Abstract

Purpose of the review:

Sleep disturbances, insomnia and recurrent nightmares in particular, are among the most frequently endorsed symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The present review provides a summary of the prevalence estimates and methodological challenges presented by sleep disturbances in PTSD, highlights the recent evidence for empirically supported psychotherapeutic and pharmacological interventions for comorbid sleep disturbances implicated in PTSD, and provides a summary of recent findings on integrated and sequential treatment approaches to ameliorate comorbid sleep disturbances in PTSD.

Recent Findings:

Insomnia, recurrent nightmares, and other sleep disorders are commonly endorsed among individuals with PTSD; however, several methodological challenges contribute to the varying prevalence estimates. Targeted sleep-focused therapeutic interventions can improve sleep symptoms and mitigate daytime PTSD symptoms. Recently, attention has focused on the role of integrated and sequential approaches, suggesting that comprehensively treating sleep disturbances in PTSD is likely to require novel treatment modalities.

Summary:

Evidence is growing on the development, course, and treatment of comorbid sleep disturbances in PTSD. Further, interventions targeting sleep disturbances in PTSD show promise in reducing symptoms. However, longitudinal investigations and additional rigorous controlled trials with diverse populations are needed to identify key features associated with treatment response in order to alleviate symptoms.

Keywords: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Sleep Disorders, Sleep Disturbances, Psychotherapy, Pharmacotherapy, Comorbidity

Introduction

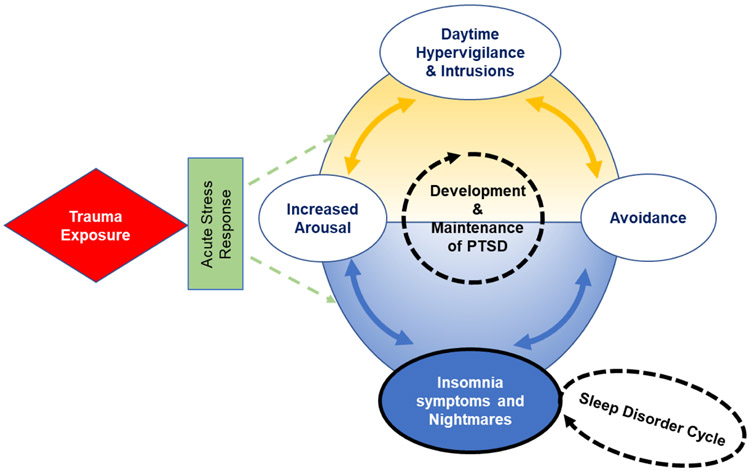

Approximately 87% of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) patients endorse subjective sleep disturbances [1]. There has been extensive growth of the literature on treatment modalities and recommendations for sleep comorbidities in PTSD within the last decade. Sleep disturbances are core features of PTSD and have been considered hallmark symptoms of the disorder [2]. These core sleep disturbances are identified within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) diagnostic criteria with nightmares or distressing dreams among the intrusion symptoms and difficulty falling or staying asleep or restless sleep among the alterations in arousal and reactivity symptoms [3]. Insomnia and recurrent nightmares are two of the most distressing symptoms of PTSD [4-6], and generally exacerbate waking symptoms of the disorder [7,8]. A depiction of the cyclic relationship between the waking and nighttime symptoms that contribute to the development and maintenance of PTSD is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

This model is a depiction of the cyclic pattern of daytime symptoms and sleep disturbances and disorders in the development and maintenance of PTSD. These cycles are potentially independent in that even if the PTSD cycle is reduced/eliminated within trauma-focused treatment, the sleep disorder cycle may remain. PTSD=Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

Although chronic insomnia and recurrent nightmares are the most commonly endorsed sleep disturbances in PTSD, other clinical sleep disorders have been implicated, including obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) [9], periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) [10], and rapid eye-movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD) [11]. Additionally, other comorbid psychiatric conditions such as mood, anxiety-related, and substance use disorders [12] can influence the clinical course of the sleep disturbances associated with PTSD, often creating an exacerbating feedback cycle. However, a majority of sleep-focused treatment approaches and outcomes have primarily focused on chronic insomnia, recurrent nightmares, and OSA.

In the past, PTSD-related sleep disturbances were viewed as secondary to PTSD but are now recognized as primary symptoms, as they contribute to the development and maintenance of PTSD [13,14], see Figure 1. Therefore, these symptoms may require tailored interventions [13]. Despite the high prevalence of sleep disturbances in PTSD, studies of the first-line treatments of PTSD, both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, seldom examine the efficacy of these therapeutic modalities for PTSD-related sleep symptoms. Clinically, this is problematic given the evidence for significant residual sleep problems during and following successful completion of evidenced-based PTSD-focused interventions [15-18]. Further, persistent sleep symptoms have the potential to compromise treatment responses to empirically supported PTSD-focused interventions. Finally, given recent evidence directly relating sleep disturbances to suicidal ideation and behaviors [19], there is a crucial need for effective sleep-focused interventions for this population.

The primary aim of this review is to highlight the recent evidence for empirically supported treatment interventions for comorbid sleep disturbances commonly implicated in PTSD (i.e. chronic insomnia, recurrent nightmares, OSA). We first provide a brief background on the prevalence and methodological challenges posed by sleep disturbances of PTSD. Finally, we review sleep-focused psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy interventions that have shown utility in treating these conditions, as well as discuss the importance of incorporating integrated and sequential treatment approaches.

Prevalence and Methodological Challenges of Sleep Disturbances in PTSD

Chronic Insomnia and PTSD

Insomnia, defined as difficulty initiating and/or maintaining sleep is the most persistent symptom endorsed among individuals with PTSD, ranging between 70%-91%. [4,20,21]. Data demonstrate that insomnia symptoms may be an antecedent rather than a consequence of PTSD [22-24]. For instance, two studies of military personnel [22,23] found soldiers with daytime sleep complaints [24] and pre-deployment insomnia [23] had significantly greater odds of developing PTSD, depression, and anxiety disorders following deployment. Similarly, insomnia symptoms at 4 months post-deployment significantly predicted PTSD symptoms as well as depression 12 months post-deployment among combat veterans [24]. These findings are consistent across populations, for example, in a civilian sample of motor vehicle survivors, subjective reports of insomnia symptoms one month after the accident predicted PTSD diagnosis a year later [25].

