Abstract

The role of histone ubiquitination in directing cell lineage specification is only poorly understood. Our previous work indicated a role of the histone 2B ubiquitin ligase RNF40 in controlling osteoblast differentiation in vitro. Here, we demonstrate that RNF40 has a stage-dependent function in controlling osteoblast differentiation in vivo. RNF40 expression is essential for early stages of lineage specification, but is dispensable in mature osteoblasts. Paradoxically, while osteoblast-specific RNF40 deletion led to impaired bone formation, it also resulted in increased bone mass due to impaired bone cell crosstalk. Loss of RNF40 resulted in decreased osteoclast number and function through modulation of RANKL expression in OBs. Mechanistically, we demonstrate that Tnfsf11 (encoding RANKL) is an important target gene of H2B monoubiquitination. These data reveal an important role of RNF40-mediated H2B monoubiquitination in bone formation and remodeling and provide a basis for exploring this pathway for the treatment of conditions such as osteoporosis or cancer-associated osteolysis.

Subject terms: Histone post-translational modifications, Epigenetics

Introduction

Bone is a highly dynamic tissue and undergoes continuous remodeling to maintain normal skeletal function and structure. In general, normal bone function and homeostasis depend on communication of bone-forming osteoblasts (OBs), matrix embedded osteocytes, and bone-resorbing osteoclasts (OCs). In response to signaling hormones and cytokines, OBs and osteocytes stimulate generation of OCs from monocytes that proliferate and fuse to giant multinuclear bone-resorbing cells leading ultimately to bone resorption. On the other hand, activation of bone resorption and the subsequent release of matrix products lead to the recruitment and differentiation of OB progenitors. Importantly, the tight coupling of bone resorption to bone formation in time and space is very critical for the maintenance of skeletal structure [1].

The primary event in bone formation is differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cells into OBs [2]. The early expression of runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) with subsequent induction of Osterix directs mesenchymal progenitor cell differentiation along the osteogenic path [3].

In our previous work, we demonstrated that the differentiation of human mesenchymal stromal cells to the osteoblastic lineage is dependent on the global levels of histone 2B monoubiquitination at lysine 120 (H2Bub1) [4]. H2Bub1 is a conserved histone modification and is carried out by an obligate heterodimeric complex of the E3 ubiquitin ligases RNF20 and RNF40 in mammals [5]. H2Bub1 has been primarily identified as an activating mark localized to the transcribed region (TR) of genes and associated with transcriptional elongation [6, 7]. In fact, H2Bub1 has been implicated in nucleosome reassembly [8] and its occupancy is tightly coupled to the elongation rate of RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) [9]. Moreover, the transcription modulatory effect of H2Bub1 was demonstrated, in part, to be dependent on histone crosstalk. Namely, H2Bub1 has been reported to be required for histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4) and lysine 79 (H3K79) methylation, which are also associated with gene activation [10–12]. Interestingly, recent data also suggest a central role of H2Bub1 in controlling the resolution of “bivalency” associated with H3K4 and lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K4me3/H3K27me3) by direct or indirect mechanisms [13].

However, despite its general association with transcription, loss of RNF20/40 elicits a selective effect on gene expression [14, 15]. Surprisingly, genes harboring low H2Bub1 and broader H3K4me3 levels appear to be more sensitive to loss of RNF40 [15]. Moreover, a growing body of evidence suggests a role of H2Bub1 in the regulation of stimulus-induced gene expression programs such as those regulated by cellular differentiation [4, 16–18], estrogen [19, 20], epidermal growth factor [14], androgen [21], or NFκB activation [22].

In the current study, we investigated the biological relevance of RNF40-driven H2B monoubiquitination in the OB lineage for bone integrity. By conditional deletion of Rnf40 in the OB lineage in mice, we demonstrate now that RNF40 is specifically required for earlier stages of OB commitment, but not for later stages. Consistently, RNF40 is specifically required for differentiation-induced gene expression and loss of H2Bub1 on these genes correlated with decreased occupancy of RNAPII. Moreover, we discovered a previously unknown function of RNF40 in regulating vitamin D-dependent gene expression. As a result, RNF40-deficient cells lacked Tnfsf11 expression and failed to activate OCs. This manifested in reduced bone resorption in conditional OB-specific Rnf40 knockout mice and increased bone mass. Taken together, these data define critical roles of RNF40-mediated H2B monoubiquitination in bone biology through its involvement in OB fate determination and vitamin D signaling.

Materials and methods

Animal studies

The animal studies were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the Institutional Guidelines for Humane Use of Animals in Research. The Rnf40 floxed mice were generated as described [15]. The mouse lines Rosa-CreERT2, Bglap-Cre, Dmp1-Cre, and Runx2-Cre were described by Ventura et al. [23], Lu et al. [24], Zhang et al. [25], and Rauch et al. [26], respectively. All the lines were generated in a C57BL/6N background.

For the skeletal preparations, mice were injected twice with calcein (Sigma, Cat# C0875) solution 9 days and 2 days prior to sacrifice at 6 weeks of age after reaching the size of an adult mouse. Both genders developed similar phenotypes and subsequent analyses were then performed on the bones of male mice. Mice were euthanized with carbon dioxide. The skin and inner organs of the animals were removed. One of the tibiae of the analyzed mice was removed and snap-frozen for DNA and RNA isolations. The rest of the skeleton with muscles were fixed for 3 days in 4% PFA solution, after which the skeletons were washed with tap water and transferred into 70% ethanol for long term storage.

Cell culture, differentiation treatments, small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfections, and stainings

Calvarial OBs were isolated from 1–3-day-old neonatal pups as previously described [27] with subsequent sequential digestion in α-MEM (Life Technologies) containing 2 mg/ml dispase (Gibco) and 1 mg/ml collagenase A (Sigma). The cells were maintained in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% P/S at 37 C in 5% CO2 incubators up to passage 6–7. For induction of Cre-recombinase mediated deletion of the Rnf40 gene, the cells were treated for 7 days with 250 nM of 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (Sigma) or an equal volume of 100% ethanol. Then, the cells were washed twice to remove the TAM and were further maintained for 2 additional days in medium lacking TAM. At this timepoint, cells of the undifferentiated state (defined as day 0 in the study) were harvested. The rest of the cells were treated with 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.2 mM ascorbate (for differentiation studies), or with 10 nM calcitriol (Biomol). The media were replaced every second day.

OCs were isolated from 6–8-week-old mice by flushing the marrow cells with αMEM containing 10% FBS. The cell suspension was seeded in TC-treated culture dish to allow adhering of monocytes/macrophages. The cells were maintained in the presence of M-CSF (R&D systems) at 37 °C in 5% CO2 incubators.

For OB–OC coculture experiments, calvarial OBs from mutant Rnf40Rosa-CreERT2 following 7 days of TAM treatment (as previously described) were seeded at 4000 cells/well into 96-well plates in α-MEM complete medium containing 10 nM vitamin D (calcitriol). The next day, 200,000 OC progenitor cells from wild-type (WT) animals were seeded into OB containing wells. On days 4 and 7 the media was refreshed and vitamin D was added as indicated. On day 10, cells were fixed and subjected to tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining.

MC3T3-E1 cells were maintained in complete α-MEM with 10% FBS and 1X P/S medium at 37 °C in 5% CO2 incubators. For transient knockdown of genes, cells were transfected with siRNA (Dharmacon, siGENOME nontargeting siRNA (NT5) D-001210-05-50—UGGUUUACAUGUCGACUAA; mouse RNF40 siRNA smartpool D-059014-01, D-059014-02, D-059014-03, D-059014-04—AACGAGACCGAAGAGAAA, ACUCUGAGCUCCAAGAUAA, GAUCAAGGCCAACCAGAUU, GGAGGUCGUUCGUGAGACA) using the Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For the experiment with knockdown of RNF40 following differentiation, 250,000 cells (for six-well format) were transfected with RNF40 siRNA smartpool for 24 h. At this point, the undifferentiated samples were harvested, while differentiation was induced with 5 mM β-glycerophosphate and 0.2 mM ascorbate for the rest. After 48 h, the differentiated cells were harvested.

