Key Points

Question

How do estradiol levels in male patients with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer change after 3 months of therapy with aromatase inhibitor (AI) plus gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue (GnRHa) compared with GnRHa plus tamoxifen or tamoxifen alone?

Findings

A total of 52 patients were evaluable in this multicenter, phase 2 randomized clinical trial. There was a profound decrease of estradiol levels in patients receiving tamoxifen plus GnRHa (−85%) vs AI plus GnRHa (−72%), and an increase of estradiol in patients receiving tamoxifen alone (+67%).

Meaning

The combination of AI or tamoxifen with GnRHa significantly decreases the estradiol levels in male patients in contrast to tamoxifen alone after 3 months of therapy.

This randomized, multicenter clinical trial assesses changes in estradiol levels in male patients with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer after treatment with aromatase inhibitor plus gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue, with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue plus tamoxifen, or with tamoxifen alone.

Abstract

Importance

The extent of changes in estradiol levels in male patients with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer receiving standard endocrine therapies is unknown. The sexual function and quality of life related to those changes have not been adequately evaluated.

Objective

To assess the changes in estradiol levels in male patients with breast cancer after 3 months of therapy.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This multicenter, phase 2 randomized clinical trial assessed 56 male patients with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer. Patients were recruited from 24 breast units across Germany between October 2012 and May 2017. The last patient completed 6 months of treatment in December 2017. The analysis data set was locked on August 24, 2018, and analysis was completed on December 19, 2018.

Interventions

Patients were randomized to 1 of 3 arms: tamoxifen alone or tamoxifen plus gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue (GnRHa) or aromatase inhibitor (AI) plus GnRHa for 6 months.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was the change in estradiol levels from baseline to 3 months. Secondary end points were changes of estradiol levels after 6 months, changes of additional hormonal parameters, adverse effects, sexual function, and quality of life after 3 and 6 months.

Results

In this phase 2 randomized clinical trial, a total of 52 of 56 male patients with a median (range) age of 61.5 (37-83) years started treatment. A total of 3 patients discontinued study treatment prematurely, 1 in each arm. A total of 50 patients were evaluable for the primary end point. After 3 months the patients’ median estradiol levels increased by 67% (a change of +17.0 ng/L) with tamoxifen, decreased by 85% (−23.0 ng/L) with tamoxifen plus GnRHa, and decreased by 72% (−18.5 ng/L) with AI plus GnRHa (P < .001). After 6 months, median estradiol levels increased by 41% (a change of +12 ng/L) with tamoxifen, decreased by 61% (−19.5 ng/L) with tamoxifen plus GnRHa, and decreased by 64% (−17.0 ng/L) with AI plus GnRHa (P < .001). Sexual function and quality of life decreased when GnRHa was added but were unchanged with tamoxifen alone.

Conclusions and Relevance

This phase 2 randomized clinical trial found that AI or tamoxifen plus GnRHa vs tamoxifen alone led to a sustained decrease of estradiol levels. The decreased hormonal parameters were associated with impaired sexual function and quality of life.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01638247

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) in men is rare and accounts for approximately 1% of all BC cases.1,2,3 The great majority of existing data are case reports and retrospective monocentric studies. Data from large-scale prospective, randomized clinical studies are lacking and optimal treatment strategies are therefore unknown. Treatment recommendations have been extrapolated from treatment of BC in women.

More than 90% of male BCs are hormone receptor (HR) positive. Adjuvant endocrine treatment with tamoxifen (20 mg/d) for at least 5 years is the standard of care for treatment of male patients with HR-positive BC and is recommended by national and international guidelines.4,5,6,7,8 Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) improve the disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) in premenopausal (with added gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues [GnRHa]) and postmenopausal women.9,10,11 The efficacy of AI monotherapy in men with BC is less pronounced. A pooled analysis on 105 cases of HR-positive metastatic male BC showed a higher clinical benefit rate (odds ratio [OR], 3.37)12 when GnRHa was added to AI compared with AI alone with no effect on progression-free survival (PFS) or OS. A smaller analysis on 60 male patients with metastatic BC showed a marginal improvement of PFS and OS (11.6 months vs 6 months for PFS and 29.7 months vs 22 months for OS; both P = .05) when GnRHa was added to AI.13 In a German registry, female patients with BC treated with AI had significantly longer 5-year OS compared with male patients (85.0% vs 73.3%; P = .03), whereas tamoxifen-treated male and female patients with BC had comparable 5-year OS (89.2% vs 85.1%; P = .97).14,15 Accordingly, retrospective studies showed a worse outcome for men receiving AI alone compared with those receiving tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment.15 Therefore, guidelines recommend to add GnRHa if AI is the preferred endocrine backbone.4,5,7 Data from the international BC program observed a significant improvement in survival over time,16 but is still worse compared with survival outcomes for female patients with BC.17,18

Data from small retrospective studies show a reduced compliance for men receiving tamoxifen compared with women, presumably due to specific adverse effects of tamoxifen.19,20 In female patients with BC, endocrine therapy leads to various adverse effects, including decreased libido, hot flushes, musculoskeletal pain, and mood disturbances.21,22 The available data on adverse effects of endocrine therapies in men with BC are retrospectively summarized case series and are more of an anecdotic nature.23,24,25 There has never been a systematic investigation on the extent of the adverse effects, sexual function, and quality of life (QoL) induced by different endocrine approaches. Therefore, we investigated the changes of estradiol levels as the primary objective along the study duration as well as different hormonal parameters and their effects on sexual function and QoL in male patients with HR-positive BC.

