Abstract

Introduction:

The purpose of the present study was to compare the immunomodulatory effect of azithromycin (AZM), ampicillin (AMP), amoxicillin (AMX) and clindamycin (CLI) “in vitro” and AZM on pre-existing periapical lesions when compared to ampicillin (AMP).

Methods:

Susceptibility of four common human endodontic pathogens (Parvimonas micra, Streptococcus intermedius, Prevotella intermedia, and Fusobacterium nucleatum) to AZM, AMP, AMX, and CLI was confirmed by agar disc diffusion assay. Pre-existing periapical lesions in C57BL/6J mice were treated with AZM, AMP, or PBS (phosphate buffered saline). Periapical bone healing and pattern of inflammatory cell infiltration were evaluated after a 10-day treatment by micro computed tomography and histology, respectively. Besides, the effect of antibiotics in pathogen-stimulated NF-κB activation and production of IL-1α and TNF-α was assessed in vitro by luciferase assay and ELISA.

Results:

All examined endodontic pathogens were susceptible to AZM, AMP, AMX, and CLI. AZM significantly attenuated periapical bone loss vs. PBS. PBS resulted in widely diffused infiltration of mixed inflammatory cells. By contrast, AZM brought about localized infiltration of neutrophils and M2 macrophages and advanced fibrosis. Although the effect of AMP on bone was uncertain, inflammatory cell infiltration was considerably milder than PBS. However, most macrophages observed seemed to be M1 macrophages. AZM suppressed pathogen-stimulated NF-κB activation and cytokine production, whereas AMP, AMX, and CLI reduced only cytokine production moderately.

Conclusions:

This study showed that AZM led to the resolution of pre-existing experimental periapical inflammation. Our data provide a perspective on host response in antibiotic selection for endodontic treatment. However, well-designed clinical trials are necessary to better elucidate the benefits of AZM as an adjunctive therapy for endodontic treatment when antibiotic therapy is recommended. Although both AZM and AMP were effective on pre-existing periapical lesions, AZM led to advanced wound healing probably depending on its immunomodulatory effect.

Keywords: Periapical periodontitis, azithromycin, ampicillin, immunomodulation, endodontic infection

Introduction

Periapical periodontitis (PP) is a chronic inflammatory disease as a consequence of endodontic infection and its development is regulated by the host immune/inflammatory response. The outcome of this inflammatory process is destruction of periapical tissue and alveolar bone and incomplete wound healing (1, 2). The cellular and molecular players in the development of periapical lesions have been well investigated (1, 3, 4). In particular, macrophage is the key innate immune cell type in the development of periapical lesions (5). Classically activated M1 macrophages produce pro-inflammatory and bone destructive mediators such as interleukin-1 alpha (IL-1α) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α). At the same time, alternatively activated M2 macrophages secret anti-inflammatory mediators (e.g. IL-10 and arginase 1), regulating the level of chronic inflammation (6). Imbalance of M1 and M2 macrophages is associated with chronic inflammation and infections (6); therefore, macrophages and macrophage-derived cytokines are possible targets for the immnunomodulation and improvement of periapical wound healing. However, the effect of modulation of macrophage activation during endodontic treatment has not been examined.

As periapical lesions are caused by infection, the lesions will not heal without antimicrobial approaches. To achieve both reduction of bacteria and immunomodulation in an experimental setting, we focused on macrolide antibiotics, which have a long history as immunomodulatory antibiotics (7, 8). Azithromycin (AZM) is a second generation of macrolides and shifts macrophage activation towards M2 phenotype (9). In the present study, we compared the effect of immunomodulatory AZM on pre-existing periapical lesions with ampicillin (AMP) in a mouse periapical lesion model.

Methods

Agar disc diffusion antibiotic sensitivity test

Human common endodontic pathogens Parvimonas micra (ATCC 33270), Streptococcus intermedius (ATCC 27335), Prevotella intermedia (ATCC25611), and Fusobacterium nucleatum (ATCC 25586) were uniformly swabbed on Tryptic Soy Agar with 5% sheep blood plates (R02049, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in a standardized manner. Then, AZM (15 μg), AMP (10 μg), Amoxicillin (AMX) (30 μg), and Clindamycin (CLI) (2 μg) impregnated paper disks (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA) were placed at the center of the plate. The diameter of the zone of inhibition was measured in millimeters after a 24-hour anaerobic incubation at 37° C.