For the experiment with induction of differentiation with subsequent knockdown of RNF40, the MC3T3-E1 cells were seeded into six-well plates, and 24 h later, the undifferentiated controls were harvested, and in the rest of the wells, differentiation was induced. Knockdown was performed 72 h post differentiation. Cells were trypsinized and transferred into the wells with transfection mix containing the corresponding siRNAs. Cells were then harvested 72 h post transfection (6 days after induction of differentiation).

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining of OBs and TRAP staining of OCs was performed using the alkaline phosphatase leukocyte kit (Sigma) and acid phosphatase leukocyte kit (Sigma), respectively, following the manufacturer’s instructions. For ALP staining visualization, the whole plates were scanned. For TRAP-staining visualization, the stained plates were analyzed and counted under 40X magnification using a Leica DMI6000B microscope.

For alizarin red staining the cells were fixed for 15 min with 4.2% formaldehyde in PBS. Following fixation, the cells were washed twice with DI water and stained with alizarin red staining solution for 15 min. For visualization, the plates were scanned.

Western blot, RNA isolation, qRT-PCR, and genotyping

Protein and RNA isolations, reverse transcription, western blot, and ChIP experiments were performed as previously described [28]. Genotyping was done using the Mouse Direct PCR Kit (Absource Diagnostics) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

The list of antibodies and oligonucleotides used in the study are provided in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

mRNA- and ChIP-sequencing library preparation

After confirming RNA integrity via agarose gel electrophoresis, 500 ng–1 µg of total RNA was used for library preparation using the NEXTflex Rapid Directional RNA-Seq Kit (for RNA-Seq from differentiated calvarial OBs) and TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit-v2 (for RNA-Seq from vitD-treated calvarial OBs) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

ChIP-seq libraries were generated using the MicroPlex Library Preparation Kit (Diagenode) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Pooled libraries were used for cluster generation on cBot followed by 51 bp single-end sequencing on HiSeq 4000 from Illumina performed at the NGS Integrative Genomics (NIG) Core Unit of the University Medical Center (UMG) in Göttingen, Germany.

All the RNA and ChIP-seq libraries were prepared in duplicate (n = 2) or triplicate (n = 3).

µCT analysis of bones

Bones (femora and vertebrae) were scanned using a Skyscan 1176 in vivo microcomputer tomography or µCT (Bruker, Kontich, Belgium as previously described [29]. The size parameters of the bones were identified as follows: for torso—the length from the atlas to the sacrum; for femur—the length from the fovea capitis to the patella; and for vertebra—the length of L5 vertebral body.

Bone histomorphometry

The dual calcein-labeled bones embedded into plastic were utilized for measurement of bone formation rate (BFR) and mineral apposition rate (MAR) based on the width of the two green lines, which is indicative of bone growth between two injection time points (7 days). The analysis and evaluation were performed by Osteomeasure Software (OsteoMetrics, Decatur, USA).

For OB and osteocyte number estimation, toluidine blue staining was performed on DE Plastic and rehydrated slides with subsequent incubation in 0.1% toluidine blue solution made in 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer for the duration of 3–10 min. The number of OBs (N.Obs) and osteocytes were evaluated on Osteomeasure Software (OsteoMetrics, Decatur, USA).

For OC number estimation, the paraffin-embedded bones were subjected to deparaffinization and rehydration. The rehydrated bones were incubated for 10 min in TRAP buffer consisting of 0.328% (w/v) sodium acetate and 0.23% (w/v) di-sodium tartrate with pH 5 adjusted with HCl. Subsequently, the slides were incubated for 2–4 h at 37 °C in TRAP-staining solution consisting of 10% (w/v) naphthol-AS-bi-phosphate (Sigma) and 1% (v/v) dimethylformamide mixed with subsequent addition of TRAP buffer, 60% (w/v) Fast Red Violet LB Salt (Sigma), and 0.5% (v/v) Triton X 100. The number of OCs identified by red-pink color with blue-violet nucleus and OC surface was identified using the Osteomeasure Software (OsteoMetrics, Decatur, USA).

Statistical analyses

The relative gene expression was quantified based on a standard curve made from serial (1:4) dilutions of control samples. All qRT-PCR samples were normalized to an internal reference gene and displayed relative to the control sample. Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA, v 5.04). Individual p values are indicated in the figure legends. Data are represented by the mean and standard deviation.

For animal studies, generally six animals were selected for each genotype analyzed. T-test was performed for statistical analysis to compare the effects of Rnf40 deletion with WT condition.

Sequencing data analyses

For ChIP-seq data analyses, the fastq files were mapped to the mouse reference genome assembly mm9 using Bowtie2 v 2.3.4.1 [30] with very sensitive end-to-end mode. The obtained BAM files were filtered with MAPQ ≥ 2 and PCR duplications were removed using SAMTOOLS 1.9 [31]. Then the filtered BAM files from each replicate were merged within one condition using SAMTOOLS and the merged BAM files were normalized to 1× depth of coverage (reads per genomic content, RPGC) using Deeptools 3.0.1 [32] bamCoverage. The obtained bigwig files were visualized on IGV [33] and used to make average profile plots using Deeptools computeMatrix and plotProfile functions.

For RNA-seq analyses, fastq files were mapped to the mouse reference genome assembly mm9 using TopHat2 2.1.0 [34] with very sensitive Bowtie2 settings. The differentially expressed genes were obtained for each set of comparisons using Cuffdiff 2.2.1 [35, 36] with default settings. The threshold values to determine the differentiation-induced genes (DIF_VEH versus UND_VEH conditions) were as follows: FPKM DIF_VEH ≥ 5; log2 (fold_change) ≥ 0.7, and q_value ≤ 0.05). Altogether 576 genes were found to be significantly upregulated upon differentiation. These genes then were sorted based on dependency on RNF40, i.e., genes that showed tendency to be downregulated upon RNF40 KO (DIF_TAM versus DIF_VEH) with thresholds log2 (fold_change) ≤ −0.5, and q_value ≤ 0.05 (n = 440 genes). The remaining number of the genes (136) was assigned to the “rest” group. These two groups of genes were used to produce the average profiles for H3K4me3, H2Bub1, and RNAPII occupancy.

All RNF40-regulated genes in differentiated OBs (i.e., genes up- and downregulated with Rnf40 deletion; DIF_TAM versus DIF_VEH) were identified based on the following thresholds: FPKM DIF_VEH ≥ 5; abs|log2 (fold_change)| ≥ 1, and q_value ≤ 0.05. These genes were used to make the heatmap using the heatmap.2 from gplots package on R 3.6.0 (http://www.R-project.org/). These genes were also subjected to gene ontology analyses (GO BP) using the Gene Ontology Resource software (release 201907-01) [37]. Top GO terms with lowest FDR (<0.05) were selected for visualization.

The vitamin D-induced genes (i.e., genes upregulated upon vitD treatment; VitD_vs_DMSO) were identified based on the following thresholds: FPKMVitD ≥ 5; log2 (fold_change) ≥ 0.8, and q_value ≤ 0.05. These genes were then sorted based on RNF40 dependency, which is displayed as a volcano plot produced with the EnhancedVolcano package [38] on R. Here, all the significantly up- and downregulated genes with abs|log2 (fold_change)| ≥ 1 and q_value ≤ 0.05 are shown in red; all the significantly up- and downregulated genes with abs|log2 (fold_change)| ≤ 1 and q_value ≤ 0.05 in blue and the rest of the genes are shown in black color. Similarly, the subset of VitD-induced genes downregulated upon RNF40 KO (VitD+TAM versus VitD) with FPKM VitD ≥ 5; log2 (fold_change) ≤ −1, q_value ≤ 0.05 were fed into GO analyses software and the top GO terms with FDR < 0.05 are shown.

