Abstract

This paper investigates the impacts of COVID-19 safer-at-home polices on collisions and pollution. We find that statewide safer-at-home policies lead to a 20% reduction in vehicular collisions and that the effect is entirely driven by less severe collisions. For pollution, we find particulate matter concentration levels approximately 1.5 μg/m3 lower during the period of a safer-at-home order, representing a 25% reduction. We document a similar reduction in air pollution following the implementation of similar policies in Europe. We calculate that as of the end of June 2020, the benefits from avoided car collisions in the U.S. were approximately $16 billion while the benefits from reduced air pollution could be as high as $13 billion.

Keywords: COVID-19, Safer-at-home, Lockdowns, Air pollution, Car crashes

The emergence of COVID-19 (formally termed SARS-CoV-2 by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses) has fundamentally changed human behavior. Characterized as a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, the global scientific community is actively researching the virus and its impact. As of December 31, 2020, the United States has seen over 341 thousand deaths and over 19 million confirmed cases. COVID-19 has led most state governors to impose safer-at-home orders. We consider safer-at-home orders to be a blanket term that captures other efforts introduced simultaneously (or nearly so) whose goal was the suspension of economic activity and public interaction in an effort to “flatten the curve”.1 To date, the focus of the debate over safer-at-home orders has been on their efficacy of transmission suppression and the implicit trade-off between lives saved and reduced economic activity. Safer-at-home orders have resulted in serious negative impacts on Americans in several dimensions: studies have shown large impacts on the labor market, mental health, and domestic violence incidents, for instance (e.g., Adams-Prassl et al. (2020); Beland et al. (2020); Brodeur et al. (2021); Leslie and Wilson (2020)).

In this paper, we study other potential positive externalities of safer-at-home orders; a decrease in air pollution and automobile collisions.2 We rely on a difference-in-differences framework for identification. The setting is attractive for at least two reasons. First, not all states (nor all counties) implemented safer-at-home orders, and there is significant variation in implementation timing for those who do. Second, our identification strategy allows us to address issues of reverse causality and omitted variables bias by comparing states (or counties) that implemented safer-at-home orders at different points in time. Our identification assumption is that, conditional on COVID-19 incidence and other policies implemented (e.g., statewide face masks mandates), the difference in pollution (or automobile collisions) between areas with and without safer-at-home orders would be constant over time.

We first investigate the impact of safer-at-home orders on pollution. We find that state safer-at-home policies decreased air pollution (specifically PM2.5) by almost 25%, with larger effects for urban counties. This large effect size suggests that these policies reduce emissions by almost one half of a within-county standard deviation. Our estimates also suggest the issuance of a state order reduces the number of county-days with an acceptable PM2.5 level by around 10 percentage points (nearly eliminating ‘polluted’ days). Further, we find that the decrease in air pollution persists for weeks after the order is lifted.

We check whether our results hold in a different setting by studying the impact of countrywide ‘lockdown’ policies in Europe. More specifically, we build a data set of pseudo ‘counties’ for France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom, and document a (temporary) decrease in air pollution following the implementation of lockdowns.

In addition, we estimate if there are car collision externalities stemming from the safer-at-home orders. We use daily-level traffic collision data for all counties, originally sourced through two real-time maps service API's which draw from sources such as law enforcement and transportation departments. We identify a large reduction - about 20% - in traffic collisions after a state order is issued. We also examine their severity using a four-point scale index based on traffic flow/disruption. Following an order, we find a large and significant decrease in the most common types of collisions, with an increase in the minority of the most serious. Using social mobility data, we provide evidence that individuals shift their travel away from traditionally congested periods which helps explain the pattern of overall reductions but increases in collision severity.

We then explore the heterogeneous effects of safer-at-home policies on pollution and collisions across county characteristics. We find that the decline in pollution and collisions from safer-at-home orders is larger in urban counties. Our results also indicate that counties in states with a larger share of occupations that can be done remotely experience a larger reduction in pollution and collisions from these policies.

Lastly, we provide some back-of-the-envelope calculations of the estimated benefits from reduced pollution and collisions from safer-at-home orders. Using previous estimates of willingness to pay for pollution reduction from the U.S. we find the benefit from reduced pollution ranges from $154 million to $13 billion as of the end of June 2020. Using estimates of the societal cost of car collisions from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration gives approximately $16 billion in costs avoided as a result of safer-at-home orders as of June 2020.

We contribute to a growing literature informing the ongoing debate about safer-at-home orders (see Brodeur et al. (2020a, 2020b, 2020c) for a literature review). Previous studies have documented the positive impact of lockdowns on (preventing) COVID-19 incidence, but also their potential negative effects on the economy (e.g., Kong and Prinz (2020)), domestic violence (e.g., Leslie and Wilson (2020)), child maltreatment (e.g., Bullinger et al. (2020)) and mental health (e.g., Adams-Prassl et al. (2020)) among other socioeconomic dimensions. We contribute to this literature by pointing out two unintended benefits of lockdowns: decreased car crashes and reduced air pollution.

The most relevant papers to ours are possibly He et al. (2020) and Dang and Trinh, 2021. He et al. (2020) provide evidence that lockdowns in China decreased PM2.5 by approximately 25%. Dang and Trinh, 2021 provide cross-national evidence for 164 countries on the impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on global concentration of NO2 and PM2.5. They find that lockdowns decreased NO2 and PM2.5 levels by about 5 percent. Other relevant work includes Cicala et al. (2020), Graf et al., 2021 and Le Quéré et al. (2020). Cicala et al. (2020) provide evidence that electricity consumption fell in the U.S. during the pandemic.3 Graf et al. (Forthcoming) investigate how lockdowns can affect electricity market performance using Italian data. Le Quéré et al. (2020) study the effects of government policies on country-level energy demand finding CO2 emissions (estimated directly from confinement data) decreased by 17% compared to previous year levels. Our paper focuses on the immediate positive externalities from a reduction in road congestion and ambient particulate matter, using the available local and real time data necessary to understand how local and state government policies affect behavior.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 1 details the data, while Section 2 describes our identification strategy. We discuss the impacts of safer-at-home policies on pollution in Section 3. Section 4 investigates the effects of safer-at-home policies on collisions. In Section 5, we investigate the relationship between mobility and collision during safer-at-home orders. Section 6 provides our back of the envelope calculations of the positive externalities these policies. Section 7 concludes.

1. Data

In this section, we describe our data. We first provide information on COVID-19 cases and fatalities, and how they vary over time and across states. We then describe data sources for safer-at-home orders and other policies. Last, we describe our pollution and collision data.

1.1. COVID-19 known cases and deaths

The first COVID-19 case in the U.S. was a man who had returned from Wuhan, China to Washington State. The case was confirmed on January 20, 2020. Six additional states confirmed cases later in January and February. The first case of community transmission was confirmed in California, on February 26, 2020. As of April 30, 2020 there were over 1 million confirmed cases due to COVID-19 in the United States. On the last day of 2020, the CDC reported 19,663,976 total cases and 341,199 total deaths from COVID-19.

The COVID-19 known cases and deaths data comes from the Github repository associated with the Johns Hopkins University interactive dashboard. The data are available here: https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19. Appendix Figs. A1 and A2 illustrate the geographic distribution of COVID-19 known cases and deaths per 10,000 inhabitants, respectively.

