Abstract

New insights into the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders suggest the existence of a complex interplay between genetics and environment. This notion is supported by evidence suggesting that exposure to stress during pregnancy exerts profound effects on the neurodevelopment and behavior of the offspring and predisposes them to psychiatric disorders later in life. Accumulated evidence suggests that vulnerability to psychiatric disorders may result from permanent negative effects of long-term changes in synaptic plasticity due to altered epigenetic mechanisms (histone modifications and DNA methylation) that lead to condensed chromatin architecture, thereby decreasing the expression of candidate genes during early brain development. In this chapter, we have summarized the literature of clinical studies on psychiatric disorders induced by maternal stress during pregnancy. We also discussed the epigenetic alterations of gene regulations induced by prenatal stress. Because the clinical manifestations of psychiatric disorders are complex, it is obvious that the biological progression of these diseases cannot be studied only in post-mortem brains of patients and the use of animal models is required. Therefore, in this chapter, we have introduced a well-established mouse model of prenatal stress (PRS) generated in restrained pregnant dams. The behavioral phenotypes of the offspring (PRS mice) born to the stressed dam and underlying epigenetic changes in key molecules related to synaptic activity were described and highlighted. PRS mice may serve as a useful model for investigating the pathogenesis of psychiatric disorders and may be a useful tool for screening for the potential compounds that may normalize aberrant epigenetic mechanisms induced by prenatal stress.

Keywords: Maternal prenatal stress, Psychiatric disorders, Epigenetics, DNA methylation, Histone modification, Synaptic plasticity

I. INTRODUCTION

Psychiatric disorders, or mental illnesses are devastating, complex diseases involving alterations in mood, cognition and behaviors. By clinical definition, mental illnesses are a heterogeneous group of disorders including depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, alcohol/drug abuse, dementia and autism (Newson et al., 2020). Epidemiological data demonstrate that psychiatric disorders account for about 14% of the global burden of disease (Vigo et al., 2016). Although the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders remains largely unknown, a growing body of literature suggests an association between prenatal maternal stress and a variety of adverse offspring outcomes, including neurodevelopmental disorders like anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, personal disorders, autism spectrum disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and alcohol use disorder (Becker et al., 2011; Gordon, 2002; Sinha, 2007, 2008; Uhart & Wand, 2009; Charil et al., 2010; Fine et al., 2014; Markham & Koenig, 2011; Mulder et al., 2002; Fumagalli et al., 2007; Weinstock et al, 2008; Maccari et al., 1995, 2003, Ramborger et al., 2018, McGowan & Szyf., 2010). This evidence implies the notion that an aberrant prenatal biological programming driven by epigenetic mechanisms may be an important contributing factor of psychiatric disorders. In this chapter, we aimed to review the progress in the field and highlight recent advances regarding this notion.

II. PRENATAL STRESS IS ASSOCIATED WITH PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS IN ADULT OFFSPRING

1. Mood Disorders

Epidemiological and clinical studies have revealed that stress during pregnancy may lead to mood disorders in offspring. Brannigan et al (Brannigan et al. 2019) examined associations between exposure to subjective maternal stress during pregnancy and subsequent diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in offspring from 3626 individuals. The results showed that individuals whose mothers reported stress during pregnancy had significantly greater odds of developing a psychiatric disorder, particularly a mood disorder including anxiety. Interestingly, these associations remained the same after excluding parental psychiatric history. Brown et al. (Brown et al. 2000) observed that the risk of developing major affective disorder was increased for subjects with exposure to famine in the second trimester and was increased significantly for subjects with exposure in the third trimester, relative to unexposed subjects. Also, it was found that children whose mothers experienced high levels of anxiety in late pregnancy exhibited higher rates of behavioral/emotional problems like postnatal anxiety and depression (O’Connor et al., 2014, 2016). The third month of fetal development appears to represent a period of special vulnerability. In a study of a large number of offspring, researchers found that those who were in their first trimester of fetal development during the Arab–Israeli war in June 1967 were more likely to develop mood disorders; for bipolar disorder the risk was doubled and for other psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, the risk was tripled (Kleinhaus et al., 2013). Taken together, a time-limited exposure to a severe threat during early gestation may be associated with an increased risk for the development of affective disorders in offspring.

2. Psychotic Disorders

Emerging evidence indicates that fetal exposure to maternal stress has been linked to pathogenesis of schizophrenia in offspring. For example, a link between maternal stress during pregnancy and schizophrenia spectrum disorders was investigated and it was found that maternal daily life stress during pregnancy was associated with significantly increased odds of schizophrenia spectrum disorders among male but not female offspring, suggesting sex-specific fetal sensitivity to risk for schizophrenia spectrum disorders (Fineberg et al., 2016). Findings from clinical studies by Pugliese et al (Pugliese et al., 2019) revealed that schizophrenia spectrum disorder (SSD) was positively associated with maternal stress during pregnancy. These results support a role for maternal stress as a risk factor for subsequent severe mental illness in adulthood. In a population-based study, Khashan et al (2008) found that severe maternal stress during the first trimester may alter the risk of schizophrenia in offspring. Moreover, results from several independent studies have revealed that stressful life events during pregnancy, including exposure to war, earthquake, flood, and death of a spouse or relative, have been associated with schizophrenia in offspring (Huttunen & Niskanen, 1978; Selten et al., 1999a, 1999b; Fineberg et al., 2016, Malaspina et al., 2008). These findings support a link between maternal stress with development of SSD in offspring (Debost et al., 2015).

3. Personality Disorders

Clinical studies have found that exposure to adverse life events during pregnancy has been linked to personality disorders. Personality disorders are mental illnesses marked by an ongoing pattern of varying moods, self-image, and behavior, including impulsive actions, anger, depression, and anxiety. It has been shown that compared with unexposed controls, those exposed to moderate prenatal stress had three times the odds and those exposed to severe prenatal stress had seven times the odds of developing a personality disorder (Brannigan et al., 2019).

4. Autism

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental illness characterized by deficits in social communication and the presence of restricted interests or repetitive patterns of behavior (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). There is a substantial body of evidence from human studies suggesting that prenatal stress during pregnancy can have a significant role in the pathophysiology of ASD (Kinney et al., 2008). Varcin et al (2017) performed multiple regression analyses to examine associations between maternal prenatal stress events and the severity of ASD-associated symptoms in children with ASD. They found that exposure to prenatal stress was a significant predictor of ASD-related symptom severity amongst children with ASD. In follow-up analyses, significant increases in symptom severity were found only in the context of multiple (two or more) prenatal stressful life events. There is also evidence that prenatal stress in pregnancy may contribute to autism-like traits in the general population. Two independent cohort studies have reported that increased maternal exposure to common stressful life events during pregnancy is predictive of increased autism-related trait severity in the offspring (Rijlaarsdam et al., 2017). Similarly, it was found that the degree of objective as well as subjective distress experienced by mothers during their pregnancy was associated with higher levels of autism-like traits in the offspring (Walder et al., 2014). However, findings from a population-based cohort study did not support any strong association between prenatal stress after maternal bereavement and the risk of autism (Li et al., 2009).

5. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

In a population cohort study, multiple regression analyses showed that maternal stressful events during pregnancy significantly predicted ADHD behaviors in both male and female offspring, after controlling for autistic traits and other confounding variables (Ronald et al., 2011). Similarly, in the same cohort, stressful events during pregnancy significantly predicted autistic traits in only male offspring, after controlling for ADHD behaviors and confounding variables. In another human study (O’Connor et al., 2002, 2003), it was found that high levels of anxiety during late pregnancy were associated with increased risk of hyperactivity and inattention. Moreover, one study found out that maternal prenatal stress was a good predictor of difficulties with attention regulation and externalizing problems in the offspring (Gutteling et al., 2005; DiPietro et al., 2006; Ramborger et al., 2018).

6. Alcohol Use Disorder

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is associated with disabilities and huge social cost (Bouchery et al., 2006; GBD 2018). The emerging challenge for AUD is that this disorder is consistently associated with a higher prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities, and the prevalence rates of comorbidity is currently rising (Wiener et al., 2018; Fink et al., 2016). Furthermore, the pathogenesis of AUD remains unknown.