Results

RNF40 is required for differentiation of calvarial pre-OBs

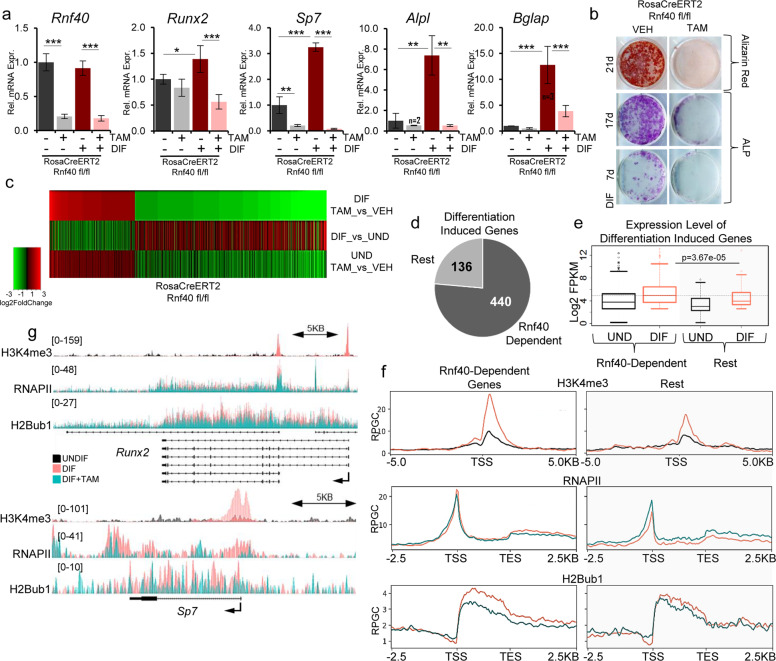

Given its positive role in regulating osteoblastic differentiation of human multipotent stem cells [4], we sought to delineate the H2Bub1-driven epigenetic mechanisms governing OB fate determination and maintenance. We used calvarial cells isolated from inducible Rnf40RosaCreERT2 mutant neonatal mice, which represent the preosteoblastic stage of OB differentiation. Consistent with our previous findings in human mesenchymal stromal cells, genetic loss of Rnf40 expression and the subsequent loss of H2Bub1 (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b) dramatically decreased the differentiation-induced expression of OB-marker genes (Alpl, Bglap) including the master regulators Runx2 and Sp7 (Fig. 1a). These effects were not due to 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Tam) treatment, since Tam treatment of Rnf40RosaCreERT2 WT cells did not appreciably affect marker gene expression (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Consistently, RNF40-deficient OBs displayed less ALP activity and failed to form mineralized matrix (Fig. 1b). Notably, based on transcriptome-wide analysis of RNF40-deficient calvarial OBs, RNF40 mainly exerted a differentiation-specific effect reverting the expression of differentiation-induced genes (Fig. 1c). In fact, genes downregulated upon RNF40 loss (Supplementary Table 1) were mainly enriched in pathways associated with bone development and growth (Table 1). In contrast, genes that were upregulated in differentiating RNF40-deficient OBs were enriched in diverse pathways (Supplementary Table 2) including the “negative regulation of ERK1 and ERK2 cascade and MAP kinase activity,” which has been implicated in having positive roles for osteoblastogenesis [39, 40]. Consistent with our previous findings [15], RNF40-dependent genes (i.e., all the genes downregulated in RNF40-deficient OBs) generally displayed lower H2Bub1 occupancy compared to the rest, i.e., RNF40-independent genes (Supplementary Fig. 1d) both in the differentiated as well as in the undifferentiated state. As expected, the majority of differentiation-induced genes (genes upregulated upon differentiation with a log2 fold change ≥ 0.7 and q value ≤ 0.05, see Supplementary Table 1) was RNF40 dependent (≈76%, Fig. 1d). Interestingly, within this group of genes RNF40-dependent genes displayed higher expression levels upon differentiation (Fig. 1e), correlating with higher H2Bub1, H3K4me3, and RNAPII levels (Supplementary Fig. 1e, Fig. 1f, compare orange lines in right and left panels). This supports a central role of RNF40-mediated H2B monoubiquitination in the regulation of these genes. Consistently, downregulation of these genes in response to Rnf40 deletion resulted in a substantial decrease in H2Bub1 and a slight decrease in RNAPII occupancy across the gene body (Fig. 1f, compare green and orange lines in left panels). In contrast, the remaining genes (“rest” group, right panels) displayed increases in RNAPII occupancy, suggesting that different mechanisms are involved in the regulation of RNF40-independet genes. Consistently, both master regulators Runx2 and Sp7 are important RNF40-regulated genes that display decreased RNAPII occupancy upon H2Bub1 loss following Rnf40 deletion (Fig. 1g). Taken together, these observations suggest that differentiation-induced gene expression changes are under the control of RNF40-dependent H2B monoubiquitination.

Fig. 1. RNF40 is required for the differentiation of calvarial osteoblasts.

a Gene expression analysis from primary calvarial osteoblasts from Rnf40Rosa-CreERT2 mouse, which were treated for 7 days with 250 nM 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (TAM) or equivalent volume of 100% ethanol (VEH) and subjected to differentiation for another 7 days. Mean ± SD, n = 4, unless otherwise indicated in the figure. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test was used for statistical analysis where ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. b Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and alizarin red staining of primary osteoblasts from Rnf40Rosa-CreERT2 mice following differentiation for 7, 17, or 21 days. c The mRNA-Seq heatmap shows log2 fold change values of genes in Rnf40-deleted (TAM) versus control (VEH) treated cells in the differentiated state (top), control treated cells in differentiated versus undifferentiated state (middle); or Rnf40-deleted cells versus control in the undifferentiated state (bottom). Genes up- and downregulated (abs. log2 fold change value ≥ 1, q value ≤ 0.05) in Rnf40-deleted versus the control condition in differentiated state were selected for the heatmap. d Differentiation-induced genes (log2 fold change value ≥ 0.8, q value ≤ 0.05) were classified based on RNF40 regulation (log2 fold change ≤ −0.5, q value ≤ 0.05) as “RNF40 dependent” in contrast to the “rest” of differentiation-induced genes. e The boxplots depict the expression values of the genes from both groups, as defined in d both in undifferentiated (black) and differentiated state (orange). f Average occupancy depicted as RPGC (reads per genomic content) of H3K4me3 ChIP-seq signal in MC3T3-E1 cells in undifferentiated (black) and differentiated state (orange) (top); RNAPII (middle); and H2Bub1 (below) from Rnf40Rosa-CreERT calvarial osteoblasts in differentiated control (orange) and Rnf40 knockout (petrol green) conditions across the differentiation-induced “RNF40 dependent” and “rest” groups of genes. g Average occupancy of H3K4me3 in MC3T3-E1 cells in undifferentiated and differentiated state (top); RNAPII (middle); and H2Bub1 (below) from calvarial osteoblasts in differentiated control and Rnf40 knockout conditions across Runx2 (upper panel) and Sp7 (lower panel).

Table 1.

Gene ontology analysis (GO) for biological process (BP) was performed on genes downregulated in differentiated osteoblasts upon Rnf40 knockout.

| GO term | REFLIST | RNF40_DN n = 1248 | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endochondral bone morphogenesis (GO:0060350) | 73 | 23 | 3.58E−07 |

| Cartilage development involved in endochondral bone morphogenesis (GO:0060351) | 49 | 18 | 2.84E−06 |

| Endochondral bone growth (GO:0003416) | 40 | 16 | 6.71E−06 |

| Bone growth (GO:0098868) | 43 | 16 | 1.27E−05 |

| Growth plate cartilage development (GO:0003417) | 33 | 14 | 2.25E−05 |

| Chondrocyte development (GO:0002063) | 41 | 15 | 3.34E−05 |

| Chondrocyte differentiation involved in endochondral bone morphogenesis (GO:0003413) | 29 | 13 | 3.46E−05 |

| Collagen fibril organization (GO:0030199) | 49 | 16 | 0.000045 |

| Growth plate cartilage chondrocyte differentiation (GO:0003418) | 22 | 11 | 0.00012 |

| Glutathione metabolic process (GO:0006749) | 49 | 15 | 0.000179 |

Conditional Rnf40Runx2Cre knockout mice display decreased bone formation, but a high bone mass phenotype

