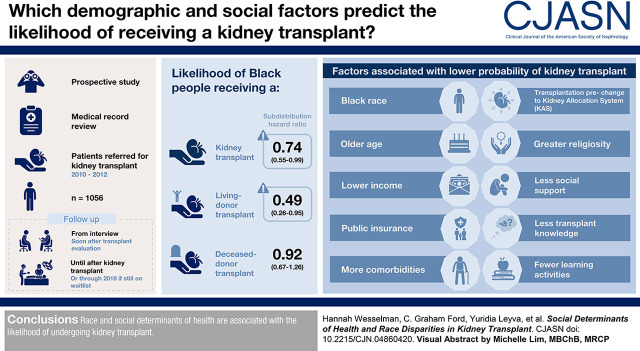

Visual Abstract

Keywords: kidney transplantation, social determinants of health, disparities

Abstract

Background and objectives

Black patients have a higher incidence of kidney failure but lower rate of deceased- and living-donor kidney transplantation compared with White patients, even after taking differences in comorbidities into account. We assessed whether social determinants of health (e.g., demographics, cultural, psychosocial, knowledge factors) could account for race differences in receiving deceased- and living-donor kidney transplantation.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Via medical record review, we prospectively followed 1056 patients referred for kidney transplant (2010–2012), who completed an interview soon after kidney transplant evaluation, until their kidney transplant. We used multivariable competing risk models to estimate the cumulative incidence of receipt of any kidney transplant, deceased-donor transplant, or living-donor transplant, and the factors associated with each outcome.

Results

Even after accounting for social determinants of health, Black patients had a lower likelihood of kidney transplant (subdistribution hazard ratio, 0.74; 95% confidence interval, 0.55 to 0.99) and living-donor transplant (subdistribution hazard ratio, 0.49; 95% confidence interval, 0.26 to 0.95), but not deceased-donor transplant (subdistribution hazard ratio, 0.92; 95% confidence interval, 0.67 to 1.26). Black race, older age, lower income, public insurance, more comorbidities, being transplanted before changes to the Kidney Allocation System, greater religiosity, less social support, less transplant knowledge, and fewer learning activities were each associated with a lower probability of any kidney transplant. Older age, more comorbidities, being transplanted before changes to the Kidney Allocation System, greater religiosity, less social support, and fewer learning activities were each associated with a lower probability of deceased-donor transplant. Black race, older age, lower income, public insurance, higher body mass index, dialysis before kidney transplant, not presenting with a potential living donor, religious objection to living-donor transplant, and less transplant knowledge were each associated with a lower probability of living-donor transplant.

Conclusions

Race and social determinants of health are associated with the likelihood of undergoing kidney transplant.

Introduction

The high morbidity and mortality associated with kidney failure affects individuals and communities, the US economy, and its health care system (1). Patients who are non-Hispanic and Black are four times more likely than patients who are non-Hispanic and White to have kidney disease (1), but only half as likely to undergo kidney transplantation, the optimal treatment for kidney failure (2). Previous studies emphasized the multifactorial nature of disparities in kidney treatment (3). Black patients have disproportionately lower rates of living-donor kidney transplant, which offers superior patient and allograft survival rates compared with deceased-donor kidney transplant (4,5). Racial disparities in kidney transplant persist even after accounting for medical differences (e.g., diabetes, obesity, hypertension), including donor and recipient factors. These findings suggest the need to examine how other factors such as social determinants of health (6), including demographics (7,8), culturally related factors (9,10), transplant knowledge (11), and psychosocial characteristics (12), may contribute to racial disparities in kidney transplantation.

Recently, we found significant racial disparities in waitlisting for transplant (13). Black individuals were 25% less likely to be waitlisted, even after adjusting for medical factors and social determinants of health (13). Although we identified the factors that affect waitlisting, our understanding of disparities associated with receiving a transplant and type of transplant (living or deceased) remains limited. Furthermore, recent work analyzing the implementation of the new Kidney Allocation System (KAS) has noted that decreases in racial disparities of deceased-donor transplant since KAS went into effect were short lived. Persistent disparities remain (14). National data and previous research demonstrate that disparities occur at every stage of the transplant process (i.e., referral, evaluation, transplantation, and post-transplant outcomes) (1,15), but different factors contribute to disparities in waitlisting versus receiving a transplant (2,4,16). Thus, it is important to determine which variables are associated with disparities in receiving a transplant, and the type of transplant received, independent of waitlisting (13,16).

To date, no previous work examined the influence of social determinants of health on disparities in receiving a kidney transplant in a prospective sample followed from evaluation initiation to receiving a transplant, as has been done in health behaviors and outcomes in other diseases (17–19). With few exceptions (8,20–26), little work has focused on transplantation, and what has been published is limited by small sample sizes, cross-sectional design, or a limited number and range of predictors (16,27–29). For example, research using Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients data to model disparities in kidney transplant utilized only cross-sectional and retrospective data (30). Other work (14,29,31) has been limited to predicting disparities in transplant waitlisting with variables collected from national databases or medical records, without predicting time to transplant or type of transplant received. None of these studies assessed patient-reported and other social determinants of health at the time of transplant evaluation, and then followed the patients to predict receiving a transplant and type of transplant received.

We designed our study to address these limitations. We examined the extent to which social determinants of health account for race differences in receiving a kidney transplant and the type of transplant received. By focusing on patients already referred for transplant evaluation, we expand on previous work that examined the disparities present in the referral process and the probability of receiving a transplant (2,9,27,31,32).

Materials and Methods

Study Design

We conducted a prospective cohort study of patients at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) Starzl Transplant Institute. Shortly after their transplant clinic evaluation appointment, participants completed an approximately 70-minute semistructured telephone interview, comprised of questions derived from existing validated measures, including self-reported race (9,33). We tracked patients via their electronic medical record until they either received a kidney transplant (at UPMC or another center) or experienced any of the following outcomes during the follow-up period: death, withdrawal from the waitlist, evaluation ongoing, closed before waitlist, or still awaiting kidney transplant. The Institutional Review Boards at the University of Pittsburgh and the University of New Mexico approved this study.

Study Sample

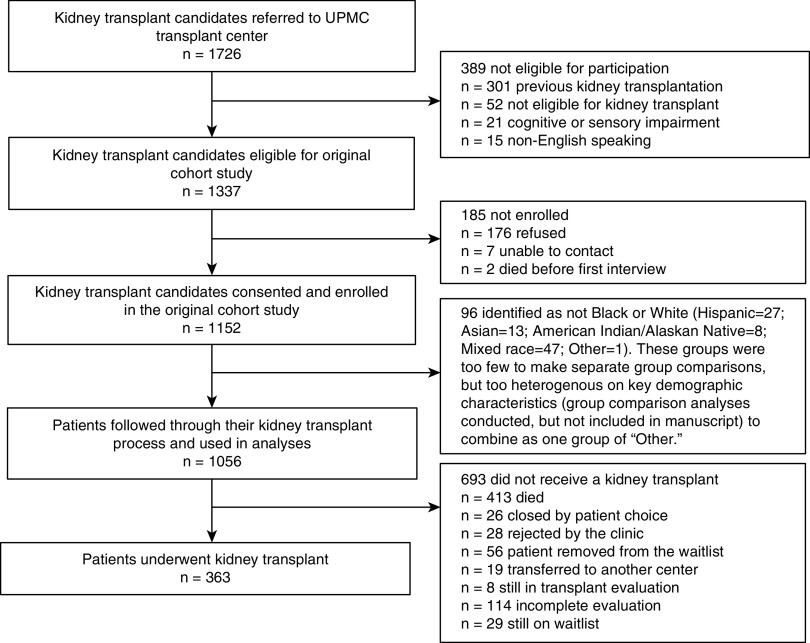

Inclusion criteria were: (1) kidney failure; (2) age 18 years and older; (3) English speaking; and (4) referred for kidney transplant evaluation. Because the majority of US recipients are first-time recipients (1), and to prevent patients’ previous experience with transplant from influencing current outcomes, we excluded patients with a previous history of kidney transplant (but not those with previous nonkidney transplants). Between March 2010 and October 2012, 1726 transplant candidates were referred to the UPMC Starzl Transplant Institute for transplant evaluation. The details regarding included and excluded patients are in Figure 1. Median follow-up time was 2.9 years (range, 1.3–4.7).

