Abstract

Background:

Providing influenza vaccine to patients in the pediatric emergency department (PED) is one strategy to increase childhood influenza vaccine uptake. The Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines (PACV) survey is a new tool to identify vaccine-hesitant parents that may facilitate influenza vaccine uptake in the PED.

Objective:

To assess the feasibility of administering the PACV modified for influenza vaccination in the PED setting and to determine whether parental PACV scores are associated with patient receipt of influenza vaccine in the PED.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional study in the PED of a tertiary pediatric hospital in Seattle, WA during the 2013–2014 influenza season. English-speaking parents of children aged 6 months to 7 years who were afebrile, medically stable to be discharged home from the PED, and had not already received an influenza vaccine this season were administered a modified version of the PACV. PACV scores (0–100, higher score = higher hesitancy) were dichotomized (<50 and ≥50) consistent with previous validation studies. Feasibility was assessed by determining time to complete the PACV. Our primary outcome was influenza vaccine refusal in the PED. We used multivariable logistic regression to estimate unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for association between vaccine refusal and dichotomized PACV scores.

Results:

152 parent participants were included in the analysis. The median time for administering the PACV was 7 min. The median PACV score was 28, with 74% scoring <50. Parents who scored ≥50 on the PACV had increased odds of refusing the influenza vaccine compared to parents who scored <50 (adjusted OR [95% CI]: 6.58 [2.03–21.38]).

Conclusion:

Administration of the PACV in the PED is feasible, and higher PACV scores in this setting are associated with increased influenza vaccine refusal.

Keywords: Vaccine hesitancy, Influenza vaccine, Children, Emergency department

1. Introduction

Influenza continues to cause significant childhood morbidity and mortality each year in the United States [1,2]. Several groups are at higher risk for influenza-related illness, including young children, children with chronic illnesses, and their household members [3]. However, childhood influenza vaccination rates remain low [2]. During the 2012–2013 influenza season, an estimated 58.3% of children ages 6 months to 17 years in Washington State were immunized against influenza [4].

The low rates of influenza vaccination and increased risk of sequelae in children garner interest in developing new strategies aimed at increasing childhood influenza vaccine uptake [5,6], including administration of the influenza vaccine in school [7], inpatient [8], and pediatric emergency department (PED) settings [9,10]. Although feasibility of an emergency department-based vaccination program has been demonstrated in adults [11], several barriers remain to improving influenza vaccine uptake by administering it in a PED setting. Provider-level barriers include vaccines not being a traditional focus of discussion during PED visits [12]. As such, PED providers may not always be attuned to or able to recognize and address parental vaccine concerns or hesitancy leading to vaccine refusal. System-level barriers include the lack of time available to identify and address parental vaccine concerns given the need to prioritize more urgent medical issues during the PED visit [12,13]. Parental-level barriers include hesitancy toward vaccines and specific concerns regarding the influenza vaccine. Not only does vaccine hesitancy appear to be increasing generally [14,15], but parents who said they would refuse the influenza vaccine if it were offered in the PED reported vaccine safety concerns as the primary reason for their decision [16].

The Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines (PACV) survey is a 15-item, parent-report measure shown to be a valid and reliable tool for identifying parents who are hesitant toward the primary series of childhood vaccines [17–19]. Responses to individual items on the PACV may also identify the specific vaccine concerns of hesitant parents. Incorporation of a valid, modified version of the PACV could help to overcome system- and provider-level barriers to administering the influenza vaccine in the PED setting. The objectives of this study were to assess the feasibility of administering the PACV modified for influenza vaccination in a PED setting and to determine whether parental PACV scores were associated with receipt of seasonal influenza vaccine.

2. Methods

2.1. Setting and sample

We conducted a cross-sectional study in the PED of an urban, tertiary pediatric hospital in Seattle, WA with approximately 39,000 annual patient visits. Beginning with the 2008–2009 influenza season, this hospital implemented an electronic screening program that identified patients hospital-wide who may be eligible for the seasonal influenza vaccine and prompted providers to offer the vaccine to eligible patients through a notification in the patient’s electronic health record. In the PED setting, this automated electronic screening program deemed patients potentially eligible to receive the influenza vaccine if they were ≥6 months of age at the time of their PED visit and if parents reported during initial PED triage that their child had not yet received an influenza vaccine during the current influenza season. As part of standard PED care, any patient flagged as potentially eligible via the automated screening program would be approached by a RN during their PED visit and offered the influenza vaccine if the patient was afebrile and would be discharged home.

Parents of children who met the PED influenza program eligibility criteria were eligible to participate in the study from November 2013 to April 2014. We excluded non-English speaking parents since the PACV has not yet been validated in languages other than English, as well as parents of children >7 years old. The PACV has only been validated with parents of younger children and therefore may not accurately reflect the childhood vaccine beliefs and attitudes of parents of older children and adolescents. If a parent visited the PED with multiple eligible children, the parent was asked to participate with their youngest child in mind. Parents were not eligible to participate in the study more than once.

