Abstract

Background

Telehealth services have helped enable continuity of care during the coronavirus pandemic. We aimed to investigate use and views towards telehealth among allied health clinicians treating people with musculoskeletal conditions during the pandemic.

Methods

Cross-sectional international survey of allied health clinicians who used telehealth to manage musculoskeletal conditions during the coronavirus pandemic. Questions covered demographics, clinician-related factors (e.g. profession, clinical experience and setting), telehealth use (e.g. proportion of caseload, treatments used), attitudes towards telehealth (Likert scale), and perceived barriers and enablers (open questions). Data were presented descriptively, and an inductive thematic content analysis approach was used for qualitative data, based on the Capability-Opportunity-Motivation Behavioural Model.

Results

827 clinicians participated, mostly physiotherapists (82%) working in Australia (70%). Most (71%, 587/827) reported reduced revenue (mean (SD) 62% (24.7%)) since the pandemic commenced. Median proportion of people seen via telehealth increased from 0% pre (IQR 0 to 1) to 60% during the pandemic (IQR 10 to 100). Most clinicians reported managing common musculoskeletal conditions via telehealth. Less than half (42%) of clinicians surveyed believed telehealth was as effective as face-to-face care. A quarter or less believed patients value telehealth to the same extent (25%), or that they have sufficient telehealth training (21%). Lack of physical contact when working through telehealth was perceived to hamper accurate and effective diagnosis and management.

Conclusion

Although telehealth was adopted by allied health clinicians during the coronavirus pandemic, we identified barriers that may limit continued telehealth use among allied health clinicians beyond the current pandemic.

Keywords: Telehealth, Musculoskeletal care, Allied health clinicians, Coronavirus pandemic

1. Introduction

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has placed an added level of complexity and concern for face-to-face health care. Given the health risks associated with the coronavirus, and government restrictions on health professionals providing face-to-face care in some regions, telehealth services have been rapidly adopted to maintain continuity of care, and to ensure access to treatment (Greenhalgh et al., 2020; Dantas et al., 2020; Turolla et al., 2020). Telehealth involves remote patient-clinician interaction via synchronous (e.g. telephone or teleconference) or asynchronous means (e.g. wearable sensors) (Dorsey and Topol, 2016). During the coronavirus pandemic, some health systems have responded by providing financial rebates for synchronous telehealth consultations. For example, in Australia, new public health (Medicare) and private insurance rebates were rapidly created in response to the pandemic (Tanne et al., 2020), contributing to a surge in telehealth services use by allied health clinicians and their patients.

Evidence for the efficacy of telehealth continues to emerge (Cottrell and Russell, 2020; Grona et al., 2018). Telehealth delivery of guideline-based recommended care for musculoskeletal conditions (including persistent pain and osteoarthritis) demonstrates similar efficacy to face-to-face care (Cottrell et al., 2017). Telehealth also offers advantages related to access to care for people in rural and remote areas, convenience by reducing travel burden (time and costs) for patients (Turolla et al., 2020; Cottrell and Russell, 2020; Cottrell et al., 2012, 2018), and creating more flexible work arrangements for clinicians (Turolla et al., 2020). There are also challenges with telehealth, such as the perceived or real difficulty in developing an effective therapeutic alliance between the clinician and patient. Also, ability to appropriately diagnose or manage certain conditions (Turolla et al., 2020; Dorsey and Topol, 2016; Cottrell and Russell, 2020; Harst et al., 2019). Patient perception and trust in receiving appropriate care via telehealth and access to required resources, such as appropriate Internet access and teleconference equipment create additional challenges (Turolla et al., 2020; Cottrell and Russell, 2020). Given potential challenges and absence of established guidelines for telehealth assessment and diagnosis of musculoskeletal conditions, it is uncertain how allied health clinicians view, or are prepared to adopt, telehealth during or after the pandemic.

This survey aimed to investigate the use of, and views towards telehealth among allied health clinicians treating people with musculoskeletal conditions during the coronavirus pandemic. Understanding how allied health clinicians use telehealth services with musculoskeletal patients, and their attitudes towards telehealth may help to inform development of future guidelines and training.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

This study was a cross-sectional survey investigating the use and views towards telehealth among allied health clinicians treating people with musculoskeletal conditions during the coronavirus pandemic. Data collection occurred from April to June 2020. The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) guided the reporting of this study (Eysenbach, 2004). Ethical approval was granted by University Human Research Ethics Committee (No. 24212). All participants provided informed online consent.

2.2. Survey instruments development and testing

The online survey was developed by members of the research team (PM, CB, MM, CW, TH), and informed by previous research related to potential barriers and enablers of telehealth adoption (Dorsey and Topol, 2016; Cottrell and Russell, 2020; Harst et al., 2019; Fernandes et al., 2020). The survey was constructed in using Qualtrics software (Qualtrics, Provo, Utah) and included 35 questions (see Supplementary file 1) appearing over 10 electronic pages. Questions covered participant characteristics including demographic factors (age, gender, country of residence), and clinician-related factors (profession, clinical experience, clinical setting, post-graduate training, impact of the pandemic on their clinical revenue, percentage of total caseload that included people with musculoskeletal conditions). Clinicians were also asked about telehealth use (percentage of telehealth caseload pre and post coronavirus pandemic onset), telehealth resources used, training in telehealth use, conditions seen using telehealth, and telehealth (as well as face-to-face) management practices (diagnosis, treatment, resources provided to patients). A series of questions were developed based on components of the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) of behavior change. The TDF is a theoretical framework rather than a theory. It provides a theoretical lens through which to view the cognitive, affective, social and environmental influences on behaviour (Atkins et al., 2017). It was initially developed for implementation research and we have chosen it for use in guiding the development of our question set as it identifies key domains of barriers to change in practice. Ten questions (5-point Likert scale) were devised covering perceived role, confidence, available resources and support, effectiveness, value and training. Additionally, open-ended questions explored perceived barriers and enablers to telehealth implementation (Huijg et al., 2014; Lawton et al., 2016). The survey was divided into sections with a maximum of three questions per page.

