Abstract

Background/Aims

Undetectable HCV RNA 12 weeks after the end of treatment (SVR12) has been the valid efficacy endpoint in the era of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs). Its concordance with SVR4 and SVR24 and long-term durability is unknown in Taiwanese chronic hepatitis C (CHC) patients.

Methods

A total of 1080 CHC patients who received all-oral DAAs and an achieved end-of-treatment virological response (EOTVR), defined as undetectable HCV RNA at the end of therapy, were consecutively enrolled. HCV RNA was monitored 4, 12, and 24 weeks after EOT. Patients who achieved SVR24, defined as undetectable HCV RNA 24 weeks after EOT, were followed annually for assessing SVR durability.

Results

Eleven (1.02%) patients experienced HCV RNA reappearance after EOT. The most frequent timing of RNA reappearance was observed at SVR4 (n = 7), followed by SVR12 (n = 3) and SVR 24 (n = 1). The positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of SVR4 in predicting SVR12 were 99.7% and 100%, respectively, whereas the PPV and NPV of SVR12 in predicting SVR24 were 99.9% and 100%, respectively. Pyrosequencing confirmed delayed relapse rather than reinfection for the patient who had detectable HCV RNA at SVR24. Among 978 patients who achieved SVR24, after a median follow-up period of 17.3±8.2 months, the SVR durability is 100% up to a 4-year follow-up.

Conclusion

Achievement of SVR12 provides excellent durability of HCV seroclearance after DAA therapy. On-demand HCV RNA beyond SVR12 should be recommended for patients with unexplainable abnormal liver function or high-risk behaviors.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is one of the leading etiologies of liver-related morbidities and mortalities worldwide [1]. Approximately 71 million individuals are chronically infected with HCV worldwide [2], accounting for one-third of the patient population with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Fortunately, HCV eradication by antiviral therapy greatly reduces the risk for HCC, liver decompensation and liver-related mortality [3–6].

The definition of successful HCV eradication is a sustained virological response (SVR), which is defined as undetectable HCV RNA throughout 24 weeks of the posttreatment follow-up period (SVR24) in the interferon era [7–9]. Thanks to their excellent efficacy and tolerability [1, 10], all-oral direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) have been the standard of care for chronic hepatitis C (CHC) since 2014. Due to the high concordance of SVR24 and SVR12, defined as undetectable HCV RNA throughout the 12-week posttreatment follow-up period, SVR12 has been widely accepted as a valid efficacy endpoint in the DAA era [11]. However, the concordance between SVR12 and SVR24 has rarely been systematically assessed in Taiwanese CHC patients. Notably, there were few cases of late recurrent viremia, defined as patients who achieved SVR12 but experienced HCV RNA recurrence at or after follow-up week 24 [12]. It is important to distinguish late virologic relapse from reinfection in view of the post-DAA follow-up strategy. On the other hand, a high SVR durability has been reported for patients who have successfully eradicated HCV by daclatasvir-based regimens [13]. While the result is consistent with the use of recently approved and more potent DAAs, it remains elusive in Taiwanese patients. Overall, the current study aimed to identify the timing of virological failure among CHC patients who achieved end-of-treatment virological response (EOTVR) by DAAs. Accordingly, we also sought to address the concordance among SVR4, SVR12, and SVR24, as well as long-term SVR durability, in a well-characterized CHC cohort.

Methods

CHC patients who received all-oral DAA regimens in the outpatient departments of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital and two regional hospitals, Kaohsiung Municipal Ta-Tung Hospital and Kaohsiung Municipal Siaogang Hospital, were consecutively enrolled during the daily practice from February 2015 to October 2018. The treatment regimens and strategies conformed to the regional guidelines and the regulation of the Health and Welfare Department of Taiwan [1] and regional guidelines [14, 15]. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) adults aged 20 years or older; (2) those who were interferon treatment-naïve or treatment experienced; and (3) those who completed the full treatment course and achieved the end-of-treatment virological response (EOTVR, defined as HCV RNA seronegativity at the end of treatment). Patients were excluded if they had the following: (1) HCV RNA seropositivity at EOT, either due to treatment failure or virological breakthrough, or (2) lost to follow-up during the treatment or follow-up period.

