Abstract

Introduction

The number of patients and clinical conditions treated in home healthcare (HHC) is increasing. Care in home settings presents many challenges, including healthcare-associated infections (HAI). Currently, in Belgium, data and guidelines on the topic are lacking.

Aim

To develop a definition of HAI in HHC and investigate associated risk factors and recommendations for infection prevention and control (IPC).

Methods

The study included three components: a scoping literature review, in-depth interviews with individuals involved in HHC and a two-round Delphi survey to reach consensus among key informants on the previous steps’ results.

Results

The literature review included 47 publications. We conducted 21 in-depth interviews. The Delphi survey’s two rounds had 21 and 23 participants, respectively. No standard definition was broadly accepted or known. Evidence on associated risk factors was impacted by methodological limitations and recommendations were inconsistent. Agreement was reached on defining HAI in HHC as any infection specifically linked with providing care that develops in a patient receiving HHC from a professional healthcare worker and occurs ≥ 48 hours after starting HHC. Risk factors were hand hygiene, untrained patients and caregivers, patients’ hygiene and presence and management of invasive devices. Agreed recommendations were to adapt and standardise existing IPC guidelines to HHC and to perform a national point prevalence study to measure the burden of HAI in HHC.

Conclusions

This study offers an overview of available evidence and field knowledge of HAI in HHC. It provides a framework for a prevalence study, future monitoring policies and guidelines on IPC in Belgium.

Keywords: Healthcare-associated infections, home care, home healthcare, surveillance, infection prevention and control, HAI, ICP, recommendations

Introduction

In an ageing society, where the prevalence of chronic diseases is increasing and leading to new, advanced and often complex medical treatments, demand for healthcare is constantly rising. Considered the most frequent adverse event (AE) in healthcare delivery worldwide [1], healthcare-associated infections (HAI) are a public health threat. The burden of HAI is considerable, including not only mortality and morbidity, but also financial and socio-economic costs due to increased length of hospitalisation; additional need for diagnostics, treatments and rehabilitation of infected patients; and loss of productivity and quality of life [2-4]. HAI have therefore become a priority in many countries’ political health agendas [5]. However, as highlighted by the World Health Organization (WHO), while the focus is often on inpatient settings, no healthcare setting is exempt from the risk of HAI.

In Belgium, as in other European and western countries, a considerable shift from inpatient care, provided in hospitals, to outpatient care, including home healthcare (HHC), has been observed in recent years [6,7]. HHC is defined as care provided by professionals to a person at their own home and covers a wide range of activities, from regular routine check-up visits to end-of-life care [8]. In Belgium, HHC is prescribed by a medical doctor in a hospital, a private practice or other health facility and is provided to the patient by a general practitioner, private nurses or other healthcare workers (e.g. physiotherapist) who are either self-employed or employed by an organisation dedicated to providing HHC. Regardless of the provider, if prescribed, HHC is reimbursed by the Belgian health insurance system. The number of patients receiving HHC services has been increasing and is expected to continue to increase. While healthy, elderly patients have always received regular routine care at home, ill patients receiving more complex care are now increasingly transferred to their homes, with the hope of gaining quality of life and reducing healthcare costs [9,10]. However, receiving care at home poses new challenges and exposes patients to other risks, including HAI.

In recent decades, awareness of HAI has led to extensive research worldwide, which has identified risk factors and proposed measures and interventions to prevent or mitigate the consequences of HAI in inpatient care [11-14]; however, studies on HAI in HHC remain scarce. At present, most of the knowledge used in infection prevention and control (IPC) practice in HHC originates from the evidence collected in hospitals. In Belgium, there are currently several national surveillance systems for HAI in hospital setting [15]. In 2017, it was estimated that 7% of patients admitted to hospital contracted a HAI [16]. However, data on HAI for HHC are missing, as are specific IPC guidelines and measures.

This study aimed to conduct a conceptual analysis of HAI in HHC, with the following objectives: (i) develop a definition for HAI in HHC, (ii) identify specific risk factors for HAI acquisition in HHC settings and (iii) develop a standardised framework for prevention and control of HAI in HHC in Belgium.

Methods

Study design

To address the study objectives, we performed a scoping literature review, in-depth interviews and a two-round Delphi survey.

