Significance

The sensory presence of gods and spirits is central to many of the religions that have shaped human history—in fact, many people of faith report having experienced such events. But these experiences are poorly understood by social scientists and rarely studied empirically. We present a multiple-discipline, multiple-methods program of research involving thousands of people from diverse cultures and religions which demonstrates that two key factors—cultural models of the mind and personal orientations toward the mind—explain why some people are more likely than others to report vivid experiences of gods and spirits. These results demonstrate the power of culture, in combination with individual differences, to shape something as basic as what feels real to the senses.

Keywords: religion, porosity, absorption, spiritual experience, voices

Abstract

Hearing the voice of God, feeling the presence of the dead, being possessed by a demonic spirit—such events are among the most remarkable human sensory experiences. They change lives and in turn shape history. Why do some people report experiencing such events while others do not? We argue that experiences of spiritual presence are facilitated by cultural models that represent the mind as “porous,” or permeable to the world, and by an immersive orientation toward inner life that allows a person to become “absorbed” in experiences. In four studies with over 2,000 participants from many religious traditions in the United States, Ghana, Thailand, China, and Vanuatu, porosity and absorption played distinct roles in determining which people, in which cultural settings, were most likely to report vivid sensory experiences of what they took to be gods and spirits.

The ancient texts of the great religions describe voices that speak from the air, visions that others cannot see, dead people who walk among the living. They are extraordinary stories, but the phenomenological events that they describe are deeply human and far more common than many realize (1). For the people who experience them, these moments can feel so vividly sensory that they are interpreted as evidence that an invisible other—a god, a spirit—is real. Such events change lives and in turn shape history. Augustine’s conversion to Christianity, one of the most influential events in the history of Christianity, was sparked by hearing a disembodied voice (2), and on the eve of the Montgomery bus boycotts, terrified by threats, Martin Luther King, Jr., heard God say that he would be with him and resolved to go forward (3)—a decision of momentous significance for the Civil Rights Movement.

Spiritual presence events—the various anomalous, often vividly sensory, events which people attribute to gods, spirits, or other supernatural forces (4)—do not happen for everyone. Within a religious community, people vary in how frequently they experience such events (5); there are deeply religious people who want to hear gods and spirits speak and cannot and atheists who report anomalous sensory events nearly indistinguishable from religious experiences (6). One might suspect that voices and visions are signs of mental illness, but many people report anomalous sensory experiences in the absence of psychiatric distress (7). Moreover, the ethnographic record suggests that such events are more common in some cultural settings than in others (8, 9). Spiritual presence events thus present a striking example of variability in human sensory experience. Why are certain people, and people in certain social worlds, more likely to experience these extraordinary events?

We bring to this question a theoretical perspective that centers on people’s cultural models of, and personal orientations toward, their own minds. In many aspects of everyday life, cultural models (10) or, in other parlance, “folk theories” (11) and personal orientations (attitudes, motivations, and tendencies) (12), play complementary roles in shaping people’s experience and behavior: Cultural models represent how the world works (that is, how it is often understood to work in a particular social-cultural setting), and personal orientations lead an individual to engage with that world in a particular way. Neuroscientific studies suggest that hallucinations arise through judgments of events at the edge of awareness—an indistinct noise in the next room, one’s own inner voice—and that interpretation alters the phenomenological quality of such events (13, 14). Building on this work, we propose that the relevant cultural model which undergirds spiritual presence events is a model of experience itself and that the relevant personal orientation is an orientation toward experience. The central claim of this paper is that cultural models of the mind and personal orientations toward the mind shape people’s phenomenological experiences and their interpretations of these experiences in ways that manifest as cultural and individual differences in reports of spiritual presence events.

For cultural models, we focus in particular on what we call “porosity”: the idea that the boundary between “the mind” and “the world” is permeable. Intuitions that wishes or curses might come true, that strong emotions might linger in a room to affect others, or that some people might be able to read minds are examples of porosity that might be familiar to (although perhaps not endorsed by) many secular Western readers. Porosity appears to be an aspect of folk beliefs about the mind that varies quite considerably across cultural settings. The philosopher Charles Taylor has made the widely influential claim that modern, predominantly secular cultures represent the self as “bounded”; that these cultures represent people as having interior mental spaces separate from the outer world; and that these interior mental spaces are considered the source of fundamental meaning (15). Taylor briefly contrasts the idea of the bounded self to the notion of a porous self, more common outside of modern Western societies, in which the boundary between the mind and the world is taken to be permeable and perhaps less salient. We have adopted the term porosity to refer to ideas about how a person might receive thoughts, emotions, or knowledge directly from outside sources (e.g., through divine inspiration, divination, telepathy, or clairvoyance) and ideas about how thoughts and feelings might have a direct causal impact on the world (e.g., through witchcraft, healing energy, or shamanic powers). Ethnographic work suggests that societies differ in the degree to which minds are represented as porous and that, within these societies, individuals differ in the degree to which they accept such models of mind (16, 17).

For personal orientations, we focus on “absorption”: an individual’s personal tendency to be engrossed in sensory or imagined events. People with a greater capacity for absorption tend to “lose themselves” in their sensory experiences and are capable of conjuring vivid imagined events. For example, they might get so caught up in music that they do not notice anything else, or they might feel that they experience the world the way they did as a child (18). In the psychological literature, absorption is commonly considered to be a personality trait, although it may be sensitive to experience or training (19). Among US adults, absorption has been associated with an orientation toward fantasy and artistic pursuits, intense mystical experiences in response to psychedelics or placebo brain stimulation, and strong feelings of presence and transcendence when confronted with natural beauty, virtual reality, or music (19, 20). Our work in an American charismatic Christian church found that congregants who reported more vivid experiences (e.g., that they experienced God in dialogue or heard God’s voice audibly) tended to score higher on measures of absorption (21).