1.2. Safer-at-home policy

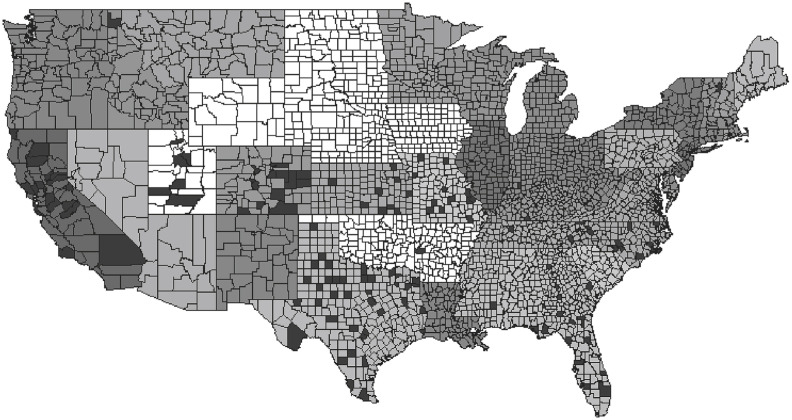

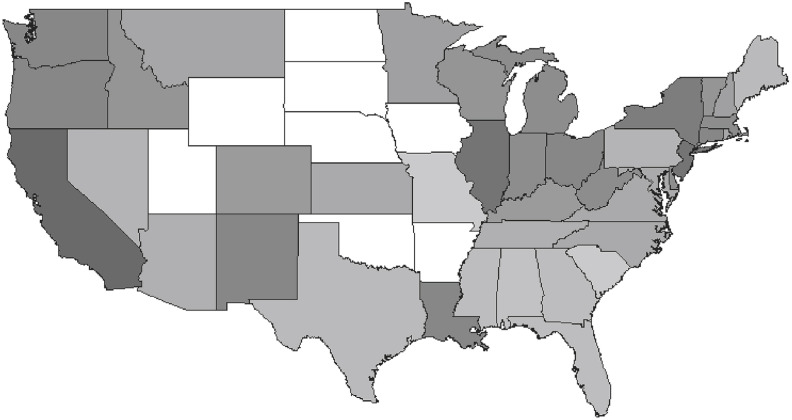

Data for safer-at-home policies are from the New York Times.4 Fig. 1, Fig. 2 present maps indicating counties and states that implemented a safer-at-home policy prior to April 30, 2020, respectively. Nearly all states had implemented such a policy at this point in time, and the timing of implementation varies considerably. The first state to implement a safer-at-home policy was California on March 19th, 2020. 18 more states followed California in the following week. In 2020, 43 states (including the District of Columbia) had implemented some form of lockdown, representing 2628 counties. Only California, North Carolina and Ohio had an active safer-at-home order on the last day of 2020. 148 counties implemented a county-level safer-at-home policy, of which 141 are located in states that would eventually have a statewide policy. The median county implemented its safer-at-home policy one week prior to the statewide policy.5

Fig. 1.

Counties that Issued an Order. Notes: This map presents counties and states that issued an order prior to April 30, 2020. Counties that issued their own order prior to their state shaded darkest. For states, the darker the fill, the earlier the state issued the order. States in white did not issue an order.

Fig. 2.

States that Issued a Lockdown. Notes: This map presents states that issued an order prior to April 30, 2020. The darker the fill, the earlier the state issued the order. States in white did not issue an order.

We also use data on the stringency of safer-at-home orders from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) implemented by the University of Oxford's Blavatnik School of Government. We rely on an ordinal scale measure of safer-at-home requirements, which takes the value of zero in the absence of an order, one if governmental authorities recommended a state to stay home, and two if staying-at-home was required with few exceptions such as daily exercise, grocery shopping, and essential trips.

1.3. Other policies

We also gather data on the following COVID-19 statewide policies: day care closures, freezes on eviction, mandatory face mask policies, and mandated quarantine for individuals arriving from another state. Data on the implementation and duration of these policies come from Raifman et al. (2020). We provide more detailed information about these policies in Appendix 7.1.

1.4. Social distancing data

We extract data on social distancing from Unacast's COVID-19 Toolkit. Unacast provides a Social Distancing Scoreboard at the county-level using cell phone data which aims to empower organizations to evaluate the effectiveness of social distancing initiatives (Brodeur et al. (2020a, 2020b, 2020c)).

Using data pre-COVID-19 outbreak as a baseline, Unacast computes rate of changes in average distance traveled, non-essential visitation, and human encounters. For our analysis, we rely on the first index. Unacast's data is available starting February 24, 2020 and unavailable for many counties.

1.5. Air pollution and weather

1.5.1. Particulate matter concentrations

Air pollution data is from in situ monitors and provided by AirNow, a partnership between United States agencies.6 The primary pollutant we use in our analysis is particulate matter with diameter less than 2.5 μm - particles small enough that they are capable of being inhaled and passing through the blood-brain barrier. Emissions from combustion of gasoline, oil, diesel fuel or wood produce much of the PM2.5 pollution found in outdoor air. PM2.5 is associated with the greatest proportion of adverse health effects related to air pollution in the United States.

The Environmental Protection Agency monitors PM2.5 levels to protect public health and the environment, and has found average decreasing trends in the last two decades. From 1990 to 2016, PM2.5 measures had fallen around 25%, a reduction roughly equal to our estimated effect of the safer-at-home orders.

To aggregate PM2.5 levels from the monitor level to the county-level, we assign each county's population weighted centroid to the three nearest air quality monitoring stations. Readings from each station are then averaged using inverse distance weights where closer monitors carry proportionally more weight in the pollution level. We also restrict our estimations to areas where the nearest station is within 50 km (as accurate PM2.5 levels are necessarily local). In our sample, the minimum distance to a pollution monitoring station is 114 m, while the mean and median are approximately 25 km away.

In Appendix Fig. A3, we present average weekly PM2.5 levels by county for the week of March 1–7, 2020. This period, prior to any safer-at-home policies serves as a visual representation of the geographic distribution of air pollution levels. In Appendix Fig. A4, we present the same PM2.5 measures during the final week of April - after all eventually treated states had implemented a safer-at-home policy. See also Appendix Fig. A5 for the distribution of PM2.5 concentrations for all county-days in our sample.

1.5.2. Other air pollution measures

While a derivative of PM2.5 levels, we also provide results using the Air Quality Index (AQI). This unit-less measure ranges from 0 to 500, with a score below 50 representing ‘not harmful’ levels of air pollution.

We also use aerosol optical depth (AOD) as an alternative and more geographically dispersed measure of air pollution. AOD estimates the amount of aerosol (tiny solid and liquid particles released by cars, industries, fires, etc.) present in the atmosphere and has been used as a proxy for surface air pollution (such as PM2.5). Technically, AOD measures the “extinction of a ray of light as it passes through the atmosphere” where extinction refers to diminishment either from absorption or scattering. A greater measure of AOD indicates a higher estimate of surface air pollution. Specifically, we use daily estimates of AOD at the 10 km × 10 km resolution derived from the MODIS platform. We use pre-processed quality-controlled estimates which account for both low-quality measurements and highly reflective surfaces such as deserts.7 Appendix Fig. A6 illustrates the distribution of AOD for all county-days in our sample.

1.5.3. Temperature and precipitation

For temperature and precipitation, we use the NOAA CPC Global Daily Temperature data set.8 This data set is typically used for verification of other temperature and precipitation products, and is available from 1979 to the present. This data set provides global coverage of temperature and precipitation at the 0.5° × 0.5° spatial resolution. At the geographic center of the contiguous United States (39.83 North and 98.58 West), this represents a 55 km × 42 km grid. This data set is typically available in real time. The underlying meteorological data comes from the Global Telecommunication System daily reports. They are from 6000 to 7000 global stations, with 10% of those in the United States. The station data is then gridded using the Shepard algorithm.

1.6. Collision data

For our analysis on car crashes, we rely on collision data at the county-level from 49 states from January 1, 2020 to June 30, 2020 created by Moosavi et al. (2019). The data set is built from continuously streaming traffic data from MapQuest and Microsoft Bing map services and includes location, date, and severity of each crash. These services stream traffic incidents captured from national and state departments of transportation, law enforcement, traffic cameras, and traffic sensors. The authors of the data set collected data at 90 second intervals from 6am to 11pm and 150 second intervals from 11pm to 6am. Our main variable of interest is the daily number of collisions per county. The severity of an accident is coded as a number ranging from 1 to 4 (with 1 being the smallest impact on traffic and 4 being a significant impact on traffic). Table 1 provides summary statistics for collisions. In our sample, there are about 1.8 collisions per day per county.

Table 1.

Summary statistics.

| Mean | Std.Dev. | Max | Min | Count | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pollution | |||||

| PM2.5 | 6.641 | 3.534 | 84.4 | 0.1 | 200094 |

| PM2.5 (UK) | 9.977 | 8.015 | 45.0 | 1.4 | 25906 |

| PM2.5 (GE) | 8.691 | 6.427 | 85.4 | .7 | 66407 |

| PM2.5 (SP) | 6.984 | 4.533 | 34.9 | 1.0 | 9648 |

| PM2.5 (FR) | 8.238 | 5.803 | 189.1 | 0.5 | 23880 |

| PM2.5 (IT) | 8.594 | 4.559 | 70.6 | 1.4 | 29487 |

| Collisions | |||||

| Collisions | 1.770 | 9.949 | 811.0 | 0.0 | 237408 |

| Severity 1 collisions | 0.081 | 1.095 | 72.0 | 0.0 | 237408 |

| Severity 2 collisions | 1.293 | 8.301 | 681.0 | 0.0 | 237408 |

| Severity 3 collisions | 0.334 | 1.844 | 116.0 | 0.0 | 237408 |

| Severity 4 collisions | 0.061 | 0.537 | 31.0 | 0.0 | 237408 |

| COVID-19 | |||||

| COVID cases per 10k | 5.946 | 22.448 | 625.5 | 0.0 | 237408 |

| COVID deaths per 10k | 0.264 | 1.262 | 32.0 | 0.0 | 237408 |

| County-days under lockdown | 0.364 | 0.481 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 237408 |

| Day care closure | 0.125 | 0.330 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 237408 |

| Eviction moratorium | 0.223 | 0.416 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 237408 |

| Mandatory face mask in public | 0.055 | 0.229 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 237408 |

| Mandatory quarantine for visitors | 0.019 | 0.138 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 237408 |

Notes: Authors' calculations. PM2.5 is 24-h daily concentration of PM2.5 in μg/m3. Collisions data gathered from Moosavi et al. (2019). The severity of an accident is coded as a number ranging from 1 to 4 with 1 being the smallest impact on traffic and 4 being a significant impact on traffic.

