Abstract

Many people overestimate the health risks associated with nicotine, mistakenly perceiving nicotine as the main carcinogen in cigarettes and a leading cause of smoking-related diseases. Health professionals have been calling for public education programs to correct nicotine misperceptions in the hope that a lower risk perception of nicotine could encourage the use of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). However, a lower risk perception of nicotine could also lower perceived risk of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes). This paper evaluated the necessity of correcting nicotine misperceptions and explored possible intervention strategies to increase use of NRT and decrease use of e-cigarettes. In Study 1, smokers were surveyed about their perceptions of nicotine harm, and attitudes and intention towards using NRT and e-cigarettes. Results showed that overestimation of nicotine harm was associated with e-cigarette attitude and intention, but not with NRT. Informed by the survey results, three correction messages (a nicotine message, an NRT message, and an e-cigarette message) were developed and experimentally tested in Study 2 on both tobacco users and non-tobacco users. The nicotine message lowered people’s perception of nicotine harm but it did not change attitude and intention towards tobacco product use. The NRT message also failed to influence NRT attitudes and intentions. The e-cigarette message significantly lowered attitudes and intentions to use e-cigarette.

A large proportion of both smokers and non-smokers have misperceptions about the health risks associated with nicotine use. Some people believe nicotine is completely safe and harmless, while others see nicotine as the main carcinogen in cigarettes and the leading cause of tobacco-related diseases (e.g. lung cancer and heart attack)(Hendricks & Brandon, 2008; S. Y. Smith, Curbow, & Stillman, 2007; Wikmans & Ramström, 2010). Such misperceptions are prevalent even among highly educated populations and those working in the health industry (Borrelli & Novak, 2007; Patel, Peiper, & Rodu, 2013).

Health professionals have been calling for public education programs to correct such misperceptions, mainly for the purpose of encouraging use of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) (Ferguson et al., 2011; Pacek, Rass, & Johnson, 2017; Patel et al., 2013; Wilson, Peace, Edwards, & Weerasekera, 2011), but NRT is not the only tobacco product that delivers nicotine without the combustion products in cigarettes. Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are also nicotine delivery systems. By correcting nicotine misperceptions, the perceived risk of NRT may be lowered, but perceived risk of e-cigarettes may also be lowered.

The scientific community has consistently evaluated NRT as a safe and effective quitting tool, but no such consensus has ever been reached for e-cigarettes. In a recent comprehensive review of the health effects of e-cigarette use, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Committee concluded the long-term health effects of e-cigarettes is unknown and the evidence on the efficacy of e-cigarettes as cessation aids is insufficient (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018).

When addressing the issue of nicotine misperceptions, we are faced with a dilemma. To improve public health, we would like to increase NRT use and reduce e-cigarettes use, and nicotine misperceptions are closely connected to both products. It seems almost impossible to achieve both goals at the same time. In theory, when people see nicotine as a carcinogen, they perceive higher risk in both NRT and e-cigarettes; when people see nicotine per se as safe, they perceive lower risk in both NRT and e-cigarettes.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the necessity of correcting nicotine misperceptions and explore possible intervention strategies to increase use of nicotine replacement therapy and decrease use of electronic cigarettes.

Misperceptions are defined as beliefs that are not supported “by expert consensus contemporaneous with the time period of this study” (Tan, Lee, & Chae, 2015, p.675). A distinction needs to be made between misperceptions and contested information. In the health domain contested information mainly includes preliminary findings about novel procedures or products whose overall health effects remain inconclusive. Contested information, such as e-cigarette’s efficacy as a quitting tool, is not the focus of this article.

Misperceptions of Nicotine Harm

Nicotine addiction is the primary reason that smokers continue to smoke, but nicotine is not the major cause of adverse health effects among cigarette smokers. Research has generally established that combustion products like nitrosamines and carbon monoxide, rather than nicotine, are responsible for the main damages done by cigarette smoke (Royal College Physicians, 2016; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Nicotine itself is not a carcinogen (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2012; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010) and epidemiologic studies do not find evidence supporting its cancer-promoting effect (Murray, Connett, & Zapawa, 2009; Shields, 2011). Nicotine, however, is not completely harmless. When used alone nicotine can cause damage to cells in arteries and may contribute to some cardiovascular diseases (Heeschen et al., 2001; Morris et al., 2015; Nordskog, Blixt, Morgan, Fields, & Hellmann, 2003). In addition, recent animal studies show nicotine exposure can have an adverse effect on neurodevelopment in fetuses, youths and young adults, which raises safety concerns for young or pregnant users of tobacco products (Bruin, Gerstein, & Holloway, 2010; Slotkin et al., 2015; R. F. Smith, McDonald, Bergstrom, Ehlinger, & Brielmaier, 2015). To conclude, current research finds that nicotine poses some risk to physical health, but for tobacco products the health risk from nicotine is relatively small.

Risk perceptions of tobacco products have been widely researched but only a few studies looked at perceptions of the harm of nicotine per se. In a 2001 survey of a nationally representative sample of smokers, only one third correctly denied that nicotine is a cause of cancer (Bansal, Cummings, Hyland, & Giovino, 2004). People largely believe that nicotine can cause cancer, heart disease, emphysema, high blood pressure, and many more poor health outcomes (Bansal et al., 2004; Hendricks & Brandon, 2008; Mooney, Leventhal, & Hatsukami, 2006; Patel et al., 2013). About half of the daily smokers surveyed in Sweden believed that a large part of harm in smoking comes from nicotine (Wikmans & Ramström, 2010), and a survey of university faculty members showed a third of the participants thought nicotine and cigarettes were of no difference in harming health (Patel et al., 2013).

One possible explanation for the tendency to blame nicotine for cigarette harm is a lack of understanding of the ingredients in cigarettes. Nicotine is the most well-known and the most frequently-mentioned constituent among the 7000 that tobacco products contain (Margolis, Bernat, Keely O’Brien, & Delahanty, 2017). Smokers know cigarette smoke contains chemicals but could not name any of them except for tar and nicotine (Moracco et al., 2016). They also do not know how much nicotine their cigarettes contain (Plantin-Carrenard, Jacob, Foglietti, Derenne, & de Lhomme, 2004).

The necessity to correct nicotine misperceptions was not urgent when nicotine and other combustible compounds were inseparable in tobacco products. In the case of combustible cigarettes for example, nicotine has always been an inseparable part of cigarettes so it does not matter whether smokers would correctly attribute the harm of cigarettes to combustion products or not. As long as nicotine co-existed with combustion products, nicotine misperceptions do not have any behavioral consequence to smokers.

With tobacco products that separate nicotine and tar however, nicotine misperceptions become an issue worth investigating. Both NRT and e-cigarettes deliver nicotine without the combustion products of conventional cigarettes, and the misperceptions of nicotine harm could be consequential to smokers’ use of these nicotine products. On the one hand, for smokers who are trying to quit, belief in exaggerated harm of nicotine could potentially deter them from using NRT as a quitting aid (Bansal et al., 2004; Mooney et al., 2006; S. Y. Smith et al., 2007; Wikmans & Ramström, 2010). On the other hand, the belief in nicotine safety may lead electronic cigarette users to ignore the risk associated with vaping (Choi & Forster, 2013, 2014; Harrell et al., 2015; Wackowski & Delnevo, 2016).

