Abstract

The emergence of a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2, causing coronavirus disease 2019 or COVID-19) has disrupted the US medical care system. Telemedicine has rapidly emerged as a critical technology enabling health care visits to continue while supporting social distancing to reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission among patients, families, and clinicians. This model of patient care is being utilized at major cancer centers around the USA—and tele-oncology (telemedicine in oncology) has rapidly become the primary method of providing cancer care. However, most clinicians have little experience and inadequate training in this new form of care delivery. Because many practicing oncology clinicians are not familiar with telemedicine technology and the best practices for virtual communication, we strongly believe that training in this field is essential. Utilizing best practices of communication skills training, this paper presents a brief tele-oncology communication guide (Comskil TeleOnc) to address the timely need to maximize high-quality care to patients with cancer. The goal of the Comskil TeleOnc Guide is to recognize, elicit, and effectively respond to patients’ medical needs and concerns while utilizing empathic responses to communicate understanding, alleviate distress, and provide support via videoconferencing. We recommend five strategies to achieve the communication goal outlined above: (1) Establish the clinician-patient relationship/create rapport, (2) set the agenda, (3) respond empathically to emotions, (4) deliver the information, and (5) effectively end the tele-oncology visit. The guide proposed in this paper is not all-encompassing and may not be applicable to all health care institutions; however, it provides a practical, patient-centered framework to conduct a tele-oncology visit.

Keywords: Communication skills training, Coronavirus, Covid-19, Telehealth, Telemedicine, Tele-oncology

The emergence of a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2, causing coronavirus disease 2019 or COVID-19) has disrupted the US medical care system [1]. Although the use of telemedicine had preceded the COVID-19 pandemic, it has rapidly emerged as an essential technological tool in the current era. Telemedicine enables health care visits to continue effectively while supporting social distancing to reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission among patients, families, and clinicians [2–4]. Telemedicine (or telehealth) is defined by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services as “the use of electronic information and telecommunications technologies to support and promote long-distance clinical health care, patient and professional health-related education, and public health and health administration” [5]. Telemedicine technologies include telephone, videoconferencing, internet, store-and-forward imaging, streaming media, and terrestrial and wireless communications [5] with videoconferencing being the most frequently used telemedicine technology [4–6].

As the nations around the world, and in particular the USA, deal with managing patients with COVID-19 and decreasing the spread of infection, telemedicine has become the modality of choice to assist patients with various medical needs, including cancer care. In the last decade, for example, tele-oncology (telemedicine in oncology) has gained traction and found a prominent role in medical, surgical, and radiation oncology, as well as in bone marrow transplant and palliative care services [6, 7]. Sabesan [4] describes medical oncology models for tele-oncology services that include face-to-face initial appointments followed by video visits for consultation and supervision of administration of chemotherapeutic agents and oral medication. Additionally, tele-oncology services can benefit clinicians and patients in rural practices, enabling them to have greater access to a cancer center’s multidisciplinary team through methods such as virtual tumor group meetings with patient case presentations and discussions [4]. Similarly, tele-oncology has found applicability in patient support services such as psychiatry and nutrition counseling [7]. Recently, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s Tobacco Treatment Program rapidly scaled up individual and group telehealth treatment visits, showing a higher level of initial patient engagement with telehealth tobacco treatment visits, compared to in-person visits for cancer patients [8]. Until the COVID-19 outbreak, the use of tele-oncology was limited primarily to patients in rural and underserved areas and its use for mainstream oncology care was minimal [6].

Systematic reviews [9, 10] assessing effectiveness of tele-oncology have concluded that tele-oncology via videoconferencing is effective for use in the clinical care of oncology patients due to factors such as convenience, reduced travel time and costs, reduced appointment wait times, enhanced access to care, and overall ease of use. However, reports on other patient-reported outcomes have been mixed or non-existent [9, 11–13]. For instance, patient barriers to engaging in tele-oncology via videoconferencing include difficulty (or reluctance) to communicate with providers using digital platforms such as webcams and videos [13], and the experience of emotional distance between patients and clinicians [12]. Thus, a focus on improving communication, especially when dealing with cancer diagnoses and treatments between clinicians and patients when using tele-oncology, is warranted.

