Abstract

New treatments, new understanding, and new approaches to translational research are transforming the outlook for patients with kidney diseases. A number of new initiatives dedicated to advancing the field of nephrology—from value-based care to prize competitions—will further improve outcomes of patients with kidney disease. Because of individual nephrologists and kidney organizations in the United States, such as the American Society of Nephrology, the National Kidney Foundation, and the Renal Physicians Association, and international nephrologists and organizations, such as the International Society of Nephrology and the European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplant Association, we are beginning to gain traction to invigorate nephrology to meet the pandemic of global kidney diseases. Recognizing the timeliness of this opportunity, the American Society of Nephrology convened a Division Chief Retreat in Dallas, Texas, in June 2019 to address five key issues: (1) asserting the value of nephrology to the health system; (2) productivity and compensation; (3) financial support of faculty’s and divisions’ educational efforts; (4) faculty recruitment, retention, diversity, and inclusion; and (5) ensuring that fellowship programs prepare trainees to provide high-value nephrology care and enhance attraction of trainees to nephrology. Herein, we highlight the outcomes of these discussions and recommendations to the American Society of Nephrology.

Keywords: Work Force, Nephrology Fellowship, Medical Education, KidneyX, Physician Productivity, Diversity

Introduction

We have seen a remarkable “call to arms” by the nephrology community over the last decade in response to a declining interest in nephrology among students and residents (1–10). The robust responses have led to ambitious programs—from changes in medical education and value-based nephrology care to research and national prize competitions. Through these efforts, nascent trends reflect cautious optimism regarding application rates to the field of nephrology within the nephrology community. Such trends are critical as there is a clear need for sufficient numbers of well-trained nephrologists to properly care for the growing population of patients with CKD. Thus, the prospective job market remains bright. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that there are approximately 37,000,000 people with kidney disease, or roughly 15% of the US population (https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/publications-resources/2019-national-facts.html). The number of prevalent patients on dialysis continues to increase (United States Renal Data System), and there is a shortage of kidneys for transplantation for those patients who have kidney failure (11). We must expand our subspecialty by producing more nephrologists to provide quality care for this growing population of patients with kidney diseases.

The American Society of Nephrology (ASN) has initiated multiple programs focusing on education, research, and leadership to illuminate our specialty and augment the workforce (Table 1). Furthermore, in 2019, a series of exciting events unfolded that will transform the future of kidney care in the United States: for example, reports of several positive clinical trials of powerful new therapies that slow the progression of diabetic kidney disease (12,13). These and other new innovations in dialysis, vascular access, and transplantation will enhance our specialty and attract more interest in nephrology to help augment the workforce. In addition, July 10, 2019 marked a momentous occasion in America for patients with kidney disease and providers with the signing of the Executive Order on Advancing American Kidney Health by the US president. The executive order is intended to make sweeping changes to transform the care of patients with kidney diseases nationally by focusing on reducing the incidence of kidney diseases, enhancing access to home therapies and transplant, and raising public awareness. These programs serve as catalysts to ensure nephrology is vibrant and remains foundational over the coming years. In 2019, ASN partnered with the US Department of Health and Human Services and launched Kidney Innovation Accelerator (KidneyX) (14,15). This public-private partnership is targeted through prize competitions to catalyze discovery and spur innovation in nephrology to improve the lives of patients and cure kidney diseases. However, the success of exciting programs such as KidneyX and Advancing American Kidney Health depends upon a robust pipeline of talented young physicians and scientists in nephrology. To understand how best to take advantage of these opportunities, ASN convened a meeting in June 2019 of 45 adult and pediatric nephrology division chiefs to tackle perceived and real challenges in our subspecialty and ensure its continued evolution into a subspecialty of the future that will attract the best and brightest trainees. The following is a summary of the discussion and recommendations by the division chiefs on five topics: (1) asserting the value of nephrology to the health system; (2) productivity and compensation for this subspecialty; (3) financial support of faculty’s and divisions’ educational efforts; (4) faculty recruitment, retention, diversity, and inclusion; and (5) ensuring that fellowship programs prepare trainees to provide high-value nephrology care and enhance attraction of trainees to nephrology.

Table 1.

American Society of Nephrology enhancement programs

| Programs |

|---|

| Support recruitment into nephrology |

| Provide free ASN membership to trainees, including high school students, undergraduates, medical students, medical residents, PhD candidates, and nephrology fellows |

| Offer free registration to the ASN Annual Meeting at Kidney Week to high school students, undergraduates, medical students, medical residents, and PhD candidates |

| Oversee ASN Kidney STARS to ensure that selected medical students, residents, and graduate students have a “tailored” experience at ASN Kidney Week |

| Provide ASN Kidney TREKS to medical and PhD students |

| Use the ASN Pre-Doctoral Fellowship Award to fund PhD students to conduct original, meritorious research projects |

| Partner with medical student organizations to increase the profile of nephrology |

| Exhibit at national medical student meetings |

| Support the education of fellows in training |

| Fund nephrology fellows (including PhDs) annually via the Ben J. Lipps Research Fellowship Program |

| Conduct workforce research to support each generation of kidney health professionals through the ASN Data Analytics Program |

| Use the Karen L. Campbell, PhD, Travel Support Program for Fellows to support nephrology fellows (and PhDs) to attend the ASN Annual Meeting at Kidney Week |