Misperceptions of Nicotine Replacement Therapy

NRT and e-cigarettes are both nicotine delivery systems but public health professionals hold drastically different views on them. NRT has been considered safe and effective by the experts, but e-cigarettes have been evaluated as risky, ineffective, and full of uncertainty.

NRT is a group of quit-smoking medications that reduces withdrawal symptoms by delivering a small amount of nicotine. NRT comes in many forms (e.g. nicotine gums, patches, inhalators, nasal sprays, and lozenges) and they are regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. NRT has been established by the scientific community as effective and safe for smoking cessation (Cahill, Stevens, Perera, & Lancaster, 2013; Nutt et al., 2014; Stead et al., 2012). When used properly NRT can double a smoker’s chance of success at smoking cessation (Silagy, Lancaster, Stead, Mant, & Fowler, 2004).

A few studies have addressed people’s misperceptions about NRT. Regardless of its safety and effectiveness, NRT has been long perceived as a product of high health risk. Depending on sample and question wording, about 20% to 60% of survey participants claim that nicotine patch and gum are as harmful as combustible cigarettes, with cancer and heart disease cited as the potential consequences of long-term use (Bansal et al., 2004; Black, Beard, Brown, Fidler, & West, 2012; Borrelli & Novak, 2007; Harrell et al., 2015; S. Y. Smith et al., 2007; Wikmans & Ramström, 2010).

The relationship between perceived health risks of nicotine and people’s tendency to use NRT is unclear. Some studies found smokers avoided NRT because of their misperceived risk of cancer, and the majority of smokers with misperceptions claimed in a survey that if they received correction information they would be more likely to use NRT (Ferguson et al., 2011). Other studies found nicotine harm perception to be unrelated to smokers’ past use of NRT. Rather NRT use was dependent on smokers’ perceived quitting efficacy (Bansal et al., 2004; Black et al., 2012; Wikmans & Ramström, 2010).

Misperceptions of Electronic Cigarettes

E-cigarettes (also known as e-cigs, vape pens, mods, vaporizers, and others) are electronic devices that vaporize liquid into aerosol for users to inhale. The liquid typically contains nicotine, flavorings, and other chemicals.

The scientific community has not reached any clear-cut consensus about the absolute health effects of e-cigarette use. Experts tend to agree that e-cigarettes are not completely safe (Chun, Moazed, Calfee, Matthay, & Gotts, 2017; Madison et al., 2019), but they disagreed on the level of harm e-cigarette use may impose, especially for long-term use (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018). The relative risk of e-cigarette when compared with combustible cigarette is also under debate. Some scholars believe that e-cigarettes can greatly reduce the harm and should be recommended to smokers to replace combustible cigarettes (e.g. Nutt et al., 2014), while others argue that the harm of e-cigarettes is still unknown and it could be potentially even more harmful than combustible cigarettes so users need to remain cautious (Glantz & Bareham, 2018). A comprehensive review in 2018 concluded that cigarette smokers would improve short-term health conditions only if they could substitute e-cigarettes for combustible cigarettes completely, and the long-term effects remains unknown (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018). Apart from health risks, no confirmed evidence has shown that e-cigarettes can help smokers quit smoking. A meta-analysis even found that smokers who used e-cigarettes were 28% less likely to quit smoking than those who did not rely on e-cigarettes (Kalkhoran & Glantz, 2016). Although there is high level of uncertainty surrounding our understanding of e-cigarettes, current science support the following principles when communicating about e-cigarettes with the general public: never-smokers should be discouraged from e-cigarette use; smokers who are trying to quit should be encouraged to choose NRT over e-cigarettes as the quitting aids; smokers who are not trying to quit should be discouraged from dual use of e-cigarettes and combustible cigarettes.

Unlike NRT, the public’s evaluation of e-cigarettes harm started at a very low level. People tended to incorrectly consider e-cigarettes as safe and effective. They mistakenly believed that compared with NRT, e-cigarettes are less risky, cheaper, healthier, and more effective at reducing cravings (Harrell et al., 2015). A systematic review identified 50 samples from 23 previous studies that assessed people’s risk perception of e-cigarettes relative to combustible cigarettes and found in 70% of the samples the majority of the participants considered e-cigarettes less of a threat to health than regular cigarettes (Czoli, Fong, Mays, & Hammond, 2016). More recent surveys revealed people’s relative risk perception of e-cigarettes have changed over time. The proportion of U.S. adults who perceived e-cigarettes as less harmful than combustible cigarettes declined from about 40–50% in 2012 to about 34% in 2017 (Huang et al., 2019). People’s perception of e-cigarette harm matters because it is associated with future use. A cohort study for example found that young adults who perceived e-cigarettes as less harmful than combustible cigarettes at baseline were more likely to experiment with e-cigarettes in the next year (Choi & Forster, 2014).

To sum up, previous studies suggest that the general public do not understand the comparative health effects of nicotine, NRT, and e-cigarettes, and an educational program will be helpful. The risk perception of nicotine products has been shown to change over time (Huang et al., 2019; Majeed et al., 2017) which makes such perceptions a target for effective interventions (Czoli et al., 2016).

The Reasoned Action Approach

The Reasoned Action approach is used as a theoretical framework to guide the investigation of people’s nicotine misperceptions and their relationship with NRT and e-cigarette use (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2011). Stemming from the early Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1985), the reasoned action approach posits that behavioral intention is the best predictor of behavior. The determinants of people’s behavioral intention include attitudes, norms, and perceived self-efficacy. These three factors are considered to have exclusive determination of intention in the sense that nothing else should influence intention directly. Distal variables, such as personality, emotions, knowledge, and media exposure, are theorized to affect intention indirectly through their effect on attitudes, norms and self-efficacy.

In this study, people’s nicotine harm perception is an assessment of knowledge, and therefore its impact on product use, a behavior, is realized through its influence on more proximal cognitive factors, such as attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy. Although all three factors have been identified as predictors of smoking-related behavior (Godin & Kok, 1996; Trumbo & Harper, 2015), a distal variable like knowledge about nicotine harm has been theorized to be mainly related to only attitude (Etter & Perneger, 2001; Hershberger, Connors, Um, & Cyders, 2018).

Based on the previous research the following research questions are raised:

RQ1. How accurate are perceptions of nicotine harm?

RQ2. Is the perception of nicotine harm a significant behavioral belief associated with NRT attitudes, which in turn affects intention towards NRT use?

RQ3. Is the perception of nicotine harm a significant behavioral belief associated with e-cigarette attitudes, which in turn affects intention towards e-cigarette use?

Study 1 – Nicotine Misperceptions Survey

Method

Sample

A U.S. nationally representative online sample of 371 current cigarette smokers was recruited through the research company SSRS using SSRS Online Probability Panel. Smokers were defined as those who have smoked over 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and were smoking cigarettes every day or on some days at the time of the survey. The sample had a mean age of 46.36 (SD = 15.9). About 55% of the participants were female, 75.2% were white non-Hispanic, 32.3% had finished college, and the median annual household income was $40,000 to $50,000.