The scoping literature review included peer-reviewed papers and grey literature written in English, Dutch, French, German, Italian and Spanish, conducted on patients receiving HHC, published in high-income countries after 1999 and relevant to at least one of the three aspects defined in the study objectives. We used PubMed, Embase, Science Direct, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature and Cochrane Library to search for peer-reviewed papers, and Google Scholar, Open Grey, the Networked Digital Library of theses and Dissertations, and Grey Literature Report to find grey literature. We screened the websites of WHO, the United States (US) Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), the Belgian Healthcare Knowledge Centre and the Belgian Superior Health Council and conducted hand searching of references to identify relevant cross citations. The search strategy and exact strings used are presented in Supplement I.

We conducted in-depth interviews with key informants in Belgium, including healthcare professionals who were carrying out home visits or were involved in healthcare policy, HHC management or projects on hospitalisation at home. Key informants were selected using the purposive sampling method [17]. To guide the identification and selection of eligible key informants, we developed an overview of different profiles we wanted to target (Supplement II). We qualified these profiles based on their function or job title and their work experience. It was important to include individuals who were familiar with organisational, management and/or policy concepts regarding HHC and HAI so that they would be able to address the study objectives. Key informants were selected from all three Belgian regions: Brussels-capital, Flanders and Wallonia. We aimed to conduct a total of 30 interviews; however, this number could be lowered during the study if the information being collected was no longer adding new insights. Two of the study researchers (ED and LM) conducted recruitment and interviewed key informants, starting with individuals they already knew through their networks. Additional participants were recommended by this first group (snowball effect) or by colleagues, and others were identified though web-based searches performed using keywords such as ‘HHC in Belgium’, ‘hospitalisation at home projects’ and names of Belgian organisations providing HHC. An interview guide was developed and used during the interviews (Supplement III).

The Delphi survey consisted of two rounds. The first questionnaire was developed based on the results of the scoping review and the in-depth interviews, while the second was based on the results of the first round (Supplement IV). The Delphi survey was conducted online, using LimeSurvey, and targeted the same key informants as the in-depth interviews.

Data collection and analysis

For the scoping literature review, predetermined relevant characteristics of the selected articles were extracted and a self-developed quality assessment tool was used to evaluate them (Table 1).

Table 1. Evaluation criteria for quality assessment and scoring for each article included in the study.

| Characteristics | Evaluation criteria and scoring |

|---|---|

| Study information |

Study type

+ + + experimental study/literature review + + observational study + expert opinion/essay |

|

Setting

+ + + study conducted in Belgium + + study conducted in Europe + study was not conducted in a high-income countrya | |

|

Population

+ + + all age groups + + only children/elderly + undefined | |

| Source of infection |

Possible infection sites, as defined by ECDC [

47

]

+ + + HAI in HHC + + presumed HAI in HHC + mixed source − undefined source |

| Contents and findings |

Definition of HAI in HHC

+ + + provides definition + + uses accepted recognised definition (guidelines) + uses accepted definition (literature: peers) − no definition provided |

|

Risk factors of HAI in HHC

+ + + identifies risk factors + + lists risk factors + mentions risk factors − no risk factors provided | |

|

Recommendations for IPC

+ + + identifies recommendations + + lists recommendations + mentions recommendations − no recommendations provided |

HAI: healthcare associated infection; HHC: home healthcare; IPC: infection prevention and control.

a Using World Bank criteria: https://data.worldbank.org/country/XD.

We attributed a score for each characteristic based on relevance to the study objectives ( + + +: matches completely/is completely fulfilled; + +: matches partially/partly fulfilled; +: matches incompletely but sufficiently/is only partly but sufficiently fulfilled; −: does not match or matches insufficiently/is insufficiently fulfilled; c.b.e.: cannot be evaluated).

The characteristics to be evaluated were selected based on information the researchers considered relevant to the study objectives, and a scoring system was agreed upon. The articles with characteristics that scored higher were considered more appropriate for the purposes of the study and their results contributed more to the summary of the findings.

In-depth interviews were conducted by phone (by ED and LM), in the participants’ native languages, in January and February 2019. They were audio recorded and interview notes were taken. For the data analysis we used the deductive framework approach, in which the research objectives are used to group the data and then look for similarities and differences [18,19]. Immediately after the interviews were conducted, the data were grouped by the following themes: (i) the interviewees’ knowledge of definitions and prevalence, (ii) notification to healthcare authorities, (iii) risk factors, (iv) IPC management and measures and (v) availability of IPC guidelines, all of which were in the context of HAI in HHC.