2.2. Data collection

A study team member who was not affiliated with the child’s care approached eligible parents after they had been triaged and moved to a private exam room in the PED and after they had been asked by their RN whether or not they would like their child vaccinated against influenza during their PED visit. We approached parents after their discussion with the PED RN in order to avoid biasing parental vaccine decision-making. Study team members were not blinded to the parent’s decision about whether or not to accept the influenza vaccine.

After obtaining verbal consent from the child’s parent, we administered the PACV survey to the parent in the child’s PED exam room. The PACV contains 15 items under 3 domains: vaccine behavior, beliefs about vaccine safety and efficacy, and general attitudes and trust. Response formats on the PACV are varied and include dichotomous replies, 5-point Likert scales, and 11-point scales. We modified some survey items for use in the PED setting and the influenza vaccine. For example, the item “Have you ever delayed having your child get a shot (not including seasonal flu or swine flu (H1N1) shots) for reasons other than illness or allergy?” was modified to read “Have you ever delayed having your child get a shot for reasons other than illness or allergy?”, and the item “I am able to openly discuss my concerns about shots with my child’s doctor.” was modified to read “I am able to openly discuss my concerns about shots with my child’s Emergency Room providers.” (Table 2). In order to maintain the validity of the original instrument and its scoring system, modifications were limited to minor word changes and additional survey items were not added. Lastly, although the PACV instrument was designed to be self-administered, we administered it verbally to increase our response rate and to mirror the potential future use of the PACV during patient triage in the acute care setting.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics and likelhood of influenza vaccine refusal.

| Parent demographics | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Parent age ≥30 years (ref = 18–29) | 1.7 (0.8–3.3) | 0.16 |

| ≤High school graduate, GED education (ref = some college, ≥2 year degree) | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) | 0.02 |

| Income >$75,000 (ref = ≤$75,000) | 1.5 (0.7–3.1) | 0.32 |

| Private insurance (ref = public) | 1.9 (0.9–3.9) | 0.07 |

| Single, separated or divorced (ref = married or living with partner) | 0.6 (0.3–1.3) | 0.20 |

| Parent = father (ref = mother) | 0.8 (0.4–1.8) | 0.62 |

| ≥2 children (ref = 1) | 0.9 (0.4–1.8) | 0.67 |

| Patient is firstborn child | 1.6 (0.8–3.1) | 0.18 |

| Race (ref = White) | ||

| Black or African American | 1.1 (0.4–3.3) | 0.80 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) | 0.00 |

| Asian | 1.0 (0.2–5.6) | 0.99 |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0.4 (0.0–6.7) | 0.53 |

| Mixed race | 0.6 (0.2–2.0) | 0.37 |

| Child age (ref = 6–<12 mos) | ||

| 1–2 years | 0.6 (0.2–1.8) | 0.34 |

| 3–5 years | 0.9 (0.3–2.7) | 0.85 |

| 6–7 years | 1.0 (0.3–3.5) | 0.98 |

| Higher acuity score at triage by ED staff (1 point difference) | 2.0 (1.2–3.6) | 0.01 |

| Higher acuity score selected by parent (1 point difference) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 0.45 |

Sociodemographic information was collected verbally from participants, including parental age, relationship to patient, marital status, education level, household income range, race/ethnicity, and number of children in the household. In addition, we asked parents to provide a self-rated acuity level for their child’s illness on a scale of 1–5, with 1 being the most acute. After the parent completed the survey, research staff determined how many minutes it took to complete the survey and abstracted from the medical record the child’s age in months, child’s insurance coverage status, whether or not the child received an influenza vaccine during their visit to the PED, and the child’s acuity rating. Acuity ratings at the study PED are assigned by medical staff (not physicians) at triage using the Emergency Severity Index (ESI), a five-level tool used to rate patient acuity, from level 1 (most urgent) to level 5 (least resource intensive) [20]. Data were collected using REDCap electronic data capturing software [21]. Parents were given a $5 gift card for their participation. This study was approved as exempt by the Western Institutional Review Board.

2.3. Data analysis

Consistent with prior analyses of the PACV, parental responses to each of the 15 PACV items were collapsed into three categories: hesitant, not sure, and non-hesitant responses [18]. For items with a 5-point Likert-scale ranging from ‘strongly agree to strongly disagree,’ the collapsed responses of either ‘strongly agree/agree’ or ‘strongly disagree/disagree,’ (depending on the valence of the question stem) were considered ‘hesitant’ responses. For items with a 5-point Likert-scale ranging from ‘not at all concerned to very concerned,’ the collapsed responses of ‘somewhat or very concerned’ were considered to be ‘hesitant’ responses, while responses of ‘not at all or not too concerned’ were considered to be ‘non-hesitant’ responses. For items with a yes/no response, we considered ‘yes’ to be the hesitant response and ‘no’ to be the non-hesitant response in all but one item (“If you had another infant today, would you want him/her to get all the recommended shots?”), where the reverse was true. For the items with an 11-point Likert-scale, we considered 0–5 to be ‘hesitant’ responses, 6–7 to be ‘not sure’ responses, and 8–10 to be ‘non-hesitant’ responses.