Patients who had virological data at posttreatment week 4 (SVR 4), posttreatment week 12 (SVR 12), and posttreatment week 24 (SVR 24) were evaluated for the concordance of SVR4 with SVR 12 and SVR12 with SVR 24. Among the patients who achieved SVR24, HCV RNA was followed annually to assess SVR durability. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (IRB number: KMUHIRB-F(I)-20170053), which conformed to the guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization for Good Clinical Practice. All patients provided written informed consent.

The primary objective was to address RNA reappearance after EOT. The HCV genotype was assessed before treatment and at the time of RNA reappearance. HCV RNA and genotypes were determined using a real-time PCR assay (RealTime HCV; Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines IL, USA; detection limit: 12 IU/ml) [16]. For patients who had RNA reappearance after SVR12, viral sequencing on nonstructural protein 3 (NS3) and NS5B was performed to compare the viral genetic similarity (AnGene Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; targeting the core protein). Liver cirrhosis was defined by liver histology, transient elastography (FibroScan®; Echosens, Paris, France; > 12 kPa) [17], acoustic radiation force impulse (> 1.98 m/s) [18], or fibrosis-4 index (>6.5); the presence of clinical, radiologic, endoscopic, or laboratory evidence of cirrhosis and/or portal hypertension; or symptoms of clinical hepatic decompensation (ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, jaundice, or variceal hemorrhage).

Statistical analyses

Group means are presented as the means ± standard deviations. The fibrosis index 4 (FIB-4) was calculated by the following formula: age (years) × aspartate aminotransferase (AST) [U/L]/(platelets [109/L] [8] × (alanine transaminase (ALT) [U/L]))1/2. The concordance of the virological responses between different time points (SVR4, SVR12 and SVR24) was compared and expressed as positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV). The procedures were performed using the SPSS 22.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

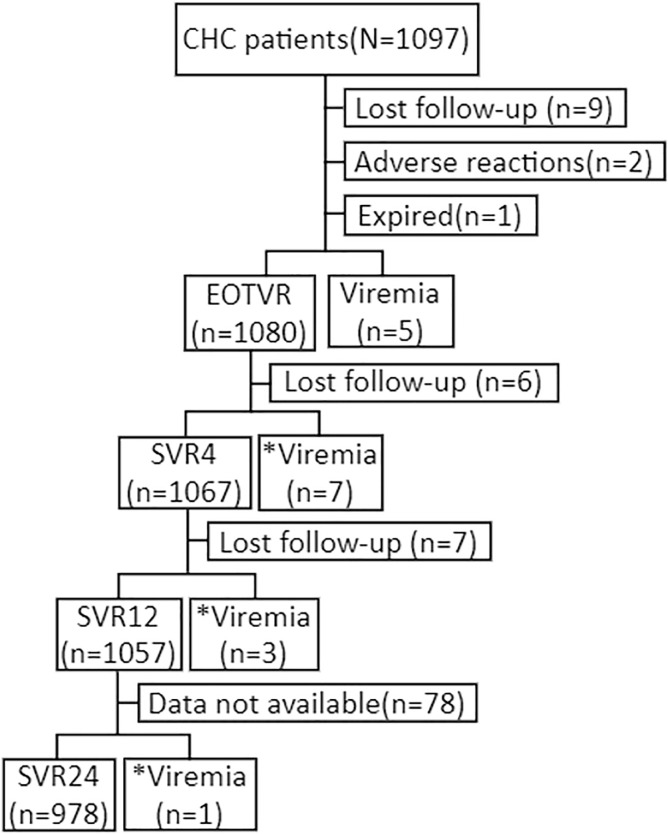

A total of 1097 patients were initially enrolled. After excluding patients who were lost to follow-up (n = 9), early treatment termination (n = 2), mortality during treatment (n = 1), and remained viremic at EOT (n = 5), 1080 patients who achieved EOTVR were enrolled for final analysis in the current study (Fig 1). The basic demographic, virological, and clinical features and DAA regimens of the patients are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 62.9 years. Males accounted for 43.0% of the population. The majority of patients had HCV genotype 1 infection (HCV-1, 69.7%). Five hundred sixty-five patients (52.3%) had liver cirrhosis. The mean FIB-4 was 4.3. The most commonly used DAA was paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir/dasabuvir (PrOD, 37.3%), followed by sofosbuvir/ledipasvir (17.3%).