Methods

Study Design

The MALE study is a randomized, multicenter, phase 2 trial. Key eligibility criteria were male patients with HR-positive (estrogen receptor and/or progesterone receptor positive) BC, Karnofsky Performance Status of 60% or greater, and with no history or evidence of prostate cancer. All patients provided written informed consent before study participation and biomaterial collection. Eligible patients were randomized in a 3-arm design (1:1:1 ratio) to receive standard treatment with tamoxifen, 20 mg/d orally; tamoxifen, 20 mg/d orally, with GnRHa; or exemestane (AI), 25 mg/d orally, with GnRHa. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue was administered subcutaneously every 3 months. Treatment was given for 6 months in the neoadjuvant, adjuvant, or metastatic setting. As per national and international guidelines, recommended subsequent treatment with tamoxifen, 20 mg/d orally, alone was conducted regardless of study treatment.26,27,28

Blood samples and questionnaire responses were collected at study entry before treatment initiation and after 3 and 6 months of study treatment. The study was approved by all ethics committees/institutional review boards and the competent authorities. The trial protocol is presented in Supplement 1.

Study Objectives

The primary objective was to compare the changes in 17-β-estradiol (estradiol) levels between patients in the 3 treatment arms after 3 months of therapy. Secondary objectives were to compare estradiol changes after 6 months, the change in the level of testosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), sexual hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), free androgen index (FAI), and dihydrotestosterone (DHT), as well as adverse effects, compliance, and safety between the arms. Analyses of SHBG, FAI, and DHT are part of a standardized analysis of sexual hormonal parameters in men and support the interpretation of changes in testosterone. Further objectives were to evaluate changes in sexual function and QoL using validated questionnaires (self-reporting).

Safety and Compliance

All patients who started treatment were included in the safety set. Safety and compliance as well as QoL analyses were performed based on actual treatment received. The National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 4.0 (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, CTCAE) and the corresponding grading system were used to grade adverse events (AEs). Descriptive statistics were given for compliance parameters such as treatment interruption or permanent discontinuation.

Validated Questionnaires

The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) questionnaire assesses the sexual function and includes dimensions of erectile function, orgasmic function, sexual desire, intercourse satisfaction, and overall satisfaction.29 It divides patients into 2 groups with “potential for erectile dysfunction” (score <21) or “no signs of erectile dysfunction” (score ≥21). The Aging Male Symptom (AMS) Score30 was used to evaluate patients’ QoL by capturing aspects of psychological, physical, and sexual well-being, which are supposed to be associated with androgen decline in aging men. A score of 27 or higher has been defined to be suggestive for androgen deficiency.

Sample Management and Hormone Assays

Hormonal parameters were centrally assessed. Serum aliquots were stored locally at −20 °C until transported to the reference laboratory. All treatment samples were run consecutively blinded to the assigned treatment arm. Reference ranges for men (and minimum detectable values) were estradiol, 27 to 52 (5) ng/L; testosterone, 2.8 to 8.8 (0.1) μg/L; FSH, 1.5 to 12.4 (0.3) IU/L; and LH, 1.7 to 8.6 (0.1) IU/L (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). In the case of early study discontinuation, blood samples were taken at the time of discontinuation.

Statistical Methods

Sample size was calculated based on the following assumptions: mean (SD) baseline estradiol level of 25.0 (8.0) ng/L, no change with tamoxifen alone after 3 months, 50% decrease to 12.5 ng/L estradiol with tamoxifen plus GnRHa, and 80% decrease to 5 ng/L estradiol with exemestane plus GnRHa. Common standard deviation for the decrease in estradiol after 3 months was conservatively estimated at 16 ng/L. Computation using nQuery Advisor 6.0 indicated that 14 patients per group were required for the F-test to have 80% power to detect a difference in mean estradiol decrease between 3 therapy groups at the 5% significance level. Because estradiol levels may not be normally distributed, the total sample size was adapted to 48 evaluable patients to provide sufficient power for a non-parametric test (Kruskal-Wallis). The overall significance level for the study was set to α = 0.05. All statistical tests were 2-sided. Randomization was performed using the Pocock minimization method, stratified according to prior chemotherapy (yes vs no).

Because the test of normality failed, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare decreases in hormone levels between arms after 3 months and 6 months of treatment. Pairwise comparisons of tamoxifen plus GnRHa, an AI plus GnRHa, and tamoxifen were planned hierarchically in case the overall primary test was significant and were performed, using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test; no other adjustments for multiplicity were performed.

