Abstract

In this minireview, we provide a historical outline of the events that led to the identification and characterization of the deiodinases, the recognition that deiodination plays a major role in thyroid hormone action, and the cloning of the 3 deiodinase genes. The story starts in 1820, when it was first determined that elemental iodine was important for normal thyroid function. Almost 100 years later, it was found that the primary active principle of the gland, T4, contains iodine. Once radioactive iodine became available in the 1940s, it was demonstrated that the metabolism of T4 included deiodination, but at the time it was assumed to be merely a degradative process. However, this view was questioned after the discovery of T3 in 1952. We discuss in some detail the events of the next 20 years, which included some failures followed by the successful demonstration that deiodination is indeed essential to normal thyroid hormone action. Finally, we describe how the 3 deiodinases were identified and characterized and their genes cloned.

Keywords: thyroid; thyroxine; 3,5,3′- triiodothyronine; deiodinase; selenoprotein

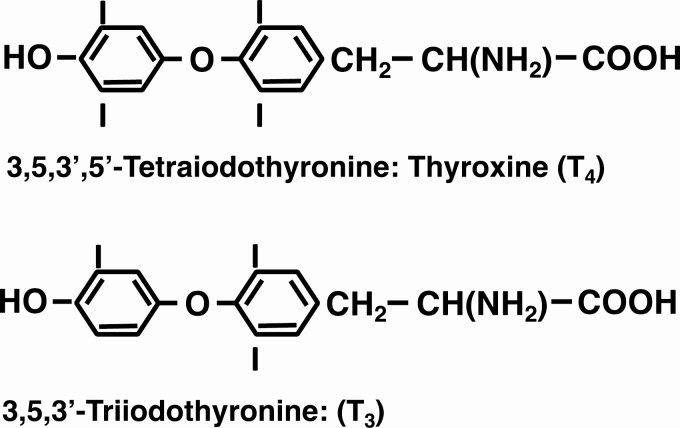

The first evidence suggesting that iodine is essential for the normal function of the thyroid gland was reported in 1820 by Coindet, who demonstrated that the recently discovered element could be used successfully to treat goiter (1). Then, in 1896, Baumann reported that the thyroid gland contains significant amounts of iodine (2). He demonstrated that it is found predominantly in a protein fraction that, on hydrolysis, yielded a substance that was effective in ameliorating the symptoms of myxedema in women and the effects of thyroidectomy in animals (3). Chemical purification of an active principle followed in 1914 when Kendall isolated a compound containing 65% iodine that he called thyroxin (4). Twelve years later, Harington determined that the compound is a tetraiodo-derivative of the p-hydroxyphenyl ether of tyrosine, with the iodine atoms probably located in the 3, 5, 3′, and 5′ positions. He renamed it thyroxine (T4) (5). (Fig. 1)

Figure 1.

The 2 major thyroid hormones: their chemical structures, names, and abbreviations.

Although it was clear that T4 accounted for much of the biological activity of the thyroid gland, there was considerable doubt that it was the circulating hormone. In fact, it was not until 1948 that Taurog and Chaikoff, using T4 labeled with radioactive iodine [131I]T4, obtained strong evidence that in normal animals most, if not all, of the organic iodine in the circulation consists of T4 bound reversibly to plasma proteins (6). That the majority of this protein-bound iodine fraction does indeed comprise T4 was demonstrated unequivocally by Laidlaw, using paper chromatographic analysis (7).

Metabolism of Thyroxine, 1940s-1960s

In the 1940s, the availability of radioactive iodine and the technique of paper chromatography opened a new era of thyroid hormone research, including studies of T4 metabolism. The first evidence that T4 metabolism included deiodination, albeit seemingly as a waste product, was provided in 1947 by Gross and Leblond, who found that when [131I]T4 was injected into rats, a significant fraction of the radioactivity appeared in urine in a form that was not T4 (8). This fraction was shown by chromatographic analysis to consist primarily of inorganic iodide (9).

Gross and Leblond also studied the various iodinated compounds present in plasma and in an extract of the thyroid gland, obtained from rats given carrier-free 131I. Some compounds were identified by co-chromatography with synthetic iodothyronines and iodotyrosines. However, several others were detected, and one of them, designated Unknown 1, was present in both the thyroid and plasma (10). This observation caught the interest of a British chemist, Dr. Rosalind Pitt-Rivers, with the result that Dr. Jack Gross joined her laboratory and together they synthesized T3 and identified Unknown 1 as T3 (11) (Fig. 1). As so often happens with major advanced in research, Roche et al. in France also synthesized T3 and used it to identify [131I]T3 in thyroid tissue from rat given [131I]iodide (12). Gross and Pitt-Rivers went on to demonstrate in 1953 that T3 was more potent physiologically than T4 (13). Pitt-Rivers had always been doubtful that T4 was the active hormone, primarily because it had a long latent period of action in vivo and was inactive in in vitro systems. The finding that T3 was more active than T4 in vivo led her to suggest that T3 was the active form of the hormone and T4 its precursor (13). If this is correct, then a deiodinating process that activates T4 by converting it to T3 must exist in peripheral tissues.

