Abstract

Background

The effects of sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) on anaerobic and aerobic capacity are commonly acknowledged as unclear due to the contrasting evidence thus, the present study analyzes the contribution of NaHCO3 to energy metabolism during exercise.

Methods

Following a search through five databases, 17 studies were found to meet the inclusion criteria. Meta-analyses of standardized mean differences (SMDs) were performed using a random-effects model to determine the effects of NaHCO3 supplementation on energy metabolism. Subgroup meta-analyses were conducted for the anaerobic-based exercise (assessed by changes in pH, bicarbonate ion [HCO3−], base excess [BE] and blood lactate [BLa]) vs. aerobic-based exercise (assessed by changes in oxygen uptake [VO2], carbon dioxide production [VCO2], partial pressure of oxygen [PO2] and partial pressure of carbon dioxide [PCO2]).

Results

The meta-analysis indicated that NaHCO3 ingestion improves pH (SMD = 1.38, 95% CI: 0.97 to 1.79, P < 0.001; I2 = 69%), HCO3− (SMD = 1.63, 95% CI: 1.10 to 2.17, P < 0.001; I2 = 80%), BE (SMD = 1.67, 95% CI: 1.16 to 2.19, P < 0.001, I2 = 77%), BLa (SMD = 0.72, 95% CI: 0.34 to 1.11, P < 0.001, I2 = 68%) and PCO2 (SMD = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.13 to 0.90, P = 0.009, I2 = 0%) but there were no differences between VO2, VCO2 and PO2 compared with the placebo condition.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis has found that the anaerobic metabolism system (AnMS), especially the glycolytic but not the oxidative system during exercise is affected by ingestion of NaHCO3. The ideal way is to ingest it is in a gelatin capsule in the acute mode and to use a dose of 0.3 g•kg− 1 body mass of NaHCO3 90 min before the exercise in which energy is supplied by the glycolytic system.

Keywords: Sodium bicarbonate; Energy metabolism, exercise; Aerobic-based; Anaerobic-based

Background

Energy supply is an important prerequisite for maintaining exercise, in which fat, carbohydrate (glucose) and protein are converted into adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to provide energy for the body. Energy output from human movement is divided between anaerobic and aerobic energy supply systems. The anaerobic systems are the phosphagen system and glycolytic system, which synthesize ATP without oxygen participation. The energy supply substrates of the phosphagen system are ATP and creatine phosphate (CP or phosphocreatine [PCr]), also called the ATP-CP system. ATP-CP participates in energy supply directly, which is the fastest but also shortest way to maintain the duration of the energy supply. The energy substrate of the glycolytic system is glucose, which synthesizes ATP by decomposing glucose. The process by which the body decomposes a substrate under aerobic conditions is called intracellular respiration. This process requires the participation of oxygen, and is called the oxidative system. The mitochondria in the cells are the organs that produce ATP by glucose, fat and protein oxidation, and at the same time, the cardiovascular and respiratory systems need to transport large amounts of oxygen to the muscles for their needs [1], (Table 1).

Table 1.

The basic characteristics of the three energy supply systems

| Name of energy supply system |

Energy substrate | Available exercise time |

Supply substances and metabolites for ATP recovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATP-CP | ATP | 6 ~ 8 s | CP |

| CP | < 10s | CP + ADP → ATP + C | |

| Glycolytic system | Glucose | 2 ~ 3 min | Glucose → Lactic acid |

| Oxidative system | Glucose | 3 ~ 5 min | Glucose → CO2 + H2O |

| Fat | 1 ~ 2 h | Fat → CO2 + H2O |

In exercise physiology the interconnection between the energy required to complete different types of exercise and the ways supplied by each energy system together is referred to as the Continuous unity of energy (CUE) [2]. It describes the corresponding overall relationship between different movements and different energy supply paths of the energy system (Unity of sport and energy supply). The CUE is generally expressed as the percentage of aerobic and anaerobic energy supplied. According to the ratio of anaerobic and aerobic energy supplied for different sports, the relative positions of various sports in the CUE can be determined and the sport can be understood by what is the leading energy supply system.

The ratio of the anaerobic and aerobic energy supply is determined by exercise intensity. The ATP-CP system mainly provides energy for high-intensity short-term exercise (i.e., sprinting, throwing, jumping and weight lifting); the glycolytic system mainly provides energy for medium-high-intensity, short-term exercise (i.e., 400 m running and 100 m swimming) and the oxidative system mainly functions for low-medium-intensity, medium-long time exercise (i.e., long distance running, rowing and cycling), (Table 2). The energy supply capacity of different energy systems determines the strength of exercise capacity.

Table 2.

Corresponding position of sports in the CUE

| Sports | Aerobic (%) | Anaerobic (%) | Sports |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight lifting, diving, gymnastics | 0 | 100 |

100 m running, Golf and tennis swing |

|

200 m running, wrestling, Ice hockey |

10 | 90 | Soccer, basketball, baseball, |

| 20 | 80 | Volleyball, 500 m skiing, 400 m running | |

| Tennis, lawn hockey | 30 | 70 | Lacrosse |

| 800 m running, boxing | 40 | 60 |

200 m swimming, 1500 m skating |

| 50 | 50 | ||

| 2000 m rowing | 60 | 40 | 1500 m running |

|

1500 m running, 400 m swimming |

70 | 30 | 800 m swimming |

| 3000 m running | 80 | 20 | Trail running |

|

5000 m running, 10,000 m skating, 10,000 m running, marathon |

90 | 10 | Cross country skiing, jogging |

| 100 | 0 |

The ATP-CP system tells us that when ATP is used, creatine kinase decomposes PCr and simultaneously removes inorganic phosphate (Pi) to release energy during explosive activities [3]. The energy generated when decomposing PCr can combine Pi with adenosine diphosphate (ADP) to regenerate ATP, thereby maintaining the stability of ATP levels. The principle of the glycolytic system is that glycogen or glucose decomposes to form pyruvate, which becomes lactic acid in the absence of oxygen. If lactic acid is not removed in time, it will be decomposed and converted into lactate and cause a large amount of H+ accumulation, resulting in muscle acidification, causing acidosis [4].

The increase of H+ will cause decreases of pH in the body, and the destroyed acid-base balance will damage muscle contractility and hinder ATP production. In order to reduce the effect of free H+, alkaline substances in blood and muscle will combine with H+ to buffer or neutralize it [5]. In the body, there are three main chemical buffers, bicarbonate ions (HCO3−), Pi, and protein. In addition, the hemoglobin in red blood cells is also an important buffer, but a large part depends on HCO3− (see Table 3) [1]. When lactic acid is formed, the body’s fluid buffer system will increase the HCO3− in the blood to help the body quickly recover from fatigue. This process is called bicarbonate loading [6]. Sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) is a type of physiological supplement. Ingesting some substances that can increase the HCO3− in the blood, like NaHCO3, can increase the blood pH and make it more alkaline. The higher the HCO3−, the stronger the acid-base buffer provided, allowing higher concentrations of lactic acid in the blood.

Table 3.

Buffer capacity of blood components

| Buffers | Slykes* | % |

|---|---|---|

| HCO3− | 18.0 | 64 |

| Hemoglobin | 8.0 | 29 |

| Protein | 1.7 | 6 |

| Pi | 0.3 | 1 |

| Total | 28.0 | 100 |

Note: * refers to the pH value per liter of blood ranging from 7.4 to 7.0, which can neutralize the milliequivalent of H+

There are some studies showing that NaHCO3 can change the content of blood lactate (BLa), HCO3−, pH and BE [7–10] during anaerobic-based exercise. Although those parameters are affected by ingesting NaHCO3, the change of anaerobic metabolism systems (AnMS) is different. The capacity of the glycolytic system could increase [11] or stay the same [12], but the ATP-CP system seems not affected by ingestion of NaHCO3, because the ATP or PCr content is not affected by NaHCO3 [12, 13]. Due to the participation of oxygen in the process of ATP synthesis in the oxidative system, a large number of studies have shown that enhancing oxygen uptake and the muscle’s ability to use oxygen can improve the oxidative system capacity. For that reason, some researchers explored whether NaHCO3 will increase oxygen uptake and affect the oxidative system. Similar to the glycolytic system, contradictory evidence is shown in the existing literature, demonstrating that the capacity of the glycolytic system could increase [14] or stay the same with NaHCO3 ingestion [15].

The main reason why NaHCO3 has different effects on different energy metabolism systems may be due to the different exercise durations reflected by different exercise types. Some studies have shown that an intake of NaHCO3 will improve high-intensity intermittent exercise [16, 17] or repeat sprint ability [18, 19]. According to the exercise duration reflected by the specific sport characteristics, some scholars have concluded that NaHCO3 has an effect on exercises of less than 4 min, but no effect on exercise of a longer duration [20]. Other scholars have found a more specific time effect, that for less than 1 min or more than 7 min it is ineffective and its supplementary benefits for anaerobic exercise within 2 min are very limited [1]. Another point is the gender difference, that men seem to benefit more from the supplementation of NaHCO3 [19, 21], the reason for which might be found in physiological differences. Women have smaller type II fibers than men, and type II fibers rely predominantly on the glycolytic energy system [22]. This may explain why the previous research has contradictory results.