For the questionnaire, per each score changes from baseline were compared for the treatment groups using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The categorized AMS and IIEF were compared between arms at baseline and at 3 and 6 months with the χ2 test. Additionally, for all continuous parameters at 3 and at 6 months, a nonparametric analysis of covariance sensitivity analysis was performed, covariate adjusted for the baseline value. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and R version 3.2.2 (for box plots and nonparametric ANCOVA) were used for analyses.

Results

Study Cohort

Between October 2012 and May 2017, 56 male patients with HR-positive BC were randomized within 24 centers in Germany. The last patient completed 6 months of treatment in December 2017. A total of 52 patients started treatment and comprised the ITT set (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). The median (range) age was 61.5 (37-83) years, and the majority of participants had T2 (52.9%), G2 (57.7%), ERBB2-negative (86.5%), and node-negative (52.0%) tumors and were included in the adjuvant setting (94.2%). Patient characteristics are summarized in eTable 2 in Supplement 2.

Primary Objective: Change in 17-β-Estradiol Levels After 3 Months

At baseline, median estradiol levels were not significantly different between the 3 treatment arms: 27.0 (range, 5.0-46.0) ng/L for tamoxifen, 33.0 (14.0-45.0) ng/L for tamoxifen plus GnRHa, and 27.5 (17.0-113.0) ng/L for AI plus GnRHa (P = .28) After 3 months, median estradiol values initially increased in the tamoxifen alone arm to 45.0 (19.0-62.0) ng/L, presenting a change of plus 66.7%. Median estradiol levels decreased in the tamoxifen plus GnRHa arm to 5.0 (5.0-46.0) ng/L, presenting a change of minus 84.9%, and in the AI plus GnRHa arm to 7.5 (5.0-52.0) ng/L, presenting a change of minus 72.2%, respectively (P = .01) (Table).

Table. Hormonal Parameters of All Measured Parameters at Baseline, Absolute Values, and Changes After 3 and 6 Months of Therapy.

| Hormonal parameters | Median (range) | P valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tamoxifen (n = 17) | Tamoxifen + GnRHa (n = 15) | Exemestane + GnRHa (n = 18) | Overall (n = 50) | ||

| Estradiol, ng/L | |||||

| BL | 27.0 (5.0 to 46.0) | 33.0 (14.0 to 45.0) | 27.5 (17.0 to 113.0) | 30.0 (5.0 to 113.0) | .28 |

| Change from BL to 3 mo | 17.0 (−6.0 to 29.0) | −23.0 (−40.0 to 22.0) | −18.5 (−100.0 to 21.0) | −13.0 (−100.0 to 29.0) | <.001 |

| Change from BL to 6 mob | 12.0 (−23.0 to 50.0) | −19.5 (−38.0 to 30.0) | −17.0 (−102.0 to 6.0) | −6.5 (−102.0 to 50.0) | <.001 |

| Absolute value at 3 mo | 45.0 (19.0 to 62.0) | 5.0 (5.0 to 46.0) | 7.5 (5.0 to −52.0) | 13.0 (5.0 to 62.0) | .01 |

| Absolute value at 6 mob | 38.0 (5.0 to 77.0) | 13.0 (5.0 to 54.0) | 10.0 (5.0 to 37.0) | 18.0 (5.0 to 77.0) | .03 |

| Testosterone, μg/L | |||||

| BL | 3.7 (1.2 to 7.1) | 3.9 (0.8 to 10.7) | 4.0 (1.1 to 15.0) | 3.9 (0.8 to 15.0) | .73 |

| Change from BL to 3 mo | 2.2 (−1.0 to 4.7) | −3.8 (−10.6 to 3.5) | −3.6 (−14.6 to 7.1) | −2.2 (−14.6 to 7.1) | <.001 |

| Change from BL to 6 mob | 1.6 (−3.1 to 8.3) | −3.7 (−10.6 to 4.3) | −3.5 (−14.7 to 1.0) | −1.9 (−14.7 to 8.3) | <.001 |

| Absolute value at 3 mo | 6.2 (2.2 to 11.4) | 0.1 (0.1 to 6.1) | 0.3 (0.1 to 15.0) | 0.3 (0.1 to 15.0) | .01 |

| Absolute value at 6 mob | 6.0 (0.2 to 13.1) | 0.1 (0.1 to 6.9) | 0.3 (0.1 to 10.9) | 0.40 (0.1 to 13.1) | .01 |

| FSH, IU/L | |||||

| BL | 15.6 (1.8 to 30.4) | 9.7 (2.7 to 60.3) | 9.5 (2.6 to 36.4) | 9.8 (1.8 to 60.3) | .96 |

| Change from BL to 3 mo | 5.0 (0.2 to 21.5) | −9.1 (−56.6 to 7.2) | −4.2 (−28.6 to 5.9) | −1.0 (−56.6 to 21.5) | <.001 |

| Change from BL to 6 mob | 0.6 (−11.0 to 8.3) | −9.7 (−57.3 to 12.3) | −3.3 (−28.7 to 4.5) | −3.8 (−57.3 to 12.3) | .02 |

| Absolute value at 3 mo | 16.2 (2.0 to 51.9) | 1.5 (0.5 to 11.0) | 6.0 (3.7 to 13.6) | 6.0 (0.5 to 51.9) | .01 |

