Abstract

Objective:

To assess the prevalence and to identify the associated factors of malnutrition among elderly Chinese with physical functional dependency.

Design:

Face-to-face interviews using standardised questionnaires were conducted to collect demographic information, health-related issues and psychosocial status. Physical function was measured by the Barthel Index (BI), and nutrition status was assessed by the Mini Nutritional Assessment–Short Form. Multivariate binary logistic regression was used to assess associated factors of malnutrition.

Setting:

China.

Participants:

A total of 2323 participants (aged ≥ 60 years) with physical functional dependency in five provinces in China were enrolled using a multistage cluster sampling scheme.

Results:

The prevalence of malnutrition was 17·9 % (95 % CI 16·3, 19·4). Multivariable binary logistic regression revealed the independent risk factors of poor nutrition status were being female, older age, lower educational status, poor hearing, poor physical functional status, lack of hobbies, low religious participation, poor social support, lack of social participation and changes in social participation. The study found that the most significant independent risk factor for malnutrition was complete physical functional dependence (OR 4·46, 95 % CI 2·92, 6·82).

Conclusions:

The findings of the study confirm that malnutrition and the risk of malnutrition are prevalent in Chinese older adults with physical functional dependency. In addition to demographic and physical health-related factors, psychosocial factors, which are often overlooked, are independently associated with nutrition status in Chinese older adults with physical functional dependency. A holistic approach should be adopted to screen for malnutrition and develop health promotion interventions in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Older adults, Malnutrition, Prevalence, Factors, Physical functional dependency

The aging population is rapidly increasing worldwide. From 2015 to 2050, the proportion of the world’s population who are aged ≥60 years is projected to nearly double, from 12 to 22 %(1). China has a large elderly population, and its pace of aging is much faster compared to other countries. Specifically, the China Research Center on Aging has reported that 202 million Chinese residents (approximately 15 % of the population) were >60 years of age in 2013(2). The number of Chinese older adults is expected to grow to 478 million (35·10 % of the population) by 2050(3).

Aging affects nearly every human body system and structure, which may consequently affect nutrition status. For instance, impaired taste, decreased sense of smell, missing teeth, ill-fitting dentures and swallowing problems are common health conditions associated with aging(4). These aging-related health conditions may directly or indirectly influence food choice, digestion, and the absorption and metabolism of nutrients and consequently lead to malnutrition(5). In turn, malnutrition in old age can accelerate one’s ‘rate of aging’(6).

Malnutrition can be defined as ‘a state resulting from lack of intake or uptake of nutrition that leads to altered body composition (decreased fat-free mass) and body cell mass leading to diminished physical and mental function and impaired clinical outcome from disease’(7). Previous studies have reported that malnutrition could result in serious health consequences, including but not limited to pressure ulcers, infection, falls, fractures, frailty and decreased psychological wellbeing (e.g. depression)(8,9). In addition, malnutrition is a strong and independent predictor of hospital admission, longer hospitalisation, higher morbidity and mortality rates, poor quality of life and increased healthcare expenditures(10–12).

The prevalence of malnutrition among Chinese older adults varies, depending on a variety of factors such as the nutrition assessment tool and the study population. The Chinese Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) has reported that 12·6 % of 6450 community-dwelling Chinese older adults from 448 different urban/rural communities in twenty-eight provinces were malnourished according to the European Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) criteria(9). Woo and colleagues have found that 26 % of older adults in the long-term care setting in Hong Kong city were malnourished, according to the standard WHO definition (BMI ≤18·5 kg/m2)(13). Regardless of the criteria adopted and which population was examined, malnutrition is a major public health concern for Chinese older adults.

The identified risk factors of malnutrition in Chinese older adults include demographics and health-related factors. For example, the second wave of the CHARLS has found that older age, gender, rural residents and lack of health insurance were associated with malnutrition(9). Indicators of health status such as poor cognitive function, poor self-rated health and gastrointestinal system disease are significant risk factors for poor nutrition status among the oldest-old Chinese (≥90 years of age)(14). Another study conducted in Wuhan, China, has found that marital status and functional status are associated with malnutrition(15). Psychosocial status, such as social participation and social support, which have been reported as important factors for nutrition status in older adults in western countries, have rarely been investigated in Chinese older adults(16).

In addition to the risk factors mentioned above, physical functional dependency, which is defined as the restricted ability to perform self-care abilities such as feeding, walking and bathing, has been highly correlated with malnutrition in the Asian older adult population(17). The Sixth National Census has reported that >5·22 million older adults have physical functional dependency in China(18). As the aging population increases in China, the number of older adults with physical functional dependency is expected to soar in the coming decades(19). Numerous studies have demonstrated that older adults with physical functional dependency are generally at a higher risk of malnutrition(20,21). In addition, improving nutrition can prevent progression to further physical function loss, increase length of independence and improve quality of life(22,23). Moreover, even very frail elders can benefit from improved nutrition(24,25). However, current knowledge on the prevalence of and risk factors for malnutrition in this vulnerable group is very limited. Examining the prevalence of malnutrition and determining the risk factors among older adults with physical functional dependency in China can broaden our understanding and advance our knowledge of nutrition status in this population, and help to identify strategies for prevention, management and treatment of malnutrition for this vulnerable group. Therefore, the objectives of this study were: (1) to assess the prevalence of malnutrition among older adults with physical functional dependency in a nationally representative sample; and (2) to identify the risk factors for malnutrition in this vulnerable population in China.

Methods

Sampling strategy

In China, the terms used to define administrative regions of the country have different meanings from the typical western definitions. China is divided into provinces (such as Hunan), autonomous regions (such as Tibet), municipalities (such as Beijing and Chongqing) and two Special Administration Regions (Hong Kong and Macau)(26). Each province has prefecture-level cities, which may contain both urban and rural areas and cover thousands of kilometres(27). Rural areas surrounding a city may fall under its authority.