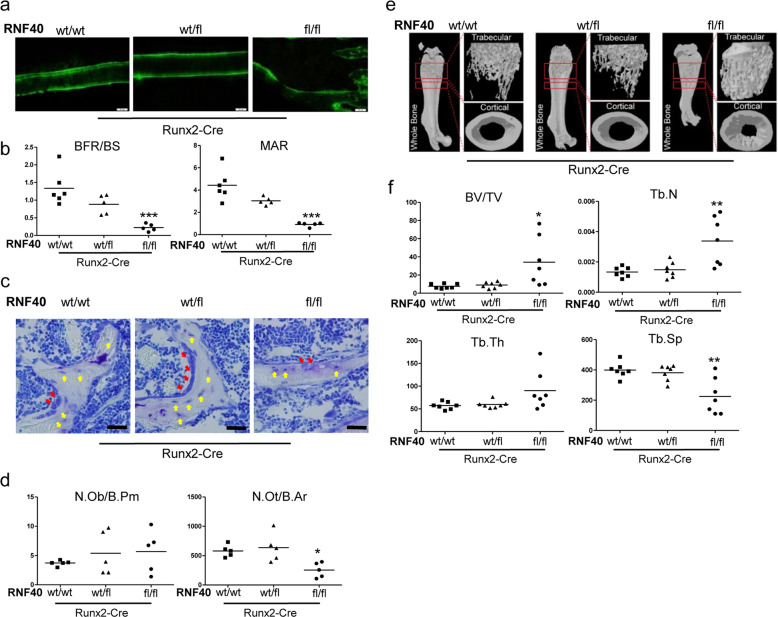

To determine the function of RNF40 in normal bone formation and development, we used an in vivo conditional knockout approach. We crossed Runx2-Cre-expressing mice [26] with a mouse line carrying a floxed Rnf40 allele [15] leading to the efficient excision of the Rnf40 allele during early OB differentiation (Supplementary Fig. 2a). RUNX2 is a transcription factor (TF) and a master regulator of OB-lineage commitment [41, 42]. Conditional Rnf40Runx2Cre mice displayed significantly lower bone formation (BFR) and matrix apposition rates (MAR) (Fig. 2a, b). Although the number of osteoblasts (N.Obs) was not significantly affected in these mice, RNF40-deficient OBs were impaired in their ability to form osteocytes, consistent with these cells having defects in their differentiation potential (Fig. 2c, d). Despite the lower bone formation capacity, the conditional Rnf40Runx2Cre mice displayed a dramatic osteopetrosis-like increase in bone mineral density as revealed by microCT analysis (Fig. 2e, f, Supplementary Fig. 2b–d), indicating a strong defect in bone turnover, which also resulted in decreased bone growth (Supplementary Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2. Conditional Rnf40Runx2Cre knockout mice display changes in bone formation and bone mass.

a Representative fluorescent micrographs of femur cortical bone of 6-week-old male mice from wild-type (wt/wt), heterozygous (wt/fl), and knockout (fl/fl) Rnf40Runx2-Cre mice showing double calcein labeling. b Bone formation rate per bone surface area (BFR/BS) and mineral apposition rate (MAR) were quantified in conditional 6-week-old Rnf40Runx2-Cre male mice used in the study. Student’s t test was used for statistics where ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. c Plastic-embedded femoral sections from wild-type (wt/wt), heterozygous (wt/fl), and knockout (fl/fl) Rnf40Runx2-Cre 6-week-old male mice were subjected to toluidine blue stainings on trabecular bone. Red arrows: osteoblasts. Yellow arrows: osteocytes. Bar: 20 µm. d The number of osteoblasts per bone perimeter (N.Ob/B.Pm) and number of osteocytes per bone area (N.Ot/B.Ar) were evaluated via “osteomeasure.” Student’s t test was used for statistics where ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 e Representative µCT reconstruction pictures of the femur of conditional Rnf40Runx2-Cre male mice at 6 weeks of age. The bones were analyzed using a SkyScan 1176 microCT. f Bone histomorphometric parameters in conditional Rnf40Runx2-Cre mice showing trabecular bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th.), trabecular separation (Tb. Sp.), and trabecular number (Tb.N.) of femora of male mice used in the study were determined according to guidelines by the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee.

Taken together, deletion of Rnf40 at early stages of OB commitment in mice led to a reduction of bone formation, but resulted in a high bone mass phenotype.

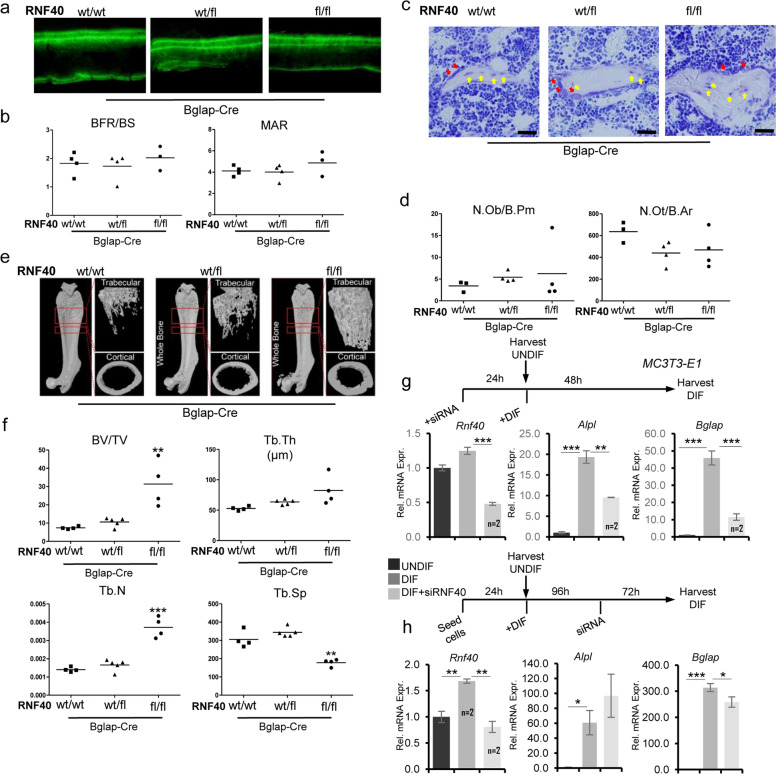

RNF40 exerts a stage-dependent function in OBs

To test whether Rnf40 deletion in later stages of OB differentiation similarly affects bone formation, we crossed Rnf40 floxed mice with a mouse line expressing Cre under the control of the osteocalcin (Bglap-Cre) promoter [25]. Recombination of the floxed Rnf40 allele also efficiently occurred in bones of the Rnf40BglapCre mice (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Interestingly, unlike Rnf40Runx2Cre mice, Rnf40BglapCre mice developed normally without any visual differences in skeletal size (Supplementary Fig. 3b) despite efficient deletion of the floxed Rnf40 allele in the bones (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Interestingly, in contrast to our observations in Rnf40Runx2Cre mice, analysis of calcein-labeled bone sections revealed no bone formation defects in Rnf40BglapCre mice (Fig. 3a, b). Consistently, neither OB nor osteocyte numbers were affected in Rnf40BglapCre mice (Fig. 3c, d). However, the microCT analysis of bones from these mice did reveal an increase in both cortical and trabecular bone mass (Fig. 3e, f, Supplementary Fig. 3d–f). Interestingly, deletion of Rnf40 mainly in late-stage OBs and osteocytes using the Dmp1-Cre mouse line [24] did not result in any changes in gross phenotype or bone mass (Supplementary Fig. 3g, h). These observations suggested that RNF40 may have stage-dependent functions during OB differentiation. Given the fact that Runx2 expression is a defining feature of early stage OBs (pre-OBs), while Bglap is expressed in OBs and Dmp1 in late-stage OBs and osteocytes, RNF40 appears to be essential for the maturation of Runx2-expressing OBs and play a negligible role in late-stage OBs and osteocytes. To test this hypothesis, we performed an siRNA-mediated knockdown of RNF40 in MC3T3-E1 cells either prior to the induction of differentiation or several days post differentiation (Fig. 3g, h). Consistent with our in vivo findings, the loss of RNF40 expression (Supplementary Fig. 3i) blocked the induction of marker genes such as Alpl and Bglap when RNF40 was depleted prior to differentiation, but were relatively unaffected by RNF40 depletion in cells that had already been differentiated for 4 days (Fig. 3g, h). Thus, RNF40 appears to be essential for the establishment, but not the maintenance of the OB gene expression program. Interestingly, these effects were specific to RNF40, since RNF20 not only blocked differentiation-induced gene expression changes, but also downregulated gene expression at later stages of OB differentiation (Supplementary Fig. 3j, k). Given the equal contribution of RNF20 and RNF40 to H2B monoubiquitination, these findings suggest that RNF20 may have additional H2Bub1-independent functions following lineage specification.