Measures

Perception of nicotine harm

Perception of nicotine harm was measured with the question: “In addition to the risk of causing addiction, how much of the health risks in smoking come from the nicotine?” with six options that read “1-None” “2-Very small part” “3- Relatively small part” “4-Relatively large part” “5-Very large part”, and “6-All” (Hamilton et al., 2004; Mooney et al., 2006; Wikmans & Ramström, 2010), M = 3.73, SD = 1.10.

Attitude toward the product

A 5-item semantic differential scale was used to measure smokers’ attitude toward their use of NRT. The scale was led with the statement “My using nicotine replacement products in the next three months would be…”. Items included good-bad, enjoyable-unenjoyable, wise-foolish, pleasant-unpleasant, and beneficial-harmful, with 1 indicating the least favorable attitude and 7 the most favorable, MNRT = 3.65, SDNRT = 1.70. The same semantic differential scale was used to measure attitude toward e-cigarettes with the statement “My using e-cigarettes in the next three months would be”, Mecig = 3.16, SDecig = 1.70. Both attitude scales achieved high reliability with Cronbach’s alpha higher than .87.

Intention to use the product

Participants’ intention to use NRT was measured with a 3-item Likert scale. The three items stated “I intend to buy NRT on a regular basis in the next 3 months,” “I intend to try NRT on a regular basis in the next 3 months” and “I plan to start using NRT on a regular basis in the next 3 months”. The 5-point scale ranged from 1-strongly disagree to 5-strongly agree, M = 2.19, SD= 1.21.

Intention to use e-cigarettes was measured with slightly different items for e-cigarette users and non-users. Non-users of e-cigarettes were asked whether they intend to buy / try / start using e-cigarettes on a regular basis in the next 3 months; current e-cigarette users were asked whether they “intend to continue to vape at my current pace”, “plan to vape more often in the next 3 months”, and “will reduce or stop e-cigarette use in the next 3 months” (reverse coded). The 5-point scale ranged from 1-strongly disagree to 5-strongly agree, M = 2.02, SD = 1.10. All the intention scales achieved high reliability with Cronbach’s alpha higher than .93.

Readiness to quit.

Smokers’ readiness to quit smoking was entered into the analytical model as a covariate. Readiness to quit was measured with the contemplation ladder (Biener & Abrams, 1991). Participants were asked to choose a number that described where they were in thinking about quitting smoking. The numbers ranged from 0 to 10 with five descriptive anchor points: 0-I have no thoughts about quitting smoking, 2-I think I need to consider quitting someday, 5- I think I should quit smoking but I am not quite ready, 8-I am starting to think about how to reduce the number of cigarettes I smoke a day, 10-I am taking action to quit smoking. M = 6.39, SD = 3.

Results

Over half of the smokers in the study mistakenly believed that in addition to causing addiction, nicotine caused a relatively large part (33.2%), very large part (18.1%) or all (5.4%) of health risks in smoking.

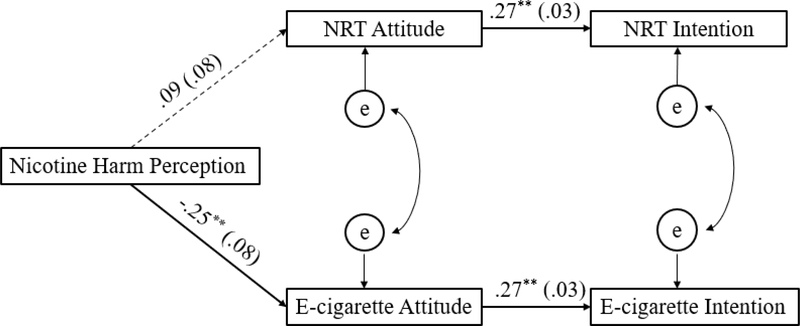

A structural equation model was fitted to test the relationship between nicotine harm perception and smokers’ product attitude and intention. Perceived nicotine harm was entered as the exogenous variable and product attitude and intention were the endogenous variables. The full analytical model controlled for smokers’ age, gender, education level, and their readiness to quit smoking. A simplified model that omits the covariates is depicted in Figure 1. Maximum likelihood was used for model parameter estimation, and the 95% bias corrected confidence intervals of the direct and indirect effects were identified using bootstrapping with 2000 samples.

Figure 1.

Results for the structural equation model. Paths are marked with unstandardized coefficients (standard error). The model controlled for age, gender, education level, and readiness to quit smoking. Non-Normed Fit Index = .99; Comparative Fit Index = .99, root mean square error of approximation = .02; χ2 (4, N=371) = 4.49, p = .34. e = error. ** p < .01.

Although the hypothesized model is overidentified, Chi-square test shows it fits the data as well as the saturated model, χ2 (4, N=371) = 4.49, p = .34. No post-hoc modification was made given the good fit of the data to the model, CFI = .99, TLI = .98, and the RMSEA = .02. A correlation matrix of all the variables is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlations among Nicotine Harm Perception, Product Attitude, and Product Intention.

| NRT Attitude | NRT Intention | E-cig Attitude | E-cig Intention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotine Harm Perception | .05 | −.01 | −.16** | −.16** |

| NRT Attitude | - | .41** | .39** | .13** |

| NRT Intention | - | - | .12** | .24** |

| E-cigarette Attitude | - | - | - | .42** |

Note.

p < .01.

As shown in Figure 1, smokers’ perception of nicotine harm was not associated with an attitude towards NRT use, but it was associated with attitude toward the use of e-cigarettes. The direct and indirect effects of nicotine harm perception on product attitudes and intentions are reported in Table 2. The total effects of nicotine harm perception on NRT attitudes and intentions are both close to zero, suggesting people’s nicotine misperceptions do not influence their attitudes or intentions to use NRT.

Table 2.

Unstandardized Direct, Indirect and Total Effects on Product Attitude and Intention.

| Direct Effect |

Indirect Effect |

Total Effect |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotine harm | NRT Attitude | E-cig Attitude | Nicotine harm | Nicotine Harm | NRT Attitude | E-cig Attitude | |

| NRT Attitude | .09 | - | - | - | .09 | - | - |

| NRT Intention | - | .27** | - | .03 | .03 | .27** | - |

| E-cig Attitude | −.25** | - | - | - | −.25** | - | - |

| E-cig Intention | - | - | .27** | −.07** | −.07** | - | .27** |

Note.

p < .01.

On the other hand, results showed that the more smokers believe that nicotine is harmful, the less favorable is their attitude towards e-cigarettes (B = −.25, p < .001), and the lower intention they have to use e-cigarettes (B = 27, p < .001). As shown in Table 2, a one unit increase in the belief of nicotine harm can result in about a quarter unit decrease in e-cigarette attitude and a 0.07 unit decrease in e-cigarette intention.