A multistage cluster sampling scheme was conducted by the Xiangya-Oceanwide Health Management Research Institute, Central South University (XOHMRICSU). Firstly, five provinces/regions (Hunan, Tianjin, Chongqing, Fujian and Xinjiang) were randomly selected. Each of the five provinces/regions represents the southern, northern, central, eastern and western regions of China, respectively. Secondly, one prefecture-level city was randomly selected from each province/region. Thirdly, five communities (representing urban areas) and five villages (representing rural areas) from each prefecture-level city were selected using simple random sampling. Ultimately, a total of twenty-five communities (representing urban areas) and twenty-five villages (representing rural areas) were included in the study.

Study population

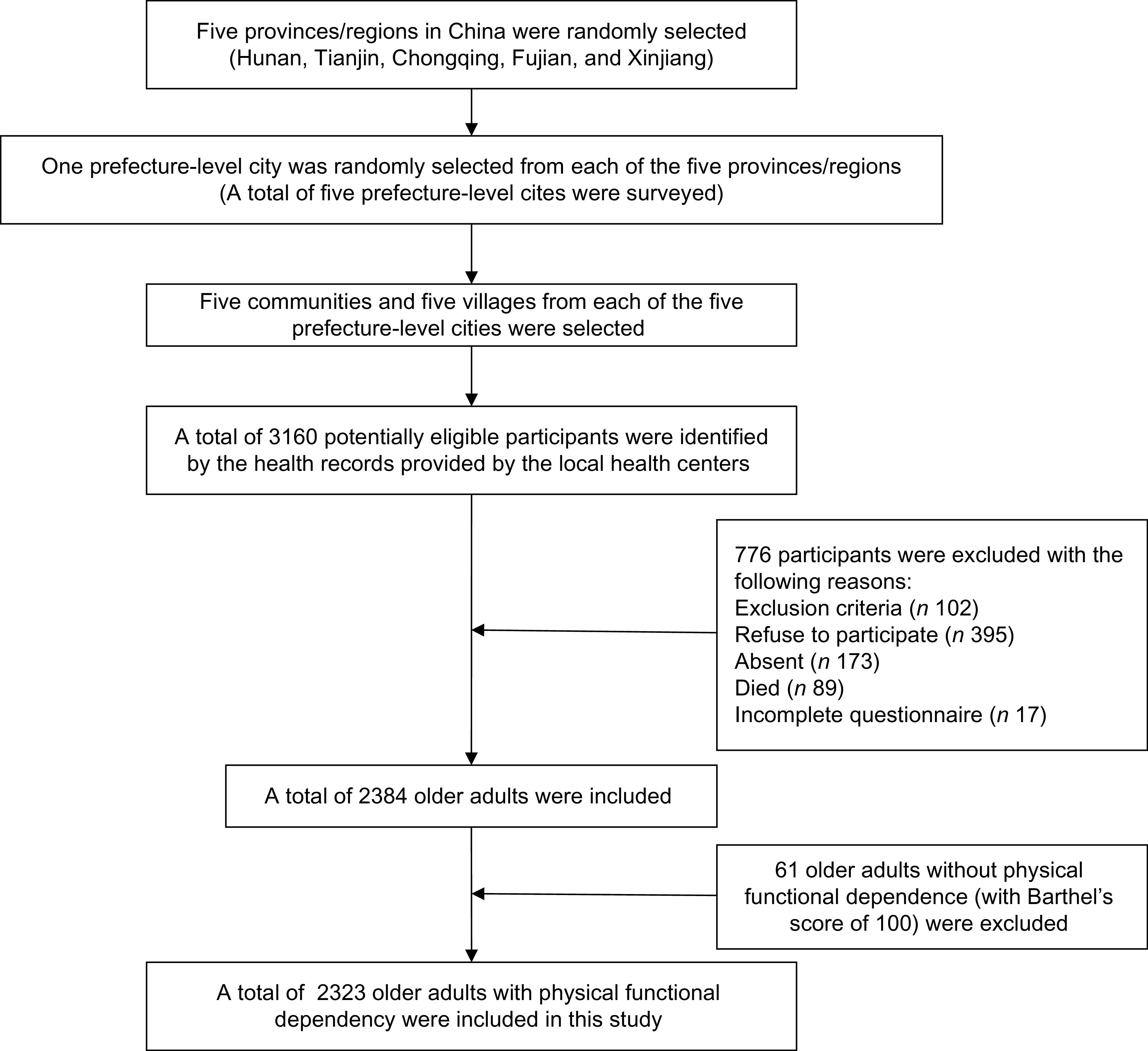

The inclusion criteria of the current study were older adults aged ≥60, as well as with physical functional limitations. Exclusion criteria were severe cognitive dysfunction, impaired verbal communication, acute psychosis, aphasia, an unstable medical illness and severe hearing impairment/inability to communicate. With the assistance of the local ministry of civil affairs, we obtained a list of adults aged ≥60 with documented physical functional limitations based on the health records provided by the local health service centres. Invitations were extended to all potential participants by poster, telephone call or other means by staff from the local health service centre. A total of 3160 potential participants were identified. One hundred and two subjects who met the exclusion criteria were excluded. Of the remainder, 395 refused to participate, 173 were unavailable for interviews and 89 died before the interview. For the remaining potential participants, we further assessed their functional status using the Barthel Index (BI). The data of sixty-one participants who were determined to be physically independent based on BI were removed from data analysis, as well as the data from seventeen incomplete questionnaires. The final sample consisted of 2323 older adults with physical functional dependency as measured by Barthel’s score <100. Figure 1 displays the selection processes of the target population.

Fig. 1.

Sampling process flowchart

Research design and data collection

In this cross-sectional study, face-to-face interviews using standardised questionnaires were conducted by graduate medical students, nurses and medical doctors who were trained in the data collection method at XOHMRICSU. All interviewers were provided with a specially designed interview handbook to ensure consistency in data collection. Senior researchers with extensive fieldwork experience from the University supervised the data collection process. Considering the inconvenience of travelling for older adults with physical functional dependency, all face-to-face interviews were conducted at the participants’ homes. For a majority of participants, interviewers read the questions one by one to the study participants, and filled in the survey with participants’ responses. A few participants preferred to complete the questionnaire by themselves with an interviewer present to clarify if needed. This research was approved by the Ethical Committee of Central South University. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. All participants received a small token of appreciation such as toothpaste or a towel for completing the interview.