Prior to launching, the survey was piloted by a convenience sample of five independent allied health clinicians and members of the research team. Changes were subsequently made to improve accuracy and clarity (i.e. phrasing of questions), functionality and data retrieval (i.e. forced response to all questions, appropriate use of multi-select options, and back button added) (See - Supplementary file 1).

2.3. Recruitment and sampling method

Allied health clinicians, defined as any non-medically trained health professionals that consult to people with musculoskeletal conditions, were invited to participate. There were no country limitations to participation. To capture clinicians that provided telehealth during the period of international coronavirus practice restrictions, the survey was live for recruitment between April 24 and June 5, 2020. The advertisement invited ‘all allied health clinicians who have treated (one or more) people with a musculoskeletal complaint through telehealth during the coronavirus pandemic. A convenience sample of allied health clinicians treating people with musculoskeletal conditions were recruited through social media (Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn) accounts of the authors and their networks. Members of the Australian Physiotherapy and Podiatry Associations were also emailed an advertisement promoting study participation. All clinicians were incentivized by offering a free 1-h recorded webinar providing evidence and practical information related to telehealth for musculoskeletal conditions.

2.4. Data analysis

All survey data was exported from Qualtrics to SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) data analysis software. The completion rate (proportion who completed 80% of more of the survey) was reported. Descriptive data were reported for demographic and clinician-related factors. The frequency and proportion of clinicians who used telehealth pre and post coronavirus pandemic onset, and the telehealth resources, training, conditions treated, and management practices was reported descriptively. Attitudes towards telehealth were described by how clinicians were distributed across the 5-point Likert scale. Open questions were entered verbatim into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Albuquerque, USA). An inductive qualitative content analysis approach was used (Braun et al., 2016). Two researchers (JPC, CB) read and re-read the responses and collaboratively identified units of meaning and initial codes. The Capability-Opportunity-Motivation Behavioural Model (COM-B) (Michie et al., 2011) was used to help organise the codes and emergent themes under the broader domains of capability (psychological, physical), opportunity (physical, social) and motivation (reflective, automatic). Applying the COM-B model allows for a simplified understanding of barriers to behaviour change, in order to inform future implementation interventions (Michie et al., 2011). Over several meetings, the two researchers (JPC, CB) discussed and refined the codes and themes, and undertook a frequency count of the content to aid interpretation. A third researcher (PM) was subsequently involved to refine the themes. Differences in researcher perspective and reflexivity were discussed and if necessary, codes and themes were regrouped and recoded until reaching consensus.

3. Results

There were 1185 allied health clinicians who commenced the survey, and 827 completed ≥80% of the questions and were included in analyses (completion rate = 827/1185 = 69%). There were 358 clinicians who completed less than 80% of the survey and most of this subset of respondents (84% [301/358]) consented but did not respond to any questions.

Demographic information for the cohort is shown in Table 1 . Eighty-two percent (688/827) of clinicians were physiotherapists. Detailed demographic information of the cohort is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information for the cohort.

| Frequency (%) | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 38.0 (10.4) | |

| Clinical experience, yrs | 13.5 (10.2) | |

| Proportion of musculoskeletal patients | 82.6 (23.3) | |

| Gender | ||

| Women | 431 (51.4) | |

| Men | 392 46.8) | |

| Prefer not to say | 4 (0.5) | |

| Profession | ||

| Physiotherapist | 688 (82.1) | |

| Podiatrist | 39 (4.7) | |

| Osteopath | 19 (2.3) | |

| Chiropractor | 14 (1.7) | |

| Myotherapist | 11 (1.3) | |

| Occupational therapist | 11 (1.3) | |

| Other | 45 (5.4) | |

| Proportion with postgraduate training | 540 (65) | |

| Post graduate training | ||

| Post graduate certificate | 152 (18.1) | |

| Post graduate diploma | 94 (11.2) | |

| Masters by coursework | 238 (28.4) | |

| Masters by research | 24 (4.1) | |

| PhD | 34 (4.1) | |

| Other | 48 (57.3) | |

| Region | ||

| Australia & New Zealand | 481 (59.7) | |

| Europe | 228 (27.6) | |

| North America | 64 (7.7) | |

| Asia | 14 (1.7) | |

| South America | 11 (1.3) | |

| Middle East | 10 (1.2) | |

| Africa | 6 (0.7) | |

| Clinical setting | ||

| Private practice | 547 (65.3) | |

| Private hospital (acute) | 18 (2.1) | |

| Private hospital (rehab) | 26 (3.1) | |

| Public hospital (acute) | 101 (12.1) | |

| Public hospital (rehab) | 92 (11.1) | |

| Community or home-based rehab | 116 (13.8) | |

| Other | 103 (12.3) | |

3.1. Financial impact of the coronavirus

Seventy-one percent (587/827) of clinicians reported reduction in revenue since the coronavirus pandemic and 23% (190/827) reported the question was not applicable to their individual working circumstances (e.g. they worked in the public sector). Clinicians reported a mean (SD) revenue reduction of 62% (SD = 24.7%).