| Absolute value at 6 mob | 11.2 (1.6 to 33.8) | 1.1 (0.3 to 15.0) | 5.6 (3.7 to 11.0) | 5.4 (0.3 to 33.8) | .01 |

| LH, IU/L | |||||

| BL | 6.3 (1.8 to 13.8) | 7.4 (1.6 to 23.1) | 7.6 (3.3 to 23.4) | 7.3 (1.6 to 23.4) | .67 |

| Change from BL to 3 mo | 4.1 (−0.7 to 18.1) | −7.3 (−23.0 to 4.9) | −7.5 (−23.3 to 11.4) | −3.9 (−23.3 to 18.1) | <.001 |

| Change from BL to 6 mob | 2.5 (−13.7 to 20.6) | −6.3 (−22.8 to 8.8) | −7.0 (−18.9 to 10.5) | −3.3 (−22.8 to 20.6) | <.001 |

| Absolute value at 3 mo | 11.3 (3.3 to 30.2) | 0.1 (0.1 to 6.5) | 0.1 (0.1 to 18.6) | 0.3 0 (0.1 to 30.2) | .01 |

| Absolute value at 6 mob | 8.4 (0.1 to 33.9) | 0.1 (0.1 to 11.0) | 0.1 (0.1 to 17.7) | 0.8 (0.1 to 33.9) | .01 |

| DHT, ng/L | |||||

| BL | 282.0 (30.0 to 818.0) | 245.0 (78.0 to 759.0) | 321.5 (68.0 to 1040.0) | 290.0 (30.0 to 1040.0) | .15 |

| Change from BL to 3 mo | 94.0 (−20.0 to 417.0) | −188.0 (−719.0 to 205.0) | −288.5 (−755.0 to 277.0) | −151.5 (−755.0 to 417.0) | <.001 |

| Change from BL to 6 mob | 215.0 (35.0 to 822.0) | −180.0 (−729.0 to 527.0) | −225.0 (−762.0 to 1050.0) | −74.0 (−762.0 to 1050.0) | <.001 |

| Absolute value at 3 mo | 361.0 (30.0 to 886.0) | 31.0 (30.0 to 450.0) | 30.0 (30.0 to 1290.0) | 42.0 (30.0 to 1290.0) | .01 |

| Absolute value at 6 mob | 471.0 (73.0 to 1640.0) | 33.5 (30.0 to 772.0) | 39.0 (30.0 to 2090.0) | 66.0 (30.0 to 2090.0) | .01 |

| FAI | |||||

| BL | 25.0 (8.0 to 58.0) | 25.0 (6.0 to 44.0) | 25.5 (13.0 to 62.0) | 25.0 (6.0 to 62.0) | .99 |

| Change from BL to 3 mo | 12.0 (−7.0 to 35.0) | −24.0 (−43.0 to 24.0) | −22.5 (−56.0 to 128.0) | −17.0 (−56.0 to 128.0) | <.001 |

| Change from BL to 6 mob | 11.0 (−30.0 to 36.0) | −24.0 (−43.0 to 28.0) | −25.0 (−56.0 to 50.0) | −15.5 (−56.0 to 50.0) | <.001 |

| Absolute value at 3 mo | 38.0 (8.0 to 83.0) | 1.0 (1.0 to 49.0) | 2.0 (1.0 to 176.0) | 2.0 (1.0 to 176.0) | .02 |

| Absolute value at 6 mob | 32.0 (3.0 to 71.0) | 1.0 (1.0 to 53.0) | 2.0 (1.0 to 98.0) | 5.0 (1.0 to 98.0) | .04 |

| SHBG, nmol/L | |||||

| BL | 48.0 (17.0 to 108.0) | 52.0 (26.0 to 128.0) | 55.0 (16.0 to 132.0) | 52.5 (16.0 to 132.0) | .59 |

| Change from BL to 3 mo | 5.0 (−36.0 to 41.0) | 17.0 (−18.0 to 72.0) | −6.5 (−34.0 to 23.0) | 2.0 (−36.0 to 72.0) | <.001 |

| Change from BL to 6 mob | 9.0 (−20.0 to 50.0) | 13.0 (−13.0 to 89.0) | −10.0 (−47.0 to 5.0) | 2.5 (−47.0 to 89.0) | <.001 |

| Absolute value at 3 mo | 56.0 (24.0 to 102.0) | 58.0 (40.0 to 200.0) | 48.0 (9.0 to 133.0) | 54.0 (9.0 to 200.0) | .08 |

| Absolute value at 6 mob | 55.0 (27.0 to 111.0) | 54.5 (39.0 to 174.0) | 40.0 (11.0 to 118.0) | 53.0 (11.0 to 174.0) | .07 |

Abbreviations: BL, baseline; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; FAI, free androgen index; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GnRHa, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue; LH, luteinizing hormone; SHBG, sexual hormone-binding globulin.

Kruskal-Wallis test for changes from baseline to 3 or 6 months; nonparametric ANCOVA for 3- or 6-month values (sensitivity analysis).