Figure 1.

Kidney transplant candidates included and excluded from study cohort.

Independent Variables

Independent variables included demographics, medical factors, culturally related factors, psychosocial characteristics, and transplant knowledge and education (see the complete list of variables in Table 1 and detailed descriptions, ranges, and psychometric properties in Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by transplant status

| Variables | Total | Received a Transplanta | Diedb | Censoredc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=1056) | (n=363) | (n=413) | (n=280) | |

| Demographic characteristicsd | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White, n (%) | 789 (75) | 298 (82) | 309 (75) | 182 (65) |

| Non-Hispanic Black, n (%) | 267 (25) | 65 (18) | 104 (25) | 98 (35) |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 406 (38) | 141 (39) | 146 (35) | 119 (43) |

| Age (in yr), mean (SD) | 57±13 | 52±14 | 61±12 | 56±13 |

| Education (≤high school), n (%) | 496 (47) | 147 (41) | 212 (51) | 137 (49) |

| Household income (<US$50,000), n (%) | 739 (74) | 214 (62) | 316 (81) | 209 (79) |

| Insurance status, n (%) | ||||

| Public only | 277 (26) | 148 (41) | 62 (15) | 67 (24) |

| Private only | 370 (35) | 98 (27) | 152 (37) | 120 (43) |

| Public and private | 400 (38) | 113 (31) | 194 (48) | 93 (33) |

| Occupation (≥skilled manual worker), n (%) | 512 (49) | 190 (52) | 201 (49) | 121 (43) |

| Marital status (not married), n (%) | 512 (48) | 171 (47) | 195 (47) | 146 (52) |

| Final status after KAS, n (%)e | 428 (41) | 130 (36) | 166 (40) | 132 (47) |

| Medical factors | ||||

| BMI, mean (SD) | 29.6±6.3 | 29.3±6.2 | 29.6±6.3 | 29.9±6.3 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 4.0 (2.0–4.0) | 5.0 (4.0–6.0) | 4.0 (2.0–5.0) |

| Type of dialysis, n (%) | ||||

| None | 366 (35) | 168 (46) | 87 (21) | 111 (39) |

| Hemodialysis | 583 (55) | 158 (44) | 277 (67) | 148 (53) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 107 (10) | 37 (10) | 49 (12) | 21 (8) |

| Dialysis duration in yr, median (IQR) | 0.2 (0.0–0.7) | 0.2 (0.0–0.7) | 0.3 (0.1–0.9) | 0.2 (0.0–0.7) |

| Burden of kidney disease (range: 1–5), median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0–4.7) | 3.7 (3.0–4.3) | 4.0 (3.0–4.7) | 3.7 (3.0–4.7) |

| No. of potential donors, median (IQR) | 17 (11–29) | 20 (12–30) | 15 (10–28) | 18 (10–27) |

| Have a potential living donor at T1 (yes), n (%) | 556 (54) | 225 (64) | 183 (46) | 148 (54) |

| Cultural factors | ||||

| Experience of discrimination (any), n (%) | 268 (26) | 70 (19) | 119 (29) | 79 (28) |

| Perceived racism (range: 1–5), median (IQR) | 2.3 (2.0–2.8) | 2.3 (2.0–2.5) | 2.3 (2.0–2.8) | 2.4 (2.0–2.8) |

| Medical mistrust (range: 1–5), mean (SD) | 2.4±0.5 | 2.4±0.5 | 2.5±0.5 | 2.5±0.5 |

| Trust in physician (range: 1–5), mean (SD) | 2.2±0.5 | 2.2±0.5 | 2.2±0.5 | 2.2±0.5 |

| Family loyalty (range: 8–80), mean (SD) | 49.8±9.4 | 49.5±9.6 | 49.6±9.2 | 50.7±9.5 |

| Religious objection to living-donor kidney transplant, n (%) | ||||

| No objection | 361 (35) | 139 (39) | 135 (34) | 87 (31) |

| Mixed (neutral + no objection) | 100 (10) | 32 (9) | 50 (12) | 18 (6) |

| Any objection | 580 (56) | 189 (53) | 218 (54) | 173 (62) |

| Overall religiosity (range: 1–9), median (IQR) | 7.0 (4.5–9.0) | 6.0 (4.0–8.5) | 7.0 (5.0–9.0) | 7.5 (5.0–9.0) |

| Psychosocial characteristics | ||||

| Social support (range: 12–48), median (IQR) | 44.0 (39.0–48.0) | 45.0 (41.0–48.0) | 44.0 (38.0–47.0) | 43.0 (37.0–47.0) |

| Self-esteem (range: 1–4), median (IQR) | 3.1 (2.9–3.5) | 3.1 (2.9–3.6) | 3.0 (2.8–3.5) | 3.1 (2.8–3.5) |

| Mastery (range: 1–4), median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.7–3.1) | 3.0 (2.9–3.1) | 2.9 (2.7–3.1) | 3.0 (2.7–3.1) |

| Internal locus of control (range: 1–6), mean (SD) | 4.0±1.1 | 3.8±1.1 | 4.1±1.0 | 4.1±1.1 |

| External locus of control (range: 1–6), mean (SD) | 3.4±0.8 | 3.3±0.7 | 3.5±0.9 | 3.5±0.8 |

| Anxiety (≥moderate), n (%) | 47 (4) | 13 (4) | 21 (5) | 13 (5) |

| Depression (≥moderate), n (%) | 42 (4) | 11 (3) | 20 (5) | 11 (4) |

| Transplant knowledge and education | ||||

| Transplant knowledge (range: 0–27), median (IQR) | 22.0 (20–23.0) | 23.0 (21.0–24.0) | 21.0 (19.0–23.0) | 21.0 (19.0–23.0) |

| No. learning activities (range: 0–8), median (IQR) | 5.0 (3.0–6.0) | 5.0 (4.0–6.0) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) |

| Total h of learning activities (range: 0–185), median (IQR) | 10.3 (6.0–21.5) | 12.0 (7.0–29.0) | 10.0 (5.3–20.5) | 9.5 (4.5–19.0) |

| Transplant concerns (range: 0–30), mean (SD) | 10.9±4.7 | 10.9±4.8 | 10.9±4.5 | 10.8±4.9 |

| Donor preference, n (%) | ||||

| Deceased donor | 135 (13) | 46 (13) | 50 (12) | 39 (14) |

| Living donor | 815 (77) | 287 (79) | 313 (76) | 215 (77) |

| No preference | 104 (10) | 29 (8) | 49 (12) | 26 (9) |

| Willing to accept living donor volunteer, n (%) | 934 (90) | 333 (93) | 355 (88) | 246 (90) |

| Willing to ask for living donor donation, n (%) | 582 (57) | 205 (58) | 222 (56) | 155 (57) |

| Years from evaluation to final follow-up, mean (range) | 3.1 (0.003–8.5) | 2.8 (0.07–7.7) | 3.3 (0.06–8.2) | 3.4 (0.003–8.5) |

KAS, Kidney Allocation System; IQR, interquartile range, i.e., the interval between the 25th and 75th percentiles; UPMC, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center; UNOS, United Network for Organ Sharing.

