Abstract

Background

Global pandemics have a profound psycho-social impact on health systems and their impact on healthcare workers is under-reported.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional survey with 13 Likert-scale responses and some additional polar questions pertaining to dressing habits and learning in a university hospital in the midwest United States. Descriptive and analytical statistics were performed.

Results

The 370 respondents (66.1% response rate, age 38.5±11.6 years; 64.9% female), included 102 supervising providers [96 (25.9%) physicians, 6 (1.6%) mid-level], 64 (17.3%) residents/fellows, 73 (19.7% nurses, 45 (12.2%) respiratory therapists, 31 (8.4%) therapy services and others: 12 (3.2%) case-managers, 4 (1.1%) dietitians, 39 (10.5%) unclassified]. Overall, 200 (54.1%) had increased anxiety, 115 (31.1%) felt overwhelmed, 159 (42.9%) had fear of death, and 281 (75.9%) changed dressing habits. Females were more anxious (70.7% vs. 56%, X2 (1, N=292)=5.953, p=0.015), overwhelmed (45.6% vs. 27.3%, X2 (1, N=273)=8.67, p=0.003) and suffered sleep disturbances (52% vs. 39%, X2 (1, N=312)=4.91, p=0.027). Administration was supportive; 243 (84.1%, N=289), 276 (74.5%) knew another co-worker with COVID-19, and only 93 (25.1%) felt healthcare employment was less favorable. Residents and fellows reported a negative impact on their training despite feeling supported by their program.

Conclusion

Despite belief of a supportive administration, over half of healthcare workers and learners reported increased anxiety, and nearly a third felt overwhelmed during this current pandemic.

Introduction

Pandemics are large scale outbreaks of infectious diseases that occur typically across continents, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality. The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has caused more than 13 million cases and 272,000 deaths in the United States (U.S.) to date.1 The health sector is not exempt to financial losses, moreover, it is particularly vulnerable to suffer more financial burden from increasing (at times overwhelming) number of cases. The American Heart Association estimated that between March 1 and June 30, 2020, hospitals and health systems suffered $202.6 billion in losses.2 This is further compounded by national shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), thus directly impacting frontline healthcare workers who fight to serve patients on a daily basis. Prior viral pandemics such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) have caused psychological distress among healthcare workers.3–7 While vigilance exists for vital financial aspects of the health care system during such pandemics, the direct and indirect psychosocial impact of such pandemics on the workflow and workplace of a health care worker is often not prioritized as a concern and is seldom addressed. There are several reports and studies on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers elsewhere but there is paucity of such studies in the United States, except for one study among nurses in Michigan.8–24 Hence, we performed a study to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on our university hospital’s healthcare workers and training programs (residencies and fellowships).

Methods

We performed an anonymous survey of healthcare providers at our university hospital between April 15 and May 10, 2020, after approval from our institutional review board. At the time of the survey, the daily number of hospitalized COVID-19 cases were lower, i.e. ≤ 20 cases (intensive care unit cases <8 per day) in our institution, the hospital had resumed elective surgical procedures, and continued to have a restricted visitor policy. The survey contained 13 Likert scale (5 point) questions aimed to assess the psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their work environment and two questions with yes/no responses for dressing habits and their knowledge of a sick co-worker. There were two additional questions on the impact of the pandemic on medical education of residents and fellows. Pulmonary, critical care, and infectious disease faculty reviewed the survey questionnaire (Supplement 1) for face validity. We followed the EQUATOR network’s reporting guidelines for the design and conduct of surveys.25,26 In order to understand the psychosocial impact of this pandemic across all strata of frontline health care workers in a hospital system, our target population included attending physicians, fellows, residents, nurse practitioners, nurses, therapy services (physical and occupational therapists), respiratory therapists, and social workers, etc., across all medical and surgical subspecialties.

Institutional group email accounts for each specific group were emailed a link to an electronic survey designed using research electronic data capture (REDCap) tools hosted at the University of Missouri. We stated that participation is completely voluntary and that no incentive will be provided.27,28 REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies, providing 1) an intuitive interface for validated data capture; 2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; 3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and 4) procedures for data integration and interoperability with external sources.

