Abstract

Ewing sarcoma is an aggressive pediatric tumor of the bone and soft tissue. The current standard of care is radiation and chemotherapy, and patients generally lack targeted therapies. One of the defining molecular features of this tumor type is the presence of significantly elevated levels of replication stress as compared to both normal cells and many other types of cancers, but the source of this stress is poorly understood. Tumors that harbor elevated levels of replication stress rely on the replication stress and DNA damage-response pathways to retain viability. Understanding the source of the replication stress in Ewing sarcoma may reveal novel therapeutic targets. Ewing sarcomagenesis is complex, and in this review, we discuss the current state of our knowledge regarding elevated replication stress and the DNA damage response in Ewing sarcoma, one contributor to the disease process. We will also describe how these pathways are being successfully targeted therapeutically in other tumor types, and discuss possible novel, evidence based therapeutic interventions in Ewing sarcoma. We hope that this consolidation will spark investigations that uncover new therapeutic targets and lead to the development of better treatment options for Ewing sarcoma patients.

Introduction

Cancer is the leading cause of death in children and adolescents(1) and Ewing sarcoma is the second most common bone malignancy in these populations, with a peak incidence at the age of 14(2). Although it is also sometimes found in soft tissue, Ewing sarcoma predominantly presents in bone. Upon confirmed diagnosis, patients will generally initiate treatment with multi-agent chemotherapy to reduce the burden of primary disease and eradicate subclinical micrometasteses. This regimen includes anthracyclines, vinca alkaloids and alkylating agents such as Etoposide, Vincristine, Doxorubicin, Ifosfamide, and cyclophosphamide(3). Neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy is followed by localized control of the primary tumor with surgical debulking. Patients often then receive additional consolidation chemotherapy and subsequent radiotherapy to surgical margins and metastatic disease sites. This strategy for the treatment of localized disease has proven very effective and resulted in an overall 5-year survival rate of approximately 75%. Unfortunately, response rates are variable in patients with metastatic disease and recurrence is common following a short disease-free interval(3,4). These patients tend to have more chemotherapy resistant disease, and patients with relapsed/refractory disease generally have poor outcomes, especially those who relapse within 2 years of completion of treatment (survival ~15–20%.)

Molecularly, Ewing sarcoma is primarily characterized by the presence of a balanced chromosomal translocation that fuses the Ewing sarcoma breakpoint 1 gene (EWSR1; member of the FET (FUS, EWS and TAF15)-family of RNA-binding proteins) to an ETS transcription factor gene to create what is known as an EWS-ETS fusion(5). Although EWS-ETS fusion-negative Ewing sarcoma cases have been reported, recent RNA sequencing-based profiling determined these rare sub-types to be biologically distinct from EWS-ETS driven Ewing tumors(6). The most common EWS-ETS fusion is EWS-FLI1 (present in >85% of cases) which is formed when exons 1–7 of EWSR1 fuse to either exons 5–9 (type I) or 4–9 (type II) of FLI1 (Friend Leukemia Integration Site 1)(5,7). This translocation results in the production of a chimeric fusion protein that harbors the DNA binding domain of the FLI1 transcription factor and the N-terminal domain (NTD) of EWSR1. The NTD of EWSR1 has been shown to interact with several members of the spliceosome and members of the RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) complex such as TFIID and subunits of RNAPII (8,9). The remainder of the EWSR1 protein (the portion lost in the fusion) harbors several RNA binding domains that facilitate interactions between RNA and single-stranded DNA (ssDNA)(10–12). For these reasons, EWSR1 is thought to be involved in RNAPII-dependent co-transcriptional mRNA processing(13). Importantly, however, it has been shown that when bound to the DNA binding domain of a transcription factor, the NTD of FET-family proteins can act as potent activators of transcription(5). Therefore, it is not a surprise that the EWS-FLI1 fusion protein acts as an aberrant transcription factor, upregulating several FLI1 target genes as well as novel, EWS-FLI1-specific genes(14–16). It is this aberrant transcription factor activity that has long been thought to be the main oncogenic characteristic of this fusion.

RNAi-mediated depletion of the fusion protein is lethal to Ewing sarcoma cells (17,18). Therefore, direct inhibition of the fusion protein has been considered as a potential treatment strategy for Ewing sarcoma, but unfortunately, drug development to identify and/or synthesize small molecule inhibitors for the direct targeting of the fusion protein has not been successful(19,20). The inability to target these proteins is at least in part due to the presence of partially unstructured regions that hinders structural characterizations. FET oncoproteins harbor low complexity domains and unstructured regions that are implicated in aggregation behavior in the native full-length non-fusion proteins(21). In addition to the aberrant transcription factor activity of the fusion protein, aggregation may be a key mechanism of how the fusion protein functions in disease states, and aggregation behavior may play a role in association of the fusion proteins with RNA, protein: protein interactions, induction of genomic instability, and downstream epigenetic remodeling. More detail on the aggregation behavior of EWS and EWS fusion protein can be found in box 1.

Box 1. Aggregation Behavior of EWS and EWS fusion proteins.

The aggregation behavior of EWS is modulated by an N-terminal low complexity (LC) prion-like domain, and resultant phase transition behavior is linked to protein aggregation and multiple disease processes(21,176–178). In Ewing sarcoma, aggregating behavior of both native EWS and EWS-FLI1 in vitro has been reported, with the aggregation of the fusion product presumed driven by the LC domain of EWS, whereas non-translocated native FLI1 retains solubility(176). Fibrillar structure formation in FETs is due to both the arginine-glycine-glycine (RGG) rich regions and LC domains, especially the repetitive [S/G]Y[S/G] motifs in the LC domains(179). The impact of these conserved motifs hinges on the behavior of the tyrosine residues. Serine replacements of multiple tyrosines diminish fibrillization, and total tyrosine-to-serine replacement fully abrogates fibrillization of EWS-FLI1 in vitro and removes its pioneer and enhancer activity(21). It has also been observed that polymeric fibers formed from LC domains directly bind the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II(180), providing a possible mechanism for the fusion proteins’ role in transcriptional deregulation seen in soft tissue sarcoma if they retain similar activity to their native counterparts. In addition, recent work has discussed the potential for protein aggregates to accelerate genomic instability due to compromised proteome integrity. The increasingly unstable proteome has potential for spiraling into loss of efficiency of DNA maintenance and repair due to attrition of the genome-stabilizing protein machinery leading to progressive increase in stress(71). The propensity for the partially unstructured Ewing’s fusion oncoproteins to self-assemble due to the LC domains, and the role of the RGG domains retained in EWS fusion constructs, suggests a role for protein fibrillization in genomic instability and stress induction.

Due to the unstructured nature of the fusion protein, identifying targetable regions within its structure using modern biochemical approaches is problematic (22). To complicate things further, being a pediatric cancer, these tumors are relatively void of other genetic alterations, with only ~5% harboring TP53 mutations(23,24). Apart from the gene fusion, the next most common genetic aberration is within the STAG2 gene (stromal antigen 2), which is present in ~15–40% of tumors (24,25). STAG2 plays a key role in DNA repair, and STAG2 mutation is associated with a worse prognosis in these patients(26).

Unfortunately, targeting these tumors based on vulnerabilities conferred by common mutations is not currently a viable therapeutic strategy. Although a significant amount of progress has been made towards understanding the molecular mechanisms that contribute to Ewing sarcoma, very little headway has been made towards the development of targeted therapies(27,28). As a result, the standard of care is non-specific to the diseased cells and is often accompanied by a number of debilitating side effects that can dramatically impact the patient’s quality of life(2). Considering that this is predominantly a childhood cancer, it is especially important to limit the susceptibility of the patients to chemotherapy-induced secondary disease. Unfortunately, about 10% of Ewing sarcoma survivors will succumb to treatment-associated secondary cancers at some point in their life, and a larger proportion will develop other long-term complications such as cardiomyopathy and infertility(29–31). As a result, there is a desperate need for the development of novel therapeutic options that will inhibit the progression of recurrent and metastatic tumors while limiting treatment-associated toxicity and secondary disease.

Recent work within the field has alluded to the presence of high levels of replication stress within Ewing sarcoma cells, the source of which is poorly understood. Oncogene-induced replication stress is quickly becoming recognized as a significant source of genomic instability within cancer cells and is thought to play a role in the very early stages of oncogenesis(32). It can be caused by a variety of different mechanisms including, but not limited to, the presence of RNA:DNA hybrids (R-loops) formed during transcription, protein-barriers that impede the movement of the helicase/polymerase, and exhaustion of nucleotides caused by a deregulation in nucleotide synthesis/consumption (reviewed in (33)). All these things have the ability to slow or stall the progression of the complex molecular machine that carries out replication of DNA, otherwise referred to as the replisome, and it is this event that defines replication stress. While the slowing/stalling of the replisome can lead to un-replicated DNA and errors during mitosis(34,35), another major source of the genomic and chromosomal instability from replication stress arises from the formation of toxic DNA intermediates, mainly long strands of ssDNA. These structures form between the MCM2–7 helicase complex and the DNA polymerase when the progression of the polymerase is delayed (36). Replication stress-induced ssDNA is vulnerable to endonuclease-mediated degradation and its persistence can result in the collapse of the replication fork and double strand break (DSB) formation. DNA breaks as a result of replication stress can lead to the acquisition of point mutations, chromosomal translocations, and deletions of regions near the stress, all of which arise as a result of errors during DNA repair(33).

Elevated levels of replication stress are a significant source of genomic instability in cancer and thought to play a direct role in cancer progression, but it is also presents a unique opportunity within these cells (37). Inducing replication stress within cancer cells that already harbor a large amount of it or targeting the replication stress-response (RSR) has proven to be a very efficacious treatment strategy for some cancers(38). Therefore, we believe it is crucial to determine the source of the replication stress within Ewing sarcoma cells in order to reveal novel vulnerabilities that can be exploited.