| Support the William E. Mitch, III, MD, FASN, International Scholars Travel Support, which provides complimentary ASN membership to nephrology fellows in Latin America as well as travel support to nephrology fellows who are under-represented minorities |

| Provide travel support to 25 trainees to attend the annual Advances in Research Conference Early Program before ASN Kidney Week |

| Offer travel support to the Network of Minority Health Research Investigators Annual Workshop |

| Promote diversity, inclusion, and equity in nephrology |

| Provide trainees with complimentary access to JASN and CJASN |

| Encourage nephrology fellows to serve on ASN’s committees |

| Offer the Mentor-Mentee Curriculum and the Women in Nephrology–ASN Career Advancement Series |

| Dedicate an ASN Community, “Fellows Connect,” to provide a private, communal, and collaborative space for nephrology fellows |

| Partner with the Renal Fellow Network |

| Enhance the practice of nephrology |

| Use social media to raise awareness about kidney diseases, increase interest in nephrology careers, and promote the ASN enterprise |

| Host the ASN Communities, an online platform where members can network, collaborate, and discuss important issues in a members-only environment |

| Partner with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the Nephrologists Transforming Dialysis Safety project to enhance the quality of life for people with kidney failure |

| Launch KidneyX, a public-private partnership between the US Department of Health and Human Services and ASN, to accelerate innovation in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of kidney diseases |

| Partner with the Food and Drug Administration on the Kidney Health Initiative with a mission to catalyze innovation and the development of safe and effective patient-centered therapies for people living with kidney diseases |

| Promote the Diversity and Inclusion Committee |

ASN, American Society of Nephrology; STARS, students and residents; TREKS, Tutored Research and Education for Kidney Scholars; KidneyX, Kidney Innovation Accelerator.

Asserting the Value of Nephrology to the Health System

More than any other discipline, the nephrology service line is central to all health systems because it provides core medical and surgical services that are necessary for every adult and pediatric medical and surgical specialty. In the critical care setting, nephrology provides clinical support in the medical, cardiac, surgical, neurologic, and trauma intensive care units. Collaborative, collegial, thorough, thoughtful, and up-to-date nephrology support for AKI and congestive heart failure is essential, especially when intermittent dialysis, ultrafiltration, or continuous RRT is needed. Nephrology supports the health system’s growing cancer and trauma programs. Kidney complications of cancer immunotherapies have become increasingly common and have led to the genesis of a new focus within nephrology—onconephrology. Collaborations are necessary for patients with autoimmune kidney diseases and patients at high risk for obstetrical complications. High-risk surgical procedures, whether general, vascular, cancer, cardiac, or orthopedic related, often require nephrology consultation and, in some cases, dialysis for those who deteriorate postoperatively. Nephrologists are the primary care physicians for all patients with kidney failure (patients with kidney transplants and patients on dialysis), and these highly complex patients need inpatient and outpatient services. The value of nephrology services provided is high only if these services rendered are of high quality. Timely, effective, and meaningful consultation; expert advice on fluid electrolyte and acid-base disorders; and expert technical support in RRT are crucial. Sub-subspecialty clinics are being established, such as oncology nephrology, GN, and nephrolithiasis clinics. These clinics will enable critical expertise that will generate a referral base for greater consultative activity. Additional programs, such as transition start units where patients initiate long-term kidney replacement, are gaining interest among health systems (16). Transition start units are specialized dialysis programs that can care for patients with late CKD stage who are unprepared for kidney failure and “crash-land” into dialysis. This specialized unit provides more intense care than regular dialysis units, and early indicators suggest that patients benefit. Nephrologists are now creating new care models of CKD for stages 4 and 5 and kidney failure after the Executive Order on Advancing American Kidney Health (14,17). These new initiatives may offer value, and it will be necessary to develop and track metrics that demonstrate clinical and financial effectiveness.

The Merritt Hawkins report for 2019 is derived from surveys sent to 3000 hospital chief financial officers, resulting in 62 completed surveys from 92 separate hospitals (18). They reported the combined annual net inpatient/outpatient revenue through hospital admissions, procedures performed at the hospital, tests and treatments ordered, prescriptions written, etc., for various specialties and subspecialties. Nephrology was one of the few cognitive subspecialties to rank with the high revenue earners for institutions.