Study 1 Implication

Although the majority of the study participants largely overestimated nicotine harm, the nicotine misperceptions survey found nicotine harm was only associated with smokers’ attitude and intention towards e-cigarette use but not their NRT use. The results indicate that nicotine harm perception plays different roles in smokers’ decision to use NRT versus e-cigarettes. Such difference may stem from people’s expected length of use of these two products. NRT as a quitting aid is expected to be used for a short period of time. Thus even though smokers may mistakenly perceive it as cancerous, such misperception could not dissuade them from using NRT (Black et al., 2012). What’s more important for their NRT decision is product safety and its quitting efficacy (Ferguson, Schüz, & Gitchell, 2012). E-cigarettes, on the other hand, has been promoted as a substitute of combustible cigarettes and are meant for long-term use. Thus, smokers’ perception of its harm could affect their intention to use the product.

Nicotine misperception, i.e. the belief that nicotine causes cancer, may not be the main concern of smokers when they made decisions on whether to use NRT, but it could be a factor that prevents them from vaping. Therefor if such misperceptions are corrected, there may not be any increase in NRT use among smokers but rather more use of e-cigarettes.

One major limitation of Study 1 is that it is a cross-sectional survey and thus it is difficult to draw causal claims about the relationships discussed above. It is likely that the causal link between nicotine misperceptions and e-cigarette attitude is actually reversed, or that the relationship is spurious, and thus correcting one’s nicotine misperceptions may lead to no change in e-cigarette attitude and intention at all. In Study 2 we address the issue of causality by designing and experimentally testing the effectiveness of several correction messages.

Another limitation is that all the participants in Study 1 were smokers. Recent trend shows that many cigarette naïve young adults initiate smoking with e-cigarette use (Loukas, Marti, Cooper, Pasch, & Perry, 2018), so it is important to understand how non-tobacco users perceive nicotine harm as well. Given that we found smokers’ attitudes and intentions towards e-cigarettes use were associated with nicotine misperceptions, it is likely that once we correct nicotine misperceptions, we may encourage e-cigarette use for smokers. What is more disturbing however, is the possibility that nicotine misperception correction messages may encourage e-cigarette use among non-smokers. Therefore, in Study 2 both tobacco users and non-users were invited to test the effects of misperception correction messages.

Study 2 – Misperceptions Correction Experiment

If a better understanding of nicotine harm could potentially raise smokers’ intention to use e-cigarettes, are there persuasive strategies we can take to offset such unintended consequences?

Guided by results from Study 1, three textual messages were developed to correct misperceptions of nicotine risk with the hope to further increase NRT use and lower e-cigarette use. When designing the messages, a major consideration was the match of specificity between the message and the outcome behavior.

Attitude and Intention Specificity

It is a common observation that attitudes often fail to predict intentions, or that the actions performed do not always align with stated intentions. The principle of compatibility proposed by Fishbein and others (Ajzen, 1988; Ajzen & Fishbein, 2005; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1974; Fishbein & Jaccard, 1973) offers one possible explanation to account for such attitude-intention, and intention-behavior discrepancies. This tenet posits that, using compatible measures of attitude, intention and behavior, which correspond with one another at the same level of specificity, can maximize the predictive power of attitude and intention.

To put it more concretely, an attitude measure specific to smoking a cigarette in the next six months, is expected to exhibit stronger associations with intentions and behaviors of smoking a cigarette in the next six months, compared to a more global measure of general attitude toward the smoking behavior. On the other hand, general measures of attitude and intentions may predict equally general behaviors well but tend to correlate with specific behaviors poorly. In a meta-analysis examining empirical research on attitude-behavior associations, Kraus (1995) observed an average attitude-behavior correlation of r = .50 when the compatibility principle is followed, compared to r = .14 when the principle is violated. Therefore, the failure to observe attitude-intention or intention-behavior associations in much of the past health behavior change research following the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) approach (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), may be traced in part to the ways in which these constructs are assessed, i.e., whether the specificity of how one construct is measured matches with that of the other construct under investigation.

Measurement specificity is likely to be a significant refinement that can effectively improve applicability and predictive validity of the TRA constructs. If one wishes to change a specific behavior, then focus should be put on changing the corresponding specific attitude or intention. For instance, in order to encourage smokers to use NRT in the next three months, a persuasive message should focus on fostering a more favorable attitude toward using NRT in the next three months. A change in broad attitude or remotely related beliefs, such as nicotine misperceptions, may not result in a corresponding change in the specific behavioral outcome, which is NRT use. Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H1. Product-specific messages would be more effective at changing people’s attitude and intention towards tobacco products than the general knowledge-based message that just corrects nicotine misperceptions.

Method

Sample

A convenience sample was recruited using an online research company, Critical Mix. A stratified sampling strategy was used to recruit equal number of tobacco users and non-tobacco users. Tobacco users were defined as those who had used any tobacco product in the past 30 days. A total of 1008 participants completed the study. The sample had a mean age of 48; 48% were male; 73.3% were white; 12.9% were African American; 17.2% were Hispanic. Among the tobacco users combustible cigarettes were the most used tobacco product (81.2%) followed by e-cigarettes (28%) and cigars (26.4%).

