Abstract

Background:

5% of adult patients undergoing noncardiac inpatient surgery experience a major pulmonary complication. We hypothesized that the choice of neuromuscular blockade reversal (neostigmine versus sugammadex) may be associated with a lower incidence of major pulmonary complications.

Methods:

Twelve US Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group hospitals were included in a multicenter observational matched-cohort study of surgical cases between January 2014 and August 2018. Adult patients undergoing elective inpatient non-cardiac surgical procedures with general anesthesia and endotracheal intubation receiving a non-depolarizing neuromuscular blockade agent and reversal were included. Exact matching criteria included institution, sex, age, comorbidities, obesity, surgical procedure type, and neuromuscular blockade reversal agent (rocuronium versus vecuronium). Other preoperative and intraoperative factors were compared and adjusted in the case of residual imbalance. The composite primary outcome was major postoperative pulmonary complications, defined as pneumonia, respiratory failure, or other pulmonary complications (including pneumonitis; pulmonary congestion; iatrogenic pulmonary embolism, infarction, or pneumothorax). Secondary outcomes focused on the components of pneumonia and respiratory failure.

Results

Of 30,026 patients receiving sugammadex, 22,856 were matched to 22,856 patients receiving neostigmine. Out of 45,712 patients studied, 1,892 (4.1%) were diagnosed with the composite primary outcome (3.5% sugammadex vs 4.8% neostigmine). 796 (1.7%) patients had pneumonia (1.3% vs 2.2%), and 582 (1.3%) respiratory failure (0.8% vs 1.7%). In multivariable analysis, sugammadex administration was associated with a 30% reduced risk of pulmonary complications (adjusted odds ratio 0.70, 95% confidence interval 0.63 to 0.77), 47% reduced risk of pneumonia (0.53, 0.44 to 0.62), and 55% reduced risk of respiratory failure (0.45, 0.37 to 0.56), compared to neostigmine.

Conclusions

Among a generalizable cohort of adult patients undergoing inpatient surgery at US hospitals, the use of sugammadex was associated with a clinically and statistically significant lower incidence of major pulmonary complications.

Summary statement:

Among more than 45,000 patients undergoing inpatient noncardiac surgery across 12 US hospitals, the administration of sugammadex compared to neostigmine is associated with a 30% lower risk of major pulmonary complications

Introduction:

Major postoperative pulmonary complications following inpatient non-cardiac surgery are common, costly, and deadly. Approximately 5% of patients experience a major pulmonary complication, resulting in increased mortality and US $100,000 in additional costs per occurrence.1–3 With more than 300 million surgical procedures performed each year worldwide, the public health impact is significant.4,5 Decreasing pulmonary complications after surgery will be of interest to many different healthcare provider specialties, patients, and their families. While there have been advances in the areas of surgical technique, perioperative processes, and patient selection, residual neuromuscular blockade (NMB) after surgery remains a common modifiable risk factor for major postoperative pulmonary complications.6

Most adult patients undergoing general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation receive a non-depolarizing neuromuscular blockade agent (NMBA) such as rocuronium or vecuronium.1,7 The rise of minimally invasive and laparoscopic techniques has increased the use of deep NMB.8,9 Prior to extubation, standard clinical practice involves pharmacologic “reversal” of these agents using either neostigmine or sugammadex10,11. Despite this, more than 60% of patients still demonstrate objective evidence of residual NMB due to provider variation in care and patient-to-patient pharmacologic response variability.12–15 Recent multicenter European data have called into question whether the routine use of either NMB reversal agent, neostigmine or sugammadex, is associated with improvements in pulmonary complications.1 Unfortunately, wide variation in practice across countries and centers demonstrated that contrary to the preponderance of evidence, less than half of patients were reversed using either agent, and only 12% received sugammadex despite a decade of availability in Europe.1,11,12,16 In the US, single center data have demonstrated that routine reversal may improve postoperative outcomes16,17. In addition, clinical equipoise has been established - approximately half of all surgical patients requiring NMBA receive sugammadex and half receive neostigmine.18 Despite the millions of doses of neostigmine and sugammadex administered annually, robust multicenter prospective randomized or retrospective observational data regarding their relative impact on postoperative clinical outcomes beyond the recovery room are lacking.

Using a prospectively validated national registry of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative data across academic and private hospitals, we evaluated the clinical impact of sugammadex compared to neostigmine. The recent US regulatory approval of sugammadex, combined with granular intraoperative medication dosing, timing, and other surgical details not available in current literature, offered a unique experimental model to provide generalizable and reproducible real-world evidence to the many specialties that manage major pulmonary complications. We hypothesized that patients receiving sugammadex were at lower risk of postoperative pulmonary complications compared to similar patients receiving neostigmine.

METHODS

Data Sources

The Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group (MPOG)19 is a consortium of more than 50 hospitals across the United States. Patient clinical and administrative data are collected from each facility monthly. For each anesthetic case, the following data are extracted and mapped to a common lexicon allowing integration across centers: preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative laboratory values; outcome codes using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) and Current Procedural Terminology charge capture codes; clinical problem summary list ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes; intraoperative medications, fluids, vital signs, procedures, notes, and events. Standardized data validation efforts are undertaken at each center prior to data submission, including over 80 automated data quality checks and manual clinician case audit of 5 to 20 cases per month. This registry has been used previously for numerous perioperative peer-reviewed studies.20–23 The current study protocol, including primary and secondary outcomes, patient inclusions and exclusions, and statistical analysis were reviewed and approved by the MPOG publication committee a priori. Individual site Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval including a waiver of informed consent for data collection was obtained by each contributing hospital prior to submitting an anonymized dataset to the data coordinating center. Project specific IRB exemption was also obtained (HUM150403, University of Michigan Medical School IRB). This study was designed and reported using the EQUATOR-STROBE guideline.

Study Design and Setting

This retrospective observational matched cohort study includes two distinct time periods which define the matched exposure groups. Hospital policies often restrict use of sugammadex to patients with morbid obesity, significant respiratory disease, sleep apnea, coronary artery disease, cardiac arrhythmias, or major abdominal / thoracic surgery due to the higher cost of sugammadex compared to neostigmine.24 A comparison of contemporaneous patients receiving neostigmine and sugammadex would be biased via unmeasured covariates or severity of disease due to the indication bias explicitly embodied in such clinical policy and practice. Its recent US Food and Drug Administration approval in December 2015 allows the use of an experimental model to compare similar patients before and after sugammadex availability. The pre-sugammadex period (from which neostigmine treated patients were identified) includes patients from January 1, 2014 to the first documented sugammadex use, specific to each MPOG hospital. The post-sugammadex period (from which sugammadex treated patients were identified) includes patients after sugammadex was first used at each hospital until August 31, 2018. A six-month transition period after sugammadex introduction at each hospital was excluded to account for clinical practice pattern evolution with new medication availability. Patients receiving sugammadex were matched to patients receiving neostigmine using criteria described below. MPOG contributing hospitals include tertiary care university hospitals and private community hospitals throughout the US.