Although the hypothesis that T3 is the active form of the thyroid hormone was an attractive one, the proof was not immediately forthcoming. As early as 1955, Pitt-Rivers began to have doubts about it, primarily because, although rats responded more rapidly to T3 than to T4, the response was still measured in hours, and injected [131I]T3 disappeared more rapidly from the body than did [131I]T4 (Galton, personal communication). She was also concerned that T3, like T4, appeared to be inactive in vitro. Arguably, the more significant problem was that, despite several attempts, the presence of [131I]T3 following injection of [131I]T4 into athyreotic humans could not be demonstrated unequivocally (14, 15). At the time, it was not generally recognized that this could be due to technical limitations. Attempts to demonstrate T4 to T3 conversion in vitro were also largely unsuccessful. Although Albright et al. did report some conversion of [131I]T4 to [131I]T3 in both rat and human kidney slices (16, 17), these findings were not confirmed (18), and a plethora of other groups using a wide variety of tissues were unable to demonstrate [131I]T3 production from [131I]T4, despite the fact that deiodination of T4, as evidenced by the release of 131I, clearly occurred (19).

It was this latter phenomenon that caught the interest of Dr. Sidney Ingbar, who was on sabbatical at London’s National Institute for Medical Research, and Val Galton, Pitt-Rivers’ doctoral student. While watching the National Institute for Medical Research play cricket during the warm evenings of an atypically hot English summer, the role of deiodination in thyroid physiology was discussed from every angle. Eventually, they formulated the hypothesis that the action of T4 is linked to those processes by which it is metabolized, in particular its deiodination. They decided that the bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana, would be an ideal animal model in which to test this hypothesis because it was well known that tadpoles respond to T4, whereas adult frogs reportedly do not. After first confirming that the adult frog was indeed unresponsive to T4 in a variety of tests, including the rate of oxygen consumption, they found that it was also unable to deiodinate [131I]T4 in either slices or homogenates of its peripheral tissues. In contrast, significant deiodination of [131I]T4 was observed in both slices and homogenates of several tadpole tissues. The major product was 131I; generation of [131I]T3 was not observed in any tissue (20).

Although the findings in amphibia were consistent with the concept that the deiodination and action of T4 were linked, they did not prove it, and concern was growing regarding the physiological significance of studies of T4 deiodination in vitro. Several investigators had reported the presence in tissues of a T4 deiodinating system that was heat stable, suggesting that a process not mediated by an enzyme was involved. Heat-stable deiodination was especially notable in broken cell preparations (19). It was also suggested that T4 deiodination, at least in some tissues, was mediated by a hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-peroxidase system that is inhibited by catalase (21, 22). However, this concept was not widely considered to have physiological relevance because H2O2 also deiodinated T4 in boiled tissue preparations and even in the absence of tissue (21, 22). Other compounds found to stimulate deiodination in vitro included ferrous ions, ascorbic acid, and flavin compounds. Many of these effects were also seen in tissue preparations that had been boiled. They may have been mediated by H2O2; H2O2 can be generated by the auto-oxidation of flavin compounds in the presence of oxygen and light, and by a ferrous ion-ascorbic acid-oxygen system (19, 23). By the mid-1960s, it had become evident that data obtained from studies of T4 deiodination in vitro were difficult to interpret and could easily lead to erroneous conclusions concerning enzymatic deiodination. Thus, interest in the technique as a research tool waned in favor of studies in vivo, in particular the isotopic equilibrium technique originally developed by van Middlesworth (24). To study deiodination, this involved giving rats a daily injection of [131I]T4. Once the daily output of radioactivity in urine and feces became constant, the model could be used to test the effects of substances or conditions on the urinary output of [131I]iodide as a measure of T4 deiodination. The first studies were reported by Jones and van Middlesworth (25) and Escobar del Rey and Morreale de Escobar (26). Both groups found that when 6-n-propyl-2-thiouracil (PTU) was given to rats equilibrated isotopically with [131I]T4, the urinary excretion of [131I]iodide was reduced to approximately one-half the normal value (25, 26). This was the first clear evidence that PTU partially inhibited the peripheral deiodination of T4. The technique was also used in a study that showed that the clearance of T4 from plasma is increased in hyperthyroidism due in part from an increase in the deiodination of T4 (27). However, it was not possible from any of these studies to determine whether deiodination was a process essential for thyroid hormone action, or merely one by which the T4 was degraded.

