Abstract

The coagulation cascade and immune system are intricately linked, highly regulated and respond cooperatively in response to injury and infection. Increasingly, evidence of hyper-coagulation has been associated with autoimmune disorders, including multiple sclerosis (MS). The pathophysiology of MS includes immune cell activation and recruitment to the central nervous system (CNS) where they degrade myelin sheaths, leaving neuronal axons exposed to damaging inflammatory mediators. Breakdown of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) facilitates the entry of peripheral immune cells. Evidence of thrombin activity has been identified within the CNS of MS patients and studies using animal models of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), suggest increased thrombin generation and activity may play a role in the pathogenesis of MS as well as inhibit remyelination processes. Thrombin is a serine protease capable of cleaving multiple substrates, including protease activated receptors (PARs), fibrinogen, and protein C. Cleavage of all three of these substrates represent pathways through which thrombin activity may exert immuno-regulatory effects and regulate permeability of the BBB during MS and EAE. In this review, we summarize evidence that thrombin activity directly, through PARs, and indirectly, through fibrin formation and activation of protein C influences neuro-immune responses associated with MS and EAE pathology.

Keywords: thrombin, multiple sclerosis, fibrin, activated protein C, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

Introduction

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease characterized by a dysregulated immune response targeting the central nervous system (CNS). It is a leading non-traumatic cause of disability in young adults, afflicting approximately one million people in the U.S., with women 2 to 3 times more likely to be affected (Culpepper et al. 2019; Nelson et al. 2019; Wallin et al. 2019). While the etiology of MS is still unknown, development of disease has been associated with both genetic and environmental factors (Hunter 2016). Currently, there is no cure for MS and treatment strategies aim to prevent symptoms and delay disease progression. At present, there are 15 FDA approved therapies for MS treatment, whose efficacy is attributed to their ability to modulate immune responses (Garg and Smith 2015; Vaughn et al. 2019). However, each of these disease-modifying therapies are not completely efficacious and can result in a range of major side-effects, causing patients to either change therapy or stop altogether (Garg and Smith 2015). Therefore, identification of novel disease mechanisms and therapeutic targets is necessary.

In response to inflammatory and infectious diseases and vascular injury, the coagulation and immune systems respond cooperatively to limit bleeding, clear invading pathogens, and initiate repair mechanisms. The interactions between these two systems have been highlighted in models of traumatic injury and wound healing as well as in sepsis (Baum and Arpey 2005; Laurens et al. 2006; Simmons and Pittet 2015). Increasingly, evidence suggests that coagulation processes may also be influencing pathology during autoimmune disorders, such as MS. While several coagulation factors have been linked to inflammatory processes, the initiation of the coagulation cascade ultimately results in the generation of thrombin, a serine protease, whose enzymatic activity has been found to be upregulated in plasma of relapsing remitting MS patients. Further, compared to healthy patients, they were found to exhibit significantly higher levels of prothrombin, the inactivated form of thrombin (Göbel et al. 2016a; Parsons et al. 2017). While increased thrombin generation and activity may put MS patients at a greater risk for developing a venous or arterial thrombus, work using the animal model of MS, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), suggests that thrombin activity may also contribute to MS pathology (Ahmed et al. 2019; Davalos et al. 2014; Peeters et al. 2014). Therefore, the development of thrombin-targeted therapies may be efficacious in treating MS.

In addition to influencing immune responses, thrombin activity has been implicated in regulating blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability during disease and myelination (Sweeney et al. 2018; Yoon et al. 2015), processes key to the progression and resolution of pathology during MS. Thrombin activity can influence these processes through the cleavage of a number of substrates, such as the cleavage of fibrinogen to fibrin and the activation of protein C (Feistritzer and Riewald 2005; Schuepbach et al. 2009; Sweeney et al. 2018). Moreover, thrombin may directly impact cellular function through the activation of protease activated receptors (PARs), which are expressed on cells in the immune system and throughout the CNS (Coughlin 2000; De Luca et al. 2017; Noorbakhsh et al. 2003). Here, we summarize evidence demonstrating thrombin generation and activity is not only dysregulated during MS and EAE, but may play a role in modulating immune activation and recruitment to the CNS, regulating blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, and have a direct effect on remyelination. Further, we will summarize evidence that a recombinant thrombin mutant, WE-thrombin, designed to exploit the immune-regulatory activities of thrombin while leaving blood clotting functions intact, may have therapeutic potential for treating MS.

MS Pathology

During MS, inflammatory demyelinating lesions form in the CNS resulting in neuronal dysfunction and disability. However, the presentation of MS pathology in patients is heterogeneous, making MS difficult to diagnose (Hunter 2016). The majority of MS patients present with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), characterized by periods of inflammatory demyelination, axon damage, and neuronal loss, followed by periods of remission in which inflammation subsides and remyelination occurs. Although remyelination of axons occurs following the resolution of inflammation at early stages of MS, remyelination often fails as the disease progresses (Patrikios et al. 2006; Wolswijk 1998). Importantly, to receive a diagnosis of RRMS, plaque formation must occur multiple times and affect different regions of the CNS, criteria designed to demonstrate a dissemination in time and space (Hunter 2016). Therefore, patients experiencing their first relapse and remission are diagnosed with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS). Over time, the rate and extent of plaque formation in RRMS patients increase, partly due to remyelination failure. As a result, disabilities become constant with no noticeable period of remission, leading to secondary progressive MS (SPMS). A smaller subset of patients initially develop a progressive disease course and are diagnosed with primary progressive MS (PPMS). Diagnosis of MS is dependent on the identification of clinical symptoms, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to identify plaques, the identification of biomarkers in the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), and ruling out differential diagnoses (Hunter 2016).

The inflammatory melee driving pathology and plaque development during MS and EAE is comprised of multiple cell types from the adaptive and innate branches of the immune system. Historically, MS has been viewed as a T-cell mediated disease. Indeed, MS is characterized by a Th1/Th17 response with a deficient regulatory T cell (Treg) response (Van Kaer et al. 2019). However, B cells are also active players during autoimmunity and therapeutics targeting B cells, such as B cell depletion via anti-CD20 antibodies, have been efficacious (Bar-Or et al. 2008; Hauser et al. 2008; Li et al. 2018; Sorensen et al. 2014). Increasingly, the role of the innate immune system in the initiation and progression of MS and EAE has been appreciated. Macrophages, microglia, and dendritic cells function as antigen presenting cells and release cytokines supporting the differentiation and activation of T cells. Macrophages and microglia exhibit diverse functions and phenotypes based on environmental cues (Funes et al. 2018; Tay et al. 2017). Pro-inflammatory macrophages and microglia phagocytose myelin debris and release chemical mediators, such as myeloperoxidases and reactive oxygen species (ROS), which damage exposed axons (Choi et al. 2005; Funes et al. 2018; Lee et al. 2017). Importantly, macrophages and microglia can also release anti-inflammatory cytokines and growth factors that promote resolution of inflammation and initiate repair mechanisms in the CNS (Hu et al. 2015). Therapeutic strategies that promote anti-inflammatory phenotypes and functions from macrophages and microglia may be beneficial in treating active MS pathology (Gandhi et al. 2010).

Thrombin Generation During MS and EAE

In response to vascular injury or inflammation, activation of the extrinsic and contact pathways of coagulation converges to form activated factor X (FXa), a serine protease that cleaves prothrombin to form thrombin (reviewed in (Puy et al. 2016)). The extrinsic pathway is initiated in response to exposure of blood to tissue factor (TF), which rapidly forms a complex with circulating FVII; this complex in turn catalyzes the conversion of FX to FXa. TF is predominantly expressed on cells in the extravascular space or by select populations of activated blood cells including monocytes and endothelial cells. Relevant to the activation of thrombin during neuroinflammation, TF is expressed within the CNS of humans and rodents, where it is predominantly expressed by astrocytes and perivascular cells (Drake et al. 1989; Eddleston et al. 1993). Activation of the coagulation factor XII has also been associated with neuroinflammation, as evidenced by a reduction in EAE induced inflammation observed in FXII-deficient mice. However, FXII deficiency during EAE did not result in a reduction in fibrinogen/fibrin in the CNS suggesting that FXII may mediate pathology during EAE in a thrombin-independent manner (Göbel et al. 2016b). Increased BBB permeability associated with neuroinflammation would allow for FVII and other coagulation factors including FXII to interact with the cellular and extracellular constituents of the CNS, altogether culminating to potentiate thrombin generation.

