Abstract

As the international space community plans for manned missions to Mars, spaceflight-associated immune dysregulation has been identified as a potential risk to the health and safety of the flight crew. There is a need to determine whether salivary antimicrobial proteins, which act as a first line of innate immune defense against multiple pathogens, are altered in response to long-duration (>6 mo) missions. We collected 7 consecutive days of whole and sublingual saliva samples from eight International Space Station (ISS) crewmembers and seven ground-based control subjects at nine mission time points, ~180 and ~60 days before launch (L−180/L−60), on orbit at flight days ~10 and ~90 (FD10/FD90) and ~1 day before return (R−1), and at R+0, R+18, R+33, and R+66 days after returning to Earth. We found that salivary secretory (s)IgA, lysozyme, LL-37, and the cortisol-to-dehydroepiandrosterone ratio were elevated in the ISS crew before (L−180) and during (FD10/FD90) the mission. “Rookie” crewmembers embarking on their first spaceflight mission had lower levels of salivary sIgA but increased levels of α-amylase, lysozyme, and LL-37 during and after the mission compared with the “veteran” crew who had previously flown. Latent herpesvirus reactivation was distinct to the ~6-mo mission crewmembers who performed extravehicular activity (“spacewalks”). Crewmembers who shed at least one latent virus had higher cortisol levels than those who did not shed. We conclude that long-duration spaceflight alters the concentration and/or secretion of several antimicrobial proteins in saliva, some of which are related to crewmember flight experience, biomarkers of stress, and latent viral reactivation.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Spaceflight-associated immune dysregulation may jeopardize future exploration-class missions. Salivary antimicrobial proteins act as a first line of innate immune defense. We report here that several of these proteins are elevated in astronauts during an International Space Station mission, particularly in those embarking on their first space voyage. Astronauts who shed a latent herpesvirus also had higher concentrations of salivary cortisol compared with those who did not shed. Stress-relieving countermeasures are needed to preserve immunity and prevent viral reactivation during prolonged voyages into deep space.

Keywords: astronauts, herpesvirus, immunology, latent viral reactivation, spaceflight

INTRODUCTION

In the near future, the international space community will lead several exploration-class missions beyond the Van Allen radiation belt for the first time since the Apollo and Soviet Luna programs ended in the early 1970s. Current plans are to establish a station on the lunar surface, followed by manned flyby and surface exploration missions to Mars (28). Maintaining the health and safety of the crew will be key to ensuring the success of these missions, with immune dysregulation being one factor that might need to be mitigated during extended stays in space (17). Immunological concerns have been documented in astronauts beginning in the Apollo Missions, where there were several reported cases of bacterial and viral infections, and these continued onboard the Russian Mir and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Shuttle Missions (29, 32, 34, 35, 39, 40, 47). More recently, crewmembers embarking on orbital missions to the International Space Station (ISS) have experienced infections, persistent dermatitis, and/or symptoms of hypersensitivity (12). Although these have not hitherto resulted in widespread clinical issues for orbital spaceflight crew, it is likely that the risk of an adverse clinical event will be elevated during future exploration-class missions that go beyond Earth’s orbit and for longer periods of time (17).

Multiple studies have reported evidence of immune dysregulation in response to both short (~14 days) (15)- and long (~180 days) (16, 34)-duration spaceflight missions. These include altered leukocyte distribution, persistent shedding of latent herpesviruses such as Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1), and Varicella zoster virus (VZV), altered cytokine profiles, and reduced T-cell and NK-cell function (8, 10, 15, 19, 34, 35, 52). Although earlier studies were not able to differentiate between potential changes occurring during space travel and those occurring because of launch/landing stress (18, 48), more recent studies have been able to collect viable samples from crewmembers during the flight phase of a mission and have shown reductions in T-cell proliferation and cytokine production as well as NK-cell function that are independent of the potential confounding effects of landing stress (5, 16). There are a multitude of factors that can contribute to immune dysregulation during spaceflight; these parts of the “space exposome” include psychological and physical stress due to mission objectives, prolonged periods of isolation and confinement, altered macronutrient/micronutrient intake, disruptions to circadian rhythms, and “slam shifts” that occur when preparing for arriving and departing vehicles. Indeed, certain terrestrial spaceflight analogs, which mimic certain aspects of spaceflight (i.e., psychological stress, isolation/confinement) also show similar patterns of immune dysregulation (14, 36).

Psychological stress may increase susceptibility to infectious diseases (6). It is estimated that ~95% of all infections start at mucosal surfaces, including the mouth, respiratory tract, and eyes (6, 25). These vulnerable areas are protected by antimicrobial proteins (AMPs) such as cationic peptides, which include α-defensins (HNP 1–3), lactoferrin, and LL-37, as well as lysozyme and α-amylase, that prevent infection and disease by interrupting microbial entry and colonization (6, 26). As the majority of space immunology studies have focused on the cellular aspects of adaptive immunity, there is a critical need to determine whether spaceflight alters first-line innate immune defenses provided by salivary AMPs (sAMPs). The primary aim of this study was to determine the impact of an ~6-mo mission on the ISS on sAMPs and stress biomarkers associated with sympathetic nervous system (α-amylase) and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [cortisol, dehydroepianderstone (DHEA) and cortisol-to-DHEA ratio (Cortisol:DHEA)] activity (Table 1). A secondary aim was to explore differences between experienced (“veteran”) and first-time (“rookie”) crewmembers and to establish relationships between salivary AMPs and reactivation of the latent herpesviruses CMV, EBV, HSV-1, and VZV. We report here that several AMPs are elevated during spaceflight and immediately upon return to Earth and that the response is more pronounced in rookie crewmembers. We also report that latent viral reactivation is associated with increased cortisol concentrations and distinct to those crewmembers who performed extravehicular activity (EVA) on the ISS.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial proteins and hormones measured and functions

| Salivary Biomarker | Clinical Significance | References |

|---|---|---|

| α-Amylase | Growth inhibitory element for bacteria; measure of sympathetic-adrenal-medullary activation | (26, 53, 54) |

| CRP | Increased levels can indicate inflammation or tissue damage | (22, 38) |

| Cortisol | Key role in stress response; reflects HPA activity, can have immunosuppressive effects | (22, 42, 54) |

| DHEA | Antiglucocorticoid properties; counterbalances negative effects of cortisol | (42, 55) |

| Cortisol-to-DHEA ratio | Opposing effects (dualistic balance); higher levels can indicate immune dysregulation | (37, 42, 55) |

| HNP 1–3 | Antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, cationic properties | (3, 26) |

| Lactoferrin | Antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral; blocks LPS; cationic properties | (26, 53) |

| LL-37 | Antibacterial; immune modulating activity; cationic properties | (21, 26) |

| Lysozyme | Antibacterial; inactivates viruses | (26, 53) |

| sIgA | Main immunoglobulin in mucus secretions; immune cell activation, immune exclusion | (26, 53) |

CRP, C-reactive protein; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; HPA, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; sIgA, salivary secretory IgA.

METHODS

Participants.

