Implications

Australia as an island was able to quickly respond to a pandemic such as COVID-19 by closing international and domestic borders to reduce the introduction of COVID-19 and an introduction of lockdown procedures.

Hotel quarantine of returning travelers was very effective in reducing the introduction of COVID-19 to the community. However, breakdown in training and adequate use of PPE resulted in a second wave emanating from hotel quarantine in one jurisdiction (Melbourne), which was controlled by very strict lockdown.

Introduction of federal government support for employees form businesses impacted by COVID-19 reduced the social impacts of COVID-19 although gaps occurred.

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown resulted in some stockpiling of essential items, including meat.

During the initial lockdown when restaurants and food service were closed, there was an initial surplus of pork, in particular, premium cuts. However, ongoing lockdowns resulted in an increase in household demand for pork, particularly roasts and mince. Food service has rebounded since lockdowns were removed.

The decline in air travel and increased freight costs has reduced both exports and frozen imports of pork. The latter generally makes up a substantial proportion of processed pork products and this has been picked up by domestic production.

The Australian summer, November 2019, started with our focus on bushfires and their impacts on both regional and urban Australia, and this continued into the new year. Southern Australia bore the brunt of these ferocious bushfires with devastating consequences on many regional communities. The southern Australian major cities were also affected albeit at a very different level, with extreme smoke pollution confining much of the population indoors for a few weeks at a time. Domestic air travel in Australia was disrupted, people were forced to work from home, and, unfortunately, we also witnessed a consumer behavior that few had witnessed previously, panic buying, with items like toilet paper and face masks and commodities like long-life milk, rice, flour, and meat being stockpiled by consumers, resulting in ‘rationing’ of these items by retailers. But few foresaw what was about to confront us in 2020.

Like the rest of the world, we started seeing increasing media coverage of COVID-19 in January 2020. Some in Australia were aware of the severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus epidemic in 2003 and, more recently, the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus epidemics. Most thought the impacts of the new coronavirus would largely again be localized epidemics with few cases spread outside these regions. But all that changed as we saw this incredible spread of COVID-19 globally, resulting in Australia effectively shutting its borders to all visitors in March 2020.

The Australian pork industry, a relatively small industry by global standards with 270,000 sows, produces approximately 5.3 M slaughter pigs annually. The pork processing sectors consists of seven export-accredited sites that slaughters and processes approximately 85% of the national slaughter pigs. The Australian pork industry is unique in that it has been a closed genetic herd since late 1980s and does not allow fresh pork imports. All imported pork in Australia, mainly boneless hams and middles, must be cooked prior to sale. The Australian pork industry is spread across all Australian states with the major supply chains operating nationally.

At the start of 2020, the Australian pork industry was very much focused on African Swine Fever (ASF) and its spread across China and other parts of Asia, including Timor-Leste. As an industry, we were on high alert as numerous illegal pork products seized and destroyed by Australian authorities at airports from predominantly Asian travelers were found to contain ASF viral DNA material. Come March 2020, with its borders effectively closed and social distancing rules affecting both urban and regional Australia, we saw significant impacts of COVID-19 on the pork industry. For starters, the risk posed by visitors bringing in ASF via contaminated pork products was significantly diminished by the COVID-19 border closures.

Australia’s response to COVID-19 was rapid with the closure of international borders and mandatory hotel quarantining for returning travelers. Non-essential workers worked from home from mid-March and various levels of lockdown were introduced across the country. By global standards, Australia had very low rates of infection during the first wave and appeared to have things well under control in May 2020. However, a second wave arose primarily in Victoria when COVID-19 escaped from the quarantine hotels as a consequence of quarantine breaches. This second wave appears to have been controlled and, on 26 October 2020, there were zero cases of COVID-19 in the state of Victoria from approximately 15,000 tests performed in the previous 24 h.

One of the immediate impacts as a consequence of COVID-19 social distancing was the decline in the domestic food service pork volumes. Data from Australian Pork Limited’s foodservice tracker, which gauges Australian consumer activity, shows the percentage of people eating out of home—for either lunch or dinner on a given day—dropped from around 29% before March to as low as 16% in April. Surprisingly, the food service industry has rebounded back strongly to 27% for August 2020. While some of this can be attributed to the easing of some of the COVID-19 social distancing restrictions, much of this has come about with many restaurants reconfiguring their business from dine-in venues to take-away meal service only.