Thrombin Activity During MS and EAE

Altered expression and activity of coagulation factors have been found in MS patients, which may contribute to a hypercoagulable phenotype (Göbel et al. 2016a; Han et al. 2008; Parsons et al. 2017). Indeed, MS patients are at increased risk of venous and arterial thrombosis, an effect attributed to reduced mobility, but potentially compounded by increased activation of the coagulation pathway (Ahmed et al. 2019; Koudriavtseva 2014; Peeters et al. 2014). Increased prothrombin and factor X (FX) activity have been reported in the circulation of RRMS and SPMS, but not PPMS patients compared with healthy controls. In RRMS patients, prothrombin levels negatively correlated with relapse-free time (Göbel et al. 2016a). An ex vivo coagulation assay performed with platelet-poor-plasma showed that compared to healthy controls and SPMS patients, RRMS patients exhibit greater thrombin generation that corresponds with disease duration (Parsons et al. 2017). Within the CNS, post-mortem analysis of MS patient brain tissue revealed that TF expression is associated with plaques, suggesting increased activation of the coagulation pathway within the CNS (Han et al. 2008). Fibrinogen and fibrin deposition is found in both active and chronic plaques as well as pre-active plaques; characterized by microglia activation and intact myelin tracts (Marik et al. 2007; Vos et al. 2005). Some suggested that thrombomodulin (TM), which facilitates thrombin-mediated activation of protein C, is dysregulated during MS (Festoff et al. 2012; Frigerio et al. 1998). Dysregulation of the thrombin-TM axis is further supported by the increased levels of protein C inhibitor found in MS plaques (Han et al. 2008).

In EAE, elevated thrombin activity occurs early in disease and increases with disease progression. Moreover, thrombin activity positively correlates with fibrin deposits, microglia activation, demyelination and axonal damage, and clinical severity during EAE (Davalos et al. 2014). Interestingly, protein nexin-1 (PN-1) and antithrombin III (ATIII), inhibitors of thrombin activity, are also elevated in the CNS during EAE (Beilin et al. 2005). In a rat model of EAE, thrombin-antithrombin complexes were shown to increase in plasma with disease development (Inaba et al. 2001). Administration of exogenous anticoagulant agents, such as heparin or warfarin, to EAE animals further reduced thrombin activation and improved clinical scores, while direct inhibition of thrombin activity through the administration of hirudin similarly reduced clinical scores and markers of peripheral inflammation (Han et al. 2008; Lider et al. 1989; Stolz et al. 2017).

Thrombin Activity & The Innate Immune System

Fibrin is the result of thrombin-mediated conversion of fibrinogen. The presence of fibrin in MS CNS lesions is histopathological evidence of thrombin activity and implicates thrombin activity in the pathogenesis of MS and EAE (Gay et al. 1997; Marik et al. 2007; Wakefield et al. 1994). Fibrin depositions can also be found in the joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and thrombin inhibition in experimental models of autoimmune arthritis ameliorates disease severity suggesting that thrombin activity may also contribute to other autoimmune disorders (Lee and Weinblatt 2001; Marty et al. 2001; Varisco et al. 2000). In addition to improving clinical scores in EAE, inhibition of thrombin activity with hirudin decreases pro-inflammatory cytokines in the spleen and lymph nodes (Han et al. 2008). These effects may be mediated directly through the activation of PARs by thrombin or indirectly by either modulating the cleavage of fibrinogen to fibrin or through activation of protein C. In the following section, we will summarize evidence that thrombin activity may modulate innate and acquired immune responses and mediate recruitment of immune cells to the inflamed CNS.

As mentioned above, thrombin directly affects cell function through the activation of PARs (Coughlin 2000). PARs are integral membrane proteins that are activated through the cleavage of the N-terminal region to reveal an active region that acts as a tethered ligand. PARs are coupled to G proteins and the binding of the newly exposed terminal acid sequence to the extracellular loop 2 region results in an intracellular signaling cascade capable of altering cellular function. The PAR family is composed of four members, PAR1–4, with thrombin having well characterized effects mediated via cleavage of PARs 1, 3, and 4. Notably, other proteases such as trypsin, plasmin, cathepsin G, FVIIa, and FXa are capable of activating PAR (Chu 2011; Coughlin 2000; Rigg et al. 2019).

The presence of thrombin in the CNS has been shown to activate microglia without the existence of an underlying pathology. Injection of thrombin into the hippocampus of otherwise healthy rats results in microglia activation, increases in pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, and the release of ROS (Choi et al. 2005). Increased ROS associated with thrombin ultimately leads to axonal damage and neuronal death (Choi et al. 2005; Lee et al. 2005). While these pro-inflammatory effects in vivo may in part be mediated by the activation of multiple cell types and signaling pathways, in vitro stimulation of microglia with thrombin produces a similar inflammatory pattern through activation of the JAK2-STAT3 pathway, suggesting thrombin directly promotes microglia activation (Huang et al. 2008; Möller et al. 2000; Ryu et al. 2000). While multiple groups have reported the pro-inflammatory responses of microglia to thrombin, there is controversy in the literature as to whether or not PAR receptors mediate this response (Ryu et al. 2000; Suo et al. 2002; Suo et al. 2003).

In the periphery, PAR1 is expressed by human and rodent monocytes and macrophages, and its activation by thrombin induces both pro- and anti-inflammatory responses and promotes chemotaxis. Some studies have reported thrombin stimulation inducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, while others demonstrate thrombin-induced secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, in a dose-dependent manner as well as transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) (Lin et al. 2015; López-Zambrano et al. 2020; Naldini et al. 2005; Szaba and Smiley 2002). Notably, TGF-β has been shown to have protective effects in the pathogenesis of EAE (Lee et al. 2017). Activation of PAR1 by thrombin induces chemotaxis in human monocytes through the reorganization of the F-actin skeleton (Gadepalli et al. 2013; Lin et al. 2015). Interestingly, in a transwell assay, thrombin stimulation enhanced migration of the macrophage cell line RAW264.7 towards conditioned media from ‘injured’ endothelial cells (ECs), suggesting thrombin signaling may enhance chemotactic responses to other stimuli (Lin et al. 2015). The release of chemokines by ECs following PAR1 activation contributes to recruitment of immune cells to sites of inflammation. Moreover, PAR1 activation enhances the expression of adhesion molecules, such as intercellular cell adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 and P-selectin on ECs, providing a mechanism through which leukocytes may adhere to the endothelial surface (Kaplan et al. 2015; Sugama et al. 1992). Overall, these studies suggest that thrombin activation of PARs on either immune cells or ECs, promotes the activation and recruitment of immune cells to sites of inflammation.

Through its function as a serine protease, thrombin may directly influence immune function during EAE through the cleavage of osteopontin (OPN), a signaling molecule with pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine functions (Boggio et al. 2016; Lund et al. 2009). OPN interacts with both adaptive and innate immune cells promoting survival, cytokine secretion, and migration (reviewed by (Lund et al. 2009)). Importantly, cleavage of OPN by thrombin increases its pathological effects on EAE pathology. In a mouse model of progressive EAE, injection of OPN and OPN fragments generated by thrombin cleavage during progressive stages of disease results in a relapse that is characterized by increased disease score. Conversely, injection of an OPN mutant that lacks a thrombin cleavage site did not alter disease severity compared to control animals (Boggio et al. 2016). Recently, it has been shown that thrombin also cleaves pro-interleukin (IL)-1α to its active form, IL-1α, connecting thrombin activity directly to the activation of the innate immune system (Burzynski et al. 2019).

In addition to cleaving and activating PARs, thrombin cleaves fibrinogen to its soluble monomer, fibrin. Fibrin polymerizes to form an extracellular matrix that participates in the recruitment and activation of immune cells at sites of inflammation (Szaba and Smiley 2002). Within its structure, fibrinogen contains multiple binding sites that mediate interactions with leukocytes and ECs, including the peptide Y377–395 site, which binds to CD11b/CD18 on leukocytes. The peptide Y377–395 region of fibrinogen is only accessible to binding by CD11b/CD18 following cleavage of fibrinogen to fibrin, suggesting thrombin activity is necessary to mediate these interactions (Ugarova et al. 2003). Fibrin is also able to bind to CD11c/CD18 on leukocytes as well as ICAM-1 on the epithelium surface (Languino et al. 1995; Languino et al. 1993; Loike et al. 1991; Nham 1999). These interactions mediate the activation of leukocytes and the recruitment and adhesion of circulating immune cells to sites of inflammation (McCarty et al. 2003).

The presence of fibrin in the CNS is associated with disrupted neuronal function, ROS production, and microglia clustering and activation (Davalos et al. 2012). In EAE, fibrin deposition in the CNS is associated with disability (Koh et al. 1992; Paterson 1976). Genetic or pharmacological depletion of fibrin reduces disease scores in EAE rodents (Adams et al. 2007; Akassoglou et al. 2004; Yang et al. 2011). Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) mediate fibrin degradation and removal through generation of plasmin. In mice that lack either tPA (tPA−/−) or uPA (uPA−/−), fibrin degradation is impaired and the EAE disease course is more severe compared to WT mice, underscoring the detrimental effects of fibrin on EAE pathology (Lu et al. 2002). Injection of fibrinogen into the CNS of naive mice results in increased microglia activation (Ryu et al. 2015). These pathological effects of fibrin and fibrinogen may be in part driven by interaction with the CD11b adhesion molecule. Genetic ablation of the peptide Y377–395 binding site in Fggy390−396A mice and competitively inhibiting CD11b/CD18 binding with 5B8, an antibody specific to peptide Y377–395, decreases disease severity, demyelination, microglia activation, and the infiltration of peripheral leukocytes into the spinal cord during EAE (Adams et al. 2007; Davalos et al. 2012; Ryu et al. 2018).

