Abstract

Proteasome is the principal hydrolytic machinery responsible for the great majority of protein degradation. The past three decades have testified prominent advances about proteasome involved in almost every aspect of biological processes. Nonetheless, inappropriate increase or decrease in proteasome function is regarded as a causative factor in several diseases. Proteasome abundance and proper assembly need to be precisely controlled. Indeed, various neurodegenerative diseases including Parkinson’s disease (PD) share a common pathological feature, intracellular protein accumulation such as α-synuclein. Proteasome activation may effectively remove aggregates and prevent the neurodegeneration in PD, which provides a potential application for disease-modifying treatment. In this review, we build on the valuable discoveries related to different types of proteolysis by distinct forms of proteasome, and how its regulatory and catalytic particles promote protein elimination. Additionally, we summarize the emerging ideas on the proteasome homeostasis regulation by targeting transcriptional, translational, and post-translational levels. Given the imbalanced proteostasis in PD, the strategies for intensifying proteasomal degradation are advocated as a promising approach for PD clinical intervention.

Subject terms: Neural ageing, Neuronal physiology

Facts

Proteasome homeostasis undergoes dynamic and reversible regulation at transcriptional, translational, and post-translational levels.

The vicious cycle between proteasome dysfunction and protein accumulation plays a key role in PD pathogenesis.

Regulation of proteasome homeostasis serves as a promising approach in PD therapies.

The development of PROTAC opens up new potentials for PD treatment based on proteasome modulation.

Open questions

A number of possible hybrid proteasomes arise in cells. What are the distinct functions of singly or doubly capped proteasomes?

What are the mechanisms by which different transcription factors regulate a separate set of proteasome subunits?

Is there a unified mechanism of protein aggregates and neurodegeneration triggered by proteasome dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease?

How prevalent and what is the significance of proteasome activation-based approach for PD therapies?

Introduction

Proteasome is a ubiquitous and highly plastic multisubunits complex responsible for protein degradation in both cytosol and nucleus. Since its initial discovery in 19871,2, proteasome has been under intensive investigation to explore the inherent logic of proteasome function, including the recognition of ubiquitylated substrates, deubiquitylation of potential targets, translocation of unfolded proteins into the catalytic chamber, and the peptidase features for selective proteolysis3–5. Although widely assumed to be a single entity, there also exists various types of proteasome in cells, such as 26 S proteasome (constitutive proteasome), immunoproteasome, thymoproteasome, and spermatoproteasome6,7. Under certain conditions, specific proteasome is induced to perform different biological functions, while the efforts to distinguish these proteasomes and analyze their respective roles have not been accomplished. Indeed, proteasome is not a stable and static complex serving as a “cellular trashcan”8. The expression of proteasome undergoes dynamic and reversible regulation not only at the transcriptional level but also at the translational and post-translational level, such as phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, ADP-ribosylation, O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc), acetylation, and S-glutathionylation. Even with this information, a comprehensive understanding of the regulatory mechanisms underlying proteasome homeostasis remains elusive.

Proteasome activity becomes gradually impaired during aging and various neurodegenerative disorders including Parkinson’s disease (PD). The compromise of proteasomal degradation leads to aberrant protein aggregates, such as α-synuclein, which in turn binds to proteasome correlated with a reduction in protease activity9,10. These observations indicate a vicious cycle between proteasome dysfunction and protein accumulation in PD pathogenesis. It is thus inferred that proteasome is expected to be an attractive target for PD intervention11,12. Enhancing proteasome function by either increasing subunits assembly or activating 20 S gate opening might be useful for the clearance of protein aggregates. Consistent with this evidence, several small-molecule compounds have been postulated to be an effective approach in PD treatment. The development of proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) represents a burgeoning field and a new therapeutic regimen owing to the capacity of inducing a specific protein degradation, as well as its small-molecule nature and targeting “undruggable” proteins13,14. Additionally, PROTAC provides the opportunity to rapidly degrade proteins of interest, which effectively prevents the compensatory recovery due to the deletion of target proteins13,15. Even so, PROTAC is still an emerging technology, and its future development is also fraught with challenges.

This article reviews recent advances in the multiple regulation of proteasome homeostasis that ensures efficient protein degradation. Major new insights into proteasome activation have also emerged, which not only seems important in regulating protein turnover, but also provides potential application in drug discovery to combat the proteotoxicity in PD.

Components of proteasome

Proteasome, as a multisubunits complex, accounts for the vast majority (at least 80%) of protein degradation. The best known 26 S proteasome, also named standard or constitutive proteasome, is composed of a 20 S core particle (CP or 20 S complex) attached to one or both ends by a 19 S regulatory particle (RP, 19 S complex or PA700). The 19 S complex, as a proteasome activator, is incorporated into two parts: the lid and the base. The lid consists of nine subunits, that is, Rpn3, Rpn5, Rpn6, Rpn7, Rpn8, Rpn9, Rpn11, Rpn12, and Rpn15. The base contains six ATPase subunits (Rpt1-6), as well as Rpn1, Rpn2, Rpn10, and Rpn13 (Table 1). The alternative proteasome activators, including 11 S regulator complex PA28 and PA200 (PSME4), substitute 19 S RP to assemble various forms of proteasome. Three members of PA28 have been identified, namely PA28α (PSME1), PA28β (PSME2), and PA28γ (PSME3). In contrast to PA28α and PA28β which form PA28αβ hetero-heptamer distributed throughout the cytoplasm, PA28γ forms a homo-heptamer predominantly located in the nucleus. Many studies have implicated PA28αβ in the production of major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC I) antigen peptides, and PA28γ has been known to conduct proteasomal degradation of numerous intact proteins16,17.

Table 1.

Proteasome subunits names and function.

| Subcomplex | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Homo sapiens | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19 S lid | Rpn3 | PSMD3 | Structural |

| Rpn5 | PSMD12 | Structural | |

| Rpn6 | PSMD11 | Structural | |

| Rpn7 | PSMD6 | Structural | |

| Rpn8 | PSMD7 | Structural | |

| Rpn9 | PSMD13 | Structural | |

| Rpn11 | PSMD14 | Deubiquitinase, Ub removal | |

| Rpn12 | PSMD8 | Structural | |

| Rpn15 | PSMD9 | Structural | |

| 19 S base | Rpn1 | PSMD2 | Ubp6 and Ub/Ubl binding |

| Rpn2 | PSMD1 | Structural | |

| Rpn10 | PSMD4 | Initial Ub/Ubl binding | |

| Rpn13 | ADRM1 | ||

| Rpt1 | PSMC2 | ATPase subunits, substrates binding, unfolding, and translocation | |

| Rpt2 | PSMC1 | ||

| Rpt3 | PSMC4 | ||

| Rpt4 | PSMC6 | ||

| Rpt5 | PSMC3 | ||

| Rpt6 | PSMC5 | ||

| 20 S α-subunits | α1 | PSMA6 | 20 S gate opening |

| α2 | PSMA2 | ||

| α3 | PSMA4 | ||

| α4 | PSMA7 | ||

| α5 | PSMA5 | ||

| α6 | PSMA1 | ||

| α7 | PSMA3 | ||

| 20 S β-subunits | β1 | PSMB6 | Caspase-like activity |

| β1i | PSMB9 | Chymotrypsin-like activity | |

| β2 | PSMB7 | Trypsin-like activity | |

| β2i | PSMB10 | Trypsin-like activity | |

| β3 | PSMB3 | ||

| β4 | PSMB2 | ||

| β5 | PSMB5 | Chymotrypsin-like activity | |

| β5i | PSMB8 | Chymotrypsin-like activity | |

| β6 | PSMB1 | ||

| β7 | PSMB4 | ||

| Associated DUBs | Ubp6 | USP14 | Deubiquitinase, 19 S activation |

| — | UCH37 |

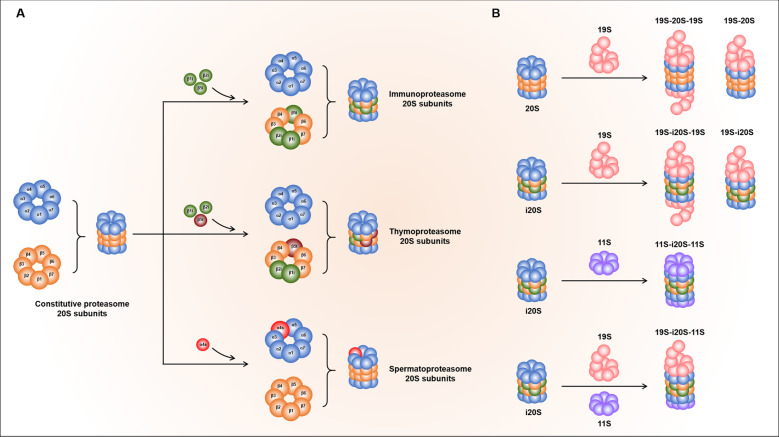

The 20 S complex is a barrel-shaped hollow cylindrical complex with 28 subunits arranged into four heptameric rings, the two outer rings composed of α1–7 subunits and the two inner rings composed of β1–7 subunits. Of note, the proteolytic activities are carried out by three β subunits with peptidase sites, namely β1, β2, and β5, which possesses the caspase-like, trypsin-like, and chymotrypsin-like activities, respectively. Upon certain stimulus, three catalytic subunits β1, β2, and β5 subunits can be replaced by their homologues β1i, β2i, and β5i to form immunoproteasome18, β5t substitutes β5 to form thymoproteasome19, and α4s subunits replace their constitutive counterparts α4 to form spermatoproteasome20. Currently, a number of possible hybrid proteasomes arise in cells because of the attachment of different proteasome activators to one or both sides of 20 S CP (Fig. 1). Nonetheless, the specific function of singly or doubly capped proteasomes remains to be elucidated.