Additional paper surveys were used for a minority of respondents in the medical intensive care units (ICU) per their preference. Demographic data are represented as numbers and percentages, non-parametric continuous variables were analyzed with Mann Whitney U test and categorical variables were analyzed with Chi-square tests. For comparative analysis we excluded “neutral” responses and combined ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’ responses as one group and similarly, grouped ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘disagree’ responses together. Data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 (© Copyright IBM Corporation).

Results

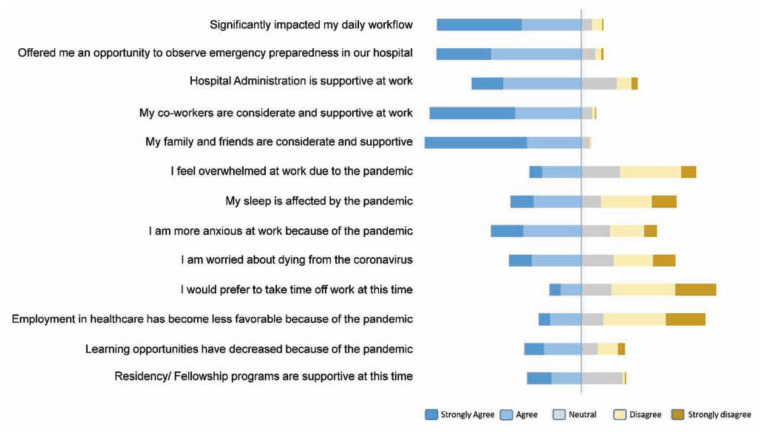

Of the 560 email recipients, 370 completed the survey [66.1% response rate, age 38.5 ± 11.6 years, male 117 (31.6%), female 240 (64.9%), unspecified gender 13 (3.5%)]. Daily workflow was significantly impacted for all strata of health care workers as shown in Figure 1. Overall responses to the Likert-scale questions are displayed in Figure 2. Most respondents (200, 54%) strongly agreed or agreed that they had increased anxiety as a result of the pandemic. Only 115 (31.1%) felt overwhelmed. Women felt more overwhelmed (45.6% vs. 27.3%, X2 (1, N=273)=8.67, p=0.003), had more work place related anxiety (70.7% vs. 56%, X2 (1, N=292)=5.953, p=0.015) and suffered more sleep disruption (52% vs. 39%, X2 (1, N=312)=4.91, p=.027) than men. Dressing patterns when coming in and out of work were changed by 281 (75.9%), of which 183 (65.1%) were female.

Figure 1.

Perception on the Impact of COVID-19 on Daily Workflow

Figure 2.

Responses to the 13 Likert-Scale Questions

Among the respondents, 159 (42.9%) were worried about dying from COVID-19, working in healthcare was less favorable for 94 (25.4%) respondents, and 274 (74%) respondents knew of another hospital worker who had contracted COVID-19. Hospital administration was considered to be supportive by 243 respondents (84.1%) irrespective of occupation status (Table 1). Those who knew of a sick coworker did not consider working in healthcare as less favorable because of this knowledge, when compared to those who did not (48% vs. 37%, X2 (1, N=233=2.02, p=0.155).

Table 1.

Responses on feeling supported from the hospital administration by occupation status

| Occupation | Hospital Administration Was Supportive (N= 289) | |

|---|---|---|

| Agree N = 243 (84.1 %) | Disagree N = 46 (15.9 %) | |

| Nurse | 47 (83.9%) | 9 (16.1%) |

| Resident | 38 (90.5) | 4 (9.5) |

| Fellow | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) |

| Attending Physician | 64 (84.2) | 12 (15.8) |

| Respiratory Therapist | 30 (85.7) | 5 (14.3) |

| NP/PA | 5 (100) | 0 |

| Social Worker | 6 (54.5) | 5 (45.5) |

| Dietitian | 3 (100) | 0 |

| Physical Therapy | 8 (100) | 0 |

| Occupational Therapy | 10 (83.3) | 2 (16.7) |

Among the residents and fellows, 36 (56.2%) stated that the pandemic had negatively impacted their learning opportunities. With regards to support from residency and fellowship programs, and 34 (53.1%) of residents and fellows (excluding neutral responses) felt that they were sufficiently supported by their program.