Crewmembers selected for a long-duration (>100 days) mission to the ISS were recruited into the study. All crewmembers were affiliated with NASA, the European Space Agency, or the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. Parallel data and samples were collected from ground-based and sex-matched control subjects, with their biological samples being processed in the same assays as the crewmembers. A total of eight ISS crewmembers (7 men, 1 woman) and six healthy ground-based control subjects (5 men, 1 woman) participated (Table 2). Seven of the ISS crewmembers completed a ~6-mo mission, whereas one crewmember spent ~1 yr onboard the ISS. The crew were prospectively classified as a veteran (defined as having had previous spaceflight experience) or a rookie (defined as having no previous spaceflight experience) and retrospectively classified as either a latent viral “shedder” [defined as shedding at least 1 of 4 measured herpesviruses (CMV, EBV, HSV-1, or VZV) at any study time point] or a “nonshedder” (defined as shedding none of these viruses). All participants provided written informed consent before participating, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at NASA and the University of Houston, respectively.

Table 2.

Characteristics of ISS crewmembers and control subjects after completing study

| ISS Crewmembers |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rookie (n = 4) |

Veteran (n = 4) |

Control Subjects (n = 6) |

|

| Age, yr | 41 (37–45) | 53 (51–53) | 33 (27–42) |

| Sex | 3 Male, 1 female | 4 Male | 5 Male, 1 female |

| Length of mission, days | 175 (166–199) | 210 (137–340) | N/A |

| No. of space flight missions | 1 (1) | 3.75 (2–6) | N/A |

| No. of crewmembers completing EVAs during mission | 2 | 3 | N/A |

Data are mean (range) for n = 8 International Space Station (ISS) crewmembers and 6 control subjects. EVA, extravehicular activity; N/A, not applicable to control group.

Experiment design overview.

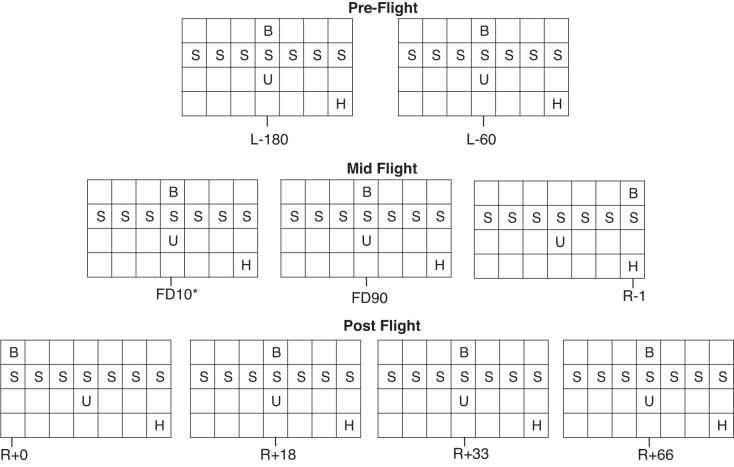

Data were collected before, during, and after each mission. A total of nine mission time points occurred over the duration of the study (~14 mo). Two preflight data collections occurred ~180 days before launch (L−180) and ~60 days before launch (L−60). Three in-flight samples were collected at flight day ~10 (FD10), flight day ~90 (FD90), and 1 day before return to Earth (R−1). Four postflight measurements were collected: immediately upon return to Earth (R+0) and at R+18, R+33, and R+66. Questionnaire response data, saliva, blood, and 24-h urine samples were obtained from each crewmember and control subject at all nine data collection points. At each mission time point, saliva was collected for 7 consecutive days and subsequently pooled into a single sample for analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Data were collected over a 7-day period on 9 separate mission time points: L−180, L−60, FD10, FD90, R-1, R+0, R+18, R+33, R+66. Time points are n days before launch (L−n), n days into flight (FDn), and n days after return to Earth (R+n). B, single blood collection; S, saliva collection; U, single 24-h urine collection; H, health assessment, Profile of Mood States-Short Form and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Saliva collection.

All saliva collections were made with synthetic swabs (SalivaBio Oral Swabs; Salimetrics, State College, PA). Participants were instructed to provide saliva samples immediately after waking, before eating, brushing teeth, or exercising. Separate swabs were used to collect sublingual saliva and total saliva (participants were instructed to roll the swab around the entire mouth). To measure salivary flow rate (mL/min), one sublingual sample from each day of collection was timed, transferred to a preweighed vial, and reweighed before sample processing (salivary density was assumed to be 1 g/mL). At each mission time point, we collected saliva over 7 consecutive days and physically pooled these into a single sample for analysis. The salivary flow rate measured with each collection was averaged over the 7 days. All saliva swabs were immediately stored at −20°C (transferred to −80°C within 2–3 wk) while on Earth or at −80°C onboard the ISS.

Blood and urine collection.

All participants provided a resting blood sample at each of the nine study time points (BD Vacutainer Safety-Lok lithium heparin; BD Vacutainer, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The FD10 samples were collected into lithium heparin plasma tube polymer separator gel collection tubes (BD Vacutainer, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and immediately frozen at −80°C until return to Earth. Samples were then centrifuged at 450 g for 15 min to collect plasma; aliquoted samples were then immediately frozen at −80°C until analysis.

All participants provided one 24-h urine sample at each study time point, beginning with the first urine void immediately after waking. The total volume of urine collected was calculated at each study time point. For samples collected on orbit, urine was voided into a collection bag with a known volume of lithium chloride. Samples were then mixed, and a fixed volume was drawn and frozen on orbit at −80°C. Lithium chloride concentration was determined in the samples returned to Earth to quantify original urine volume.

Detection of salivary biomarkers.

Analyses of sAMPs and hormone levels were determined in sublingual saliva samples. The following ELISA kits were used in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions: salivary cortisol, DHEA, C-reactive protein (CRP), salivary secretory IgA (sIgA), α-amylase activity (Salimetrics, State College, PA), LL-37, HNP 1–3 (Hycult Biotech, Wayne, PA), and lactoferrin and lysozyme (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). To minimize assay variability, all samples from an individual crewmember and his/her corresponding control subject were included in the same ELISA plate for analysis. To account for hydration status and flow rate that would vary between participants, we decided to present our data as concentration, secretion, and concentration adjusted for osmolarity. Secretion rates were determined by multiplying the concentration of each salivary analyte by the salivary flow rate (mL/min). Saliva concentrations were also adjusted for osmolality, to account for potential differences in hydration status, by dividing the concentration of each analyte by the osmolarity ([Conc]:mosM). Salivary osmolality was determined with a vapor pressure osmometer (VAPRO; Wescor, Logan, UT) according to manufacturer’s instructions, and all samples were checked for blood contamination with a Salivary Transferrin/Blood Contamination Kit (Salimetrics, State College, PA). As passive drool collections are not possible on orbit, we compared the ability of each ELISA kit to detect the salivary analyte of interest with the synthetic oral swab against the “gold-standard” passive drool method in healthy participants on Earth. The Salimetrics oral swab sublingual saliva collection and passive drool methods were highly correlated (r2 ≥ 90%), and spike recovery was >90% for all biomarkers measured.

Detection of viral DNA and IgG antibody titers.

Detection of viral DNA was performed following a previously published protocol (35). Briefly, viral DNA was extracted with a QIAamp Viral DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, CA) from total saliva samples or QIAamp Viral RNA Kits (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, CA) for urine according to manufacturer’s instructions. HSV-1, EBV, and VZV DNA was measured in saliva and CMV DNA in urine by real-time PCR (ABI 7900 PCR System; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Viral serostatus (IgG) (CMV, EBV VCA, EBV EBNA, HSV-1, and VZV) was determined by ELISA (Tecan Trading, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s instructions; individuals above the “cutoff index” were determined to be seropositive.