Unlike previous studies, due to different results and study discussions, this review no longer focuses on specific sports, exercise tasks or duration, but instead goes back to its source to explore the mechanism and principles of application of NaHCO3. Despite all apparent changes, the energy supply is essentially the same in all sports.

Knowledge of nutrition can influence dietary choices and impact athletic performance, and is important for coaches because they are often the most significant source of such knowledge for their athletes [23]. In addition, one article concluded that the level of athletes’ knowledge about the proper and intended use of sports supplements reveals the necessity of enforcing ongoing education about sports supplementation [24]. Clarifying the role of NaHCO3 can provide a reference for a lot of athletes and coaches.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

The present article is a meta-analysis focusing on the contribution of sodium bicarbonate to energy metabolism during different types of exercise (i.e., aerobic-based and anaerobic-based). This study followed the Preferred Reporting Elements for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [25] and the eligibility criteria of articles was determined with the application of the Participants, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome and Study design (PICOS) question model [26], elements were used in title, abstract and/or full text of articles to identity studies that met the eligibility criteria (Table 4).

Table 4.

PICOS (Participants, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study design)

| PICOS components | Detail |

|---|---|

| Participants | Healthy exercise adults |

| Intervention | Supplementation with NaHCO3 |

| Comparison | Same conditions with placebo or control group |

| Outcomes | Changes in some parameters that can express changes in energy metabolism (i.e., HCO3−, pH, BE, BLa, VO2, CO2, PO2 and PCO2) |

| Study design | Crossover or counterbalanced double- or single-blind, randomized controlled trials |

A systematic search was conducted using PubMed, Web of Science, SCOPUS, Medline and SPORTDiscus databases to identify eligible studies published from 2010 to June 2020. Search terms related with main concepts were used: “sodium bicarbonate” AND (“metabolism” OR “energy expenditure”) AND (“exercise” OR “physical activity” OR “sport”) AND “aerobic” AND “anaerobic”. Through this search, a total of 351 articles were obtained and 17 articles were finally included in this meta-analysis.

Selection of articles: inclusion and exclusion criteria

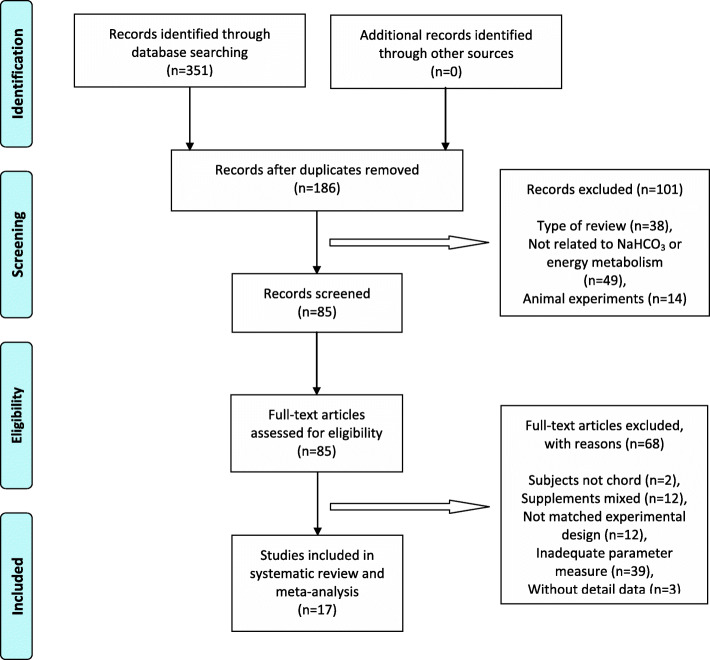

After obtaining the 351 articles according to the inclusion criteria of PICOS in the search, the following exclusion criteria were taken into consideration to determine the final studies: 1) Review and meta-analysis; 2) No sodium bicarbonate supplement ingestion or the outcomes measure not related to energy metabolism; 3) Supplement mixed with other supplements (i.e. caffeine or beta-alanine); 4) Animal experiments; 5) Injury participants or without training experience; 6) Study design not matched: not under the same experimental conditions (i.e., Hypoxia or ingested after high intensity exercise), without exercise after ingesting, no placebo as a comparison group; 7) Inadequate parameter measurement; 8) Data not described in detail (e.g., no mean or standard deviation (SD), no response after emailing author). The data collection process is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 PRIMA flow chart of selection process for articles included in this meta-analysis

The methodological quality of the articles, was evaluated using McMaster’s Critical Review Form [27]. The McMaster Form contains 15 items that are scored depending on the degree to which the specific criteria were met (yes = 1, no = 0). A summary score was calculated for each article by summing the total score obtained across relevant items and dividing it by the total possible score. The evaluation score of the quality of the articles is shown in Table 5. The main deficiencies found in methodological quality are associated with item 14 of the questionnaire, which is “were drop-outs reported?”, as there is no description about whether participants dropped out or not.

Table 5.

Methodological quality of the studies included in this meta-analysis [27]

| Items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | T(s) | % | MQ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| References | [33] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 93.3 | VG |

| [29] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 100 | E | |

| [39] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100 | E | |

| [28] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 93.3 | VG | |

| [40] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 100 | E | |

| [41] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 93.3 | VG | |

| [42] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 93.3 | VG | |

| [43] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 86.7 | VG | |

| [32] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 93.3 | VG | |

| [31] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 93.3 | VG | |

| [44] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 93.3 | VG | |

| [45] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 93.3 | VG | |

| [46] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 100 | E | |

| [30] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 100 | E | |

| [47] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 100 | E | |

| [48] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 93.3 | VG | |

| [49] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14 | 93.3 | VG | |

| T(i) | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 6 | 17 | M = 95.28 | |||

T(s): Total items fulfilled by study. (1) Criterion met; (0) Criterion not met. T(i): Total items fulfilled by items. Methodological Quality (MQ): poor (P) ≤ 8 points; acceptable (A) 9–10 points; good (G) 11–12 points; very good (VG) 13–14 points; excellent (E) =15 points. M refers to mean

Data extraction and analysis

Physiological results data were extracted in the form of mean, SD, and sample size for placebo and NaHCO3 cohorts. Data were collected directly from tables or within text of the selected studies when possible. Data of 6 studies were partially abstracted by online graph digitizing software (WebPloDigitizer1) when values were not reported in the text. This included values abstracted directly with mean and SD [28–30] or calculated after obtaining mean and standard error (SE) [31, 32] or a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) [33]. A study was excluded from the meta-analysis when the missing data could not be provided, or the author did not respond [34–36]. Dependent variables include those parameters relevant to energy metabolism after exercises following the supplement intervention. When pertinent data were not available or referenced in the article, the study was excluded from the meta-analysis.

The meta-analysis was conducted using the Review Manager 5.3 (v5.3, Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020) in order to aggregate, via a random-effects model [37], the standardized mean difference (SMD) between the effects of NaHCO3 and placebo cohorts. The mean ± SD and sample size were used to calculate SMD. A sub-group analysis was also performed to evaluate the influence on exercise with different metabolic characteristics. The use of the SMD summary statistic allowed all effect sizes to be transformed into a uniform scale, which was interpreted, according to Cohen’s conventional criteria [38], with SMD of < 0.20 being classified as negligible, 0.20–0.49 classified as small; 0.50–0.79 classified as moderate; and > 0.80 classified as large. Heterogeneity was determined using I2 value, with values of 25, 50 and 75 indicating low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively. The results are reported as weighted means and 95% CI. The statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

A total of 351 articles were initially identified through databases. Of the 186 that remained after the removal of 165 duplicates, 101 articles were not considered relevant and were excluded. Based on the inclusion criteria, 17 articles, published between 2010 and 2019, met the full set of criteria and were included for review. All descriptions and characteristics of the review studies are presented in Tables 6 and 7. Moreover, the quality assessment of selected articles was classified as Very Good (Table 5).

Table 6.