Although civilian and military populations with PTSD exhibit similar prevalence rates for insomnia, there are several methodological challenges to consider that may impact the rates of insomnia in PTSD-diagnosed populations. For instance, how insomnia is operationalized within a study (e.g., as a disorder with a specified frequency and duration of symptoms or as symptoms captured within PTSD), the sample characteristics or setting of a study (e.g., treatment-seeking vs population-based sample), the type of index trauma endorsed that may increase odds of insomnia (e.g. sexual/physical assault, combat-related), the type of measurement used to quantify symptoms (e.g., subjective vs objective reports), time elapsed from the index trauma (e.g. childhood vs. adult), as well as comorbid disorders known to exacerbate sleep symptoms (e.g. depression, OSA, traumatic brain injury [TBI]) [4,20,21,26].

Recurrent Nightmares and PTSD

Although insomnia symptoms often co-occur in several psychiatric disorders (e.g. depression, anxiety-related, substance abuse), recurrent trauma-related nightmares are highly specific to PTSD [27,28]. These nightmares seem to replicate part or all of the traumatic event(s) and their content is more logical and lacks the distortions characteristic of normal dreaming [27,28]. Subjective reports indicate that 52%-96% of individuals with PTSD endorse experiencing recurrent nightmares [6,20]. Recurrent nightmares also increase the risk for the development of PTSD. For instance, recurrent nightmares within one month of experiencing a traumatic event increased the risk for PTSD severity 6 weeks and one year following the trauma exposure [27,28]. Additionally, recurrent nightmares have been related to poor sleep quality, depression, and heightened risk for suicide attempts and deaths by suicide [19,31-35].

There is considerable variability in prevalence rates of recurrent nightmares. This variability is attributed to the differences in methodology, in particular, the criteria used to define and evaluate nightmares across studies [36], the PTSD status of the study sample, as well as the population being studied [37]. Another challenge in characterizing this phenomenon includes the reliance on self-report and the inability to capture nightmares during sleep laboratory monitoring, due to their infrequent occurrence in this type of setting [38].

Prevalence of Sleep Disorders in PTSD

Obstructive Sleep Apnea and PTSD

OSA is characterized by sleep-related decreases (hypopneas) or pauses (apneas) in respiration [9] leading to arousals and sleep fragmentations. The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) is the number of apneas or hypopneas recorded per hour of sleep, and the most frequently used diagnostic tool for the identification of OSA symptom severity [39]. The prevalence estimates of OSA in PTSD and other trauma-exposed populations are high, ranging from 40%-90% [40-43]. Further, evidence suggest that increased PTSD severity increases the likelihood of screening positive for OSA [44]. While the exact pathophysiological relationship between OSA and PTSD is not currently known, it has been proposed that these disorders interact and the sleep fragmentation associated with each disorder may exacerbate the vulnerability for or the consequences of the other [45]. There are several factors that may contribute to the variability of OSA presence in PTSD, particularly, related to difference in the diagnostic criteria and sample characteristics [e.g. sex, age, body mass index (BMI)]. Another important factor to consider is the methods used to generate prevalence rates. For example, some studies specifically recruit for OSA with elevated risk features (e.g. sleep disturbances), which is likely to exaggerate prevalence estimates [46]. Given these concerns, further investigation is warranted regarding the causes, consequences, and possible mechanisms related to the link between OSA and PTSD.

Periodic Limb Movement Disorder and PTSD

PLMD is a sleep-related movement disorder characterized by periodic, stereotyped limb movements during sleep. These movements, which occur predominantly in non-REM sleep, are often associated with partial arousals or awakening [10]. The prevalence rates for PLMD in the general adult population range from 4%-11%; however, data suggest that rates are much higher in individuals with PTSD compared to healthy controls [47]. For instance, two studies have assessed PLMD in combat-exposed veterans. One study found that 33% of individuals with PTSD had periodic limb movements (PLM) that ranged between 2 to 33 per hour of sleep compared to 0% in the healthy controls [48]. The second study reported that 76% of Vietnam veterans with PTSD had clinically significant PLMs that ranged from 5.6 to 190.5 per hour of sleep [49]. Other studies have also found an elevated PLM index in PTSD patients compared to controls [50].

Factors that contribute to the prevalence estimates of PLMs in individuals with PTSD are related to methodological concerns. For instance, the aforementioned studies had small samples and were limited to combat-related PTSD. Other factors are related to medication use. Specifically, central nervous systems-acting medications such as antidepressants are commonly used to treat the PTSD symptom complex which can increase PLMs during sleep, and potentially exacerbate insomnia and other sleep disorders [51,52].

Rapid Eye-Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder and PTSD

RBD is a parasomnia characterized by REM sleep without atonia on polysomnography (PSG) and dream enactment behavior [11]. Approximately 60% of RBD cases are considered idiopathic. Individuals with PTSD frequently endorse prominent movements during sleep [4], and there is substantial evidence to support REM sleep abnormalities among PTSD patients [53,54]; however, limited data exist on the relationship between RBD and PTSD. One study found that 56% of RBD patients had comorbid PTSD [55]. A more recent study found that RBD prevalence estimates increased from 9% overall to 15% in PTSD patients [56], suggesting that PTSD may be a significant predictor of RBD. A key feature of RBD, REM sleep without atonia has been observed in PTSD patients in laboratory settings; albeit in small samples. Researchers [57] have proposed a novel diagnosis, trauma-associated sleep disorder (TSD), which incorporates trauma-related nightmare enactment related to specific clinical features, and extreme nocturnal manifestations of traumatic experiences, including disruptive nocturnal behaviors (e.g., vocalizations, choking bed partner). TSD is distinct from nightmare disorder by the excessive motor activation and the nightmares that are infrequently recalled upon awakening that may be observed in both REM and non-REM sleep.

There are some factors that may influence prevalence rates and the relationship between RBD and PTSD. Specifically, the medications used to treat the PTSD symptom complex can increase the incidence of RBD, and could potentially exacerbate core sleep features (i.e., insomnia, recurrent nightmares) implicated in PTSD [58].

In summary, a range of sleep disturbances are more prevalent in individuals with PTSD compared to the general population, beyond those that are part of the diagnostic criteria. However, methodologic factors complicate drawing conclusions about the true prevalence of each sleep disorder.

