Abstract

Purpose

Galectin-3 (gal-3) is a soluble glycoprotein that has been associated with diverse forms of phagocytosis, including some mediated by the engulfment receptor MerTK. Retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) in vivo uses MerTK (or the related Tyro3) for phagocytosis of shed outer segment fragments during diurnal outer segment renewal. Here, we test if gal-3 plays a role in outer segment renewal in mice and if exogenous gal-3 can promote MerTK-dependent engulfment of isolated outer segment fragments by primary RPE cells in culture.

Methods

We explored age- and strain-matched wild-type (wt), lgals3−/− and mertk−/− mice. Immunofluorescence and immunoblotting characterized gal-3 and RPE/retina protein expression, respectively. Outer segment renewal was investigated by live imaging of phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure on photoreceptor outer segment distal tips and by microscopy of rhodopsin-labeled RPE phagosomes in tissue sections. Retinal function was assessed by recording electroretinograms (ERGs). Phagocytosis assays feeding purified outer segment fragments (POS) were conducted with added recombinant proteins testing unpassaged primary mouse RPE.

Results

Gal-3 localizes to neural retina and RPE in wt mice. The lgals3−/− photoreceptor outer segments display normal diurnal PS exposure at distal tips. The number of rhodopsin-positive phagosomes in wt and lgals3−/− RPE does not differ at peak or trough of diurnal phagocytosis activity. lgals3−/− mice show light responses like wt, and their eyes contain wt levels of retinal and RPE proteins. Unlike purified protein S, recombinant gal-3 fails to promote POS engulfment by mouse primary RPE in culture.

Conclusions

Gal-3 has no essential role in MerTK-dependent outer segment renewal in mice.

Keywords: galectin-3, phagocytosis, knockout, retina, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)

Lifelong renewal of photoreceptor outer segments in the vertebrate retina involves diurnal shedding of distal photoreceptor outer segment tips (POS) and subsequent POS phagocytosis by the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).1,2 Absence or dysregulation in clearance of POS tips by the RPE may lead to rapid or gradual degeneration of the retina.3–5 The molecular mechanisms of outer segment renewal are complex and continue to be investigated. Studies exploring mutant mice and rats have shown that exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS) on outer segment tips triggers ligation of two apical surface receptors of the RPE, the integrin αvβ5, and the receptor tyrosine kinase Mer (MerTK), respectively.5–8 MerTK belongs to the TAM family of highly related and functionally similar tyrosine kinase receptors,9 and in mice Tyro3 can fulfill MerTK's role in RPE phagocytosis.10 PS on outer segment tips engages these RPE receptors via soluble bridge proteins with PS- and receptor-binding domains that localize to the subretinal space. Mice lacking the αvβ5 ligand MFG-E8 show the same phagocytosis defect as mice lacking αvβ5 integrin, a loss of the diurnal phagocytic burst.11 Double knockout mice lacking two well-characterized ligands for the TAM receptor family, Gas6 and protein S, show the same severe form of retinal degeneration as mertk−/− mice.12 Early onset retinal degeneration due to constitutive lack of MerTK progresses at similar rate in mutant mice and rats.13 Moreover, human patients with inherited mutations in the mertk gene develop severe forms of retinitis pigmentosa.14,15 Thus, all available evidence suggests that the molecular mechanisms of RPE phagocytosis are highly conserved and that studies on mutant mice have predictive value for our understanding of human retinal physiology and diseases.

Galectin-3 (gal-3) is a member of the galectin family of soluble lectins that share a conserved carbohydrate recognition domain that specifically binds β-galactosides.16,17 Galectins are found in virtually all tissue types in mammals and are present intracellularly and in extracellular matrices.18 Macrophages from lgals3−/− mice show reduced rates of phagocytosis when challenged with bacteria or apoptotic cells, and mixed cell culture experiments suggest that wild-type (wt) macrophages phagocytose faster due to intracellular gal-3.19 In contrast, microglia secrete gal-3 in response to phagocytic stimuli, and adding exogenous gal-3 promotes phagocytosis by microglia cells.20 In the healthy retina, gal-3 has been reported in Müller glia of rats and pigs.21,22 Mice lacking gal-3 (lgals3−/−) show reduced neuroinflammation and decreased retinal damage when rendered diabetic as compared to diabetic wt mice.23 RPE cells in culture express gal-3 where it is involved in epithelial to mesenchymal transition mechanisms and increases RPE migratory activity.24,25 Adding purified gal-3-fusion protein promotes MerTK-dependent phagocytosis of experimental cellular debris by immortalized macrophages and RPE cells.26 Here, we present experiments performed to directly test if gal-3 is important for outer segment renewal and retinal homeostasis in vivo. While exploring lgals3−/− mice, we failed to find differences to wt mice in these processes. Moreover, adding exogenous gal-3 to wt primary RPE cells did not affect POS binding or MerTK-dependent POS engulfment.

Materials and Methods

Reagents were from Millipore-Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) or ThermoFisher (Waltham, MA, USA) unless indicated.

Animals

Mice were housed and bred in the Fordham University animal facility. All procedures were pre-approved by Fordham University's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and adhered to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Mice had access to standard diet and water ad libitum and were kept in strict 12-hour light/dark cycles. All mice studied were in 129T2/SvEms/J genetic background. Wt, lgals3−/−, and mertk−/− strains were originally from Jackson Laboratories, and mutant strains were routinely backcrossed to wt. Mice were tested and found negative for the rd8 mutation.27 Mixed sex cohorts were studied as outer segment renewal does not differ based on sex.28 For tissue harvest, mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation followed by immediate eyeball enucleation.