Increases in circulating fibrinogen is an indicator of inflammation (Davalos and Akassoglou 2012). Indeed, stimulation of macrophages and monocytes with fibrinogen in vitro has been reported to elicit both pro- and anti-inflammatory responses (Akassoglou et al. 2004; Davalos and Akassoglou 2012; Hsieh et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2010). In one study, stimulation of macrophages with fibrinogen induced the secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), while fibrin stimulation induced the secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 (Hsieh et al. 2017). Moreover, it was shown that fibrin prevented pro-inflammatory macrophage responses in the presence of fibrinogen, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and IFNγ (Hsieh et al. 2017). In contrast, in vitro stimulation of primary microglia fibrin increased gene expression in pathways associated with immune responses, including the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (Ryu et al. 2015). Similarly, fibrinogen elicits microglia activation in a CD11b/Cd18 dependent manner vivo and in vitro (Adams et al. 2007). Together, these data demonstrate that fibrinogen as well as fibrin contribute to macrophage and microglia activation.

Fibrinogen and fibrin may promote recruitment and adhesion of peripheral immune cells to the inflamed CNS. Analysis of white matter tissue following fibrinogen injection shows increases in gene expression associated with leukocyte chemotaxis (Ryu et al. 2015). Indeed, fibrinogen injection into the CNS results in the infiltration of peripheral macrophages and T cells in naïve and 2D2 mice, a T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic model with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein specific T cells (Flick et al. 2004). Increased levels of circulating fibrinogen are associated with increased ICAM-1 expression on cerebral vascular cells (Flick et al. 2004). In turn, binding of ICAM-1 by fibrinogen mediates the attachment of leukocytes to the EC surface and promotes the migration of leukocytes across endothelial barriers (Duperray et al. 1997).

TM-bound thrombin is able to activate endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR)-bound protein C to generate activated protein C (aPC), a serine protease capable of activating the same PARs as thrombin (Griffin et al. 2015; Stearns-Kurosawa et al. 1996). However, aPC-mediated cleavage of PARs results in the activation of different cellular responses compared to thrombin (Mosnier et al. 2012). This biased agonism has profound implications in inflammation, with thrombin acting as an inflammatory inducer and amplifier, whereas aPC promotes anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective effects (Heuberger and Schuepbach 2019). In addition to mediating anticoagulant effects and inhibiting thrombin generation, aPC promotes anti-inflammatory effects in vivo. There exists a growing body of literature on the anti-inflammatory effects of aPC on autoimmune disorders such as inflammatory bowel disorder and rheumatoid arthritis, while a role for aPC in attenuating neuroinflammation and activating neuroprotective mechanisms has been appreciated (Danese et al. 2010; Houston and Cuthbertson 2009).

In MS patients, the PC axis has been recently shown to be dysregulated, with plasma levels of PC associated with poor prognosis (Ziliotto et al. 2020). Intriguingly, the efficacy of inhibiting endogenous aPC during EAE has mixed results. While one study found inhibiting aPC generation exacerbates disease severity and increases demyelination, another has reported that inhibiting endogenous aPC reduces clinical scores while inducing myeloid-derived suppressor cells (Alabanza et al. 2013; Wolter et al. 2016). However, treatment with exogenous aPC reduces clinical scores, demyelination, microglia activation, and the recruitment of peripheral myeloid cells during EAE (Han et al. 2008; Kant et al. 2020; Wolter et al. 2016). In the periphery, exogenous aPC treatments reduce the number of inflammatory foci in the spleen and proliferation in the spleen and lymph nodes of EAE animals. aPC treatments also reduce the expression of both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the lymph nodes and splenocytes of EAE mice (Suo et al. 2002). Potential paths forward for translation of aPC for use in MS include development of mutant forms of aPC whereby the anticoagulant activity is lost while the cytoprotective functions of aPC are preserved (Griffin et al. 2018). This biased agonist approach has shown promise in models and clinical trials of stroke and EAE (Kant et al. 2020; Lyden et al. 2019; Sinha et al. 2018).

Studies using mouse models of endotoxemia have demonstrated the ability of exogenous aPC to reduce infiltration of leukocytes to inflamed tissues (Alabanza and Bynoe 2012; Bartha et al. 2000). aPC may also reduce leukocyte accumulation at areas of inflammation by decreasing chemotaxis in immune cells (Healy et al. 2018). aPC treatment has been shown to reduce chemotaxis of human neutrophils in an EPCR-dependent manner and to reduce release of chemokines, such as MCP-1 and macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), by macrophages (Brueckmann et al. 2004; Sturn et al. 2003). Moreover, aPC has been shown to inhibit neutrophil extracellular trap formation in an EPCR-, PAR3-, and Mac-1-dependent manner (Healy et al. 2017). Overall, the abovementioned studies suggest a protective role for aPC in inflammation by inhibiting immune cell infiltration and chemokine secretion. Therefore, targeting the aPC axis may be a feasible therapeutic target in neuroinflammatory diseases such as MS.

Thrombin Activity & The Adaptive Immune System

In addition to responding rapidly to infection and injury, the innate immune system plays an essential role in the recruitment and activation of lymphocytes. Dendritic cells, and to a lesser extent macrophages, act as antigen processing cells and are capable of inducing proliferation and activation of T cells through engagement of the TCR and the release of cytokines (Iezzi et al. 1999). In dendritic cells, thrombin increases antigen presenting functions as well as the release of IL-12, a cytokine supporting the differentiation and maintenance of Th1 responses (Yanagita et al. 2007). Pre-treatment of dendritic cells with thrombin significantly increases T cell proliferation and IFNγ production in a co-culture system (Yanagita et al. 2007).

Thrombin may directly affect lymphocyte function through the activation of PARs on T and B cells (Hurley et al. 2013; López et al. 2014; Mari et al. 1994). In vitro, thrombin enhances T cell proliferation in response to TCR engagement and increases secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines in a PAR1-dependant manner (Hurley et al. 2013). Thrombin increases TCR-induced release of IFNγ in CD8+ T cells and increases T cell mobility (Hurley et al. 2013; Mari et al. 1994). Conversely, the expression and function of PARs in B lymphocytes has not been extensively studied. While some studies have shown that PARs are not expressed in this cell type, others have reported gene and protein expression of PAR1 and PAR3 in murine B lymphocytes (Kalashnyk et al. 2013; López et al. 2014). In vitro studies using human B lymphoma cell lines show that activation of PAR1 and PAR3 decreases survival and proliferation (Kalashnyk et al. 2013; López et al. 2014). Taken together, it is unclear what specific role, if any, thrombin and PARs play in B cell-mediated lymphocyte functions.

A limited number of studies have demonstrated a role for fibrin or fibrinogen in supporting T cell responses in vivo (Luo et al. 2013). Fibrin induces a phenotype in macrophages suggestive of increased antigen processing, presentation, and subsequent activation of T cells. When co-cultured with T cells, bone-marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) that have been pretreated with fibrin induce the differentiation of T cells to an IFNγ expressing Th1 phenotype more effectively than non-treated BMDMs. In vivo, the Th1 transcription factor, t-bet, is also increased in the CNS following fibrinogen injection (Ryu et al. 2015). Conversely, one study reported that the C-terminal region of fibrinogen was shown to bind to activated T cells, reducing cytokine expression (Takada et al. 2010). These data suggest that the cleavage of fibrinogen by thrombin may generate multiple protein fragments with distinct biological activity.

aPC promotes the expansion of regulatory T cells while inhibiting pathogenic T cell responses. In a mixed lymphocyte reaction assay, incubation of human T cells with antigen presenting cells induced T cell proliferation, which was attenuated in the presence of aPC. Moreover, incubation with aPC favored the expansion of Tregs over Th1 and Th17 helper T cells (Ranjan et al. 2017). aPC may also indirectly limit T cell activation by inhibiting the expansion of dendritic cells, however conflicting reports on the ability of aPC to modulate antigen presentation on dendritic cells exist (Matsumoto et al. 2015; Ohkuma et al. 2015). In vivo, the ability of aPC to promote Treg over Th1 responses has been demonstrated in mouse models of graft versus host disease and type 1 diabetes (Ranjan et al. 2017; Xue et al. 2012). While these data support the hypothesis that aPC may be successful in treating T cell mediated autoimmune disorders, additional research in is necessary to elucidate the effects of aPC on the adaptive immune system in MS and EAE.

Thrombin & Platelets in MS

In addition to their classical hemostatic function, platelets are widely recognized as key players in the regulation of the inflammatory response, as well as modulation of both the innate and adaptive immune system (reviewed in (Koupenova et al. 2018)). In MS patients, platelets are hyperactivated compared to healthy individuals and are more responsive to physiological agonists, including thrombin (Morel et al. 2015; Sheremata et al. 2008). Human platelets express PAR1 and PAR4, and cleavage by thrombin triggers platelet activation and homeostatic functions (Kahn et al. 1999). More recently, relevant roles for platelet PARs in inflammation have been elucidated. An elegant report by Kaplan and colleagues highlighted that thrombin-mediated platelet PAR4 activation promotes leukocyte intravascular trafficking independent of endothelial activation, which may be relevant in neuroinflammatory disorders (Kaplan et al. 2015). The potential deleterious role of platelets in MS was addressed by Langer and colleagues, who showed that platelets are present in human MS lesions and contribute to inflammation in the CNS. More importantly, platelet depletion decreased immune cell recruitment and disease score in their EAE model (Langer et al. 2012). Moreover, thrombin-derived products, such as fibrin and aPC may also be involved in shaping platelet activation in MS. Platelets bound to fibrin release growth factors, such as TGF-β, which can modulate macrophage activation such as inhibiting inflammatory signaling triggered by LPS (Nasirzade et al. 2020). Further, platelet interactions with fibrin suppresses recruitment of anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells in vivo and in vitro through the expression of soluble CD40 ligand (Panek et al. 2019). aPC can also modulate platelet activation via GPIbα (White et al. 2008). All together, these studies point to a potential role for thrombin and thrombin-derived products in modulating platelet function via PARs or other receptors in MS. Further research to better understand the role that the thrombin-platelet axis plays in neuroinflammatory diseases such as MS is warranted.

