Nephrotic syndrome is the most common cause of glomerular disease in school-age and adolescent children, affecting two to five children in 100,000 each year (1). Standard first-line therapy for initial presentation of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome is 6 weeks of daily corticosteroids, followed by 6 weeks of alternate-day therapy (2). Nearly 80% of children with nephrotic syndrome will have steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome that responds to therapy early and is associated with an excellent long-term prognosis (1–3). Despite the large proportion of children with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome, up to 80% of children will have at least one relapse, and more than half of children will develop a frequent relapsing and/or steroid-dependent course, necessitating frequent exposure to corticosteroids and their resultant side effects (3).

Although we know that corticosteroid therapy is effective in the treatment of the initial presentation and relapse of nephrotic syndrome, we do not know what the fine balance is between the dose and duration of corticosteroid therapy that is compatible with efficacy and minimal side effects (4). Major side effects of prolonged corticosteroid use include obesity, hyperglycemia, cataracts, and hypertension (1–4). Because nephrotic syndrome relapses place a patient at repeated exposure to corticosteroids and major side effects of treatment, physicians must weigh the risks of prolonged corticosteroid therapy side effects with its therapeutic benefits of preventing frequent relapse.

The limited availability of data to guide this clinical conundrum has led physicians to devise different strategies to minimize corticosteroid exposure and side effects in children with nephrotic syndrome. Examples are the use of second-line agents, such as calcineurin inhibitors, antiproliferative agents, and different biologics, to maintain remission in children with frequent relapsing and/or steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome, in addition to the use of short courses of corticosteroids to prevent full-blown relapse in children with fever and upper respiratory tract infection (1,3,5). Despite these efforts, there are still no universally acceptable guidelines to minimize clinical and subclinical side effects of corticosteroids in children with nephrotic syndrome, nor are there robust data on how use of corticosteroids themselves may affect frequency of relapse (4). Therefore, studies addressing these gaps are important areas of clinical need.

The study by Kainth et al. (6) in this issue of CJASN is a welcome development toward solving this clinical problem. In this study, the authors focused on determining the optimal duration of corticosteroid therapy in children with infrequent relapse of nephrotic syndrome, defined as fewer than two relapses in 6 months or fewer than four relapses in 12 months. They performed an open-label, noninferiority, randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of a shortened corticosteroid regimen (40 mg/m2 on alternate days, for 2 weeks) and the standard corticosteroid regimen (40 mg/m2 on alternate days, for 4 weeks) used in the treatment of all relapse (6). The primary outcome was the proportion of children developing frequent relapse/steroid dependence at 12 months of follow-up, and secondary outcomes were the differences between the two groups in time to relapse, relapse rate, cumulative corticosteroid dose, and corticosteroid-related adverse effects during the follow-up period. The investigators found no difference in the proportion of children developing a frequent relapsing and/or steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome course between the two groups. Time to relapse and the relapse rate did not differ between the two groups. Side effects were similar between the groups as well. As expected, cumulative corticosteroid exposure during the follow-up period was reduced in the short regimen compared with the standard-of-care group. However, noninferiority of the short course therapy could not be established because this is a pilot study and is most likely underpowered. Nevertheless, this study has the potential to change the standard management of children with nephrotic syndrome if the findings are confirmed in larger studies. The data showed that we could possibly reduce the duration of corticosteroid therapy in patients with infrequent relapse of nephrotic syndrome without increasing the risk of subsequent development of a frequent relapsing and/or steroid-dependent course that will necessitate further exposure to corticosteroid therapy. Although the risk difference between the two groups did not cross the noninferiority margin because of the modest cohort, the observation is still very important.