Currently, there is not much information regarding the impact of prenatal stress on AUD in adulthood. However, some evidence suggests that there is a link between early life stress and alcohol and drug dependence (Enoch, 2011), and this link is supported by large-scale studies (King & Laplante, 2005). On the other hand, it is well established that mood disorders are often comorbid with AUDs (Holahan et al., 2001; Schmidt et al., 2007, de Graaf et al., 2003; Robinson et al., 2009; Schuckit & Hesselbrock, 1994; McDolnald & Meyer, 2011; Burns & Teesson, 2002, Hasin et al., 2007). Maternal prenatal stress during pregnancy can be a risk factor for mood disorders such as anxiety and depression (Beydoun & Saftlas, 2008; Weinstock et al, 2008), which are themselves linked to a greater tendency toward alcohol abuse, likely leading to AUD. This indicates an indirect link between prenatal stress and AUD. These findings suggest that adverse life events during pregnancy may lead to a greater propensity toward AUD in adulthood (Campbell 2009).

III. EPIGENETICS OF PSYCHOTIC DISORDERS

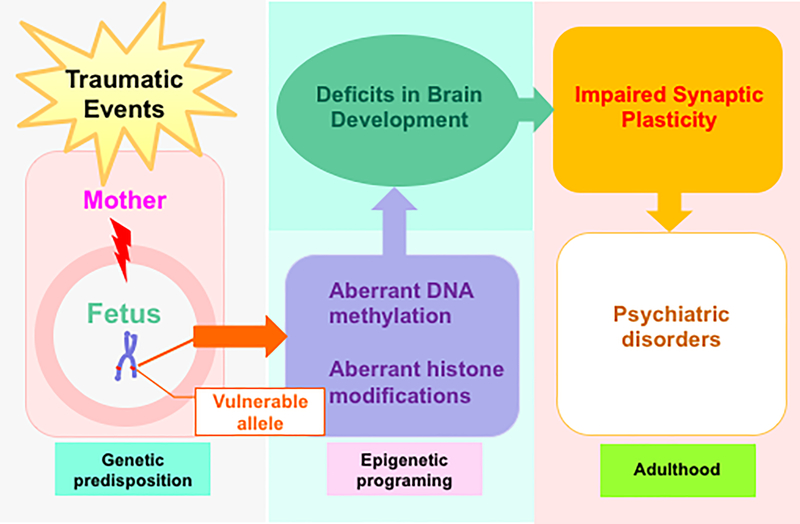

Psychiatric diseases such as schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease and autism do not always conform to a classical Mendelian pattern of inheritance. It is already evident that epigenetic mechanisms play crucial role in their pathogenesis (Ptak & Petronis, 2010). At normal physiological conditions, maintenance of DNA methylation and histone modifications is crucial for brain neurodevelopment and functioning, while dysregulation of these components is highly deleterious and can predispose individuals to any of the illness (Monk et al., 2019) mentioned above, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Maternal stress during pregnancy and psychiatric disorders.

Stress during pregnancy negatively impacts the development of fetal brain through aberrant epigenetic programming on vulnerable loci that exerts long lasting effects on synaptic formation, function and plasticity, leading to psychiatric phenotypes in adult offspring.

1. Basic Biology of Epigenetics

Epigenetics is defined as modifications of the genome that do not involve a change in the DNA sequence (Haig et al., 2004). Evidence suggests that epigenetic changes are stable enough to be inherited through generations and may lead to stable phenotypic alterations in the organisms (Campos et al., 2014). To date, several epigenetic mechanisms and the molecular pathways underlying the regulation of the epigenome have been revealed.

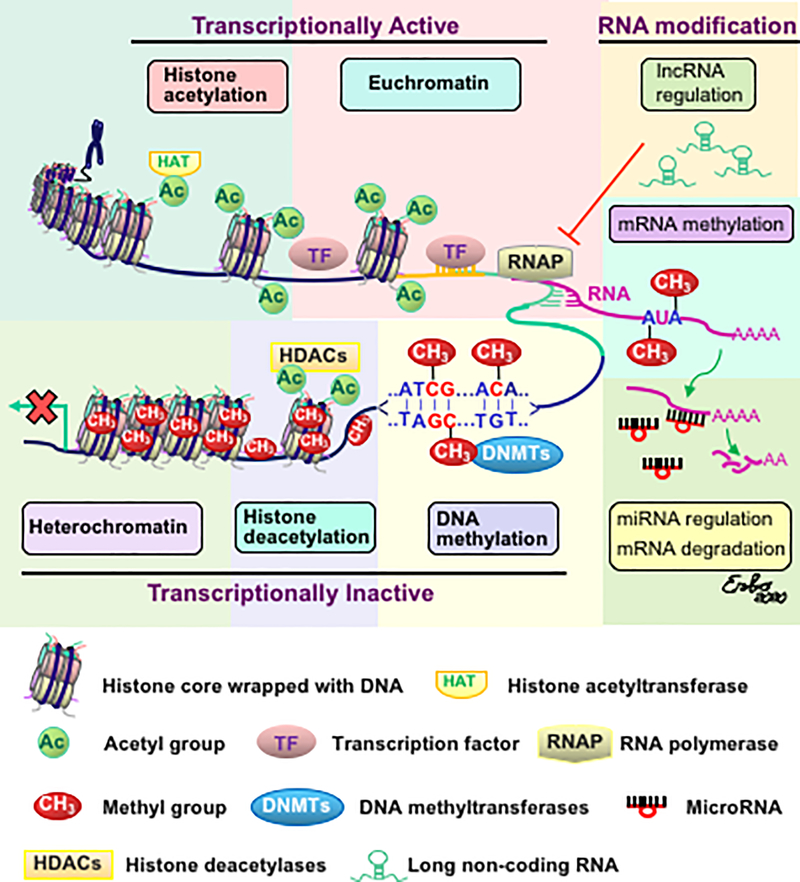

These mechanisms can be classified into general categories: 1) modification of chromatin structure and 2) post transcriptional modification. Chromatin is composed of several units (nucleosomes), each consisting of DNA wrapped around a complex of octamer histone proteins (Kornberg & Thomas, 1974a, 1974b; Luger et al., 1997; Allan et al., 1986). Chromatin mainly exists in two structural states that reflect its accessibility to the transcriptional machinery. When the chromatin is in a more relaxed state, where the DNA is broadly accessible to the transcription machinery, it is called euchromatin. Euchromatin is considered the transcriptionally active state. In contrary, the transcriptionally inactive state of chromatin is highly condensed, which prevents DNA from being accessible to the transcriptional machinery. This state of chromatin is called heterochromatin. Figure 2 shows a representative scheme of epigenetic regulation of gene expression.

Figure 2. The scheme of downregulation of gene expressions by epigenetic mechanisms in the brain.

Epigenetic regulation of gene expression is controlled by remodeling of chromatin structure (Kornberg & Thomas, 1974a, 1974b; Luger et al., 1997; Allan et al., 1986). Specifically, chromatin condensation (heterochromatin) and relaxation (euchromatin) block or allow the accessibility of gene promoters to the transcriptional factors. Chromatin is formed by a DNA molecule wrapped around an octamer of histones. Histone acetylation and low levels of DNA methylation facilitate chromatin relaxation that allows transcriptional activation, whereas histone deacetylation, catalyzed by histone deacetylases (HDACs) and DNA methylation on the cytosine-phospho-guanine (CpG) domain, catalyzed by DNMTs, leads to closed chromatin and to transcriptional silencing (Jeltsch & Gowher 2019; Breiling & Lyko 2015). Epigenetic regulation of gene expression that occurs at the mRNA level can be mediated by m6A methylation (Zaccara et al., 2019), inhibition of RNA polymerase by long non-coding RNA (Roundtree et al., 2017), or degradation of mRNA by microRNAs (Selbach et al., 2008).

1). Histone Modifications

Histones are small proteins composed of a core, C-terminal and N-terminal tails. DNA is a double-stranded helix wrapped around a histone octamer composed of two copies each of histones H2a, H2b, H3, and H4 and 146 bp of DNA as shown in Figure 2. This structure, called the nucleosome, is the fundamental unit of chromatin. Epigenetic modifications of chromatin at the molecular level are covalent modifications of the histone proteins which occur largely at histone H3 and histone H4 and include acetylation, methylation, demethylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation and adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-ribosylation (Bannister & Kouzarides, 2011; Mersfelder & Parthun, 2006). Amongst them, acetylation and methylation are the best characterized mechanisms and are also the most used in experimental procedures (Bannister & Kouzarides, 2011). Acetylation occurs at lysine (K), and methylation occurs at both Ks and arginines (R) of the histone tails (Jenuwein & Allis, 2001).

Hyperacetylation of histones is associated with chromatin de-condensation and consequently with increased gene transcription (Brownell et al., 1996), and the reversal process of this modification, called histone deacetylation, is catalyzed by families of histone deacetylases (HDACs) (Taunton et al., 1996; Shahbazian & Grunstein., 2007). The enzymes that catalyse acetylation are called histone acetyltransferases (HATs), which add an acetyl group at histone tails that neutralizes the positive charge of lysine, thereby introducing repulsive forces between the histone tails and DNA that leads to an open chromatin which allows transcription factor access. The acetylation/deacetylation generally occurs on lysine residues of the N-terminal tails and is perfectly balanced in order to accurately regulate chromatin activity and gene expression (Jenuwein & Allis, 2001; Narlikar et al., 2002).

