Abstract

People living with HIV are at higher risk of atherosclerosis (AS). The pathogenesis of this risk is not fully understood. To assess the regulatory networks involved in AS we sequenced mRNA of the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and measured cytokine and chemokine levels in the plasma of 13 persons living with HIV and 12 matched HIV-negative persons with and without AS. microRNAs (miRNAs) are known to play a role in HIV infection and may modulate gene regulation to drive AS. Hence, we further assessed miRNA expression in PBMCs of a subset of 12 HIV+ people with and without atherosclerosis. We identified 12 miRNAs differentially expressed between HIV+ AS+ and HIV+ , and validated 5 of those by RT-qPCR. While a few of these miRNAs have been implicated in HIV and atherosclerosis, others are novel. Integrating miRNA measurements with mRNA, we identified 27 target genes including SLC4A7, a critical sodium and bicarbonate transporter, that are potentially dysregulated during atherosclerosis. Additionally, we uncovered that levels of plasma cytokines were associated with transcription factor activity and miRNA expression in PBMCs. For example, BACH2 activity was associated with IL-1β, IL-15, and MIP-1α. IP10 and TNFα levels were associated with miR-124-3p. Finally, integration of all data types into a single network revealed increased importance of miRNAs in network regulation of the HIV+ group in contrast with increased importance of cytokines in the HIV+ AS+ group.

Subject terms: Gene regulation, miRNAs, Network topology, HIV infections, Atherosclerosis

Introduction

Studies of human immunology highlighting variability across individuals have revealed that variation in functional responses is largely determined by non-heritable factors, most likely by environmental exposures1–3. Viral infections such as human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV) interfere with cellular targets and cause derangement of the immune response. Combination anti-retroviral therapy (cART) has rendered HIV infection as a chronic manageable disease. However, persons living with HIV remain at increased risk of co-morbidities despite cART; the most frequent of these is cardiovascular disease (CVD) driven by atherosclerosis (AS)4–6. It is likely that cART and HIV itself play a role in AS7. This observation was also reported in a study that assessed carotid artery thickening, a marker of AS, which was up to 24% higher in persons living with HIV compared with uninfected sex- and age-matched persons, and was comparable in cART-naïve persons and with virologic suppression on cART8. Moreover, a large retrospective analysis indicates that HIV infection status independently confers an odds ratio for acute myocardial infarction of ~ 1.93 (95% CI, 1.21–2.93) after adjusting for traditional risk factors such as age and hypertension9. Other more recent studies also support this observation9–11. Thus, persons living with HIV are at higher risk of AS even with ongoing cART therapy8,12,13. Moreover, elevated AS prevalence in HIV-1 elite controllers indicates that inflammation can be induced by the presence of HIV infection14.

AS is triggered by a pro-thrombotic inflammatory environment that attracts platelets and monocytes to injured endothelial cells. As monocytes migrate into the vessel wall, they differentiate into macrophages. Macrophages exert their phagocytic activity, engulfing lipids, and forming the characteristic foam cells. These cells release further chemoattractant molecules, maintaining a process that leads to plaque formation15. Several molecular mechanisms induced by HIV infection and cART therapy lead to persistent inflammation and contribute to development of AS16–19. Treatment with cART is associated with increased cholesterol levels, a risk factor for AS20. HIV infection itself leads to higher levels of oxidized low density lipoprotein (LDL)21 which increases endothelial expression of monocyte and T cell adhesion markers22. Oxidized LDL, cholesterol crystals, and HIV infection itself activate the macrophage/monocyte inflammasome, which drives inflammation through activation of cytokines such as IL-18 and IL-1β23,24.

Cytokines and other soluble secreted signaling molecules, such as chemokines, regulate inter- and intra-cellular signaling, thus driving pathogenesis of HIV or AS. A handful of such interactions are known: for example, IL-21 promotes STAT3-mediated expression of miR-29 which in turn disinhibits antiviral gene expression and resistance to HIV infection in CD4+ T-cells25. Stimulation of macrophages with a combination of IFN-γ and mildly-oxidized LDL induces miR-155 expression and results in higher levels of the MCP-1/CCL2 chemokine and further promotes inflammation through inhibition of the transcription factor BCL626. However, cytokine-miRNA-mRNA networks in persons with HIV who also have atherosclerosis have yet to be fully characterized. Thus, further study of cytokines together with miRNA is warranted to understand the interaction between HIV and atherosclerosis.

Micro-RNAs (miRNAs or miRs) may be a major factor in the complex pathophysiology of AS27–29. miRNAs are short non-coding ribonucleotide molecules, typically 22 nt, that serve as critical regulators of gene expression across nearly all life stages and tissues. miRNA dysregulation has been linked to AS through effects on cholesterol metabolism, lipid uptake by macrophages, inflammation, and angiogenesis30–32. A number of miRNAs have been suggested as potential therapeutic targets and biomarkers for AS, as well as other diseases and environmental exposures33–36. Such miRNAs include miR-126-5p which has been shown to enhance the response of monocytes to lipopolysaccharide stimulation when levels are altered in persons with HIV infection37, miR-132 which is associated with CD4 + T-cell activation and increased HIV replication38, and let-7c, miR-34a, and miR-124a which modulate innate immune activity39, among others40–43. Of the miRNAs with altered expression in HIV infection, some have been studied as putative biomarkers of AS in HIV infection or have been previously associated with AS, including miR-210, miR-7, and miR-33144, miR-155 and miR-22345, miR-125a-5p and miR-139-5p46, miR-13247, and miR-126, miR-145, and let-7c43. How miRNAs are dysregulated in AS and chronic HIV infection, and the targets they modulate to act as effectors of inflammation in those contexts remains unclear.

Given the complex roles of miRNAs, cytokines, and signaling events, here we aim to use systems-level approaches to investigate dysregulated networks involved in development of AS in people living with HIV. Though atherosclerosis itself is a tissue-specific pathogenesis, chronic, systemic inflammation (which is a hallmark of HIV infection) is one of the major drivers of AS progression48,49. In that regard, PBMCs provide insights into systems-level changes and are frequently used as a proxy to investigate tissue- and organ-specific modulations50. Specific to HIV infection, various components of anti-retroviral therapy and viral proteins exert inflammatory/activatory effects on monocytes/macrophages as shown by our group7 and others (reviewed in51), which are important cellular mediators of AS progression52,53. Further, miRNAs are often released into the blood in stable protein complexes or exosomes and have been implicated in patho-mechanisms of AS54. They can be potentially used to develop diagnostic tests and, in that respect, it is important that the acquisition of blood is low risk to individuals. To this end, we collected blood samples from 13 persons living with HIV and 12 uninfected persons, with and without AS. The collected blood was used to obtain multiple measurements of immune phenotypes including mRNA expression and soluble cytokine and chemokine abundance in all 25 subjects, in addition to miRNA expression in the subjects living with HIV. We find regulatory modes driven by cytokines and miRNAs play differential roles in HIV+ and HIV+ AS+ .

Methods

Participant cohort summary, sample collection, and storage

13 persons living with HIV and ≥ 50 years of age on stable cART for at least 1 year and with viral load ≤ 50 copies/mL were recruited. 12 HIV-negative persons matched for age, gender, environment and Reynolds CVD risk score were also recruited. The details of HIV treatment are available in Supplemental Table 1. All methods were carried out in accordance with University of Rochester guidelines and regulations, and all experimental and study protocols were approved by the University of Rochester Institutional Review Board (#RSRB00063845). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Individuals were assigned AS+ if they had carotid plaques on both sides, and AS− if they did not have carotid plaques. 30 mLs of blood per study participant was collected in ACD vacutainers and was processed within 2–3 h of collection. Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) were isolated using Ficoll density gradient centrifugation. Five mLs of plasma was stored at -80ºC and 5 million PBMCs were preserved using RNAlater (Thermo Fisher). De-identified subject information is available in Supplemental Table 1.

Levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators in peripheral blood plasma

A 29-Plex Milliplex Human Cytokine/Chemokine panel kit (Millipore Cat# HCYTMAG-60K-PX29) was used to quantitate the cytokine and chemokine levels using Luminex magnetic microbead array technology. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, plasma specimens were thawed on ice and micro-centrifuged for 5 min at 15,000 RCF at 4 °C to remove any particulate matter. 25 µLs of reference standard dilutions, control, and test specimens were incubated overnight at 4 °C with shaking at 800 RPM in duplicate wells on a 96 well plate with 25 µLs of either assay buffer for specimens or plasma matrix for standards and controls and 25 µLs of microbead solution. Wells were washed 3 times with wash buffer on an automated magnetic plate washer (Bio-Rad Bio-Plex ProII) and 25 µLs of biotinylated detection antibodies were added for 1 h at room temperature (RT) with shaking. 25 µLs of Streptavidin–Phycoerythrin was then added per well and incubated for 30 min at RT before washing the plate 3 times. Finally, 150 µLs of phosphate-buffered saline at pH 7.2 was added per well and mixed prior to reading on a Luminex 200 instrument. Control 1 and Control 2 values for all analytes fell within the kit quality control ranges for the kit lot per the standard reference curve (range 3.2 pg/mL to 2000 pg/mL), confirming acceptable performance of the kit. The trimmed means of the fluorescence intensities across the beads for a given sample and target were exported from the Luminex Xponent software. The geometric mean of two technical replicates for each sample were used in downstream analyses. The data for the cytokine/chemokine panel is available in Supplemental Table 2.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell isolation and RNA-sequencing

mRNA and micro-RNA were isolated and sequenced from PBMCs at the UR Genomics Research Center using their standard protocols. mRNA libraries were prepared with the Illumina TruSeq Kit v2, using oligo-dT beads for poly-A selection. mRNA was sequenced as single-ended 100 bp reads, yielding an average of 26.7 million reads per sample, for a total of 25 samples, representing four sample groups (normal control, n = 6; AS+, n = 6; HIV+, n = 6; HIV+ AS+, n = 7). Reads were trimmed with Trimmomatic to remove low-quality read tails or entire reads if the remaining post-trim read length was too short. Genome mapping was performed with STAR 2.5.2b to Human genome GRCh38.p7 with annotation from Gencode Genes version 25. Read counting was performed with the featureCounts from Subread. Count data is available in Supplemental Table 3. Small RNA was size-selected from total RNA and libraries were prepared with the Illumina TruSeq Small RNA kit. Small RNA was sequenced as single-ended 50 bp reads, with an average of 17 million reads per sample, for a total of 12 samples representing two sample groups (n = 6 each for HIV+ and HIV+ AS+). Reads were trimmed, mapped, annotated, and counted with the miRge pipeline55. Count data is available in Supplemental Table 4. miRNA were mapped to cell types using an available catalogue of miR expression in blood cell types56.

RNA-sequencing analysis

Small RNA-seq and mRNA-seq datasets were read into R (version 3.5.1)57, and filtered to remove sequences with low expression based on raw counts. For mRNA, any gene with fewer than 10 reads in all samples was excluded, leaving 19,861 genes for annotated gene types which may be polyadenylated (protein coding, lincRNA, and processed pseudogenes). For miRNA, any miRNA with fewer than 10 reads in all samples was excluded, yielding a set of 778 miRNAs used for downstream analyses. Exploratory analysis of each dataset (e.g. clustering, expression heatmaps, PCA) was performed on variance-stabilized transformed (VST) counts, as computed by the DESeq2 package (version 1.22.2)58. Functional and pathway enrichment was investigated with gProfileR (version 0.6.7)59. Differential expression analysis was performed with DESeq258 for both mRNA and miRNA (independently). The results of differential gene expression analysis for mRNA for all genes in the dataset are available in Supplemental Table 5, and differentially expressed miRNAs are available in Supplemental Table 6. For mRNA, groupwise comparisons were performed a corrected (FDR) p-value and fold-change cutoffs are noted in the results. Predicted miRNA target genes were found for differentially expressed miRNAs with the miRNAtap package (version 1.16.0)60 which incorporates predictions from five algorithms: DIANA, Miranda, Targetscan, PicTar, and miRDB. A given miR-target relationship was recorded if it was supported by at least two of the five prediction algorithms. The predicted targets of differentially expressed miRNAs are available in Supplemental Table 7, while functional enrichment analysis on these targets is available in Supplemental Table 8.

miRNA expression across normal human blood cells

Publicly available miRNA expression data across normal human blood cells were downloaded from GEO (GSE100467)56, and read into R with the BioConductor package IsoMirs (version 1.10.1)61 to obtain read counts for each of the 450 samples, representing ten cell populations from 162 unique donors. A matrix of raw counts was assembled by joining the individual sample results with dplyr, and miRNAs with very low counts (< 3) across all samples were excluded, leaving 1062 unique miRNAs with expression in at least one sample. Variance-stabilized (VST) and library-normalized counts were obtained with DESeq2. To obtain a summary of expression of each miRNA for each cell type, miRNA abundances were discretized in 5 levels, with higher-value bins representing higher expression. The number of bins was determined by , where is the number of samples for each cell type62. Relative levels of miRNA expression in each cell-type was given by the median of the discretized values.

Data integration analysis

Three types of data integration were performed; (1) miRNA and mRNA (2) cytokine and mRNA and (3) cytokine, mRNA and miRNA datasets were combined. Predicted miRNA targets were further filtered based on their significant negative correlation with mRNA (p < 0.05, ). Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) was performed on predicted miRNA target genes to identify genes that distinguish between HIV+ AS− and HIV+ AS+ samples. To identify transcriptional changes associated with cytokine levels, a single person transcription factor score (spTFscore) was calculated. Particularly, transcription factor (TF) target genes were predicted using positional weight matrices from JASPAR63 as described64,65. To calculate spTFscore, PCA was performed on TF target genes and was calculated from to , the PC at which 50% cumulative variance is explained (including PC1), is the unweighted PC score, and is the % variance explained by the PC. Since PC1 was associated with inter-individual variability in overall transcription levels rather than inter-group and transcription factor specific variability, the score was calculated starting with PC2. Thus, the spTFscore captures the contribution of each TF measured by variance of their target gene expression in each person. Pearson correlation was measured between all plasma cytokines and spTFscore. TF target gene weights were calculated as contributions to spTFscore by where is the loading of the gene in that PC, is the variance of each PC, is the variance explained by the first PC and is the PC at which 50% cumulative variance is explained, as with the spTFscore. In this way, the gene TF weights reflect the degree to which each gene contributes to the spTFscore for that TF.

Finally, to integrate miRNA, mRNA, and cytokine datasets an integrated multi-omic network was constructed and differential network analysis performed using xMWAS66. In order to include all data types, only samples from HIV+ AS− and HIV+ AS+ groups were included. Briefly, xMWAS constructs a matrix for pairwise correlation analysis using sparse partial least squares then ranks and filters the top association scores by p-value and association score. The edge lists are merged to a global network upon which community detection algorithms are utilized to group nodes into communities. Further, centrality scores are calculated for each node in each group separately, then compared to generate differences between groups. These centrality scores are available in Supplemental Table 9. Graphical representations of these networks were constructed in Cytoscape (version 3.7.0)67.