2. Identification strategy

Our hypothesis is that safer-at-home policies decreased PM2.5 concentrations and collisions. To investigate this hypothesis, we estimate the following difference-in-differences specification:

| (1) |

where y cst is, for instance, daily average PM2.5 measured in μg/m3 in county c in state s and date t. We include a full set of county dummies γ c to control for time-invariant county characteristics and calendar date dummies δ t (e.g., a separate dummy for March 1, 2020, March 2, 2020, etc.). The time period spans January 1st, 2020 through the moment the statewide safer-at-home ended. We thus have an unbalanced panel of counties. For the bulk of our analysis, the sample is restricted to counties that eventually implement a county order or are under a statewide order. The last day in our sample is June 30, 2020, although the sample ends prior to June 30 for the majority of counties. The state-level variable StateSafer st equals one once the state has implemented the order and zero for the pre-policy period.9 Our primary coefficient of interest is β. We also investigate the impact of county orders. The county-level variable CountySafer ct equals one once the county has issued the order and zero for the pre-policy period. Another coefficient of interest (when included) is thus λ. We cluster standard errors at the state level, corresponding to the primary policy and treatment level.

Note that the adoption of safer-at-home policies and timing of adoption may be endogenously related to the severity of the virus. We thus include, X cst, a vector of county-day level covariates including known COVID-19 cases and deaths per 10,000 inhabitants. County population data comes from 2019 Census estimates. We also control for county-day precipitation and average temperature. Further, we include controls for the following statewide policies: day care closures, eviction moratoriums, mandatory face mask policies, and mandated quarantine for individuals arriving from another state. The inclusion of these additional policy variables help us to identify the impact of safer-at-home policies rather than the joint impact of multiple government interventions.

Our identification assumption is that, conditional on the included control variables, the evolution of PM2.5 concentrations or collisions for counties with safer-at-home policies would not have been different from those without the policies. This amounts to an assumption of parallel trends in PM2.5 or collisions for treated and untreated counties.10

Recent research on two-way fixed-effects (TWFE) estimators, which are usually motivated as difference-in-differences with multiple time periods, has identified issues that arise in the presence of heterogeneous treatment effects across groups or time (Callaway and Sant’Anna (Forthcoming); De Chaisemartin and d’Haultfoeuille (2020); Goodman-Bacon and Marcus (2020)). Using the twowayfeweights Stata package detailed in De Chaisemartin and d’Haultfoeuille (2020), we document that 44% of the naive average treatments on the treated for pollution are assigned negative weights, indicating the need to reexamine our results using an alternative estimator. We use the alternative estimators provided by Callaway and Sant’Anna (Forthcoming); Callaway and Sant’Anna (2020) that are most appropriate for the staggered adoption of safer-at-home policies in our sample. We discuss these alternative estimates in section 3.11

3. Safer-at-home orders and pollution

In this section, we present the main results for air pollution using our difference-in-differences strategy. We then provide additional results for Europe and heterogeneity analyses.

3.1. Main results

In Table 2 , we present our main result: a state's implementation of a safer-at-home order significantly lowers air pollution in its constituent counties.

Table 2.

State orders and pollution (PM2.5).

| (1)PM2.5 | (2)PM2.5 | (3)PM2.5 | (4)PM2.5 | (5)PM2.5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| During safer-at-home-order | −1.671 (0.454) |

−1.673 (0.454) |

−1.673 (0.455) |

−1.607 (0.496) |

−1.372 (0.413) |

| COVID cases per 10k | −0.003 (0.004) |

−0.003 (0.004) |

−0.003 (0.004) |

−0.002 (0.004) |

|

| COVID deaths per 10k | 0.003 (0.033) |

−0.004 (0.034) |

−0.006 (0.035) |

||

| Constant | 6.704 (0.809) |

6.704 (0.808) |

6.704 (0.808) |

6.709 (0.816) |

6.460 (0.801) |

| County FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Date FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| COVID-19 policies | Y | Y | |||

| Weather controls |

Y |

||||

| Observations | 200094 | 200094 | 200094 | 200094 | 200094 |

| Counties | 1592 | 1592 | 1592 | 1592 | 1592 |

Notes: State orders significantly reduce PM2.5. The dependent variable is average daily PM2.5 concentration at the county-level. The time period spans January 1st, 2020 through the moment the statewide safer-at-home ended. COVID-19 known cases and deaths per 10,000 people. Robust standard errors clustered at the state-level reported in parentheses. All columns include county and date fixed effects. Sample restricted to counties within 50 km of an air pollution monitoring station.

This table presents estimates of Equation (1) in which we compare counties in states with and without a statewide safer-at-home policy.12 In all columns the dependent variable is PM2.5 concentration. We use a total of 1592 counties in our estimation.

In the first column, we include only date and county fixed effects. The estimated reduction in PM2.5 from a statewide safer-at-home order is statistically significant at the 1% level and suggests that the introduction of a state order reduces PM2.5 levels by 1.7 μg/m3. With a mean of the dependent variable of 6.3 μg/m3 for the same time period one year prior, this suggests the policy decreased air pollution by more than 25%. For additional context, the within-county standard deviation of PM2.5 during the same period one year prior was 2.8 μg/m3, suggesting the policy reduces emissions by more than one half of a standard deviation.

In the second column, we include the county's number of confirmed COVID-19 cases per 10,000 inhabitants as a control. In the third column, we include the county's number of confirmed COVID-19 deaths per 10,000 inhabitants as a control. The inclusion of these two controls has almost no effect on the magnitude or significance of our estimates. The estimate for COVID-19 cases is negative and significant (statistically insignificant once we control for COVID deaths), suggesting that increased cases reduces PM2.5 in a county. In contrast, the estimate for COVID-19 deaths is not statistically significant.

In the fourth column, we control for four distinct statewide policies, while we add local weather conditions - temperature and precipitation - in the fifth column. Overall, the inclusion of other policies has little effect on the magnitude and significance of our state order estimates on PM2.5. The inclusion of weather controls makes the reductive effect of safer-at-home orders on air pollution smaller in magnitude, but the estimate remains large and significant. We note that temperature (precipitation) is positively (negatively) related to PM2.5 levels.

In Appendix Table A2, we test whether counties that implemented an order prior to a statewide order are differently affected than counties that did not implement an order. In columns 1 and 2, we reproduce our main result for all counties. Columns 3 and 4 restrict the sample to the subset of counties that issued their own orders prior to their respective state. In columns 5 and 6, we restrict the sample to counties that did not implement an order prior to the statewide order. Overall, we find that the decrease in air pollution following the implementation of a statewide order is large and significant for both sets of counties. The estimate of the effect of a county order is negative, but barely statistically insignificant, suggesting that conditional on a state order being present, there is minimal additional reduction in PM2.5 from an additional county order being in effect.

In Appendix Table A3, we re-estimate the unweighted estimates from Table 2 and now weight by county population. In this manner, we place more emphasis on relatively more populous (and concurrently polluted) counties. The inclusion of this weighting increases the effect estimate by about 50% - the estimated reduction grows from 1.7 to 2.5 μg/m3 - suggesting that the reduction in PM2.5 was larger for more populous counties.

3.2. Robustness checks

In Table 3 , we conduct a similar but distinct analysis. The column specifications and structure remains the same as in Table 2. While in Table 2 the dependent variable was PM2.5 concentration, in Table 3 the dependent variable is an indicator that takes a value of one if the PM2.5 level in that county, and on that day, is above the National Ambient Air Quality Standard of 12 μg/m3.13 This reflects a change in interpretation from linear decreases in pollution concentration to decreases in exposure to environmental hazards. The interpretations of the coefficients change as well. For example, in column 1 nearly 90% of days prior to a state order have an acceptable level of ambient air pollution. Said differently, around one in ten county-days exceed the tolerable level set by the EPA. When state orders are introduced, almost all days for all counties have acceptably clean air (conditional on our control variables). The incremental addition of controls does not significantly perturb this estimate.14

Table 3.