Histone methylation is catalysed by histone methyltransferases (HMTs) and occurs on single or multiple lysine or arginine residues in different levels (mono-, di-, or tri-methylation) (Lachner & Jenuwein, 2002; Zhang et al., 2013). The methylated histone can be demethylated by histone demethylases. Therefore, this is a reversible modification for histones. Histone methylation may lead to either gene activation or repression, depending on the residue involve. For example, methylation on K9 residue of histone H3 is associated with gene repression, whereas methylation on K4 of the same histone promotes gene expression (Martin & Zhang, 2005). These histone modifications can alter the affinity of these proteins for the DNA, making chromatin more or less accessible for attracting or repelling different transcriptional activators or repressors (Wolffe & Hayes, 1999).

2). Histone Variants.

Recent studies have revealed that nucleosomes also can be modified by the replacement of core histones with histone variants such as H3.3, H2A.X, and H2A.Z, which may affect the activity of the genomic region around which they are located (Ausió et al., 2006, Talbert et al., 2017; Hake & Allis 2006). Histone variants are found to be involved in psychiatric disorders. For instance, Chang et al. (Chang et al., 2015) found that there is a link between H2A.Z and schizophrenia. In another study, Lepack et al. (Lepack et al., 2016) found that H3.3 Dynamics are increased in nucleus accumbens (NAc) of both depressed humans and animal models of depression. These studies suggest that the chromatin processes characterized by dynamics of histone variants may be important in the pathogenesis of mental disorders induced by stress.

3). DNA Methylation Mechanisms

The methylation of cytosine nucleotides within DNA is another modification of the genome that regulates gene expression. In this case, the methylation occurs directly on the DNA, usually by transferring the methyl group from S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) to the 5th carbon of the cytosine base at the dinucleotide sequence CpG (cytosine and guanine separated by one phosphate group), forming a 5-methylcytidine (5-mC). Up to approximately 80% of CpG dinucleotides can be methylated. The process, which may occur de novo or on previously hemi-methylated residues during replication, is catalysed by a family of enzymes called DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), include DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1), DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A), and DNA methyltransferase 3B (DNMT3B). (Jeltsch & Gowher 2019; Breiling & Lyko 2015). When DNA methylation occurs in the promoter region of the gene, the gene is strongly repressed. Such repression is further strengthened by the association with protein complexes containing methyl binding domain proteins such as methyl-CpG–binding protein (MeCP2) that mediates gene silencing, HDACs and HMTs (Lachner & Jenuwein, 2002). With these mechanisms, several genes can be silenced in a cell-specific manner, and significant stretches of entire chromosomes can be silenced.

Intriguingly, methylated CpG sequences can be actively demethylated when they are packaged into hyperacetylated histones (Métivier et al., 2008) through base excision/nucleotide repair mechanisms which provide the means to a net demethylation reaction (Zhang et al., 2007), and the direct removal of the methyl group from methylated CpG dinucleotides has also been demonstrated under certain circumstances (Dahl et al., 2011).

In addition to DNA methylation, the 5-mC mark on promoter CpG-rich regions of specific genes can be oxidized by ten-eleven translocation (TET) proteins to form 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-hmC) in the mammalian brain (Ito et al. 2010; Tahiliani et al., 2009; Guo et al., 2011; Kriaucionis et al., 2009; Bhutani et al., 2011) It has been proposed that 5-hmC undergoes two successive processing steps: (a) a deamination step that is catalyzed by the activation-induced deaminase (AID) / apoliporotein B mRNA-editing enzyme complex (APOBEC) family of cytosine deaminases, turning 5-hmC into 5-hydroxylmethyluracil (5-hmU); and (b) the base excision repair pathway, in which 5-hmU can be removed and replaced by unmethylated cytosine by a group of glycosylases such as methyl-CpG-binding domain protein 4 (MBD4) and thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG4) (Zhu et al., 2009; Morgan et al., 2004; Rai et al., 2008). Moreover, additional DNA modifications have been observed, such as cytosine formylation (fc) and carboxylation (caC) (Kohli & Zhang, 2013; Bhutani et al., 2011). However, the biological embedding of fC and caC in regulating gene expression remains to be elucidated.

4). RNA Modifications

Emerging evidence indicates that noncoding RNAs play central roles in transcriptional regulation (Roundtree et al., 2017). Noncoding RNAs include microRNAs and long noncoding RNA. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are about 22 nucleotides in length, single-stranded, noncoding RNAs (O’Brien et al., 2018). MiRNAs usually interact with proteins to form RNA-induced silencing complexes that degrade mRNA or inhibit its translation into protein (Selbach et al., 2008). Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are about 200 base pairs in length (Quinn & Chang 2016; Lee & Bartolomei, 2013) and are very abundant in the neuronal system (Long et al., 2017). Like DNA, the RNA nucleotides can be modified by methylation, which modulates RNA biology such as structure and stability. The most abundant mRNA modification is N-methyladenosine (m6A), which is involved in key neuronal functions (Zaccara et al., 2019).

Presently, epigenetics becomes a hub which links to biology of various diseases. There are several different review articles describing epigenetic mechanisms underlying different diseases. The review articles published in the field (Allis & Jenuwein, 2016), Cavalli and Heard (Cavalli & Heard., 2019) and Weinhold (Weinhold., 2006) provide more detail into epigenetic regulations of gene expression.

2. Epigenetic Regulations in Psychiatric Disorders

Presently, the casual mechanisms of psychiatric disorders represent an important knowledge gap that, if filled, could add to our ability to provide more effective treatments. Psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with psychosis demonstrate a complex symptomatology characterized by positive/negative symptoms and cognitive impairment (Grayson & Guidotti, 2013). Accumulated evidence suggests that the mission to understand the genetic etiology of psychiatric illnesses will be more successful with integrative approaches considering both genetic and epigenetic factors (reviewed by Abdolmaleky et al., 2008; Day et al., 2015, Cromby 2019, Mehler, 2008; Morgan & Bale.2011; Oberlander et al., 2008; Tsankova et al., 2007).

Recent human studies have established many genes associated with psychiatric disorders. For example, genes encoding dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2), D3 (DRD3), and D4 (DRD4), serotonin receptor 2A (HTR2A) and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), dopamine receptor D1 (DRD1), n-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor- glutamate [NMDA] receptor subunit zeta-1 (GRIN1), glutamate [NMDA] receptor subunit epsilon-1 (GRIN2A), and glutamate [NMDA] receptor subunit epsilon-2 (GRIN2B), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and dopamine transporter- solute carrier family 6 member 3 (SLC6A3) have been implicated in the etiology of psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression (Talkowski et al., 2007; Salatino-Oliveira et al., 2018; Nuernberg et al., 2016). Furthermore, available data have demonstrated that epigenetic modification of reelin (RELN), BDNF, and the DRD2 promoters confer susceptibility to psychiatric conditions (Guidotti et al.,2000)

Patients with psychosis (schizophrenia and bipolar disorder) express an increase in brain DNMT1 and DNMT3A, and an increase in ten-eleven translocation hydroxylase (TET1) in the cortex (Dong et al., 2012). TET1 is considered to facilitate the removal of 5-mC from gene regions via formation of the intermediate 5-hmC that favors deamination catalyzed by the AID/APOBEC family of cytidine deaminases. It has been found that both TET1 mRNA and protein (Dong et al., 2014) is markedly increased (2- to 3-fold) in the parietal cortex of psychotic patients, and this increase is associated with an increase of 5-hmC levels in genomic DNA containing the glutamate decarboxylase 67 (GAD67) and BDNF variant IX promoters in proximity of their transcriptional start sites. This increase may be specific to the cortex because the cerebellum of the same patients fails to show significant TET1 changes. Thus, the increase of TET1 and the decreases in APOBAC3A and APOBAC3C found in this study, together with previous studies showing an increase in DNMT1 and growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible, beta 45 (GADD45b) in the cortices of patients with psychiatric disorders, supports the hypothesis that an epigenetic dysregulation of gene expression may be operative in the pathogenesis of major psychosis, including schizophrenia (SZ) and bipolar disorders (Dong et al., 2014).