Participants

Adult patients aged ≥ 18 years undergoing general anesthesia with an endotracheal tube and receiving a modern steroidal NMB agent (vecuronium or rocuronium) by bolus or infusion with administration of neostigmine or sugammadex were eligible for matching. Sugammadex dosing within 10% of Food and Drug Administration approved indicated dosing range was required (1.8 – 4.4 mg/kg). Exclusion criteria included: age < 18 years; outpatient procedure; emergency, cardiac, liver or lung transplantation surgery; intubation prior to operating room arrival; American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status (ASA PS) classification 5 or 6, denoting a moribund patient or a brain-dead patient undergoing organ procurement;25 renal failure documented in ICD-9/10 codes or estimated glomerular filtration rate < 30 ml/min; sugammadex used in combination with neostigmine; sugammadex or neostigmine use with subsequent redosing of NMB agent, suggestive of temporary NMB reversal for intraoperative neuromonitoring; median intraoperative positive end-expiratory pressure > 10 cmH2O; institutional use of sugammadex for < 10% of NMB patients. For patients with multiple procedures in a thirty-day period, only the index case was included. In order to maintain a limited data set per US privacy regulations, age for all participants over 90 is censored at 90 in the MPOG dataset.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome was a composite of postoperative pulmonary complications plausibly related to residual NMB and endorsed by international consensus guidelines26,27 1) pneumonia, 2) respiratory failure, or 3) other major pulmonary complications. Consistent with previous literature,6,28 these outcomes were defined using ICD-9/10 codes (Supplemental Digital Content 1) and derived from hospital discharge diagnoses and complications data. Pulmonary complications previously used in the literature, but with unclear clinical significance or relationship to NMB (atelectasis, pulmonary edema, etc.) were not included in the primary outcome. The secondary outcomes were the individual component complications of 1) pneumonia and 2) respiratory failure.

Exposure variables

The primary exposure studied was sugammadex administration prior to extubation. The control exposure was neostigmine administration prior to extubation.

Patient matching

To minimize known institutional guideline driven bias of allowing sugammadex administration to higher risk patients or those having higher risk procedures, a matched-cohort design was implemented. Exact matching criteria were: MPOG institution ID, sex, age (matched within 5 years), ASA-PS (1, 2, 3, or 4), World Health Organization body mass index classifications; procedures at intrinsic risk of pulmonary complications (major thoracic and major abdominal, defined using primary anesthesiology Current Procedural Terminology charge capture code), specific Elixhauser comorbidities associated with increased pulmonary complication risk or indication bias (chronic pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, paralysis, liver disease, and cardiac arrhythmia)29; and NMB agent used intraoperatively (rocuronium alone vs vecuronium +/− rocuronium). Detailed definitions and clinical foundation for matching criterion are available in Supplemental Digital Content 2. Each sugammadex case was matched to exactly one neostigmine case without replacement. A database programmer used Microsoft Structured Query Language Server Management Studio 2017 to perform the exact match.

Other variables

Many other preoperative and intraoperative covariates were used to adjust for any residual confounding or indication bias: Elixhauser-defined comorbidities not used for exact matching, primary in-room provider type, general anesthesia technique, intraoperative factors associated with pulmonary complications (fluid balance in ml/kg/hr, estimated blood loss in three categories of 0–500 ml, 501 – 1000 ml, and 1000+ ml, intraoperative opioid administration in morphine equivalents / kg / hr, median ventilator driving pressure), or NMB management (intraoperative neuromuscular blockade bolus and infusion total dose in ED95 equivalents / kg / hr, last train-of-four documented within 30 minutes prior to extubation, time from last NMB dose to reversal in 15 minute increments, and time from last NMB dose to extubation in 15 minute increments) (Supplemental Digital Content 3).28

Statistical Methods

Continuous data were presented as medians and interquartile ranges due to skew; binary primary and secondary outcomes were summarized by frequencies and percentages for each matched group. Some continuous variables were transformed consistent with published clinical standards (body mass index) or clinically meaningful categories that incorporate realities of clinical documentation accuracy (estimated blood loss, time from last dose to reversal of extubation) as described in Supplemental Digital Content 2 and 3. Unadjusted differences between patients receiving sugammadex versus neostigmine were assessed using conditional logistic regression to account for the matching.

To assess the independent association between administration of sugammadex versus neostigmine reversal and the primary composite pulmonary complication, separate multivariable conditional logistic regression models were developed. Additional variables not used in matching were assessed for residual confounding using absolute standardized differences. Any covariate with a standardized difference > 0.10 was included in the multivariable analysis. In addition, surgical body region/invasiveness (16 distinct categorical variables) and NMBA (rocuronium alone, vecuronium alone, or both) were included. Adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were reported for all models. Model discrimination and calibration were assessed using standard logistic regression methods, since current statistical software is unable to calculate diagnostic measures that account for the matched design.30,31 All statistical analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.4 (SAS Institute), and hypothesis testing was two-sided.

Using an approximated formula and assuming a conservative estimate for the sample proportions and 95% confidence, to achieve a margin of error of ±1%, we would need a study sample size of approximately 9,600. For the defined study period, we expected to observe greater than 30,000 patients receiving sugammadex.

Sensitivity analyses

Several sensitivity analyses were pre-specified. First, we evaluated the potential impact of changes in coding due to the ICD-9/10 transition and restricted analyses to patients undergoing care after October 1, 2015, when ICD-10 codes were required by major US payers. Next, to assess resiliency of the observed relationships to coding error, multivariable models focused on a primary outcome of diagnosis codes that clearly denote post-surgical pulmonary complications (518.51, J95.821 or J96.00, 518.52, J95.1 or J95.2) were assessed. Third, a sensitivity analysis including the administration of intraoperative blood products (packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, or platelets) as a distinct covariate was performed. Finally, given concerns regarding severe hypersensitivity reactions associated with sugammadex administration, we identified all cases of hemodynamically significant anaphylaxis.32,33

A data analysis and statistical plan was written and filed with a private entity (MPOG publications committee) before data were accessed.