Induction of periapical lesions and antibiotics treatment in vivo

The procedures of the animal experiment were approved by The Forsyth Institute Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Age-matched C57BL/6J mice (6 weeks of age; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were subjected to dental pulp exposure followed by pulpal infection with a cocktail of four common human endodontic pathogens as previously described (3) and observed for 10 days to establish periapical lesions. Subsequently, the mice received any of the following: AZM (0.2 mg in 0.2 mL PBS/mouse/injection in initial two days, then half dose thereafter; once daily), AMP (0.2 mg in 0.2 mL PBS /mouse/injection; twice daily at 12-hour intervals), or PBS (0.2 mL; once a day) from day 10 to day 20. The treated mice were killed on day 21, and untreated mice were sacrificed on day 10 as the disease baseline. The sample size was six per group.

Micro-computed tomography imaging (μCT), histology and immunohistochemistry

The extent of periapical bone loss was determined by micro computed tomography (μCT) scan (μCT40, Scanco Medical AG, Bassersdorf, Switzerland). The area of the bone loss around the distal root was defined using a standardized template and measured using Adobe Photoshop CS6 (Adobe) and ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD) as described (10). The results were expressed in square millimeters (mm2). The same samples were subsequently subjected to histology. H&E staining was used for initial histological observation. Inflammation was further analyzed by immunohistochemistry using four antibodies in serial sections: 1) anti-mouse Mac2 antibody (total macrophage; 1:500 dilution; BioLegend); 2) anti-mouse Ly6G antibody (neutrophil; 1:1000 dilution; BioLegend); 3) anti-mouse iNOS antibody (a proinflammatory enzyme/an M1 macrophage marker; 1:500 dilution, Abcam), 4) anti-mouse Arg-1 antibody (a pro-resolving enzyme/an M2 macrophage marker; 1:500 dilution, Abcam). Antigen-antibody complexes were evidenced by the avidin-biotin peroxidase (ABC) method using the commercially available DAB Peroxidase (HRP) Substrate Kit (DAKO). Finally, the sections were counter-stained with hematoxylin. The specificity of immune reactions was tested by omission of primary antibodies. Cell distribution analyses were carried out under light microscopy either at x100, x200, or x400 magnification. Distribution of IHC-positively stained (IHC+) cells in each sample was determined by image processing using Adobe Photoshop CS6. In brief, IHC+ cells in each captured image was selected by a specified color range, and the selection was replaced with a target-specific color (blue:LY-6G; yellow: iNOS; green: Arg-1). Then, the selection was layered on the base image (H-E staining) considering the position change in serial sections. The transparency of each layer was adjusted to keep the visibility of all layers.

NF-κB reporter assay and ELISA

The effect of AZM, AMP, AMX, and CLI on macrophage inflammation was determined using nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) Luciferase Stable RAW264.7 cells (NF-κB RAW; Applied Biological Materials Inc., BC, Canada) in vitro. The cells (1.5×105 cells/well in 48-well format) were stimulated with either Escherichia coli LPS (serotype 0111:B4, 0.1 μg/mL, 100 μl/well; Sigma-Aldrich) or a cocktail of the fixed four endodontic pathogens above (0.25×107/specie/ml, 100 μl/well) in the presence or absence of AZM, AMP, AMX, and CLI (3, 6, and 12 μM). Complete medium alone (α-MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum) and PBS served as non-stimulated control and non-treated control, respectively. The level NF-κB activation was determined at 6-hr post-stimulation by luciferase assay (Luciferase Assay System, Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, Interleukin-1α (IL-1α) and Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) was quantified by ELISA (DuoSets, R&D Systems) after a 24-hr stimulation (11).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis and data tabulations were performed using one-way or two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett post hoc test. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to compare the effect of one factor between two groups. P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Endodontic pathogens were susceptible to ampicillin and azithromycin

Four common human endodontic pathogens, P. intermedia, F. nucleatum, S. intermedius, and P. micra, were subjected to antibiotic susceptibility testing using the agar disc diffusion method of which the results are presented in Table 1. All pathogens were susceptible to AZM, AMP, AMX, and CLI and no resistant colonies were found within the inhibition zones around the antibiotic discs. AMP promoted a larger inhibition zone for all pathogens compared to AZM (P < .05), suggesting that AMP has a more efficient antibiotic activity compared to AZM in this condition.

Table 1.