3.2. Telehealth practices

Two-thirds of clinicians (66%, 547/827) reported not using telehealth at all prior to the pandemic. The median proportion of people seen via telehealth by clinicians increased from 0% pre (IQR 0 to 1) to 60% during the pandemic (IQR 10 to 100).

All clinicians (100%, 827/827) used subjective questioning, most (86%, 713/838) assessed functional tests (e.g. range of motion, single leg squat task). Approximately half used patient self-delivered palpation (52%, 427/827) and patient self-delivered special tests (55%, 457/827) to assist with diagnosis. In free text responses, clinicians reported using multiple other diagnostic strategies, including: running and walking gait assessments, patient reported outcome measures, body charts, accessing diagnostic imaging reports or ordering pre appointment imaging, family member or carer assisted tests/palpation, observation (e.g. of swelling, alignment) and use of on-screen annotations (e.g. joint range measurement).

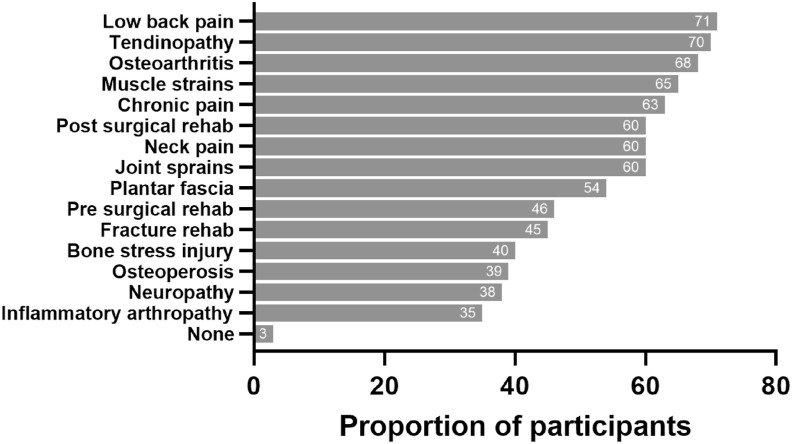

Proportion of participants who reported using telehealth for selected conditions and services is shown in Fig. 1 . Only 3% (23/838) of clinicians reported they would not consider treating any musculoskeletal conditions or providing any services via telehealth. Clinicians also indicated they used telehealth to treat a variety of other non-musculoskeletal conditions (e.g. cancer rehabilitation, concussion, respiratory conditions, falls or balance concerns).

Fig. 1.

Proportion of participants using telehealth for selected conditions and services.

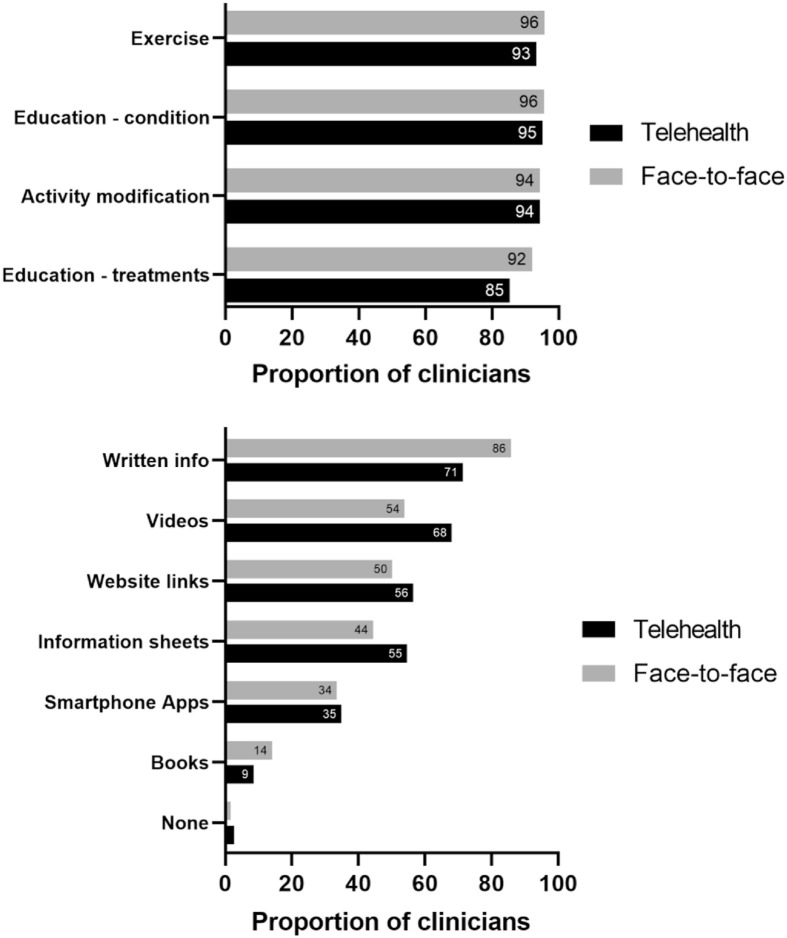

Exercise, and education or advice were commonly delivered during face-to-face and telehealth consultations (Fig. 2 a). Clinicians also reported providing advice about self-administration of manual therapy (84%, 700/838), taping (65%, 546/838), hot/cold therapy (38%, 314/838), electrotherapy (19%, 160/838) and shockwave therapy (13%, 109/838) during face-to-face consultations. During telehealth, 93% (782/838) provided advice about self-massage, mobilisation, tape or hot/cold therapy. Fig. 2b shows resources provided to patients during face-to-face and telehealth consultations. Written information was commonly delivered, as were videos, website links and information sheets.