Measurements

The survey questionnaire consisted of four sections: demographic information, measurements of nutrition status and physical function status, questions about health-related issues, and psychosocial status.

Health outcome

The health outcome, nutrition status, was measured by Mini Nutritional Assessment–Short Form (MNA-SF). MNA is a nutritional screening tool for older adults(28). It has been validated in Chinese elderly(29). The MNA-SF includes six items – food intake, weight loss, recent psychological stress or acute disease, dementia or depression, BMI and mobility – and has been validated with comparable diagnostic accuracy to the full version(30). The total score on the MNA-SF ranges from 0 to 14, with a score of 0–7 representing malnutrition, 8–11 representing at-risk of malnutrition and 12–14 representing normal nutrition status(30). In the current study, nutrition status was divided into two categories – normal (≥12 points) and poor nutrition status (including subjects with malnutrition (≤7 points) and those at-risk of malnutrition (8–11 points))(31) – for analysis.

Demographics

Demographic information included gender, age, marital status, type of residence (rural/urban), education level and occupation before the age of 60. Age was divided into different groups: 60–74 years (young-old), 75–89 years (old-old) and ≥90 years (the oldest-old)(32). Marital status was categorised as single (including unmarried, widowed and divorced) and married. Education was coded as primary school or less, middle school and high school or above. Occupation before the age of 60 was classified as public institutional staff, enterprise staff, farmer and other professions.

Health-related factors

Physical functional status was assessed by BI, which consists of ten items focusing on self-care abilities: feeding, bathing, dressing, grooming or personal hygiene, bowel continence, toilet use, bladder continence, walking, transfers and stair climbing(33). Good sensitivity, specificity and reliability for measuring physical functional status have been validated in the older adult population(34). The score of each item ranges from 0 to 15, and the total score ranges from 0 to 100. A sum of 0–20 represents complete dependence; 21–60, severe dependence; 61–90, moderate dependence; 91–99, slight dependence; and 100, complete independence(35). Other health-related factors were measured by self-reported hearing and vision status, oral health, history of falls, self-reported health status, history of chronic diseases and disability status.

Psychosocial factors

Psychosocial status was measured by self-report of hobbies, religious beliefs, social participation, changes in social participation over the past month and social support, which included emotional and material support. Examples of emotional support included having someone to communicate with when feeling lonely, having someone to talk with about any concerns and having someone who understands their problems. Examples of material support included sufficient financial support from children, family members or society; help with transportation, shopping, household tasks; or receiving help if confined to bed.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistics were calculated for all variables using SPSS, version 17.0. Descriptive statistics were used to describe categorical variables and continuous variables. Nutrition status was divided into two categories: normal and poor nutrition status (including both subjects with malnutrition and those at-risk of malnutrition)(31). Characteristics of the study population were compared by nutrition status for statistical significance using the χ 2 test. Multivariate binary regression was conducted to estimate the factors associated with poor nutrition status. OR with 95 % CI were estimated, and the entry and removal criteria for variables were 0·05 and 0·10. A P-value <0·05 was considered statistically significant.

As a variety of potential risk factors for malnutrition were included in the study, a test for multicollinearity was conducted. The results of the multicollinearity test showed that all variance inflation factors (VIF) for the independent variables were about 1·5, which indicated minimal correlation(36). The statistically significant χ 2 statistic (χ 2 = 563·24, P < 0·001) demonstrated an acceptable model fit. The accuracy of classification was 71·5 %. The goodness-of-fit tests (deviance test, Pearson test, Hosmer–Lemeshow test) were all greater than the significance level of 0·05, indicating a satisfactory goodness-of-fit test(37).

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 2323 older adults with physical functional dependency were included in this study. The average study participant was 79·16 (sd 8·93) years of age. Most of the participants were female (53·3 %), single (65·5 %), resided in urban areas (72 %) and educated at the primary school level or below (60·8 %). The mean MNA-SF score of the study population was 10·29 (sd 2·61). As defined by MNA-SF, 17·9 % (95 % CI 16·3, 19·4) of the sample were malnourished. A total of 60·1 % (95 % CI 58·1, 62·1) of the participants had poor nutrition status, and 39·9 % (95 % CI 37·9, 41·9) with normal nutrition status. Table 1 displays the relationships between participants’ demographic characteristics and their nutrition status. Nutrition status was significantly associated with the following demographic variables: gender, age group, residential setting, province/region of residence and occupation before the age of 60 (P < 0·05).

Table 1.

Associations of demographic characteristics with nutrition status†

| Variables | Nutrition status | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n 2323 (%) | Normal nutrition status (n 927, 39·9 %; 95 % CI 37·9, 41·9) | Poor nutrition status (n 1396, 60·1 %; 95 % CI 58·1, 62·1) | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 1086 | 46·7 | 474 | 43·6 | 612 | 56·4 | 0·028* |

| Female | 1237 | 53·3 | 453 | 36·6 | 784 | 63·4 | |

| Age group‡ | |||||||

| Young-old | 648 | 27·9 | 295 | 45·6 | 353 | 54·4 | 0·005** |

| Old-old | 1407 | 60·6 | 554 | 39·4 | 853 | 60·6 | |

| Oldest-old | 268 | 11·5 | 78 | 29·2 | 190 | 70·8 | |

| Marital status§ | |||||||

| Single | 1522 | 65·5 | 582 | 38·2 | 940 | 61·8 | 0·306 |

| Married | 801 | 34·5 | 345 | 43·1 | 456 | 56·9 | |

| Residential setting | |||||||

| Urban | 1672 | 72·0 | 628 | 37·5 | 1044 | 62·5 | <0·001*** |

| Rural | 651 | 28·0 | 299 | 45·9 | 352 | 54·1 | |

| Province/region of residence | |||||||

| Chongqing | 417 | 18·0 | 218 | 52·3 | 199 | 47·7 | <0·001*** |

| Xinjiang | 421 | 18·1 | 133 | 31·6 | 288 | 68·4 | |

| Fujian | 432 | 18·6 | 209 | 48·4 | 223 | 51·6 | |

| Hunan | 646 | 27·8 | 201 | 31·1 | 445 | 68·9 | |

| Tianjin | 407 | 17·5 | 166 | 40·8 | 241 | 59·2 | |

| Education level | |||||||

| Primary school or less | 1413 | 60·8 | 554 | 39·2 | 859 | 60·8 | 0·073 |

| Middle school | 436 | 18·8 | 176 | 40·3 | 260 | 59·7 | |

| High school or above | 474 | 20·4 | 197 | 41·6 | 277 | 58·4 | |

| Occupation before the age of 60 | |||||||

| Public institutional staff | 482 | 20·7 | 181 | 37·6 | 301 | 62·4 | <0·001*** |