Results

Thirteen MPOG hospitals with sugammadex available on formulary as of August 31, 2018 and submitting discharge ICD-9/10 outcome data as part of their monthly contribution met inclusion criteria. Of 563,456 eligible cases, 228,946 were excluded as outpatient cases, 35,501 emergency, 143 liver or lung transplantation, 3 ASA PS 5 or 6, 18,623 renal failure, 667 combined sugammadex and neostigmine use or neuromonitoring, 283 high median PEEP, and 68,709 institutional low use of sugammadex. Of the remaining cases, 67,640 lacked intraoperative surgical start and end times, and 21,418 lacked outcomes data; these patients were similar to cases with available outcome data (Supplemental Digital Content 9). There were 119,611 patients with complete outcomes and intraoperative data who were eligible for matching; 30,026 patients received sugammadex and 89,585 received neostigmine. Prior to matching, patients receiving sugammadex demonstrated a much higher preoperative comorbidity burden and increased obesity (Table 1). After matching 22,856 sugammadex patients to 22,856 neostigmine patients, only 12 hospitals were represented; excellent preoperative and intraoperative covariate balance was achieved (Table 1 and 2); out of 80 covariates, eight demonstrated a standardized difference > 0.10 and one > 0.20 (Table 1, 2, and Supplemental Digital Content 4). Missing data rates for the studied population were small, with all intraoperative and preoperative elements other than body mass index (13.4% missing) demonstrating completeness > 98%.

Table 1:

Patient and procedure characteristics of match-eligible population and matched population.

| Before Matching | After Matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neostigmine | Sugammadex | Neostigmine | Sugammadex | Absolute Standardized Difference | |

| n=89,585 | n=30,026 | n=22,856 | n=22,856 | ||

| Age (years), median [IQR] | 57 [44, 67] | 59 [47, 69] | 59 [46, 70] | 59 [47, 68] | 0.01 |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||||

| Male | 38,972 (43.5) | 13,773 (45.9) | 10,260 (44.9) | 10,260 (44.9) | Exact match |

| Female | 50,586 (56.5) | 16,235 (54.1) | 12,596 (55.1) | 12,596 (55.1) | Exact match |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status, No. (%) | Exact match | ||||

| 1 | 4,118 (4.7) | 919 (3.1) | 658 (2.9) | 658 (2.9) | |

| 2 | 39,407 (44.8) | 11,008 (37.0) | 9,254 (40.5) | 9,254 (40.5) | |

| 3 | 41,524 (47.2) | 16,652 (55.9) | 12,598 (55.1) | 12,598 (55.1) | |

| 4 | 3,003 (3.4) | 1,204 (4.0) | 346 (1.5) | 346 (1.5) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), median [IQR] | 28.4 [24.4, 33.7] | 28.5 [24.5, 33.7] | 28.5 [24.7, 33.5] | 28.5 [24.7, 33.6] | Exact match |

| Selected Elixhauser comorbidities, No. (%) | |||||

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 9,204 (10.3) | 4,147 (13.9) | 1,910 (8.4) | 1,910 (8.4) | Exact match |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 13,140 (14.7) | 5,045 (16.8) | 3,010 (13.2) | 3,010 (13.2) | Exact match |

| Congestive heart failure | 3,300 (3.7) | 1,383 (4.6) | 382 (1.7) | 382 (1.7) | Exact match |

| Liver disease | 3,355 (3.8) | 1,350 (4.5) | 511 (2.2) | 511 (2.2) | Exact match |

| Paralysis | 1,058 (1.2) | 506 (1.7) | 129 (0.6) | 129 (0.6) | Exact match |

| Coagulopathy | 2,198 (2.5) | 1,071 (3.6) | 560 (2.5) | 635 (2.8) | 0.01 |

| Depression | 10,514 (11.7) | 3,360 (11.2) | 2,772 (12.1) | 2,343 (10.3) | 0.06 |

| Diabetes (uncomplicated) | 9,810 (11.0) | 4,043 (13.5) | 2,883 (12.6) | 2,963 (13.0) | 0.00 |

| Fluid/electrolyte disorders | 7,555 (8.4) | 2,858 (9.5) | 1,875 (8.2) | 1,677 (7.3) | 0.03 |

| Hypertension (complicated) | 313 (0.4) | 1,039 (3.5) | 81 (0.4) | 375 (1.6) | 0.10 |

| Hypertension (uncomplicated) | 35,617 (39.8) | 13,160 (43.8) | 9,987 (43.7) | 9,966 (43.6) | 0.02 |

| Hypothyroidism | 8,460 (9.4) | 3,106 (10.3) | 2,417 (10.6) | 2,317 (10.1) | 0.02 |

| Metastatic cancer | 7,053 (7.9) | 2,872 (9.6) | 2,065 (9.0) | 2,136 (9.3) | 0.00 |

| Other neurological disorders | 3,970 (4.4) | 1,598 (5.3) | 1,043 (4.6) | 1,058 (4.6) | 0.00 |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 4,552 (5.1) | 1,814 (6.0) | 1,199 (5.2) | 1,105 (4.8) | 0.02 |

| Collagen vascular diseases | 2,237 (2.5) | 849 (2.8) | 625 (2.7) | 602 (2.6) | 0.01 |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 17,683 (19.7) | 8,453 (28.2) | 4,885 (21.4) | 6,519 (28.5) | 0.11 |

| Valvular disease | 3,219 (3.6) | 1,262 (4.2) | 714 (3.1) | 681 (3.0) | 0.01 |

| Weight loss | 4,210 (4.7) | 1,599 (5.3) | 933 (4.1) | 897 (3.9) | 0.01 |

| Procedure Type, No. (%) | |||||

| Head/neck major | 9,352 (10.4) | 3,403 (11.4) | 2,644 (11.6) | 2,721 (11.9) | 0.01 |

| Head/neck minor | 3,332 (3.7) | 1,084 (3.6) | 833 (3.6) | 879 (3.8) | 0.01 |

| Thoracic major | 6,989 (7.8) | 2,628 (8.8) | 1,391 (6.1) | 1,391 (6.1) | Exact match |

| Thoracic minor | 3,307 (3.7) | 1,026 (3.4) | 754 (3.3) | 766 (3.4) | 0.00 |

| Spine/spinal cord major | 8,578 (9.6) | 2,586 (8.7) | 2,326 (10.2) | 2,145 (9.4) | 0.03 |

| Upper and lower abdomen major | 29,092 (32.5) | 9,105 (30.6) | 6,937 (30.4) | 6,937 (30.4) | Exact match |

| Urologic/gynecologic/pelvis major | 9,437 (10.5) | 3,581 (12.0) | 2,665 (11.7) | 3,114 (13.6) | 0.06 |

| Hip/leg/foot/shoulder/arm/hand major | 7,757 (8.7) | 2,517 (8.5) | 2,228 (9.7) | 1,938 (8.5) | 0.04 |

| Hip/leg/foot/shoulder/arm/hand minor | 5,365 (6.0) | 1,473 (4.9) | 1,425 (6.2) | 1,169 (5.1) | 0.05 |

| Other | 6,359 (7.1) | 2,395 (8.0) | 1,653 (7.2) | 1,796 (7.9) | 0.02 |

Additional definitions and details available for all study variables in Supplemental Digital Content 2 and Supplemental Digital Content 3.