Fig. 1. Different types of proteasome.

A Three catalytic subunits β1, β2, and β5 subunits can be replaced by their homologues β1i, β2i, and β5i to form immunoproteasome, β5t substitutes β5 to form thymoproteasome, and α4s subunits replace their constitutive counterparts α4 to form spermatoproteasome. B The combination of 20 S CP with proteasome activator. The 19 S or 11 S complex can associate at one or both ends of 20 S to form different types of proteasome.

Regulation of proteasome homeostasis

Transcriptional regulation of constitutive proteasome

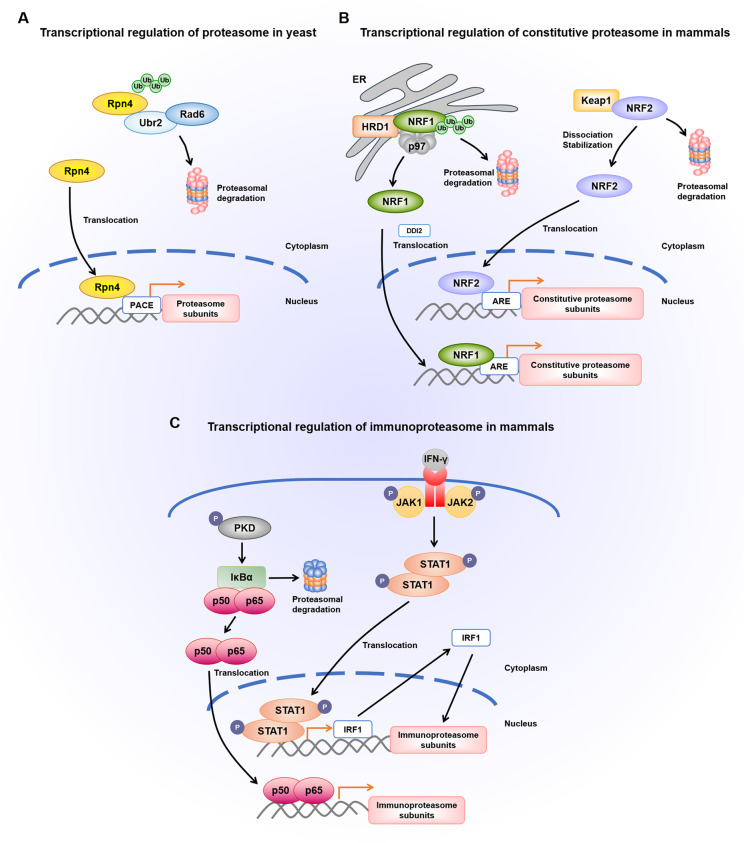

In 1999, Mannhaupt et al. discovered a unique activating sequence (5’-GGTGGCAAA-3’) called proteasome-associated control element (PACE), which is localized in the promoters of most proteasome subunits21. In yeast, Rpn4 acts as a common transcription factor binding to PACE of genes encoding proteasome subunits to maintain the normal abundance of proteasome21–23. Notably, Rpn4 is extremely short-lived (t1/2 ~2 min) because the N-terminal region of Rpn4 contains a portable degradation signal for the continual proteasomal degradation. As a consequence, Rpn4 augments the synthesis of proteasome subunits in response to proteasome inhibition, which yields a negative feedback circuit. By contrast, Rpn4 deletion in yeast disrupts the expression of proteasome, therefore cells become more susceptible to various stimulus such as DNA damage and oxidative stress24. In yeast, transcription factor Rpn4 is indispensable for the compensatory increase of proteasome subunits to cope with stress conditions (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Transcriptional regulation of proteasome expression.

A Transcriptional regulation of proteasome in yeast. Rpn4 serves as a transcription factor with short half-life (t1/2 ~2 min) owing to the proteasomal degradation mediated by E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme Rad6 and E3 ubiquitin ligase Ubr2. Upon proteasome inhibition, Rpn4 is translocated into the nucleus, where it binds to PACE sequence in the promoters of proteasome subunit genes, resulting in the compensatory increase of proteasome expression. B Transcriptional regulation of constitutive proteasome in mammals. NRF1 resides in the ER, which is degraded via ERAD pathway requiring ER-resident ubiquitin ligase HRD1 and ATPase p97. When the proteasome is inhibited, NRF1 is cleaved by DDI2, and then translocated to the nucleus where it binds ARE and activates the transcription of proteasome genes. During oxidative stress, NRF2-Keap1 complex disassociates, and NRF2 translocates into the nucleus to transcriptionally regulate proteasome expression. C Transcriptional regulation of immunoproteasome in mammals. Under the stimulation of IFN-γ, activated JAK1 and JAK2 leads to the dimerization and phosphorylation of STAT1, which translocates into the nucleus and binds to IRF1. Following translation, IRF1 moves back into the nucleus to increase the transcription of immunoproteasome. Upon oxidative injury, phosphorylated protein kinase D (PKD) leads to the disassociation of IκBα from NF-κB. In turn, IκBα is degraded and NF-κB translocates into the nucleus to regulate the expression of immunoproteasome.

In mammals, there also exists the transcriptional regulation of proteasome expression once proteasome function is impaired (Fig. 2). Despite the homologues of Rpn4 in mammalian cells have not been found, several transcription factors are implicated to fulfill the function of Rpn4. The expression of proteasome genes, including six CP subunits (α2, α5, α7, β3, β4, and β6) and five RP subunits (Rpt1, Rpt5, Rpt6, Rpn10, and Rpn11), is tightly regulated by nuclear transcription factor Y (NF-Y). Knockdown of NF-Y remarkably downregulates proteasome genes expression and inhibits cellular proteasome function25. Forkhead box O4 (FOXO4), an insulin/insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) responsive transcription factor, amplifies proteasome activity by modulating Rpn6 expression in human embryonic stem cells26. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), which is activated through Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT pathway, transcriptionally regulates the expression of β527. In addition, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) is initially implicated to induce β5 expression upon exposure to oxidative stress28. Later, antioxidant response elements (AREs) sequences have been found in the 5’-untranslated region of 20 S proteasome subunits genes29. Intriguingly, a later study ascribes the induction of proteasome biogenesis to NRF130. Echoing these results, brain-specific Nrf1-/- knockout mice exhibit the downregulation of proteasomal genes, accompanied by the accumulation of polyubiquitylated proteins and age-dependent neurodegeneration31.

Transcriptional regulation of immunoproteasome

Unlike the constitutive proteasome, immunoproteasome subunits lack functional ARE binding sequences. The LMP2 gene encoding β1i subunit contains a bidirectional promoter characterized by the lack of TATA box and the presence of several GC boxes, which are likely the transcriptional start sites. Multiple transcription factors including signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1)/interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1) dimers, nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), SP-1, AP-1, cAMP responsive element binding protein (CREB), and Zif268 (also known as Egr1), are involved in the LMP2 (β1i) gene expression32. Furthermore, the promoter regions of LMP7 and MECL-1 encoding β5i and β2i, respectively, also contain NF-κB consensus sequence, cAMP regulatory elements, along with SP-1 and IRF1 binding sites18,33,34. In this case, the transcriptional regulation of β1i, β2i, and β5i share the relatively similar mechanisms. Upon interferon-γ (IFN-γ) stimulation, the activation of JAK1 and JAK2 causes the dimerization and phosphorylation of STAT1, which translocate into the nucleus and combine with IRF1 to promote its transcription. Then, IRF1 migrates back into the nucleus to stimulate the expression of immunoproteasome subunits. In addition, a potential alternative manner for immunoproteasome regulation is through NF-κB pathway. Upon oxidative injury, the phosphorylation of protein kinase D (PKD) disassociates IκBα from NF-κB. Upon the degradation of IκBα by the proteasome, NF-κB can translocate into the nucleus triggering the transcription of immunoproteasome subunits (Fig. 2).

