Abstract

Oct4 plays a crucial role in the regulation of self-renewal of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and reprogramming of somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem cells. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying posttranslational regulation and protein stability of Oct4 remain unclear. Using affinity purification and mass spectrometry analysis, we identified Kap1 as an Oct4-binding protein. Silencing of Kap1 reduced the protein levels of Oct4 in ESCs, whereas the overexpression of Kap1 stimulated the levels of Oct4. In addition, Kap1 overexpression stimulated the self-renewal of ESCs and attenuated the spontaneous differentiation of ESCs in response to LIF withdrawal. Kap1 overexpression increased the stability of Oct4 by inhibiting the Itch-mediated ubiquitination of Oct4. Silencing of Kap1 augmented Itch-mediated ubiquitination and inhibited the stability of Oct4. We identified the lysine 133 (K133) residue in Oct4 as a ubiquitination site responsible for the Kap1-Itch-dependent regulation of Oct4 stability. Preventing ubiquitination at the lysine residue by mutation to arginine augmented the reprogramming of mouse embryonic fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. These results suggest that Kap1 plays a crucial role in the regulation of the pluripotency of ESCs and somatic cell reprogramming by preventing Itch-mediated ubiquitination and the subsequent degradation of Oct4.

Subject terms: Ubiquitylation, Protein-protein interaction networks

Introduction

The self-renewal capacity and pluripotency of pluripotent stem cells are regulated by an intricate network of core stemness transcription factors, including Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog [1–3]. Recent studies have extensively focused on the transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of self-renewal and pluripotency by the stemness factors [4–6]. However, an increasing body of evidence suggests that posttranslational modifications also play an essential role in the regulation of their protein stability involved in stemness maintenance [7, 8]. Ubiquitination, one of the most critical posttranslational modifications, is regulated by a specific enzyme cascade in which ubiquitin binds to target substrates, and thereby contributes to the regulation of ESC pluripotency and cellular reprogramming by modulating the protein stability of stemness factors [9]. However, the molecular mechanisms implicated in the ubiquitination-dependent regulation of the protein stability of stemness factors are still elusive.

Of the stemness factors, Oct4 encoded by Pou5f1, also known as OCT3/4, is essential for mammalian embryonic development [10–12]. Oct4 plays a crucial role in the transcriptional network responsible for the self-renewal and pluripotency of ESCs and acts as a key reprogramming factor to generate induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [13, 14]. Oct4 belongs to the POU domain family containing a POU-specific domain (POUS) and a POU-homeodomain (POUH), which play an essential role in the regulation of Oct4 functions, such as interacting with DNA for biological activity and facilitating somatic reprogramming [15, 16]. In addition, it has been reported that the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of Oct4 play a vital role in the regulation of the protein stability and transcriptional activity of Oct4. However, the specific mechanisms involved in the regulation of the protein stability of Oct4 have been mostly unexplored.

KRAB-associated protein 1 (Kap1, also known as Trim28) has been mainly identified as a transcriptional corepressor that can interact with KRAB domains [17–19]. Kap1 plays a crucial role in epigenetic regulation through recruiting chromatin-modification and remodeling factors [20]. Kap1 plays a key role in preservation of transcriptional dynamics in ESCs by repressing retrotransposon-based enhancers [21]. Though Kap1 has been extensively studied as a transcription regulator, an increasing body of evidence suggests that Kap1 plays several transcription-independent functions, such as signaling scaffold protein in DNA damage responses, an enzyme with SUMO E3 ligase activity, and ubiquitin E3 ligase activity [22–24]. Moreover, Kap1 regulates the pluripotency of ESCs through Oct4-dependent transcription in a phosphorylation-dependent manner [25], and it is also involved in the regulation of somatic cell reprogramming [26]. However, it has not yet been studied whether Kap1 is involved in the regulation of the ubiquitination and protein stability of Oct4.

In this study, we identified Kap1 as a binding partner of Oct4 and characterized the role of the interaction between Kap1 and Oct4 in the regulation of pluripotency of ESCs and the reprogramming of somatic cells to iPSCs. We demonstrate for the first time that Kap1 regulates Oct4 stability by inhibiting Itch-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of Oct4. These results show that Kap1-mediated regulation of Oct4 stability may affect the pluripotency of stem cells and enhance the reprogramming efficiency of somatic cells.

Materials and methods

Materials

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), MEM nonessential amino acids, Glutamax-1, β-mercaptoethanol, Penicillin-Streptomycin, FBS, Trypsin, Lipofectamine-Plus, G418 (Geneticin, 10131035), and Blasticidin (R21001) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies and Enhanced Chemiluminescence Western Blotting detection reagents were purchased from Amersham Biosciences (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA). pNTAP vector (#240101) was purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). The following antibodies were used in this study: anti-Kap1 (ab22553), anti-Sox2 (ab59776), and anti-Klf4 (ab75486), which were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Anti-Nanog (#8822), anti-HA (#3724), anti-Myc-tag (#2278), anti-Ubiquitin (#3933), anti-Vimentin (#5741), anti-Cyclin D3 (#9932), and anti-GAPDH (#2118) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA). Anti-Itch (611199) and anti-N-cadherin (610920) were purchased from BD Bioscience (Heidelberg, Germany). Antibodies against Oct4 (sc-5279), c-Myc (sc-40), Cyclin A (sc-751), Cyclin D1 (sc-246), and SSEA-1 (sc-21702) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-Flag-tag (F9291) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF, ESG1107), doxycycline (Dox) (D9891), cycloheximide (CHX) (01810), MG132 (474790), protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340), alkaline phosphatase detection kit (86R), and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO).

ESC culture and differentiation

All mouse ESC lines (D3 and Ainv15 ESCs) were seeded on mitomycin-C-treated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) feeder and cultured in an ESC culture media consisting of DMEM supplemented with 1× nonessential amino acids, 1× Glutamax-1, 15% FBS, 1× penicillin-streptomycin, 0.1-mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1000-U/ml LIF. MEFs were isolated from 12.5-day-old embryos in pregnant C3H mice and maintained in MEF medium (DMEM with high glucose, 1× Glutamax-1, 10% FBS, and 1× penicillin-streptomycin), as described previously [2]. Naïve mouse ESCs were maintained in feeder-cell free culture conditions, including N2B27 media containing 2i inhibitors (1-μM PD0325901 and 3-μM CHIR99021) and 1000-U/ml LIF [27]. Cells were incubated in a humidified incubator at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Cells were tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Generation of the Kap1-inducible ES cell line

To establish the “Tet-on” Kap1-inducible ES cell line, the Kap1 loxP-targeting vector (ploxKap1) was generated by subcloning a Kap1-IRES-IL2Rα cassette into the plox plasmid [28], and then co-transfecting along with pSalk-Cre recombinase expression plasmid into Ainv15 ESCs, resulting in the site-specific integration of the Kap1-IRES-IL2Rα cassette downstream of a promoter integrated into the hprt locus that is responsive to the tetracycline derivative Dox. The electroporated ESCs were co-cultured with neomycin-resistant mouse embryonic fibroblasts (CF6Neo MEF Mitomycin-C-treated; GlobalStem, GSC-6005M) in an ESC culture medium supplemented with 350-µg/ml G418. Individual G418-resistant ESC colonies were picked, expanded, and examined by PCR analysis for confirmation of the successful integration of the ploxKap1 targeting plasmid. The ESC lines with Dox-inducible Kap1 expression are denoted as Kap1-ESCs. The primers used for PCR consist of sequences within the ploxKap1 targeting plasmid (pgk promoter region) and within the neo gene in the parental Ainv15 ESC line that generates a 450-bp product. To induce Kap1 expression in ESCs, 0.5-μg/ml Dox was added to the culture medium. Primers: LoxinF 5′-CTAGATCTCGAAGGATCTGGAG-3′, LoxinR 5′-ATACTTTCTCGGCAGGAGCA-3′. PCR conditions: 10 min at 95 °C; 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 40 s at 58 °C, 1 min at 72 °C, and 5 min at 72 °C.