Thrombin & The Blood Brain Barrier

The blood brain barrier is composed of ECs whose barrier functions are supported by pericytes, astrocytes, neurons, and an extracellular matrix, that collectively are referred to as the neurovascular unit. During homeostasis, peripheral cells and large molecules are excluded from the CNS. MS and EAE are characterized by a remodeling of the neurovascular unit resulting in increased BBB permeability, such that blood components like fibrinogen and thrombin, as well as whole cells, such as macrophages, dendritic cells, and T cells, are able to enter the parenchyma where they contribute to the formation of inflammatory, demyelinated lesions. Permeability is regulated by the expression and function of adherens, gap junction, and tight junction proteins, which are expressed on ECs and mediate cell-to-cell interactions (Rodrigues and Granger 2015). Activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), which enzymatically degrade extracellular matrix as well as other proteins and induce changes in cytoskeleton also affect permeability (Rodrigues and Granger 2015).

PAR1–4 are expressed on the cerebral vascular ECs in rodents and humans, allowing thrombin to directly influence endothelial barrier function in the CNS (Bartha et al. 2000; Kim et al. 2004). Inhibition of PAR1 during EAE improves BBB integrity by downregulating MMP9 and attenuating occludin and ZO-1 loss, ultimately reducing markers of neuroinflammation and disease severity (Brailoiu et al. 2017). In vitro, thrombin increases permeability of human and rodent cerebrovascular cells through the reorganization of F-actin and increased MMP2 secretion (Alabanza and Bynoe 2012; Festoff et al. 2016; Guan et al. 2004). Thrombin may indirectly alter EC barrier function by activating pericytes within the neurovascular unit. Pericytes in particular express high levels of PARs and are the main producer of MMP9 in the neurovascular unit following thrombin stimulation (Machida et al. 2015). Thrombin’s protease function has also been shown to activate MMP9 from its precursor, proMMP9 (Machida et al. 2015). Co-cultures of thrombin-treated rodent pericytes and ECs lead to an increase in permeability, accompanied with a decreased expression and cellular arrangement of tight junction proteins and increased production of MMP9 (Machida et al. 2017a; Machida et al. 2017b).

Fibrinogen and fibrin are used as markers of increased BBB permeability; however, they may also play a role in modulating barrier function. Treatment of endothelial monolayers with fibrinogen increases permeability to albumin in vitro. This effect is mediated through the remodeling of F-actin, decreases in gene and protein expression of tight junction proteins, and internalization of VE-Cadherin (Muradashvili et al. 2012; Muradashvili et al. 2011; Patibandla et al. 2009; Tyagi et al. 2008). Conversely, aPC improves barrier function in a PAR1-dependent manner and has been shown to reverse thrombin-induced barrier dysfunction (Feistritzer and Riewald 2005; Schuepbach et al. 2009). During EAE, exogenous aPC increases the integrity of the BBB by attenuating the loss of endothelial tight junction proteins and the production of MMP9, inhibiting the translocation of fibrinogen/fibrin and peripheral CD45+ cells into the CNS (Kant et al. 2020).

Thrombin & Myelination

A major underlying cause of remyelination failure in MS is the inhibition of oligodendrocyte progenitor cell (OPC) maturation due to signals in the plaque microenvironment that prevent OPCs from becoming myelin-forming oligodendrocytes (Chang et al. 2000; Chang et al. 2002; Maeda et al. 2001; Scolding et al. 1998; Wolswijk 1998). Indeed, multiple signals have been implicated in blocking the maturation of OPCs that are recruited to demyelinating lesions (Kotter et al. 2011; Kremer et al. 2011). Interestingly growing evidence suggests that thrombin may be among these signals. The PAR1 thrombin receptor is expressed by OPCs and thrombin can block OPC maturation in a PAR1-dependent manner (Burda et al. 2013; Choi et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2004; Yoon et al. 2015). Furthermore, selective Par1 gene deletion results in earlier onset of spinal cord myelination and treatment of OPCs with a PAR1 inhibitor enhanced OPC maturation into oligodendrocytes (Burda et al. 2013; Yoon et al. 2015). More recently, Yoon and co-workers (2020) found that loss of PAR1 function increases the numbers of OPCs in two rodent models of demyelination and promotes OPC differentiation towards mature oligodendrocytes that remyelinate demyelinated axons. This study also found that PAR1 loss influenced remyelination through an astrocyte-dependent mechanism. These studies support the notion that manipulating thrombin in MS can influence both disease progression, by influencing inflammatory processes and BBB permeability, but also by promoting OPC maturation and remyelination.

Thrombin & Therapeutic Strategies

Historically, the anticoagulant heparin has been used to treat MS patients with mixed success (Courville 1959; Maschmeyer et al. 1961). However, treatment with traditional anticoagulants poses additional risks such as increased bleeding, making them undesirable as a long-term treatment strategy. Therapeutic strategies that target both inflammation and fibrin formation without impairing hemostasis may address this need. The therapeutic enzyme WE-thrombin is similar, but not identical to native thrombin, with point mutations at Trp215Ala and Glu217Ala (WE) that virtually eliminate prothrombotic activity towards fibrinogen and PAR1 (~20,000-fold and 1,000-fold, respectively) (Cantwell and Di Cera 2000). Importantly, these mutations spare enzymatic activity towards protein C in the presence of the cofactor TM, and when administered to experimental animals and humans, WE-thrombin generates endogenous aPC. While exogenous aPC infusion has potential to treat neuroinflammation, it has the potential to exacerbate bleeding due to systemic anticoagulant effects on the coagulation system. By comparison, thrombin-mediated activation of endogenous aPC is localized to the intravascular surface, where protein C is located, bound to EPCR (Feistritzer et al. 2006). By generating aPC on intravascular surfaces, WE-thrombin exerts antithrombotic, anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective effects in experimental models of disease (Berny-Lang et al. 2011; Vicente et al. 2012). In non-human primate models of thrombosis, WE-thrombin has been shown to have potent antithrombotic effects without impairing hemostasis (Berny et al. 2008; Gruber et al. 2002; Gruber et al. 2006; Tucker et al. 2020). In human subjects, WE-thrombin showed a favorable safety profile in a phase 1 trial and is currently under investigation in a phase 2 study for safely preventing thrombosis during hemodialysis in patients with end-stage renal disease (Tucker et al. 2020).

In animal models of autoimmune disease, such as arthritis and EAE, WE-thrombin reduces markers of pathology. In an arthritis model, WE-thrombin-associated reductions in disease scores were accompanied by decreases in immune cell infiltration and edema (Flick et al. 2011). In a model of EAE in which WE-thrombin treatments began following the onset of clinical symptoms, WE-thrombin significantly reduced clinical scores while reducing axonal damage, demyelination and fibrin deposition in the spinal cord (Verbout et al. 2015). In this model, WE-thrombin also attenuated peripheral inflammation, evidenced by reduced numbers of TNF+CD11b+ and ICAM-1+CD11b+ cells in the spleen (Verbout et al. 2015). These studies suggest that WE-thrombin may inhibit immune trafficking to sites of inflammation and improve barrier function during autoimmune disease. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms through which WE-thrombin affects disease course during EAE.

Conclusion

In conclusion, thrombin activity, which is elevated during MS, is capable of influencing immune function and CNS processes through PAR activation as well as fibrin and aPC generation, as summarized in Figures 1 and 2. Inhibition of thrombin and fibrin formation and treatment with exogenous aPC in animal models of MS decrease disease severity while reducing neuroinflammation, BBB permeability, and demyelination. The ability for thrombin, fibrin, and aPC to influence immune responses, EC barrier permeability, and myelination processes has been established in vitro as well as in other disease models, further supporting a direct role thrombin in MS pathology. Due to the numerous substrates through which thrombin may signal, thrombin activity may result in both adverse as well as protective effects. Indeed, activation of protein C has been shown to be protective in EAE, suggesting treatment strategies designed to increase aPC signaling may be advantageous in the treatment of MS. While additional research is necessary to elucidate the mechanisms and the extent to which thrombin contributes to MS and EAE development and progression, targeting thrombin activity and the protein C axis appears to be an auspicious therapeutic strategy.