| Farmer | 632 | 27·3 | 303 | 47·9 | 329 | 52·1 | |

| Enterprise staff | 995 | 42·8 | 373 | 37·5 | 622 | 62·5 | |

| Other professions | 214 | 9·2 | 70 | 32·7 | 144 | 67·3 | |

P-value for the χ2 test. Normal nutrition status (≥12 points); poor nutrition status (including subjects with malnutrition (≤7 points) and those at-risk of malnutrition (8–11 points)).

Young-old, 60–74 years; old-old, 75–89 years; oldest-old, ≥90 years.

Single = widowed/unmarried/divorced.

*P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·005.

Health-related characteristics

Table 2 displays the distribution of participants by different health status, and the proportion of participants with normal and poor nutrition status by different levels of health status. Over half of the participants (55·7 %) reported their health status as poor. Most participants reported impaired vision (81·5 %), impaired hearing (89·2 %) and poor oral health (81 %). Approximately 39·6 % of the participants had a history of falls over the past 2 months. More than half of the participants (53·1 %) suffered from two or more chronic diseases. According to the BI score, the prevalence of slight, moderate, severe and complete dependence was 7·9, 33·3, 32·8 and 26 %, respectively. The prevalence of poor nutrition status was 38·4 % for those with slight dependence, 47·2 % for moderate dependence, 58·8 % for severe dependence and 85·0 % for complete dependence. The χ 2 test indicated statistically significant differences between the nutrition status and the following health-related characteristics: self-reported health status, vision, hearing, history of falls over the past 2 months, disability status and physical functional status (P < 0·05).

Table 2.

Associations of health-related characteristics with nutrition status†

| Variables | Nutrition status | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n 2323 (%) | Normal nutrition status (n 927, 39·9 %) | Poor nutrition status (n 1396, 60·1 %) | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Self-reported health status | |||||||

| Good | 301 | 13·0 | 142 | 47·2 | 159 | 52·8 | <0·001*** |

| Fair | 726 | 31·3 | 342 | 47·1 | 384 | 52·9 | |

| Poor | 1296 | 55·7 | 443 | 34·2 | 853 | 65·8 | |

| Vision‡ | |||||||

| Normal | 403 | 17·3 | 215 | 53·3 | 188 | 46·7 | <0·001*** |

| Impaired | 1894 | 81·5 | 704 | 37·2 | 1190 | 62·8 | |

| Poor | 26 | 1·2 | 8 | 30·8 | 18 | 69·2 | |

| Hearing§ | |||||||

| Normal | 227 | 9·8 | 127 | 55·9 | 100 | 44·1 | <0·001*** |

| Impaired | 2073 | 89·2 | 795 | 38·4 | 1278 | 61·6 | |

| Poor | 23 | 1·0 | 5 | 21·7 | 18 | 78·3 | |

| Oral health‖ | |||||||

| Normal | 442 | 19·0 | 190 | 43·0 | 252 | 57 | 0·054 |

| Poor | 1881 | 81·0 | 737 | 39·2 | 1144 | 60·8 | |

| History of falls over the past 2 months | |||||||

| No | 1403 | 60·4 | 548 | 39·1 | 855 | 60·9 | 0·006** |

| Yes | 920 | 39·6 | 379 | 41·2 | 541 | 58·8 | |

| History of chronic diseases¶| | |||||||

| No (0–1) | 1089 | 46·9 | 451 | 41·4 | 638 | 58·6 | 0·481 |

| Yes (≥2) | 1234 | 53·1 | 476 | 38·6 | 758 | 61·4 | |

| Disability status†† | |||||||

| No | 2242 | 96·5 | 894 | 39·9 | 1348 | 60·1 | <0·001*** |

| Yes | 81 | 3·5 | 33 | 40·7 | 48 | 59·3 | |

| Physical functional status | |||||||

| Slight dependence | 183 | 7·9 | 113 | 61·7 | 70 | 38·4 | <0·001*** |

| Moderate dependence | 775 | 33·3 | 409 | 52·8 | 366 | 47·2 | |

| Severe dependence | 762 | 32·8 | 314 | 41·2 | 448 | 58·8 | |

| Complete dependence | 603 | 26·0 | 91 | 15·0 | 512 | 85·0 | |

Normal nutrition status (≥12 points); poor nutrition status (including subjects with malnutrition (≤7 points) and those at-risk of malnutrition (8–11 points)).

Vision was assessed with or without glasses or contact lens.

Hearing was assessed with or without a hearing aid.

Poor oral health = missing teeth, mouth ulcers, difficulty chewing, no chewing ability.

History of chronic diseases = diagnosed with chronic diseases like diabetes, high BP, heart disease, etc.

Disability status = possesses a disability certificate of inability to work due to a dependence, issued by the Labour and Social Security Bureau.

*P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·005. P-value for the χ 2 test.

Psychosocial characteristics

For psychosocial factors (Table 3), an approximately half (51·9 %) of the participants reported having a hobby. More than half (65·3 %) of the participants reported never being involved in social activities. A majority of the participants (71·9 %) had no change in social participation over the past month. Most of the participants (93·8 %) did not have a specific religious belief. A large number of participants (72·4 %) felt they did not receive sufficient emotional and material support. Nutrition status was significantly associated with all psychosocial variables included in this study (P < 0·05).

Table 3.