Gene silencing using shRNA lentivirus

pLKO.1-puro lentiviral vectors expressing Kap1 shRNA (TRCN0000071363) and non-target control shRNA (SHC002) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Functional sequences in the shRNA vectors are as follows: Kap1, “CCGGCCGCATGTTCAAACAGTTCAACTCGAGTTGAACTGTTTGAACATGCGGTTTTTG.” For the generation of lentiviral particles, 293FT cells were co-transfected with the shRNA lentiviral plasmid (pLKO.1-puro), and ViraPower Lentiviral packaging mix (pLP1, pLP2, pLP-VSV-G; Invitrogen) using Lipofectamine-Plus and culture supernatants containing lentivirus were harvested at 48 h after transfection. For lentiviral transduction, NIH3T3 cells were treated with culture supernatants from 293FT cells in the presence of 10-μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich), and stable cell lines expressing shRNA were generated by selection with Puromycin (5 μg/ml). To ensure the shRNA-mediated silencing of Kap1 expression, protein levels of Kap1 and GAPDH were determined by western blot analysis.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain (RT-PCR) reaction and quantitative RT-PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted using the TRIzol (T9424, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) method. For RT-PCR analysis, 2-μg aliquots of each RNA sample were subjected to cDNA synthesis using 200 U of M-MLV reverse transcriptase and 0.5 μg of oligo (dT) 15 primer (C-1101, Promega, Madison, WI). The cDNA in 2 μL of the reaction mixture was amplified using 0.5 U of GoTaq DNA polymerase (M8298, Promega, Madison, WI). The thermal cycle was as follows: denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 52–58 °C for 30 s, depending on the primers used, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. Each PCR reaction was carried out for 30 cycles, and the PCR products were size-fractionated on a 1.2% agarose gel with ethidium bromide and photographed under UV trans-illumination. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using an ABI 7500 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) sequence detection system using SYBR Green PCR MasterMix (ABS-4309155, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Experiments were performed in duplicate, and the data were normalized to the expression of Gapdh mRNA. Data were analyzed using the Δ (ΔCT) method and normalized to Gapdh. The primer sequences for quantitative RT-PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Construction of Oct4 and Kap1 expression vectors

Oct4 deletion constructs containing residues ΔPOU, ΔTAD2, N-half, TAD1, POU, and ΔTAD1 were generated from p3×Flag-CMV-10-Oct4 using the QuickChange-XLsite-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Kap1 deletion constructs containing residues 20-419, 619-835, 423-584, and 239-835 were generated from pDEST-HA-Kap1 using the QuickChange-XLsite-directed mutagenesis kit. pcDNA3.0-Flag-Oct4 mutants were generated by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis on the pcDNA3.0-Flag-Oct4 wild type (WT).

Western blotting

For the preparation of cell extracts, cells were treated with appropriate conditions, washed with ice-cold PBS, then lysed in lysis buffer B (20-mM Tris-HCl, 1-mM EGTA, 1-mM EDTA, 10-mM NaCl, 0.5-mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1-mM Na3VO4, 30-mM sodium pyrophosphate, 25-mM β-glycerol phosphate, 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.4). Lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and stained with 0.1% Ponceau S solution (P3504, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). After blocking with 5% nonfat milk, the membranes were immunoblotted with various antibodies, and bound antibodies were visualized with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies using the Enhanced Chemiluminescence Western blotting kit (ECL, Amersham Biosciences).

Immunoprecipitation

For the immunoprecipitation of endogenous Oct4 and Kap1, cell lysates of D3 ESCs were prepared by lysis in lysis buffer A (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, 0.5 M EDTA, 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol), supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail and 0.5-mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and centrifuged at a speed of 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. An aliquot (1 mg of protein) of ESC lysates was incubated with protein G-Sepharose beads (P3296) conjugated with 2 μg of the appropriate antibodies, including anti-Oct4, anti-Kap1, or control antibodies, for 2 h at 4 °C on a rotating wheel. The beads were washed extensively with lysis buffer A. The bound proteins were eluted by boiling in 2× SDS sample buffer, and resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel for western blot analysis. For the immunoprecipitation of exogenously transfected Oct4 and Kap1, Flag-tagged Oct4 (pcDNA3.0-Flag-Oct4), HA-tagged Kap1 (pDEST-HA-Kap1), and their deletion mutants were transfected into 293FT cells with Lipofectamine-Plus reagent, and the cell lysates were prepared by lysis in lysis buffer A. An aliquot of cell lysates (0.5 mg) was incubated with anti-Flag or anti-HA antibodies for 2 h at 4 °C on a rotating wheel (all from Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), followed by incubation with protein G-Sepharose for 1 h. The beads were spun down and washed extensively with lysis buffer A. The bound proteins were eluted by boiling in 2× SDS sample buffer, and resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel for western blot analysis.

Purification of recombinant Oct4 and Kap1 proteins and in vitro protein–protein interactions

His-tagged Oct4 and GST fusion proteins of Kap1 were expressed in Escherichia coli and lysed in lysis buffer B (50-mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100-mM NaCl, 1-mM EDTA, 0.2% Triton X-100). Recombinant His-Oct4 and GST-fused Kap1 proteins were purified by affinity chromatography on Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) or glutathione-sepharose beads (GE Healthcare, Pittsburg, PA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified His-tagged Oct4 protein and GST-fused Kap1 were incubated with a pull-down buffer. After an additional 1-h incubation, bound protein complexes were washed four times with binding buffer. The resulting protein complexes were eluted by boiling the beads in a 2× SDS sample buffer, resolved on an SDS-PAGE, followed by western blotting with anti-Oct4 antibodies.

Measurement of protein stability and ubiquitination assay

Transfected cells with various combinations of DNA were treated with MG132 (20 μM, 4 h) or CHX (60 μg/ml) or left untreated, and then lysed with ubiquitination buffer (40-mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 1-mM EDTA, 120-mM NaCl, 10-mM sodium pyrophosphate, 10-mM glycerophosphate, 50-mM sodium fluoride, 1.5-mM sodium orthovanadate, 1% Triton X-100, 1-mM PMSF, protease inhibitor cocktail). Subsequently, Flag IP and western blot analyses were performed as indicated.

Production of retroviruses

Retroviral plasmids carrying the reprogramming factors (pMX-Oct4, pMX-Sox2, pMX-Klf4, and pMX-c-Myc) were individually co-transfected with packaging plasmids (gag-pol and VSV-G) into Plat-GP cells using the Lipofectamine-Plus reagent. Plat-GP cells (RV-103, Cell Biolabs, Inc., San Diego, CA) were maintained in DMEM with high glucose, 10% FBS, 10-μg/mL Blasticidin, and 1× Penicillin-Streptomycin. Virus-containing supernatants were collected 2 days after transfection, passed through a 0.45-μm filter, and stored at −80 °C.

iPSC generation

Oct4-green fluorescent protein (GFP) MEFs, which were isolated from OG2/ROSA26 (Oct4-GFP) transgenic mice, expressing Gfp under a transgenic Oct4 promoter, were used to generate iPSCs. 1 × 105 Oct4-GFP MEFs were seeded into individual wells of six-well plates 1 day before infection with retroviruses harboring Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, or c-Myc (1:1:1:1 ratio, 10-μg/ml polybrene). MEF media were renewed on the next day of viral infection. On day 2 after infection, Oct4-GFP MEFs were collected and re-seeded onto Mitomycin-C-treated MEFs. Cells were switched to ES medium from day 5 after infection with a change of media every other day. The morphology of the cells was monitored under the microscope every day. After counting colonies on the indicated days, cells were subjected to further analysis.

Alkaline phosphatase (AP) staining

AP staining was performed for 30 min at room temperature in the dark using the Vector Red AP Substrate Kit I according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The cells were incubated with a substrate solution at room temperature until the development of suitable staining and were photographed with a model DFC300FX mounted digital camera (Leica, Solms, Germany).

Flow cytometry analysis

ESCs were dissociated into single cells and then incubated with PE-conjugated anti-SSEA-1 (560142, BD Biosciences) antibody for 20 min, followed by flow cytometry analysis on a FACS CantoΙΙ (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Ten thousand events were acquired on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA), and data analysis was performed using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). For quantification of the reprogramming efficiency, the percentage of GFP-positive cell population of Oct4-GFP iPSCs was measured by FACS analysis.

Cell proliferation assay and bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay

For the measurement of cell proliferation, ESCs were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells in six-well plates. At different time points (Days 3 and 6), ESCs were harvested, and the number of cells was counted. The average value of the three experiments performed in triplicate was determined. For the measurement of BrdU incorporation, mouse ESCs proliferation was measured by BrdU Flow kit (559619, BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The cells were incubated in ESC culture media containing 20-μM BrdU for 15 min and then stained with FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody and fluorescent DNA dye, 7-Aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD). Flow cytometry analysis was performed using a FACS CantoΙΙ and CellQuest software.

Statistical analysis

No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment. Results of multiple observations are presented as mean ± S.D. n values represent the number of independent experiments performed. For each in vitro independent experiment, technical replicates were used to ensure adequate statistical power. Statistical differences between the experimental groups were assessed using an unpaired Student’s t-test. For the analysis of multivariate data, group differences were assessed using a one-way or two-way ANOVA, followed by Scheffé’s post hoc test.