Experiment Design and Stimuli

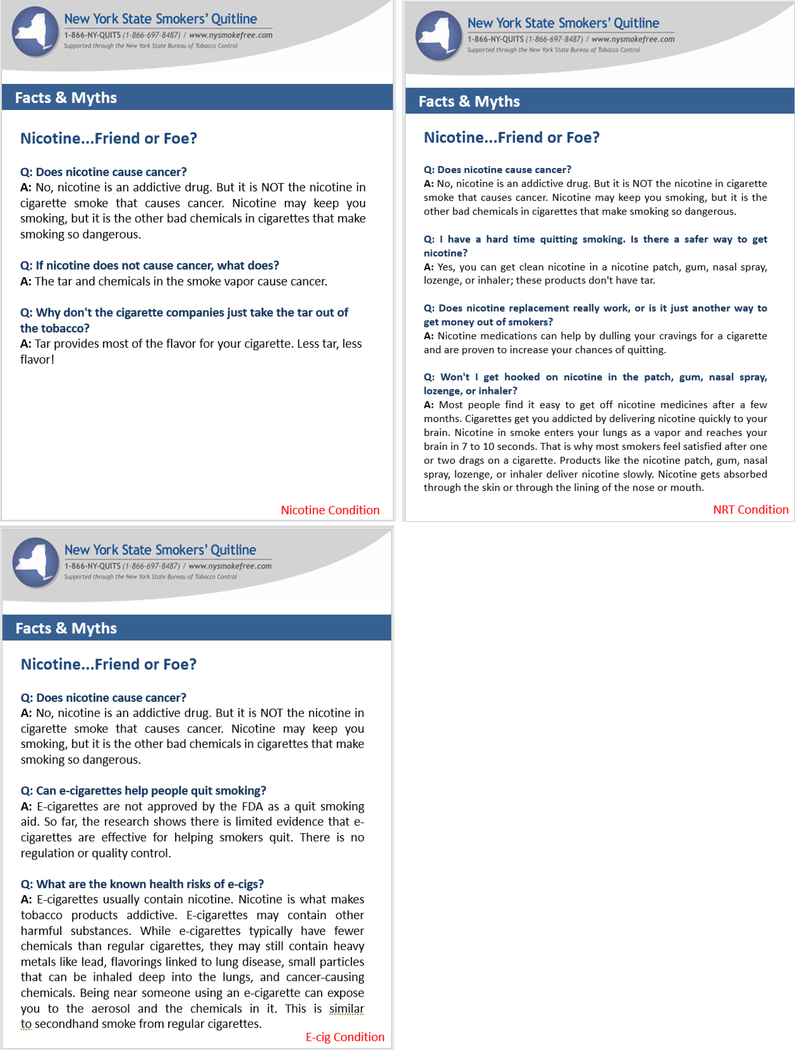

This study adopted a 2 (smoking status: tobacco users or non-users) x 5 (correction messages: no message vs. nicotine vs. NRT vs. e-cigarette vs. reduced nicotine content cigarettes) post-only between-subject design. Study participants were randomly assigned to view one the following five messages: 1) no-message control condition where participants only took the nicotine misperceptions survey; 2) nicotine correction condition where participants viewed a message that only addressed misinformation surrounding nicotine harm; 3) NRT correction condition where participants viewed a message that addressed misinformation concerning both nicotine harm and NRT consequences; 4) e-cigarettes correction condition where participants viewed a message that addressed misinformation surrounding both nicotine harm and e-cigarettes; and 5) reduced nicotine content cigarettes condition where participants viewed a message that addressed misinformation surrounding both nicotine harm and reduced nicotine content cigarettes. Condition 5 is irrelevant to the purpose of the current study and thus is excluded from the analysis.

The correction messages were designed using the Facts and Myths page of New York State Smokers’ Quitline (The New York State Smokers’ Quitline, n.d.) as the basic template. The three correction messages all start with the title ‘Nicotine...Friend or Foe?”, and facts about nicotine and tobacco products were then presented in the format of FAQ. The first Q&A was identical across all three messages where nicotine misperceptions were corrected. The question read “Q: Does nicotine cause cancer?” and the answer read “A: No, nicotine is an addictive drug. But it is NOT the nicotine in cigarette smoke that causes cancer. Nicotine may keep you smoking, but it is the other bad chemicals in cigarettes that make smoking so dangerous.”. The nicotine correction message then went on to further clarify what elements in cigarettes cause cancer, and why the cigarette companies don’t take the tar out. The NRT correction message explained the safety, effectiveness, and addictiveness of NRT. The e-cigarette correction message addressed whether e-cigarettes could help people quit smoking and their known risks at the time of the experiment. The answers provided in the Q&A were all extracted from official websites of public health agencies, including CDC, FDA, Smokefree.gov, and nysmokefree.com. Figure 2 shows the correction messages for the three treatment conditions.

Figure 2.

Correction messages for the three treatment conditions.

Measures

After message exposure participants in Study 2 took the Nicotine Misperceptions Survey that were used in Study 1. Their perception of nicotine harm, and their attitude and intention towards using NRT and e-cigarettes were all measured with the same questions as Study 1.

Results

A multivariate ANOVA was first performed to examine the overall effects of correction messages and its interaction with smoking status on nicotine harm perception, NRT attitude, NRT intention, e-cigarette attitude, and e-cigarette intention. Results indicated a significant overall effect of correction messages, Wilks’ Λ = .86, multivariate F(5, 2170) = 7.94, p < .001, a significant overall effect of smoking status, Wilks’ Λ = .64, multivariate F(5, 786) = 90.35, p < .001, but an insignificant overall interaction effect of message and smoking status, Wilks’ Λ = .99, multivariate F(15, 2170) = 0.5, p = .94. A series of univariate analyses with planned contrasts were then conducted to detect the effect of correction messages on each of the five outcomes. The ANOVA results are summarized in Table 3. The means of people’s nicotine harm perception, NRT attitude, NRT intention, e-cigarette attitude, and e-cigarette intention are compared in Table 4.

Table 3.

Results from ANOVAs of Nicotine Harm Perception, NRT Attitude, NRT Intention, E-Cig Attitude, and E-Cig Intention by Message Type and Smoking Status

| Nicotine Harm Perception |

E-cig Atitude |

E-cig Intention |

NRT Attitude |

NRT Intention |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | df | F | η2 | df | F | η2 | df | F | η2 | df | F | η2 | df | F | η2 |

| Message Type (M) | 3 | 32.84** | .11 | 2 | 3.22* | .01 | 2 | 2.59† | .01 | 2 | .90 | .00 | 2 | 2.2 | .01 |

| Smoking Status (S) | 1 | 4.49* | .03 | 1 | 209.17** | .26 | 1 | 145.79** | .20 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| M*S | 3 | .25 | .00 | 2 | .53 | .00 | 2 | 1.25 | .00 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Adjusted R2 | .11 | .26 | .20 | .00 | .01 | ||||||||||

| n | 805 | 599 | 602 | 308 | 305 | ||||||||||

Note.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01.

Table 4.

Means (SD) of Nicotine Harm Perception, NRT Attitude, NRT Intention, E-Cigarette Attitude, and E-Cigarette Intention by Correction Message Type and Smoking Status

| Nicotine Harm Perception | E-Cig Attitude | E-Cig Intention | NRT Attitude | NRT Intention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco User | |||||

| No message | 3.99 (1.30) | 4.20 (1.83) | 2.80 (1.25) | 4.65 (1.58) | 2.92 (1.31) |

| Nicotine correction | 2.82a (1.71) | 4.09 (1.89) | 2.65 (1.34) | 4.47 (1.64) | 2.68 (1.19) |

| E-cigarette correction | 2.97a (1.67) | 3.65a (1.86) | 2.37a (1.28) | - | - |

| NRT correction | 2.77a (1.64) | - | - | 4.77 (1.66) | 3.04 (1.28) |

| Non-Tobacco User | |||||

| No message | 4.37 (1.24) | 2.01 (1.47) | 1.50 (1.01) | - | - |

| Nicotine correction | 3.04a (1.68) | 2.10 (1.70) | 1.53 (0.99) | - | - |

| E-cigarette correction | 3.18a (1.61) | 1.80 (1.38) | 1.43 (0.85) | - | - |

| NRT correction | 2.89a (1.60) | - | - | - | - |

Note.

This mean is significantly different from the mean of the no-message control condition in the same column.

p < .05

p < .01.

A two-way ANOVA was performed to determine the influence of correction messages on perceptions of nicotine harm. The first factor had four levels indicating correction message type (none, nicotine, NRT, e-cigarette), and the second factor had two levels representing smoking status (tobacco users, non-tobacco-users). As shown in table 3, people receiving different correction messages perceived significantly different levels of nicotine harm, F(3, 797) = 32.84, p < .001, partial η2 = .11. Post-hoc analysis with planned contrast revealed that all three correction messages successfully lowered subjects’ estimation of nicotine harm. The main effect of smoking status was also significant, with tobacco users reporting lower nicotine harm than non-users, F (1, 797) = 4.49, p < .05, partial η2 = .006. The interaction term was insignificant.