Translational regulation of proteasome

The activation of yeast mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) Mpk1 followed by target of rapamycin complex 1 (TORC1) inhibition facilitates a rapid rise in the expression of RP assembly chaperones (RACs) and proteasome subunits. This process of proteasome homeostasis regulation is evolutionarily conserved in mammals. ERK5 (also known as MAPK7), the mammalian orthologue of Mpk1, also mediates the upregulation of RACs and proteasome abundance upon mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) inhibition35. Considering that neither the mRNA levels nor the protein stability of proteasome subunits are altered in response to the inhibition of TORC1/mTORC1, the regulation of proteasome by Mpk1/ERK5 probably occurs at the translational level36. It is clear that mTORC1 serves as a master regulator of proteasome abundance, whereas the relationship between mTORC1 and proteasome homeostasis seems to be controversial. Another study reveals that mTORC1 activation promotes the efficiency of proteasome-mediated protein degradation by increasing cellular proteasome content37. In this regard, it will be necessary to resolve the discrepancy of how mTORC1 affects the proteasome homeostasis under the particular cellular conditions.

Post-translational modifications of proteasome

Phosphorylation

In 1989, Haass and Kloetzel first reported the possibility that the phosphorylation of proteasome subunits had an impact on proteolytic activities during the Drosophila development38. In the following years, phosphorylation proteomics have shown a great deal of phosphorylation sites, which exist in almost every proteasome subunit8. Protein kinase A (PKA) was probably the first reported kinase involved in the phosphorylation of proteasome subunits39. Subsequent studies have shown that PKA directly phosphorylate Rpt6 at Ser120 and Rpn6 at Ser14, leading to the increased proteasomal peptidase activities40–42. PKA activation enhances the capacity of proteasome and promotes the elimination of protein aggregates41. In rat spinal cord neurons, PKA-mediated increased proteolytic activities reduce the accumulation of ubiquitylated proteins and protect cells from inflammatory injury43. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CAMKIIα) directly phosphorylates Rpt6 at Ser120 and stimulates proteasome activity44,45. Mutation of Rpt6 at Ser120 blocks proteasome-dependent regulation of synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus46,47 (Table 2). Pharmacological inhibition of CaMKIIα abolishes the increase in proteolytic activity and the initiation of memory reconsolidation process48,49.

Table 2.

An overview of proteasome related post-translational modifications.

| Modifications | Targets | Enzymes | Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorylation | Rpn1 (S361) | UBLCP1 | Proteasome activity ↑; 26 S proteasome assembly ↑ | 146 |

| Rpn2 (Y273) | p38 MAPK | Proteasome activity ↓; ubiquitylated protein degradation ↓ | 52 | |

| Rpn6 (S14) | PKA | Proteasome activity ↑; ubiquitylated protein degradation ↑ | 41,42 | |

| Rpt3 (T25) | DYRK2 | Proteasome activity ↑; substrate translocation and degradation ↑; cell proliferation and tumorigenesis | 50,51 | |

| Rpt6 (S120) | PKA, CAMKIIα | Proteasome activity ↑; synaptic plasticity, learning and memory | 40,41 | |

| α4 (Y153) | c-Abl/Arg | Proteasome activity ↓ | 53 | |

| α4 (Y106) | c-Abl/Arg | α4 degradation ↓; proteasome abundance ↑ | 54 | |

| α7 (S243, S250) | CK2 | Stabilizing RP-CP interaction; Ecm29 binding ↑ | 55,147 | |

| Ubiquitylation | Rpn10 | Ube3c, Rsp5, Ubp2 | Proteasome activity ↓; ubiquitylated conjugates affinity ↓ | 56,57 |

| Rpn13 | Ube3c | Ubiquitylated protein degradation ↓ | 58 | |

| α2 | ALAD | Substrates entry into 20 S CP ↓ | 59 | |

| ADP-ribosylation | Nuclear proteasome | PARP | Proteasome activity ↑; oxidatively histone degradation ↑; cytokine-mediated neuroinflammation ↓ | 60,61 |

| O-GlcNAc | Rpt2 | OGT, OGA | Proteasome activity ↓; ubiquitylated protein degradation ↓ | 65 |

| Acetylation | α6, β3, β6, β7 | HDAC | Proteasome activity ↑ | 67 |

| S-glutathionylation | Rpn1, Rpn2 | — | Proteasome activity ↓ | 148 |

| α5, α6, α7 | Glutaredoxin 2, thioredoxins 1/2 | 20 S gate opening ↑; oxidized and unfold protein degradation ↑ | 149,150 |

Dual-specificity tyrosine-regulated kinase 2 (DYRK2) phosphorylates a particular site of the proteasome, Rpt3 Thr25, leading to the enhanced substrate translocation and degradation50,51. Under osmotic stress conditions, p38 MAPK negatively regulates the proteasome activity by phosphorylating Rpn2 at Thr273, so as to induce the accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins52. The nonreceptor tyrosine kinases c-Abl and Arg directly phosphorylate α4 at two tyrosine residues, Tyr106 and Tyr153. α4 Tyr153 phosphorylation inhibits proteasome activity, whereas Tyr106 phosphorylation suppresses the degradation of α4, therefore upregulating proteasome abundance53,54. These findings suggests the dual roles of c-Abl/Arg in the proteasome homeostasis and activity. Moreover, casein kinase 2 (CK2) phosphorylates α7 at Ser243 and Ser250, which appears to stabilize the RP-CP interaction and promote the binding of proteasome quality control factor Ecm2955 (Table 2).

Ubiquitylation

Rpn10 is the first proteasome subunit identified as a proteasome substrate, as well as a major target of ubiquitylation. It has been shown that Rpn10 undergoes the proteasomal degradation facilitated by E3 ubiquitin ligase Ube3c56. Indeed, Ube3c endows proteasomes with the capacity to extend the ubiquitin chains on targets, which can be disassembled by a proteasome-associated deubiquitinating enzymes (DUB), Ubp6. Moreover, Isasa et al. have reported that Rpn10 is ubiquitylated by Rsp5 and deubiquitylated by Ubp2. Under stress conditions, Rpn10 monoubiquitylation is reduced, which in turn rescues proteasome function by enhancing the proteolytic activity, providing a stress sensitive mechanism to control proteasome catalytic activity57. Additionally, when proteasome function is inhibited by bortezomib, Rpn13 becomes extensively and selectively polyubiquitylated by E3 ligase Ube3c, which strongly inhibits the proteasome’s ability to degrade ubiquitin conjugates, but not hydrolyzing peptides and non-ubiquitylated proteins58 (Table 2). It has also been reported that delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) serves as an endogenous proteasome inhibitor, which is associated with the ubiquitylation of α2 subunit, thereby inhibiting the entry of substrates into 20 S catalytic chamber59. Although the consequence of proteasome subunits ubiquitylation under different conditions remain a subject for further study, this modification appears to be valuable to evaluate the proteasome function.

ADP-ribosylation

ADP-ribosylation is the transfer of ADP-ribose moiety from NAD+ to target proteins. The functional interaction of poly(ADP-ribose) with 20 S proteasome leads to a specific enhancement of the peptidase activity. ADP-ribosylation activates nuclear 20 S proteasome to efficiently degrade oxidatively modified histone proteins, which is proposed as an adaptive response to oxidative defense60. Given the important role of ADP-ribosylation in DNA repair, the activation of proteasome is accompanied by the degradation of oxidized histones in the nucleus, which will otherwise make DNA repair impossible61. Besides, proteasome modification via ADP-ribosylation participates in cytokine-mediated neuroinflammation. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) enables activated microglia to resist oxidative injury through an upregulation of the nuclear proteasome activity, resulting in the enhanced protein turnover and degradation of oxidatively modified proteins62. Of note, PARP inhibition impairs activated, but not resting microglia owing to the reduced proteasomal degradation, which might be beneficial, particularly in PD in which activated microglia acts as a pathogenic factor. Considering that glial cells are involved in the maintenance of neuronal function, PARP might be taken into consideration with the intention of ensuring neuronal survival.

O-Glycosylation

O-GlcNAc is a regulatory post-translational modification in which O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) adds GlcNAc monosaccharides to the hydroxyl groups on serine or threonine residues, while O-GlcNAcase (OGA) removes this modification63. Both OGT and OGA are abundant in the brain, with the highest expression in the hippocampal granular and pyramidal neurons and cerebellar Purkinje cells64. Pharmacological inhibition of OGA activity by streptozotocin or OGA knockdown leads to a rapid accumulation of O-GlcNAc and inhibition of proteasome function, thereby exacerbating neuronal apoptosis. Exposure of 26 S, but not 20 S, proteasome to OGT impairs the proteolysis of transcription factor SP-1 and a hydrophobic peptide owing to the inhibition of 19 S ATPase activities. The degradation of ubiquitinylated proteins requires the opening of 20 S CP probably by Rpt2, whose O-GlcNAc modification correlates inversely with the proteasome activity65 (Table 2). In addition, the biotin-cystamine tag strategy identifies six O-GlcNAc sites within the murine 20 S CP, that is, α1 (Ser5), α4 (Ser130), α5 (Ser198), α6 (Ser110), and β6 (Ser57 and Ser208). O-GlcNAc sites of α1 and α5 are only found in immunoproteasomes, whereas β6 Ser208 modification is detected only in brain proteasomes66. O-GlcNAc modification may serve as an important regulation system in the proteasome homeostasis, and investigating the biological impact of O-GlcNAc on proteasome seems to be a challenging but promising field of research.