Major depression is a chronic, remitting syndrome involving widely distributed circuits in the brain. Stable alterations in gene expression that contribute to structural and functional changes in multiple brain regions are implicated in the heterogeneity and pathogenesis of the illness. Increasing evidence from both postmortem brains of depressed humans and clinical studies indicates that epigenetic mechanisms are associated with the pathogenesis of depressive disorders (reviewed by Sun et al., 2013, Schroeder et al., 2010; McGowan & Kato, 2008).

Recently, a significant epigenetic component in the pathology of suicide has been elucidated. Murphy et al showed that psychiatric patients with a history of suicide attempt had significantly higher levels of global DNA methylation compared with controls (Murphy et al., 2013). Adverse alterations of gene expression profiles, such as in the promotor regions of glucocorticoid receptor or brain-derived neurotrophic factor genes, were shown to be inducible by early life stress and reversible by epigenetic reagents. Also, profound evidence supports the role for histone deacetylase inhibitors as novel antidepressants through counteracting previously acquired adverse epigenetic marks. The epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene has been suggested as a molecular basis of such stress vulnerability. In addition, available data showed that the effects of antidepressant treatment, including electroconvulsive therapy, may be mediated by histone modification on the promoter of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene (McGowan & Kato, 2008).

Several studies have demonstrated epigenetic regulation in all stages of neurodevelopment, including embryonic, postnatal and adult neurogenesis (Fagiolini et al., 2009; Gonzales-Roybal & Lim, 2013; Ma et al., 2010; Roth & Sweatt, 2011), suggesting that epigenetic mechanisms mediate gene-environment interplay during the entire lifespan. Aberrations in the epigenetic regulation have been revealed in several neuropsychiatric diseases with well-established neurodevelopmental impairments in their physiopathology, such as schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders (Rangasamy et al., 2013; Zhubi et al., 2014a).

Autism spectrum disorder is a complex disorder with many different genetic risk factors. In a human study, Zhubi et al. (2014b) investigated epigenetic mechanisms underlying the transcriptional regulation of candidate genes in cerebella of ASD patients, including the binding of MeCP2 to the GAD67, glutamate decarboxylase 65(GAD65), and RELN promoters and gene bodies. The enrichment of 5-hmC and decrease in 5-mC at the GAD67 or Reln promoters detected by 5-hmC and 5-mC antibodies was confirmed by TET-assisted bisulfite sequencing. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that an increase of 5-hmC (relative to 5-mC) at specific gene domains enhances the binding of MeCP2 to 5-hmC and reduces expression of the corresponding target genes in ASD cerebella.

Rett Syndrome (RS), an X-linked, neurodevelopmental disorder is considered to belong to ASD because of its autistic-like behavioural phenotype, such as indifference to other people, absence of speech, avoidance of eye-contact, social isolation) (Zoghbi et al., 2005). Studies showed that RS is caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the gene encoding the transcriptional repressor MeCP2 (Amir et al., 1999; Moretti et al., 2006; Wan et al., 1999; Yasui et al., 2014), leading to an increased synaptic inhibition in cortical neurons (Calfa et al., 2014; Dani et al., 2005) through a misinterpretation of the DNA methylation pattern (Horike et al., 2005; Meehan et al., 1992; Singh et al., 2008; Willard & Hendrich, 1999; Yasui et al., 2007).

Fragile X Syndrome (FXS) is another autism spectrum disorder. FXS patients express mental retardation, repetitive speech, stereotyped behaviour, autistic features, anxiety and ADHD-like symptoms (Baumgardner et al., 1995; Terracciano et al., 2005). Studies found that hypermethylation on a CpG islands in the promoter region of the fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1) gene, blocking the synthesis of its product, the Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein (FMRP) (Godler et al., 2010; Pieretti et al., 1991), leading to abnormal dendrite growth and impaired synaptic connections (as reviewed by He and Portera-Cailliau, 2013). Moreover, beyond DNA hypermethylation, several other epigenetic mechanisms also involved in the pathogenesis of FXS, such as demethylation at histone H3 at lysine 4 and hypermethylation of histone H3 at lysine 9 (Coffee et al, 2002; Eiges et al., 2007) and RNA interference (Ashley et al., 1993; Siomi et al., 1993).

It must be noted that the epigenetic alterations found in the psychiatric disorders described above may not be caused by prenatal stress. The roles of postnatal stress, adolescent stress and other adversity in early life cannot be excluded. Altogether, the evidence provided by these studies suggests that, in addition to genetic factors, gene-environment interaction may be linked to the pathogenesis of psychiatric disorders.

3. Psychiatric Disorders Induced by Prenatal Stress via Epigenetic Regulations

Because of challenges and limitations inherent in human research, the direct evidence of the role of prenatal stress in inducing psychiatric disorders is limited. The results from a human study provided a direct link between BDNF methylation induced by prenatal stress and behavioural outcomes (Kundakovic et al., 2015). Other studies found that prenatal exposure to increased depressed and anxious mood in the third trimester increased methylation of the nuclear receptor subfamily 3 group C member 1 (NR3C1, a gene encoding glucocorticoid receptor) gene in new-borns (Oberlander et al., 2008). The methylation of NR3C1 altered hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) stress reactivity which may serve as a risk factor for mental illnesses later in life. Prenatal stress may be a risk of non-psychiatric disease in offspring via epigenetic mechanism. For example, whole genome bisulfite sequencing revealed that psychological stress during pregnancy increased the risk of wheeze and asthma in childhood via alterations in DNA methylation (Trump et al., 2016). Several excellent articles have reviewed evidence from human studies that prenatal stress may increase risk of psychiatric disorders through epigenetic mechanisms (Thorsell, & Nätt, 2016; Shimada-Sugimoto et al., 2015; Lei et al., 2016, Curr. Mol Bio Rep and Ikegame et al., 2013).

IV. PRENATAL STRESS ANIMAL MODELS OF PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS AND EPIGENETIC MECHANISMS

It is not always possible to conduct investigational or interventional studies in patients with psychiatric disorders for a variety of reasons: 1) Patients with psychiatric disorders may be unavailable. 2) Patients with psychiatric disorders may be available but unwilling to participate in studies. 3) The primary site of the human body involving epigenetic dysregulation in psychiatric disorders, the brain, is highly inaccessible. Thus, for research purposes, animal models of psychiatric disorders must serve as relevant substitutes for patients. To date, several animal models designed to mimic prenatal stress induced psychiatric disorders by using different stressors have been established, including saline injection, forced swimming, crowding, restraint alone or restraint with heat and bright light (Weinstock et al., 2016, Cao-Lei et al., 2017; and Charil et al., 2010), and prenatal immune activation by injection of poly (I:C) (Labouesse et al., 2013). In non-human primates, an acoustic startle protocol is preferred (Weinstock et al., 2016, Charil et al., 2010).

These stressors have common features that are relatively unpredictable and uncontrollable, with sudden triggering of HPA cascade in responding adverse stimuli (Charil et al., 2010; Weinstock et al., 2016). The level of stress response in the pregnant animal depends on the type of stressor. It has been shown that stressors such as restraint, forced swimming, and crowding each significantly increase plasma levels of corticosterone in the pregnant dam (Murmu et al., 2006), with restraint showing the greatest increase, followed by forced swimming, and finally by crowding. Furthermore, the impacts of prenatal stress are also known to depend on other factors, such as sex of the offspring (Darnaudéry et al., 2008, Zuena et al., 2008), time of gestation when the stressor is applied (Charil 2010), and species and strain of animals (Charil et al., 2010, Neeley et al., 2011).

1. Schizophrenia-like Behaviors

Several studies have established and characterized a mouse model in offspring of mothers restrained during gestation as a possible laboratory model of SZ using Swiss albino ND4 mice (Matrisciano et al., 2012, 2013). They housed pregnant mice individually with a 12-hour light/dark cycle with food and water ad libitum. Control dams were left undisturbed throughout gestation, whereas stressed dams were subjected to repeated episodes of restraint stress. The stress procedure restrained the pregnant dam in a 12 × 3-cm transparent tube under a bright light for 30 minutes two times a day from the seventh day of pregnancy until delivery. Following weaning (postnatal day 21, PND21), male mice were chosen for further study and housed separately, five per cage. At PND 60, non-stressed (control) and prenatally stressed (PRS) male mice were used to examine the SZ-like behaviors, including locomotor activity, social interaction with an intruder in a novel environment, prepulse inhibition at startle, and contextual fear conditioning. The results showed a deficit in social interaction, locomotor activity, prepulse inhibition and fear memory in PRS mice as compared to their counterpart control. In biochemical studies, the authors found that PRS mice showed reduced expression of both metabotropic glutamate receptor 2 (mGlu2) and 3 (mGlu3) receptors in the frontal cortex. Such mice also showed changes in mRNA expression of the Bdnf, Gad67, and Dnmt1 genes. According to the authors, these features represent behavioral and biochemical changes consistent with a SZ-like phenotype. Koenig et al. (Koenig et al., 2005) demonstrated that prenatal exposure to variable stressors led to SZ-like behaviors in adult offspring.