Discussion

This is one of the first studies in an academic setting in the U.S. to investigate the psychosocial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on multiple disciplines of frontline healthcare workers in the U.S. It clearly reveals significant psychosocial strain among most healthcare workers. It highlights certain areas that could be targets for mitigation efforts. At least a third of respondents were overwhelmed, anxious, and worried about dying, but despite these negative feelings, a majority felt that the hospital management was supportive. A prior study in 2016 by Khalid et al. that evaluated impacts of the MERS-CoV epidemic showed that personal safety and well-being of colleagues were significant concerns that were mitigated by support from hospital management for infected colleagues.4 In our study about a quarter of the respondents felt that working in healthcare was no longer favorable. This is higher than reported in prior investigation in SARS outbreak.7 Significant work-related stress during a global pandemic is inevitable among frontline healthcare workers, fueled by increased work demands, safety concerns, limited resources, and even media frenzy. In a recent systematic review, there was a paucity of studies on interventions to support mental well-being of health care workers.29 Table 2 provides a summary of methods, sample characteristics, results, and limitations of other studies published in peer-reviewed journals that assessed stress and other psycho-social well-being of health care workers during the current COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 2.

Summary of recent studies assessing health care worker’s psycho-social stress during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Study authors, Country | Methods | Sample Characteristics | Key Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang Y, et al., Sudan 8 | Quarterly assessment using PSS-10, GAD-7 and PHQ-9. | 47 HCWs in a UN Level II peacekeeping field hospital, including physicians, nurses, technicians/pharmacists. 70.2% male; mean age 38.3 years. Out-patient, inpatient, emergency, and lab/radiology/pharmacy settings. | Elevated mental stress noted among all HCWs after the outbreak. The threat of COVID-19 infection, delays in annual rotation of medical staff among Un hospitals and family-related concerns were the main stressors. | Small sample size, single hospital, unique resource limited circumstances of UN field hospital. |

| Magnavita N, et al., Italy 9 | ERI questionnaire, organizational justice with the Colquitt Scale, insomnia with SCI, and mental health with GADS. | 90 anesthesiologists directly caring for COVID-19 pts. 58.1% participation rate; 52.2% female; 76.7% were < age 35 years. Most without a partner or children or dependent relatives. 23.3% lacked social support, 23.3% reported unprotected exposure to COVID-19. | 71.1% had increased stress, 36.7% reported insomnia, 27.8% had anxiety and 51.1% had depression. Efforts towards work significantly correlated with depressive symptoms (r = 0.396). | Small sample size, single hospital setting. Only surveyed anesthesiologist. |

| Arnetz JE, et al., U.S.A 10 | An 85-item research questionnaire assessed demographics, work-factors, patient contact experiences, emergency preparedness, PPE, fear, and mental wellbeing. | 695 nurses in Michigan, 94.3% female. 69.0% > 10 years of experience. 52.7% inpatient/hospital setting. 82.4% had contact with COVID-19 patients at least once, 22% were in contact daily. | Stress was related to: workplace in 51.21% e.g., co-worker relationships, perceived administrative failings related to supplies and training, fear of infection in 29.67%, COVID-19 illness/death of patients/coworkers/loved ones in 38.90%, from limited PPE supplies, unclear guidelines, and physical discomfort in 21.98%, and the unknowns (scientific/social) in 22.64%. | Low response rate (685 of ~18,300 eligible), single U.S. state. |