State orders and polluted days.

| (1)PM2.5>12 | (2)PM2.5>12 | (3)PM2.5>12 | (4)PM2.5>12 | (5)PM2.5>12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| During safer-at-home-order | −0.103 (0.032) |

−0.103 (0.032) |

−0.104 (0.032) |

−0.099 (0.035) |

−0.089 (0.031) |

| COVID cases per 10k | −0.000 (0.000) |

−0.000 (0.000) |

0.000 (0.000) |

0.000 (0.000) |

|

| COVID deaths per 10k | −0.001 (0.002) |

−0.001 (0.002) |

−0.002 (0.002) |

||

| Constant | 0.109 (0.039) |

0.109 (0.039) |

0.109 (0.039) |

0.109 (0.039) |

0.093 (0.038) |

| County FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Date FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| COVID-19 policies | Y | Y | |||

| Weather controls |

Y |

||||

| Observations | 200094 | 200094 | 200094 | 200094 | 200094 |

| Counties | 1592 | 1592 | 1592 | 1592 | 1592 |

Notes: State orders significantly reduce polluted days. The dependent variable takes a value of 1 if PM2.5 is above the Annual National Ambient Air Quality Standard of 12 μg/m3. The time period spans January 1st, 2020 through the moment the statewide safer-at-home ended. COVID-19 known cases and deaths per 10,000 people. Robust standard errors clustered at the state-level reported in parentheses. All columns include county and date fixed effects.

We rely on a remotely-sensed measure of air pollution in Appendix Tables A6 and A7; aerosol optical depth (AOD). AOD is a measure of the diffusion of light through the atmospheric column and a popular measure of air pollution which has the distinct advantage of being measured from space. Our main results (for example those presented in Table 3) are restricted to areas within 50 km of an air pollution monitoring site, reflecting the concern that air pollution concentrations are inherently local. The locations of air quality monitoring sites are also most likely non-random and, more recently, concerns of strategic placement have also arisen. A uniformly measured and spatially available measure of air pollution found in aerosol optical depth does not suffer the same weaknesses, but does come with its own. For example, the relationship between AOD and PM2.5 (and other pollutants) is often area-specific and can vary with surface albedo, making the aggregation necessary in our setting, difficult. Lower AOD values are typically associated with lower levels of air pollution.

Appendix Table A6 uses aerosol optical depth as the dependent variable, but to maintain comparability with our main estimates in Table 2, we restrict the sample to counties within 50 km of a monitoring station. In Appendix Table A7, we relax this restriction. The estimates presented in Appendix Tables A6 and A7 suggest that, during a lockdown, the measured within-county AOD is much lower (although imprecisely estimated), corresponding to reductions in air pollution.15 The main benefit of AOD over local PM2.5 concentrations is greater spatial availability. But one drawback is the use of particularly coarse readings from the MODIS-TERRA platform and the often relatively clean air in the United States (causing measures of AOD to be often missing). Of course with AOD, there is also the possibility that air pollution above the surface level is also being measured.

Appendix Table A8 provides the three aggregated alternative TWFE estimators described in Callaway and Sant’Anna (Forthcoming). Column 1 recreates the estimate from column 1 of Table 2. Column 2 provides the weighted (by group size) average of all estimated county-day average treatment effects. In column 3, we provide the average treatment effect over all lengths of exposure to safer-at-home orders, while column 4 provides the average effect of implementing a safer-at-home order for counties that were under an order in any period. All columns include county and date fixed effects. These alternative estimators confirm that safer-at-home orders have a negative and statistically significant effect on PM2.5.

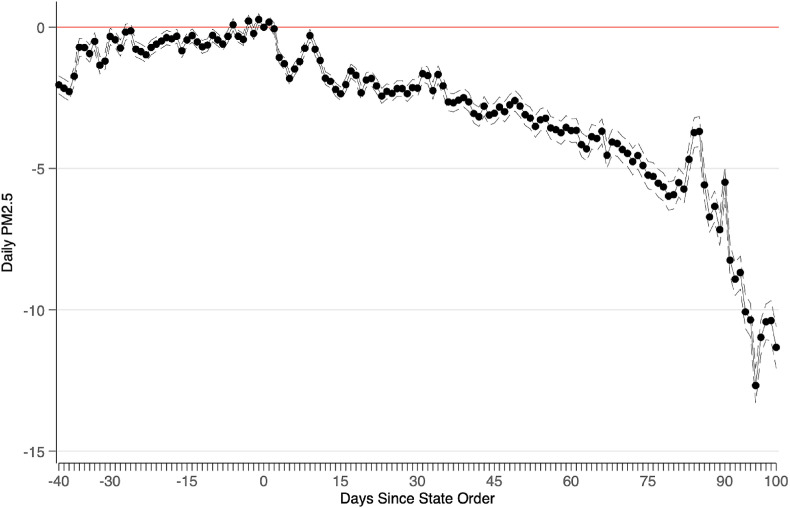

3.3. Graphical evidence

We provide a visual representation of the reduction in pollution from the implementation of a safer-at-home order in Fig. 3 .16 This figure plots estimated PM2.5 levels at daily intervals pre- and post-statewide order. The associated equation is:

| (2) |

Fig. 3.

PM2.5 Concentrations Over Time. Notes: This figure presents regression coefficients for PM2.5 concentrations corresponding to number of days before/after state order issued. Temperature, precipitation, COVID-19 cases and deaths, and other policy controls are included along with date and county fixed effects. Confidence intervals at 95% presented.

This specification decomposes the level of PM2.5 by the number of days before and since the state order. The regression includes county and date fixed effects in addition to our full set of weather and policy controls. We plot the estimated difference between PM2.5 levels compared to the date that the state order was implemented (which is set to zero). The time window is 40 days before to 100 days after the policy is implemented. The dashed lines represent robust 95% confidence intervals.

Fig. 3 shows that PM2.5 levels, within-county and conditional on our covariates, were relatively stable from 40 days before up to the implementation of the statewide order. We begin to see a slight reduction in PM2.5 emissions once the order is implemented, with a much steeper decrease in the weeks following implementation. The negative impact is at its largest at the end of the time window, suggesting that a safer-at-home order's impact on air pollution persists in the weeks following the moment orders are lifted (i.e., all lifted after day (t+80)).

3.4. Strictness of order and heterogeneity analyzes

In Appendix Table A9, we test whether the estimated air pollution reduction during a safer-at-home order is related to the strictness of the order. Our variables of interest are dummies for “low” safer-at-home order intensity and “high” safer-at-home order intensity. Our estimates show that higher intensity orders are associated with a larger decrease in air pollution. This result has important policy implications since the strictness of orders may be related to many factors such as economic losses and mental health distress.

We investigate whether the magnitude of the documented effect of safer-at-home policies on pollution is related to county-level characteristics in Appendix Table A10. More precisely, we test whether more urban, younger, and Democrat counties experienced a larger decrease in PM2.5 following the implementation of a safer-at-home order.17 In columns 1 and 2, we split the sample for over and below county urbanization of 50%, respectively. We find that the estimated decrease is about 25% larger for urban counties than for rural counties, confirming our previous finding that more populous counties are more affected by state orders.

In columns 3 and 4, we restrict the sample for counties in which a majority of voters voted for President Trump during the 2016 Presidential Election. Column 4 restricts the sample to the other counties. We find that the decrease in pollution is much smaller in counties that supported President Trump in 2016. This finding is in line with Engle et al. (2020), who document that counties with a lower share of votes for Republicans comply more with safer-at-home orders. We confirm this pattern in Appendix Table A11. Of note, we find that ‘Trump’ counties are also different in many other aspects that may be correlated with the ability to reduce emissions. Readers should therefore be careful when interpreting the findings of this heterogeneity analysis.

Column 5 (6) restricts the sample to counties with relatively more (less) individuals aged at least 65 years old (split by median). We find that counties with relatively more young people experienced a larger decrease in PM2.5, perhaps due to more work being done remotely during-lockdown.

We explore this possibility in columns 7 and 8. We split the sample into counties within states which have above and below median shares of occupations that can be done from home. These classifications of the feasibility of working from home in a given occupation come from Dingel and Neiman (2020) and associated coding provided by those authors and Ole Agersnap. Column 7 (8) corresponds to counties in states with an above (below) median share of occupations able to be done from home. We find that counties in states with a greater ability to work from home experience a slightly larger decrease in PM2.5.

3.5. Europe

We now explore the impact of countrywide lockdowns on pollution in Western Europe. This exercise serves at least two purposes. First, examining the European case is worthy of study in itself. Second, it serves as a test of external validity for our U.S. results. At the time of writing, some form of lockdown had been applied to the residents of most European countries - we focus on France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom, the largest countries in Europe by population.

For this analysis, we examine how national-level orders affected PM2.5 concentrations at the sub-national level. We divided each country into administrative units at a similar administrative level to United States counties for comparability. A total of 841 areas are used with 96 from France (roughly corresponding to départments), 403 from Germany (roughly corresponding to kreise), 113 from Italy (roughly corresponding to provinces), 55 from Spain (roughly corresponding to provinces) and 192 from the United Kingdom (roughly corresponding to counties).