Selected Elixhauser comorbidities pertinent to pulmonary complications or treatment bias related to sugammadex versus neostigmine are listed here. All Elixhauser comorbidity data (after matching) are presented in Supplemental Digital Content 4. Comorbidity definitions are using Elixhauser groupings of International Classification of Diseases 9th or 10th edition as described by Quan and colleagues in Quan H, Sundarajan V, Halfon P, et al Coding algorithms for defining Comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM administrative data. Med Care. 2005 Nov; 43 (11): 1130–9

Table 2:

Intraoperative characteristics of patients receiving sugammadex and neostigmine in matched analytic cohort

| Neostigmine | Sugammadex | Absolute Standardized Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=22,856 | n=22,856 | ||

| Procedure duration, hours [IQR] | 3.4 [2.5, 4.7] | 3.4 [2.4, 4.7] | 0.03 |

| Estimated blood loss No. (%) | |||

| 0–500 | 21,302 (93.2) | 21,548 (94.3) | 0.05 |

| 501–1000 | 1,114 (4.9) | 951 (4.2) | |

| >1000 | 440 (1.9) | 357 (1.6) | |

| Fluid balance, mL/kg/hr [IQR] | 3.7 [1.9, 5.8] | 3.3 [1.7, 5.1] | 0.07 |

| Intraoperative opioid administered (in morphine equivalents), mg/kg/hr [IQR] | 0.3 [0.2, 0.4] | 0.3 [0.2, 0.4] | 0.17 |

| Median ventilator driving pressure (cm H2O) [IQR] | 15 [12.0, 19.0] | 15 [12.0, 19.0] | 0.08 |

| Neuromuscular blockade agent No. (%) | |||

| Vecuronium only | 5,054 (22.1) | 5,035 (22.0) | 0.01 |

| Rocuronium only | 17,553 (76.8) | 17,553 (76.8) | |

| Vecuronium and rocuronium | 249 (1.1) | 268 (1.2) | |

| Last train-of-four documented within 30 minutes of extubation No. (%) | 0.32 | ||

| Not documented | 9695 (42.4) | 6641 (29.1) | |

| 0 or 1 twitches | 377 (1.6) | 939 (4.1) | |

| 2 twitches | 503 (2.2) | 991 (4.3) | |

| 3 or 4 twitches | 12281 (53.7) | 14285 (62.5) | |

| General Anesthesia Technique | 0.11 | ||

| Volatile, with or without propofol infusion or inhaled nitrous oxide | 22,275 (97.5) | 21,869 (95.7) | |

| Propofol infusion, without inhaled volatile or nitrous oxide | 483 (2.1) | 894 (3.9) | |

| Nitrous oxide, with propofol infusion | 98 (0.4) | 93 (0.4) | |

| Primary In-Room Anesthesiology Provider | 0.06 | ||

| Faculty only | 918 (4.0) | 1,085 (4.7) | |

| Resident/fellow | 10,886 (47.6) | 10,284 (45.0) | |

| Certified registered nurse anesthetist | 11,047 (48.3) | 11,479 (50.2) | |

| Time from last NMB dose to reversal (15 minute interval) [IQR] | 4.4 [2.9, 6.7] | 4 [2.7, 6.0] | 0.14 |

| Time from reversal to Extubation (5 minute interval) [IQR] | 3 [1.8, 4.6] | 2.4 [1.4, 3.8] | 0.06 |

| Time from last NMB to extubation (15 minute interval) [IQR] | 5.6 [3.9, 8.1] | 5 [3.5, 7.3] | 0.15 |

| Intraoperative neuromuscular blockade administered (ED 95/ kg/hour) [IQR] | 1.2 [0.9, 1.6] | 1.4 [1.1,1.8] | 0.20 |

Additional variable definitions and details available in Supplemental Digital Content 2 and 3

IQR = interquartile range; NMB = neuromuscular blockade

“Intraoperative neuromuscular blockade administered” was calculated by totaling bolus and infusion administrations for vecuronium and rocuronium separately. The amount of each agent was divided by its ED 95 (0.05 mg/kg for vecuronium, 0.3 mg/kg for rocuronium) and then adjusted for weight in kg and anesthesia duration.