The Delphi survey was conducted in March and April 2019. Level of agreement was measured and calculated using a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly disagree/very low importance”) to 4 (“Strongly agree/very high importance”), as well as the option “I don’t know”. Consensus was defined as a minimum of 80% of the respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing (Likert scale 3 and 4) with the statement. The “I don’t know” answers were excluded from the calculation and did not contribute to the denominator of the consensus percentage. Among the statements that achieved consensus, the mean was calculated and used to determine the level of importance. Statements for which consensus was reached in the first round of the survey were excluded from the second round. If contradictory statements achieved consensus in the first round, or if no consensus was reached, the statement was assessed again in the second round. For risk factors only, even statements for which consensus was reached in the first round were further assessed in the second round in order to identify the five most necessary and five most feasible to act on.

The key informants selected to participate in the Delphi survey received the invitation to participate through an email that included a link to the questionnaire. Participation was voluntary and anonymous; therefore, we only collected information about area of work, years of expertise and knowledge of the topic from those who participated.

Data analysis was performed with STATA 14.

Ethical statement

We did not need ethical approval for the implementation of this study. Written informed consent was obtained from all key informants before enrolment in the in-depth interviews. Participation in the interview was voluntary and confidentiality of the interviewees was protected and guaranteed. The Delphi survey was voluntary and anonymous.

Results

Scoping literature review

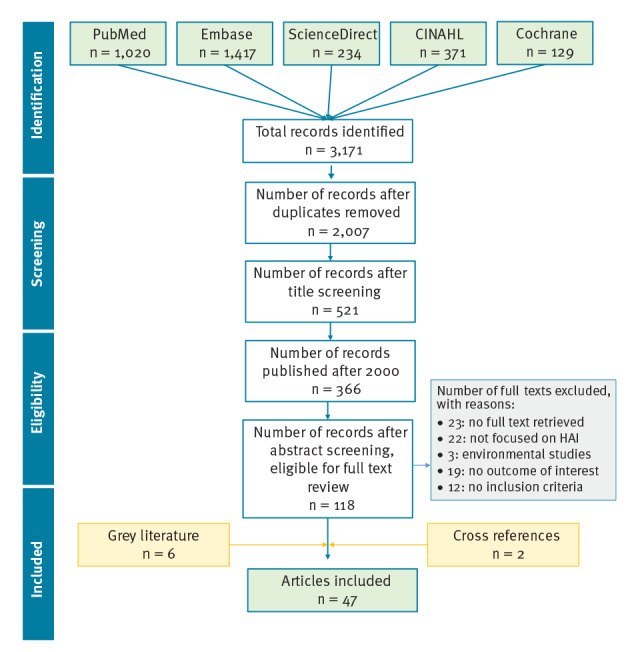

The search strategy, run on 30 October 2018, identified 3,171 peer-reviewed articles and six grey literature publications, from which 47 met the study inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Thirteen publications were articles written by experts that presented the state of the art or discussed best practices or guidelines, four were official guidelines and one was a draft of definitions for a surveillance system. The remaining 29 publications were research articles: 13 retrospective observational investigations, seven surveys, three literature reviews, three cohort studies, two point prevalence studies (PPS) and one randomised clinical trial.

Figure.

Flow diagram of the literature search and article selection process, 30 October 2018

Cochrane: Cochrane Library; CINAHL: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature.

Among the 47 publications included in the study, 22 were from the US, 16 were from Europe, six were from Canada, one was from Hong Kong, one was from Saudi Arabia and one was not country specific and was published by WHO. Twenty-five publications focused on general unspecified HAI, or on multiple types of infection together, while 20 dealt specifically with catheter-related infections and two with ventilator-associated pneumonia. An overview of the results of the literature review is shown in Supplement V.

Characteristics of in-depth interview and Delphi survey participants

A total of 20 healthcare professionals (nurses, general practitioners, a microbiologist and a physiotherapist) and one family caregiver participated in the in-depth interviews. Eleven interviews were conducted in Dutch and 10 in French, with each lasting 19–46 min. About half of the invited candidates agreed to be interviewed and we stopped enrolling participants when saturation of information was reached. A detailed description of the participants is provided in Supplement VI.

The response rate in the first and second round of the Delphi survey was 21/43 and 23/42, respectively. The two groups had an average of 14 years and 17 years of work experience in healthcare, respectively, of which more than half was specifically in HHC. The professional activities that were most represented were IPC, HHC practice and management of an organisation offering HHC services and policymaking.

Definition of healthcare-associated infection in home healthcare

The definitions we encountered in the literature were heterogeneous. The Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) definition [20] was the one most used. The definition by Miliani et al., which combines elements of the APIC definition with ECDC case definitions for HAI in hospitals, was used in a study in France to measure the prevalence of HAI in HHC [21].