Validation of miRNAs

In order to validate RNA-sequencing results, levels of miRNAs 144-3p, 144-5p, 183-5p, 451a, and 4732-3p were measured in a subset of samples used for RNA-seq (n = 2 HIV+ AS+ , and n = 2, HIV+ AS−). In addition, we also measured the expression of these miRNAs in new samples (not used in RNA-seq, n = 3 HIV+ AS+ and n = 3 HIV+ AS−). RNA from new samples was extracted using miRNeasy mini kit (Cat # 217004, Qiagen). RT-qPCR was performed as per the manufacturer’s protocol (Taqman microRNA assay kits, Cat # 4427975 and 4440886) using the Biorad CFX Connect real time PCR machine. miRNA U6 was used as an endogenous control. The data is shown as ΔCt values. The results were analyzed by unpaired t-test using Graphpad Prism software.

Results and discussion:

Gene signatures of AS in persons living with HIV

Differential expression analysis identified seventeen genes in each of the two comparisons, HIV vs HIV+ AS+ and HIV vs control group (p-adj < 0.05). There was one common genes among the two contrasts, integrin alpha D (ITGAD/CD11d), which is strongly associated with inflammation68,69. Comparison between the HIV+ AS+ and control groups revealed five genes higher in HIV+ AS+ group: CD8A, CD8B, NPDC1, JAKMIP1, and STYK1; with five higher in control: IL17RE, SPTSSB, TPBG, OVOS, COL13A1. The presence of CD8A and CD8B provides strong evidence that there is an increase in CD8 cell activity in HIV+ AS+ group. Previous reports have shown memory CX3CR1+ CD8(+) cells may contribute to atherosclerosis in persons living with HIV70. On the other hand, downregulation of the IL-17 receptor (IL17RE) could be in response to increased immune stimulation. However, large variation in gene expression across individuals within groups led to identification of few differentially expressed (DE) genes.

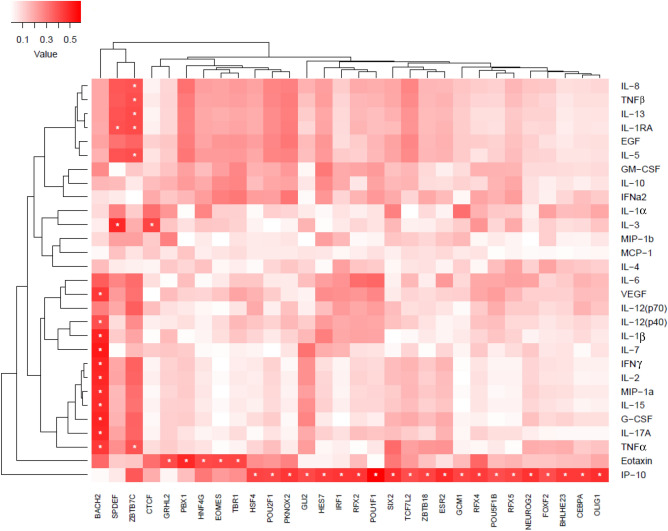

To investigate transcriptional changes in this highly variable data, we developed a single person transcription factor score (spTFscore) that could be compared with cytokine levels to identify transcription factors regulated by cytokines. The correlations between cytokine levels and the spTFscore revealed regulation by different arms of the immune system. Specifically, Th1, Th17 signature cytokines along with TNFα, MIP-1α and GCSF were associated with BACH2. It is known that Bach2–Batf interactions are required to prevent an excessive Th2 response71. IP10 was associated with several transcription factors such as IRF1 and CEBPα. Further analysis indicated that predicted targets of these transcription factors have little overlap, suggesting diverse transcriptional programs potentially associated with IP-10. IL-13, IL-8, TNFα, IL-1R and GMCSF were all associated with ZBTB7C, a TF that represses matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (Fig. 1). A number of the cytokines in this list are important modulators of atherosclerosis, including IL-15 which stimulates T cells and is known to be expressed in atherosclerotic lesions72–75.

Figure 1.

Association of activity of transcription factors (TFs) with cytokine and chemokine levels in plasma. Activity of the TFs was measured by single person transcription factor (spTF) scores. spTF was calculated as described in the methods. Briefly, TF targets as described in64 were used to perform PCA and subject specific PC scores were used to calculate pearson correlation (ranging from low to high depicted by white to red color bar) with cytokine levels. The significant correlations (p < 0.05) are indicated with stars. Analysis and graphical output done using in R (ver 3.5.1)57.