Fig. 3. RNF40 is dispensable in late-stage OBs.

a Representative fluorescent micrographs of femur cortical bone of 6-week-old from wild-type (wt/wt), heterozygous (wt/fl), and knockout (fl/fl) Rnf40Bglap-Cre male mice showing double calcein labeling. b Bone formation rate per bone surface area (BFR/BS) and mineral apposition rate (MAR) were quantified in conditional Rnf40Bglap-Cre male mice used in the study. c The plastic-embedded femoral sections from wild-type (wt/wt), heterozygous (wt/fl), and knockout (fl/fl) Rnf40Bglap-Cre 6-week-old male mice were subjected to toluidine blue stainings on trabecular bone. Red arrows: osteoblasts. Yellow arrows: osteocytes. Bar: 20 µm. d The number of osteoblasts per bone perimeter (N.Ob/B.Pm) and number of osteocytes per bone area (N.Ot/B.Ar) were evaluated via “osteomeasure.” Student’s t test was used for statistics where ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. e Representative µCT reconstruction pictures of the femur of conditional Rnf40Bglap-Cre male mice at 6 weeks of age. The bones were analyzed using a SkyScan 1176 microCT. f Bone histomorphometric parameters in conditional Rnf40Bglap-Cre mice showing trabecular bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th.), trabecular separation (Tb. Sp.), and trabecular number (Tb.N.) of femora of male mice used in the study were determined according to guidelines of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. g, h The relative expression of osteoblast marker genes from MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts was evaluated via qRT-PCR analysis and normalized to the expression levels of the Gapdh housekeeping gene in the control undifferentiated state. In g, cells were transfected with siRNAs and after 24 h differentiation was induced. In h, Rnf40 was depleted 4 days after differentiation was initiated and the cells were cultured another 3 days in differentiation media. Mean ± SD, n = 3, unless otherwise indicated in the figure. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test was performed for statistical analysis where ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

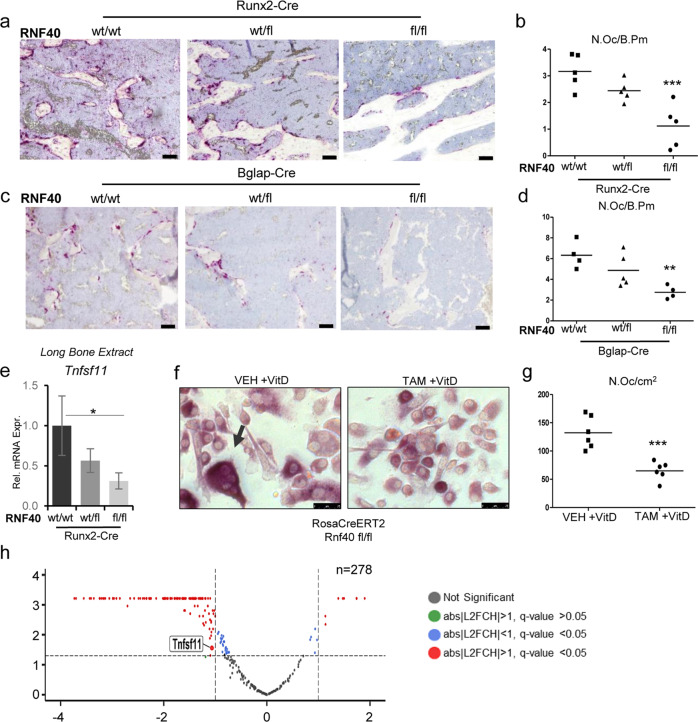

RNF40 controls bone mass via crosstalk between OBs and OCs

Since an increase in bone mass in Rnf40Runx2Cre and Rnf40BglapCre mice could not be explained by the observed reduction in OB function, we next examined bone resorption parameters in these mice. Interestingly, the number of OCs (N.Oc) as well as the OC surface were decreased in Rnf40Runx2Cre and Rnf40BglapCre mice (Fig. 4a–d, Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). Notably, a similar phenotype with increased bone mass and decreased bone resorption was previously reported in OB-specific Vdr knockout mice and has been attributed to reduced Tnfsf11 expression [43]. RANKL (encoded by Tnfsf11) is an important determinant of OC activation and differentiation [44]. We therefore assessed Tnfsf11 expression directly in the RNA extracts derived from the tibae of 6-week-old Rnf40Runx2Cre mice. Indeed, Tnfsf11 was found to be downregulated in the bones of conditional Rnf40 knockout mice (Fig. 4e). The active form of vitamin D (vitD), 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D] is an important inducer of RANKL expression and controls crosstalk between OB and OC [45]. We therefore tested whether vitD-induced OB and OC communication may be affected upon the RNF40 loss. Indeed, vitamin D-stimulated RNF40-deficient OBs displayed a strong attenuation of OC formation in coculture experiments (Fig. 4f, g). Vitamin D acts as a ligand for vitamin D receptor (VDR), a nuclear hormone receptor that forms heterodimers with retinoic X receptor to activate gene expression upon ligand binding. This complex binds to Vitamin D response elements in the genome to regulate target gene expression [46]. To understand the role of RNF40 in VDR signaling we performed transcriptome-wide analysis in calvarial Rnf40RosaCreERT2 OBs with subsequent induction of Rnf40 deletion by treatment with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Tam) followed by vitD treatment.

Fig. 4. RNF40 is a negative regulator of bone mass.

The plastic-embedded femoral sections from a Rnf40Runx2-Cre and c Rnf40Bglap-Cre were subjected to TRAP staining. Bar: 50 µm. b–d The number of osteoclasts was defined using “osteomeasure” software and depicted as number of osteoclasts per bone perimeter (N.Oc/B.PM) for each respective genotype. e The relative expression of Rankl (Tnfsf11) was evaluated in the tibae of Rnf40Runx2-Cre wild-type (wt/wt), heterozygous (wt/fl), and knockout (fl/fl) mice via qRT-PCR analysis and normalized to the expression level of the Gapdh housekeeping gene. Mean ± SD, n = 3. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test was performed for statistical analysis where ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. f, g Primary calvarial osteoblasts from Rnf40 mouse with an initial 7 day TAM or VEH treatment were cocultured with primary bone marrow-derived macrophages from wild-type mice for 9 days with the addition of 10 nM vitamin D treatment. TRAP staining was used to visualize the osteoclasts (f). Quantification of TRAP-positive multinucleated osteoclasts from the coculture experiment defined in g. h Primary calvarial osteoblasts from Rnf40Rosa-CreERT2 subjected to 7 days of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (TAM) or vehicle (VEH) treatment were subsequently treated with vitamin D (+vitD) or an equivalent volume of DMSO (−vitD) for an additional 7 days. RNA was harvested and subjected to sequencing. The volcano plot shows vitamin D-induced genes (n = 278, q value ≤ 0.05, log2 fold change (L2FC) ≥ 0.8) and their regulation by Rnf40 knockout. Red color indicates significantly up- or downregulated genes in the Rnf40 knockout with abs|L2FC| ≥ 1 and q value ≤ 0.05; the blue dots—significantly (q value ≤ 0.05) regulated genes with less than abs|L2FC| < 1; the green dots—insignificantly regulated genes with abs|L2FC| ≥ 1 and q value > 0.05; and the black dots—unregulated genes with q value > 0.05 and abs|L2FC| < 1.

Interestingly, most vitD-induced genes (Supplementary Table 1), including Tnfsf11, were downregulated following Rnf40 deletion (Supplementary Fig. 4c, d, Fig. 4h). These genes were mainly enriched in pathways associated with extracellular matrix (Table 2). This effect was not caused by Tam treatment itself, since no changes in Tnfsf11 expression were observed in WT Rnf40RosaCreERT2 cells (Supplementary Fig. 4e). Taken together, these data support the notion that RNF40 regulates transcription induced by stimuli such as vitD treatment. This leads to the disruption of RANKL-RANK signaling between the OBs and OCs and thereby to deregulated bone remodeling.

Table 2.