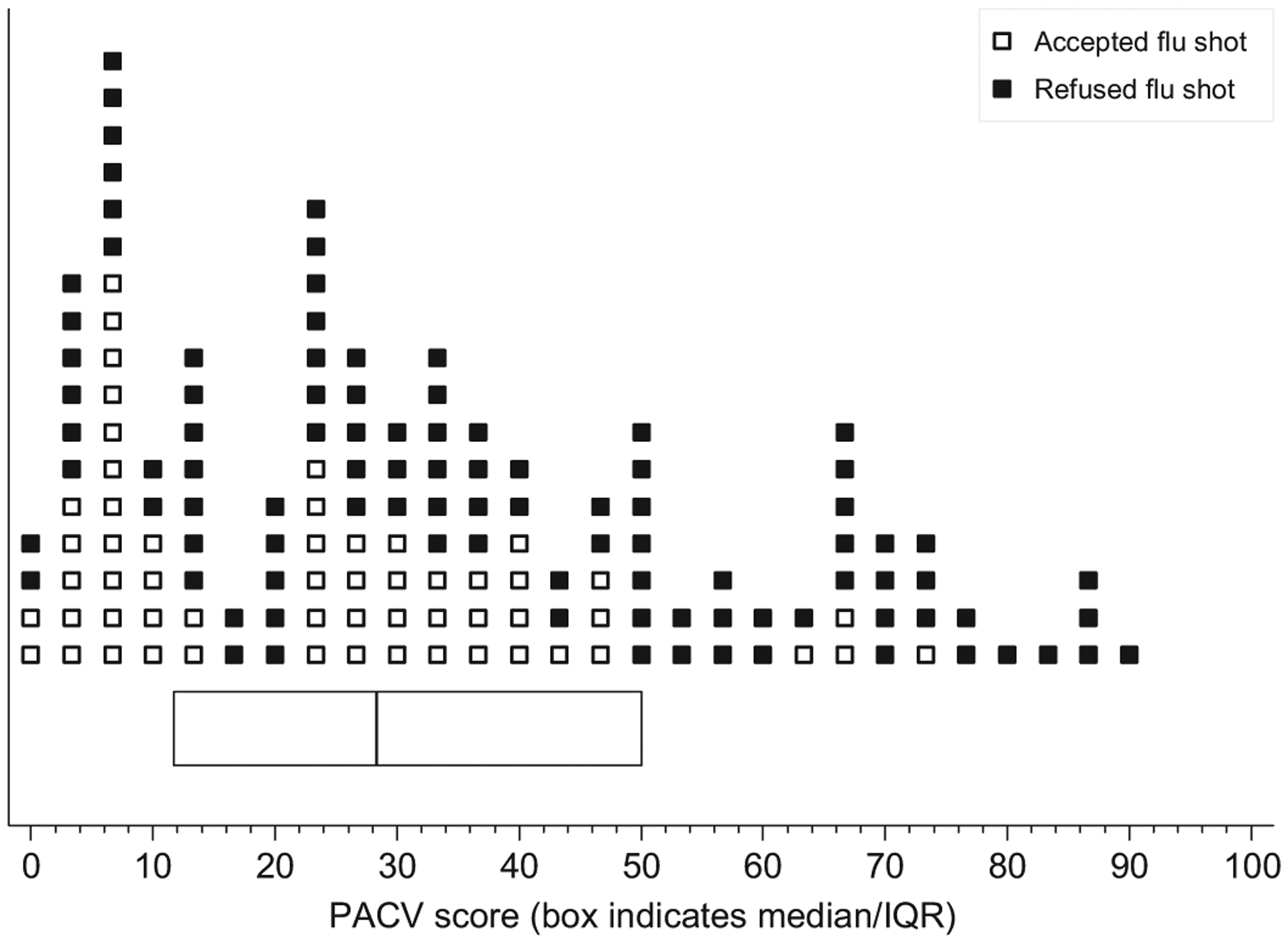

Responses were assigned a score of 2 for hesitant responses, 1 for not sure responses, and 0 for non-hesitant responses. Unweighted item scores were summed to calculate a raw score, and simple linear transformation was used to convert the raw score to a 0–100 point scale. We dichotomized PACV scores into two categories (<50 and ≥50) to be consistent with previous work [18,19] and because plots of percent of parents refusing influenza vaccine by score deciles confirmed that an inflection point occurred between deciles 40–49 and 50–59 (Fig. 1). The dichotomized PACV scores were used as the primary predictor variable in our analysis.