Air pollution data was provided by the European Environmental Agency. Pollution remains measured in μg/m3 at the population-weighted centroid for each administrative unit (determined in Hall et al. (2019)). The mean PM2.5 concentration during the period is 8.7 μg/m3, and the within-unit standard deviation is 6.0. Temperature and precipitation use the same dataset as our U.S. estimates.

Data on lockdowns come from the Coronavirus Government Response Tracker produced by the University of Oxford. This dataset tracks worldwide national (and in rare cases) subnational government responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. We chose this data set because of its uniform coding over the different countries we examine, and a centralized and curated count of confirmed cases and deaths. Further, the uniformity of the mask mandate, quarantine mandate and school closures coding between countries is also valuable. The main drawback to this data set is that the government response, cases, deaths, and policy variables are at the national-level.

Our main results for Europe are presented in Table 4 . The dependent variable in all columns is PM2.5 measured in μg/m3. We control for the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths at the national-level. The estimate for our countrywide lockdown is statistically significant at the 1% level and suggests that the introduction of a lockdown reduces PM2.5 levels by about 1.7 μg/m3 in our preferred specification. The mean of the dependent variable for pre-lockdown days is about 10.7 μg/m3, suggesting that European lockdowns decreased air pollution by about 16%.

Table 4.

European national orders and pollution (PM2.5).

| (1)PM2.5 | (2)PM2.5 | (3)PM2.5 | (4)PM2.5 | (5)PM2.5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| During lockdown | −1.047 (0.036) |

−1.069 (0.033) |

−0.969 (0.036) |

−1.676 (0.037) |

−1.690 (0.037) |

| COVID cases per 10k | −0.005 (0.001) |

−0.003 (0.001) |

0.003 (0.001) |

0.006 (0.001) |

|

| COVID deaths per 10k | −0.117 (0.015) |

−0.015 (0.016) |

0.034 (0.016) |

||

| Constant | 35.373 (0.135) |

24.137 (0.121) |

24.151 (0.121) |

24.254 (0.119) |

24.055 (0.119) |

| Date FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Mask mandate | Y | Y | |||

| Quarantine mandate | Y | Y | |||

| School closures | Y | Y | |||

| Temperature | Y | ||||

| Precipitation |

Y |

||||

| Observations | 155328 | 138568 | 138568 | 138568 | 136300 |

Notes: National orders significantly reduce PM2.5 in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom. The dependent variable is average daily PM2.5 concentration, measured at the population centroid for an administrative area from the three nearest air quality monitors. The mean concentration during the period is 8.7, and the within-unit standard deviation is 6.0. An observation is an area-day. A total of 841 areas are used with 96 from France (departments), 403 from Germany (kreise), 113 from Italy (provinces), 55 from Spain (provinces) and 192 from the United Kingdom (counties). Observations are from the first to the 300th day of 2020, which includes both before, during, and after lockdowns. Standard errors reported in parentheses. All columns include area and date fixed effects.

We also document the effect of lockdowns for each country separately in Appendix Table A12. Our country-level controls are necessarily dropped for this analysis since we estimate the effect of a national lockdown for each of the countries separately. We find large and significant reductions in air pollution for all five countries.18

Last, in Appendix Fig. A8, we present our leads and lags estimates for Europe, using the specification which decomposes the level of PM2.5 by the number of days before and since the national order. Following a lockdown, we see a general reduction in air pollution levels. This (admittedly messy) trend continues downward for approximately 15 days before reversing slowly and returning to pre-order levels around 75 days after the initial lockdown is released. This return to normal levels and its ‘spiky’ estimation likely reflects both underlying heterogeneity in strictness of orders and different country implementation and lifting of orders.

4. Safer-at-home orders and collisions

We now present the main results for collisions. Safer-at-home orders are implemented primarily to save lives by limiting the spread of the virus through social distancing, non-critical business closures, and restriction to only necessary activities. As a by-product, these orders can also result in fewer vehicles on the road directly reducing air pollution, collisions, and perhaps even fatalities. As motor vehicle collisions are one of the leading causes of deaths for Americans, these unintended benefits would suggest that the number of lives saved by safer-at-home orders may be more than expected.19

4.1. Main results

In Table 5 , we estimate the effects of state orders on the collision incidence rate in a county, per day.20 We present the incidence-rate ratios of a Poisson count model with county and date fixed effects; an estimate below one is a reduction in the dependent variable. The time period is January 1st, 2020 through the moment the statewide safer-at-home order ends.21 The structure of the table is the same as Table 2.

Table 5.

State orders and collisions.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| During safer-at-home-order | 0.840 (0.050) |

0.839 (0.050) |

0.838 (0.050) |

0.826 (0.045) |

0.793 (0.045) |

| COVID cases per 10k | 1.002 (0.000) |

1.003 (0.001) |

1.002 (0.001) |

1.002 (0.001) |

|

| COVID deaths per 10k | 0.986 (0.012) |

0.981 (0.011) |

0.983 (0.011) |

||

| County FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Date FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| COVID-19 policies | Y | Y | |||

| Weather controls |

Y |

||||

| Observations | 237569 | 237569 | 237569 | 237569 | 237408 |

| Counties | 1711 | 1711 | 1711 | 1711 | 1710 |

Notes: State orders significantly reduce traffic collisions. Poisson model with fixed effects. The dependent variable is count of traffic collisions at the county-level. Coefficients are incidence rate-ratios, wherein a value below one indicates a decrease in the dependent variable and a value above indicates an increase. The time period is January 1, 2020 through the moment the statewide safer-at-home ended. COVID-19 known cases and deaths per 10,000 people. Robust standard errors reported in parentheses. All columns include county and date fixed effects.

In the first column, we estimate that a state order reduces the incidence of collisions by 16%.22 In columns 2 and 3, we introduce the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths, respectively. Regardless of the underlying severity of the infection, the effectiveness of the state order remains large and statistically significant. In the fourth column, we introduce the set of other policies, while column 5 adds weather controls.23 Introducing these additional variables in the model decreases the size of the coefficient (i.e., increases the estimated decrease in car collisions) and has no effect on the significance of the estimates. In column 5, the estimate suggests that safer-at-home orders decrease daily collisions by 20%. As there are approximately 1.4 collisions for treated counties per county and per day during the safer-at-home order, this reduction implies a counterfactual of about 1.7 collisions - a reduction of 0.35 collisions.

In Appendix Table A14, we repeat the analysis presented in Appendix Table A2 and test whether counties that implemented an order prior to a statewide order are differently affected than counties that did not implement their own order. The estimate suggests that safer-at-home orders decrease car collisions for both sets of counties with a slightly larger decrease for counties that implemented an order prior to the statewide order. In addition, we find that conditional on the presence of a statewide order, county orders also statistically significantly decrease collisions. The estimated negative effect of a county order is equal to that of the statewide order, suggesting that counties also have the ability to significantly reduce collisions by issuing safer-at-home orders, even when under the influence of a statewide order.

To sum up, we find that state and county orders significantly decrease collisions. This result is quite important given the large number of car crash fatalities in the U.S. (about 35,000 in 2016).

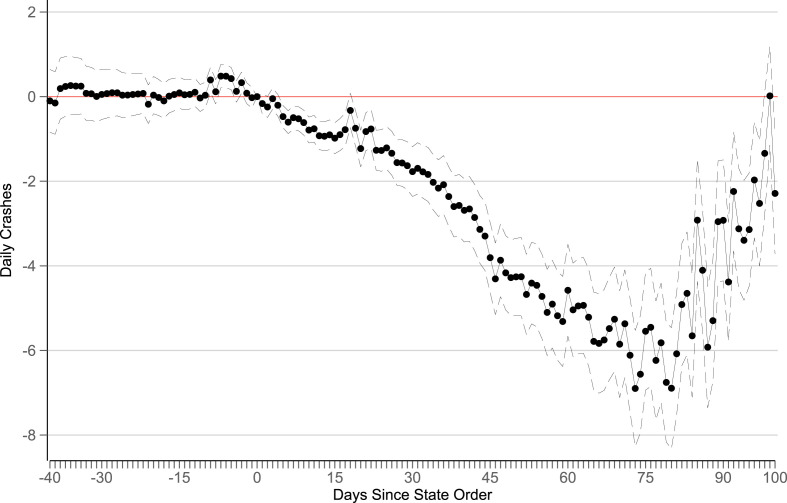

4.2. Graphical evidence

We provide a visual summary of the collision impact in Fig. 4 . This figure is similar to Fig. 3 and plots the estimated collision levels at daily intervals pre- and post-statewide order (as in equation (2)). Our estimates are not statistically significant from 40 to a few days prior to the implementation of the order. There is a small increase in collisions a few days prior to the implementation of the order, perhaps due to growth in traffic for last minute shopping. We then document a large decrease in collisions during safer-at-home orders, with the largest estimated coefficients from 45 to 80 days post-order. In other words, collisions are significantly reduced for as long as safer-at-home orders are in place. Once orders start to be lifted (i.e., all lifted after day (t+80)), the effect of the order on collision decreases in magnitude and becomes insignificant around 95 days after the order. These results suggest that orders do not have persistent effect on collisions.