Associations of psychosocial characteristics with nutrition status†

| Variables | Nutrition status | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n 2323 | Normal nutrition status (n 927, 39·9 %) | Poor nutrition status (n 1396, 60·1 %) | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Hobbies‡ | |||||||

| No | 1117 | 48·1 | 267 | 23·9 | 850 | 76·1 | <0·001*** |

| Yes | 1206 | 51·9 | 660 | 54·7 | 546 | 45·3 | |

| Religious beliefs | |||||||

| No | 2180 | 93·8 | 889 | 40·8 | 1291 | 59·2 | 0·003*** |

| Yes | 143 | 6·2 | 38 | 26·6 | 105 | 73·4 | |

| Social support | |||||||

| Insufficient emotional and material support | 1682 | 72·4 | 655 | 38·9 | 1027 | 61·1 | <0·001*** |

| Only get material support | 226 | 9·7 | 84 | 37·2 | 142 | 62·8 | |

| Only get emotional support | 47 | 2·0 | 18 | 38·3 | 29 | 61·7 | |

| Enough emotional and material support | 368 | 15·9 | 170 | 46·2 | 198 | 53·8 | |

| Social participation§ | |||||||

| Initiative and active participation | 101 | 4·3 | 58 | 57·5 | 43 | 42·5 | <0·001*** |

| Often | 138 | 5·9 | 91 | 65·9 | 47 | 34·1 | |

| Occasionally | 566 | 24·5 | 317 | 56·0 | 249 | 44·0 | |

| Never | 1518 | 65·3 | 461 | 30·4 | 1057 | 69·6 | |

| Change in social participation over the past month | |||||||

| No change | 1671 | 71·9 | 748 | 44·8 | 923 | 55·2 | 0·03* |

| Lower but not depressed | 365 | 15·7 | 106 | 29·0 | 259 | 71·0 | |

| Lower and feel depressed | 287 | 12·4 | 73 | 25·4 | 214 | 74·6 | |

Normal nutrition status (≥12 points); poor nutrition status (including subjects with malnutrition (≤7 points) and those at-risk of malnutrition (8–11 points)).

Hobbies included singing, walking, jogging, Beijing opera, square dancing, chess, etc.

Social participation included volunteer activities, community events or club meetings.

*P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·005. P-value for the χ 2 test.

Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis

Table 4 shows that the independent risk factors for poor nutrition status were female gender, the oldest-old, impaired hearing status, poor physical functional status, having religious beliefs and changes in social participation over the past month. However, those with education up to high school or above, having hobbies, getting enough emotional and material support and actively participating in social activities were less likely to suffer from poor nutrition status compared to their counterparts.

Table 4.

Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis of factors associated with poor nutrition status

| Variables | OR | P-value | 95 % CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Gender (ref = male) | |||

| Female | 1·24 | 0·027* | 1·03, 1·51 |

| Age (ref = young-old)† | |||

| Oldest-old | 1·75 | 0·002** | 1·22, 2·50 |

| Old-old | 1·13 | 0·275 | 0·91, 1·42 |

| Education level (ref = primary school or under) | |||

| High school or above | 0·67 | 0·007** | 0·51, 0·90 |

| Middle school | 0·88 | 0·344 | 0·67, 1·15 |

| Health-related variables | |||

| Hearing (ref = normal)‡ | |||

| Poor | 1·62 | 0·431 | 0·49, 5·33 |

| Impaired | 1·67 | 0·002*** | 1·21, 2·30 |

| Physical functional status (ref = slight dependence) | |||

| Complete dependence | 4·46 | <0·001*** | 2·92, 6·82 |

| Severe dependence | 1·50 | 0·029* | 1·04, 2·17 |

| Moderate dependence | 1·08 | 0·664 | 0·76, 1·55 |

| Psychosocial variables | |||

| Hobbies (ref = no) | |||

| Yes | 0·48 | <0·001*** | 0·38, 0·59 |

| Religious beliefs (ref = no) | |||

| Yes | 2·47 | <0·001*** | 1·61, 3·78 |

| Social support (ref = insufficient emotional and material support) | |||

| Enough emotional and material support | 0·57 | <0·001*** | 0·43, 0·77 |

| Only get emotional support | 1·02 | 0·948 | 0·52, 2·00 |

| Only get material support | 0·77 | 0·128 | 0·55, 1·08 |

| Social participation (ref = never) | |||

| Initiative and active participation | 0·56 | 0·014* | 0·36, 0·89 |

| Often | 0·45 | <0·001*** | 0·30, 0·68 |

| Occasionally | 0·57 | <0·001*** | 0·50, 0·73 |

| Changes in social participation over the past month (ref = no reduction) | |||

| Lower and feel depressed | 3·69 | <0·001*** | 2·62, 5·20 |

| Lower but not depressed | 2·34 | <0·001*** | 1·76, 3·09 |

Young-old, 60–74 years; old-old, 75–89 years; oldest-old, ≥90 years.

Hearing was assessed with or without a hearing aid.

*P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·005.

The variables of marital status, occupation before the age of 60, residential setting, vision status, oral health, history of falls, self-reported health status, number of chronic diseases and holding an official disability certificate were not statistically significant risk factors for poor nutrition status.

Discussion

Prevalence of malnutrition

This is the first study to examine the prevalence of malnutrition and its associated factors in a nationally representative sample of elderly Chinese with physical functional dependency. As expected, the incidence of malnutrition in the current study (17·9) was higher compared to other national and regional studies conducted among the general older population in China. Wei et al.(9) have found that 12·6 % of older adults are malnourished in a national sample. Regional research conducted in Beijing(38), Guangzhou(39) and Dongguan(14) has found that 0·2–1·3 % of the samples are malnourished. There are four possible explanations for these differences. Firstly, the current study included a more specific sample-exclusively older adults with physical functional dependency, who might suffer from more health-related issues than the general older adult population(40). This study demonstrated that the most significant independent risk factor for poor nutrition status is the occurrence of complete physical functional dependency (OR 4·46, 95 % CI 2·92, 6·82), and the proportion of completely dependent participants was 26·0 % in this study. Therefore, limiting participants to older adults with physical functional dependency might be the most important reason for these differences. Secondly, the samples from Beijing, Guangzhou and Dongguan included older adults in urban areas only, but the participants in the current study were drawn from both rural and urban areas, as was the sample in the Wei et al. study. Thirdly, there were differences in age distribution between the studies. The age of sample in the four studies ranges from 60·00 to 71·42 years. This study sample included participants with an average age of 79·16 (sd 8·93) years. Fourthly, different economic levels may contribute to different nutrition status(41). More specifically, Beijing, Guangzhou and Dongguan are prosperous cities in China. This study examined a nationally representative population, and samples were collected from five provinces/regions in China (Fujian, Hunan, Xinjiang, Chongqing and Tianjin) with different economic levels.