Physician Productivity and Compensation

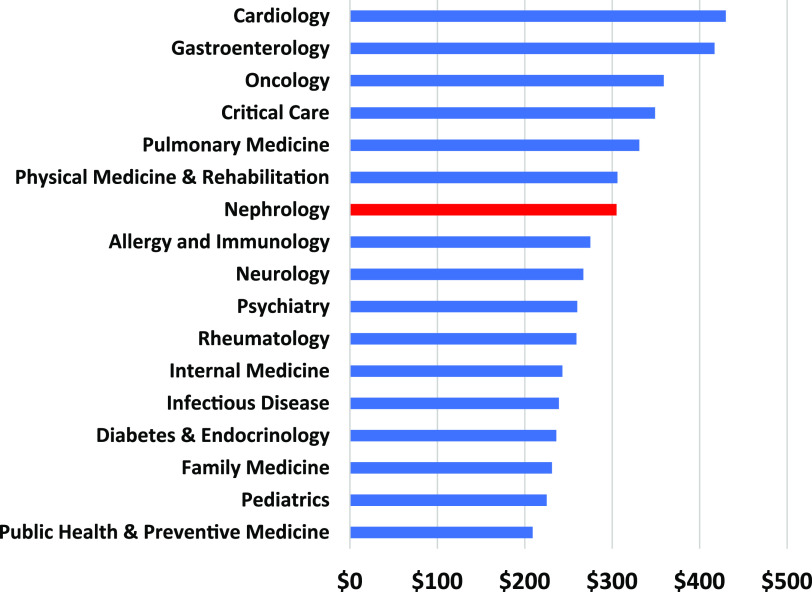

The data for average salaries for nephrologists are variable, and the average annual nephrology salary is often perceived incorrectly as low. Accurate reporting of salaries is important given the complex, time-sensitive, and exacting nature of the work, even when adjusted for regional variation. According to the Merritt Hawkins 2019 Survey, the average annual salary for a nephrologist is $272,000 and competitive compared with other cognitive specialties (18). Salaries for cognitive specialties were $241,000, $261,000, $301,000, $230,000, and $261,000 for family practice, internal medicine, neurology, pediatrics, and psychiatry, respectively. Other cognitive subspecialties in internal medicine, such as rheumatology, endocrinology, and infectious disease, were not listed but unlikely to exceed the salary of nephrologists. Recent data from Medscape indicated that the average salary for a nephrologist is $305,000, which is much higher than other cognitive specialties (19) (Figure 1). For newly graduating fellows in their first job, a recent survey by ASN Data and Johns Hopkins University indicated that median base salary was $198,000, similar to 2018 data reported by George Washington University–Health Workforce Institute. Salaries were higher for men than women. According to the Merritt Hawkins 2019 Survey, if salaries are on the basis of net revenue generated annually per physician, then the salaries could be considered commensurate with revenue generated; however, this assumes that the data are accurate. For example, it is unclear how the revenue for dialysis facility fees is attributed. For hospital systems that own their own dialysis facility, revenue generation through facility fees will be attributed to the nephrologists—but not for hospital systems using the services of external dialysis organizations. If this is the case, then the salaries on the basis of the revenue generated would appear lower than other subspecialties. A better understanding of “downstream” revenue generation is critical and must be gained given the spectrum of consultative services provided by nephrologists, the number of procedures that nephrologists oversee, and the complexity of revenue generation through dialysis services provided by external dialysis organizations. Thus, the current data suggest that the average nephrology salary is competitive. Detailed data, including the downstream revenue generated for hospital systems attributable to nephrologists, will provide an accurate basis for determining salaries in the future.

Figure 1.

Average salaries of internal medicine subspecialties and other cognitive specialties. Data depicting the average salaries of medicine subspecialties and other cognitive specialties were redrawn from Medscape Survey (19).

In the meantime, by providing timely and expert consultation, clinical practice should thrive, generating greater clinical revenue that will ultimately result in greater compensation. Salaries of private nephrologists are not substantially different than academics unless they are employed as medical directors by large dialysis organizations. However, significant differences exist in some geographic areas. Adjustments in salaries are necessary in order to recruit nephrologists to less desirable but essential geographic areas for provision of care for patients with kidney disease.

Approximately 80% of the dialysis units in the United States are owned by large dialysis organizations that are responsible for nephrology medical director compensation. Although the cost of kidney care to the health care system is high, the facility fees have become profitable for large dialysis organizations. This limits the revenues available to academic and private practices to raise salaries and make nephrology a financially rewarding specialty. New relationships are necessary (and timely with the development of new Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS] kidney care models) for nephrologists and corporate dialysis programs to become true partners for delivery of high-quality, cost-effective care with better distribution of revenue. Furthermore, if we raised academia salaries, that would set a new level for the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) benchmarks, tend to keep graduates in academic programs, and create competitive forces to induce the industry to raise compensation to attract nephrologists.

The majority of academic programs use the regional AAMC tables to set salaries around the median for rank, with some adjustment for time at rank by some programs. Market forces in some regions stimulate upward (and in some regions, downward) pressures. The spectrum of work for different types of nephrologists (e.g., transplant nephrologists, intensivists, interventionalists, hospitalists, full-time dialysis providers, or office-based nephrologists) can vary widely, and market forces influence salaries. Additional data are needed in order to determine compensation for sub-subspecialty nephrologists. Most programs that employ PhD scientists also use AAMC tables. Basic scientists are major contributors to the field of nephrology, and we should determine if their salaries are appropriate.

Relative value units (RVUs) are the dominant form of work productivity indicators used by institutions (20). About two thirds of academic programs use Vizient (formerly University HealthSystem Consortium) wRVU targets for dialysis and E/M services, which are used to determine clinical productivity and, hence, compensation. Depending on the return on wRVUs (payer mix), this may or may not be sufficient to cover the component of salary dependent on cFTE. What is clear is that the wRVU does not completely cover the actual work involved in the delivery of care. There is additional time spent outside the clinic visit (e.g., coordination of care, preauthorizations for medications, laboratory orders and reviews, and use of EMRs) that is not captured by the wRVU (20). There is little transparency in how these data are obtained, with no reporting of whether wRVUs are assisted by the presence of advanced practitioners or obtained independently. There are also several questions regarding the accuracy of the data generated by Vizient. A full analysis is needed to determine benchmarks for productivity in nephrology.