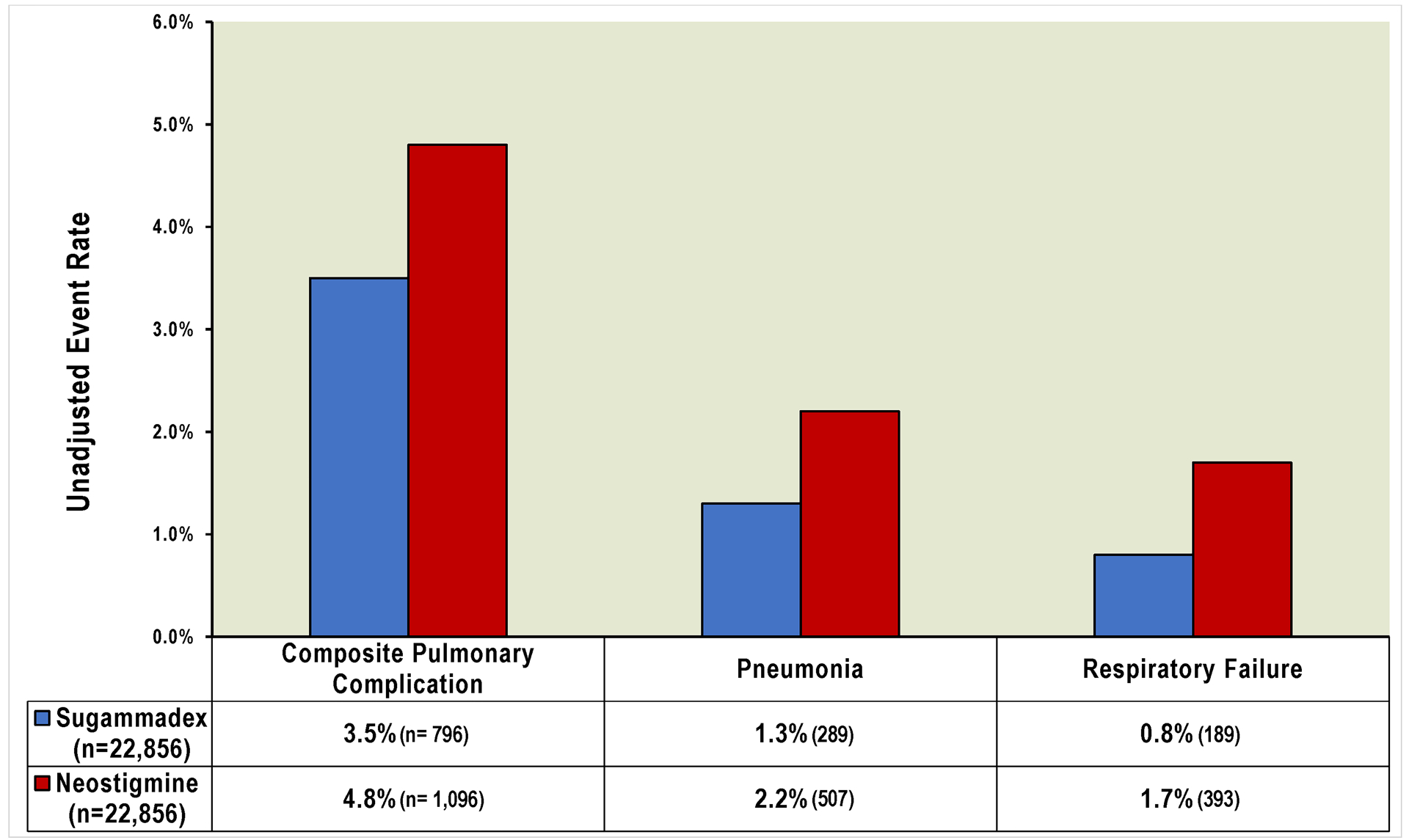

Among the 45,712 patients in the matched analytic dataset, the median age was 58 years, median body mass index was 28.5 kg/m2; 55% were female, and 55% were ASA PS 3. The most common surgical procedures were major abdominal (30.4%), major urologic / gynecologic (13.6%), and major head and neck (11.9%). 1,892 patients (4.1%) experienced the composite primary outcome (3.5% sugammadex vs 4.8% neostigmine), 796 (1.7%) pneumonia (1.3% vs 2.2%), and 582 (1.3%) respiratory failure (0.8% vs 1.7%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Major pulmonary complication event rates (unadjusted) in matched cohort of patients undergoing noncardiac inpatient surgery

Patients receiving sugammadex were matched to patients receiving neostigmine across twelve hospitals using exact match criteria of institution, sex, age, comorbidities, obesity, surgical procedure type, and neuromuscular blockade agent. The composite pulmonary complication primary outcome included pneumonia, respiratory failure, and other major complications.

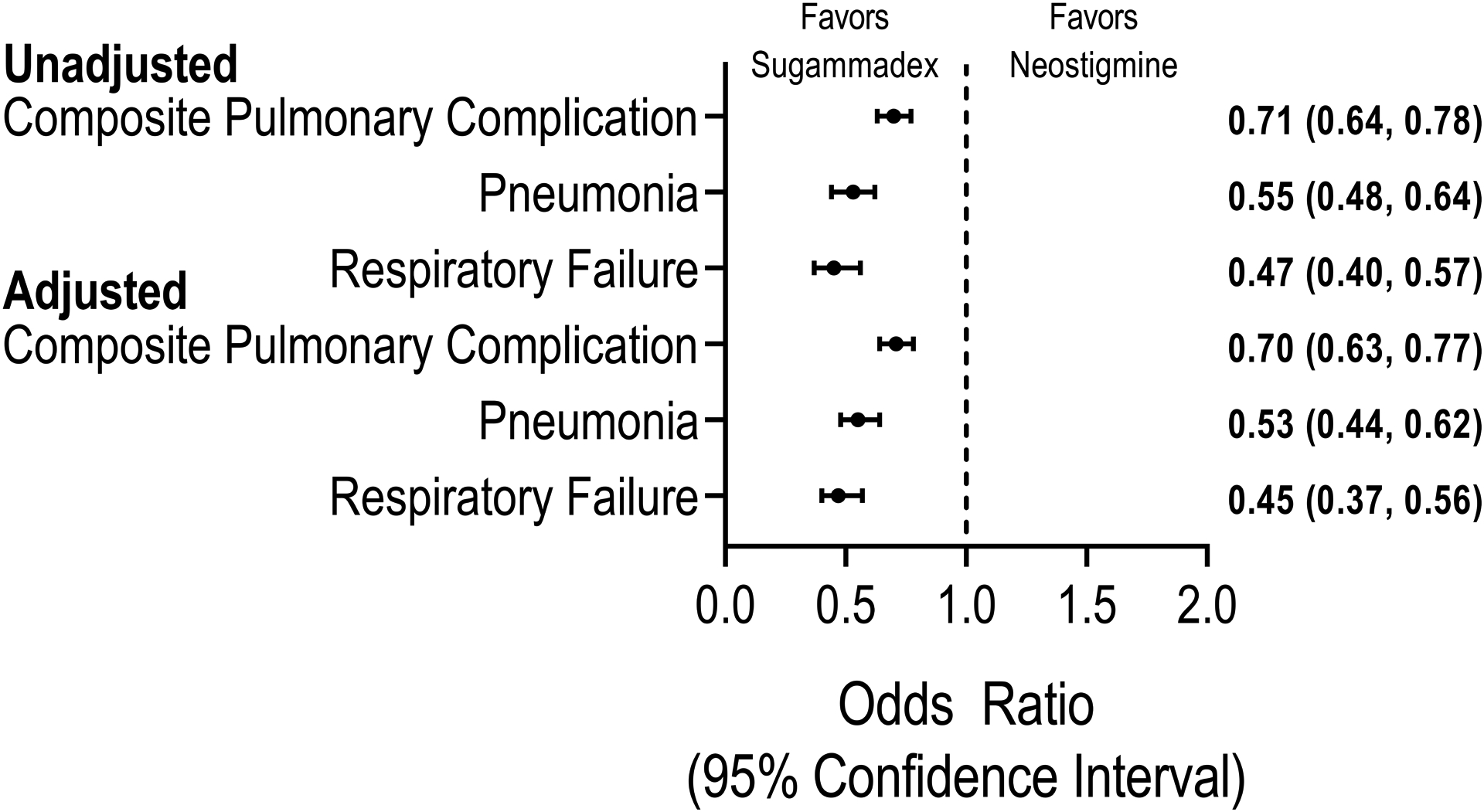

In multivariable conditional logistic regression analyses incorporating all covariates with an absolute standard difference > 0.10 and each surgical procedure category, sugammadex administration was associated with a 30% reduced risk of pulmonary complications (adjusted OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.63, 0.77), 47% for pneumonia (0.53 (0.44, 0.62)), and 55% (0.45 (0.37, 0.56)) for respiratory failure (Figure 2; Supplemental Digital Content 5, 6, 7 for full model results and diagnostics). Pre-specified sensitivity analyses demonstrated similar effect sizes and statistical significance: (Supplemental Digital Content 8) patients after the ICD-10 transition (primary outcome adjusted OR 0.79 [95% CI 0.66 to 0.94]); ICD-9/10 outcome codes specific to post-surgical pulmonary complications (adjusted OR 0.68 [0.52 to 0.88]); adjustment for blood product administration (adjusted OR 0.71 [0.63 to 0.78]). No patients demonstrated hemodynamically significant anaphylaxis after administration of neostigmine or sugammadex.