Deiodination and Thyroid Hormone Action

The turning point regarding the role of deiodination in thyroid physiology came in the next decade as a result of 2 major findings. First, in 1970, using highly sensitive techniques, which included thyroid hormone displacement technology, Braverman et al. demonstrated unequivocally that T4 to T3 conversion occurs in athyreotic humans (28). In the same year, Sterling et al. provided additional proof by demonstrating the production of [14C]T3 in euthyroid human subjects injected with [14C]T4. They estimated that as much as one-third of the extrathyroidal T4 was metabolized by conversion into T3 (29). In rats, it was estimated that at least 20% of the total body extrathyroidal T3 was derived by conversion from T4 (30). Second, the identification and characterization of high-affinity, low-capacity binding sites for T3 in 1972 provided robust evidence that T3 is indeed the major player in thyroid hormone action. These binding sites, located in the nucleus, were first reported by Oppenheimer et al. (31), and they were found to have a much higher affinity for T3 than for T4 (32). Together, these two findings indicated that 5′-deiodination (5′D) is an essential component of thyroid hormone action.

Biochemical Characterization of the Deiodinases

Once the importance of 5′D was recognized, interest turned to the identification and characterization of the specific enzyme(s) involved. Visser et al. established that thiol groups were essential cofactors for deiodination in vitro and, in the presence of dithiothreitol, subcellular fractions of rat liver readily deiodinated T4 to T3 (33). Silva and Larsen subsequently showed that, 1 to 2 hours following IV injection of T4 into thyroidectomized rats, T3 was present in the pituitary nuclei in an amount equal to the level needed for acute suppression of TSH. T4 was not detected in the nuclei, and the plasma T3 level was negligible. These results suggested that suppression of TSH release in hypothyroid rats occurs by nuclear receptor interaction with T3 derived from intrapituitary monodeiodination of T4 (34).

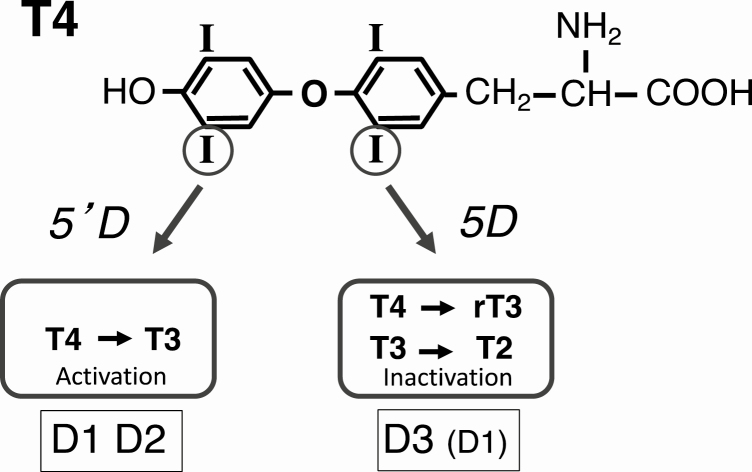

Next came the critical demonstration that there were in fact 2 enzymes that catalyze the conversion of T4 to T3, designated the type 1 and type 2 deiodinases (D1 and D2) (35-37). The 2 enzymes were distinguished initially because the D1, in contrast to the D2, was found to be highly sensitive to inhibition by PTU (36). The D1 is a dual-purpose enzyme capable of both activating T4 by 5′D and inactivating it by inner ring or 5-deiodination (5D). It is also notable that the preferred substrate of D1 for 5′D is not T4, but rT3. D1 activity is most abundant in the liver, kidney, and thyroid, but it is also expressed at a relatively low level in many other tissues (38). It has been widely accepted that the D1 is responsible for the generation of most of the extrathyroidal T3. However, this view has been challenged by the findings that the D2 is the major source of plasma T3 in the euthyroid human (39), and that the plasma level of T3 is not decreased in mice with impaired D1 expression (40, 41).

The D2 catalyzes only 5′D, and its KD for T4 is in the nanomolar range, approximately 3 orders of magnitude lower than that of the D1 (35). In contrast to the D1, the substrate preference of the D2 for T4 is greater than that for rT3. D2 activity is most abundant in pituitary, brain, and brown adipose tissue (BAT), but it is also found at lower levels in other tissues (42).

A third deiodinase (D3) catalyzes only 5D and thus inactivates both T4 and T3. 5D of the 2 hormones was first demonstrated in cultured monkey hepatocarcinoma cells (43). D3 activity is most abundant in the rodent placenta and pregnant uterus (44) and the human uteroplacental unit (45). It is present at lower levels in many fetal and neonatal tissues (37, 42), most notably in the brain, where it is thought to protect this organ of the fetus from excessively high levels of T3 (46). In the nonpregnant adult, D3 activity is found predominantly in the brain and skin (42). The major functions and substrates of the deiodinases are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

The major functions and substrates and products of the 3 deiodinases.

Attempts to Identify and Purify the Deiodinase Proteins

Over the ensuing years, culminating in the late 1980s, considerable efforts in numerous laboratories were dedicated to the identification and purification of the deiodinase enzymes, using strategies such as affinity labeling, combined with treatments with compounds known to induce deiodinase protein expression or to activate or inhibit enzyme activity. D2 activity had been shown to be induced by cAMP in rat brain astrocytes (47). Farwell and Leonard used N-bromoacetyl-[125I]T4 (BrAc[125I]T4) to affinity label cellular T4-binding proteins in rat glial cells, and identified 3 prominent radiolabeled bands. One protein, with apparent molecular weight of ~27 kDa, was increased 5- to 6-fold after treating the cells for 16 hours with dibutyryl cAMP (48), implicating this protein as a potential deiodinase or thyroid hormone-binding deiodinase subunit. Kohrle et al., using a similar approach with BrAc[125I]T4 and T3 in rat liver and kidney, also identified an ~27 kDa-labeled protein and revealed differential affinity labeling in the presence of noncovalently bound inhibitors or substrates of 5′-deiodinase (49).