In further epigenetic experiments in PRS mice, high levels of DNMT1 and DNMT3A mRNA expression were found in the frontal cortex. Using GAD67–green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgenic mice, the authors established that in both control and PRS mice increased levels of DNMT1 and DNMT3A were preferentially expressed in GABAergic neurons of the frontal cortex and hippocampus. The overexpression of DNMT1 and DNMT3A in GABAergic neurons was associated with a decline in RELN and GAD67 expression in PRS mice during early and adult life (Matrisciano et al., 2012, 2013).

In addition, it has been shown that PRS mice have increased promoter binding of DNMT1 and MeCP2 and an increase in 5-mC and 5-hmC in specific CpG regions of the promoters of the Reln and Gad67 genes. In one study (Dong et al. 2014) using the PRS mouse model of SZ, it was found that adult PRS offspring demonstrate behavioral abnormalities suggestive of SZ and molecular changes similar to changes seen in postmortem brains of patients with SZ, including a significant increase in DNA methyltransferase 1 and ten-eleven-translocation hydroxylase 1 in the frontal cortex and hippocampus but not in cerebellum and a significant decrease in Bdnf messenger RNA variants. The decrease of the corresponding Bdnf transcript level was accompanied by an enrichment of 5-mC and 5-hmC at Bdnf gene regulatory regions. In addition, the expression of Bdnf transcripts (IV and IX) correlated positively with social approach in both PRS mice and non-stressed mice.

Clozapine (CLO), an atypical antipsychotic medication, is mainly used for SZ that does not improve following the use of other antipsychotics. In PRS mice, the behavioral deficits, the increased 5-mC and 5-hmC at Gad67, Reln and Bdnf promoters, and the reduced expression of the mRNAs and proteins corresponding to these genes in the frontal cortex is reversed by treatment with clozapine but not by haloperidol (a typical antipsychotic medication). Interestingly, CLO had no effect on either the behavior, promoter methylation or the expression of these mRNAs and proteins when administered to offspring of non-stressed pregnant mice. CLO, but not haloperidol, reduced the elevated levels of DNMT1 and TET1, as well as the elevated levels of DNMT1 binding to Gad67, Reln and Bdnf promoters in PRS mice suggesting that CLO may limit DNA methylation by interfering with DNA methylation dynamics (Dong et al., 2016).

To establish whether CLO produces its behavioral and molecular action through a causal involvement of DNA methylation/demethylation processes, a further study was performed to compare the epigenetic action of CLO with that of the DNMT1 competitive inhibitor, N-Phthalyl-L-tryptophan (RG108). The intracerebroventricular (i.c.v) injection of RG108 (20 nmol/day/5 days), similar to the systemic administration of CLO, corrects the altered behavioral and molecular endophenotypes typical of PRS mice. These results are consistent with an epigenetic etiology underlying the behavioral SZ-like endophenotypic profile in PRS mice (Dong et al 2019).

As mentioned above, immune activation during pregnancy may increase the risk of SZ. This has prompted researchers to mimic it in animals. Prenatal immune challenge in pregnant rodents produces abnormalities in the behavioral phenotype, histological data, and mRNA expression in offspring (Macêdo et al., 2012). Maternal viral infection causes SZ-like alterations of serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) and mGlu2 receptors in the adult offspring (Moreno et al., 2011). The offspring of mice prenatally infected with influenza at times from E7 through E18 show alterations in gene expression and protein and brain structural abnormalities (Kneeland et al., 2013). Moreover, the synthetic viral mimic Poly(I:C) and the proinflammatory agent lipopolysaccharide also induce brain and behavioral abnormalities in offspring (Giovanoli et al., 2013). Using an established mouse model of prenatal immune challenge that is based on maternal treatment with the viral mimetic poly (I:C), Labouesse et al. (Labouesse et al., 2015) found that prenatal immune activation increased prefrontal levels of 5-mC and 5-hmC in the promoter region of Gad67. The early-life challenge also increased 5-mC levels at the promoter region of Gad65. These effects were accompanied by elevated Gad67 and Gad65 promoter binding of MeCP2 and by reduced Gad67 and Gad65 mRNA expression. Moreover, the epigenetic modifications at the Gad67 promoter correlated with prenatal infection-induced impairments in working memory and social interaction. This study highlights that hypermethylation of Gad67 and Gad65 promoters may be an important molecular mechanism linking prenatal infection to presynaptic GABAergic impairments and associated behavioral and cognitive abnormalities in the offspring.

2. Depression and Anxiety-Like Behaviors

Prenatal stress produces depression-and anxiety-like behavior in young adult mice. Zheng et al. (2016) performed prenatal stress on dam of Kunming species mice. The gestational-stress dams were housed in a separate room with fluorescent ceiling lights. The stress procedure consisted of restraining the pregnant dam in a transparent tube (12 cm × 3 cm) for 30 minutes three times per day from the fifth day of pregnancy until delivery, and 24-h constant light throughout gestation. After weaning, male mice were selected for the study. At PND 40, depressive-like and anxiety behaviors of young adult offspring were examined using Forced Swimming and Tail suspension tests. The results show that offspring from gestational stress dams exhibited depression-like and anxiety behaviors. Biochemically, stress-offspring showed decreased expression of BDNF in the hippocampus along with increased expression of HDAC1 and HDAC2, and decreased levels of acetylated histone 3 lysine 14 (AcH3K14) as compared to non-stress offspring. Results from Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) and Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays demonstrated that increased DNA methylation and decreased binding of AcH3K14 on specific Bdnf promoters were responsible for its downregulation. Interestingly, the depressive-like behaviors induced by prenatal stress were rescued by inhibition of DNMT1 (Ye et al. 2018).

3. Mood Disorder Comorbidity of AUD-Like Behaviors

Dong et al. (2018) using the same prenatal stress protocol, examined anxiety-like and alcohol drinking behaviors in adult (PND 75) offspring of PRS mice using well-characterized paradigms: elevated plus maze, light/dark box and two-bottle free-choice paradigm of drinking. It was found that PRS mice exhibit heightened anxiety-like behaviors and increased ethanol intake in adulthood. From biochemical experiments, decreases were found in mRNA and protein expressions of key genes associated with synaptic plasticity, such as activity regulated cytoskeleton associated protein (Arc), spinophilin (Spn), postsynaptic density 95 (Psd95), tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB), protein kinase B (Akt), and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) of PRS mice and their controls. Further study revealed that downregulation of these molecules resulted in significant decrease in the density of dendritic spines in PRS mice, suggesting that synaptic remodeling caused by prenatal stress is the causal factor for anxiety-like behaviors and excessive ethanol intake in the adult offspring. To explore the mechanisms underlying downregulation of these molecules, DNA methylation and histone modification on these genes were analyzed. The results indicated hypermethylation or reduced histone H3K14 acetylation on the promoters of above genes, suggesting epigenetic regulation may be responsible for deficits in their expression and may be driving the phenotypes of anxiety and alcohol intake.

V. CONCLUSIONS

Both findings from clinical and animal studies provide evidence that prenatal stress has negative long-term effects on offspring and has been linked to the pathogenesis of psychiatric disorders. It is thus necessary to establish proper animal models for investigating neurobiological mechanisms by which prenatal stress induces psychiatric disorders and develop effective therapeutic strategies. Available data from animal models clearly indicate that prenatal stress affects offspring brain development and can lead to psychiatric-like behaviors through epigenetic remodeling on target genes.

However, several factors for translating these findings to humans should be considered: differences in species with various gestational lengths and development processes, timing differences in stress exposure, and different types of stressors and sex differences in responding to stressors (Van den Bergh et al. 2017, Charil et al., 2010). Moreover, prenatal stress affects almost all brain regions and connectome, including the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, cerebellum and hypothalamus (Soares-Cunha, et al., 2018; Scheinost et al., 2017). However, how and to what extent these regions contribute to psychiatric-like behaviors remain largely unknown. As such, PRS animal model provide a useful tool for investigating interactions among different brain regions and neuronal circuits associated in the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders.

As described above, mice and rats subjected to maternal prenatal stress develop characteristics resembling various psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, anxiety disorder, alcohol use disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, major depressive disorder, cognitive disorders, and drug addiction (Charil et al., 2010; Silvagni et al., 2008; Van den Bergh et al., 2017; Walsh et al 2019). In this light, use of the animal model described in this chapter could help in the investigation of the role of epigenetics in the pathophysiology and treatment of psychiatric disorders, including AUD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the NIH-NIAAA R21AA027848 grant to ED and by NIH-NIAAA P50AA022538, UO1AA019971 [NADIA], R01 AA025035 and by the VA merit grant and Senior Research Career Scientist award to SCP.