General characteristics of the studies included (Exercise characteristics as anaerobic-based)

| References | Study Design | Population characteristics | Intervention | Supplement situation | Experimental design | Physiological Results | Performance results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [33] | Randomized double-blind crossover |

12 M: elite BMX cyclists, age: 19.2 ± 3.4 y, height: 174.2 ± 5.3 cm and BM: 72.4 ± 8.4 kg |

0.3 g•kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 or 0.045 g•kg−1 BM of NaCI (PLA) | Ingested 90 min before the trial in gelatin capsules once | 3 races of BMX (track length of 400 m) with 15 min interval | ↑HCO3−, ↑pH and ↑BE vs. PLA, (12.95 ± 1.3, 7.2 ± 0.05 and − 12.66 ± 3.13 vs. 11.45 ± 1.3, 7.14 ± 0.05 and − 16.27 ± 3.18), =BLa, =HR, =RPE, =VO2, =VCO2 and = VE vs. PLA | =Time, = Velocity peak (VP) and = Time to VP vs. PLA |

| [29] | Double-blind counterbalanced crossover | 18 M: rugby, judo (n = 2) and jiu-jitsu (n = 5), age: 26 ± 5 y; BM: 88.8 ± 6.8 kg; height: 1.78 ± 0.07 m; |

500 mg/kg BM of CL or NaHCO3 or CACO3 (PLA) Divided into four individual doses of 125 mg/kg BM |

Last one within 4 h before trial, ingested in gelatin capsules for 5 consecutive days | 4 bouts of the upper body WAnT with 3 min interval | =HCO3−, =pH, =BE, =BLa vs. other conditions |

↑ TWM (2.9%) and ↑ 3rd + 4th of Wingate (5.9%) vs. CL and PLA =1st + 2nd of Wingate |

| [39] | Randomized crossover | 10 M: age: 22 ± 4 y, height: 1.77 ± 0.06 m, BM: 76 ± 9 kg. |

0.5 g•kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 or 0.2 g•kg− 1 BM of NaCI (PLA) Divided into 3 doses |

Each dose at 4 h interval on experimental day, ingested as NR once | 2 WAnT with 5 min interval | ↑HCO3−,↑pH and ↑BE vs. PLA (12.7 ± 1.3, 7.22 ± 0.04 and − 13.7 ± 1.8 vs. 9.5 ± 1.7, 7.15 ± 0.05 and − 17.8 ± 2.1), =BLa vs PLA |

↑ Work completed (5 ± 4%) vs. PLA, = Rate of fatigue vs. PLA =PP (↓PLA, −8 ± 8%) |

| [28] | Randomized double-blind crossover | 13 M: elite swimmers, age: 20.5 ± 1.4 y, BM: 80.1 ± 8.1 kg, height: 188 ± 8 cm | 0.3 g•kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 or CACO3 (PLA) | Ingested 60 min before the trial in gelatin capsules once | Two 100 m freestyle sprints with 12 min interval | ↑HCO3−, ↑pH and ↑BE vs. PLA (10.61 ± 3.43, 7.15 ± 0.05 and − 18.68 ± 2.91 vs. 7.77 ± 2.41, 7.05 ± 0.06 and − 22.78 ± 2.21), =BLa vs. PLA | = 1st 100 m swim vs. PLA, ↓ Time of 2nd 100 m swim vs. PLA (1.5 s) |

| [40] a | Randomized, double-blind, counterbalanced |

12 M: resistance-trained participants (age: 20.3 ± 2 y, BM:88.3 ± 13.2 kg, height:1.80 ± 0.07 m) |

0.3 g•kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 or CACO3 (PLA) Divided into 4 equal doses |

Each dose consumed at 10 min intervals, 1st dose at 80 min before the trial, ingested in gelatin capsules once |

4 sets of SQ, LP and KE with 120 s interval, 10-12RM per set with 90s interval |

↑HCO3−, ↑pH, ↑BE and ↑BLa vs. PLA (17.86 ± 3.63, 7.35 ± 0.04, − 7.67 ± 4.16 and 17.16 ± 2.09 vs. 14.19 ± 2.62, 7.09 ± 0.03, − 11.5 ± 3.2 and 12.49 ± 2.45) | ↑ Total volume (SQ + LP + KE + PT) vs. PLA (163.7 ± 15.1 vs. 156.7 ± 14.5) |

| [41] | Double-blind, counterbalanced |

21 M, age: 25 ± 5 y, BM: 80.7 ± 10.6 kg, height: 1.79 ± 0.06 m |

0.3 g•kg− 1 of BM NaHCO3 or maltodextrin (PLA) | Ingested 0.2 g•kg− 1 BM alongside the breakfast, 0.1 g•kg− 1 BM 2 h before the trial in gelatin capsules once | A habituation trial of the cycle-capacity test to exhaustion at 110% of Wmax | ↑HCO3−, ↑pH, ↑BE and ↑BLa vs. PLA (15.26 ± 2.78, 7.28 ± 0.05, − 9.6 ± 3.38 and 14.5 ± 2.9 vs. 12.82 ± 2.1, 7.23 ± 0.06, − 12.69 ± 2.8 and 12.4 ± 2) | =TWD, except participants who have GI ↑TWD vs. PLA (48.4 ± 9.3 vs. 46.9 ± 9.2) |

| [42]a | Randomized double-blind counterbalanced crossover |

20 rowers: age: 23 ± 4 y, height: 1.85 ± 0.08 m, BM: 82.5 ± 8.9 kg, |

0.3 g•kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 or maltodextrin (PLA) | Ingested 0.2 g•kg− 1 BM 4 h before and 0.1 g•kg− 1 BM 2 h before the trial as NR once | 2000 m rowing-ergometer TTs | ↑HCO3−, ↑pH, ↑BE and ↑BLa vs. PLA (10.56 ± 1.75, 7.18 ± 0.06, − 15.56 ± 2.69 and 16,5 ± 0.9 vs. 9.1 ± 1.71, 7.12 ± 0.07, − 18.13 ± 2.77 and 14.1 ± 0.9) | = Time of 1st and 2nd 500 m, ↓ Time of 3rd and 4th 500 m (0.5 ± 1.2 s and 1.1 ± 1.7 s) |

| [43] | Randomized, single-blind, counterbalanced |

14 swimmers (6 M, hight:181.2 ± 7.2 cm; BM: 80.3 ± 11.9 kg, 8F, height: 168.8 ± 5.6 cm; BM: 75.3 ± 10.1 kg) |

0.3 g•kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 or 0.045 g•kg− 1 BM of NaCI (PLA) | Ingested 2.5 h before the trial as NR once | Completed 8x25m front crawl maximal effort sprints with 5 s interval | ↑HCO3−, ↑pH, ↑BE and ↑BLa vs. PLA (16 ± 0.05, 7.26 ± 0.01, − 11.1 ± 0.08 and 17.69 ± 1.06 vs. 13.8 ± 0.6, 7.2 ± 0.02, − 14.6 ± 1.1 and 14.62 ± 1.25), ↓K+ vs PLA (3.8 ± 0.1 vs. 4.4 ± 0.1), =NA+ | ↓Total swim time (2%) vs. PLA |

| [32] | Randomized, double-blind, counterbalance crossover | 10 elite BMX riders, age: 20.7 ± 1.4 y, height: 178.3 ± 2.1 cm and BM: 77.9 ± 2.1 kg, | 0.3 g•kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 or placebo (PLA) | Ingested 90 min before the trial in gelatin capsules once | 3x30s Wingate tests with 15 min interval | ↑HCO3−, ↑pH and ↑BE vs. PLA (10.17 ± 1.77, 7.22 ± 0.09 and 16.57 ± 3.51 vs. 6.88 ± 2.78, 7.09 ± 0.03 and − 22.49 ± 1.39), =BLa vs. PLA | =PP, = Time to PP, =Mean power, =Fatigue index vs. PLA |

| [31] | Randomized double-blind counterbalanced |

11 trained cyclists (10 M and 1F), age: 24.5 ± 2.8 y, height: 1.78 ± 2.7 m and BM: 73.2 ± 3.8 kg |

0.3 g•kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 or 0.2 g•kg− 1 BM of CaCO3 (PLA) | Ingested 90 min before the trial in gelatin capsules once | 70s supramaximal exercise | ↑HCO3−, ↑pH and ↑BE vs. PLA (19.53 ± 3.98, 7.3 ± 0.03 and − 6.15 ± 3.91 vs. 15.12 ± 3.15, 7.21 ± 0.07 and − 12.67 ± 3.81), =BLa, =VO2, =VCO2, =VE, =PO2, ↑PCO2 vs. PLA (42 ± 2.99 vs. 38.9 ± 3.65) | ↑P50 and ↑Ptot vs. PLA (469.6 ± 28.6 and 564.5 ± 29.5 vs. 448.2 ± 7.7 and 549.5 ± 29.1), =P20 and = Fatigue index vs. PLA |

| [44] | Randomized double-blind crossover | 11 M trained cyclists, age: 32 ± 7.2 y; BM: 77.0 ± 9.2 kg | 0.3 g•kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 or 0.21 g•kg− 1 BM of NaCI (PLA) | Ingested 70-40 min before trial (depending on individual time to peak pH) as NR once | 3 min all-out critical power test | =HCO3−, =H+, =BLa, =PO2 and = PCO2 vs. PLA |

↑TWD (5.5%) and ↑W′ (14%) vs. PLA, =CP vs. PLA |

“a” means the energy metabolism mixed aerobic and anaerobic in this experimental trial, the ratio of aerobic and anaerobic almost half and half, and the physiological results relevant with anaerobic-based, so classified into anaerobic-based exercise

Notes for Tables 5 and 6: All variables of physiological results are mainly reflected in the change of the end point value (i.e., The influence after the last exercise if it has two or more bouts)

Abbreviations for Tables 5 and 6:

Supplements: NaHCO3: sodium bicarbonate, NaCI: sodium chloride, CI: calcium lactate, CaCO3: calcium carbonate, NaAc: trihydrate, NH4CI: ammonium chloride, PLA: placebo

Physiological abbreviations: M: male, F: female, BM: body mass, BLa: blood lactate, BE: base excess, ABE: actual base excess, HR: heart rate, RPE: rate of perceived exertion, VO2: oxygen uptake, VCO2: carbon dioxide production, VE: pulmonary ventilation, RER: respiratory exchange rate, FFA: free fatty acid, CHO: carbohydrate, PO2: oxygen partial pressure, PCO2: carbon dioxide partial pressure

Performance abbreviations: TWM: total mechanical work, PP: peak power, PO: power output, CP: curtail power, SQ: back squats, LP: inclined leg presses, KE: knee extensions, PT: performance test, WAnT: Wingate Anaerobic Test, TWD: total work done, TTE: time to exhaustion, FHST: Field hockey skill test, LIST: Loughborough intermittent shuttle test, P20: power output during 1st 20s, P50: power output during last 50s, Ptot: total power output

Others: NR: not recorded, BMX: bicycle motocross, w’: curvature constant, IAT: individual anaerobic threshold, ↑: Significantly higher, ↓: Significantly lower, =: no significant difference

Table 7.