The effectiveness of azithromycin and ampicillin on common human endodontic pathogens.

| Antibiotics | Negative control | Endodontic pathogens |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. intermedia | F. nucleatum | S. intermedius | P. micra | ||

| Azithromycin | 0 | 33.3 ± 0.6 | 24.3 ± 0.6 | 40.0 ± 0.0 | 25.3 ± 0.6 |

| Ampicillin | 0 | 52.3 ± 0.6* | 34.0 ± 1.0* | 54.7 ± 0.6* | 36.7 ± 1.2* |

| Amoxicillin | 0 | 65 ± 0* | 55.5 ± 0.7* | 40.5 ± 2.1 | 58.5 ± 0.7* |

| Clindamycin | 0 | 55 ± 1.4* | 46.5 ± 0.7* | 22 ± 0* | 42 ± 0* |

The effectiveness was assessed by agar disc diffusion method in triplicates. Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (mm). All endodontic pathogens were sensitive to azithromycin, ampicillin, amoxicillin, and clindamycin.

P < .05 vs. azithromycin.

AZM but not AMP reduced the size of periapical bone loss

The effect of antibiotics treatment on pre-existing periapical lesions was determined after an 11-day treatment with either AZM, AMP, or PBS using μCT. As shown in Figure 1, a measurable bone loss was developed on day 10 post pulpal infection, and the average lesion size of this group was set as the disease baseline. Compared to the baseline, lesion size in PBS-treated mice was slightly increased on day 21, but not statistically significant. AZM treatment resulted in significantly attenuated periapical lesion size vs. the baseline (62% vs. baseline; P < .05). In addition, the type of antibiotic was significantly affecting the lesion size; the lesion size in AZM-treated mice was 22% smaller than that in AMP-treated mice (P < .05). The effect of AMP treatment was redundant on the extent of periapical lesions.

Figure 1. Azithromycin attenuated pre-existing periapical bone loss.

(A) Representative μCT images of periapical periodontitis in the anterior-posterior direction. Pre-existing periapical lesions (PP baseline; day 10 post infection) were treated with either phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), azithromycin (AZM), or ampicillin (AMP) from day 10 to 20. The effect of the treatments was determined on day 21. The position of each CT slice was the most central part of the mandibular first molar distal root (R). Arrows indicate the margin of the periapical lesion surrounded by radiopaque alveolar bone. (B) Enumeration of periapical lesion size. * p < .05 vs. PP+PBS, vertical bar: standard deviation.

AZM-treated mice exhibited advanced healing of periapical inflammation

On day 10 post infection, moderate periapical inflammation (Fig. 2A1) chiefly consisting of Ly6G+ neutrophils and Mac2+ macrophages (Fig. 2B1 and 2C1) occurred. Cells expressing iNOS, a pro-inflammatory marker, overlap with both Ly6G+ neutrophils and Mac2+ macrophages (Fig 2B1, C1, and D1). In contrast, cells expressing Arg-1, a pro-resolving/anti-inflammatory marker, seemed to predominantly be macrophages (Fig 2C1 and 2E1). In the infiltrated cell profile on day 10 (Fig. 2F1), pro-inflammatory cells were histologically intermingled with anti-inflammatory infiltrates. On day 21, PBS-treated mice presented sustained moderate inflammation. Notably, the population of Arg-1+ cells was declined; iNOS+ cells predominated the infiltrates, indicating a dominant pro-inflammatory condition (Fig. 2A2, 2B2, 2C2, 2D2, 2E2, 2F2). Compared to the PBS group, AZM led to maturation of granulation tissue, including fibroblasts and dense collagen fibers, with mild inflammation (Fig. 2A3). Localized infiltration of neutrophils was observed around the apical foramen (Fig. 2B3). Mac2+ macrophages were observed in the lesions (Fig. 2C3), the majority of clustered Mac2+ cells was Arg-1+ cells (Fig. 2E3, 2F3). In contrast, AMP-treated mice exhibited periapical lesions consisting of somewhat less fibrous granulation tissue (Fig. 2A4). Arg-1+ macrophages accumulated in diffused neutrophils in AMP-treated lesions (Fig. 2B4, 2C4, 2E4, 2F4). A very mild expression of iNOS was co-localized with diffused neutrophils (Fig. 2F4). Histologically, AMP led to Arg-1+ M2 macrophage polarization in the infiltrates. However, the process of periapical wound healing was slightly slower than the AZM group (Fig. 2F3 and 4).