We view porosity as one dimension along which cultural models of the relationship between mind and world vary across cultures. Different communities come to different understandings about the degree to which any boundary between the mind and world is permeable and about the ways in which this boundary might be crossed. Such cultural models set expectations for which events are likely or possible and provide explanatory frameworks for making sense of events—including anomalous or ambiguous events—as they occur. Meanwhile, absorption facilitates vivid sensory experiences in general—including experiences of objects, beings, or forces that are not present in ordinary ways (e.g., because they are not visible). Thus, porosity and absorption are complementary influences in two senses: Porosity is a cognitive factor, which captures ideas promoted by a broader social-cultural setting, such as a local community or a religious group (22), while absorption is an experiential factor, which captures an individual’s personal style of relating to the world.

In this paper, we present an interdisciplinary program of research that has yielded convergent evidence for the following theory: Porosity and absorption play distinct roles in explaining why certain people, in certain cultural and religious settings, are more likely to experience spiritual presence events.

Overview

These studies were part of a long-term collaboration grounded in cultural anthropology and experimental psychology, which involved qualitative and quantitative data collection with several thousand participants in five countries over the course of 3 y. Here, we describe the four core studies from this project: study 1, which examined relationships between porosity, absorption, and spiritual presence events via in-depth interviews with people of faith; targeted studies of porosity (study 2) and absorption (study 3); and study 4, a confirmatory test of our central claims.

Before describing these results in detail, we highlight two aspects of our general approach that provide an essential context for each individual study: the diversity of our methods and our samples.

Diverse Methods.

Spiritual presence events are of obvious importance in human history, but they are difficult to study because they rely on verbal report. We used a wide range of methods to capture these events more accurately than one method alone would allow. We took a similar approach to developing and refining measures of porosity—see Materials and Methods and SI Appendix—and relied on the standard Absorption Scale (18) to measure absorption.

We began by compiling a list of spiritual events thought to be experienced in many cultures in similar forms (23, 24)—the voice of a spirit spoken audibly or experienced in the mind; visions or dreams sent by a god or spirit; the felt presence of gods, ghosts, ancestors, or demons; bodily events like an intense rush of power—all vivid experiences of communication from nonordinary beings. Scholars have called such events “anomalous”: They stand out to those who experience them as unusual (25). We also asked some questions about anomalous events not framed as the evidence of spirits, such as a voice heard when alone or something seen that was not materially present.

In study 1, we employed a method we call “comparative phenomenology” (24) to ask about these events, probing for details about participants’ experiences in the manner of a clinical interview. These open-ended conversations were structured around our list of spiritual presence events, including specific follow-up questions designed to capture the phenomenological qualities of the participant’s experience (e.g., in response to a participant recounting an auditory experience: “Did you hear it with your ears? Did you turn your head to see where it was coming from?”). Interviewers—experienced ethnographers with cultural expertise specific to that site—conducted these conversations in a style they judged would be invitational to that participant and appropriate in that cultural setting. We see this method as eliciting the most reliable evidence of vivid, anomalous, sensory experiences of what participants took to be gods, spirits, and other supernatural forces. (See SI Appendix for more on this approach, including excerpts from these interviews.)

In study 2, we maintained a focus on eliciting open-ended responses from participants in face-to-face conversations, but adapted the study 1 interviews to design a briefer version with a stricter interview protocol administered by a local research assistant.

In studies 3 and 4, we further adapted the interviews from studies 1 and 2 to create pen-and-paper surveys in which participants answered questions about spiritual experiences using yes-or-no or Likert-type response scales. We used the resulting measure in combination with existing quantitative measures of spiritual and secular anomalous events. We see this method as offering the most psychometrically rigorous quantitative data for exploring the strength and nature of the relationships between absorption, porosity, and spiritual presence events.

Diverse Samples.

We examined spiritual presence events both across a range of faiths, cultures, and levels of formal education and within closely matched samples of people with a shared theology but different cultural models of the mind.

For our shared theology, we chose charismatic evangelical Christianity, the fastest growing religion in the world, which is known to have a relatively consistent theology and practice across different settings (26).

Each study took place in five countries—from west to east: the United States, Ghana, Thailand, China, and Vanuatu—chosen because each has a vibrant population of charismatic evangelical Christians as well as people from other faiths and because these sites offer a range of cultural models of the mind. In each country, an anthropologist with local expertise lived on site for 8 to 9 mo and led a team that continued the research upon the anthropologist’s departure.

In study 1, we sought out people with strong religious commitments living in both urban and rural field sites within each country. In each site, we worked with charismatic evangelical Christians and with practitioners of another faith salient in each local setting: Methodism in the United States; African traditional religion in Ghana; Buddhism in Thailand and urban China; spirit mediumship in rural China; Presbyterianism in urban Vanuatu; and ancestral “kastom” practices in rural Vanuatu.

In study 2, we collected an additional targeted sample of charismatic evangelical Christians in each country, but primarily sought to generalize our findings by recruiting participants in public places selected to attract a representative sample of the general population of the urban field sites (e.g., the department of motor vehicles, a bus station hub).

In studies 3 and 4, we worked with urban undergraduate students in each country because they were familiar with written questionnaires (e.g., examinations); this allowed us to refine and test precise hypotheses about the relationships between porosity, absorption, and spiritual presence events through psychometrically rigorous survey work and to examine whether these relationships are evident in samples with more experience with formal education.