Profile of Mood States and self-reported sleep quality.

Participants completed the Profile of Mood States (POMS)-Short Form and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaires at each study time point (9, 44). POMS questionnaires were analyzed to determine the six domains associated with mood disturbances (fatigue, vigor, tension, aggression, anger, and confusion) as well as total mood disturbance. The PSQI was scored to cover the domains of sleep quality, latency, duration, efficiency, disturbances as well as use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction.

Statistical approach.

Data are presented as means ± SE unless stated otherwise. All statistical testing was conducted with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY). Maximum-likelihood linear mixed models were used to compare the changes over time (preflight, in flight, and postflight) between crewmembers and control subjects (Group), between rookies and veterans (Experience), and between shedders and nonshedders (Shedding). Additionally, we modeled interaction effects between the independent and dependent variables. When a significant main or interaction effect was observed, post hoc tests were performed with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Fisher’s exact tests were used to determine the risk of viral reactivation for crewmembers completing EVAs. Significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Latent herpesviruses reactivate during spaceflight.

We found that four of eight ISS crewmembers shed one or more of the viruses of interest in their saliva or urine before, during, or after spaceflight (Table 3). Twenty-seven of seventy-two (38%) saliva samples collected from the ISS crew were DNA positive for at least one of the four herpesviruses (CMV, EBV, HSV-1, VZV) compared with just one of fifty-four (2%) samples collected from ground-based control subjects. Plasma IgG titers against the four herpesviruses of interest did not change over time in crewmembers (data not shown).

Table 3.

Viral serostatus by group and number of seropositive participants who shed a virus before, during, or after an ISS mission

| ISS Crewmembers |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rookie (n = 4) |

Veteran (n = 4) |

Control Subjects (n = 6) |

||||

| Seropositive | Shed | Seropositive | Shed | Seropositive | Shed | |

| CMV | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | None |

| EBV | 4 | 1 | 4 | None | 5 | None |

| HSV-1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| VZV | 3 | None | 4 | None | 6 | None |

Data are values for n = 8 International Space Station (ISS) crewmembers and 6 control subjects. CMV, Cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; HSV-1, herpes simplex virus-1; VZV, Varicella zoster virus.

Stress biomarkers are altered in ISS crew during spaceflight.

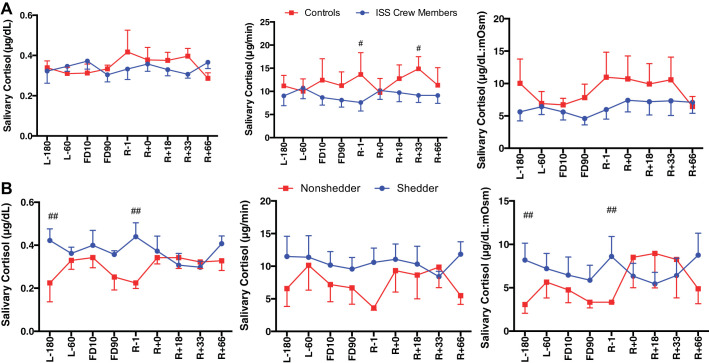

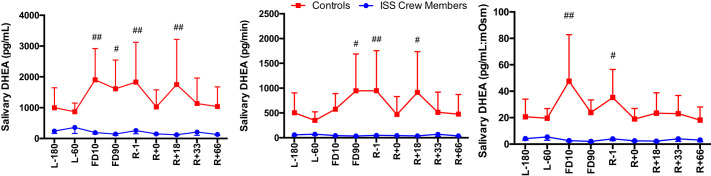

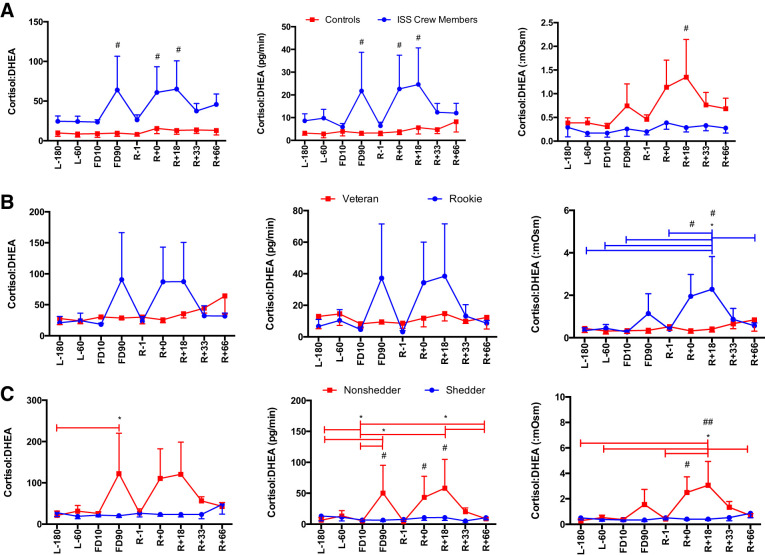

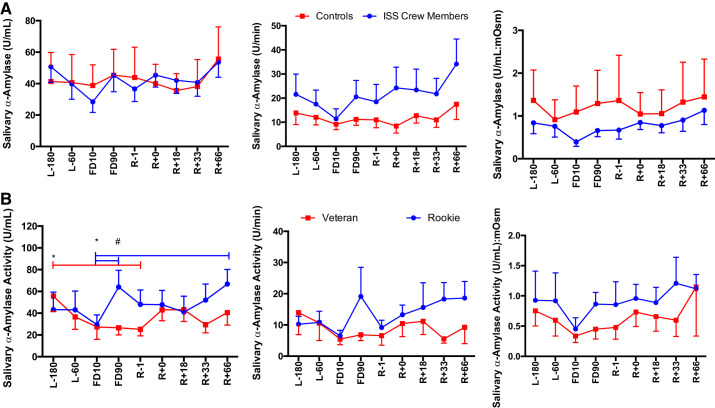

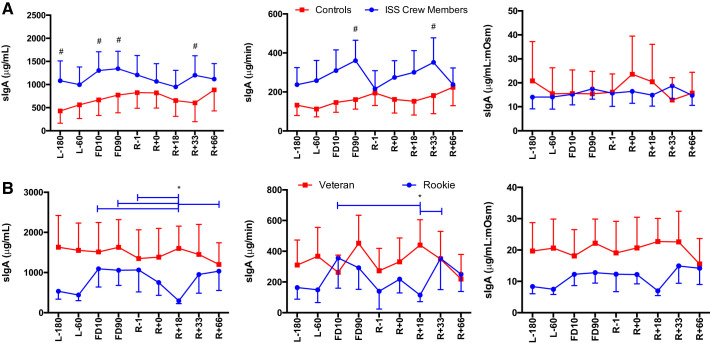

A main effect of Group was seen for cortisol secretion [F(1,113) = 16.96, P < 0.0001], with ISS crew having lower cortisol levels compared with control subjects (Fig. 2). A main effect of Group was seen for DHEA concentration [F(1,110) = 28.033, P < 0.0001], DHEA secretion [F(1,104) = 22.353, P < 0.0001], and DHEA:mosM [F(1,123) = 27.39, P < 0.0001], again with ISS crew again having lower levels of DHEA compared with control subjects (Fig. 3). A main effect of Group was seen for cortisol:DHEA [F(1,111) = 17.55, P < 0.0001], secretion of cortisol:DHEA [F(1,106) = 10.96, P = 0.001], as well as (cortisol:DHEA):mosM [F(1,123) = 11.34, P = 0.001], with ISS crew showing increased cortisol:DHEA compared with control subjects (Fig. 4). No differences were seen for salivary α-amylase concentration between groups (P > 0.05) or times (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5). A main effect of Group was found for salivary sIgA concentration [F(1,117) = 21.21, P < 0.0001] and secretion [F(1,113) = 14.08, P < 0.0001], with ISS crew having increased levels compared with control subjects (Fig. 6).