Given the current circumstances, many clinicians have suddenly been faced with tele-oncology care provision without adequate training. Because few practicing oncology clinicians have previously utilized telemedicine technology, training is essential for familiarization with technical components of telemedicine as well as for adjustment to a virtual method of communicating sensitive medical information [6]. A teleconsultation is far more than a simple FaceTime® or Doximity call with a patient, and thus requires some level of training. Providing clinicians with key communication skills specifically for telemedicine is essential to establishing rapport, maximizing engagement, and conducting a comprehensive patient history and virtual exam [14]. This paper addresses this timely and critical need to enhance clinician readiness to provide high-quality care to patients with cancer by presenting a brief tele-oncology communication (Comskil TeleOnc) guide that utilizes the best practices of an adapted communication skills training [15].

Communicating Effectively via Tele-oncology (Comskil TeleOnc)

Based on Memorial Sloan Kettering’s Comskil Conceptual Model, the Comskil TeleOnc Guide was developed to assist clinicians with limited training in tele-oncology [15]. This conceptual model describes four overarching components that drive the communication interaction between the clinician and patient/families: (i) the communication goal, (ii) communication strategies, (iii) communication skills, and (iv) process tasks. The first component is the communication goal (i.e., the intended outcome of a medical consultation/interaction). The goal is achieved using communication strategies (a priori/sequential plans that direct communication behavior towards realization of the goal). Strategies, in turn, are achieved with communication goals (discrete verbal utterances) and process tasks (verbal and non-verbal behaviors that create an appropriate environment for effective communication).

While the majority of communication goals, strategies, skills, and process tasks described in this manuscript do not significantly differ from face-to-face clinician-patient consultations, there are some skills/process tasks that are unique to tele-visits (e.g., ensuring privacy, technology check, and make technology back-up plan), whereas others are the same as in face-to-face interactions (e.g., declare agenda, invite agenda, and acknowledge). The sequence of skills recommended and the way in which skill use is exemplified in this manuscript provides a resource for clinicians on effective communication via tele-oncology.