Fig. 1.

Refusal of influenza vaccine by PACV score. Each marker represents one participant.

Our primary study outcome was influenza vaccine refusal (yes/no) in the PED. We used descriptive statistics to summarize PACV scores and rate of vaccine refusal as well as individual PACV item responses, parent socio-demographics, child age and illness acuity, and time required to administer the PACV. We calculated 95% confidence intervals for the overall proportion of parents refusing the influenza vaccine as well as the proportion refusing in each score category, using the Wilson method [22]. We used bivariate and multivariable logistic regression models to estimate unadjusted (preliminary) and adjusted associations between vaccine refusal and dichotomized PACV score. Covariates included in the adjusted model included those identified a priori (child age) or found to be significant at the alpha = 0.1 level in exploratory bivariate models of vaccine refusal versus individual socio-demographic variables and acuity measures (Hispanic ethnicity, education level, insurance status, and medical staff acuity rating). We also used bivariate logistic regression models to estimate associations between vaccine refusal and individual PACV items. In exploratory post hoc analyses, we used bivariate logistic regression to assess relationships between dichotomized PACV score and individual socio-demographic and acuity measure variables. All testing was two-sided and conducted at the 0.05 level of significance. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 12 (StataCorp., College Station, TX).

3. Results

We enrolled 153 parent participants into the study. One participant was later excluded because their child was ineligible due to being febrile. Therefore, 152 participants were included in analysis. Of these 152 participants, 96 (63%; 95% CI: 55%–70%) refused the influenza vaccine when it was offered in the ED. The median time for administering the PACV was 7 min (IQR 5–9 min). The time required to administer the PACV ranged from 3 to 52 min, excluding one outlier.