In this review, we discuss the process of eukaryotic replication, sources of replication stress, the Replication Stress Response, and recent work showing the efficacy of targeting replication stress in cancer. We will also discuss evidence that supports the presence of replication stress within Ewing sarcoma cells, highlighting some of the key studies that provided vital information on this topic and providing insight into potential therapeutic targets and drug combinations based on the findings.

Dynamics of Eukaryotic Replication

DNA replication is a highly regulated process that ensures that the genome is fully duplicated once and only once per each cell division cycle(39). Fluctuations in the activities of cyclin dependent kinases (CDK) and the anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) control the progression through the cell cycle and the dynamics of DNA replication(40,41). In cycling eukaryotic cells, preparing for DNA replication begins directly following mitosis (39,42). In late M-phase and throughout G1, during times of low CDK activity, thousands of MCM2–7 helicase complexes are loaded onto DNA at various sites throughout the genome. This is done through the actions of the Origin Recognition Complex (ORC) (OCR1–6), cell division cycle 6 protein (CDC6) and Chromatin Licensing and DNA replication factor 1 (CDT1) in a process known as origin licensing (42). The multi-protein complex that is formed is known as the pre-replication complex (pre-RC) and the loci at which they are bound are termed “licensed origins”. Licensed origins can become active replication forks and sites of DNA synthesis upon entry into S-phase (43,44). The genomic regions that are to become licensed origins are not well defined in eukaryotic cells. Several factors play into this including euchromatin formation, transcriptional density, and sequence dependency; the contribution of the DNA sequence is thought to be relatively small (39,45).

Origin firing takes place when CDK activity rises at the G1/S transition. During this period, CDK2-cyclinE and CDC7-DBF4 (DDK) kinases phosphorylate several components of the replisome, including members of the MCM2–7 helicase complex itself (46–48). Once phosphorylated, the pre-RC is recognized and bound by two important factors, CDC45A and the GINS complex. This binding, along with the binding of several other factors including MCM10, RECQL4, Treslin and TOPB1 converts the pre-RC into an active replication origin. At this point, bidirectional unwinding of the DNA duplex by the MCM2–7 helicase complexes commences and the leading and lagging strand DNA polymerases, Pol-epsilon and Pol-delta respectively, begin to catalyze the synthesis of DNA (49). Unimpeded by replication blockades, the replication fork will continue to expand in a symmetrical, bidirectional manner away from the initial site of activation until it meets an oncoming replication fork or the end of a chromosome. At this point, replication is terminated.

The specific origin clusters that become activated are thought to be dictated by two key things: transcriptional density and the 3-dimensional architecture of the surrounding chromatin (50,51). Origins located within regions of euchromatin and are permissive for transcription (ie. near genes that are readily/actively being transcribed) generally fire early in S-phase. This is likely because these regions are easily accessed by replication factors and have a higher probability of being recognized and acted upon. Then, during late S-phase, origins located in non-permissive, heterochromatic regions will become accessible to replication factors and become active due to the changing chromatin environment that occurs as replication progresses, if the regions have not already been replicated by passage of a replication fork from an adjacent earlier firing origin. Although chromatin architecture is considered to be an epigenetic factor affecting origin firing, it is possible that other epigenetic influences can affect the rate and timing of origin firing such as DNA methylation patterns(52) and histone modifications(53,54).

There are far more licensed origins than origins that eventually become activated or “fire” (55). Only a small number of the licensed origins within any given replication cluster are activated. The un-used origins are termed “dormant” and are thought to serve as back-up in case cells undergo replication stress and active replication forks stall or collapse (56,57). Several years ago it was shown that, in response to fork slowing by treatment with replication inhibitors, the level of active origins within replication clusters increases dramatically (58) indicating the activation of dormant origins. It is important to point out that dormant origins are separate from late-firing origins. Late-firing origins refers to origins within replication clusters that replicate in late-S phase. The firing of late-firing origins is inhibited during replication stress by the ATR and CHK1 kinases (59–61) while dormant origins are activated. Determining the mechanisms that lead to the simultaneous activation of dormant origins and inhibition of late-firing origins during times of stress is still an area of active investigation. It is possible that a signaling cascade, stimulated by a stalled replication fork, forces the firing of nearby dormant origins in a deliberate attempt to rescue the replication of the local regions. However, it is also possible that the dormant origins would have normally been inactivated by the passive replication by an adjacent fork. Then, if a fork stalls, the replication stress kinases disperse throughout the nucleus, inhibiting late-firing origins while sparing local origins from active inhibition, allowing them to eventually fire.

Replication Stress: Sources and Responses

Replication stress is a significant source of genomic and chromosomal instability and is known to be a major contributing factor to the oncogenesis of several types of cancer. It has even been shown to be present in very early forms of precancerous lesions (62). Replication stress is ill-defined, with no single event or response that signifies its presence. It is generally referred to as the slowdown of DNA synthesis and/or the complete stalling of the progression of replication forks (33). In cancer, aberrant oncogene activity or the loss of certain tumor suppressor gene functions usually cause deregulation of proper replication dynamics. When this happens, there are several things that pose threats to progression of the replication fork:

Increases in transcription lead to a higher likelihood of collisions between DNA and RNA polymerase complexes (63)

Increased replication rates due to deregulated origin firing lead to depletion of required resources such as dNTPs and DNA repair enzymes (64,65)

Formation of RNA:DNA hybrids (R-loops) due to increases in transcription or defects in RNA processing (16,66,67)

Deregulation of the replication licensing program resulting in re-replication (due to unrestricted licensing during S-phase) or a lack of dormant origins (due to a decreased licensing during G1) (68–70)

Large regions of heterochromatin due to epigenetic instability (reviewed in (71))

Prevalence of DNA secondary structures such as G-quadruplexes due to expansion of repetitive sequences, defects in DNA repair, or defects in specialized helicase function (72–76)

A common outcome of replication stress is the generation of long strands of ssDNA between the MCM2–7 helicase complex and the DNA polymerase (note: not all sources of replication stress result in ssDNA formation) (77). Some forms of replication stress directly hinder the processivity of the polymerase, instantly creating a functional but not physical separation from the helicase. Some of these sources, including dNTP depletion, stall the polymerase without initially affecting helicase progression. These structures are toxic to the cell and can lead to the generation of double-stranded DNA breaks. Errors during the repair of these DNA breaks can result in the acquisition of mutations, chromosomal rearrangements, and chromosome mis-segregation resulting in aneuploidy (33).