Results

Variability in Spiritual Presence Events, Porosity, and Absorption.

These studies were designed to examine the hypothesized relationships between spiritual presence events, on the one hand, and porosity (studies 1, 2, and 4) and absorption (studies 1, 3, and 4), on the other hand. In so doing, they provided a striking demonstration of cultural and individual differences in these three constructs. We begin with a brief overview of these differences before analyzing the relationships between them as a possible explanation for why certain people, in certain settings, are more likely to experience spiritual presence events. For regression analyses of group differences, see SI Appendix, Tables S18, S19, S24, S31, and S36–S39.

Across all studies, participants in relatively more secular settings (e.g., the United States, urban China) reported fewer spiritual presence events, while participants in less secular settings (e.g., Ghana, Vanuatu) reported more—as did charismatic evangelical Christians in all countries (Fig. 1A).

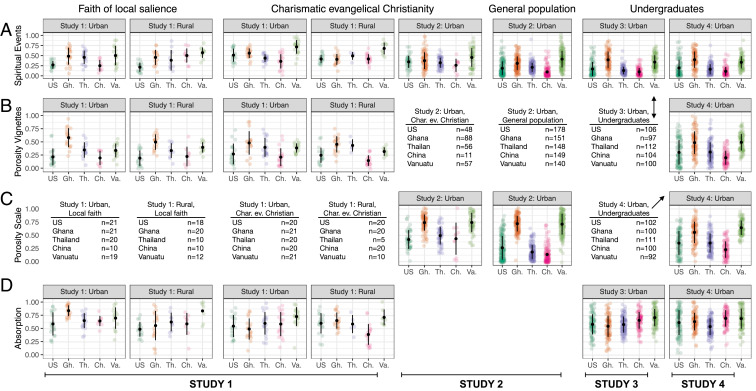

Fig. 1.

Scores on our primary variables of interest—(A) Spiritual Events, (B) Porosity Vignettes, (C) Porosity Scale, and (D) Absorption—for all samples in all studies. To aid in visual comparison across measures and studies, all scores have been rescaled to range from 0 to 1. Small points correspond to individual participants, larger points are means, and error bars are ±1 SD; see figure for sample sizes (but note that a few participants in each study were missing data for one or more measures). In study 1, “faiths of local salience” were as follows: United States: Methodism; Ghana: African traditional religion; Thailand: Buddhism; urban China: Buddhism; rural China: spirit mediumship; urban Vanuatu: Presbyterianism; rural Vanuatu: ancestral kastom practices.

These studies revealed a similar, consistent pattern for porosity, with participants in Ghana, Vanuatu, and in some cases, Thailand generally espousing more porous models of the mind–world boundary, and participants in the United States and particularly urban China espousing less porous models (Fig. 1 B and C).

Patterns in Absorption scores were subtler and less consistent across studies, which aligns with our understanding of absorption as a personal orientation that varies primarily across individuals, more than across social-cultural settings (Fig. 1D).

In interpreting these findings, it is important to remember that cultural models, while shared within a social world, are often embraced by individuals to varying degrees (27) and, conversely, that individual traits, while distributed across the human population, are also encouraged or discouraged by local social worlds (28). Indeed, for all of these variables, these group differences coexisted with substantial variability across individuals within each group. But, in line with our theory of porosity as a dimension of cultural models of the mind that varies primarily across social-cultural settings, group differences (across countries, urban vs. rural field sites, and religious groups) accounted for fully 27 to 67% of the variance in our two measures of porosity, compared to only 9 to 25% of the variance in our measure of absorption (and 30 to 39% of the variance in our primary measure of spiritual presence events, the Spiritual Events scale).

Study 1.

We first examined relationships among porosity, absorption, and spiritual presence events among people with strong religious commitments, including charismatic evangelical Christians and practitioners of the designated faiths of local salience. Participants were recruited through word-of-mouth at churches, temples, and shrines where field workers—all experienced ethnographers—regularly attended gatherings. Fieldworkers interviewed participants at length using our clinical style, “comparative phenomenology” approach. Each participant completed one interview about their spiritual experiences; a second interview about their understanding of the mind, including their endorsement of beliefs related to porosity; and a standard measure of absorption (18). The final sample for our primary analysis included n = 306 participants.

For extensive treatments of the qualitative results of these interviews, see ref. 24.

For the purposes of the current quantitative analysis, this study yielded three indices for each participant: 1) a Spiritual Events score, summarizing how many of the events included in the interview the participant reported having experienced; 2) a Porosity Vignettes score, summarizing how frequently and how strongly the participant endorsed the possibility of stories featuring a supernatural or otherwise extraordinary crossing of the mind–world boundary (e.g., one person hurting another with his angry feelings); and 3) an Absorption score, summarizing how many of the traits and preferences included in the Absorption scale the participant endorsed. See Materials and Methods and SI Appendix for details. Scores were standardized (collapsing across samples) before being entered into analyses.

These interviews elicited many accounts of vivid sensory experiences. Indeed, every participant reported at least one experience that they attributed to a spiritual source. For example, an American Christian reported, “This time, I was in my car, I was driving home, and I just felt the presence of God, overwhelming. Sure, I had on worship music low, but this was just like, He must have been resting right on top of me, in my car or whatever. It was so powerful, it was hard for me to drive the car… He was there so intensely, and it was so real.” A Thai Buddhist, when asked if she had ever seen a ghost with her eyes, responded yes, she had, as a first-year nursing student: “One night, I saw a man and a woman in front of the autopsy room. I saw them and wasn’t afraid, [I just thought,] oh, those are the people who donated their body.”