Includes receiving a living-donor transplant at UPMC (n=109; White=100, Black=9), deceased-donor transplant at UPMC (n=218; White=167, Black=51), living-donor transplant at another center (n=15; White=14, Black=1), deceased-donor transplant at another center (n=14; White=12, Black=2), unknown transplant type at another center (n=7; White=5, Black=2). Unknown transplant type because UPMC does not have access to the UNOS data for other transplant centers, and participants could not be reached for verification, despite several attempts.

Died before or after waitlist but before receiving a transplant.

Censoring includes closed by patient choice (n=26–13 before waitlisting and 13 after waitlisting), clinic rejected (n=28), clinic removed patient from waiting list (n=56), transferred to another center (n=19), still in transplant evaluation (n=8), incomplete evaluation (n=114), or still on waitlist (n=29).

n=1 missing for transplant concerns; n=2 missing for occupation, transplant knowledge, donor preference; n=4 missing for family loyalty score; n=5 missing in medical mistrust index, trust in physician; n=6 missing in total social support; n=7 missing for internal and external locus of control, experienced discrimination in health care; n=8 missing for self-esteem scale; n=9 missing for total h engaged in learning activities; n=9 missing for insurance type; n=11 missing for racism in health care; n=15 missing for religious objection to living-donor kidney transplant; n=19 for willing to accept living donor volunteer; n=31 for having living donor; n=32 for willing to ask for living donor donation; n=53 missing/unknown for income.

Final status after KAS refers to whether the patient’s ultimate outcome (i.e., transplant, died, censored) occurred either before or after the KAS policy changes of 2014 to all of the tables that include this variable.

Outcome Variables

Outcome variables were time from evaluation initiation to receiving a transplant, and type of transplant received. We accounted for all other possible outcomes, which resulted in 13 potential categories:

Received living-donor transplant: patient received a living-donor transplant (end point = transplant).

Received deceased-donor transplant: patient received a deceased-donor transplant (end point = transplant).

Transplanted at another center, transplant type unknown: patient received a transplant at a different center, but transplant type (living or deceased) unknown (end point = transplant receipt if known or date UPMC was informed of transplant, but type unknown because UPMC does not have access to the United Network for Organ Sharing [UNOS] data for other transplant centers, and participants could not be reached for verification, despite several attempts, n=7).

Died before waitlisting: patient died before completing the transplant evaluation; did not receive a kidney transplant (end point = death).

Died after waitlisting: patient died while on the UNOS waitlist; did not receive a transplant (end point = death).

Still on waitlist: patient was accepted for transplant, added to the UNOS waitlist, and was still on the waitlist at the time of the final medical record review (active and inactive; end point = final medical record review).

Evaluation still open: patient still in transplant evaluation (end point = final medical record review).

Closed due to patient choice before waitlist: patient withdrew from the transplant evaluation process before being listed for transplant (end point = closure).

Closed due to patient choice after waitlist: patient withdrew from the UNOS waitlist after completing evaluation (end point = UNOS waitlist removal).

Closed due to incomplete evaluation: patient started an evaluation but was closed before being accepted or rejected due to incomplete evaluation (end point = closure).

Ineligible for transplant: patient completed the evaluation, but was determined ineligible by the transplant team (end point = ineligibility).

Transplant program removed the patient from the waitlist: the transplant program removed the patient from the UNOS waitlist (end point = removal).

Transferred to waitlist at another center: patient remained on the UNOS waitlist, but was no longer pursuing a transplant at UPMC (end point = transfer).