Fig. 4.

Traffic Collisions Over Time. Notes: This figure presents regression coefficients for collisions corresponding to number of days before/after state order issued. Temperature, precipitation, COVID-19 cases and deaths, and other policy controls are included along with date and county fixed effects. Confidence intervals at 95% presented.

4.3. Severity of collisions

We now turn to the impact of safer-at-home orders on the severity of collisions. The severity of each collision is coded based on traffic flow/disruption and graded from one to four by the data providers. A value of one indicates a short delay as a result of the accident while a four indicates a significant impact on traffic, i.e., a long delay. Before the order period, the least common category of collision was the least severe. During the order period, the least common category was the most severe. During both periods, the most common severity of a collision is category two.

The estimates are presented in Table 6 . All columns include our full set of controls. Column 1 reproduces our main results for any of the collision severities, while columns 2–5 look at the impact of statewide orders on each of the four severity categories, respectively. The number of counties varies across columns since counties with no collisions in a given severity category are omitted.24 Our estimates suggest that statewide safer-at-home orders significantly decreased collisions of severity one and two, by 14% and 23% respectively. There is no effect for the second-to-most severe crashes. Interestingly, we document increases in the most severe type of collisions, with an increase of 18% (a large percentage increase, however, this increase is relative to a small baseline). This result is in line with the idea that some drivers might be speeding more during lockdowns, which could lead to an increase in severe (and often fatal) collisions.

Table 6.

State orders and collision severity.

| (1)Any | (2)Severity 1 | (3)Severity 2 | (4)Severity 3 | (5)Severity 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| During safer-at-home-order | 0.793 (0.045) |

0.855 (0.031) |

0.769 (0.034) |

1.006 (0.087) |

1.179 (0.146) |

| COVID cases per 10k | .998 (0.001) |

0.998 (.001) |

1.001 (0.001) |

1.004 (0.001) |

1.004 (0.001) |

| COVID deaths per 10k | 1.033 (0.011) |

1.033 (.0179) |

0.969 (0.017) |

0.970 (0.012) |

1.013 (0.016) |

| County FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Date FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| COVID-19 policies | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Weather controls |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| Observations | 237408 | 60138 | 207757 | 166441 | 145069 |

| Counties | 1710 | 418 | 1490 | 1189 | 1031 |

Notes: Poisson model with fixed effects. The dependent variable is count of traffic collisions at the county-level. Coefficients are incidence rate-ratios, wherein a value below one indicates a decrease in the dependent variable and a value above indicates an increase. The time period is January 1, 2020 through the moment the statewide safer-at-home ended. COVID-19 known cases and deaths per 10,000 people. Robust standard errors reported in parentheses for all columns except column 2, which is non-singular when robust standard errors are applied. All columns include county and date fixed effects.

4.4. Strictness of order and heterogeneity analyzes

We now check whether more stringent safer-at-home orders lead to a greater decrease in collisions than orders simply recommending to stay home. The estimates are presented in Appendix Table A9, columns 3 and 4. Again, our variables of interest are dummies for “low” safer-at-home intensity and “high” safer-at-home intensity. Our estimates show that both types of orders lead to a decrease in collisions of about the same magnitude.

Appendix Table A15 provides the heterogeneity analysis by county characteristics. The structure of this table is similar to Appendix Table A10. We find that the decrease in collisions is driven entirely by urban counties, with a significant decrease of about 23% in daily collisions. By political divide, we also find that counties that supported President Trump in 2016 have a smaller reduction in collisions than those who did not. By resident age, the difference seems to be small. We find that the decrease in collisions is very large and significant for counties in states with above median shares of occupations that can be done remotely, while the estimate is slightly greater than one (corresponding to an increase in collisions) for counties below the median share.

To sum up, our results suggest that the documented decrease in collisions does not persist over time, is driven by urban counties, counties with lower support for President Trump, and counties in which workers are more able to work remotely.

5. Safer-at-home orders, social distancing and collisions

We now investigate one of the mechanisms through which safer-at-home policies might have impacted car collisions; changes in social distancing behaviors. For this analysis, we rely on social distancing cell phone data from Unacast.

We proceed in three steps. First, we note that a large number of studies have documented the impacts of safer-at-home on social mobility, including our own working paper Brodeur et al. (2020a, 2020b, 2020c). See, for instance, Brodeur et al. (2020a, 2020b, 2020c) and Cicala et al. (2020) who rely on Unacast data and provide evidence that safer-at-home policies decreased total distance traveled.25

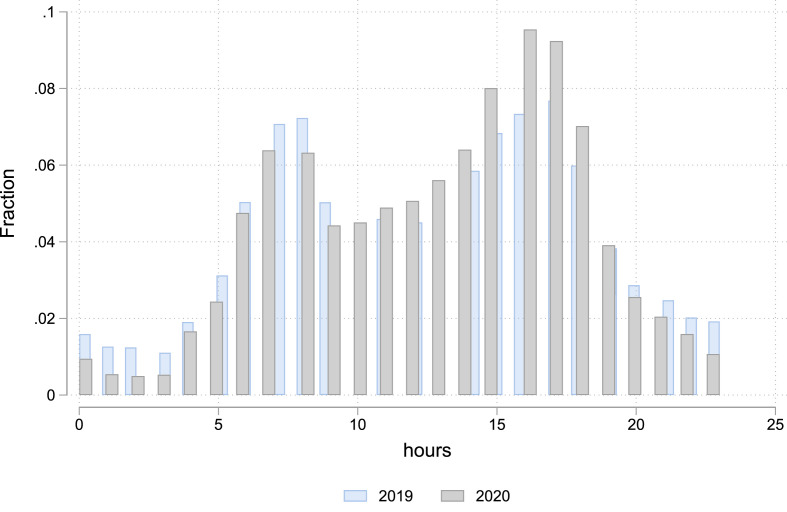

Second, we test whether safer-at-home orders changed the daily distribution of car collisions. In other words, we want to explore whether or not the change in collisions caused by safer-at-home orders is partly coming from a change in the timing of travel (and therefore a change in the relative congestion levels of different times of day) rather than entirely due to reductions in travel. In addition, this may have implications for the composition of collisions in terms of single or multiple vehicles involved. Fig. 5 illustrates the distribution of collisions across all hours of the day for our sample period and the corresponding time period in 2019. We find that the timing of collisions changed in 2020 in comparison to 2019, with more collisions in 2020 occurring during the afternoon and less during the night and early rush hour. A large literature documents a positive or concave relationship between traffic/congestion and car crashes (e.g., Gwynn (1967); Head (1959); Schoppert (1957); Zhou and Sisiopiku (1997)). See Retallack and Ostendorf (2019) for a literature review. It is posited that this relationship could be a result of aggregating single vehicle and multi-vehicle collisions where single vehicle collisions are high during periods of little congestion and multi-vehicle collisions are high during periods of high congestion. As safer-at-home orders increase work from home and decrease mobility, we should expect to see less congestion and as a consequence fewer collisions during the typical rush hour periods. Similarly, as individuals now have more flexibility in their schedules, we might expect trips to be displaced across hours of the day rather than eliminated entirely and as a consequence we could expect an increase in fatal collisions. While we do not observe collision fatality directly, we do provide evidence of increased collision severity as measured by traffic delays in Table 6. Overall, these findings provide suggestive evidence that the increase in more severe collisions during safer-at-home orders is partly due to a shift in the distribution of traffic (and therefore congestion) across hours of the day.

Fig. 5.

Traffic Collisions Across Hours of Day. Notes: This figure presents histograms for collisions across all hours of the day for our sample period and the corresponding time period in 2019.

Third, we document the relationship between travel distance and collisions by exploiting large variation in mobility due to safer-at-home orders. As the typical structure of work days and commutes was significantly altered by safer-at-home orders, it is possible that the positive or concave relationship between congestion/traffic and collisions no longer holds while they are in effect. While social mobility data does not provide direct evidence of congestion, we can use this data to explore the suggestive evidence of the relationship between travel and collisions using the exogenous variation in traffic from safer-at-home orders. However, we are unable to say anything about the concave nature of the relationship using our empirical strategy.

To attempt to achieve exogenous variation of mobility at the county-level, we instrument travel distance with statewide safer-at-home orders. The rationale for the instrument is that statewide orders led to a large decrease in mobility, which we exploit to document the relationship between mobility and collisions.

