Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to examine the survival rate of patients with different bone sarcomas and to investigate homogenous and heterogenous prognostic factors for different types of bone sarcomas.

Methods

This is a retrospective analysis of records from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Result (SEER) database. Clear information on the distant metastasis of cancer is provided in the SEER database for patients diagnosed between January 2010 and December 2016. Data for the four types of malignant bone sarcomas were extracted, including osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and chordoma. Patients with bone sarcomas originated from other sites, diagnosed at autopsy, or indicated in death certification were excluded. The overall survival was calculated for the entire cohort and across different bone sarcomas using the Kaplan–Meier method. A subgroup analysis of the different survival rates of four types of bone sarcomas in various levels of each variable was conducted and the differences were tested with the log‐rank test. Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was performed to determine the prognostic factors. Variables with P < 0.05 in the univariate Cox regression analysis were further analyzed using a multivariate Cox regression analysis. The prognostic factors in four groups of bone sarcomas were compared to determine the homogenous and heterogenous factors.

Results

A total of 4732 patients were included with a follow up of 25 (0–83) months. The mean age of patients was 39.7 ± 24.1 years. The 1‐year, 3‐year, and 5‐year overall survival rate for the entire cohort was 86.2% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 85.2%–87.2%), 70.5% (95% CI: 68.9%–72.1%), and 63.0% (95% CI: 61.2%–64.8%), respectively. Factors including age older than 40 years, higher grade, regional and distant stage, tumor in the extremities, T2 stage, bone and lung metastases, and non‐surgery were significantly associated with the poor survival of the entire cohort. The mean overall survival duration of patients with chordoma, chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma was 66.86 (95% CI: 64.06–69.66), 63.53 (95% CI: 61.81–65.25), 58.06 (95% CI: 55.49–60.62) and 54.91 (95% CI: 53.14–56.69) months, respectively. Compared with chordoma, the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI for patients with chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma were 1.30 (95% CI: 1.04–1.62; P = 0.023), 1.69 (95% CI: 1.33–2.14; P < 0.001), and 2.00 (95% CI: 1.61–2.48; P <0.001), respectively. Different bone sarcomas showed homogenous and heterogenous prognostic factors.

Conclusion

Different clinicopathological characteristics and prognoses were revealed in patients with osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and chordoma. The risk factors can potentially guide prognostic prediction and sarcoma‐specific treatment.

Keywords: Chondrosarcoma, Chordoma, Ewing sarcoma, Osteosarcoma, Prognosis

Patients with chordoma, chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma showed homogenous and heterogenous clinicopathological characteristics, survival rates, and prognostic factors, which can potentially guide sarcoma‐specific prediction and treatments.

Introduction

Compared with other common cancers, primary malignant bone sarcomas are rare, with a reported incidence of less than 1% 1 . Osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and chordoma are the most common types of bone malignancies. Among these bone sarcomas, osteosarcoma is the most common primary malignancy tumor. It has a bimodal age distribution, with adolescent and elderly patients showing dominant peaks 2 . With a similar incidence to osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma is the second most common bone tumor and accounts for one‐fifth of bone sarcomas, with a high incidence in patients aged 30 to 60 years 3 . Another common bone tumor is Ewing sarcoma. It typically occurs in children, adolescents, and young adults, with a median diagnostic age of 15 years 4 . Different from other bone sarcomas, most chordomas originate from the spine and skull base, with incidence rates from 0.18 to 0.84 per million persons per year 5 .

As malignant tumors in the musculoskeletal system, these bone sarcomas have significant influence on patients' lifespan and quality of life. The survival rates of patients and the related prognostic factors of these common bone sarcomas have been investigated over the past four decades. In a single institution, the 5‐year survival rate of 365 patients with osteosarcoma was 65% and further analysis showed reduced survival in patients with poor response to preoperative chemotherapy and in patients with distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis of osteosarcoma 6 . In a retrospective analysis of 127 pediatric patients with Ewing sarcoma, the 5‐year survival rate was 91.1% and no significant factors were identified for long‐term survival 7 . A retrospective analysis by the National Cancer Registry in Norway included a total of 311 patients with chondrosarcoma and the results showed that the subtype, location, and grade had significant influence on the local recurrence, metastasis, and disease‐specific survival 8 . Being female and of older age, and having increased tumor invasion, non‐total resection, recurrence and metastasis, and the dedifferentiated histological subtype were demonstrated to independently reduce the survival of patients with chordoma 5 . All these studies provided us useful information for patients with specific bone sarcomas. However, the separate results for specific bone sarcomas limits their usefulness for medical decision‐makers in the overall management of bone sarcomas.

Comparisons among various bone sarcomas are needed and have been previously attempted. A Japanese study investigated 3457 patients with osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma from 2006 to 2013 from a nationwide database called the Bone and Soft Tissue Tumor Registry. The results showed higher survival in adolescent and young adult patients than in elderly patients (≥65 years), regardless of whether the sarcoma was an osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, or Ewing sarcoma 9 . A Swiss study found that the 5‐year overall survival (OS) was 74% ± 6%, 85% ± 7%, and 86% ± 5% in patients with osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and chondrosarcoma, respectively 10 . No further comparison to determine related prognostic factors was undertaken in that study. In Bohman et al., the 5‐year survival rate was 65% in patients with chordoma and 81.8% in patients with chondrosarcoma in the skull 11 . Increasing age and tumor size were independently associated with reduced survival of chordoma, while older age, earlier decade of diagnosis, and mesenchymal subtype were significantly associated with reduced survival in patients with chondrosarcoma 11 . More bone malignancies were investigated in patients with non‐metastatic primary spinal osteosarcoma, chordoma, chondrosarcoma, or Ewing sarcoma, and, using Cox analysis, surgical resection was confirmed to be correlated with improved survival 12 .