During the in-depth interviews, most of the interviewees said they had never encountered or used a specific definition of HAI in HHC. A few referred to the APIC definition.

Table 2 includes the definitions for which a consensus was reached in the first round of the Delphi survey and the final definition selected after the second round. After the two rounds, the agreed upon definition of HAI in HHC was detailed in its components and flexible to include different site infections.

Table 2. Two-round Delphi survey results on definition of healthcare-associated infections in home healthcare, by survey rounds, Belgium, April 2019.

| Definitions | Agreed and strongly agreed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 (N = 21) |

Round 2 (N = 23) |

||||

| % | n/N | % | n/N | ||

| Any infection that develops in a patient who receives HHC from a professional healthcare worker and that occurs 48 hours or later after initiating this HHC | 86 | 18/21 | 35 | 8/23 | |

| Any infection that can be specifically linked with providing care (e.g. wound infection, infection linked with the use of catheters) that develops in a patient who receives HHC from a professional healthcare worker and that occurs 48 hours or later after initiating this HHC | 90 | 18/20 | 65 | 15/23 | |

HHC: home healthcare; N: total number of participants who replied; n: number of people who selected the options “Agree” or “Strongly agree”.

Respondents reached consensus for the definition highlighted in grey in the first round of the Delphi survey and this definition was also the most selected in the second round. Responses of “I don’t know” were not included in the calculations.

Risk factors for healthcare-associated infection in home healthcare

Various risk factors emerged from the literature review; some were specific to a certain type of infection (e.g. central-line associated bloodstream infections, catheter-associated urinary tract infections), while others were more general. The methodology through which risk factors were identified varied, and included multivariable analyses on datasets of patients in HHC who developed HAI [22], literature review [23-25], environmental studies [26,27] and expert opinions [28-33]. As reported by Shang et al. in their systematic literature review of the risk factors of HAI in HHC, the identified studies are limited by small sample size and other methodological limitations, which in their case did not allow for a meta-analysis [23].

During the in-depth interviews, the vast majority of interviewees stated that risk factors for HAI at home were different than in hospital and classified them in three main categories: (i) patient’s lifestyle, living environment and socioeconomic status; (ii) patient’s characteristics and pathology; and (iii) the care provided.

Several risk factors were selected based on the literature review and in-depth interview findings and were presented in the Delphi survey. Respondents agreed that an action to control risk factors is needed and feasible for the following: hand hygiene, patients’ personal hygiene, training of patients and caregivers about measures to prevent HAI in HHC and presence and management of invasive devices (Table 3).

Table 3. Two-round Delphi survey results on risk factors for healthcare-associated infections in home healthcare, by survey round, Belgium, March and April 2019.

| List of risk factors | Round 1 (N = 21) |

Round 2 (N = 23) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreed and strongly agreed | Most necessary to act on | Most feasible to act on | ||

| % | n/N | n | n | |

| Patient’s personal hygiene | 100 | 20/20 | 15 | 15 |

| Home hygiene | 75 | 15/20 | NA | NA |

| Home infrastructure (presence of sanitations, soap) | 100 | 20/20 | 11 | 10 |

| Presence of pet in the home environment | 63 | 12/19 | NA | NA |

| Education level of the patient | 74 | 14/19 | NA | NA |

| Presence of caregiver(s) in the household | 63 | 12/19 | NA | NA |

| Socio-economic status of the patient | 84 | 16/19 | 3 | 1 |

| Training of patient and caregiver(s) about the measures to prevent HAI in HHC | 95 | 18/19 | 16 | 15 |

| Patient’s age | 81 | 17/21 | 0 | 1 |

| Patient’s sex | 14 | 3/21 | NA | NA |

| Underlying health condition(s) of the patient | 100 | 21/21 | 4 | 1 |

| Medical condition for which HHC was indicated | 95 | 19/20 | 1 | 1 |

| Presence of invasive devices | 100 | 21/21 | 14 | 6 |

| Duration of the presence of invasive devices | 100 | 21/21 | 11 | 10 |

| Duration of HHC | 81 | 17/21 | 0 | 2 |

| Hand hygiene of Healthcare provider | 95 | 19/20 | 16 | 18 |

| Management of invasive devices by the healthcare provider | 100 | 20/20 | 11 | 16 |

| Frequency of visits by the healthcare provider | 90 | 18/20 | 1 | 4 |

| Lack of time by the healthcare provider during the visit | 80 | 16/20 | 7 | 6 |

| Communication between different care providers | 74 | 14/19 | NA | NA |

HAI: healthcare-associated infection; HHC: home healthcare; N: total number of participants that replied; n: number of people who selected the options ”Agree” or “Strongly agree”; NA: not applicable, as this statement/question was not asked in the second round because consensus was not reached (≥ 80% agreement) in the first round.