More precisely, we estimate:

| (3) |

where StateSafer st equals one once the state has implemented the order and zero for the pre-policy period. We run a first stage in which we regress this variable on the travel distance at the county-level, including all controls and fixed effects as in Equation (1). Then we plug in the predicted values of the first stage and estimate the second stage of the 2SLS. The dependent variable in the second stage is the number of traffic collisions. The time period is March 1, 2020 through the moment the statewide safer-at-home ended.

For our instrument to be valid two conditions have to hold. First, our instrument has to be a strong predictor of travel distance. As mentioned before, a large literature shows that statewide safer-at-home orders significantly decreased mobility. The F-statistic for the first stage is about 1733 confirming the strong negative impact of orders on mobility.

Second, in order for our instrument to allow a causal interpretation, statewide orders must only affect the number of collisions through its effect on social mobility, i.e., the exogeneity assumption. We believe this condition is unlikely to hold in our setting given the documented effect of lockdowns on economic activity and other socioeconomic variables. This is an issue since it is plausible that labor force status and work arrangements are related to driving behavior. Nonetheless, we proceed with our 2SLS exercise, but caution readers that the exclusion restriction is likely violated.

Table 7 presents our estimates of Equation (3). Column 1 is for all counties, column 2 corresponds to majority urban counties, and column 3 to majority rural counties. The estimate in column 1 suggests that a 100% increase in travel distance relative to the baseline period is associated with 4 additional car collisions per county-day. The estimate is statistically significant at conventional levels. The estimate in column 2 is also statistically significant and suggests a 100% increase in travel distance relative to the baseline period is associated with just over 9 additional collisions per county-day in urban counties. Meanwhile, we find no evidence that changes in travel distance induced by safer-at-home orders reduce collisions in rural counties. Taken together, these findings provide suggestive evidence that the reduction in collisions stemming from safer-at-home orders is being modulated through mobility and is driven by urban counties rather than rural counties. Consistent with the existing literature, the positive relationship between congestion (proxied by travel distance) and collisions remains during COVID-19.

Table 7.

Travel distance and collisions – instrumental variable.

| (1)All | (2)Urban | (3)Rural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Travel Distance | 4.061 (0.999) |

9.187 (2.576) |

0.071 (0.133) |

| County FE | Y | Y | Y |

| Date FE | Y | Y | Y |

| Case & Death rates | Y | Y | Y |

| COVID-19 policies | Y | Y | Y |

| Weather controls |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| Kleibergen-Papp F-stat | 1733 | 807 | 755 |

| Observations | 159488 | 159488 | 228352 |

Notes: 2SLS with fixed effects. The dependent variable (second stage) is the number of traffic collisions at the county-level. The instrumental variable is the presence of a statewide safer-at-home policy. The time period is March 1, 2020 through the moment the statewide safer-at-home ended. COVID-19 known cases and deaths per 10,000 people. Robust standard errors reported in parentheses. All columns include county and date fixed effects.

To summarize, we argue that safer-at-home orders led to a decrease in social mobility and a shift in the timing of traffic away from traditionally congested periods, and show suggestive evidence that these are two of the main driving forces behind the observed reduction in collisions and increase is collision severity.

6. Interpretation

In this section, we provide back-of-the-envelope calculations of the positive pollution and collision externalities generated by safer-at-home orders. Our calculations here are, in part, based on the growing literature estimating revealed - rather than stated - willingness to pay (WTP) for air quality. It is also important to note that most studies do not provide estimates of the WTP for temporary reductions in air quality, but instead attempt to identify the WTP of a permanent reduction in pollution. This means that our calculations are based on the assumption that individuals value a temporary abatement at the average annual value of a permanent reduction pro-rated for the duration of the abatement period (in this case the duration of the safer-at-home order). Note that these calculations ignore possible WTP increases for clean air during COVID-19, as recent research has begun to identify increased mortality from and transmission of the virus with higher levels of contemporaneous air pollution (Zhang et al., 2020; Pansini and Fornacca, 2020).

We first review the literature. Currie et al. (2015) exploit the effect of toxic plant openings to estimate the impact of air quality on American house values and birth weights. They find an 11% reduction in house values and a 3% increase in low birth weights in nearby households. Recent work by Ito and Zhang (2020) using purchases of air purifiers in China suggests that the mean WTP for 1 μg/m3 reduction of PM10 is 1.34 USD annually - and increases strongly with household income. For a household making 10,000 USD per year (the upper limit of the sample), they estimate a marginal willingness to pay of 5 USD per 1 μg/m3 PM10. Chay and Greenstone (2005) study housing price evolutions in the 1970's and ’80s in American counties that were quasi-randomly assigned federally mandated air pollution regulations. They find that a one unit decrease in particulates (all suspended particulates - what was targeted by the regulations) results in a 0.7 to 1.5 percent increase in house values. Deschênes et al. (2017) quantify the defensive investment portion of willingness to pay for air pollution reduction to be around one third - and that nitrogen oxide reduction program benefits ‘easily’ exceed costs. Barwick et al. (2017) estimate that the lower bound of the annual WTP for a 10 μg/m3 reduction in PM2.5 is 9.25 USD per Chinese household, or 7% of total healthcare spending. Finally, Bayer et al. (2016) estimate the WTP to avoid ozone using house purchases in the San Francisco Bay Area, finding a 10% reduction in pollution commanded a price almost equal to a 10% reduction in violent crime.

We now turn to our back-of-the-envelope calculations. To calculate these, we first rely on estimates from the U.S. to compute the WTP associated with our estimated 7%–25% reduction in PM2.5. We then scale the estimates to the duration of each state's safer-at-home order and aggregate over the number of households in the state (drawn from the 2018 American Community Survey) before finally aggregating WTP over all states implementing policies.

Recall that our estimates from Table 2 indicate that the introduction of safer-at-home orders decreased pollution by about 1.4 μg/m3 while Appendix Table A8 provides an estimate of 0.4 μg/m3. We also note that Bayer et al. (2016) find that American home owners are willing to pay between about 300 USD annually for a 10% reduction in one pollutant; the WTP associated with our estimated 7%–25% reduction in PM2.5 could thus be as high as 210–750 USD annually per household.26 Using WTP estimates from the most appropriate American samples, we find estimated benefits of 154 million to 500 million USD using the adapted WTPs from Bayer et al. (2009) (who estimate that the marginal WTP for an annual 1 μg/m3 reduction in PM10 for United States metropolitan areas to be 22 USD per household), and 3.6 billion to 13.1 billion USD using the adapted estimates from Bayer et al. (2016). These estimates vary widely, no doubt due to the many assumptions necessary to compute figures at the aggregate level. However, they serve to give a sense of the order of magnitude of the possible environmental benefits these orders have.

There are also extensive costs associated with traffic collisions, from congestion impacts; to medical and repair bills; to loss of life. We generate rough estimates of the benefits of reduced collisions using the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration's (NHTSA) estimates that the average cost of collisions in 2013 was 17,794 USD (2010, 21,054 USD in 2020) per crash.27 When accounting for quality-of-life valuations, the estimates are an average of 61,470 USD (2010, 72,732 USD in 2020) per crash.

Our estimates in Table 5 suggest a reduction in collisions of 20%. The mean number of crashes during safer-at-home orders among treated counties was 1.4 crashes per day, implying that the counterfactual crash rate would have been about 1.77 crashes per day per county. Applying our estimates to the 124,370 county-days spent under safer-at-home policies suggests that over 219,000 collisions may have been avoided by June 30, 2020. Using the numbers from the NHTSA gives approximately 15.9 billion 2020 USD in costs avoided as a result of safer-at-home orders over that period.

A major limitation is that our estimates in Table 6 suggest that we actually see an increase in more severe collisions while the average effects are driven by reductions in less severe collisions. This means that our back-of-the-envelope calculations may overestimate the costs of collisions as while the volume of crashes is declining, the fatality rate may not be. Unfortunately, our data do not contain information about fatalities directly and therefore do not allow us examine the extent of this margin.

7. Conclusion

In many respects, safer-at-home policies have been expected and shown to have negative impacts on societies by, for instance increasing mental health distress and exacerbating the economic impacts of COVID-19. This paper represents a first step toward understanding some of the unintended positive effects safer-at-home policies have on pollution and car crashes.

We rely on a difference-in-differences framework with high frequency air pollution data and daily collision data. We find that statewide safer-at-home policies lead to a 25% reduction in PM2.5 concentrations and a 20% reduction in vehicular collisions; one of the leading causes of death in the United States. We also provide suggestive evidence that the reduction in collisions is driven in part by reduced travel associated with safer-at-home orders and by distributional changes to traffic times that also explain the increase is collision severity. We calculate that over 219,000 collisions may have been avoided by June 30, 2020, which translates to approximately $16 billion in costs avoided. The benefits from reduced air pollution could range from $154 million to $13 billion.