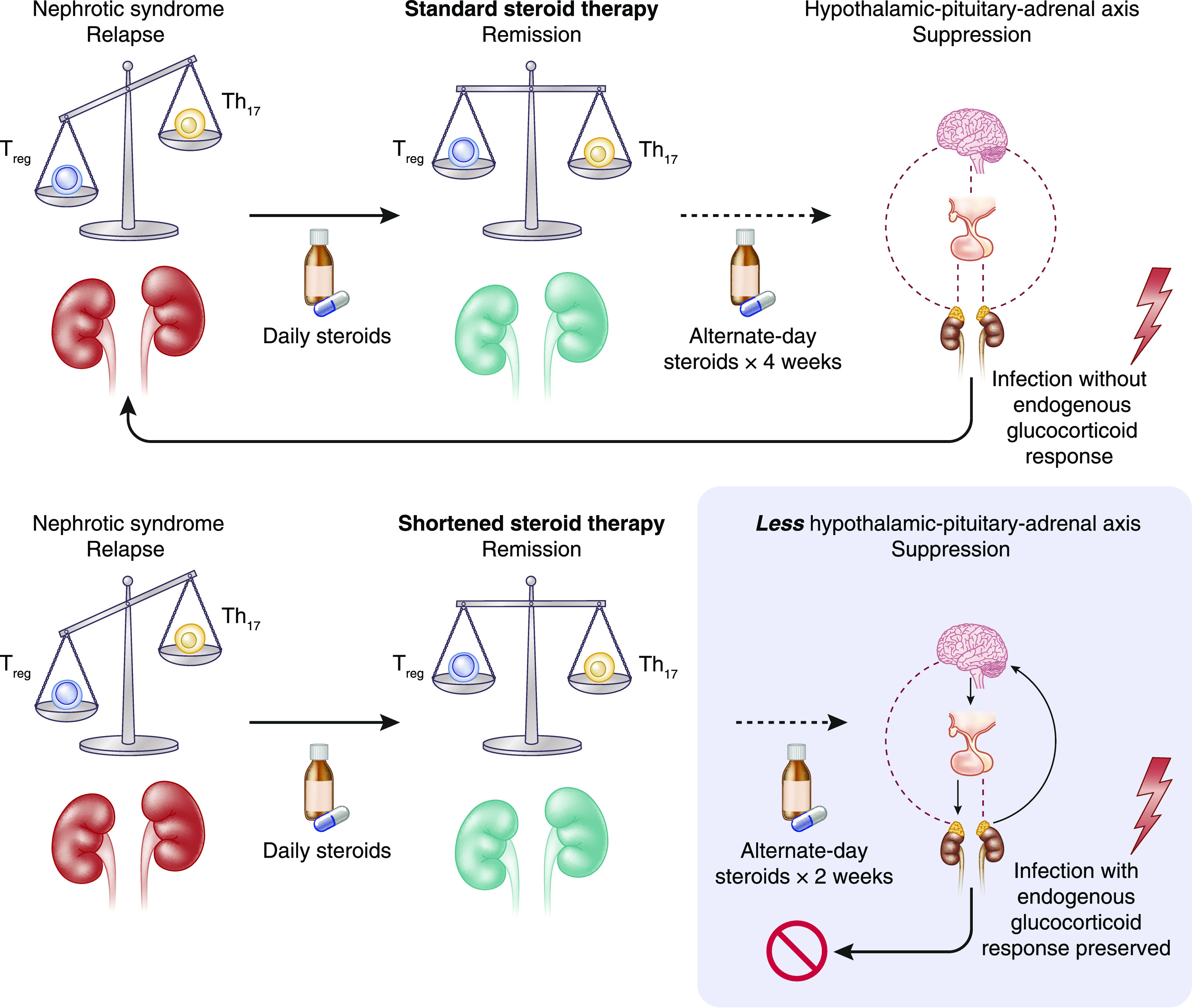

The authors suggested that shorter duration of corticosteroid therapy could potentially lead to a decreased degree of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis suppressive effects (6). The inference from this conceptual framework is that during immunologic challenges such as infection that may trigger relapse, patients who received the shortened therapy course were more likely to respond promptly to the challenges by increased production of endogenous glucocorticoids, thereby preventing relapse (Figure 1). Although clinical adrenal crisis is a rare event in children with nephrotic syndrome who are on prolonged corticosteroid therapy, subclinical suppression of the HPA axis is understudied and under-reported, primarily because of a lack of standardized screening tools (7,8). In a recent study by Abu Bakar et al. (8), the investigators confirmed, through the low-dose Synacthen test, that over a quarter of their patients with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome who received corticosteroids 4–6 weeks before the low-dose Synacthen test demonstrated HPA axis suppression; however, they did not compare frequency of relapse in patients with and without HPA axis suppression. Another study from The Netherlands compared nephrotic syndrome relapse among patients with normal HPA axis function and those with moderate or severe HPA axis suppression (9). The authors reported that the risk of relapse was increased by the degree of HPA axis suppression, as measured by the 2-hour adrenocorticotropic hormone test. The authors suggested that reducing the duration of corticosteroid therapy in patients with HPA axis suppression would help maintain longer remission (9). The limitations of most of the studies examining the role of HPA axis suppression in nephrotic syndrome therapy include small sample size and lack of focus on the standard therapy regimen currently used for the treatment of the initial presentation and relapse of nephrotic syndrome.

