Abstract

In fragile X syndrome (FXS) the lack of the fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) leads to exacerbated signaling through the metabotropic glutamate receptors 5 (mGlu5Rs). The adenosine A2A receptors (A2ARs), modulators of neuronal damage, could play a role in FXS. A synaptic colocalization and a strong permissive interaction between A2A and mGlu5 receptors in the hippocampus have been previously reported, suggesting that blocking A2ARs might normalize the mGlu5R-mediated effects of FXS. To study the cross-talk between A2A and mGlu5 receptors in the absence of FMRP, we performed extracellular electrophysiology experiments in hippocampal slices of Fmr1 KO mouse. The depression of field excitatory postsynaptic potential (fEPSPs) slope induced by the mGlu5R agonist CHPG was completely blocked by the A2AR antagonist ZM241385 and strongly potentiated by the A2AR agonist CGS21680, suggesting that the functional synergistic coupling between the two receptors could be increased in FXS. To verify if chronic A2AR blockade could reverse the FXS phenotypes, we treated the Fmr1 KO mice with istradefylline, an A2AR antagonist. We found that hippocampal DHPG-induced long-term depression (LTD), which is abnormally increased in FXS mice, was restored to the WT level. Furthermore, istradefylline corrected aberrant dendritic spine density, specific behavioral alterations, and overactive mTOR, TrkB, and STEP signaling in Fmr1 KO mice. Finally, we identified A2AR mRNA as a target of FMRP. Our results show that the pharmacological blockade of A2ARs partially restores some of the phenotypes of Fmr1 KO mice, both by reducing mGlu5R functioning and by acting on other A2AR-related downstream targets.

Subject terms: Molecular neuroscience, Hippocampus

Introduction

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is characterized by a complex clinical phenotype and symptoms that include hyperactivity, autism, attention disorders, and seizures1–6. The disease is caused by an expansion of CGG-repeats in the fragile X mental retardation 1 gene (FMR1) that encodes fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP). As a result, the expression of the gene is impaired, and either partial or complete silencing of FMRP occurs7. FMRP is an RNA-binding protein8 that regulates different steps of mRNA metabolism9–14 and binds only a fraction of mRNAs expressed in the brain15. A primary role of FMRP in the brain is the control of synaptic plasticity by regulating mRNA metabolism and repressing protein synthesis in dendrites and synapses12,13,16,17, and thereby its lack results in excessive protein synthesis18. How FMRP impairment causes FXS is not yet fully understood but some mechanisms are considered particularly relevant. First of all, it has been proposed that over-activation of metabotropic glutamate 5 receptor (mGlu5R)-mediated signaling plays a causal role in FXS19. This “mGluR theory” was strongly supported by the finding that genetic reduction of mGlu5R expression is sufficient to correct a broad range of phenotypes in the Fmr1 KO mouse, a murine model useful for the study of FXS20. Additionally, pharmacological studies have shown that short-acting mGlu5R inhibitors, such as MPEP and Fenobam, can ameliorate FXS phenotypes in several evolutionarily distant animal models21. Moreover, Michalon and colleagues22 showed that the potent and selective mGlu5R inhibitor CTEP can correct phenotype abnormalities in young adult Fmr1 KO mice, after the development of the phenotype. Finally, clinical studies suggested possible effects of the mGlu5R antagonist AFQ056 only on a subset of FXS patients23. Despite all these promising studies, in clinical trials no clear therapeutic benefit has been confirmed in heterogeneous populations of FXS patients treated with different mGlu5R inhibitors24,25. Although the reasons for the lack of translation from the preclinical to the clinical setting are largely unknown, the broad age range (12–40 years) of FXS individuals in clinical trials might have prevented the detection of a therapeutic benefit, which is more likely in young children, with an ongoing neurodevelopment26. Consistently, a new NIH-funded clinical trial in which the effects of AFQ056 will be specifically evaluated on language learning in young children (32 months to 6 years) with FXS is on progress (https://www.fraxa.org/fx-learn-clinical-trial-is-enrolling-children-with-fragile-x/).

Furthermore, a factor which has been relatively neglected in preclinical and clinical studies to date is the development of tolerance to mGlu5R inhibitors, already observed for the mGlu5R antagonist MPEP after repeated administration at high doses in Fmr1 KO mice27.

This is currently an object of investigation (https://www.fraxa.org/pharmacological-tolerance-in-the-treatment-of-fragile-x-syndrome/).

Adenosine is a naturally occurring purine nucleoside distributed ubiquitously throughout the body that acts through multiple G protein-coupled adenosine receptor subtypes28,29. The adenosine A2A receptors (A2ARs), which play a major role in the brain, are effective modulators of neuronal damage in various pathological situations, and both their activation and blockade can be neuroprotective in different experimental conditions30–33. Although A2ARs are most abundant in the striatum, they are also present in the hippocampus, a brain region strongly affected in FXS, where they finely modulate synaptic transmission and excitotoxicity34.

We hypothesized that A2ARs could have relevance in FXS since these receptors exert a strong permissive role on mGlu5R-mediated effects in different brain areas35,36, and could contribute to direct or indirect modulation of different signaling pathways overactive in FXS37–42.

In this study, we first assessed whether the functional A2A/mGlu5 receptors interaction was altered in Fmr1 KO mice; then, we evaluated if pharmacological blockade of A2ARs was beneficial in terms of synaptic functions, neurobehavioral phenotype, and signaling features in Fmr1 KO mice. Finally, we explored the A2AR mRNA/FMRP interaction in the mouse brain. Our findings indicate that A2ARs play a role in FXS and that A2AR antagonist can modulate mGlu5R synaptic signaling and ameliorate behavioral phenotypes in FXS mice.

Materials and methods

Methods are described briefly below; see Supplementary information for detailed descriptions.

Animals

All procedures were carried out according to the principles outlined in the European Communities Council Directive, 2010/63/EU, DL 26/2014, FELASA, and ARRIVE guidelines, and approved by the Italian Ministry of Health and by the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). The experiments were performed on male and female C57Bl/6 wild-type (WT) and C57Bl/6 Fmr1 knock-out (KO) mice between 10 and 18 weeks of age; FMRP immunoprecipitation was performed on male FVB.129P2 WT and Fmr1 KO mice at 3 and 4 weeks of age. A colony of C57Bl/6 Fmr1 KO mice43 was established starting from breeding pairs of animals (Charles River). Sample sizes were chosen according to information obtained from pilot studies or published data22. No randomization was performed to allocate subjects in the study. However, we allocated arbitrarily the animals to different experimental groups. No blinding was performed except for dendritic spine evaluation.

Drugs and treatment

CHPG [(RS)-2-Chloro-5-hydroxyphenylglycine sodium salt], ZM241385 [4-(2-[7-Amino-2-(2-furyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[2,3-a][1,3,5]triazin-5-ylamino]ethyl)phenol], DHPG [(RS)-3,5-Dihydroxyphenylglycine], and CGS21680 [4-[2-[[6-Amino-9-(N-ethyl-β-D-ribofuranuronamidosyl)-9H-purin-2-yl]amino]ethyl]benzenepropanoic acid hydrochloride] (Tocris Biosciences) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Istradefylline [8-[(1E)-2-(2-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)ethenyl]-1,3-diethyl-3,7-dihydro-7-methyl-1H-purine-2,6-dione] (Tocris Biosciences, hereinafter referred to as KW6002) was orally administered solubilized in the vehicle prepared according to Orr et al.44. The weight of the animals and the fluid intake were assessed three times a week, and the concentration of the solution was adjusted so that the drug intake was maintained at 4 mg/kg per day44.