Acetylation

Acetylation is a reversible post-translational modification of proteins, regulated by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), which add and remove acetyl groups from lysine residues, respectively. Despite the well-documented function of acetylation in modulating gene transcription and protein expression, its role in protein degradation has been recognized. Five lysine acetylation sites on murine 20 S subunits are identified following HDAC inhibition, that is, Lys30 and Lys115 of α6 subunit, Lys77 of β3 subunit, Lys203 of β6 subunit, and Lys201 of β7 subunit (Table 2). The enhanced acetylation of 20 S proteasome subunits leads to an elevation of proteolytic capacity67. In this regard, HDAC inhibitors might be a promising class of pharmacological agents for increasing the proteasomal proteolytic activity. Beyond that, six Lys residues (Lys6, Lys11, Lys27, Lys33, Lys48, and Lys63) on ubiquitin have been reported to be acetylated in proteomics datasets68. Acetylated ubiquitin does not affect the monoubiquitylation of substrates, but inhibits Lys11, Lys48, and Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains elongation69. Ubiquitin is subject to acetylation to modulate protein degradation, thus providing a new regulatory layer to ubiquitin-proteasome biology. Further research needs to identify the HATs and HDACs responsible for proteasome acetylation and deacetylation, as well as functional roles of acetylated ubiquitin.

Imbalance of proteostasis in PD

Proteasome dysfunction exacerbates protein aggregates in PD

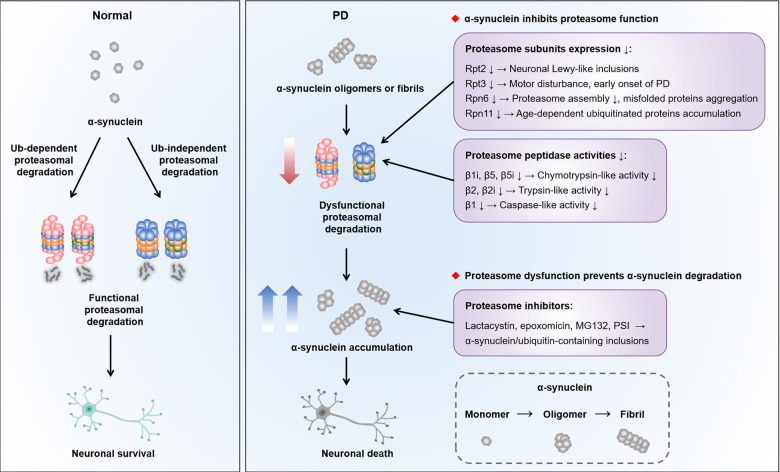

In PD, the selective loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) and subsequent loss of dopamine in the striatum leads to the classical motor features, such as resting tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural instability. Although the exact pathogenesis of PD has not been revealed yet, it is generally accepted that disruption of cellular proteostasis is linked to various neurodegenerative diseases including PD70. In eukaryotic cells, two major protein clearance pathways, proteasome and autophagy, are interrelated to maintain cellular proteolysis and ensure that cells have the adequate proteins they need71,72. The proteasome, in collaboration with a refined ubiquitin system, selectively degrades short-lived proteins as well as misfolded or damaged proteins in the cytoplasm, nucleus and endoplasmic reticulum. By contrast, autophagy coupled with lysosome is essential to degrade longer-lived macromolecules, cytosol fractions, and organelles through three autophagic pathways, macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA). Indeed, maintaining proteome balance is a challenging work in the face of various external and internal stimuli owing to the age-dependent decline in the proteolysis capacity and impaired proteasomal degradation73. The resulting aberrant accumulation of misfolded and aggregated proteins probably overload the cellular ability to degrade rendering the neurons susceptible to the pathological injury (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. The interplay between proteasome impairment and α-synuclein accumulation in PD.

Under physiological state, α-synuclein is highly soluble and enriched at presynaptic terminals, which can be degraded through ubiquitin-dependent and ubiquitin-independent manner, so as to maintain the survival of neurons. In PD, α-synuclein accumulates in neuronal cell bodies to form a major component of aberrant aggregates known as Lewy bodies. α-synuclein is able to transform in different conformations, including monomers, oligomers (soluble conformations), and fibrils (insoluble conformations). The impairment of proteasome function resulting from the decreased subunits expression and proteolytic activities disturbs the degradation of substrates. Additionally, α-synuclein has been reported to inhibit the function of proteasome, which further aggravates the accumulation of α-synuclein. This suggests a vicious cycle between proteasomal impairment and proteotoxicity in PD.

In 2001, McNaught and colleagues first reported the decreased proteasome hydrolytic activities in PD74. Specifically, in the SN instead of other brain regions of PD patients, there is a loss of α-subunits in dopaminergic neurons and a reduction in all of three peptidase activities75. In contrast, it is probable that the reduced proteasome activity could be a consequence of the neurodegeneration, which may underly the vulnerability of the SN in PD. ATPase subunit Rpt2 conditional knockout in dopaminergic neurons displays the depletion of 26 S proteasome, resulting in the presence of intraneuronal Lewy-like inclusions in the nigrostriatal pathway76. Besides, insertion and deletion variants in the Rpt3 gene correlate with the early onset of PD77. Conditional knockout of Rpt3 in motor neurons causes severe motor dysfunction, accompanied by progressive loss of neurons and gliosis78. Rpn11 overexpression prevents the age-dependent deficit in 26 S proteasome activity and ubiquitin-conjugated proteins accumulation79. Furthermore, Rpn6 enhances the proteasome assembly and activity, which is critical for the stabilization of CP and the proper interaction with RP to improve age-related protein aggregates26,80. These data demonstrate that the maintenance of proteasome function is of great importance for the adequate degradation of unwanted proteins and slowing down the neurodegeneration in PD. Even with this information, it is still challenging to pinpoint the different functions produced by the multiple proteasome subunits, which is a major hurdle toward understanding the regulation of proteasome in PD.

Impairment of α-synuclein degradation through proteasome

Emerging evidence has demonstrated that the abundant fibrillar α-synuclein inclusions known as Lewy bodies is one of the pathological hallmarks in PD. α-Synuclein is encoded by SNCA gene, which is enriched in presynaptic terminals to modulate synaptic-vesicle trafficking, bind membranes and induce membrane curvature. Point mutations in SNCA (A30P, E46K, H50Q, G51D, A53E, and A53T) and genomic duplications or triplications within SNCA locus lead to the autosomal dominant familial PD81,82. Indeed, α-synuclein pathology follows a stereotypical “prion-like” propagation pattern, resulting in a cell-to-cell transmission to drive neurodegeneration in PD. Several strategies, such as using antibodies to impede the spreading of α-synuclein and testing minute quantities of α-synuclein in cerebrospinal fluid by seeding aggregation assay, have been implicated for PD therapies83,84. The homeostasis of α-synuclein is maintained under intrinsic surveillance mechanisms including ubiquitin-dependent and -independent proteasomal degradation, macroautophagy and CMA. Different forms of α-synuclein are degraded by multiple routes depending on the overall protein burden, localization and pathological states. Proteasome and macroautophagy are capable of degrading mutant α-synuclein or intermediate oligomers, while CMA possesses a specific ability to degrade monomers and dimers of α-synuclein85,86. Extracellular α-synuclein is cleared by proteases, or spread among neighboring cells and eliminated within lysosomes. However, the mechanism governing whether α-synuclein will be cleared by proteasome or autophagy remains unknown.

Treatment with proteasome inhibitors leads to the accumulation of ubiquitin and α-synuclein immunoreactive inclusions, which supports the concept that defects in the proteasome pathway might uncover the nigral pathology in familial and sporadic forms of PD84–86. Consistent with these findings, systemic exposure to proteasome inhibitors in rats causes the formation of α-synuclein/ubiquitin-containing inclusions resembling Lewy bodies in the remaining neurons and animals develops progressive motor deficits which closely recapitulates the main pathological features of PD87. Similar to other PD-related neurotoxins, proteasome inhibitors might offer an alternative way to model the disturbance of protein homeostasis and the chronic progressive nature of neurodegeneration as it occurs in PD. Even so, systemic administration of PSI has been challenged due to several laboratories inability to replicate the mode88–90 or reproduce only partial features such as transient motor deficits without dopaminergic neurons degeneration91 or modest depletion of striatal dopamine without motor disorder92. The impaired turnover of α-synuclein represents a critical aspect of neurodegeneration in PD.