Statistical Analyses

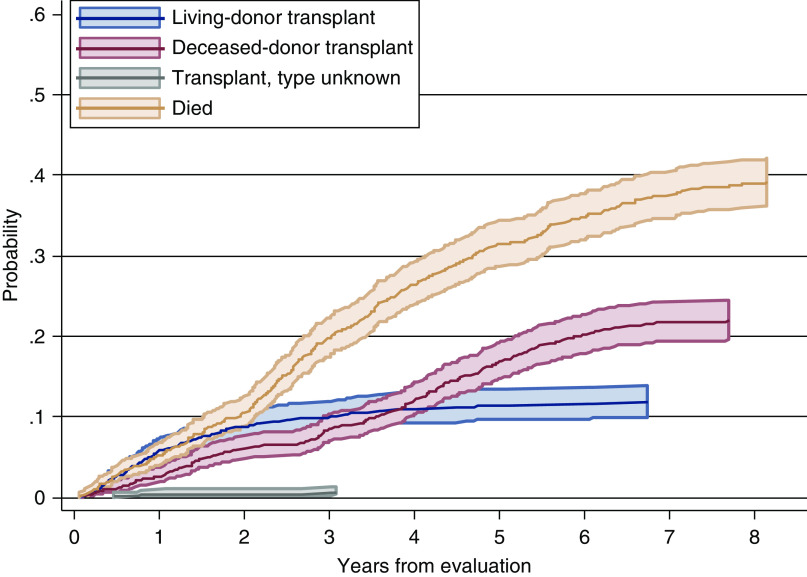

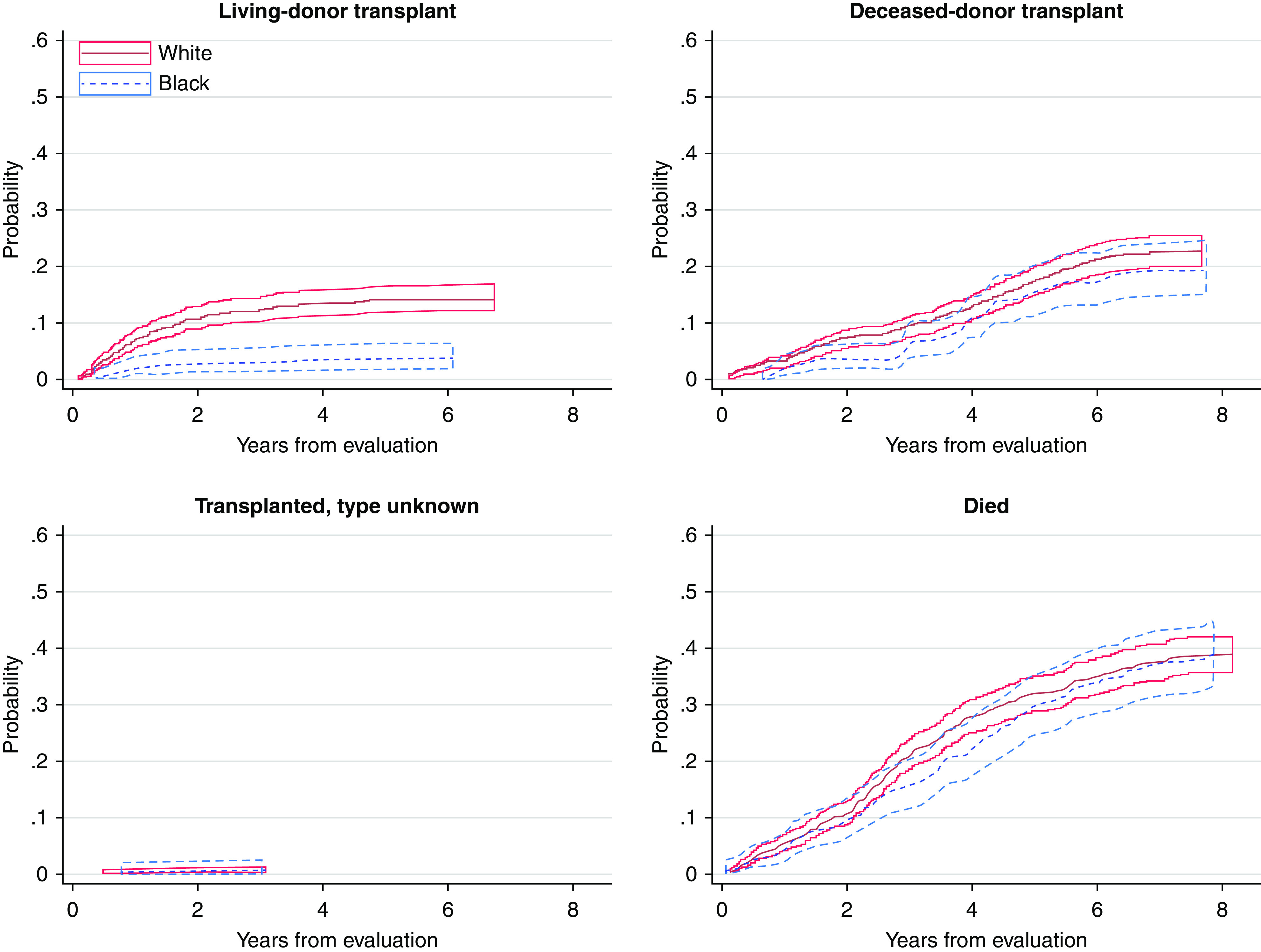

We summarized categorical variables using frequencies (percentages), normally distributed continuous covariates using mean (SD), and non-normally distributed continuous covariates using median (interquartile range, the interval between the 25th and 75th percentiles) across different transplant status groups. To visualize the probability of events, we calculated an unadjusted cumulative incidence function (CIF), and created a figure for each outcome event (any transplant, living or deceased) as a function of years from evaluation. Finally, given its important effect on outcomes, we created figures of the unadjusted CIF for each outcome event by race to examine the effect of the 2014 KAS policy changes (14,34). We used a casewise deletion strategy for individuals missing any independent or outcome variable (see Table 1 notes for specific missing data details).

Although our study is not “predictive modeling,” a statistical technique in which probability and data mining are applied to an unknown event to predict outcomes (35,36), it is a longitudinal study (37,38), an approach allowing us to determine how variables assessed at one time point predict outcomes assessed at a subsequent time point. We performed three separate competing risk analyses to examine the association between baseline risk factors and CIF of the three kidney transplant outcomes (any transplant, living, or deceased) (39). For time to receive any kidney transplant, we treated Categories 1, 2, and 3 as the main outcome, and Categories 4 and 5 as competing events. For deceased-donor transplant, we treated Category 2 as the main outcome, and Categories 1, 4, and 5 as competing events. For living-donor transplant, we treated Category 1 as the main outcome, and Categories 2, 4, and 5 as competing events. For the analysis of CIF of deceased-donor and living-donor transplant, we treated Category 3 as missing due to lack of data on the type of kidney transplant received (n=7). In all of the analyses, we treated Categories 6–13 as noninformative censoring.

To determine how social determinants of health accounted for race differences in transplant outcomes, we first fit univariable Fine-Gray (40) models, which estimate the unadjusted association between independent variables and the CIF of the outcome of interest. Then, we constructed multivariable Fine-Gray models for each primary outcome by including candidate variables that were significant at the level of P<0.10 in the univariable model. We then performed variable selection using a backward procedure, removing variables with the highest P value >0.05 sequentially, unless they had subdistribution hazard ratios (SHRs) <0.5 or >2.0, until all remaining covariates were significant at the level of P<0.05 (41). We also examined multicollinearity among variables using variance inflation factors with a cutoff of 5, but found no such problems (data not shown). For each outcome, Model 1 included race/ethnicity as the only covariate; Model 2 included race/ethnicity and adjusted for demographics and medical/health factors; Model 3 included the covariates from Model 2 plus a variable to account for transplantation occurring before or after KAS, and the cultural, psychosocial, transplant knowledge, and education factors.

Results

Descriptive Statistics by Transplant Status

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of covariates grouped by outcome (covariates grouped by race are available in Ng et al. 2019). Of the 789 White patients, 298 (38%) received a transplant, 309 (39%) died before transplant, and 183 (23%) were censored. Of the 267 Black patients, 65 (24%) received a transplant, 104 (39%) died before transplant, and 98 (37%) were censored for the same reasons listed above (see Table 1, Note A for a breakdown of transplant type by race).

Figure 2 shows that the cumulative incidence of receiving a living-donor transplant increased quickly in the first 2 years and stabilized thereafter, but deceased-donor transplant steadily increased over time. Figure 3 displays the persistent disparity between White and Black patients in living-donor transplant, and but no such disparity in deceased-donor transplant.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence probability by event status, with pointwise 95% confidence interval.

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence probability by event status separated by race (White and Black), with pointwise 95% confidence interval.

Multivariable Association Between Independent Variables and Receiving a Transplant

Tables 2–4 include the final multivariable results for each outcome (see Supplemental Table 2 for results of the univariable models). The value of each significant SHR for a given continuous variable indicates the likelihood of the outcome with a one-unit change in that variable.

Table 2.

Fine-Gray proportional subdistribution hazard model for time from evaluation to receiving any transplanta (n=997)b

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subdistribution Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Subdistribution Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Subdistribution Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Model 1 | ||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.60 | 0.46 to 0.78 | 0.67 | 0.51 to 0.90 | 0.74 | 0.55 to 0.99 |

| Model 2 | ||||||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age (in yr) | 0.97 | 0.96 to 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.97 to 0.99 | ||

| Household income (<US$50,000) | 0.58 | 0.45 to 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.50 to 0.85 | ||

| Insurance status | ||||||

| Private only | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||||

| Public only | 0.62 | 0.46 to 0.83 | 0.60 | 0.44 to 0.80 | ||

| Public and private | 0.75 | 0.57 to 0.99 | 0.67 | 0.52 to 0.88 | ||

| Medical factors | ||||||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.82 | 0.76 to 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.78 to 0.91 | ||

| Type of dialysis | ||||||

| None | 1 (ref) | |||||

| Hemodialysis | 0.72 | 0.56 to 0.91 | ||||

| Peritoneal dialysis | 0.74 | 0.50 to 1.10 | ||||

| Model 3 | ||||||

| Final status after KASc | 2.38 | 1.77 to 3.19 | ||||

| Cultural factors | ||||||

| Overall religiosityd | 0.96 | 0.91 to1.00 | ||||

| Psychosocial characteristics | ||||||

| Social supportd | 1.04 | 1.01 to 1.06 | ||||

| Transplant knowledge and education | ||||||

| Transplant knowledged | 1.06 | 1.00 to 1.11 | ||||

| No. learning activitiesd | 1.08 | 1.01 to 1.16 | ||||

Higher value, greater amount (or higher score) on a particular variable. KAS, Kidney Allocation System; SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio.

Main event, received a transplant; competing event, died, censoring, still on waitlist or other removal.

Sample size used for Models 1, 2, and 3: n=997 (i.e., those with complete data on all variables; 346 received a transplant, 385 died, 266 censored).

Final status after KAS refers to whether the patient’s ultimate outcome (i.e., transplant, died, censored) occurred either before or after the KAS policy changes of 2014 to all of the tables that include this variable.