Meanwhile, in Reed Larsen’s laboratory, postdoctoral researcher Marla Berry attempted purification of D2 from BAT after overnight cold exposure of rats to induce its expression. Fractionation of BAT homogenates through various column chromatography matrices followed by assaying for deiodination of [125I]T4 resulted in enrichment of deiodinase enzyme activity per unit of protein, but also yielded vanishingly small amounts of protein and eventual loss of enzyme activity. Switching to liver tissue and D1 assays with [125I]rT3 yielded similarly frustrating results. Although purification of the deiodinases proved to be problematic, insights gained from these efforts were informative for their subsequent characterization and the eventual cloning of their genes.

After many Sunday night trips to the laboratory to place rats in individual cages and push the cart of cages into the cold room, followed by week after week of purification and frustration, Larsen came into the laboratory with a new approach for Berry to try—expression cloning in Xenopus laevis oocytes. He explained the methodology he had learned about from a colleague—isolate mRNA from a candidate tissue, size-fractionate the mRNA, inject fractions into individual oocytes, allow ~2 days for the oocytes to express proteins from the injected mRNA, and assay for the activity of interest, in this case, deiodination. The active fraction(s) indicate the size of the mRNA encoding the enzyme activity, and thus the protein. The preparation of mRNA would then be scaled up, and the appropriate size fraction used for producing a cDNA library. After transformation of bacteria and isolating colonies, DNA preparations would be used to in vitro transcribe mRNA, which would again be injected into oocytes, followed by incubation and enzyme assay. What could be easier?

Cloning of the D1

Berry and a new postdoctoral trainee in the Larsen laboratory, Anna-Lisa Kates, induced hypo- or hyperthyroidism in rats with methimazole in drinking water or injection of T4, respectively. They isolated liver mRNA from hypo-, hyper-, and euthyroid rats and injected aliquots into Xenopus oocytes. Their results showed that expressed enzyme activity correlated closely with thyroid status, indicating that thyroid hormone regulates the D1 at the level of mRNA expression. Size fractionation of mRNA followed by the same assay revealed the D1 mRNA to be between 1.9 and 2.4 kb in length (50).

Berry and Kates presented the work in a poster at a meeting in 1989, where 2 colleagues told them that their group had cloned the D1, and the paper was in press. Concerned and upset, Kates and Berry shared the news with Dr. Larsen and colleague Dr. Ron Koenig, who returned with them to their poster and queried the purported deiodinase cloners, who backed off from their story.

Reassured that they had not yet been scooped, they returned to the laboratory. The next step, producing a cDNA library from the active fraction to transcribe in vitro, with the goal of obtaining transcripts that produced enzyme activity, turned out to be more challenging than anticipated. Injection of transcripts from the first library produced no deiodinase activity. Generation and screening of numerous additional libraries yielded the same result. The challenge is that to produce a functional protein, one needed a full-length cDNA. With repeated attempts at mRNA isolation and cDNA synthesis, the yield and quality of mRNA and cDNA improved. Eventually, the 16th library resulted in a minimal but reproducible signal of deiodinase activity above background. The next step was assessing the complexity of this cDNA library, or the total number of independent cDNAs, determined by plating serial dilutions from the library and counting colonies to give total number of transforming units. The 16th cDNA library had a predicted complexity of ~20 000 clones, an excellent yield given the narrow size fraction of mRNA, but a formidable number of clones to screen in oocytes.

The number of oocytes to be injected in the screening process could be greatly reduced using a matrix approach. The transformation mixture was divided into a grid of tubes, and aliquots pooled from each of the samples in a column and from each in a row. If any row or column produced a “hit” with enzyme activity significantly above background, the individual pools in that row or column would be assayed. With a hit in both a row and a column, the focus would be on the single tube at the intersection. The matrix approach was successful, and the intersecting pool was further subdivided until a single positive clone that encoded a high level of D1 activity upon microinjection into oocytes was isolated. The identity of the clone as D1 was confirmed following transfection of the cDNA into mammalian cells in culture and expression of deiodinase activity. Further, a labeled protein band of ~27 kDa was observed upon incubation of G21-transfected cell lysates with BrAc[125I]rT3. Neither enzyme activity nor the ~27 kDa band were detected in empty vector-transfected cell lysates.