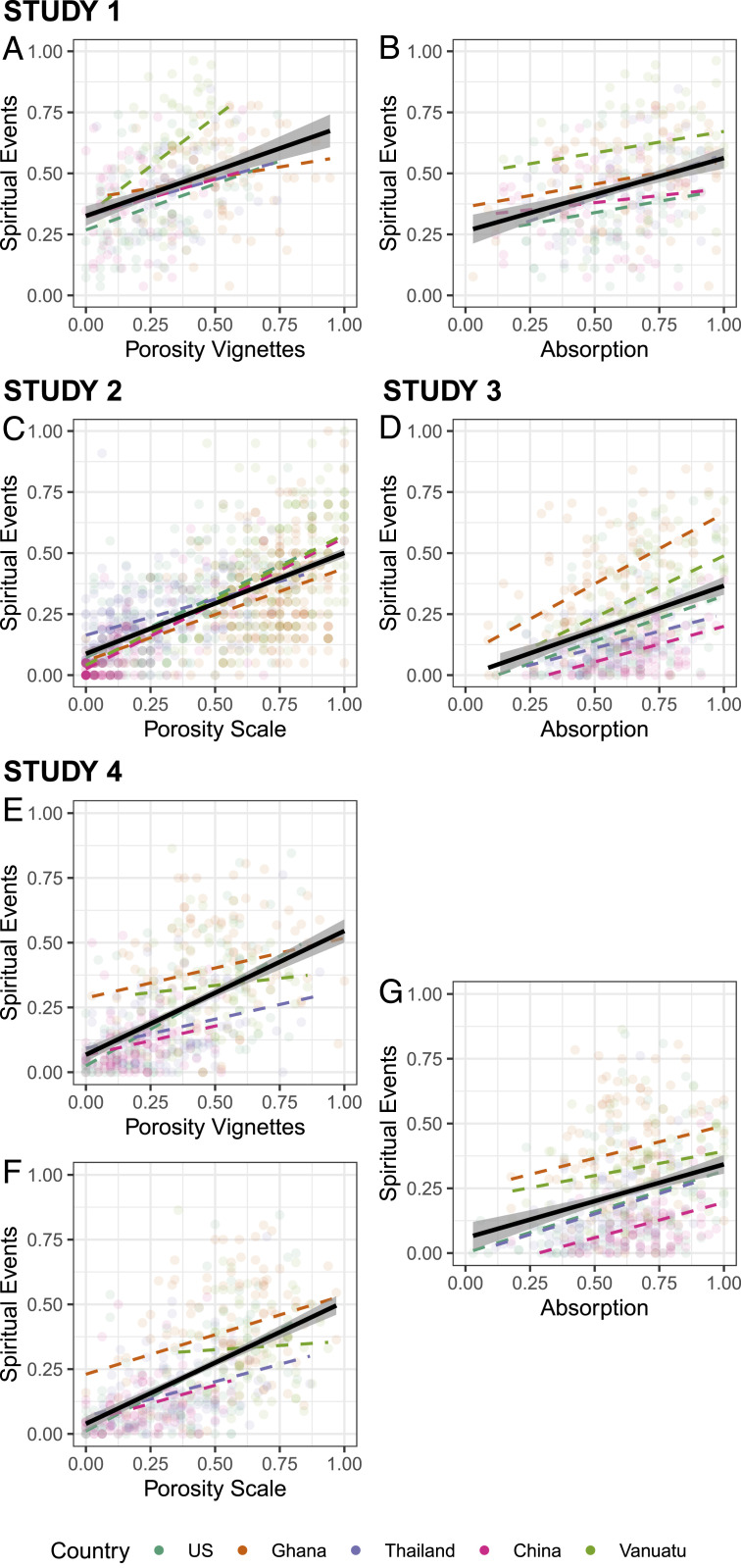

Porosity and absorption were positive predictors of participants’ reported experiences of spiritual presence events (Fig. 2 A and B). In a mixed-effects linear regression regressing Spiritual Events scores onto Porosity Vignettes scores, Absorption scores, and an interaction between them (and including random intercepts by religion, nested within urban vs. rural site, nested within country), both Porosity Vignettes scores (β = 0.24 [95% confidence interval: 0.14, 0.35], P < 0.001) and Absorption scores (β = 0.22 [0.13, 0.32], P < 0.001) were significant predictors of Spiritual Events scores. We observed no evidence for an interaction between porosity and absorption (β = −0.03 [−0.12, 0.06], P = 0.507) (SI Appendix, Table S20).

Fig. 2.

Relationships between Spiritual Events and measures of porosity (A, C, E, and F) and absorption (B, D, and G), by study and country, rescaled to range from 0 to 1. Colored circles correspond to individual participants, dashed colored lines correspond to the trend within each country, and solid black lines correspond to the overall trend collapsing across countries. See SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S2, for parallel visualizations of other measures of spiritual and secular anomalous events (studies 3 and 4).

For this and all other findings, our conclusions were robust to all analysis choices explored, including treating sample characteristics (e.g., country, religion) as fixed rather than random effects (SI Appendix).

These results suggest that porosity and absorption play distinct roles in facilitating spiritual presence events across diverse cultures and faiths.

Study 2.

We further examined the relationship between porosity and spiritual presence events among charismatic Christians (n = 260) and in large samples from the general population (n = 766) in each country. Participants were interviewed by trained research assistants who administered a brief version of the Spiritual Events interview from study 1 as well as a new set of questions (the “Porosity Scale”) probing participants’ beliefs about a variety of specific examples of porosity drawn from the fieldworkers’ experience administering study 1 and their ethnographic observations in their field sites (e.g., “Some people use special powers to put thoughts in other people’s minds and make them do something, like fall in love”; “Spirits can read our thoughts and act on them even if we don’t speak them out loud”). Porosity Scale questions were designed to capture beliefs about the mind–world boundary rather than personal phenomenal experiences.