Fig. 2.

Management (a) and resources used (b) in face-to-face and telehealth care.

When compared to face-to-face care, 43% (238/787) of clinicians reported they spend the same time for a telehealth consultation, while 30% spent less (238/787) and 26% spent more (210/787). The remaining 5% (40/787) were unsure. Compared to face-to-face care, almost half (49%, 383/787) reported they would see people fewer times with telehealth, while 36% (285/787) would see people the same number of times, and 10%, (76/787) would see them more. The remaining 6% (44/787) were unsure.

3.3. Telehealth resources and education

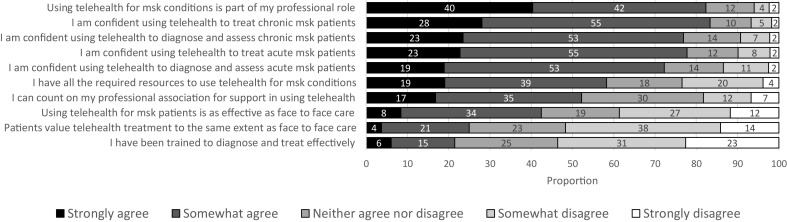

Fig. 3a shows the technology used to provide telehealth services. One-fifth of clinicians selected ‘other’ and reported using various teleconference applications (e.g. American Medical Software, AccuRx, Blue Eye, Bluejeans, Cliniko, Google Meet, Google Hangouts, Gensolve, Doxy, Jane, Microsoft Teams, etc), or they reported using a combination of different teleconference applications.

Fig. 3.

Primary telehealth communication means (a) and sources of telehealth information (b).

Over two-thirds of clinicians cited receiving telehealth information during the pandemic from speaking with colleagues or websites, and more than half from their professional associations, or social media (Fig. 3b). Clinicians also reported accessing telehealth information via their telehealth providers (e.g. Cliniko, Physitrack), and podcasts.

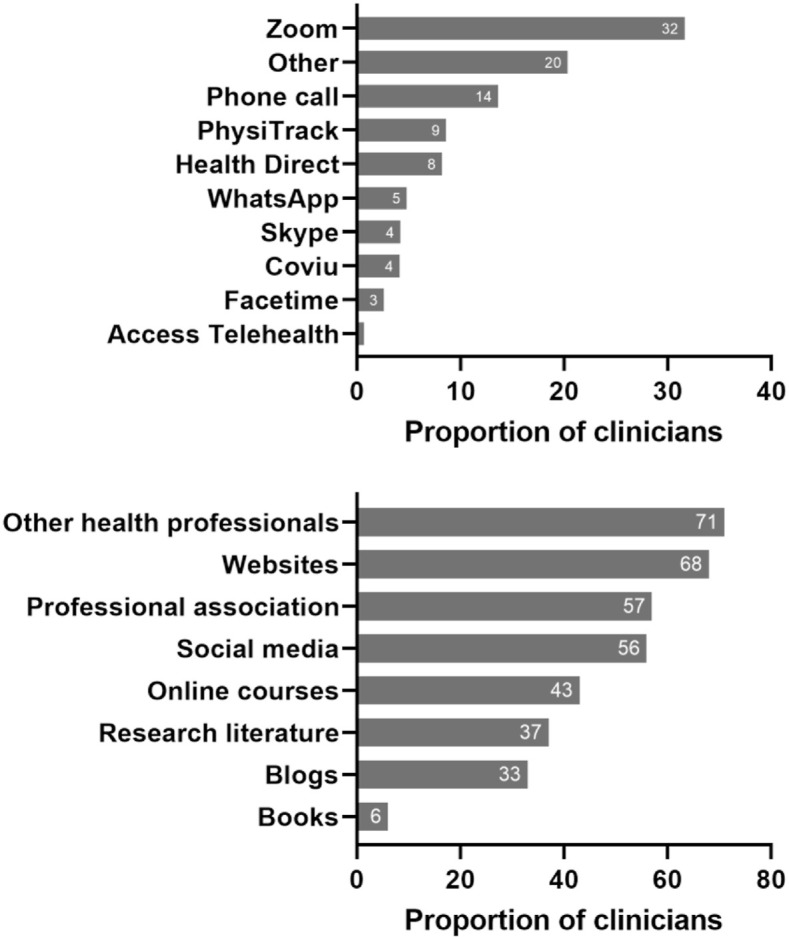

3.4. Attitudes towards telehealth

Fig. 4 shows results related to perceived role, confidence, capabilities, support, value, and training related to telehealth.

Fig. 4.

Attitudes towards telehealth.

3.5. Perceived challenges and enablers to telehealth

Barriers and enablers to implementing and using telehealth are summarised in Table 2 , with the textual data and coding provided in the Supplementary file 2. A total of 5 domains, 25 barrier themes, 14 barrier and enabler themes, and 4 enabler themes were identified. The COM-B domain with the most themes (n = 15) identified was ‘physical opportunity’.

Table 2.