General characteristics of the studies included (Exercise characteristics as aerobic-based)

| References | Study Design | Population characteristics | Intervention | Supplement situation | Experimental design | Physiological Results | Performance results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [45] | Randomized single-blind crossover | 6 M: age 24 ± 4 y, height: 1.81 ± 0.10 m, and BM: 73.92 ± 11.46 kg) |

4 mmol•kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 or NaAc Divided into two equal doses with 45 min interval |

Last dose ingested 90 min before trial as NR once | Cycling for 120 min at 119 ± 16 W (~ 50% VO2peak) |

↑blood glucose and ↑Fat oxidation vs. NaAc (3.59 ± 0.45 and 0.11 ± 0.03 vs. 3,21 ± 0.43 and 0.07 ± 0.02) =VO2, =VCO2, =RER, =BLa vs. NaAc |

NR |

| [46] | Randomized double-blind crossover | 8 M: well-trained cyclists and triathletes, age: 31.4 ± 8.8 y, height: 184.6 ± 6.5 cm, BM: 74.1 ± 7.4 kg, | 0.3 g•kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 or 0.045 g•kg− 1 BM of NaCI (PLA) | Ingested 90 min before the trial as tablets for 5 consecutive days | Maintain constant-load cycling at ‘CP’ as long as possible | ↑HCO3−, ↑pH and ↑ABE vs. PLA (32.6 ± 2.7, 7.48 ± 0.02 and 8.3 ± 2.3 vs. 26 ± 1.1, 7.43 ± 0.02 and 2.0 ± 09), =Na+, =VO2, =VCO2, =RER and = HR vs. PLA |

=CP vs. PLA ↑TTE (23.5%) |

| [30] | Double-blind counterbalanced |

11 trained cyclists, age: 35.7 ± 7.1 y, BM: 74.7 ± 10.0 kg, height: 1.75 ± 0.10 m |

0.15 g•kg− 1 BM of NH4CI or 0.03 g•kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 or 0.15 g•kg− 1 BM of CaCO3 (PLA) | Ingested 100 min before the trial in gelatin capsules once | 4-km cycling | ↑pH vs. PLA (7.3 ± 0.1 vs. 7.2 ± 0.07), =HCO3−, =BE, =BLa, =VO2, =VCO2, =PO2, =PCO2 and = RPE vs. PLA | =PO, =Anaerobic PO and = Aerobic PO vs. PLA |

| [47] | Randomized double-blind crossover | 21(16 M, 5F) well-trained cyclists: age: 24 ± 8 y, BMI: 21.3 ± 1.7 kg/m2 | 0.3 g·kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 or 4 g NaCI (PLA) | Ingested 2 h–1 h before the trial as NR once | 30 min cycling at 95% IAT followed by exercising at 110% IAT until exhaustion |

↑HCO3−, ↑pH and ↑BE vs. PLA (27.6 ± 1.7, 7.45 ± 0.03 and 3.1 ± 1.6 vs. 21.4 ± 2, 7.38 ± 0.03 and − 2.6 ± 1.7), =BLa. =HR, =PCO2, ↓PO2 vs. PLA (83.4 ± 6.5 vs. 88 ± 6.2) |

↑TTE vs. PLA (49.5 ± 11.5 min vs. 45.0 ± 9.5 min) |

| [48] | Randomized single-blind crossover | 8F elite hockey players, age: 23 ± 5 y, BM: 62.6 ± 8.4 kg, Height: 1.66 ± 0.05 m | 0.3 g•kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 or 0.02 g•kg− 1 BM of maltodextrin (PLA) | Ingested 2/3 of NaHCO3 180 min before and 1/3 90 min before the trials in gelatin capsules once | FSHT+ 2 LIST+FSHT+ 10 min recovery+ 2 LIST+FHST, about 75 min total | ↑HCO3−, ↑pH and ↑BE vs. PLA (21.7 ± 2.9, 7.41 ± 0.05 and − 2.3 ± 3.1 vs. 16.8 ± 1.6, 7.34 ± 0.06 and − 7.9 ± 1.8), =Bla, =glucose, =HR vs. PLA | = Performance time and = Sprint time vs. PLA |

| [49] | Randomized double-blind crossover |

9 M, college tennis players age 21.8 ± 2.4 y; height 1.73 ± 0.07 m |

0.3 g•kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 or 0.209 g•kg− 1 BM of NaCI (PLA) | Ingested before 90 min of trial as NR for once | Tennis simulated match, about 50 min | ↑HCO3− and ↑BE vs. PLA (37.98 ± 3.15 and 11.36 ± 3.7 vs. 26.37 ± 3.5 and 0.12 ± 2.15), =pH, =BLa, =hematocrit, =HR and = RPE vs. PLA | = Sport skill performance vs. PLA |

The study design, testing parameters and participants’ characteristics for the meta-analyzed studies are displayed in Tables 6 and 7. All studies are divided into two types of exercise, either anaerobic-based or aerobic-based. Exercise characteristics depend on the experimental design after NaHCO3 intervention in these studies, which is whether the exercise is dominated by anaerobic or aerobic ability. After review, 11 articles [28, 29, 31–33, 39–44] were found to belong to anaerobic-based exercise for analysis of AnMS, which are the ATP-CP and glycolytic systems), and 6 articles [30, 45–49] were found to belong to aerobic-based exercise for analysis of the oxidative system.

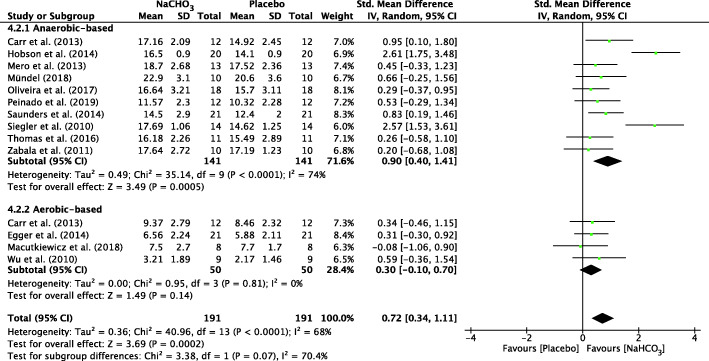

The total number of participants across all studies was 215. Studies either used mixed-sex samples (3 studies) or included only men (10 studies) or only women (1 study) and another 3 studies did not describe the gender of sample subjects. Out of the 17 included studies, 14 used a NaHCO3 dose of 0.3 g•kg− 1, two studies used the dose of 0.5 g•kg− 1, and one study used the dose of 4 mmol•kg− 1 (about 0.336 g•kg− 1). The timing of ingestion ranged from 60 min up to 4 h pre-exercise. In some studies, the dose of NaHCO3 was provided at one timepoint, with other studies splitting up the total dose at multiple timepoints. The duration of NaHCO3 administration was either once or on 5 consecutive days. The type of administration was via gelatin capsules or tablets, but some studies did not report this information (Tables 6 and 7).

The influence after ingesting NaHCO3 on AnMS

Metabolic by-products (e.g., lactic acid) are largely accumulated following the AnMS energy generation process. In the process of dissociating the metabolic by-product, the concentration of H+ in body fluids will increase and therefore lower the pH value. In order to reduce the effect of free H+, the alkaline substances in blood and muscle will combine with H+ to buffer or neutralize H+.

Fortunately, cells and body fluids have buffers such as HCO3−, that can reduce the impact of H+. Without the buffers, H+ would lower the body’s pH value by 1.5, resulting in cell death. When the intracellular pH value is lower than 6.9, it inhibits the activity of important glycolytic enzymes and reduces the rate of glycolytic and ATP production. When the pH value reaches 6.4, H+ will stop any further decomposition of glycogen, causing ATP to rapidly decline until the end of the failure. However, due to the body’s buffering capacity, even during the most strenuous exercise, the concentration of H+ can be maintained at a very low level. Even when exhausted, the muscle pH value drops slightly from the steady state of pH 7.1, but it will not drop to a pH below 6.6–6.4 [1].

To sum up, ingesting NaHCO3 will neutralize H+, thus affecting the content of buffer substances (HCO3−) in the body and pH, thereby affecting the body’s acid-base balance. Since ingestion of NaHCO3 leads to a higher efflux of lactate from the working skeletal muscle to the plasma, BLa can reflect metabolic ability to a certain extent. Therefore, the four variables (i.e., HCO3−, pH, BE and BLa), at the last time point (i.e., the influence after the last exercise if it has two or more bouts, as with the variable used to analyze the oxidative system) were chosen to assess the influence of NaHCO3 on AnMS.