To remain competitive in attracting trainees into nephrology, we need to address physician compensation. Similar to other specialties, addressing appropriate compensation is important, particularly for US medical graduates who have considerable debt. For physician scientists, there is a financial disincentive for graduating fellows to apply for career development awards, such as National Institutes of Health K awards, because the salaries are well below their clinical peers at the instructor or assistant professor level. Moreover, not all programs make up the difference. Promising fellows completing T32 or F32 awards frequently need bridge funding and support before they are successful in getting K or initial R awards. This investment is wasted if they discontinue research efforts or are required to do more clinical work to adjust for the lack of salary.

Financial Support of Faculty’s and Divisions’ Educational Efforts

Nephrology faculty members play a significant role in medical education at academic institutions and have historically been regarded as some of the best educators in medicine. With the change in workflow and clinical demands, educational missions can suffer. To ensure nephrology’s preeminence in health care education, we must (1) provide a road map for continued teaching and educational opportunities using innovative educational methods (21–24), (2) identify funding sources for education, and (3) position ourselves to be leaders in health care education.

Teaching classically involves preclinical and clinical education of medical students. However, many faculty members also find opportunities to teach students in physician assistant, pharmacy, and graduate programs. There are a number of opportunities in inpatient and outpatient clinical settings to teach trainees and introduce them to research methods. Opportunities for resident and fellow teaching by program directors, associate program directors, and key faculty members are typically at the discretion of the division chief and the internal medicine program director (25).

Education is what attracted many nephrologists to academic medicine, and the education mission distinguishes academic from nonacademic nephrologists. Although rewarding, these are time-consuming responsibilities, funding for these efforts is limited and obscure, and protected time is minimal or nonexistent. The literature suggests that academic faculty members’ educational time is undervalued, and although systems have been implemented that more accurately define the educational effort (e.g., educational value units), there has not been widespread adoption of these strategies nationally (26). For nephrology, there is no literature on the utilization of an educational value unit system. Medical student education is often funded, but support for resident and fellow education is often lacking. Although the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) outlines necessary support for residency and fellowship activities, this can be highly variable between institutions (27). Nontraditional funding sources include college- or university-wide teaching academies and philanthropic sources.

To assert the value of nephrology faculty in the educational mission, we must do more than excel as teachers. Nephrology faculty members who are interested in education need to be recognized as experts in educational theory and educational research and, by pursuing additional training via teaching academies or advanced degrees in education, become local leaders in kidney education and the medical school curriculum. Recognition of the educational leadership and commitment by nephrologists could enhance our exposure, generate more excitement for the field, and attract more candidates to nephrology careers.

Faculty Recruitment, Retention, Diversity, and Inclusion

Work-life balance/burnout and fellowship recruitment are important challenges for nephrology faculty today. These are tightly inter-related and overlap with all of the other major discussion topics from this meeting. However, it is important to ensure that faculty recruitment (and our pipeline) and retention should not be clouded by misperceptions. Although nephrology faculty and trainees suffer from burnout, it is not specific to nephrology. In a national survey, burnout is highly prevalent among early career physicians (≤5 years in practice), residents/fellows, and medical students (28). There are a number of factors leading to burnout (29,30) that are common to all physicians and trainees. A major driver, however, is the corporatization of health care delivery with enhanced corporate-style efficiency and electronic medical record systems that contribute to physicians spending additional hours each day to document medical information. Despite the increase in workload that has spilled over into off hours, including weeknights and weekends, physicians remain bound to their commitment to the ethics that brought them into the field of medicine (31). Another major driver of burnout is the use of the wRVUs, which is often used by institutions but inaccurately reflects physician work productivity (20). It is unlikely that the rate of burnout among nephrologists is greater than in other specialties. In fact, the data from a Medscape survey indicate that nephrologists suffer less from burnout than other specialties (32). In 2019, among the 29 specialties surveyed and reported, burnout ranged from 28% to 54%; the percentage of nephrologists who experienced burnout was 32%, ranking second best with regard to burnout. This lower rate of burnout among nephrologists correlates well with other factors surveyed. Nephrologists experience the highest percentage of happy marriages (61%) and are the fifth happiest of all specialties in their personal lives.

For nephrology, work-life balance issues can be exacerbated by fellowship recruitment issues (29,30). Finding ways to attract bright young minds to our field will require careful thought and creative solutions.

Our current workforce challenges may offer an unexpected opportunity to enhance diversity in a field where the patient population tends to be heavily weighted to minority groups. Beyond racial and ethnic diversity, innovative approaches to work-life balance and compensation may attract a broader range of new nephrologists. We need to make nephrology topics more accessible and understandable by exploring different pedagogical approaches in both formal course settings and informal seminars (21–24). These innovations could reach a wider audience and attract a more diverse future faculty with distinctive strengths. Advancements in building new practice models, embracing technology, and modernizing our educational efforts would benefit from investment in current faculty who could drive these efforts. This leads to the related discussion of compensation for educational efforts. One specialty, hospital medicine, has achieved some of our goals by providing higher salaries and more favorable work hours, which support recruitment.