This study also confirms the findings of previous studies that have revealed that poor nutrition status is prevalent among individuals with physical functional dependency. A study conducted in Hong Kong has reported that the rate of malnutrition was 26 % among older adults in the long-term care setting(13), while the present study found that 17·9 % were malnourished among community-dwelling older adults with physical functional dependency in China. The higher malnutrition prevalence in the Hong Kong cohort might be largely attributed to the fact that older adults living in long-term care settings tend to have worse health conditions and poorer nutrition status compared to community-dwelling older adults(42,43). A high proportion of participants with physical functional dependency (68·5 %) was also found in the Hong Kong cohort. This is obviously not a direct comparison, but it is clear that the rate of malnutrition is high in the older population with physical functional dependency in China.

Demographic characteristics

In accordance with previous studies on older adults, we found that female gender, older age and lower education level are risk factors for poor nutrition status(32). These demographic risk factors associated with poor nutrition status are theoretically irreversible, so particular attention should be paid to poorly educated females, especially in advanced age. Studies are needed to explore prevention and intervention programmes to improve nutrition in this group of the population.

Health-related characteristics

Poor hearing status and poor physical function are strongly associated with poor nutrition status. Vision and hearing impairments are common chronic conditions in older adults(44). In this study, 82·7 % of participants had impaired vision, and 90·2 % had hearing impairments, which is much higher compared to the general Chinese older adult population. Luo has found that 6·3 % of 250 752 Chinese older adults reported visual impairment, and 11·8 % reported hearing impairment(45). Vision and hearing impairments may create barriers to communication(46), reducing the ability to prepare a meal, walk and accomplish grocery shopping(47), which might consequently affect nutrition status. Therefore, vision and hearing assessment should be routine parts of screening for the risk of malnutrition. The early identification and treatment of vision and/or hearing might be strategies to postpone or prevent poor nutrition status. Furthermore, healthcare providers should encourage the use of assistive devices (glasses, hearing aids) when available to promote communication and nutritional intake, especially in older adults with physical functional dependency.

The finding that poor nutrition status is more prevalent in the older adults with physical functional dependency is consistent with the previous evidence(48). It is noteworthy that compared to older adults with slight physical dependency, the odds of poor nutrition status in those with complete physical dependency was 4·46, which demonstrates that the most significant independent risk factor for poor nutrition status might be the occurrence of complete physical functional dependence in this population. Previous studies have demonstrated that the inability to provide one’s own nourishment due to impaired mobility is one of the biggest contributors of malnutrition in older adults(49). Physical functional dependency often leads to social isolation, which may result in poor appetite and increase the probability of malnutrition(49). As poor nutrition status appears to be more prevalent among older adults with physical functional dependency, this population needs more attention. For example, regular nutritional screening of elderly people with physical functional dependency should be highlighted. Screening for malnutrition risk can easily be performed by using instruments like the ‘MNA-SF’ tool. Adequate help with eating and/or use of food utensils like good-grip-eating utensils (dedicated to making eating easier)(50) for those with physical functional dependency might improve food intake and nutrition status. The provision of physical functional rehabilitation programmes may also have a beneficial effect on nutrition status(13).

Psychosocial characteristics

The current study revealed that religious beliefs seem to render elderly people more vulnerable to poor nutrition status. This could be partly explained by the fact that the largest religion in China is Buddhism, and Buddhists have different eating habits from the general population. They are not allowed to eat meat, which might contribute to poor nutrition status when combined with other risk factors such as physical functional dependency(51).

Our results demonstrated that social support is significantly associated with a lower risk for poor nutrition status. A possible explanation is that the support provided by others might provide social contact and physical assistance to help them in maintaining and adhering to a proper diet. Though the aetiology is unclear, previous studies have also indicated the same trend, which reported social support as having beneficial effects for nutrition(52). Unfortunately, in the current study, 72·4 % of the participants reported having insufficient emotional and material support, while only 15·9 % of the participants got enough emotional and material support. These results might call attention to the unmet needs for screening of social support among older adults with physical functional dependency.

Social participation is one of the three dimensions recommended for active and healthy aging by the WHO policy framework(53). Such participation may have a positive effect on the quality of life. Therefore, the association between social participation and poor nutrition status was explored. The result is consistent with a Brazilian study(54), which has found that a lack of social participation and changes in social participation over the past month are risk factors for poor nutrition status among older adults. Similarly, the current study also suggests that hobbies have a positive effect on nutrition status. Having an active life can help enrich life, regulate life pressure and promote interaction with others(55). Having an active life may also help older adults feel fulfilled, avoid loneliness and social withdrawal, as well as have access to information about health promotion activities(56), which might indirectly reduce the risk of malnutrition. Although social participation and hobbies are important factors for older adults’ health, it is common that many caregivers, even the whole healthcare system, and the society in China only consider older adults’ physical needs(57). Psychosocial needs such as social participation and hobbies are easily overlooked(58). Thus, it is urgent for Chinese caregivers to receive professional training to understand the critical role of social participation in promoting health.