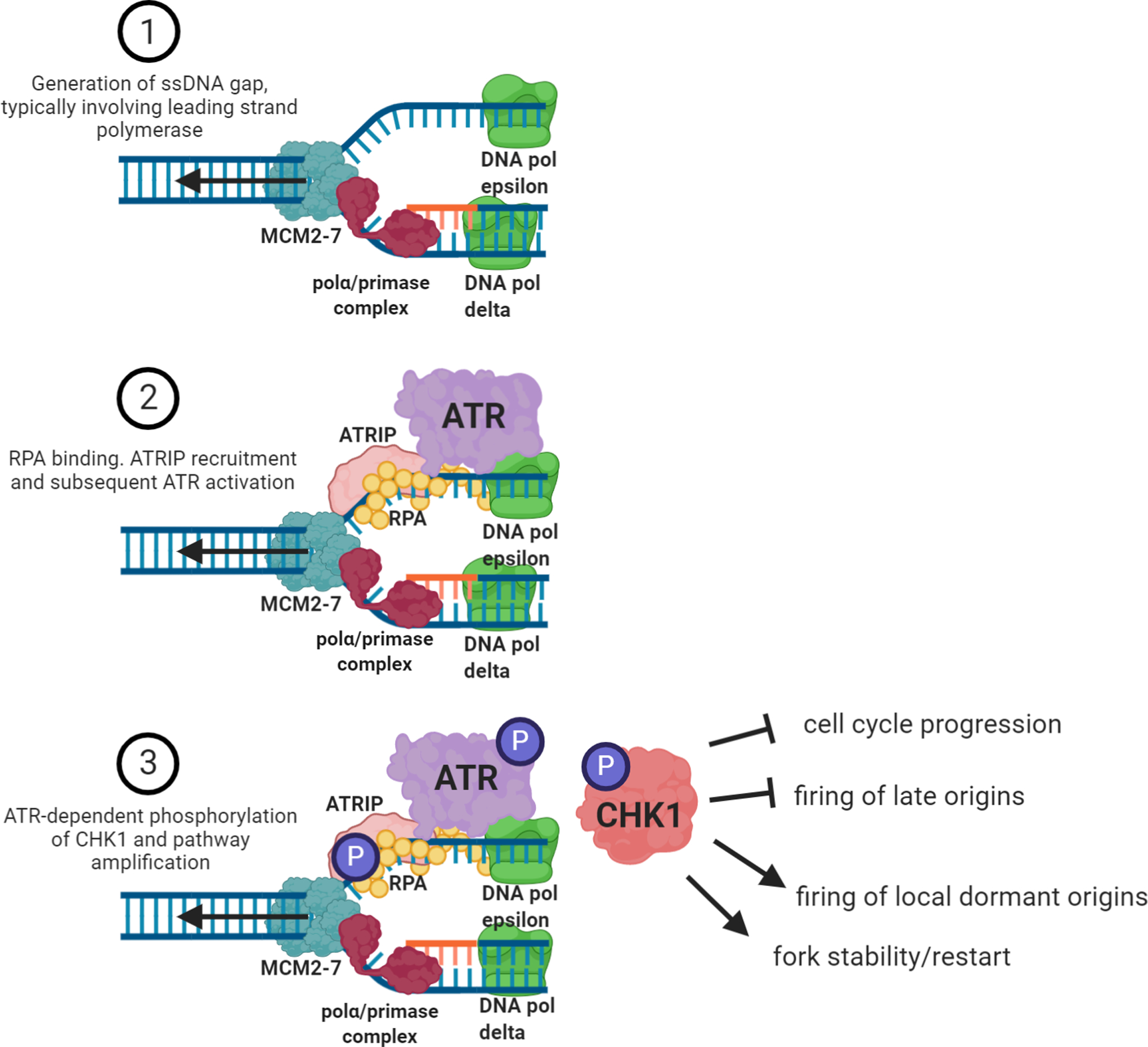

The replication-stress response (RSR) is the main way that the cell combats these deleterious effects (fig. 1). Single stranded DNA molecules (ss-DNA) are generated between the helicase complex and the polymerase either by a delay in polymerase progression or resection of DNA due to replisome pausing. The stretches of ssDNA are recognized by the ssDNA-binding complex RPA (heterotrimer consisting of RPA1, 2 and 3). This ssDNA-RPA complex is the activating substrate that recruits several proteins including the ATR-interacting protein (ATRIP), the RAD9-RAD1-HUS1 clamp complex (9-1-1 complex), and the Ewing tumor-associated antigen 1 (ETAA1) to the sites of replication stress. The recruitment of these proteins facilitates the binding of the ATR kinase (ATM and Rad3-related kinase), the main kinase that coordinates the RSR pathway, to the sites of the stress (78). Upon recruitment to DNA, ATR directly phosphorylates and activates its effector kinase CHK1 along with other kinases including ATM and DNA-PK (79). It also phosphorylates several other components of the RSR complex including the histone variant H2AX (gamma-H2AX) and RPA (80). Once activated, this pathway works to alleviate the replication stress by inhibiting the progression through the cell cycle, inhibiting the firing of any other replication origins to prevent additional ssDNA formation while simultaneously promoting the firing of nearby dormant origins in an attempt to seal the gap between an adjacent origin, stabilizing the stalled replication fork and promoting fork restart (33). All these functions are carried out to ensure the complete and accurate duplication of the genome. Any disruptions to this process result in replication stress and genomic instability.

Figure 1. Canonical activation of the ATR-CHK1 signaling pathway.

In its simplest form, the ATR-CHK1 pathway consists of three main steps. The first is the generation of ssDNA gap between the MCM2–7 helicase complex and the DNA polymerase. The generation of ssDNA gap can occur on either leading or lagging strand but most often occurs on the leading strand due to the discontinuous nature of lagging strand synthesis. Then, the ssDNA is recognized and bound by the heterotrimer RPA complex which is the substrate that facilitates the binding of the ATR-interacting protein, ATRIP. ATRIP binding catalyzes the recruitment of the ATR kinase to the site of the stalled fork. ATR binding to chromatin facilitates the activation of its kinase activity. Active ATR phosphorylates several substrates including RPA2, ATR itself and, most importantly, CHK1 kinase. Once phosphorylated by ATR, CHK1 disperses throughout the nucleus, amplifying the signaling cascade. The four main objectives of this pathway are to inhibit the progression of the cell cycle, halt the firing of any late-firing replication origins, promote the initiation of replication from local dormant origins, contributing to various DNA repair pathways, while stabilizing and allowing for the restart of the stalled replication fork.

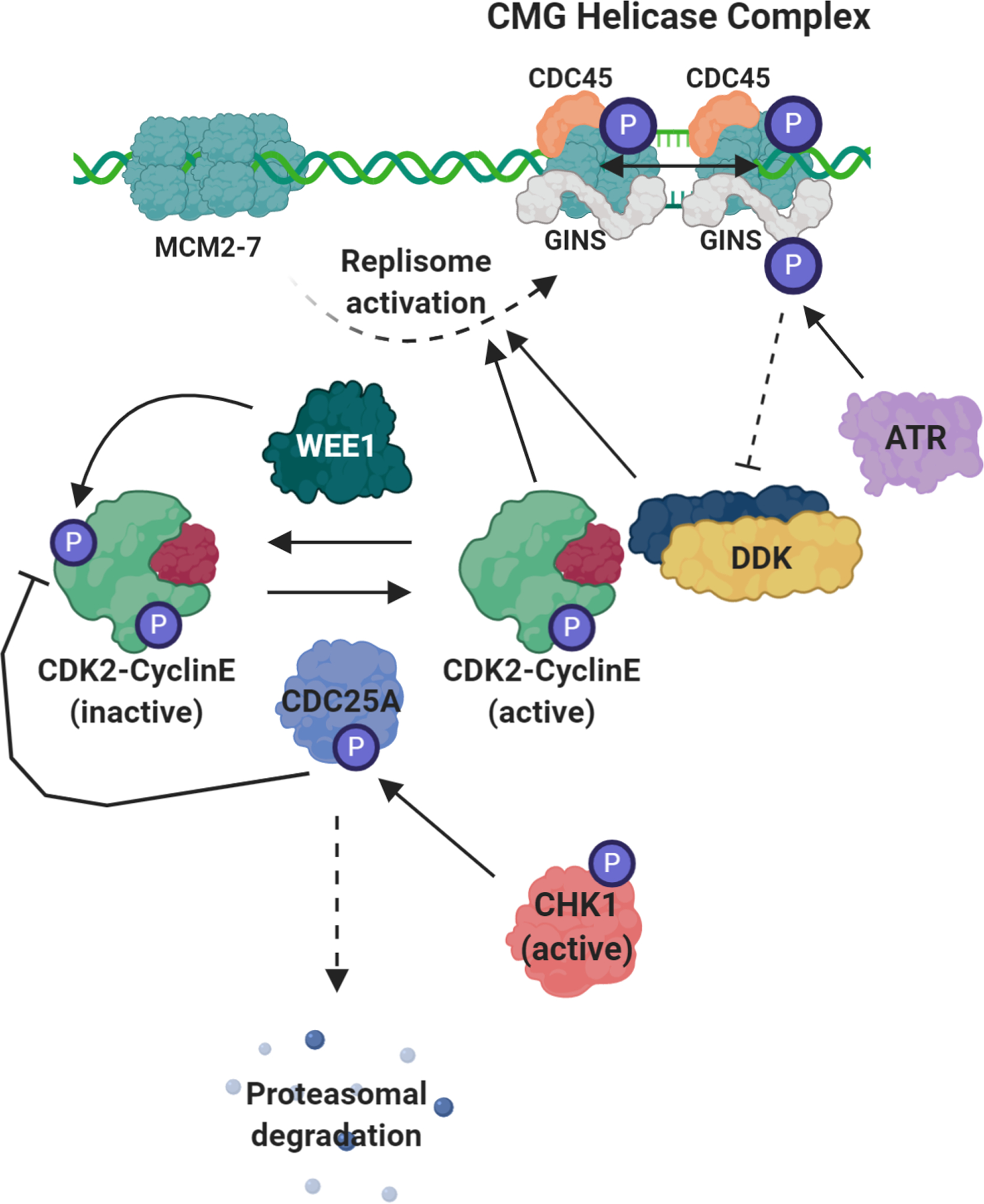

Even in the absence of replication stress signal, the RSR kinases, ATR and CHK1, work to limit the potential for replication stress by restricting origin firing (fig. 2). This is done by indirectly inhibiting the kinase activities of CDK2-cyclinE and CDC7-DBF4 (DDK) (59–61,81). CHK1, once activated by ATR, phosphorylates CDC25A and targets it for degradation by the proteasome. CDC25A is a phosphatase that regulates the phosphorylation level of several CDKs, including CDK2. Active CDC25A works to remove the WEE1-mediated inhibitory phosphorylation on CDK2, rendering the enzyme functional (61,81). Also, ATR-dependent phosphorylation of the GINS complex inhibits the interaction between the pre-RC and CDC7. This inhibits CDC7’s ability to phosphorylate the MCM2–7 helicase complex, limiting origin firing (59,60). However, if this program is disrupted, there is an enhancement of CDK2 and CDC7 activity, resulting in unscheduled origin firing. Unscheduled origin firing not only results in a lack of dormant origins and genomic instability (56), but it also increases the potential for the generation of ssDNA and further RSR activation.

Figure 2. ATR-CHK1-WEE1 role in the regulation of replication origin firing.

Even in the absence of replication stress, the enzymes involved in the replication stress response work to limit the level of origin firing by directly and indirectly inhibiting the kinase activity of CDK2-cyclin E and CDC7-DBF4 (DDK). The activation of the replisome requires to main events; the binding of CDC45 and the binding of the GINS complex. Along with the MCM2–7 helicase, the complex formed between CDC45 and GINS is referred to as the CMG helicase complex (CDC45-MCM2–7-GINS helicase complex). The recruitment of CDC45 and GINS requires CDK2- and DDK-mediated phosphorylation of the MCM2–7 helicase. WEE1 mainly works to phosphorylate and deactivate the CDK2-cyclin E complex. This phosphorylation is actively removed by the APC/CDC25A phosphatase complex. Active CHK1 phosphorylates CDC25A, marking it for degradation by the proteasome, indirectly inhibiting the activity of CDK2. ATR directly phosphorylates GINS inhibiting DDK binding, hindering DDK kinase activity and limiting its ability to phosphorylate and active the replisome.