These studies evaluated patient survival rates and revealed the predictors for single or couples of bone sarcomas in certain sites, such as the spine, the extremities, or the skull. However, no study has thoroughly investigated and compared the aforementioned bone sarcomas in one large population. Further understanding of their homogenous and heterogenous clinicopathological features and prognostic factors would assist clinicians in managing these sarcomas and in making better use of limited medical resources.

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database collects cancer incidence data from population‐based cancer registries across the USA. The database covers approximately 34.6% of the US population. The SEER database provides plentiful records of patients with bone sarcomas, which can be used to form a large cohort to investigate and compare these bone sarcomas. Thus, the present study collected and analyzed information from the SEER database with the three following purposes: (i) to evaluate the latest survival rates for osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and chordoma; (ii) to investigate the homogenous and heterogenous prognostic factors for specific bone sarcomas; and (iii) to assist the precise management of these bone sarcomas based on the above findings.

Materials and Methods

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) patients with malignant bone sarcomas, including osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and chordoma; (ii) patients with clear information on the metastatic sites and surgery treatments; (iii) vital status was recorded and the survival time was provided; (iv) the related variables to be analyzed were complete; and (v) the survival time and related prognostic factors were retrospectively analyzed. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) bone sarcomas originated from other sites; and (ii) bone sarcomas diagnosed at autopsy or indicated in death certification.

Data Source and Cohort Selection

All the data were obtained from the SEER program and organized using the SEER*Stat application (version 8.3.5). The database, named Incidence‐SEER 18 Regs Research Data + Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, Nov 2018 Sub (1975–2016 varying), was released on April 2019. To obtain enough detailed information about metastases, we collected all patients with malignant bone sarcomas (AYA site recode/WHO 2008 = 4 Osseous & Chondromatous Neoplasms) diagnosed between January 2010 and December 2016.

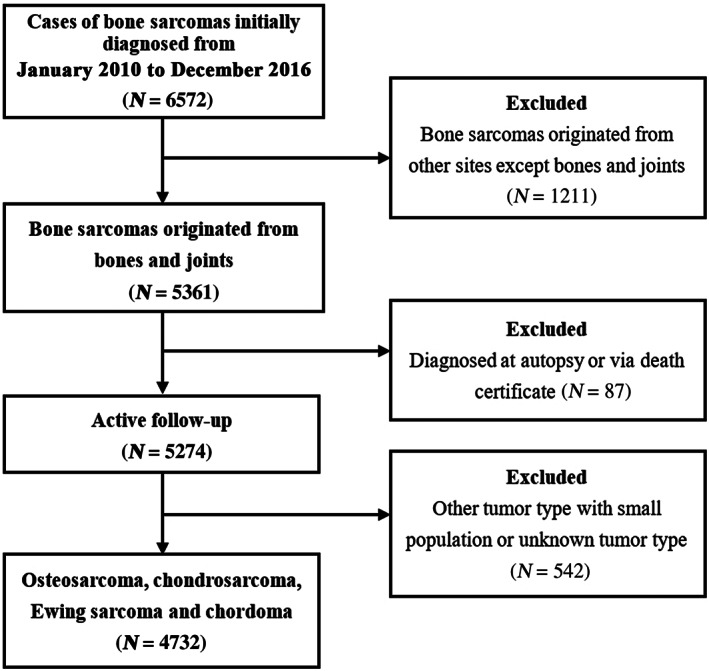

According to the inclusion criteria, the primary site was restricted to “bones and joints” (the ICD‐O‐3 topographical code: C40.0‐C41.9) in the SEER program. A total of 5274 patients who were actively followed up were selected initially. According to “AYA site recode/WHO 2008” in the SEER program, “4.1 Osteosarcoma,” “4.2 Chondrosarcoma,” and “4.3 Ewing tumor,” presented osteosarcomas, chondrosarcomas, and Ewing sarcomas, respectively, were selected from these 5274 patients. Because chordoma (defined using the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition morphological code 9370/3) took up a large proportion of the section “4.4 Other specified and unspecified bone tumors,” patients with chordoma were also included in our final cohort. A flowchart of the subjects' selection is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the patient selection for analyzing the prognostic factors of patients with bone sarcomas.

Outcome Measures

Overall Survival

The primary outcome of the survival analysis was the OS, which was defined as the time from the diagnosis of bone sarcomas to death by all causes. For subjects who had been lost to follow up prior to death, the last follow‐up time is usually calculated as time of death. The OS was used to reveal the survival condition of patients.

Survival Curve

The survival curve, which is a Kaplan–Meier curve, is the curve describing the survival condition of patient on time. It is important in the survival analysis and can be used to compare the survival difference of various cohorts.

Prognostic Factor

Prognostic factors are factors related to the survival of patients and can be used to predict the prognosis of patients. They are determined using Cox proportional hazard regression analysis. They can be used in the prediction of survival outcome and for clinical management.

Statistical Analysis

The survival time was described as mean ± standard deviation. The other variables included age, gender, marital status, race, insurance status, grade, location, stage, metastases, and surgery. They are categorical data and were presented as the number and the percentage (N, %). The Pearson χ2‐test was used to evaluate the difference between categorical variables. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method for entire and different bone sarcomas. Subgroup analysis of OS was conducted using the log‐rank test to determine the significance of differences among survival curves of the entire cohort and four different groups of patients with chordoma, chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma. Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was performed to determine the prognostic factors. Variables with P < 0.05 in the univariate Cox regression analysis were further analyzed using a multivariate Cox regression analysis. The prognostic factors in four groups of bone sarcomas were compared to determine the homogenous and heterogenous factors. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corporation, NY, USA) and all charts on survival were prepared using MedCalc 18.11.3 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). Two‐sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the Patients

