, and the herders returned to Kenya. This represented not a new policy but rather the strict enforcement of a policy that had only occasionally been enforced. Similar incidents were reported along the Kenya/Tanzania border near Loliondo, to the west of our study area. In interviews conducted in February 2018, one of us (JTM) was told that many cattle belonging to Kenyan Maasai were dying, but that the Kenyan Maasai were afraid to cross the border into Tanzania. This signifies an important policy shift that in essence cuts the Maasai social-ecological system in two. If this policy is maintained there will be social, ecological and economic implications for livestock keepers on both sides of the border5.

Discussion and Conclusions

The Longido/Simanjiro case study presented here is unique in relation to the literature on common property and institutional change in East Africa. Some of the motivations for privatization are similar to those described by Lesorogol (2008) for the Samburu and for the formation of group ranches and their division described by Mwangi (2005), but in both those instances the discussions focused on the conversion of communal land to individual holdings. The threat of loss of land to outsiders was considered important for Maasai initially agreeing to the formation of group ranches in Kenya, and this has relevance to the Tanzania case. However, with the exception of Gardner (2016), few if any publications explore the process of change in the management of natural resources in East Africa that we document here – the shift from control grounded in traditional informal institutions to formal village-based institutions.

The wider literature on common property emphasizes the complexity of understanding how common property resources are managed and change, and we certainly see complexity in our Tanzanian case. We also see how governmental policy interacts with local traditions and management practices to form a somewhat hybrid form of governance. The new rules and the uncertainty associated with what will happen in the future reflects Cleaver’s “institutional bricolage” (Cleaver et al. 2013). It also articulates well with the concept of the “new commons” (Bollig and Lesorogol 2016), entailing negotiation between older and newer forms of commons management. Typically (but not invariably), the former are informal, the latter formal.

It is also clear that the case study does not describe a completed transformation of common property management, nor of the larger social-ecological system. Rather, it describes an evolving process of transformation. The ongoing process and ongoing negotiation is seen in both past and more recent developments, which reflect not a linear shift in authority but rather iterated feedback wherein traditional and newer institutions mutually inform and influence one another and the resulting hybrid. For example, a decade ago traditional use of wet and dry season grazing areas, enforced by traditional leaders, provided the basis for the village-based land designations later enforced by the village government. Now, although the authority to manage resources is under the control of village governments, people have begun discussing the problems of having land management decisions made by politicians rather than traditional leaders. Another example is seen in current discussions among villages about combining rangelands, which might well entail management based on elements of traditional social organization (e.g., traditional leaders, age sets) that bridge the new formal village-based institutions.

It is clear that the two major policy shifts, Operation Imparnati in the 1970s and the Village Land Act of 1999, did not result in institutional change until long after the policies were implemented. It was the combination of multiple interacting factors that culminated in institutional change precipitated by an extreme event, in this case the 2008/09 drought. Especially important to the Longido/Simanjiro case are the perceptions of population increase, increasingly scarce and limited resources, an inability to control boundaries, and the erosion of traditional means of enforcement of management rules.

We may be witnessing the demise of a successful, long-term resilient social-ecological system encompassing the rangelands, the livestock, and the livelihoods of Maasai people in both Tanzania and Kenya. Ostrom pointed out the importance of trust and reciprocity for the successful management of a common property system. Trust has been challenged by the confiscation and sale of Kenyan livestock by the Tanzanian government. Reciprocity has been compromised by the refusal of people in “Manyara” to allow livestock to graze on village lands, and their beating of the migrant herders violated both trust and reciprocity.

We do not know how the villages in northern Tanzania will respond to the next drought – which communities will be on the sending and receiving sides of any migration, and what the expectations, rules followed, and reactions will be. But it is well understood that limiting mobility will reduce the adaptive capacity for people to respond to drought stress, will further fragment the rangelands and will pose a significant challenge to what has been a resilient SES. Just what the nature of the now transforming social-ecological system turns out to be – the specific elements of the system (mixture of new and traditional institutions, livelihood strategies, engagement with regional and global influences, etc.) and relationships among those elements – remains to be seen. The resilience of the transformed system to longstanding challenges such as drought along with newer environmental, social/economic/political perturbations, and the implications of all of this for the wellbeing of those in these communities, is similarly murky.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the National Science Foundation (BCS-1533552/1533502) for supporting the research we are reporting on here; the Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology for giving us research permission; and Dr. Cuthbert Nahonyo of the University of Dar es Salaam for providing letters of support. We also thank Gabriel ole Saitoti, Isaya ole Rumas and Stephen Sankeni who were integral members of our research team. We thank the Institute of Behavioral Science and the Department of Anthropology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill for general support through its NIH Center grant (P2C HD050924), and the Institute of Health and Wellbeing and Department of Sociology at the University of Glasgow for providing institutional support for conducting this research. Finally, we would like to thank the Maasai people of Simanjiro and Longido Districts in Tanzania for their participation in this research effort.