There are still gaps in our knowledge that prevent us from painting a complete picture in our effort to expand our workforce pipeline. We need to positively exploit the ways in which nephrology is unique from other subspecialties and use these differences to increase recruitment, retention, diversity, and inclusion. The number of women in nephrology has increased; however, like other areas of academic medicine, there are still gender gaps in leadership. ASN serves as a role model in addressing diversity, inclusion, and equity within its leadership and committees. There are still significant gaps in attracting under-represented minorities to our field, and whether the reasons are the same as in majority groups or are unique remains unclear. The Network of Minority Health Research Investigators supported by the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases establishes a network of mentor-mentee relationships among minority junior investigators. Diversity in trainees ensures a vibrant research environment. A formal assessment of our subspecialty’s level of inclusion and engagement of diverse populations may help (33,34). Specific strategies as outlined here may help diversify our field (35).

Ensuring that Fellowship Programs Prepare Trainees to Provide High-Value Nephrology Care and Enhance Attraction of Trainees to Nephrology

Longitudinal data consistently demonstrate marked discrepancies between a large number of fellowship training positions and a reduced number of applicants, a reduced number of both international and US applicants, and a large number of applicants simultaneously applying to other subspecialties, including pulmonary, cardiology, critical care, and gastroenterology. These findings raise concerns for (1) training program expectations to meet patient or work needs versus the opportunity to train and educate a trainee; (2) a reduced presence and awareness of nephrology as a field/concentration/specialization at early stages of education in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields; (3) regional differences in applicant numbers/positions available, favoring more urban centers of the country; and (4) regional differences in training expertise in specific areas of nephrology, such as genetic kidney medicine, nephrolithiasis, critical care nephrology, home dialysis, and vascular access. Taken individually or in combination, these issues contribute to a reduced number of physicians entering training in nephrology (1,2,29,30).

A risk analysis performed during the ASN retreat revealed a challenging environment for training programs and a significantly reduced eligible training and applicant pool. However, we should also understand that there are a number of factors and developments that enhance nephrology as a subspecialty. There are a significant number of highly qualified teachers and academic leaders in the field of nephrology. Many fellowship training programs are strategically moving to a less service- and more education-based approach using a variety of strategies. Two examples are incentivizing faculty members who round independently without fellows, and utilization of advanced practice providers on services where educational opportunities are reduced. This permits more focused educational opportunities and greater attending-fellow interaction. The development of nephrology-hospitalist services that include house staff and fellows may have increased earlier exposure to nephrology. Institutional support for nephrology faculty exposure to medical students, interns, and residents (general medicine rounding, morning report, internal medicine residents coming to outpatient clinics, and debates with other subspecialties as part of the conference schedule) has increased local resident applications to a few nephrology fellowship programs. Sub-subspecialization opportunities have increased interest and awareness in nephrology. Importantly, these efforts are not standardized nationally and remain local to specific programs.

Opportunities exist through earlier exposure to nephrology, for undergraduate students, medical students, and residents, early in their training where leadership in the field of nephrology is important. Importantly, creating core requirements for advanced practice providers with certification in nephrology is critical. Merging hospitalist programs with nephrology and creating ACGME-approved combined accelerated pathways with subspecialization certification could enhance interest.

There are specific recommendations that should be implemented as soon as possible. It is highly recommended that an advanced practice nurse and physician’s assistant nephrology care certification program be developed for advanced practice providers taking care of patients with underlying kidney disease. Certificate programs in areas of subspecialization in nephrology similar to what is now available for hypertension should also be developed and approved at training programs with the correct expertise. Short tracking into nephrology should be approved by the ACGME and implemented at institutions that are willing to consider this. Medical schools should revise their curricula regarding clinical nephrology and kidney physiology to increase exposure for medical students, interns, and residents. Medical students and residents who express interest in nephrology must be identified by their program directors so that mentorship opportunities with nephrology faculty can be developed.

In the future, we need to (1) optimize nephrology compensation through CMS/ASN exchange to promote a better understanding of the complexity in care of the patient with CKD or kidney failure; (2) address geographical deficiencies regarding lack of training expertise by building regional training programs in specific components of nephrology and providing small training centers appropriate support; and (3) establish an accurate estimate of the minimum number of board-certified nephrologists needed to lead the field of nephrology, understanding that with appropriately trained and certified advanced practice providers’ support, this may be substantially fewer than the number currently being trained.

As we look to the future, the growing number of patients with kidney diseases will ultimately dictate the need for expanding the number of nephrologists in the future. During this expansion, it is vital to ensure that nephrology is valued within health systems. Recommendations by the division chiefs are summarized in Table 2. We will need to ensure that nephrologists are well trained and leaders in new and creative programs, such as cardionephrology (4), onconephrology (36), critical care nephrology (9), and interventional nephrology (37,38). By doing so, primary physicians will continue to consult nephrologists for traditional nephrology clinical management problems, such as fluid and electrolytes, acid-base imbalance, or AKI. In the intensive care unit, nephrologists will continue to provide expertise in continuous RRT. We must continue to remind hospital administrators of the vital contribution that nephrology makes to the overall health system. Lastly and importantly, we must ensure that we create a profession that is distinctive and diverse with optimal work-life balance. We must push forward in support of kidney care innovation and also create new and audacious programs to invigorate current and future nephrologists and ensure the success of our specialty.

Table 2.