Upon sequencing, Berry and colleagues found out that they had indeed been very fortunate as the ~2.1 kb cDNA began only 6 nucleotides upstream of the ATG start codon. Had it been 7 nucleotides shorter, it would not have expressed activity. But sequencing also revealed an enigma; the open reading frame (ORF) ended with a TGA/UGA stop signal at codon 126, and was predicted to encode an ~14 kDa protein. This did not agree with the BrAc[125I]T4 and T3 labeling results identifying D1 as an ~27-kDa protein reported by other laboratories and confirmed in the Larsen laboratory following transfection.

Much of the summer of 1990 was devoted to trying to unravel the mystery of how the shorter-than-expected ORF, ending with an in-frame UGA codon and predicting a protein of about one-half the expected size, could produce the ~27 kDa affinity-labeled D1 protein observed upon expression of the cDNA. Berry and Larsen considered frameshifting or readthrough mechanisms and anomalies in mRNA processing and joked about mutant DNA from outer space. They were anticipating presenting the D1 cloning at the upcoming 10th International Thyroid Congress in Jerusalem, to be held in September 1990. But they were running out of time to solve the ORF mystery.

Unexpectedly, on August 2, 1990, Saddam Hussein launched an invasion of Kuwait, resulting in cancellation of the International Thyroid Congress scheduled to take place the next month. This led to disappointment among many of the scientists who had hoped to visit the Holy Land, and one of the authors of this review who hoped to dive The Red Sea. The meeting was rescheduled for February 1991 in The Hague, Netherlands.

Meanwhile, Berry and Larsen poured through the scientific literature trying to elucidate the enigma of the interrupted ORF and shared their puzzling result with colleagues. Larsen had carried out a sabbatical a few years earlier in the laboratory of David Moore, a highly accomplished molecular biologist at the Massachusetts General Hospital. The sabbatical opened up a new venture for Reed, applying molecular biology approaches to study thyroid hormone regulation of gene expression. He shared the enigmatic ORF result with Moore, who did not have an explanation, but he astutely directed Reed to a colleague who might have one. Moore’s office and laboratory neighbor, Brian Seed, a brilliant scientist and a voracious reader of scientific literature of every ilk, recalled reading about co-translational incorporation of selenocysteine at UGA codons in 2 papers from 1986, 4 years earlier. He suggested they look into this possibility, and it turned out he was right. Using site-directed mutagenesis, Berry and Larsen showed that the TGA/UGA codon was required for the synthesis of a protein with maximal deiodinase activity. Substitution of a TGT cysteine codon resulted in ~10% the level of enzyme activity, and conversion to either a leucine codon or the TAA stop codon resulted in complete loss of activity. Thus, D1 was a selenoenzyme. They submitted their paper to Nature in late September 1990 and it was accepted in early December (51). On December 31, 1990, Behne et al published a paper reporting that chemical and enzymatic fragmentation and peptide mapping indicated identity between a 75Se-labeled 27 kDa selenoprotein and a N-bromoacetyl-[125I]L-T4 affinity-labeled protein of the same size (52).

At the beginning of February 1991, the international thyroid community converged on The Hague in The Netherlands for the rescheduled 10th International Thyroid Congress. At a reception the night before the meeting was to begin, Dr. Berry encountered the colleagues from her poster presentation at the previous meeting, who were once again chatting about having identified D1, with a paper in press. She joined them for a cocktail and conversation, and was joined by Theo Visser, one of the meeting co-organizers and first author on key publications reporting identification of 2 distinct deiodinases. Visser stepped away briefly from the reception and returned a few minutes later with a copy of the January 31, 1991, edition of Nature, containing Berry and Larsen’s D1 cloning paper, which he presented to the colleagues with whom Berry was chatting. The work was presented by Berry the next morning in the opening session of the meeting.

Mechanism of Selenocysteine Incorporation

In the months following the D1 cloning, Berry and colleagues used the recently cloned D1 to investigate the mechanism of selenocysteine incorporation. They showed that successful incorporation of selenocysteine into this enzyme required a specific 3′ untranslated (3′ut) segment of about 200 nucleotides, which are not required for expression of a cysteine-mutant deiodinase. Although there was little primary sequence similarity between the 3′ut regions of these mRNAs and those encoding another selenoenzyme, glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX), the 3′ut sequences of rat GPX could substitute for the D1 sequences in directing selenocysteine insertion. Computer analyses predicted similar stem-loop structures in the 3′ut regions of the D1 and GPX mRNAs. Limited mutations in these structures reduced or eliminated their capacity to permit D1 translation. These results identified a “selenocysteine-insertion sequence” motif in the 3′ut region of these mRNAs that is essential for successful translation of D1, presumably GPX, and, as we now know, other eukaryotic selenocysteine-containing proteins (53).