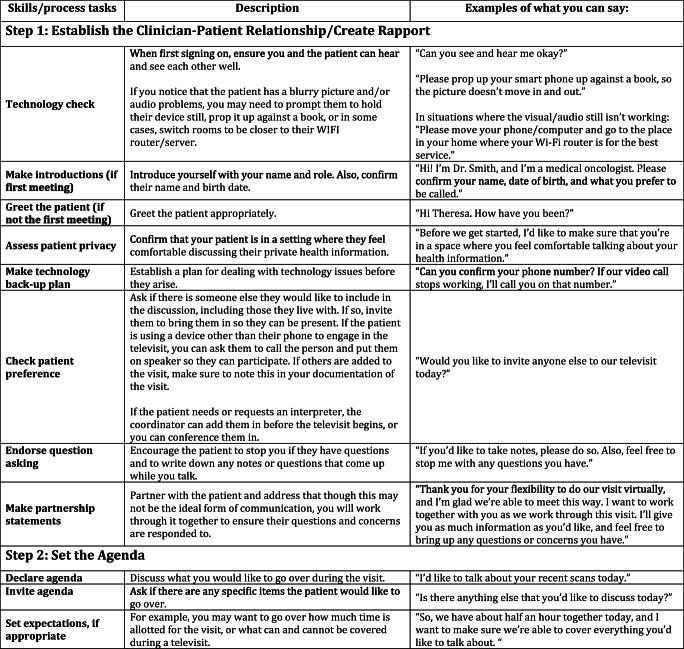

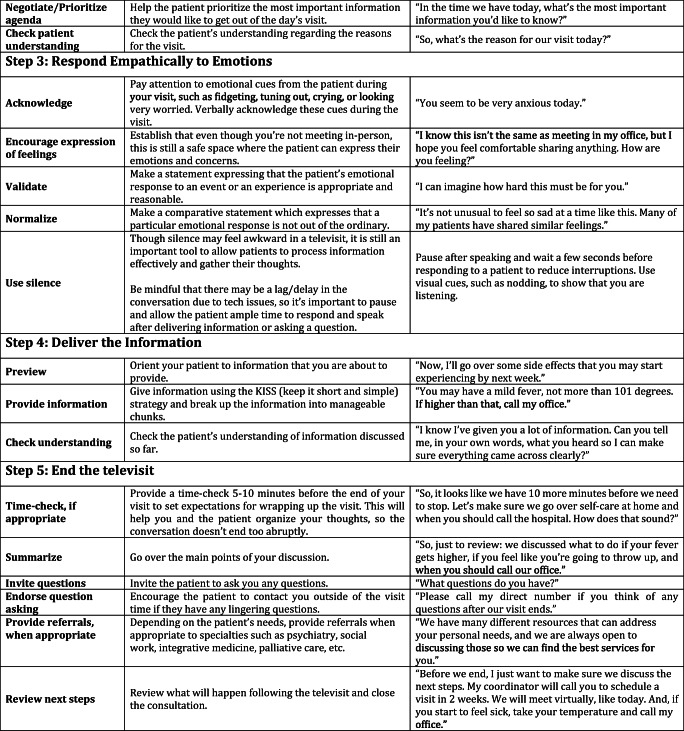

The goal of the Comskil TeleOnc Guide is to recognize, elicit, and effectively respond to patients’ medical needs and concerns while utilizing empathic responses to communicate understanding, alleviate distress, and provide support via videoconferencing. Five strategies are recommended for achieving the communication goal and described next (see Table 1 for the Comskil TeleOnc Guide). These strategies include skills and process tasks that should be used throughout the conversation. Examples of each are provided for clarity.

Table 1.

A Guide for Communicating Effectively via Tele-Oncology

In strategy 1, the clinician establishes the clinician-patient relationship and creates rapport with the patient. The tele-oncology visit should begin with a technology check so that the clinician can ensure that the patient can hear and see the clinician well (and vice versa) and enables the patient to appropriately engage in the consultation. This is followed by introductions (if this is the first visit) or greetings (if the visit is a follow-up visit), as needed. It is also important for the clinician to assess patient privacy by confirming that the patient is in a setting where they feel comfortable discussing their private health information. Given the reliance on technology, it is recommended that the clinician has a technology back-up plan (e.g., telephone number, alternate platform) in mind that ensures a process for dealing with technology issues before they arise. Next, it is helpful to check a patient’s preference for people they would like to include in the discussion, including those whom they live with as well as those outside of their home with whom they would like to conference in. Within rapport formation, it is also important for the clinician to endorse question asking during the visit and encourage the patient to pause the conversation if they have questions. Clinicians should also continue to encourage patients to take notes or write down questions that come up during the conversation. Finally, partnership statements (e.g., “we will get through this together” and “we will work together to make this meeting helpful”) allow for alliance formation between the clinician and the patient and can provide support.

Strategy 2 involves setting an agenda for the tele-oncology visit. In order to accomplish agenda setting, it is helpful for the clinician to declare their agenda and discuss items to be reviewed during the visit. It is also recommended to invite the patient’s agenda and ask if there are any specific items the patient would like to discuss. Additionally, the clinician should set expectations and review how much time is allotted for their visit. If the clinician is not able to address all of their and their patient’s agenda items, it is recommended that they negotiate and prioritize items to ensure the patient receives the most important information they need from the day’s visit. Finally, checking a patient’s current understanding of the reason for the visit can help the clinician structure the conversation and fill in knowledge gaps when appropriate.

Strategy 3 involves empathically responding to the patient’s emotion or experience and introduces core skills that should be interspersed throughout the interaction. This strategy includes skills such as acknowledge, validate, normalize, and encourage expression of feelings. These verbal acknowledgments of support and care during this difficult time are even more relevant in a post-pandemic world, especially given that in-person interactions are limited and some patients may be forced into more isolated settings with less social support. Though it can be difficult to assess a patient’s emotional state via a virtual platform, encouraging patients to verbally express their concerns and feelings is crucial to establishing rapport and trust in the patient-clinician relationship. Appropriate use of silence is also encouraged during a tele-oncology visit. Though silence may feel awkward at times, it is still an important tool to allow patients to process information effectively and gather their thoughts. Clinicians should also be mindful that there may be a lag or delay in the conversation due to technical issues, so it is important to pause and allow patients ample time to respond and speak after delivering information or asking a question.

Strategy 4 includes delivery of the key medical information. This can be accomplished by previewing the information before going into details to help orient the patient and assist in information organization. While the clinician provides information, we recommend using the KISS (keep it short and simple) strategy in addition to breaking up the information into manageable chunks. After provision of information, it is important to, again, check the patient’s understanding to ensure there are no misconceptions, misinformation, or misperception about the information discussed in the tele-oncology visit.