Overall meta-analysis of AnMS

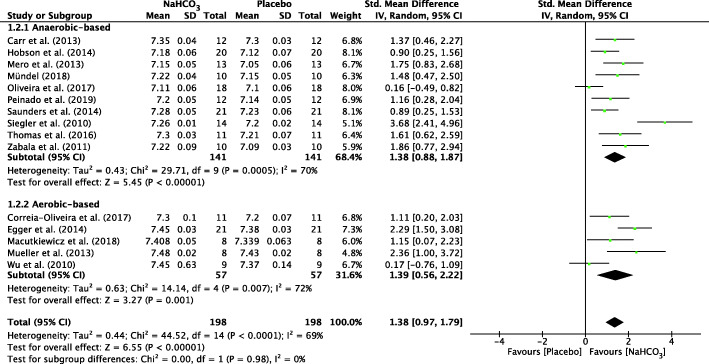

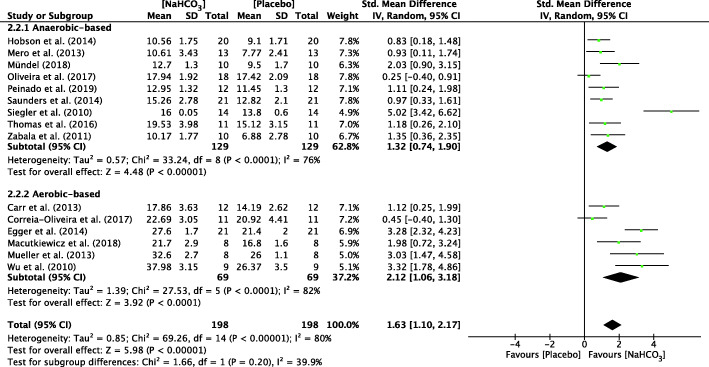

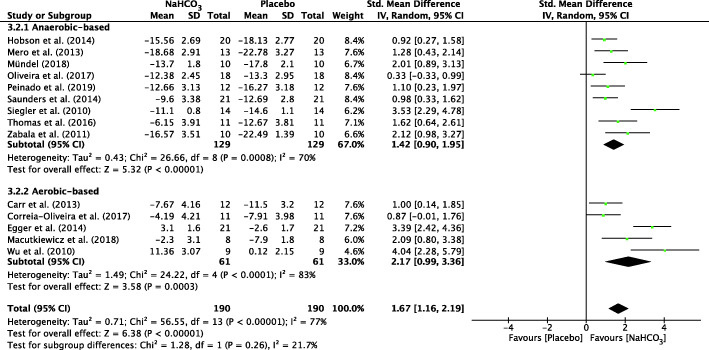

The forest plots depicting the individual SMDs and associated 95% CI and random-effect models for pH, HCO3−, BE and BLa are presented in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5 respectively.

Fig. 2 Forest plot of standardized mean difference (SMD) of NaHCO3 vs. placebo on pH after exercise. Squares represent the SMD for each study. The diamonds represent the pooled SMD for all studies. CI: Confidence interval, df: degrees of freedom

Fig. 3 Forest plot of standardized mean difference (SMD) of NaHCO3 vs. placebo on HCO3- after exercise. Squares represent the SMD for each study. The diamonds represent the pooled SMD for all studies. CI: Confidence interval, df: degrees of freedom.

Fig. 4 Forest plot of standardized mean difference (SMD) of NaHCO3 vs. placebo on BE after exercise. Squares represent the SMD for each study. The diamonds represent the pooled SMD for all studies. CI: Confidence interval, df: degrees of freedom

Fig. 5 Forest plot of standardized mean difference (SMD) of NaHCO3vs. placebo on BLa after exercise. Squares represent the SMD for each study. The diamonds represent the pooled SMD for all studies. CI: Confidence interval, df: degrees of freedom

The SMD for blood pH value was 1.38 (95% CI: 0.97 to 1.79), indicating a significant effect during exercise between NaHCO3 and placebo conditions (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). In addition, there was a significant effect during exercise after ingesting NaHCO3 on HCO3− (SMD = 1.63, 95% CI: 1.10 to 2.17, P < 0.001; Fig. 3), BE (SMD = 1.67, 95% CI: 1.16 to 2.19, P < 0.001; Fig. 4) and BLa (SMD = 0.72, 95% CI: 0.34 to 1.11, P < 0.001; Fig. 5) in the blood. Moderate heterogeneity was detected among studies assessing pH (I2 = 69%) and BLa (I2 = 68%), whereas HCO3- and BE presented a high heterogeneity (I2 = 80% and I2 = 77% respectively).

Sub-group analysis of AnMS

A sub-group analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of NaHCO3 ingestion on exercise with different metabolic characteristics. There was a significant difference between two cohorts for pH value in anaerobic-based (SMD = 1.38, 95% CI: 0.88 to 1.87, P < 0.001, I2 = 70%) and aerobic-based (SMD = 1.39, 95% CI: 0.56 to 2.22, P = 0.001, I2 = 72%) exercise (Fig. 2). Similar to HCO3− and BE, there was a significant difference between two cohorts for HCO3− and BE in anaerobic-based exercise (SMD = 1.29, 95% CI: 0.77 to 1.18, P < 0.001, I2 = 73% and SMD = 1.37, 95% CI: 0.94 to 1.84, P < 0.001, I2 = 67% respectively) and aerobic-based exercise (SMD = 2.35, 95% CI: 1.06 to 3.64, P < 0.001, I2 = 83% and SMD = 2.52, 95% CI: 1.07 to 3.96, P < 0.001, I2 = 84% respectively) (Figs. 3 and 4).

A significant difference between two cohorts was also found for BLa in anaerobic-based exercise (SMD = 0.90, 95% CI: 0.40 to 1.41, P < 0.001, I2 = 74%) but a non-significant difference on aerobic-based exercise (SMD = 0.30, 95% CI: − 0.1 to 0.7, P = 0.14). Heterogeneity was not detected among studies assessing BLa (I2 = 0%) in aerobic-based exercise. (Fig. 5).

Strategic analysis of NaHCO3 in AnMS

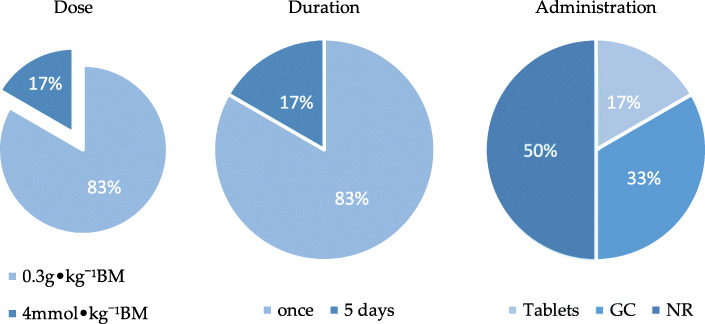

For anaerobic-based exercise (Table 6), 9 (82%) out of 11 studies used 0.3 g•kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 and the remaining 2 articles used 0.5 g•kg− 1 BM. The duration was once in 10 (91%) studies, while 1 study had duration of 5 consecutive days. The administration of NaHCO3 was in gelatin capsules in 7 (64%) studies and not recorded in 4 studies (Fig. 6). More than half of the studies showed NaHCO3 ingestion 90–60 min before the trial, other studies shown it more than 2 h before the trial.

Fig. 6 The percentage of dose, duration and administration of 11 studies based on anaerobic exercise. GC: gelatin capsules, NR: not record

The influence after ingesting NaHCO3 on the oxidative system

When performing long-term moderate-intensity exercise, the ventilation volume matches the energy metabolism rate, and it is necessary to constantly change the ratio between the body’s oxygen uptake (VO2) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2). It is widely acknowledged that a higher VO2 is associated with a stronger aerobic capacity. Most of the CO2 (about 60–70%) produced during muscle exercise is transported back to the heart in the form of HCO3− [1]. CO2 and water molecules combine to form carbonic acid, which is unstable and will soon dissolve, forming free H+ and HCO3−:

When the blood enters the area where the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) in the lungs is low, H+ will combine with HCO3− to form carbonic acid, and then decompose into CO2 and water:

After CO2 enters the lungs, it is eliminated by dissociation, which is the main way to reduce H+ concentration when CO2 is eliminated [1].

The amount and rate of gas exchange across the respiratory membrane are mainly determined by the partial pressure of each gas. The gas diffuses along the pressure gradient, from the part with the higher pressure to the lower pressure part. At standard atmospheric pressure, the partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) outside the body is greater than that inside the body after alveolar gas exchange. When the exercising muscles require more oxygen to meet metabolic needs, the venous oxygen is depleted and accelerates the alveolar gas exchange, resulting in PO2 reduction [1]. Therefore, O2 enters the blood and CO2 leaves the blood. PCO2 is mainly used to determine whether there is respiratory acidosis or alkalosis. Increased PCO2 suggests that there is insufficient lung ventilation, and CO2 retention in the body, which leads to respiratory acidosis. Lower PCO2, indicating hyperventilation (such as deeper or faster breathing), and excessive CO2 elimination in the body, leads to respiratory alkalosis [1]. Therefore, an increase in PCO2 will cause an increase in CO2 in the blood, which will result in a decrease in the pH value.