Figure 2. Histological summary of the representative sample in each group. AZM treatment resulted in advanced periapical wound healing.

(A1-A4) H&E staining. Both AZM and AMP considerably resolved inflammation. AZM resulted in advanced periapical wound healing (mature granulation tissue) compared to AMP. (B1-B4) Neutrophils (Ly-6G). (C1-C4) Total macrophages (Mac2). (D1-D4) Proinflammatory iNOS+ cells including M1 macrophages. (E1-E4) Arg-1+ M2 macrophages. (F1-F4). Distribution of infiltrated inflammatory cells by image processing. Population and diffusion pattern of infiltrated cells were different between AZM and AMP. AZM led to localized M2 macrophage polarization, whereas diffused proinflammatory cells were observed in AMP treated mice. These histological findings were similar among samples in each group. Blue: Ly-6G+, yellow: iNOS+, green: Arg-1+. Arrows indicate the circumference of periapical periodontitis. B, alveolar bone; R, dental root. The original magnification: x100.

AZM suppressed NF-κB activation and subsequent inflammatory response.

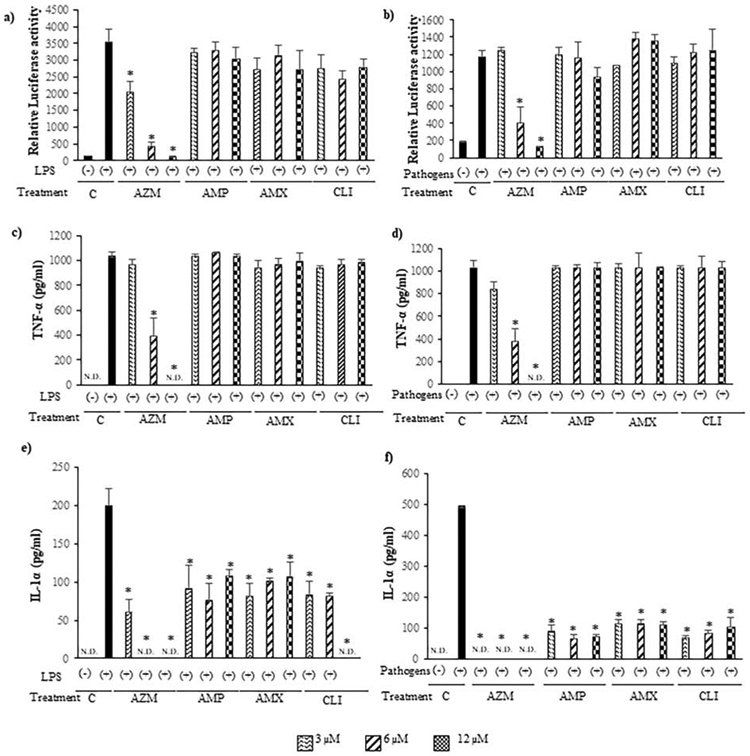

To identify the possible mechanism of the differences in periapical wound healing as well as the immunomodulatory activity of antibiotics prescribed in endodontics, we examined the effect of AZM, AMP, AMX, and CLI on inflammatory response in vitro (Fig. 3). Apart from the antibiotic effect, AZM significantly inhibited LPS and fixed endodontic pathogens-stimulated NF-κB activation in a dose-dependent manner in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 3a, b). In contrast, AMP, AMX, and CLI did not modulate the level of NF-κB activation, suggesting that AMP, AMX, and CLI do not affect NF-κB activation at the transcription level. Subsequent production of TNF-α, which is in general induced by NF-κB activation, was also inhibited in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 3c, d). Moreover, IL-1α production was almost completely inhibited by AZM (Fig. 3e, f). Although AMP, AMX, and CLI did not change the level of TNF-α, interestingly, production of IL-1α was significantly declined compared to LPS and endodontic pathogens controls (Fig. 3e, f), suggesting that AMP, AMX, and CLI are capable of modulating the inflammatory processes after NF-κB activation.

Figure 3. Azithromycin exhibited a potent immunomodulatory effect compared to ampicillin in RAW264.7 cells stimulated with LPS or endodontic pathogens in vitro.