The SHR for these variables are per one-point higher in each scale.

Table 3.

Fine-Gray proportional subdistribution hazard model for time from evaluation to receiving a deceased-donor kidney transplanta (n=1036)b

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subdistribution Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Subdistribution Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Subdistribution Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Model 1 | ||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.91 | 0.67 to 1.23 | 0.92 | 0.68 to 1.24 | 0.92 | 0.67 to 1.26 |

| Model 2 | ||||||

| Other demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age (in yr) | 0.98 | 0.97 to 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.00 | ||

| Medical factors | ||||||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.82 | 0.75 to 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.77 to 0.93 | ||

| Model 3 | ||||||

| Final status after KASc | 4.17 | 3.03 to 5.73 | ||||

| Cultural factors | ||||||

| Overall religiosityd | 0.93 | 0.88 to 0.98 | ||||

| Psychosocial characteristics | ||||||

| Social supportd | 1.03 | 1.00 to 1.05 | ||||

| Transplant knowledge and education | ||||||

| Number of learning activitiesd | 1.10 | 1.02 to 1.19 | ||||

Higher value, greater amount (or higher score) on a particular variable. KAS, Kidney Allocation System; DDKT, deceased-donor kidney transplant; LDKT, living-donor kidney transplant; SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio.

Main event, received DDKT; competing event, LDKT, died; censoring, still on waitlist or other removal; missing, unknown donor type.

Sample size used for Models 1, 2, and 3: n=1036 (i.e., those with complete data on all variables; 231 received a transplant, 525 died, 280 censored).

Final status after KAS refers to whether the patient’s ultimate outcome (i.e., transplant, died, censored) occurred either before or after the KAS policy changes of 2014 to all of the tables that include this variable.

The SHR for these variables are per one-point higher in each scale.

Table 4.

Fine-Gray proportional subdistribution hazards model for time from evaluation to receiving a living-donor kidney transplanta (n=961)b

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subdistribution Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Subdistribution Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Subdistribution Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

| Model 1 | |||||||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.28 | 0.14 to 0.53 | 0.42 | 0.22 to 0.83 | 0.49 | 0.26 to 0.95 | |

| Model 2 | |||||||

| Other demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age (in yr) | 0.98 | 0.96 to 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.96 to 0.99 | |||

| Household income (<US$50,000) | 0.52 | 0.34 to 0.81 | 0.59 | 0.38 to 0.92 | |||

| Insurance status | |||||||

| Private only | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |||||

| Public only | 0.31 | 0.16 to 0.58 | 0.32 | 0.17 to 0.60 | |||

| Public and private | 0.47 | 0.29 to 0.76 | 0.46 | 0.28 to 0.75 | |||

| Medical factors | |||||||

| BMI | 0.97 | 0.94 to 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.93 to 0.99 | |||

| Type of dialysis | |||||||

| None | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |||||

| Hemodialysis | 0.49 | 0.31 to 0.79 | 0.52 | 0.33 to 0.84 | |||

| Peritoneal dialysis | 0.43 | 0.21 to 0.88 | 0.43 | 0.21 to 0.86 | |||

| Have a potential living donor at T1 (yes) | 3.98 | 2.34 to 6.79 | 3.67 | 2.15 to 6.26 | |||

| Model 3 | |||||||

| Cultural factors | |||||||

| Religious objection to living-donor kidney transplant | 0.02 | ||||||

| No objection | 1 (ref) | ||||||

| Mixed | 0.45 | 0.19 to 1.04 | |||||

| Any objection | 0.62 | 0.42 to 0.92 | |||||

| Transplant knowledge and education | |||||||

| Transplant knowledgec | 1.12 | 1.02 to 1.23 | |||||

Higher value, greater amount (or higher score) on a particular variable. BMI, body mass index; DDKT, deceased-donor kidney transplant; LDKT, living-donor kidney transplant; SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio.

Main event, received LDKT; competing event, DDKT, died; censoring, still on waitlist or other removal; missing, unknown donor type.

Sample size used for Models 1, 2, and 3: n=961 (i.e., those with complete data on all variables; 117 received a transplant, 585 died, 259 censored).

The SHR for this variable is per one-point higher in the scale.

For receipt of any type of kidney transplant (Table 2), Black race was associated with a lower probability of transplant, although there was a modest attenuation of the relationship with the inclusion of other factors. With the addition of demographics, medical, cultural, psychosocial, and knowledge factors, we found that Black race, older age, lower income, public insurance, having more comorbidities, being transplanted pre-KAS, higher religiosity, less social support, less transplant knowledge, and engaging in fewer learning activities were each associated with a lower probability of any kidney transplant.

For deceased-donor transplant (Table 3), race was NS in the univariable results or when forced into the model for multivariable analyses. Final model results show that older age, having more comorbidities, being transplanted pre-KAS, higher religiosity, less social support, and engaging in fewer learning activities were each associated with a lower probability of deceased-donor transplant. Because our analysis showed no racial disparities for deceased-donor transplant (as expected given US data [1]), we conducted a sensitivity analysis using medical record data to determine patient status in 2014 (pre-KAS) and in 2018 (post-KAS). We treated KAS as an exposure variable because the policy was uniformly applied to all patients. For deceased-donor transplant outcomes, we found that racial differences decreased from 2014 to 2018 (SHR 0.68 [95% CI, 0.41 to 1.15]; P=0.15 for 2014; SHR, 0.91 [95% CI, 0.68 to 1.24]; P=0.53 for 2018). However, this result was not a statistically significant racial disparity at either time point.

For living-donor transplant (Table 4), Black race was associated with a lower probability of transplant in univariable and multivariable analyses. Final model results show that older age, lower income, public insurance, higher body mass index, being on dialysis, not presenting with a potential living donor at evaluation, having religious objections to living-donor transplant, and less transplant knowledge were each associated with a lower probability of receiving living-donor transplant (13).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first prospective examination of the influence of a comprehensive set of social determinants of health on undergoing kidney transplantation in a large population (14–16,25,29,31,42,43). In our study of 1056 patients evaluated for transplant, we found that racial disparities in transplant persisted in overall rates of transplant and living-donor transplant, but not for deceased-donor transplant, even after controlling for medical factors and age, income, presenting to evaluation with a potential living donor, KAS implementation in 2014, social support, and transplant knowledge. Although our sample of patients was older and had a larger proportion of White patients than the US population of transplant candidates, it was equivalent in the proportion of women and patients on dialysis (1). It also builds on our previous study (13), which focused on disparities in waitlisting for transplant. The current work tracked patients through 2018 to study disparities in receiving a kidney transplant and the type of transplant received, distinct steps in the transplantation process that have been shown to have different rates of disparities, with potentially different factors influencing outcomes at those steps (1,2,4,15,16,25).

In line with previous work, we found that Black patients were more than 50% less likely to receive a living-donor transplant (9,15,27,44). Although our previous research demonstrated a lower likelihood of waitlisting for Black patients (13), we found no race differences in receiving a deceased-donor transplant. This finding is most likely due to the influence of KAS and other national policy changes (e.g., elimination of HLA-B matching requirement, credit for time on dialysis) (14,34) on deceased-donor transplant, thus making all patients more likely to receive a transplant, regardless of race.