Interestingly, the enzymes involved in the RSR are rarely mutated or deleted in cancer. For example, only ~3% of cancers harbor genetic alterations in ATR and <1% in CHEK1 and WEE1 (cbioportal.org). This suggests that the ablation of this pathway would not produce beneficial genomic instability for cancer cells. In fact, it is highly likely that a non-functional RSR would lead to cell death in cancer cells. Homozygous deletion of ATR is embryonic lethal (82), and induction of this loss in adult animals leads to rapid aging and a loss of stem cell populations (83). This highlights the essential role that the ATR-mediated RSR plays in cellular homeostasis, especially in highly proliferative cells. Also, the inhibition of these enzymes has proven efficacious in the treatment of many cancers, suggesting that these pathways retain functionality in these tumors (38). It would seem then, that the persistence of the replication stress seen in cancer cells is likely due to the saturation of this pathway and not its ablation, and that the pharmacological inhibition of the RSR may be an efficacious therapeutic opportunity, especially in tumors with high levels of basal replication stress. This also suggests that higher levels of these enzymes in certain cancers could indicate the presence of high levels of replication stress and could be used as a biomarker to predict sensitivity to inhibitors of the RSR (i.e. ATR/CHK1 inhibitors).

Targeting the Replication Stress Response (RSR) in Cancer

Inducing replication stress and/or targeting the RSR for cancer treatment has recently become the focus of intense investigation (38,62). Classic chemotherapeutic agents exert their effect by disrupting proper cell division. This is usually done by interfering with microtubule dynamics during mitosis or by directly (inhibiting DNA polymerases) or indirectly (creating DNA lesions/inhibiting topoisomerases) disrupting the process of DNA replication (84). Regardless of their mechanism of action (MOA), traditional chemotherapeutic drugs target highly proliferative cells. This is, theoretically, very effective because within a cancer patient, the cancer cells are among the most highly proliferative cells within the body. However, there are two clear problems. First, the cancer cells are not the only highly proliferative cells within the body. Hematopoietic cells within the bone marrow as well as the cells of the epithelial lining of the gut and intestines are rapidly dividing and will be equally as susceptible to treatment with “anti-proliferative” drugs. This is the basis for most cancer therapy-associated toxicities such as nausea, vomiting, mucositis, and immunosuppression. Second, tumors are incredibly heterogenous. Even within the same tumor, there is a significant degree of cellular heterogeneity. This results in a variety of different responses to chemotherapy, especially when the MOA is not directed towards a specific aspect of the tumor. Targeted therapy, however, is different from classical chemotherapy. Not only is the MOA of the drug (thought to be) known, it is used deliberately to target a known aspect of the tumor biology. This is ideal for obvious reasons – limited toxicities and more uniform responses to treatment – however, to develop targeted therapies, researchers must identify certain vulnerabilities within tumors that can be targeted. One of the first and best understood targeted therapies used for cancer treatment was the selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) Tamoxifen. Since its approval in 1998, it has been used to treat millions of woman and men with ER+ breast cancer. Other targeted therapies such as the development of Imatinib (Gleevac) for the treatment of BCR-ABL fusion-positive chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) (85) and the use of EGFR-RTKIs for EGFR mutant lung cancers have revolutionized treatment for some patients.

The utilization of small molecule inhibitors that target members of the RSR has recently been the focus of much research (38,86). The rationale for this approach is that the inhibition of the RSR should lead to the accumulation of lethal levels of replication stress and genomic instability, resulting in conditions incompatible with cell viability. The results of these studies have been promising for many cancer types. Inhibitors of ATR, CHK1 and WEE1 have been shown to be efficacious as single agents in the treatment of several forms of cancer including Ewing sarcoma (87), MYC-driven lymphoma (88), p53- and ATM-deficient tumors (89) and certain subsets of lung cancer (90). There are several inhibitors of WEE1, CHK1 and ATR that are in various stages of clinical trials (91). While these agents are efficacious as single agents, combining them with traditional chemotherapy or radiotherapy seems to work much better. For example, administration of the ATR inhibitor AZD6738 potentiated the anti-tumor efficacy of cisplatin in ATM-deficient non-small cell lung cancer(92). AZD6738 has also been shown to increase the radio-sensitivity of several cancer cell lines, independent of TP53 or BRCA status(93). This is likely because traditional chemotherapy or radiotherapy disrupts DNA replication and increases the cell’s dependency on the RSR. Therefore, the inhibition of the RSR potentiates the effects of the chemotherapeutic agent, rendering it more effective. The targeting of the RSR in cancer treatment has been recently reviewed (38).

Replication Stress in Ewing sarcoma

As mentioned above, apart from alterations in dosages and timing of treatment, the treatment of Ewing sarcoma has not changed significantly in the past 60 years; with the combination of surgery, radiotherapy and multi-agent chemotherapy still being the standard of care (94). This has proven to be a relatively effective treatment strategy for patients with primary and local disease, and the 5-year survival rate is ~75%. However, there are two major problems. First, patients that present with metastatic disease and patients that develop recurrent tumors do not typically respond to standard of care and only ~30% will live past 5 years. Second, Ewing sarcoma patients tend to be very young (peak incidence is at age 14). The radiotherapy and multi-agent chemotherapy regimen that are administered render these patients susceptible to developing treatment-associated secondary disease. Together, these factors mean that it is very important that research be done to identify unique vulnerabilities within the tumors and develop targeted therapy for the patients. Targeting the RSR has proven to be a very effective treatment strategy in certain cancers, especially those that display high levels of endogenous replication stress. Here, we describe the evidence that has accumulated suggesting that Ewing sarcoma tumors harbor large amounts of replication stress and are also potentially vulnerable to the inhibition of the RSR. While we believe effects of replication are likely to play a role in the development of this disease, Ewing sarcomagenesis is complex. Without minimizing the many factors driving tumorigenesis, including factors such as the role of EWS-FLI1 expression level and metastatic spread, the primary goal of the remainder of this review is to focus evidence on the intriguing possibility that replication stress may be a unique entry point for therapeutic intervention in Ewing sarcoma. For additional information regarding Ewing sarcoma etiology, we direct the reader to the following reviews (2,95).

BRCA1-deficient phenotype

BRCA1 & BRCA2 function in the DNA repair pathway and are required for proper homologous recombination (HR)-mediated DSB repair (96). Mutations to either of these genes result in improper DNA repair, genomic instability and cancer predisposition (96). Roughly 30% of hereditary breast and ovarian cancers harbor mutations in BRCA1/2 (97), and for cancer-free individuals with identified mutations in BRCA1/2, the lifetime risk of cancer development is 50–80% (98). It has recently been shown that Ewing sarcoma cells display a functional impairment of the BRCA1 protein and, as such, are expected to be deficient in HR-mediated repair (16). Gorthi et al. showed that WT EWSR1 negatively regulates CDK7/9-dependent phosphorylation of the RNAPII C-terminal tail and therefore limits RNAPII’s transcriptional activity; this function is impaired by the EWS-FLI1 oncoprotein. Interestingly, BRCA1 is able to recognize and associate with phosphorylated RNAPII (99). The increase in active transcription that is caused by the EWS-FLI1 fusion forces retention of BRCA1 at RNAPII complexes and hinders its ability to initiate HR-mediated repair (16). However, a group previously showed that depletion of XRCC4 (required for non-homologous end joining) within Ewing cells does not attenuate the basal level of DNA damage (100), suggesting functional HR-mediated repair. Furthermore, two independent studies investigating the basis for PARPi sensitivity in Ewing cells found that depletion of PARP1 rescues Ewing cells from Olaparib-induced cell death; implicating PARP trapping as the main mediator of PARPi-induced cell death. This was an intriguing result. BRCA1/2-mutant tumors harbor high levels of PARP1 and rely on its activity to maintain genomic stability and cell viability. To this end, PARP1 is overexpressed in Ewing cells, suggesting an increased requirement for its activity (101,102). However, the genetic ablation of PARP1 is not toxic to Ewing tumors. Instead, PARPi-mediated PARP trapping is responsible for the cytotoxic effects (103). This suggests that Ewing tumors do not have an increased reliance on PARP1 function but rather, are sensitive to the deleterious effects of PARP trapping. Importantly, PARP1 expression levels have been shown to dictate cellular responses to PARPi, suggesting that overexpression of PARP1 can sensitize cells to PARPi (104). This could mean that Ewing tumors are sensitive to PARP1 inhibitors simply due to the increased expression of the enzyme and therefore, increased PARP trapping. Then, because EWS-FLI1 is responsible for the increased PARP1 expression (101,102,105), reduced expression of the fusion or PARP1 would confer resistance to PARP inhibitors. At first glance, this challenges the idea that Ewing tumors are HR-deficient, for they do not rely on a functional PARP1 to maintain viability. However, studies investigating the relationship between PARPi and BRCA1/2 mutations have found that PARPi-mediated PARP trapping, that typically occurs at the initiation of base excision repair, causes replication fork stalling (106). Cell viability relies on the faithful resolution of this fork stalling which is dependent on BRCA1/2. This supports the idea that Ewing sarcoma cells are, in fact, HR-deficient.

Nonfunctional HR machinery would have severe consequences on replication fork stability and fork progression. RAD51 filament formation on the reversed strand of reversed forks is a common replication intermediate in response to genotoxic stress (107). These filaments are required to facilitate strand invasion and HR-mediated fork restart upon fork stalling. BRCA1/2 play an important role in the stability of these filaments and are required for proper HR-mediated repair in this context (108). In the absence of proper BRCA1/2 function, RAD51 foci do not form in response to replication stress and HR-mediated fork restart is not possible. This forces the cell to resort to alternative means of resolution such as MUS81-dependent fork processing (109,110). This alternative method results in the production of a double-strand DNA break and can result in genomic rearrangements. This is thought to be the basis for the genomic instability seen in the BRCA1/2-mutant tumors. To this end, Gorthi et al. did not observe an induction of RAD51 foci upon ionizing radiation in Ewing sarcoma cells (16) suggesting a deficiency in this process. Therefore, it would be interesting to investigate the contribution of MUS81 nuclease activity to the basal level of DNA damage that is seen in Ewing tumors. Also, MUS81-mediated fork processing may prove to be a potential drug target, as this pathway is likely required for replication completion in Ewing cells.