AZM inhibited LPS-stimulated NF-κB activation in a dose-dependent manner (a) and subsequent production of TNF-α (c) and IL-1α (e). As well, AZM inhibited endodontic pathogen-stimulated NF-κB activation in a dose-dependent manner (b) and subsequent production of TNF-α (d) and IL-1α f). AMP, AMX and CLI also suppressed IL-1α. These data support previous findings in other infectious diseases that AZM can down-regulate inflammation, probably its chemical structure-dependent, in addition to its antibiotic effect. * P < .05 vs. corresponding non-treated controls, N.D.: not detected; vertical bar: standard deviation; n=3 per condition.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the effect of AZM and AMP on pre-existing experimental periapical lesions. We have intraperitoneally injected these antibiotics to avoid direct gut dysbiosis and following immune dysregulation (12). Although amoxicillin (AMX) is the first choice for the treatment of endodontic infection according to American Association of Endodontists (AAE), AMX is an oral route antibiotic based on its well-absorption from the intestine. Thus, we used AMP, whose chemical structure and antibiotic spectrum are similar to AMX, as an alternative for injection. In addition, we used CLI, which is used in patients with penicillin allergy for many years, in vitro. Although all endodontic pathogens were sensitive to AZM, AMP, AMX, and CLI, AZM presented higher immunomodulatory effect in RAW264.7 cells compared to the other antibiotics tested. Our in vivo data suggest that both AZM and AMP effectively attenuated infection-induced periapical inflammations. In particular, AZM led to reduced periapical lesion size and mature granulation tissue compared to AMP.

We consider the unique pharmacokinetics and immune modulatory property of AZM as possible mechanisms for the advanced healing in the AZM group. AZM was shown to be up taken and concentrated in myeloid cells (macrophages and neutrophils) and to achieve high and sustained tissue/plasma ratios in various tissues (>100-fold higher than plasma) (13-16). In contrast, the tissue/plasma ratio of AMP is 5.7 times that of plasma in a wound tissue (17). Myeloid cells are the key infiltrates in the development of periapical lesions as the sources of pro-inflammatory and bone destructive mediators. Thus, AZM might be effectively concentrated in periapical lesions accompanied by inflammatory cell infiltration.

Regarding antibiotics-mediated immune modulation, previous studies have shown that macrolides are attributed to the modulation of the host immune and inflammatory response, preventing the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines (such as Interleukin-1, Interleukin-8, and TNF-α), neutrophil accumulation, and superoxide anion production by neutrophils (7,8,16,18). In addition, AZM modulates macrophage activation from pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages to pro-resolving M2 macrophages, promoting efferocytosis (clearance of infiltrated cells) and subsequent wound healing (19-22). Interestingly, a non-antibiotic analog of AZM (CSY0073) leads to M2 macrophage activation in both infectious and sterile inflammations (23,24) and can attenuate immune dysfunction in lung inflammation, inflammatory bowel diseases, spinal cord injury, and bone destructive arthritis (24,25). These findings indicate that the immune modulation by AZM largely depends on its structure. AZM led to a potent accumulation of M2 macrophages, and the area of pro-inflammatory cells were mostly surrounded by M2 cells (Fig. 2F3) unlike AMP (Fig. 2F4). In addition, clusters of M2 macrophages appeared to contain the lesion (Fig. 2F3). AZM may be a useful option for immune modulation targeting the resolution and pro-healing of chronic inflammation besides the antibiotic effect.

On the other hand, we observed that AMP notably resolved periapical inflammation. In the AMP-treated lesions, we could histologically observe a clear M2 macrophage polarization and reduced neutrophils, suggesting infection-induced periapical inflammation was most probably at the resolution phase. This outcome seemed to be dependent on the antibiotic effect of AMP (Figure 2) and an unexpected suppression of pro-inflammamtory cytokines IL-1α at the level of post NF-κB activation (Figure 3c, e, f). Although not as high as AZM, the tissue/plasma ratio of AMP is better than other beta-lactams including benzylpenicillin and flucloxacillin (17). Better tissue penetration might be a mechanism of the AMP-mediated resolution.