| Soto-Rubio A, et al. Spain 11 | Cross-sectional questionnaires on a convenience sample of nurses. TMMS-24 for emotional intelligence; UNIPSICO Battery for psychosocial risks; FEWS for emotional work; CESQT for burnout syndrome. | 125 Spanish nurses completed survey; 80% response rate. 79.1% female. 43% temporary workers, 57% permanent workers. | Emotional intelligence protected against burnout, psychosomatic complaints, and a preserved job satisfaction, but it could be a risk factor for certain psychosocial risks, such as interpersonal conflicts or lack of organizational justice. | Small sample size. Difficult to establish causal relationships of variables. Limited to one city in Spain. Nurses only. |

| Haravuori H, et. Al. Finland 12 | Initial results of prospective cohort study. Assessed demographics, MHI-5, ISI, PHQ-2, PC-PTSD-5, and OASIS symptom rating scales, work experiences, changes in daily work, attitudes toward COVID-19 patients, and the need for psychosocial support. | 4804 Helsinki University Hospital HCWs completed survey (19% response rate). 62.4% were nurses, 8.9% were physicians, 7.9% special personnel (including psychologists, social workers), 20.9% other (non-healthcare) personnel. 87.5% female. | 43.4% reported traumatic COVID-19 pandemic-related events, 83.3% had no distress per MHI-5. 82.4% experienced changes at work; 16.3% felt the need for psychosocial support. 43% reported insomnia. 32.2% reported depression. 19.9% had anxiety due to fear of COVID-19 at workplace. | Low response rate. Single center study. |

| Milgrom Y, et al., Israel 13 | Electronic questionnaire survey of hospital workers assessing demographics, attitudes about COVID-19, and present anxiety state (STAI-S). | 1570 HCWs (24% response rate). (Dentists, physicians, nurses, research staff, office staff, lab workers, social workers, psychologists, etc.) 71.7% female. | 33.5% had anxiety. Being a resident physician/nurse/female and having COVID-19 risk factors were associated with clinical anxiety, but not workplace. The most stress was from a fear of infecting their families. | Low response rate may overestimate anxiety. Single health system. |

| Delgado-Gallegos JL, et al. Mexico 14 | Electronic questionnaire survey: 36-item COVID-19 stress scales (CSS) adapted for Spanish speakers; assesses stress and anxiety symptoms in daily life. | 104 HCWs in NE Mexico, various cities/towns. Physicians, medical students, nurses, and others working in a variety of health care settings (emergency, intensive care, obstetrics, primary care, pediatrics, etc). 57% male. | Normal levels of stress have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fear of being an asymptomatic carrier is a concern. | Small sample size of HCW from many different work areas and specialties. |

| Sorokin MY, et al. Russia 15 | Online survey consisting of two phases (3/30/20 - 4/5/20 and 5/4/20 - 5/10/20) using PSM-25 | 1800 HCWs from across all Russian federal districts and federal cities. 81.1% female. Physicians, nurses, & paramedics were surveyed. Numerous specialties represented. | Physicians were more stressed than nurses and paramedics. Direct contact with COVID-19 infection is associated w/significant increase in stress among medical personnel. | Most were psychiatrists Region of residence and current level of epidemic process not considered. |

| Awano N, et al. Tokyo, Japan 16 | Survey on anxiety, depression, resilience, fear of infection/death; isolation/unreasonable treatment; motivation/escape behavior at work were assessed using GAD-7, CES-D, and 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale. | 848 HCWs at the Japanese Red Cross Medical Center completed survey (43.2% response rate). 12.3% physicians, 54.4% nurses, 21.7% other medical staff, 11.7% office workers. 74.9% female. | 10% developed moderate-to-severe anxiety d/o; 27.9% developed depression. Being a nurse and high total GAD-7 scores were risk factors for depression. Older workers and those w/higher resilience were less likely to develop depression than others. | Single center. Suboptimal response rate. One-time survey--no longitudinal data. |