REFERENCES

- Abdolmaleky HM, Zhou JR, Thiagalingam S, Smith CL. (2008). Epigenetic and pharmacoepigenomic studies of major psychoses and potentials for therapeutics. Pharmacogenomics. 9(12):1809–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan J, Mitchell T, Harborne N, Bohm L, Crane-Robinson C (1986). Roles of H1 domains in determining higher order chromatin structure and H1 location. J Mol Biol 187: 591–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allis CD, & Jenuwein T (2016). The molecular hallmarks of epigenetic control. Nature reviews. Genetics, 17(8), 487–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association; (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. (1999). Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat Genet. 23(2):185–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley CT Jr, Wilkinson KD, Reines D, Warren ST. (1993). FMR1 protein: conserved RNP family domains and selective RNA binding. Science. 262(5133):563–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausió J (2006). Histone variants--the structure behind the function. Briefings in functional genomics & proteomics, 5(3), 228–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister AJ, & Kouzarides T (2011). Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell research, 21(3), 381–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgardner TL, Reiss AL, Freund LS, Abrams MT. (1995). Specification of the neurobehavioral phenotype in males with fragile X syndrome. Pediatrics 95(5):744–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker G, & Kowall M (1977). Crucial role of the postnatal maternal environment in the expression of prenatal stress effects in the male rats. Journal of comparative and physiological psychology, 91(6), 1432–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC, Lopez MF, & Doremus-Fitzwater TL (2011). Effects of stress on alcohol drinking: a review of animal studies. Psychopharmacology, 218(1), 131–156. 10.1007/s00213-011-2443-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun H, & Saftlas AF (2008). Physical and mental health outcomes of prenatal maternal stress in human and animal studies: a review of recent evidence. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology, 22(5), 438–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutani N, Burns DM, & Blau HM (2011). DNA demethylation dynamics. Cell, 146(6), 866–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchery EE, Harwood HJ, Sacks JJ, Simon CJ, Brewer RD. (2006). Economic costs of excessive alcohol consumption in the U.S.,Am J Prev Med. 41(5):516–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannigan R, Cannon M, Tanskanen A, Huttunen MO, Leacy FP, & Clarke MC (2019). The association between subjective maternal stress during pregnancy and offspring clinically diagnosed psychiatric disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 139(4), 304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiling A, & Lyko F (2015). Epigenetic regulatory functions of DNA modifications: 5-methylcytosine and beyond. Epigenetics & chromatin, 8, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AS, van Os J, Driessens C, Hoek HW, & Susser ES (2000). Further evidence of relation between prenatal famine and major affective disorder. The American journal of psychiatry, 157(2), 190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell JE, Zhou J, Ranalli T, Kobayashi R, Edmondson DG, Roth SY, et al. (1996). Tetrahymena histone acetyltransferase A: a homolog to yeast Gcn5p linking histone acetylation to gene activation. Cell, 84(6), 843–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns L, & Teesson M (2002). Alcohol use disorders comorbid with anxiety, depression and drug use disorders. Findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well Being. Drug and alcohol dependence, 68(3), 299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calfa G, Li W, Rutherford JM, & Pozzo-Miller L (2015). Excitation/inhibition imbalance and impaired synaptic inhibition in hippocampal area CA3 of Mecp2 knockout mice. Hippocampus, 25(2), 159–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC, Szumlinski KK, & Kippin TE (2009). Contribution of early environmental stress to alcoholism vulnerability. Alcohol (Fayetteville, N.Y.), 43(7), 547–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos EI, Stafford JM, & Reinberg D (2014). Epigenetic inheritance: histone bookmarks across generations. Trends in cell biology, 24(11), 664–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao-Lei L, de Rooij SR, King S, Matthews SG, Metz G, Roseboom TJ, & Szyf M (2017). Prenatal stress and epigenetics. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, S0149–7634(16)30726–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao-Lei L, Laplante DP & King S (2016). Prenatal Maternal Stress and Epigenetics: Review of the Human Research. Curr Mol Bio Rep 2, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli G, & Heard E (2019). Advances in epigenetics link genetics to the environment and disease. Nature, 571(7766), 489–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang M, Sun L, Liu X, Sun W, & You X (2015). Association of common variants in H2AFZ gene with schizophrenia and cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia. Journal of human genetics, 60(10), 619–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charil A, Laplante DP, Vaillancourt C & King S. (2010): Prenatal stress and brain development. Brain Res Rev. 65: 56–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffee B, Zhang F, Ceman S, Warren ST, Reines D. (2002). Histone modifications depict an aberrantly heterochromatinized FMR1 gene in fragile x syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 71(4):923–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromby J, Chung E, Papadopoulos D, & Talbot C (2019). Reviewing the epigenetics of schizophrenia. Journal of mental health (Abingdon, England), 28(1), 71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl C, Grønbæk K, & Guldberg P (2011). Advances in DNA methylation: 5-hydroxymethylcytosine revisited. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry, 412(11–12), 831–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani VS, Chang Q, Maffei A, Turrigiano GG, Jaenisch R, Nelson SB. (2005). Reduced cortical activity due to a shift in the balance between excitation and inhibition in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 102(35):12560–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnaudéry M, & Maccari S (2008). Epigenetic programming of the stress response in male and female rats by prenatal restraint stress. Brain research reviews, 57(2), 571–585. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JJ, Kennedy AJ, & Sweatt JD (2015). DNA methylation and its implications and accessibility for neuropsychiatric therapeutics. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology, 55, 591–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf R, Bijl RV, Spijker J, Beekman AT, & Vollebergh WA (2003). Temporal sequencing of lifetime mood disorders in relation to comorbid anxiety and substance use disorders--findings from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 38(1), 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debost JC, Petersen L, Grove J, Hedemand A, Khashan A, Henriksen T, et al. (2015). Investigating interactions between early life stress and two single nucleotide polymorphisms in HSD11B2 on the risk of schizophrenia. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 60, 18–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPietro JA, Novak MF, Costigan KA, Atella LD, Reusing SP (2006). Maternal psychological distress during pregnancy in relation to child development at age two. Child Dev 77: 573–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong E, Dzitoyeva S, Matrisciano F, Tueting P, Grayson DR, Guidotti A. (2014). BDNF epigenetic modifications associated with schizophrenia-like phenotype induced by prenatal stress in mice. Biol Psychiatry. 77(6):589–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong E, Guidotti A, Zhang H, Pandey SC. (2018). Prenatal stress leads to chromatin and synaptic remodeling and excessive alcohol intake comorbid with anxiety-like behaviors in adult offspring. Neuropharmacology. 15;140:76–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong E, Tueting P, Matrisciano F, Grayson DR, Guidotti A. (2016). Behavioral and molecular neuroepigenetic alterations in prenatally stressed mice: relevance for the study of chromatin remodeling properties of antipsychotic drugs. Transl Psychiatry. 12;6:e711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong E, Gavin DP, Chen Y, & Davis J (2012). Upregulation of TET1 and downregulation of APOBEC3A and APOBEC3C in the parietal cortex of psychotic patients. Translational psychiatry, 2(9), e159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong E, Locci V, Gatta E, Grayson DR, & Guidotti A (2019). N-Phthalyl-l-Tryptophan (RG108), like Clozapine (CLO), Induces Chromatin Remodeling in Brains of Prenatally Stressed Mice. Molecular pharmacology, 95(1), 62–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiges R, Urbach A, Malcov M, Frumkin T, Schwartz t, Amit A, et al. (2007). Developmental studies of fragile x Syndrome using human embryonic stem cells derived from preimplantation genetically diagnosed embryos. Cell Stem Cell. 1(5):568–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch MA. (2011). The role of early life stress as a predictor for alcohol and drug dependence. Psychopharmacology. (Berl). 214(1):17–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagiolini M, Jensen CL, Champagne FA. (2009). Epigenetic influences on brain development and plasticity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 19(2):207–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine R, Zhang J & Stevens HE. (2014). Prenatal stress and inhibitory neuron systems: implications for neuropsychiatric disorders Mol Psychiatry 19:641–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg AM, Ellman LM, Schaefer CA, Maxwell SD, Shen L, Chaudhury NH, et al. (2016). Fetal exposure to maternal stress and risk for schizophrenia spectrum disorders among offspring: Differential influences of fetal sex. Psychiatry research, 236, 91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink DS, Gallaway MS, Tamburrino MB, Liberzon I, Chan P, Cohen GH, et al. (2016). Onset of Alcohol Use Disorders and Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders in a Military Cohort: Are There Critical Periods for Prevention of Alcohol Use Disorders? Prev Sci. 17(3):347–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli F, Molteni R, Racagni G, & Riva MA (2007). Stress during development: Impact on neuroplasticity and relevance to psychopathology. Progress in neurobiology, 81(4), 197–217. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators. (2018). Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 22;392 (10152):1015–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanoli S, Engler H, Engler A, Richetto J, Voget M, Willi R, et al. (2013). Stress in puberty unmasks latent neuropathological consequences of prenatal immune activation in mice. Science (New York, N.Y.), 339(6123), 1095–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godler DE, Tassone F, Loesch DZ, Taylor AK, Gehling F, Hagerman RJ, et al. (2010). Methylation of novel markers of fragile X alleles is inversely correlated with FMRP expression and FMR1 activation ratio. Hum Mol Genet. 19(8):1618–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales-Roybal G, Lim DA. (2013). Chromatin-based epigenetics of adult subventricular zone neural stem cells. Front Genet. October 8;4:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon HW (2002). Early environmental stress and biological vulnerability to drug abuse. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 27(1–2):115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson DR, Guidotti A. (2013). The dynamics of DNA methylation in schizophrenia and related psychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 38:138–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti A, Auta J, Davis JM, Di-Giorgi-Gerevini V, Dwivedi Y, Grayson DR, et al. (2000). Decrease in reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase67 (GAD67) expression in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a postmortem brain study. Archives of general psychiatry, 57(11), 1061–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JU, Su Y, Zhong C, Ming GL, & Song H (2011). Hydroxylation of 5-methylcytosine by TET1 promotes active DNA demethylation in the adult brain. Cell, 145(3), 423–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutteling BM, de Weerth C, Willemsen-Swinkels SH, Huizink AC, Mulder EJ, et al. (2005). The effects of Prenatal Stress on temperament and problem behavior of 27-month-old toddlers. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 14: 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haig D (2004). The (dual) origin of epigenetics. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 69:67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hake SB, Allis CD (2006). Histone H3 variants and their potential role in indexing mammalian genomes: the “H3 barcode hypothesis”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103(17):6428–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, & Grant BF (2007). Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of general psychiatry, 64(7), 830–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He CX, Portera-Cailliau C. (2013). The trouble with spines in fragile X syndrome: density, maturity and plasticity. Neuroscience 251:120–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Cronkite RC, & Randall PK (2001). Drinking to cope, emotional distress and alcohol use and abuse: a ten-year model. Journal of studies on alcohol, 62(2), 190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horike S, Cai S, Miyano M, Cheng JF, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. (2005). Loss of silent-chromatin looping and impaired imprinting of DLX5 in Rett syndrome. Nat Genet 37:31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttunen MO, & Niskanen P (1978). Prenatal loss of father and psychiatric disorders. Archives of general psychiatry, 35(4), 429–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegame T, Bundo M, Murata Y, Kasai K, Kato T, & Iwamoto K (2013). DNA methylation of the BDNF gene and its relevance to psychiatric disorders. Journal of human genetics, 58(7), 434–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, D’Alessio AC, Taranova OV, Hong K, Sowers LC, & Zhang Y (2010). Role of Tet proteins in 5mC to 5hmC conversion, ES-cell self-renewal and inner cell mass specification. Nature, 466(7310), 1129–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeltsch A, & Gowher H (2019). Editorial-Role of DNA Methyltransferases in the Epigenome. Genes, 10(8), 574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenuwein T and Allis CD (2001). Translating the histone code. Science 293:1074–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khashan AS, Abel KM, McNamee R, Pedersen MG, Webb RT, Baker PN, et al. (2008). Higher risk of offspring schizophrenia following antenatal maternal exposure to severe adverse life events. Archives of general psychiatry, 65(2), 146–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King S, & Laplante DP (2005). The effects of prenatal maternal stress on children’s cognitive development: Project Ice Storm. Stress (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 8(1), 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney DK, Munir KM, Crowley DJ, Miller AM. (2008). Prenatal stress and risk for autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev.;32(8):1519–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhaus K, Harlap S, Perrin M, Manor O, Margalit-Calderon R, Opler M, Friedlander Y, & Malaspina D (2013). Prenatal stress and affective disorders in a population birth cohort. Bipolar disorders, 15(1), 92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneeland RE, Fatemi SH. (2013). Viral infection, inflammation and schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry;42:35–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig JI, Elmer GI, Shepard PD, Lee PR, Mayo C, Joy B, et al. (2005). Prenatal exposure to a repeated variable stress paradigm elicits behavioral and neuroendocrinological changes in the adult offspring: potential relevance to schizophrenia. Behavioural brain research, 156(2), 251–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli RM, & Zhang Y (2013). TET enzymes, TDG and the dynamics of DNA demethylation. Nature, 502(7472), 472–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg RD, Thomas JO. (1974). Chromatin structure: oligomers of the histones. Science 184(4139):865–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg RD. (1974). Chromatin structure: a repeating unit of histones and DNA. Science 184(4139):868–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T (2007). Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 128:693–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriaucionis S, & Heintz N (2009). The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in Purkinje neurons and the brain. Science (New York, N.Y.), 324(5929), 929–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundakovic M, Gudsnuk K, Herbstman JB, Tang D, Perera FP, & Champagne FA (2015). DNA methylation of BDNF as a biomarker of early-life adversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(22), 6807–6813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouesse MA, Dong E, Grayson DR, Guidotti A, & Meyer U (2015). Maternal immune activation induces GAD1 and GAD2 promoter remodeling in the offspring prefrontal cortex. Epigenetics, 10(12), 1143–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachner M and Jenuwein T (2002). The many faces of histone lysine methylation. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol 14:286–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JT, Bartolomei MS. (2013). X-inactivation, imprinting, and long non- coding RNAs in health and disease. Cell, 152:1308–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepack AE, Bagot RC, Peña CJ, Loh YE, Farrelly LA, Lu Y, et al. (2016). Aberrant H3.3 dynamics in NAc promote vulnerability to depressive-like behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(44), 12562–12567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Vestergaard M, Obel C, Christensen J, Precht DH, et al. (2009). A nationwide study on the risk of autism after prenatal stress exposure to maternal bereavement. Pediatrics, 123(4), 1102–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long Y, Wang X, Youmans DT, & Cech TR (2017). How do lncRNAs regulate transcription? Science advances, 3(9), eaao2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K, Mäder AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. (1997). Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 389(6648):251–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma DK, Marchetto MC, Guo JU, Ming GL, Gage FH, Song H. (2010). Epigenetic choreographers of neurogenesis in the adult mammalian brain. Nat Neurosci. 13(11):1338–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccari S, Darnaudéry M, Morley-Fletcher S, Zuena AR, Cinque C, Van Reeth O. (2003). Prenatal stress and long- term consequences: implications of glucocorticoid hormones. Neurosci Biobehav Rev;27:119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccari S, Piazza PV, Kabbaj M, Barbazanges A, Simon H, Moal ML. (1995). Adoption reverses the long-term impairment in glucocorticoid feedback induced by prenatal stress. J Neurosci;15:110–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macêdo DS, Araújo DP, Sampaio LR, Vasconcelos SM, Sales PM, Sousa FC, et al. (2012). Animal models of pre- natal immune challenge and their contribution to the study of schizophrenia: a systematic review. Braz J Med Biol Res;45:179–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaspina D, Corcoran C, Kleinhaus KR, Perrin MC, Fennig S, Nahon D, Friedlander Y, & Harlap S (2008). Acute maternal stress in pregnancy and schizophrenia in offspring: a cohort prospective study. BMC psychiatry, 8, 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham JA, & Koenig JI (2011). Prenatal stress: role in psychotic and depressive diseases. Psychopharmacology, 214(1), 89–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C and Zhang Y (2005). The diverse functions of histone lysine methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6(11):838–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matrisciano F, Tueting P, Dalal I, Kadriu B, Grayson DR, Davis JM, Nicoletti F, Guidotti A. (2013). Epigenetic modifications of GABAergic interneurons are associated with the schizophrenia-like phenotype induced by prenatal stress in mice. Neuropharmacology. 68:184–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matrisciano F, Tueting P, Maccari S, Nicoletti F, Guidotti A. (2012). Pharmacological activation of group-II metabotropic glutamate receptors corrects a schizophrenia-like phenotype induced by prenatal stress in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 37(4):929–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JL, & Meyer TD (2011). Self-report reasons for alcohol use in bipolar disorders: why drink despite the potential risks? Clinical psychology & psychotherapy, 18(5), 418–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan PO, Kato T. (2008). Epigenetics in mood disorders. Environ Health Prev Med. 13(1):16–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan PO, Szyf M. (2010): The epigenetics of social adversity in early life: implications for mental health outcomes. Neurobiol Dis 39(1):66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan RR, Lewis JD, Bird AP. (1992). Characterization of MeCP2, a vertebrate DNA binding protein with affinity for methylated DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 20:5085–5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehler MF (2008). Epigenetic principles and mechanisms underlying nervous system functions in health and disease. Progress in neurobiology, 86(4), 305–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersfelder EL, & Parthun MR (2006). The tale beyond the tail: histone core domain modifications and the regulation of chromatin structure. Nucleic acids research, 34(9), 2653–2662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Métivier R, Gallais R, Tiffoche C, Le Péron C, Jurkowska RZ, Carmouche RP, et al. (2008). Cyclical DNA methylation of a transcriptionally active promoter. Nature, 452(7183), 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk C, Lugo-Candelas C, & Trumpff C (2019). Prenatal Developmental Origins of Future Psychopathology: Mechanisms and Pathways. Annual review of clinical psychology, 15, 317–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno JL, Kurita M, Holloway T, López J, Cadagan R, Martínez-Sobrido L, et al. (2011). Maternal influenza viral infection causes schizophrenia-like alterations of 5–HT2A and mGlu2 receptors in the adult offspring. J Neurosci;31:1863–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti P, Zoghbi HY. (2006). MeCP2 dysfunction in Rett syndrome and related disorders. Curr Opin Genet Dev16:276–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CP, Bale TL. (2011). Early prenatal stress epigenetically programs dysmasculization in second-generation offspring via the paternal lineage. J Neurosci;31:11748–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan HD, Dean W, Coker HA, Reik W, & Petersen-Mahrt SK (2004). Activation-induced cytidine deaminase deaminates 5-methylcytosine in DNA and is expressed in pluripotent tissues: implications for epigenetic reprogramming. The Journal of biological chemistry, 279(50), 52353–52360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder EJ., Robles de Medina PG, Huizink AC., Van den Bergh BR., Buitelaar JK., Visser GH. (2002). Prenatal maternal stress: effects on pregnancy and the (unborn) child. Early Hum Dev. 70(1–2):3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgatroyd C, Quinn JP, Sharp HM, Pickles A, & Hill J (2015). Effects of prenatal and postnatal depression, and maternal stroking, at the glucocorticoid receptor gene. Translational psychiatry, 5(5), e560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murmu MS, Salomon S, Biala Y, Weinstock M, Braun K, Bock J. (2006). Changes of spine density and dendritic complexity in the prefrontal cortex in offspring of mothers exposed to stress during pregnancy. Eur J Neurosci;24:1477–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy TM, Mullins N, Ryan M, Foster T, Kelly C, McClelland R, et al. (2013). Genetic variation in DNMT3B and increased global DNA methylation is associated with suicide attempts in psychiatric patients. Genes Brain Behav. 12(1):125–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narlikar GJ, Fan HY and Kingston RE (2002). Cooperation between complexes that regulate chromatin structure and transcription. Cell 108: 475–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neeley EW, Berger R, Koenig JI, Leonard S. (2011). Strain dependent effects of prenatal stress on gene expression in the rat hippocampus. Physiol Behav;104:334–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newson JJ, Hunter D, & Thiagarajan TC (2020). The Heterogeneity of Mental HealtAssessment. Frontiers in psychiatry, 11, 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuernberg GL, Aguiar B, Bristot G, Fleck MP, & Rocha NS (2016). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor increase during treatment in severe mental illness inpatients. Translational psychiatry, 6(12), e985 10.1038/tp.2016.227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Heron J, Golding J, Beveridge M, Glover V (2002). Maternal antenatal anxiety and children’s behavioural/emotional problems at 4 years. Br J Psychiatry 180: 502–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Heron J, Golding J, Glover V; ALSPAC Study Team. (2003). Maternal antenatal anxiety and behavioural/emotional problems in children: a test of a programming hypothesis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 44: 1025–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander TF, Weinberg J, Papsdorf M, Grunau R, Misri S, & Devlin AM (2008). Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics, 3, 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien J, Hayder H, Zayed Y, & Peng C (2018). Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Frontiers in endocrinology, 9, 402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Monk C, & Burke AS (2016). Maternal Affective Illness in the Perinatal Period and Child Development: Findings on Developmental Timing, Mechanisms, and Intervention. Current psychiatry reports, 18(3), 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Monk C, & Fitelson EM (2014). Practitioner review: maternal mood in pregnancy and child development--implications for child psychology and psychiatry. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 55(2), 99–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peedicayil J (2007). The role of epigenetics in mental disorders. Indian J Med Res;126:105–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieretti M, Zhang FP, Fu YH, Warren ST, Oostra BA, Caskey CT, et al. (1991). Absence of expression of the FMR-1 gene in fragile X syndrome. Cell. 66(4):817–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptak C, & Petronis A (2010). Epigenetic approaches to psychiatric disorders. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 12(1), 25–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugliese V, Bruni A, Carbone EA, Calabrò G, Cerminara G, Sampogna G, et al. (2019). Maternal stress, prenatal medical illnesses and obstetric complications: Risk factors for schizophrenia spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Psychiatry research, 271, 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn JJ, & Chang HY (2016). Unique features of long non-coding RNA biogenesis and function. Nature reviews. Genetics, 17(1), 47–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai K, Huggins IJ, James SR, Karpf AR, Jones DA, & Cairns BR (2008). DNA demethylation in zebrafish involves the coupling of a deaminase, a glycosylase, and gadd45. Cell, 135(7), 1201–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramborger ME, Zubilete MAZ, and Acosta GB (2018). Prenatal Stress and its effects of human cognition, behavior and psychopathology: A review of the literature Pediatr Dimensions 3(1): 1–6 [Google Scholar]