Results

Identification of Kap1 as an Oct4-binding protein

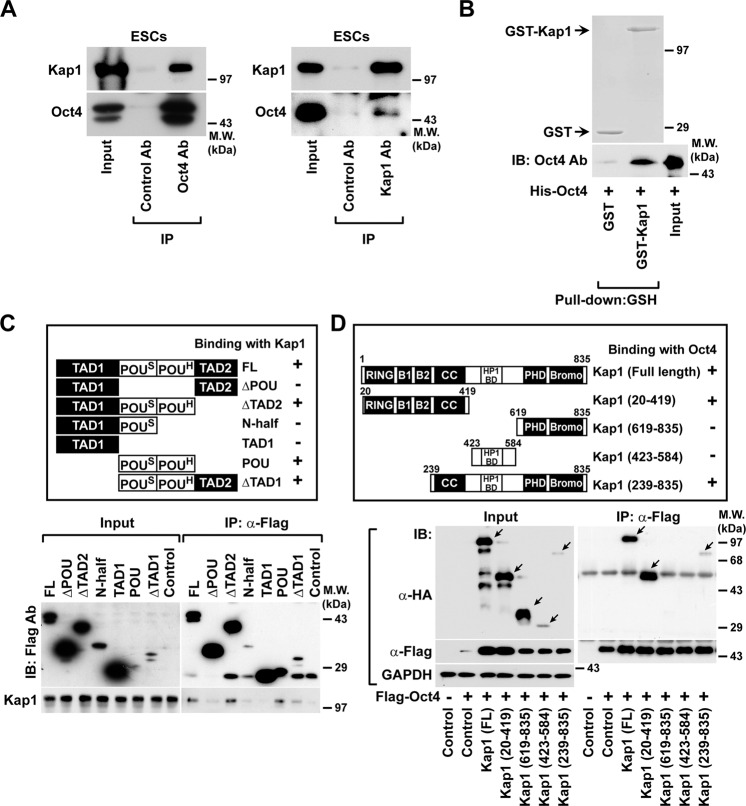

By using affinity purification and LC-MS/MS, we previously identified several Oct4-binding proteins, including not only Reptin but also Kap1 in HEK293 cells [29]. To clarify whether Kap1 interacts with Oct4 in ESCs, we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments in ESCs. Immunoprecipitation of endogenous Oct4 led to the co-precipitation of Kap1, and immunoprecipitation of endogenous Kap1 co-precipitated Oct4 in ESCs (Fig. 1a). In addition, the protein levels of Oct4 co-precipitated with GST-fused Kap1 were higher than that of Oct4 precipitated with GST (Fig. 1b), suggesting that Kap1 directly interacts with Oct4.

Fig. 1. Identification of Kap1 as an Oct4-binding protein.

a Co-immunoprecipitation of Kap1 and Oct4 in mESCs. D3 mESCs extracts were incubated with control IgG, anti-Oct4, or anti-Kap1 antibodies, and the protein levels of Oct4 and Kap1 in the immunocomplexes were probed by western blot analysis. b Direct interaction of Kap1 and Oct4 in vitro. GST and GST-Kap1 proteins were incubated with His-Oct4 protein, followed by a pull-down with GSH agarose. The protein levels of GST and GST-Kap1 were confirmed by SDS-PAGE and Ponceau S staining. The His-Oct4 protein levels in the immunocomplexes and input were determined by western blot analysis. c Mapping the Kap1-binding domain in Oct4 protein. Schematic diagrams of full-length (FL) and deletion forms of Oct4 protein (upper panels). The Flag-tagged Oct4 constructs were overexpressed in 293FT cells and immunoprecipitated by anti-Flag antibody. d Mapping of Oct4-binding domain in Kap1 protein. Schematic representation of the HA-Kap1 FL and deletion mutants (upper panel). Flag-Oct4 was co-transfected with HA-Kap1 FL or its deletion mutants into 293FT cells, followed by immunoprecipitation with the anti-Flag antibody. The protein levels of Flag-Oct4 and Kap1 in immunocomplexes and lysates (input) were analyzed by western blotting. Arrows indicate the Kap1 FL and deletion mutants.

To identify the Kap1-binding regions within the Oct4, 293FT cells were transfected with Flag-tagged full-length or deletion mutants of Oct4. Kap1 co-precipitated with full-length, ΔTAD2, POU, and ΔTAD1 of Oct4 deletion mutants, which contain both POUS and POUH domains (Fig. 1c), whereas ΔPOU, N-half, and TAD1 constructs, which lack both POUS and POUH domains, did not interact with Kap1. These results suggest that both POUS and POUH domains are essential for the interaction of Kap1 and Oct4.

Kap1 contains RING finger, B-box 1 and 2, and a coiled-coil (CC) region at the N-terminus and HP1 binding domain (HP1BD), a plant homeodomain finger, and a Bromodomain at the C-terminus. To identify the region of Kap1 that is involved in the interaction with Oct4, we constructed a series of Kap1 deletion mutants (Fig. 1d, upper panel). The N-terminal domain (aa 20-419) and C-terminal domain (aa 239-835) of Kap1 co-precipitated with Flag-tagged Oct4 (Fig. 1d); however, the middle region containing the HP1BD domain (aa 423-584) and C-terminal domain (aa 619-835) was not precipitated with Oct4. These results suggest that the CC domain of Kap1 is responsible for the interaction with Oct4.

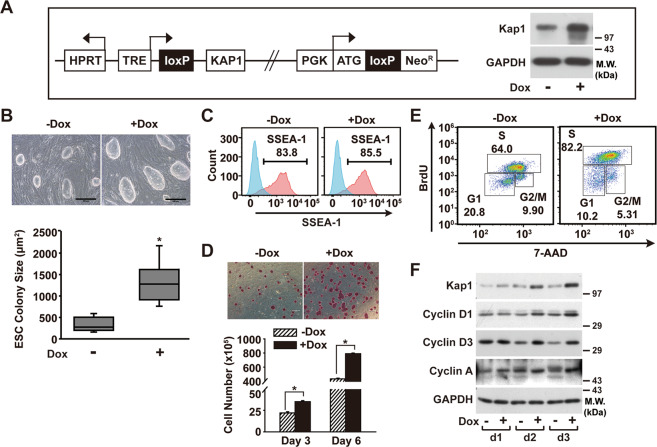

Kap1 regulates the proliferation of mouse ESCs

To investigate the role of Kap1 in ESCs, Dox-inducible Kap1-overexpressing ESCs (Kap1-ESCs) was generated by utilizing the Cre/loxP system [28]. Treatment of the Kap1-ESCs with Dox led to an increase in Kap1 protein levels compared to those in the untreated control (Fig. 2a). The Dox-treated Kap1-ESCs exhibited a larger colony size than the control ESCs (Fig. 2b). The flow cytometry analysis showed no significant difference in the percentage of ESC marker, SSEA-1, upon the Dox-inducible expression of Kap1 (Fig. 2c), suggesting that Kap1 overexpression did not affect the ESC phenotype. Dox-treated Kap1-ESCs exhibited larger AP-positive colonies than the control Kap1-ESCs, and the number of ESCs was increased by Dox treatment (Fig. 2d), suggesting Kap1-stimulated proliferation of ESCs. To confirm the stimulatory effect of Kap1 overexpression on ES cell proliferation, a BrdU incorporation assay was performed in the absence or presence of Dox. Upon the induction of Kap1 expression, the percentage of the S-phase cell population increased from 64% of control ESCs to 82.2% of Kap1-overexpressed ESCs, whereas the G1 and G2/M phase populations decreased in Kap1-overexpressed ESCs compared to those in control ESCs (G1: from 20.8 to 10.2%, G2/M: from 9.9 to 5.31%) (Fig. 2e). To ascertain the role of Kap1 in the regulation of cell cycle, we measured the expression of cyclins implicated in the G1/S-phase transition in response to Kap1 overexpression. G1 cyclins including D-type cyclins have been reported to regulate proliferation, pluripotency, and differentiation of ESCs [30], while murine ESCs typically express low levels of D-type cyclins and triple knockout of cyclins D1, D2, and D3 has no effect on the ESC pluripotency [31]. Interestingly, the induction of Kap1 expression led to increases of cyclin D1 and D3, which are key regulators for G1/S-phase transition [32], followed by an increase in cyclin A promoting S-phase entry [33] (Fig. 2f). Taken together, these results suggest that the overexpression of Kap1 promotes cell proliferation and leads to an increase in the proliferation of ESCs.