Footnotes

The Simanjiro plains are the wet season dispersal area for much of the wildlife living inside Tarangire National Park and this wet season migration is considered critical to the viability of the Park

Data collected at the village level confirms the perception of population increase

As mentioned previously, Tanzanian citizens do not technically “own” land, but the government is granting titles in a few experimental areas

In interviews conducted among some Manyara residences by Davis in 2017 no one admitted to taking part in these incidents.

There have been some very recent reports of people and livestock crossing the border for villagers living along the Kenya/Tanzania boundary.

Contributor Information

J. Terrence McCabe, Department of Anthropology, Hale Building, Campus Box 233 University of Colorado, Boulder; and Environment and Society Program, Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado, Boulder.

Paul W. Leslie, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill

Alicia Davis, University of Glasgow.

References Cited

- Anderies John, Janssen Marco, and Ostrom Elinor 2004. A Framework to Analyze the Robustness of Social-Ecological Systems from an Institutional Perspective. Ecology and Society 9(1):18 [Google Scholar]

- Baird Timothy D., Leslie Paul W., and Terrence McCabe J 2009. The Effect of Wildlife Conservation on Local Perceptions of Risk and Behavioral Response. Human Ecology 37(4):463–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bollig Michael, and Lesorogol Carolyn 2016. The “New Pastoral Commons” of Eastern and Southern Africa. International Journal of the Commons 10(2):665–687. [Google Scholar]

- Bromley Daniel W. 1989. Property Relations and Economic Development: The Other Land Reform. World Development 17(6):867–877. [Google Scholar]

- BurnSilver Shauna B., Worden Jeffery, and Boone Randall B. 2008. Processes of Fragmentation in the Amboseli Ecosystem, Southern Kajiado District, Kenya In Fragmentation in Semi-Arid and Arid Landscapes: Consequences for Human and Natural Landscapes. Galvin Kathleen A., Reid Robin S., Behnke Roy H. Jr., and Thompson Hobbs N, eds. Pp. 225–253. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Cleaver Frances, Franks Tom, Maganga Faustin and Hall Kurt 2013. ASR FORUM: ENGAGING WITH AFRICAN INFORMAL ECONOMIES: Institutions, Security, and Pastoralism: Exploring the Limits of Hybridity. African Studies Review 56(3):165–189. [Google Scholar]

- Davis Alicia 2010. Landscapes of Conservation: History, Perceptions, and Practice around Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Colorado at Boulder. [Google Scholar]

- 2011 ‘Ha! What Is the Benefit of Living next to the park?’Factors Limiting in-Migration Next to Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. Conservation and Society 9(1): 25. [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger Jean 1996. Making a Market: The Institutional Transformation of an African Society. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Folke Carl 2006. Resilience, the Emergence of a Perspective for Social-Ecological Systems Analysis. Global Environmental Change 16(3):253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Galvin Kathleen A. 2009. Transitions: Pastoralists living with change. Annual Review of Anthropology 38:185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner Benjamin 2016. Selling the Serengeti: The Cultural Politics of Safari Tourism. University of Georgia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman Mara (in press) Narrating Nature Maasai knowledge and wildlife conservation in Tanzania. Arizona University Press [Google Scholar]

- Goldman Mara J., and Riosmena Fernando 2013. Adaptive Capacity in Tanzanian Maasailand: Changing Strategies to Cope with Drought in Fragmented Landscapes. Global Environmental Change 23(3): 588–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman Mara J, Davis Alicia, and Little Jani 2016. Controlling Land They Call Their Own: Access and Women’s Empowerment in Northern Tanzania. The Journal of Peasant Studies 43(4): 777–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson Dorothy L. 2011. Being Maasai, Becoming Indigenous: Postcolonial Politics in a Neoliberal World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Homewood Katherine, and Rodgers WA 1991. Maasailand Ecology: Pastoralist Development and Wildlife Conservation in Ngorongoro, Tanzania. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Homewood Katherine, and Brockington Daniel 1999. Biodiversity, Conservation and Development in Mkomazi Game Reserve, Tanzania. Global Ecology and Biogeography 8(3–4):301–313. [Google Scholar]

- Homewood Katherine 2008. Ecology of African Pastoralist Societies. Oxford: James Currey. [Google Scholar]

- 2013. Comment on Leslie Paul and Terrence McCabe’s J “Response Diversity and Resilience in Social-Ecological System.” Current Anthropology 54(2):131–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hydén Göran 1980. Beyond Ujamaa in Tanzania: Underdevelopment and an Uncaptured Peasantry. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Igoe Jim 2003. Scaling Up Civil Society: Donor Money, NGOs and the Pastoralist Land Rights Movement in Tanzania. Development and Change 34(5):863–85. [Google Scholar]

- Laerhoven Frank van, and Ostrom Elinor 2007. Traditions and Trends in the Study of the Commons. International Journal of the Commons 1(1):3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie Paul, and Terrence McCabe J 2013. Response Diversity and Resilience in Social-ecological Systems. Current Anthropology 54(2): 114–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesorogol Carolyn K. 2008. Contesting the Commons: Privatizing pastoral lands in Kenya. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Logan Carolyn 2011. The Roots of Resilience: Exploring Popular Support for African Traditional Authorities. AfroBarometer Working Paper No. 128. URL: <https://afrobarometer.org/publications/wp128-roots-resilience-exploring-popular-support-african-traditional-authorities> [Google Scholar]