Recommendations

| Recommendations |

|---|

| Asserting the value of nephrology to the health system |

| (1) Obtain benchmark data on the financial return and costs for nephrology care in various health systems and practices |

| (2) Provide division chiefs with resources and a road map to address the value of nephrology to their institutions. Through division chiefs, educate hospital administrators on the true value that nephrology brings to the health system with regard to inpatient care, clinical program support, revenue, medical education, and collaborative clinical research |

| Physician productivity and compensation |

| (1) Establish national benchmarks for nephrology productivity and compensation, along with a reanalysis of the RVU system |

| (2) Optimize nephrology compensation through CMS/ASN exchange to promote a better understanding of the patient complexity in care of the patient with CKD or kidney failure |

| (3) Benchmark PhD salaries against national data |

| (4) Convert nephrology completely from a fee-for-service to a value-based model |

| Financial support of faculty’s and divisions’ educational efforts |

| (1) Develop a seminar and written information designed for division chiefs on educational financial resources and funds flow to assist nephrology leadership in division budgeting and faculty assignment |

| (2) Host an early program dedicated to advanced training in education. More intermediate and long-term solutions could be to develop an education academy that regularly meets and is highlighted at ASN Kidney Week and to develop a scholarship fund for career advancement in education |

| (3) Sponsor a national survey of education-related RVUs |

| Faculty recruitment, retention, diversity, and inclusion |

| (1) Leverage current demand outweighing supply of nephrologists to improve compensation |

| (2) Develop alternative practice models to improve work-life balance and attract a diverse pool of practitioners |

| (3) Improve and modernize our pedagogical approaches |

| Ensuring that fellowship programs prepare trainees to provide high-value nephrology care and enhance attraction of trainees to nephrology |

| (1) Develop advanced practice provider nephrology care certification programs for advanced practice providers taking care of patients with underlying kidney disease |

| (2) Create certificate programs in areas of subspecialization in nephrology (e.g., onconephrology) |

| (3) Establish ACGME-approved short tracking into nephrology |

| (4) Revise medical school and medicine residency curricula on clinical nephrology and kidney physiology, increasing exposure to clinical medical students, interns, and residents |

| (5) Increase or restructure lecture series, case presentations, reverse classroom techniques, and nephrology electives |

| (6) Require a 1- or 2-wk nephrology block during every third-year medical student’s rotation in internal medicine (39–41) |

| (7) Restructure the medicine resident elective in nephrology to include outpatient nephrology clinics, transplant clinics, home dialysis therapies, and chronic hemodialysis (42) |

| (8) Increase awareness of new sub-subspecialty fields, such as onconephrology, glomerular diseases, genetics of kidney disorders, new targeted molecular therapies especially for transplant and glomerular diseases, and new devices for ESKD |

| (9) Enhance mentorship of students and residents to provide them with a “role model “for their career path |

| (10) Use advances in social media for new ideas to teach nephrology (43) |

| (11) Address geographical deficiencies regarding lack of training expertise by building regional training programs in specific components of nephrology and providing small training centers appropriate support |

| (12) Establish an accurate estimate of the minimum number of board-certified nephrologists needed to lead the field of nephrology, understanding that with appropriately trained and certified advanced practice providers' support, this may be substantially fewer than the number currently being trained |

ASN, American Society of Nephrology; RVU, relative value unit; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Disclosures

A. Chapman reports grants and other from Reata, grants and other from Sanofi, and personal fees from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work. D.H. Ellison reports serving as a councilor for the American Society of Nephrology; reports other from the American Heart Association, the American Physiological Society, the American Society of Nephrology, Asian Pacific Congress of Hypertension, Department of Veterans Administration, Fondation LeDucq, National Defense University of Taiwan, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Ninth Oriental Congress of Nephrology, Oregon Health and Science University, University of Colorado, and UpToDate; and reports receiving grants from Department of Veterans Affairs, Fondation LeDucq, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), outside the submitted work. C.A. Gadegbeku reports serving as a site investigator for Akebia Therapeutics, as a site investigator and on the advisory committee for Bristol-Myers Squibb and Duke Clinical Research Institute, as an NIH grants coinvestigator, as a Fresenius Medical Care Episcopal Hospital Dialysis Medical Director (Philadelphia, PA), and as a councilor for the American Society of Nephrology; reports receiving grants from Akebia, Fresenius, and the NIDDK; and reports nonfinancial support from the American Society of Nephrology during the conduct of the study. P. Igarashi reports receiving travel support from American Society of Nephrology during the conduct of the study. He also reports receiving consulting fees from Otsuka America Pharmaceutical Inc.; employment from University of Minnesota and University of Minnesota Physicians; grants from National Institutes of Health; honoraria and travel support from Yale University, University of Alabama Birmingham, UT Southwestern, Harvard, and Northwestern University; royalties from Elsevier; travel support from Association of American Physicians and Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology; and equity from Crispr Therapeutics, Editas Medicine, Johnson and Johnson, Medtronic, Merck, Pfizer, Gilead, and Allergan. E. Kelepouris reports personal fees from Relypsa, personal fees from Reata Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from UpToDate, and grants from Mallinkrodt, outside the submitted work. M.D. Okusa reports receiving honoraria from UpToDate; reports honoraria and travel from Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy Taipei and India, Hong Kong Society of Nephrology, Japanese Society of Nephrology, Johns Hopkins, Mount Sinai, Northwestern, Tokyo University, University of Alabama O’Brien, University of Florida, University of Maryland, Yale O'Brien, and Yale University; reports grants from Am Pharma/Pfizer and the John Bower Foundation; reports travel support from American Physiological Society, Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, and Keystone during the conduct of the study; reports other from Adenosine Therapeutics, LLC; and reports serving on the Yale O'Brien External Advisory Committee. T.J. Plumb reports other from DaVita, Fresenius Medical Care, Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services, and Outset Medical. S.E. Quaggin reports receiving grants and other from Mannin Research; reports serving as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Genentech, Janssen, Lowy Medical Research Institute–Lowy Board of Scientific Governor's, and Roche, outside the submitted work; and reports serving as an advisor for AstraZeneca, Disease Models & Mechanisms, Journal of Clinical Investigation, Lowy Medical, Lowy Medical Research Foundation, Mannin Research, Stem Cells; as an American Diabetes Association mentor; and as the NIH Pathobiology of Kidney Disease Study Section Chair. D.J. Salant reports receiving grants from Sanofi Genzyme and Pfizer CTI; consulting and advisory board fees from Advance Medical, Chugai, Pfizer, Visterra, and University of Virginia; and honoraria from the Japanese Society of Nephrology and several US academic institutions. In addition, he has a patent Diagnostics for Membranous Nephropathy with royalties income through Boston University and royalty payments from UpToDate, Inc. for authorship of four topic cards. S. Somlo is a founder, shareholder, scientific advisory board member, and consultant for Goldfinch Bio. He has also received honoraria from Otsuka Pharmaceuticals. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgments

The following individuals participated in the Division Chief Retreat in Dallas, Texas, or served on the steering committee: John M. Arthur, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences; Michael C. Braun, Texas Children's/Baylor College of Medicine; Alfred K. Cheung, University of Utah; Michael J. Choi, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital; Ronny Coombs, American Society of Nephrology; Tarra Ischele Faulk, Lackland Air Force Base; Kevin W. Finkel, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston; Alessia Fornoni, University of Miami; David S. Goldfarb, New York Harbor Veterans Affairs Medical Center; Karen A. Griffin, Loyola University Medical Center Hines Veterans Affairs Hospital; Kenneth R. Hallows, Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California; Chou-Long Huang, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine; Tod Ibrahim, American Society of Nephrology; Talat Alp Ikizler, Vanderbilt University Medical Center; Joachim H. Ix, University of California San Diego; Craig B. Langman, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University; Thu H. Le, University of Rochester; Fangming Lin, Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons; Sandeep K. Mallipattu, Stony Brook Medicine; Dawn McCoy, American Society of Nephrology; Orson W. Moe, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center; Laura L. Mulloy, Medical College of Georgia; Chirag R. Parikh, Johns Hopkins University; Bethany S. Pellegrino, West Virginia University Section of Nephrology; Mark E. Rosenberg, University of Minnesota; Michael J. Ross, Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Montefiore Medical Center; Mark J. Sarnak, Tufts Medical Center; Tariq Shafi, University of Mississippi Medical Center; Juan Carlos Q. Velez, Ochsner Clinic Foundation; Sushrut S. Waikar, Harvard Medical School; and Myles Wolf, Duke University.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Rosner MH, Berns JS: Transforming nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 331–334, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Boer IH: Nephrology at a crossroads. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 324, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lane CA, Brown MA: Nephrology: A specialty in need of resuscitation? Kidney Int 76: 594–596, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rangaswami J, Mathew RO, McCullough PA: Resuscitation for the specialty of nephrology: Is cardionephrology the answer? Kidney Int 93: 25–26, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilbert SJ: Does the kidney biopsy portend the future of nephrology? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 681–682, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan CM, Nee R, Little DJ, Narayan R, Childs JM, Prince LK, Raghavan R, Oliver JD 3rd; Nephrology Education Research and Development Consortium (NERDC) : Survey of kidney biopsy clinical practice and training in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 718–725, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hogan JJ, Mocanu M, Berns JS: The native kidney biopsy: Update and evidence for best practice. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 354–362, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korbet SM: Nephrology and the percutaneous renal biopsy: A procedure in jeopardy of being lost along the way. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1545–1547, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Askenazi DJ, Heung M, Connor MJ Jr., Basu RK, Cerdá J, Doi K, Koyner JL, Bihorac A, Golestaneh L, Vijayan A, Okusa MD, Faubel S; American Society of Nephrology Acute Kidney Injury Advisory Group : Optimal role of the nephrologist in the intensive care unit. Blood Purif 43: 68–77, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norton JM, Ketchum CJ, Rankin TL, Star RA: Rebuilding the pipeline of investigators in nephrology research in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1285–1287, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCormick F, Held PJ, Chertow GM: The terrible toll of the kidney shortage. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 2775–2776, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, Bompoint S, Heerspink HJL, Charytan DM, Edwards R, Agarwal R, Bakris G, Bull S, Cannon CP, Capuano G, Chu PL, de Zeeuw D, Greene T, Levin A, Pollock C, Wheeler DC, Yavin Y, Zhang H, Zinman B, Meininger G, Brenner BM, Mahaffey KW; CREDENCE Trial Investigators : Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 380: 2295–2306, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heerspink HJL, Parving HH, Andress DL, Bakris G, Correa-Rotter R, Hou FF, Kitzman DW, Kohan D, Makino H, McMurray JJV, Melnick JZ, Miller MG, Pergola PE, Perkovic V, Tobe S, Yi T, Wigderson M, de Zeeuw D; SONAR Committees and Investigators : Atrasentan and renal events in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (SONAR): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 393: 1937–1947, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenberg ME, Ibrahim T: Winning the war on kidney disease: Perspective from the American Society of Nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1792–1794, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel S, Boehler A, Uehlecke N: A vision for advancing American kidney health: View from the US Department of Health and Human Services. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1789–1791, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowman B, Zheng S, Yang A, Schiller B, Morfín JA, Seek M, Lockridge RS: Improving incident ESRD care via a transitional care unit. Am J Kidney Dis 72: 278–283, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trump DJ: Executive Order 13,879: Advancing American Kidney Health, 10 July, 2019. Fed Regist 84: 33817–33819, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merritt-Hawkins: 2019 Physician inpatient/outpatient revenue survey, 2019. Available at: https://wwwmerritthawkinscom/uploadedFiles/MerrittHawkins_RevenueSurvey_2019pdf.