Gene ontology analysis (GO) for cellular component (CC) was performed on the subset of genes induced by vitD stimulation and downregulated upon Rnf40 knockout.

| GO Term | REFLIST | VitD_UP_RNF40_DN (139) | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular matrix (GO:0031012) | 475 | 18 | 3.38E−06 |

| Collagen-containing extracellular matrix (GO:0062023) | 359 | 14 | 8.72E−05 |

| Extracellular region (GO:0005576) | 2788 | 36 | 1.13E−02 |

| Extracellular region part (GO:0044421) | 2235 | 30 | 2.66E−02 |

RNF40-dependent genes employ enhancer-independent mechanisms of regulation

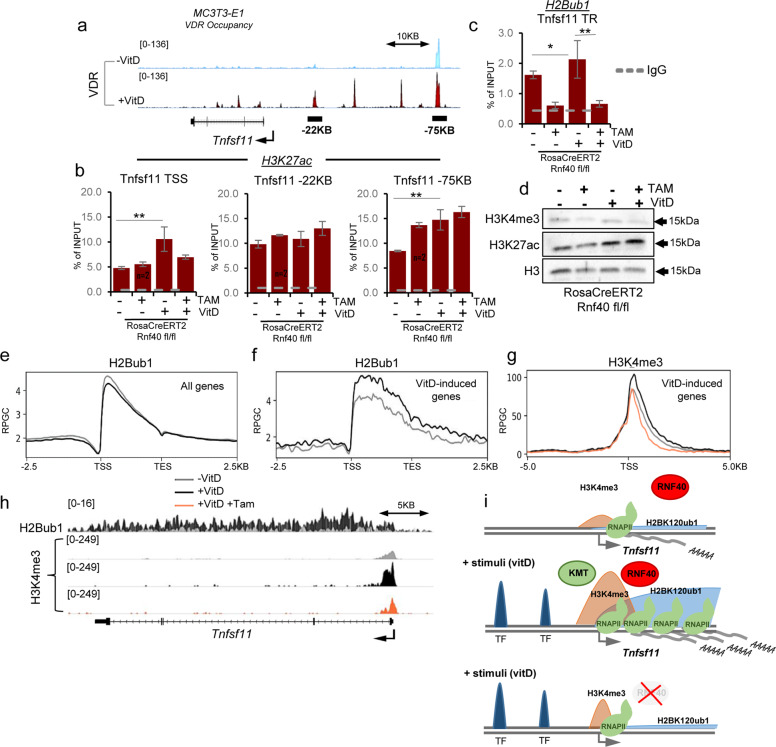

The Tnfsf11 gene encoding RANKL is a direct VDR target gene and already 24 h after vitD stimulation VDR binding can be observed at several promoter-proximal and distal regulatory sites (Fig. 5a) [47] that may act as enhancers in promoting Tnfsf11 expression. Active enhancers bound by activating TFs such as VDR can be distinguished by histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac) [48]. Indeed, vitamin D stimulation leads to a VDR-dependent increase in H3K27ac occupancy both at the TSS as well as at putative enhancers on the Tnfsf11 gene (Supplementary Fig. 5a) in primary calvarial OBs. Since the observed changes in Tnfsf11 expression mediated by RNF40 loss could be potentially attributed to changes in VDR-dependent enhancer activation, we similarly evaluated H3K27ac occupancy at the indicated sites on the Tnfsf11 gene upon deletion of Rnf40 in calvarial Rnf40RosaCreERT2 OBs. Interestingly, while changes in H3K27ac occupancy near the TSS correlated with changes in gene expression, H3K27ac occupancy was not decreased at putative VDR-driven distal enhancer regions (Fig. 5b), suggesting that RNF40 loss induced changes in Tnfsf11 expression are most likely not the result of deregulated enhancer activity. Consistent with a role in Tnfsf11 gene expression, H2Bub1 occupancy on the TR of the Tnfsf11 gene was increased following vitD treatment and decreased as a result of Rnf40 deletion (Fig. 5c). Neither vitamin D stimulation nor loss of VDR affected total H2Bub1 protein levels (Supplementary Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5. RNF40-dependent genes rely on H3K4me3 and employ enhancer-independent mechanisms of regulation.

a Normalized average occupancy (in reads per genome coverage, RPGC) of VDR across the Tnfsf11 gene in MC3T3-E1 cells following 24 h of vitamin D treatment. b H3K27ac (at TSS and potential enhancer sites) and c H2Bub1 (across transcribed region) occupancy was evaluated for the Tnfsf11 gene via ChIP-qPCR in primary calvarial osteoblasts from Rnf40Rosa-CreERT2 subjected to 7 days of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (TAM) or vehicle (VEH) treatment followed by 7 days of vitD or DMSO treatment. The ChIP efficiency is displayed as enrichment over input in percent. Mean ± SD, n = 3, unless otherwise indicated in the figure. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test were performed for statistical analysis where ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. d Western blot analysis of H3K4me3 and H3K27ac in whole-cell protein lysates from Rnf40Rosa-CreERT2 primary osteoblasts. H3 was used as a loading control. Average occupancy of H2Bub1 (e) on all genes or H2Bub1 and H3K4me3 (f, g) on all the vitamin D-induced genes in primary calvarial osteoblasts from Rnf40Rosa-CreERT2 mouse. h The normalized average occupancy (in reads per genome coverage, RPGC) of H2Bub1 and H3K4me3 across the Tnfsf11 gene. i The model explains the mechanism of RNF40-driven H2B monoubiquitination in the regulation of target gene expression. In the absence of the stimulus the gene is not expressed (upper panel). Upon stimulation (e.g., by vitamin D), the activated transcription factor (TF) drives expression of target genes (e.g., Tnfsf11) by recruiting the RNF20/40 complex, leading to monoubiquitination of histone H2B. This, in turn enables trimethylation of histone 3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me3) near the transcriptional start site and facilitating transcriptional elongation of the gene by RNA Polymerase II (RNAPII) (middle panel). In the absence of RNF40, loss of H3K4me3 at the promoter leads to a reduced RNAPII occupancy across the gene and hence decreased mRNA production (lower panel).

Given the crosstalk between H2Bub1 and other histone modifications [10–12] including H3K4me3, we also examined the global H3K4me3 and H3K27ac protein levels in calvarial Rnf40RosaCreERT2 OBs. While no effect was observed on total H3K27ac, H3K4me3 levels dropped slightly following Rnf40 deletion (Fig. 5d). Notably, vitD treatment did not appreciably affect H2Bub1 occupancy genome-wide (Fig. 5e), but did specifically stimulate an increase of H2Bub1 occupancy on the subset of vitD-induced genes (Fig. 5f). This was also correlated with an increase and broadening of H3K4me3 around the TSS of these genes (Fig. 5g, h). Consistently, H3K4me3 levels dropped on these genes in response to RNF40 loss (Fig. 5g, h). Taken together, these data suggest that the RNF40-dependent H2Bub1-H3K4me3 trans-histone pathway is crucial for stimulus-driven transcriptional regulation and contributes to bone remodeling by promoting Tnfsf11 expression.

Discussion

We previously identified a central role of RNF40 in OB differentiation of human mesenchymal stromal cells. By utilizing three independent OB-specific Cre-expressing mouse lines (Runx2-Cre, Bglap-Cre, and Dmp1-Cre), we now demonstrate a previously unknown stage-specific role of RNF40 in bone formation and remodeling.

Although the N.Obs was not altered in Rnf40Runx2Cre mice, Rnf40-deficient OBs displayed reduced mineral matrix production and reduced differentiation into osteocytes. Based on in vitro observations from Rnf40-deficient calvarial OBs, these cells demonstrate reduced ALP and osteocalcin expression, two factors characteristic for mature OBs and important for matrix maturation and mineralization. This suggests that Rnf40-deficient osteoprogenitor cells lack the ability to transition to the next stages of differentiation. However, the absence of changes in OB and osteocyte numbers and bone formation defects in Rnf40BglapCre and Rnf40Dmp1Cre mice demonstrate the dispensability of RNF40-driven H2B monoubiquitination for the maintenance and differentiation of mature OBs. Interestingly, this might be different for RNF20, since its depletion in vitro also affected later stages of OB differentiation. Thus, RNF20 may have H2Bub1- and RNF40-independent roles in maintaining OB-specific gene expression. However, additional genetic studies will be necessary to address this possibility.