Psychotherapeutic Treatments for Sleep Disturbances in PTSD

There is substantial evidence to suggest that the therapeutic treatments for PTSD are generally less effective in ameliorating the sleep disturbances than the waking symptoms of the disorder [16-18, 59]. Thus, findings highlight the need for sleep-focused interventions. Few studies have examined the efficacy and mechanisms of psychotherapeutic and pharmacological treatments for disturbed sleep in PTSD. However, some recommendations have been made regarding the few studies that have investigated the effectiveness of sleep-focused interventions in patients with PTSD. Specifically, the American Psychological Association (APA) [60] and the Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense VA/DoD [61] clinical practice guidelines for treating sleep disturbances in PTSD recommend cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) as the first line treatment for patients with insomnia disorder and PTSD. There has been inconsistency and low-grade evidence for effective treatment of trauma-related nightmares, as such, the APA and the VA/DoD makes no recommendations for the treatment of recurrent nightmares in PTSD. In contrast, there have been recommendations provided by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) for the application of imagery rehearsal therapy (IRT) for treating recurrent nightmares in PTSD as well as nightmare disorder [62].

Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment for Insomnia in PTSD

CBT-I is an evidence-based first line treatment intervention aimed at enhancing overall sleep quality [63]. CBT-I comprises instruction in stimulus control and sleep restriction, cognitive restructuring of disruptive thoughts and worries that interfere with sleep, in addition to sleep hygiene education and relaxation training [64]. Recently, a meta-analysis reported clinically relevant changes for individually delivered CBT-I in reducing sleep onset latency and wake after sleep onset, while increasing sleep quantity and sleep efficacy [65]. Another meta-analysis reported medium to large effects (.77-1.13) from pre-treatment to post-treatment for improving sleep onset latency, wake after sleep onset, and sleep efficiency [66].

More recent studies have shown CBT-I to be efficacious within PTSD samples in the community [67] and the military [68]. For example, the first randomized clinical trial (RCT) in a community sample seeking treatment for PTSD, found that compared to waitlist controls, those in the CBT-I group had superior responses on all sleep diary measures, sleep quality, and PSG derived total sleep time [67]. They also reported that subjective insomnia severity ratings fell below the clinically significant cut-off in 41% of the CBT-I group. Similarly, the military sample found that the CBT-I group had significant improvements on sleep efficiency, sleep duration, sleep quality, and insomnia severity compared to controls [68]. In addition to the targeted interventions, CBT-I has also been effective in improving other PTSD symptoms, and subsequently reducing fear of sleep, a commonly reported element of PTSD [69].

Imagery Rehearsal Therapy for Nightmares in PTSD

IRT is the best studied psychotherapeutic intervention for recurrent nightmares in PTSD, and the only recommended treatment for nightmares associated with PTSD by the AASM [62]. There is evidence that IRT leads to increased mastery of nightmare content and experiences [70]. There are several treatment protocols that share the following basic components of IRT: choosing a repetitive nightmare, rescripting, i.e., rewriting, the nightmare during waking, and imaginally rehearsing the new dream script at bedtime [71]. Two meta-analyses summarized the effectiveness of IRT for treating recurrent nightmares in PTSD [72,73]. They reported large effect sizes for nightmare frequency, sleep quality, and overall PTSD severity. However, these meta-analyses were limited due to the combination of several treatment protocols with diverse post-traumatic populations (specifically, those not diagnosed with PTSD). Another limitation included the lack of potentially active control groups.

Among veteran populations with recurrent nightmares associated with PTSD, the effectiveness of IRT treatments have been mixed. For example, in the largest study comparing IRT to an active control group [74], the IRT group did not significantly differ from those in the control group on reducing nightmare frequency and PTSD severity and increasing sleep quality. Further, neither group showed significant changes on nightmare frequency post-treatment. The authors concluded that the content of veterans’ nightmares in addition to particular changes that were made in the nightmare script during imagery rehearsal may serve as important modifiers of treatment outcomes to be addressed in future large-scale research investigations.

Exposure, Relaxation, and Rescripting Therapy for Trauma-Related Nightmares

Another psychotherapeutic intervention for trauma-related nightmares is exposure, relaxation, and rescripting therapy (ERRT). ERRT is a variant of IRT, with a specific focus on written and oral exposure to the most distressing nightmare and traumatic-related thematic rescripting [75]. Currently, ERRT is not considered a recommended treatment for PTSD-related nightmares, however, RCT’s comparing ERRT to waitlist controls have shown promise in reducing subjective reports of nightmares frequency and severity, fear of sleep, insomnia, symptoms of PTSD and depression, while increasing sleep quality and quantity among civilians with PTSD symptoms [76,77]. Among veterans, one study showed reductions in nightmare frequency and PTSD severity, while showing increased sleep time [78]. Another study in military veterans with trauma exposure found significant improvements in sleep quality, nightmare frequency and severity, insomnia, and depression [79]. Most recently, a study of ERRT specifically for active duty military personnel with trauma-related nightmares found medium effect size reductions in nightmares and other symptoms, including insomnia, PTSD, and depression compared to a minimal contact control group [80]. The most recent RCT, in a civilian population, compared ERRT to a dismantled protocol excluding the nightmare exposure and rescripting processes, and found that both groups, regardless of the inclusion of exposure and rescripting, exhibited significant improvements on nightmare frequency and distress [81]. The authors noted that the dose of exposure (i.e. single session) in the full protocol of ERRT may have been too brief to show an incremental benefit. Future works are needed to identify what treatment components work best, and for whom these treatments are most beneficial.

Overall, there are several factors to consider when examining the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral interventions for nightmares. In general, several factors may contribute to the inconsistencies across studies, particularly related to the study design (i.e. waitlist vs. active control), inclusion of individuals with and without trauma-related nightmares (thus potentially impacting the severity of baseline symptoms), and the lack of a standard treatment protocol (e.g., inclusion of different treatment components, varying number of treatment sessions). Of particular importance are the varying inclusion/exclusion of different components (e.g., specific exposure, thematic rescripting, relaxation, etc.), see Table 1 for an example of the components and protocol variations.

Table 1.

Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment-Nightmares (CBT-N) Components and Protocol Variations

| Example Protocol Variations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Components | IR (Krakow et al., 1995) [70] |

IR (Forbes et al., 2001) [104] |

IR (Germain et al., 2003) [105] |

IR (Nappi et al., 2010) [106] |

ERRT (Davis, 2009) [107] |

| Nightmare Selection | |||||

| Most Distressing | X | ||||

| Lesser Intensity | X | X | |||

| Repetitive | X | X | |||

| Exposure to Nightmare Content | |||||

| Direct exposure (Written or Oral) | X | X | |||

| No exposure | X | X | X | ||

| Sleep Behavior Modification | |||||

| Include sleep hygiene & stimulus control guidelines | X | ||||

| Relaxation Training | |||||

| Include relaxation training | X | ||||

| Psychoeducation on PTSD and Sleep | |||||

| Includes Psychoeducation | X | X | X | ||

| Rescripting Process | |||||

| Thematic Rescripting | X | ||||

| Change in “any” way | X | X | X | X | |

| Imagery Rehearsal | |||||

| Repeated imagining of new dream | X | X | X | X | X |

Note. CBT-N is a multicomponent treatment approach that typically involves psychoeducation, identifying a target nightmare, rescripting (i.e., rewriting) the nightmare, and repeatedly imagining the new dream before sleep. Some protocols include exposure, stimulus control therapy, and relaxation training. IR = Imagery Rehearsal. ERRT = Exposure, Relaxation, and Rescripting Therapy (ERRT).

Integrated and Sequential Psychotherapeutic Interventions

Given the evidence of residual insomnia and recurrent nightmares during and following PTSD-focused treatments [15,59], and that successful sleep-focused interventions may improve daytime PTSD symptoms, it is also essential to understand the potential benefit of integrated and sequential sleep-focused and PTSD-focused interventions. Recently there have been integrated protocols to examine the effectiveness of combined treatments for sleep disturbances in PTSD. Studies in both civilians [82] and veterans [83,84] using combined components of CBT-I and IRT found significant improvements in sleep quality, nightmare frequency, insomnia severity, PTSD symptoms and depression. Most recently, an RCT of CBT-I +IRT or IRT alone found significant reductions in nightmare frequency and distress, and sleep disturbances in a veteran population [85]; however, adding IRT did not contribute to significantly greater treatment benefits than those achieved with CBT-I alone. Additional studies are needed to substantiate these findings. Few investigations have included sequential approaches. Recently, a trial examining the effectiveness of IRT before CBT for PTSD compared to CBT alone found no benefit of the sequential treatment protocol on PTSD symptoms [86]. Although, the group receiving IRT did show greater improvements in nightmare frequency, nightmare distress, and sleep quality than the CBT group. Finally, there are ongoing clinical trials investigating integrated CBT-I and PE (NCT02774642), Cognitive Processing Therapy (PT) and ERRT (NCT02236390), and CPT and cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia and nightmares (CBT-in; NCT02773693) on sleep and PTSD outcomes in civilians and military personnel.

Other Therapeutic Treatments for Sleep Disturbances in PTSD

Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in PTSD

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the gold standard recommended therapy for OSA. CPAP acts as a splint to prevent the upper airway soft tissue from collapsing [87]; using air under pressure to maintain airway patency during sleep. Few investigations have provided preliminary evidence that adherence to CPAP for OSA reduces nightmare frequency in both idiopathic and trauma-related nightmare suffers. Two studies [88,89] found that a reduction in nightmare frequency was related to CPAP adherence. More recent, two additional studies [90,91] found that CPAP treatment for OSA significantly improved subjective PTSD symptoms among veterans with PTSD. They also found that the percentage of CPAP adherence predicted the observed improvements.

Pharmacological Treatments for Sleep Disturbances in PTSD

Several classes of medications have been evaluated for reducing insomnia and recurrent nightmares in PTSD patients, to include the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), typical/atypical antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants, alpha-1 and alpha-2 adrenergic receptor antagonists [92,93]. Despite, the effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions (e.g. CBT-I) demonstrating beneficial long-term outcomes over medications, benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepines receptor agonist, as well as off-label medications for sleep disturbances continue to be a primary treatment recommendation in individuals with PTSD [94].

Pharmacological Treatments for Insomnia in PTSD

There have been limited studies examining the benefits of pharmacological treatments for insomnia in individuals with PTSD. The novel non-benzodiazepine benzodiazepine receptor agonist (NBRA) zolpidem was reported to be beneficial for insomnia associated with PTSD [95]. Another study found that NBRA eszopiclone led to greater improvements in PTSD symptoms and associated insomnia relative to placebo [96]. Trazodone, a 5HT2 antagonist/SSRI, with sedative effects is frequently used in low doses to treat insomnia related to PTSD [97]. Given the limited evidence for the efficacy of pharmacological treatments for insomnia in PTSD, the VA/DoD treatment guidelines recommend medications as second-line treatments [61]. Finally, given the risk of excessive daytime sleepiness, pharmacological treatments with sedative properties should be used with caution. Recently, a clinical trial has been approved to investigate the efficacy of trazadone, eszopiclone, or gabapentin in reducing insomnia symptoms in patient with PTSD (NCT03668041).

Pharmacological Treatments for Recurrent Nightmares in PTSD

Trazodone and SSRIs, including Fluvoxamine and Nefazodone, may have some utility in treating nightmare disturbances in PTSD populations [98]. However, none of these pharmacological agents have been tested in RCTs. Additional pharmacotherapies, including topiramate, lose-dose cortisol, and gabapentin have been identified as having low level evidence for the effectiveness in managing recurrent nightmares in PTSD [98]. The greatest advancement in the pharmacological treatment of trauma-related nightmares is prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenoceptor antagonist. Studies in civilian [99] and military [100] populations have reported on the effectiveness of prazosin in the treatment of nightmares. Collectively, these studies found decreases in trauma-related nightmares and distressed awakenings not related to nightmares. They also reported improvements in sleep quality and other sleep disturbances.

A systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy of prazosin reported significant improvements in nightmare frequency, sleep quality, and PTSD severity [101]. However, a large multi-site study examining the efficacy of prazosin for combat-related PTSD, found no benefit of prazosin over placebo in reducing nightmare frequency or PTSD severity [102]. Given the mixed findings and limited evidence, the VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines make no recommendation for or against prazosin for the treatment of recurrent nightmares [62]. A recent meta-analysis investigating the efficacy of IRT and prazosin suggests that this downgrade of prazosin may be premature, as the treatment effects of prazosin were found to be comparable to those of IRT [103]. More work is needed to identify characteristics of response to these different treatment options.