Fig 1. Study flowchart.

Abbreviations: CHC: chronic hepatitis C. EOTVR: end-of-treatment virological response. * Viremia represents patients who experienced virological reappearance after EOT.

Table 1. Basic characteristics and treatment regimens of the patients.

| N = 1080 | |

|---|---|

| Gender, male/female, n (%) | 464/616 (43.0/57.0) |

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 62.9±11.2 |

| Platelet count, x1000 /mm3 (mean±SD) | 161±71 |

| AST, IU/L (mean±SD) | 73.7±51.1 |

| ALT, IU/L (mean±SD) | 80.9±64.8 |

| Serum albumin, g/dL(mean±SD) | 4.2±0.4 |

| Serum bilirubin, mg/dL (mean±SD) | 1.02±0.54 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL(mean±SD) | 1.08±1.28 |

| HCV viral load, 1og IU/ml (mean±SD) | 6.40±7.18 |

| High HCV viral loads, n (%) | 510 (47.2) |

| HCV genotype, n (%) | |

| 1 | 753 (69.7) |

| Non-1 | 327 (30.3) |

| Liver cirrhosis, n (%) | 565 (52.4) |

| HIV co-infection, n (%) | 34(3.1) |

| Persons who inject drugs, n (%) | 58(5.4) |

| DAA regimen, n (%) | |

| PrOD±RBV | 403 (37.3) |

| DCV/ASV±RBV | 59 (5.5) |

| SOF/RBV | 169 (15,6) |

| SOF/LDV±RBV | 187 (17.3) |

| SOF/DCV±RBV | 110 (10.2) |

| ELB/GRZ | 115 (10.6) |

| GLE/PIB | 32(3.0) |

| SOF/VEL | 5 (0.5) |

Note: AST, aspartate aminotransferase. ALT, alanine aminotransferase. PrOD, Paritaprevir/ritonavir/Ombitasvir/Dasabuvir. DCV, Daclatasvir. ASV, Asunaprevir. SOF, Sofosbuvir. LDV, Ledipasvir. ELB, Elbasvir. GRZ, Grazoprevir. GLE, Glecaprevir. PIB, Pibrentasvir. VEL, Velpatasvir. RBV, Ribavirin. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Among the subjects, 11 (1.02%) patients experienced virological reappearance, and the most frequent timing of viral reappearance was week 4 (n = 7), followed by week 12 (n = 3) and week 24 (n = 1) after EOT. Of the 1060 patients with SVR12 data available, 1057 (99.7%) achieved an SVR12, leading to a 99.7% PPV and a 100% NPV of SVR4 for SVR12. Of the 979 patients with SVR24 data available, 978 (99.9%) achieved an SVR24, leading to a 99.9% PPV and a 100% NPV of SVR12 for SVR24.

The characteristics and serial viral kinetics of the eleven patients who encountered HCV RNA reappearance after EOT are listed in Table 2. Among them, six (54.5%) were infected with HCV genotype 2 and received a sofosbuvir-plus-ribavirin regimen. Nine patients (81.8%) had liver cirrhosis. All HCV genotypes at the time of RNA reappearance were the same as the pretreatment genotypes. A 72-year-old cirrhotic female patient (Case 11) who had RNA reappearance at SVR24 also had the same HCV genotype, HCV-1b, before and after DAA treatment. Pyrosequencing revealed 99.7% similarity before treatment and at the time of RNA reappearance, indicating virological relapse rather than reinfection of the patient.