HR-mediated fork restart is one mechanism that eukaryotic cells utilize to recover from replication fork stalling (111,112). When this is impaired, the utilization of dormant origins for replication stress recovery is also very crucial. This is important because it has been shown that impeding origin licensing, by depleting cells of CDC6 and/or CDT1, reduces the number of dormant origins and renders cells sensitive to replication blockage (56). The increased dependency on the use of dormant origins due to HR-deficiencies could render Ewing cells ultra-vulnerable to origin licensing impediments. While there are currently no inhibitors of CDC6 or CDT1, there is a class of small molecules, 2-Arylquinolin-4-Amines (2A4A), that have been shown to inhibit the interaction between the ORC complex and DNA, disrupting the origin licensing program (113). Perhaps the use of a 2A4As would potentiate the effects of replication-inhibiting chemotherapeutic agents (i.e. Hydroxyurea, Aphidicolin etc.) for the treatment of Ewing sarcoma. This is an area that has not been investigated to date.

STAG2 mutations

Stromal Antigen 2 (STAG2) is one of four components of the cohesin complex, and this protein predominantly plays a role in sister chromatid cohesion and segregation(114,115). The cohesin complex is highly conserved from yeast to vertebrates and is comprised of four major subunits. The complex forms a ring structure that adheres sister chromatids during and after DNA replication in S phase of the cell cycle. While it has been confirmed that STAG2 mutation and inactivation is a common occurrence in Ewing sarcoma(23,24), the consequences of mutant STAG2 remain controversial across tumor types. Loss of STAG2 has led to significant changes in chromosome number in certain cell lines, while in others, aneuploidy is not induced, or results remain inconclusive. At this time, results on cellular migration, invasion, proliferation, and apoptosis are limited, warranting additional studies before a definitive conclusion can be made about the role of STAG2 in human malignancies. There is ample evidence, however, to argue for a role of STAG2 in replication stress and the DNA damage response. During G2 phase and progressing into mitosis, cohesin is removed from chromosomes except for at the centromeres. When it comes time for sister chromatids to separate so two daughter cells can be formed, the remaining cohesin is compromised(116). The cohesion complex also plays a role in the regulation of genomic organization, transcription and DNA repair(117–121). The exact mechanism by which these proteins influence transcription is unknown, however formation of the ring complex cohesin can bring distant regions of the genome into proximity. Cohesin has been shown to interact and co-localize with known transcriptional regulators including CTCF and mediator, and may be able to initiate or inhibit transcription by recruiting enhancers or silencers to gene promoters(117,122–126). This DNA looping is also important in DNA repair; cohesin functions in double-strand break repair by bringing homologous chromosomes together so one can be used as a template to repair the other(117–120). When DNA repair processes go awry, the result is often genomic instability. This hallmark of cancer can give rise to replication stress, aneuploidy, translocations and other aberrations that allow the disease to progress(127).

R-loops

R-loops are RNA-DNA hybrids that mainly form during transcription when the nascent transcript binds to the complement ssDNA template from which it was generated (128). These were initially thought to be rare events that had little impact on the biology of the cell but have recently been recognized as common structures that play a role in many biological processes (67). In the context of replication stress, these structures are thought to pose barriers to the processing replication fork by increasing the rate of transcription-replication collisions (66), but the exact mechanism is still unclear. Nonetheless, oncogene-induced DNA damage and replication fork slowing can be alleviated by RNaseH treatment or RNaseH1 overexpression, indicating that, not only does oncogenic activity increase the propensity for R-loops to form but the R-loops themselves induce genomic instability (63,129).

The EWS-FLI1-mediated increase in RNAPII phosphorylation and subsequent increase in transcription (mentioned above) also promotes the accumulation of R-loops (16). The overexpression of RNaseH1 decreased the sensitivity of a Ewing sarcoma cell line to ATR inhibition (16), suggesting that the presence of R-loops is contributing to the saturation of the RSR within these cells. This is not surprising as the main source of R-loop-mediated genomic instability has been proposed to be due to replication fork stalling (66,130). Interestingly, despite reducing the level of R-loops nearly 8-fold, RNaseH1 expression only minimally reversed the effects of ATRi treatment, implicating a more complex basis for ATRi sensitivity. Also, the level of DNA damage was not assessed upon RNaseH1 expression, so the role of R-loops in the promotion of genomic instability is unclear in this context. However, it is important to remember that R-loop formation does not always result in genomic instability. These structures have been shown to play important roles in several physiological processes including regulation of DNA methylation, recognition of promoter sequences by transcription factors, transcription termination and the DNA damage response (reviewed in (67).) Interestingly, however, a recent study investigating the transciptomic state that is permissible for EWS-FLI1 expression found that increased expression of enzymes involved in the resolution of R-loops and R-loop-associated replication stress are likely required for EWS-FLI1 expression in normal tissues (131). Specifically, this group found that members of the Fanconi Anemia pathway (involved in R-loop resolution (132)) FANCD1, FANCD2 and FANCA, are highly expressed in Ewing tumors and show increased activation (monoubiquitinated forms) in Ewing cell extracts. Furthermore, the genetic knockdown of FEN1 (also implicated in R-loop resolution (133,134)) results in cytotoxicity in Ewing cells, further emphasizing the necessity to resolve R-loop structures to maintain cell viability.

There is also evidence that suggests spliceosome instability may be contributing to the formation of R-loops in Ewing tumors. EWSR1 has been proposed to play a direct role in RNAPII-dependent co-transcriptional mRNA processing due to its ability to bind RNAPII and the presence of several RNA-binding domains in the C-terminal region. In support of this, a study published in 2011 showed that EWSR1 regulates the alternative splicing of several DNA damage response genes in response to UV radiation (13). Specifically, this group showed that, upon EWSR1 depletion, there are alternative splicing changes to genes involved in the DNA damage response, most notably CHEK2, ABL1 and MAP4K2. Although it is unclear as to whether this is a result of direct RNA binding or if EWSR1 plays an indirect role in modifying pre-mRNA transcripts, since EWSR1 has RNA-binding properties, it is likely that it is an active member of the messenger ribonucleoprotein (mRNP), in certain contexts. This is important because the formation of the mRNP, through the competent binding of splicing factors to nascent transcripts, prevents genomic instability, partially due to the passive suppression of R-loop formation that occurs upon RNA binding (135). Therefore, the EWS-FLI1-mediated disruption of EWSR1 has the potential to disrupt the stability of the spliceosome at a subset of loci (EWSR1 is likely to only be involved in the processing of specific mRNAs) and lead to the formation of R-loops, independent of an increase in RNAPII transcription. Therefore, while R-loops are known to play roles in the normal regulation of gene expression and cell fate (136), it is likely that their abberant formation in Ewing cells is detrimental and promoting genomic instability.

Clinically, this is relevant because there is potential to impair spliceosome stability further with use of small molecule inhibitors that disrupt U4 binding (137,138), resulting in lethal alterations to genomic stability and/or gene expression and cause cellular death. Mutations in the RNA-binding domains of EWSR1 have been found in a subset of familial forms of ALS(139). Therefore, this could also have implications into the understanding of the pathology of EWSR1 mutation-associated forms of ALS, as spliceosome instability could be contributing to motor neuron cell death.

ATR dependency

Being the main effector kinase of the RSR, ATR is an attractive target for anticancer therapeutics (140). Cancer cells with elevated levels of replication stress from activities of potent oncogenes such as RAS and MYC are known to be sensitive to ATR inhibitors (141) meaning that ATR inhibitor sensitivity could be an indicator of endogenous replication stress. Studies investigating the efficacy of ATR inhibitors for the treatment of Ewing sarcoma have demonstrated that, while combination treatment with gemcitabine and other traditional chemotherapeutic agents can effectively kill Ewing cells (142), ATR inhibitors also show potent activity as single agents (87). This is important because it shows that the endogenous source of replication stress is substantial enough to saturate the RSR to a point where minimal inhibition of ATR causes replicative catastrophe and cellular death. A preclinical study was conducted investigating the efficacy of the ATR inhibitor M6620 in combination with cisplatin or melphalan for the treatment of Ewing family of sarcoma (EFS) xenografts. Unfortunately, M6620 showed little single-agent activity and there were variable responses displayed when used in combination with cisplatin or melphalan (143).

PARP dependency

Prior to Ewing cells being recognized as deficient for BRCA1 function, they were shown to be sensitive to PARP1 inhibitors in preclinical studies (100,144). In fact, a large-scale unbiased drug screening of over 48,000 unique cell line-drug combinations was performed in 2012 and it identified EWS-FLI1-positive Ewing sarcoma as being “ultra-sensitive” to PARP1 inhibitors (105). The authors acknowledged this as one of the most notable relationships among the entire drug screen with a p-value of 1.03 × 10−26. The IC50 value for Olaparib was 4.7μM for EWS-FLI1 positive disease compared to 64μM for non-EWS-FLI1 cancer types (105). Several recent publications have shown that SLFN11 protein levels are positively correlated to tumor responses to PARP inhibitors and several other chemotherapeutic agents(145). Interestingly, SLFN11 is a direct transcriptional target of EWS-FLI1 and, as such, is highly overexpressed in Ewing sarcoma tumors (146). To this end, it has been shown that SLFN11 mediates toxicity to RNR inhibitors (147) as well as PARP inhibitors in combination with other chemotherapeutics, specifically temozolomide (146) suggesting that SLFN11 may play some role in mediating cell death under conditions that cause replication stress.