- May Ann, and Terrence McCabe J 2004. City Work in a Time of AIDS: Maasai Labor Migration in Tanzania. Africa Today 51(2):3–32. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe J. Terrence 2003. Sustainability and Livelihood Diversification Among the Maasai of Northern Tanzania. Human Organization 62(2):100–111. [Google Scholar]

- 2004 Cattle Bring Us to Our Enemies: Turkana Ecology, Politics and Raiding in a Disequilibrium System. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe J. Terrence, Leslie Paul W., and DeLuca Laura 2010. Adopting Cultivation to Remain Pastoralists: The Diversification of Maasai Livelihoods in Northern Tanzania. Human Ecology 38(3):321–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe J. Terrence, Smith Nicole, Leslie Paul, and Telligman Amy L. 2014. Livelihood Diversification Through Migration Among a Pastoral People: Contrasting Case Studies of Maasai in Northern Tanzania. Human Organization 7(4):389–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Msoffe Fortunata U., Kifugo Shem, Said Mohammed Y., Moses Ole Neselle Paul Van Gardingen, Reid Robin S., Ogutu Joseph O., Herero Mario, and De Leeuw Jan 2011. Drivers and Impacts of Land-use Change in the Maasai Steppe of Northern Tanzania: An Ecological, Social and Political Analysis. Journal of Land Use Science 6(4):261–281. [Google Scholar]

- Mwangi Esther N. 2003. Institutional Change and Politics: The Transformation of Property Rights in Kenya’s Maasailand. Ann Arbor, MI: Indiana University. [Google Scholar]

- 2005. The Transformation of Property Rights in Kenya’s Maasailand: Triggers and Motivations. International Food Policy Research Institute CAPRi; Working Paper 35. DOI: 10.22004/ag.econ.42492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2007. Subdividing the Commons: Distributional Conflict in the Transition from Collective to Individual Property Rights in Kenya’s Maasailand. World Development 35(5):815–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mwangi Esther, and Ostrom Elinor 2009. Top-down Solutions: Looking Up from East Africa’s Rangelands. Environment 51(1):34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ndagala Daniel 1982. Operation Imaparnati: The Sedentarization of the Pastoral Maasai. Nomadic Peoples (10): 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley Marion Elizabeth 2000. Cattle and Cultivation: Changing Land Use and Labor Patterns in Pastoral Maasai Livelihoods, Loliondo Division, Ngorongoro District, Tanzania. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Colorado at Boulder. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom Elinor 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2003. How Types of Goods and Property Rights Jointly Affect Collective Action. Journal of Theoretical Politics 15(3):239–270. [Google Scholar]

- 2009. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science 325(5939):419–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quandt Amy 2018. Measuring Livelihood Resilience: The Household Livelihood Resilience Approach. World Development 107: 253–263. [Google Scholar]

- Reid Robin S., Fernández-Giménez María E., and Galvin Kathleen A. 2014. Dynamics and Resilience of Rangelands and Pastoral Peoples Around the Globe. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 39: 217–242. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson Lance, and Berkes Fikret 2010. Applying Resilience Thinking to Questions of Policy for Pastoralist Systems: Lessons from the Gabra of Northern Kenya. Human Ecology 38(3): 335–350 [Google Scholar]

- Roughton Geoffrey E. 2007. Comprehensive Land Reform as a Vehicle for Change: An Analysis of the Operation and Implications of the Tanzanian Land Acts of 1999 and 2004. Columbia Journal of Transnational Law 45(2): 551–585. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider Leander 2014. Government of Development: Peasants, and Politicians in Postcolonial Tanzania. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shivji Issa G. 1998. Not Yet Democracy: Reforming Land Tenure in Tanzania. London: International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). [Google Scholar]

- Smith Nicole M. 2012. Maasai and the Tanzanite Trade: New Facets of Livelihood Diversification in Northern Tanzania. Ph.D. dissertation. University of Colorado at Boulder. [Google Scholar]

- Trench Pippa Chenevix, Kiruswa Steven, Nelson Fred, and Homewood Katherine 2009. Still “People of Cattle”? Livelihoods, Diversification and Community Conservation in Longido District In Staying Maasai? Livelihoods, Conservation, and Development in East African Rangelands. Homewood Katherine, Kristjanson Patti and Trench Pippa Chenevix, eds. Pp. 217–256. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhite DA 2000. Drought as a Natural Hazard: Concepts and Definitions In Wilhite DA (ed), Drought a Glpbal Assessments. Vol. 1,pp.3–18. London: Routledge [Google Scholar]

- Woodhouse E and Terrence McCabe J 2018. Well-being and Conservation: Diversity and Change in Visions of a Good Life Among the Maasai of Northern Tanzania. Ecology and Society 23(1):43. [Google Scholar]

- Yami Mastewal, Vogl Christian, and Hauser Michael 2009. Comparing the Effectiveness of Informal and Formal Institutions in Sustainable Common Pool Resources Management in Sub-Saharan Africa. Conservation and Society 7(3):153–164. [Google Scholar]