α-Synuclein disrupts proteasome function

Numerous studies have shown that α-synuclein can inhibit proteasome activity, especially in the presence of oligomer or fibril species10. PC12 cells expressing A53T mutant α-synuclein exhibit the impaired proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity and disruption of the ubiquitin-dependent degradation system, manifested by an increase in ubiquitin-conjugated aggregates93. Their observations have been supported by another study using the same cell line expressing mutant α-synuclein, in which the peptidase activities of proteasome are reduced resulting in mitochondrial abnormalities and neuronal death94. Of note, proteasome function is inhibited not only by mutant α-synuclein, but also by wild-type species. Human neuroblastoma BE-M17 cells stably expressed wild-type α-synuclein exhibit an ~50% reduction in ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation95. A study with yeast also demonstrates that wild-type and A30P mutant α-synuclein impair proteasome-mediated protein degradation, but have little effects on intracellular proteasome content or protein ubiquitylation96. More recently, McKinnon C et al. report that α-synuclein overexpression leads to the early-onset catalytic impairment of 26 S proteasome, which is associated with selective accumulation of α-synuclein phosphorylated at Ser129 and precedes the onset of motor deficits and dopaminergic neurons degeneration10. In addition, α-synuclein oligomers associate with the 26 S proteasome, leading to a significant inhibition of proteasomal activities without affecting the levels or assembly of 26 S proteasome97. The proposed mechanisms of how α-synuclein inhibits the proteasome function may be due to the direct interaction with Rpt5 or β5 subunit95,98. Overall, the impaired proteasome function aggravates the accumulation of α-synuclein, which in turn binds to the proteasome, thereby inhibiting its proteolytic activity. The vicious cycle between proteasomal impairment and α-synuclein aggregation may provide an insight into the putative neuroprotective therapies for PD.

Proteasome activation-based approach for PD therapies

Small-molecule compounds

Enhancing proteasome activity by small-molecule compounds has been regarded as a promising strategy to treat or prevent PD. USP14, a proteasome-associated DUB, contains a catalytic domain at the C terminus and a ubiquitin-like (Ubl) domain at the N-terminus. The binding of USP14 to Rpn1 subunit through Ubl enhances its deubiquitinating activity, which is responsible for the removement of ubiquitin chains and prevent the release of ubiquitin to the proteolytic channel. Proteasomes lacking USP14 exhibit higher peptidase activity and ubiquitin-independent proteolysis99. In 2010, Lee et al. have identified IU1 as a selective small-molecule inhibitor of USP14 through high-throughput screen. IU1 treatment significantly accelerates the elimination of oxidized proteins, such as tau and TDP43, thus enhancing the resistance to oxidative stress100. Later, the improved USP14 inhibitor IU1-47, with a 10-fold more potent and retains specificity for USP14, has been found to stimulate the degradation of wild-type and pathological tau. Notably, a specific residue in tau (Lys174) is critical for IU1-47-mediated tau degradation101 (Table 3). Presumably, further studies are needed to determine the effects of USP14 inhibitors on the proteasomal degradation of α-synuclein in PD.

Table 3.

Commonly used proteasome activation agents.

| Agents | Targets | Initial study results | Clinical and/or other uses | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IU1/IU1-47 | USP14 inhibitor | Proteasome activity ↑; tau and TDP43 degradation ↑ | Investigational small-molecule compound | 99,101 |

| Geldanamycin | HSP90 inhibitor | Oligomeric α-synuclein, phosphorylated tau, and Htt aggregation ↓ | Antibiotic; potential use in cancer | 105,106,111 |

| 17-AAG | HSP90 inhibitor | α-synuclein oligomers ↓; Aβ-induced synaptic toxicity and memory impairment ↓ | Potential anticancer drug | 108–110 |

| YM-1 | HSP70 activator | Client proteins ubiquitylation and polyQ AR degradation ↑ | Investigational small-molecule compound | 112 |

| DMF | NRF2 activator | Proteasome activity ↑; α-synuclein aggregation ↓ | Clinical use in MS treatment | 115,116 |

| Sulforaphane | NRF2 activator | Proteasome activity ↑; mHtt degradation ↑ | Naturally occurring compound | 117 |

| EGCG | NRF2 activator | α-synuclein fibrillation and aggregation ↓ | Naturally occurring compound | 118 |

| Curcumin | NRF2 activator | Proteasome activity ↑; α-synuclein aggregation ↓ | Naturally occurring compound | 119,120 |

| ASC-JM17 | Curcumin analog, NRF1 and NRF2 activator | Proteasome subunits expression↑; antioxidant enzymes ↑ | Potential use in SBMA and other polyglutamine diseases | 121 |

| Lcariin | NRF1 agonist | HRD1 expression ↑; ER stress-induced apoptosis ↓ | Potential use in neuronal protection | 122 |

| sCGA884, sCIN027 | NRF1 agonists | Proteasome degradation ↑ | Investigational small-molecule compound | 123 |

| Rolipram | PDE4 inhibitor, cAMP-PKA pathway activation | Proteasome activity ↑; aggregated tau ↓; cognition improvement | Potential use in depression and autoimmune disorders | 124 |

| PD169316 | p38 MAPK inhibitor | Proteasome activity ↑; ubiquitylated protein and α-synuclein degradation ↑ | Investigational small-molecule compound | 125 |

| Nilotinib | Second generation of c-Abl inhibitor | α-synuclein aggregation ↓; normalizing motor disturbance | Clinical use in CML treatment; phase 2 clinical trial of PD | 127,128,132,133 |

| QC-01-175 | Transformation of 18F-T807 into tau ligand, coupled with a linker to CRL4CRBN | Pathological tau degradation ↑ | Investigational PROTAC | 143 |

Critical proteins that unfold and aggregate in neurodegenerative diseases, such as α-synuclein, tau, huntingtin (Htt), and polyglutamine androgen receptor (polyQ AR), are client proteins of heat shock protein 90 (HSP90). HSP90/HSP70-based chaperone machinery has been identified as a key regulator of proteostasis owing to its role in the protein quality control102. Nonetheless, HSP90 and HSP70 possess opposing effects on client proteins stability. HSP90 prevents the degradation of proteins through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, whereas HSP70 promotes ubiquitylation for proteasomal degradation dependent on E3 ubiquitin ligase C terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein (CHIP). This indicates that an effective way to eliminate the aggregation of neurotoxic proteins may be to inhibit HSP90 or promote HSP70 function103. Among the compounds that inhibit HSP90, geldanamycin acts as a nucleotide to inhibit the intrinsic ATPase activity of the chaperone104. It has been reported that geldanamycin facilitates the degradation of oligomeric α-synuclein, phosphorylated tau, and Htt aggregates in vivo105–107. The less toxic analogue of geldanamycin, 17-AAG, has improved brain permeability, which inhibits the formation of α-synuclein oligomer and rescues cytotoxicity mediated by secreted α-synuclein108. Furthermore, 17-AAG can reduce tau pathology and attenuate Aβ-induced synaptic toxicity and memory impairment109–111. YM-1 allosterically stimulates the activity of HSP70 and enhances its binding to unfolded substrates. Treatment of YM-1 promotes the clearance of polyglutamine proteins and increase CHIP-dependent ubiquitylation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase112,113 (Table 3). The compounds that promote HSP70-dependent proteasomal degradation in combination with HSP90 inhibitors might be beneficial for the clearance of aggregated proteins, which should be tested in PD models.

Transcriptional activation of proteasome expression

Considering that the formation of proteasome is energetically costly, the fine tuning mechanisms are required to maintain sufficient amount of proteasomes to combat the proteotoxicity. Transcription factor NRF2 has been proved to reduce steady-state levels of α-synuclein, shorten its half-life in part by accelerating the degradation of α-synuclein114. Pharmacological activation of NRF2 by dimethyl fumarate (DMF), a drug already in use for multiple sclerosis (MS), significantly reduces α-synuclein aggregates and rescues neurons from oxidative stress-induced injury115,116. Several naturally occurring NRF2 activators, such as sulforaphane, epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), and curcumin, stimulate NRF2 signaling pathway to regulate proteostasis. Sulforaphane activates protein degradation machineries and promotes mutant Htt degradation via proteasome117. EGCG can inhibit α-synuclein fibrillation and aggregation, as well as protect PC12 cells against α-synuclein-mediated toxicity118. Additionally, curcumin has been found to prevent the aggregation of α-synuclein in the dopaminergic neurons119,120. A novel curcumin analog, called ASC-JM17, is characterized to strikingly activate NRF1 and NRF2, which further increases the expression of proteasome subunits so as to mitigate the proteotoxicity in spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA) and other polyglutamine diseases121. Moreover, lcariin functions as an inducer of NRF1 by increasing the expression of HRD1, an ER-anchoring E3 ubiquitin ligase, and protect neurons from ER stress-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells122. Recently, high-throughput chemical screen has identified pharmacological agonists of NRF1, that is, sCGA884 and sCIN027. Co-treatment of these activators and MG-132 induce a dramatic transcriptional activity of NRF1. However, there exists an important limitation that single treatment of sCGA884 or sCIN027 leads to only partially efficacious NRF1 transcriptional activation123. In this case, a more refined understanding about the upstream signaling governing the transcriptional activity as well as the downstream effects on proteasome subunits expression is critical for targeting proteasome in the treatment of PD.