According to the inclusion criteria, a total of 4732 eligible patients with bone sarcoma were included, with a follow‐up of 25 (0–83) months. Detailed information about the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for patients is shown in Table 1. Significant difference existed in age, gender, race, tumor grade, stage, location, TNM stage, and surgery for patients in the entire cohort. Homogenous and heterogenous performance was noticed in different types of bone sarcomas.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinicopathological characteristics of patients in the SEER database with malignant bone sarcomas diagnosed between January 2010 and December 2016

| Subject characteristics | Total cohort | Chordoma | Chondrosarcoma | Ewing sarcoma | Osteosarcoma | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | P | N (%) | P | N (%) | P | N (%) | P | N (%) | P | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| <18 | 1284 (27.1) | <0.001 | 22 (4.0) | 0.003 | 49 (3.1) | <0.001 | 440 (55.1) | <0.001 | 773 (42.9) | <0.001 |

| 18–40 | 1205 (25.5) | 96 (17.5) | 331 (20.9) | 259 (32.5) | 519 (28.8) | |||||

| >40 | 2243 (47.4) | 432 (78.5) | 1202 (76.0) | 99 (12.4) | 510 (28.3) | |||||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 2674 (56.5) | 0.002 | 310 (56.4) | 0.529 | 886 (56.0) | 0.002 | 478 (59.9) | 0.993 | 1000 (55.5) | 0.051 |

| Female | 2058 (43.5) | 240 (43.6) | 696 (44.0) | 320 (40.1) | 802 (44.5) | |||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Married | 1680 (35.5) | 0.120 | 306 (55.6) | 0.361 | 847 (53.5) | 0.737 | 107 (13.4) | <0.001 | 420 (23.3) | <0.001 |

| Unmarried | 2834 (59.9) | 215 (39.1) | 618 (39.1) | 671 (84.1) | 1330 (73.8) | |||||

| Unknown | 218 (4.6) | 29 (5.3) | 117 (7.4) | 20 (2.5) | 52 (2.9) | |||||

| Race | ||||||||||

| White | 3878 (82.0) | 0.003 | 454 (82.5) | 0.603 | 1368 (86.5) | 0.642 | 700 (87.7) | 0.306 | 1356 (75.2) | 0.199 |

| Black | 432 (9.1) | 22 (4.0) | 112 (7.1) | 28 (3.5) | 270 (15.0) | |||||

| Others | 383 (8.1) | 70 (12.7) | 87 (5.5) | 62 (7.8) | 164 (9.1) | |||||

| Unknown | 39 (0.8) | 4 (0.7) | 15 (0.9) | 8 (1.0) | 12 (0.7) | |||||

| Insurance recode | ||||||||||

| Insured | 4425 (93.5) | 0.849 | 518 (94.2) | 0.940 | 1469 (92.9) | 0.071 | 751 (94.1) | 0.293 | 1687 (93.6) | 0.258 |

| Uninsured | 152 (3.2) | 17 (3.1) | 51 (3.2) | 24 (3.0) | 60 (3.3) | |||||

| Unknown | 155 (3.3) | 15 (2.7) | 62 (3.9) | 23 (2.9) | 55 (3.1) | |||||

| Grade | ||||||||||

| Grade I | 538 (11.4) | <0.001 | 14 (2.5) | 0.562 | 458 (29.0) | <0.001 | 0 (0) | 0.752 | 66 (3.7) | <0.001 |

| Grade II | 670 (14.2) | 9 (1.6) | 563 (35.6) | 3 (0.4) | 95 (5.3) | |||||

| Grade III | 664 (14.0) | 2 (0.4) | 189 (11.9) | 42 (5.3) | 431 (23.9) | |||||

| Grade IV | 999 (21.1) | 3 (0.5) | 125 (7.9) | 117 (14.7) | 754 (41.8) | |||||

| Unknown | 1861 (39.3) | 522 (94.9) | 247 (15.6) | 636 (79.7) | 456 (25.3) | |||||

| Stage | ||||||||||

| Localized | 2008 (42.4) | <0.001 | 268 (48.7) | <0.001 | 875 (55.3) | <0.001 | 233 (29.2) | <0.001 | 632 (35.1) | <0.001 |

| Regional | 1579 (33.4) | 205 (37.3) | 461 (29.1) | 242 (30.3) | 671 (37.2) | |||||

| Distant | 900 (19.0) | 45 (8.2) | 164 (10.4) | 282 (35.3) | 409 (22.7) | |||||

| Unknown | 245 (5.2) | 32 (5.8) | 82 (5.2) | 41 (5.1) | 90 (5.0) | |||||

| Location | ||||||||||

| Head and neck | 608 (12.8) | <0.001 | 209 (38) | 0.091 | 159 (10.1) | 0.002 | 53 (6.6) | <0.001 | 187 (10.4) | <0.001 |

| Trunk | 1628 (34.4) | 333 (60.5) | 628 (39.7) | 380 (47.6) | 287 (15.9) | |||||

| Extremities | 2390 (50.5) | 3 (0.5) | 761 (48.1) | 333 (41.7) | 1293 (71.8) | |||||

| Unknown | 106 (2.2) | 5 (0.9) | 34 (2.1) | 32 (4.0) | 35 (1.9) | |||||

| T stage | ||||||||||

| T1 | 2084 (44.0) | <0.001 | 338 (61.5) | <0.001 | 821 (51.9) | <0.001 | 299 (37.5) | <0.001 | 626 (34.7) | <0.001 |

| T2 | 1692 (35.8) | 95 (17.3) | 484 (30.6) | 283 (35.5) | 830 (46.1) | |||||

| T3 | 127 (2.7) | 8 (1.5) | 26 (1.6) | 38 (4.8) | 55 (3.1) | |||||

| Unknown | 829 (17.5) | 109 (19.8) | 251 (15.9) | 178 (22.3) | 291 (16.1) | |||||