Retinal Section Preparation, Immunofluorescence Staining, Imaging, and RPE Phagosome Quantification

Cornea and lens were dissected from freshly enucleated eyes. Eyecups were immersion fixed in either 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature (for gal-3 staining) or in Davidson's fixative (33% ethanol, 22% formaldehyde, and 11.5% acetic acid) overnight at 4°C (for rhodopsin staining), embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 7-µm thick sections. Sections were deparaffinized and RPE pigment was bleached by incubation for 10 minutes in 1% sodium borohydride solution. Sections were stained with either gal-3 antibody (R&D Systems, #AF1197) or rhodopsin antibody B6-30,29 AlexaFluor-conjugated secondary antibodies, and DAPI nuclear stain. A Leica TSP5 confocal microscopy system was used for image acquisition. Images were recompiled in Adobe Photoshop CS3.

Phagosome staining and quantification was performed by strictly following a previously published step-by-step protocol.30 In brief, x-z image stacks of exactly 5-µm thickness of stretches of central retina were acquired using high intensity settings that deliberately overexposes labeling in intact outer segments but reveals rhodopsin-positive phagosomes in the RPE. Maximal projections of such image stacks were opened in ImageJ to count phagosomes as defined as rhodopsin-positive inclusions in the RPE of at least 0.5 µm diameter. For each sample type, five eyes from five mice were sectioned. Phagosome counts obtained from six stained sections of each individual eye were averaged to yield a single data point.

Immunofluorescence Staining of RPE Flat-Mounts

Cornea, lens, and retina were dissected from freshly enucleated eyes. Resulting eyecups were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature and incubated in 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1% BSA in PBS for 30 minutes before flattening by making radial cuts, labeling with gal-3 antibody, fluorescent phalloidin, and DAPI nuclear stain and mounting, and microscopy as described for sections.

Live Imaging of PS Biosensor

Live PS staining was performed on freshly dissected retinas as previously described.8 Briefly, intact retinas were dissected immediately after eye enucleation, transferred to a microscopy slide photoreceptor side up, and immersed in PS biosensor (pSIVA; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA; #NBP2-29382). PS signals were imaged promptly using a Leica TSP5 laser scanning confocal microscope.

Electroretinography

Standard scotopic and photopic electroretinographies (ERGs) were performed as described previously.31 In brief, 2.5-month-old wt and lgals3−/− mice were dark-adapted overnight before intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine for anesthesia followed by topical anesthesia and pupil dilation. Responses were recorded and averaged using a UTAS 2000 ERG system (LKC, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Scotopic rod ERGs were recorded from white flash stimuli of 1.5 cd-s/m2 attenuated to yield intensities from −1.8 to 0.2 log cd-s/m2. For photopic ERGs, mice were exposed to 20 cd/m2 white light before full flash stimulus. The a-wave amplitudes were measured from the baseline to the trough; b-wave amplitudes were measured from the a-wave trough to the positive peak. At least four responses were averaged from each animal for each stimulus.

Tissue Lysis, SDS-PAGE, and Immunoblotting

Whole eyes without cornea and lens, dissected neural retina, or dissected posterior eyecups enriched in RPE and choroid were lysed in ice-cold HNTG lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, NaCl 150 mM, 10% glycerol, and 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail. Cleared lysates were subjected to standard SDS-PAGE, immunoblotting, and signal detection on autoradiography film using enhanced chemiluminescence (Lightning Plus; Perkin Elmer, Shelton, CT, USA). Primary antibodies were to: rhodopsin B630, blue opsin (Millipore-Sigma; #5407), red/green opsin (Millipore-Sigma; #5405), GAPDH (Genetex, Irvine, CA, USA; #GTX100118), gal-3, MerTK (R&D Systems; #AF591), RPE65 (Genetex; #GTX103472), and anti-PSD95 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA; #S4507). Image-J software was used to quantify relative densities of bands.

Primary RPE Cell Culture

Primary RPE cell cultures were prepared from 3- to 6-day-old mice as previously described.32 In brief, cornea, lens, and retina were dissected. Eyecups were incubated in 2 mg/mL trypsin in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) at 37°C for 33 minutes followed by manual collection of RPE sheets. RPE sheets were re-trypsinized for 1 minutes, pelleted, resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% N1 supplement, and seeded at a density of 2 eyes per 96-well. Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 to be used 3 to 4 days after seeding.

RPE Cell Culture Phagocytosis Assay

POS were isolated from fresh porcine eyes obtained from a local slaughterhouse according to published protocols.33 Purified POS were covalently labeled with 0.01 mg/mL Texas Red-X (mixed isomers) for 1 hour at room temperature directly before use in phagocytosis assays. Recombinant mouse MFG-E8 (R&D Systems; #2805-MF/CF) at 1.25 µg/mL, human protein S (HYPHEN Biomed, France; #PP012A) at 2 µg/mL, and/or mouse gal-3 (R&D Systems; #1197-GA/CF) at select concentrations were co-incubated with labeled POS at a concentration of 10 particles per cell in serum-free DMEM at 37°C for 1.5 hours. After incubation, surface-bound POS only were immunolabeled.34 In brief, washed cells were fixed in 4% PFA in PBS for 10 minutes at room temperature. Surface-bound POS were counterstained with rhodopsin antibody B6-30, as described previously.35 Bound and internalized POS were quantified from confocal x-z stack projections using ImageJ software.

Statistical Analysis

All animal experiments compared cohorts of at least five mice. All in vitro assays were conducted at least three times independently. For analyses of groups, means and standard deviation were calculated for each sample population. Two groups were compared using the Student's two-tailed t-test. Three or more groups were compared using 1-way or 2-way ANOVA as appropriate, with Tukey's post hoc test for comparison of two groups within multiple groups. P values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant for all experiments.