Table 2. Characteristics and serial viral kinetics of the patients with virological failure.

| Case Number | Age/gender | BL genotype | BL HCV viral load (*103IU/ml) | Regimen/Weeks of Tx | LC | W2 | W4 | W8 | EOT | M1 | M3 | M6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 61/M | 2 | 48.2 | SOF+RBV/12 | + | 0.06 | <0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 | 110.7 | NA |

| 2 | 61/F | 1b | 1787.3 | DCV+ASV/24 | - | 0.06 | <0.03 | LLOD | LLOD | LLOD | 1500.4 | 929.9 |

| 3 | 65/F | 2 | 521.4 | SOF+RBV/12 | + | 0.16 | 0.06 | <0.03 | LLOD | 1692.3 | 457.7 | 67.2 |

| 4 | 66/M | 2 | 3918.8 | SOF+RBV/12 | + | <0.03 | LLOD | LLOD | LLOD | 340.5 | 352.4 | 217.5 |

| 5 | 46/M | 2 | 1677.5 | SOF+RBV/12 | - | 0.10 | <0.03 | LLOD | LLOD | 0.1 | 3305.2 | 4340.0 |

| 6 | 49/F | 2 | 1342 | SOF+RBV/12 | + | 0.08 | LLOD | LLOD | LLOD | 4166.3 | 2288.2 | NA |

| 7 | 58/M | 1a | 113.8 | SOF+LDV/12 | + | 0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 | 122.4 | 100.5 | NA |

| 8 | 62/M | 2 | 793.6 | SOF+RBV/12 | + | LLOD | LLOD | LLOD | LLOD | 20.0 | 19.7 | NA |

| 9 | 61/M | 1b+2b | 507.5 | ELB+GRZ/12 | + | 0.07 | <0.03 | LLOD | LLOD | LLOD | 759.3 | 586.2 |

| 10 | 42/M | 6 | 9482 | SOF+LDV/12 | + | <0.03 | LLOD | LLOD | LLOD | 4709.6 | 12192.5 | 16462.7 |

| 11 | 72/F | 1b | 1219 | ELB+GRZ/12 | + | 0.10 | 0.05 | LLOD | LLOD | LLOD | LLOD | 425.2 |

Note: Abbreviations: M, male. F, female. BL, baseline. Tx, treatment. SOF, Sofosbuvir. RBV, Ribavirin. DCV, Daclatasvir. ASV, Asunaprevir. LDV, Ledipasvir. ELB, Elbasvir. GRZ, Grazoprevir. LLOD: Lower Limit of Detection, NA: Not available.

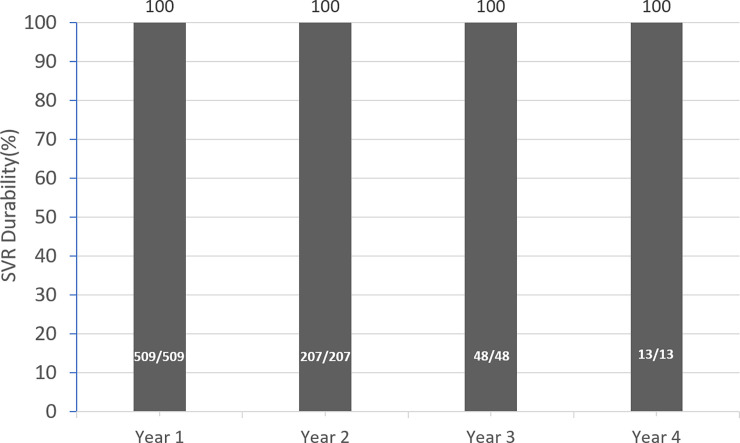

The mean follow-up period in the post-SVR era was 17.2±7.6 months. The SVR durability among the patients who achieved SVR24 was 100% (509/509), 100% (207/207), 100% (48/48) and 100% (13/13) at year 1, year 2, year 3 and year 4, respectively (Fig 2).

Fig 2. SVR durability beyond SVR24.

SVR: sustained virological response.

Discussion

The current study constantly supported the application of SVR12 as the primary efficacy endpoint in the era of DAAs for Taiwanese patients. With the broad use of more potent DAAs, including the pangenotypic glecaprevir/pibrentasvir and sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, the concordance of SVR 4 with SVR 12 was 99.7%, and the concordance of SVR 12 with SVR24 was 99.9%. Only one case experienced late virological relapse at SVR24. In addition, the durability beyond SVR24 was 100% in the current cohort.