Electrophysiology experiments

Hippocampal slice preparation and recordings were performed as previously described39. Extracellular field excitatory postsynaptic potential (fEPSPs) were recorded in stratum radiatum of the CA1 upon stimulation of Schaffer collaterals, then acquired and analyzed with the LTP program45. One slice was tested per experiment. Slices were obtained from at least two animals for each set of the experiment. mGluR-dependent long-term depression (LTD) was obtained by applying to hippocampal slices the group 1-mGluR agonist DHPG, 100 μM for 5 min46. Maximal transient depression (MTD) for a slice was defined as the time point post-DHPG application with the greatest depression within each slice. The DHPG-induced LTD was expressed as the mean percentage variation of the slope 60 min after treatment.

Spine number and morphological analyses

These experiments were performed on rapid Golgi-Cox-stained brain sections47. At the end of the chronic treatment with vehicle or KW6002, mice were deeply anesthetized and perfused transcardially with 0.9% saline solution (n = 3 animals per group). Brains were picked up and immediately immersed into a Golgi-Cox solution at RT for 6 nights. On the seventh day, brains were transferred in a 30% sucrose solution for cryoprotection and then sectioned with a vibratome. Coronal sections (100 μm) were collected and stained. Spine density was analyzed on hippocampal CA1 stratum pyramidale neurons. On each neuron, five 30–100 μm dendritic segments of secondary and tertiary branch order of CA1 dendrites were randomly selected48 and counted using Neurolucida software.

Testis weight

Macroorchidism in male mice postnatal days (PND) 130 (18 weeks of age, immediately after 12 weeks of the vehicle or drug treatment) was assessed as previously described22.

Behavioral evaluation

All behavioral tests were performed between 7:30 a.m. and 13:00 a.m. and after mice were acclimated to the behavioral testing room for at least 30 min. The following experimental groups were compared: WT VEH mice (n = 11; 6 males and 5 females), Fmr1 KO VEH mice (n = 16; 8 males and 8 females), and Fmr1 KO KW mice (n = 22; 12 males and 10 females). Open field, Novel object recognition (NOR), Marble-burying, and Rotarod tests were performed as previously described49–52.

Protein extraction and western blot analysis

Hippocampal and cortical mouse tissue samples were homogenized in RIPA Buffer on ice, centrifuged at 12,000g for 20 min at 4 °C, and supernatants were stored at −80 °C. Equal amounts of proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE gel and transferred on a PVDF membrane (Biorad Laboratories). After blocking, membranes were incubated with specific antibodies (anti-Phospho-Erk1/2, anti-Erk1/2, anti-Phospho-mTOR, anti-mTOR, anti-TrkB, anti-BDNF, anti-β-actin) and consequently treated as detailed in the supplements.

STEP activity/expression analysis

Crude synaptosomal fraction preparation and STEP activity evaluation were performed as previously described (Chiodi et al.40 and references therein). For the western blot analysis of STEP, samples (40 μg of proteins) were analyzed according to Mallozzi et al.53.

FMRP immunoprecipitation

Brain extracts were prepared from cortex and hippocampus or striatum of WT and Fmr1 KO male mice 3–4 weeks old, using RIPA buffer plus Protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), Phosphatase inhibitor cocktails II and III (Sigma), 40 U/ml RNaseOUT (Invitrogen). Protein extracts were used for RNA-immunoprecipitation (RIP) using a specific anti-FMRP antibody54.

Saturation binding experiments

Saturation binding experiments were carried out on homogenized striatum, cortex, and hippocampus from WT and Fmr1 KO mice (2–3 months of age), by using the A2AR antagonist [3H]-ZM241385 as radioligand.

Statistics

Results from experiments were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). For details, see the description in results, legends, and supplements. Statistical analysis was performed by using Mann-Whitney test or Student’s t-test, and p-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference. All statistical analyses and electrophysiology curve fittings were performed by using GraphPad Prism software (USA).

Results

A2AR differently modulates the hippocampal mGlu5R-induced synaptic effects in Fmr1 KO mice

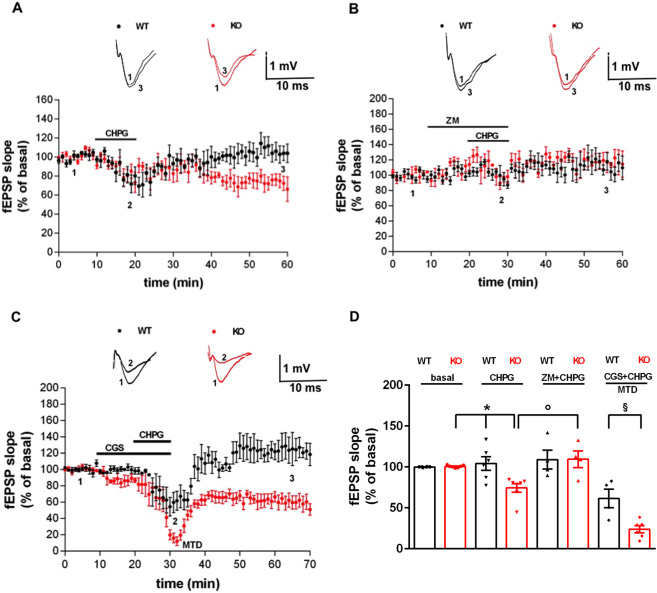

Fmr1 KO mice and age-matched (10 weeks) control WT mice showed comparable basal transmission and paired-pulse facilitation, as previously reported55,56. We aimed at testing if A2AR ligands modulate the slight synaptic depression induced by the weak, selective mGlu5R agonist CHPG. In Fig. 1A we show that CHPG (300 μM over 10 min) induced a longer synaptic depression in the fEPSP recorded in Fmr1 KO mice (74.39 ± 5.26% of basal slope after 30 min of washout, n = 4 animals, 7 slices; *p < 0.01 vs. basal and *p < 0.05 vs. WT, Mann-Whitney test, Fig. 1A, D), while in WT mice the synaptic transmission fully and immediately recovered after the CHPG application (104.20 ± 8.28% of basal slope after 30 min of washout, n = 5 animals, 6 slices). In Fmr1 KO mice (Fig. 1B) the effect of CHPG on synaptic depression was prevented by the selective A2AR antagonist ZM241385 (ZM; 100 nM; 109.40 ± 10.13% of basal, n = 3 animals, 4 slices; °p < 0.05 vs. CHPG alone, Mann-Whitney test, Fig. 1B, D). Oppositely, the selective A2AR agonist CGS21680 (CGS; 100 nM; Fig. 1C) potentiated the CHPG-induced effect, particularly in terms of MTD (23.80 ± 4.33% of basal, n = 5 animals, 6 slices; §p < 0.05 vs. CGS + CHPG in WT, Mann-Whitney test, Fig. 1C, D).

Fig. 1. The CHPG-induced synaptic depression in Fmr1 KO mice is modulated by A2AR ligands.