| Tan BYQ, et al. Singapore 17 | Self-administered questionnaire assessed depression, stress, anxiety, and PTSD among all HCWs. Demographics, medical history, DASS-21, IES-R. | 470 HCWs at two institutions caring for COVID-19 patients in Singapore, (94% response rate). 68.3% female, 28.7% physicians, 34.3% nurses; others included allied HCWs, technicians, clerical staff, administrators, and maintenance workers. | 14.5% screened positive for anxiety; 8.9% for depression; 6.6% for stress; 7.7% for clinical concern of PTSD. Anxiety was higher among nonmedical HCWs than medical HCWs (20.7% vs. 10.8%). | Self-report not verified with medical records, no socio-economic status and done only in Singapore. |

| Chew NWS, et al. Singapore & India 18 | Self-administered questionnaire assessed demographics, medical history, physical symptom prevalence in last month, DASS-21, IES-R. Prevalence of and associations between physical symptoms and psychological outcomes of depression, anxiety, stress, and PTSD were evaluated. | 906 HCWs included doctors, nurses, allied HCW, administrators, clerical staff, maintenance workers from 5 major tertiary hospitals in Singapore and India involved in care of COVID-19 pts (90.6% response rate). 64.5% female. 22.6% had preexisting comorbidities. 39.2% nurses, 29.6% physicians, 10.6% allied HCWs. | 5.3% had moderate to severe depression; 8.7% for moderate to extremely severe anxiety; 2.2% for moderate to extremely severe stress; 3.8% for moderate to severe levels of psychological distress. 33.4% of participants reported > 4 symptoms. Most common was headache (32.3), Depression, anxiety, stress, and PTSD were associated with symptoms in the previous month and symptoms were associated w/higher mean scores in IES-R, DASS Anxiety, Stress and Depression subscales. | Cross-sectional design unable to establish causality of stress to symptoms. Socioeconomic and educational status not considered. |

| Si MY, et al. China 19 | Cross-sectional survey assessed demographics, general health status, IES-6, DASS, and related psychological factors like perceived threat, social support, and coping strategies. | 863 HCWs from 7 provinces in China completed the questionnaire (76.0% response rate). 70.7% female. 43.7% doctors, 24.4% nurses 31.9% other HCWs. 25.6% had ever been quarantined or isolated during the outbreak. 16.8% were frontline medical workers. 74.0% were highly concerned about the epidemic. | 40.2% - significant PTSD symptoms; 97.9% - at least one PTSD symptom; 13.6% had depression symptoms; 13.9% had anxiety; 8.6% had stress. Perceived threat and passive coping strategies were positively correlated to PTS and DASS scores. Perceived social support and active coping strategies were negatively correlated to DASS scores. Nurses more likely to be anxious than other HCWs. | Study conducted in China when it was the country most affected by COVID-19, limiting generalizability. |

| Xing LQ, et al. Jinan, China 20 | Cross-sectional survey among frontline HCWs assessed demographics, and stress using self-rating anxiety scale (SAS), self-rating depression Scale (SDS). | 309 HCWs working in 4 isolation wards and 1 fever clinic set up for COVID-19 (100% response rate). 11.3% physicians, 88.7% nurses. 97.4% female. | 28.5% screened positive for anxiety; 56.0% screened positive for depression. Age 30 or younger, age >30 to 45, and worrying about inadequate disinfection measures were all independently associated with both anxiety and depression. | Small sample size, single center. Physicians and nurses only. |

| Romero CS, et al., Spain 22 | National cross-sectional 45-item survey assessed a psychological stress and adaptation work score (PSAS score) via Healthcare Stressful Test, Coping Strategies Inventory, Font-Roja Questionnaire and TMMS | 3109 HCWs across Spain in different health care settings including physicians (subspecialties), nurses, respiratory and other therapists, support staff, administrators. | Respiratory Medicine perceived highest psychosocial impact followed by geriatrics. The stress perceived was parallel to the number of cases per 100 000 people. | Unknown prior stress levels and > 66% from a second least-affected area leading to underestimation |

| Kang L, et al., China 23 | Anonymous self-rated questionnaire assessed demographics, mental health, risks of COVID-19 exposure, access to mental healthcare and self-perceived health status compared to pre-COVID period | 994 HCWs, Physicians 18.4%, nurses 81.6%, females 85.5%. | Mental health disturbances: 36.9% had subthreshold, 34.4% mild, 22.4% moderate, and 6.2% severe. The burden fell particularly heavily on young women. | Self-report Cross-sectional design |