Of the patients who relapsed after the end of therapy, two-thirds relapsed within the first 4 weeks, whereas one-third relapsed between posttreatment weeks 4 and 12, indicating that SVR4 may not be a suitable endpoint for primary efficacy analyses. On the other hand, SVR12 and SVR24 were highly concordant, which was in line with previous studies [11, 19]. The current study reinforced the recommendation of regional guidelines [20], which stated that both SVR12 and SVR24 could serve as the endpoints of therapy given > 99% concordance. Reddy et al. reported that twelve out of 1329 patients (0.9%) experienced virological relapse after SVR12 after using daclatasvir-based regimens. Among them, nine relapsed between SVR12 and SVR24, whereas three relapsed after SVR24. Notably, the majority of patients who relapsed after SVR12 had used less potent DAAs (daclatasivir/asunaprevir or interferon-containing regimens) [13]. In the current study, there was only one patient who relapsed at SVR24. With the current use of more potent DAAs, clinicians may have more confidence using SVR12 as the primary efficacy endpoint in the clinical setting.

The SVR durability in patients who achieved SVR24 was 100% beyond 4 years of follow-up in the current study. The result was also similar to that in a long-term follow-up study [13]. The timing and frequency of rechecking HCV RNA in patients who were documented to have an SVR leaves room for discussion [21]. Annual HCV RNA follow-up for reinfection in certain high-risk populations, such as PWID and men who have sex with men, was recommended by regional consensus [15, 20]. Patients who have unexplained abnormal liver function during the follow-up period may also be indicated regardless of the risk of reinfection. Boschi et al. [22] reported a 53-year-old HIV-negative cirrhotic man who was chronically infected with HCV genotype 4r. He was treated with sofosbuvir plus simeprevir for 12 weeks and achieved SVR24. The patient had no injectable drug use or any other potential risk behavior for HCV acquisition. However, unexpectedly detectable HCV RNA was noted 78 weeks after EOT. Phylogenetically clustered protease sequences confirmed the diagnosis of late relapse. The current cohort comprised a subset of patients with HIV coinfection and PWID, and there were no patients who experienced reinfection as of the time of manuscript writing. A longer observational period is warranted to clarify the issue of reinfection or delay relapse in the post-SVR era.

There were some limitations in the current study. Gene sequencing was not performed in patients who had HCV RNA reappearance before SVR12. We could not completely exclude the possibility of reinfection rather than relapse in these patients. However, the HCV genotypes were the same before and after treatment, and there were no known risk factors for reinfection (e.g., PWID, HIV coinfection, and MSM), which favored relapse of these patients. Although the SVR durability was 100% at present, a longer follow-up duration is needed for the potential chance of extremely late relapse or reinfection in the cohort [13]. In conclusion, SVR12 remains the standard endpoint following DAA therapy. The current National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA) of Taiwan supports HCV RNA testing until SVR12. Although the incidence of late recurrence after SVR12 is rare, regular or on-demand follow-up of HCV RNA after SVR 12 may be warranted, particularly for patients with abnormal liver function and high-risk behaviors.

Supporting information

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

The study was supported by grants from Kaohsiung Medical University (MOST108-2314-B-037), Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (KMUH108-8R05), the Center for Cancer Research (KMU-TC108A04-3), the Center for Liquid Biopsy (KMU-TC108B06) and the Cohort Research Center (KMU-TC108B07, KMUDK109002).