3.1. Sample characteristics and survey results

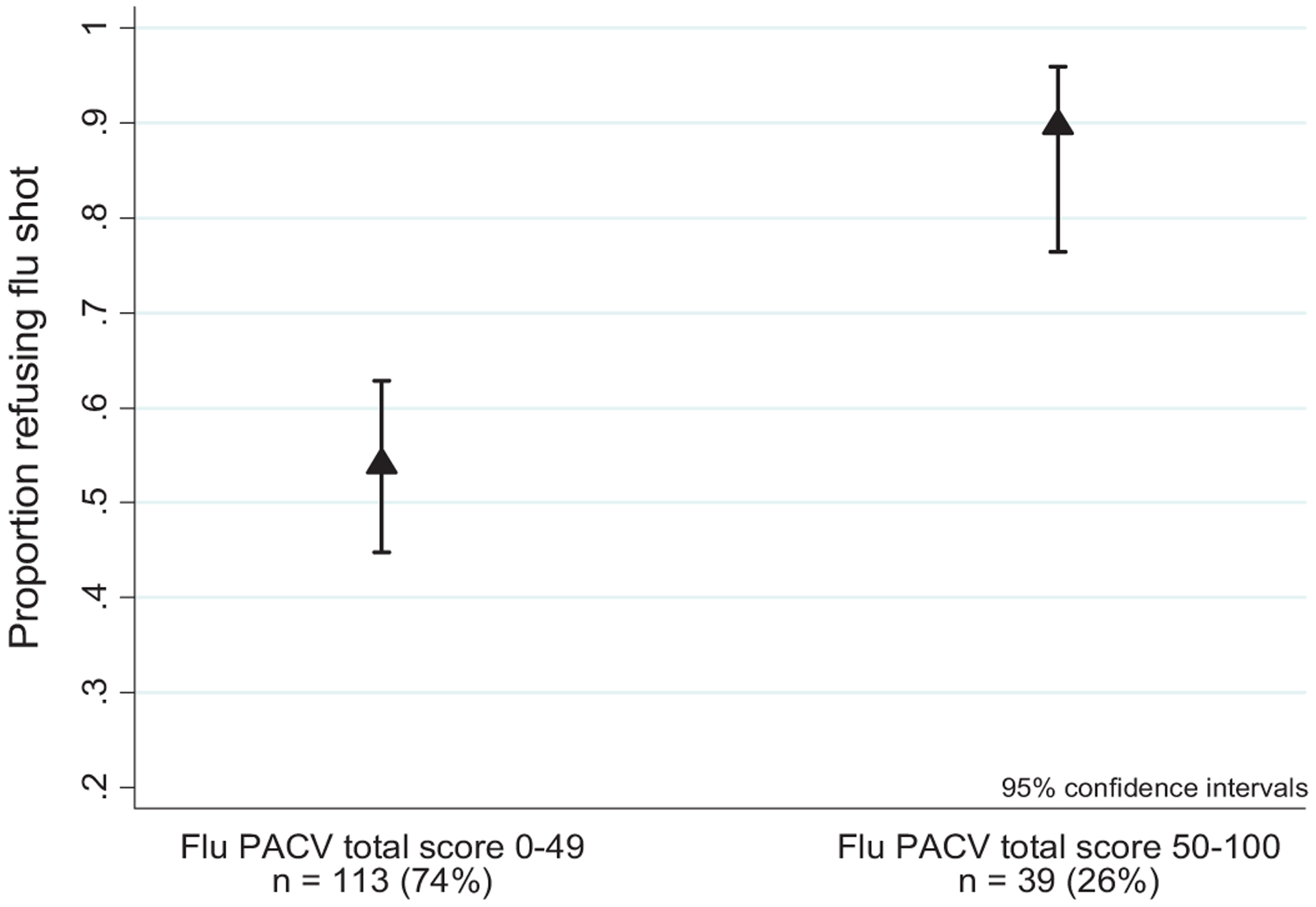

The majority of parent participants in our sample were of non-Hispanic White race (53%), over 30 years of age (68%), married (71%), had attended some college or more education (75%), and had a household income less than or equal to $75,000 (65%); just under half of the children had public insurance (49%) (Table 1). The median PACV score among participants was 28 (IQR 12–50) with 113 (74%) participants scoring <50 on the PACV. Among participants with PACV scores <50, 54% (95% CI: 45%–63%) refused the influenza vaccine, compared to 90% (95% CI: 76%–96%) of parents who scored ≥50 (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Demographics of study population (N = 152).

| Demographic characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Relationship to child | |

| Mother | 120 (79) |

| Parent age (years) | |

| ≥30 | 103 (68) |

| Parent’s marital status | |

| Single, separated, or divorced | 42 (28) |

| Married or living with a partner | 109 (71) |

| Parent education | |

| ≤High school graduate, GED | 38 (24) |

| Some college,≥2 year degree | 114 (75) |

| Household income | |

| ≤$75,000 | 98 (65) |

| >$75,000 | 45 (30) |

| Declined to answer | 9 (6) |

| Parent race/ethnicity | |

| White | 80 (53) |

| Black or African American | 23 (15) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 25 (16) |

| Asian | 7 (5) |

| Mixed race or Other | 17 (11) |

| Number of children in household | |

| 1 | 46 (30) |

| ≥2 | 106 (69) |

| Patient is first-born child | |

| Yes | 65 (43) |

| Insurance coverage | |

| Private | 62 (41) |

| Public | 75 (49) |

| Uninsured | 6 (4) |

| Other/Declined to answer | 9 (6) |

| Child age | |

| 6–<12 mos | 19 (13) |

| 1–2 years | 52 (34) |

| 3–5 years | 56 (37) |

| 6–7 years | 25 (16) |

| Child age, months: median (range) | 38 (6–94) |

| Acuity score at triage by ED staff | |

| 2 | 4 (3) |

| 3 | 91 (60) |

| 4 | 51 (34) |

| 5 | 6 (4) |

| Acuity score selected by parent | |

| 1 | 10 (7) |

| 2 | 19 (13) |

| 3 | 39 (26) |

| 4 | 43 (29) |

| 5 | 39 (26) |

| Total PACV score: median (IQR) | 28 (12–50) |

| Total PACV score category | |

| 0–49 | 113 (74) |

| 50–100 | 39 (26) |

| Parent refused influenza vaccine | 96 (63) |

| 95% confidence interval for proportion refusing vaccine | 0.55–0.70 |

Fig. 2.

Proportion of parents refusing influenza vaccine by dichotomized PACV total score.

Parents who had a high-school level education or less had decreased odds of refusing the influenza vaccine compared to parents with more than a high school education (odds ratio [OR] 0.4, 95% CI: 0.2–0.9) (Table 2). Parents whose children were rated by medical staff as having a higher acuity illness had increased odds of refusing the influenza vaccine compared to parents of children with lower acuity ratings (OR 2.0, 95% CI: 1.2–3.6). Also, Hispanic parents had lower odds of refusing the influenza vaccine than non-Hispanic White parents (OR 0.2, 95% CI: 0.1–0.6). We found no association between dichotomized PACV score and socio-demographic variables or acuity measures (data not shown).

3.2. Association of PACV items and scores with influenza receipt

In bivariate analyses, hesitant responses to eight of the 15 items on the PACV survey were significantly associated with refusal of the influenza vaccine (Table 3). Furthermore, parents with PACV scores ≥50 had increased odds of refusing the influenza vaccine compared to parents who scored <50 (Table 4). This remained true after adjusting for potential confounders.

Table 3.