Respondents reached consensus in the first round for the risk factors highlighted in grey; four more selected in the second round are also highlighted. In the second round, participants could select five answers for the most necessary and the most feasible to act on. Responses of “I don’t know” were not included in the calculations.

Measures and guidelines to prevent healthcare-associated infection in home healthcare

The vast majority of the studies included in the literature review (43/47) provided some kind of recommendations, focusing either on prevention and control of HAI in HHC or more broadly on the improvement of the standardisation, reporting and benchmarking of HAI in HHC across different countries. Several studies highlighted the need to raise awareness of HAI in HHC among patients and their caregivers, as well as to empower and train patients and caregivers on the measures and practices that can contribute to safe and HAI-free HHC [21,23,34-36].

Interviewees mentioned that the basic principles of IPC for HAI in hospitals and HHC were the same; nevertheless, their implementation in the home setting appears to be more challenging. The management of HAI in HHC is generally neglected compared with HAI prevention and control in hospitals and nursing homes, and the people working in the field of HHC feel the lack of general standardised guidelines.

In the first round of the Delphi survey, respondents reached consensus for all of the suggested measures to prevent and control HAI in HHC. In particular, all respondents agreed on the need for standardised IPC guidelines for HHC, available and accessible to all staff involved in HHC, with room for adaptation to the local context. As shown in Table 4, in the second round of the survey, a vast majority of respondents indicated that existing national and international accepted IPC guidelines for HAI and for specific technical procedures can be used in HHC, as long as adaptation to the home setting—when needed—was encouraged and possible.

Table 4. Second round of two-round Delphi survey results on measures to prevent and control healthcare-associated infection in home healthcare, Belgium, April 2019.

| Statements | Agreed and strongly agreed (N = 23) |

|

|---|---|---|

| % | n/N | |

| Existing national and international accepted IPC guidelines for HAI (e.g. WHO guidelines on hand hygiene) can be used in HHC without adaptation | 32 | 6/19 |

| Existing national and international accepted IPC guidelines for HAI (e.g. WHO guidelines on hand hygiene) can be used in HHC, but need to be adapted to the home setting when needed | 95 | 19/20 |

| Existing national and international accepted IPC guidelines for HAI (e.g. WHO guidelines on hand hygiene) cannot be used in HHC, which requires specific guidelines | 24 | 4/17 |

| Existing national and international guidelines for specific technical procedures (e.g. hospital guidelines for preventing central line-associated bloodstream infection) can be used in HHC without adaptation | 26 | 5/19 |

| Existing national and international guidelines for specific technical procedures (e.g. hospital guidelines for preventing central line-associated bloodstream infections) can be used in HHC, but need to be adapted to the home setting when needed | 90 | 17/19 |

| Existing national and international guidelines for specific technical procedures (e.g. hospital guidelines for preventing central line-associated bloodstream infections) cannot be used in HHC, which requires specific guidelines | 31 | 5/16 |

HAI: healthcare-associated infection; HHC: home healthcare; IPC: infection prevention and control; N: number of total participants who replied; n: number of people who selected the options “Agree” or “Strongly agree”; WHO: World Health Organization.

Respondents reached consensus (≥ 80% agreement) for all statements in the first round. Statements highlighted in grey are the measures that reached consensus in the second round. Responses of “I don’t know” were not included in the calculations.

Discussion

Based on the findings of this study, the definition of HAI in HHC should contain three main components: the specific link to care, the presence of a professional healthcare provider and occurrence at least 48 hours after HHC began (Table 2). The Delphi survey respondents agreed that hand hygiene, patients’ personal hygiene, training of patients and caregivers and the presence of invasive devices are risk factors for which action is necessary and feasible (Table 3). They also agreed that existing guidelines for IPC in hospital settings can and should be adapted to the specific home setting (Table 4).

The lack of a broadly accepted definition of HAI in HHC is currently the main barrier to compiling and standardising the available evidence, and our work highlights that this lack, which has been previously reported in the US [37], is also experienced by individuals working in the field in Belgium. In our opinion, this definition gap could be filled if one of the previously used definitions [20,21], together with our study results, was endorsed by an international institution such as the WHO.