Results

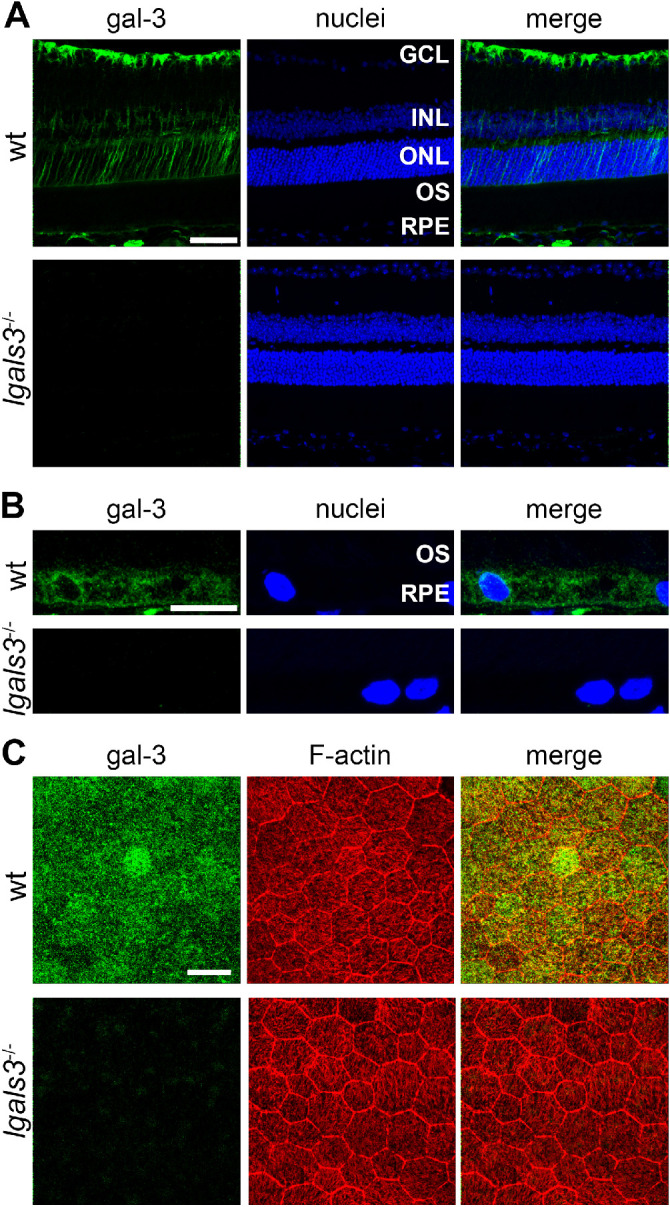

Gal-3 Localizes to the RPE in Mouse Retina In Situ

Gal-3 localization in mouse retina has not been reported to date. Direct comparison of gal-3 immunofluorescence in retinal sections from wt and lgals3−/− mice shows specific gal-3 labeling in inner retina resembling Müller glia in appearance (as expected from previous reports in other species)21,22 as well as in the choroid and the RPE (Figs. 1A, 1B). Imaging of the same antibody staining in RPE flat-mount samples showed gal-3 throughout the RPE's cytoplasm in wt samples with little background in lgals3−/− samples (Fig. 1C). F-actin counterstain in these experiments reveals lgals3−/− RPE cell shape or size like wt (see Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Gal-3 localizes to the neural retina and RPE in mice. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of gal-3 of retinal sections from wt and lgals3−/− mice shows localization to the inner retina (and they are based on the appearance most likely to be mainly Müller cells), RPE, and choroid. Images are representative maximal projections. Green: gal-3; and blue: nuclei counterstain. GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OS, photoreceptor outer segment layer. Scale bar = 50 µm. (B) Magnified fields of stained sections as in A focusing on the RPE. Scale bar = 10 µm. (C) Immunofluorescence staining of RPE whole mount preparations of wt and lgals3−/− mice show gal-3 in the RPE. Images are representative maximal projections comprising the entire RPE. Green: gal-3; red: F-actin; blue: nuclei counterstain. Scale bar = 25 µm.

Gal-3 is Not Required for Diurnal PS Exposure by Outer Segments or RPE Phagocytosis in Mice

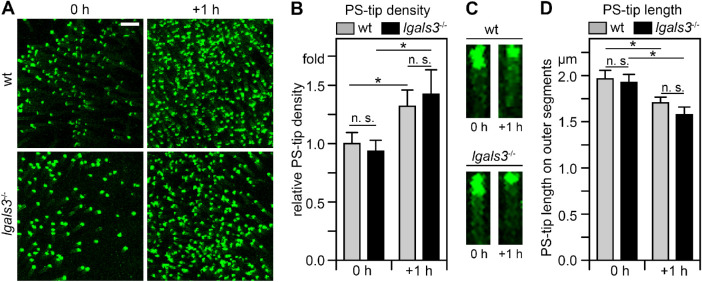

To assess if lack of gal-3 affects photoreceptor PS “eat me” signal exposure during outer segment renewal, we quantified PS exposure by photoreceptor outer segment tips in lgals3−/− mice euthanized immediately following light onset or 1 hour later. Following side-by-side live imaging of PS biosensor of wt and lgals3−/− retina flat-mounts we compared the frequency of outer segments exposing PS and the length of PS label on individual outer segments. Figure 2 shows representative images and quantification averages of these experiments. Like in wt retina, here and as expected from our prior work,8 PS-exposing outer segments in lgals3−/− retina increased in frequency within 1 hour after light onset (see Figs. 2A, 2B), and individual outer segments showed extended PS exposure at light onset compared to 1 hour later (see Figs. 2A, 2C).