Fig. 2. Effects of the overexpression of Kap1 in the proliferation and cell cycle of ESCs.

a A schematic illustration of doxycycline (Dox)-inducible constructs used to express Kap1. The Dox-induced overexpression of Kap1 in Kap1-ESCs was confirmed by western blot analysis (right panel). b Colony morphologies of Kap1-ESCs, which were cultured in the absence or presence of Dox (0.5 µg/ml) treatment for 5 days, were photographed (upper images), and the colony size was quantified from the images (lower panel). Scale bar = 300 μm. Data represent mean ± S.D. (n = 4). * indicates p < 0.05 by Student’s t-test. c Effects of Kap1 induction on SSEA-1+ populations in mESCs. The percentages of SSEA-1+ populations in Kap1-ESCs were measured using flow cytometry analysis. ESCs were stained with antibodies against SSEA-1 (pink) and isotype control (blue). d The Dox-induced proliferation of Kap1-ESCs. 1 × 105 Kap1-ESCs were seeded and cultured with or without Dox treatment. Kap1-ESCs were stained with AP on 11 days (upper panel), and the number of cells was counted on the indicated days (lower panel). Scale bar = 500 μm. Data represent mean ± S.D. (n = 6). * indicates p < 0.05 by Student’s t-test. e The effects of Dox treatment on the cell cycle of Kap1-ESCs. Kap1-ESCs were cultured for 3 days in the absence or presence of Dox treatment, pulsed with BrdU for 15 min, then stained with anti-BrdU antibody and fluorescent DNA dye, 7-AAD (7-Aminoactinomycin D), followed by flow cytometry analysis for cell cycle analysis. f The protein levels of Kap1, cyclin proteins, and GAPDH were determined by western blot analysis at the indicated time points.

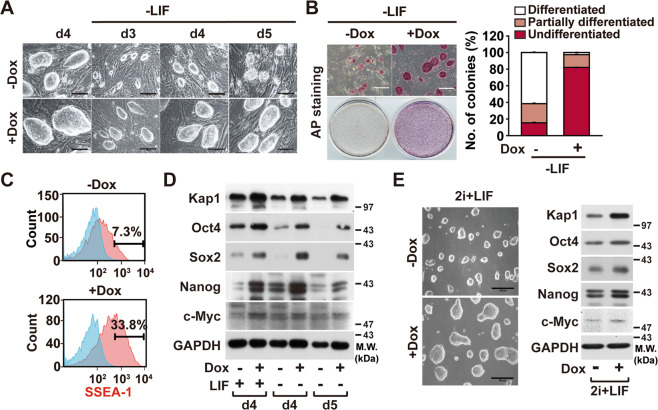

Kap1 overexpression attenuates the differentiation of ESCs

In vitro, mouse ESCs require LIF to maintain their pluripotent state, and, in the absence of LIF, they spontaneously differentiate [34]. To explore the effect of Kap1 overexpression in the differentiation induced by LIF deprivation, Kap1-ESCs were treated with or without Dox under the LIF-depleted culture conditions. Upon LIF withdrawal in the absence of Dox, Kap1-ESCs exhibited spontaneous differentiation and formed smaller colonies, whereas Dox-treated Kap1-ESCs maintained the typical morphology of ESC colonies (Fig. 3a). The ESC colonies were scored as AP-positive undifferentiated, AP-negative differentiated, and partially differentiated populations based on AP staining. Kap1-ESCs rapidly progressed to partial or total differentiation upon LIF withdrawal for 5 days, while Dox-treated Kap1-ESCs exhibited more AP-positive undifferentiated colonies after LIF withdrawal than control ESCs (Fig. 3b). Consistently, in the absence of Dox treatment, the percentage of SSEA-1+ cells decreased to 7.3% after LIF withdrawal, whereas Dox-treated Kap1-ESCs exhibited higher percentage of SSEA-1+ cells of 33.8% than Dox-untreated cells (Fig. 3c). These results suggest that Kap1 overexpression prevents the spontaneous ESC differentiation induced by LIF withdrawal. The Dox-induced expression of Kap1 increased protein levels of Oct4 in the presence of LIF, and the Dox-induced Kap1 overexpression sustained the protein levels of Oct4 despite LIF withdrawal (Fig. 3d). The protein levels of not only Oct4 but also the other core stemness factors, such as Sox2, NONOG, and c-Myc, were maintained in a LIF-deprived culture condition. Mouse ESCs were derived and established into a naïve pluripotent state using two small-molecule inhibitors (2i, CHIR99021, and PD0325901) [27, 35]. The combination of 2i and LIF (2i/LIF) conditions can replace serum/LIF conditions and maintain the pluripotency in the naïve state. Dox treatment of the Kap1-ESCs in the 2i/LIF culture condition also increased the colony size of the Kap1-ESCs and significantly augmented the protein levels of not only Oct4 but also Sox2 and Nanog. Protein level of endogenous c-Myc was also slightly but significantly increased by Kap1 induction (Fig. 3e). Taken together, these results suggest a potential role of Kap1 in the regulation of stemness in the naïve state of ESCs.

Fig. 3. Effects of Kap1 overexpression in the differentiation of ESCs.

a Effects of Kap1 overexpression on the LIF withdrawal-induced differentiation of ESCs. Kap1-ESCs were cultured in the absence or presence of LIF and/or Dox and photographed at the indicated time points. b The cells were subjected to AP staining on day 5 (left panel). Scale bar = 400 μm. The AP-positive undifferentiated, AP-negative differentiated, and partially differentiated colonies were quantified, and the relative percentages of the colonies are shown (right panel). Data represent mean ± S.D. (n = 4). * indicates p < 0.05 by Student’s t-test. c Kap1-ESCs under the LIF-depleted culture conditions were stained with SSEA-1 antibody (pink) or isotype control (blue). The percentages of SSEA-1+ populations in Kap1-ESCs were measured using flow cytometry analysis. d The effects of Kap1 overexpression on the LIF withdrawal-induced downregulation of stemness factors in ESCs. e The effects of Kap1 overexpression on the stemness of naïve ESCs. Kap1-ESCs were cultured in serum-free 2i+LIF medium in the absence or presence of Dox treatment. The cells were photographed, and the protein levels were determined by western blot analysis. Scale bar = 300 μm.

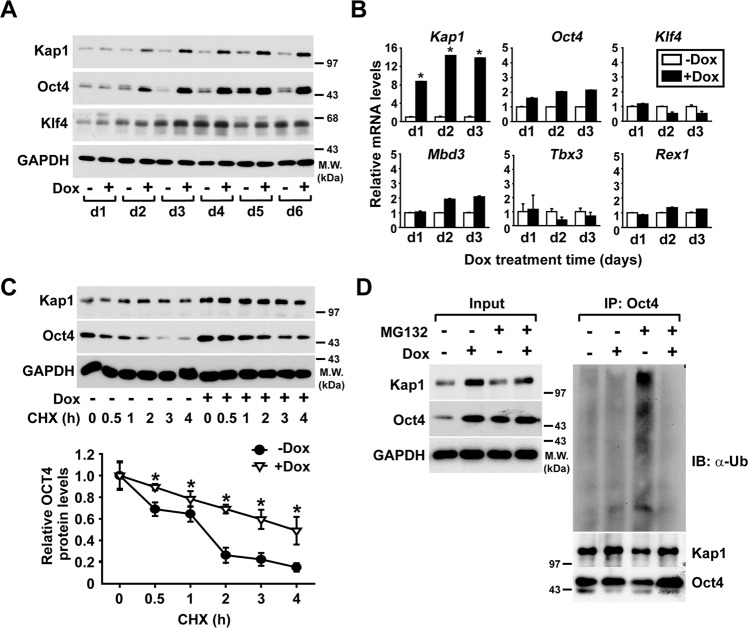

Overexpression of Kap1 stabilizes Oct4 protein in ESCs

To explore whether the Kap1-induced increase in Oct4 levels is due to the increased transcription of Oct4, the effects of Kap1 induction on the protein and mRNA levels of Oct4 in the Kap1-ESCs were measured. In Kap1-ESCs, the increase in Oct4 protein levels could be observed 2 days after Dox treatment, and the levels increased in a time-dependent manner until day 6; however, Klf4 protein levels were not affected by Dox treatment (Fig. 4a), suggesting a specific increase in Oct4 protein levels by Kap1 induction. Next, the expression of several pluripotency-related genes at the mRNA level was identified. Among pluripotency-related genes, the mRNA levels of Oct4 and Mbd3 slightly augmented, showing a marginal increase compared to the increase in Kap1 mRNA levels. Moreover, the mRNA levels of other pluripotency-related genes (Klf4, Tbx3, and Rex1) were not significantly altered by Kap1 overexpression (Fig. 4b). These results suggest that the Kap1-induced increase in Oct4 protein levels may be controlled by posttranslational regulation, such as protein stability.