A The selective mGlu5R agonist CHPG induced a long-lasting synaptic depression in the fEPSP recorded in Fmr1 KO mice (n = 4 animals, 7 slices, *p < 0.01 vs. basal and *p < 0.05 vs. WT, Mann-Whitney test), while in WT mice (n = 5 animals, 6 slices) the synaptic transmission recovered completely after the CHPG application. B In the Fmr1 KO mice, the long-lasting effect of CHPG on synaptic depression was prevented by a pre-treatment with the selective A2AR antagonist ZM241385 (n = 3 animals, 4 slices, °p < 0.05 vs. CHPG alone in Fmr1 KO, Mann-Whitney test). C A pre-treatment with the selective A2AR agonist CGS21680 potentiated CHPG-induced MTD in Fmr1 KO mice (n = 5 animals, 6 slices, §p < 0.05 vs. CGS + CHPG in WT, Mann-Whitney test). D The dot-plot graph summarizes the results. Insets in panels (A–C) show representative fEPSP recordings in correspondence of baseline (1), MTD (2), or late washout (3). Calibration bars: 1 mV, 10 ms.

KW6002 abolished the abnormal mGlu5R-dependent LTD in Fmr1 KO mice

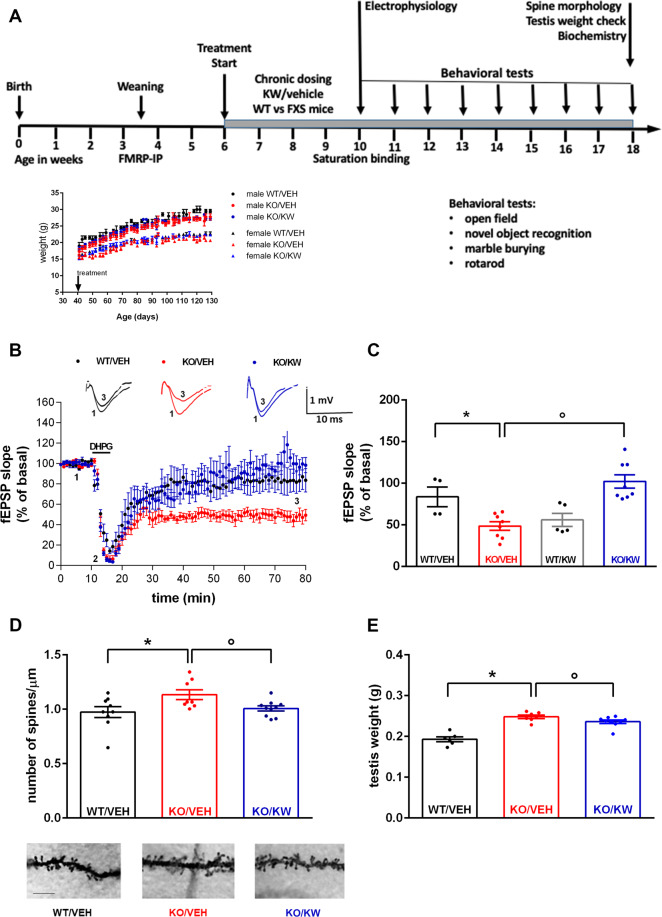

An orally active A2AR antagonist KW6002, or vehicle (the experimental groups are hereafter indicated as WT/VEH, WT/KW, KO/VEH, KO/KW), was administered to the mice. Electrophysiology experiments in hippocampal slices from Fmr1 KO mice treated in vivo with KW6002 (from 6 weeks of age, for 4 weeks, 4 mg/kg per day, PO; Fig. 2A and inset inside showing that treatment did not affect body weight) were performed. In line with previous studies46, in KO/VEH mice the group 1-mGluR agonist DHPG (100 μM over 5 min) induced a clear LTD (48.45 ± 5.19% of baseline; n = 5 animals, 8 slices), which was larger compared to WT/VEH mice (n = 2 animals, 4 slices; *p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test; Fig. 2B, C). Interestingly, the DHPG-induced LTD was strongly reduced in KO/KW mice, where fEPSP slope recovered to 102.10 ± 8.05% of baseline (n = 4 animals, 8 slices; °p < 0.01 vs. KO/VEH, Mann-Whitney test; Fig. 2B, C). No differences were observed between WT/KW and WT/VEH mice (Fig. 2C), except for a non-significant reduction in WT/KW group.

Fig. 2. In vivo administration of the selective A2AR antagonist KW6002 reduces synaptic alterations and macroorchidism in Fmr1 KO mice.

A Timeline of chronic oral treatment schedule (4 mg/kg per day, PO) between 6 and 18 weeks of age. The inset shows that KW6002-chronic treatment did not affect body growth. The bodyweight increase during the 12 weeks of chronic treatment was not different between KW- and VEH-treated animals of both sexes. B The DHPG-induced LTD was strongly reduced in KO/KW mice (n = 4 animals, 8 slices, °p < 0.01 vs. KO/VEH, n = 5 animals, 8 slices, Mann-Whitney test). No difference was observed between WT/KW and WT/VEH mice (n = 2 animals, 5 slices, and n = 2 animals, 4 slices, respectively); a difference was observed between WT/VEH and KO/VEH mice (*p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test). C The dot-plot graph summarizes the results. Insets in panel (B) show representative fEPSP recordings in correspondence of baseline (1) and late washout (3). Calibration bars: 1 mV, 10 ms. D Spine density was higher in dendrites of KO/VEH compared to WT/VEH mice (WT/VEH n = 9 and KO/VEH n = 8; *p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test) and normalized in chronically treated KO/KW mice (n = 10, KO/KW vs. KO/VEH: °p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test). The histograms show dendritic spines number (number of spines/dendrite segment length) counted on 5 segments per neuron in pyramidal neurons in the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus in WT and Fmr1 KO mice, VEH- or KW-treated. Bars represent mean ± SEM. Representative images of Golgi-stained sections of the dorsal hippocampus and of apical dendrite segments of CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neurons (scale bar: 25 μm) in WT and Fmr1 KO mice, VEH- or KW-treated, are reported below the graph. E KO/VEH mice (n = 7; 18 weeks of age) presented a larger testis weight compared to WT/VEH mice (n = 6; genotype effect: *p < 0.01, Mann-Whitney test), which was corrected in KO/KW mice (n = 9; treatment effect: °p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test).

KW6002 normalized hippocampal dendritic spine density and macroorchidism in Fmr1 KO mice

Next we analyzed the spine number and morphology after KW6002 treatment. As shown in Fig. 2D, a significantly larger number of spines/μm was observed in the hippocampus of Fmr1 KO vs. WT mice (WT/VEH: 0.974 ± 0.049, n = 9 neurons; KO/VEH: 1.134 ± 0.046, n = 8 neurons; *p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test). Such an abnormal dendritic spine density was normalized in Fmr1 KO mice treated with KW6002 over 4 weeks (KO/KW: 1.007 ± 0.023, n = 10 neurons; °p < 0.05 vs. KO/VEH, Mann-Whitney test). In addition, testis weight, as expected, resulted larger in KO/VEH mice in comparison to WT/VEH mice (respectively, 0.2481 ± 0.0042 g, n = 7 and 0.1932 ± 0.0060 g; n = 6; *p < 0.01, Mann-Whitney test). Macroorchidism was normalized by KW6002 in KO/KW mice (0.2361 ± 0.0042 g; n = 9; °p < 0.05 vs. KO/VEH, Mann-Whitney test; Fig. 2E).