To sum up, the change of O2 and CO2 during long-term moderate-intensity exercise can reflect aerobic capacity to a certain extent. For that reason, the four variables (i.e., VO2, VCO2, PO2 and PCO2) were chosen to assess the influence of NaHCO3 on the oxidative system.

Overall meta-analysis of the oxidative system

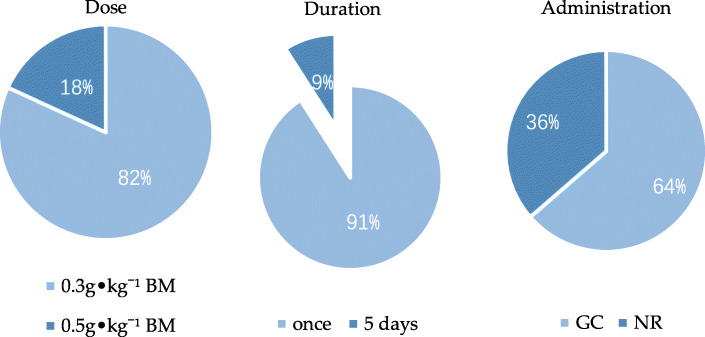

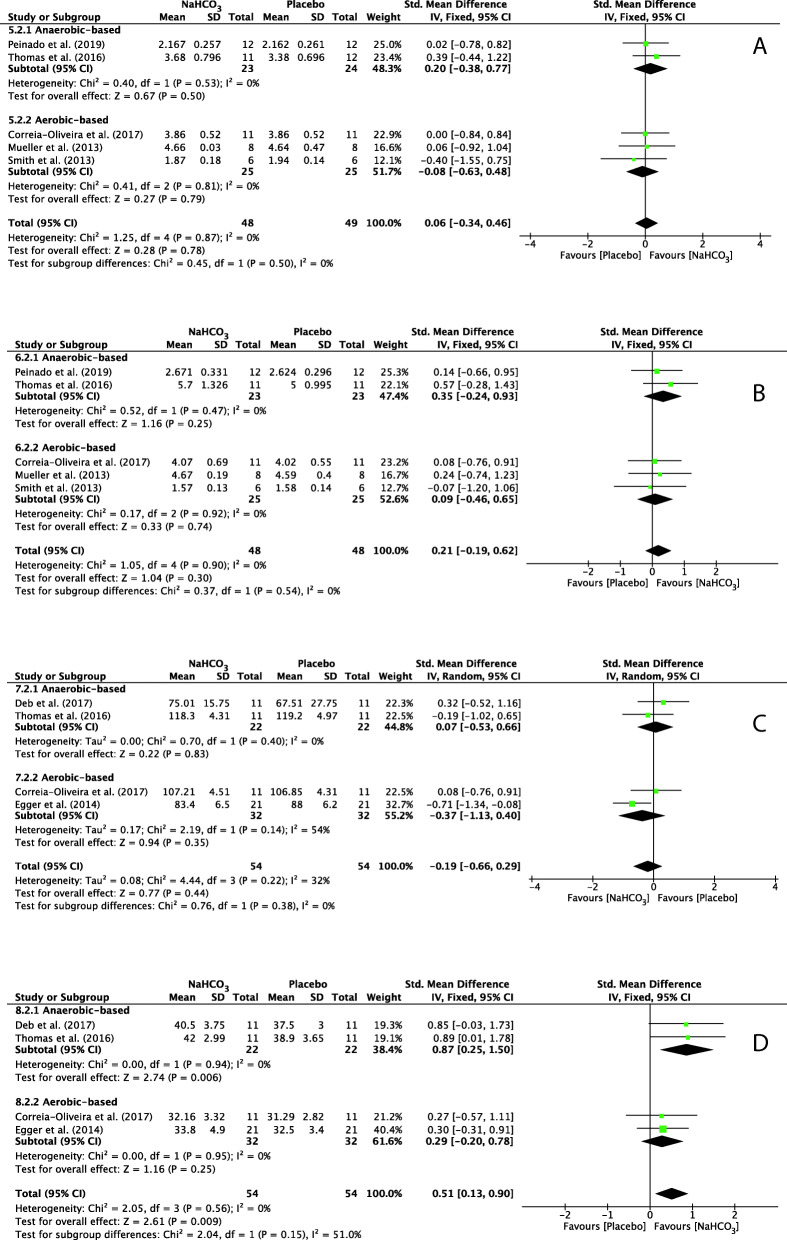

The forest plots depicting the individual SMDs and associated 95% CI and random-effect models for VO2, VCO2, PO2 and PCO2 are presented in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7 Forest plot of standardized mean difference (SMD) of NaHCO3 vs. placebo on VO2(A), VCO2(B), PO2(C) and PCO2(D) after exercise. Squares represent the SMD for each study. The diamonds represent the pooled SMD for all studies. CI: Confidence interval, df: degrees of freedom

The SMD for VO2 was 0.06 (95% CI: − 0.34 to 0.46), indicating a non-significant effect during exercise between NaHCO3 and placebo cohorts (p = 0.78) (Fig. 7a). Similarly, there was a non-significant effect during exercise after ingestion of NaHCO3 on VCO2 (SMD = 0.21, 95% CI: − 0.19 to 0.62, P = 0.30) and PO2 (SMD = − 0.19, 95% CI: − 0.66 to 0.29, P = 0.44) (Fig. 7b and c), but a significant effect on PCO2 (SMD = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.13 to 0.90, P = 0.009) (Fig. 7d). Heterogeneity was not detected among studies assessing VO2, VCO2 and PCO2 (I2 = 0%) and PO2 presented a low heterogeneity (I2 = 32%), shown in Fig. 7a, b, c and d respectively.

Sub-group analysis of the oxidative system

A sub-group analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of NaHCO3 ingestion on exercise with different metabolic characteristics. There was a non-significant difference between two cohorts for VO2 in anaerobic-based (SMD = 0.20, 95% CI: − 0.38 to 0.77, P = 0.50, I2 = 0%) and aerobic-based (SMD = − 0.08, 95% CI: − 0.63 to 0.48, P = 0.79, I2 = 0%) exercise (Fig. 7a). Similar to VCO2 and PO2, there was a non-significant difference between cohorts for VCO2 and PO2 in anaerobic-based exercise (SMD = 0.35, 95% CI: − 0.24 to 0.93, P = 0.25, I2 = 0% and SMD = 0.07, 95% CI: − 0.53 to 0.66, P = 0.83, I2 = 0% respectively) and aerobic-based exercise (SMD = 0.09, 95% CI: − 0.46 to 0.65, P = 0.74, I2 = 0% and SMD = − 0.37, 95% CI: − 1.13 to 0.40, P = 0.35, I2 = 54% respectively) (b and c in Fig. 7).

The opposite results are shown in Fig. 7d. There was a significant difference between cohorts for PCO2 in anaerobic-based (SMD = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.25 to 1.50, P = 0.006) but not aerobic-based (SMD = 0.29, 95% CI: − 0.20 to 0.78, P = 0.25) exercise. Heterogeneity was not detected among studies assessing PCO2 in anaerobic-based (I2 = 0%) and aerobic-based (I2 = 0%) exercise.

Strategic analysis of NaHCO3 on the oxidative system

For aerobic-based exercise (Table 7), 5 (83%) out of 6 studies used 0.3 g•kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 and 1 article used 4 mmol•kg− 1 (about 0.336 g•kg− 1). The duration was once in 5 (83%) out of 6 studies, while 1 study had a duration of 5 consecutive days. The administration of NaHCO3 was in tablets in 1 study, gelatin capsules in 2 studies and not recorded in 3 studies (Fig. 8). Half of the studies showed NaHCO3 ingestion 90 min before the trial, other studies showed it 3–1.5 h before the trial.

Fig. 8 The percentage of dose, duration and administration of 6 studies based on aerobic exercise. GC: gelatin capsules, NR: not record

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to assess the contribution of NaHCO3 ingestion on energy metabolism during exercise with a meta-analytic statistical technique using Review Manager 5.3 (v5.3, Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020). The main findings of this analysis indicated that ingestion of NaHCO3 improves pH, HCO3− and BE in the blood during exercise compared to a placebo (Figs. 2, 3, 4). However, BLa can be improved in anaerobic-based but not in aerobic-based exercise through ingestion of NaHCO3 (Fig. 5). Furthermore, compared to a placebo, ingestion of NaHCO3 during exercise does not improve VO2, VCO2 and PO2, although it improves PCO2 in anaerobic-based but not aerobic-based exercise (Fig. 7). Collectively these results indicate that ingestion of NaHCO3 is better than a placebo to improve AnMS but makes no difference to the oxidative system.

The discrepancies in the studies reported in this meta-analysis need to be considered. The extracellular to intracellular pH gradient increases as HCO3− is impermeable to cellular membranes [50], resulting in a greater efflux of H+ and lactate from active muscles [51]. This occurs via either simple diffusion or by the lactate or H+ co-transporters [5]. It has been suggested that lactate efflux from muscles is higher as a result of extracellular alkalosis. However, Fig. 5 shows that there was no significant difference for BLa in an aerobic-based situation. That may explain the lack of effect with ingestion of NaHCO3 on performance that is based on the oxidative system, despite the significant effects on AnMS.