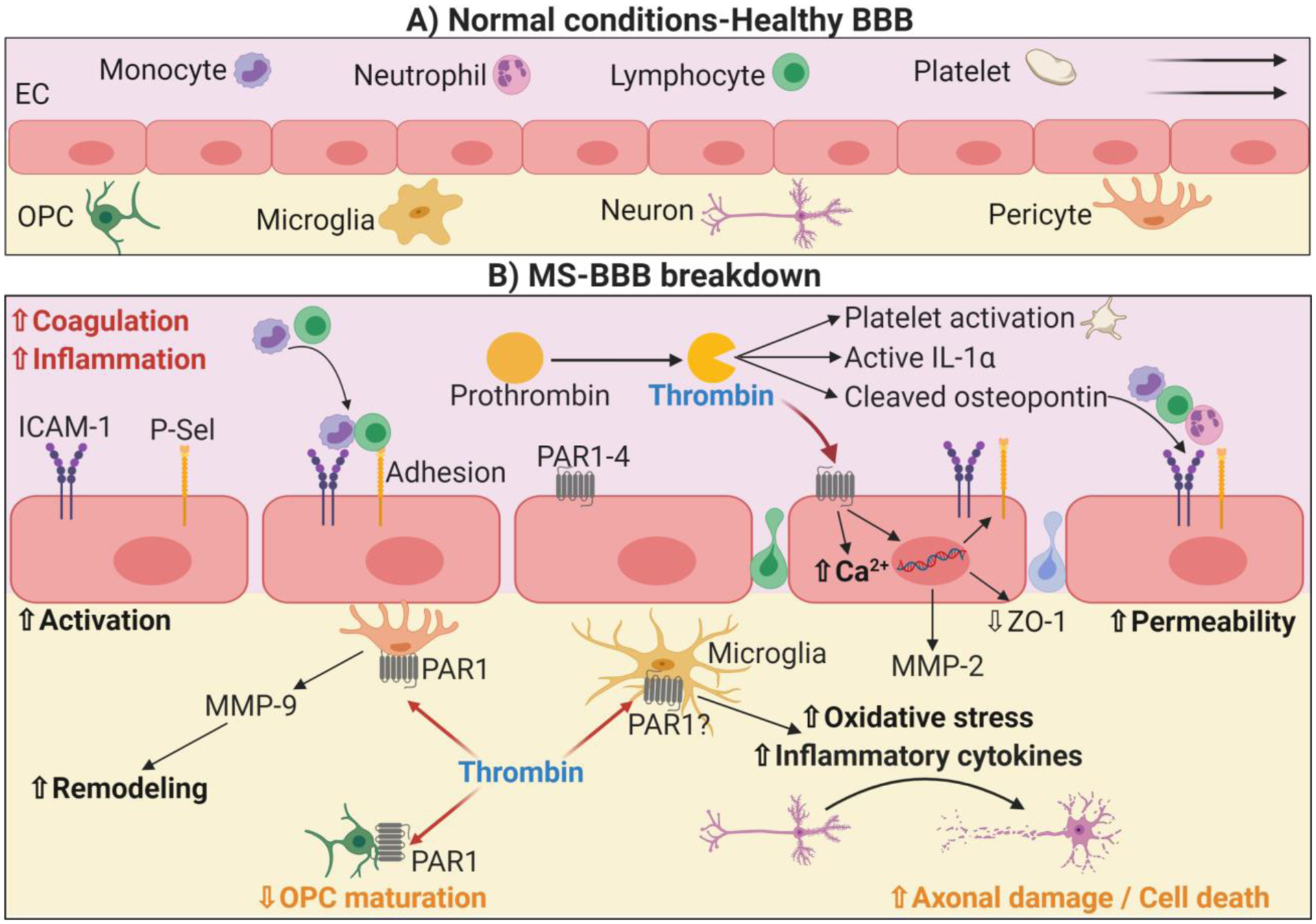

Figure 1-.

Thrombin-mediated regulation of inflammation and the immune response in multiple sclerosis and blood brain barrier breakdown. During MS, increased inflammation and coagulation leads to the cleavage of prothrombin into thrombin, which exerts subsequent effects in several circulating or resident cells. Platelets from MS patients are more sensitive to thrombin activation, and platelet activation has been shown to exert harmful effects in MS. Thrombin can also cleave osteopontin, which promotes subsequent inflammation and recruitment of T-cells. In addition, thrombin signals in ECs via PAR, which promotes calcium mobilization, adhesion molecule exposure on the surface and loss of cell-to-cell connections, such as ZO-1. Altogether, this allows an increased permeability and disruption of the BBB. Thrombin can then infiltrate into the CNS, where it triggers MMP-9 release from pericytes, contributing to permeability and remodeling. Finally, thrombin can also activate microglia, triggering the secretion of reactive oxygen species as well as of inflammatory cytokines, which promotes axonal damage and neuron death contributing to MS development.

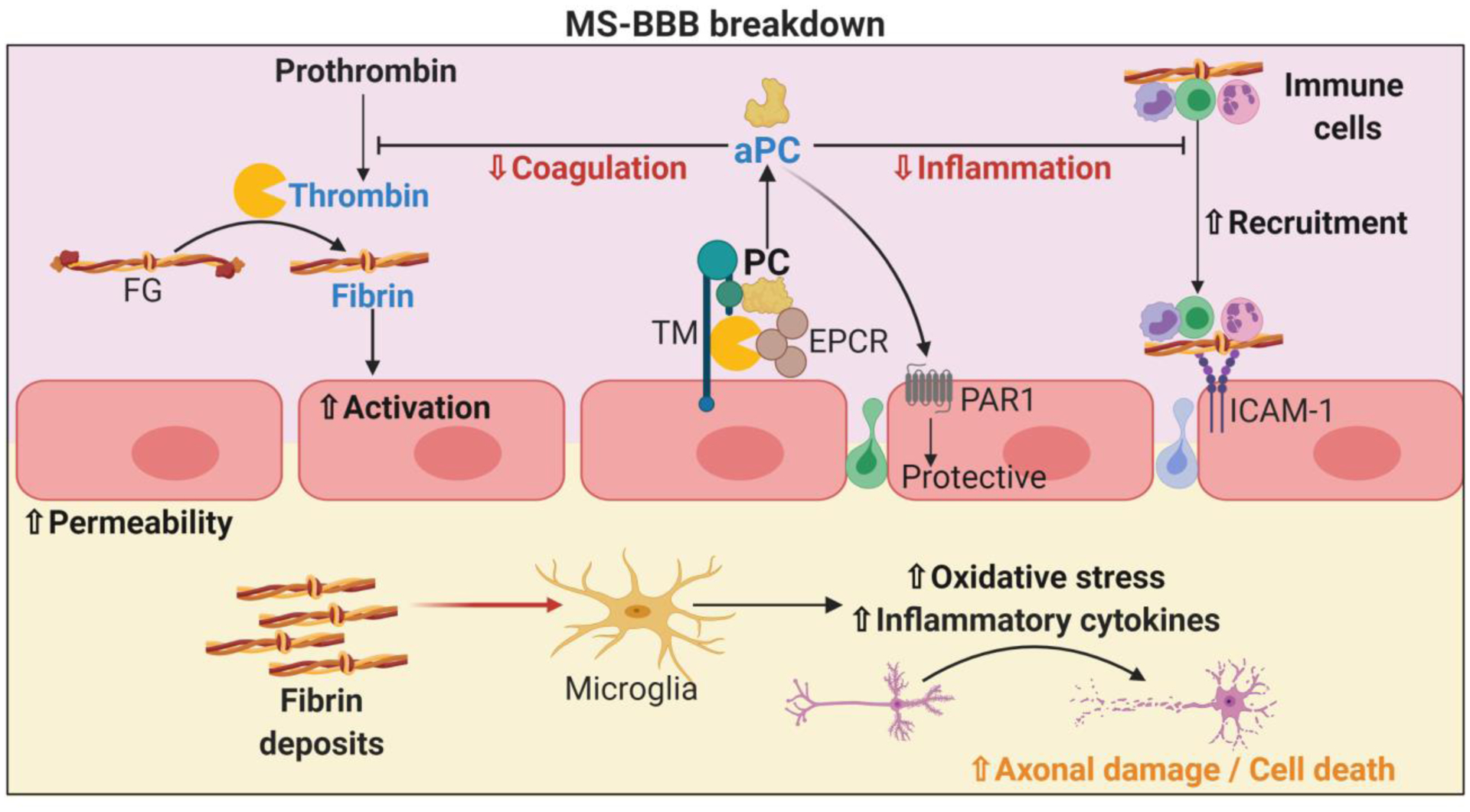

Figure 2-.

Thrombin indirect regulation of inflammation and the immune response in multiple sclerosis and blood brain barrier breakdown. Thrombin can form a complex with thrombomodulin (TM) and EPCR to promote the activation of protein C. aPC is well known to exert overall protective effects via reduction thrombosis by blocking thrombin formation as well as reducing immune cell infiltration. aPC also triggers protective effects in ECs via PAR1, contributing to BBB stability. Thrombin also mediates the cleavage of fibrinogen (FG) into fibrin, which adheres to circulating immune cells and facilitates their adhesion and infiltration. EC permeability may lead to fibrin infiltration and deposit formation within the CNS parenchyma. Fibrin deposits activate microglia, leading to the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and ROS that subsequently promote axonal damage as well as neuron death contributing to MS development. The effects of leaked fibrin on other resident nervous system cells remain to be explored.