Figure 2:

Unadjusted and adjusted association of sugammadex versus neostigmine administration with major pulmonary complications after inpatient noncardiac surgery

In a matched cohort of patients, the association of sugammadex with composite and individual major pulmonary complications was assessed using multivariable conditional logistic regression adjusting for covariates with residual absolute standardized difference > 0.10. The composite pulmonary complication primary outcome included pneumonia, respiratory failure, and other major complications.

Several post-hoc sensitivity analyses were also performed. First, to evaluate whether any specific hospital with outlier observations may be driving the overall results, we compared each center’s unadjusted primary outcome rate between matched patients administered sugammadex and neostigmine; six out of seven hospital with matched patient volume of 1000 or more patients had point estimates < 1.0, consistent with the primary analysis, while one had a point estimate of 1.02 (Supplemental Digital Content 10). As expected given the range of academic and private hospitals included in the analysis, 10-fold variation in clinical volume and 8-fold variation in recorded pulmonary complications was noted. Next, to minimize the potential impact of temporal changes in practice, we restricted the matched cohort analysis to sugammadex-neostigmine patient pairs undergoing surgery within 24 months of each other and observed a consistent primary outcome adjusted OR 0.76 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.92). Finally, to identify the resiliency of the observations to unmeasured confounders, we calculated the E-Value associated with the adjusted odds ratios of the primary analysis,34 demonstrating unmeasured confounders with effect sizes of 2.21, 3.26, or 3.77 would be required to explain the observed association between sugammadex administration and composite pulmonary complications, pneumonia, and respiratory failure, respectively.

Discussion

In a retrospective matched-cohort analysis across 12 US hospitals for 45,712 adult patients undergoing inpatient surgery requiring general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation, administration of sugammadex to restore neuromuscular function prior to operative extubation was associated with a 30–50% lower risk of pulmonary complications including pneumonia and respiratory failure. The matching algorithm resulted in excellent balance across the studied groups in patient, procedure, and intraoperative care factors (Table 1). The findings are resilient to several sensitivity analyses and are generalizable given the number of centers and variety of surgical cases included. Our studied outcomes, pneumonia and respiratory failure, represent reliable and impactful pulmonary complications, unlike less severe yet more frequent events such as pulmonary edema, atelectasis, and need for postoperative supplemental oxygen.26,27

These data provide evidence that known effects of sugammadex on intermediate biological outcomes such as neuromuscular recovery may extend to clinically related downstream postoperative outcomes such as pneumonia and respiratory failure. A recent Cochrane review of 41 randomized trials spanning 4,206 patients showed improvements in bradycardia, postoperative nausea and vomiting, and postoperative residual neuromuscular blockade in patients receiving sugammadex compared to neostigmine.11 However, no data on outcomes beyond the recovery room were available. Improved muscle tone affects diaphragmatic, upper airway and chest wall strength, potentially improving a patient’s ability to cough, clear secretions, decrease alveolar collapse enabling pneumonia, and prevent microaspiration.16,35 The primary outcome is directly related to neuromuscular tone. We observed a 30% reduction in the overall composite primary outcome, driven largely by reductions in the component outcomes of pneumonia (47% relative reduction, absolute reduction from 2.2% to 1.3%) and respiratory failure (55% relative reduction, absolute reduction from 1.7% to 0.8% (Figures 1 and 2), similar to a recently published single-center before-after analysis.17 We did not observe a reduction in the “other pulmonary complication” component of the primary outcome (adjusted odds ratio 0.99, 0.85,1.15), which included ICD codes for conditions less likely related to NMB, such as pneumonitis, pulmonary congestion, iatrogenic pulmonary embolism and infarction, iatrogenic pneumothorax, and other pulmonary complications. (Supplemental Digital Content 1)

Our observed improvement in pulmonary outcomes should be placed in the context of recent observations from POPULAR, a prospective observational study across 28 European countries which analyzed data for 22,803 patients receiving general anesthesia and did not observe an association between neuromuscular blockade reversal and improved outcomes.1 First, POPULAR’s most common “pulmonary complication” was “mild respiratory failure”, defined as the need for supplementary oxygen to maintain SpO2 ≥ 90% postoperatively, occurring in 5.2% of patients. The clinical impact and reproducibility of this definition is questionable given provider variations in the decision to administer supplemental oxygen. Our primary outcome which focuses on reintubation and pneumonia is more reliable and clinically meaningful. Next, contrary to evidence-based guidelines, less than half of the patients in POPULAR study were actually reversed with any agent. Less than 2,000 patients received sugammadex and only 10% of patients had complete data needed for appropriate patient matching and comparison across therapeutic groups. Our data across 12 hospitals included more than 20,000 patients receiving sugammadex, allowing for a more precise matching of patient and surgical factors across treatment choices. More importantly, our data included detailed intraoperative pharmacologic, physiologic, and hemodynamic information necessary for meaningful indication bias adjustment.

Limitations

Despite these strengths, the STRONGER study does include several limitations. First, the marked reduction in pulmonary complications associated with sugammadex may be due to temporal factors. Although the four-year study period did not include any other major changes in pulmonary care clinical protocols, natural improvement in clinical practice may account for some of the reduction in complications. However, given the median time difference between neostigmine and sugammadex cases of only 29 months, it is unlikely that a 50% reduction in pneumonia is explained entirely by other improvements in practice over time. Table 2 demonstrates the measured intraoperative processes of care were statistically indistinguishable between the two groups, although other unmeasured covariates may or may not be balanced. The post-hoc sensitivity analysis focused on matched patients within 24 months provides additional support. In addition, discharge coding errors or misclassification may have also contributed to the observed change in outcome. However, the sensitivity analysis focused on patients after October 2015, when the ICD-10 transition occurred, and the sensitivity analysis using only explicit post-surgical complication ICD codes both revealed similar effect sizes and statistically significant results as seen in the primary analysis. There are inherent limitations due to the observational nature of the study, which may warrant a prospective, pragmatic controlled trial. Residual confounding and selection bias are likely present; however, given the indication bias for higher-risk patients to receive sugammadex, this issue would bias toward the null hypothesis. E-value analysis demonstrated that an extremely strong unmeasured confounder with an effect size > 3 would be required to refute the improved outcomes associated with sugammadex use. Next, due to missing outcome data, approximately 14% of patients meeting clinical inclusion criteria were excluded. These patients were demographically and clinically similar to the studied patients. Next, the comorbidity definitions are based upon discharge diagnoses codes and algorithms which may not adequately address specific pulmonary diseases or severity of disease (such as home oxygen use, restrictive lung disease). Finally, the study population excluded emergency surgery, patients receiving sugammadex outside normal dosing guidelines, outpatients, and centers not contributing outcome data, leaving unclear the effect of sugammadex in these populations.