Therefore, a sensitivity analysis was performed to verify the results. According to the evaluation results in Table 5, the study with the lowest score [43] and another 5 articles [33, 41, 42, 44, 45] that were not given full marks were excluded. These sensitivity analysis results were similar to those of the original meta-analysis.

Discussion on AnMS

Results in the present analysis indicate that NaHCO3 ingestion is effective in improving AnMS, which may be able to improve sport performance based on anaerobic capacity. The performance results of included studies showed that performance improved or was maintained the same when ingesting NaHCO3, while a placebo showed a decline in sport performance. (Table 6). This result is different from that of other meta-analyses [52, 53], but similar to several individual studies which did not meet the present eligibility criteria [54, 55]. Two included studies [32, 33] reported no improvement in sport performance, and we found that the experimental exercise in these two articles were more likely based on the ATP-CP system to obtain energy (Table 6). This is similar to previous studies [12, 56], where the ATP-CP system was not affected by NaHCO3 ingestion.

The key point of the contraindications in different results may be the gastrointestinal (GI) problems caused by ingestion of NaHCO3. Because the bicarbonate buffer system is not solely responsible for blood pH and is also vital in other systems, such as the stomach and duodenum by neutralizing gastric acid, abdominal pain and diarrhea are often experienced by individuals who take NaHCO3 [36, 57]. An article included in the present study also illustrated this problem [41]. While the results among all subjects indicated that the intake of NaHCO3 has no effect on sports performance, after excluding subjects who had GI problems with ingestion of NaHCO3, a significant difference in sports performance was observed. However, in this meta-analysis, the author extracted the data of all subjects from this article and verified that it did not affect the results of the meta-analysis. In response to the GI problems, some countermeasures have been taken that have been scientifically proven to alleviate or prevent GI problems. For example, ingestion of a large amount of water [58], with food [9], with carbohydrate [59] or administration as enteric-formulated capsules [60]. More measures to prevent GI problems may help demonstrate the improvement in sport performance with the intake of NaHCO3 as subjects are not troubled by GI problems.

Discussion on the oxidative system

Although the overall PCO2 in Fig. 7 shows a significant difference, aerobic-based exercise alone presented no significant difference. Therefore, ingestion of NaHCO3 does not benefit exercise based on the oxidative system, which means it may not be able to improve sport performance that is based on aerobic capacity. This is similar to the performance results shown in Table 7, with the exception of one study [45] that did not record performance results and two other studies that had results possibly due to chronic ingestion [46], or the decrease in PO2 [47] due to ingestion of NaHCO3. As mentioned before, PO2 reduction accelerates alveolar gas exchange. The results based on this meta-analysis, that the sport performance based on aerobic capacity is not affected by NaHCO3 ingestion, is different from some previous studies [14, 61], but similar to other studies [15, 62].

There is a reason why NaHCO3 intake will cause different results for aerobic-based exercise. Whether ATP is produced under aerobic or anaerobic conditions, glycogen plays an important role. Glycogen can provide energy to maintain moderate-intensity exercise for 3 to 5 min under aerobic conditions. The reason some studies [14, 61] have different results from the present study may be because they are based on the aerobic energy supply form of muscle glycogen. However, the studies included in this present meta-analysis are based on the aerobic energy supply form of fat (according to the exercise time, energy from fat can be maintained for 1–2 h or more) (Table 1). Different forms of the oxidative system supply may be one of the reasons for the different performance results after ingestion of NaHCO3.

Limitations

A number of limitations may be present in this meta-analysis and should be considered. Firstly, the choice of variables that reflect the ATP-CP, glycolytic and oxidative systems may not be a good representative of performance. As we know, the substrates of ATP recovery for the ATP-CP, glycolytic and oxidative system are ATP/PCr, glucose and fat (i.e. free fatty acid [FFA], which are the main energy sources for the oxidative system) [1] respectively. The ideal way is to use these variables because the changes in their content can directly reflect the changes in the capacity of each energy metabolism system. However, a total of 9 articles from the initial search analyzed using these parameters (i.e., ATP, PCr, glucose or FFA), and there was only one left after excluding articles that did not meet the eligibility criteria. This is why we chose pH, HCO3−, BE and BLa; VO2, VCO2, PO2 and PCO2 that reflect the changes in the capacity of each energy metabolism system indirectly instead, which may affect the accuracy of the research results.

Additionally, this study analyzes the integration of the ATP-CP and glycolytic system as an AnMS, but in fact the research results of this article may be biased towards the glycolytic system. ATP resynthesis into ATP-CP occurs very quickly, and intake of NaHCO3 may be too late to have an effect. Therefore, there is a lack of a specific influence of ingestion of NaHCO3 on the ATP-CP system, while other studies have reported that induced alkalosis does not affect the ATP-CP system, but does benefit the glycolytic system and does not impact the oxidative system [11, 17], similar to the results in the present meta-analysis.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis provides evidence that ingestion of NaHCO3 increases the content of pH, HCO3−, BE and lactate in the blood, that may be beneficial to exercise based on the anaerobic metabolism system, especially based on the glycolytic system. The ideal way is to ingest it in a gelatin capsule in an acute mode and use a dose of 0.3 g•kg− 1 BM of NaHCO3 90 min before the trial. Furthermore, the specific form of aerobic oxidative supply should be considered before ingesting NaHCO3 when doing aerobic exercise. Therefore, athletes and coaches should take notice that anaerobic and aerobic exercise and sports capacity based on the glycolytic system may be improved by supplementing with NaHCO3.

Acknowledgments

The authors are particularly grateful to Universidad Politécnica de Madrid and Universidad Europea.

Abbreviations

- NaHCO3

Sodium bicarbonate

- HCO3−

Bicarbonate ion

- BE

Base excess

- BLa

Blood lactate

- VO2

Oxygen uptake

- VCO2

Carbon dioxide production

- PO2

Partial pressure of oxygen

- PCO2

Partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- AnMS

Anaerobic metabolism system

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- CP

Creatine phosphate

- PCr

Phosphocreatine

- ADP

Adenosine diphosphate

- CUE

Continuous unit of energy

- SMD

Standardized mean differences

- SE

Standard error

- SD

Standard deviation

- CI

Confidence interval

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- FFA

Free fatty acid

Authors’ contributions

J.L.C.: conceptualization, conceived and designed the investigation, interpreted the data, drafted the paper, and approved the final version. H.X.: investigation, meta-analysis and interpreted the data, wrote the manuscript and submitted the paper. D.M.L: methodology, analyzed and interpreted the data. (H.P.G).: critically reviewed the paper, approved the final version submitted for publication, and funding acquisition. S.L.J.: critically reviewed the paper, interpreted the data and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has no external funding.

Availability of data and materials

The data used and/ or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jorge Lorenzo Calvo, Email: jorge.lorenzo@upm.es.

Huanteng Xu, Email: xht-hunter@bsu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Kenney WL, Wilmore JH, and Costill DL: Physiology of sport and exercise: Human kinetics; 2015(Series Editor).

- 2.MacLaren D and Morton J: Biochemistry for sport and exercise metabolism: John Wiley & Sons; 2011(Series Editor).