Fig. 2.

Salivary cortisol concentration, secretion, and osmolarity-adjusted concentration in International Space Station (ISS) crewmembers and ground-based control subjects (A) and shedding and nonshedding crew (B) during an ISS mission. Values are means ± SE. Time points are n days before launch (L−n), n days into flight (FDn), and n days after return to Earth (R+n). No differences were found between rookie and veteran crewmembers (data not shown). Differences between groups: #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01.

Fig. 3.

Salivary dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) concentration, secretion, and osmolarity-adjusted concentration in International Space Station (ISS) crewmembers and ground-based control subjects during an ISS mission. Values are means ± SE. Time points are n days before launch (L−n), n days into flight (FDn), and n days after return to Earth (R+n). No differences were found between rookie and veteran crewmembers or viral shedders and nonshedders (data not shown). Differences between groups: #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01.

Fig. 4.

Salivary cortisol-to-dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) ratio concentration, secretion, and osmolarity-adjusted concentration in International Space Station (ISS) crewmembers and ground-based control subjects (A), rookie and veteran crew (B), and shedding and nonshedding crew (C) during an ISS mission. Values are means ± SE. Time points are n days before launch (L−n), n days into flight (FDn), and n days after return to Earth (R+n). Differences between groups: #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01. *Differences between specific time points indicated by bars, colored to indicate specific group effect.

Fig. 5.

Salivary α-amylase activity concentration, secretion, and osmolarity-adjusted concentration in International Space Station (ISS) crewmembers and ground-based control subjects (A) and rookie and veteran crew (B) during an ISS mission. Values are means ± SE. Time points are n days before launch (L−n), n days into flight (FDn), and n days after return to Earth (R+n). No differences were found between viral shedders and nonshedders (data not shown). Differences between groups: #P < 0.05. *Differences between specific time points indicated by bars, colored to indicate specific group effect.

Fig. 6.

Salivary secretory IgA (sIgA) concentration, secretion, and osmolarity-adjusted concentration in International Space Station (ISS) crewmembers and ground-based control subjects (A) and rookie and veteran crew (B) during an ISS mission. Values are means ± SE. Time points are n days before launch (L−n), n days into flight (FDn), and n days after return to Earth (R+n). No differences were found between viral shedders and nonshedders (data not shown). Differences between groups: #P < 0.05. *Differences between specific time points indicated by bars, colored to indicate specific group effect.

Stress responses differ between rookie and veteran ISS crew.

An Experience × Time interaction was found for cortisol:DHEA (mosM) [F(8,63) = 2.26, P = 0.034] with rookies having a higher cortisol:DHEA after flight (Fig. 4). A main effect of Time [F(8,64) = 2.80, P = 0.010] and an Experience × Time interaction [F(8,64) = 3.39, P = 0.003] were found for α-amylase concentration, with rookies again showing increased levels during flight (Fig. 5). A Time × Experience interaction was found for salivary sIgA concentration [F(8,63) = 3.105, P = 0.005] and secretion [F(8,61) = 2.83, P = 0.010], with rookies showing lower levels than veterans (Fig. 6). No differences were seen in cortisol or DHEA between rookies and veterans (data not shown).

Viral shedders have higher levels of salivary cortisol but lower cortisol:DHEA than nonshedders.

A Shedding × Time interaction [F(8,64) = 2.680, P = 0.013] was seen for cortisol concentration, whereas a main effect of Group [F(1,124) = 8.157, P = 0.005] was seen for cortisol:mosM, with shedding crew having increased levels compared with nonshedding crew (Fig. 2). A main effect of Time [F(8,58) = 2.136, P = 0.047] and a Shedding × Time interaction [F(8,58) = 2.581, P = 0.018] were found for the concentration of cortisol:DHEA as well as a main effect of Time [F(8,55) = 2.48, P = 0.023] and a Time × Shedding interaction [F(8,55) = 3.04, P = 0.007] for the secretion of cortisol:DHEA, and finally a Shedding × Time interaction [F(8,63) = 2.417, P = 0.024] was seen for (cortisol:DHEA):mosM, with shedding crewmembers showing lower and more stable levels over time (Fig. 4). No differences were seen for DHEA, α-amylase, or sIgA between shedders and nonshedders (data not shown).

sAMP concentrations are increased during spaceflight, particularly in rookie crewmembers.

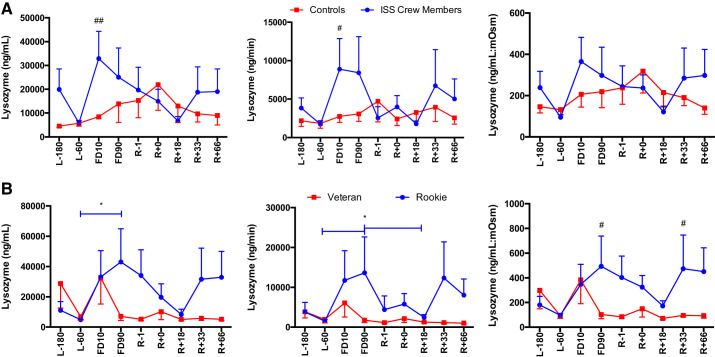

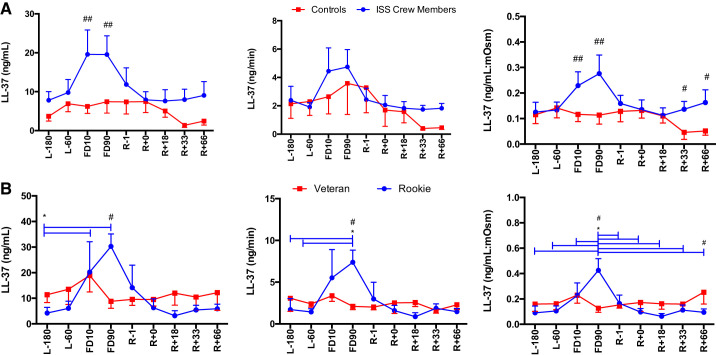

A main effect of Group was found for lysozyme concentration [F(1,124) = 6.42, P = 0.013] and secretion [F(1,118) = 4.67, P = 0.033] (Fig. 7), with ISS crew having elevated levels compared with control subjects. A main effect of Group was also seen for LL-37 concentrations [F(1,123), P < 0.0001] and LL-37:mosM [F(1,122) = 17.36, P < 0.0001] (Fig. 8), again with ISS crew having elevated levels compared with control subjects.

Fig. 7.