These interviews yielded two indices for each participant: 1) a Spiritual Events score, summarizing how many of the events included in the interview the participant reported having experienced; and 2) a Porosity Scale score, summarizing how frequently and how strongly the participant endorsed the examples of porosity about which they were asked. See Materials and Methods and SI Appendix for details. Scores were standardized (collapsing across samples).

Echoing study 1, porosity was positively related to participants’ reported experiences of spiritual presence events (Fig. 2C). In a mixed-effects linear regression regressing Spiritual Events scores on Porosity Scale scores (including random intercepts and slopes by sample [charismatic Christians vs. general population], nested within country), Porosity Scale scores were a positive predictor of Spiritual Events scores (β = 0.65 [0.47, 0.83], P < 0.001) (SI Appendix, Table S26). A separate analysis confirmed that this relationship was significant in the subsample of charismatic evangelical Christians considered alone (β = 0.53 [0.30, 0.76], P < 0.001) (SI Appendix, Table S30), suggesting that cultural models of the mind–world boundary shape spiritual presence experiences even among people who hold similar theological commitments and engage in similar religious practices.

Study 3.

We further examined the relationship between absorption and spiritual presence events among undergraduates in urban field sites in each country. Across sites, a total of 519 undergraduates completed the Absorption scale (18) and two survey measures designed to gauge the frequency and vividness of their spiritual presence events: a pen-and-paper version of the Spiritual Events inventory, adapted from studies 1 and 2, and the widely used Daily Spiritual Experience scale (29). Scores were standardized (collapsing across samples).

Echoing study 1, two mixed-effects linear regressions (including random intercepts by country) suggested that Absorption scores were a positive predictor both of Spiritual Events scores (β = 0.40 [0.33, 0.46], P < 0.001) and of Daily Spiritual Experience scores (β = 0.24 [0.18, 0.30], P < 0.001) (SI Appendix, Table S33 and Fig. 2D).

Study 4.

After thorough explorations of the datasets from studies 1 to 3, we strove to conduct a formal, more precisely specified test of the hypotheses that porosity and absorption are distinct, positive predictors of spiritual presence events across cultures and faiths. This study also included an examination of whether the relationships between porosity, absorption, and spiritual presence events might be explained by individual or cross-cultural differences in an overall tendency to respond affirmatively (i.e., a response bias) as well as an exploration of whether porosity and absorption were predictive of anomalous experiences that might not be considered spiritual (e.g., hearing a voice not identified as from a god or spirit). See preregistration at https://osf.io/kmtc4.

Over 500 undergraduates, located in urban field sites in each country, completed the Absorption scale (18), the two indices of porosity, and the two indices of spiritual presence events used in studies 1 to 3 as well as two indices of “secular” anomalous events [focusing on hallucination-like experiences not marked as religious (30), and the paranormal (31)] and two control measures that we did not expect to be strong predictors of porosity, absorption, or spiritual presence events [the Need for Cognition scale (32), and the Sense of Control, Mastery subscale (33); final sample for primary analysis: n = 505]. Scores were standardized (collapsing across samples).

All our predictions were upheld.

Mixed-effects linear regressions taking into account variability across countries and measures of spiritual presence events confirmed that Porosity Vignettes scores were positive predictors of spiritual presence events (β = 0.29 [0.23, 0.36], P < 0.001), as were Porosity Scale scores (β = 0.41 [0.34, 0.47], P < 0.001) and Absorption scores (β = 0.22 [0.16, 0.28], P < 0.001) (SI Appendix, Tables S42 and S43 and Fig. 2 E–G). These relationships were significant when examined within each country separately (βs > 0.17, ps < 0.034; n ≥ 92 per country) with the only exceptions occurring for measures of porosity in Vanuatu (Porosity Vignettes: β = 0.12 [−0.05, 0.28], P = 0.18; Porosity Scale: β = 0.16 [−0.002, 0.32], P = 0.06) (SI Appendix, Tables S44–S46).

As in study 1, Porosity Vignettes scores and Absorption scores remained significant predictors of spiritual presence events after statistically controlling for each other in a single model and likewise for Porosity Scale scores and Absorption scores (SI Appendix, Tables S40–S43). In neither case did we observe evidence for an interaction (β = −0.03 [−008, 0.02], P = 0.27 and β = −0.01 [−0.06, 0.04], P = 0.63, respectively). This pattern of results is consistent with the possibility that porosity and absorption play not only distinct, but independent, roles in facilitating spiritual presence. However, we caution against taking this as strong evidence for the absence of any interactive relationship between porosity and absorption because our current samples—despite their size—were likely underpowered to detect anything but the most extreme cross-over interactions (34). In fact, it seems quite plausible to us that porosity might enhance the effect of absorption on spiritual presence events—or, conversely, that absorption might attenuate the effect of porosity. We consider this a fruitful area for further research.

The relationships between porosity, absorption, and spiritual presence events were very similar for “secular” anomalous events (SI Appendix, Tables S47–S53). We introduced this research program as an exploration of anomalous experiences deemed spiritual—but this finding suggests that porosity and absorption may facilitate a wide variety of unusual sensory experiences, even when they are not closely aligned with the particular experiences emphasized by an individual’s faith.