- 3.Sahlin K. Muscle energetics during explosive activities and potential effects of nutrition and training. Sports Med. 2014;44:167–173. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0256-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zinner C, Wahl P, Achtzehn S, et al. Effects of bicarbonate ingestion and high intensity exercise on lactate and h +−ion distribution in different blood compartments. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;111:1641–1648. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1800-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Juel C. Current aspects of lactate exchange: lactate/h+ transport in human skeletal muscle. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2001;86:12–16. doi: 10.1007/s004210100517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burke LM: Practical considerations for bicarbonate loading and sports performance. In Nutritional coaching strategy to modulate training efficiency. Volume 75. Edited by Tipton KD and VanLoon LJC; 2013:15–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Carr AJ, Hopkins WG, Gore CJ. Effects of acute alkalosis and acidosis on performance: a meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2011;41:801–814. doi: 10.2165/11591440-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cameron SL, McLay-Cooke RT, Brown RC, et al. Increased blood ph but not performance with sodium bicarbonate supplementation in elite rugby union players. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2010;20:307–321. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.20.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carr AJ, Slater GJ, Gore CJ, et al. Effect of sodium bicarbonate on [hco3 -], ph, and gastrointestinal symptoms. International Journal of Sport Nutrition & Exercise Metabolism. 2011;21:189–194. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.21.3.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Limmer M, Sonntag J, de Marées M, et al. Effects of an alkalizing or acidizing diet on high-intensity exercise performance under normoxic and hypoxic conditions in physically active adults: a randomized, crossover trial. Nutrients. 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Lopes-Silva JP, Da Silva Santos JF, Artioli GG, et al. Sodium bicarbonate ingestion increases glycolytic contribution and improves performance during simulated taekwondo combat. Eur J Sport Sci. 2018;18:431–440. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2018.1424942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephens TJ, McKenna MJ, Canny BJ, et al. Effect of sodium bicarbonate on muscle metabolism during intense endurance cycling. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:614–621. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edge J, Eynon N, McKenna MJ, et al. Altering the rest interval during high-intensity interval training does not affect muscle or performance adaptations. Exp Physiol. 2013;98:481–490. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.067603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maliqueo SAG, Ojeda ÁCH, Barrilao RG, et al. Time to fatigue on lactate threshold and supplementation with sodium bicarbonate in middle-distance college athletes. Archivos de Medicina del Deporte. 2018;35:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Northgraves MJ, Peart DJ, Jordan CA, et al. Effect of lactate supplementation and sodium bicarbonate on 40-km cycling time trial performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28:273–280. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182986a4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krustrup P, Ermidis G, Mohr M. Sodium bicarbonate intake improves high-intensity intermittent exercise performance in trained young men. J Int Soc Sport Nutr. 2015;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.da Silva RP, de Oliveira LF, Saunders B, et al. Effects of β-alanine and sodium bicarbonate supplementation on the estimated energy system contribution during high-intensity intermittent exercise. Amino Acids. 2019;51:83–96. doi: 10.1007/s00726-018-2643-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGinley C, Bishop DJ. Influence of training intensity on adaptations in acid/base transport proteins, muscle buffer capacity, and repeated-sprint ability in active men. J Appl Physiol. 2016;121:1290–1305. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00630.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller P, Robinson AL, Sparks SA, et al. The effects of novel ingestion of sodium bicarbonate on repeated sprint ability. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30:561–568. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadzic M, Eckstein ML, Schugardt M. The impact of sodium bicarbonate on performance in response to exercise duration in athletes: a systematic review. J Sports Sci Med. 2019;18:271–281. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price M, Moss P, Rance S. Effects of sodium bicarbonate ingestion on prolonged intermittent exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1303–1308. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000079067.46555.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simoneau JA, Bouchard C. Human variation in skeletal muscle fiber-type proportion and enzyme activities. Am J Phys. 1989;257:E567–E572. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1989.257.4.E567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heikkilä M, Valve R, Lehtovirta M, et al. Nutrition knowledge among young Finnish endurance athletes and their coaches. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2018;28:522–527. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2017-0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jovanov P, Đorđić V, Obradović B, et al. Prevalence, knowledge and attitudes towards using sports supplements among young athletes. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2019;16:27. doi: 10.1186/s12970-019-0294-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X, Chen Y, Liu Y, et al. Reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of acupuncture: the prisma for acupuncture checklist. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19:208. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2624-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernández-Lázaro D, Mielgo-Ayuso J, Seco Calvo J, et al. Modulation of exercise-induced muscle damage, inflammation, and oxidative markers by curcumin supplementation in a physically active population: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Law MS, D. Pollock, N. Letts, L. Bosch, J. Westmorland, M.: Guidelines for critical review form—quantitative studies 1998. Hamilton, ON, Canada: McMaster University; 2008(Series Editor).

- 28.Mero AA, Hirvonen P, Saarela J, et al. Effect of sodium bicarbonate and beta-alanine supplementation on maximal sprint swimming. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2013;10:52. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-10-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliveira LF, de Salles PV, Nemezio K, et al. Chronic lactate supplementation does not improve blood buffering capacity and repeated high-intensity exercise. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017;27:1231–1239. doi: 10.1111/sms.12792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Correia-Oliveira CR, Lopes-Silva JP, Bertuzzi R, et al. Acidosis, but not alkalosis, affects anaerobic metabolism and performance in a 4-km time trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49:1899–1910. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas C, Delfour-Peyrethon R, Bishop DJ, et al. Effects of pre-exercise alkalosis on the decrease in vo2 at the end of all-out exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2016;116:85–95. doi: 10.1007/s00421-015-3239-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zabala M, Peinado AB, Calderón FJ, et al. Bicarbonate ingestion has no ergogenic effect on consecutive all out sprint tests in bmx elite cyclists. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;111:3127–3134. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-1938-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peinado AB, Holgado D, Luque-Casado A, et al. Effect of induced alkalosis on performance during a field-simulated bmx cycling competition. J Sci Med Sport. 2019;22:335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joyce S, Minahan C, Anderson M, et al. Acute and chronic loading of sodium bicarbonate in highly trained swimmers. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112:461–469. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-1995-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Araujo Dias GF, Eira Silva VD, Painelli VDS, et al.: (in)consistencies in responses to sodium bicarbonate supplementation: A randomised, repeated measures, counterbalanced and double-blind study. PLoS One 2015, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Freis T, Hecksteden A, Such U, et al. Effect of sodium bicarbonate on prolonged running performance: a randomized, double-blind, cross-over study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mündel T: Sodium bicarbonate ingestion improves repeated high-intensity cycling performance in the heat. Temperature (Austin, Tex) 2018, 5:343–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Carr BM, Webster MJ, Boyd JC, et al. Sodium bicarbonate supplementation improves hypertrophy-type resistance exercise performance. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113:743–752. doi: 10.1007/s00421-012-2484-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saunders B, Sale C, Harris RC, et al. Sodium bicarbonate and high-intensity-cycling capacity: variability in responses. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2014;9:627–632. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2013-0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hobson RM, Harris RC, Martin D, et al. Effect of sodium bicarbonate supplementation on 2000-m rowing performance. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2014;9:139–144. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2013-0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siegler JC, Gleadall-Siddall DO. Sodium bicarbonate ingestion and repeated swim sprint performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24:3105–3111. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181f55eb1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deb SK, Gough LA, Sparks SA, et al. Determinants of curvature constant (w') of the power duration relationship under normoxia and hypoxia: the effect of pre-exercise alkalosis. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2017;117:901–912. doi: 10.1007/s00421-017-3574-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith GI, Jeukendrup AE, Ball D. The effect of sodium acetate ingestion on the metabolic response to prolonged moderate-intensity exercise in humans. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2013;23:357–368. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.23.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mueller SM, Gehrig SM, Frese S, et al. Multiday acute sodium bicarbonate intake improves endurance capacity and reduces acidosis in men. J Int Soc Sport Nutr. 2013;10:16. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Egger F, Meyer T, Such U, et al. Effects of sodium bicarbonate on high-intensity endurance performance in cyclists: a double-blind, randomized cross-over trial. PLoS One. 2014;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Macutkiewicz D, Sunderland C. Sodium bicarbonate supplementation does not improve elite women's team sport running or field hockey skill performance. Physiol Rep. 2018;6:e13818. doi: 10.14814/phy2.13818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu CL, Shih MC, Yang CC, et al. Sodium bicarbonate supplementation prevents skilled tennis performance decline after a simulated match. J Int Soc Sport Nutr. 2010;7:33. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McNaughton LR, Siegler J, Midgley A. Ergogenic effects of sodium bicarbonate. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2008;7:230–236. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e31817ef530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peart DJ, Siegler JC, Vince RV. Practical recommendations for coaches and athletes: a meta-analysis of sodium bicarbonate use for athletic performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26:1975–1983. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182576f3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lopes-Silva JP, Reale R, Franchini E. Acute and chronic effect of sodium bicarbonate ingestion on Wingate test performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sports Sci. 2019;37:762–771. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2018.1524739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lopes-Silva JP, Choo HC, Franchini E, et al. Isolated ingestion of caffeine and sodium bicarbonate on repeated sprint performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 2019;22:962–972. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gough LA, Rimmer S, Sparks SA, et al. Post-exercise supplementation of sodium bicarbonate improves acid base balance recovery and subsequent high-intensity boxing specific performance. Front Nutr. 2019;6:155. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Durkalec-Michalski K, Nowaczyk PM, Adrian J, et al. The influence of progressive-chronic and acute sodium bicarbonate supplementation on anaerobic power and specific performance in team sports: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Nutrition & Metabolism. 2020;17:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12986-020-00457-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Edge J, Bishop D, and Goodman C: Effects of chronic nahco3 ingestion during interval training on changes to muscle buffer capacity, metabolism, and short-term endurance performance. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2006, 101:918–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Kahle LE, Kelly PV, Eliot KA, et al. Acute sodium bicarbonate loading has negligible effects on resting and exercise blood pressure but causes gastrointestinal distress. Nutr Res. 2013;33:479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Siegler JC, Marshall PW, Bray J, et al. Sodium bicarbonate supplementation and ingestion timing: does it matter? J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26:1953–1958. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182392960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Franca E, Xavier AP, Dias IR, et al. Fractionated sodium bicarbonate coingestion with carbohydrate increase performance without gastrointestinal discomfort. Rbne. 2015;9:437–446. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hilton NP, Leach NK, Craig MM, et al. Enteric-coated sodium bicarbonate attenuates gastrointestinal side-effects. International Journal of Sport Nutrition & Exercise Metabolism. 2020;30:62–68. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2019-0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grgic J, Garofolini A, Pickering C, et al. Isolated effects of caffeine and sodium bicarbonate ingestion on performance in the yo-yo test: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 2020;23:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2019.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ferreira LHB, Smolarek AC, Chilibeck PD, et al.: High doses of sodium bicarbonate increase lactate levels and delay exhaustion in a cycling performance test. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif) 2019, 60:94–99. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used and/ or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.