Salivary lysozyme concentration, secretion, and osmolarity-adjusted concentration in International Space Station (ISS) crewmembers and ground-based control subjects (A) and rookie and veteran crew (B) during an ISS mission. Values are means ± SE. Time points are n days before launch (L−n), n days into flight (FDn), and n days after return to Earth (R+n). No differences were found between viral shedders and nonshedders (data not shown). Differences between groups: #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01. *Differences between specific time points indicated by bars, colored to indicate specific group effect.

Fig. 8.

Salivary LL-37 concentration, secretion, and osmolarity-adjusted concentration in International Space Station (ISS) crewmembers and ground-based control subjects (A) and rookie and veteran crew (B) during an ISS mission. Values are means ± SE. Time points are n days before launch (L−n), n days into flight (FDn), and n days after return to Earth (R+n). No differences were found between viral shedders and nonshedders (data not shown). Differences between groups: #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01. *Differences between specific time points indicated by bars, colored to indicate specific group effect.

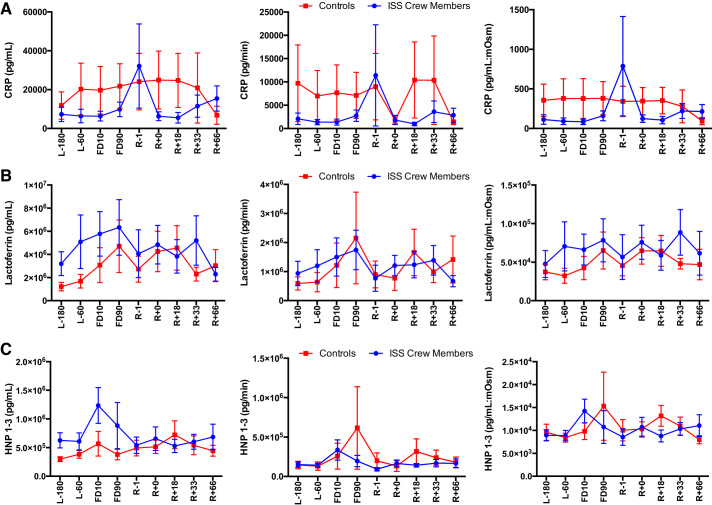

A main effect of Time [F(8, 63) = 2.513, P = 0.019] as well as a Flight Status × Time interaction [F(8,63) = 2.737, P = 0.012] were seen for lysozyme concentration, a main effect of Time [F(8,61) = 2.37, P = 0.027] for lysozyme secretion, and finally a Flight Status × Time interaction [F(8,63) = 2.52, P = 0.019) was seen for lysozyme:mosM (Fig. 7), with rookie crewmembers having increased levels compared with veterans. A main effect of Time [F(8,63) = 4.17, P < 0.001] and a Flight Status × Time interaction [F(8,63) = 4.17, P < 0.0001] were seen for LL-37 concentration, a main effect of Time [F(8,61) = 3.02, P = 0.006] and a Time × Flight Status interaction [F(8,61) = 2.708, P = 0.013] were seen for LL-37 secretion, and finally a main effect of Time [F(8,63) = 3.431, P = 0.002] and a Flight Status × Time interaction [F(8,63) = 4.741, P < 0.0001] were seen for LL-37:mosM levels (Fig. 8), again with increases seen in rookie crewmembers during flight compared with veterans. No Group or Time main effects were seen for CRP, lactoferrin, or HNP 1–3 concentration or secretion (P > 0.05) (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Salivary C-reactive protein (CRP; A), lactoferrin (B), and HNP 1–3 (C) are not affected by an International Space Station (ISS) spaceflight mission: concentration, secretion, and osmolarity-adjusted concentration in ISS crewmembers and ground-based control subjects during an ISS mission. Values are means ± SE. Time points are n days before launch (L−n), n days into flight (FDn), and n days after return to Earth (R+n). No differences were found between rookie and veteran crewmembers or between viral shedders and nonshedders (data not shown).

Changes in salivary biomarkers are not related to sleep quality or mood state in response to an ISS mission.

A Time × Group interaction was seen for vigor [F(8,68) = 3.076, P = 0.005], with ISS crewmembers reporting lower scores for vigor at R+18 compared with both L−60 and FD90 (P < 0.05). Overall, the ISS crew reported stable results throughout the mission for all other domains of mood state (data not shown). ISS crewmembers reported stable sleep constructs (data not shown); however, a main effect of Time was seen for overall PSQI score [F(8,74) = 2.738, P = 0.01], with the ISS crew having lower scores (<5) throughout the mission period (L−180 to R+66) compared with control subjects. Despite several temporal changes in salivary biomarkers observed throughout the mission, sleep quality and mood states remained stable among the ISS crew.

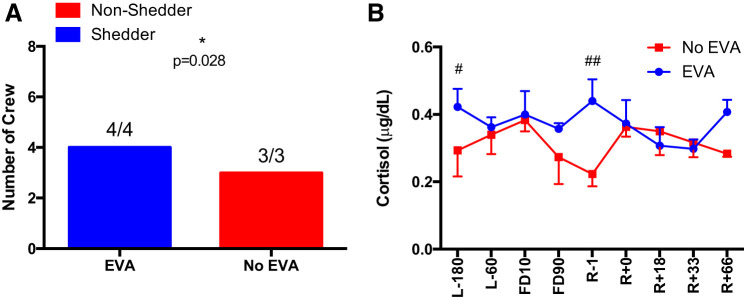

Performing EVA on the ISS is associated with latent herpesvirus reactivation.

All of the 6-mo crewmembers who were required to complete EVA on the ISS reactivated a latent herpesviruses (CMV, EBV, and HSV-1) before, during, and after the mission. Conversely, there was not a single incident of latent herpesvirus reactivation in the 6-mo crew who did not complete EVA on the ISS (P = 0.028, Fisher’s exact test) (Fig. 10). A Time × Group interaction [F(8,50) = 2.487, P = 0.018] was seen for cortisol concentration, with crew members who were required to complete EVA having higher concentrations compared with crew who did not complete EVA.

Fig. 10.

Extravehicular activity (EVA) data. A: incidence of viral shedding in crewmembers who completed an EVA during their 6-mo International Space Station (ISS) mission and those that did not perform EVAs during their mission period. B: salivary cortisol concentrations in ISS crewmembers who completed and did not complete EVA. Values are means ± SE. Differences between groups: #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01. Time points are n days before launch (L−n), n days into flight (FDn), and n days after return to Earth (R+n).