The current study has identified that all psychosocial factors in the current study are independently associated with nutrition status, which may be modifiable. Religious beliefs, insufficient social support, lack of hobbies, lack of social participation and changes in social participation over the past month are easily measurable predictors for poor nutrition status. Periodic and holistic screening of these issues during routine visits to the health centre could facilitate the implementation of strategies and treatments aimed at reducing malnutrition. Educating older adults and their families will also promote reducing the risk of malnutrition. Further studies are needed to verify the effects of interventions that reduce the negative impacts of religious beliefs, insufficient social support, lack of hobbies, lack of social participation and changes in social participation on the high incidence of poor nutrition status in older adults with physical functional dependency.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Firstly, although the sample size was large enough to make reliable estimates, the participants were limited to the elderly with physical functional dependency, so the results of this study might not be generalisable to all Chinese older adults. Similarly, the subjects were non-institutionalised community dwellers, which might limit the generalisability and application of the study results to older adults living in senior homes or institutions. However, because of the Chinese filial piety culture and the initial stages of institutional care development, institutional elder care in China is rare and usually limited to the so-called ‘Three No’s’ – people with no children, no income and no relatives, who are publicly supported welfare recipients(59). Approximately 1·5–2·0 % older adults live in senior homes or institutions in China in 2012(60). Secondly, because of the cross-sectional design of this study, causal relationships cannot be inferred. Thirdly, a history of chronic diseases was defined as formally diagnosed by a doctor; accordingly, the prevalence of chronic diseases may be underestimated especially in rural areas, since some older adults do not get regular physical examinations because of financial constraints. Similarly, the disability status was limited to those with a disability certificate issued by the government; therefore, the prevalence of disabilities may have been underestimated. Fourthly, some other potential predictors (e.g. dysphagia, cooking ability/challenges, etc.) of malnutrition were not measured in the survey. This omission might have introduced bias to the results. Fifthly, BI has not been validated in China; therefore, it might have caused classification bias of the physical functional status.

Conclusions

The prevalence of malnutrition among Chinese older adults with physical functional dependency is high; 17·9 % of the population surveyed experienced malnutrition, which warrants consideration and intervention. The significant risk factors for poor nutrition status include: demographic factors (females, older age, low educational level), health-related factors (poor hearing, physical functional dependency) and psychosocial factors (lack of hobbies, insufficient social support, lack of social participation, decrease in social participation). This study confirms the necessity to evaluate nutrition status in older adults with physical function dependency in order to identify and reduce related factors for poor nutrition status. More importantly, poor nutrition status is strongly associated with psychosocial factors. These significant factors, which are often overlooked in Chinese culture, should be emphasised when conducting malnutrition prevention or intervention programmes.

In summary, the nutrition status in this population was determined by one’s biological (e.g. physical function status), psychosocial (e.g. education, social support) and spiritual aspects (e.g. religious belief). A holistic approach, which recognises and values a person as a whole and acknowledges the importance of the biological, psychological and spiritual factors to one’s health outcomes, should be adopted to screen for malnutrition and develop health promotion interventions in this vulnerable population.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: Y.D. is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through grant TL1 TR002647. We thank James A, Wiley, a statistician from University of California, San Francisco, Institute of Health Policy Studies, for his help with the statistical work in the manuscript. Financial support: This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (H.F., grant number 16BSH055) and the National Institutes of Health (H.-W.D., grant numbers R01AR069055-01A1 and U19AG055373-01). Authorship: H.N. formulated the research question, collected data, performed statistical analyses and wrote the paper. Y.D. performed statistical analyses, contributed to revising the article. D.E. and H.-W.D. contributed to revising the article. H.H. helped to plan the study, including the instrumentation. Y.Z., H.C., L.L. and M.L. collected data. L.P. supervised the data analysis. H.F. planned the study and supervised the data analysis. Conflict of interest: None. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the Ethical Committee of Central South University. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (2015) World Report on Ageing and Health. https://www.who.int/ageing/publications/world-report-2015/en/ (accessed July 2019).

- 2. Wang X-Q & Chen P-J (2014) Population ageing challenges health care in China. The Lancet 383, 870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. United Nations (2017) World Population Prospects 2017. https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed July 2019).

- 4. Posthauer ME, Dorner B & Friedrich EK (2014) Enteral nutrition for older adults in healthcare communities. Nutr Clin Pract 29, 445–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smeets PA, Erkner A & De Graaf C (2010) Cephalic phase responses and appetite. Nutr Rev 68, 643–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mann J & Truswell S (2017) Essentials of Human Nutrition. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cederholm T, Barazzoni R, Austin P et al. (2017) ESPEN guidelines on definitions and terminology of clinical nutrition. Clin Nutr 36, 49–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dent E, Visvanathan R, Piantadosi C et al. (2012) Nutritional screening tools as predictors of mortality, functional decline, and move to higher level care in older people: a systematic review. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr 31, 97–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wei J-M, Li S, Claytor L et al. (2018) Prevalence and predictors of malnutrition in elderly Chinese adults: results from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Public Health Nutr 21, 3129–3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Klek S (2013) Malnutrition and its impact on cost of hospitalization, length of stay, readmission and 3-year mortality – letter to the editor. Clin Nutr 32, 488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crogan NL & Pasvogel A (2003) The influence of protein-calorie malnutrition on quality of life in nursing homes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 58, 159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barker LA, Gout BS & Crowe TC (2011) Hospital malnutrition: prevalence, identification and impact on patients and the healthcare system. Int J Environ Res Public Health 8, 514–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Woo J, Chi I, Hui E et al. (2005) Low staffing level is associated with malnutrition in long-term residential care homes. Eur J Clin Nutr 59, 474–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lin WQ, Wang HHX, Yuan LX et al. (2017) The unhealthy lifestyle factors associated with an increased risk of poor nutrition among the elderly population in China. J Nutr Health Aging 21, 943–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Han Y, Li S & Zheng Y (2009) Predictors of nutritional status among community-dwelling older adults in Wuhan, China. Public Health Nutr 12, 1189–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pieroth R, Radler DR, Guenther PM et al. (2017) The relationship between social support and diet quality in middle-aged and older adults in the United States. J Acad Nutr Diet 117, 1272–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koo YX, Kang ML, Auyong A et al. (2014) Malnutrition in older adults on financial assistance in an urban Asian country: a mixed methods study. Public Health Nutr 17, 2834–2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. China NBoSoPsRo (2010) Sixth National Census Report. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/pcsj/rkpc/6rp/indexch.htm (accessed February 2019).

- 19. World Health Organization (2015) China Country Assessment Report on Ageing and Health. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/194271 (accessed July 2019).