Figure 2.

Diurnal PS exposure at photoreceptor outer segment tips is indistinguishable between wt and lgals3−/− mice. (A) Representative PS-biosensor live imaging of freshly dissected neural retina whole mount of wt and lgals3−/− mice collected within 5 minutes of light onset (0 hours) and 1 hour later (+ 1 hour). Images are maximal projections. Scale bar = 10 µm. (B) Quantification of the frequency of outer segments exposing PS in wt and lgals3−/− mice of samples as in A. Values are normalized to the frequency of outer segments exposing PS in wt mice at light onset. (C) Length of the tip of outer segments exposing PS in wt and lgals3−/− mice at time points as in A. Images are representative maximal projections of PS-biosensor labeling of outer segments in whole mount preparations imaged at high magnification. Scale bar = 2 µm. (D) Quantification of the length of PS-exposing tips of outer segments from images as in C. Bars in B and C show mean ± s. e. m., n = 4; 2-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test; *p < 0.05; n. s., not significant.

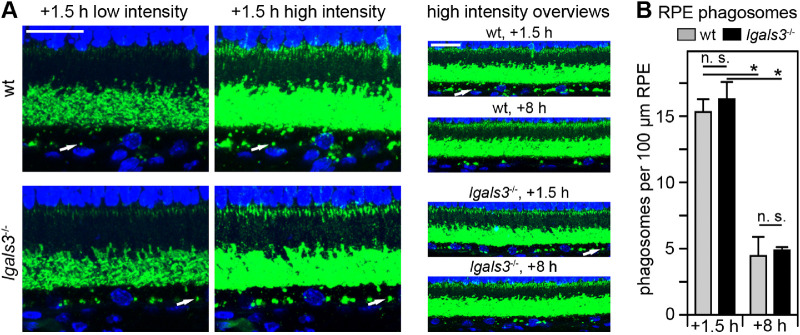

Next, we assessed RPE phagocytosis in lgals3−/− retina. To this end, we used a standardized method we published previously30 to quantify the number of rhodopsin positive phagosomes in sectioned RPE of wt and lgals3−/− mice euthanized at 1.5 hours after light onset, a time when phagosome content of RPE is at its peak, and at 8 hours after light onset, a time when most phagosomes have been degraded.5 Figure 3 illustrates the phagosome detection approach and shows that the phagosome content of wt and lgals3−/− RPE is the same at both time points implying that RPE cells lacking gal-3 are fully active in POS engulfment and digestion.

Figure 3.

RPE phagosome loads are similar between wt and lgals3−/− mice. (A) Representative fields show maximum projections of 5-µm thick x-z stacks of wt and lgals3−/− retina sections collected at 1.5 and 8 hours after light onset as indicated and stained for rhodopsin (green) and nuclei (blue). Low intensity images (left column) are shown to compare rhodopsin labeling in intact outer segments, which was comparable between wt and lgals3−/− retina. High intensity imaging of the same fields (center column) is shown to detect rhodopsin-positive phagosomes in the RPE. These images are deliberately overexposed to visualize phagosomes. Overview images of longer stretches of the same sections and of equivalent sections from tissues harvested at 8 hours after light onset are shown in the right column. Arrows indicate one (and the same) individual phagosome in all three types of images in wt and lgals3−/− tissue, respectively. Scale bars = 20 µm. (B) Phagosome quantification was performed by counting rhodopsin-positive inclusions of 0.5 µm or larger in diameter in the RPE from experiments and long stretch, high intensity images as shown in the right column of A. Bars show number of phagosomes per length of wt and lgals3−/− RPE; mean ± s. d., n = 5; 2-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test; *p < 0.05; n. s., not significant.