Outline of the main themes related to barriers and enablers, with illustrative quotes.

| THEMES | ILLUSTRATIVE QUOTES |

|---|---|

| PSYCHOLOGICAL CAPABILITY | |

| Barriers | |

| Clinicians perception | “Perception of no hands on as missing something in treatment, takes away the “feel” we get from using our hands to assess/treat/reevaluate etc” (P29) |

| Communication | “Increased communication issues to language/education/health literacy and ability to adapt communication style” (P94) |

| Diagnosis | “Having been a “hands on” physio for 35 years, I really struggle to do a thorough objective examination to compare with my subjective examination. Without being able to make an accurate clinical diagnosis, this affects my treatment plan.” (P64) |

| Barriers/Enablers | |

| Knowledge/skills | “I've always been hands on and prefer face to face. I think I'm better at cues and instructions when there in person as I'm so new to using telehealth.” (P115) |

| “Our health system is traditionally passive so it is dependent on the patients perception on how to manage health conditions. If they can understand the benefits of a more autonomous and self efficacious program we should be able to improve patient outcomes. “ (P206) | |

| “Clinician expertise- we are all-learning as we go, our team had its first virtual team meeting only on19/3/20 and we are now assessing, treating and providing virtual exercise groups! Steep learning curve+++" (P302) | |

| Technology (literacy/ability) | “Variable ability of users to set up tech correctly ie position of camera to observe functional movements” (P69) |

| Confidence (clinician and patient) | “Patients acceptance and confidence to use technology” (P82) |

| “Lack of confidence in both the clinician and the patient that telehealth can deliver what's needed.” (P162) | |

| Enablers | |

| Resources | “Upskilling - no comprehensive resources for myself as a practitioner” (P403) |

| PHYSICAL OPPORTUNITY | |

| Barriers | |

| Diagnosis | “Inability to properly objectively assess - this is especially relevant to joint special testing. Also having to rely on patients and camera angles means observation skills are more difficult and require more explanation. “ (P528) |

| Risk assessment/safety | “Screening of red flags and potential serious pathology” (P90) |

| “I'm uneasy around progressing patients to more difficult exercises - particularly if I've only ever met them via telehealth. To challenge them and progress towards high level goals, they will likely need more difficult exercises but I am mostly concerned around safety - particularly for patients who live alone and don't have someone who can supervise at home/provide assistance when needed.” (P513) | |

| Internet quality | “Internet speed/connection. “ (P16) |

| “The clients internet bandwidth and clarity of camera” (P116) | |

| “Working in a rural area means there has been issues with reliability of the internet and this can be frustrating. “ (P119) | |

| Assessment quality/accuracy - e.g. special test, body language | “Having a proper view of the patient not being sure of certain angles (for exampre trunk rotation or pelvic tilt). Difficult to do precise tests when I am used to rely in my hands and what I feel on palpation” (P680) |

| “Inability to perform objective tests (I think it impacts ability to fully reassure patient regarding prognosis and treatment plan)" (P755) | |

| Exercise guidance | “I also find some rehab exercises hard to do remotely. In person you can help demonstrate and adjust someones form so they do it correctly. For me this has been the main barrier. “ (P709) |

| “Closer supervision of exercises/corrections may be lost through a flat screen. Closer observation during examination for subtle changes in movement patterns can be missed. “ (P203) | |

| Environmental barriers - e.g. patient's space for consult | “Access to appropriate rehab equipment for patients in the home environment.” (P654) |

| “Completing functional assessments depends on patients living space. Problems with wifi connection. “ (P616) | |

| “Patients having suitable private environment for interaction " (P567) | |

| Environmental barriers - e.g. health services | “space required - poor ergonomics for long periods at computer ++, noisy with multiple clinicians using telehealth in shared space " (P244) |

| “Appropriate patient Settings e.g ability to see detail of what patient is doing when following your instructions. “ (P220) | |

| “Infrastructure available in the public hospital ie our desktops did have speakers, we have had to source headphones/bluetooth devices to enable use/use our own laptops/have workstation on wheels with tap on tap off functionality reimaged to a typical laptop. “ (P261) | |

| Patient-therapist relationship | “Creating the same sense of rappore and trust with a patient is challenging over video. “ (P53) |

| “Face to face care allows contact, proximity and most patients like to see you and how we react or answer to their concerns.” (P62) | |

| “Lack of presence and trust building to create therapeutic alliance” (P75) | |

| “Not being able to touch patients and build a therapeutic alliance with them can sometimes leave the patient feeling they are getting sub standard care.” (p717) | |

| Physical distance - lack of physical interaction | “Face to face interactions are a lot more beneficial for patents because human have evolved to interaction with touch and body language that does not convey well over video.” (p736) |

| “Face to face is easier to create a patient/Physio relationship, and develop trust. I have not yet undertaken an initial Telehealth consult.” (P617) | |

| Management delivery (Hands on) | “Being able to use manual skills to assess and treat ultimately leading to a potential misdiagnosis and impacting on patient time of recovery. We know that with some conditions patients may respond to exercise based therapy the same way as the may respond to exercise combined with manual therapy. Manual therapy can speed the recovery times leading to a reduction in pain, faster return to work whilst reducing risk of other joints/healthcare systems being affected” (P714) |

| “Without hands on, you cannot educate the patient on correct movement patterns, identify issues and provide relief " (P207) | |

| Barriers/Enablers | |

| Technology (resources and access inequality) | “Quality of technology/camera and internet connection " (P56) |

| “Additionally clients access to technology, familiarity with apps etc, bandwidth restrictions or limitations all impact on the ability to drivers of services, as does subscription costs for video based platforms, especially for groups.” (p103) | |

| “the technology capabilities of my clientele; many elderly patients don't seem to have the technology or family support for this to be feasible with them” (P252) | |

| System barriers, funding | “Patients acceptance of Telehealth and ongoing ability to receive rebates from Medicare and private health funds” (P12) |