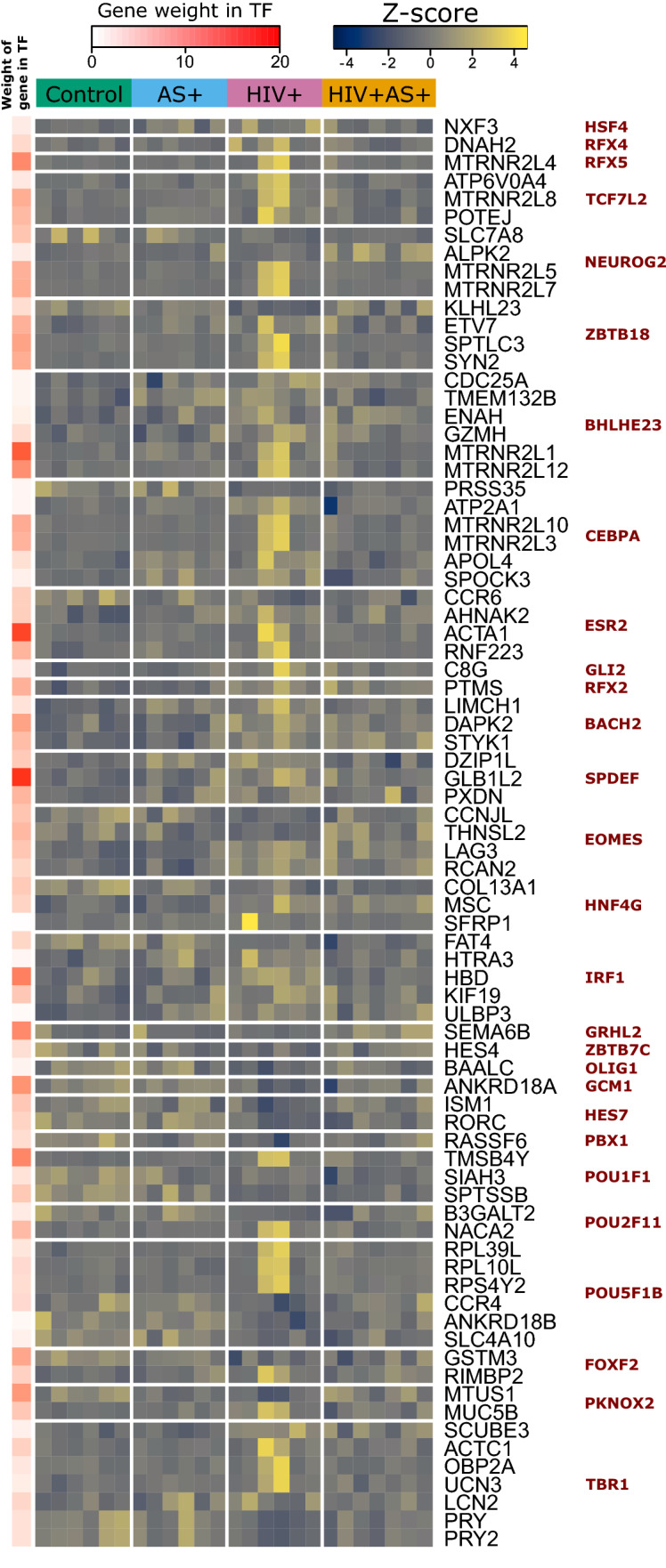

Many target genes of TFs significantly associated with the cytokines were differentially expressed (p-adj < 0.1 and LFC > 1.0) between HIV+ vs HIV+ AS+ group and HIV+ vs healthy (Fig. 2). The genes differentially expressed between HIV+ vs healthy and targets of TFs associated with IP10 include genes implicated in HIV infection e.g. CCR4, CCR6, and KIF19. CCR4 + and CCR6 + CD4 + T cells are highly permissive to HIV replication76. Interestingly, IP-10 enhances the recruitment of HIV-target cells and is a biomarker of early disease onset77. Eotaxin, a cytokine that was significantly different between HIV+ and control groups was also associated with several TFs, including GRHL12, PBX1, EOMES, and TBR1. Levels of circulating LAG3, an Eomes target gene, have been associated with HDL cholesterol and risk of coronary artery disease78. LAG3 here had increased expression in HIV+ group compared to control.

Figure 2.

Gene targets of transcription factors correlated with cytokine and chemokine levels in plasma. Expression of the differentially expressed targets (p-adj < 0.1, LFC > 1.0 in any comparison) of transcription factors from Fig. 1. Expression shown as z-scores across all four groups (indicated by top bar). The weight of each gene in determining spTF score is shown on left (white to red color bar) as the percentage of the variance accounted by the gene. Analysis and graphical output done in R (ver 3.5.1)57.

We also evaluated additional genes different at p-adj < 0.1 and LFC > 1.0 and associated with either HIV infection or AS (Supplementary Table 5). ATP1A2 is an Na+/K+ pump component involved in smooth muscle contraction, and it is differentially expressed in vasculature between myocardial infarction (MI) and stable angina79, and is also differentially expressed in our data between HIV+ and HIV+ AS+ . SLIT2 is a known inhibitor of HIV transmission80 that was significantly elevated in HIV+ vs control. GPR15 is a co-receptor for HIV and a possible biomarker for smoking status81,82; it had increased expression in HIV+ AS+ than HIV+ group. In this context, it may be a marker for the deleterious interaction between HIV and smoking status, which leads to atherosclerosis. VCAM1, a critical pro-atherosclerotic factor expressed on the endothelium, was upregulated in HIV+ vs control.

In conclusion, transcriptional changes and their relation with cytokine levels reveals several dysregulated interactions contributing to AS in the context of HIV and suggests further risk in HIV+ persons.

Characterization of micro-RNAs in HIV+ persons with carotid plaques

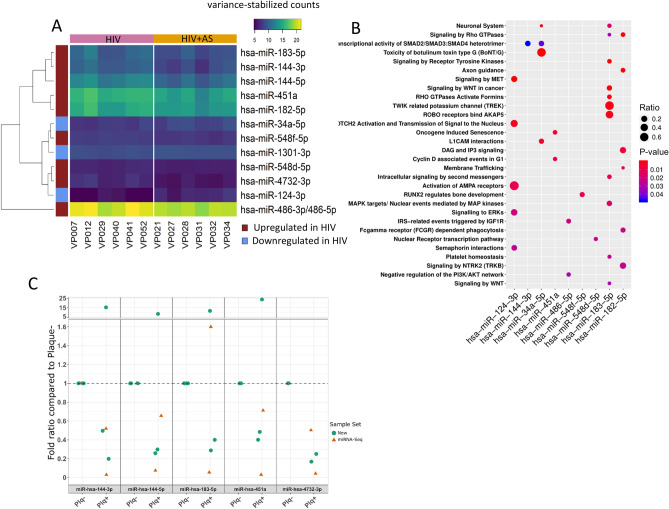

We performed genome-wide miRNA sequencing in HIV+ persons with (n = 6) and without (n = 6) carotid plaques. All 12 participants were males of ≥ 50 age to minimize the inter-person variation and maximize the differences across disease/infection groups in this small study. Moreover, in this focused group confounding variables were balanced, increasing the statistical power. Sequencing yielded at least 15 million short reads per sample, and most reads were ~ 22 nt after trimming, the typical length of miRNAs, indicating successful size selection and good read quality. Less than 10% of reads remained unmapped in all cases. miRNAs were identified and quantified from sequencing data with the miRge pipeline55. 778 miRNAs were considered after filtering out miRNAs that did not have at least 10 reads in all samples. Differential expression analysis identified 12 microRNAs with significant expression changes, out of which 3 were higher in HIV+ subjects with AS and 9 were higher in HIV+ subjects without AS (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Dysregulation of miRNAs during atherosclerosis in HIV positive persons: (A) Differentially expressed miRNA counts. HIV+ samples shown on left (pink bar on the top) and HIV+ AS+ on right (orange bar on the top). miRNAs are clustered hierarchically with directionality shown by a left red (high in HIV+ group)/blue (high in HIV+ AS+ group) color bar56. (B) Pathway analysis of predicted target genes of DE miRNA. Dots represent significantly enriched pathways with color representing p-value and size of dot representing proportion of target genes in the pathway. (C) Fold-ratio of selected miRNAs in HIV+ AS− (Plq-) and HIV+ AS+ (Plq +) samples, as measured by RT-qPCR. Samples included a subset of those previously profiled by miRNA-Seq (orange triangles), as well as new samples (green circles). Graphical output for (A–C) and analysis for (A,B) done in R (version 3.5.1).

A subset of these differently expressed miRNAs that have been previously implicated in cardiovascular disease are discussed below. High miR-124-3p indicated susceptibility to atherosclerosis in a population of smokers83. In our dataset, miR-124-3p had no or very low expression in HIV+ AS− samples, but was found in 5 of 6 HIV+ AS+ samples (only two of which were identified as current smokers) indicating that the elevated level of miR-124-3p may be indicative of AS risk outside of the context of smoking. Another miRNA, miR-182-5p is found to be upregulated about two times in myocardial infarction vs controls in whole blood samples, however this miRNA was downregulated in HIV+ persons with AS compared to without84. miR-34a-5p is expressed in T-cells (CD3+ and CD4+), and is negatively correlated with T-cell counts after HIV infection, possibly due to lysis of T-cells85,86. miR-34a-5p has also been shown to be increased in heart failure and decreased in peripheral arterial disease87–89, in addition to being upregulated in endothelial progenitor cells from coronary artery disease patients90. In ApoE-deficient mice fed a “western-style” diet for 16 weeks, the mice developed severe atherosclerotic lesions and exhibited progressive upregulation of miR-34a-5p91. In accordance with these observations linking higher levels of miR-34a-5p to AS, we find this miRNA to be elevated in most of our HIV+ AS+ samples compared to HIV+ alone.

To validate the miRNAs identified by RNA-seq we performed RT-qPCR on 5 miRNAs in ten participants (Fig. 3C). The miRNAs miR-144-3p, miR-144-5p, miR-183-5p, miR-451a and miR-4732-3p were chosen based on the largest fold change between HIV+ AS+ vs HIV+ AS−. The samples were run in pairs as shown in Fig. 3C. All of the 5 miRNAs were lower in HIV+ AS+ compared to HIV+ AS− in RNA-seq experiments. RT-qPCR validated this observation when a subset of the same samples from RNA-seq were used. Among the new independent samples one pair showed an opposite direction, whereas all other samples validated the observations from RNA-seq. The five validated miRNAs are novel and very little is known with respect to their role in HIV infection and atherosclerosis. miR-144-3p92,93 and miR-183-5p94 have been linked atherosclerosis, cholesterol metabolism, and HIV infection in different organisms and model systems. In consensus with our observations miR-451a has been found to be reduced in circulation of subjects with coronary heart disease95.