Lgals3 −/− Mice Have Normal Light Responses and Photoreceptor Marker Proteins

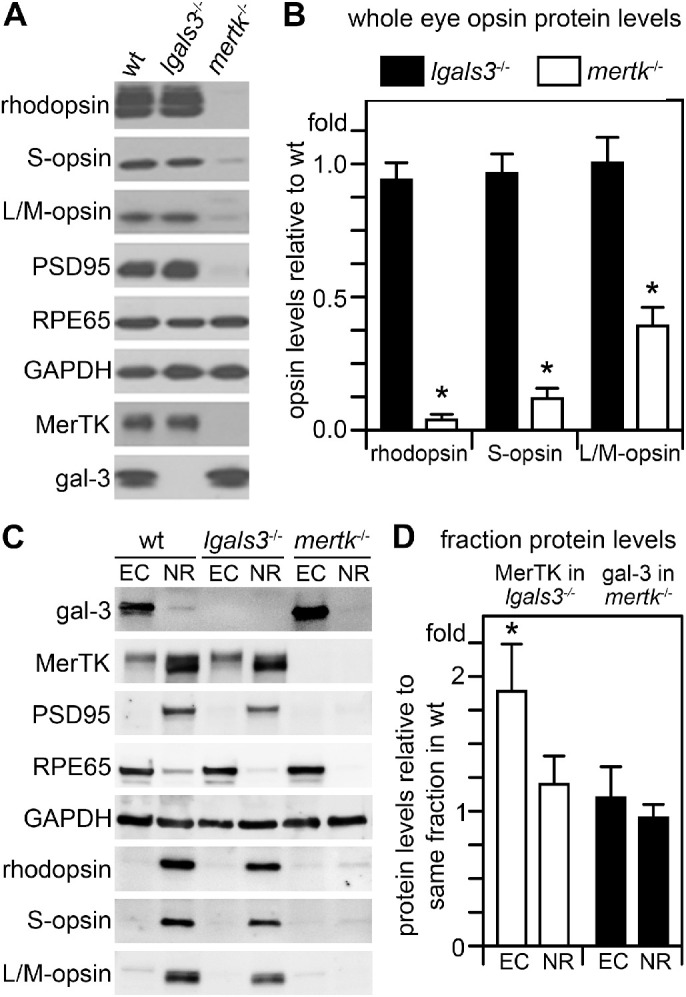

We next performed scotopic and photopic ERGs on wt and lgals3−/− mice at 2.5 months of age. Analysis of a- and b-wave amplitudes of both photopic and scotopic recordings revealed no difference between wt and lgals3−/− responses (Figs. 4A, 4B). These results suggest normal rod and cone photoreceptor dependent light responses in the absence of gal-3. Moreover, we found no difference in photoreceptor opsins or other photoreceptor or RPE marker proteins comparing 3-month-old lgals3−/− and wt eyes (Fig. 5). In this experiment, we included analysis of 3-month-old mertk−/− eyes as positive control for retinal degeneration. Retinal degeneration in mertk−/− mice progresses rapidly from approximately PN25, such that all outer segments and indeed the majority of photoreceptor cells are lost by 3 months of age leading to diminished levels of opsin and synapse proteins.13 To quantify opsins, we tested whole eye tissues without cornea and lens to minimize variability due to manual neural retina dissection, which involves some damage to the outer segments. As expected, the mertk−/− samples showed dramatically reduced content of rhodopsin and cone opsins as well as of the neuronal synapse marker PSD95 (see Fig. 5A). Comparing the ratios of opsin levels relative to wt between lgals3−/− and mertk−/− tissues quantified these observations (see Fig. 5B). The side-by-side tissue comparisons showed no difference in RPE marker RPE65 among the three different mouse strains (see Fig. 5A). Next, we compared dissected neural retina and posterior eyecups enriched in RPE and choroid of the three mouse strains (see Fig. 5C). We found that gal-3 content was higher in eyecups than in neural retina (by about 7-fold), but it should be noted that each tissue fraction represents a mix of several cell types (e.g. Müller cells are not an abundant cell type in the neural retina). Müller cell gal-3 (easily observed by microscopy) is thus diluted in the neural retina fraction to which Müller cell proteins make only a minor contribution. Notably, mertk−/− eyecups show higher gal-3 levels than wt eyecups suggesting that gal-3 in the posterior eye is upregulated during retinal degeneration (see Figs. 5C, 5D). In contrast, lgals3−/− eye tissue fractions have normal levels of MerTK (see Figs. 5C, 5D). Altogether, our experiments do not support any abnormalities in retinal or RPE markers or degeneration in lgals3−/− mouse retina.

Figure 4.

Photopic and scotopic light responses of 2.5-month - old lgals3−/− mice are normal. (A) Bars show quantification of maximal photopic ERG a- and b-wave amplitudes, as indicated. Gray bars, wt mice; black bars, lgals3−/− mice; mean ± s. e. m., n = 8; Student's t-test; p > 0.05; n. s., not significantly different. (B) Dot plots show quantification of maximal scotopic ERG a- and b-wave amplitudes recorded with increasing white light flash intensities as indicated. Open circles, wt mice; black circles, lgals3−/− mice. Lines indicate averages ± s. e. m., n = 9. No significant differences between wt and lgals3−/− mice were found by 2-way ANOVA regardless of light intensity.

Figure 5.

Unlike degenerating mertk−/− retina, lgals3−/− retina has wt levels of RPE and photoreceptor marker proteins, but gal-3 is elevated in posterior eyecups of mertk−/− mice with retinal degeneration. (A) Representative comparative immunoblots of detergent lysates representing equal fractions of whole eyes without lens with intact retinas of 3-month-old wt, lgals3−/−, and mertk−/− mice probed for photoreceptor and RPE marker proteins and housekeeping proteins GAPDH as loading control as indicated. Probes for gal-3 and MerTK confirmed mouse genotypes. (B) Bars show quantification of average rhodopsin and cone opsin content in lgals3−/− (black bars) and mertk−/− eyes (white bars) normalized to content in wt eyes as indicated. (C) Representative immunoblots of posterior eyecups (ECs) and neural retina (NR) eye fractions probed for proteins as indicated. Probes for RPE65, PSD95, and opsins confirmed fraction enrichment with minor contamination of adjacent tissue as expected of manual dissections. GAPDH indicated protein load. (D) Bars show quantification of gal-3 in mertk−/− eye fractions (white bars) and of MerTK in lgals3−/− eye fractions (black bars), respectively. Bars in B and D show averages ± s. e. m., n = 4; Student's t-test; *p < 0.05. There was no difference in levels of opsins, MerTK or any other marker tested between lgals3−/− and wt tissue. As expected, mertk−/− eyes with ongoing retinal degeneration contained dramatically reduced levels of opsins and other neural retina markers but normal levels of RPE marker RPE65 and elevated levels of gal-3.