- 19.Medscape: Nephrology Compensation Report 2019, 2019. Available at: https://wwwmedscapecom/slideshow/2019-compensation-nephrologist-6011335#1. Accessed April 24, 2019

- 20.Rosner MH, Falk RJ: Understanding work: Moving beyond the RVU. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1053–1055, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rondon-Berrios H, Johnston JR: Applying effective teaching and learning techniques to nephrology education. Clin Kidney J 9: 755–762, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woods M, Rosenberg ME: Educational tools: Thinking outside the box. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 518–526, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leehey DJ, Daugirdas JT: Teaching renal physiology in the 21st century: Focus on acid-base physiology. Clin Kidney J 9: 330–333, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Renaud C, Siddiqui S, Jiesun W, Verstegen D: Faculty use of active learning in postgraduate nephrology education: A mixed-methods study. Kidney Med 1: 115–123, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jhaveri KD, Perazella MA: Nephrologists as educators: Clarifying roles, seizing opportunities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 176–189, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeh MM, Cahill DF: Quantifying physician teaching productivity using clinical relative value units. J Gen Intern Med 14: 617–621, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Are C, Suh M, Carpenter L, Stoddard H, Hamm V, DeVries M, Goldner W, Jarzynka K, Parker J, Simonson J, Talmon G, Vokoun C, Gold J, Mercer D, Wadman M: Model for prioritization of graduate medical education funding at a university setting—Engagement of GME committee with the clinical enterprise. Am J Surg 216: 147–154, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Boone S, Tan L, Sloan J, Shanafelt TD: Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med 89: 443–451, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts JK: Burnout in nephrology: Implications on recruitment and the workforce. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 328–330, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams AW: Addressing physician burnout: Nephrologists, how safe are we? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 325–327, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ofri D: The business of health care depends on exploiting doctors and nurses. New York Times, 2019. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/08/opinion/sunday/hospitals-doctors-nurses-burnout.html. Accessed June 8, 2019

- 32.Medscape: National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report 2019. Medscape, 2019. Available at: https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056#1. Accessed January 16, 2019

- 33.Person SD, Jordan CG, Allison JJ, Fink Ogawa LM, Castillo-Page L, Conrad S, Nivet MA, Plummer DL: Measuring diversity and inclusion in academic medicine: The diversity engagement survey. Acad Med 90: 1675–1683, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.WC4BL: WC4BL White Coats for Black Lives, 2020. Available at: https://whitecoats4blacklives.org/

- 35.Valantine H, Travis E, El-Adhami W, Vernos I, Mosqueda L, Wayne E, Kearns-Zimmerman F, Bonefont L, Visweswariah SS, Akande-Sholabi W, Polka J: A giant leap for womankind. Nat Med 25: 704–707, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cosmai L, Porta C, Perazella MA, Launay-Vacher V, Rosner MH, Jhaveri KD, Floris M, Pani A, Teuma C, Szczylik CA, Gallieni M: Opening an onconephrology clinic: Recommendations and basic requirements. Nephrol Dial Transplant 33: 1503–1510, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vachharajani TJ, Moossavi S, Salman L, Wu S, Maya ID, Yevzlin AS, Agarwal A, Abreo KD, Work J, Asif A: Successful models of interventional nephrology at academic medical centers. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 2130–2136, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roy-Chaudhury P, Yevzlin A, Bonventre JV, Agarwal A, Almehmi A, Besarab A, Dwyer A, Hentschel DM, Kraus M, Maya I, Pflederer T, Schon D, Wu S, Work J: Academic interventional nephrology: A model for training, research, and patient care. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 521–524, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel AB, Balzer MS: On becoming a nephrologist: Medical students’ ideas to enhance interest in a career in nephrology. Am J Kidney Dis 62: 450–452, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts JK, Sparks MA, Lehrich RW: Medical student attitudes toward kidney physiology and nephrology: A qualitative study. Ren Fail 38: 1683–1693, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakhoul GN, Mehdi A, Taliercio JJ, Brateanu A, Diwakar A, Daou R, Foshee CM, Sedor JR, Nally JV, O’Toole JF, Bierer SB: Residents’ perception of the nephrology specialty. Kidney Int Rep 5: 94–99, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jhaveri KD, Shah HH, Mattana J: Enhancing interest in nephrology careers during medical residency. Am J Kidney Dis 60: 350–353, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colbert GB, Topf J, Jhaveri KD, Oates T, Rheault MN, Shah S, Hiremath S, Sparks MA: The social media revolution in nephrology education. Kidney Int Rep 3: 519–529, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]