| “In the United States, it is not a nationally covered service for physical therapists, so getting this changed at a legislative is very important for PT's and the future of our profession under the current Pandemic landscape. Politics and insurance companies are the hurdle.” (P154) | |

| “LACK OF FUNDING SUPPORT (for both face-to-face and Telehealth) when there is clear research showing equal efficacy and better cost effectiveness. Yet Arthroscopes/repairs are heavily subsidised, yet education, supervised exercise, weight-loss and other lifestyle/environmental strategies are not.” (P54) | |

| Suitability of condition (e.g. complex acute conditions) | “Many of these clients (e.g.acute back and neck pain) are not coming forward for treatment as I think they cannot see how they would benefit from telehealth. I do think we could help them but that it would be likely to be a compromise for many conditions.” (P304) |

| “The main reason is that it would be difficult to fully assess a patient to determine their musculoskeletal condition. There are issues/causes for conditions that can only be determined by a hands on/face to face consult. “ (P624) | |

| “Assessing acute MS injuries, particularly if needing to assess ligamentous stability, also to check for acute fractures. (P333) | |

| Enablers | |

| Exercise and self-management | “Unable to provide manual techniques, massage, shockwave, dry needling, taping & splinting as per face to face - even if not most effective form of treatment in isolation, in combination with education/exercise I feel it meets patient expectations & can help with desensitization/range of motion etc depending on condition " (P88) |

| “To also convince patients that many musculoskeletal can be self managed by exercise and movement rather than manual and electro therapy.” (P1) | |

| SOCIAL OPPORTUNITY | |

| Barriers | |

| Face to face rehab (e.g. ortho, manual) | “Perception of no hands on as missing something in treatment, takes away the “feel” we get from using our hands to assess/treat/reevaluate etc” (P29) |

| Lack of hands on - impact on assessment quality/accuracy - (patient perspective) | “Public awareness on the need for hands on” (P21) |

| Lack of hands on - impact on management quality/accuracy - (patient perspective) | “Patient perception of what is gained through hands-on treatment is the biggest barrier for them to engage in Tele health. “ (P100) |

| “Over my 28 years of clinical practice all my experience and training has been in face to face settings. I use hands on techniques with most clients, and it is these skills that I can't apply remotely. Not all clients see the benefits of Telehealth, and without face to face contact and the hands on aspects of care are unsure of it's value. “ (P103) | |

| “Patients are not used to telehealth. The histoire of our profession in France emphasize manual therapy and massage over active therapy. It is difficult to make them accept exercises as the go-to way to be treated, so it is even more difficult via telehealth. “ (P223) | |

| Patients not getting immediate relief from self-management strategies and therefore get discouraged (P235) | |

| Barriers/Enablers | |

| Patient attitude re quality/perceived or actual effectiveness | “Patient perception-General impression from patient that teleheath sessions are inferior to face-to-face session which affects uptake. However, generally positive response from clients who agreed to telehealth sessions.” (P93) |

| “Some people want hands on treatment and might value the service less if they don't receive that” (P15) | |

| “Patient and clinician beliefs that Telehealth is the lesser option” (P112) | |

| Patient attitude regarding self-management | “The challenges are getting the patient on board with telehealth regarding its value and effectiveness compared to face to face treatment. Also patients who are used to always receiving hand on treatment who believe this is the only modality that will improve their condition. (P149) |

| “Patient expectation that telehealth won't give them what they need or be as effective as face to face appointments. Patient's not wanting to take responsibility for self care and preferring to rely on hands on treatment” (P344) | |

| “Patient expectations regarding what physiotherapy is. Clinic expectations from seasoned manual therapists who have built the perception that you need hands on therapy.” (P10) | |

| Patients perception and engagement/social acceptance | “My patients tell me they are reassured by our conversation, advice and exercises but still want to see me face to face as soon as possible. I see a huge problem in patient expectation. They feel they are missing out and will not pay full price for session but I work harder and take longer to do follow up exercise e-mails and resources.” (P111) |

| “People are not sure and are unaware of the benefits of telehealth” (P154) | |

| “Patient perception. I believe that the patients perceive telehealth as lower value care than face-to-face sessions.” (P168) | |

| REFLECTIVE MOTIVATION | |

| Barriers | |

| Impact on clinician (e.g. time, admin, isolation) | “Change in culture of being in a room with a laptop rather than in human contact with colleagues and clients. People's availability - if they don't turn up for appointment in person is clear but if not able to contact person - how to complete as not truly a DNA - how many times do you keep trying to connect?!?!" (P166) |

| “Isolation from team” (P92) | |

| “The biggest change is the factor of time. It takes more time to demonstrate or describe exercises using video than in a clinic setting, and time is also spent in diagnosis and assessment because pt's have to put themselves in position which is all active range of motion.” (P202) | |

| Patient-therapist relationship | “Lack of confidence in both the clinician and the patient that telehealth can deliver what's needed. Therefore, perhaps the therapeutic effect of the experience is diminished.” (P162) |

| “Creating the same sense of rapport and trust with a patient is challenging over video. “ (P53) | |

| Lack of hands on - impact on AX quality/accuracy - (clinician perspective) | “Same goes for tactile cueing - it's just not the same. Often in person I would gentle guide my patient towards to movement, or enable them to get tactile feedback from hands on me whilst executing the exercise. My communication and fill of words has had to increase significantly.” (P767) |

| “Touch is an important part of assessment. Asking the patient to do it and report back is sometimes difficult and unreliable” (P736) | |