Modulation of proteasome phosphorylation

The phosphorylation status of proteasome subunits by PKA, p38 MAPK, and c-Abl has been discussed to modulate the degradation of substrates via proteasome. Administration of rolipram, a specific phosphodiesterase type 4 (PDE4) inhibitor and PKA activator, enhances 26 S proteasome activity, leading to the lower levels of aggregated tau and improved cognitive performance124 (Table 3). Later, a proteasome activity-based probe detects 11 novel compounds that enhance proteasome activity, with the p38 MAPK inhibitor PD169316 being one of the most potent molecules. Furthermore, chemical and genetic inhibition of p38 MAPK, its upstream kinases ASK1 and MKK6, and its downstream target MK2, all remarkably increase proteasome activity and the degradation of ubiquitylated proteins as well as α-synuclein125. These findings may provide a strategy for investigating the complex biology of p38 MAPK to reduce the aberrant protein aggregates under proteotoxic stress.

The activity of c-Abl, a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase, is increased in the SN of PD postmortem brains and animal models, followed by the accumulation of pathological α-synuclein126,127. Several studies have identified α-synuclein and parkin as the substrates of c-Abl, which specifically phosphorylates α-synuclein at Tyr39 and parkin at Tyr143. Currently, the second-generation c-Abl inhibitors Nilotinib and Bafetinib, clinically used in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), have been reported to reduce the accumulation of α-synuclein and reverse the degeneration of nigral dopaminergic neurons in PD animal models128–131. Recently, in a phase 2 randomized clinical trial with 75 patients, 150 and 300 mg doses of Nilotinib administered orally once daily for 12 months appear to be reasonably safe, and the dopamine metabolites in cerebrospinal fluid are significantly increased132,133. Intriguingly, 150 mg but not 300 mg of Nilotinib has shown a reduction in α-synuclein oligomers132 (Table 3). As a consequence, a definitive phase 3 study will be conducted to evaluate the effects of Nilotinib or exploring other c-Abl inhibitors as a potential disease-modifying drug in PD.

Augmentation of proteasome assembly

The transmembrane domain recognition complex (TRC) pathway, which mediates the insertion of tail-anchored proteins, has been implicated to regulate CP assembly. Bag6, a protein in TRC pathway, facilitates the incorporation of β-subunits into α-ring or directly associates with precursor RP subunits, which is involved in the effective degradation of proteins134. In addition, genome-wide functional screening has characterized inactive rhomboid protein 1 (iRhom1), a member of the rhomboid-like family of proteases, as a novel stimulator of proteasome activity135,136. Under ER stress, iRhom1 interacts with 20 S CP assembly chaperones PAC1 and PAC2, affecting their protein stability and dimerization. iRhom1 is induced by ER stressors, such as thapsigargin and tunicamycin, and iRhom1 overexpression has been found to significantly enhance the function of proteasome and mitigate the rough-eye phenotype of mutant Huntingtin136. However, the precise mechanisms by which TRC pathway controls the proteasome CP assembly or iRhom1 regulates the stability of PAC1/PAC2 dimers remain to be established. NRF3, a close homologue of NRF1, directly augments the expression of proteasome maturation protein (POMP), consequently enhancing the degradation of p53 in a ubiquitin-independent manner137. In addition, 19 S base subunit Rpn6 also regulates RP-CP association through the direct binding to α2 subunit. Ectopic expression of Rpn6 is sufficient to enhance proteasome activity and improve resistance to proteotoxic stress138.

PROTAC

PROTAC operates via an event-driven mechanism, which couples a small-molecule binder of a target protein to an E3 ubiquitin ligase via a flexible chemical linker, thereby eliciting ectopic ubiquitylation and eventually leading to the proteasomal degradation139. PROTAC is initially implicated in the recruitment of the androgen receptor to the E3 ubiquitin ligase MDM2, and androgen receptor degradation is proteasome dependent, which is mitigated in cells pretreated with proteasome inhibitor140. More recently, the field of targeting proteins degradation has expanded dramatically, and PROTACs have been found to be more selective than the intrinsic inhibitors141,142. Although p38 MAPK inhibition is implicated to reduce the aberrant protein aggregates under proteotoxic stress, none have displayed the safety and tolerability capable of receiving FDA approval. A recent work has developed p38 MAPK-selective PROTAC based on a single small-molecule binder (foretinib) and E3 ubiquitin ligase von Hippel-Lindau (VHL), which selectively degrades p38α MAPK via proteasome15.

Another work designs and synthesizes an effective tau degrader, namely QC-01-175, in which tau positron emission tomography (PET) tracer 18F-T807 is transformed into pathogenic tau ligand, coupled with a linker to the CRL4CRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. Intriguingly, QC-01-175 preferentially degrades pathological tau, indicating the degrader specificity for disease-relevant forms of tau143 (Table 3). PROTAC may be utilized to develop a functional α-synuclein degrader for the targeted degradation of pathological α-synuclein species in PD where high-quality PET tracers are available. Despite the cytosolic and nuclear proteins can routinely be degraded, the degradation of protein in both the Golgi and ER via PROTAC has not been reported144. Indeed, if a PROTAC is designed to induce the degradation of a protein within one system, then it can be applied more widely in different cell types without genetic modification. Regarding clinical applications, off-target effects and appropriate dosage may be an issue, as saturating doses of PROTAC can antagonize the binding of PROTAC-protein complexes to their ternary partner, a well-described phenomenon known as the hook effect in cell assays145. The likelihood of successful PROTAC development represents a promising strategy to advance our understanding of neurodegenerative disease and translate those insights into targeted therapies.

Conclusions

The recent advances in the field of proteasome remarkably improve our understanding of its biological function, well-organized assembly and dynamic regulation of proteasome homeostasis. Under specific conditions, the dissociation and reassembly of subunits to form different types of proteasome, and the distinct function of singly or doubly capped proteasomes need to be further elucidated. In PD, there exists a large number of mutant or misfolded proteins aggregates, which is a testament to the importance of proteasome for proteostasis and its potential as a therapeutic target. Although a variety of proteasome activation strategies have been identified, no drugs that directly enhance proteasome function are available. The elucidation of other compounds to intensify proteasomal degradation will open up new possibilities for PD treatment based on proteasome modulation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Lingqiang Zhang at National Center for Protein Sciences (Beijing) for his valuable guidance and support for this manuscript.

Author contributions

M.B. concepted and wrote the manuscript; M.B. and Q.J. created and edited the figures; X.D. and X.C. outlined the review and supervised the text; H.J. conceived and edited the final work. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics statement

This paper has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Qingdao University.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771110, 31701020, 81701063, 81801264), Shandong Province Natural Science Foundation (ZR2019ZD31, ZR2020QH125), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1306501), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2020M671991), Key Research and Development Program of Shandong Province (2018GSF118042), Taishan Scholars Construction Project, Innovative Research Team of High-Level Local Universities in Shanghai, Shandong Province Postdoctoral Innovative Project, and Postdoctoral Applied Research Project in Qingdao.