Conclusions

Sleep disturbances, such as chronic insomnia and recurrent nightmares, are among the most distressing symptoms of PTSD and significantly contribute to the development, maintenance, and clinical course of the disorder. Other prominent sleep disorders, including OSA, RBD, PLMD, as well as other psychiatric disorders may be comorbid with PTSD and have implications for successful treatment. The prevalence rates of comorbid sleep disturbances in PTSD are high, but estimates may be indicative of several methodological challenges, including how sleep symptoms are operationalized within a study, sample characteristics or setting of a study, type of index trauma endorsed, type of measurement used to quantify symptoms, inability to capture specific sleep disturbances during sleep laboratory monitoring, and varying comorbid disorders known to exacerbate symptoms.

Psychotherapeutic treatments designed to specifically target chronic insomnia and recurrent nightmares have shown promise in alleviating symptoms. Clinical practice guidelines by APA and VA/DoD recommend CBT-I for insomnia, and AASM recommends IRT as a first line treatment for nightmares. The expansion of psychotherapeutic treatment modalities is encouraging; however, a lack of standardized delivery and high dropout rates continue to impose significant challenges in attaining successful outcomes. Additional RCTs are needed to understand features associated with treatment responsiveness. Pharmacological treatments for the overall PTSD symptom complex have rarely investigated the effectiveness of treatments for chronic insomnia and recurrent nightmares. Some pharmacological treatments, including antidepressants and atypical antipsychotics have provided evidence for the efficacy of sleep disturbances in PTSD, however, findings are limited due to methodological challenges and the absence of larger RCTs. Presently, the alpha-1 adrenoceptor antagonist prazosin is the only recommended pharmacological treatment for trauma-related nightmares by the AASM’s clinical practice guidelines.

Relatively few studies have directly investigated the efficacy of integrated and sequential interventions on sleep disturbances in PTSD. There is opportunity for future investigations to determine the effectiveness of integrated and sequential approaches, to examine the suitability of these treatment modalities to specific patient populations, and to identify when these approaches are warranted with other interventions.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure Statement: All Authors declare no conflicts of interest. The views expressed here are the authors’ and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. J.A.B.'s time was supported by a Center Grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Grant Number 5P20GM103653-08. K.E.M.’s time was supported by Career Development Award Number IK2 CX001874 from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Sciences R&D (CSRD) Service.