Recent data indicate both tumor-suppressor as well as tumor-promoting functions of H2Bub1 [14, 20, 22, 49–51]. However, in this study, the N.Obs was not altered in conditional Rnf40 KO mice excluding the possible regulation of differentiation by RNF40-mediated H2B monoubiquitination through changes in proliferation and cell cycle. Consistent with this finding, we also recently reported a critical role for RNF40 in controlling Schwann cell differentiation by interaction with the lineage-defining TF EGR2 [18]. Together, these observations confirm that H2Bub1-mediated transcriptional regulation is context dependent.

In addition to its role in differentiation, we also identified a previously unreported role of RNF40 in regulating Tnfsf11 expression by the VDR. As a result, both the Rnf40Runx2Cre and Rnf40BglapCre mice demonstrated reduced bone resorption parameters. Notably, the regulation of Tnfsf11 by RNF40-mediated H2B monoubiquitination appears to be restricted to OBs and not the osteocytes, since Rnf40Dmp1Cre mice did not display any defects in bone mass. Consistently, it was previously shown that osteocyte-specific ablation of Vdr using the same Dmp1-Cre mouse model also had no effect on bone remodeling suggesting VDR-mediated activation of Tnfsf11 expression is dispensable in osteocytes [52]. Our findings also indicate that RNF40-mediated H2B monoubiquitination is required for the OB-specific VDR signaling.

The role of H2Bub1 in transcriptional regulation has been attributed largely to its function in assisting the RNAPII-mediated transcriptional elongation on selected subsets of genes [6–8]. Consistently, the loss of H2Bub1 on differentiation- or vitD-induced genes following Rnf40 deletion correlates well with a decrease and narrowing of H3K4me3. As we previously reported, the spreading of H3K4me3 into the gene body is closely coupled to rate of transcriptional elongation of the genes, and is highly dependent on RNF40 and H2Bub1 [15]. Moreover, our data also indicate that RNF40-regulated genes are, in general, lowly marked by H2Bub1 compared to other active genes. This finding is consistent with our previous data demonstrating that lowly H2Bub1-marked genes are more sensitive to changes in the amount of histone modifications facilitated by tissue-specific TFs [15].

This supports the notion that H2Bub1 specifically regulates inducible rather than constitutive transcription. In line with previous reports, our results similarly indicate that RNF40-target genes rely mainly on H3K4me3-dependent transcriptional regulation. The role of H2Bub1 in regulating stimulus-induced gene expression can be explained by in the model shown in Fig. 5i. According to our model, in an unstimulated condition (without differentiation factors or vitD treatment), RNF40-target genes such as Tnfsf11 are not expressed or display very low expression levels. Upon stimulation, sequence-specific TFs are recruited to tissue-specific enhancers. These TFs enable recruitment of RNF20/40 to the target gene, thereby increasing H2Bub1 across the gene body. This newly deposited H2Bub1 in turn facilitates the trimethylation of H3K4 near the TSS and enables its spreading into the gene body by lysine methyltransferases of the Trithorax family [5, 53]. This is associated with a higher transcriptional elongation rate of the gene and an increase in mRNA production. Consistently, in the absence of RNF40, the lack of H2Bub1 and the subsequent reduction and narrowing of H3K4me3 occupancy decreases the transcriptional elongation of the gene without affecting the epigenetic marking of enhancer regions.

In summary, in this report, we show a role of RNF40-driven H2B monoubiquitination [5] in OBs important for bone integrity. We provide evidence that H2Bub1 is required at early stages of OB function and also controls bone cell crosstalk by regulating VDR-induced Tnfsf11 expression. Based on this, inhibition of H2Bub1 signaling could serve as a potential strategy for therapy of pathological conditions associated with bone loss. However, inhibitors directly targeting the RNF20 and RNF40 protein complex do not yet exist. Given the crosstalk between H2B monoubiquitination and H3K4 and H3K79 methylation [10–12], the use of inhibitors of the specific methyltransferases catalyzing these reactions or inhibition of upstream pathways such as CDK9 [4, 54] could potentially elicit similar effects as RNF40 loss. However, additional studies will be essential to test this approach.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figures 1–5, legends and overview of all supplementary information as PDF

Acknowledgements

The authors thank H. Saito, H. Taipaleenmäki, and K. Jähn for invaluable assistance and support at initial steps of mouse experiments. Moreover, we are grateful to T. Bellido for providing us with Tg(Dmp1-cre)1Btm mice. We are thankful also to N. Molitor for mouse genotyping and S. Baumgart for assistance with mouse experiments. We wish to acknowledge the NGS Integrative Genomics Core Unit at the University Medical Center Göttingen for performing the sequencing. This work was funded by the Dorothea Schlözer program at the University of Göttingen (to ZN); the German Ministry for Science and Education (BMBF) and Agence Nationale de la Recherche-funded iBONE consortium [01KU1401A] (to SAJ); and the German Research Foundation (DFG) [JO 815/3-1] (to SAJ), [TU220/14-1], Danger Response, Disturbance Factors and Regenerative Potential after Acute Trauma [CRC1149 C02 INST 492-2] (to JT).

Author contributions

The experiments were designed by SAJ, JT, PL, and ZN. ZN performed all the in vitro experiments, sequencing data analyses, and harvested the bones and primary cell cultures from the mice. RLK performed primary cultures and helped with harvesting of bones. PL performed all the bone histomorphometric and µCT analyses, as well as the coculture experiment. FW participated in the generation and maintenance of the mouse lines, and harvesting of the bones and primary cell cultures from the mice. MA performed the 3D reconstruction of the mouse bones. LT assisted with the in vitro experiments. WX assisted with mouse experiments and data analyses. ZN, SAJ, and JT wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

All the generated and analyzed data supporting the findings of this study are available in this article and its Supplementary Information file. The data can also be obtained from the authors. Sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI GEO repository. The accession numbers can be found in Supplementary Table 5.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by V D'Angiolella