The 6-month analysis set comprised 46 patients (tamoxifen treated group, 17 patients; tamoxifen plus GnRHa, 14 patients; exemestane plus GnRHa, 15 patients).

Pairwise comparisons showed a significant difference in median change of estradiol levels between tamoxifen vs tamoxifen plus GnRHa or AI plus GnRHa (17.0 ng/L [range, −6.0 to 29.0] vs −23.0 [−40.0 to 22.0] vs −18.5 [−100.0 to 21.0]; respectively, P < .001) but not for tamoxifen plus GnRHa vs AI plus GnRHa (P = .59). The P values at 3 months estradiol from nonparametric analysis of covariance were numerically larger but also significant for the overall comparison (P < .001) and for tamoxifen vs tamoxifen plus GnRHa (P = .02) or AI plus GnRHa (P = .02); but not for tamoxifen plus GnRHa vs AI plus GnRHa (P = .81). Box plots of the analyzed hormonal values are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Values of Estradiol, Testosterone, Follicle-Stimulating Hormone, and Luteinizing Hormone at Baseline and After 3 and 6 Months of Therapy Within the MALE Study.

FSH indicates follicle-stimulating hormone; GnRHa, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue; LH, luteinizing hormone. The 6-month analysis set comprised 46 patients (tamoxifen-treated group, 17 patients; tamoxifen plus GnRHa, 14 patients; exemestane plus GnRHa, 15 patients). The box represents the first quartile, median, and third quartile; the whiskers represent minimal and maximal values within 1.5 of the interquartile range; the small circles are values outside 1.5 of the interquartile range.

Secondary Objective: Change in 17-β-Estradiol Levels After 6 Months

After 6 months, estradiol levels remained suppressed in the 2 arms treated with GnRHa (Figure 1A). Median absolute estradiol values were 38.0 (range, 5.0-77.0) ng/L for tamoxifen, presenting an increase from baseline of 40.7%, and 13.0 (5.0-54.0) ng/L for tamoxifen plus GnRHa and 10.0 (5.0-37.0) ng/L for AI plus GnRHa (P = .03), presenting a decrease from baseline of 60.6% and 63.6%, respectively. Median changes in estradiol levels between baseline and month 6 were significantly different between treatment arms (tamoxifen: 12.0 [−23.0 to 50.0] ng/L; tamoxifen plus GnRHa, −19.5 [−38.0 to 30.0] ng/L; AI plus GnRHa, −17.0 [−102.0 to 6.0] ng/L; P < .001).

Change in Other Hormonal Parameters After 3 and 6 Months

Levels of FSH, LH, and testosterone changed significantly after 3 and 6 months of treatment initiation in all 3 arms (Figure 1 and Table). Patients receiving tamoxifen plus GnRHa and AI plus GnRHa showed a decrease of FSH, LH, and testosterone, whereas patients receiving tamoxifen alone had an increase of these parameters. Changes from baseline to month 3 and month 6 were significantly different between arms for FSH, LH, and testosterone.

When GnRHa was added to tamoxifen or AI, median FAI, a calculated marker for possible testosterone imbalance, decreased from baseline to the threshold of detection after 3 and 6 months. Levels of DHT, the active metabolite of testosterone, and SHBG, a binding protein of testosterone and estrogen, showed an increase when tamoxifen with or without GnRHa was given and a decrease in patients receiving AI plus GnRHa (Table).

Sexual Function and QoL

Sexual function was analyzed using the IIEF questionnaire. The proportion of participants complaining about their sexual function increased with treatment duration.

At baseline, 18 of 52 patients (34.6%; tamoxifen: n = 5; tamoxifen plus GnRHa: n = 6; and AI plus GnRHa: n = 7; P = .75) reported erectile dysfunction, which increased to 27 of 52 patients (54.0%; n = 5, 11, and 11 patients, respectively; P = .03) after 3 months and to 29 of 49 patients (61.7%; n = 4, 12, and 13 patients, respectively; P < .001) after 6 months (Figure 2). As shown, patients receiving tamoxifen monotherapy did not report a clinically meaningful change in their sexual function.

Figure 2. International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) Score at Baseline and After 3 and 6 Months of Therapy Within the MALE Study.

A total of 52 patients were analyzed at baseline and after 3 months; 49 were analyzed after 6 months (due to early discontinuation by 1 patient in each cohort). The box represents the first quartile, median, and third quartile; the whiskers represent minimal and maximal values within 1.5 of the interquartile range; the small circles are values outside 1.5 of the interquartile range.