Fig. 4. Effects of Kap1 overexpression on ubiquitination and protein stability of Oct4 in ESCs.

a The time-dependent effects of Kap1 overexpression on the protein levels of Oct4 in Kap1-ESCs. Kap1-ESCs were treated with or without Dox for the indicated time periods, and the protein levels were determined by western blotting. b The time-dependent effects of Kap1 overexpression on the mRNA levels of Oct4 and other pluripotency markers in Kap1-ESCs. The mRNA levels were measured and normalized to those of GAPDH. c The effects of Kap1 overexpression on protein stability of Oct4 in ESCs. Kap1-ESCs were treated with cycloheximide (CHX) in the absence or presence of Dox for the indicated times, and the protein levels of Kap1 and Oct4 were determined by western blotting (upper panel). The band intensities of Oct4 were quantified and normalized to those of GAPDH (lower panel). d The effects of Kap1 overexpression on the ubiquitination of Oct4 in ESCs. Kap1-ESCs were treated with 20-µM MG132 for 4 h in the absence or presence of Dox, and Oct4 was precipitated with the anti-Oct4 antibody. The protein levels and ubiquitination levels of Oct4 and the protein levels of Kap1 in the immunocomplexes were determined by western blotting. The protein levels of Kap1, Oct4, and GAPDH in cell lysates (input) were also analyzed by western blotting.

To explore the role of Kap1 in the regulation of Oct4 protein stability in ESCs, we measured the half-life of endogenous Oct4 protein after treatment with CHX, a protein synthesis inhibitor. In the absence of Dox treatment, the half-life of endogenous Oct4 protein in Kap1-ESCs was estimated to ~1 h, whereas the Dox-induced overexpression of Kap1 extended the half-life of endogenous Oct4 protein to about 4 h (Fig. 4c). Moreover, the Kap1-ESCs were treated with or without MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, to detect endogenous Oct4 ubiquitination. Interestingly, MG132 treatment led to an increase in Oct4 protein levels, and the ubiquitination of Oct4 was markedly inhibited by the Dox-induced expression of Kap1 (Fig. 4d), suggesting that Kap1 enhances Oct4 protein stability by blocking ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis in ESCs.

Kap1 inhibits the Itch-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of Oct4

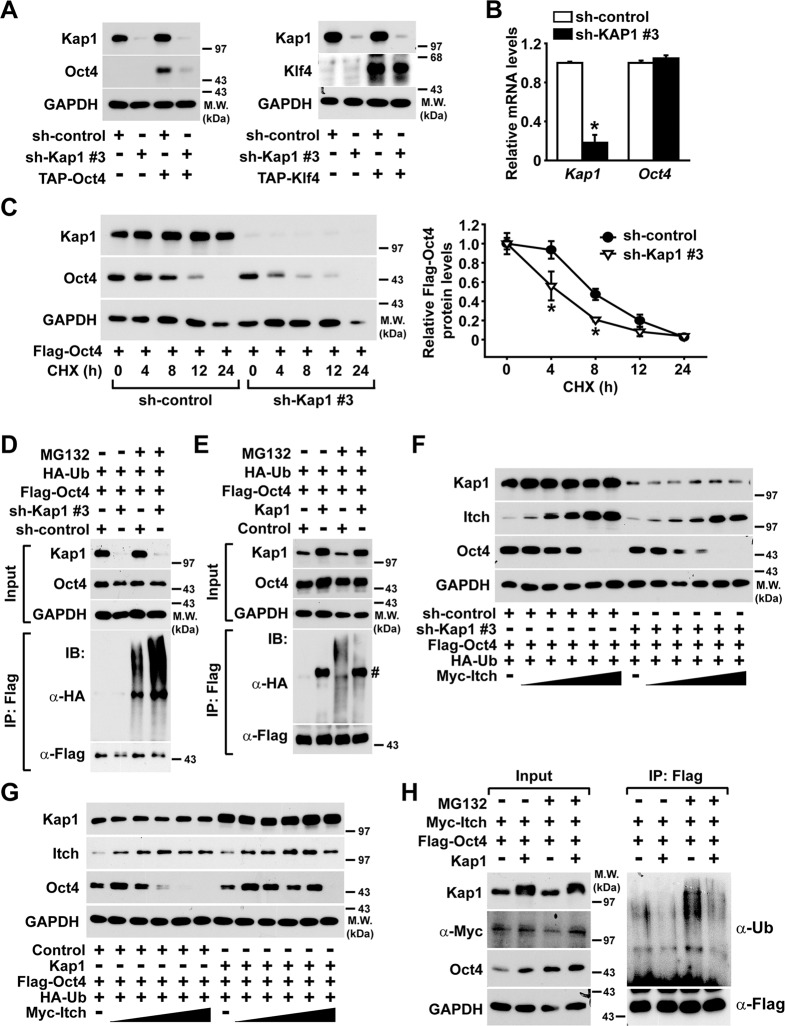

To explore the molecular mechanism involved in the regulation of protein stability of Oct4, in this study, Kap1-silenced NIH3T3 cells were established using Kap1 shRNA. We tested five different shRNA clones for Kap1 silencing in NIH3T3 cells and MEFs, and found that Kap1 shRNA clones 2 and 3 significantly suppressed the expression of endogenous or exogenously transfected Kap1 gene. The silencing effect of the shRNA clone 3 was more potent than that of the clone 2, therefore, we next used the clone 3 in the rest part of the present study (Fig. S1). Kap1 silencing using lentiviral transduction of the Kap1 shRNA clone 3 resulted in a reduction of Oct4 protein but not Klf4 protein levels in NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 5a). Not only Kap1 shRNA clone 3 but also clone 2 reduced the Oct4 protein level (Fig. S2). In contrast, Kap1 knockdown did not affect Oct4 at the mRNA level (Fig. 5b). Consistent with our data, the half-life of Oct4 protein in Kap1-knockdown cells decreased from ~8 to 4 h (Fig. 5c), and Kap1 knockdown using the Kap1 shRNA clone 2 also accelerated degradation of Oct4 protein (Fig. S3). MG132 treatment led to ubiquitination of Oct4, and in Kap1-knockdown cells, increased Oct4 ubiquitination was observed (Fig. 5d). Conversely, Kap1 overexpression in NIH3T3 cells resulted in decreased levels of Oct4 ubiquitination (Fig. 5e). These data demonstrate that Kap1 plays an essential role in the regulation of Oct4 protein stability through modulating the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.

Fig. 5. The role of Kap1 on the protein stability and Itch-mediated ubiquitination of Oct4.

a The effects of Kap1 knockdown on the protein levels of transiently transfected Oct4 and Klf4 in NIH3T3 cells. NIH3T3 cells were infected with lentiviruses encoding either Kap1-specific shRNA (sh-Kap1) or control shRNA (sh-control), and expression vectors bearing TAP-Oct4 or TAP-Klf4 were transfected into the NIH3T3 cells, and followed by western blotting. b The mRNA levels of Kap1 and Oct4 were measured and normalized to those of GAPDH in the Kap1-silenced or control NIH3T3 cells. c The effects of Kap1 knockdown on the protein stability of Oct4 in NIH3T3 cells. The Kap1-silenced or control NIH3T3 cells were transiently transfected with a Flag-Oct4-expressing vector. The cells were treated with CHX for the indicated times (left panel). The protein levels of Oct4 were quantified and normalized with those of GAPDH (right panel). Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 4). d, e The effects of Kap1 knockdown or overexpression on the ubiquitination of Oct4 in NIH3T3 cells. The expression vectors bearing Flag-Oct4 and HA-Ubiquitin (Ub) were co-transfected into NIH3T3 cells in which Kap1 was silenced (d) or overexpressed (e), and the cells were treated with MG132 before immunoprecipitation with the anti-Flag antibody. f, g The effects of Kap1 knockdown or the overexpression on the Itch-mediated degradation of Oct4 in NIH3T3 cells. Flag-Oct4-expressing vector and the increasing dose of Itch-expressing vector were co-transfected into NIH3T3 cells in which Kap1 was silenced or overexpressed. h The Kap1-dependent inhibition of Itch-mediated ubiquitination of Oct4. Expression vectors bearing Flag-Oct4 or Myc-Itch were co-transfected into the control or Kap1-overexpressing NIH3T3 cells, followed by treatment with MG132 and immunoprecipitation with anti-Flag antibody. The protein levels of Kap1, Oct4, and Itch in the immunocomplexes were determined by western blotting.