Two-way ANOVAs were performed to determine the influence of correction messages on people’s attitude and intention toward e-cigarettes use. The first factor had three levels indicating correction message type (none, nicotine, e-cigarette), and the second factor had two levels representing smoking status (tobacco users, non-tobacco-users). As shown in Table 3, for e-cigarette attitude two-way ANOVA showed a significant main effect of the correction messages, F(2, 593) = 3.22, p < .05, partial η2 = .011, and a significant main effect of smoking status, F(1, 593) = 209.17, p < .001, partial η2 = .26, while the interaction effect was not significant. Planned contrast showed that tobacco users who viewed the e-cigarette correction message (M = 3.65, SD = 1.86) held a significantly less favorable attitude toward towards e-cigarette use than the no-message control group (M = 4.20, SD = 1.83). The nicotine correction message did not affect people’s e-cigarette attitude (M = 4.09, SD = 1.89). Similarly, for e-cigarette intention ANOVA revealed a marginally significant main effect of the correction messages, F(2, 596) = 2.59, p = .08, partial η2 = .01, a significant main effect of smoking status, F(1, 596) = 145.79, p < .001, partial η2 = .20, and an insignificant interaction. Planned contrast showed that the e-cigarette correction message lowered people’s intention to use e-cigarettes, but the nicotine correction message had no such effect (See Table 4 for details).

Given that non-tobacco users’ interest in NRT would be extremely low (Gerlach, Rohay, Gitchell, & Shiffman, 2008), the analyses for NRT attitude and intention were performed only on tobacco users. One-way ANOVA was conducted to compare tobacco users’ attitude and intention toward NRT use after their exposure to the correction messages. As shown in Table 3 and Table 4, neither the nicotine correction message nor the NRT correction message changed tobacco users’ attitude or intention towards NRT use.

Study 2 Implication

Three correction messages were tested. The nicotine correction message was deliberately designed to be a general message aiming only at correcting knowledge. This message addressed nicotine harm per se by clarifying that nicotine was not a carcinogen and not the main cause of disease in cigarettes. The nicotine correction message achieved success at correcting misperceptions of nicotine harm, in the sense that it made readers perceive much lower health risks in nicotine, but it had no effect on attitudes or intentions toward tobacco product use.

The NRT correction message and the e-cigarette correction message were designed to be specific messages aiming at changing behaviors related to tobacco product use. The NRT correction failed to change NRT attitudes or behavioral intentions, but the e-cigarette correction message significantly influenced e-cigarette attitudes and intentions.

Discussion

Nicotine replacement therapy and electronic cigarettes are both tobacco products that contain mainly nicotine, and yet health professionals (especially those in the U.S.) have drastically different views on them. NRT has been recommended to smokers as an FDA-approved and safe quitting tool while the safety and efficacy of e-cigarettes are still under debate.

Study 1 revealed an interesting dilemma regarding the correction of nicotine misperceptions. Survey in Study 1 shows that smokers’ belief in nicotine harm is not associated with their NRT attitude and intention, but it is associated with their e-cigarette attitude and intention. Thus correcting nicotine misperceptions may not lead to a result that would benefit public health. If we could successfully correct nicotine misperceptions and make everyone understand that nicotine by itself does not cause cancer, we may not see an increase in NRT use, but we may see an increase in e-cigarette use.

Correcting Misperception

The consequence of correcting nicotine misperception was directly tested in Study 2 in which a nicotine correction message was compared with a no-message control. The nicotine correction message developed in this study was effective at modifying perceptions of nicotine harm, but the message was not strong enough to affect product attitude and intention, not to mention behavior.

What is the value of the nicotine correction message then? Some may argue that the public deserves the truth, and it is always important that people have the most accurate knowledge so they can make informed decisions. Regarding nicotine misperceptions, if the goal of a public education program is only to inform the public and correct misperceptions, the nicotine correction message developed and tested in Study 2 would serve the educational purpose perfectly: it is strong enough to correct misinformation and lower people’s nicotine harm perception but at the same time it did not promote e-cigarette use. The concern raised in Study 1, i.e. e-cigarette use may increase if we could successfully correct nicotine misperception, can be assuaged.

Many public health campaigns, however, have goals beyond informing and educating. It would be ideal if a health message could correct misinformation and at the same time change attitudes and intentions, and eventually, behavior. Informed by the Reasoned Action approach we further designed and tested two correction messages geared towards the use of two specific tobacco products. Results showed the NRT correction message failed at promoting subjects’ attitudes and intentions towards NRT use, but the e-cigarette correction message lowered favorable attitudes and intentions to use e-cigarettes.

Changing Attitude and Intention

The lack of effect of the NRT correction message is slightly surprising. Given that Study 1 showed the fear of nicotine harm did not prevent tobacco users from NRT use, the NRT correction message was designed to discuss issues beyond nicotine harm. It addressed issues that were identified by previous research as factors associated with smokers’ NRT refusal, such as product safety (e.g. “clean nicotine…don’t have tar”), its effectiveness in helping smokers quit smoking (e.g. “…are proven to increase your chances of quitting”), and its addictiveness (e.g. “Most people find it easy to get off nicotine medicines after a few months”). The NRT correction message moved the participants’ attitude and intention towards the right direction, but the effect size was too small to be detected.

It is unclear why NRT correction message failed to affect NRT attitude and intention. Potential explanations are: 1) the message was not persuasive enough, especially the section where NRT’s effectiveness in helping smokers quit was described; 2) many tobacco users have formed strong beliefs about NRT from past experience and thus it is unlikely to persuade them using just one textual message; 3) there are other unknown reasons why tobacco users do not use NRT, and more research is in need to identify these reasons.

The e-cigarette correction message developed and tested in this study achieved both the purpose of correcting nicotine misperceptions and the goal to change people’s attitudes and intention toward e-cigarette use. By adding the Q&A that directly addresses uncertainties surrounding e-cigarette’s efficacy as a quitting tool and its health risks, our e-cigarette message reversed the gloomy predictions made by Study 1 and lowered people’s likelihood of using e-cigarettes. Tobacco users and non-users did not differ in their responses to the correction messages, which means the e-cigarette message prevented both product switching for tobacco users and e-cigarette initiation for the never-smokers.

To sum, across the three messages, the e-cigarette correction message achieved the best persuasive effects. It corrected nicotine misperceptions and could potentially lower e-cigarette use.

Communicating about Uncertainty

A major difficulty for public health communication in the age of information explosion is how to communicate uncertainty when scientific evidence is still emerging. Here are a few examples of health topics that caused great confusion among the general public: Can we eat eggs as much as we want since the latest dietary guidelines removed the limit on cholesterol intake and research on the health consequences of egg intake is inconclusive? Should all women delay routine screening for breast cancer as the recommended age for mammogram screening was raised from 40 to 50? Can smokers quit smoking by switching to electronic cigarettes? Today’s communication scholars face such difficult questions more often than ever with the fast development in science and technology. We can tell the public that the scientific community has not reached a conclusion, but such communications do not help people make decisions about their own behaviors.