To investigate which specific cell-types are known to express the differentially expressed miRNAs from our study, we used a public compendium of miRNA expression across human blood cell types56. Specifically, expression of differentially expressed miRNAs was investigated in the public compendium to determine the cell types that normally express the differentially expressed miRNAs (Supplemental Fig. 1). This analysis revealed that only miR-486-5p was ubiquitously expressed, and that the other DE miRNA may exhibit low or no expression in normal CD8+ or CD4+ T cells and CD14+ monocytes (Supplemental Fig. 1). To further characterize the effect of these miRNAs, we performed pathway analysis of their predicted targets (Fig. 3B). Importantly, similar to previous findings, miR-124-3p was enriched in ‘Signaling to ERKs’ and ‘Activation of AMPA Receptors’. miR-183-5p was associated with a number of pathways including the ‘Twik related potassium channel (TREK)’, ‘Signaling by Receptor Tyrosine Kinases’, and ‘ROBO receptors bind AKAP5′. Finally, miR-182-5p was associated with ‘DAG and IP3 Signaling’, ‘Signaling by Rho GTPases’, and ‘FCγ receptor (FCGR) dependent phagocytosis’96,97.

Thus, most of our findings corroborate with previously known roles of miRNAs in atherosclerosis, and reveal novel insights about development of AS in persons living with HIV. However, most previous studies have been performed with different model systems, experimental designs, and protocols, necessitating extended study in people living with HIV.

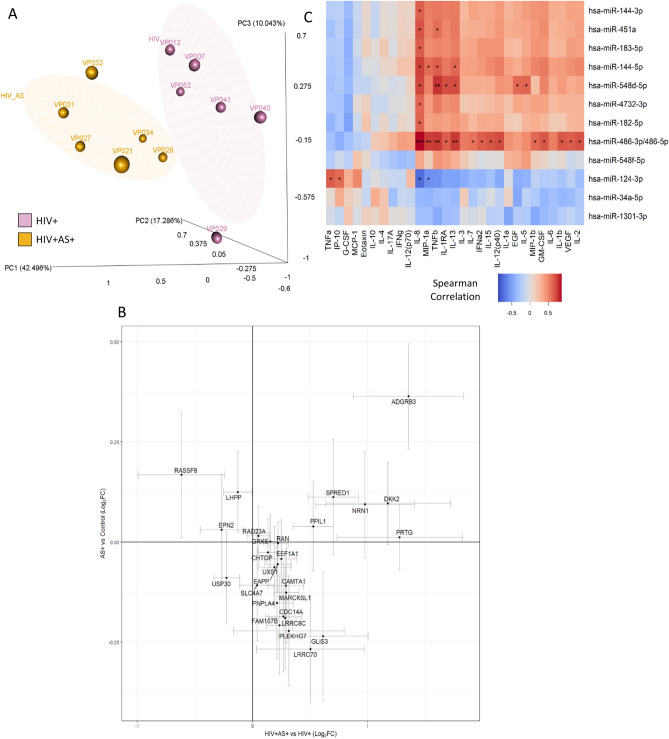

Role of miRNAs in regulatory networks

miRNAs are important regulators of mRNA turnover and are thought to regulate 10–30% of mRNAs98–100. miRNAs function post-transcriptionally via the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to inhibit mRNA. Hence, we found predicted targets of differentially expressed miRNAs that also had significant negative correlation with mRNA expression in our data. A set of 27 of these genes with highest loadings from Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) was sufficient to differentiate the HIV+ AS+ and HIV+ AS− groups (Fig. 4A). This list included genes such as SPRED1 which is involved in IL-15 and FGFR1 signaling, GRK6 which is involved in the myometrial relaxation and contraction pathway and calcium regulation in cardiac cells, and RAN which is involved in the export of viral ribonucleoprotein. Also in this set of 27 genes is SLC4A7, a critical sodium and bicarbonate transporter involved in generation of Nitric Oxide (NO) signaling and blood pressure regulation; NO signaling has been linked to AS risk101. Importantly, 15/27 of these genes are upregulated in HIV+ AS+ vs HIV but downregulated in AS vs healthy control with no correlation between the two changes, indicating that these genes describe an HIV-specific atherosclerosis state (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Interaction of miRNA expressed in PBMCs with mRNA expression in PBMCs and cytokines and chemokines levels in plasma: (A) miRNA target genes were identified using miRNAtap package60 and were further filtered to keep only genes whose expression was negatively correlated with the expression of their regulator miRNA. The filtered genes were analyzed by Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) and 27 target genes were selected based on separation between AS+ (yellow)/− (purple) groups. PCA with 27 genes are shown (s). (B) Log2 fold change of HIV+ AS+ vs HIV+ and AS+ vs healthy control for 27 target genes. (C) Association of miRNA with cytokine and chemokines using the data from HIV+ AS+ and HIV+ AS− groups. Spearman correlation; significant associations are indicated with stars (*p-value < 0.05, **p-value < 0.005, ***p-value < 0.001). Analysis and graphical output done in R (ver 3.5.1)57.

miRNAs can be transcriptionally regulated by cytokine signaling102 while cytokine production103 and signal transduction can be influenced by miRNAs104,105. Hence, we asked which cytokines are significantly associated with DE miRNAs. IL-8 was positively associated with most of the miRNAs but negatively associated with miR-124-3p (Fig. 4C). miR-124-3p, which regulates ERK signaling and activation of AMPA receptors, was also negatively associated with MIP-1α but positively associated with TNFα and IP10 (also known as CXCL10). IP10 is induced during antiviral response and was higher in HIV+ and HIV+ AS+ groups (not statistically significant, p = 0.08). Numerous studies have reported abnormally high plasma IP-10 levels in the context of HIV infection, and IP10 is considered an important pro-inflammatory factor in the HIV disease process106. IP-10 and TNFα are both associated with miR-124-3p (Fig. 4C) and are highly expressed in HIV+ AS+ group. As discussed before, we found IP10 to be associated with diverse transcriptional programs activating several genes implicated in HIV infection. The role of miR-124-3p in this regulation needs to be further investigated. IL8 has interactions with miRNA in a number of diseases and conditions107. Other miRNAs have been found to de-repress expression of IL6 and IL8 in a cell-based model of sepsis108. These results suggest novel regulatory relationships between miRNAs and IL-8; however, IL-8 levels were not different in HIV+ persons with and without AS. IL-8 expression (at both the gene and plasma levels) has been reported to be significantly elevated in HIV-infected children that were not yet receiving ART therapy, and decreased after therapy began109. Several additional associations were found between miRNAs and cytokines (Fig. 4C). Thus, this work suggests a role for pro-inflammatory cytokines in regulating miRNAs which can in turn regulate gene programs.