To understand how Kap1 stabilizes Oct4, the effects of Kap1 knockdown or overexpression on the E3 ubiquitin ligase-mediated Oct4 ubiquitination and degradation were investigated. Notably, Itch has been reported to regulate the stability of Oct4 in ESC self-renewal and somatic cell reprogramming [36]. Overexpression of Itch attenuated the levels of Oct4 in a dose-dependent manner, and Kap1 silencing promoted Oct4 degradation (Fig. 5f). Moreover, Kap1 overexpression attenuated the Itch-dependent degradation of Oct4 protein (Fig. 5g). Consistently, Kap1 overexpression led to a decrease in the Itch-dependent Oct4 ubiquitination (Fig. 5h). Therefore, these results suggest that Kap1 plays a pivotal role in the regulation of protein stability of Oct4 through interfering with Itch-mediated Oct4 ubiquitination.

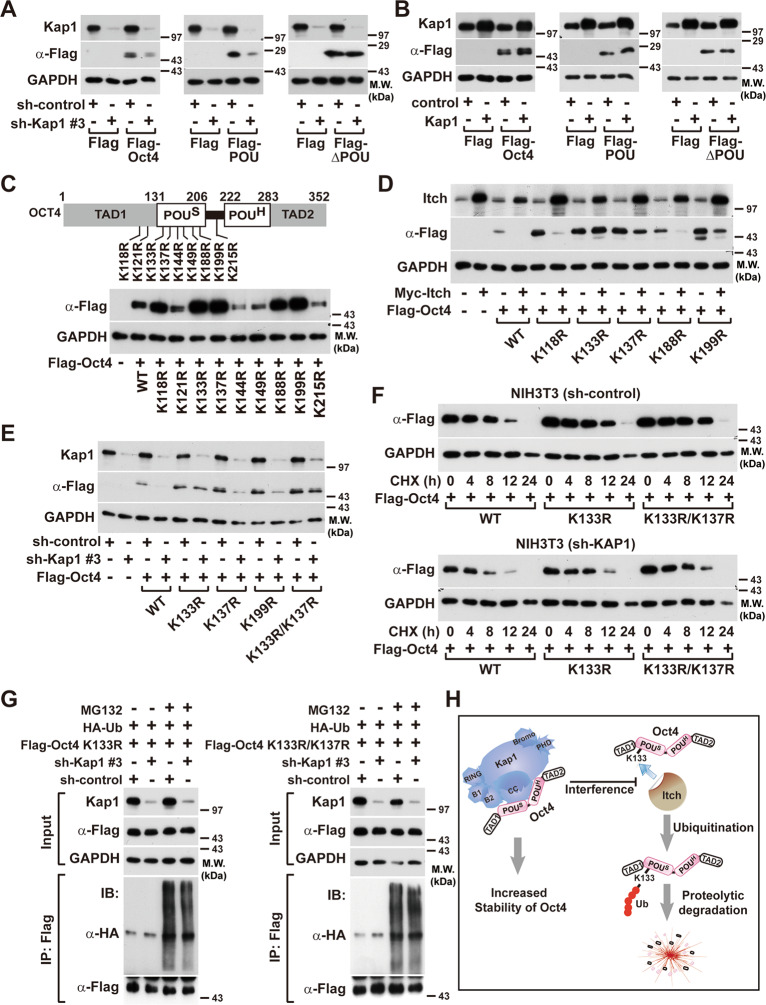

Kap1-mediated Oct4 protein is stabilized at K133 and K137 on the POU domain

To explore whether POU domains are responsible for the Kap1-mediated stabilization of Oct4, the effects of Kap1 silencing on the expression levels of full-length Oct4, POU domains (POU), and POU domain-deleted mutant (∆POU) were compared. The protein levels of the full-length and POU domain of Oct4 were downregulated in Kap1-silenced NIH3T3 cells and increased in Kap1-overexpressed cells (Fig. 6a, b).

Fig. 6. Identification of Kap1-regulated ubiquitination sites of Oct4.

a, b Involvement of the POU domains of Oct4 in the Kap1-regulated protein stability of Oct4. The expression vectors bearing Flag-tagged full-length, POU, or ΔPOU domains of Oct4 were transfected into NIH3T3 cells in which Kap1 was silenced (a) or overexpressed (b). The protein levels of Kap1 and Flag-tagged Oct4 or its deletion mutants were analyzed by western blotting. c Schematic presentation of Oct4 domains and point mutants of its potential ubiquitination sites from Lys residue to Arg residue (upper panel). NIH3T3 cells were transfected with Flag-tagged Oct4 wild type (WT) or its point mutants, and expression levels of Oct4 WT and mutants were determined by western blotting (lower panel). d Identification of lysine residues implicated in the Itch-dependent degradation of Oct4 protein. Myc-tagged Itch-expressing vector was co-transfected with Flag-Oct4 WT or its point mutants into NIH3T3 cells, and the protein levels of Itch, Oct4, and GAPDH were determined by western blotting. e Identification of lysine residues implicated in the Kap1-induced increase in Oct4 protein stability. Flag-Oct4 WT or its mutants were transfected into the Kap1-silenced or control NIH3T3 cells, and the protein levels of Kap1, Oct4, and GAPDH were determined by western blotting. f Effects of Kap1 knockdown on the protein stability of Oct4 WT and its ubiquitination site mutants. Kap1-silenced or control NIH3T3 cells were transfected with Flag-Oct4 WT, K133R, or K133R/K137R, followed by treatment with CHX for the indicated time periods and western blot analysis. g Flag-Oct4-K133R (left panel) or K133R/K137R (right panel) mutants were co-transfected with HA-Ub into the Kap1-silenced or the control NIH3T3 cells. After MG132 treatment for 4 h, the Oct4 proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag antibody, and the immunocomplexes were subjected to western blotting. h A schematic model for the Kap1-dependent regulation of Oct4 protein stability by inhibiting Itch-mediated ubiquitination.

To elucidate whether the ubiquitination of POU domains is involved in the Kap1-mediated stabilization of Oct4 protein, potential ubiquitination sites of Oct4 were predicted. Together with the previously reported lysine sites for ubiquitination [37], nine site-specific mutants of Oct4 (Fig. 6c, upper panel), in which Lysine (K) residue of Oct4 was replaced with Arginine (R), were generated. Out of the nine mutants of Oct4, five (K118R, K133R, K137R, K188R, and K199R) of them increased Oct4 protein levels compared to the Oct4 WT (Fig. 6c). To assess whether the protein stability of the Oct4 mutants can be affected by Itch-mediated ubiquitination, the effects of Itch overexpression on the protein levels of Oct4 mutants were examined. Itch overexpression decreased the protein levels of Oct4 WT, whereas the protein levels of the Oct4-K133R mutant were not affected by Itch overexpression and the protein levels of Oct4-K137R and Oct4-K199R were partially attenuated by Itch overexpression (Fig. 6d), suggesting that K133, K137, and K199 may be associated with the Itch-mediated degradation of Oct4. To determine whether the ubiquitination sites of Oct4 are responsible for the Kap1-dependent degradation of Oct4, the effects of Kap1 silencing on the protein levels of the Oct4 mutants were assessed. The protein levels of the WT and mutants (K137R and K199R) of Oct4 were drastically decreased upon Kap1 silencing; however, the protein levels of Oct4-K133R and K133R/K137R were not affected by Kap1 silencing (Fig. 6e). Consistently, the protein stability of the K133R and K133R/K137R mutants of Oct4 increased compared with that of Oct4 WT; however, knockdown of Kap1 expression abrogated the increased stability of the Oct4 mutants (Fig. 6f). Moreover, knockdown of Kap1 did not affect the ubiquitination of the K133R and K133R/K137R mutants of Oct4 (Fig. 6g). These results suggest that Kap1 inhibits Itch-mediated ubiquitination of the K133 residue of Oct4 and prevents proteolytic degradation of Oct4 (Fig. 6h).