Consistent with secondary cross-sectional analyses of national data examining kidney transplant outcomes that showed a bolus effect on reducing deceased-donor transplant disparities post-KAS changes (14,43), our prospective cohort showed a reduction in racial differences for deceased-donor transplant. In our case, however, the racial difference was NS at either time point (see Figure 3). As expected, the revision of the KAS policy in December 2014 (which focused on policies regarding deceased organ allocation) affected rates of deceased-donor transplant but not living-donor transplant. Thus, Figure 3 also demonstrates that living-donor transplant disparities persisted across the entire period. Being transplanted after KAS implementation increased the likelihood of overall transplant and deceased-donor transplant (Tables 2 and 3). This study confirms previous work (34) regarding the notable influence of KAS on transplant outcomes and reduction of racial disparities.

In addition to variables known to be associated with disparities in transplant outcomes (e.g., age, body mass index, comorbid conditions such as diabetes and heart disease, dialysis, income or insurance status) (7,27,33,45,46), we identified several social determinants of health that were associated with type of transplant received, including religiosity, social support, and transplant knowledge. Religious objection to living-donor transplant and overall religiosity were both significant independent variables for our patient population. Patients expressing religious objections to living-donor transplant were significantly less likely to receive living-donor transplant. If these individuals felt that their faith community would not agree with their transplant choice, this objection would logically play a major role in their choice of whether to proceed with transplantation (9,47). Transplant teams should consider the utility of screening for religious objections to kidney transplant and have resources available to inform patients about the support of organ donation from the governing bodies of the major world religions (48).

Similar to the benefits of a strong sense of social support found in other clinical and community-dwelling populations (49,50), we found that a sense of greater social support was associated with a higher likelihood of any kidney transplant and deceased-donor transplant. Prior work demonstrated that patients may not pursue transplant for fear of discussing the topic with their friends and family (51). We believe that social support is an asset because it may minimize these fears and lead to higher rates of transplant, supporting the notion that strong social support enables patients to attend to their health care needs. Further, a sense of social support can ensure that patients receive a transplant in a timely manner and the post-transplant care they need (52–54). Other studies suggest social support is associated with higher rates of patients completing pretransplant evaluations (55) and the rate of transplant waitlisting for disadvantaged patients (56). Although social support was not significantly associated with living-donor transplant, we speculate that presenting with a potential living donor at transplant evaluation is, arguably, one of the strongest forms of social support one person can provide to another. This association left little room for social support to stand out as a significant variable associated with living-donor transplant.

Finally, we found that those with greater transplant knowledge or those who engaged in more learning activities were more likely to receive any kidney transplant, deceased-donor transplant, or living-donor transplant. These outcomes support our previous research (9,13,17,33), and others’ work (51,57–59), demonstrating the importance of transplant knowledge to increase rates of transplantation and improve overall patient experience (44). It also suggests that living-donor transplant rates could increase with the implementation of living-donor transplant educational programming that encourages individuals to identify potential living donors (11,51,59,60).

Ours was a single-center study, and the significant independent variables we identified may not generalize to patients at all transplant centers. However, this study highlighted the need to focus on social determinants of health in addition to race to reduce disparity in receiving a kidney transplant. This need would exist in transplant centers that experience any racial disparities, regardless of specific racial or ethnic composition. A second limitation was the lack of data on transplant type (living or deceased donor) for seven of our 1056 participants. However, when we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding those with an unknown transplant type, we found no difference for the reported results (see Supplemental Table 3). Further, we did not distinguish between active and inactive patients on the waitlist, and were unable to determine racial differences in the proportion of inactive patients.

In addition, when examining medical covariates, we did not examine and control for living donor genotypes as a possible covariate of disparities for living-donor transplant. Genotyping of potential living donors for the APOL1 kidney risk variant remains a controversial issue and could further perpetuate racial disparity in living-donor transplant between Black and White patients (61,62). However, genotyping of potential living donors was not in standard practice at UPMC during the time of this study, and thus could not have contributed to the racial disparity seen in our living-donor transplant results, as no living donor was deemed ineligible due to their APOL1 status. Similarly, we did not include panel reactive antibodies (PRA), which may contribute to racial ethnic differences in deceased-donor transplant, as Black patients tend to have higher antibody levels (32), in our primary analyses. These data were not collected routinely at UPMC during evaluation and were not considered among the criteria for transplant acceptance by the team. Given that our goal was to determine which variables available at evaluation are associated with type of transplant received, and in line with other research focused on this research question (16), PRA would not fit these criteria. However, because these values are important to the clinical evaluation of patients accepted for transplant, and to the extent that other centers continue to observe racial differences in deceased-donor transplant, we added PRA and blood type to our primary analyses in Supplemental Tables 4–8 so that interested readers can explore those variables in this subset of patients. Adding these covariates did not change the overall effect of the key social determinants of health identified in our main analyses. However, their statistical significance decreased due to the smaller sample size.

Reasons for disparities in transplant are complex. Examining medical and social determinants of health in recipients and donors are equally important for these efforts. Additional factors that warrant consideration in future studies of social determinants of transplant disparities include time from kidney failure diagnosis to referral, county/state of residence, family adaptability (63), quantifying risks to potential living donors (64–68), and perceived urgency by patients and potential donors.

Our data suggest a critical need for transplant centers to identify and intervene on social determinants for at-risk populations. As previous research suggests, the most effective programs may include kidney transplant education, providing community-based workshops on kidney transplant and living donation, strengthening patients’ social support networks, and deploying media campaigns to increase awareness of transplant options (11,51,60). This body of work offers a springboard for development of new interventions that promote equitable and effective transplantation care for all patients with kidney failure. Developing interventions focused on transplant knowledge, religious objection to living-donor transplant, and social support may enhance equal access to kidney transplant because transplant teams can use these risk factors to target patients who may need more support to ensure they receive a transplant.

Disclosures

All authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Work on this project was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant R01DK081325, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant UL1 TR001857, and Dialysis Clinic Inc. grant DCI C-3924.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors express their profound gratitude to the participants of this study, without whom this work would not have been possible.

Dr. Larissa Myaskovsky, Dr. Mark L. Unruh, Dr. Mary Amanda Dew, and Dr. Ron Shapiro designed the study; Ms. Emilee Croswell, Dr. John R. Pleis, and Ms. Kellee Kendall conducted the study and maintained the data; Dr. Chung-Chou H. Chang, Dr. Larissa Myaskovsky, Dr. Xingyuan Li, and Ms. Yuridia Leyva analyzed the data and made the figures; Mr. C. Graham Ford, Dr. Chung-Chou H. Chang, Ms. Emilee Croswell, Ms. Hannah Wesselman, Dr. John R. Pleis, Ms. Kellee Kendall, Dr. Larissa Myaskovsk, Dr. Mark L. Unruh, Dr. Mary Amanda Dew, Dr. Ron Shapiro, Dr. Xingyuan Li, Dr. Yue Harn Ng, and Ms. Yuridia Leyva drafted and revised the paper; all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related Patient Voice, “Barriers to Kidney Transplantation in Racial/Ethnic Minorities,” on pages 177–178.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.04860420/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Potential independent variables associated with transplant and type of transplant received.

Supplemental Table 2. Univariable Fine-Gray proportional subdistribution hazard model for time from evaluation to transplant.

Supplemental Table 3. Sensitivity analysis: Fine-Gray proportional subdistribution hazard model for time from evaluation to transplant excluding patients who had unknown transplant type (n=7 of 1056).

Supplemental Table 4. Blood group and panel reactive antibodies (PRA) by transplant status.

Supplemental Table 5. Univariable Fine-Gray proportional subdistribution hazard model for time from evaluation to transplant: blood group and PRA.

Supplemental Table 6. Fine-Gray proportional subdistribution hazards model for time from evaluation to receiving any transplant: blood group and PRA.

Supplemental Table 7. Fine-Gray proportional subdistribution hazards model for time from evaluation to receiving a deceased-donor kidney transplant: blood group and PRA.