Given increasing antibiotics resistance, the overuse of antibiotics is a global concern. As the AAE suggests, we should limit the use of adjunctive antibiotic treatment in cases with evidence of systemic involvement and patients with immunocompromised/predisposing conditions. In the present study, antibiotic treatment led to the resolution of pre-existing experimental periapical inflammation. However, there is no intention to recommend the use of antibiotics for routine root canal treatment with this data. Our data provide a perspective on host response in antibiotic selection in endodontic treatments. This point needs to be carefully elucidated in well-designed clinical trials.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wang CY, Stashenko P. Kinetics of bone-resorbing activity in developing periapical lesions. J Dent Res 1991; 70:1362–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nair PN. Apical periodontitis: a dynamic encounter between root canal infection and host response. Periodontol 2000 1997; 13:121–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sasaki H, Hou L, Belani A, et al. IL-10, but not IL-4, suppresses infection-stimulated bone resorption in vivo. J Immunol 2000. ;165:3626–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howait M, Albassam A, Yamada C, et al. Elevated Expression of Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Promotes Inflammatory Bone Resorption Induced in a Mouse Model of Periradicular Periodontitis. J Immunol 2019;202:2035–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang CY, Stashenko P. The role of interleukin-1 alpha in the pathogenesis of periapical bone destruction in a rat model system. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1993;8:50–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruytinx P, Proost P, Van Damme J, Struyf S. Chemokine-Induced Macrophage Polarization in Inflammatory Conditions. Front Immunol 2018;9:1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morikawa K, Watabe H, Araake M, Morikawa S. Modulatory effect of antibiotics on cytokine production by human monocytes in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1366–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ianaro A, Ialenti A, Maffia P, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of macrolide antibiotics. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2000;292:156–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parnham MJ, Erakovic Haber V, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, et al. Azithromycin: mechanisms of action and their relevance for clinical applications. Pharmacol Ther 2014;143:225–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balto K, Müller R, Carrington DC, et al. Quantification of periapical bone destruction in mice by micro-computed tomography. J Dent Res 2000;79:35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirai K, Furusho H, Hirota K, Sasaki H. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 attenuates periapical inflammation and bone loss. Int J Oral Sci 2018;10:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maslowski KM, Mackay CR. Diet, gut microbiota and immune responses. Nat Immunol 2011; 12:5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gladue RP, Bright GM, Isaacson RE, Newborg MF. In vitro and in vivo uptake of azithromycin (CP-62,993) by phagocytic cells: possible mechanism of delivery and release at sites of infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1989; 33:277–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foulds G, Shepard RM, Johnson RB. The pharmacokinetics of azithromycin in human serum and tissues. J Antimicrob Chemother 1990;25 Suppl A:73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matzneller P, Krasniqi S, Kinzig M, et al. Blood, tissue, and intracellular concentrations of azithromycin during and after end of therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013;57:1736–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Escalante MG, Eubank TD, Leblebicioglu B, Walters JD. Comparison of Azithromycin and Amoxicillin Before Dental Implant Placement: An Exploratory Study of Bioavailability and Resolution of Postoperative Inflammation. J Periodontol 2015;86:1190–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cross SE, Thompson MJ, Roberts MS. Distribution of systemically administered ampicillin, benzylpenicillin, and flucloxacillin in excisional wounds in diabetic and normal rats and effects of local topical vasodilator treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1996;40:1703–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levert H, Gressier B, Moutard I, et al. Azithromycin impact on neutrophil oxidative metabolism depends on exposure time. Inflammation 1998;22:191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy BS, Sundareshan V, Cory TJ, et al. Azithromycin alters macrophage phenotype. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:554–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirsch R, Deng H, Laohachai MN. Azithromycin in periodontal treatment: more than an antibiotic. J Periodontal Res 2012;47:137–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang B, Bailey WM, Kopper TJ, et al. Azithromycin drives alternative macrophage activation and improves recovery and tissue sparing in contusion spinal cord injury. J Neuroinflammation 2015;12:218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amantea D, Certo M, Petrelli F, et al. Azithromycin protects mice against ischemic stroke injury by promoting macrophage transition towards M2 phenotype. Exp Neurol 2016; 275:116–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balloy V, Deveaux A, Lebeaux D, et al. Azithromycin analogue CSY0073 attenuates lung inflammation induced by LPS challenge. Br J Pharmacol 2014;171:1783–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gensel JC, Kopper TJ, Zhang B, et al. Predictive screening of M1 and M2 macrophages reveals the immunomodulatory effectiveness of post spinal cord injury azithromycin treatment. Sci Rep 2017; 6:7–40144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mencarelli A, Distrutti E, Renga B, et al. Development of non-antibiotic macrolide that corrects inflammation-driven immune dysfunction in models of inflammatory bowel diseases and arthritis. Eur J Pharmacol 2011; 665:29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]