| “Being able to use manual skills to assess and treat ultimately leading to a potential misdiagnosis and impacting on patient time of recovery. We know that with some conditions patients may respond to exercise based therapy the same way as the may respond to exercise combined with manual therapy. However, manual therapy can speed the recovery times leading to a reduction in perceived pain, faster return to work whilst reducing risk of other joints/healthcare systems being affected” (P714) |

|

4. Discussion

Our data demonstrate an extraordinary shift toward telehealth, with median reported proportion of telehealth consultations per week increasing from 0% pre coronavirus to 62% during the pandemic. This shift reflects most clinicians (82%) agreeing that telehealth was part of their professional role, and most clinicians (76–83%) agreeing they were confident in diagnosing, assessing, and treating both acute and chronic musculoskeletal conditions via telehealth. Reported telehealth care during the coronavirus pandemic was broadly similar to face-to-face care, focused on exercise, education and activity modification, but obviously without provision of hands on passive treatments.

Despite high rates of adoption and reported confidence among clinicians, only 42% agreed that telehealth was as effective as face-to-face care, and just one in four agreed that patients valued telehealth to the same extent. This suggests that many clinicians adopted telehealth due to necessity, making it questionable whether they would persist with its use, once barriers to face-to-face care were removed. Importantly, these perceptions among clinicians and patients about inferior value of telehealth are contrary to emerging evidence evaluating efficacy in musculoskeletal pain conditions, including high patient satisfaction and equivalent clinical outcomes (Cottrell et al., 2017).

Qualitative themes helped to explain clinician perceptions about telehealth. Many focused on the lack of physical contact, perceiving this to hamper accurate and effective diagnosis and management. Consistent with this view, Cottrell and Russell (2020) (Cottrell and Russell, 2020) suggest telehealth offers good validity for observational assessments (e.g. pain, swelling, joint range, balance and gait) but not for assessments traditionally requiring skilled physical contact (e.g. some ‘special’ tests or neurodynamic assessments). Many clinicians also expressed the view that patients expect them to provide ‘hands-on’ care, which may be a barrier to sustained implementation of telehealth. However, the belief that telehealth was inferior to face-to-face care was not consistent across all clinicians. Some felt that telehealth facilitated acting as coaches enabling encouragement of self-management, rather than their traditional role as ‘fixers’, providing hands on care. This shift away from passive to more active care facilitated by telehealth is consistent with guideline recommendations for common musculoskeletal conditions including osteoarthritis and low back pain (Lin et al., 2020), indicating telehealth could improve the value of care provided.

Only 21% of clinicians agreed they had been trained to provide telehealth services to people with musculoskeletal conditions. This widespread perception of inadequate training was mirrored by many clinicians reporting in open-ended questions that they turned to peer support and mentoring (e.g. experienced clinician observation) to upskill. Addressing these apparent gaps in telehealth training requires consideration to increasing telehealth and digital health training opportunities for allied health clinicians and students (Brunner et al., 2018), including tailoring to varied allied health clinicians roles and work settings (e.g. private practice vs hospital) (Brunner et al., 2018). The urgency in addressing these training needs extends beyond the coronavirus public health emergency (Greenhalgh et al., 2020). Improved telehealth access and delivery is needed to also address rapidly evolving health care models (Gray et al., 2014), growing demand for digital health interventions (Coughlin et al., 2018), and need to improve healthcare access for people in remotely located areas (Cottrell and Russell, 2020). A focus on telehealth implementation strategies including training, detailed telehealth practice guidelines, and clear guidance to clinicians and patients on conditions that are amenable to telehealth is strongly encouraged.

‘Aligning with evidence of efficacy for telehealth (Cottrell and Russell, 2020), most clinicians reported they would manage common musculoskeletal conditions via telehealth including low back pain, osteoarthritis and tendinopathy. More than half the of the clinicians also reported managing a range of other chronic and acute injuries including muscle and joint strains/sprains, despite an absence of evidence of efficacy to support telehealth for these presentations. Qualitative analysis also indicated a perception that some clinicians felt particular conditions were not suitable for telehealth (e.g. complex acute conditions). Collectively, these findings highlight the need for continued research to develop and evaluate interventions for the broad range of musculoskeletal conditions managed by healthcare systems, in order to provide better guidance for clinical practice.

Beyond any perceived inferior value of telehealth, several other barriers identified in qualitative analysis are worthy of mention. Physical opportunity related factors made up the bulk of barriers identified, including environmental (e.g. space, funding) and resource (e.g. internet, software) factors related to both clinicians and patients. This was consistent with only 58% of the cohort agreeing that they had adequate resources to implement telehealth. Similar environmental and resource-related barriers have been identified in the literature (Cottrell and Russell, 2020; Lee et al., 2018). Issues with communication and developing rapport with the patient were also identified as barriers to telehealth (Vassilev et al., 2015). Although these barriers have been highlighted in the literature (Cottrell and Russell, 2020; Lee et al., 2018), our analysis provided novel insights into why clinicians may hold these beliefs. Specifically, physical contact was viewed by many respondents as an essential method for developing patient trust and rapport. Clinicians in our cohort also expressed concerns about the demands of telehealth for various reasons, including the requirement to troubleshoot technical issues, generate and send out patient resources, and the associated administration. Many of the barriers related to digital literacy, communication, and perceived demands (e.g. workflow) may be addressed with appropriate training and resources (e.g. telehealth toolkit). There is a clear opportunity for professional bodies to better support clinicians to implement telehealth with only 52% of respondents feeling they are currently adequately supported.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Our findings provide unique insights into the perceptions of allied health clinicians related to telehealth during a time of crisis and swift telehealth uptake. There are several limitations that need to be mentioned. First, we caution against generalising beyond physiotherapists (82% of the cohort). Second, our cohort reflect the views of less experienced clinicians, and may not be generalised to all clinicians. Two thirds of respondents had not used telehealth at all prior to the coronavirus pandemic and we incentivized respondents with free telehealth education. It is possible that their views may change with continued telehealth experience, or education and training to use telehealth. Although this limits the generalisability, it is a key population to study because they are likely to experience the greatest difficulty in adopting telehealth. Third, given the online nature of the survey, we could not verify who completed the survey or whether the same people completed the survey more than once. The online nature of this survey also means that it was most likely already biased towards people who access information digitally and are comfortable with the digital environment. We may therefore have missed a population of less digitally enabled clinicians for whom there may be different barriers and attitudes. Fourth, although we used broad open questions to gather rich data on barriers and enablers to telehealth use, our survey design did not allow for in-depth exploration that could be expected from an interview or focus group design.