Chronic KW6002 corrects cognitive learning deficit in Fmr1 KO mice

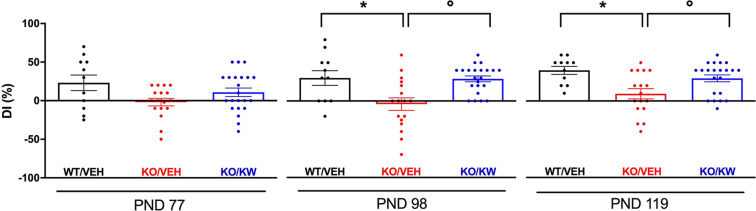

We then analyzed the cognitive learning in the Fmr1 KO treated mice. In the NOR test (NORT), the time spent exploring the familiar and novel objects was quantified. We found that starting from PND 98 (Fig. 3) KO/VEH mice exhibited a reduced ability to discern between old and new objects as indicated by the lower value of discrimination index (DI: −4.12 ± 8.19 in KO/VEH, n = 16, vs. 30.00 ± 9.63 in WT/VEH, n = 11; *p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test). Such impairment was attenuated by KW6002 (DI: 28.86 ± 3.84 in KO/KW; °p < 0.01 vs. in KO/VEH, Mann-Whitney test). The rescuing effect of KW6002 was maintained also at PND 119 (DI: 29.55 ± 4.48 in KO/KW, n = 22, vs. 9.41 ± 6.72 in KO/VEH, n = 16; °p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test). KW6002 did not affect hyperactivity, stereotyped behavior, and motor coordination of mice (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 3. Effect of KW6002 on the preference for a novel object in Fmr1 KO mice.

In the NORT PND 98 KO/VEH mice exhibited a reduced ability to discern between old and new objects, as indicated by the lower DI in comparison to WT/VEH mice (*p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test); chronic treatment with KW6002 induced an increase in DI in Fmr1 KO mice (°p < 0.01, in comparison to KO/VEH, Mann-Whitney test); at PND 119 the lower DI of KO/VEH mice in comparison to WT/VEH mice (*p < 0.01, Mann-Whitney test) resulted increased after KW6002 treatment (°p < 0.05, in comparison to KO/VEH, Mann-Whitney test).

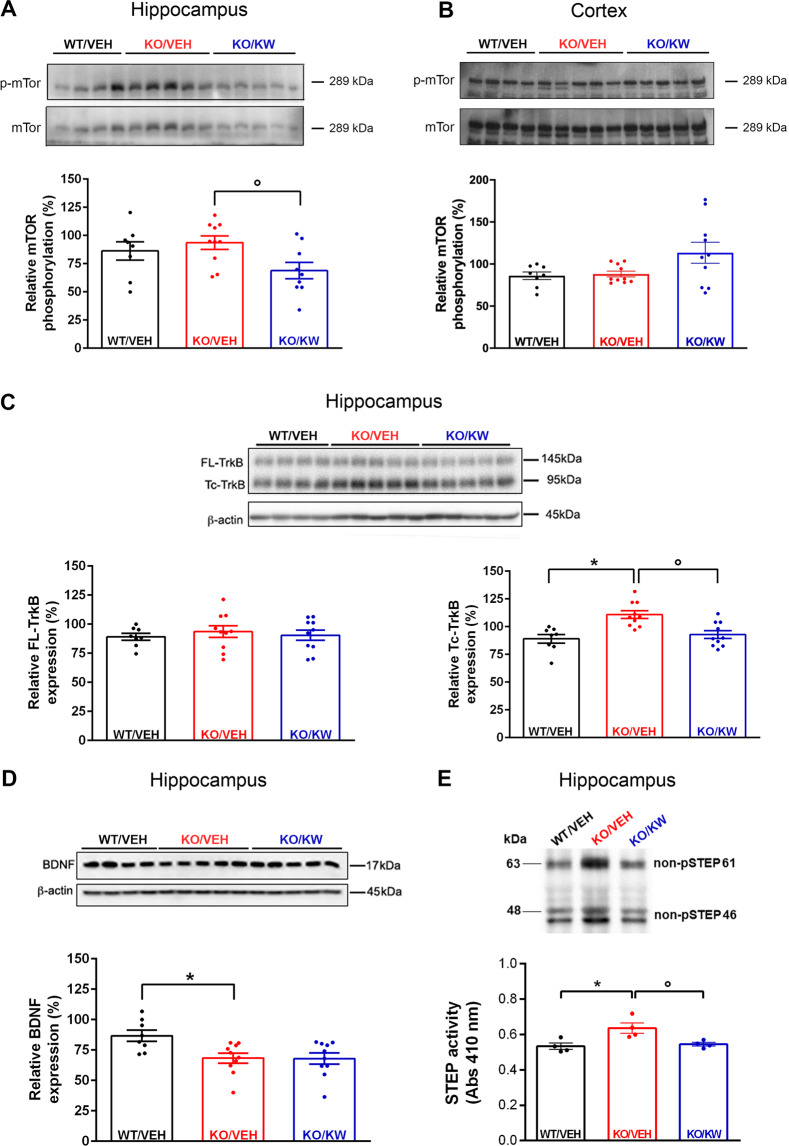

Effect of chronic KW6002 on mTOR signaling

To investigate if A2AR blockade modulates one of the pathways found altered in FXS22,38,57,58, we analyzed mTOR (Fig. 4A, B) phosphorylation levels in hippocampus and cortex from WT and Fmr1 KO mice treated with KW6002 or vehicle. In the hippocampus, the mTOR phosphorylation level was slightly increased in KO/VEH mice (93.66 ± 5.93; n = 10; Fig. 4A) compared to WT/VEH mice (86.32 ± 8.09; n = 8; p = 0.46 vs. KO/VEH, Mann-Whitney test). KW6002 reduced the mTOR phosphorylation level in Fmr1 KO mice (68.83 ± 7.32; n = 9; °p < 0.05 vs. KO/VEH, Mann-Whitney test; Fig. 4A). No difference was detected in mTOR phosphorylation in the cortex (Fig. 4B). KW6002 did not reduce ERK1/2 hyper-phosphorylation found in the cortex of Fmr1 KO mice (Supplementary Fig. S2b).

Fig. 4. KW6002 modulates mTOR, TrkB, and STEP in the hippocampus of Fmr1 KO mice.