In the e-cigarette message we dealt with the issue of uncertainty proactively. The two e-cigarette questions presented in the Q&A (“Can e-cigarettes help people quit smoking?” “What are the known health risks of e-cigs?”) were the ones that both the scientific community and the general public don’t have a clear answer to. In the answer section then, we provided readers with scientifically accurate information with some reservation. (e.g. “So far, the research shows there is limited evidence that e-cigarettes are effective for helping smokers quit”, “they may still contain heavy metals like lead, flavorings linked to lung disease, small particles that can be inhaled deep into the lungs, and cancer-causing chemicals). The message is two-sided, in the sense that it addresses both the benefits (e.g. “have fewer chemicals than regular cigarettes”) and the harm, but it is not balanced, as harm was discussed more extensively than the benefit. Perhaps that’s why this particular message turned out to be effective.

The strategies adopted in message development in this study shed some light on the issue of how to communicate uncertainty on health topics where even the experts don’t have a consistent recommendation. Instead of telling the public we still don’t know and more research is needed, communication material could consider presenting scientifically accurate information that represent both the pros and the cons of the health behavior in question, so that the audience can make an informed decision. This two-sided message does not have to be a balanced message. One side could outweigh the other when there is a slightly preferred position.

Limitation

The results of these two studies should be interpreted with an understanding of the following limitations.

Nicotine harm perception was measured with only one item (“In addition to the risk of causing addiction, how much of the health risks in smoking come from the nicotine?”) and thus there is no evaluation of its reliability. Since addiction is clearly a health risk, the clause “In addition to the risk of causing addiction” was used for the purpose of clarity, but this clause may also prime respondents to think there are risks other than addiction associated with nicotine.

As an exploratory study, in Study 2 the experiment only three messages were tested and no effort was made to avoid case-category confound. The effects reported in this study may be unique to these three specific messages in their specific format and delivery mode. It is possible, for example, that discussing e-cigarette risks using other textual or imagery content may not change people’s attitude and intention. FAQ was the only message format tested, text was the only delivery mode, and government agency website the only media platform. Therefore, the study result may lack generalizability.

Although statistical significance was achieved in multiple analyses, the effect sizes are generally very small, especially in Study 2. The correction messages contributed to 11% of the variance in perceptions of nicotine harm, but only 1% in e-cigarette attitude and intention, showing it is relatively easy to correct knowledge but difficult to change attitudes and behavior. Future research should aim at developing persuasive message with stronger effects.

Acknowledgment

Research reported in this presentation was supported by grant number P50CA180523 from the National Cancer Institute and FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) awarded to the University of Maryland. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

Reference

- Ajzen I (1985). From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Kuhl J & Beckmann J (Eds.), Action Control (pp. 11–39). Springer Berlin; Heidelberg. 10.1007/978-3-642-69746-3_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I (1988). Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, & Fishbein M (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, & Fishbein M (2005). The influence of attitudes on behavior. In Albarracín D, Johnson BT, & Zanna MP (Eds.), The handbook of attitudes (pp. 173–221). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal MA, Cummings KM, Hyland A, & Giovino GA (2004). Stop-smoking medications: Who uses them, who misuses them, and who is misinformed about them? Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 6 Suppl 3, S303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biener L, & Abrams DB (1991). The Contemplation Ladder: Validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychology, 10(5), 360–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black A, Beard E, Brown J, Fidler J, & West R (2012). Beliefs about the harms of long-term use of nicotine replacement therapy: Perceptions of smokers in England. Addiction, 107(11), 2037–2042. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03955.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli B, & Novak SP (2007). Nurses’ knowledge about the risk of light cigarettes and other tobacco “harm reduction” strategies. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 9(6), 653–661. 10.1080/14622200701365202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruin JE, Gerstein HC, & Holloway AC (2010). Long-Term Consequences of Fetal and Neonatal Nicotine Exposure: A Critical Review. Toxicological Sciences, 116(2), 364–374. 10.1093/toxsci/kfq103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, & Lancaster T (2013). Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: An overview and network meta-analysis. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009329.pub2/abstract

- Choi K, & Forster J (2013). Characteristics associated with awareness, perceptions, and use of electronic nicotine delivery systems among young US Midwestern adults. American Journal of Public Health, 103(3), 556–561. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, & Forster JL (2014). Beliefs and Experimentation with Electronic Cigarettes: A Prospective Analysis Among Young Adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 46(2), 175–178. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun LF, Moazed F, Calfee CS, Matthay MA, & Gotts JE (2017). Pulmonary toxicity of e-cigarettes. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology, 313(2), L193–L206. 10.1152/ajplung.00071.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czoli CD, Fong GT, Mays D, & Hammond D (2016). How do consumers perceive differences in risk across nicotine products? A review of relative risk perceptions across smokeless tobacco, e-cigarettes, nicotine replacement therapy and combustible cigarettes. Tobacco Control, tobaccocontrol-2016–053060. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter JF, & Perneger TV (2001). Attitudes toward nicotine replacement therapy in smokers and ex-smokers in the general public. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 69(3), 175–183. 10.1067/mcp.2001.113722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SG, Gitchell JG, Shiffman S, Sembower MA, Rohay JM, & Allen J (2011). Providing accurate safety information may increase a smoker’s willingness to use nicotine replacement therapy as part of a quit attempt. Addictive Behaviors, 36(7), 713–716. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SG, Schüz B, & Gitchell JG (2012). Use of smoking cessation aids: Role of perceived safety and efficacy. Journal of Smoking Cessation, 7(1), 1–3. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.rowan.edu/10.1017/jsc.2012.1122936953 [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, & Ajzen I (1974). Attitudes towards objects as predictors of single and multiple behavioral criteria. Psychological Review, 81(1), 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, & Ajzen I (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, & Ajzen I (2011). Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, & Jaccard J (1973). Theoretical and methodological considerations in the prediction of family planning intentions and behavior. Representative Research in Social Psychology, 4, 37–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach KK, Rohay JM, Gitchell JG, & Shiffman S (2008). Use of nicotine replacement therapy among never smokers in the 1999–2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 98(1–2), 154–158. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz SA, & Bareham DW (2018). E-Cigarettes: Use, Effects on Smoking, Risks, and Policy Implications. Annual Review of Public Health, 39(1), 215–235. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin G, & Kok G (1996). The Theory of Planned Behavior: A Review of its Applications to Health-Related Behaviors. American Journal of Health Promotion, 11(2), 87–98. 10.4278/0890-1171-11.2.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton WL, Norton G, Ouellette TK, Rhodes WM, Kling R, & Connolly GN (2004). Smokers’ responses to advertisements for regular and light cigarettes and potential reduced-exposure tobacco products. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 6 Suppl 3, S353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell PT, Marquinez NS, Correa JB, Meltzer LR, Unrod M, Sutton SK, Simmons VN, & Brandon TH (2015). Expectancies for Cigarettes, E-Cigarettes, and Nicotine Replacement Therapies Among E-Cigarette Users (aka Vapers). Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 17(2), 193–200. 10.1093/ntr/ntu149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeschen C, Jang JJ, Weis M, Pathak A, Kaji S, Hu RS, Tsao PS, Johnson FL, & Cooke JP (2001). Nicotine stimulates angiogenesis and promotes tumor growth and atherosclerosis. Nature Medicine, 7(7), 833–839. 10.1038/89961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks PS, & Brandon TH (2008). Smokers’ expectancies for smoking versus nicotine. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 22(1), 135–140. 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger A, Connors M, Um M, & Cyders MA (2018). The Theory of Planned Behavior and E-cig Use: Impulsive Personality, E-cig Attitudes, and E-cig Use. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 16(2), 366–376. 10.1007/s11469-017-9783-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Feng B, Weaver SR, Pechacek TF, Slovic P, & Eriksen MP (2019). Changing Perceptions of Harm of e-Cigarette vs Cigarette Use Among Adults in 2 US National Surveys From 2012 to 2017. JAMA Network Open, 2(3). 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. (2012). Tobacco Smoking. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, 100E, 43–211. [Google Scholar]