| N stage | ||||||||||

| N0 | 4258 (90.0) | <0.001 | 505 (91.8) | 0.009 | 1470 (92.9) | <0.001 | 660 (82.7) | <0.001 | 1623 (90.1) | <0.001 |

| N1 | 129 (2.7) | 6 (1.1) | 19 (1.2) | 58 (7.3) | 46 (2.6) | |||||

| Unknown | 345 (7.3) | 39 (7.1) | 93 (5.9) | 80 (10.0) | 133 (7.4) | |||||

| Bone metastases | ||||||||||

| No | 4349 (91.9) | <0.001 | 527 (95.8) | 0.002 | 1505 (95.1) | <0.001 | 654 (82.0) | <0.001 | 1663 (92.3) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 218 (4.6) | 4 (0.7) | 28 (1.8) | 112 (14.0) | 74 (4.1) | |||||

| Unknown | 165 (3.5) | 19 (3.5) | 49 (3.1) | 32 (4.0) | 65 (3.6) | |||||

| Brain metastases | ||||||||||

| No | 4550 (96.2) | <0.001 | 532 (96.7) | <0.001 | 1530 (96.7) | <0.001 | 756 (94.7) | 0.030 | 1732 (96.1) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 20 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 8 (1.0) | 8 (0.4) | |||||

| Unknown | 162 (3.4) | 17 (3.1) | 49 (3.1) | 34 (4.3) | 62 (3.4) | |||||

| Liver metastases | ||||||||||

| No | 4536 (95.9) | <0.001 | 530 (96.4) | <0.001 | 1521 (96.1) | <0.001 | 754 (94.5) | <0.001 | 1731 (96.1) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 35 (0.7) | 3 (0.5) | 12 (0.8) | 9 (1.1) | 11 (0.6) | |||||

| Unknown | 161 (3.4) | 17 (3.1) | 49 (3.1) | 35 (4.4) | 60 (3.3) | |||||

| Lung metastases | ||||||||||

| No | 4040 (85.4) | <0.001 | 527 (95.8) | 0.001 | 1443 (91.2) | <0.001 | 612 (76.7) | <0.001 | 1458 (80.9) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 531 (11.2) | 5 (0.9) | 88 (5.6) | 154 (19.3) | 284 (15.8) | |||||

| Unknown | 161 (3.4) | 18 (3.3) | 51 (3.2) | 32 (4.0) | 60 (3.3) | |||||

| Surgery | ||||||||||

| Surgery | 3674 (77.6) | <0.001 | 418 (76.0) | <0.001 | 1351 (85.4) | <0.001 | 433 (54.3) | <0.001 | 1472 (81.7) | <0.001 |

| No surgery | 1027 (21.7) | 128 (23.3) | 224 (14.2) | 359 (45.0) | 316 (17.5) | |||||

| Unknown | 31 (0.7) | 4 (0.7) | 7 (0.4) | 6 (0.8) | 14 (0.8) | |||||

SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program.

The mean age of all patients was 39.7 ± 24.1 years. Approximately 78.5% of patients with chordoma and 76% of patients with chondrosarcoma were diagnosed after 40 years of age, while 87.6% of patients with Ewing sarcoma and 71.7% of patients with osteosarcoma were diagnosed before 40 years of age. The distribution of patients with these four kinds of bone sarcoma presented in Fig. 2 is based on age at diagnosis. Tumor grade information was not recorded in many patients, especially those with chordoma (94.9%) and Ewing sarcoma (79.7%). For sarcomas with clear information regarding grade, chordoma and chondrosarcoma showed higher percentages of grade I and II, while a higher proportion of grade III and IV tumors were observed in Ewing sarcoma and osteosarcoma. The most common primary sites for chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma were the trunk and extremities (over 85%), while around 98.5% of chordoma was located in the region of the head, neck, and trunk. Among the 4487 (94.8%) cases with SEER historic stage records, 900 (19.0%) cases were diagnosed as “distant.” Higher percentages of the distant stage were noticed in Ewing sarcoma (35.3%) and osteosarcoma (22.7%). There were 531 (11.2%), 218 (4.6%), 35 (0.7%), and 20 (0.4%) patients who developed lung, bone, liver, and brain metastases, respectively. The incidence of metastasis was 17.8%, 28.2%, 6.9%, and 2.4% in osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and chordoma, respectively.

Fig. 2.

The distribution of patients with various kinds of bone sarcoma according to the age of diagnosis.

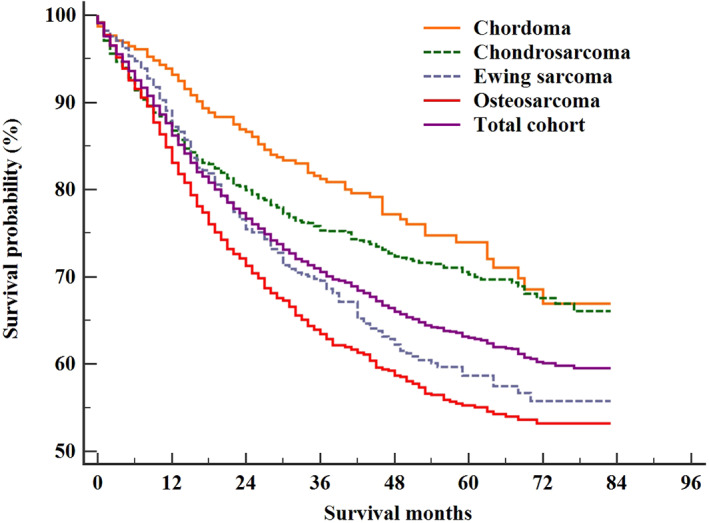

Survival and Prognostic Factors for the Total Cohort

By the time of the analysis, a total of 1271 patients had died. The mean survival of the entire cohort was 59.72 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 58.67–60.76). The OS rate at 1, 3, and 5 years for the total cohort was 86.2% (95% CI: 85.2%–87.2%), 70.5% (95% CI: 68.9%–72.1%), and 63.0% (95% CI: 61.2%–64.8%), respectively (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The overall survival of the entire cohort and the patients with chordoma, chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma and osteosarcoma.