Most of the information regarding risk factors for developing HAI comes from studies conducted in hospital settings, and the few studies done in homes are not consistent enough to establish robust and reproducible evidence. Previous efforts [23] and our review were not successful in identifying conclusive risk factors in the literature. Equally, our interviews highlighted an inconsistent level of awareness of risk factors for HAI in HHC among individuals working in the field. Nevertheless, most of them were aware of the general WHO guidelines on hand hygiene [38] and recognised their importance in IPC. We reached agreement on four main potential risk factors, which need to be further investigated by a study with the appropriate design and sample size.

Due to limitations in definition and risk factors, international recommendations for best practices are missing. Most published recommendations focus on ideas to initiate surveillance systems measuring infection and AE occurring in HHC, as well as to standardise indicators so that benchmarking is possible and best practices can be highlighted and implemented [39-43]. Recently, the Dutch National Institute of Public Health and the Environment published some practical and pragmatic guidelines on hygiene in home care in order to prevent HAI [44]. Given the difficulties of having better studies in the short term, we think that the empirical adaptation of hospital guidelines for IPC would be useful to all the healthcare staff working in HHC, as well as family caregivers.

A few limitations might have impacted the results of our study. First, we did not perform a systematic review of the literature, as the scoping approach allowed more flexibility in the selection process and in the evaluation of the quality of the selected publications. Second, we excluded publications before the year 2000, which we found to be outdated in regards to our research topic, and were more often discursive rather than observational or experimental studies (data not shown). Third, selection bias might have been introduced in the in-depth interviews and the Delphi survey, as participation was on a voluntary basis and might not be representative of all healthcare professionals working with HAI in HHC. Further, some participants were known and selected by two of the study researchers (ED and LM) who work in HAI surveillance in Belgian; however, we considered their network to be quite representative of the HHC professionals working in the area. More specifically, we lacked participation of academics. Finally, the number of participants in the interviews and the Delphi survey was relatively limited. However, the interviews were conducted until we reached saturation of information, and the voluntary participation in the first round of the Delphi survey was around 50% and stayed almost stable in the second round.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that attempts to disentangle various aspects of HAI in HHC in Belgium. We tackled the issue from different perspectives (literature review, qualitative interviews and quantitative survey) in order to compile a wide range of information and we strongly believe that it serves as valid ground for harmonised work and further research in order to guarantee quality across the continuum of healthcare.

To better understand the dynamics of HAI in HHC in Belgium, and to address the knowledge gaps identified, it appears necessary to conduct a national PPS that covers the whole country and uses the proposed definition. We suggest that it be conducted as an independent investigation, coordinated by a study group who could refer to the ECDC protocols of HAI in acute care hospitals [45] and HAI in European long-term care facilities [46], as well as to the French PPS on HAI in HHC reported by Miliani et al. [21].

Additionally, we suggest the development of specific recommendations and guidelines regarding the prevention and control of HAI in HHC at the national level. The drafting of these guidelines could be coordinated and written by the Belgian Superior Health Council, who could use existing national and international guidelines (e.g. WHO guidelines on hand hygiene) and empirically adapt these to the HHC context.

Our study refers mainly to Belgium, but we are aware that several HHC realities across Europe are similar to what we observed. The study recommendations—for a standardised definition of HAI in HHC and adaptation of ICP guidelines—can therefore be applicable to other countries as well. In order to harmonise definitions and practices surrounding HAI in HHC and support individual countries in dealing with the complexity of this topic, institutions such as ECDC could contribute by promoting collaboration towards a standardised definition and agreement on common ICP guidelines to use across Europe.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the King Boudewijn Foundation.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of Sciensano, the Belgian Public Health Institute.

AH was a fellow in the European Programme for Intervention Epidemiology Training, funded by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, while working on this project. We have received valuable comments to the manuscript from Dr. Sooria Balasegaram

Supplementary Data

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Author’s contribution: LM and ED designed the study and wrote the protocol, conducted the in-depth interviews and provided feedback for the Delphi survey content. AH and LM conducted the literature review. AH prepared the online survey, analysed the survey results and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

References

- 1.World health Organization (WHO). Health care-associated infections FACT SHEET. Geneva: WHO. [Accessed: 2 Feb 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/gpsc/country_work/gpsc_ccisc_fact_sheet_en.pdf

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO). Report on the Burden of Endemic Health Care-Associated Infection Worldwide. Geneva: WHO; 2011. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/80135/9789241501507_eng.pdf