Cloning of the D3

At a conference in England in 1991, Dr. Donald D. Brown (Carnegie Institution for Science) reported the isolation of a 1.5-kb cDNA, designated XL-15 (54). This had been achieved using a PCR strategy to identify cDNAs of genes induced by thyroid hormones in X laevis tadpole tail. XL-15 exhibited limited but significant sequence homology to the mammalian D1 cDNAs, including the presence of an in-frame TGA triplet within a region of high homology to the rat D1 cDNA, and thus he assumed that it encoded the amphibian D1. Dr. Galton, who was present at the meeting, expressed her concerns about this conclusion to Dr. Brown as her group had not detected any 5′D activity, characteristic of the D1, in R catesbeiana tadpole tail tissue (55). She suggested that it more likely coded for the D2 or the D3. The outcome of this conversation was a collaboration of the Brown laboratory with the Galton and St. Germain laboratories that resulted in the demonstration that, on expression in X laevis oocytes, XL-15 codes for a deiodinase with properties characteristic of a D3. It exhibited predominantly 5D activity that was resistant to inhibition by PTU (56). As in the case of the D1, the presence and importance of selenocysteine in the coding region of XL-15 was confirmed by site-directed mutagenesis, and the selenocysteine-insertion sequence element has been identified (unpublished data). Once the XL-15 had been identified as a D3 cDNA, it was used as a probe to isolate a D3 cDNA from the rat (57). D3 cDNAs have been isolated from several other species, including the human (58).

Cloning of the D2

Cloning the D2 proved to be very challenging. Despite the availability of the D1 and D3 as probes, cloning the D2 by screening, using low stringency techniques and libraries prepared from tissues known to express relatively high levels of D2 activity, repeatedly failed in both the St. Germain and the Galton laboratories. Somewhat discouraged, they began to question their approach, in part because there was some indirect evidence that suggested the D2 was not the third member of the selenodeiodinase family, as had been widely assumed (59).

Galton and St. Germain decided to table the project for the moment. However, Jennifer Davey, a research assistant in the Galton laboratory, was not happy about this decision because she was convinced that the D2 was a member of the selenoprotein family. She had closely examined the sequences of all the known D1 and D3 cDNAs and had noted that although the overall similarity between the 2 types was relatively low, all of them contained 3 relatively short but highly conserved regions, 1 of which encompassed the TGA selenocysteine codon. She hypothesized that these regions would also be present in the D2 gene and devised a protocol that enabled her to clone a cDNA for the R catesbeiana D2. First, she used a reverse transcription/PCR strategy, primers based on the sequences of the conserved regions and RNA from R catesbeiana hind limb tissue that she knew expressed relatively high levels of D2 activity. This required many repeat PCR procedures and a great deal of faith and patience. Finally, she obtained a portion of the putative coding region. She then used gene-specific primers to synthesize the 3′- and 5′-ends of the cDNA using the rapid amplification of cDNA ends procedure. The resulting cDNA coded for a protein with characteristics typical of the D2 (60). This amphibian D2 cDNA was then used as a probe to clone a D2 cDNA from rat tissues (61).

Summary

Two hundred years ago, the importance of iodine for health of the thyroid gland was reported. More than 100 years ago, we learned that iodination was an essential step in the synthesis of T4, but another 30 years would pass before it became clear that T4 underwent deiodination in peripheral tissues. For a time, it was assumed that deiodination was merely a degradative process. Nevertheless, with the demonstration in 1970 that T4 undergoes 5′D to T3 in peripheral tissues and that T3 is the primary active hormone, it became clear that deiodination is an essential component of thyroid hormone action. By the end of the century, the 3 deiodinases had been identified, characterized, and their genes cloned.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Ann Marie Zavacki, Ph.D., Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes & Hypertension, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston MA; Dr Mark Schneider, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, NH; and Drs. Lucia Seale, Ph.D., and Naghum Alfulaij, Ph.D., both of the Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI, for critically reading the manuscript and providing helpful suggestions.

Financial Support: The preparation of this paper was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant No: NIDDK R01 DK047320 to M.J.B.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BAT