- Kalkhoran S, & Glantz SA (2016). E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 4(2), 116–128. 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00521-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus SJ (1995). Attitudes and the prediction of behavior: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 58–75. [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A, Marti CN, Cooper M, Pasch KE, & Perry CL (2018). Exclusive e-cigarette use predicts cigarette initiation among college students. Addictive Behaviors, 76, 343–347. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison MC, Landers CT, Gu B-H, Chang C-Y, Tung H-Y, You R, Hong MJ, Baghaei N, Song L-Z, Porter P, Putluri N, Salas R, Gilbert BE, Levental I, Campen MJ, Corry DB, & Kheradmand F (2019). Electronic cigarettes disrupt lung lipid homeostasis and innate immunity independent of nicotine. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 129(10), 4290–4304. 10.1172/JCI128531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majeed BA, Weaver SR, Gregory KR, Whitney CF, Slovic P, Pechacek TF, & Eriksen MP (2017). Changing Perceptions of Harm of E-Cigarettes Among U.S. Adults, 2012–2015. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 52(3), 331–338. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.08.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis KA, Bernat JK, Keely O’Brien E, & Delahanty JC (2017). Online Information About Harmful Tobacco Constituents: A Content Analysis. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19(10), 1209–1215. 10.1093/ntr/ntw220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney ME, Leventhal AM, & Hatsukami DK (2006). Attitudes and Knowledge About Nicotine and Nicotine Replacement Therapy. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 8(3), 435–446. 10.1080/14622200600670397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moracco KE, Morgan JC, Mendel J, Teal R, Noar SM, Ribisl KM, Hall MG, & Brewer NT (2016). “My First Thought was Croutons”: Perceptions of Cigarettes and Cigarette Smoke Constituents Among Adult Smokers and Nonsmokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 18(7), 1566–1574. 10.1093/ntr/ntv281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris PB, Ference BA, Jahangir E, Feldman DN, Ryan JJ, Bahrami H, El-Chami MF, Bhakta S, Winchester DE, Al-Mallah MH, Sanchez Shields M, Deedwania P, Mehta LS, Phan BAP, & Benowitz NL (2015). Cardiovascular Effects of Exposure to Cigarette Smoke and Electronic Cigarettes: Clinical Perspectives From the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Section Leadership Council and Early Career Councils of the American College of Cardiology. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 66(12), 1378–1391. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray RP, Connett JE, & Zapawa LM (2009). Does nicotine replacement therapy cause cancer? Evidence from the Lung Health Study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 11(9), 1076–1082. 10.1093/ntr/ntp104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordskog BK, Blixt AD, Morgan WT, Fields WR, & Hellmann GM (2003). Matrix-degrading and pro-inflammatory changes in human vascular endothelial cells exposed to cigarette smoke condensate. Cardiovascular Toxicology, 3(2), 101–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutt DJ, Phillips LD, Balfour D, Curran HV, Dockrell M, Foulds J, Fagerstrom K, Letlape K, Milton A, Polosa R, Ramsey J, & Sweanor D (2014). Estimating the harms of nicotine-containing products using the MCDA approach. European Addiction Research, 20(5), 218–225. 10.1159/000360220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacek LR, Rass O, & Johnson MW (2017). Knowledge about nicotine among HIV-positive smokers: Implications for tobacco regulatory science policy. Addictive Behaviors, 65, 81–86. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel D, Peiper N, & Rodu B (2013). Perceptions of the health risks related to cigarettes and nicotine among university faculty. Addiction Research & Theory, 21(2), 154–159. 10.3109/16066359.2012.703268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plantin-Carrenard E, Jacob N, Foglietti MJ, Derenne JP, & de Lhomme G (2004). [What perception have smokers of nicotine and tar yields of cigarettes?]. Revue Des Maladies Respiratoires, 21(1), 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College Physicians. (2016). Nicotine without smoke: Tobacco harm reduction. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/nicotine-without-smoke-tobacco-harm-reduction-0

- Shields PG (2011). Long-term Nicotine Replacement Therapy: Cancer Risk in Context. Cancer Prevention Research, 4(11), 1719–1723. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silagy C, Lancaster T, Stead LF, Mant D, & Fowler G (2004). Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3. 10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Skavicus S, Card J, Stadler A, Levin ED, & Seidler FJ (2015). Developmental Neurotoxicity of Tobacco Smoke Directed Toward Cholinergic and Serotonergic Systems: More than Just Nicotine. Toxicological Sciences, 147(1), 178–189. 10.1093/toxsci/kfv123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RF, McDonald CG, Bergstrom HC, Ehlinger DG, & Brielmaier JM (2015). Adolescent nicotine induces persisting changes in development of neural connectivity. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 55, 432–443. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SY, Curbow B, & Stillman FA (2007). Harm perception of nicotine products in college freshmen. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 9(9), 977–982. 10.1080/14622200701540796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stead LF, Perera R, Bullen C, Mant D, Hartmann-Boyce J, Cahill K, & Lancaster T (2012). Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11, CD000146. 10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan ASL, Lee C, & Chae J (2015). Exposure to Health (Mis)Information: Lagged Effects on Young Adults’ Health Behaviors and Potential Pathways. Journal of Communication, 65(4), 674–698. 10.1111/jcom.12163 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The New York State Smokers’ Quitline. (n.d.). Nicotine...Friend or Foe. https://www.nysmokefree.com/FactsAndFAQs/NicotineFacts

- Trumbo CW, & Harper R (2015). Orientation of US Young Adults toward E-cigarettes and their Use in Public. Health Behavior Policy Review, 2(2), 163–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2010). How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Wackowski OA, & Delnevo CD (2016). Young Adults’ Risk Perceptions of Various Tobacco Products Relative to Cigarettes Results From the National Young Adult Health Survey. Health Education & Behavior, 43(3), 328–336. 10.1177/1090198115599988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikmans T, & Ramström L (2010). Harm perception among Swedish daily smokers regarding nicotine, NRT-products and Swedish Snus. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 8(1), 9. 10.1186/1617-9625-8-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson N, Peace J, Edwards R, & Weerasekera D (2011). Smokers commonly misperceive that nicotine is a major carcinogen: National survey data. Thorax, 66(4), 353–354. 10.1136/thx.2010.141762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]