Abbreviations: COVID-19 - Coronavirus disease 2019, CES-D – Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression, DASS-21 – Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale - 21 items, ERI – Effort Reward Imbalance, FEWS – Frankfurt Emotion Work Scale, GAD – Generalized Anxiety Disorder, GADS- Goldberg Anxiety Depression scale, HCW – Health Care Worker, IES (-R) – Impact of Event Scale (-revised), ISI – Insomnia severity Index, MHI – Mental Health Inventory,, OASIS – Outcome and Assessment Information Set, PHQ – Patient Health Questionnaire, PPE – Personal Protective Equipment, PSM-25 – Psychological Stress Measure (25 item scale), PSS-10 – Perceived Stress Scale – 10 item, PTSD – Post-traumatic stress disorder, PC-PTSD-5 – Primary Care PTSD screen for DSM 5, SAS - Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), SCI – Sleep Condition Indicator, SDS – Self Rating Depression Scale, STAI-S – State Trait Anxiety Inventory Scale, TMMS – Trait Meta Mood Scale, UN – United Nations, UNIPSICO - Unidad de Investigación Psicosocial de La Conducta Organizacional, CESQT - Cuestionario para la evaluación del síndrome de quemarse por el trabajo,

In another study assessing the impact of SARS on academic physicians in three hospitals, Grace et al. found that 9.3% of respondents were reevaluating their career choice.7 Though it is difficult to draw conclusions from one study, in recent years, increasing burnout among healthcare professionals remains a significant concern.30 Thus, it is crucial to have support systems that prevent further burnout among healthcare workers. Furthermore, in rapidly spreading communicable disease pandemics such as COVID-19, health care workers are at particularly high-risk for contracting the disease, resulting in a shortage of healthcare workers and adding further constraints to health care systems. Hence, addressing these concerns is of paramount importance.

The majority of residents and fellows reported disruptions in their learning opportunities. Most of the disruptions were likely related to changes in the workflow within the hospital as well as suspension of rotations and decrease in patient volumes and diversity of clinical cases due to containment measures. Other possible considerations include being unable to attend teaching conferences in their usual venues, changes in rounding structure, and inability to go to national or regional conferences. This has also been reported in training programs across the globe in this COVID-19 pandemic.31–34 This fuels the need to find innovative ways to help training programs to continue the mandate to train the next generation of healthcare workers.

While other survey studies have evaluated the impact of COVID-19 on specific sub-specialties, this was the first study that surveyed a broad range of healthcare professionals representing most of the essential disciplines of health care workers involved in academic U.S. hospitals.35–37 We limited the number of questions to fit their busy work-schedule during COVID-19 pandemic, yet have gathered information on multiple aspects of healthcare worker’s welfare and thus considered fairly representative of key areas highlighted in prior studies.

This was a single academic center study and may not be applicable to other academic or non-academic medical centers. Other limitations include lack of an externally validated survey instrument, and insufficient numbers in certain sub-groups of healthcare professionals to make robust comparisons. Last but not least, the volume of COVID-19 patients at the time of the survey in our rural mid-west U.S. was smaller compared to the then hard-hit areas such as New York City and Seattle, Washington.

Conclusions

A significant proportion of healthcare workers across multiple disciplines as well as training physicians perceived increased anxiety, fear of dying, and disruptions in their workflow from the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, it has had an adverse impact on medical training/education. These findings emphasize the importance of being prepared to support frontline workers and trainees at times of widespread crisis. Health care provider well-being should be an essential component of pandemic planning.

Supplementary Information

Supplement 1.