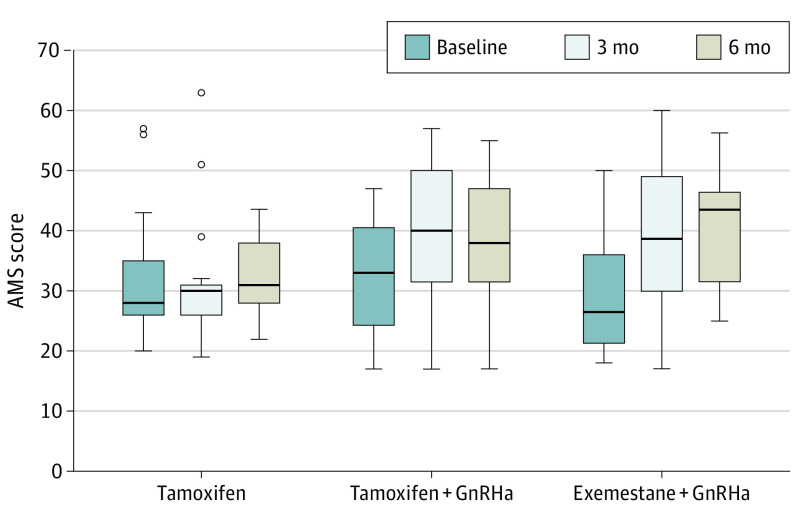

Participants’ QoL (AMS questionnaire) did not significantly deteriorate with treatment duration. At baseline, 31 of 52 patients, (59.6%; tamoxifen: n = 11; tamoxifen plus GnRHa: n = 11; and AI plus GnRHa: n = 9; P = .19), after 3 months 39 of 52 patients (75%; n = 11, 14, and 14, respectively; P = .05), and after 6 months 33 of 49 patients (67.4%; n = 13, 9, and 11, respectively; P = .28) reported to have a reduced QoL (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Aging Male Symptom (AMS) Score at Baseline and After 3 and 6 Months of Therapy Within the MALE Study.

A total of 52 patients were analyzed at baseline and after 3 months; 49 were analyzed after 6 months (due to early discontinuation by 1 patient in each cohort). The box represents the first quartile, median, and third quartile; the whiskers represent minimal and maximal values within 1.5 of the interquartile range; the small circles are values outside 1.5 of the interquartile range.

Safety and Compliance

The safety population included 52 patients. The following AEs had an incidence of 10% or greater with partial differences between treatment arms when GnRHa was added: hot flushes (46.2%; tamoxifen: n = 2; tamoxifen plus GnRHa: n = 10; and AI plus GnRHa: n = 1), erectile dysfunction (30.8%; n = 1, 8, and 7, respectively), decreased libido (42.3%; n = 3, 9, and 10, respectively), bone pain (23.1%; n = 3, 4, and 5, respectively), myalgia (17.3%; n = 3, 4, and 2 respectively), fatigue (38.5%; N = 5, 5, and 10, respectively) and sleeping disorders (7.7%; n = 0, 1, and 3, respectively) (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2).

A total of 5 serious AEs in 5 patients (9.6%) were reported without statistically significant difference between arms (P = .45): CTCAE grade 3 global cardiac decompensation, right groin abscess, gastroenteritis, and visceral arterial ischemia, and hyperglycemia, CTCAE grade 4. All resolved without sequelae. No fatal events occurred.

Discussion

The MALE study is the first randomized phase 2 trial investigating the effects of different endocrine therapies on levels of estrogen and other hormonal parameters and their influence on sexual function and QoL in male patients with HR-positive BC. Treatment with AI or tamoxifen in combination with GnRHa led to a decrease of estradiol levels after 3 and 6 months of therapy. Male patients receiving tamoxifen alone presented an expected moderate increase of estradiol levels during the 6 months on study therapy. Premenopausal patients receiving tamoxifen also show a similar increase in estradiol.31,32 The addition of GnRHa to tamoxifen or AI within the MALE study led to a sustained decrease in estradiol comparable to the data in premenopausal women in the SOFT-TEXT substudy,33 although almost 20% of the women did not have a decrease of estradiol below the threshold. In the MALE study, the largest decrease occurred after 3 months of treatment with tamoxifen plus GnRHa and reached the threshold of detection. Patients receiving AI plus GnRHa showed a similar decrease to just above the detection threshold. In premenopausal women the addition of GnRHa leads to an improved disease-free survival,10 and in prostate cancer the use of a GnRHa improves outcomes. Owing to the design of the MALE study, we are not able to deliver efficacy results; nevertheless, the comparable observations should be considered when treatment initiation is discussed with the patients.

Even in aging men, the testes continue to produce estradiol directly without peripheral aromatization.34 As AI monotherapy suppresses estradiol levels only by about 40% to 50% with an increase in testosterone of about 50%,35 men should be treated according to guidelines for premenopausal women. Therefore, we decided to add GnRHa to endocrine therapies to completely block testicular hormonal production. In the MALE study, GnRHa was administered every 3 months as in the treatment for prostate cancer. In premenopausal patients with BC, there is sufficient evidence that GnRHa 3-monthly and monthly injections provide similar estradiol suppression36,37 with comparable DFS and OS results.38,39,40,41 All 3 therapeutic strategies were well tolerated with no new safety signals.