Figure 1.

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis suppression from corticosteroid therapy in nephrotic syndrome (NS) can predispose to relapse. T regulatory (Treg) cell and T helper 17 (Th17) cell imbalance is associated with development of nephrotic syndrome and relapse. When nephrotic syndrome is treated with corticosteroids, this re-establishes the proper immunologic balance of Treg and Th17 cells, leading to remission. Prolonged corticosteroid therapy for treatment of nephrotic syndrome leads to HPA axis suppression, so that when a trigger such as an infection arises, the patient is unable to produce enough endogenous glucocorticoids to prevent relapse. When the duration of corticosteroid therapy is shortened, less HPA axis suppression occurs and remission is maintained, even when an immunologic trigger arises.

The exciting findings from the study by Kainth et al. pave the way for additional investigations, including larger studies of shortened and standard course of corticosteroid therapy in nephrotic syndrome relapse, coupled with HPA axis suppression evaluation. These investigations should also address the study’s minor shortcomings by including a greater proportion of young children and a longer follow-up period. Additionally, future studies may be warranted in the initial therapy of nephrotic syndrome, and should attempt to risk-stratify the use of second-line corticosteroid-sparing agents, such as calcineurin inhibitors, antiproliferative agents, and biologics, on the basis of the degree of HPA axis suppression and other biomarkers, even before the development of the frequent relapsing and/or steroid-dependent course. Such study will likely lead to development of individualized guidelines for immunosuppression in nephrotic syndrome. There is much to learn about treating nephrotic syndrome with corticosteroids in children, and we congratulate Kainth et al. for their important study that is likely to change the way we manage children with nephrotic syndrome in the future.

Disclosures

R.A. Gbadegesin reports employment with Duke University Medical Center; consultancy agreements with Keryx Pharmaceutical; and research funding from AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibbs, and Goldfinch Biotech. A.E. Williams reports employment with Duke University Medical Center.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under award R38HL143612 and by the Duke Pediatric Research Scholars Program (A.E. Williams). R.A. Gbadegesin is supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants 5R01DK098135 and 5R01DK094987 and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant 1U01AI152585-01.

Acknowledgments

The content of this article reflects the personal experience and views of the author(s) and should not be considered medical advice or recommendation. The content does not reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or CJASN. Responsibility for the information and views expressed herein lies entirely with the author(s).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related article, “Short-Duration Prednisolone in Children with Nephrotic Syndrome Relapse: A Noninferiority Randomized Controlled Trial,” on pages 225–232.

References

- 1.Iijima K, Sako M, Nozu K: Rituximab for nephrotic syndrome in children. Clin Exp Nephrol 21: 193–202, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ehrich JH, Brodehl J; Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Pädiatrische Nephrologie : Long versus standard prednisone therapy for initial treatment of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in children. Eur J Pediatr 152: 357–361, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noone DG, Iijima K, Parekh R: Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in children. Lancet 392: 61–74, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teeninga N, Kist-van Holthe JE, van Rijswijk N, de Mos NI, Hop WC, Wetzels JF, van der Heijden AJ, Nauta J: Extending prednisolone treatment does not reduce relapses in childhood nephrotic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 149–159, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abeyagunawardena AS, Trompeter RS: Increasing the dose of prednisolone during viral infections reduces the risk of relapse in nephrotic syndrome: A randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child 93: 226–228, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kainth D, Hari P, Sinha A, Pandey S, Bagga A: Short-duration prednisolone in children with nephrotic syndrome relapse: A noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 225–232, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abeyagunawardena AS, Hindmarsh P, Trompeter RS: Adrenocortical suppression increases the risk of relapse in nephrotic syndrome. Arch Dis Child 92: 585–588, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abu Bakar K, Khalil K, Lim YN, Yap YC, Appadurai M, Sidhu S, Lai CS, Anuar Zaini A, Samingan N, Jalaludin MY: Adrenal insufficiency in children with nephrotic syndrome on corticosteroid treatment. Front Pediatr 8: 164, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leisti S, Koskimies O: Risk of relapse in steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome: Effect of stage of post-prednisone adrenocortical suppression. J Pediatr 103: 553–557, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]