- Rangasamy S, D’Mello SR, Narayanan V. (2013). Epigenetics, autism spectrum, and neurodevelopmental disorders. Neurotherapeutics 10(4):742–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijlaarsdam J, van IJzendoorn MH, Verhulst FC, Jaddoe VW, Felix JF, Tiemeier H, et al. (2017). Prenatal stress exposure, oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) methylation, and child autistic traits: The moderating role of OXTR rs53576 genotype. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 10(3), 430–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J, Sareen J, Cox BJ, & Bolton J (2009). Self-medication of anxiety disorders with alcohol and drugs: Results from a nationally representative sample. Journal of anxiety disorders, 23(1), 38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronald A, Pennell CE, & Whitehouse AJ (2011). Prenatal Maternal Stress Associated with ADHD and Autistic Traits in early Childhood. Frontiers in psychology, 1, 223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth TL, Sweatt JD (2011). Annual Research Review: Epigenetic mechanisms and environmental shaping of the brain during sensitive periods of development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 52(4):398–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roundtree IA, Evans ME, Pan T, & He C (2017). Dynamic RNA Modifications in Gene Expression Regulation. Cell, 169(7), 1187–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salatino-Oliveira A, Rohde LA, & Hutz MH (2018). The dopamine transporter role in psychiatric phenotypes. American journal of medical genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric genetics: the official publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics, 177(2), 211–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinost D, Sinha R, Cross SN, Kwon SH, Sze G, Constable RT, & Ment LR (2017). Does prenatal stress alter the developing connectome?. Pediatric research, 81(1–2), 214–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Bunkner JD, Keough ME. (2007). Anxiety sensitivity as a prospective predictor of alcohol use disorders. Behav Modif.;31:202–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder M, Krebs MO, Bleich S, Frieling H. (2010). Epigenetics and depression: current challenges and new therapeutic options. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 23(6):588–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, & Hesselbrock V (1994). Alcohol dependence and anxiety disorders: what is the relationship? The American journal of psychiatry, 151(12), 1723–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selbach M, Schwanhäusser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, & Rajewsky N (2008). Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature, 455(7209), 58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selten JP, Brown AS, Moons KG, Slaets JP, Susser ES, Kahn RS. (1999). Prenatal exposure to the 1957 influenza pandemic and non-affective psychosis in The Netherlands. Schizophr Res.;38(2–3):85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selten JP, van der Graaf Y, van Duursen R, Gispen-de Wied CC, Kahn RS. (1999). Psychotic illness after prenatal exposure to the 1953 Dutch Flood Disaster. Schizophr Res.;35(3):243–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]