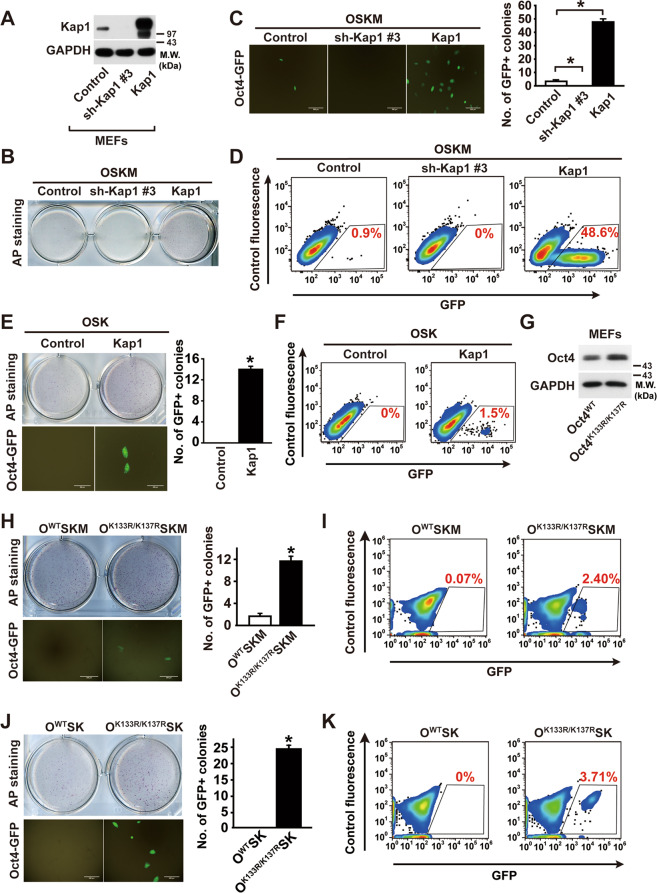

The ubiquitination site mutants of Oct4 exhibits increased reprogramming efficiency

The overexpression of Yamanaka transcription factors “OSKM” (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc) can reprogram MEFs into iPSCs [2]. To explore the role of Kap1 in reprogramming process, we measured the effects of Kap1 silencing on the reprogramming efficiency by using MEF expressing GFP under the Oct4 promoter (Oct4-GFP). Silencing and overexpression of Kap1 in MEFs were confirmed by western blotting (Fig. 7a). Unlike the control cells, Kap1 knockdown in MEFs by using Kap1 shRNA (clones 2 or 3) markedly abrogated iPSC formation induced by OSKM overexpression (Figs. 7b and S4); however, overexpression of Kap1 together with OSKM significantly augmented the formation of AP- and GFP-positive colonies (Fig. 7b–d). Since c-Myc has been known to act as an oncogene, whether Kap1 can replace c-Myc in the reprogramming of somatic cells was examined. Overexpression of OSK barely produced AP- and GFP-positive colonies, whereas the OSK-induced formation of AP- and GFP-positive colonies was greatly increased in Kap1-overexpressed iPSCs (Fig. 7e, f). The reprogramming efficiency induced by OSK + Kap1 is almost comparable to that induced by OSKM, suggesting that Kap1 can replace c-Myc in the reprogramming of somatic cells. Moreover, Kap1 overexpression did not increase expression of exogenously transfected c-Myc in MEFs (Fig. S5), in contrast to the Kap1-dependent increase of endogenous c-Myc in ESCs (Fig. 3d). These results suggest that Kap1 stimulates reprogramming of somatic cells through mechanisms involving Oct4, but not c-Myc.

Fig. 7. Effects of the K133/K137 ubiquitination site mutation of Oct4 on Oct4-induced somatic cell reprogramming.

a Knockdown or overexpression of Kap1 in Oct4-GFP MEFs. The expression levels of Kap1 and GAPDH in the control, Kap1-silenced, and -overexpressed Oct4-GFP MEFs were determined by western blotting. b The effects of Kap1 knockdown or overexpression on the OSKM-induced reprogramming of Oct4-GFP MEFs. Oct4-GFP cells were stained with AP staining on day 10. c The GFP-positive colonies were captured by confocal microscopy (left panel), and was counted from the images. Scale bar = 500 μm. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 9). d The GFP-positive population was measured by flow cytometric analysis. e The effect of Kap1 overexpression on OSK-induced reprogramming of Oct4-GFP MEFs. iPSC colonies were visualized with AP staining, and GFP-positive colonies were photographed (left panel). The number of GFP+ colonies was quantified 10 days after OSK expression (right panel). Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 9). (Scale bar = 300 μm). f The percentage of GFP-positive cells was quantified by flow cytometry analysis on 21 days. g Western blot analysis of Oct4 protein levels in Oct4-GFP MEFs infected with either a retrovirus encoding Oct4WT or Oct4K133R/K137R. h Representative images of AP+ colonies (upper images) and Oct4-GFP+ colonies (lower images) in Oct4-GFP MEFs infected with OSKM or OK133R/K137RSKM. The number of GFP+ colonies was counted on day 10. Scale bar = 300 μm. i The relative reprogramming efficiencies were determined by measuring the Oct4-GFP+ population using flow cytometry. j Representative images of AP+ colonies (upper images) and Oct4-GFP+ colonies (lower images) in Oct4-GFP MEFs infected with OWTSK or OK133R/K137RSK. The number of GFP+ colonies was counted on 25 days after the expression of OWTSK or OK133R/K137RSK. Scale bar = 500 μm. k The relative reprogramming efficiencies were determined by measuring the Oct4-GFP+ population using flow cytometry.

To explore whether the Oct4 ubiquitination site mutant (K133R/K137R) that facilitates the reprogramming of somatic cells, Oct4WT, or Oct4K133R/K137R was expressed along with Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc in Oct4-GFP MEFs. The Oct4K133R/K137R mutant exhibited a greater expression level than Oct4WT (Fig. 7g). Oct4K133R/K137R MEFs generated more AP- and Oct4-GFP-positive colonies than Oct4WT MEFs (Fig. 7h, i). Moreover, in the absence of c-Myc, the retroviral overexpression of Sox2 and Klf4 in Oct4K133R/K137R MEFs generated more AP- and Oct4-GFP-positive colonies than in Oct4WT MEFs (Fig. 7j, k). These results suggest that Oct4K133R/K137R augments the reprogramming efficiency of somatic cells due to its increased stability.

Discussion

The “core” stemness factors, Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog, have been recognized to be essential in vivo and in vitro for the early development and maintenance of pluripotency [14]. In ESCs, the dosage of Oct4 is crucial: reduced expression induces trophectoderm development, whereas enhanced expression drives primitive endoderm differentiation [38], suggesting that expression levels of the core stemness factors determine the pluripotency of ESCs. Upon deprivation of LIF, control ESCs spontaneously differentiated, whereas Kap1-ESCs retain their undifferentiated morphology. Consistently, Dox-induced Kap1 overexpression increased the protein levels of not only Oct4 but also Sox2 and Nanog in Kap1-ESCs without affecting the mRNA levels of Sox2 and Nanog (Fig. S6). Kap1-overexpressed ESCs exhibited longer half-life of endogenous Sox2 and Nanog proteins than control ESCs (Fig. S7). These results suggest that Kap1 may acts as a master regulator in proteasomal degradation of the core stemness factors. We showed that Kap1 directly interacts with Oct4 and interferes Itch-mediated ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of Oct4. Therefore, it is plausible to suggest that Kap1 protects the core stemness factors from proteasomal degradation through interaction with the stemness factors. In addition, we have shown that Kap1 overexpression augments the expression of G1 cyclins, such as cyclins D1 and D3, in ESCs. G1 cyclins have been reported to promote the protein stability of core stemness factors by inhibiting polyubiquitination and protecting them from proteasomal degradation [30], suggesting a potential role of G1 cyclins in the Kap1-stimulated protein stability of core stemness factors. The molecular mechanism implicated in the Kap1-mediated regulation of protein stability of core stemness factors needs to be clarified further.

It has been documented that stem cell function is regulated by the proteolytic degradation of stem cell factors via the ubiquitin-proteasome system in ESCs [7]. In the present study, we found that overexpression of Kap1 reduced Oct4 ubiquitination, whereas knockdown of Kap1 enhanced the ubiquitination of Oct4. It was shown that Kap1 regulates the protein stability of the full-length and POU domains of Oct4. To date, two E3 ubiquitin ligases, Wwp2 and Itch, have been implicated in the ubiquitination of Oct4 [36, 39]. Wwp2 has been reported to promote Oct4 protein degradation during the differentiation of ESCs; however, it did not affect Oct4 ubiquitination and protein levels in undifferentiated mouse ESCs [39]. Itch has been reported to regulate the protein stability of Oct4, and knockdown of Itch comprised the self-renewal capacity of mouse ESCs and somatic cell reprogramming efficiency [36]. In the present study, we demonstrated that K133, K137, and K199 might be associated with the Itch-mediated degradation of Oct4, and the ubiquitination of Oct4 at K133 is entirely abrogated by Kap1 overexpression. These results suggest that Kap1 interferes with the Itch-mediated ubiquitination of the POU domain of Oct4 at K133, thereby increasing Oct4 stability. In accordance with these results, it has been documented that Oct4 mutations of five lysine residues (K118, K121, K133, K137, and K144) are associated with the Wwp2 E3 ligase for Oct4 ubiquitination, that results in enhanced Oct4 stability and thus ensures high reprogramming efficiency levels [40]. Therefore, these results suggest that Kap1 interferes with the Itch-mediated ubiquitination of Oct4 and subsequent proteolytic degradation, thereby increasing the protein stability of Oct4 (Fig. 6h).