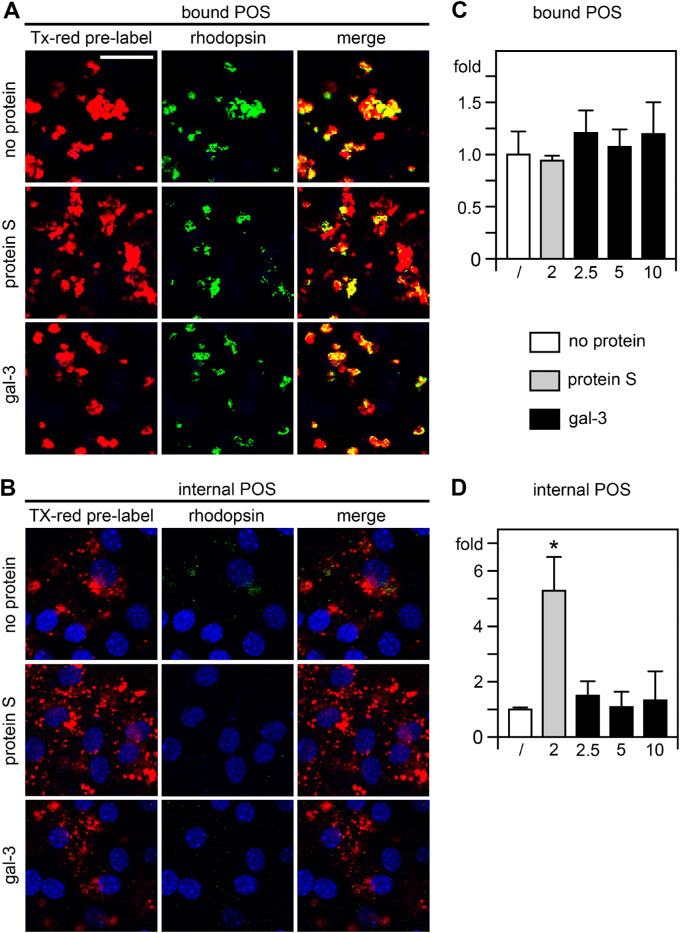

Gal-3 is Not Sufficient for POS Engulfment by Primary Cultures of RPE

Lack of gal-3 may not impact outer segment turnover or retinal function in global, constitutive lgals3−/− mice due to redundancy or due to compensation mechanisms. We therefore wondered if gal-3 might be able to promote POS phagocytosis by RPE cells in culture even if it is not required in vivo. To test this hypothesis, we tested effects of exogenous gal-3 on POS uptake by unpassaged wt mouse RPE cells in primary culture.

To distinguish internalized from surface-bound POS, we challenged the cells with Texas Red prelabeled POS followed by selective immunolabeling of bound POS only using rhodopsin antibodies and AlexaFluor488-conjugated secondary antibodies. Imaging red POS signals thus detected bound and internalized POS, whereas only bound POS were detected by green POS signal imaging. Separating confocal z-stacks yielded images showing bound and internalized POS in Figures 6A and 6B, respectively. Nuclei counterstain further supported the localization of internalized, Texas Red-only POS in the RPE cells’ cytoplasm (see Fig. 6B). All samples received POS in serum-free medium supplemented with MFG-E8, the ligand for the POS binding receptor αvβ5 integrin.11 As expected, cells that were challenged with POS/MFG-E8 alone bound but did not engulf POS, as evident from the extensive double labeling of green and red POS imaging (see Fig. 6A, top row shows bound POS, Fig. 6B, top row shows internalized POS in the same field). Adding purified Protein S, one of the established ligands for the MerTK engulfment receptor,36 promoted robust POS internalization with abundant cytoplasmic Texas Red-only POS (see Fig. 6B, center row) confirming that phagocytosis by the wt primary RPE cell preparations we tested is MerTK-dependent. In contrast, addition of gal-3 did not promote POS internalization with minimal internalized POS like cells that received POS with MFG-E8 only (see Figs. 6A, 6B bottom rows). This was not due to failure to bind POS: comparison of bound POS revealed no difference among any of the samples suggesting that neither protein S nor gal-3 promote POS binding and confirming that availability of POS for surface binding was not limiting in the assay (see Fig. 6C). Quantification of internalized POS relative to no addition of engulfment ligand confirmed the microscopic observations (see Fig. 6B). Protein S robustly increased POS internalization (see Fig. 6D). In contrast, exogenous gal-3 did not promote POS engulfment by primary wt mouse RPE cells at any of the concentrations tested (see Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

Purified gal-3 does not promote binding or engulfment of outer segment particles by primary mouse RPE cells. Unpassaged polarized mouse RPE cells were fed with Texas Red-labeled POS in medium with no additional protein (A, B, top rows), added protein S (A, B, center rows), or added gal-3 (A, B, bottom rows). All samples received integrin ligand MFG-E8 to promote POS binding. Bound or engulfed POS material is shown in red. Bound particles only were counterstained post-fixation with rhodopsin antibody (green). Nuclei were counterstained in blue. Apically bound particles (green and red) are shown in apical maximal projections in A. Engulfed particles of the same fields as in A are shown in B in maximal projections of the center of the RPE as indicated by the RPE nuclei. Scale bar = 25 µm. (C, D) Bar graphs shows quantification of bound POS C and internalized POS D, respectively, relative to samples with only MFG-E8 added, which was set as 1. The bona fide MerTK ligand Protein S was added at 2 µg/mL (gray bars) to serve as positive control for MerTK-dependent POS internalization. Gal-3 was added at 2.5, 5, or 10 µg/mL (black bars, concentrations as indicated). Bars show mean ± s. e. m., n = 4 independent assays; 1-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test; *p < 0.05. Differences between samples fed with MFG-E8 only or with MFG-E8 plus gal-3 at any concentration tested were not significant for either bound or internalized POS.

Discussion

RPE cells in the healthy mouse retina express gal-3 protein, and gal-3 localizes to the neural retina, most prominently to Müller glia, as shown earlier for other mammalian species. The physiological function of gal-3 in Müller cells remains to be explored, but its upregulation in constant light-induced retinal damage is suggestive of a cytoprotective role.22 Our study focused on gal-3 in the RPE. Extensive experiments exploring mice lacking gal-3 and primary RPE cells revealed that gal-3 is neither required nor sufficient for POS phagocytosis by mouse RPE. We speculate that the elevated levels of gal-3 in eyecups of mertk−/− mice at an age of active retinal degeneration may be cytoprotective for the RPE as well, with underlying molecular mechanisms to be identified.