In the univariate Cox regression analysis, age, gender, marital status, race, grade, SEER historic stage, tumor location, T stage, N stage, the presence of bone, brain, liver and lung metastases, and surgical treatment had a statistically significant influence on survival. Different bone sarcomas were proven to be with distinct prognosis (P < 0.001). As chordoma for reference, the HR and 95% CI for patients with chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma were 1.30 (95% CI: 1.04–1.62; P = 0.023), 1.69 (95% CI: 1.33–2.14; P < 0.001), and 2.00 (95% CI: 1.61–2.48; P < 0.001), respectively.

The multivariate analysis identified the following variables as independent prognostic factors for bone sarcomas: age older than 40 years, higher grade, regional and distant stage, tumor in the extremities, T2 stage, the presence of bone and lung metastases, and non‐surgical treatment. The type of sarcoma was not an independent prognostic factor in the multivariate analysis. The aforementioned prognostic factors are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of prognostic factors for patients in the SEER database with bone sarcomas from January 2010 to December 2016

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P‐value | HR | 95% CI | P‐value | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <18 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| 18–40 | 1.14 | 0.96–1.35 | 0.148 | 1.75 | 1.33–2.31 | <0.001 |

| >40 | 1.87 | 1.62–2.15 | <0.001 | 5.02 | 3.78–6.68 | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Male | 1.19 | 1.06–1.33 | 0.003 | 1.18 | 0.99–1.4 | 0.062 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Unmarried | 0.89 | 0.79–1.00 | 0.041 | 1.22 | 0.99–1.49 | 0.058 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Black | 1.30 | 1.09–1.55 | 0.004 | 1.14 | 0.88–1.48 | 0.316 |

| Others | 0.98 | 0.80–1.22 | 0.878 | 0.83 | 0.59–1.16 | 0.280 |

| Insurance recode | ||||||

| Insured | 1.00 | Reference | — | |||

| Uninsured | 1.05 | 0.76–1.44 | 0.769 | — | — | — |

| Sarcoma type | ||||||

| Chordoma | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Chondrosarcoma | 1.30 | 1.04–1.62 | 0.023 | 1.55 | 0.49–4.89 | 0.455 |

| Ewing sarcoma | 1.69 | 1.33–2.14 | <0.001 | 0.97 | 0.29–3.25 | 0.954 |

| Osteosarcoma | 2.00 | 1.61–2.48 | <0.001 | 1.89 | 0.59–6.06 | 0.282 |

| Grade | ||||||

| Grade I | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Grade II | 2.20 | 1.56–3.12 | <0.001 | 1.87 | 1.22–2.85 | 0.004 |

| Grade III | 5.78 | 4.19–8.00 | <0.001 | 5.40 | 3.58–8.13 | <0.001 |

| Grade IV | 5.83 | 4.26–7.98 | <0.001 | 6.02 | 3.96–9.17 | <0.001 |

| Stage | ||||||

| Localized | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Regional | 1.76 | 1.52–2.05 | <0.001 | 1.55 | 1.24–1.93 | <0.001 |

| Distant | 5.42 | 4.69–6.27 | <0.001 | 2.94 | 2.09–4.13 | <0.001 |

| Location | ||||||

| Head and neck | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Trunk | 1.66 | 1.37–2.02 | <0.001 | 0.94 | 0.67–1.31 | 0.700 |

| Extremities | 1.18 | 0.98–1.44 | 0.089 | 1.24 | 1.02–1.53 | 0.035 |

| T stage | ||||||

| T1 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| T2 | 2.08 | 1.82–2.38 | <0.001 | 1.28 | 1.06–1.55 | 0.012 |

| T3 | 3.48 | 2.62–4.62 | <0.001 | 1.30 | 0.84–2.01 | 0.244 |

| N stage | ||||||

| N0 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| N1 | 2.41 | 1.84–3.16 | <0.001 | 1.16 | 0.75–1.78 | 0.511 |

| Bone metastases | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 3.77 | 3.14–4.53 | <0.001 | 1.72 | 1.19–2.48 | 0.004 |

| Brain metastases | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 5.67 | 3.35–9.61 | <0.001 | 1.33 | 0.47–3.72 | 0.593 |

| Liver metastases | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 7.04 | 4.83–10.25 | <0.001 | 2.02 | 0.78–5.25 | 0.151 |

| Lung metastases | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 4.01 | 3.52–4.57 | <0.001 | 1.47 | 1.07–2.03 | 0.019 |

| Surgery | ||||||

| Surgery | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| No surgery | 3.62 | 3.23–4.06 | <0.001 | 2.37 | 1.87–3.00 | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program.

Survival and Prognostic Analysis in Patients with Chordoma, Chondrosarcoma, Ewing Sarcoma, and Osteosarcoma

The mean survival of patients with chordoma, chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma was 66.86 (95% CI: 64.06–69.66), 63.53 (95% CI: 61.81–65.25), 58.06 (95% CI: 55.49–60.62), and 54.91 (95% CI: 53.14–56.69) months, respectively (P < 0.001, Fig. 3).