The growing preclinical evidence implicating EWS-FLI1 as a biomarker to predict PARPi sensitivity sparked the initiation of clinical trial in 2012. Ewing sarcoma patients with recurrent/metastatic disease who failed to respond to initial chemotherapy were given 400mg of Olaparib, twice daily, until disease progression was observed or drug intolerance was reached (148). Unfortunately, clinical responses were not met, and the clinical trial was terminated in 2014. A second clinical trial investigating the combination of the PARP1/2 inhibitor talazoparib and temozolomide for the treatment of recurrent Ewing sarcoma also found no antitumor activity and the trial was terminated in 2019 (149). It has been shown that PARP inhibitors as single agents or in combination with DNA damaging agents generate heterogenous clinical responses, even in patients with BRCA1/2 mutant tumors (150). The existence of intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms may be playing a large role in the failure of PARP inhibitors in the clinic. Importantly, the mechanism of action of many of the clinically relevant PARP inhibitors is PARP trapping and not necessarily the inhibition of PARP1 function. Studies aimed at elucidating exactly how PARP1 activity is promoting/allowing oncogenesis in particular tumors may reveal rational combination therapies that can overcome these resistance mechanisms; for example, strategies that do not rely on PARP trapping but rather the inhibition of PARP1 function.

Despite the failure of single agent Olaparib in clinical trials, Ewing sarcoma tumor sensitivity to PARP inhibitors is still potentially very important in the context of understanding the replication stress response in these tumors. PARP1 has been shown to localize to the sites of stalled replication forks and its activity increases upon hydroxyurea (HU) treatment (151). PARP1 also has roles in the slowing of replication rates on damaged DNA and to promote the initiation of HR-mediated fork restart (152). Sugimura et al. showed that PARP1 inhibition sensitizes cells to the replication-dependent DNA damaging agent CPT, suggesting a role for PARP1 in the repair of replication-dependent damage. At stalled forks, its activity is implicated in the repair and resolution of DNA single strand breaks (SSBs) (153). Without PARP1 activity, SSBs persist and can be converted into DSBs during replication. As mentioned above, replication stress results in the formation of long stretches of ssDNA between the progressing helicase and the DNA polymerase, and these strands are vulnerable to cleavage by endonucleases such as MUS81 and MRE11, and can become SSBs (151,154). Without PARP1 activity, these SSBs may not be resolved in a timely manner. Upon fork restart, when the polymerase attempts to replicate past these SSBs, it falls off due to the absence of a template, creating a toxic DSB. Cancer cells that have increased fork stalling will have an increased requirement for PARP activity and are expected to be sensitive to PARP loss. This may be contributing to Ewing sarcoma cells sensitivity to PARPi. If this is the case, it may be efficacious to combine PARP1 inhibitors with inhibitors of ATR, WEE1 or CHK1 for the treatment of Ewing tumors, as the PARP1 inhibition would place increased stress on the RSR kinases. There is promising preclinical evidence that suggests combining PARP inhibitors with inhibitors of ATR or WEE1 can be an efficacious treatment strategy, especially in BRCA-deficient tumors (155–157). We expect that Ewing sarcoma tumors would also be sensitive to this combination.

This idea was recently validated by a promising study conducted in 2018 that showed the PARP1 inhibitor Olaparib and the CDK12 inhibitor THZ531 synergistically kill Ewing sarcoma cells in in vitro and in vivo preclinical models (158). CDK12 is a transcription-associated CDK that is required for the phosphorylation of RNAPII and is involved in the proper expression of several DDR genes including ATR and BRCA1 and BRCA2 (159). In Ewing cell lines, PARP1 inhibition resulted in a dramatic increase in HR-mediated repair (Rad51 foci) that was abolished by CDK12 inhibition suggesting a role for PARP1 in the suppression of S-phase-associated damage (HR-mediated repair is mainly restricted to late S and G2 (160)).

The CHK1 paradox

The CHK1 kinase is the main effector kinase within the RSR that works downstream of ATR. Interestingly, there are reports of ATR-independent mechanisms of CHK1 activation (161), suggesting a more complex regulatory network. Recent studies focused on the efficacy of targeting CHK1 for the treatment of Ewing sarcoma have generated some thought-provoking results.

Ewing sarcoma xenografts showed increased sensitivity to the CHK1 inhibitor Prexasertib (Prex) as a single agent and chemopotentiator compared to several other xenografts derived from other pediatric soft tissue cancers (162). This result was interesting because other groups have shown that Ewing sarcoma cells have increased CHK1 kinase levels (87) and show limited response to enzyme inhibition/depletion (163). However, decreasing CHK1 protein levels with either RNAi or inhibition of protein synthesis with an inhibitor to mTORC1/2 (TAK-228) conferred sensitivity to CHK1 inhibitors (163). This was a puzzling find. It is possible that the levels of CHK1 are too high in Ewing sarcoma cells to effectively inhibit the enzyme with biologically relevant concentrations of inhibitors. However, by depleting the cell of CHK1 protein, practical concentrations of CHK1 inhibitors can be used to inhibit enough enzyme and elicit a response. The question then becomes: why does Prex show efficacy as a single agent? Oddly enough, Prex treatment negatively impacted CHK1 protein levels while also exerting inhibitory effects on the enzyme itself (162,163); further owing to the hypothesis that high CHK1 protein levels confer innate resistance to CHK1 inhibitors in Ewing sarcoma tumors and depletion of CHK1 can eliminate this resistance. However, this is in direct contrast with the idea that the RSR is saturated in cancers that exhibit high levels of replication stress. If enzyme depletion is required to elicit the anti-tumor effects of CHK1 inhibitors, then it would seem that there is either an abundance of inactive CHK1 enzyme that is readily available to quench small molecule inhibitors, or the majority of the CHK1 function that is being inhibited is not essential for cell survival. To this end, concurrent treatment with either irinotecan or cyclophosphamide and Prex prevented innate resistance to chemotherapy in Ewing sarcoma cells, suggesting a role for CHK1 function in resistance to chemotherapy (162). Furthermore, the CHK1 inhibitor LY2603618 or CHK1 siRNA was able to sensitize Ewing cells to the RRM2 inhibitor Gemcitabine (142). It is possible that there are high levels of “dormant” CHK1 within Ewing cells that are able to become active when the cell is challenged with a genotoxic agent, preventing replication catastrophe and cell death. Therefore, administering genotoxic agents while simultaneously inhibiting the excess CHK1 eliminates the potential for CHK1-mediated resistance.

Combination treatment with CHK1 inhibitors and other chemotherapeutic agents have shown efficacy in several forms of cancer (164,165). The use of subclinical doses of hydroxyurea in combination with inhibitors of CHK1 has been shown to effectively control the progression of melanoma and lung cancer with significantly less toxicities than gemcitabine alone (165). In gastric cancer, the inhibition of CHK1 is effective at potentiating the antitumor effect of the PARP1 inhibitor BMN673 (164). There is some promising evidence that CHK1 inhibitors, in combination with other chemotherapies, may be an efficacious strategy in Ewing tumors (142,162), but this is still an understudied area.

WEE1 dependency

While CHK1 kinase levels are known to be elevated in Ewing sarcoma cells (87), WEE1 kinase levels are significantly lower in Ewing sarcoma cells compared to other cell lines, suggesting either under expression of the gene or reduced stability of the protein (162). Again, the notion that elevated levels of RSR proteins could indicate an elevated level of replication stress does not seem to hold true here. However, WEE1 kinase is likely to play a larger role in the prevention of replication stress by inhibiting CDK2 activity and a smaller role in the RSR itself. Therefore, elevated levels of WEE1 would not necessarily be an expected consequence of elevated levels of replication stress. Several studies have highlighted the separation of WEE1 function from the rest of the ATR-mediated RSR. Young et al. showed that, when given inhibitors for ATR or WEE1, non-germinal center B-cell (GCB) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells displayed very different phenotypes (166). Cells treated with ATR inhibitors acquired large amounts of DNA damage and displayed 53BP1 foci mainly in G1 while cells treated with WEE1 inhibitors accumulated some DNA damage but were arrested in S-phase (166). When challenged with an inhibitor of WEE1, Ewing sarcoma cells showed signs of apoptosis and increased CDK2 activity. However, in contrast to previous reports, Ewing cells displayed mitotic entry when treated with a WEE1 inhibitor instead of an S-phase arrest(167). This was independent of TP53 status, as cell lines of both WT and mutant p53 had similar outcomes. However, this phenotype was not specific to Ewing sarcoma as cell lines of other sarcoma types, including osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma and liposarcoma, displayed similar phenotypes.

WEE1 inhibition is known to cause nucleotide depletion. This is likely due to the increase in CDK2 activity, reduction in RRM2 expression, and an increase in origin firing upon loss of WEE1 activity (65). A recent report showed that ATR, CHK1 or WEE1 inhibition resulted in an increase in CDK2 activity and subsequent reduction in RRM2 protein levels (168). This reduction in RRM2 resulted in nucleotide depletion, DNA damage and apoptosis in Ewing sarcoma cells. Others have shown that direct inhibition of RRM2 with Gemcitabine or Hydroxyurea results in DNA damage and apoptosis in Ewing cells (147) and that inhibition of CHK1 sensitizes the cells to these agents (142) consistent with an increased level of replication stress. Together, these reports strongly suggest that Ewing sarcoma cells are very sensitive to minimal nucleotide depletion and rely on consistent levels of dNTPs to maintain proper replication rates and homeostasis. It would, therefore, be plausible to combine an inhibitor of WEE1 with an inhibitor of ATR or CHK1 as the WEE1 inhibitor would result in a CDK2-dependent increase in replication and depletion of nucleotides and subsequent replication stress and ATR activation.