Footnotes

Human and Animal Rights Statement: This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Maher MJ, Rego SA, Asnis GM. Sleep disturbances in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder: epidemiology, impact and approaches to management. CNS Drugs 2006:20(7):567–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross R, Ball W, Sullivan K, Caroff S. Sleep disturbance as the hallmark of posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatr 1989:146(6):697–07. Doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.6.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohayon MM, Shapiro CM. Sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorder associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in the general population. Compr Psychiatry 2000:41(6):469–78. Doi: 10.1053/comp.2000.16568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krakow B, Schrader R, Tandberg D, Hollifield M, Koss MP, Yau CL, et al. Nightmare frequency in sexual assault survivors with PTSD. J Anxiety Disord 2002:16(2): 175–90. Doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leskin GA, Woodard SH, Young HE, Sheikh JI. Effects of comorbid diagnoses on sleep disturbance in PTSD. J Psychiatr Res 2002:36:449–52. Doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clum GA, Nishith P, Resick PA. Trauma-related sleep disturbance and self-reported physical health symptoms in treatment-seeking female rape victims. J Nerv Ment Dis 2001:189(9):618–22. Doi: 10.1097/00005053-200109000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westermeyer J, Khawaja I, Freerks M, Sutherland RJ, Engle K, Johnson D, et al. Correlates of daytime sleepiness in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and sleep disturbance. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2010; 12(2). Doi: 10.4088/PCC.07m00563gry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krakow BJ, Ulibarri VA, Moore BA, Melver ND. Posttraumatic stress disorder and sleep-disordered breathing: a review of comorbidity research. Sleep Med Rev 2015:24:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown TM, Boudewyns PA. Periodic limb movements of sleep in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress 1996:9(1): 129–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Husain AM, Miller PP, Carwile ST. REM sleep behavior disorder: potential relationship to post-traumatic stress disorder. J Clin Neurophysiol 2001:18(2): 148–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brady KT, Killeen TK, Brewerton T, Lucerini S. Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000:61 Suppl 7:22–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spoormaker VI, Montgomery P. Disturbed sleep in post-traumatic stress disorder: secondary symptom or core feature? Sleep Med Rev 2008:12(3): 169–84. Doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nappi CM, Drummond SP, Hall JM. Treating nightmares and insomnia in posttraumatic stress disorder: A review of current evidence. Neuropharmacology 2012:62(2):576–85. Doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belleville G, Guay S, Marchand A. Persistence of sleep disturbances following cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychosom Res 2011:70(4):318–27. Doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galovski TE, Monson C, Bruce SE, Resick PA. Does cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD improve perceived health and sleep impairment? J Trauma Stress 2009:22(3): 197–04. Doi: 10.1002/jts.20418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutner CA, Casement MD, Gilbert KS, Resick PA. Change in sleep symptoms across cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure: A longitudinal perspective. Behav Res Ther 2013:51(12):817–22. Doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larsen SE, Bellmore A, Gobin RL, Holens P, Lawrence KA, Pacella-LaBarbara ML. An initial review of residual symptoms after empirically supported trauma-focused cognitive behavioral psychological treatment. J Anxiety Disord 2019, 63:26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Littlewood DL, Gooding PA, Panagioti M, Kyle SD. Nightmares and suicide in posttraumatic stress disorder: The mediating role of defeat, entrapment, and hopelessness. J Clin Sleep Med 2016:12(3):393–99. Doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neylan TC, Marmar CR, Metzler TJ, Weiss DS, Zatzick DF, Delucchi KL, et al. Sleep disturbances in the Vietnam generation: findings from a nationally representative sample of male Vietnam veterans. Am J Psychiatr 1998:155(7):929–33. Doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.7.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plumb TR, Peachey JT, Zelman DC. Sleep disturbances is common among servicemembers and veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Psychol Serv 2014:11(2):209–19. Doi: 10.1037/a0034958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koffel E, Polusny MA, Arbisi PA, Erbes CR. Pre-deployment daytime and nighttime sleep complaints as predictors of post-deployment PTSD and depression in National Guard troops. J Anxiety Disord 2013:27(5):512–19. Doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gehrman P, Seelig AD, Jacobson IG, Boyko EJ, Hooper TI, Gackstetter GD, et al. Predeployment sleep duration and insomnia symptoms as risk factors for new-onset mental health disorder following military deployment. Sleep 2013:36(7): 1009–18. Doi: 10.5665/sleep.2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright KM, Britt TW, Bliese PD, Adler AB, Picchioni D, Moore D. Insomnia as predictor versus outcome of PTSD and depression among Iraq combat veterans. J Clin Psychol 2011:67(12): 1240–58. Doi: 10.1002/jclp.20845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koren D, Amon I, Lavie P, Klein E. Sleep complaints as early predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder: A 1-year prospective study of injured survivors of motor vehicle accidents. Am J Psychiatry 2002:159(5):855–7. Doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colvonen PJ, Straus LD, Stepnowsky C, McCarthy MJ, Goldstein LA, Norman SB. Recent advancements in treating sleep disorders in co-occurring PTSD. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2018:20(7):48. Doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0916-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schreuder BJN, Igreja V, van Dijk J, Kleijn W. Intrusive re-experiencing of chronic strife or war. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2001:7:102–8. Doi: 10.1192/apt.7.2.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mellman TA, Hipolito MS. Sleep disturbance in the aftermath of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder. CNS Spectr 2006:11 (18):611–5. Doi: 10.1017/s1092852900013663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mellman TA, David D, Bustamante V, Torres J, Fins A. Dreams in the acute aftermath of trauma and their relationship to PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2001:14(1):241–47. 10.1023/A:1007812321136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi I, Sledjesk EM, Spoonster E, Fallon WF Jr, Delahanty DL. Effects of early nightmares on the development of sleep disturbances in motor vehicle accident victims. J Trauma Stress 2008:21(6):548–55. Doi: 10.1002/jts.20368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis JL, Byrd P, Rhudy JL, Wright DC. Characteristics of chronic nightmares in a trauma-exposed treatment-seeking sample. Dreaming 2007:17(4): 187–98. 10.1037/1053-0797.17.4.187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin R, Fireman G. Nightmare prevalence, nightmare distress, and self-reported psychological disturbance. Sleep 2002:25(2):205–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nadorff MR, Nazem S, Fiske A. Insomnia symptoms, nightmares, and suicidal ideation in a college student sample. Sleep 2011:34(1):93–8. Doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.1.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernert RA, Joiner TE, Cukrowicz KC, Schmidt NB, Krakow B. Suicidality and sleep disturbances. Sleep 2005:28(9): 1135–41. Doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.9.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sjostrom N, Waern M, Hetta J. Nightmares and sleep disturbances in relation to suicidality in suicide attempters. Sleep 2007:30(1):91–5. Doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hasler B, Germain A. Correlates and treatments of nightmares in adults. Sleep Med Clin. 2009:4(4):507–17. Doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robert G, Zadra A. Measuring nightmare and bad dream frequency: Impact of retrospective and prospective instruments. J Sleep Res 2008:17(2): 132–9. Doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woodward SH. Arsenault NJ, Murray C, Bliwise DL. Laboratory sleep correlates of nightmare complaint in PTSD inpatients. Biol Psychiatry 2000:48(11): 1081–7. Doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00917-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan CM, Bradley TD. Pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol 2005:99:2440–50. Doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00772.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lydiard RB, Hamner MH. Clinical importance of sleep disturbance as a treatment target in PTSD. Focus 2009:8(2): 176–83. 10.1176/foc.7.2.foc176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krakow B, Haynes PL, Warner TD, Santana E, Melendrez D, Johnson L, et al. Nightmares, insomnia, and sleep-disordered breathing in fire evacuees seeking treatment for posttraumatic sleep disturbance. J Trauma Stress 2004:17(3):257–68. Doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000029269.29098.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krakow B, Melendrez D, Pedersen B, Johnston L, Hollifield M, Germain A, et al. Complex insomnia: insomnia and sleep disordered breathing in a consecutive series of crime victims with nightmares and PTSD. Biol Psychiatry 2001:49(11):948–53. Doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krakow B, Melendrez D, Warner TD, Clark JO, Sisley BN, Dorin R, et al. Signs and symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing in trauma survivors: a matched comparison with classic sleep apnea patients. J Nerv Ment Dis 2006:194(6):433–9. Doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000221286.65021.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colvonen PJ, Masino T, Drummond SP, Myers US, Angkaw AC, Norman SB. Obstructive sleep apnea and posttraumatic stress disorder among OEF/OIF/OND veterans. J Clin Sleep Med 2015:11(5):513–8. Doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jaoude P, Vermont LN, Porhomayon J, El-Solh AA. Sleep-disordered breathing in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015:12(2):259–268. Doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201407-299FR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richards A, Kanady JC, Neylan TC. Sleep disturbance in PTSD and other anxiety-related disorders: An updated review of clinical features, physiological characteristics, and psychological and neurobiological mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020:45(1):55–73. Doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0486-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hornyak M, Feige B, Riemann D, Voderholzer U. Periodic leg movements in sleep and periodic limb movement disorder: prevalence, clinical significance and treatment. Sleep Med Rev 2006:10:169–77. Doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mellman TA, Kulick-Bell R, Ashlock LE, Nolan B. Sleep events among veterans with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995:152:110–15. Doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown TM, Boudewyns PA. Periodic limb movements of sleep in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress 1996:9(1): 129–36. Doi: 10.1007/bf02116838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ross RJ, Ball WA, Dinge DF, Kribbs NB, Morrison AR, Silver SM, et al. Motor dysfunction during sleep in posttraumatic stress disorder. Sleep 1994:17(8):723–32. Doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.8.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Desautels A, Michaud M, Lanfranchi P, et al. Periodic limb movements in sleep In Chokroverty S, Allen R, Waters A, Montagna P, (eds). Sleep and movement disorders. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 650–63. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mohsenin S, Mohsenin V. Diagnosis and management of sleep disorders in posttraumatic stress disorder: A review of the literature. Prim Care Companion CNS. 2014:16(6). Doi: 10.4088/PCC.14r01663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kobayashi I, Boarts JM, Delahanty DL. Polysomnographically measured sleep abnormalities in PTSD: a meta-analytic review. Psychophysiology 2007:44:660–9. Doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mellman TA, Kobayashi I, Lavela J, Wilson B, Hall Brown TS. A relationship between REM sleep measures and the duration of posttraumatic stress disorder in a young adult urban minority population. Sleep 2014:37(8): 1321–6. Doi: 10.5665/sleep.3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Husain AM, Miller PP, Carwile ST. REM sleep behavior disorder: potential relationship to post-traumatic stress disorder. J Clin Neurophysiol 2001:18(2): 148–57. Doi: 10.1097/00004691-200103000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •56.Elliott JE, Opel RA, Pieshakov D, Rachakonda T, Chau AQ, Weymann KB, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder increases the odds of REM sleep behavior disorder and other parasomnias in veterans with and without comorbid traumatic brain injury. Sleep 2019: zsz237, 10.1093/sleep/zsz237.This study showed that the prevalence rates of REM behavior disorder were significantly higher in veterans with PTSD, and PTSD+ Traumatic brain injury (TBI) compared to the general population.