References

- 1.Huang CF, Yeh ML, Huang CI, Liang PC, Lin YH, Hsieh MY, et al. Equal treatment efficacy of direct-acting antivirals in patients with chronic hepatitis C and hepatocellular carcinoma? A prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e026703 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators. Global prevalence and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus infection in 2015: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2(3):161–176. 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30181-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang CF, Yeh ML, Tsai PC, Hsieh MH,Yang HL,Hsieh MY, et al. Baseline gamma-glutamyl transferase levels strongly correlate with hepatocellular carcinoma development in non-cirrhotic patients with successful hepatitis C virus eradication. J Hepatol 2014;61(1):67–74. 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu ML, Huang CF, Yeh ML, Tsai PC, Huang CI, Hsieh MH, et al. Time-degenerative factors and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma after antiviral therapy among hepatitis c virus patients: a model for prioritization of treatment. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23(7):1690–1697. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ioannou GN, Green PK, Berry K. HCV eradication induced by direct-acting antiviral agents reduces the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma J Hepatol. 2017; S0168-8278(17)32273-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dieperink E, Pocha C, Thuras P, Knott A, Colton S, Ho SB. All-cause mortality and liver-related outcomes following successful antiviral treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci 2014;59(4):872–880 10.1007/s10620-014-3050-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Meer AJ, Veldt BJ, Feld JJ, Wedemeyer H, Dufour JF, Lammert F, et al. Association between sustained virological response and all-cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosis. JAMA. 2012;308(24):2584–2593. 10.1001/jama.2012.144878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu ML, Dai CY, Huang JF, Chiu CF, Yang YH, Hou NJ, et al. Rapid virological response and treatment duration for Chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 patients: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2008;47(6):1884–1893. 10.1002/hep.22319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu ML, Dai CY, Huang JF, Hou NJ, Lee LP, Hsieh MY, et al. A randomised study of peginterferon and ribavirin for 16 versus 24 weeks in patients with genotype 2 chronic hepatitis C. Gut. 2007;56(4):553–559. 10.1136/gut.2006.102558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang CF, Lio E, Jun DW, Ogawa E,Toyoda H, Hsu YC, et al. Direct-acting antivirals in East Asian hepatitis C patients: real-world experience from the REAL-C Consortium. Hepatol Int. 2019;13(5):587–598. 10.1007/s12072-019-09974-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshida EM, Sulkowski MS, Gane EJ, Herring RW Jr, Ratziu V, Ding X, et al. Concordance of sustained virological response 4, 12, and 24 weeks post-treatment with sofosbuvir-containing regimens for hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2015;61(1):41–45. 10.1002/hep.27366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarrazin C, Isakov V, Svarovskaia ES, Hedskog C, Martin R, Chodavarapu K, et al. Late Relapse Versus Hepatitis C Virus Reinfection in Patients With Sustained Virologic Response After Sofosbuvir-Based Therapies. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(1):44–52. 10.1093/cid/ciw676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy KR, Pol S, Thuluvath PJ, Toyota J, Chayama K, Levin J, et al. Long-term follow-up of clinical trial patients treated for chronic HCV infection with daclatasvir-based regimens. Liver Int. 2018;38(5):821–833. 10.1111/liv.13596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu ML, Chen PJ, Dai CY, Hu TH, Huang CF, Huang YH, et al. 2020 Taiwan consensus statement on the management of hepatitis C: part (I) general population. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119(6):1019–1040 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu ML, Chen PJ, Dai CY, Hu TH, Huang CF, Huang YH, et al. 2020 Taiwan consensus statement on the management of hepatitis C: Part (II) special populations. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119(7):1135–1157. 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vermehren J, Yu ML, Monto A, Yao JD, Anderson C, Bertuzis R, et al. Multi-center evaluation of the Abbott RealTime HCV assay for monitoring patients undergoing antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Virol. 2011;52(2):133–137. 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castéra L, Vergniol J, Foucher J, Le Bail B, Chanteloup E, Haaser M, et al. Prospective comparison of transient elastography, Fibrotest, APRI, and liver biopsy for the assessment of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(2):343–350. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin YH, Yeh ML, Huang CI, Yang JF, Liang PC, Huang CF, et al. The performance of acoustic radiation force impulse imaging in predicting liver fibrosis in chronic liver diseases. Kaoshiung J Med Sci 2016;32(7):362–366. 10.1016/j.kjms.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burgess SV, Hussaini T, Yoshida EM. Concordance of sustained virologic response at weeks 4, 12 and 24 post-treatment of hepatitis c in the era of new oral direct-acting antivirals: A concise review. Ann Hepatol 2016;15(2):154–159. 10.5604/16652681.1193693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2018. J Hepatol. 2018;69(2):461–511. 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghany MG, Morgan TR; AASLD-IDSA Hepatitis C Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C Guidance 2019 Update: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases-Infectious Diseases Society of America Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Hepatology. 2020;71(2):686–721. 10.1002/hep.31060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boschi C, Colson P, Tissot-Dupont H, Bernit E, Botta-Fridlund D, Aherfi S. Hepatitis C Virus Relapse 78 Weeks After Completion of Successful Direct-Acting Therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(6):1051–1053. 10.1093/cid/cix457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.