DISCUSSION

Space travel poses a significant challenge to the normal functioning of the human immune system (8, 12, 15, 16, 34, 35), which may jeopardize crew safety and compromise the successful completion of future exploration-class missions. We addressed the paucity of long-duration (>100 days) spaceflight data on the innate arm of the immune system by measuring the salivary concentration and secretion of several antimicrobial proteins before, during and after a ~6-mo mission to the ISS. We report here that salivary sIgA, lysozyme, LL-37, and cortisol:DHEA were elevated in ISS crew both before and during the mission compared with control subjects who remained on Earth. We found that many of these changes were related to flight experience, with rookie crewmembers showing lower levels of salivary sIgA but increased levels of α-amylase, lysozyme, and LL-37 during and after an ISS mission compared with their veteran counterparts. The reactivation of several latent herpesviruses was more frequent in ISS crewmembers compared with control subjects but was not statistically related to changes in sAMPs. This is the first study to show that long-duration spaceflight alters the concentration and/or secretion of several antimicrobial proteins in saliva, some of which are related to crewmember flight experience, sympathetic stress, and latent viral reactivation.

sAMPs play an important role in innate host immune defense because of their broad-spectrum antimicrobial and antiviral properties. For example, sAMPs have been shown to protect against disease-causing pathogens such as adenovirus, CMV, HSV-1, and respiratory syncytial virus, and several types of bacteria including Streptococcus (3, 20, 24, 43, 50). Although sAMPs are usually low in concentration in saliva, they can enrich to higher levels when the immune system is challenged because of stress or infection and work synergistically to attack and eliminate microbes from the mucosal surfaces (2, 26). sAMPs also respond to stressors such as exercise (1, 21, 27, 31) and medical-training scenarios (51), and the sAMP responses seen in the ISS crew here are akin to what has been reported previously in response to terrestrial stress tasks. For instance, the increase in salivary lysozyme and LL-37 concentrations seen in the ISS crew was of a magnitude similar to what we and others have reported after short (~30 min) but intense bouts of physical exercise (1, 31). The increases in α-amylase seen in rookies at FD90 were also similar to those reported in emergency room medical staff after taking part in patient-simulated training sessions (51), and the decrease seen in rookies at R+18 for sIgA is similar to a very prolonged (~2.5 h) bout of exercise (21).

Although it may seem intuitive to interpret elevations in sAMP concentrations as an indicator of enhanced innate immunity, it is possible that increases in sAMPs are actually in response to an immunological challenge, possibly due to elevated stress levels and/or latent viral reactivation. This contention is supported by the fact that an increased incidence of latent viral reactivation was seen in the ISS crew concomitantly with elevations in salivary cortisol, α-amylase, and several sAMPs including lysozyme and LL-37 as well as sIgA. Although spaceflight evoked changes in sAMPs and also triggered latent viral reactivation, we did not see differences in sAMP levels between the shedders and nonshedders. This could be due to infected crewmembers relying mostly on “adaptive” immune responses (e.g., B cells and memory T cells) to resolve the reactivation. We acknowledge, however, that these findings are correlational and could be clouded by our small sample size, low numbers of CMV- and HSV-1-infected crew, and the possibility that our nonshedders reactivated a latent herpesvirus that we did not test for (e.g., HHV6/7). In our previous study measuring AMPs in plasma of astronauts, concentrations of HNP 1–3 were inversely proportional to the amount of EBV and VZV DNA shed during flight, whereas lower LL-37 concentrations at landing were also associated with an increased incidence of CMV reactivation (46). Being in close proximity with infected crewmembers in confined space vehicles for prolonged periods of time could increase the risk of a primary and symptomatic infection in the noninfected crewmembers. In this regard, stress-induced elevations in sAMPs may protect noninfected crewmembers from primary herpesvirus infections, as certain sAMPs have been shown to interrupt microbial entry and colonization (2, 26, 50). Despite finding that half of the ISS crew in this study shed a latent virus, we did not find any evidence of primary herpesvirus infections, as all seronegative crewmembers who flew remained seronegative on return to Earth. Moreover, antibody titers (IgG) in those who were infected remained invariant throughout the mission. We did find, however, that latent viral reactivation was associated with elevations in salivary cortisol but not α-amylase, indicating that stress-induced activation of the HPA axis and not the sympathetic nervous system is a potential trigger of latent viral reactivation. We did not find changes in DHEA or cortisol:DHEA in our shedding crewmembers, but, surprisingly, we did observe higher cortisol:DHEA in the nonshedding crew. The imbalance of cortisol and DHEA has been associated with lowered immunity, as cortisol and DHEA have opposing effects on the regulation of protein kinase C activity, and thereby affect cytokine release and lymphocyte proliferation (41). This response may indicate that the shedding crewmembers do indeed see activation of the HPA axis with the increase in cortisol but still have normal adrenal function to also increase DHEA concentrations. Conversely, elevations in several sAMPs (sIgA, lysozyme, and LL-37) paralleled increases in salivary α-amylase, suggesting a possible relationship between elevated sympathetic stress responses and sAMPs. In light of these findings, it is likely that latent viral reactivation and elevations in sAMPs seen during spaceflight are not directly related but might be triggered by chronic activation of the HPA axis and the sympathetic nervous system, respectively. Finally, differences seen after flight in cortisol:DHEA and sIgA could be due to the crewmembers readapting to Earth’s gravity, increased travel and media schedules, circadian realignment, and/or nutritional changes.

Strikingly, all four of the ~6-mo ISS crew who shed a latent virus also completed extravehicular activity (EVA) on the ISS, whereas none of the nonshedding crewmembers performed EVA. EVA, or “spacewalks,” are missions completed outside the spacecraft and have been previously associated with immune dysregulation (11, 13). It is possible that the requirement to perform EVA placed additional stress on the crew, leading to greater levels of immune dysregulation that triggered latent viral reactivation. Future studies should collect biospecimens from crewmembers before and after EVAs to determine the full impact of performing such activities on the immune system during prolonged space travel. An additional factor that may influence salivary immunity is prior spaceflight experience. We report here that rookie crewmembers embarking on their first spaceflight mission had higher levels of α-amylase, lysozyme, and LL-37, but lower levels of sIgA, compared with their veteran counterparts. Mood state did not differ between these groups and generally remained invariant throughout the mission, although lower vigor was reported at R+18 in the ISS crew. Although changes in mood and sleep architecture have been shown to alter stress biomarkers and affect immunity in the terrestrial setting (4, 7, 23), we did not find temporal relationships between sleep quality or mood state and the measured salivary biomarkers. We acknowledge, however, that larger sample sizes may be needed to observe potential relationships between sleep, mood alterations, and immune/stress biomarkers in response to spaceflight.

We found that 50% of the ISS crew in this study shed at least one of the four latent herpesviruses of interest, which was considerably lower than what has previously been reported in response to both short- and long-duration space flight missions (32–35). This was largely due to the absence of a single incidence of VZV reactivation in the present study, despite VZV shedding being frequently reported in response to earlier spaceflight missions (32, 34, 35). This is likely due to recent changes in crew vaccination schedules, with Zostavax now being administered to ISS crew as a shingles prophylaxis (17). The lack of available vaccines for the other herpesviruses of interest (CMV, EBV, and HSV-1) means that crewmembers still have to rely on antivirals administered during flight, although increases in pathogen virulence seen on the ISS and in response to simulated microgravity may lead to new viral strains that become resistant to currently available medicines (49). Therefore, although Zostavax might be effective at mitigating the risk of VZV reactivation during spaceflight, latent viral reactivation still remains a concern for future space explorers. It should be noted, however, that B-cell homeostasis appears to be maintained during long-duration spaceflight (45), indicating that in-flight vaccines are likely to be effective during exploration-class missions.