Lastly, strategy 5 involves ending the tele-oncology visit. It is recommended that clinicians provide a time-check roughly a few minutes before the end of the visit to set expectations for wrapping up. This will help the clinician and the patient organize their respective thoughts and will prevent an abrupt end to the conversation. After the time-check, it is helpful for the clinician to summarize the main points of the discussion and to invite questions from the patient. Clinicians should also endorse question asking, encouraging patients to contact them outside of the visit and provide contact information, especially if there are any lingering questions. Providing referrals to specialties such as psychiatry, social work, integrative medicine, and palliative care may be helpful for some patients, and the clinician must evaluate that on a case-by-case basis. The visit should end with a clear review of next steps, including what will happen following the tele-visit.

Discussion

This paper describes a newly developed Comskil TeleOnc Guide, curated by our team of communication experts and practicing oncology clinicians, and refined in partnership with colleagues from Telemedicine, Patient Experience, and other faculty members with substantial experience in providing tele-oncology care. Focusing on the utilization of communication skills, adapted from our educational programming based on our Comskil conceptual model, this guide maximizes care provision for patients via videoconferencing. As cancer care centers around the nation advance into an increasingly digital era, it is paramount that clinicians be prepared for conducting effective consultations via videoconferencing. The guide presented here is not all-encompassing or prescriptive, but rather keeps communication best practices in mind to provide a patient-centered framework for conducting a tele-oncology visit. Our aim in developing this communication guide is to provide direction to clinicians on how to more effectively communicate with their patients in a post-pandemic health care system. The long-term objective of the research team is to develop a virtual Comskil TeleOnc Coaching Intervention to improve quality of care related to clinician-patient communication and patient satisfaction in oncology care delivered via tele-oncology.

Acknowledgements

The study team would like to thank Dr. Jamie S. Ostroff, Dr. Nessa Coyle, Anna Boyko, Eoin Dawson, Sofia Fatalevich, Jennie Huang, Ruth Manna, and Laura Paloubis for their input on the Comskil TeleOnc Guide.

Funding

Research reported in this paper was supported in part by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (P30CA008748; PI: Dr. Craig Thompson).

Declarations

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hick JL, Hanfling D, Wynia MK, Pavia AT (2020) Duty to plan: health care, crisis standards of care, and novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. NAM Perspectives. Discussion paper. National Academy of Medicine. 10.31478/202003b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Calton B, Abedini N, Fratkin M. Telemedicine in the time of coronavirus. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2020;60:e12–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Telemedicine Association. Covid-19: policy update – 3.17.20. https://info.americantelemed.org/covid-19-cms-hhs-dea-updates-3-17-20. Accessed 25 May 2020

- 4.Sabesan S. Medical models of teleoncology: current status and future directions. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014;10:200–204. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). Telemedicine and Telehealth. https://www.healthit.gov/topic/health-it-initiatives/telemedicine-and-telehealth. Accessed 25 May 2020

- 6.Sirintrapun JS, Lopez AM. Telemedicine in cancer care. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:540–545. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_200141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satcher RL, Bogler O, Hyle L, Lee A, Simmons A, Williams R, Hawk E, Matin S, Brewster AM. Telemedicine and telesurgery in cancer care: inaugural conference at MD Anderson Cancer Center. J Surg Oncol. 2014;10:353–359. doi: 10.1002/jso.23652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotsen C, Dilip D, Carter-Harris L, O’Brien M, Whitlock CW, de Leon-Sanchez S, Ostroff JS (2020) Rapid scaling up of telehealth treatment for tobacco-dependent cancer patients during the COVID-19 outbreak in New York City. Telemed e-Health 1–10. 10.1089/tmj.2020.0194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Cleison K, Zurawel-Balaura L, Wong RKS. How effective is video consultation in clinical oncology? A systematic review. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:17–27. doi: 10.3747/co.v17i3.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larson JL, Rosen AB, Wilson FA. The effect of telehealth interventions on quality of life of cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Telemed e-Health. 2018;24:397–405. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2017.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fergus KD, McLeod DL, Carter W, et al. Development and pilot testing of an online intervention to support young couples’ coping and adjustment to breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2014;23:481–492. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coelho JJ, Arnold A, Nayler J, Tischkowitz M, MacKay J. An assessment of the efficacy of cancer genetic counselling using real-time videoconferencing technology (telemedicine) compared to face-to-face consultations. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2257–2261. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruse S, Clemens PK, Shifflett K, et al. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24:4–12. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16674087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yunus F, Gray S, Kevin C. Fox, et al. The impact of telemedicine in cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2016;27:e20508. doi: 10.1200/jco.2009.27.15_suppl.e20508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kissane DW, Bylund CL, Smita C. Banerjee, et al. Communication skills training for oncology professionals. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1242–1247. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]