R-loop-mediated fork stalling and disruption of histone recycling

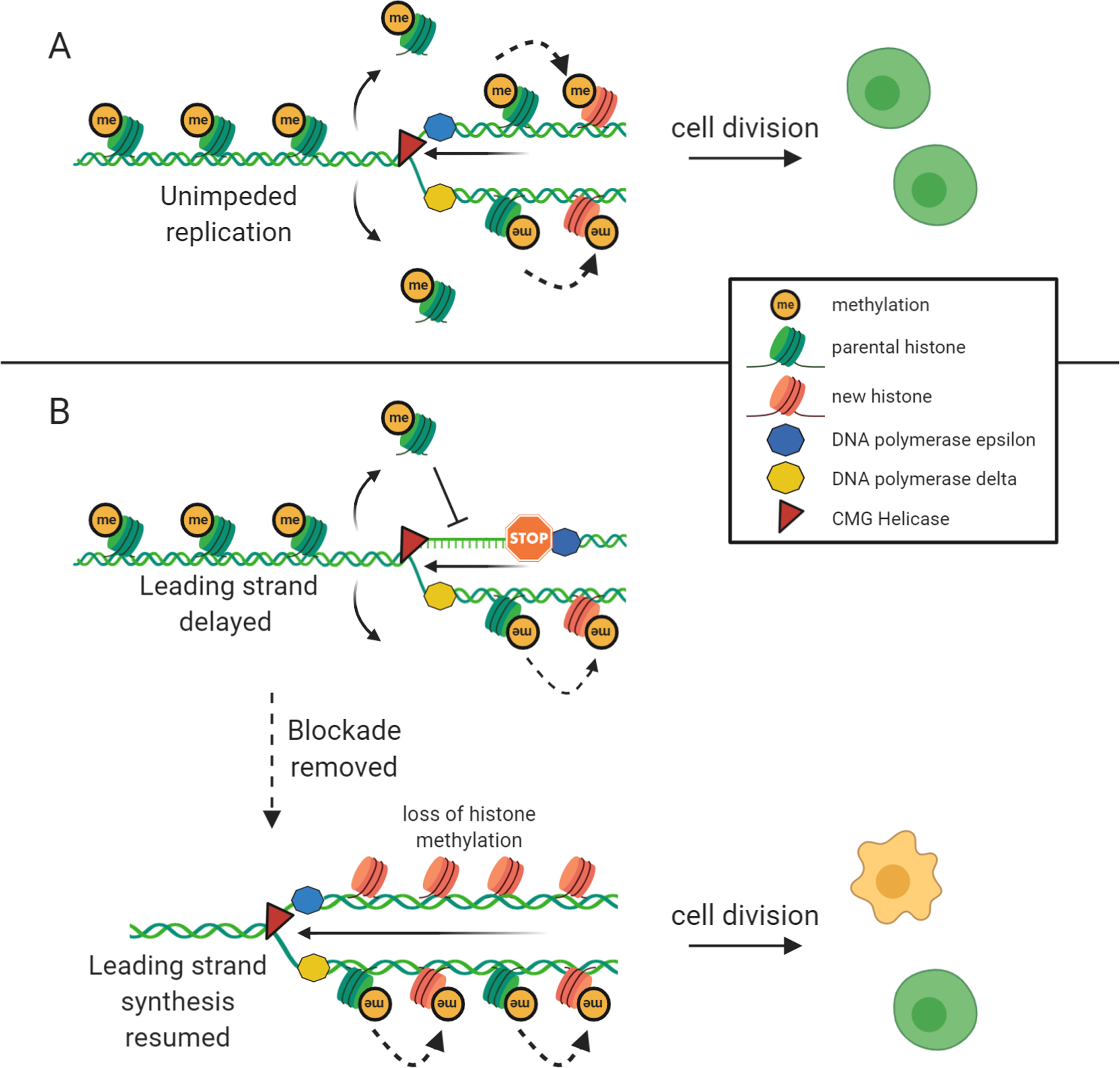

While epigenetic instability can give rise to replication stress, the reverse is also true. Recently, there has been much focus on the effects of replication fork delays on the maintenance of histone post-translational modifications through cell division. The main mechanism that allows epigenetic information that is carried on histones to be transmitted to daughter cells through cell division is histone recycling. Histone recycling refers to the deposition of parental histones, with epigenetic information intact, onto the daughter DNA strands immediately following synthesis(169). This process is heavily reliant on histone chaperones such as FACT(170) and ASF1(171) and is closely tied to the actions of the replisome. Impediments to replication fork results in the inhibition of histone recycling and can result in modifications to the pre-existing epigenetic information, typically the loss of histone marks (172) (fig. 3). This has obvious consequences including changes in gene expression and alterations in the topological organization of the surrounding chromatin. Depending on the context, epigenetic changes can have profound impacts on cellular function and can even lead to oncogenesis (reviewed in (173)).

Figure 3. Histone recycling and replication stress.

Histone recycling takes place during replication and is one of the main mechanisms that allow for epigenetic information that is carried on histones to be inherited by daughter cells upon cell division. A) Parental histones are removed ahead of the progressing replication fork and are immediately deposited into the newly synthesized strands of DNA. These are accompanied by new histones that are initially devoid of any post translational modifications. The methylation pattern of the parental histones is recognized and copied to new histones in a process that still remains somewhat elusive. This allows for the inheritance of epigenetic information to daughter cells and proper recapitulation of gene expression and cellular function after cell division. B) If polymerase progression is impeded by replication blockades the process of histone removal and deposition into newly synthesized DNA is decoupled. This inhibits the histone recycling process. Once the blockade is removed and replication continues, the parental histones that were removed ahead of the fork are no longer in a position to be placed into the new DNA strand. This results in the placement of long stretches of new histones that are devoid of post-translational modifications and loss of the pre-existing epigenetic information. This has the potential to dramatically alter gene expression and cellular function.

R-loop mediated transcription-replication collisions are a well-characterized source of fork stalling in Ewing tumors (16). Importantly, R-loops tend to form in RNA Pol II transcribed regions, typically at gene ends where epigenetic stability is of paramount importance (67,174). It is very possible that R-loop mediated fork stalling can influence epigenetic changes in gene promoters and affect gene expression in Ewing cells due to the uncoupling of histone recycling. We hypothesize that replication fork stalling in these areas that lead to epigenetic alterations could play a significant role in the etiology of this disease. This is an area that has not been investigated to date.

Conclusions

Ewing sarcoma is an aggressive and deadly childhood cancer. Patients that present with recurrent and/or metastatic disease have a poor outcome, and even for survivors, treatment-associated toxicities and secondary diseases are prevalent. There have been little changes to the standard of care over the last few decades, creating a significant need for the development of novel, less toxic therapies. Here we present evidence that Ewing cells harbor a plethora of unique defects that ultimately lead to an increase in replication stress. There is much potential to exploit these vulnerabilities and create novel therapeutic strategies.

While the dramatic increase in transcription rate is likely a major source of stress(16), this alone is unlikely to fully explain the degree of defect observed in these cells. For example, the EWS-FLI1 translocation results in the production of a fusion protein known to function as an aberrant transcription factor, and partially mimic the effects of c-Myc and/or Ras mutations, but a less studied aspect of this is the decrease in WT EWSR1 protein expression, which may also be contributing significantly to the increased replication stress seen in these cells. Also, it is likely that as a result of an increase in R-loop formation, there is also an increase in dormant origin usage, and an increased requirement for HR-mediated repair; these may all be contributing to genomic instability and replication stress.

Normally, cells combat increased replication stress by activating pathways responsible for the suppression and repair of replication stress. In Ewing sarcoma, cells are unable to successfully activate a sufficient replication stress response (RSR) and compensate for these defects. Mutations in these regulatory elements are exceedingly rare across all cancer subtypes, and there is no current evidence of mutations being present within Ewing tumors. Instead, what we believe we observe in Ewing sarcoma is a saturation of these pathways. However, a slightly paradoxical reality is that Ewing sarcoma tumors are relatively void of somatic mutations and other genomic rearrangements (24). Compared to adult tumors, pediatric tumors tend to have more stable genomes and lack the accumulation of somatic mutations in major oncogenic and tumor suppressive pathways. We believe this is due to two main factors. First, we expect pediatric tumors to have a significantly lower burden of environmentally derived passenger mutations. Adult tumors, at least in part, tend to have large mutational loads due to the acquisition of mutations throughout the course of the patient’s lifetime. Second, we have hypothesized that Ewing tumors are equipped with an increased capacity to protect the genome from mutational acquisition despite a large level of DNA breaks, perhaps through the upregulation of DNA repair enzymes. We have unpublished, preliminary data that supports this hypothesis. However, several studies have suggested that, not only do Ewing tumors not have an increased level of repair enzymes, they are actually deficient in them (158,175). Additional research is needed to resolve this conflict.

In conclusion, we believe that the development of creative drug combinations and novel therapeutics exploiting unique defects in Ewing sarcoma replication stress are a promising approach for future clinical interventions. Additional research is needed to parse these results at a molecular level and direct targeted therapies to distinct pathways such as ATR, ATM, CHK1 etc. We hope that this consolidation sparks investigations that lead to these discoveries.

Implications:

This review uncovers new therapeutic targets in Ewing Sarcoma and highlights replication stress as an exploitable vulnerability across multiple cancers.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Roswell Park Alliance Foundation to J.E.O. No grant number assigned.