Limitations of our study include an inherently small sample size and the lack of a true experimental control group (e.g., an age- and sex-matched astronaut population who remained on Earth during the study period). Additionally, some of our saliva samples returned from the ISS with small but detectable levels of transferrin, which is typically only found in blood. Elevated transferrin levels were found in crew samples collected at L−60 and FD10 but not at other mission time points or in the control samples. As lysozyme correlated with transferrin levels in crew samples, we cannot exclude the possibility that the increase in salivary lysozyme seen at FD10 is due to small traces of blood contamination. Although other markers (e.g., LL-37, sIgA, cortisol:DHEA) were elevated in crew samples at FD10, these same markers were also elevated at other mission time points (e.g., FD90) when there was no increase in, or correlation with, salivary transferrin, indicating that these changes are due to spaceflight and not influenced by possible blood contamination. It should also be noted that there was no visual evidence of blood contamination in any of the saliva samples collected throughout the study, and it has been reported that transferrin levels might be present in saliva for reasons other than blood contamination, such as age, hormones, and other oral microoganisms (30).

We conclude that long-duration spaceflight alters a wide range of sAMPs and evokes latent viral reactivation in ISS crewmembers. As these changes were linked to flight experience and/or biomarkers of sympathetic and HPA axis activity, it is likely that spaceflight immune dysregulation is a stress-related phenomenon. This is supported by the number of ground-based analogs that have been used to mimic spaceflight-associated conditions of chronic stress, particularly those that involve prolonged periods of isolation and confinement (e.g., Antarctica winterover, undersea NEEMO missions, or Haughton Mars Project), heavy work schedules, and “real-life deployment” acute stress tasks that would mimic EVAs (14). These terrestrial analogs have been shown to evoke analogous effects on immune dysregulation, with increased incidences of latent viral reactivation and altered cytokine and cell-mediated immune responses (14). Future studies should attempt to identify other aspects of the space exposome that might impact the immune system (e.g., microgravity, circadian misalignment, radiation exposure). Countermeasures focused on reducing stress may be needed to preserve crew immunity and prevent latent viral reactivation during future long-duration space exploration missions.