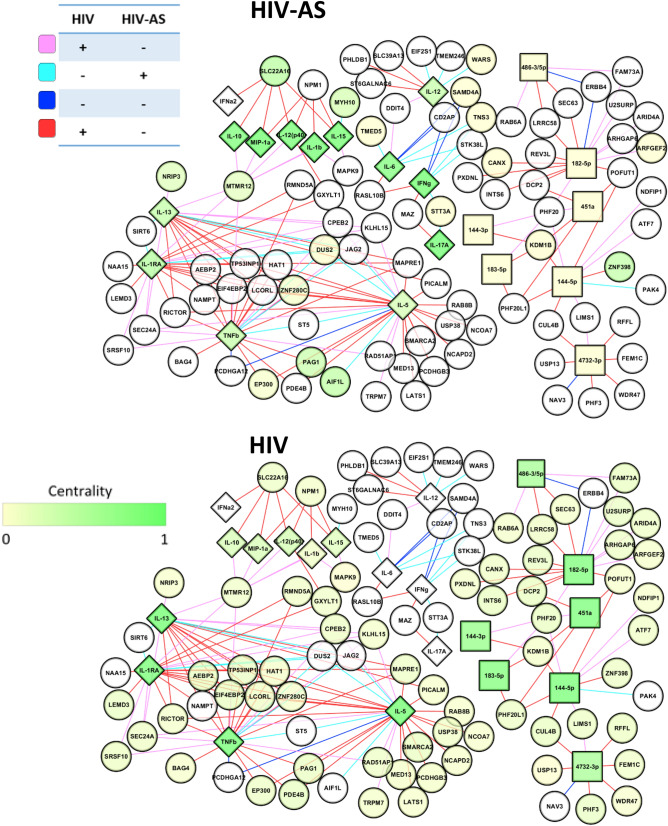

Integrated network of cytokines, miRNA and mRNA

Finally, having established several links between cytokines, miRNAs, and mRNAs in a pairwise manner, we set out to investigate such interactions systematically. Hence, we constructed a network, incorporating all three data types- mRNA, miRNA, and cytokine profiles, for HIV+ and HIV+ AS+ groups. The network includes 175 genes, 23 cytokines and 10 miRNAs (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 1). Differential network analysis using eigenvector centrality identify nodes with higher importance with AS in the context of HIV.

Figure 5.

Regulation of AS associated signaling in the context of HIV. The network of association between miRNA, mRNA and cytokines in HIV+ people with and without AS. Squares represent miRNA, circles represent mRNA and diamonds represent cytokines and chemokines. Coloring of nodes indicates centrality score for HIV+ AS+ group (top) or HIV group (bottom). Coloring of edges represents sign of correlation between nodes in HIV+ or HIV+ AS+ groups as shown in the edge color key. Analysis performed in R (ver 3.5.1)57, with graphical output from Cytoscape (version 3.7.0)67.

Higher centrality of cytokines and chemokines compared to the genes was expected because a small number of cytokines measured were connected to many miRNA and genes. Three cytokines, IL1β, IL15, and MIP1α, which were also associated with BACH2 were more central in HIV+ AS+ than HIV suggesting their role in regulating miRNA and mRNA expression in persons living with HIV and atherosclerosis. IL13, IL5, TNFβ, and IL1-RA associated with ZBTB7C, were more central in HIV than HIV+ AS+ groups, along with hsa-miR-144-5p, hsa-miR-451a, and hsa-miR-182-5p. hsa-miR-451, one of the miRNA independently validated in this study, has been shown in rats to target the IL6 receptor in arterial smooth muscle cells110, and IL-6 knockdown in mice induced release of cytokines including IL6, TNF, CCL5/RANTES, and CCL3/MIP1α111. This is corroborated by increased centrality of these downstream cytokines in the HIV+ AS+ group. hsa-miR-182-5p, on the other hand, is a pro-atherosclerotic AKT1-inhibitor implicated in acute coronary disease (atherosclerosis of the heart)112 via endothelial cell dysfunction. Positive association between pro-AS miRNAs and anti-inflammatory/anti-AS cytokines such as IL5113 might suggest a compensatory response that delays AS. Thus, our network analysis identifies two critical atherosclerosis-related miRNAS− hsa-miR-182-5p which affects endothelial cells, and hsa-miR-144-5p (also validated by RT-qPCR) which affects macrophages, known to be elevated in high viral titer HIV infection.

Conclusion

Taken together, this study revealed novel miRNAs differentially expressed in AS+ /- people living with HIV, and identified many interesting interactions of miRNAs with cytokines. Centrality measures indicate that miRNAs display importance in regulating molecular networks in people living with HIV, whereas cytokines play a greater role in people living with HIV and AS. Though mRNA measurements were highly variable even with very strict subject selection criteria, novel computational approaches such as single person transcription factor score, and leveraging public domain datasets, provided insights about regulatory factors. Nevertheless, several findings in this study require future validation in larger cohorts with more demographic variables and further expansion of the experimental groups.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

J.T. conceptualized and designed the experiments. The clinical cohort was established by G.S., J.A. and S.B.M. PBMCs and plasma were isolated by M.S. A.C., R.P. and J.T. conceptualized the analysis. A.C., R.P., and L.B. analyzed the data. A.C., R.P., and J.T. wrote the manuscript. A.T. managed the database of larger clinical cohort and assisted this study to use relevant entries. All authors contributed to interpreting the results and editing the manuscript.

Funding

RP was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine F31 LM012893 and is a Trainee in the Medical Scientist Training Program, T32 GM07356. AC and LB were partially supported by the P30 AI078498 (UR-CFAR) grant. LB partially supported by the T32 AI118689. JT was supported UM1 AI069511, P30 AI078498 and R21 AI136668. The authors acknowledge funding for this work from the U.S. National Institutes of Health R01 HL123346 (to SBM, JA, GS), R01 HL128155, R01 NS066801 (to SBM, MVS) and also the University of Rochester Center for AIDS Research (UR-CFAR; P30 AI078498) for their support of core facilities.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-82429-4.