5. Conclusion

Allied health clinicians rapidly adopted telehealth during the coronavirus pandemic, treated a range of musculoskeletal conditions and view it as part of their clinical role. Yet, most felt they lacked adequate training to deliver telehealth services, and that telehealth was less effective than face-to-face care and undervalued by patients. These barriers may limit continued telehealth use among allied health clinicians beyond the pandemic. Future research should consider strategies to address patient and clinician barriers to telehealth as well as improving the current evidence base.

Footnotes

Ethics was granted from Monash University Huiman Ethics Committee.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msksp.2021.102340.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Atkins L., Francis J., Islam R., et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement. Sci. 2017;12:77. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V., Weate P. 2016. Using Thematic Analysis in Sport and Exercise Research. Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise; pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner M., McGregor D., Keep M., et al. An eHealth capabilities framework for graduates and health professionals: mixed-methods study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018;20 doi: 10.2196/10229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell M.A., Russell T.G. Telehealth for musculoskeletal physiotherapy. Musculoskeletal Sci. Practice. 2020:102193. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2020.102193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell E., McMillan K., Chambers R. A cross-sectional survey and service evaluation of simple telehealth in primary care: what do patients think? BMJ open. 2012;2 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell M.A., Galea O.A., O'Leary S.P., et al. Real-time telerehabilitation for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions is effective and comparable to standard practice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2017;31:625–638. doi: 10.1177/0269215516645148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell M.A., Hill A.J., O'Leary S.P., et al. Patients are willing to use telehealth for the multidisciplinary management of chronic musculoskeletal conditions: a cross-sectional survey. J. Telemed. Telecare. 2018;24:445–452. doi: 10.1177/1357633X17706605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin S., Roberts D., O'Neill K., et al. Looking to tomorrow's healthcare today: a participatory health perspective. Intern. Med. J. 2018;48:92–96. doi: 10.1111/imj.13661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas L.O., Barreto R.P.G., Ferreira C.H.J. Digital physical therapy in the COVID-19 pandemic. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2020;24(5) doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey E.R., Topol E.J. State of telehealth. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:154–161. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1601705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E-surveys (CHERRIES) J. Med. Internet Res. 2004;6 doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. e34. 2004/09/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes L.G., Devan H., Kamper S.J., et al. Enablers and barriers of people with chronic musculoskeletal pain for engaging in telehealth interventions: protocol for a qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis. Syst. Rev. 2020;9:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13643-020-01390-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray K., Dattakumar A., Maeder A., et al. 2014. Advancing Ehealth Education for the Clinical Health Professions: Final Report 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T., Wherton J., Shaw S., et al. Video consultations for covid-19. Br. Med. J. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grona S.L., Bath B., Busch A., et al. Use of videoconferencing for physical therapy in people with musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare. 2018;24:341–355. doi: 10.1177/1357633X17700781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harst L., Lantzsch H., Scheibe M. Theories predicting end-user acceptance of telemedicine use: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019;21:e13117. doi: 10.2196/13117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huijg J.M., Gebhardt W.A., Dusseldorp E., et al. Measuring determinants of implementation behavior: psychometric properties of a questionnaire based on the theoretical domains framework. Implement. Sci. 2014;9 doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-33. 33. 2014/03/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton R., Heyhoe J., Louch G., et al. Using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to understand adherence to multiple evidence-based indicators in primary care: a qualitative study. Implement. Sci. 2016;11 doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0479-2. 113. 2016/08/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.C., Davenport T.E., Randall K. Telehealth physical therapy in musculoskeletal practice. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2018;48:736–739. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2018.0613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin I., Wiles L., Waller R., et al. What does best practice care for musculoskeletal pain look like? Eleven consistent recommendations from high-quality clinical practice guidelines: systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020;54:79–86. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S., van Stralen M.M., West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011;6 doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. 42. 2011/04/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanne J.H., Hayasaki E., Zastrow M., et al. Covid-19: how doctors and healthcare systems are tackling coronavirus worldwide. Br. Med. J. 2020:368. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turolla A., Rossettini G., Viceconti A., et al. Musculoskeletal physical therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: is telerehabilitation the answer? Phys. Ther. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzaa093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilev I., Rowsell A., Pope C., et al. Assessing the implementability of telehealth interventions for self-management support: a realist review. Implement. Sci. 2015;10:59. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0238-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.