Supplemental Table 8. Fine-Gray proportional subdistribution hazards model for time from evaluation to receiving a living-donor kidney transplant: blood group and PRA.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System : 2018 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taber DJ, Gebregziabher M, Hunt KJ, Srinivas T, Chavin KD, Baliga PK, Egede LE: Twenty years of evolving trends in racial disparities for adult kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Int 90: 878–887, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powe NR, Melamed ML: Racial disparities in the optimal delivery of chronic kidney disease care. Med Clin North Am 89: 475–488, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Purnell TS, Xu P, Leca N, Hall YN: Racial differences in determinants of live donor kidney transplantation in the United States. Am J Transplant 13: 1557–1565, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakkera HA, O’Hare AM, Johansen KL, Hynes D, Stroupe K, Colin PM, Chertow GM: Influence of race on kidney transplant outcomes within and outside the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 269–277, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion : Healthy People 2020. topics and objectives: Social determinants of health. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health. Accessed November 1, 2019

- 7.Schold JD, Gregg JA, Harman JS, Hall AG, Patton PR, Meier-Kriesche H-U: Barriers to evaluation and wait listing for kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 1760–1767, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Axelrod DA, Dzebisashvili N, Schnitzler MA, Salvalaggio PR, Segev DL, Gentry SE, Tuttle-Newhall J, Lentine KL: The interplay of socioeconomic status, distance to center, and interdonor service area travel on kidney transplant access and outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 2276–2288, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myaskovsky L, Almario Doebler D, Posluszny DM, Dew MA, Unruh M, Fried LF, Switzer GE, Kim S, Chang CC, Ramkumar M, Shapiro R: Perceived discrimination predicts longer time to be accepted for kidney transplant. Transplantation 93: 423–429, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warsame F, Haugen CE, Ying H, Garonzik-Wang JM, Desai NM, Hall RK, Kambhampati R, Crews DC, Purnell TS, Segev DL, McAdams-DeMarco MA: Limited health literacy and adverse outcomes among kidney transplant candidates. Am J Transplant 19: 457–465, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Kaplan B, Howard RJ: A randomized trial of a home-based educational approach to increase live donor kidney transplantation: Effects in Blacks and Whites. Am J Kidney Dis 51: 663–670, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chilcot J, Spencer BW, Maple H, Mamode N: Depression and kidney transplantation. Transplantation 97: 717–721, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng Y-H, Pankratz VS, Leyva Y, Ford CG, leis JR, Kendall K, Croswell E, Dew MA, Shapiro R, Switzer GE, Unruh ML, Myaskovsky L: Does racial disparity in kidney transplant waitlisting persist after accounting for social determinants of health? Transplantation 104: 1445–1455, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Melanson TA, Plantinga LC, Basu M, Pastan SO, Mohan S, Howard DH, Hockenberry JM, Garber MD, Patzer RE: Racial/ethnic disparities in waitlisting for deceased donor kidney transplantation 1 year after implementation of the new national kidney allocation system. Am J Transplant 18: 1936–1946, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harding K, Mersha TB, Pham PT, Waterman AD, Webb FA, Vassalotti JA, Nicholas SB: Health disparities in kidney transplantation for African Americans. Am J Nephrol 46: 165–175, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy KA, Jackson JW, Purnell TS, Shaffer AA, Haugen CE, Chu NM, Crews DC, Norman SP, Segev DL, McAdams-DeMarco MA: Association of socioeconomic status and comorbidities with racial disparities during kidney transplant evaluation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 843–851, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myaskovsky L, Switzer GE, Crowley-Matoka M, Unruh M, DiMartini AF, Dew MA: Psychosocial factors associated with ethnic differences in transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 12: 182–187, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krieger N: Discrimination and health. In: Social Epidemiology, edited by Berkman L, Kawachi I, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2000, pp 36–75 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paradies Y: A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Int J Epidemiol 35: 888–901, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holley JL, McCauley C, Doherty B, Stackiewicz L, Johnson JP: Patients’ views in the choice of renal transplant. Kidney Int 49: 494–498, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klassen AC, Hall AG, Saksvig B, Curbow B, Klassen DK: Relationship between patients’ perceptions of disadvantage and discrimination and listing for kidney transplantation. Am J Public Health 92: 811–817, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boulware LE, Ephraim PL, Ameling J, Lewis-Boyer L, Rabb H, Greer RC, Crews DC, Jaar BG, Auguste P, Purnell TS, Lamprea-Monteleagre JA, Olufade T, Gimenez L, Cook C, Campbell T, Woodall A, Ramamurthi H, Davenport CA, Choudhury KR, Weir MR, Hanes DS, Wang NY, Vilme H, Powe NR: Effectiveness of informational decision aids and a live donor financial assistance program on pursuit of live kidney transplants in African American hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol 19: 107, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipford KJ, McPherson L, Hamoda R, Browne T, Gander JC, Pastan SO, Patzer RE: Dialysis facility staff perceptions of racial, gender, and age disparities in access to renal transplantation. BMC Nephrol 19: 5, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ozminkowski RJ, White AJ, Hassol A, Murphy M: Minimizing racial disparity regarding receipt of a cadaver kidney transplant. Am J Kidney Dis 30: 749–759, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waterman AD, Peipert JD, Hyland SS, McCabe MS, Schenk EA, Liu J: Modifiable patient characteristics and racial disparities in evaluation completion and living donor transplant. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 995–1002, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grubbs V, Gregorich SE, Perez-Stable EJ, Hsu CY: Health literacy and access to kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 195–200, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joshi S, Gaynor JJ, Bayers S, Guerra G, Eldefrawy A, Chediak Z, Companioni L, Sageshima J, Chen L, Kupin W, Roth D, Mattiazzi A, Burke GW 3rd, Ciancio G: Disparities among Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites in time from starting dialysis to kidney transplant waitlisting. Transplantation 95: 309–318, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siegel JT, O’Brien EK, Alvaro EM, Poulsen JA: Barriers to living donation among low-resource Hispanics. Qual Health Res 24: 1360–1367, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamoda R, McPherson L, Lipford K, Arriola KJ, Plantinga L, Gander JC, Hartmann E, Mulloy L, Zayas CF, Lee KN, Pastan SO, Patzer RE: Association of sociocultural factors with initiation of the kidney transplant evaluation process. Am J Transplant 20: 190–203, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dickinson DM, Arrington CJ, Fant G, Levine GN, Schaubel DE, Pruett TL, Roberts MS, Wolfe RA: SRTR program-specific reports on outcomes: A guide for the new reader. Am J Transplant 8: 1012–1026, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johansen KL, Zhang R, Huang Y, Patzer RE, Kutner NG: Association of race and insurance type with delayed assessment for kidney transplantation among patients initiating dialysis in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1490–1497, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kulkarni S, Ladin K, Haakinson D, Greene E, Li L, Deng Y: Association of racial disparities with access to kidney transplant after the implementation of the new kidney allocation system. JAMA Surg 154: 618–625, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freeman MA, Pleis JR, Bornemann KR, Croswell E, Dew MA, Chang CH, Switzer GE, Langone A, Mittal-Henkle A, Saha S, Ramkumar M, Adams Flohr J, Thomas CP, Myaskovsky L: Has the Department of Veterans Affairs found a way to avoid racial disparities in the evaluation process for kidney transplantation? Transplantation 101: 1191–1199, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart DE, Kucheryavaya AY, Klassen DK, Turgeon NA, Formica RN, Aeder MI: Changes in deceased donor kidney transplantation one year after KAS implementation. Am J Transplant 16: 1834–1847, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geisser S: Predictive Inference: An Introduction, New York, NY, Chapman and Hall, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuhn M, Johnson K: Applied Predictive Modeling, New York, Springer Science and Business Media, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pearce N: Classification of epidemiological study designs. Int J Epidemiol 41: 393–397, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Belle G, Fisher L, Heagerty PJ, Lumley T: Longitudinal data analysis. In: Biostatistics: A Methodology for the Health Sciences, New York, NY, John Wiley and Sons, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noordzij M, Leffondré K, van Stralen KJ, Zoccali C, Dekker FW, Jager KJ: When do we need competing risks methods for survival analysis in nephrology? Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 2670–2677, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sapir-Pichhadze R, Pintilie M, Tinckam KJ, Laupacis A, Logan AG, Beyene J, Kim SJ: Survival analysis in the presence of competing risks: The example of waitlisted kidney transplant candidates. Am J Transplant 16: 1958–1966, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX: Applied Logistic Regression, New York, NY, Wiley, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gander JC, Zhang X, Plantinga L, Paul S, Basu M, Pastan SO, Gibney E, Hartmann E, Mulloy L, Zayas C, Patzer RE: Racial disparities in preemptive referral for kidney transplantation in Georgia. Clin Transplant 32: e13380, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melanson TA, Hockenberry JM, Plantinga L, Basu M, Pastan S, Mohan S, Howard DH, Patzer RE: New kidney allocation system associated with increased rates of transplants among Black and Hispanic patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 36: 1078–1085, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Purnell TS, Luo X, Cooper LA, Massie AB, Kucirka LM, Henderson ML, Gordon EJ, Crews DC, Boulware LE, Segev DL: Association of race and ethnicity with live donor kidney transplantation in the United States from 1995 to 2014. JAMA 319: 49–61, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lenihan CR, Hurley MP, Tan JC: Comorbidities and kidney transplant evaluation in the elderly. Am J Nephrol 38: 204–211, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim HY, Choi JY, Kwon HW, Jung JH, Han M, Park SK, Kim SB, Lee SK, Kim YH, Han DJ, Shin S: Comparison of clinical outcomes between preemptive transplant and transplant after a short period of dialysis in living-donor kidney transplantation: A propensity-score-based analysis. Ann Transplant 24: 75–83, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rumsey S, Hurford DP, Cole AK: Influence of knowledge and religiousness on attitudes toward organ donation. Transplant Proc 35: 2845–2850, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oliver M, Woywodt A, Ahmed A, Saif I: Organ donation, transplantation and religion. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 437–444, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Müller HH, Englbrecht M, Wiesener MS, Titze S, Heller K, Groemer TW, Schett G, Eckardt KU, Kornhuber J, Maler JM: Depression, anxiety, resilience and coping pre and post kidney transplantation - Initial findings from the Psychiatric Impairments in Kidney Transplantation (PI-KT)-Study. PLoS One 10: e0140706, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nevins TE, Nickerson PW, Dew MA: Understanding medication nonadherence after kidney transplant. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 2290–2301, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waterman AD, Hyland SS, Goalby C, Robbins M, Dinkel K: Improving transplant education in the dialysis setting: The “Explore Transplant” Initiative. Dial Transplant 39: 236–241, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dew MA, DiMartini AF, De Vito Dabbs A, Myaskovsky L, Steel J, Unruh M, Switzer GE, Zomak R, Kormos RL, Greenhouse JB: Rates and risk factors for nonadherence to the medical regimen after adult solid organ transplantation. Transplantation 83: 858–873, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dew MA, Myaskovsky L, Switzer GE, DiMartini AF, Schulberg HC, Kormos RL: Profiles and predictors of the course of psychological distress across four years after heart transplantation. Psychol Med 35: 1215–1227, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Myaskovsky L, Dew MA, Switzer GE, McNulty ML, DiMartini AF, McCurry KR: Quality of life and coping strategies among lung transplant candidates and their family caregivers. Soc Sci Med 60: 2321–2332, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clark CR, Hicks LS, Keogh JH, Epstein AM, Ayanian JZ: Promoting access to renal transplantation: The role of social support networks in completing pre-transplant evaluations. J Gen Intern Med 23: 1187–1193, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Basu M, Petgrave-Nelson L, Smith KD, Perryman JP, Clark K, Pastan SO, Pearson TC, Larsen CP, Paul S, Patzer RE: Transplant center patient navigator and access to transplantation among high-risk population: A randomized, controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 620–627, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cabacungan AN, Ellis MJ, Sudan D, Strigo TS, Pounds I, Riley JA, Falkovic M, Alkon AN, Peskoe SB, Davenport CA, Pendergast JF, Ephraim PL, Mohottige D, Diamantidis CJ, St Clair Russell J, DePasquale N, Boulware LE: Associations of perceived information adequacy and knowledge with pursuit of live donor kidney transplants and living donor inquiries among African American transplant candidates. Clin Transplant 34: e13799, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Axelrod DA, Kynard-Amerson CS, Wojciechowski D, Jacobs M, Lentine KL, Schnitzler M, Peipert JD, Waterman AD: Cultural competency of a mobile, customized patient education tool for improving potential kidney transplant recipients’ knowledge and decision-making. Clin Transplant 31: e12944, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodrigue JR, Paek MJ, Schold JD, Pavlakis M, Mandelbrot DA: Predictors and moderators of educational interventions to increase the likelihood of potential living donors for Black patients awaiting kidney transplantation. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 4: 837–845, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodrigue JR, Kazley AS, Mandelbrot DA, Hays R, LaPointe Rudow D, Baliga P; American Society of Transplantation: Living donor kidney transplantation: Overcoming disparities in live kidney donation in the US–Recommendations from a Consensus Conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1687–1695, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Newell KA, Formica RN, Gill JS, Schold JD, Allan JS, Covington SH, Wiseman AC, Chandraker A: Integrating APOL1 gene variants into renal transplantation: Considerations arising from the American Society of Transplantation Expert Conference. Am J Transplant 17: 901–911, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kopp JB, Winkler CA: Genetic testing for APOL1 genetic variants in clinical practice: Finally starting to arrive. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 126–128, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lunsford SL, Simpson KS, Chavin KD, Mensching KJ, Miles LG, Shilling LM, Smalls GR, Baliga PK: Can family attributes explain the racial disparity in living kidney donation? Transplant Proc 39: 1376–1380, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Al Ammary F, Bowring MG, Massie AB, Yu S, Waldram MM, Garonzik-Wang J, Thomas AG, Holscher CM, Qadi MA, Henderson ML, Wiseman AC, Gralla J, Brennan DC, Segev DL, Muzaale AD: The changing landscape of live kidney donation in the United States from 2005 to 2017. Am J Transplant 19: 2614–2621, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Henderson ML, Hays R, Van Pilsum Rasmussen SE, Mandelbrot DA, Lentine KL, Maluf DG, Waldram MM, Cooper M: Living donor program crisis management plans: Current landscape and talking point recommendations. Am J Transplant 20: 546–552, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Keys DO, Jackson S, Berglund D, Matas AJ: Kidney donor outcomes ≥ 50 years after donation. Clin Transplant 33: e13657, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Steiner RW: “You can’t get there from here”: Critical obstacles to current estimates of the ESRD risks of young living kidney donors. Am J Transplant 19: 32–36, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wainright JL, Robinson AM, Wilk AR, Klassen DK, Cherikh WS, Stewart DE: Risk of ESRD in prior living kidney donors. Am J Transplant 18: 1129–1139, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.