References

- 1.Brodin P, et al. Variation in the human immune system is largely driven by non-heritable influences. Cell. 2015;160:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brodin P, Davis MM. Human immune system variation. Nat. Publ. Gr. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liston A, Carr EJ, Linterman MA. Shaping variation in the human immune system. Trends Immunol. 2016;37:637–646. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Currier JS, et al. Epidemiological evidence for cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected patients and relationship to highly active antiretroviral therapy. Circulation. 2008;118:e29–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.189624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;92:2506–2512. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Currier JS, et al. Coronary heart disease in HIV-infected individuals. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2003;33:506–512. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh MV, et al. Senescent phenotype induced by p90RSK-NRF2 signaling sensitizes monocytes and macrophages to oxidative stress in HIV-positive individuals: Implications for atherogenesis. Circulation. 2019;139:1199–1216. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lorenz MW, et al. Both long-term HIV infection and highly active antiretroviral therapy are independent risk factors for early carotid atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196:720–726. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Triant VA, Meigs JB, Grinspoon SK. Association of C-reactive protein and HIV infection with acute myocardial infarction. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2009;51:268–273. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a9992c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freiberg MS, et al. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013;173:614–622. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paisible AL, et al. HIV infection, cardiovascular disease risk factor profile, and risk for acute myocardial infarction. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2015;68:209–216. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grunfeld C, et al. Preclinical atherosclerosis due to HIV infection: Carotid intima-medial thickness measurements from the FRAM study. AIDS. 2009;23:1841–1849. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d3b85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsue PY, et al. Role of viral replication, antiretroviral therapy, and immunodeficiency in HIV-associated atherosclerosis. Aids. 2009;23:1059–1067. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832b514b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pereyra F, et al. Increased coronary atherosclerosis and immune activation in HIV-1 elite controllers. AIDS. 2012;26:2409–2412. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835a9950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corti R, Hutter R, Badimon JJ, Fuster V. Evolving concepts in the triad of atherosclerosis, inflammation and thrombosis. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 2004;17:35–44. doi: 10.1023/B:THRO.0000036027.39353.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmberg, S. D. et al. Protease inhibitors and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with HIV-1. Lancet360 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Mary-krause M, Cotte L, Simon A, Partisani M. Increased risk of myocardial infarction with duration of protease inhibitor therapy in HIV-infected men Dominique Costagliola a, and the Clinical Epidemiology Group from the French Hospital Database. Aids. 2003 doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000096857.36052.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update. Circulation. 2012;125:2–220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318245fac5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deeks SG. HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annu. Rev. Med. 2011;62:141–155. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042909-093756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friis-Møller N, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in HIV patients—Association with antiretroviral therapy. Results from the DAD study. AIDS. 2003;17:1179–1193. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200305230-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zidar, D. A. et al. Oxidized LDL levels are increased in HIV infection and may drive monocyte activation. in J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr.69, 154–160 (Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.KITA, T. et al. Role of oxidized LDL in atherosclerosis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.947, 199–206 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Kearns A, Gordon J, Burdo TH, Qin X. HIV-1-associated atherosclerosis: Unraveling the missing link. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017;69:3084–3098. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo H, Callaway JB, Ting JPY. Inflammasomes: Mechanism of action, role in disease, and therapeutics. Nat. Med. 2015;21:677–687. doi: 10.1038/nm.3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adoro, S. et al. IL-21 induces antiviral microRNA-29 in CD4 T cells to limit HIV-1 infection. Nat. Commun.6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Nazari-Jahantigh M, et al. MicroRNA-155 promotes atherosclerosis by repressing Bcl6 in macrophages. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:4190–4202. doi: 10.1172/JCI61716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vacca M, et al. Integrative miRNA and whole-genome analyses of epicardial adipose tissue in patients with coronary atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2016;109:228–239. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang Y, Shi C, Manduchi E, Civelek M, Davies PF. MicroRNA-10a regulation of proinflammatory phenotype in athero-susceptible endothelium in vivo and in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:13450–13455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002120107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicoli S, et al. MicroRNA-mediated integration of haemodynamics and Vegf signalling during angiogenesis. Nature. 2010;464:1196–1200. doi: 10.1038/nature08889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madrigal-Matute J, Rotllan N, Aranda JF, Fernández-Hernando C. MicroRNAs and atherosclerosis. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2013;15:322. doi: 10.1007/s11883-013-0322-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feinberg MW, et al. MicroRNA regulation of atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2016;118:703–720. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shao, D. et al. Dietary compounds have potential in controlling atherosclerosis by modulating macrophage cholesterol metabolism and inflammation via miRNA. npj Sci. Food2 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Wei Y, Nazari-Jahantigh M, Neth P, Weber C, Schober A. MicroRNA-126, -145, and -155: a therapeutic triad in atherosclerosis? Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013;33:449–454. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rotllan N, Ramírez CM, Aryal B, Esau CC, Fernández-Hernando C. Therapeutic silencing of MicroRNA-33 inhibits the progression of atherosclerosis in Ldlr-/- mice—Brief report. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013;33:1973–1977. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lovren, F. et al. MicroRNA-145 targeted therapy reduces atherosclerosis. Circulation126 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Woeller, C. F. et al. MicroRNAs as novel biomarkers of deployment status and exposure to polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins/dibenzofurans. J. Occup. Environ. Med.58 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Huang J, et al. MicroRNA miR-126-5p enhances the inflammatory responses of monocytes to lipopolysaccharide stimulation by suppressing cylindromatosis in chronic HIV-1 infection. Pathogenesis Immun. 2017;91:2048–2064. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02048-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiang K, Liu H, Rice AP. MiR-132 enhances HIV-1 replication. Virology. 2013;438:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farberov L, et al. MicroRNA-mediated regulation of p21 and TASK1 cellular restriction factors enhances HIV-1 infection. J. Cell Sci. 2015;128:1607–1616. doi: 10.1242/jcs.167817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swaminathan S, Murray DD, Kelleher AD. The role of microRNAs in HIV-1 pathogenesis and therapy. AIDS. 2012;26:1325–1334. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328352adca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Su, B. et al. Potential application of microRNA profiling to the diagnosis and prognosis of HIV-1 infection. Front. Microbiol.9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Balasubramaniam, M., Pandhare, J. & Dash, C. Are microRNAs important players in HIV-1 infection? An update. Viruses10 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Faccini, J. et al. Circulating MIR-155, MIR-145 and let-7c as diagnostic biomarkers of the coronary artery disease. Sci. Rep.7 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Ballegaard, V. et al. MicroRNA-210, MicroRNA-331, and MicroRNA-7 are differentially regulated in treated HIV-1-infected individuals and are associated with markers of systemic inflammation. in J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr.74, e104–e113 (Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Hubert A, et al. Elevated abundance, size, and MicroRNA content of plasma extracellular vesicles in viremic HIV-1+ patients: Correlations with known markers of disease progression. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2015;70:219–227. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan N, et al. MicroRNA biomarkers associated with type 1 myocardial infarction in HIV positive individuals. AIDS. 2019 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang L, et al. MiR-132 inhibits expression of SIRT1 and induces pro-inflammatory processes of vascular endothelial inflammation through blockade of the SREBP-1c metabolic pathway. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2014;28:303–311. doi: 10.1007/s10557-014-6533-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosenfeld, M. E. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: Direct versus indirect mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol.13 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Deeks, S. G., Tracy, R. & Douek, D. C. Systemic effects of inflammation on health during chronic HIV infection. Immunity39 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Davis, M. M., Tato, C. M. & Furman, D. Systems immunology: Just getting started. Nat. Immunol.18 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Jaworowski, A., Hearps, A. C., Angelovich, T. A. & Hoy, J. F. How monocytes contribute to increased risk of atherosclerosis in virologically-suppressed HIV-positive individuals receiving combination antiretroviral therapy. Front. Immunol.10 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Parks, B. W. & Lusis, A. J. Macrophage accumulation in atherosclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med.369 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Gerrity, R. G. & Naito, H. K. Ultrastructural identification of monocyte-derived foam cells in fatty streak lesions. Artery8 (1980). [PubMed]

- 54.Churov, A., Summerhill, V., Grechko, A., Orekhova, V. & Orekhov, A. MicroRNAs as potential biomarkers in atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci.20 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Baras AS, et al. miRge—A multiplexed method of processing small rna-seq data to determine microRNA entropy. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0143066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Juzenas S, et al. A comprehensive, cell specific microRNA catalogue of human peripheral blood. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:9290–9301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/.

- 58.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raudvere U, et al. g:Profiler: A web server for functional enrichment analysis and conversions of gene lists (2019 update) Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W191–W198. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pajak, M. & Simpson, T. I. Package ‘miRNAtap’. 1–8 (2018). 10.18129/B9.bioc.miRNAtap.

- 61.Lorena Pantano G. E. isomiRs. Bioconductor. 2016 doi: 10.18129/B9.bioc.isomiRs. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meyer, P. E. Package ‘infotheo’: Information-Theoretic Measures. (2015).