Individual PACV item association with influenza vaccine refusal.

| Item no. | Flu PACV item | Responsea (shaded = hesitant) | Refused influenza vaccine? | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OR (95% CI)b | p-value | ||||

| No | Yes | |||||

| 1 | Have you ever delayed having your child get a shot for reasons other than illness or allergy? | Yes | 7 (17) | 35 (83) | 4.0 (1.6–9.8) | <0.01 |

| No | 49 (45) | 61 (55) | ||||

| Don’t know | Excluded as missing data | |||||

| 2 | Have you ever decided not to have your child get a shot for reasons other than illness or allergy? | Yes | 7 (16) | 37 (84) | 4.4 (1.8–10.7) | <0.01 |

| No | 49 (45) | 59 (55) | ||||

| Don’t know | Excluded as missing data | |||||

| 3 | How sure are you that following the recommended shot schedule is a good idea for your child? | 0–5c | 8 (17) | 39 (83) | 4.5 (1.9–10.9) | <0.01 |

| 8–10 | 42 (48) | 45 (52) | ||||

| 6–7 | 6 (33) | 12 (67) | 1.9 (0.6–5.4) | 0.25 | ||

| 4 | Children get more shots than are good for them.d | Agree | 17 (33) | 34 (67) | 1.6 (0.7–3.4) | 0.23 |

| Disagree | 28 (44) | 35 (56) | ||||

| Not sure | 11 (29) | 27 (71) | 2.0 (0.8–4.6) | 0.12 | ||

| 5 | I believe that many of the illnesses that shots prevent are severed | Disagree | 3 (30) | 7 (70) | 1.5 (0.4–6.2) | 0.55 |

| Agree | 50 (40) | 76 (60) | ||||

| Not sure | 3 (20) | 12 (80) | 2.6 (0.7–9.8) | 0.15 | ||

| 6 | It is better for my child to develop immunity by getting sick than to get a shot.d | Agree | 10 (25) | 30 (75) | 2.4 (1.0–5.6) | 0.04 |

| Disagree | 36 (44) | 45 (56) | ||||

| Not sure | 10 (34) | 19 (66) | 1.5 (0.6–3.7) | 0.35 | ||

| 7 | It is better for children to get fewer vaccines at the same time.d | Agree | 26 (30) | 61 (70) | 1.8 (0.7–4.2) | 0.21 |

| Disagree | 12 (43) | 16 (57) | ||||

| Not sure | 18 (49) | 19 (51) | 0.8 (0.3–2.1) | 0.64 | ||

| 8 | How concerned are you that your child might have a serious side effect from a shot?e | Concerned | 24 (32) | 51 (68) | 1.5 (0.8–3.0) | 0.21 |

| Not concerned | 29 (42) | 40 (58) | ||||

| Not sure | 3 (43) | 4 (57) | 1.0 (0.2–4.7) | 0.97 | ||

| 9 | How concerned are you that any one of the childhood shots might not be safe?e | Concerned | 18 (27) | 48 (73) | 1.9 (0.9–3.9) | 0.07 |

| Not concerned | 31 (42) | 43 (58) | ||||

| Not sure | 7 (58) | 5 (42) | 0.5 (0.1–1.8) | 0.29 | ||

| 10 | How concerned are you that a shot might not prevent the disease?e | Concerned | 23 (41) | 33 (59) | 0.8 (0.4–1.6) | 0.50 |

| Not concerned | 25 (35) | 46 (65) | ||||

| Not sure | 7 (29) | 17 (71) | 1.3 (0.5–3.6) | 0.59 | ||

| 11 | If you had another infant today, would you want him/her to get all the recommended shots? | No | 2 (7) | 25 (93) | 10.1 (2.3–44.8) | <0.01 |

| Yes | 51 (45) | 63 (55) | ||||

| Don’t know | 3 (27) | 8 (73) | 2.2 (0.5–8.6) | 0.27 | ||

| 12 | Overall, how hesitant about childhood shots would you consider yourself to be?f | Hesitant | 14 (24) | 44 (76) | 2.6 (1.2–5.4) | 0.01 |

| Not hesitant | 39 (45) | 47 (55) | ||||

| Not sure | 3 (38) | 5 (63) | 1.4 (0.3–6.2) | 0.67 | ||

| 13 | I trust the information I receive about shots.d | Disagree | 2 (13) | 14 (88) | 4.8 (1.0–22.4) | 0.04 |

| Agree | 45 (41) | 65 (59) | ||||

| Not sure | 9 (35) | 17 (65) | 1.3 (0.5–3.2) | 0.56 | ||

| 14 | I am able to openly discuss my concerns about shots with my child’s emergency room provider.d | Disagree | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | . |

| Agree | 54 (39) | 85 (61) | ||||

| Not sure | 1 (14) | 6 (86) | 3.8 (0.4–32.5) | 0.22 | ||

| 15 | All things considered, how much do you trust your child’s emergency room provider?g | 0–5 | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | |

| 8–10 | 54 (37) | 91 (63) | ||||

| 6–7 | 1 (20) | 4 (80) | 2.4 (0.3–21.8) | 0.44 | ||

Shaded responses are those hypothesized to reflect vaccine hesitancy.