A Upper panel, representative western blot showing protein levels of mTOR and p-mTOR in the hippocampus. Each lane corresponds to tissue lysates from independent mice. Lower panel, histogram shows the quantification of the mTOR phosphorylation levels in KO/VEH mice (n = 10) compared to WT/VEH mice (n = 8; p = 0.46, Mann-Whitney test). mTOR phosphorylation level in the Fmr1 KO mice upon chronic treatment with KW6002 (n = 9; °p < 0.05 vs. KO/VEH, Mann-Whitney test). B Upper panel, representative western blot showing protein levels of mTOR and p-mTOR in the cortex. Lower panel, histogram shows the quantification of mTOR phosphorylation in the different experimental groups. (A, B) the histograms indicate the % of phosphoproteins normalized to respective total protein levels. C Upper panel, representative western blot showing protein levels of FL-TrkB and Tc-TrkB in the hippocampus. Lower panel, quantification of FL-TrkB receptor level (left histogram) and Tc-TrkB receptor level (right histogram) in the hippocampus of KO/VEH (n = 10) in comparison to WT/VEH mice (n = 8; *p < 0.01, Mann-Whitney test). The treatment with KW6002 was able to correct this alteration in the Fmr1 KO mice (n = 10; °p < 0.01 vs. KO/VEH, Mann-Whitney test, right histogram); β-actin was used as normalizer. D Upper panel, representative western blot showing BDNF protein levels in the hippocampus. Lower panel, histogram shows reduced levels of mature BDNF in KO/VEH (n = 10; *p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test) compared to WT/VEH mice (n = 8), but such a change was not affected by the KW6002 treatment (n = 10); β-actin was used as normalizer. E Upper panel, representative western blot showing protein levels of the two isoforms (61 and 46 kDa) of STEP protein. Lower panel, histogram shows an increased STEP activity in the hippocampus of KO/VEH compared to WT/VEH mice (n = 4; *p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test). Chronic KW6002 treatment reduced significantly STEP activity in the Fmr1 KO mice (n = 4; °p < 0.05 vs. KO/VEH, Mann-Whitney test). The expression of the two isoforms (61 and 46 kDa) of STEP protein evaluated by western blot shows a similar trend (upper panel).

Correction of TrkB and STEP signaling

We next analyzed a possible correction of other impaired molecular pathways in FXS. The expression of both full-length and truncated forms of TrkB receptor (FL-TrkB and Tc-TrkB, respectively; Fig. 4C), the mature form of BDNF (Fig. 4D), and STEP (activity and expression, Fig. 4E) were evaluated in the hippocampus of WT and Fmr1 KO mice treated with KW6002 or vehicle. While no change was found in the FL-TrkB level (Fig. 4C, left panel), western blot analysis revealed a larger level of Tc-TrkB receptor in KO/VEH mice (110.80 ± 3.53; n = 10; *p < 0.01, Mann-Whitney test; Fig. 4C, right panel) in comparison to WT/VEH mice (89.09 ± 3.87; n = 8). KW6002 corrected this alteration in Fmr1 KO mice (92.84 ± 3.47; n = 10; °p < 0.01 vs. KO/VEH, Mann-Whitney test; Fig. 4C, right panel). We observed a lower level of the mature BDNF form in KO/VEH mice, which was not affected by KW6002 (Fig. 4D). STEP activity was increased in KO/VEH mice (0.64 ± 0.03; n = 4; *p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test; Fig. 4E) compared to WT/VEH mice (0.53 ± 0.04; n = 4) and KW6002 treatment reduced STEP activity in Fmr1 KO mice (0.54 ± 0.01; n = 4; °p < 0.05 vs. KO/VEH, Mann-Whitney test; Fig. 4E). Consistently, STEP protein expression was also increased in KO/VEH mice and reduced by KW6002 treatment in Fmr1 KO mice, as indicated by the western blot analysis performed by using an antibody that recognizes the two isoforms (61 and 46 kDa) of STEP (upper panel in Fig. 4E).

A2AR mRNA is part of the FMRP complex

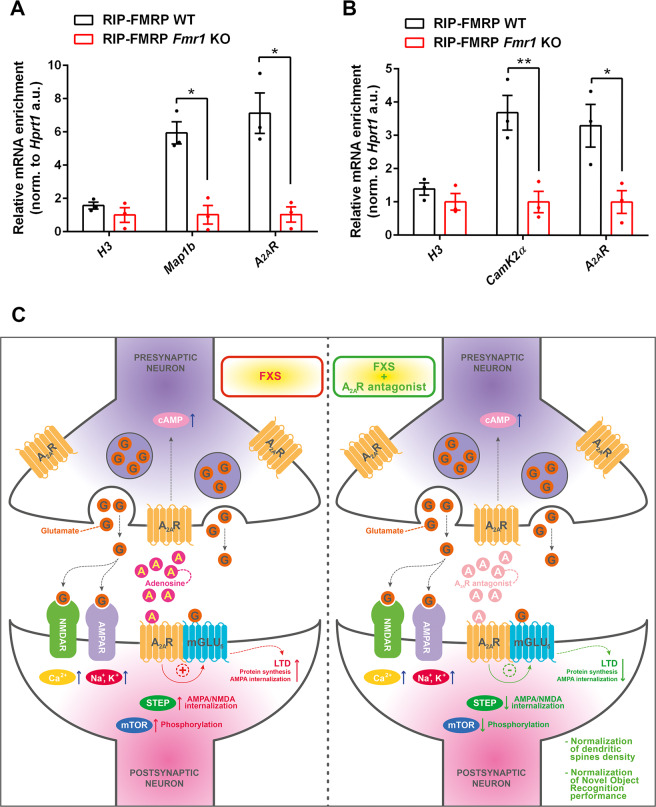

FMRP is an RNA-binding protein that regulates different aspects of mRNA metabolism9–14. To further investigate A2AR involvement in the FXS pathology we explored a possible association of FMRP to A2AR mRNA. To assess the presence of A2AR mRNA in the FMRP complex we performed an RNA immunoprecipitation with specific anti-FMRP antibodies54 using different brain regions from WT and Fmr1 KO mice, followed by amplification of the associated mRNAs (Supplementary Table S1). Notably, we found that FMRP associates with A2AR mRNA in cortex and hippocampus (Fig. 5A). A2ARs are mostly abundant in the striatum, consistently, we detected the associations of A2AR mRNA with FMRP also in this brain area (Fig. 5B). These findings suggest that FMRP could control A2AR mRNA metabolism leading to increased protein production.

Fig. 5. A2AR mRNA is part of the FMRP complex. The model summarizes the possible mechanisms of action due to A2AR blockade in Fmr1 KO mice.

A, B A2AR mRNA is part of the FMRP complex. C Model summarizing the possible mechanisms of action due to A2AR blockade in Fmr1 KO mice. (A) FMRP binds A2AR mRNA in cortex and hippocampus. H3, Map1b, and A2AR mRNAs were quantified by RT-qPCR. Shown is the enrichment of the immunoprecipitation/total, relative to Hprt1 mRNA, mean ± SEM, n = 3; p-values were calculated by Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05). Map1b mRNA, a well-described FMRP target mRNA, was used as a positive control. (B) FMRP binds A2AR mRNA in the striatum. H3, CamK2α, and A2AR mRNAs were quantified by RT-qPCR. Shown is the enrichment of the immunoprecipitation/total, relative to Hprt1 mRNA, mean ± SEM, n = 3; p-values were calculated by Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01). CamK2α mRNA, a well-described FMRP target mRNA, was used as a positive control. (C) In the left panel, the increased postsynaptic functional interaction between the A2A and the mGlu5 receptors in Fmr1 KO mice, could contribute to the aberrant mGlu5R-dependent LTD and mTOR hyper-phosphorylation in the FXS hippocampus. Here, the excessive STEP activity, which in turn contributes to AMPA internalization, could be directly ascribed to the aberrant A2AR signaling. A2AR abnormalities might derive from the defective FMRP complex control of A2AR mRNA translation at the early stages of mouse neurodevelopment. In the right panel, according to our data, the beneficial synaptic and cognitive effects deriving from A2AR blockade in the Fmr1 KO mice could depend on the reduction of mGlu5R/mTOR and STEP activities. The TrkB/BDNF pathway could also partially contribute to it.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to evaluate if A2ARs play a role in FXS and if their blockade could modulate the physiological and behavioral phenotypes observed in the Fmr1 KO mice. mGlu5Rs are under the tight control of A2ARs in different brain areas35,36,59–63. As for the hippocampus, we demonstrated that A2ARs need to be activated to allow the effects of mGlu5Rs to occur36. Here we investigated if the functional interaction between A2AR and mGlu5 receptors in the hippocampus was altered in the Fmr1 KO mouse. We found that A2AR differently modulates the hippocampal mGlu5R-induced synaptic effects in Fmr1 WT and KO mice. The ability of the A2AR agonist CGS21680 to potentiate CHPG-induced synaptic depression was found greater in Fmr1 KO vs. WT mice, suggesting that the functional synergistic coupling between A2A and mGlu5 receptors is larger in the absence of FMRP. We also tested if the chronic pharmacological blockade of A2ARs restored the synaptic and behavioral phenotypes of Fmr1 KO mice. We started by evaluating the LTD induced by the group 1-mGluRs agonist DHPG, and found that in vivo treatment with the A2AR antagonist KW6002 normalized the DHPG-LTD in Fmr1 KO mice; this correction is likely due to enduring changes induced by chronic A2AR antagonism, different from the consequences of its acute blocking. Furthermore, we found that KW6002 reduced dendritic spine density in Fmr1 KO mice. Although we do not know if such an effect could explain the LTD normalization, it is noteworthy that the colocalization of A2A and mGlu5 receptors has been found mostly in synaptic contacts of cultured rat hippocampal neurons, where the A2ARs are concentrated36.