brown adipose tissue

- BrAc[125I]T4

N-bromoacetyl-[125I]T4

- D1

type 1 deiodinase

- D2

type 2 deiodinase

- GPX

glutathione peroxidase 1

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- I131

iodine131

- ORF

open reading frame

- PTU

6-n-propyl-2-thiouracil

- 3′ut

3′ untranslated

- 5D

5-deiodination

- 5′D

5′-deiodination

Additional Information

Disclosures: No competing interests exist.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1. Coindet JF. Découverte 1820 d’un nouveau remède contre le goitre. Bibliothèque Universelle, Sciences et Arts, Genève, 14, 190–198, and Annales de Chimie et de Physique (Paris) 1820;15:49-59. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baumann E. Über das normale Vorkommen von Jod im Thierkorper. Ztschr Phys Chem. 1896;21:319-321. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baumann E. Über das thyrojodin. Münch h Med Wschr. 1896;43:309-311. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kendall EC. The isolation in crystalline form of the compound containing iodine which occurs in the thyroid gland. J Amer Med Assoc. 1915;64:2042-2043. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harington CR. Chemistry of thyroxine: constitution and synthesis of desiodo-thyroxine. Biochem J. 1926;20(2):300-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taurog A, Chaikoff IL. The nature of the circulating thyroid hormone. J Biol Chem. 1948;176(2):639-656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Laidlaw JC. Nature of the circulating thyroid hormone. Nature. 1949;164(4178):927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gross J, Leblond CP. Distribution of a large dose of thyroxine labeled with radioiodine in the organs of the rat. J Biol Chem. 1947;71:309-320. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gross J, Leblond CP. Metabolites of thyroxine. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1951;76(4):686-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gross J, Leblond CP, Franklin AE, Quastel JH. Presence of iodinated amino acids in unhydrolyzed thyroid and plasma. Science. 1950;111(2892):605-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gross J, Pitt-Rivers R. 3:5:3’ -triiodothyronine. 1. Isolation from thyroid gland and synthesis. Biochem J. 1953;53(4):645-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roche J, Lissitsky S, Michel R. Sur la presence de triiodothyronine dans la thyroglobuline. CR Acad Sci. 1952;234:1228-1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gross J, Pitt-Rivers R. 3:5:3’-triiodothyronine. 2. Physiological activity. Biochem J. 1953;53(4):652-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pitt-Rivers R, Stanbury JB, Rapp B. Conversion of thyroxine to 3-5-3’-triiodothyronine in vivo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1955;15(5):616-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lassiter WR, Stanbury JB. The in vivo conversion of thyroxine to 3:5:3’triiodothyronine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1958;18(8):903-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Albright EC, Larson FC, Tust RH. In vitro conversion of thyroxine to triiodothyronine by kidney slices. Proc Soc Expt Biol Med. 1954;86:137-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Albright EC, Larson FC. Metabolism of L-thyroxine by human tissue slices. J Clin Invest. 1959;38:1899-1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Albright EC, Lardy HA, Larson FC, Tomita K. Enzymatic conversion of thyroxine to tetraiodothyroacetic acid and of triiodothyronine to triiodothyroacetic acid. J Biol Chem. 1957;224(1):387-397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ingbar SH, Galton VA. Thyroid. Annu Rev Physiol. 1963;25:361-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Galton VA, Ingbar SH. Observations on the relation between the action and the degradation of thyroid hormones as indicated by studies in the tadpole and the frog. Endocrinology. 1962;70:622-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Galton VA, Ingbar SH. Role of peroxidase and catalase in the physiological deiodination of thyroxine. Endocrinology. 1963;73:596-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reinwein D, Rall JE. Nonenzymatic deiodination of thyroxine by hydrogen peroxide. Endocrinology. 1966;78(6):1248-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Galton VA. The physiological role of thyroid hormone metabolism. In: Recent Advances in Endocrinology. 8th ed. England: Churchill Press; 1969:181-206. [Google Scholar]