Notably, compared to our two control measures (Need for Cognition and Sense of Control), porosity and absorption were significantly stronger predictors of spiritual presence events [both when indexed by the Spiritual Events scale—β = 0.06 [0.04, 0.07], P < 0.001; and when indexed by the Daily Spiritual Experience scale—β = 0.03 [0.02, 0.04], P < 0.001 (SI Appendix, Table S55)]; this remained true when reverse-coded items were omitted from all scales (SI Appendix, Table S59). This is further evidence that the power of porosity and absorption to predict spiritual presence events goes beyond overall response biases (e.g., a “yes bias”) or sensitivity to the demand characteristics of these surveys (i.e., individual or cultural differences in tendencies to assess and agree with the central construct being assessed by a survey measure).

Finally, study 4 provided an opportunity to evaluate whether our measures of spiritual presence events and porosity tapped into distinct constructs, despite being highly correlated. The Spiritual Events and Daily Spiritual Experience measures asked directly about personal experiences of spiritual presence, whereas the Porosity Vignettes and Porosity Scale were designed to capture beliefs about the mind–world boundary. Nonetheless, the observed relationships between spiritual presence events and porosity could have arisen because participants did not mark the intended distinction between experiences and beliefs. To explore this possibility, we conducted a series of exploratory factor analyses of items from the various measures included in study 4. If our measures of spiritual presence events and porosity were in fact measuring the same latent construct, we might expect that most items from these scales would load onto a single factor or that factor analysis would surface sets of items with similar content (e.g., beliefs about and experiences of dreams). This was not the case. Instead, these analyses consistently revealed a clear distinction between factors capturing spiritual experiences (i.e., items from the Spiritual Events and Daily Spiritual Experience measures) vs. factors capturing porosity beliefs (items from the Porosity Vignettes and the Porosity Scale) (SI Appendix, Table S58). This finding was robust to our choice of retention protocol and to our choice of which measures to include in these analyses. We see this as a clear-cut demonstration that, from the perspective of individual participants’ responses to individual items, our measures of porosity vs. spiritual presence events successfully tapped into distinct constructs.

Discussion

This interdisciplinary program of empirical research provides evidence for a theory of why some people are more likely than others to sense the presence of gods and spirits. Across four large-scale studies—employing complementary methods and including a diverse range of participants located in five countries—a clear picture emerged: Porosity and absorption were strong predictors of spiritual presence events, regardless of people’s participation in a particular religion or their living in a particular location and regardless of how we assessed these relationships. These two factors played distinct roles in determining which people, in which cultural settings, were most likely to report experiencing spiritual presence.

These results are robust. They emerged in in-depth, clinical-style interviews with people of faith conducted by ethnographers with local expertise (study 1), in briefer interviews with the general population (study 2), and in rigorous survey work with undergraduates (studies 3 and 4), including a preregistered confirmatory test of our core claims (study 4). The link between absorption and spiritual presence events was replicated three times (studies 1, 3, and 4), adding to the handful of studies suggesting such a link (19, 21) and expanding the use of the Absorption scale far beyond its origins in Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic (“WEIRD”) (35) and English-speaking settings. The link between porosity and spiritual presence events was also replicated three times (studies 1, 2, and 4) and was evident within subsamples of participants who held similar theological commitments and engaged in similar religious practices (charismatic evangelical Christians; studies 1 and 2).

The different methods employed in these studies combine to lend us confidence in our core findings: Our psychometrically rigorous survey work indicates that the relationships between absorption, porosity, and spiritual presence events go beyond statistical artifacts and demand characteristics or response biases, while our more open-ended, clinical-style interviews, with their focus on assessing phenomenology, have convinced us that for many people around the world the “spiritual presence events” at the center of this work are indeed vivid sensory experiences taken as evidence of gods and spirits (and not merely poetic turns of phrase).

Discussion of Porosity and Absorption.

Cultural models or folk theories of a porous boundary between “mind” and “world” provide an explanatory framework in which ambiguous sensory events may be attributed to sources other than one’s own mind, including spiritual beings and supernatural forces, and in which thoughts and other mental events are treated as more substantial and therefore more potent. Some distinction between an “inner” mind and an “outer” world likely exists in most cultural models of the mind. Most of these models also include everyday ways in which such a boundary might be crossed (e.g., thoughts being exchanged across minds through conversation). When people in a particular context speak of divine inspiration, divination, telepathy, witchcraft, or miraculous healing, they accept that, for some people, under some circumstances, knowledge enters the mind from the outside in unusual ways and emotions or intentions leave the mind to affect the world in unusual ways. These representations likely draw on common human experiences—insight, intuition, wishing, awe—but the ethnographic record makes clear that the ways in which the inner–outer, mind–world boundary is drawn, and the more extraordinary means by which it might be crossed, vary across social worlds (36). Different social-cultural settings invite people to attend or disattend to this distinction; to take some experiences more seriously than others; to identify different sets of conditions under which these events can occur; and to invoke different causal mechanisms to explain these events. We speculate that cultural differences in models of the mind reflect, at least in part, the incentives provided by different social conditions. For example, anthropologists have observed that ideas about witchcraft are more salient in traditional agricultural societies, in which people who are in conflict with each other cannot leave, than in hunter-gatherer societies; they are also more common in some urban societies with a paucity of social trust (37, 38).

We view absorption as an immersive style of attention, a personal orientation toward one’s own mind, that varies across individuals, independent of cultural models of the mind. In our theory, absorption facilitates a sense of spiritual presence because many apparently supernatural events emerge when people attend differently to the world: they use their imagination to understand something beyond the here-and-now, to watch for signs of the presence of a being that cannot be seen. As people become absorbed, their practical concerns recede and their immersion increases. When turned toward sensations, emotions, thoughts, mental images, and the like, such an orientation helps those sensations to be experienced as more vivid, more autonomous, and ultimately more external or “not me.” The process here is likely similar to that at work in trance, dissociation, and hypnosis, all of which are associated with more vivid mental imagery (39) and unusual sensory experiences (40).