We scrutinized the process of photoreceptor outer segment renewal in lgals3−/− mice examining in separate approaches the diurnal dynamics of PS exposure at distal tips of photoreceptor outer segments and the diurnal change in phagosome numbers in the RPE. Both experimental approaches are highly quantitative, and together they agree that lack of gal-3 in mice has no effect on outer segment renewal. Motivated by prior reports that gal-3 can physically and functionally interact with the engulfment receptor MerTK, we further measured retinal light responses and marker protein expression to compare the retinal phenotype of lgals3−/− and mertk−/− mice. Strikingly, at an age of 2.5 months at which mertk−/− mice have drastically reduced light responses and severely degenerated retinas,13 lgals3−/− and wt mouse light responses and retinal protein expression are indistinguishable. Altogether, outer segment renewal and retinal function in vivo in mice do not require gal-3. Prior studies on macrophages and microglia also explored murine cell models and the thus far sole in vivo demonstration of gal-3's role in phagocytosis is for inflammatory phagocytosis comparing macrophages of wt and lgals3−/− mice.19,20 Thus, our negative results are not caused by species differences. It should also be noted that all studies on outer segment renewal or RPE phagocytosis to date show complete conservation in molecular mechanism used by the RPE of mouse, rat, and human origin.

We complemented our in vivo studies with phagocytosis assays challenging primary, unpassaged mouse RPE cells with purified POS particles that expose the “eat me” signal PS like distal outer segment tips at light onset.8 In these assays, ligation of MerTK by one of its established ligands protein S was sufficient to promote POS engulfment. In contrast, adding exogenous gal-3 did not change the amount of bound or internalized POS. We conclude that gal-3 is not sufficient to promote binding or engulfment of POS by RPE cells. A previous study suggested that interaction of an extracellular GST-Gal-3 fusion protein with MerTK promotes phagocytosis by immortalized d407 RPE and macrophage cell lines.26 However, in this study, experimental cell debris rather than purified POS was used to challenge cells, which may explain the discrepancy to our results.

The molecular mechanism of RPE phagocytosis is related to efferocytosis mechanisms for PS-positive debris clearance used by many cell types including fibroblasts and professional phagocytes, such as macrophages. RPE cells are professional phagocytes based on their high capacity to engulf POS particles, and they are the only phagocytes in the body that are immortal and phagocytose daily for life. However, all available evidence suggests that RPE cells express and use a phagocytic machinery with less redundancies than the highly versatile machinery of macrophages.37 For instance, macrophages express several engulfment receptors that can promote efferocytosis of PS-exposing debris, whereas RPE cells depend on MerTK/Tyro3 receptors and experimental expression of the non-TAM PS receptor BAI-1 cannot compensate for loss of MerTK.38 Our results document that, similarly, gal-3 cannot promote POS clearance phagocytosis by RPE cells despite its roles in phagocytosis by other phagocytes.

Our results do not support an essential role for gal-3 in routine outer segment turnover, and our experiments did not find a functional defect in the retina of mice lacking gal-3. The question of the physiological role of gal-3 in the RPE (and other retinal cells) thus remains to be answered. It is conceivable that gal-3 participates in processes activated under stress or disease conditions. Accumulation of gal-3 in rat retina upon light damage22 as well as in posterior eyecups in mertk−/− mice as we showed here are very intriguing observations in support of gal-3 changes in expression and function in retinal degeneration. Moreover, gal-3 plays a role in RPE dedifferentiation and migration, changes that are associated with several retinal diseases.24,25 Experiments beyond the scope of the current study will be needed to further define the role of gal-3 in retinal pathophysiology.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stephen Crowley for excellent technical assistance.

Supported by the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health grant number R01EY026215. S.C.F. holds the Kim B. and Stephen E. Bepler Professorship in Biology.

Disclosure: N.J. Esposito, None; F. Mazzoni, None; J.A. Vargas, None; S.C. Finnemann, None