Conclusions

Given the tens of millions of patients undergoing general endotracheal anesthesia each year worldwide, these data inform efforts to decrease pulmonary complications after inpatient surgery and the choice between neostigmine and sugammadex use. While sugammadex provides rapid and effective restoration of neuromuscular tone without systemic anticholinergic activity, neostigmine currently remains the mainstay of practice worldwide given decades of experience and the higher price of sugammadex.1,24 The current analysis provides generalizable, real-world observations given the multicenter data collection methodology during routine care, and should encourage clinicians and policymakers to reevaluate current practice patterns. The observed use of sugammadex in patients with a range of underlying risks and depths of neuromuscular blockade reflect an evolving pattern of use which may be discordant with some institutional policies intending to strictly limit its use. Future research should evaluate the reproducibility of these findings in specific patient subgroups, consider prospective effectiveness controlled trials, and establish the cost/benefit ratio of the different reversal strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement:

The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable contributions to protocol and final manuscript review by the Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group (MPOG) Perioperative Clinical Research Committee, including Michael Aziz, William Hightower, Robert Craft, Zachary A Turnbull, and Adit A Ginde.

Funding statement: Funding was provided by departmental and institutional resources at each contributing site. In addition, partial funding to support underlying electronic health record data collection into the MPOG registry was provided by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan / Blue Care Network (BCBSM/BCN) as part of the BCBSM/BCN Value Partnerships program. Although BCBSM/BCN and MPOG work collaboratively, the opinions, beliefs and viewpoints expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs and viewpoints of BCBS/BCN or any of its employees.

Partial funding for data extraction and analysis was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA to the University of Michigan

The work of co-authors Patrick McCormick, Karsten Bartels, Michael Mathis, and Douglas Colquhoun was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health.

The study protocol and statistical analysis plan were reviewed and approved a priori by the Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group publications committee, an academic entity independent of funding sources and free from industry and funder involvement. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflict of interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf. LDB is an employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA, which manufactures and distributes sugammadex. SK, MTV, TZD, AMS, and LS declare indirect support from Merck & Co., Inc to their organization (University of Michigan) to support aspects of the submitted work. AB and RBS declare indirect support from Merck & Co., Inc to their organization (Yale University) for other research. RGS and LS declare receiving consulting fees from Merck & Co., Inc.

Other relationships unrelated to the current work include: SK, NJS declare indirect support from Apple, Inc to their organization (University of Michigan). TZD declares serving on an expert panel for Fresenius Kabi. PJM is a board member of the Society for Technology in Anesthesia and his spouse owns stock in Johnson & Johnson. RBS owns stock in Johnson & Johnson. LS declares consulting fees or serving on an expert panel for Medtronic (Covidien) and the The37Company. RGS declares serving on an expert panel for Mallinckrodt LLC and consulting fees from Heron Therapeutics, Inc.

Footnotes

Prior presentations: A subset of this data was presented at the European Society of Anesthesiology Meeting on June 4, 2019 in Vienna, Austria

Contributor Information

Sachin Kheterpal, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Michelle T Vaughn, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Timur Z Dubovoy, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Nirav J Shah, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Lori D Bash, Center for Observational and Real World Evidence, Merck & Co. Inc, Kenilworth, NJ USA.

Douglas A Colquhoun, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Amy M Shanks, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Michael R Mathis, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Roy G Soto, Department of Anesthesiology, Beaumont Health, Royal Oak, Michigan, USA.

Amit Bardia, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Karsten Bartels, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Colorado, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Patrick J McCormick, Department of Anesthesiology & Critical Care Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, USA.

Robert B Schonberger, Department of Anesthesiology, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Leif Saager, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA (now at University Medical Center Gottingen, Lower Saxony, Germany).