In addition, we observed a reduction of learning deficit in the NORT behavioral paradigm. Such a beneficial effect exerted by KW6002 on the Fmr1 KO mice might be the direct in vivo outcome of synaptic ameliorations of impaired LTD and dendritic spine density. It has been already demonstrated that synaptic plasticity, and particularly LTD, serves as a cellular substrate for the encoding of spatial object recognition64, and that also a non-genetic dendritic spine alteration (e.g. stress-induced reduction) is accompanied by a worsening in the NORT performance65. The efficacy of KW6002 in the cognitive domain is encouraging, considering that cognitive disabilities have the greatest impact on people living with FXS and their families66. Also, regarding the beneficial effect of KW6002 on the NORT performance, the inactivation of A2ARs already proved to reduce cognitive dysfunctions in many different animal models useful to study neurodegenerative/neurological diseases67–70. After completing the behavioral tests, we assessed the possible impact of A2ARs modulation on some measurable markers previously used to evaluate the preclinical potential of mGlu5R inhibitors22. According to the variability of mTOR phosphorylation described in the literature38,57,58,71,72, a slightly larger level of mTOR phosphorylation was detected in the hippocampus of the Fmr1 KO, consistent with previous observations in the visual cortex22; interestingly, KW6002 was effective to reduce mTOR phosphorylation. Differently, the high variability in the signal of ERK1/2 levels prevented us from observing a clear effect of KW6002 on the hyper-phosphorylation found in the cortex of Fmr1 KO mice. Besides the mGlu5R/mTOR modulation, we found that the A2ARs directly impact other pathways altered in FXS, such as TrkB/BDNF and STEP73. Several studies suggest that TrkB/BDNF signaling pathway plays a role in FXS41, showing aberrances of BDNF and TrkB expression in murine brain lacking FMRP74–76. A2ARs are required for the BDNF-induced potentiation of synaptic transmission in the mouse hippocampus39. In the present study, we found that the Tc-TrkB receptor level is increased in the hippocampus of Fmr1 KO mice, and can be normalized by blocking the A2ARs. Overexpression of Tc-TrkB receptor can inhibit full-length tyrosine kinase signaling77–80 and affect the control of dendritic morphology81. Notably, we found a decreased level of BDNF in the hippocampus of Fmr1 KO mice, and the reduction of Tc-TrkB receptor in vivo partially rescues the phenotypes caused by loss of one BDNF allele82.

The absence of FMRP upregulates the translation of the mRNA encoding the STEP protein42,83. As a result, STEP levels are increased in the hippocampus of Fmr1 KO mice42 and the pharmacological blockade84 or genetic deletion42 of STEP corrects Fmr1 KO mice phenotypes. A2ARs modulate the activity of this phosphatase40. An increased level of STEP activity is present in the striatum of A2AR-overexpressing rats and normalized by the A2AR antagonist85. Accordingly, in the present work, we confirmed that STEP activity is higher in the hippocampus of Fmr1 KO mice and normalized by the A2AR antagonist.

Finally, we detected the presence of the A2AR mRNA in the FMRP complex in different brain areas of juvenile mice. These findings suggest a control of A2AR mRNA mediated by FMRP, possibly at the level of mRNA translation and at early stages of mouse neurodevelopment. Future investigation are necessary in the context of an unchanged affinity and density of the A2ARs observed in adult Fmr1 KO mice (Table S2), suggesting that A2AR abnormalities could start early in development and have an effect at later stages.

The beneficial effects deriving from A2AR blockade in Fmr1 KO mice could depend on the contemporary reduction of mGlu5R/mTOR, TrkB/BDNF, and STEP activities, as summarized in the proposed model (Fig. 5C).

Considering the mGlu5R-relevant role in basal synaptic transmission and plasticity86,87, mGlu5R inhibitors might cause serious adverse events in humans88. Furthermore, treatment with mGlu5R inhibitors might likely result in tolerance development27, possibly being responsible for the disappointing outcome of the clinical trials88.

The use of the A2AR antagonists could help overcoming these limitations. Given the complexity of the molecular abnormalities observed in FXS26,89, targeting different pathways at the same time could represent a better therapeutic strategy.

The potential reliability of KW6002 is supported by pharmacodynamics/pharmacokinetics properties44 and safety90, being already used for Parkinson’s disease.

In conclusion, although further studies are needed to clarify the cross-talk between A2A and mGlu5 receptors in the FXS condition, these findings suggest that A2AR antagonists could represent a possible novel therapeutic tool in FXS.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Stefano Fidanza and Alessio Gugliotta for technical assistance with animal work and Luigi Suglia for his invaluable help with the artwork. The research was supported by a fellowship from FRAXA Research Foundation to A.M., principal investigator; A.B. co-PI; Z.B. Postdoctoral Fellow, by Associazione Italiana Sindrome X Fragile to A.M., Telethon GGP15257 to C.B., Associazione Italiana Sindrome X Fragile to C.B., PRIN2017 to C.B.

Author contributions

A.F. and Z.B. performed behavioral and biochemistry experiments, participated in writing the manuscript, and in the study design. A.B. performed dendritic spine morphology experiments, participated in writing the manuscript and in the study design. C.M. performed STEP-evaluation experiments. F.V. and K.V. performed and evaluated saturation binding experiments. L.P. and G.P. performed the FMRP-RIP experiments. A.P. participated to in vivo and behavioral experiments. M.A. participated in dendritic spine morphology experiments. C.B and P.P. contributed to the study design and to the writing of the manuscript. A.M. performed electrophysiology experiments, designed and directed the study, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Antonella Ferrante, Zaira Boussadia

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41398-021-01238-5.