Sexual function and QoL were assessed using validated questionnaires for self-reporting and adverse event assessment. To evaluate the sexual function as well as QoL, we used the validated AMS30 and IIEF29 questionnaires because the EORTC questionnaires42 for assessing QoL in BC are based on female cohorts and do not consider men’s complaints. The AMS30 and IIEF29 results reflect the testosterone decline as in aging men. Although neither questionnaire has been investigated specifically in cancer patients, we wanted to capture the adverse effects from testosterone and estradiol suppression as we expected that reported adverse effects will arise from hormonal changes rather than the cancer itself. We observed a strong association between the decrease in estradiol and testosterone levels in sexual function and QoL due to the co-administration of GnRHa and tamoxifen or AI. Notably, patients receiving tamoxifen alone did not report significant changes in the patient-reported outcomes. Contrary to our findings, retrospective data and case reports have also described a decrease in sexual function and libido for patients receiving tamoxifen alone.23,43

To our knowledge, MALE is the first randomized study to investigate different endocrine therapy approaches in male patients with HR-positive BC. The strength of the MALE study is its prospective character with the implementation of validated questionnaires to extensively describe the range of adverse effects in addition to the corresponding laboratory values. Describing the influence of different endocrine approaches on sexuality and QoL in men with BC is novel.

Limitations

The study was only powered to adequately detect changes in estradiol values between the arms, not to give any information on cancer outcome. The presented differences in adverse effects, sexual function, and QoL are descriptive and support the findings of the laboratory values. A potential limitation of the study is the small sample size and no arm with an AI alone, which was thought to be potentially detrimental for the given reasons.

Conclusion

The addition of GnRHa to AI or tamoxifen leads to a more profound suppression of estradiol, which is known to increase survival in premenopausal women.10 It seems that male BC can be treated according to premenopausal BC due to the comparable observations of increased estradiol suppression. The addition of GnRHa should be therefore reconsidered as a treatment option in high-risk patients and should be weighed against increased adverse effects. Nevertheless, the influence on survival and adverse effects should be further investigated in a phase 3 trial. Due to the low incidence of male BC, international collaborations are required to do so.

Statistical Analysis Plan and Trial Protocol

eFigure 1. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Diagram of the Male study

eFigure 2. Adverse Events Within the MALE Study With an Incidence ≥10% According to the Reported CTCAE Grading

eTable 1. Normal Ranges and Threshold of Detection of Further Hormonal Parameters