- 20. Groce N, Challenger E, Berman-Bieler R et al. (2014) Malnutrition and disability: unexplored opportunities for collaboration. Paediatr Int Child Health 34, 308–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tramontano A, Veronese N, Giantin V et al. (2016) Nutritional status, physical performance and disability in the elderly of the Peruvian Andes. Aging Clin Exp Res 28, 1195–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hiramatsu M, Momoki C, Oide Y et al. (2019) Association between risk factors and intensive nutritional intervention outcomes in elderly individuals. J Clin Med Res 11, 472–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Drewnowski A & Evans WJ (2001) Nutrition, physical activity, and quality of life in older adults: summary. J Gerontol 56, 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Qiu Y, You J, Lv Q et al. (2019) Effect of whole-course nutrition management on patients with esophageal cancer undergoing concurrent chemoradiotherapy: a randomized control trial. Nutrition 69, 110558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Laviano A, Di Lazzaro L & Koverech A (2018) Nutrition support and clinical outcome in advanced cancer patients. Proc Nutr Soc 77, 388–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. ChinaToday.com (2005) Chinese Cities and Provinces. http://www.chinatoday.com/city/a.htm (accessed April 2019).

- 27. Shepard W (2016) China’s Cities Are Not Really as Big as They Seem. Forbes.com. https://www.forbes.com/sites/wadeshepard/2016/09/01/chinas-cities-are-not-really-as-big-as-they-seem/#530229bc4d24 (accessed April 2019).

- 28. Guigoz Y & Vellas BJ (1997) Malnutrition in the elderly: the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA). Ther Umsch 54, 345–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lei Z, Qingyi D, Feng G et al. (2009) Clinical study of mini-nutritional assessment for older Chinese inpatients. J Nutr Health Aging 13, 871–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rubenstein LZ, Harker JO, Salva A et al. (2001) Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56, M366–M372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Ramsch C et al. (2009) Validation of the Mini Nutritional Assessment short-form (MNA-SF): a practical tool for identification of nutritional status. J Nutr Health Aging 13, 782–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cherry KE, Hawley KS, Jackson EM et al. (2008) Pictorial superiority effects in oldest-old people. Memory 16, 728–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mahoney FI & Barthel D (1965) Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J 14, 56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Della Pietra GL, Savio K, Oddone E et al. (2011) Validity and reliability of the Barthel Index administered by telephone. Stroke 42, 2077–2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shah S, Vanclay F & Cooper B (1989) Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel Index for stroke rehabilitation. J Clin Epidemiol 42, 703–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schroeder MA (1990) Diagnosing and dealing with multicollinearity. West J Nurs Res 12, 175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hosmer DW, Hosmer T, Le Cessie S et al. (1997) A comparison of goodness-of-fit tests for the logistic regression model. Stat Med 16, 965–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li YCB, Guan SC & Zhang J (2012) Nutritional status and related factors of elderly people in Beijing community. Chin J Gerontol 2012, 4479–4481. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang XY, Lu XC, Li JY et al. (2015) Nutritional status of residents in Guangzhou community. Chin J Gerontol 7, 1958–1960. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R et al. (2011) Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev 10, 430–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Park M, Song JA, Lee M et al. (2018) National study of the nutritional status of Korean older adults with dementia who are living in long-term care settings. Jpn J Nurs Sci 15, 318–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Arandelovic A, Acampora A, Federico B et al. (2019) Factors associated with hospitalization before the start of long-term care among elderly disabled people. J Healthc Qual 41, 306–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cereda E, Pedrolli C, Klersy C et al. (2016) Nutritional status in older persons according to healthcare setting: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence data using MNA((R)). Clinical Nutr 35, 1282–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liljas AE, Wannamethee SG, Whincup PH et al. (2016) Socio-demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors and burden of morbidity associated with self-reported hearing and vision impairments in older British community-dwelling men: a cross-sectional study. J Public Health 38, e21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Luo Y, He P & Guo C (2018) Association between sensory impairment and dementia in older adults: evidence from China. J Am Geriatr Soc 66, 480–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Heine C & Browning CJ (2002) Communication and psychosocial consequences of sensory loss in older adults: overview and rehabilitation directions. Disabil Rehabil 24, 763–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mueller-Schotte S, Zuithoff NPA, van der Schouw YT et al. (2019) Trajectories of limitations in instrumental activities of daily living in frail older adults with vision, hearing, or dual sensory loss. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 74, 936–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kurkcu M, Meijer RI, Lonterman S et al. (2018) The association between nutritional status and frailty characteristics among geriatric outpatients. Clin Nutr ESPEN 23, 112–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cederholm T, Nouvenne A, Ticinesi A et al. (2014) The role of malnutrition in older persons with mobility limitations. Curr Pharm Des 20, 3173–3177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schiffman SS & Warwick ZS (1989) Use of flavor-amplified foods to improve nutritional status in elderly patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci 561, 267–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Phairin T & Kwanjaroensub V (2008) The nutritional status of patients admitted to Priest Hospital. J Med Ass Thai 91, Suppl. 1, S45–S48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McIntosh WA, Shifflett PA & Picou JS (1989) Social support, stressful events, strain, dietary intake, and the elderly. Med Care 27, 140–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Beard JR, Officer A, de Carvalho IA et al. (2016) The World report on ageing and health: a policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet 387, 2145–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Damiao R, Meneguci J, da Silva Santos A et al. (2018) Nutritional risk and quality of life in community-dwelling elderly: a cross-sectional study. J Nutr Health Aging 22, 111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lennartsson C & Silverstein M (2001) Does engagement with life enhance survival of elderly people in Sweden? The role of social and leisure activities. J Gerontol 56, S335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Umberson D & Montez JK (2010) Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav 51, Suppl., S54–S66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chen S, Zheng J, Chen C et al. (2018) Unmet needs of activities of daily living among a community-based sample of disabled elderly people in Eastern China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 18, 160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fu C, Li Z & Mao Z (2018) Association between social activities and cognitive function among the elderly in China: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15, 231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chen S (1996) Social Policy of the Economic State and Community Care in Chinese Culture: Aging, Family, Urban Change, and the Socialist Welfare Pluralism. Brookfield (VT): Avebury. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Feng Z, Liu C, Guan X et al. (2012). China’s rapidly aging population creates policy challenges in shaping a viable long-term care system. Health Aff 31, 2764–2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]