References

- 1.de Vries BB, Halley DJ, Oostra BA, Niermeijer MF. The fragile X syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 1998;35:579–589. doi: 10.1136/jmg.35.7.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin P, Warren ST. Understanding the molecular basis of fragile X syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:901–908. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.6.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tranfaglia MR. The psychiatric presentation of fragile X: evolution of the diagnosis and treatment of the psychiatric comorbidities of fragile X syndrome. Dev. Neurosci. 2011;33:337–348. doi: 10.1159/000329421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman I, Leader G, Chen JL, Mannion A. An analysis of challenging behavior, comorbid psychopathology, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in fragile X syndrome. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015;38:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagerman RJ, et al. Fragile X syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017;3:17065. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salcedo-Arellano MJ, Dufour B, McLennan Y, Martinez-Cerdeno V, Hagerman R. Fragile X syndrome and associated disorders: clinical aspects and pathology. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020;136:104740. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.104740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oostra BA, Willemsen R. A fragile balance: FMR1 expression levels. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12(Spec No. 2):R249–R257. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siomi H, Siomi MC, Nussbaum RL, Dreyfuss G. The protein product of the fragile X gene, FMR1, has characteristics of an RNA-binding protein. Cell. 1993;74:291–298. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90420-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dictenberg JB, Swanger SA, Antar LN, Singer RH, Bassell GJ. A direct role for FMRP in activity-dependent dendritic mRNA transport links filopodial-spine morphogenesis to fragile X syndrome. Dev. Cell. 2008;14:926–939. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasciuto E, Bagni C. SnapShot: FMRP mRNA targets and diseases. Cell. 2014;158:1446–1446.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasciuto E, Bagni C. SnapShot: FMRP interacting proteins. Cell. 2014;159:218–218.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banerjee A, Ifrim MF, Valdez AN, Raj N, Bassell GJ. Aberrant RNA translation in fragile X syndrome: from FMRP mechanisms to emerging therapeutic strategies. Brain Res. 2018;1693(Pt. A):24–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bagni C, Zukin RS. A synaptic perspective of fragile X syndrome and autism spectrum disorders. Neuron. 2019;101:1070–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah S, et al. FMRP control of ribosome translocation promotes chromatin modifications and alternative splicing of neuronal genes linked to autism. Cell Rep. 2020;30:4459–4472.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sung YJ, Conti J, Currie JR, Brown WT, Denman RB. RNAs that interact with the fragile X syndrome RNA binding protein FMRP. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;275:973–980. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bagni C, Greenough WT. From mRNP trafficking to spine dysmorphogenesis: the roots of fragile X syndrome. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;6:376–387. doi: 10.1038/nrn1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis JK, Broadie K. Multifarious functions of the fragile X mental retardation protein. Trends Genet. 2017;33:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacquemont S, et al. Protein synthesis levels are increased in a subset of individuals with fragile X syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018;27:2039–2051. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bear MF, Huber KM, Warren ST. The mGluR theory of fragile X mental retardation. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dölen G, et al. Correction of fragile X syndrome in mice. Neuron. 2007;56:955–962. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krueger DD, Bear MF. Toward fulfilling the promise of molecular medicine in fragile X syndrome. Annu. Rev. Med. 2011;62:411–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-061109-134644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michalon A, et al. Chronic pharmacological mGlu5 inhibition corrects fragile X in adult mice. Neuron. 2012;74:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacquemont S, et al. Epigenetic modification of the FMR1 gene in fragile X syndrome is associated with differential response to the mGluR5 antagonist AFQ056. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:64ra1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacquemont S, et al. The challenges of clinical trials in fragile X syndrome. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2014;231:1237–1250. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3289-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mullard A. Fragile X disappointments upset autism ambitions. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015;14:151–153. doi: 10.1038/nrd4555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berry-Kravis EM, et al. Drug development for neurodevelopmental disorders: lessons learned from fragile X syndrome. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017;17:280–299. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan QJ, Rammal M, Tranfaglia M, Bauchwitz RP. Suppression of two major fragile X syndrome mouse model phenotypes by the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP. Neuropharmacology. 2015;49:1053–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2001;53:527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klinger M, Freissmuth M, Nanoff C. Adenosine receptors: G protein-mediated signalling and the role of accessory proteins. Cell Signal. 2002;14:99–108. doi: 10.1016/S0898-6568(01)00235-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen JF, et al. Adenosine A2A receptors and brain injury: broad spectrum of neuroprotection, multifaceted actions and “fine tuning” modulation. Prog. Neurobiol. 2007;83:310–331. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Popoli P, et al. Blockade of striatal adenosine A2A receptor reduces, through a presynaptic mechanism, quinolinic acid-induced excitotoxicity: possible relevance to neuroprotective interventions in neurodegenerative diseases of the striatum. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:1967–1975. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01967.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Popoli P, et al. Functions, dysfunctions and possible therapeutic relevance of adenosine A2A receptors in Huntington’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2007;81:331–348. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Popoli P, Blum D, Domenici MR, Burnouf S, Chern Y. A critical evaluation of adenosine A2A receptors as potentially “druggable” targets in Huntington’s disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008;14:1500–1511. doi: 10.2174/138161208784480117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunha RA. Neuroprotection by adenosine in the brain: from A(1) receptor activation to A(2A) receptor blockade. Purinergic Signal. 2005;1:111–134. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-0649-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Domenici MR, et al. Permissive role of adenosine A2A receptors on metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5)-mediated effects in the striatum. J. Neurochem. 2004;90:1276–1279. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tebano MT, et al. Adenosine A2A receptors and metabotropic glutamate 5 receptors are co-localized and functionally interact in the hippocampus: a possible key mechanism in the modulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate effects. J. Neurochem. 2005;95:1188–1200. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osterweil EK, Krueger DD, Reinhold K, Bear MF. Hypersensitivity to mGluR5 and ERK1/2 leads to excessive protein synthesis in the hippocampus of a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:15616–15627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3888-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma A, et al. Dysregulation of mTOR signaling in fragile X syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:694–702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3696-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tebano MT, et al. Adenosine A(2A) receptors are required for normal BDNF levels and BDNF-induced potentiation of synaptic transmission in the mouse hippocampus. J. Neurochem. 2008;104:279–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiodi V, et al. Cocaine induced changes of synaptic transmission in the striatum are modulated by adenosine A2A receptors and involve the tyrosine phosphatase STEP. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:569–578. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castrén ML, Castrén E. BDNF in fragile X syndrome. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76(Pt C):729–736. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goebel-Goody SM, et al. Therapeutic implications for striatal-enriched protein tyrosine phosphatase (STEP) in neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacol. Rev. 2012;64:65–87. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.The Dutch-Belgian Fragile X Consortium. Fmr1 knockout mice: a model to study fragile X mental retardation. Cell. 1994;78:23–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orr AG, et al. Istradefylline reduces memory deficits in aging mice with amyloid pathology. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018;110:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anderson WW, Collingridge GL. The LTP Program: a data acquisition program for on-line analysis of long-term potentiation and other synaptic events. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2001;108:71–83. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0270(01)00374-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huber KM, Gallagher SM, Warren ST, Bear MF. Altered synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of fragile X mental retardation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:7746–7750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122205699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Irwin SA, et al. Dendritic spine and dendritic field characteristics of layer V pyramidal neurons in the visual cortex of fragile-X knockout mice. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2002;111:140–146. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leuner B, Falduto J, Shors TJ. Associative memory formation increases the observation of dendritic spines in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:659–665. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00659.