Footnotes

Edited by M. Agostini

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hough R, Pratt G, Rechsteiner M. Purification of two high molecular weight proteases from rabbit reticulocyte lysate. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:8303–8313. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)47564-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waxman L, Fagan JM, Goldberg AL. Demonstration of two distinct high molecular weight proteases in rabbit reticulocytes, one of which degrades ubiquitin conjugates. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:2451–2457. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)61525-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins GA, Goldberg AL. The logic of the 26S proteasome. Cell. 2017;169:792–806. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bard JAM, Bashore C, Dong KC, Martin A. The 26S proteasome utilizes a kinetic gateway to prioritize substrate degradation. Cell. 2019;177:286–298. e215. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu H, Matouschek A. Recognition of client proteins by the proteasome. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2017;46:149–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-070816-033719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahlmann B. Mammalian proteasome subtypes: their diversity in structure and function. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016;591:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie SC, et al. The structure of the PA28-20S proteasome complex from Plasmodium falciparum and implications for proteostasis. Nat. Microbiol. 2019;4:1990–2000. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0524-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo X, Huang X, Chen MJ. Reversible phosphorylation of the 26S proteasome. Protein Cell. 2017;8:255–272. doi: 10.1007/s13238-017-0382-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dantuma NP, Bott LC. The ubiquitin-proteasome system in neurodegenerative diseases: precipitating factor, yet part of the solution. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2014;7:70. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2014.00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKinnon C, et al. Early-onset impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in dopaminergic neurons caused by alpha-synuclein. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020;8:17. doi: 10.1186/s40478-020-0894-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thibaudeau TA, Smith DM. A practical review of proteasome pharmacology. Pharmacol. Rev. 2019;71:170–197. doi: 10.1124/pr.117.015370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mishra R, Upadhyay A, Prajapati VK, Mishra A. Proteasome-mediated proteostasis: novel medicinal and pharmacological strategies for diseases. Med. Res. Rev. 2018;38:1916–1973. doi: 10.1002/med.21502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burslem, G. M. & Crews, C. M. Proteolysis-targeting chimeras as therapeutics and tools for biological discovery. Cell181, 102–114 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Paiva SL, Crews CM. Targeted protein degradation: elements of PROTAC design. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019;50:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2019.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith BE, et al. Differential PROTAC substrate specificity dictated by orientation of recruited E3 ligase. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:131. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08027-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yao L, et al. The proteasome activator REGgamma counteracts immunoproteasome expression and autoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 2019;103:102282. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2019.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li S, et al. Regulation of c-Myc protein stability by proteasome activator REGgamma. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:1000–1011. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashi M, Ishibashi T, Tanaka K, Kasahara M. The mouse genes encoding the third pair of beta-type proteasome subunits regulated reciprocally by IFN-gamma: structural comparison, chromosomal localization, and analysis of the promoter. J. Immunol. 1997;159:2760–2770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murata S, et al. Regulation of CD8+ T cell development by thymus-specific proteasomes. Science. 2007;316:1349–1353. doi: 10.1126/science.1141915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uechi H, Hamazaki J, Murata S. Characterization of the testis-specific proteasome subunit alpha4s in mammals. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:12365–12374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.558866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mannhaupt G, Schnall R, Karpov V, Vetter I, Feldmann H. Rpn4p acts as a transcription factor by binding to PACE, a nonamer box found upstream of 26S proteasomal and other genes in yeast. FEBS Lett. 1999;450:27–34. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00467-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie Y, Varshavsky A. RPN4 is a ligand, substrate, and transcriptional regulator of the 26S proteasome: a negative feedback circuit. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:3056–3061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071022298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shirozu R, Yashiroda H, Murata S. Identification of minimum Rpn4-responsive elements in genes related to proteasome functions. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:933–940. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, Xu H, Ju D, Xie Y. Disruption of Rpn4-induced proteasome expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae reduces cell viability under stressed conditions. Genetics. 2008;180:1945–1953. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.094524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu H, et al. The CCAAT box-binding transcription factor NF-Y regulates basal expression of human proteasome genes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1823:818–825. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vilchez D, et al. Increased proteasome activity in human embryonic stem cells is regulated by PSMD11. Nature. 2012;489:304–308. doi: 10.1038/nature11468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vangala JR, Dudem S, Jain N, Kalivendi SV. Regulation of PSMB5 protein and beta subunits of mammalian proteasome by constitutively activated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3): potential role in bortezomib-mediated anticancer therapy. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:12612–12622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.542829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwak MK, Wakabayashi N, Greenlaw JL, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW. Antioxidants enhance mammalian proteasome expression through the Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;23:8786–8794. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8786-8794.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pickering AM, Linder RA, Zhang H, Forman HJ, Davies KJ. Nrf2-dependent induction of proteasome and Pa28alphabeta regulator are required for adaptation to oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:10021–10031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.277145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radhakrishnan SK, et al. Transcription factor Nrf1 mediates the proteasome recovery pathway after proteasome inhibition in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. 2010;38:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee CS, et al. Loss of nuclear factor E2-related factor 1 in the brain leads to dysregulation of proteasome gene expression and neurodegeneration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:8408–8413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019209108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.James AB, Conway AM, Morris BJ. Regulation of the neuronal proteasome by Zif268 (Egr1) J. Neurosci. 2006;26:1624–1634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4199-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zanelli E, Zhou P, Cao H, Smart MK, David CS. Genomic organization and tissue expression of the mouse proteasome gene Lmp-7. Immunogenetics. 1993;38:400–407. doi: 10.1007/BF00184520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cruz M, Elenich LA, Smolarek TA, Menon AG, Monaco JJ. DNA sequence, chromosomal localization, and tissue expression of the mouse proteasome subunit lmp10 (Psmb10) gene. Genomics. 1997;45:618–622. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rousseau A, Bertolotti A. An evolutionarily conserved pathway controls proteasome homeostasis. Nature. 2016;536:184–189. doi: 10.1038/nature18943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chantranupong L, Sabatini DM. Cell biology: The TORC1 pathway to protein destruction. Nature. 2016;536:155–156. doi: 10.1038/nature18919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, et al. Coordinated regulation of protein synthesis and degradation by mTORC1. Nature. 2014;513:440–443. doi: 10.1038/nature13492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haass C, Kloetzel PM. The Drosophila proteasome undergoes changes in its subunit pattern during development. Exp. Cell Res. 1989;180:243–252. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(89)90228-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pereira ME, Wilk S. Phosphorylation of the multicatalytic proteinase complex from bovine pituitaries by a copurifying cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1990;283:68–74. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90613-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang F, et al. Proteasome function is regulated by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase through phosphorylation of Rpt6. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:22460–22471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702439200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lokireddy S, Kukushkin NV, Goldberg AL. cAMP-induced phosphorylation of 26S proteasomes on Rpn6/PSMD11 enhances their activity and the degradation of misfolded proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E7176–E7185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522332112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.VerPlank JJS, Lokireddy S, Zhao J, Goldberg AL. 26S Proteasomes are rapidly activated by diverse hormones and physiological states that raise cAMP and cause Rpn6 phosphorylation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:4228–4237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1809254116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myeku N, Wang H, Figueiredo-Pereira ME. cAMP stimulates the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway in rat spinal cord neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 2012;527:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Djakovic SN, Schwarz LA, Barylko B, DeMartino GN, Patrick GN. Regulation of the proteasome by neuronal activity and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:26655–26665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.021956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bingol B, et al. Autophosphorylated CaMKIIalpha acts as a scaffold to recruit proteasomes to dendritic spines. Cell. 2010;140:567–578. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamilton AM, et al. Activity-dependent growth of new dendritic spines is regulated by the proteasome. Neuron. 2012;74:1023–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Djakovic SN, et al. Phosphorylation of Rpt6 regulates synaptic strength in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:5126–5131. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4427-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jarome TJ, Kwapis JL, Ruenzel WL, Helmstetter FJ. CaMKII, but not protein kinase A, regulates Rpt6 phosphorylation and proteasome activity during the formation of long-term memories. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2013;7:115. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jarome TJ, Ferrara NC, Kwapis JL, Helmstetter FJ. CaMKII regulates proteasome phosphorylation and activity and promotes memory destabilization following retrieval. Neurobiol. Learn Mem. 2016;128:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guo X, et al. Site-specific proteasome phosphorylation controls cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18:202–212. doi: 10.1038/ncb3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Banerjee S, et al. Ancient drug curcumin impedes 26S proteasome activity by direct inhibition of dual-specificity tyrosine-regulated kinase 2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:8155–8160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1806797115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee SH, Park Y, Yoon SK, Yoon JB. Osmotic stress inhibits proteasome by p38 MAPK-dependent phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:41280–41289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.182188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu X, et al. Interaction between c-Abl and Arg tyrosine kinases and proteasome subunit PSMA7 regulates proteasome degradation. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li D, et al. c-Abl regulates proteasome abundance by controlling the ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation of PSMA7 subunit. Cell Rep. 2015;10:484–496. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wani PS, Suppahia A, Capalla X, Ondracek A, Roelofs J. Phosphorylation of the C-terminal tail of proteasome subunit alpha7 is required for binding of the proteasome quality control factor Ecm29. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:27873. doi: 10.1038/srep27873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crosas B, et al. Ubiquitin chains are remodeled at the proteasome by opposing ubiquitin ligase and deubiquitinating activities. Cell. 2006;127:1401–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Isasa M, et al. Monoubiquitination of RPN10 regulates substrate recruitment to the proteasome. Mol. Cell. 2010;38:733–745. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Besche HC, et al. Autoubiquitination of the 26S proteasome on Rpn13 regulates breakdown of ubiquitin conjugates. EMBO J. 2014;33:1159–1176. doi: 10.1002/embj.201386906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmitt SM, et al. Involvement of ALAD-20S proteasome complexes in ubiquitination and acetylation of proteasomal alpha2 subunits. J. Cell Biochem. 2016;117:144–151. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ullrich O, et al. Poly-ADP ribose polymerase activates nuclear proteasome to degrade oxidatively damaged histones. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:6223–6228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Catalgol B, et al. Chromatin repair after oxidative stress: role of PARP-mediated proteasome activation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;48:673–680. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ullrich O, et al. Turnover of oxidatively damaged nuclear proteins in BV-2 microglial cells is linked to their activation state by poly-ADP-ribose polymerase. FASEB J. 2001;15:1460–1462. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0540fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wells L, Vosseller K, Hart GW. Glycosylation of nucleocytoplasmic proteins: signal transduction and O-GlcNAc. Science. 2001;291:2376–2378. doi: 10.1126/science.1058714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu K, et al. Accumulation of protein O-GlcNAc modification inhibits proteasomes in the brain and coincides with neuronal apoptosis in brain areas with high O-GlcNAc metabolism. J. Neurochem. 2004;89:1044–1055. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang F, et al. O-GlcNAc modification is an endogenous inhibitor of the proteasome. Cell. 2003;115:715–725. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00974-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Overath T, et al. Mapping of O-GlcNAc sites of 20 S proteasome subunits and Hsp90 by a novel biotin-cystamine tag. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:467–477. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.015966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang D, et al. Regulation of acetylation restores proteolytic function of diseased myocardium in mouse and human. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2013;12:3793–3802. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.028332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Swatek KN, Komander D. Ubiquitin modifications. Cell Res. 2016;26:399–422. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ohtake F, et al. Ubiquitin acetylation inhibits polyubiquitin chain elongation. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:192–201. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lehtonen S, Sonninen TM, Wojciechowski S, Goldsteins G, Koistinaho J. Dysfunction of cellular proteostasis in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2019;13:457. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hipp MS, Kasturi P, Hartl FU. The proteostasis network and its decline in ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019;20:421–435. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0101-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Klaips CL, Jayaraj GG, Hartl FU. Pathways of cellular proteostasis in aging and disease. J. Cell Biol. 2018;217:51–63. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201709072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kurtishi A, Rosen B, Patil KS, Alves GW, Moller SG. Cellular proteostasis in neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019;56:3676–3689. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1334-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McNaught KS, Jenner P. Proteasomal function is impaired in substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2001;297:191–194. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McNaught KS, Belizaire R, Isacson O, Jenner P, Olanow CW. Altered proteasomal function in sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2003;179:38–46. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.8050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bedford L, et al. Depletion of 26S proteasomes in mouse brain neurons causes neurodegeneration and Lewy-like inclusions resembling human pale bodies. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:8189–8198. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2218-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wahl C, et al. A comprehensive genetic study of the proteasomal subunit S6 ATPase in German Parkinson’s disease patients. J. Neural Transm. 2008;115:1141–1148. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tashiro Y, et al. Motor neuron-specific disruption of proteasomes, but not autophagy, replicates amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:42984–42994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.417600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tonoki A, et al. Genetic evidence linking age-dependent attenuation of the 26S proteasome with the aging process. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;29:1095–1106. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01227-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pathare GR, et al. The proteasomal subunit Rpn6 is a molecular clamp holding the core and regulatory subcomplexes together. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:149–154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117648108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Polymeropoulos MH, et al. Mutation in the alpha-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson’s disease. Science. 1997;276:2045–2047. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bi M, Kang S, Du X, Jiao Q, Jiang H. Association between SNCA rs356220 polymorphism and Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. Neurosci. Lett. 2020;717:134703. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tran HT, et al. Alpha-synuclein immunotherapy blocks uptake and templated propagation of misfolded alpha-synuclein and neurodegeneration. Cell Rep. 2014;7:2054–2065. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kang UJ, et al. Comparative study of cerebrospinal fluid alpha-synuclein seeding aggregation assays for diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2019;34:536–544. doi: 10.1002/mds.27646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stefanis L, et al. How is alpha-synuclein cleared from the cell? J. Neurochem. 2019;150:577–590. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wong YC, Krainc D. alpha-synuclein toxicity in neurodegeneration: mechanism and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Med. 2017;23:1–13. doi: 10.1038/nm.4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McNaught KS, Perl DP, Brownell AL, Olanow CW. Systemic exposure to proteasome inhibitors causes a progressive model of Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 2004;56:149–162. doi: 10.1002/ana.20186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kadoguchi N, Kimoto H, Yano R, Kato H, Araki T. Failure of acute administration with proteasome inhibitor to provide a model of Parkinson’s disease in mice. Metab. Brain Dis. 2008;23:147–154. doi: 10.1007/s11011-008-9082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kordower JH, et al. Failure of proteasome inhibitor administration to provide a model of Parkinson’s disease in rats and monkeys. Ann. Neurol. 2006;60:264–268. doi: 10.1002/ana.20935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mathur BN, Neely MD, Dyllick-Brenzinger M, Tandon A, Deutch AY. Systemic administration of a proteasome inhibitor does not cause nigrostriatal dopamine degeneration. Brain Res. 2007;1168:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Landau AM, Kouassi E, Siegrist-Johnstone R, Desbarats J. Proteasome inhibitor model of Parkinson’s disease in mice is confounded by neurotoxicity of the ethanol vehicle. Mov. Disord. 2007;22:403–407. doi: 10.1002/mds.21306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hirst SJ, Ferger B. Systemic proteasomal inhibitor exposure enhances dopamine turnover and decreases dopamine levels but does not affect MPTP-induced striatal dopamine depletion in mice. Synapse. 2008;62:85–90. doi: 10.1002/syn.20457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stefanis L, Larsen KE, Rideout HJ, Sulzer D, Greene LA. Expression of A53T mutant but not wild-type alpha-synuclein in PC12 cells induces alterations of the ubiquitin-dependent degradation system, loss of dopamine release, and autophagic cell death. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:9549–9560. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09549.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tanaka Y, et al. Inducible expression of mutant alpha-synuclein decreases proteasome activity and increases sensitivity to mitochondria-dependent apoptosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:919–926. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.9.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Snyder H, et al. Aggregated and monomeric alpha-synuclein bind to the S6’ proteasomal protein and inhibit proteasomal function. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:11753–11759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chen Q, Thorpe J, Keller JN. Alpha-synuclein alters proteasome function, protein synthesis, and stationary phase viability. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:30009–30017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Emmanouilidou E, Stefanis L, Vekrellis K. Cell-produced alpha-synuclein oligomers are targeted to, and impair, the 26S proteasome. Neurobiol. Aging. 2010;31:953–968. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lindersson E, et al. Proteasomal inhibition by alpha-synuclein filaments and oligomers. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:12924–12934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306390200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kim HT, Goldberg AL. The deubiquitinating enzyme Usp14 allosterically inhibits multiple proteasomal activities and ubiquitin-independent proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:9830–9839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.763128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lee BH, et al. Enhancement of proteasome activity by a small-molecule inhibitor of USP14. Nature. 2010;467:179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature09299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Boselli M, et al. An inhibitor of the proteasomal deubiquitinating enzyme USP14 induces tau elimination in cultured neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:19209–19225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.815126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Imai J, Maruya M, Yashiroda H, Yahara I, Tanaka K. The molecular chaperone Hsp90 plays a role in the assembly and maintenance of the 26S proteasome. EMBO J. 2003;22:3557–3567. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Boland B, et al. Promoting the clearance of neurotoxic proteins in neurodegenerative disorders of ageing. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018;17:660–688. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Roe SM, et al. Structural basis for inhibition of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone by the antitumor antibiotics radicicol and geldanamycin. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:260–266. doi: 10.1021/jm980403y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.McLean PJ, Klucken J, Shin Y, Hyman BT. Geldanamycin induces Hsp70 and prevents alpha-synuclein aggregation and toxicity in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;321:665–669. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sittler A, et al. Geldanamycin activates a heat shock response and inhibits huntingtin aggregation in a cell culture model of Huntington’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:1307–1315. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.12.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Auluck PK, Meulener MC, Bonini NM. Mechanisms of suppression of {alpha}-synuclein neurotoxicity by geldanamycin in Drosophila. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:2873–2878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Danzer KM, et al. Heat-shock protein 70 modulates toxic extracellular alpha-synuclein oligomers and rescues trans-synaptic toxicity. FASEB J. 2011;25:326–336. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-164624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chen Y, et al. Hsp90 chaperone inhibitor 17-AAG attenuates Abeta-induced synaptic toxicity and memory impairment. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:2464–2470. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0151-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ho SW, et al. Effects of 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG) in transgenic mouse models of frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 2013;2:24. doi: 10.1186/2047-9158-2-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]