Our paper raises broader questions of the nuance involved in estimating the costs and benefits of safer-at-home policies. As more data on COVID-19 cases and deaths became available, it was possible to better estimate how many lives were saved (Hsiang et al., 2020). But the unintended economic consequences and large sphere of domains impacted by safer-at-home orders make it a difficult, but worthwhile, task to estimate the full set of costs and benefits of these policies.

Footnotes

We thank Mohammad Elfeitori, Ramanvir Grewal and Kelly Liu for their excellent research assistance. We declare no conflict of interest and no research funding.

See Hsiang et al. (2020) and Sanga and McCrary (2020) for similar treatment of safer-at-home orders and lockdowns.

Researchers have also begun investigating the direct effect of air pollution on COVID-19. For example, higher levels of contemporaneous air pollution were associated with increased transmission and mortality in the Chinese context by Zhang et al. (2020). This correlation is also investigated for Italy, Spain, France, Germany, U.K. and U.S. in Pansini and Fornacca (2020). If this result were to hold in our context, the benefits of safer-at-home orders reducing air pollution may also include direct reductions in COVID-19 mortality and transmission.

Leach et al. (2020) document a reduction in the closely related Canadian context.

Data are available at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-stay-at-home-order.html.

Only seven counties (Brazos, Comal, Humboldt, Kings, Mendocino, Merced and Milam) implemented an additional safer-at-home policy after a statewide policy.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Park Service, NASA, Centers for Disease Control, and tribal, state, and local air quality agencies. The centralized system provides uniform quality control and reporting consistency.

At the time of writing, the most recent data available for the AOD data was November 30, 2020, corresponding to day 335 of the year. AOD is not produced where clouds are definitively present. A quick guide to Aerosol Optical Depth can also be found from NOAA-NASA.

NOAA stands for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, an American scientific agency within the United States Department of Commerce that focuses on the conditions of the oceans, major waterways, and the atmosphere. They manage the United States operational environmental satellites.

Using the date of announcement instead of the date of implementation yields similar conclusions. State orders are announced an average of three days prior to implementation.

In a further analysis presented in the Appendix, we check the robustness of our results using simulations constructed by applying synthetic control methods to match counties based on pre-policy pollution levels. Our results are quantitatively similar, and the corresponding placebos-in-place behave as expected.

We do not provide staggered adoption estimates for collisions as these estimators are not presently available for count data, however given that the share of negative weights is similar to pollution we are optimistic that they would behave similarly to those of pollution.

Our main results are robust to conducting the analysis at the state-level rather than at the county-level. See Appendix Table A1 for the estimates.

The Environmental Protection Agency sets this standard as “Exposure to fine particle pollution can cause premature death and harmful cardiovascular effects such as heart attacks and strokes, and is linked to a variety of other significant health problems.” For example, Bowe et al. (2019) show that among a cohort of U.S. veterans, nine causes of death were associated with PM2.5 exposure above standards set by the Environmental Protection Agency.

In Appendix Tables A4 and A5 we use instead Air Quality Index (AQI) and an indicator for an acceptable Air Quality Index of below 50, respectively. Estimates are substantively the same.

Of note, once we add precipitation as a control, the point estimate becomes positive for the restricted sample. This is potentially due to the fact that precipitation could affect the estimates of AOD by inadvertently removing days with haze mistaken for cloud cover.

See Appendix Fig. A7 for leads and lags of the dependent variable Air Quality Index (AQI).

Data on the share of urban population is based 2010 Census data. Urbanization rate comes from the American Community Survey (ACS-5 years estimates).

Of note, we document that Germany's partial order also led to a large decrease in air pollution, potentially suggesting that the stringency of lockdowns might not be related to the decrease in PM2.5 concentrations. See Brodeur et al. (2021) for more details on the stringency of European lockdowns.

Deaths from motor vehicle collisions are surpassed only by heart disease, malignant neoplasms, and unintentional poisoning (both heart disease and malignant neoplasms have been connected to PM2.5 exposure).

See Appendix Table A13 for the analysis at the state-level rather than at the county-level. Our conclusions remain unchanged.

The sample includes 1711 counties. Counties with no collisions during the entire time period are excluded from the sample.

Fig. 4 confirms this pattern. This figure plots regression coefficients for collisions corresponding to number of days before/after state order issued.

Precipitation increases daily collisions in our sample, while higher maximum temperature is associated with fewer collisions - unsurprising when the sample period assigns rising temperatures to coming out of winter rather than entering into the hottest months of summer.

See Table 1 for summary statistics.

This relationship has also been shown by Google back in April 2020 (see https://www.theverge.com/2020/4/3/21206318/google-location-data-mobility-reports-covid-19-privacy).

While this may seem large, classical estimates from Harrison and Rubinfeld (1978) using data from the Boston Area following the Clean Air Act placed a WTP for a 25% reduction in air pollution at approximately 2000 (1978 USD). Other WTP estimates discussed in Chattopadhyay (1999) for particulate pollution reductions in the Chicago Area up to 366 USD in 1982-84 dollars.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2021.102427.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Adams-Prassl A., Boneva T., Golin M., Rauh C., et al. Human Capital and Economic Opportunity Working Group; 2020. The Impact of the Coronavirus Lockdown on Mental Health: Evidence from the US. Working Papers 2020-030. [Google Scholar]

- Barwick P.J., Li S., Rao D., Zahur N.B. Air pollution, health spending and willingness to pay for clean air in China. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Bayer P., Keohane N., Timmins C. Migration and hedonic valuation: the case of air quality. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2009;58(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bayer P., McMillan R., Murphy A., Timmins C. A dynamic model of demand for houses and neighborhoods. Econometrica. 2016;84(3):893–942. [Google Scholar]

- Beland L.-P., Brodeur A., Wright T. 2020. COVID-19, Stay-At-Home Orders and Employment: Evidence from CPS Data. GLO Working Paper 559. [Google Scholar]

- Bowe B., Xie Y., Yan Y., Al-Aly Z. Burden of cause-specific mortality associated with PM2. 5 air pollution in the United States. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(11) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15834. e1915834–e1915834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur A., Clark A.E., Fleche S., Powdthavee N. COVID-19, lockdowns and well-being: evidence from Google trends. J. Publ. Econ. 2021;193 doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur A., Cook N., Wright T. 2020. On the Effects of COVID-19 Safer-At-Home Policies on Social Distancing, Car Crashes and Pollution. IZA Discussion Paper 13255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur A., Gray D.M., Islam A., Bhuiyan S. 2020. A Literature Review of the Economics of COVID-19. IZA Discussion Paper 13411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur A., Grigoryeva I., Kattan L. 2020. Stay-At-Home Orders, Social Distancing and Trust. IZA Discussion Paper 13234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullinger L., Raissian K., Feely M., Schneider W. 2020. The Neglected Ones: Time at Home during COVID-19 and Child Maltreatment. SSRN 3674064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway B., Sant'Anna P.H. 2020. DID: Difference in Differences. R package version 2.0.0. URL: https://bcallaway11.github.io/did/ [Google Scholar]

- Callaway, B. and Sant'Anna, P. H.: Forthcoming, Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods, J. Econom..

- Chattopadhyay S. Estimating the demand for air quality: New evidence based on the Chicago housing market. Land Econ. 1999:22–38. [Google Scholar]

- Chay K.Y., Greenstone M. Does air quality matter? Evidence from the housing market. J. Polit. Econ. 2005;113(2):376–424. [Google Scholar]

- Cicala S., Holland S.P., Mansur E.T., Muller N.Z., Yates A.J. 2020. Expected Health Effects of Reduced Air Pollution from COVID-19 Social Distancing. NBER Working Paper 27135. [Google Scholar]

- Currie J., Davis L., Greenstone M., Walker R. Environmental health risks and housing values: evidence from 1,600 toxic plant openings and closings. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015;105(2):678–709. doi: 10.1257/aer.20121656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang H.-A. H., Trinh T.-A. Does the COVID-19 lockdown improve global air quality? New cross-national evidence on its unintended consequences. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2021;105:102401. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2020.102401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Chaisemartin C., d'Haultfoeuille X. Two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020;110(9):2964–2996. [Google Scholar]

- Deschênes O., Greenstone M., Shapiro J.S. Defensive investments and the demand for air quality: evidence from the NOx budget program. Am. Econ. Rev. 2017;107(10):2958–2989. [Google Scholar]

- Dingel J.I., Neiman B. 2020. How Many Jobs Can Be Done at Home? NBER Working Paper 26948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle S., Stromme J., Zhou A. Staying at home: mobility effects of covid-19. CEPR Covid Economics. 2020;4:86–102. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman-Bacon A., Marcus J. 2020. Difference-in-Differences to Identify Causal Effects of COVID-19 Policies. (DIW Berlin Working Paper) [Google Scholar]