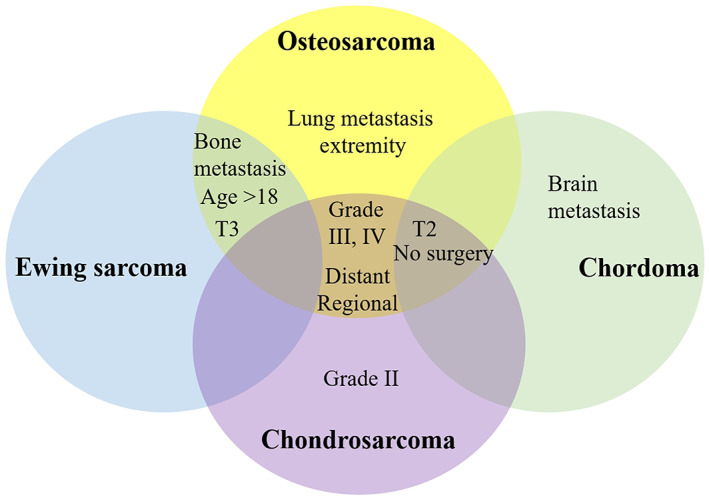

The subgroup analysis of survival for four types of bone sarcomas is summarized in Table 3. Significant difference was found in age, gender, marital status, White race, insured status, grade IV, SEER stage, tumor location in head and neck or trunk, T1 stage, N stage, distant metastases, and surgery. Different bone sarcomas showed homogenous and heterogenous prognostic factors (Fig. 4). Multivariate Cox regression analysis confirmed that T2 stage, brain metastasis, and non‐surgery were independent prognostic factors in patients with chordoma; higher grade, SEER historic stage, T2 stage, bone metastasis, and non‐surgery were independent prognostic factors in patients with chondrosarcoma; older age (>40 years old), T3 stage, and the presence of bone metastasis were associated with the survival of patients with Ewing sarcoma; older age, higher grade, SEER historic stage, tumor location, higher T stage, the presence of bone and lung metastases and non‐surgery were significant prognostic factors of patients with osteosarcoma. Detailed information from the univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses for prognostic factors in four bone sarcomas are summarized in Tables S1–S4.

TABLE 3.

Log‐rank test of the overall survival of patients in the SEER database with four types of malignant bone sarcomas diagnosed between January 2010 and December 2016

| Subject characteristics | Log‐rank test | |

|---|---|---|

| χ2 | P‐value | |

| Age (years) | ||

| <18 | 10.423 | 0.015 |

| 18–40 | 89.278 | <0.001 |

| >40 | 202.313 | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 36.825 | <0.001 |

| Female | 36.124 | <0.001 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 107.625 | <0.001 |

| Unmarried | 10.781 | 0.013 |

| Unknown | 16.093 | 0.001 |

| Race | ||

| White | 51.734 | <0.001 |

| Black | 7.137 | 0.068 |

| Others | 6.364 | 0.095 |

| Unknown | 2.998 | 0.392 |

| Insurance recode | ||

| Insured | 62.787 | <0.001 |

| Uninsured | 3.073 | 0.381 |

| Unknown | 10.172 | 0.017 |

| Grade | ||

| Grade I | 0.820 | 0.664 |

| Grade II | 2.787 | 0.426 |

| Grade III | 1.753 | 0.625 |

| Grade IV | 69.810 | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 40.452 | <0.001 |

| Stage | ||

| Localized | 11.351 | 0.010 |

| Regional | 12.405 | 0.006 |

| Distant | 53.370 | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 5.800 | 0.122 |

| Location | ||

| Head and neck | 38.553 | <0.001 |

| Trunk | 190.682 | <0.001 |

| Extremities | 4.495 | 0.213 |

| Unknown | 8.556 | 0.036 |

| T stage | ||

| T1 | 36.512 | <0.001 |

| T2 | 5.211 | 0.157 |

| T3 | 2.895 | 0.408 |

| Unknown | 31.982 | <0.001 |

| N stage | ||

| N0 | 55.241 | <0.001 |

| N1 | 14.394 | 0.002 |

| Unknown | 9.465 | 0.024 |

| Bone metastases | ||

| No | 54.132 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 26.367 | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 7.377 | 0.061 |

| Brain metastases | ||

| No | 65.411 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 11.910 | 0.008 |

| Unknown | 4.803 | 0.187 |

| Liver metastases | ||

| No | 66.709 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 6.975 | 0.073 |

| Unknown | 4.004 | 0.261 |

| Lung metastases | ||

| No | 35.504 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 62.338 | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 2.876 | 0.411 |

| Surgery | ||

| Surgery | 50.135 | <0.001 |

| No surgery | 88.929 | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.276 | 0.735 |

SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program.

Fig. 4.

Venn diagram for the homogenous and heterogenous prognostic factors for different bone sarcomas.

Discussion

In the present study, based on a large population, we performed a thorough investigation of the clinicopathological characteristics and survival rates of four common bone sarcomas. Homogenous and heterogeneous performances were found among the different bone sarcomas. In our study, the mean survival rates of patients with chordoma, chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma were 66.9, 63.5, 58.1, and 54.9 months, respectively. A similar histology‐specific survival trend was reported in a study on non‐metastatic primary osseous spinal neoplasms from 1973 to 2003 12 . For the entire cohort, age older than 40 years, higher tumor grade, regional and distant stage, tumor in the truck, T2 stage, bone and lung metastasis, and non‐surgery were confirmed to be the significant factors of survival. Sarcoma‐specific factors were also identified for each bone sarcoma.

Homogenous Factors for Different Bone Sarcomas and Clinical Applications

The homogenous prognostic factors for the four bone sarcomas included metastasis, higher T stage, and non‐surgery. The metastasis in patients with bone sarcomas was reported with an approximate incidence of 17.8% for chordoma 13 , 15% for chondrosarcoma 8 , 30% for Ewing sarcoma in patients younger than 40 years, and 15% in osteosarcoma 6 , 14 . In the present study, the incidence of metastasis was 2.4%, 8.3%, 35.5%, and 18.1% for patients with chordoma, chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma, respectively. The inconsistency between different studies may be caused by different regions and special samples of patients. Previous studies have shown that the presence of metastasis is associated with significantly decreased survival 15 , 16 . In the present study, metastasis was also confirmed as an independent factor of the reduced survival. Some studies have confirmed that the timing of occurrence of metastasis is an important factor of survival, and that the worst survival rate is found in patients with metastasis during chemotherapy 17 , 18 . Thus, timely and routine radiographic tests should be performed for patients with high risk to identify possible metastasis.