References

- 1.Kirmeier E, Eriksson LI, Lewald H, Jonsson Fagerlund M, Hoeft A, Hollmann M, Meistelman C, Hunter JM, Ulm K, Blobner M, POPULAR Contributors: Post-anaesthesia pulmonary complications after use of muscle relaxants (POPULAR): a multicentre, prospective observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2019; 7:129–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dimick JB, Chen SL, Taheri PA, Henderson WG, Khuri SF, Campbell DA Jr: Hospital costs associated with surgical complications: a report from the private-sector National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg 2004; 199:531–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freundlich RE, Maile MD, Sferra JJ, Jewell ES, Kheterpal S, Engoren M: Complications Associated With Mortality in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Database. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2018; 127:55–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meara JG, Leather AJM, Hagander L, Alkire BC, Alonso N, Ameh EA, Bickler SW, Conteh L, Dare AJ, Davies J, Mérisier ED, El-Halabi S, Farmer PE, Gawande A, Gillies R, Greenberg SLM, Grimes CE, Gruen RL, Ismail EA, Kamara TB, Lavy C, Lundeg G, Mkandawire NC, Raykar NP, Riesel JN, Rodas E, Rose J, Roy N, Shrime MG, Sullivan R, Verguet S; Watters D; Weiser TG; Wilson IH; Yamey G; Yip W: Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Int J Obstet Anesth 2016; 25:75–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nepogodiev D, Martin J, Biccard B, Makupe A, Bhangu A: Global burden of postoperative death. Lancet 2019; 393:401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grosse-Sundrup M, Henneman JP, Sandberg WS, Bateman BT, Uribe JV, Nguyen NT, Ehrenfeld JM, Martinez EA, Kurth T, Eikermann M: Intermediate acting non-depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents and risk of postoperative respiratory complications: prospective propensity score matched cohort study. BMJ 2012; 345:e6329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lundstrøm LH, Duez CH, Nørskov AK, Rosenstock CV, Thomsen JL, Møller AM, Strande S, Wetterslev J: Avoidance versus use of neuromuscular blocking agents for improving conditions during tracheal intubation or direct laryngoscopy in adults and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 5:CD009237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy GS: Neuromuscular Monitoring in the Perioperative Period. Anesth Analg 2018; 126:464–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruintjes MH, van Helden EV, Braat AE, Dahan A, Scheffer GJ, van Laarhoven CJ, Warlé MC: Deep neuromuscular block to optimize surgical space conditions during laparoscopic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 2017; 118:834–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy G, De Boer HD, Miller RD: Miller’s Anesthesia, Ninth Edition; Chapter 28: Reversal (Antagonism) of Neuromuscular Blockade. Edited by Gropper MA, Miller RD, Cohen NH, Eriksson LI, Fleisher LA, Leslie K, Wiener-Kronish JP. Elsevier Saunders, 2019, pages 832–864 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hristovska A-M, Duch P, Allingstrup M, Afshari A: Efficacy and safety of sugammadex versus neostigmine in reversing neuromuscular blockade in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 8:CD012763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy GS, Szokol JW, Avram MJ, Greenberg SB, Shear TD, Deshur MA, Benson J, Newmark RL, Maher CE: Neostigmine Administration after Spontaneous Recovery to a Train-of-Four Ratio of 0.9 to 1.0: A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Effect on Neuromuscular and Clinical Recovery. Anesthesiology 2018; 128:27–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy GS, Szokol JW, Avram MJ, Greenberg SB, Shear T, Vender JS, Gray J, Landry E: Postoperative residual neuromuscular blockade is associated with impaired clinical recovery. Anesth Analg 2013; 117:133–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fortier L-P, McKeen D, Turner K, de Médicis É, Warriner B, Jones PM, Chaput A, Pouliot J-F, Galarneau A: The RECITE Study: A Canadian Prospective, Multicenter Study of the Incidence and Severity of Residual Neuromuscular Blockade. Anesth Analg 2015; 121:366–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saager L, Maiese EM, Bash LD, Meyer TA, Minkowitz H, Groudine S, Philip BK, Tanaka P, Gan TJ, Rodriguez-Blanco Y, Soto R, Heisel O: Incidence, risk factors, and consequences of residual neuromuscular block in the United States: The prospective, observational, multicenter RECITE-US study. J Clin Anesth 2019; 55:33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bulka CM, Terekhov MA, Martin BJ, Dmochowski RR, Hayes RM, Ehrenfeld JM: Nondepolarizing Neuromuscular Blocking Agents, Reversal, and Risk of Postoperative Pneumonia. Anesthesiology 2016; 125:647–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krause M, McWilliams SK, Bullard KJ, Mayes LM, Jameson LC, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Fernandez-Bustamante A, Bartels K: Neostigmine Versus Sugammadex for Reversal of Neuromuscular Blockade and Effects on Reintubation for Respiratory Failure or Newly Initiated Noninvasive Ventilation: An Interrupted Time Series Design. Anesth Analg 2019. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004505 (Published ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Timur D, Kheterpal S, Shah N, Saager L, Housey S: E163. Real World Utilization Patterns of Perioperative Neuromuscular Blockade Reversal in the United States: A Retrospective Observational Study from the Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group, International Anesthesia Research Society Abstracts Poster Session; Montreal, Canada, May 20, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freundlich RE, Kheterpal S: Perioperative effectiveness research using large databases. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2011; 25:489–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berman MF, Iyer N, Freudzon L, Wang S, Freundlich RE, Housey M, Kheterpal S, Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group (MPOG) Perioperative Clinical Research Committee: Alarm Limits for Intraoperative Drug Infusions: A Report From the Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group. Anesth Analg 2017; 125:1203–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kheterpal S, Healy D, Aziz MF, Shanks AM, Freundlich RE, Linton F, Martin LD, Linton J, Epps JL, Fernandez-Bustamante A, Others: Incidence, predictors, and outcome of difficult mask ventilation combined with difficult laryngoscopy: A report from the multicenter perioperative outcomes group. Anesthesiology 2013; 119:1360–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun E, Mello MM, Rishel CA, Vaughn MT, Kheterpal S, Saager L, Fleisher LA, Damrose EJ, Kadry B, Jena AB, for the Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group (MPOG): Association of Overlapping Surgery With Perioperative Outcomes. JAMA 2019; 321:762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee LO, Bateman BT, Kheterpal S, Klumpner TT, Housey M, Aziz MF, Hand KW, MacEachern M, Goodier CG, Bernstein J, Bauer ME: Risk of Epidural Hematoma after Neuraxial Techniques in Thrombocytopenic ParturientsA Report from the Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group. Anesthesiology 2017; 126:1053–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Reilly-Shah VN, Wolf FA, Jabaley CS, Lynde GC: Using a worldwide in-app survey to explore sugammadex usage patterns: a prospective observational study. Br J Anaesth 2017; 119:333–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurwitz EE, Simon M, Vinta SR, Zehm CF, Shabot SM, Minhajuddin A, Abouleish AE: Adding Examples to the ASA-Physical Status Classification Improves Correct Assignment to Patients. Anesthesiology 2017; 126:614–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jammer I, Wickboldt N, Sander M, Smith A, Schultz MJ, Pelosi P, Leva B, Rhodes A, Hoeft A, Walder B, Chew MS, Pearse RM, European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA) and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), European Society of Anaesthesiology, European Society of Intensive Care Medicine: Standards for definitions and use of outcome measures for clinical effectiveness research in perioperative medicine: European Perioperative Clinical Outcome (EPCO) definitions: a statement from the ESA-ESICM joint taskforce on perioperative outcome measures. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2015; 32:88–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abbott TEF, Fowler AJ, Pelosi P, Gama de Abreu M, Møller AM, Canet J, Creagh-Brown B, Mythen M, Gin T, Lalu MM, Futier E, Grocott MP, Schultz MJ, Pearse RM, StEP-COMPAC Group: A systematic review and consensus definitions for standardised end-points in perioperative medicine: pulmonary complications. Br J Anaesth 2018; 120:1066–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ladha K, Vidal Melo MF, McLean DJ, Wanderer JP, Grabitz SD, Kurth T, Eikermann M: Intraoperative protective mechanical ventilation and risk of postoperative respiratory complications: hospital based registry study. BMJ 2015; 351:h3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi J-C, Saunders LD, Beck CA, Feasby TE, Ghali WA: Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005; 43:1130–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodman MS, Li Y: Nonparametric Diagnostic Test for Conditional Logistic Regression. J Biom Biostat 2012; 3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR, Gerds T, Gonen M, Obuchowski N, Pencina MJ, Kattan MW: Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology 2010; 21:128–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freundlich RE, Duggal NM, Housey M, Tremper TT, Engoren MC, Kheterpal S: Intraoperative medications associated with hemodynamically significant anaphylaxis. J Clin Anesth 2016; 35:415–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saager L, Turan A, Egan C, Mascha EJ, Kurz A, Bauer M, Besson H, Sessler DI, Hesler BD: Incidence of Intraoperative Hypersensitivity Reactions: A Registry Analysis. Anesthesiology 2015; 122:551–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haneuse S, VanderWeele TJ, Arterburn D: Using the E-Value to Assess the Potential Effect of Unmeasured Confounding in Observational Studies. JAMA 2019; 321:602–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawrence VA, Cornell JE, Smetana GW, American College of Physicians: Strategies to reduce postoperative pulmonary complications after noncardiothoracic surgery: systematic review for the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144:596–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.