- 63.Mathelier A, et al. JASPAR 2016: A major expansion and update of the open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D110–D115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Twisk, D., Murphy, S. P. & Thakar, J. Optimized logic rules reveal interferon-γ-induced modes regulated by histone deacetylases and protein tyrosine phosphatases. Immunology1 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Thakar, J., Hartmann, B. M., Marjanovic, N., Sealfon, S. C. & Kleinstein, S. H. Comparative analysis of anti-viral transcriptomics reveals novel effects of influenza immune antagonism. BMC Immunol.16 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Uppal K, Ma C, Go Y-M, Jones DP. xMWAS: A data-driven integration and differential network analysis tool. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:701–702. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res.13 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Yasunari, M. et al. Integrin αdβ2 (CD11d/CD18) is expressed by human circulating and tissue myeloid leukocytes and mediates inflammatory signaling. PLoS One9 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Idzkowska, E. et al. The role of different monocyte subsets in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and acute coronary syndromes. Scand. J. Immunol.82 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Mudd JC, et al. Inflammatory function of CX3CR1 + CD8 + T cells in treated HIV infection is modulated by platelet interactions. J. Infect. Dis. 2016;214:1808–1816. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kuwahara, M. et al. Bach2-Batf interactions control Th2-type immune response by regulating the IL-4 amplification loop. Nat. Commun.7 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Wuttge, D. M., Eriksson, P., Sirsjö, A., Hansson, G. K. & Stemme, S. Expression of interleukin-15 in mouse and human atherosclerotic lesions. Am. J. Pathol.159 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Panigrahi S, et al. CX3CL1 and IL-15 promote CD8 T cell chemoattraction in HIV and in atherosclerosis. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008885. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Engelbertsen D, et al. IL-1R and MyD88 signalling in CD4+ T cells promote Th17 immunity and atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018;114:180–187. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Niki, T. et al. Elevated concentration of interferon-inducible protein of 10 kD (IP-10) is associated with coronary atherosclerosis. Int. Heart J.56 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Gosselin, A. et al. Peripheral blood CCR4 + CCR6 + and CXCR3 + CCR6 + CD4 + T cells are highly permissive to HIV-1 infection . J. Immunol.184 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Ploquin, M. J. et al. Elevated basal pre-infection CXCL10 in plasma and in the small intestine after infection are associated with more rapid HIV/SIV disease onset. PLoS Pathog.12 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Golden, D. et al. Lymphocyte activation gene 3 and coronary artery disease. JCI Insight1 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Wongsurawat T, et al. Distinctive molecular signature and activated signaling pathways in aortic smooth muscle cells of patients with myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis. 2018;271:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shrivastava A, Prasad A, Kuzontkoski PM, Yu J, Groopman JE. Slit2N inhibits transmission of HIV-1 from dendritic cells to T-cells by modulating novel cytoskeletal elements. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:1–14. doi: 10.1038/srep16833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kõks S, Kõks G. Activation of GPR15 and its involvement in the biological effects of smoking. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017;242:1207–1212. doi: 10.1177/1535370217703977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pöhlmann S, et al. Co-receptor usage of BOB/GPR15 in addition to CCR5 has no significant effect on replication of simian immunodeficiency virus in vivo. J. Infect. Dis. 1999;180:1494–1502. doi: 10.1086/315097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.de Ronde MWJ, et al. High miR-124-3p expression identifies smoking individuals susceptible to atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2017;263:377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bai R, et al. miR-941 as a promising biomarker for acute coronary syndrome. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2017;17:227. doi: 10.1186/s12872-017-0653-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Reynoso, R. et al. MicroRNAs differentially present in the plasma of HIV elite controllers reduce HIV infection in vitro. Sci. Rep.4 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Hart M, et al. Identification of miR-34a-target interactions by a combined network based and experimental approach. Oncotarget. 2016;7:34288–34299. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stather PW, et al. Differential microRNA expression profiles in peripheral arterial disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2013;6:490–497. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.000053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.De Rosa S, et al. Transcoronary concentration gradients of circulating microRNAs in heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2018;20:1000–1010. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lu Y, Thavarajah T, Gu W, Cai J, Xu Q. Impact of miRNA in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018;38:e159–e170. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.310227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang RN, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling in development and human diseases. Genes Dis. 2014;1:87–105. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shan Z, et al. Differentially expressed microRNAs at different stages of atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice. Chin. Med. J. (Engl) 2013;126:515–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Icli, B. & Feinberg, M. W. MicroRNAs in dysfunctional adipose tissue: Cardiovascular implications. Cardiovasc. Res.113 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 93.Duskova, K. et al. MicroRNA regulation and its effects on cellular transcriptome in human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) infected individuals with distinct viral load and CD4 cell counts. BMC Infect. Dis.13 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 94.Zalewski, D. P. et al. Dysregulations of microRNA and gene expression in chronic venous disease. J. Clin. Med.9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95.Melak, T. & Baynes, H. W. Circulating microRNAs as possible biomarkers for coronary artery disease: A narrative review. Electron. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med.30 (2019). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.Ron-Harel N, Sharpe AH, Haigis MC. Mitochondrial metabolism in T cell activation and senescence: A mini-review. Gerontology. 2014;61:131–138. doi: 10.1159/000362502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Joshi T, Butchar JP, Tridandapani S. Fcγ receptor signaling in phagocytes. Int. J. Hematol. 2006;84:210–216. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.06140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.John B, et al. Human microRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Berkhout B, Jeang KT. RISCy business: MicroRNAs, pathogenesis, and viruses. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:26641–26645. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Houzet, L. & Jeang, K.-T. MicroRNAs and human retroviruses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech.1809, 686–693 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 101.Boedtkjer E, et al. Disruption of Na+, HCO3− cotransporter NBCn1 (slc4a7) inhibits NO-mediated vasorelaxation, smooth muscle Ca2+ sensitivity, and hypertension development in mice. Circulation. 2011;124:1819–1829. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.015974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Garavelli S, De Rosa V, de Candia P. The multifaceted interface between cytokines and microRNAs: An ancient mechanism to regulate the good and the bad of inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:3012. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Asirvatham AJ, Magner WJ, Tomasi TB. miRNA regulation of cytokine genes. Cytokine. 2009;45:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.O’Neill LA, Sheedy FJ, McCoy CE. MicroRNAs: The fine-tuners of Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:163–175. doi: 10.1038/nri2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jiang S, et al. MicroRNA-155 functions as an oncomiR in breast cancer by targeting the suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 gene. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3119–3127. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lei J, Yin X, Shang H, Jiang Y. IP-10 is highly involved in HIV infection. Cytokine. 2019;115:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bhaumik, D. et al. MicroRNAs miR-146a/b negatively modulate the senescence-associated inflammatory mediators IL-6 and IL-8. Aging (Albany. NY).1, 402–411 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 108.Pfeiffer D, Roßmanith E, Lang I, Falkenhagen D. miR-146a, miR-146b, and miR-155 increase expression of IL-6 and IL-8 and support HSP10 in an In vitro sepsis model. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0179850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pananghat, A. N. et al. IL-8 alterations in HIV-1 infected children with disease progression. Medicine (United States)95 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 110.Chen LJ, et al. MicroRNA mediation of endothelial inflammatory response to smooth muscle cells and its inhibition by atheroprotective shear stress. Circ. Res. 2015;116:1157–1169. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rosenberger CM, et al. miR-451 regulates dendritic cell cytokine responses to influenza infection. J. Immunol. 2012;189:5965–5975. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhu L, et al. Circulating miR-182-5p and miR-5187-5p as biomarkers for the diagnosis of unprotected left main coronary artery disease. J. Thorac. Dis. 2019;11:1799–1808. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.05.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhao W, et al. Macrophage-specific overexpression of interleukin-5 attenuates atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Gene Ther. 2015;22:645–652. doi: 10.1038/gt.2015.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.