- 57.Mysliwiec V, Brock MS, Creamer JL, O’Reilly BM, Germain A, Roth BJ. Trauma associated sleep disorder: A parasomnia induced by trauma. Sleep Med Rev 2018:37:94–104. Doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frauscher B, Hogl B. Rem sleep behavior disorder In Chokroverty S, Allen R, Waters A, Montagna P, (eds). Sleep and movement disorders. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 406–22. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pruiksma KE, Taylor DJ, Wachen JS, Mintz J, Young-McCaughan S, Peterson AL, et al. Residual sleep disturbances following PTSD treatment in active duty military personnel. Psychol Trauma 2016:8(6):697–701. Doi: 10.1037/tra0000150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.American Psychological Association. Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in Adults; 2017. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/ptsd.pdf.

- 61.Department of Veteran Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD Clinical practice guidelines for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress reactions; 2017. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/.

- •62.Morgenthaier TI, Auerbach S, Casey KR, Kristo D, Maganti R, Ramar K, Zak R, et al. Position Paper for the Treatment of Nightmare Disorder in Adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Position Paper. J Clin Sleep Med 2018:14(6): 1041–55. Doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7178.This paper provides an update to the 2010 AASM treatment guidelines for the treatment of nightmares in adults. Recommendations were made for imagery rehearsal therapy and against the use of clonazepam and venlafaxine.

- 63.Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA Cooke M, Denberg TD. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: A clinical practice guidelines from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2016:165(2): 125–33. Doi: 10.7326/M15-2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morin CM. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep Med Clin 2006:1:375–86. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Trauer JM, Qian MY, Doyle JS, Rajarathnam SM, Cunnington D. Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2015:163(3): 191–204. Doi: 10.7326/M14-2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koffel EA, Koffel JB, Gehrman PR. A meta-analysis of group cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep Med Rev 2015:19:6–16. Doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Talbot LS, Maguen S. Metzler TJ, Schmitz M, McCaslin SE, Richards A et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Sleep 2014:37(2):327–41. Doi: 10.5665/sleep.3408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •68.Taylor DJ, Peterson AL, Pruiksma KE, Hale WJ, Young-McCaughan S., Wilkerson A, et al. Impact of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia disorder on sleep and comorbid symptoms in military personnel: A randomized clinical trial. Sleep 2018:41(6). Doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy069.This randomized controlled trial compared the efficacy of CBT-I to a Control condition and found that CBT-I was an effective treatment for insomnia and comorbid symptoms.

- 69.Kanady JC, Talbot LS, Maguen S, Straus LD, Richards A, Ruoff L, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia reduces fear of sleep in individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Sleep Med 2018:14(7): 1193–1203. Doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Germain A, Krakow B, Faucher B, Zadra A, Nielsen T, Hollifield M, et al. Increased mastery elements associated with imagery rehearsal treatment for nightmares in sexual assault survivors with PTSD. Dreaming 2004:14(4): 195–206. 10.1037/1053-0797.14.4.195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Krakow B, Kellner R, Pathak D, Lambert L. Imagery rehearsal treatment for chronic nightmares. Behav Res Ther 1995:33(7):837–43. Doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00009-m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hansen K, Hofling V, Kroner-Borowik T, Stangier U, Steil R. Efficacy of psychological interventions aiming to reduce chronic nightmares: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2013:33(1): 146–55. Doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Casement MD, Swanson LM. A meta-analysis of imagery rehearsal for post-trauma nightmares: effects on nightmare frequency, sleep quality, and posttraumatic stress. Clin Psychol Rev 2012:32(6):566–74. Doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cook JM, Harb GC, Gehrma PR, Cary MS, Gamble GM, Forbes D, et al. Imagery rehearsal for posttraumatic nightmares: A randomized controlled trial. J Trauma Stress 2010:23(5):553–63. Doi: 10.1002/jts.20569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Davis JL, Wright DC. Exposure, relaxation, and rescripting treatment for trauma-related nightmares. J Trauma Dissociation 2006:7(1):5–18. Doi: 10.1300/J229v07n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Davis JL, Rhudy JL, Pruiksma KE, Byrd P, Williams AE, McCabe KM et al. Physiological predictors of response to exposure, relaxation, and rescripting therapy for chronic nightmares in a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Sleep Med 2011:7(6):622–31. Doi: 10.5664/jcsm.1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rhudy JL, Davis JL, Williams AE, McCabe KM, Bartley EJ, Byrd PM et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for chronic nightmares in trauma-exposed persons: assessing physiological reactions to nightmare-related fear. J Clin Psychol 2010:66(4):365–82. Doi: 10.1002/jclp.20656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Long ME, Hammons ME, Davis JL, Frueh BC, Khan MM, Elhai JD, et al. Imgaery rescripting and exposure group treatment of posttraumatic nightmares in veterans with PTSD. J Anxiety Disord 2011:25(4):531–35. Doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Balliett NE, Davis JL, Miller KE. Efficacy of a brief treatment for nightmares and sleep disturbances for veterans. Psychol Trauma 2015:7(6):507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •80.Pruiksma KE, Taylor DJ, Mintz J, Nicholson KL, Rodgers M, Young-McCaughan S, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral treatment for trauma-related nightmares in active duty military personnel. J Clin Sleep Med 2020:16(1):29–40.This study compared the efficacy of ERRT for military personnel (ERRT-M) to minimal contact control (MCC) and found that ERRT-M showed medium effect size reductions in nightmares, and secondary symptoms, including insomnia, PTSD and depression.