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cronin KA, Lake AJ, Scott S, Sherman RL, Noone AM, Howlader N, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, part I: National cancer statistics. Cancer 2018;124(13):2785–800 doi 10.1002/cncr.31551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grünewald TGP, Cidre-Aranaz F, Surdez D, Tomazou EM, de Álava E, Kovar H, et al. Ewing sarcoma. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2018;4(1):5 doi 10.1038/s41572-018-0003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaspar N, Hawkins DS, Dirksen U, Lewis IJ, Ferrari S, Le Deley MC, et al. Ewing Sarcoma: Current Management and Future Approaches Through Collaboration. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2015;33(27):3036–46 doi 10.1200/jco.2014.59.5256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horowitz M, Delaney T, Malawer M, Woo S, Hicks M. Ewing’s sarcoma of bone and soft tissue and peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor Principles and practice of pediatric oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan AY, Manley JL. The TET Family of Proteins: Functions and Roles in Disease. J Mol Cell Biol 2009;1(2):82–92 doi 10.1093/jmcb/mjp025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson S, Perrin V, Guillemot D, Reynaud S, Coindre JM, Karanian M, et al. Transcriptomic definition of molecular subgroups of small round cell sarcomas. The Journal of pathology 2018;245(1):29–40 doi 10.1002/path.5053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mackintosh C, Madoz-Gurpide J, Ordonez JL, Osuna D, Herrero-Martin D. The molecular pathogenesis of Ewing’s sarcoma. Cancer biology & therapy 2010;9(9):655–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertolotti A, Melot T, Acker J, Vigneron M, Delattre O, Tora L. EWS, but Not EWS-FLI-1, Is Associated with Both TFIID and RNA Polymerase II: Interactions between Two Members of the TET Family, EWS and hTAFII68, and Subunits of TFIID and RNA Polymerase II Complexes. Mol Cell Biol 1998;18(3):1489–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertolotti A, Lutz Y, Heard DJ, Chambon P, Tora L. hTAF(II)68, a novel RNA/ssDNA-binding protein with homology to the pro-oncoproteins TLS/FUS and EWS is associated with both TFIID and RNA polymerase II. EMBO J 1996;15(18):5022–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahama K, Sugimoto C, Arai S, Kurokawa R, Oyoshi T. Loop lengths of G-quadruplex structures affect the G-quadruplex DNA binding selectivity of the RGG motif in Ewing’s sarcoma. Biochemistry 2011;50(23):5369–78 doi 10.1021/bi2003857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahama K, Kino K, Arai S, Kurokawa R, Oyoshi T. Identification of RNA binding specificity for the TET-family proteins. Nucleic acids symposium series (2004) 2008(52):213–4 doi 10.1093/nass/nrn108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohno T, Ouchida M, Lee L, Gatalica Z, Rao VN, Reddy ES. The EWS gene, involved in Ewing family of tumors, malignant melanoma of soft parts and desmoplastic small round cell tumors, codes for an RNA binding protein with novel regulatory domains. Oncogene 1994;9(10):3087–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paronetto MP, Miñana B, Valcárcel J. The Ewing sarcoma protein regulates DNA damage-induced alternative splicing. Mol Cell 2011;43(3):353–68 doi 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimizu R, Tanaka M, Tsutsumi S, Aburatani H, Yamazaki Y, Homme M, et al. EWS-FLI1 regulates a transcriptional program in cooperation with Foxq1 in mouse Ewing sarcoma. Cancer science 2018;109(9):2907–18 doi 10.1111/cas.13710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.May WA, Lessnick SL, Braun BS, Klemsz M, Lewis BC, Lunsford LB, et al. The Ewing’s sarcoma EWS/FLI-1 fusion gene encodes a more potent transcriptional activator and is a more powerful transforming gene than FLI-1. Mol Cell Biol 1993;13(12):7393–8 doi 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorthi A, Romero JC, Loranc E, Cao L, Lawrence LA, Goodale E, et al. EWS-FLI1 increases transcription to cause R-loops and block BRCA1 repair in Ewing sarcoma. Nature 2018;555(7696):387–91 doi 10.1038/nature25748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chansky HA, Barahmand-Pour F, Mei Q, Kahn-Farooqi W, Zielinska-Kwiatkowska A, Blackburn M, et al. Targeting of EWS/FLI-1 by RNA interference attenuates the tumor phenotype of Ewing’s sarcoma cells in vitro. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society 2004;22(4):910–7 doi 10.1016/j.orthres.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takigami I, Ohno T, Kitade Y, Hara A, Nagano A, Kawai G, et al. Synthetic siRNA targeting the breakpoint of EWS/Fli-1 inhibits growth of Ewing sarcoma xenografts in a mouse model. Int J Cancer 2011;128(1):216–26 doi 10.1002/ijc.25564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu H, Ge Y, Guo L, Huang L. Potential approaches to the treatment of Ewing’s sarcoma. Oncotarget 2017;8(3):5523–39 doi 10.18632/oncotarget.12566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uren A, Toretsky JA. Ewing’s sarcoma oncoprotein EWS-FLI1: the perfect target without a therapeutic agent. Future oncology (London, England) 2005;1(4):521–8 doi 10.2217/14796694.1.4.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato M, Han TW, Xie S, Shi K, Du X, Wu LC, et al. Cell-free formation of RNA granules: low complexity sequence domains form dynamic fibers within hydrogels. Cell 2012;149(4):753–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uren A, Tcherkasskaya O, Toretsky JA. Recombinant EWS-FLI1 oncoprotein activates transcription. Biochemistry 2004;43(42):13579–89 doi 10.1021/bi048776q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tirode F, Surdez D, Ma X, Parker M, Le Deley MC, Bahrami A, et al. Genomic landscape of Ewing sarcoma defines an aggressive subtype with co-association of STAG2 and TP53 mutations. Cancer discovery 2014;4(11):1342–53 doi 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crompton BD, Stewart C, Taylor-Weiner A, Alexe G, Kurek KC, Calicchio ML, et al. The genomic landscape of pediatric Ewing sarcoma. Cancer discovery 2014;4(11):1326–41 doi 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-13-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brohl AS, Solomon DA, Chang W, Wang J, Song Y, Sindiri S, et al. The genomic landscape of the Ewing Sarcoma family of tumors reveals recurrent STAG2 mutation. PLoS genetics 2014;10(7):e1004475 doi 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tirode F, Surdez D, Ma X, Parker M, Le Deley MC, Bahrami A, et al. Genomic landscape of Ewing sarcoma defines an aggressive subtype with co-association of STAG2 and TP53 mutations. Cancer discovery 2014;4(11):1342–53 doi 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toomey EC, Schiffman JD, Lessnick SL. Recent advances in the molecular pathogenesis of Ewing’s sarcoma. Oncogene 2010;29(32):4504–16 doi 10.1038/onc.2010.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawlor ER, Sorensen PH. Twenty Years On – What Do We Really Know About Ewing Sarcoma And What Is The Path Forward? Crit Rev Oncog 2015;20(0):155–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ginsberg JP, Goodman P, Leisenring W, Ness KK, Meyers PA, Wolden SL, et al. Long-term survivors of childhood Ewing sarcoma: report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2010;102(16):1272–83 doi 10.1093/jnci/djq278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paulussen M, Ahrens S, Lehnert M, Taeger D, Hense HW, Wagner A, et al. Second malignancies after ewing tumor treatment in 690 patients from a cooperative German/Austrian/Dutch study. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 2001;12(11):1619–30 doi 10.1023/a:1013148730966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longhi A, Ferrari S, Tamburini A, Luksch R, Fagioli F, Bacci G, et al. Late effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy in osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma patients: the Italian Sarcoma Group Experience (1983–2006). Cancer 2012;118(20):5050–9 doi 10.1002/cncr.27493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kotsantis P, Petermann E, Boulton SJ. Mechanisms of Oncogene-Induced Replication Stress: Jigsaw Falling into Place. Cancer discovery 2018;8(5):537–55 doi 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-17-1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeman MK, Cimprich KA. Causes and Consequences of Replication Stress. Nature cell biology 2014;16(1):2–9 doi 10.1038/ncb2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilhelm T, Olziersky A-M, Harry D, De Sousa F, Vassal H, Eskat A, et al. Mild replication stress causes chromosome mis-segregation via premature centriole disengagement. Nature communications 2019;10(1):3585– doi 10.1038/s41467-019-11584-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gelot C, Magdalou I, Lopez BS. Replication stress in Mammalian cells and its consequences for mitosis. Genes 2015;6(2):267–98 doi 10.3390/genes6020267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Técher H, Koundrioukoff S, Nicolas A, Debatisse M. The impact of replication stress on replication dynamics and DNA damage in vertebrate cells. Nature Reviews Genetics 2017;18:535 doi 10.1038/nrg.2017.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mazouzi A, Velimezi G, Loizou JI. DNA replication stress: Causes, resolution and disease. Experimental Cell Research 2014;329(1):85–93 doi 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forment JV, O’Connor MJ. Targeting the replication stress response in cancer. Pharmacology & therapeutics 2018;188:155–67 doi 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelly T, Callegari AJ. Dynamics of DNA replication in a eukaryotic cell. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019;116(11):4973–82 doi 10.1073/pnas.1818680116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lim S, Kaldis P. Cdks, cyclins and CKIs: roles beyond cell cycle regulation. Development (Cambridge, England) 2013;140(15):3079–93 doi 10.1242/dev.091744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm. Nature reviews Cancer 2009;9(3):153–66 doi 10.1038/nrc2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishitani H, Lygerou Z. DNA replication licensing. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library 2004;9:2115–32 doi 10.2741/1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blow JJ, Gillespie PJ. Replication licensing and cancer--a fatal entanglement? Nature reviews Cancer 2008;8(10):799–806 doi 10.1038/nrc2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blow JJ, Hodgson B. Replication licensing--defining the proliferative state? Trends in cell biology 2002;12(2):72–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Warner MD, Azmi IF, Kang S, Zhao Y, Bell SP. Replication origin-flanking roadblocks reveal origin-licensing dynamics and altered sequence dependence. J Biol Chem 2017;292(52):21417–30 doi 10.1074/jbc.M117.815639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Labib K How do Cdc7 and cyclin-dependent kinases trigger the initiation of chromosome replication in eukaryotic cells? Genes Dev 2010;24(12):1208–19 doi 10.1101/gad.1933010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bochman ML, Schwacha A. The Mcm Complex: Unwinding the Mechanism of a Replicative Helicase. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2009;73(4):652–83 doi 10.1128/mmbr.00019-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Remus D, Diffley JF. Eukaryotic DNA replication control: lock and load, then fire. Current opinion in cell biology 2009;21(6):771–7 doi 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]