- 3. Cassini A, Plachouras D, Eckmanns T, Abu Sin M, Blank HP, Ducomble T, et al. Burden of Six Healthcare-Associated Infections on European Population Health: Estimating Incidence-Based Disability-Adjusted Life Years through a Population Prevalence-Based Modelling Study. PLoS Med. 2016;13(10):e1002150. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vrijens F, Renard F, Jonckheer P, Van den Heede K, Desomer A, Van de Voorde C, et al. The Belgian Health System Performance Report 2012: snapshot of results and recommendations to policy makers. Health Policy. 2013;112(1-2):133-40. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guirao BM, Nicols X, Petrosillo J, Mimoz N, Optimising O. Skin antisepsis for an enhanced prevention of healthcare-associated infections in the EU. European policy recommandations. Brussels: European policy recommendations; 2018. Available from: https://gavecelt.it/nuovo/sites/default/files/uploads/SKIN%20ANTISEPSIS%20-%20EU%20Recommendations.pdf

- 6. Beans BE. Experts Foresee a Major Shift From Inpatient to Ambulatory Care ASHP: Experts Foresee a Major Shift From Inpatient to Ambulatory Care. P&T. 2019;41(4). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Insights D. Growth in outpatient care. London: Deloitte; 2018. Available from: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/insights/us/articles/4170_Outpatient-growth-patterns/DI_Patterns-of-outpatient-growth.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thomé B, Dykes A-K, Hallberg IR. Home care with regard to definition, care recipients, content and outcome: systematic literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12(6):860-72. 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00803.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Landers S, Madigan E, Leff B, Rosati RJ, McCann BA, Hornbake R, et al. The Future of Home Health Care: A Strategic Framework for Optimizing Value. Home Health Care Manage Pract. 2016;28(4):262-78. 10.1177/1084822316666368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eurostat. 1 in 5 households in need in the EU use professional homecare services. Brussels Eurostat; 2018. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/DDN-20180228-1?inheritRedirect=true&

- 11.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Healthcare-associated infections in intensive care units. ECDC Annual Epidemiological Report for 2017. Stockholm: ECDC; 2019. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/AER_for_2017-HAI.pdf

- 12.World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines on Prevention and Control of Hospital Associated Infections. Geneva: WHO; 2002.Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/205187/B0007.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- 13.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Healthcare-associated infections: prevention and control in primary and community care. London: NICE guideline; 2014.Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg139 [PubMed]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Core Infection Prevention and Control Practices for Safe Healthcare Delivery in All Settings – Recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Atlanta: CDC; 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/recommendations/core-practices.html

- 15.Sciensano. Healthcare-Associated Infections & Antimicrobial Resistance - Belgium. Brussels: Sciensano; 2019. Available from: http://www.nsih.be/contact/contact_en.asp.

- 16.Vandael E, Latour K, Goossens H. Magerman K,Drapier N, Catry B, et al. Point prevalence survey of antimicrobial use and healthcare-associated infections in Belgian acute care hospitals: results of the Global-PPS and ECDC-PPS 2017. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020:13;9(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Mack E, Woodsong N, MacQueen C, Guest KM, Namey G. Qualitative Research Methods: A Data Collector’s Field Guide. North Carolina: Family Health International; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(117):117. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320(7227):114-6. 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.APIC, Embry F, Chinnes L. APIC - HICPAC Surveillance Definitions for Home Health Care and Home Hospice Infections. Baltimore: APIC; 2008. Available from: https://apic.org/Resource_/TinyMceFileManager/Practice_Guidance/HH-Surv-Def.pdf