Reference category for all odds ratios is not hesitant.

Response category on a 0–10 scale, with 0 being ‘not at all sure’ and 10 being ‘completely sure’.

“Agree” reflects combined responses of ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’; “disagree” reflects combined responses of ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘disagree’.

“Concerned” reflects combined responses of ‘very concerned’ and ‘somewhat concerned’; “not concerned” reflects combined responses of ‘not concerned at all’ and ‘not too concerned’.

“Hesitant” reflects combined responses of ‘very hesitant’ and ‘somewhat hesitant’; “not hesitant” reflects combined responses of ‘not hesitant at all’ and ‘not too hesitant’.

Response category on a 0–10 scale, with 0 being ‘do not trust at all’ and 10 being ‘completely trust’.

Table 4.

Association of overall PACV score with refusal of influenza vaccine.

| OR | 95% confidence interval | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PACV score 50–100 (vs. <50) | |||

| Bivariate (unadjusted) | 7.46 | (2.49, 22.38) | <0.01 |

| Multivariable (adjusted)a | 6.58 | (2.03, 21.38) | <0.01 |

Covariates include child age (6–<12 mos, 1–2 years, 3–5 years, 6–7 years), Hispanic race, ≤High school graduate or GED education, private insurance, acuity score at triage by ED staff.

4. Discussion

We determined that parental PACV scores ≥50, indicating vaccine hesitancy, were associated with increased odds of refusal of the influenza vaccine in the PED setting, consistent with previous validation studies of the PACV. Our data not only corroborate the PACV score threshold of ≥50 as consistent with a vaccine-hesitant parent who is more likely to under-immunize their child as a result of their hesitancy, but also provide evidence of the validity and feasibility of using the PACV in the PED setting. As such, the PACV may be a useful tool for identifying parents in the PED who are hesitant about the influenza vaccine.

Identification of parents who are hesitant about the influenza vaccine at the time of triage in the PED may have several benefits. First, documentation of this information in the patient’s chart may improve PED provider awareness of the parent’s vaccine concerns. Second, it can serve as a prompt to PED providers to discuss the parent’s vaccine concerns before discharge. Third, a parent’s specific responses on the PACV can yield insight regarding the primary reasons for their hesitancy. This knowledge can help PED providers use tailored information in their vaccine discussions with a parent. Although it remains an empirical question as to whether or not administration of the PACV will facilitate improved provider–parent vaccine discussions and increased influenza vaccination rates in the PED setting, our study provides the rationale for additional research to answer such questions.

It is interesting to note that the majority of parents in our sample refused the influenza vaccine, including many parents with PACV scores <50. This may indicate that other factors not measured as part of this study could affect a parent’s decision to accept the seasonal influenza vaccine in the PED. For instance, the provider–parent relationship is an important factor in parental vaccine decision-making [23–25]. Parents may prefer making the decision to vaccinate their child with their child’s primary care provider, with whom they have had a longer relationship and time to develop trust and understanding. In addition, parents may be overwhelmed with managing other more urgent medical issues during a PED visit, as suggested by the increased odds of refusal for more severe provider acuity ratings. More generally, this high refusal rate may also suggest that broad barriers to influenza vaccine acceptance still exist, such as perceived susceptibility, concerns about vaccine safety, and misinformation [16,26,27].

This study has several limitations. We only recruited parents presenting to a single PED and therefore our data may not be generalizable. Our study is also prone to selection bias, as we enrolled a convenience sample of parents, and to sampling bias, since study personnel were not blinded to the parent’s vaccination decision. We believe that the potential for sampling bias was minimal, however, since we used a standardized process for administering the PACV. Lastly, the study was limited by enrolling participants during five consecutive months of a single influenza season. In addition, we started enrolling participants in November, though the seasonal influenza vaccine had been available since September. A greater number of non-hesitant (vs. hesitant) parents could have already vaccinated their children by the start of our study, and therefore would not have been eligible to participate. Moreover, as time progressed, participants may have been more likely to refuse the influenza vaccine simply because it was later in the season and the perceived benefit of the influenza vaccine was lower than earlier in the season. However, in an exploratory analysis, we found no evidence of a time trend for vaccine refusal across the study enrollment period when separating PED visit date into quartiles.

5. Conclusions

The PACV appears to be a valid tool for determining parental hesitancy toward the seasonal influenza vaccine in a PED. Additional research is needed to assess the effect of administering the PACV in the PED on physician behavior and parental vaccine uptake.