In other words, porosity concerns models or theories about how the mind works, and absorption is an experiential orientation that influences the way that thoughts and other mental events feel. The impact of these two factors on spiritual experience arises because of the way in which they invite people to interpret and engage with their own inner lives as more vivid, material, and potent. Neither porosity nor absorption is the same as religion. Instead, porosity and absorption may be part of the scaffolding on which religions build (41)—e.g., by offering causal models of how God’s voice can be heard in the mind and of how demons feed on jealous feelings, or by inviting people to immerse themselves in their inner lives through prayer or meditation.

Both absorption and porosity in effect blur the boundary between inner mental events and an outer world. Porosity specifies how to understand and reason about this boundary, providing (among other things) an explanation of how mental events might originate from outside sources; absorption allows one to use the imagination to go beyond the here-and-now in a way that does not feel merely imaginary. Each makes more likely the anomalous sensory events—the voices heard by Augustine and Martin Luther King, the visions and other experiences that have sparked and sustained other religious movements—that have been so consequential throughout history. The current studies document and begin to explain why sensory experiences of gods and spirits are reported more frequently in some cultural-religious settings than in others and more frequently by some individuals within a given setting than by others—an important aspect of the human experience that is poorly understood by social scientists. In so doing, our results provide a striking demonstration of the power of culture, in combination with individual differences, to shape something as basic as what feels real to the senses.

Materials and Methods

The studies reported in this paper were approved by the Stanford Administrative Panel on Human Subjects in Nonmedical Research. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

All studies include roughly equal samples from the United States, Ghana, Thailand, China, and Vanuatu; see SI Appendix for detailed materials and methods. Data files and analysis code are available at https://github.com/kgweisman/sense_spirit.

Study 1.

Over 300 adults with strong religious commitments completed two in-depth interviews: one about their experience of spiritual presence events and the other about their understanding of the mind. See SI Appendix, Table S14, for demographics.

These interviews were conducted by experienced ethnographers using our “comparative phenomenology” approach (Overview). Our index of spiritual presence events (“Spiritual Events” scale, version 2, SI Appendix, Table S2) was a measure derived from the first interview. For each of the spiritual presence events included in this interview, the interviewer made a holistic judgment of whether the participant indicating having personally experienced such an event (“no” = 0, “maybe” = 0.5, “yes” = 1); judgments were averaged together to create a score ranging from 0 to 1, which was standardized (collapsing across samples) prior to all analyses reported here. See SI Appendix for a recoding of these interviews by a separate group of coders; in these independent judgments, the reported relationships remain robust.

Our index of porosity (“Porosity Vignettes,” SI Appendix, Table S6) was a measure derived from the second interview. This interview included brief stories designed to pick up on how the boundary between mind and world might be porous. For example: “Suppose that in a distant community, very much like this one, there’s a man named Michael; one day Michael realizes that his neighbor, Charles, is really, really angry at him. Charles is angry at Michael and has been angry for a long time. If Charles wanted to hurt Michael with his angry feelings, could he do that? Could Charles hurt Michael just by thinking angry thoughts about him? Suppose Michael got sick after Charles got angry with him. Do you think Charles’s anger could be the cause? Could Charles’s anger make it so that a spirit could hurt Michael?” For each question, interviewers probed deeply and then helped participants indicate their belief about whether and how frequently this kind of event could occur (“never” = 0, “rarely” = 1, “often” = 2, “very often” = 3); responses were averaged together to create a score ranging from 0 to 3, which was standardized (collapsing across samples) prior to all analyses reported here.

Our measure of absorption—the standard Absorption scale (18) (SI Appendix, Table S9)—was administered at the time of the second interview. This scale consisted of questions about traits and preferences related to an immersive personal orientation to inner life and the world. Response options included “false” (scored as 0) and “true” (1); responses were averaged together to create a score ranging from 0 to 1, which was standardized (collapsing across samples) prior to all analyses here.

Study 2.

In study 2, n = 766 adults from the general population, as well as a smaller sample of n = 236 charismatic evangelical Christians, were administered a brief version of the spiritual experience interview from study 1, yielding a “Spiritual Events” score (SI Appendix, Table S3). Participants also answered a new set of questions—the “Porosity Scale” (SI Appendix, Table S8)—in which they assessed the plausibility of specific examples of porosity drawn from the fieldworkers’ experience in their field sites—e.g., “Spirits can read our thoughts and act on them even if we don’t speak them out loud.” Responses were averaged to create scores ranging from 0 (“It does not happen”) to 2 (“It definitely happens”), which were standardized (collapsing across samples) prior to all analyses reported here. See SI Appendix, Table S15, for demographics.

Study 3.

In study 3, n = 519 undergraduates completed a survey consisting of the Absorption scale and two measures of spiritual presence events [version 3 of the “Spiritual Events” scale, as used in study 2, and a modified version of the widely used Daily Spiritual Experience scale (29) (SI Appendix, Table S5)]. See SI Appendix, Table S16, for demographics.

Study 4.