As to different bone sarcomas, in our study, metastasis to bone was found to be the homogenous predictive factor for chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma. Bone metastasis and its possible effect have been previously studied. Metastasis to bone was reported to lead to the worse prognosis in patients with chordoma 13 . Poor prognosis was reported in osteosarcoma patients with bone metastasis 19 . To our knowledge, this was the first time that the effect of bone metastasis on the survival of patients with different bone sarcomas has been thoroughly investigated in a large population. Furthermore, lung metastasis was a significant prognostic factor for osteosarcoma, while brain metastasis was a significant prognostic factor for chordoma. Lung metastasis and its negative influence on survival in osteosarcoma have been confirmed in many studies 15 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 . Brain metastasis is rare and requires more attention in patients with chordoma.

Timely diagnosis of bone sarcoma can limit the tumor in the lower T stage and confine the extent of invasion, which can improve the possibility of radical resection 12 . In the present study, non‐surgery on the primary lesion significantly reduced the survival rate in chordoma, chondrosarcoma, and osteosarcoma but not Ewing sarcoma. However, in another study including non‐metastatic primary osseous spinal neoplasms (chordoma, chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma), surgical resection significantly improved the OS rate 12 . The inconsistent influence of surgery on Ewing sarcoma might be caused by the high incidence of metastasis (28.2%) in the present study.

Heterogenous Factors for Different Bone Sarcomas and Clinical Applications

Older age was also found to be a significant prognostic factor in osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma. A previous study on primary osteosarcoma found more involvement in axial bone and poor response to chemotherapy in older patients 22 , which were considered the reason for worse survival rates in older patients. As to Ewing sarcoma, one study found more axial tumors and metastatic disease at diagnosis in patients older than 40 years 23 . The 5‐year survival rate of these patients was only 40.6%, compared with 54.3% for patients younger than 40 years 23 . As to chondrosarcoma and chordoma, no correlation was found with older age. A previous study found that age older than 50 years was a significant factor leading to the reduced survival rate in patients with chondrosarcoma and chordoma 11 . One study found more metastatic disease in young patients with chordoma 13 . In the present study, patients with chondrosarcoma and chordoma were commonly diagnosed at an older age. The relatively smaller proportion of metastasis in older patients with chondrosarcoma and chordoma might balance the effect of older age on survival.

Higher grade was found to be a independent factor for the survival of patients with osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma. Most osteosarcomas are high grade and need multi‐principle treatments 24 . Accordingly, high‐grade osteosarcoma has been investigated in many studies. In a study analyzing 247 pediatric chondrosarcoma patients, higher tumor grade was found to be independently related to reduced survival 25 . Similar results were shown in patients with conventional chondrosarcoma 26 and poorly differentiated chordoma 27 . As to chordoma and Ewing sarcoma in the present study, patients without complete records comprised 94.9% and 79.7% of patients, respectively, resulting in the uncertain conclusion about the effect of high grade on survival in these bone sarcomas.

Although radical surgery is the foundational treatment for bone sarcoma, a multidisciplinary approach is required before and after radical and non‐radical surgery to improve survival. Under the methotrexate, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MAP) regimen, modern chemotherapy has achieved a 3‐year event‐free survival rate of 76% in osteosarcoma patients with good histologic response 28 . Previous studies confirmed that poor histologic response to chemotherapy was associated with reduced survival 29 , 30 . Radiation therapy was also evaluated and no improved survival after the addition of radiation was found in patients with chordomas and chondrosarcomas in skull 11 . Another study of pediatric Ewing sarcoma did find significant difference in survival rates for radiation or chemotherapy treatment 7 . The absence in the SEER database of important information on radiotherapy and chemotherapy was one of the limitations of our study. The influence of these treatments on survival should be further evaluated in future research.

Limitations

Several limitations should be stated. In the present study, we conducted a thorough investigation of the survival and prognostic factors of four common bone sarcomas. Other less common types of bone sarcomas were not investigated in this study. The interpretation of results should be based on this background. Although we included a large sample of bone sarcomas with metastasis, some patients at distant stage had no clear records of the metastatic site, resulting in bias in the analysis about the effect of metastases. The small number of patients with brain and liver metastasis made the analysis on survival difficult. Various pathological types can be found in each bone sarcoma and we did not evaluate the effect on survival performance among different pathological types. Corresponding investigations should be conducted in future to draw clear conclusions.

Conclusion

The best survival was found in patients with chordoma, followed by chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma. Different bone sarcomas showed homogenous and heterogenous prognostic factors, which can be used to assist sarcoma‐specific management.

Supporting information

Table S1 Supporting information.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the SEER program for providing open access to the database. The present study was sponsored by the Natural Science Foundation of China (8191101553, 81702161, 81802508, and 81903398), the Natural Science Foundation of China Cultivation Project of Jining Medical University (JYP2019KJ08), the Scientific Research Staring Foundation for the Doctors of Jining Medical University (6001/6007890010), the Top Talent Training Program of the First Affiliated Hospital of PLA Army Medical University (SWH2018BJKJ‐12), and the Chongqing Natural Science Foundation Program (cstc2019jcyj‐msxmX0466).

Disclosure: The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Contributor Information

Ping Cui, Email: cuiping1989@yeah.net.