Acknowledgments

Support for this study was provided by the Seattle Children’s Research Institute Center for Clinical and Translational Research Translational Research Ignition Projects Program. Additional support was provided by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (UL1TR000423 and UL1TR000002). The funders had no involvement in study design; the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

JAE received research support from Roche, Gilead, and Glaxo-SmithKline, and was a consultant to GlaxoSmithKline and Abbvie.

Abbreviations:

- PED

pediatric emergency department

- PACV

Parental Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines survey

References

- [1].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza—United States, 1976–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010;59:1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Poehling KA, Edwards KM, Griffin MR, Szilagyi PG, Staat MA, Iwane MK, et al. The burden of influenza in young children, 2004–2009. Pediatrics 2013;131:207–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Committee on Infectious Diseases American Academy of Pediatrics. Recommendations for prevention and control of influenza in children, 2012–2013. Pediatrics 2012;130:780–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC). Influenza vaccination coverage estimates by State, HHS Region, and the United States, National Immunization Survey (NIS) and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 2012–13 influenza season; 2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/reports/reporti1213/reportii/index.htm [accessed September 05].

- [5].Stinchfield PK. Practice-proven interventions to increase vaccination rates and broaden the immunization season. Am J Med 2008;121:S11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Briss PA, Rodewald LE, Hinman AR, Shefer AM, Strikas RA, Bernier RR, et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med 2000;18:97–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].King JC Jr, Stoddard JJ, Gaglani MJ, Moore KA, Magder L, McClure E, et al. Effectiveness of school-based influenza vaccination. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2523–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pollack AH, Kronman MP, Zhou C, Zerr DM. Automated screening of hospital-izedchildren for influenza vaccination. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2014;3:7–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hiller KM, Sullivan D. Influenza vaccination in the emergency department: are our patients at risk? J Emerg Med 2009;37:439–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pappano D, Humiston S, Goepp J. Efficacy of a pediatric emergency department-based influenza vaccination program. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004;158:1077–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rimple D, Weiss SJ, Brett M, Ernst AA. An emergency department-based vaccination program: overcoming the barriers for adults at high risk for vaccine-preventable diseases. Acad Emerg Med 2006;13:922–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Olson CM. Vaccination in pediatric emergency departments. JAMA 1993;270:2222–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wrenn K, Zeldin M, Miller O. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in the emergency department: is it feasible? J Gen Intern Med 1994;9:425–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dempsey AF, Schaffer S, Singer D, Butchart A, Davis M, Freed GL. Alternative vaccination schedule preferences among parents of young children. Pediatrics 2011;128:848–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Omer SB, Richards JL, Ward M, Bednarczyk RA. Vaccination policies and rates of exemption from immunization, 2005–2011. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1170–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Humiston SG, Lerner EB, Hepworth E, Blythe T, Goepp JG. Parent opinions about universal influenza vaccination for infants and toddlers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:108–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Taylor JA, Korfiatis C, Wiese C, Catz S, et al. Development of a survey to identify vaccine-hesitant parents: The parent attitudes about childhood vaccines survey. Hum Vaccin 2011;7:419–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Opel DJ, Taylor JA, Mangione-Smith R, Solomon C, Zhao C, Catz S, et al. Validity and reliability of a survey to identify vaccine-hesitant parents. Vaccine 2011;29:6598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Opel DJ, Taylor JA, Zhou C, Catz S, Myaing M, Mangione-Smith R. The relationship between parent attitudes about childhood vaccines survey scores and future child immunization status: a validation study. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167:1065–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wuerz RC, Travers D, Gilboy N, Eitel DR, Rosenau A, Yazhari R. Implementation and refinement of the emergency severity index. Acad Emerg Med 2001;8:170–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Brown LD, Cai TT, Dasgupta A. Interval estimation for a binomial proportion. Stat Sci 2001;2:101–33. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mergler MJ, Omer SB, Pan WK, Navar-Boggan AM, Orenstein W, Marcuse EK, et al. Association of vaccine-related attitudes and beliefs between parents and health care providers. Vaccine 2013;31:4591–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nowalk MP, Zimmerman RK, Lin CJ, Ko FS, Raymund M, Hoberman A, et al. Parental perspectives on influenza immunization of children aged 6 to 23 months. Am J Prev Med 2005;29:210–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Smith PJ, Kennedy AM, Wooten K, Gust DA, Pickering LK. Association between health care providers’ influence on parents who have concerns about vaccine safety and vaccination coverage. Pediatrics 2006;118:e1287–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bhat-Schelbert K, Lin CJ, Matambanadzo A, Hannibal K, Nowalk MP, Zimmerman RK. Barriers to and facilitators of child influenza vaccine – perspectives from parents, teens, marketing and healthcare professionals. Vaccine 2012;30:2448–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Offutt-Powell TN, Ojha RP, Qualls-Hampton R, Stonecipher S, Singh KP, Cardarelli KM. Parental risk perception and influenza vaccination of children in daycare centres. Epidemiol Infect 2014;142:134–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]