In study 4, n = 505 undergraduates completed a survey consisting of the two measures of porosity used in studies 1 and 2, the Absorption scale as used in studies 1 and 3, and the two measures of spiritual presence events used in studies 1, 2, and 3, as well as two measures of “secular” anomalous events [focused on hallucination-like experiences (30) (SI Appendix, Table S10) and the paranormal (31) (SI Appendix, Table S11)] and two control measures which we predicted would not be strongly correlated with our measures of interest [the Need for Cognition scale (32) (SI Appendix, Table S12) and the “Mastery” subscale of the Sense of Control scale (33) (SI Appendix, Table S13)]. Our analysis of study 4 closely followed our preregistration of this study (https://osf.io/kmtc4). See SI Appendix, Table S17, for demographics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the research teams and participants in each field site (see extended Acknowledgments in SI Appendix) and Hazel Markus and Ann Taves. This material is based on work supported by John Templeton Foundation Grant 55427. K.W. was also supported by the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program (DGE-114747) and a William R. & Sara Hart Kimball Stanford Graduate Fellowship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2016649118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.

References

- 1.Hood R. W. Jr, Hill P. C., Spilka B., Psychology of Religion: An Empirical Approach (Guilford, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Augustine, The Confessions of Saint Augustine (Penguin, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 3.King M. L. Jr, Stride toward Freedom (Beacon, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taves A., Religious Experience Reconsidered (Princeton, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luhrmann T. M., When God Talks Back (Knopf, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaden D. B., et al. , The noetic quality: A multimethod exploratory study. Psychol. Conscious. 4, 54–62 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumeister D., Sedgwick O., Howes O., Peters E., Auditory verbal hallucinations and continuum models of psychosis: A systematic review of the healthy voice-hearer literature. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 51, 125–141 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stang C., A Walk to the River in Amazonia: Ordinary Reality for Mehinaku Indians (Berghahn Books, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rockie S., Death and the Invisible Powers: The World of Kongo Belief (Indiana University, 1993). [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Andrade R., The Development of Cognitive Anthropology (Cambridge University Press, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gopnik A., Wellman H. M., “The theory theory” in Mapping the Mind: Domain Specificity in Cognition and Culture, Hirschfield L., Gelman S. A., Eds. (Cambridge University Press, 1994), pp. 257–293. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allport G., The Person in Psychology (Beacon Press, 1968). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powers A. R., Mathys C., Corlett P. R., Pavlovian conditioning-induced hallucinations result from overweighting of perceptual priors. Science 357, 596–600 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson M., Raye C., Reality monitoring. Psychol. Rev. 88, 67–85 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor C., A Secular Age (Harvard University Press, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyer P., Tradition as Truth and Communication (Cambridge University Press, 1990). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shore B., Culture in Mind: Cognition, Culture, and the Problem of Meaning, Oxford University Press, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tellegen A., Atkinson G., Openness to absorbing and self-altering experiences (“absorption”), a trait related to hypnotic susceptibility. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 83, 268–277 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lifshitz M., van Elk M., Luhrmann T. M., Absorption and spiritual experience: A review of evidence and potential mechanisms. Conscious. Cogn. 73, 102760 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roche S. M., McConkey K. M., Absorption: Nature, assessment, and correlates. J. Soc. Psychol. 59, 91–101 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luhrmann T. M., Nusbaum H., Thisted R., The absorption hypothesis: Learning to hear God in evangelical Christianity. Am. Anthropol. 112, 66–78 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markus H. R., Kitayama S., Cultures and selves: A cycle of mutual constitution. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 5, 420–430 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hufford D., “Beings without bodies: An experience-centered theory of the belief in spirits” in Folklore and the Supernatural, Walker B., Ed. (University Press of Colorado and Utah State University Press, Louisville, 1995), pp. 11–45. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luhrmann T. M., Ed., Mind and Spirit: A Comparative Theory (Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 2020), vol. 26, pp. 1–166. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cardeña E., Lynn S. J., Krippner S., Varieties of Anomalous Experience (APA, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller D., Sargeant K., Flory R., Eds., Spirit and Power: The Growth and Global Impact of Pentecostalism (Oxford University Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atran S., Medin D., The Native Mind and the Cultural Construction of Nature (Beacon Press, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rozin P., Five potential principles for understanding cultural differences in relation to individual differences. J. Res. Pers. 37, 273–283 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Underwood L. G., Teresi J. A., The daily spiritual experience scale: Development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Ann. Behav. Med. 24, 22–33 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrison A. P., Wells A., Nothard S., Cognitive factors in predisposition to auditory and visual hallucinations. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 39, 67–78 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thalbourne M. A., Delin P. S., A new instrument for measuring the sheep-goat variable: Its psychometric properties and factor structure. J. Soc. Psychical Res. 59, 172–186 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cacioppo J. T., Petty R. E., The need for cognition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 42, 116–131 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lachman M. E., Weaver S. L., The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 763–773 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blake K. R., Gangestad S., On attenuated interactions, measurement error, and statistical power: Guidelines for social and personality psychologists. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 46, 1702–1711 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henrich J., Heine S. J., Norenzayan A., The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 33, 61–83, discussion 83–135 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lillard A., Ethnopsychologies: Cultural variations in theories of mind. Psychol. Bull. 123, 3–32 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Douglas M., Ed., Witchcraft: Confessions and Accusations (Routledge, 1970). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gescheiere P., Witchcraft, Intimacy and Trust: Africa in Comparison (University of Chicago Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crawford H. J., Hypnotizability, daydreaming styles, imagery vividness, and absorption: A multidimensional study. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 42, 915–926 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glicksohn J., Barrett T. R., Absorption and hallucinatory experience. Cognit. Psychol. 17, 833–849 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Willard A. K., Norenzayan A., Cognitive biases explain religious belief, paranormal belief, and belief in life’s purpose. Cognition 129, 379–391 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.