- •81.Pruiksma K, Cranston C, Rhudy J, Micol R, Davis J. Randomized controlled trial to dismantle exposure, relaxation, and rescripting therapy (ERRT) for trauma-related nightmares. Psychol Trauma 2018:10(1):67–75. Doi: 10.1037/tra0000238.This randomized controlled trial compared a full protocol of ERRT with a modified version (i.e. excluding exposure and rescripting), and found that both groups exhibited significant improvements in nightmares, sleep quality, fear of sleep, PTSD and depression severity.

- 82.Germain A, Shear MK, Hall M, Buysse DJ. Effects of a brief behavioral treatment for PTSD-related sleep disturbances: A pilot study. Behav Res Ther 2007:45(3):627–32. Doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Margolies SO, Rybarczyk B, Vrana SR, Leszczyszyn DJ, Lynch J. Efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral treatment for insomnia and nightmares in Afghanistan and Iraq veterans with PTSD. J Clin Psychol 2013:69:1026–42. Doi: 10.1002/jclp.21970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Swanson LM, Favorite TK, Horin E, Arnedt JT. A combined group treatment for nightmares and insomnia in combat veterans: a pilot study. J Trauma Stress 2009:22(6):639–42. Doi: 10.1002/jts.20468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •85.Harb GC, Cook JM, Phelps AJ, Gehrman PR, Forbes D, Localio R, Harpaz-Rotem I, Gur RC, Ross RJ. Randomized controlled trial of imagery rehearsal for posttraumatic nightmares in combat veterans. J Clin Sleep Med 2019:15(5):757–67. Doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7770.This randomized controlled trial compared CBT-I to combined CBT-I+IRT in OEF/OIF veterans and found no additional benefit of IRT than those achieved with CBT-I alone.

- ••86.Belleville G, Dube-Frenette M, Rousseau A. Efficacy of imagery rehearsal therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy in sexual assault victims with posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J Trauma Stress 2018:31(4):591–601. Doi: 10.1002/jts.22306.This randomized controlled trail evaluated the efficacy of CBT for PTSD compared to CBT+IRT in sexual assault victims with PTSD, and found that IRT yielded greater improvement in nighttime symptoms, although CBT+IRT was not superior to CBT alone.

- 87.Rapoport DM. Methods to stabilize the upper airway using positive pressure. Sleep 1996:19(9 Suppl):S123–30. Doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.suppl_9.s123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Collen JF, Lettieri CJ, Hoffman M. The impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on CPAP adherence in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med 2012:8:667–72. Doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gharaibeh K, Tamanna S, Ujllah M, Geraci SA. The effect of continuous positive air pressure (CPAP) on nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). J Clin Sleep Med 2014:10(6):631–36. Doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Orr JE, Smales C, Alexander TH, Stepanowsky C, Pillar G, Malhotra A, et al. Treatment of OSA with CPAP is associated with improvement in PTSD symptoms among veterans. J Clin Sleep Med 2017:13(1):57–63. Doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.El-Solh AA, Vermont L, Homish GG, Kufel T. The effect of continuous positive airway pressure on post-traumatic stress disorder and obstructive sleep apnea: a prospective study. Sleep Med 2017:33:145–50. Doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jeffreys M, Capehart B, Friedman MJ. Pharmacotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: review with clinical applications. J Rehabil Res Dev 2012:49(5):703–15. Doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2011.09.0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Detweiler MB, Pagadala B, Candelario J, Boyle JS, Detweiler JG, Lutgens BW. Treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder nightmares at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center. J Clin Med 2016:5(12): 117 Doi: 10.3390/jcm5120117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bramoweth AD, Renqvist JG, Hanusa BH, Walker JD, Germain A, Atwood CW Jr. Identifying the demographic and mental health factors that influence insomnia treatment recommendations within a veteran population. Behav Sleep Med 2019:17:181–90. Doi: 10.1080/15402002.2017.1318752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dieperink ME, Drogemuller L. Zolpidem for insomnia related to PTSD. Psychiatr Serv 1999:50(3):421 Doi: 10.1176/ps.50.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pollack MH, Hoge EA, Worthington JJ, Moshier SJ, Wechsler RS, Brandes M, et al. Eszopiclone for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder and associated insomnia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(7):892–97. Doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05607gry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Saletu-Zyhlarz GM, Abu-Bakr MH, Anderer P, Gruber G, Mandl M, Strobl R, et al. Insomnia in depression: differences in objective and subjective sleep and awakening quality to normal controls and acute effects of trazodone. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26(2):249–60. Doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Aurora RN, Zak RS, Auerbach SH, Casey KR, Chowdhuri S, Karippot A, et al. Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. J Clin Sleep Med 2010:6(4):389–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Taylor FB, Martin P, Thompson C, Williams J, Mellman TA, Gross, et al. Prazosin effects on objective sleep measures and clinical symptoms in civilian trauma posttraumatic stress disorder: a placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2008:63(6):629–32. Doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, Hoff DJ, Hart K, Holmes H, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry 2013:170(9): 1003–10. Doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12081133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Khachatryan D, Groll D, Booij L, Sepehry AA, Schutz CG. Prazosin for treating sleep disturbances in adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2016:39:46–52. Doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Raskind MA, Chow PB, Harris C, Davis-Karim A, Holmes HA, Hart KL, et al. Trial of Prazosin for posttraumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med 2018:378(6):507–17. Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yucel D, van Emmerik A, Souama C, Lancee J. Comparative efficacy of imagery rehearsal therapy and prazosin in the treatment of trauma-related nightmares in adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev 2019:50:101248. Doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2019.101248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Forbes D, Phelps A, McHugh T. Treatment of combat- related nightmares using imagery rehearsal: A pilot study. J Trauma Stress 2001:14(2):433–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Germain A, Nielsen T. Impact of imagery rehearsal treatment on distressing dreams, psychological distress, and sleep parameters in nightmare patients. Behav Sleep Med 2003:1(3):140–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nappi CM, Drummond SP, Thorp SR, McQuaid JR. Effectiveness of imagery rehearsal therapy for the treatment of combat-related nightmares in veterans. Behav Ther 2010:41(2):237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Davis JL. Treating post-trauma nightmares: A cognitive behavioral approach. Springer Publishing Company, 2009. [Google Scholar]