COVID 19 Psycho-social Impact Survey Questionnaire responses from residents, fellows, attendings, nurses and respiratory therapists.

| Questions | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted my daily workflow | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| COVID-19 pandemic has offered me an opportunity to observe emergency preparedness in our hospital | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Learning opportunities have decreased because of the COVID-19 pandemic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Hospital Administration is supportive at work at this time | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Residency and Fellowship programs is supportive at this time | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| My co-workers are considerate and supportive at work at this time | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| My family and friends are considerate and supportive at this time | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I feel overwhelmed at work due to the COVID-19 pandemic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Employment in healthcare has become less favorable for me because of the COVID-19 pandemic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| My sleep is affected by the COVID-19 pandemic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am more anxious at work because of the COVID-19 pandemic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| My anxiety is related to the panic among the public than my work environment | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I would prefer to take time off work at this time | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I would want more information about the pandemic from the hospital leadership | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am worried about contracting COVID-19 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Yes | No | |

|---|---|---|

| Did you change your dressing habits when coming or leaving work due to the COVID-19? | ||

| Do you know of any fellow worker who has contracted the COVID-19? |

Footnotes

Tinashe Maduke, MD, MPH, is a Clinical Fellow, Department of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Environmental Medicine, University of Missouri-Columbia, (UMC), Columbia, Missouri. Armin Krvavac, MD, is Assistant Professor, Department of Internal Medicine - Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, Missouri. James Dorroh, BA, is a second-year Medical Student, Department of Medicine, UMC. Ambarish Bhat, MD, is Assistant Professor, Department of Radiology, UMC. Hariharan Regunath, MD, (above), is a Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine – Divisions of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Infectious Diseases-UMC.

Disclosure

No funding was necessary for this study.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Cases in the US. [Accessed Aug 28, 2020]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html.