- 24. van Middlesworth L. A method for iodide balance studies in animals on low iodide diets. Endocrinology. 1956;58(2):235-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jones SL, van Middlesworth L. Normal I-131 L-thyroxine metabolism in the presence of potassium perchlorate and interrupted by propylthiouracil. Endocrinology. 1960;67:855-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Escobar del Rey F, Morreale de Escobar G. The effect of propylthiouracil, methylthiouracil and thiouracil on the peripheral metabolism of 1-thyroxine in thyroidectomized, 1-thyroxine maintained rats. Endocrinology. 1961;69:456-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Edwards BR, Stern P, Stitzer LK, Galton VA. The deiodination of thyroxine in hyperthyroid rats as determined by renal clearance of iodide. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1976;82(4):737-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Braverman LE, Ingbar SH, Sterling K. Conversion of thyroxine (T4) to triiodothyronine (T3) in athyreotic human subjects. J Clin Invest. 1970;49(5):855-864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sterling K, Brenner MA, Newman ES. Conversion of thyroxine to triiodothyronine in normal human subjects. Science. 1970;169(3950):1099-1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schwartz HL, Surks MI, Oppenheimer JH. Quantitation of extrathyroidal conversion of l-thyroxine to 3,5,3’-triiodo-l-thyronine in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1972;50:1124-1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oppenheimer JH, Koerner D, Schwartz HL, Surks MI. Specific nuclear triiodothyronine binding sites in rat liver and kidney. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1972;35(2):330-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Samuels HH, Tsai JS. Thyroid hormone action in cell culture: demonstration of nuclear receptors in intact cells and isolated nuclei. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973;12:3488-3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Visser TJ, Van Der Does-Tobe I, Docter R, Hennemann G. Subcellular localization of a rat liver enzyme converting thyroxine into triodothyronine and possible involvement of essential thiol groups. Biochem J. 1976;157:479-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Silva JE, Larsen PR. Pituitary nuclear 3,5,3’-triiodothyronine and thyrotropin secretion: an explanation for the effect of thyroxine. Science. 1977;198(4317):617-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Visser TJ, Leonard JL, Kaplan MM, Larsen PR. Kinetic evidence suggesting two mechanisms for iodothyronine 5’-deiodination in rat cerebral cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79(16):5080-5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Visser TJ, Kaplan MM, Leonard JL, Larsen PR. Evidence for two pathways of iodothyronine 5’-deiodination in rat pituitary that differ in kinetics, propylthiouracil sensitivity, and response to hypothyroidism. J Clin Invest. 1983;71(4):992-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leonard JL, Visser TJ. Biochemistry of deiodination. In: Hennemann G, ed. Thyroid Hormone Metabolism. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1986:189-229. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chopra I. A study of extrathyroidal conversion of thyroxine (T4) to 3,3’,5- triiodothyronine (T3) in vitro. Endocrinology. 1977;101:453-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maia AL, Kim BW, Huang SA, Harney JW, Larsen PR. Type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase is the major source of plasma T3 in euthyroid humans. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(9):2524-2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Christoffolete MA, Arrojo e Drigo R, Gazoni F, et al. Mice with impaired extrathyroidal thyroxine to 3,5,3’-triiodothyronine conversion maintain normal serum 3,5,3’-triiodothyronine concentrations. Endocrinology. 2007;148(3):954-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schneider MJ, Fiering SN, Thai B, et al. Targeted disruption of the type 1 selenodeiodinase gene (Dio1) results in marked changes in thyroid hormone economy in mice. Endocrinology. 2006;147(1):580-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bianco AC, Salvatore D, Gereben B, Berry MJ, Larsen PR. Biochemistry, cellular and molecular biology, and physiological roles of the iodothyronine selenodeiodinases. Endocr Rev. 2002;23(1):38-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sorimachi K, Robbins J. Metabolism of thyroid hormones by cultured monkey hepatocarcinoma cells. Nonphenolic ring dieodination and sulfation. J Biol Chem. 1977;252(13):4458-4463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Galton VA, Martinez E, Hernandez A, St Germain EA, Bates JM, St Germain DL. Pregnant rat uterus expresses high levels of the type 3 iodothyronine deiodinase. J Clin Invest. 1999;103(7):979-987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Huang SA, Dorfman DM, Genest DR, Salvatore D, Larsen PR. Type 3 iodothyronine deiodinase is highly expressed in the human uteroplacental unit and in fetal epithelium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(3):1384-1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hernandez A, Morte B, Belinchón MM, Ceballos A, Bernal J. Critical role of types 2 and 3 deiodinases in the negative regulation of gene expression by T3in the mouse cerebral cortex. Endocrinology. 2012;153(6):2919-2928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Leonard JL. Dibutyryl cAMP induction of type II 5’deiodinase activity in rat brain astrocytes in culture. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;151(3):1164-1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Farwell AP, Leonard JL. Identification of a 27-kDa protein with the properties of type II iodothyronine 5’-deiodinase in dibutyryl cyclic AMP-stimulated glial cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(34):20561-20567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Köhrle J, Rasmussen UB, Rokos H, Leonard JL, Hesch RD. Selective affinity labeling of a 27-kDa integral membrane protein in rat liver and kidney with N-bromoacetyl derivatives of L-thyroxine and 3,5,3’-triiodo-L-thyronine. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(11):6146-6154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Berry MJ, Kates AL, Larsen PR. Thyroid hormone regulates type I deiodinase messenger RNA in rat liver. Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4(5):743-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Berry MJ, Banu L, Larsen PR. Type I iodothyronine deiodinase is a selenocysteine-containing enzyme. Nature. 1991;349(6308):438-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Behne D, Kyriakopoulos A, Meinhold H, Köhrle J. Identification of type I iodothyronine 5’-deiodinase as a selenoenzyme. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173(3):1143-1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Berry MJ, Banu L, Chen YY, et al. Recognition of UGA as a selenocysteine codon in type I deiodinase requires sequences in the 3’ untranslated region. Nature. 1991;353(6341): 273-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wang Z, Brown DD. Thyroid hormone-induced gene expression program for amphibian tail resorption. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(22):16270-16278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Galton VA, Hiebert A. The ontogeny of iodothyronine 5’-monodeiodinase activity in Rana catesbeiana tadpoles. Endocrinology. 1988;122(2):640-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. St Germain DL, Schwartzman RA, Croteau W, et al. A thyroid hormone-regulated gene in Xenopus laevis encodes a type III iodothyronine 5-deiodinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(16):7767-7771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Croteau W, Whittemore SL, Schneider MJ, St Germain DL. Cloning and expression of a cDNA for a mammalian type III iodothyronine deiodinase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(28):16569-16575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Salvatore D, Low SC, Berry M, et al. Type 3 lodothyronine deiodinase: cloning, in vitro expression, and functional analysis of the placental selenoenzyme. J Clin Invest. 1995;96(5):2421-2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Safran M, Farwell AP, Leonard JL. Evidence that type II 5’-deiodinase is not a selenoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(21):13477-13480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Davey JC, Becker KB, Schneider MJ, St Germain DL, Galton VA. Cloning of a cDNA for the type II iodothyronine deiodinase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(45):26786-26789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Croteau W, Davey JC, Galton VA, St Germain DL. Cloning of the mammalian type II iodothyronine deiodinase. A selenoprotein differentially expressed and regulated in human and rat brain and other tissues. J Clin Invest. 1996;98(2):405-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.