eTable 2. Patient Characteristics in 52 Patients Who Started Treatment

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7-30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giordano SH. Breast cancer in men. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(24):2311-2320. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1707939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korde LA, Zujewski JA, Kamin L, et al. Multidisciplinary meeting on male breast cancer: summary and research recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(12):2114-2122. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.5729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gradishar WJ, Anderson BO, Abraham J, et al. Breast Cancer, Version 3.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(4):452-478. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.0016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hassett MJ, Somerfield MR, Baker ER, et al. Management of male breast cancer: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(16):1849-1863. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardoso F, Kyriakides S, Ohno S, et al. ; ESMO Guidelines Committee . Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(10):1674. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ditsch N, Untch M, Thill M, et al. AGO recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with early breast cancer: update 2019. Breast Care (Basel). 2019;14(4):224-245. doi: 10.1159/000501000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thill M, Jackisch C, Janni W, et al. AGO recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with locally advanced and metastatic breast cancer: update 2019. Breast Care (Basel). 2019;14(4):247-255. doi: 10.1159/000500999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francis PA, Regan MM, Fleming GF, et al. ; SOFT Investigators; International Breast Cancer Study Group . Adjuvant ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(5):436-446. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Francis PA, Pagani O, Fleming GF, et al. ; SOFT and TEXT Investigators and the International Breast Cancer Study Group . Tailoring adjuvant endocrine therapy for premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(2):122-137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) . Aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen in early breast cancer: patient-level meta-analysis of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;386(10001):1341-1352. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61074-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zagouri F, Sergentanis TN, Azim HA Jr, Chrysikos D, Dimopoulos M-A, Psaltopoulou T. Aromatase inhibitors in male breast cancer: a pooled analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;151(1):141-147. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3356-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Lauro L, Pizzuti L, Barba M, et al. Role of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues in metastatic male breast cancer: results from a pooled analysis. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s13045-015-0147-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eggemann H, Ignatov A, Smith BJ, et al. Adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen compared to aromatase inhibitors for 257 male breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137(2):465-470. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2355-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eggemann H, Altmann U, Costa S-D, Ignatov A. Survival benefit of tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitor in male and female breast cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2018;144(2):337-341. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2539-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cardoso F, Bartlett JMS, Slaets L, et al. Characterization of male breast cancer: results of the EORTC 10085/TBCRC/BIG/NABCG International Male Breast Cancer Program. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(2):405-417. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu N, Johnson KJ, Ma CX. Male breast cancer: an updated surveillance, epidemiology, and end results data analysis. Clin Breast Cancer. 2018;18(5):e997-e1002. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2018.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson WF, Jatoi I, Tse J, Rosenberg PS. Male breast cancer: a population-based comparison with female breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):232-239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.8162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anelli TF, Anelli A, Tran KN, Lebwohl DE, Borgen PI. Tamoxifen administration is associated with a high rate of treatment-limiting symptoms in male breast cancer patients. Cancer. 1994;74(1):74-77. Accessed November 18, 2018. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Venigalla S, Carmona R, Guttmann DM, et al. Use and effectiveness of adjuvant endocrine therapy for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer in men. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(10):e181114. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ribi K, Luo W, Bernhard J, et al. Adjuvant tamoxifen plus ovarian function suppression versus tamoxifen alone in premenopausal women with early breast cancer: patient-reported outcomes in the suppression of ovarian function trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(14):1601-1610. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shapiro CL, Recht A. Side effects of adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(26):1997-2008. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106283442607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pemmaraju N, Munsell MF, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH. Retrospective review of male breast cancer patients: analysis of tamoxifen-related side-effects. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(6):1471-1474. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zagouri F, Sergentanis TN, Koutoulidis V, et al. Aromatase inhibitors with or without gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue in metastatic male breast cancer: a case series. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(11):2259-2263. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wibowo E, Pollock PA, Hollis N, Wassersug RJ. Tamoxifen in men: a review of adverse events. Andrology. 2016;4(5):776-788. doi: 10.1111/andr.12197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gradishar WJ, Anderson BO, Balassanian R, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Breast Cancer, Version 1.2017. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(4):433-451. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Senkus E, Kyriakides S, Ohno S, et al. Primary breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up incidence and epidemiology. 2015;26 Suppl 5:v8-30. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Untch M, Huober J, Jackisch C, et al. Initial treatment of patients with primary breast cancer: evidence, controversies, consensus: spectrum of opinion of German specialists at the 15th International St. Gallen Breast Cancer Conference (Vienna 2017). Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2017;77(6):633-644. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-111601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49(6):822-830. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00238-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heinemann LAJ, Saad F, Zimmermann T, et al. The Aging Males’ Symptoms (AMS) scale: update and compilation of international versions. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:15. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liem GS, Mo FKF, Pang E, et al. Chemotherapy-related amenorrhea and menopause in young Chinese breast cancer patients: analysis on incidence, risk factors and serum hormone profiles. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Groom GV, Griffiths K. Effect of the anti-oestrogen tamoxifen on plasma levels of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, prolactin, oestradiol and progesterone in normal pre-menopausal women. J Endocrinol. 1976;70(3):421-428. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0700421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bellet M, Gray KP, Francis PA, et al. Twelve-month estrogen levels in premenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer receiving adjuvant triptorelin plus exemestane or tamoxifen in the Suppression of Ovarian Function Trial (SOFT): The SOFT-EST substudy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(14):1584-1593. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.2259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nordman IC, Dalley DN. Breast cancer in men: should aromatase inhibitors become first-line hormonal treatment? Breast J. 2008;14(6):562-569. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2008.00648.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mauras N, O’Brien KO, Klein KO, Hayes V. Estrogen suppression in males: metabolic effects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(7):2370-2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masuda N, Iwata H, Rai Y, et al. Monthly versus 3-monthly goserelin acetate treatment in pre-menopausal patients with estrogen receptor-positive early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126(2):443-451. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1332-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noguchi S, Kim HJ, Jesena A, et al. Phase 3, open-label, randomized study comparing 3-monthly with monthly goserelin in pre-menopausal women with estrogen receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2016;23(5):771-779. doi: 10.1007/s12282-015-0637-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmid P, Untch M, Kossé V, et al. Leuprorelin acetate every-3-months depot versus cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil as adjuvant treatment in premenopausal patients with node-positive breast cancer: the TABLE study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18):2509-2515. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jonat W, Kaufmann M, Sauerbrei W, et al. ; Zoladex Early Breast Cancer Research Association Study . Goserelin versus cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil as adjuvant therapy in premenopausal patients with node-positive breast cancer: The Zoladex Early Breast Cancer Research Association Study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(24):4628-4635. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.05.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ejlertsen B, Jensen MB, Mouridsen HT, et al. DBCG trial 89B comparing adjuvant CMF and ovarian ablation: similar outcome for eligible but non-enrolled and randomized breast cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 2008;47(4):709-717. doi: 10.1080/02841860802001475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaufmann M, Jonat W, Blamey R, et al. ; Zoladex Early Breast Cancer Research Association (ZEBRA) Trialists’ Group . Survival analyses from the ZEBRA study. goserelin (Zoladex) versus CMF in premenopausal women with node-positive breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(12):1711-1717. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00392-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bjelic-Radisic V, Bottomley A, Cardoso F, et al. An international update of the EORTC questionnaire for assessing quality of life in breast cancer patients: EORTC QLQ-BR45. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(2):283-288. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bradley KL, Tyldesley S, Speers CH, Woods R, Villa D. Contemporary systemic therapy for male breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2014;14(1):31-39. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2013.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Statistical Analysis Plan and Trial Protocol

eFigure 1. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Diagram of the Male study

eFigure 2. Adverse Events Within the MALE Study With an Incidence ≥10% According to the Reported CTCAE Grading

eTable 1. Normal Ranges and Threshold of Detection of Further Hormonal Parameters

eTable 2. Patient Characteristics in 52 Patients Who Started Treatment

Data Sharing Statement