- 2.American Hospital Association (AHA) Hospitals and Health Systems Face Unprecedented Financial Pressures Due to COVID-19. AHA. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(5):302–311. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khalid I, Khalid TJ, Qabajah MR, Barnard AG, Qushmaq IA. Healthcare Workers Emotions, Perceived Stressors and Coping Strategies During a MERS-CoV Outbreak. Clin Med Res. 2016;14(1):7–14. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2016.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SM, Kang WS, Cho AR, Kim T, Park JK. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;87:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koh D, Lim MK, Chia SE, et al. Risk perception and impact of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) on work and personal lives of healthcare workers in Singapore: what can we learn? Med Care. 2005;43(7):676–682. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000167181.36730.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grace SL, Hershenfield K, Robertson E, Stewart DE. The occupational and psychosocial impact of SARS on academic physicians in three affected hospitals. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(5):385–391. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.5.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Xiang D, Alejok N. Coping with COVID-19 in United Nations peacekeeping field hospitals: increased workload and mental stress for military healthcare providers. BMJ Mil Health. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmjmilitary-2020-001642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magnavita N, Soave PM, Ricciardi W, Antonelli M. Occupational Stress and Mental Health among Anesthetists during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17218245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnetz JE, Goetz CM, Arnetz BB, Arble E. Nurse Reports of Stressful Situations during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Qualitative Analysis of Survey Responses. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17218126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soto-Rubio A, Giménez-Espert MDC, Prado-Gascó V. Effect of Emotional Intelligence and Psychosocial Risks on Burnout, Job Satisfaction, and Nurses’ Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haravuori H, Junttila K, Haapa T, et al. Personnel Well-Being in the Helsinki University Hospital during the COVID-19 Pandemic-A Prospective Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milgrom Y, Tal Y, Finestone AS. Comparison of hospital worker anxiety in COVID-19 treating and non-treating hospitals in the same city during the COVID-19 pandemic. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2020;9(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s13584-020-00413-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delgado-Gallegos JL, Montemayor-Garza RJ, Padilla-Rivas GR, Franco-Villareal H, Islas JF. Prevalence of Stress in Healthcare Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Northeast Mexico: A Remote, Fast Survey Evaluation, Using an Adapted COVID-19 Stress Scales. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorokin MY, Kasyanov ED, Rukavishnikov GV, et al. Stress and Stigmatization in Health-Care Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62(Suppl 3):S445–s453. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_870_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Awano N, Oyama N, Akiyama K, et al. Anxiety, Depression, and Resilience of Healthcare Workers in Japan During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak. Intern Med. 2020;59(21):2693–2699. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.5694-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan BYQ, Chew NWS, Lee GKH, et al. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(4):317–320. doi: 10.7326/M20-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Si MY, Su XY, Jiang Y, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on medical care workers in China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):113. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xing LQ, Xu ML, Sun J, et al. Anxiety and depression in frontline health care workers during the outbreak of Covid-19. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020968119. 20764020968119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsamakis K, Rizos EJ, Manolis A, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on mental health of healthcare professionals. Exp Ther Med. 2020;19(6):3451–3453. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.8646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romero CS, Catalá J, Delgado C, et al. COVID-19 Psychological Impact in 3109 Healthcare workers in Spain: The PSIMCOV Group. Psychol Med. 2020:1–14. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720001671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giorgi G, Lecca LI, Alessio F, et al. COVID-19-Related Mental Health Effects in the Workplace: A Narrative Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. The UK EQUATOR Centre; [Accessed Nov 29, 2020]. 2020. https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/a-guide-for-the-design-and-conduct-of-self-administered-surveys-of-clinicians/. Updated Sep 26, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burns KE, Duffett M, Kho ME, et al. A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. Cmaj. 2008;179(3):245–252. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollock A, Campbell P, Cheyne J, et al. Interventions to support the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic: a mixed methods systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;11:Cd013779. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reith TP. Burnout in United States Healthcare Professionals: A Narrative Review. Cureus. 2018;10(12):e3681. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang ZC, Ooi SBS, Wang W. Pandemics and Their Impact on Medical Training: Lessons From Singapore. Acad Med. 2020 doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim CS, Lynch JB, Cohen S, et al. One Academic Health System’s Early (and Ongoing) Experience Responding to COVID-19: Recommendations From the Initial Epicenter of the Pandemic in the United States. Acad Med. 2020 doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adebisi YA, Agboola P, Okereke M. COVID-19 Pandemic: Medical and Pharmacy Education in Nigeria. International Journal of Medical Students 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvin MD, George E, Deng F, Warhadpande S, Lee SI. The Impact of COVID-19 on Radiology Trainees. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201222. 201222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caruana EJ, Patel A, Kendall S, Rathinam S. Impact of coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) on training and well-being in subspecialty surgery: A national survey of cardiothoracic trainees in the United Kingdom. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khanna RC, Honavar SG, Metla AL, Bhattacharya A, Maulik PK. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on ophthalmologists-in-training and practising ophthalmologists in India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(6):994–998. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1458_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osama M, Zaheer F, Saeed H, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on surgical residency programs in Pakistan; A residents’ perspective. Do programs need formal restructuring to adjust with the “new normal”? A cross-sectional survey study. Int J Surg. 2020;79:252–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement 1.

COVID 19 Psycho-social Impact Survey Questionnaire responses from residents, fellows, attendings, nurses and respiratory therapists.

| Questions | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted my daily workflow | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| COVID-19 pandemic has offered me an opportunity to observe emergency preparedness in our hospital | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Learning opportunities have decreased because of the COVID-19 pandemic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Hospital Administration is supportive at work at this time | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Residency and Fellowship programs is supportive at this time | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| My co-workers are considerate and supportive at work at this time | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| My family and friends are considerate and supportive at this time | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I feel overwhelmed at work due to the COVID-19 pandemic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Employment in healthcare has become less favorable for me because of the COVID-19 pandemic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| My sleep is affected by the COVID-19 pandemic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am more anxious at work because of the COVID-19 pandemic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| My anxiety is related to the panic among the public than my work environment | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I would prefer to take time off work at this time | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I would want more information about the pandemic from the hospital leadership | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am worried about contracting COVID-19 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Yes | No | |

|---|---|---|

| Did you change your dressing habits when coming or leaving work due to the COVID-19? | ||

| Do you know of any fellow worker who has contracted the COVID-19? |