In summary, the present study demonstrated a pivotal role of Kap1 as a master regulator of the protein stability of core stemness factors, including Oct4. Kap1 regulates the pluripotency of ESCs and promotes somatic cell reprogramming by inhibiting the Itch-mediated ubiquitination of Oct4. The present study suggests that the overexpression of either the Kap1 or the Oct4K133R/K137R mutant may be useful for enhancing the reprogramming efficiency by increasing the protein stability of Oct4 and stemness factors.

Supplementary information

Funding

This research was supported by programs (NRF-2015R1A5A2009656, NRF-2015M3A9C6030280, NRF-2017M3A9B4051542, and NRF-2020R1A2C2011654) of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by R. De Maria

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41418-020-00613-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF, Johnstone SE, Levine SS, Zucker JP, et al. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2005;122:947–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–20. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young RA. Control of the embryonic stem cell state. Cell. 2011;144:940–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heng JC, Ng HH. Transcriptional regulation in embryonic stem cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;695:76–91. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7037-4_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loh YH, Wu Q, Chew JL, Vega VB, Zhang W, Chen X, et al. The Oct4 and Nanog transcription network regulates pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Genet. 2006;38:431–40. doi: 10.1038/ng1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strikoudis A, Guillamot M, Aifantis I. Regulation of stem cell function by protein ubiquitylation. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:365–82. doi: 10.1002/embr.201338373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai N, Li M, Qu J, Liu GH, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Post-translational modulation of pluripotency. J Mol Cell Biol. 2012;4:262–5. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjs031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buckley SM, Aranda-Orgilles B, Strikoudis A, Apostolou E, Loizou E, Moran-Crusio K, et al. Regulation of pluripotency and cellular reprogramming by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:783–98. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scholer HR, Ruppert S, Suzuki N, Chowdhury K, Gruss P. New type of POU domain in germ line-specific protein Oct-4. Nature. 1990;344:435–9. doi: 10.1038/344435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nichols J, Zevnik B, Anastassiadis K, Niwa H, Klewe-Nebenius D, Chambers I, et al. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell. 1998;95:379–91. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pesce M, Scholer HR. Oct-4: gatekeeper in the beginnings of mammalian development. Stem Cells. 2001;19:271–8. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-4-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Do JT, Scholer HR. Regulatory circuits underlying pluripotency and reprogramming. Trends Pharm Sci. 2009;30:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J, Chu J, Shen X, Wang J, Orkin SH. An extended transcriptional network for pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;132:1049–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishimoto M, Miyagi S, Yamagishi T, Sakaguchi T, Niwa H, Muramatsu M, et al. Oct-3/4 maintains the proliferative embryonic stem cell state via specific binding to a variant octamer sequence in the regulatory region of the UTF1 locus. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5084–94. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.12.5084-5094.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esch D, Vahokoski J, Groves MR, Pogenberg V, Cojocaru V, Vom Bruch H, et al. A unique Oct4 interface is crucial for reprogramming to pluripotency. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:295–301. doi: 10.1038/ncb2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sripathy SP, Stevens J, Schultz DC. The Kap1 corepressor functions to coordinate the assembly of de novo HP1-demarcated microenvironments of heterochromatin required for KRAB zinc finger protein-mediated transcriptional repression. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8623–38. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00487-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urrutia R. KRAB-containing zinc-finger repressor proteins. Genome Biol. 2003;4:231. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-10-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedman JR, Fredericks WJ, Jensen DE, Speicher DW, Huang XP, Neilson EG, et al. KAP-1, a novel corepressor for the highly conserved KRAB repression domain. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2067–78. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.16.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iyengar S, Farnham PJ. Kap1 protein: an enigmatic master regulator of the genome. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:26267–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.252569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rowe HM, Kapopoulou A, Corsinotti A, Fasching L, Macfarlan TS, Tarabay Y, et al. Trim18 repression of retrotransposon-based enhancers is necessary to preserve transcriptional dynamics in embryonic stem cells. Genome Res. 2013;23:452–61. doi: 10.1101/gr.147678.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doyle JM, Gao J, Wang J, Yang M, Potts PR. MAGE-RING protein complexes comprise a family of E3 ubiquitin ligases. Mol Cell. 2010;39:963–74. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ivanov AV, Peng H, Yurchenko V, Yap KL, Negorev DG, Schultz DC, et al. PHD domain-mediated E3 ligase activity directs intramolecular sumoylation of an adjacent bromodomain required for gene silencing. Mol Cell. 2007;28:823–37. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ziv Y, Bielopolski D, Galanty Y, Lukas C, Taya Y, Schultz DC, et al. Chromatin relaxation in response to DNA double-strand breaks is modulated by a novel ATM- and KAP-1 dependent pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:870–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seki Y, Kurisaki A, Watanabe-Susaki K, Nakajima Y, Nakanishi M, Arai Y, et al. TIF1beta regulates the pluripotency of embryonic stem cells in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10926–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907601107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klimczak M, Czerwinska P, Mazurek S, Sozanska B, Biecek P, Mackiewicz A, et al. TRIM28 epigenetic corepressor is indispensable for stable induced pluripotent stem cell formation. Stem Cell Res. 2017;23:163–72.. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ying QL, Wray J, Nichols J, Batlle-Morera L, Doble B, Woodgett J, et al. The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature. 2008;453:519–23. doi: 10.1038/nature06968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kyba M, Perlingeiro RC, Daley GQ. HoxB4 confers definitive lymphoid-myeloid engraftment potential on embryonic stem cell and yolk sac hematopoietic progenitors. Cell. 2002;109:29–37. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00680-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Do EK, Cheon HC, Jang IH, Choi EJ, Heo SC, Kang KT, et al. Reptin regulates pluripotency of embryonic stem cells and somatic cell reprogramming through Oct4-dependent mechanism. Stem Cells. 2014;32:3126–36. doi: 10.1002/stem.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu L, Michowski W, Inuzuka H, Shimizu K, Nihira NT, Chick JM, et al. G1 cyclins link proliferation, pluripotency and differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:177–88. doi: 10.1038/ncb3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kozar K, Ciemerych MA, Rebel VI, Shigmatsu H, Zagozdzon A, Sicinska E, et al. Mouse development and cell proliferation in the absence of D-cyclins. Cell. 2004;118:477–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neganova I, Lako M. G1 to S phase cell cycle transition in somatic and embryonic stem cells. J Anat. 2008;213:30–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00931.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stead E, White J, Faast R, Conn S, Goldstone S, Rathjen J, et al. Pluripotent cell division cycles are driven by ectopic Cdk2, cyclin A/E and E2F activities. Oncogene. 2002;21:8320–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith AG, Heath JK, Donaldson DD, Wong GG, Moreau J, Stahl M, et al. Inhibition of pluripotential embryonic stem cell differentiation by purified polypeptides. Nature. 1988;336:688–90. doi: 10.1038/336688a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nichols J, Smith A. Naive and primed pluripotent states. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:487–92. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liao B, Zhong X, Xu H, Xiao F, Fang Z, Gu J, et al. Itch, an E3 ligase of Oct4, is required for embryonic stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency induction. J Cell Physiol. 2013;228:1443–51. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suresh B, Lee J, Kim KS, Ramakrishna S. The Importance of Ubiquitination and Deubiquitination in Cellular Reprogramming. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:6705927. doi: 10.1155/2016/6705927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niwa H, Miyazaki J, Smith AG. Quantitative expression of Oct-3/4 defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat Genet. 2000;24:372–6. doi: 10.1038/74199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu H, Wang W, Li C, Yu H, Yang A, Wang B, et al. WWP2 promotes degradation of transcription factor Oct4 in human embryonic stem cells. Cell Res. 2009;19:561–73. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li S, Xiao F, Zhang J, Sun X, Wang H, Zeng Y, et al. Disruption of Oct4 ubiquitination Increases Oct4 protein stability and ASH2L-B-mediated H3K4 methylation promoting pluripotency acquisition. Stem Cell Rep. 2018;11:973–87.. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.