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paylor R, et al. Alpha7 nicotinic receptor subunits are not necessary for hippocampal-dependent learning or sensorimotor gating: a behavioral characterization of Acra7-deficient mice. Learn. Mem. 1998;5:302–316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dawson GR, Flint J, Wilkinson LS. Testing the genetics of behavior in mice. Science. 1999;285:2068. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kazdoba TM, Leach PT, Silverman JL, Crawley JN. Modeling fragile X syndrome in the Fmr1 knockout mouse. Intractable Rare Dis. Res. 2014;3:118–133. doi: 10.5582/irdr.2014.01024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferrante A, et al. The adenosine A(2A) receptor agonist T1-11 ameliorates neurovisceral symptoms and extends the lifespan of a mouse model of Niemann-Pick type C disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018;110:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2017.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mallozzi C, et al. Phosphorylation and nitration of tyrosine residues affect functional properties of Synaptophysin and Dynamin I, two proteins involved in exo-endocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1833:110–121. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferrari F, et al. The fragile X mental retardation protein-RNP granules show an mGluR-dependent localization in the post-synaptic spines. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2007;34:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Godfraind JM, et al. Long-term potentiation in the hippocampus of fragile X knockout mice. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1996;64:246–251. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960809)64:2<246::AID-AJMG2>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paradee W, et al. Fragile X mouse: strain effects of knockout phenotype and evidence suggesting deficient amygdala function. Neuroscience. 1999;94:185–192. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(99)00285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoeffer CA, et al. Altered mTOR signaling and enhanced CYFIP2 expression levels in subjects with fragile X syndrome. Genes Brain Behav. 2012;11:332–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2012.00768.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huber KM, Klann E, Costa-Mattioli M, Zukin RS. Dysregulation of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in mouse models of autism. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:13836–13842. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2656-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Popoli P, et al. The selective mGlu(5) receptor agonist CHPG inhibits quinpirole-induced turning in 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats and modulates the binding characteristics of dopamine D(2) receptors in the rat striatum: interactions with adenosine A(2a) receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:505–513. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00256-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferré S, et al. Synergistic interaction between adenosine A2A and glutamate mGlu5 receptors: implications for striatal neuronal function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:11940–11945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172393799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Díaz-Cabiale Z, et al. Metabotropic glutamate mGlu5 receptor-mediated modulation of the ventral striopallidal GABA pathway in rats. Interactions with adenosine A(2A) and dopamine D(2) receptors. Neurosci. Lett. 2002;324:154–158. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00179-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Coccurello R, Breysse N, Amalric M. Simultaneous blockade of adenosine A2A and metabotropic glutamate mGlu5 receptors increase their efficacy in reversing Parkinsonian deficits in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1451–1461. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rodrigues RJ, Alfaro TM, Rebola N, Oliveira CR, Cunha RA. Co-localization and functional interaction between adenosine A(2A) and metabotropic group 5 receptors in glutamatergic nerve terminals of the rat striatum. J. Neurochem. 2005;92:433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goh JJ, Manahan-Vaughan D. Spatial object recognition enables endogenous LTD that curtails LTP in the mouse hippocampus. Cereb. Cortex. 2013;23:1118–1125. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen Y, et al. Correlated memory defects and hippocampal dendritic spine loss after acute stress involve corticotropin-releasing hormone signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:13123–13128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003825107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weber JD, et al. Voice of people with fragile X syndrome and their families: reports from a survey on treatment priorities. Brain Sci. 2019;9:18. doi: 10.3390/brainsci9020018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li W, et al. Inactivation of adenosine A2A receptors reverses working memory deficits at early stages of Huntington’s disease models. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015;79:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tyebji S, et al. Hyperactivation of D1 and A2A receptors contributes to cognitive dysfunction in Huntington’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015;74:41–57. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dall’Igna OP, et al. Caffeine and adenosine A(2a) receptor antagonists prevent beta-amyloid (25-35)-induced cognitive deficits in mice. Exp. Neurol. 2007;203:241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Canas PM, et al. Adenosine A2A receptor blockade prevents synaptotoxicity and memory dysfunction caused by beta-amyloid peptides via p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:14741–14751. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3728-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ronesi JA, Huber KM. Homer interactions are necessary for metabotropic glutamate receptor-induced long-term depression and translational activation. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:543–547. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5019-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kumari D, et al. Identification of fragile X syndrome specific molecular markers in human fibroblasts: a useful model to test the efficacy of therapeutic drugs. Hum. Mutat. 2014;35:1485–1494. doi: 10.1002/humu.22699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Telias M. Molecular mechanisms of synaptic dysregulation in fragile X syndrome and autism spectrum disorders. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019;12:51. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Louhivuori V, et al. BDNF and TrkB in neuronal differentiation of Fmr1-knockout mouse. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011;41:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Takei N, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces mammalian target of rapamycin-dependent local activation of translation machinery and protein synthesis in neuronal dendrites. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:9760–9769. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1427-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Uutela M, et al. Reduction of BDNF expression in Fmr1 knockout mice worsens cognitive deficits but improves hyperactivity and sensorimotor deficits. Genes Brain. Behav. 2012;11:513–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2012.00784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Biffo S, Offenhäuser N, Carter BD, Barde YA. Selective binding and internalisation by truncated receptors restrict the availability of BDNF during development. Development. 1995;121:2461–2470. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eide FF, et al. Naturally occurring truncated TrkB receptors have dominant inhibitory effects on brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:3123–3129. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-10-03123.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Palko ME, Coppola V, Tessarollo L. Evidence for a role of truncated TrkC receptor isoforms in mouse development. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:775–782. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00775.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dorsey SG, et al. In vivo restoration of physiological levels of truncated TrkB.T1 receptor rescues neuronal cell death in a trisomic mouse model. Neuron. 2006;51:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yacoubian TA, Lo DC. Truncated and full-length TrkB receptors regulate distinct modes of dendritic growth. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:342–349. doi: 10.1038/73911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Carim-Todd L, et al. Endogenous truncated TrkB.T1 receptor regulates neuronal complexity and TrkB kinase receptor function in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:678–685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5060-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Darnell JC, et al. FMRP stalls ribosomal translocation on mRNAs linked to synaptic function and autism. Cell. 2011;146:247–261. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chatterjee M, et al. STEP inhibition reverses behavioral, electrophysiologic, and synaptic abnormalities in Fmr1 KO mice. Neuropharmacology. 2018;128:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mallozzi C, et al. The activity of the Striatal-enriched protein tyrosine phosphatase in neuronal cells is modulated by adenosine A2A receptor. J. Neurochem. 2020;152:284–298. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Collingridge GL, Isaac JT, Wang YT. Receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:952–962. doi: 10.1038/nrn1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim CH, Lee J, Lee JY, Roche KW. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: phosphorylation and receptor signaling. J. Neurosci. Res. 2008;86:1–10. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hagerman R, et al. Mavoglurant in fragile X syndrome: results of two open-label, extension trials in adults and adolescents. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:16970. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34978-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bagni C, Oostra BA. Fragile X syndrome: from protein function to therapy. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2013;161A:2809–2821. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kondo T, Mizuno Y, Japanese Istradefylline Study Group. A long-term study of istradefylline safety and efficacy in patients with Parkinson disease. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2015;38:41–46. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0000000000000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.