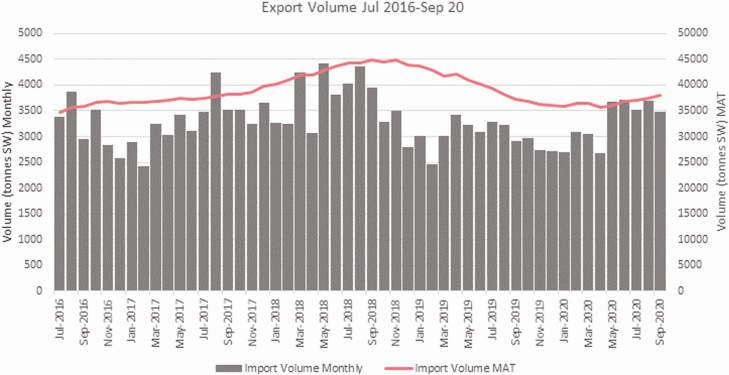

The border closure in March 2020 and the subsequent decline in air travel resulted in increased airfreight costs (>200%) to service our chilled carcass export markets in Singapore and Hong Kong. Freight volumes to Singapore and Hong Kong were marginally affected in April 2020 but have since recovered (Figure 1). While there was some Federal Government support for airfreight, this was insufficient to fully support the increased costs and the reduced options for air cargo.

Figure 1.

Monthly and moving annual total (MAT) volume of Australian pork exports. https://mcusercontent.com/1b0b935b82a4a431aaf5b157a/files/d07fe009-5c22-41b3-a22f-ea6e0198bacd/Import_Export_Jul_Report.pdf.

Accompanied by these market shifts, we saw domestic retail trade increase markedly with consumers again resorting to panic buying. Interestingly, the latest data confirm Australian pork year-on-year growth of 20.6% in volume and 27.5% in value (http://porknews.com.au/documents/pasteditions/APN1020.pdf). This has been driven by household demand, especially for roast pork and mince, and helped by the increase in Australian pork being sourced for small goods. Retail fresh pork also remains competitively priced compared to other animal protein options.

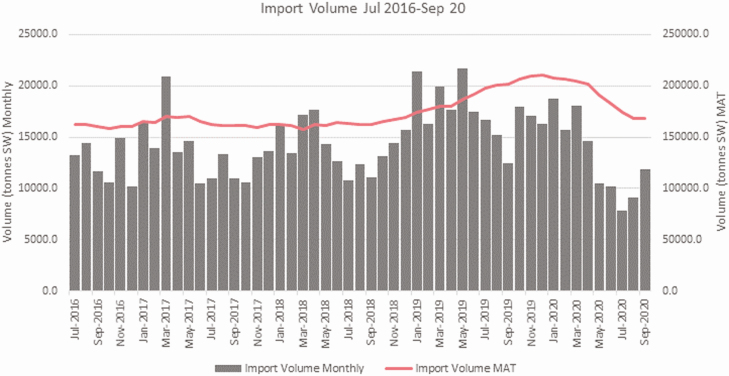

The Australian Bureau of Statistics shows that pork imports to Australia have dropped significantly (Figure 2). The pork vacuum created by African swine fever across global markets has seen large volumes of European Union and North American pork being directed away from Australia.

Figure 2.

Monthly and moving annual total (MAT) volume of Australian pork imports. https://mcusercontent.com/1b0b935b82a4a431aaf5b157a/files/d07fe009-5c22-41b3-a22f-ea6e0198bacd/Import_Export_Jul_Report.pdf.

Pig production in Australia, like many other countries, relies on foreign labor and with border closures in Australia and both the Philippines and New Zealand has seen a significant labor shortage and numerous vacancies for on-farm jobs. This is likely to continue until at least March 2021. Within Australia, state border closures have had some impact on the supply of both breeding animals and semen delivery. In most instances, these impacts have been easily overcome with the transfer of animals and semen at border transition sites but have resulted in increased distribution costs. The supply of feed ingredients similarly has not experienced significant delays, but we have again seen the freight costs of these ingredients increase.

Thankfully, we have not had to euthanize any pigs as a consequence of slaughter and processing facilities closures due to COVID-19. To date, only one of Australia’s seven pork abattoir processing facilities have had to close their facilities due to workers testing positive, and this was for a few weeks. However, there were at least two red meat processors who had outbreaks of COVID-19 in Victoria (see below). The livestock processing sectors in Australia were very proactive in developing and implementing their COVID-19 management plans. The costs, however, to maintain business continuity has come at a significant price, with some of the larger pork processing facilities with over 800 workers across multiple shifts reporting increased costs in the vicinity of AUS$700,000 (personal communication). The Australian Federal Government introduced a Jobkeeper program (https://www.ato.gov.au/general/jobkeeper-payment/) that allowed companies that had experienced a substantial decrease in income to keep staff on the payroll through a Government grant and this greatly assisted some of the meat processors impacted. The Government also increased (doubling in some cases) the Jobseeker payments for people seeking work (https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/individuals/services/centrelink/jobseeker-payment). While these initiatives were largely successful and certainly assisted many people across the community, there were some unintended consequences. For example, some processors and other agricultural industries were sometimes unable to fill unskilled positions because the magnitude of the benefits was a disincentive to work for some people.