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Zeynab Najafova, Peng Liu

Contributor Information

Steven A. Johnsen, Email: johnsen.steven@mayo.edu

Jan Tuckermann, Email: jan.tuckermann@uni-ulm.de.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41418-020-00614-w) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Sims NA, Martin TJ. Coupling the activities of bone formation and resorption: a multitude of signals within the basic multicellular unit. Bonekey Rep. 2014;3:481. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2013.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berendsen AD, Olsen BR. Bone development. Bone. 2015;80:14–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Crombrugghe B, Lefebvre V, Nakashima K. Regulatory mechanisms in the pathways of cartilage and bone formation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:721–8. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(00)00276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karpiuk O, Najafova Z, Kramer F, Hennion M, Galonska C, König A, et al. The histone H2B monoubiquitination regulatory pathway is required for differentiation of multipotent stem cells. Mol Cell. 2012;46:705–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu B, Zheng Y, Pham A-D, Mandal SS, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, et al. Monoubiquitination of human histone H2B: the factors involved and their roles in HOX gene regulation. Mol Cell. 2005;20:601–11. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minsky N, Shema E, Field Y, Schuster M, Segal E, Oren M. Monoubiquitinated H2B is associated with the transcribed region of highly expressed genes in human cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:483–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pavri R, Zhu B, Li G, Trojer P, Mandal S, Shilatifard A, et al. Histone H2B monoubiquitination functions cooperatively with FACT to regulate elongation by RNA polymerase II. Cell. 2006;125:703–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleming AB, Kao C-F, Hillyer C, Pikaart M, Osley MA. H2B ubiquitylation plays a role in nucleosome dynamics during transcription elongation. Mol Cell. 2008;31:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuchs G, Hollander D, Voichek Y, Ast G, Oren M. Cotranscriptional histone H2B monoubiquitylation is tightly coupled with RNA polymerase II elongation rate. Genome Res. 2014;24:1572–83. doi: 10.1101/gr.176487.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim J, Guermah M, McGinty RK, Lee J-S, Tang Z, Milne TA, et al. RAD6-mediated transcription coupled H2B ubiquitylation directly stimulates H3K4 methylation in human cells. Cell. 2009;137:459–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee J-S, Shukla A, Schneider J, Swanson SK, Washburn MP, Florens L, et al. Histone crosstalk between H2B monoubiquitination and H3 methylation mediated by COMPASS. Cell. 2007;131:1084–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakanishi S, Lee JS, Gardner KE, Gardner JM, Takahashi Y, Chandrasekharan MB, et al. Histone H2BK123 monoubiquitination is the critical determinant for H3K4 and H3K79 trimethylation by COMPASS and Dot1. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:371–7. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200906005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie W, Miehe M, Laufer S, Johnsen SA. The H2B ubiquitin-protein ligase RNF40 is required for somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2182-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shema E, Tirosh I, Aylon Y, Huang J, Ye C, Moskovits N, et al. The histone H2B-specific ubiquitin ligase RNF20/hBRE1 acts as a putative tumor suppressor through selective regulation of gene expression. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2664–76. doi: 10.1101/gad.1703008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie W, Nagarajan S, Baumgart SJ, Kosinsky RL, Najafova Z, Kari V, et al. RNF40 regulates gene expression in an epigenetic context-dependent manner. Genome Biol. 2017;18:32. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1159-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuchs G, Shema E, Vesterman R, Kotler E, Wolchinsky Z, Wilder S, et al. RNF20 and USP44 regulate stem cell differentiation by modulating H2B monoubiquitylation. Mol Cell. 2012;46:662–73. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang Q, Xia W, Li W, Jiao J. RNF20 controls astrocytic differentiation through epigenetic regulation of STAT3 in the developing brain. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:294–306. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wüst HM, Wegener A, Fröb F, Hartwig AC, Wegwitz F, Kari V, et al. Egr2-guided histone H2B monoubiquitination is required for peripheral nervous system myelination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020. 10.1093/nar/gkaa606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Bedi U, Scheel AH, Hennion M, Begus-Nahrmann Y, Rüschoff J, Johnsen SA. SUPT6H controls estrogen receptor activity and cellular differentiation by multiple epigenomic mechanisms. Oncogene. 2015;34:465–73. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prenzel T, Begus-Nahrmann Y, Kramer F, Hennion M, Hsu C, Gorsler T, et al. Estrogen-dependent gene transcription in human breast cancer cells relies upon proteasome-dependent monoubiquitination of histone H2B. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5739–53. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jääskeläinen T, Makkonen H, Visakorpi T, Kim J, Roeder RG, Palvimo JJ. Histone H2B ubiquitin ligases RNF20 and RNF40 in androgen signaling and prostate cancer cell growth. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;350:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosinsky RL, Chua RL, Qui M, Saul D, Mehlich D, Ströbel P, et al. Loss of RNF40 decreases NF-κB activity in colorectal cancer cells and reduces colitis burden in mice. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:362–73. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ventura A, Kirsch DG, McLaughlin ME, Tuveson DA, Grimm J, Lintault L, et al. Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature. 2007;445:661–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu Y, Xie Y, Zhang S, Dusevich V, Bonewald LF, Feng JQ. DMP1-targeted Cre expression in odontoblasts and osteocytes. J Dent Res. 2007;86:320–5. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang M, Xuan S, Bouxsein ML, Stechow Dvon, Akeno N, Faugere MC, et al. Osteoblast-specific knockout of the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor gene reveals an essential role of IGF signaling in bone matrix mineralization. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44005–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rauch A, Seitz S, Baschant U, Schilling AF, Illing A, Stride B, et al. Glucocorticoids suppress bone formation by attenuating osteoblast differentiation via the monomeric glucocorticoid receptor. Cell Metab. 2010;11:517–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sitara D, Kim S, Razzaque MS, Bergwitz C, Taguchi T, Schüler C, et al. Genetic evidence of serum phosphate-independent functions of FGF-23 on bone. PLOS Genet. 2008;4:e1000154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Najafova Z, Tirado-Magallanes R, Subramaniam M, Hossan T, Schmidt G, Nagarajan S, et al. BRD4 localization to lineage-specific enhancers is associated with a distinct transcription factor repertoire. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:127–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu P, Lee S, Knoll J, Rauch A, Ostermay S, Luther J, et al. Loss of menin in osteoblast lineage affects osteocyte–osteoclast crosstalk causing osteoporosis. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:672–82. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The Sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramírez F, Dündar F, Diehl S, Grüning BA, Manke T. deepTools: a flexible platform for exploring deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W187–91. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts A, Pimentel H, Trapnell C, Pachter L. Identification of novel transcripts in annotated genomes using RNA-seq. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2325–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts A, Trapnell C, Donaghey J, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Improving RNA-seq expression estimates by correcting for fragment bias. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R22. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-3-r22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–9. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blighe K. EnhancedVolcano: publication-ready volcano plots with enhanced colouring and labeling. kevinblighe. Kevinblighe; 2019. https://github.com/kevinblighe/EnhancedVolcano.

- 39.Franceschi RT, Ge C. Control of the osteoblast lineage by mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. Curr Mol Biol Rep. 2017;3:122–32. doi: 10.1007/s40610-017-0059-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsushita T, Chan YY, Kawanami A, Balmes G, Landreth GE, Murakami S. Extracellular signal regulated kinase 1 (ERK1) and ERK2 play essential roles in osteoblast differentiation and in supporting osteoclastogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5843–57. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01549-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ducy P, Zhang R, Geoffroy V, Ridall AL, Karsenty G. Osf2/Cbfa1: a transcriptional activator of osteoblast differentiation. Cell. 1997;89:747–54. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Komori T, Yagi H, Nomura S, Yamaguchi A, Sasaki K, Deguchi K, et al. Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell. 1997;89:755–64. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamamoto Y, Yoshizawa T, Fukuda T, Shirode-Fukuda Y, Yu T, Sekine K, et al. Vitamin D receptor in osteoblasts is a negative regulator of bone mass control. Endocrinology. 2013;154:1008–20. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boyce BF, Xing L. Biology of RANK, RANKL, and osteoprotegerin. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:S1. doi: 10.1186/ar2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim S, Yamazaki M, Zella LA, Shevde NK, Pike JW. Activation of receptor activator of NF-κB ligand gene expression by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is mediated through multiple long-range enhancers. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6469–86. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00353-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kimmel-Jehan C, Jehan F, DeLuca HF. Salt concentration determines 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 dependency of vitamin D receptor–retinoid X receptor–vitamin D-responsive element complex formation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;341:75–80. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.9952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meyer MB, Benkusky NA, Lee C-H, Pike JW. Genomic determinants of gene regulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 during osteoblast-lineage cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:19539–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.578104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Creyghton MP, Cheng AW, Welstead GG, Kooistra T, Carey BW, Steine EJ, et al. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. PNAS. 2010;107:21931–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016071107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schneider D, Chua RL, Molitor N, Hamdan FH, Rettenmeier EM, Prokakis E, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF40 suppresses apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Clin Epigenetics. 2019;11:98. doi: 10.1186/s13148-019-0698-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sethi G, Shanmugam MK, Arfuso F, Kumar AP. Role of RNF20 in cancer development and progression—a comprehensive review. Biosci Rep. 2018;38:BSR20171287. doi: 10.1042/BSR20171287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tarcic O, Granit RZ, Pateras IS, Masury H, Maly B, Zwang Y, et al. RNF20 and histone H2B ubiquitylation exert opposing effects in basal-like versus luminal breast cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:694–704. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lieben L, Masuyama R, Torrekens S, Looveren RV, Schrooten J, Baatsen P, et al. Normocalcemia is maintained in mice under conditions of calcium malabsorption by vitamin D–induced inhibition of bone mineralization. J Clin Investig. 2012;122:1803–15. doi: 10.1172/JCI45890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hallson G, Hollebakken RE, Li T, Syrzycka M, Kim I, Cotsworth S, et al. dSet1 is the main H3K4 di- and tri-methyltransferase throughout drosophila development. Genetics. 2012;190:91–100. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.135863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pirngruber J, Shchebet A, Schreiber L, Shema E, Minsky N, Chapman RD, et al. CDK9 directs H2B monoubiquitination and controls replication-dependent histone mRNA 3′-end processing. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:894–900. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1–5, legends and overview of all supplementary information as PDF

Data Availability Statement

All the generated and analyzed data supporting the findings of this study are available in this article and its Supplementary Information file. The data can also be obtained from the authors. Sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI GEO repository. The accession numbers can be found in Supplementary Table 5.