Funding:

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01HL101972, R01HL151367, R21CA223461, R24NS104161, and R44HL117589).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Conflicts of Interest: N. Verbout and A. Gruber are employees of Aronora, Inc., and they as well as OHSU may have a financial interest in the results of this study. N. Verbout and O. McCarty are inventors on a patent for METHODS AND COMPOSITIONS USED IN TREATING INFLAMMATORY AND AUTOIMMUNE DISEASES (US Patent 10,137,177) which has been licensed by Aronora, Inc. J.J. Shatzel reports receiving consulting fees from Aronora, Inc. The other authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Adams RA et al. (2007) The fibrin-derived gamma377–395 peptide inhibits microglia activation and suppresses relapsing paralysis in central nervous system autoimmune disease J Exp Med 204:571–582 doi: 10.1084/jem.20061931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed O, Geraldes R, DeLuca GC, Palace J (2019) Multiple sclerosis and the risk of systemic venous thrombosis: A systematic review Mult Scler Relat Disord 27:424–430 doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2018.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akassoglou K et al. (2004) Fibrin depletion decreases inflammation and delays the onset of demyelination in a tumor necrosis factor transgenic mouse model for multiple sclerosis Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:6698–6703 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303859101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alabanza LM, Bynoe MS (2012) Thrombin induces an inflammatory phenotype in a human brain endothelial cell line J Neuroimmunol 245:48–55 doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alabanza LM, Esmon NL, Esmon CT, Bynoe MS (2013) Inhibition of endogenous activated protein C attenuates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inducing myeloid-derived suppressor cells J Immunol 191:3764–3777 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Or A et al. (2008) Rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a 72-week, open-label, phase I trial Ann Neurol 63:395–400 doi: 10.1002/ana.21363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartha K, Dömötör E, Lanza F, Adam-Vizi V, Machovich R (2000) Identification of thrombin receptors in rat brain capillary endothelial cells J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 20:175–182 doi: 10.1097/00004647-200001000-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum CL, Arpey CJ (2005) Normal cutaneous wound healing: clinical correlation with cellular and molecular events Dermatol Surg 31:674–686; discussion 686 doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beilin O et al. (2005) Increased thrombin inhibition in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis J Neurosci Res 79:351–359 doi: 10.1002/jnr.20270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berny-Lang MA et al. (2011) Thrombin mutant W215A/E217A treatment improves neurological outcome and reduces cerebral infarct size in a mouse model of ischemic stroke Stroke 42:1736–1741 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.603811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berny MA, White TC, Tucker EI, Bush-Pelc LA, Di Cera E, Gruber A, McCarty OJ (2008) Thrombin mutant W215A/E217A acts as a platelet GPIb antagonist Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28:329–334 doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.156273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggio E et al. (2016) Thrombin Cleavage of Osteopontin Modulates Its Activities in Human Cells In Vitro and Mouse Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis In Vivo J Immunol Res 2016:9345495 doi: 10.1155/2016/9345495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailoiu E, Shipsky MM, Yan G, Abood ME, Brailoiu GC (2017) Mechanisms of modulation of brain microvascular endothelial cells function by thrombin Brain Res 1657:167–175 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brueckmann M et al. (2004) Activated protein C inhibits the release of macrophage inflammatory protein-1-alpha from THP-1 cells and from human monocytes Cytokine 26:106–113 doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burda JE, Radulovic M, Yoon H, Scarisbrick IA (2013) Critical role for PAR1 in kallikrein 6-mediated oligodendrogliopathy Glia 61:1456–1470 doi: 10.1002/glia.22534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burzynski LC et al. (2019) The Coagulation and Immune Systems Are Directly Linked through the Activation of Interleukin-1α by Thrombin Immunity 50:1033–1042.e1036 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell AM, Di Cera E (2000) Rational design of a potent anticoagulant thrombin J Biol Chem 275:39827–39830 doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000751200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A, Nishiyama A, Peterson J, Prineas J, Trapp BD (2000) NG2-positive oligodendrocyte progenitor cells in adult human brain and multiple sclerosis lesions J Neurosci 20:6404–6412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A, Tourtellotte WW, Rudick R, Trapp BD (2002) Premyelinating oligodendrocytes in chronic lesions of multiple sclerosis N Engl J Med 346:165–173 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi CI, Yoon H, Drucker KL, Langley MR, Kleppe L, Scarisbrick IA (2018) The Thrombin Receptor Restricts Subventricular Zone Neural Stem Cell Expansion and Differentiation Sci Rep 8:9360 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27613-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SH, Lee DY, Kim SU, Jin BK (2005) Thrombin-induced oxidative stress contributes to the death of hippocampal neurons in vivo: role of microglial NADPH oxidase J Neurosci 25:4082–4090 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4306-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu AJ (2011) Tissue factor, blood coagulation, and beyond: an overview Int J Inflam 2011:367284 doi: 10.4061/2011/367284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin SR (2000) Thrombin signalling and protease-activated receptors Nature 407:258–264 doi: 10.1038/35025229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courville CB (1959) The effects of heparin in acute exacerbations of multiple sclerosis. Observations and deductions Bull Los Angel Neuro Soc 24:187–196 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culpepper WJ et al. (2019) Validation of an algorithm for identifying MS cases in administrative health claims datasets Neurology 92:e1016–e1028 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese S, Vetrano S, Zhang L, Poplis VA, Castellino FJ (2010) The protein C pathway in tissue inflammation and injury: pathogenic role and therapeutic implications Blood 115:1121–1130 doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-201616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos D, Akassoglou K (2012) Fibrinogen as a key regulator of inflammation in disease Semin Immunopathol 34:43–62 doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0290-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos D et al. (2014) Early detection of thrombin activity in neuroinflammatory disease Ann Neurol 75:303–308 doi: 10.1002/ana.24078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos D et al. (2012) Fibrinogen-induced perivascular microglial clustering is required for the development of axonal damage in neuroinflammation Nat Commun 3:1227 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca C, Virtuoso A, Maggio N, Papa M (2017) Neuro-Coagulopathy: Blood Coagulation Factors in Central Nervous System Diseases Int J Mol Sci 18 doi: 10.3390/ijms18102128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake TA, Morrissey JH, Edgington TS (1989) Selective cellular expression of tissue factor in human tissues. Implications for disorders of hemostasis and thrombosis Am J Pathol 134:1087–1097 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duperray A et al. (1997) Molecular identification of a novel fibrinogen binding site on the first domain of ICAM-1 regulating leukocyte-endothelium bridging J Biol Chem 272:435–441 doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddleston M, de la Torre JC, Oldstone MB, Loskutoff DJ, Edgington TS, Mackman N (1993) Astrocytes are the primary source of tissue factor in the murine central nervous system. A role for astrocytes in cerebral hemostasis J Clin Invest 92:349–358 doi: 10.1172/JCI116573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feistritzer C, Riewald M (2005) Endothelial barrier protection by activated protein C through PAR1-dependent sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-1 crossactivation Blood 105:3178–3184 doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feistritzer C, Schuepbach RA, Mosnier LO, Bush LA, Di Cera E, Griffin JH, Riewald M (2006) Protective signaling by activated protein C is mechanistically linked to protein C activation on endothelial cells J Biol Chem 281:20077–20084 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600506200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festoff BW, Li C, Woodhams B, Lynch S (2012) Soluble thrombomodulin levels in plasma of multiple sclerosis patients and their implication J Neurol Sci 323:61–65 doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festoff BW, Sajja RK, van Dreden P, Cucullo L (2016) HMGB1 and thrombin mediate the blood-brain barrier dysfunction acting as biomarkers of neuroinflammation and progression to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease J Neuroinflammation 13:194 doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0670-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flick MJ et al. (2011) The development of inflammatory joint disease is attenuated in mice expressing the anticoagulant prothrombin mutant W215A/E217A Blood 117:6326–6337 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-304915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flick MJ, Du X, Degen JL (2004) Fibrin(ogen)-alpha M beta 2 interactions regulate leukocyte function and innate immunity in vivo Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 229:1105–1110 doi: 10.1177/153537020422901104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigerio S, Ariano C, Bernardi G, Ciusani E, Massa G, La Mantia L, Salmaggi A (1998) Cerebrospinal fluid thrombomodulin and sVCAM-1 in different clinical stages of multiple sclerosis patients J Neuroimmunol 87:88–93 doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00045-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funes SC, Rios M, Escobar-Vera J, Kalergis AM (2018) Implications of macrophage polarization in autoimmunity Immunology 154:186–195 doi: 10.1111/imm.12910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadepalli R, Kotla S, Heckle MR, Verma SK, Singh NK, Rao GN (2013) Novel role for p21-activated kinase 2 in thrombin-induced monocyte migration J Biol Chem 288:30815–30831 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.463414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Gandhi R, Laroni A, Weiner HL (2010) Role of the innate immune system in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis J Neuroimmunol 221:7–14 doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg N, Smith TW (2015) An update on immunopathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of multiple sclerosis Brain Behav 5:e00362 doi: 10.1002/brb3.362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay FW, Drye TJ, Dick GW, Esiri MM (1997) The application of multifactorial cluster analysis in the staging of plaques in early multiple sclerosis. Identification and characterization of the primary demyelinating lesion Brain 120 (Pt 8):1461–1483 doi: 10.1093/brain/120.8.1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göbel K et al. (2016a) Prothrombin and factor X are elevated in multiple sclerosis patients Ann Neurol 80:946–951 doi: 10.1002/ana.24807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göbel K et al. (2016b) Blood coagulation factor XII drives adaptive immunity during neuroinflammation via CD87-mediated modulation of dendritic cells Nat Commun 7:11626 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin JH, Zlokovic BV, Mosnier LO (2015) Activated protein C: biased for translation Blood 125:2898–2907 doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-355974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin JH, Zlokovic BV, Mosnier LO (2018) Activated protein C, protease activated receptor 1, and neuroprotection Blood 132:159–169 doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-02-769026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber A, Cantwell AM, Di Cera E, Hanson SR (2002) The thrombin mutant W215A/E217A shows safe and potent anticoagulant and antithrombotic effects in vivo J Biol Chem 277:27581–27584 doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200237200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber A, Fernández JA, Bush L, Marzec U, Griffin JH, Hanson SR, DI Cera E (2006) Limited generation of activated protein C during infusion of the protein C activator thrombin analog W215A/E217A in primates J Thromb Haemost 4:392–397 doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01760.