- 21. Miliani K, Migueres B, Verjat-Trannoy D, Thiolet JM, Vaux S, Astagneau P, et al. National point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use in French home care settings, May to June 2012. Euro Surveill. 2015;20(27):1-11. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2015.20.27.21182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Patte R, Drouvot V, Quenon JL, Denic L, Briand V, Patris S. Prevalence of hospital-acquired infections in a home care setting. J Hosp Infect. 2005;59(2):148-51. 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shang J, Ma C, Poghosyan L, Dowding D, Stone P. The prevalence of infections and patient risk factors in home health care: a systematic review. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(5):479-84. 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Masotti P, McColl MA, Green M. Adverse events experienced by homecare patients: a scoping review of the literature. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22(2):115-25. 10.1093/intqhc/mzq003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dreesen M, Foulon V, Spriet I, Goossens GA, Hiele M, De Pourcq L, et al. Epidemiology of catheter-related infections in adult patients receiving home parenteral nutrition: a systematic review. Clin Nutr. 2013;32(1):16-26. 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. von Baum H, Bommer M, Forke A, Holz J, Frenz P, Wellinghausen N. Is domestic tap water a risk for infections in neutropenic patients? Infection. 2010;38(3):181-6. 10.1007/s15010-010-0005-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bech LF, Drustrup L, Nygaard L, Skallerup A, Christensen LD, Vinter-Jensen L, et al. Environmental Risk Factors for Developing Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection in Home Parenteral Nutrition Patients: A 6-Year Follow-up Study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;40(7):989-94. 10.1177/0148607115579939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rhinehart E. Infection control in home care. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(2):208-11. 10.3201/eid0702.010211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McGoldrick M. Infection prevention and control. Home Healthc Nurse. 2007;25(9):557-8. 10.1097/01.NHH.0000296111.10825.f3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gorski LA. Central venous access device associated infections: recommendations for best practice in home infusion therapy. Home Healthc Nurse. 2010;28(4):221-9. 10.1097/NHH.0b013e3181d6c3ad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Manangan LP, Pearson ML, Tokars JI, Miller E, Jarvis WR. Feasibility of national surveillance of health-care-associated infections in home-care settings. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(3):233-6. 10.3201/eid0803.010098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Morrison J, Health Canada, Nosocomial and Occupational Infections Section Development of a resource model for infection prevention and control programs in acute, long term, and home care settings: conference proceedings of the Infection Prevention and Control Alliance. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32(1):2-6. 10.1016/j.ajic.2003.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shang J, Dick AW, Larson EL, Stone PW. A research agenda for infection prevention in home healthcare. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46(9):1071-3. 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gorski LA. Central venous access device associated infections: recommendations for best practice in home infusion therapy. Home Healthc Nurse. 2010;28(4):221-9. 10.1097/NHH.0b013e3181d6c3ad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McGoldrick M. Preventing infections in patients using respiratory therapy equipment in the home. Home Healthc Nurse. 2010;28(4):212-20. 10.1097/NHH.0b013e3181d6be3e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Horcajada JP, García L, Benito N, Cervera C, Sala M, Olivera A, et al. Hospitalización a domicilio especializada en enfermedades infecciosas. Experiencia de 1995 a 2002. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2007;25(7):429-36. 10.1157/13108706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Poff RM, Browning SV. Creating a meaningful infection control program: one home healthcare agency’s lessons. Home Healthc Nurse. 2014;32(3):167-71. 10.1097/NHH.0000000000000023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care: a Summary. Geneva: WHO; 2009. Available from: \xhttps://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70126/WHO_IER_PSP_2009.07_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- 39. Embry F, Chinnes L. Draft Definitions for Surveillance of Infections in Home Healthcare. Home Healthc Nurse. 2001;19(7):439-44. 10.1097/00004045-200107000-00010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Friedman MM, Rhinehart E. Improving infection control in home care: from ritual to science-based practice. Home Healthc Nurse. 2000;18(2):99-105, quiz 106. 10.1097/00004045-200002000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schantz M. Infection control comes home. Home Health Care Manage Pract. 2001;13(2):126-33. 10.1177/108482230101300207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dreesen M, Foulon V, Spriet I, Goossens GA, Hiele M, De Pourcq L, et al. Epidemiology of catheter-related infections in adult patients receiving home parenteral nutrition: a systematic review. Clin Nutr. 2013;32(1):16-26. 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kelly JJ, Chu SY, Buehler JW, AIDS Mortality Project Group AIDS deaths shift from hospital to home. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(10):1433-7. 10.2105/AJPH.83.10.1433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM). Hygiëneadviezen thuiszorg. [Hygiene Advice for home care]. Bilthoven RIVM; 2019. Dutch. Available from: https://www.rivm.nl/hygienerichtlijnen/hygieneadviezenthuiszorg

- 45.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Point prevalence survey of healthcare associated infections and antimicrobial use in European acute care hospitals 2011-2012. Stockholm: ECDC; 2013. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/media/en/publications/Publications/healthcare-associated-infections-antimicrobial-use-PPS.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use in European long-term care facilities. Stockholm: ECDC; 2013. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/media/en/publications/Publications/healthcare-associated-infections-point-prevalence-survey-long-term-care-facilities-2013.pdf

- 47.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use in European acute care hospitals – protocol version 5.3. Stockholm: ECDC; 2016. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/PPS-HAI-antimicrobial-use-EU-acute-care-hospitals-V5-3.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.