Some states and territories of Australia have been very successful in quashing COVID-19 with the strategy often relying on tight border closures both internationally and between states. This has presented issues for staffing in particular for those processors and businesses located close to the border. Another possible consequence as we enter hay and grain harvesting season is the possibility that harvesting contractors who often move south with the season may not be able to cross some state borders. It is envisaged that there will be some relaxation of borders to minimize these impacts. Another concern for the agricultural sector in general is that many of the labor-intensive jobs, such as fruit picking, are traditionally performed by backpackers. With the closure of international borders, it is unknown who will perform these jobs.

While social distancing restrictions in most Australian states are easing, the Australian pork industry continues to keep its COVID-19 management plans active and in place. However, the second most populous state Victoria, particularly metropolitan Melbourne, experienced a second wave of COVID-19 with 99% of the infections being traced back to security breaches in hotels where incoming travelers returning from overseas were required to quarantine for 14 days. Victoria, unlike other jurisdictions, used private security contractors with inadequate training in infection control and the use of PPE. Unfortunately, these contractors often worked more than one job and lived in large households with other workers, including some in the meat processing and food distribution sectors, as well as the aged care sector. Reluctance to be tested and enter isolation until test results were received and concerns about not being able to work further increased the spread of COVID-19 in Victoria. As a consequence, the Victorian State Government has implemented strict lockdown protocols in an attempt to control this spread, which still remains in place up until late October. The meat processing sector in Victoria were forced to operate at approximately 70% of normal capacity for about 2 months and will not be back to full capacity until at least November 2020.

One of the other consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and border closures is that many aspects of research and development have been heavily affected both on farm and at the processor level. Collaborative national research and development programs, particularly those focused on red meat and pork eating and carcass quality have been seriously delayed and will continue to be delayed well into 2021. Other research that relies on the sourcing of abattoir materials, such as embryos or rumen fluid and possibly tissues, for biomedical research have been hampered by tight biosecurity within abattoirs.

Unfortunately, the increase in the second and third wave human infections globally will likely see the industry implement these plans for the rest of 2020. To date, 2020 has been a difficult year for the Australian pork industry but the industry can be well pleased with its effort and its resilience in the face of a devastating COVID-19 pandemic.

About the Authors

Darryl D’Souza is the Executive General Manager, SunPork Solutions. SunPork Solutions is the technical service provider of R&D, training, benchmarking, and decision support services to the SunPork Group (pork integrator). In addition, Darryl also provides line management to the SunPork Group Quality Systems Manager and the General Manager PIC Australia. Prior to SunPork Solutions, Darryl was the General Manager, Research & Innovation with Australian Pork Limited, the producer-owned organization supporting and promoting the Australian Pork industry and the Program Leader with the Cooperative Research Centre for High Integrity Pork. Darryl completed his PhD at the University of Melbourne in 1998 and is a Meat Scientist with over 20 years of experience and has led a number of research programs that have contributed to the Australian Pork Industry’s Eating Quality Program. Darryl has held technical positions with Alltech Biotechnology P/L and the Craig Mostyn Group (Pork Division) and government research positions in Western Australia and Victoria in Australia.

Frank Dunshea is a Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor and Chair of Agriculture at the University of Melbourne in Australia and Professor of Animal Growth and Development at the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom. Frank has a more than 35-yr research career in the area of growth physiology and nutrition and the use of domestic animals in nutritional and biomedical research. He has published over 900 journal, conference, book, or technical articles. His research has had a high scientific impact, with many of the results being rapidly adopted by industry. Frank is a respected research leader in global livestock industries and is committed to ensuring that livestock industries operate in a responsible and sustainable manner. Much of his work has focused on improving efficiency through reducing inputs and outputs while maintaining product quality and consumer health with a particular emphasis on meat quality. In addition to many awards, Frank is a Fellow of the Australian Nutrition Society, the Australasian Pig Science Association, and the Australian Association of Animal Sciences.