Chao Zhang, Email: drzhangchao@tmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1. Mohammed KA, Hinyard L, Schoen MW, et al Description of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with metastatic cancer: a national sample. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2018, 16: 136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mirabello L, Troisi RJ, Savage SA. Osteosarcoma incidence and survival rates from 1973 to 2004: data from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. Cancer, 2009, 115: 1531–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rozeman LB, Cleton‐Jansen AM, Hogendoorn PC. Pathology of primary malignant bone and cartilage tumours. Int Orthop, 2006, 30: 437–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Worch J, Ranft A, DuBois SG, Paulussen M, Juergens H, Dirksen U. Age dependency of primary tumor sites and metastases in patients with Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 2018, 65: e27251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bakker SH, Jacobs W, Pondaag W, et al Chordoma: a systematic review of the epidemiology and clinical prognostic factors predicting progression‐free and overall survival. Eur Spine J, 2018, 27: 3043–3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang W, Yang J, Wang Y, et al Survival and prognostic factors in Chinese patients with osteosarcoma: 13‐year experience in 365 patients treated at a single institution. Pathol Res Pract, 2017, 213: 119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Martin E, Radomski S, Harley EH. Pediatric Ewing sarcoma of the head and neck: a retrospective survival analysis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, 2019, 117: 138–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thorkildsen J, Taksdal I, Bjerkehagen B, et al Chondrosarcoma in Norway 1990‐2013; an epidemiological and prognostic observational study of a complete national cohort. Acta Oncol, 2019, 58: 273–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fukushima T, Ogura K, Akiyama T, Takeshita K, Kawai A. Descriptive epidemiology and outcomes of bone sarcomas in adolescent and young adult patients in Japan. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2018, 19: 297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hodel S, Seeli F, Fuchs B. Demographic analysis of patients with osteosarcoma, chonddrosarcoma, Ewing's sarcoma from one Sarcoma Center in Switzerland. Praxis (Bern 1994), 2015, 104: 673–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bohman LE, Koch M, Bailey RL, Alonso‐Basanta M, Lee JY. Skull base chordoma and chondrosarcoma: influence of clinical and demographic factors on prognosis: a SEER analysis. World Neurosurg, 2014, 82: 806–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mukherjee D, Chaichana KL, Parker SL, Gokaslan ZL, McGirt MJ. Association of surgical resection and survival in patients with malignant primary osseous spinal neoplasms from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) database. Eur Spine J, 2013, 22: 1375–1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Young VA, Curtis KM, Temple HT, Eismont FJ, DeLaney TF, Hornicek FJ. Characteristics and patterns of metastatic disease from chordoma. Sarcoma, 2015, 2015: 517657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Salah S, Ahmad R, Sultan I, Yaser S, Shehadeh A. Osteosarcoma with metastasis at initial diagnosis: current outcomes and prognostic factors in the context of a comprehensive cancer center. Mol Clin Oncol, 2014, 2: 811–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mukherjee D, Chaichana KL, Adogwa O, et al Association of extent of local tumor invasion and survival in patients with malignant primary osseous spinal neoplasms from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) database. World Neurosurg, 2011, 76: 580–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Raciborska A, Bilska K, Drabko K, et al Validation of a multi‐modal treatment protocol for Ewing sarcoma—a report from the polish pediatric oncology group. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 2014, 61: 2170–2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ahmed G, Zamzam M, Kamel A, et al Effect of timing of pulmonary metastasis occurrence on the outcome of metastasectomy in osteosarcoma patients. J Pediatr Surg, 2019, 54: 775–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tsuchiya H, Kanazawa Y, Abdel‐Wanis ME, et al Effect of timing of pulmonary metastases identification on prognosis of patients with osteosarcoma: the Japanese Musculoskeletal Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol, 2002, 20: 3470–3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bacci G, Longhi A, Bertoni F, et al Bone metastases in osteosarcoma patients treated with neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy: the Rizzoli experience in 52 patients. Acta Orthop, 2006, 77: 938–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Letourneau PA, Xiao L, Harting MT, et al Location of pulmonary metastasis in pediatric osteosarcoma is predictive of outcome. J Pediatr Surg, 2011, 46: 1333–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hung GY, Yen HJ, Yen CC, et al Improvement in high‐grade osteosarcoma survival: results from 202 patients treated at a single institution in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore), 2016, 95: e3420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tsuchie H, Emori M, Nagasawa H, et al Prognosis of primary osteosarcoma in elderly patients: a comparison between young and elderly patients. Med Princ Pract, 2019, 28: 425–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Karski EE, Matthay KK, Neuhaus JM, Goldsby RE, Dubois SG. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with Ewing sarcoma over 40 years of age at diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol, 2013, 37: 29–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Redondo A, Bague S, Bernabeu D, et al Malignant bone tumors (other than Ewing's): clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow‐up by Spanish Group for Research on Sarcomas (GEIS). Cancer Chemother Pharmacol, 2017, 80: 1113–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wu AM, Li G, Zheng JW, et al Chondrosarcoma in a paediatric population: a study of 247 cases. J Child Orthop, 2019, 13: 89–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Song K, Shi X, Liang X, et al Risk factors for metastasis at presentation with conventional chondrosarcoma: a population‐based study. Int Orthop, 2018, 42: 2941–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shih AR, Cote GM, Chebib I, et al Clinicopathologic characteristics of poorly differentiated chordoma. Mod Pathol, 2018, 31: 1237–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bielack SS, Smeland S, Whelan JS, et al Methotrexate, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MAP) plus maintenance pegylated interferon Alfa‐2b versus MAP alone in patients with resectable high‐grade osteosarcoma and good histologic response to preoperative MAP: first results of the EURAMOS‐1 good response randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol, 2015, 33: 2279–2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kim W, Han I, Lee JS, Cho HS, Park JW, Kim HS. Postmetastasis survival in high‐grade extremity osteosarcoma: a retrospective analysis of prognostic factors in 126 patients. J Surg Oncol, 2018, 117: 1223–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pan HY, Morani A, Wang WL, et al Prognostic factors and patterns of relapse in ewing sarcoma patients treated with chemotherapy and r0 resection. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2015, 92: 349–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Supporting information.