GRANTS

This work was supported by NASA Grants NNX12AB48G, NNX16AB29G, and NNX16AG02G to R. J. Simpson.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.K.M., D.L.P., B.E.C., and R.J.S. conceived and designed research; N.H.A., F.L.B., H.E.K., G.S., P.L.M., B.V.R., S.K.M., and B.E.C. performed experiments; N.H.A., S.K.M., and M.S.L. analyzed data; N.H.A., M.S.L., and R.J.S. interpreted results of experiments; N.H.A. prepared figures; N.H.A. and R.J.S. drafted manuscript; N.H.A., F.L.B., H.E.K., G.S., P.L.M., B.V.R., S.K.M., M.S.L., M.M.M., B.E.C., and R.J.S. edited and revised manuscript; N.H.A., F.L.B., H.E.K., G.S., P.L.M., B.V.R., S.K.M., B.E.C., and R.J.S. approved the final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allgrove JE, Gomes E, Hough J, Gleeson M. Effects of exercise intensity on salivary antimicrobial proteins and markers of stress in active men. J Sports Sci 26: 653–661, 2008. doi: 10.1080/02640410701716790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bals R Epithelial antimicrobial peptides in host defense against infection. Respir Res 1: 5, 2000. doi: 10.1186/rr25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastian A, Schäfer H. Human alpha-defensin 1 (HNP-1) inhibits adenoviral infection in vitro. Regul Pept 101: 157–161, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0167-0115(01)00282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Besedovsky L, Lange T, Haack M. The sleep-immune crosstalk in health and disease. Physiol Rev 99: 1325–1380, 2019. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bigley AB, Agha NH, Baker FL, Spielmann G, Kunz HE, Mylabathula PL, Rooney BV, Laughlin MS, Mehta SK, Pierson DL, Crucian BE, Simpson RJ. NK cell function is impaired during long-duration spaceflight. J Appl Physiol (1985) 126: 842–853, 2019. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00761.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosch JA, Ring C, de Geus EJ, Veerman EC, Nieuw Amerongen AV. Stress and secretory immunity. Int Rev Neurobiol 52: 213–253, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(02)52011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryant PA, Trinder J, Curtis N. Sick and tired: does sleep have a vital role in the immune system? Nat Rev Immunol 4: 457–467, 2004. doi: 10.1038/nri1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchheim JI, Matzel S, Rykova M, Vassilieva G, Ponomarev S, Nichiporuk I, Hörl M, Moser D, Biere K, Feuerecker M, Schelling G, Thieme D, Kaufmann I, Thiel M, Choukèr A. Stress related shift toward inflammaging in cosmonauts after long-duration space flight. Front Physiol 10: 85, 2019. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28: 193–213, 1989. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohrs RJ, Mehta SK, Schmid DS, Gilden DH, Pierson DL. Asymptomatic reactivation and shed of infectious varicella zoster virus in astronauts. J Med Virol 80: 1116–1122, 2008. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crucian B, Babiak-Vazquez A, Johnston S, Pierson DL, Ott CM, Sams C. Incidence of clinical symptoms during long-duration orbital spaceflight. Int J Gen Med 9: 383–391, 2016. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S114188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crucian B, Choukèr A. Immune system in space: general introduction and observations on stress-sensitive regulations. In: Stress Challenges and Immunity in Space: From Mechanisms to Monitoring and Preventive Strategies, edited by Chouker A Berlin: Springer, 2012, p. 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crucian B, Lee P, Stowe R, Jones J, Effenhauser R, Widen R, Sams C. Immune system changes during simulated planetary exploration on Devon Island, high arctic. BMC Immunol 8: 7, 2007. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-8-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crucian B, Simpson RJ, Mehta S, Stowe R, Chouker A, Hwang SA, Actor JK, Salam AP, Pierson D, Sams C. Terrestrial stress analogs for spaceflight associated immune system dysregulation. Brain Behav Immun 39: 23–32, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crucian B, Stowe R, Mehta S, Uchakin P, Quiriarte H, Pierson D, Sams C. Immune system dysregulation occurs during short duration spaceflight on board the space shuttle. J Clin Immunol 33: 456–465, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9824-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crucian B, Stowe RP, Mehta S, Quiriarte H, Pierson D, Sams C. Alterations in adaptive immunity persist during long-duration spaceflight. NPJ Microgravity 1: 15013, 2015. doi: 10.1038/npjmgrav.2015.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crucian BE, Choukèr A, Simpson RJ, Mehta S, Marshall G, Smith SM, Zwart SR, Heer M, Ponomarev S, Whitmire A, Frippiat JP, Douglas GL, Lorenzi H, Buchheim JI, Makedonas G, Ginsburg GS, Ott CM, Pierson DL, Krieger SS, Baecker N, Sams C. Immune system dysregulation during spaceflight: potential countermeasures for deep space exploration missions. Front Immunol 9: 1437, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crucian BE, Cubbage ML, Sams CF. Altered cytokine production by specific human peripheral blood cell subsets immediately following space flight. J Interferon Cytokine Res 20: 547–556, 2000. doi: 10.1089/10799900050044741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crucian BE, Zwart SR, Mehta S, Uchakin P, Quiriarte HD, Pierson D, Sams CF, Smith SM. Plasma cytokine concentrations indicate that in vivo hormonal regulation of immunity is altered during long-duration spaceflight. J Interferon Cytokine Res 34: 778–786, 2014. doi: 10.1089/jir.2013.0129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daher KA, Selsted ME, Lehrer RI. Direct inactivation of viruses by human granulocyte defensins. J Virol 60: 1068–1074, 1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davison G, Allgrove J, Gleeson M. Salivary antimicrobial peptides (LL-37 and alpha-defensins HNP1-3), antimicrobial and IgA responses to prolonged exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol 106: 277–284, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1020-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desai GS, Mathews ST. Saliva as a non-invasive diagnostic tool for inflammation and insulin-resistance. World J Diabetes 5: 730–738, 2014. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i6.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dimitrov S, Lange T, Nohroudi K, Born J. Number and function of circulating human antigen presenting cells regulated by sleep. Sleep 30: 401–411, 2007. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dorschner RA, Pestonjamasp VK, Tamakuwala S, Ohtake T, Rudisill J, Nizet V, Agerberth B, Gudmundsson GH, Gallo RL. Cutaneous injury induces the release of cathelicidin anti-microbial peptides active against group A Streptococcus. J Invest Dermatol 117: 91–97, 2001. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engeland CG, Hugo FN, Hilgert JB, Nascimento GG, Junges R, Lim HJ, Marucha PT, Bosch JA. Psychological distress and salivary secretory immunity. Brain Behav Immun 52: 11–17, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fábián TK, Hermann P, Beck A, Fejérdy P, Fábián G. Salivary defense proteins: their network and role in innate and acquired oral immunity. Int J Mol Sci 13: 4295–4320, 2012. doi: 10.3390/ijms13044295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gillum TL, Kuennen MR, Castillo MN, Williams NL, Jordan-Patterson AT. Exercise, but not acute sleep loss, increases salivary antimicrobial protein secretion. J Strength Cond Res 29: 1359–1366, 2015. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inclán B NASA Administrator Statement on Return to Moon in Next Five Years. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnston RS, Dietlein LF, Berry CA. Biomedical Results of Apollo. Washington, DC: Scientific and Technical Information Office, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang JH, Kho HS. Blood contamination in salivary diagnostics: current methods and their limitations. Clin Chem Lab Med 57: 1115–1124, 2019. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2018-0739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kunz H, Bishop NC, Spielmann G, Pistillo M, Reed J, Ograjsek T, Park Y, Mehta SK, Pierson DL, Simpson RJ. Fitness level impacts salivary antimicrobial protein responses to a single bout of cycling exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol 115: 1015–1027, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00421-014-3082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mehta SK, Cohrs RJ, Forghani B, Zerbe G, Gilden DH, Pierson DL. Stress-induced subclinical reactivation of varicella zoster virus in astronauts. J Med Virol 72: 174–179, 2004. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mehta SK, Crucian BE, Stowe RP, Simpson RJ, Ott CM, Sams CF, Pierson DL. Reactivation of latent viruses is associated with increased plasma cytokines in astronauts. Cytokine 61: 205–209, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehta SK, Laudenslager ML, Stowe RP, Crucian BE, Feiveson AH, Sams CF, Pierson DL. Latent virus reactivation in astronauts on the international space station. NPJ Microgravity 3: 11, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41526-017-0015-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehta SK, Laudenslager ML, Stowe RP, Crucian BE, Sams CF, Pierson DL. Multiple latent viruses reactivate in astronauts during Space Shuttle missions. Brain Behav Immun 41: 210–217, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mehta SK, Pierson DL, Cooley H, Dubow R, Lugg D. Epstein-Barr virus reactivation associated with diminished cell-mediated immunity in antarctic expeditioners. J Med Virol 61: 235–240, 2000. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michael A, Jenaway A, Paykel ES, Herbert J. Altered salivary dehydroepiandrosterone levels in major depression in adults. Biol Psychiatry 48: 989–995, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(00)00955-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pay JB, Shaw AM. Towards salivary C-reactive protein as a viable biomarker of systemic inflammation. Clin Biochem 68: 1–8, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2019.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Payne DA, Mehta SK, Tyring SK, Stowe RP, Pierson DL. Incidence of Epstein-Barr virus in astronaut saliva during spaceflight. Aviat Space Environ Med 70: 1211–1213, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pierson DL, Stowe RP, Phillips TM, Lugg DJ, Mehta SK. Epstein-Barr virus shedding by astronauts during space flight. Brain Behav Immun 19: 235–242, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pinto A, Malacrida B, Oieni J, Serafini MM, Davin A, Galbiati V, Corsini E, Racchi M. DHEA modulates the effect of cortisol on RACK1 expression via interference with the splicing of the glucocorticoid receptor. Br J Pharmacol 172: 2918–2927, 2015. doi: 10.1111/bph.13097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prall SP, Larson EE, Muehlenbein MP. The role of dehydroepiandrosterone on functional innate immune responses to acute stress. Stress Health 33: 656–664, 2017. doi: 10.1002/smi.2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Radek K, Gallo R. Antimicrobial peptides: natural effectors of the innate immune system. Semin Immunopathol 29: 27–43, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s00281-007-0064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shacham S A shortened version of the Profile of Mood States. J Pers Assess 47: 305–306, 1983. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4703_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spielmann G, Agha N, Kunz H, Simpson RJ, Crucian B, Mehta S, Laughlin M, Campbell J. B cell homeostasis is maintained during long-duration spaceflight. J Appl Physiol (1985) 126: 469–476, 2019. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00789.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spielmann G, Laughlin MS, Kunz H, Crucian BE, Quiriarte HD, Mehta SK, Pierson DL, Simpson RJ. Latent viral reactivation is associated with changes in plasma antimicrobial protein concentrations during long-duration spaceflight. Acta Astronaut 146: 111–116, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.actaastro.2018.02.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stowe RP, Mehta SK, Ferrando AA, Feeback DL, Pierson DL. Immune responses and latent herpesvirus reactivation in spaceflight. Aviat Space Environ Med 72: 884–891, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stowe RP, Pierson DL, Feeback DL, Barrett AD. Stress-induced reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus in astronauts. Neuroimmunomodulation 8: 51–58, 2000. doi: 10.1159/000026453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taylor PW Impact of space flight on bacterial virulence and antibiotic susceptibility. Infect Drug Resist 8: 249–262, 2015. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S67275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tenovuo J Antimicrobial agents in saliva—protection for the whole body. J Dent Res 81: 807–809, 2002. doi: 10.1177/154405910208101202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valentin B, Grottke O, Skorning M, Bergrath S, Fischermann H, Rörtgen D, Mennig MT, Fitzner C, Müller MP, Kirschbaum C, Rossaint R, Beckers SK. Cortisol and alpha-amylase as stress response indicators during pre-hospital emergency medicine training with repetitive high-fidelity simulation and scenarios with standardized patients. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 23: 31, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s13049-015-0110-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van ’t Hof W, Veerman EC, Helmerhorst EJ, Amerongen AV. Antimicrobial peptides: properties and applicability. Biol Chem 382: 597–619, 2001. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van ’t Hof W, Veerman EC, Nieuw Amerongen AV, Ligtenberg AJ. Antimicrobial defense systems in saliva. Monogr Oral Sci 24: 40–51, 2014. doi: 10.1159/000358783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vineetha R, Pai KM, Vengal M, Gopalakrishna K, Narayanakurup D. Usefulness of salivary alpha amylase as a biomarker of chronic stress and stress related oral mucosal changes—a pilot study. J Clin Exp Dent 6: e132–e137, 2014. doi: 10.4317/jced.51355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Young AH, Gallagher P, Porter RJ. Elevation of the cortisol-dehydroepiandrosterone ratio in drug-free depressed patients. Am J Psychiatry 159: 1237–1239, 2002. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]