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan JX, Sun SG, Cao XB, Chen ZB, Tong ET (2004) Effect of thrombin on blood brain barrier permeability and its mechanism Chin Med J (Engl) 117:1677–1681 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han MH et al. (2008) Proteomic analysis of active multiple sclerosis lesions reveals therapeutic targets Nature 451:1076–1081 doi: 10.1038/nature06559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser SL et al. (2008) B-cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis N Engl J Med 358:676–688 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy LD et al. (2017) Activated protein C inhibits neutrophil extracellular trap formation J Biol Chem 292:8616–8629 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.768309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy LD, Rigg RA, Griffin JH, McCarty OJT (2018) Regulation of immune cell signaling by activated protein C J Leukoc Biol doi: 10.1002/JLB.3MIR0817-338R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuberger DM, Schuepbach RA (2019) Protease-activated receptors (PARs): mechanisms of action and potential therapeutic modulators in PAR-driven inflammatory diseases Thromb J 17:4 doi: 10.1186/s12959-019-0194-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston G, Cuthbertson BH (2009) Activated protein C for the treatment of severe sepsis Clin Microbiol Infect 15:319–324 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02751.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh JY, Smith TD, Meli VS, Tran TN, Botvinick EL, Liu WF (2017) Differential regulation of macrophage inflammatory activation by fibrin and fibrinogen Acta Biomater 47:14–24 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.09.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Leak RK, Shi Y, Suenaga J, Gao Y, Zheng P, Chen J (2015) Microglial and macrophage polarization—new prospects for brain repair Nat Rev Neurol 11:56–64 doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Ma R, Sun S, Wei G, Fang Y, Liu R, Li G (2008) JAK2-STAT3 signaling pathway mediates thrombin-induced proinflammatory actions of microglia in vitro J Neuroimmunol 204:118–125 doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter SF (2016) Overview and diagnosis of multiple sclerosis Am J Manag Care 22:s141–150 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley A et al. (2013) Enhanced effector function of CD8(+) T cells from healthy controls and HIV-infected patients occurs through thrombin activation of protease-activated receptor 1 J Infect Dis 207:638–650 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iezzi G, Scotet E, Scheidegger D, Lanzavecchia A (1999) The interplay between the duration of TCR and cytokine signaling determines T cell polarization Eur J Immunol 29:4092–4101 doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba Y et al. (2001) Plasma thrombin-antithrombin III complex is associated with the severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis J Neurol Sci 185:89–93 doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00468-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn ML, Nakanishi-Matsui M, Shapiro MJ, Ishihara H, Coughlin SR (1999) Protease-activated receptors 1 and 4 mediate activation of human platelets by thrombin J Clin Invest 103:879–887 doi: 10.1172/JCI6042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalashnyk O et al. (2013) Expression, function and cooperating partners of protease-activated receptor type 3 in vascular endothelial cells and B lymphocytes studied with specific monoclonal antibody Mol Immunol 54:319–326 doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kant R, Halder SK, Fernández JA, Griffin JH, Milner R (2020) Activated Protein C Attenuates Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis Progression by Enhancing Vascular Integrity and Suppressing Microglial Activation Front Neurosci 14:333 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan ZS et al. (2015) Thrombin-dependent intravascular leukocyte trafficking regulated by fibrin and the platelet receptors GPIb and PAR4 Nat Commun 6:7835 doi: 10.1038/ncomms8835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YV, Di Cello F, Hillaire CS, Kim KS (2004) Differential Ca2+ signaling by thrombin and protease-activated receptor-1-activating peptide in human brain microvascular endothelial cells Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286:C31–42 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00157.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh CS, Gausas J, Paterson PY (1992) Concordance and localization of maximal vascular permeability change and fibrin deposition in the central neuraxis of Lewis rats with cell-transferred experimental allergic encephalomyelitis J Neuroimmunol 38:85–93 doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(92)90093-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotter MR, Stadelmann C, Hartung HP (2011) Enhancing remyelination in disease--can we wrap it up? Brain 134:1882–1900 doi: 10.1093/brain/awr014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koudriavtseva T (2014) Thrombotic processes in multiple sclerosis as manifestation of innate immune activation Front Neurol 5:119 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koupenova M, Clancy L, Corkrey HA, Freedman JE (2018) Circulating Platelets as Mediators of Immunity, Inflammation, and Thrombosis Circ Res 122:337–351 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer D, Aktas O, Hartung HP, Küry P (2011) The complex world of oligodendroglial differentiation inhibitors Ann Neurol 69:602–618 doi: 10.1002/ana.22415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer HF et al. (2012) Platelets contribute to the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis Circ Res 110:1202–1210 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.256370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Languino LR, Duperray A, Joganic KJ, Fornaro M, Thornton GB, Altieri DC (1995) Regulation of leukocyte-endothelium interaction and leukocyte transendothelial migration by intercellular adhesion molecule 1-fibrinogen recognition Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:1505–1509 doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Languino LR, Plescia J, Duperray A, Brian AA, Plow EF, Geltosky JE, Altieri DC (1993) Fibrinogen mediates leukocyte adhesion to vascular endothelium through an ICAM-1-dependent pathway Cell 73:1423–1434 doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90367-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurens N, Koolwijk P, de Maat MP (2006) Fibrin structure and wound healing J Thromb Haemost 4:932–939 doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01861.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DM, Weinblatt ME (2001) Rheumatoid arthritis Lancet 358:903–911 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06075-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DY, Oh YJ, Jin BK (2005) Thrombin-activated microglia contribute to death of dopaminergic neurons in rat mesencephalic cultures: dual roles of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways Glia 51:98–110 doi: 10.1002/glia.20190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PW, Severin ME, Lovett-Racke AE (2017) TGF-β regulation of encephalitogenic and regulatory T cells in multiple sclerosis Eur J Immunol 47:446–453 doi: 10.1002/eji.201646716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Patterson KR, Bar-Or A (2018) Reassessing B cell contributions in multiple sclerosis Nat Immunol 19:696–707 doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0135-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lider O, Baharav E, Mekori YA, Miller T, Naparstek Y, Vlodavsky I, Cohen IR (1989) Suppression of experimental autoimmune diseases and prolongation of allograft survival by treatment of animals with low doses of heparins J Clin Invest 83:752–756 doi: 10.1172/JCI113953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Rezaee F, Waasdorp M, Shi K, van der Poll T, Borensztajn K, Spek CA (2015) Protease activated receptor-1 regulates macrophage-mediated cellular senescence: a risk for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis Oncotarget 6:35304–35314 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loike JD et al. (1991) CD11c/CD18 on neutrophils recognizes a domain at the N terminus of the A alpha chain of fibrinogen Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88:1044–1048 doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Zambrano M, Rodriguez-Montesinos J, Crespo-Avilan GE, Muñoz-Vega M, Preissner KT (2020) Thrombin Promotes Macrophage Polarization into M1-Like Phenotype to Induce Inflammatory Responses Thromb Haemost 120:658–670 doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1703007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López ML, Soriano-Sarabia N, Bruges G, Marquez ME, Preissner KT, Schmitz ML, Hackstein H (2014) Expression pattern of protease activated receptors in lymphoid cells Cell Immunol 288:47–52 doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2014.