References

- 1. Young RW. The renewal of photoreceptor cell outer segments. J Cell Biol. 1967; 33: 61–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Young RW, Bok D.. Participation of the retinal pigment epithelium in the rod outer segment renewal process. J Cell Biol. 1969; 42: 392–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dowling JE, Sidman RL.. Inherited retinal dystrophy of the rat. J Cell Biol. 1962; 14: 73–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mullen RJ, LaVail MM.. Inherited retinal dystrophy: primary defect in pigment epithelium determined with experimental rat chimeras. Science. 1976; 192: 799–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nandrot EF, Kim Y, Brodie SE, Huang X, Sheppard D, Finnemann SC.. Loss of synchronized retinal phagocytosis and age-related blindness in mice lacking αvβ5 integrin. J Exp Med. 2004; 200: 1539–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. D'Cruz PM, Yasumura D, Weir J, et al.. Mutation of the receptor tyrosine kinase gene mertk in the retinal dystrophic RCS rat. Hum Mol Genet. 2000; 9: 645–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nandrot E, Dufour EM, Provost AC, et al.. Homozygous deletion in the coding sequence of the c-mer gene in RCS rats unravels general mechanisms of physiological cell adhesion and apoptosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2000; 7: 586–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ruggiero L, Connor MP, Chen J, Langen R, Finnemann SC.. Diurnal, localized exposure of phosphatidylserine by rod outer segment tips in wild-type but not Itgb5−/− or Mfge8−/− mouse retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012; 109: 8145–8148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lemke G, Burstyn-Cohen T.. TAM receptors and the clearance of apoptotic cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010; 1209: 23–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vollrath D, Yasumura D, Benchorin G, et al.. Tyro3 modulates mertk-associated retinal degeneration. PLoS Genetics. 2015; 11: e1005723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nandrot EF, Anand M, Almeida D, Atabai K, Sheppard D, Finnemann SC.. Essential role for MFG-E8 as ligand for αvβ5 integrin in diurnal retinal phagocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007; 104: 12005–12010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burstyn-Cohen T, Lew ED, Traves PG, Burrola PG, Hash JC, Lemke G.. Genetic dissection of TAM receptor-ligand interaction in retinal pigment epithelial cell phagocytosis. Neuron. 2012; 76: 1123–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Duncan JL, LaVail MM, Yasumura D, et al.. An RCS-like retinal dystrophy phenotype in mer knockout mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003; 44: 826–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gal A, Li Y, Thompson DA, et al.. Mutations in MERTK, the human orthologue of the RCS rat retinal dystrophy gene, cause retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet. 2000; 26: 270–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Parinot C, Nandrot EF.. A comprehensive review of mutations in the MERTK proto-oncogene. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016; 854: 259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barondes SH, Castronovo V, Cooper DN, et al.. Galectins: a family of animal beta-galactoside-binding lectins. Cell. 1994; 76: 597–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barondes SH, Cooper DN, Gitt MA, Leffler H. Galectins. Structure and function of a large family of animal lectins. J Biol Chem. 1994; 269: 20807–20810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hughes RC. Secretion of the galectin family of mammalian carbohydrate-binding proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999; 1473: 172–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sano H, Hsu DK, Apgar JR, et al.. Critical role of galectin-3 in phagocytosis by macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2003; 112: 389–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nomura K, Vilalta A, Allendorf DH, Hornik TC, Brown GC.. Activated microglia desialylate and phagocytose cells via neuraminidase, galectin-3, and Mer tyrosine kinase. J Immunol. 2017; 198: 4792–4801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim J, Moon C, Ahn M, Joo HG, Jin JK, Shin T.. Immunohistochemical localization of galectin-3 in the pig retina during postnatal development. Mol Vis. 2009; 15: 1971–1976. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Uehara F, Ohba N, Ozawa M.. Isolation and characterization of galectins in the mammalian retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001; 42: 2164–2172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mendonca HR, Carvalho JNA, Abreu CA, et al.. Lack of galectin-3 attenuates neuroinflammation and protects the retina and optic nerve of diabetic mice. Brain Res. 2018; 1700: 126–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Priglinger CS, Szober CM, Priglinger SG, et al.. Galectin-3 induces clustering of CD147 and integrin β1 transmembrane glycoprotein receptors on the RPE cell surface. PLoS One. 2013; 8: e70011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Priglinger CS, Obermann J, Szober CM, et al.. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of RPE cells in vitro confers increased β1,6-N-glycosylation and increased susceptibility to galectin-3 binding. PLoS One. 2016; 11: e0146887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Caberoy NB, Alvarado G, Bigcas JL, Li W.. Galectin-3 is a new MerTK-specific eat-me signal. J Cell Physiol. 2012; 227: 401–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mattapallil MJ, Wawrousek EF, Chan CC, et al.. The Rd8 mutation of the Crb1 gene is present in vendor lines of C57BL/6N mice and embryonic stem cells, and confounds ocular induced mutant phenotypes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53: 2921–2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mazzoni F, Tombo T, Finnemann SC.. No difference between age-matched male and female C57BL/6J mice in photopic and scotopic electroretinogram a- and b-wave amplitudes or in peak diurnal outer segment phagocytosis by the retinal pigment epithelium. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019; 1185: 507–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Adamus G, Zam ZS, Arendt A, Palczewski K, McDowell JH, Hargrave PA.. Anti-rhodopsin monoclonal antibodies of defined specificity: characterization and application. Vision Res. 1991; 31: 17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sethna S, Finnemann SC.. Analysis of photoreceptor rod outer segment phagocytosis by RPE cells in situ. Methods Mol Biol. 2013; 935: 245–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yu CC, Nandrot EF, Dun Y, Finnemann SC.. Dietary antioxidants prevent age-related retinal pigment epithelium actin damage and blindness in mice lacking αvβ5 integrin. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012; 52: 660–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Finnemann SC. Focal adhesion kinase signaling promotes phagocytosis of integrin-bound photoreceptors. EMBO J. 2003; 22: 4143–4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Parinot C, Rieu Q, Chatagnon J, Finnemann SC, Nandrot EF.. Large-scale purification of porcine or bovine photoreceptor outer segments for phagocytosis assays on retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Vis Exp. 2014; 94: 52100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mayerson PL, Hall MO.. Rat retinal pigment epithelial cells show specificity of phagocytosis in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1986; 103: 299–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mazzoni F, Mao Y, Finnemann SC.. Advanced analysis of photoreceptor outer segment phagocytosis by RPE cells in culture. Methods Mol Biol. 2019; 1834: 95–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hall MO, Obin MS, Heeb MJ, Burgess BL, Abrams TA.. Both protein S and Gas6 stimulate outer segment phagocytosis by cultured rat retinal pigment epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2005; 81: 581–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Penberthy KK, Lysiak JJ, Ravichandran KS.. Rethinking phagocytes: clues from the retina and testes. Trends Cell Biol. 2018; 28: 317–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Penberthy KK, Rival C, Shankman LS, et al.. Context-dependent compensation among phosphatidylserine-recognition receptors. Sci Rep. 2017; 7: 14623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]