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Bhasin M, Tsirka SE (2002) Involvement of tissue plasminogen activator in onset and effector phases of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis J Neurosci 22:10781–10789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund SA, Giachelli CM, Scatena M (2009) The role of osteopontin in inflammatory processes J Cell Commun Signal 3:311–322 doi: 10.1007/s12079-009-0068-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo D et al. (2013) Fibrin facilitates both innate and T cell-mediated defense against Yersinia pestis J Immunol 190:4149–4161 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyden P et al. (2019) Final Results of the RHAPSODY Trial: A Multi-Center, Phase 2 Trial Using a Continual Reassessment Method to Determine the Safety and Tolerability of 3K3A-APC, A Recombinant Variant of Human Activated Protein C, in Combination with Tissue Plasminogen Activator, Mechanical Thrombectomy or both in Moderate to Severe Acute Ischemic Stroke Ann Neurol 85:125–136 doi: 10.1002/ana.25383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machida T et al. (2017a) Role of thrombin-PAR1-PKCθ/δ axis in brain pericytes in thrombin-induced MMP-9 production and blood-brain barrier dysfunction in vitro Neuroscience 350:146–157 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machida T et al. (2017b) Contribution of thrombin-reactive brain pericytes to blood-brain barrier dysfunction in an in vivo mouse model of obesity-associated diabetes and an in vitro rat model PLoS One 12:e0177447 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machida T et al. (2015) Brain pericytes are the most thrombin-sensitive matrix metalloproteinase-9-releasing cell type constituting the blood-brain barrier in vitro Neurosci Lett 599:109–114 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda Y, Solanky M, Menonna J, Chapin J, Li W, Dowling P (2001) Platelet-derived growth factor-alpha receptor-positive oligodendroglia are frequent in multiple sclerosis lesions Ann Neurol 49:776–785 doi: 10.1002/ana.1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mari B et al. (1994) Thrombin and thrombin receptor agonist peptide induce early events of T cell activation and synergize with TCR cross-linking for CD69 expression and interleukin 2 production J Biol Chem 269:8517–8523 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marik C, Felts PA, Bauer J, Lassmann H, Smith KJ (2007) Lesion genesis in a subset of patients with multiple sclerosis: a role for innate immunity? Brain 130:2800–2815 doi: 10.1093/brain/awm236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty I, Péclat V, Kirdaite G, Salvi R, So A, Busso N (2001) Amelioration of collagen-induced arthritis by thrombin inhibition J Clin Invest 107:631–640 doi: 10.1172/JCI11064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschmeyer J, SHEARER R, LONSER E, SPINDLE DK (1961) Heparin potassium in the treatment of chronic multiple sclerosis Bull Los Angel Neuro Soc 26:165–171 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto T et al. (2015) Activated protein C modulates the proinflammatory activity of dendritic cells J Asthma Allergy 8:29–37 doi: 10.2147/JAA.S75261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty OJ, Tien N, Bochner BS, Konstantopoulos K (2003) Exogenous eosinophil activation converts PSGL-1-dependent binding to CD18-dependent stable adhesion to platelets in shear flow Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 284:C1223–1234 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00403.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller T, Hanisch UK, Ransom BR (2000) Thrombin-induced activation of cultured rodent microglia J Neurochem 75:1539–1547 doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751539.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel A, Bijak M, Miller E, Rywaniak J, Miller S, Saluk J (2015) Relationship between the Increased Haemostatic Properties of Blood Platelets and Oxidative Stress Level in Multiple Sclerosis Patients with the Secondary Progressive Stage Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015:240918 doi: 10.1155/2015/240918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosnier LO, Sinha RK, Burnier L, Bouwens EA, Griffin JH (2012) Biased agonism of protease-activated receptor 1 by activated protein C caused by noncanonical cleavage at Arg46 Blood 120:5237–5246 doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-452169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muradashvili N et al. (2012) Fibrinogen-induced increased pial venular permeability in mice J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 32:150–163 doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muradashvili N, Tyagi N, Tyagi R, Munjal C, Lominadze D (2011) Fibrinogen alters mouse brain endothelial cell layer integrity affecting vascular endothelial cadherin Biochem Biophys Res Commun 413:509–514 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naldini A, Bernini C, Pucci A, Carraro F (2005) Thrombin-mediated IL-10 up-regulation involves protease-activated receptor (PAR)-1 expression in human mononuclear leukocytes J Leukoc Biol 78:736–744 doi: 10.1189/jlb.0205082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasirzade J, Kargarpour Z, Hasannia S, Strauss FJ, Gruber R (2020) Platelet-rich fibrin elicits an anti-inflammatory response in macrophages in vitro J Periodontol 91:244–252 doi: 10.1002/JPER.19-0216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LM et al. (2019) A new way to estimate neurologic disease prevalence in the United States: Illustrated with MS Neurology 92:469–480 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nham SU (1999) Characteristics of fibrinogen binding to the domain of CD11c, an alpha subunit of p150,95 Biochem Biophys Res Commun 264:630–634 doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noorbakhsh F, Vergnolle N, Hollenberg MD, Power C (2003) Proteinase-activated receptors in the nervous system Nat Rev Neurosci 4:981–990 doi: 10.1038/nrn1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkuma K, Matsuda K, Kariya R, Goto H, Kamei S, Hamamoto T, Okada S (2015) Anti-inflammatory effects of activated protein C on human dendritic cells Microbiol Immunol 59:381–388 doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panek WK et al. (2019) Local Application of Autologous Platelet-Rich Fibrin Patch (PRF-P) Suppresses Regulatory T Cell Recruitment in a Murine Glioma Model Mol Neurobiol 56:5032–5040 doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1430-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons ME et al. (2017) Thrombin generation correlates with disease duration in multiple sclerosis (MS): Novel insights into the MS-associated prothrombotic state Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin 3:2055217317747624 doi: 10.1177/2055217317747624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson PY (1976) Experimental allergic encephalomyelitis: role of fibrin deposition in immunopathogenesis of inflammation in rats Fed Proc 35:2428–2434 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patibandla PK, Tyagi N, Dean WL, Tyagi SC, Roberts AM, Lominadze D (2009) Fibrinogen induces alterations of endothelial cell tight junction proteins J Cell Physiol 221:195–203 doi: 10.1002/jcp.21845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrikios P et al. (2006) Remyelination is extensive in a subset of multiple sclerosis patients Brain 129:3165–3172 doi: 10.1093/brain/awl217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters PJ, Bazelier MT, Uitdehaag BM, Leufkens HG, De Bruin ML, de Vries F (2014) The risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with multiple sclerosis: the Clinical Practice Research Datalink J Thromb Haemost 12:444–451 doi: 10.1111/jth.12523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puy C, Rigg RA, McCarty OJ (2016) The hemostatic role of factor XI Thromb Res 141 Suppl 2:S8–S11 doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(16)30354-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan S et al. (2017) Activated protein C protects from GvHD via PAR2/PAR3 signalling in regulatory T-cells Nat Commun 8:311 doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00169-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigg RA et al. (2019) Protease-activated receptor 4 activity promotes platelet granule release and platelet-leukocyte interactions Platelets 30:126–135 doi: 10.1080/09537104.2017.1406076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues SF, Granger DN (2015) Blood cells and endothelial barrier function Tissue Barriers 3:e978720 doi: 10.4161/21688370.2014.978720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu J, Pyo H, Jou I, Joe E (2000) Thrombin induces NO release from cultured rat microglia via protein kinase C, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and NF-kappa B J Biol Chem 275:29955–29959 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001220200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu JK et al. (2015) Blood coagulation protein fibrinogen promotes autoimmunity and demyelination via chemokine release and antigen presentation Nat Commun 6:8164 doi: 10.1038/ncomms9164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu JK et al. (2018) Fibrin-targeting immunotherapy protects against neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration Nat Immunol 19:1212–1223 doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0232-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuepbach RA, Feistritzer C, Fernández JA, Griffin JH, Riewald M (2009) Protection of vascular barrier integrity by activated protein C in murine models depends on protease-activated receptor-1 Thromb Haemost 101:724–733 doi: 10.1160/th08-10-0632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scolding N, Franklin R, Stevens S, Heldin CH, Compston A, Newcombe J (1998) Oligodendrocyte progenitors are present in the normal adult human CNS and in the lesions of multiple sclerosis Brain 121 (Pt 12):2221–2228 doi: 10.1093/brain/121.12.2221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheremata WA, Jy W, Horstman LL, Ahn YS, Alexander JS, Minagar A (2008) Evidence of platelet activation in multiple sclerosis J Neuroinflammation 5:27 doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons J, Pittet JF (2015) The coagulopathy of acute sepsis Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 28:227–236 doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha RK et al. (2018) PAR1 biased signaling is required for activated protein C in vivo benefits in sepsis and stroke Blood 131:1163–1171 doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-10-810895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen PS et al. (2014) Safety and efficacy of ofatumumab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a phase 2 study Neurology 82:573–581 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stearns-Kurosawa DJ, Kurosawa S, Mollica JS, Ferrell GL, Esmon CT (1996) The endothelial cell protein C receptor augments protein C activation by the thrombin-thrombomodulin complex Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:10212–10216 doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolz L, Derouiche A, Devraj K, Weber F, Brunkhorst R, Foerch C (2017) Anticoagulation with warfarin and rivaroxaban ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis J Neuroinflammation 14:152 doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0926-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturn DH, Kaneider NC, Feistritzer C, Djanani A, Fukudome K, Wiedermann CJ (2003) Expression and function of the endothelial protein C receptor in human neutrophils Blood 102:1499–1505 doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugama Y, Tiruppathi C, offakidevi K, Andersen TT, Fenton JW, Malik AB (1992) Thrombin-induced expression of endothelial P-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1: a mechanism for stabilizing neutrophil adhesion J Cell Biol 119:935–944 doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suo Z et al. (2002) Participation of protease-activated receptor-1 in thrombin-induced microglial activation J Neurochem 80:655–666 doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00745.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suo Z, Wu M, Citron BA, Gao C, Festoff BW (2003) Persistent protease-activated receptor 4 signaling mediates thrombin-induced microglial activation J Biol Chem 278:31177–31183 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302137200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]